#plotinus

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

What is meant by the purification of the soul is simply to allow it to be alone. It is pure when it keeps no company, entertains no alien thoughts; when it no longer sees images, much less elaborates them into veritable affections.

The Enneads

Plotinus

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

The stars are like letters that inscribe themselves at every moment in the sky. Everything in the world is full of signs. All events are coordinated. All things depend on each other. Everything breathes together.

― Plotinus (c. 204/5 – 270 CE), précis of Enneads, II.3.7

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

Genius is nothing other than the ability to retrieve childhood at will.

Charles Baudelaire

Is this all there is to art? A kind of solipsism? An inability to get past the egoism of infancy?

In Fellini’s masterpiece 8+1/2 the answer seems to lie with unraveling the mysterious phrase ‘Asa Miso Nasa’. Up front I will admit the film is not easy to follow as it doesn't really have a great plot and it does feel like episodic that gives it a disjointed look. But that doesn't mean there are no grand narratives underpinning it because there is.

The film, released in 1963, is about a movie director named Guido. His latest project has stalled before filming has even begun. Played by the incomparable Marcello Mastroianni, Guido is suffering from anxiety and creative block. It’s no wonder. He has sown chaos in his love life, and his creative indecision is producing near-mutinous levels of angst among actors, agents and crew. But all of this is mere surface tumult. Guido is haunted by something deeper. Something to do with . . . what? His parents, his childhood, the Catholic church? Feelings of shame and bliss? Death? All he has to answer his question is the phrase 'Asa Miso Nasa' to unlock answers but something he doesn't quite get.

In many ways ‘Asa Miso Nasa’ is a red herring, a sort of wild goose chase to nowhere. Like "Rosebud" in Orson Welles' Citizen Kane, or the madeleine in Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time, "Asa Nisi Masa" is a Hitchcockian ‘MacGuffin’ - a convenient object upon which the plot turns. In Fellini’s film it’s used as a gateway to crucial memories of the central character - even though it is itself peripheral to the central story.

Fellini’s answer is, I think, with his apprehension that the urge to make art is connected to a time in our lives when we were lifted and carried about, lowered into baths, tucked into bed; when we first used our lips to suck and to kiss; when we flapped our arms and kicked our legs; or when we danced without unrestrained joy. In other words, when we felt ourselves to be unique in our childhood.

Why should that be so? James Fenton, the great poet and critic, provided a plausible answer, even if he was writing about something else.

“Because,” wrote Fenton - and here comes the part that Guido, the anxious, grown-up filmmaker, must reckon with - “there follows the primal erasure, when we forget all those early experiences, and it is rather as if there is some mercy in this, since if we could remember the intensity of such pleasure it might spoil us for anything else. We forget what happened exactly, but we know that there was something, something to do with music and praise and everyone talking, something to do with flying through the air, something to do with dance.”

Something Fellini-esque, you might say.

Art is more than a pathetic desire to revert to childhood bliss. It’s true that the self-centredness of great artists - and by no means just male artists - is bound up with their desire to find again the treasure in the corner of the childhood bedroom, and the only sound is the children’s chant: “Asa Nisi Masa.” But what do all artists want if not to be understood.

But here we run into a problem. For all the attention artists seek, there is a kind of shame for them in being “understood.” Being “explained” is never more than an inch from being “explained away,” rendered redundant, losing the vital quality that makes one unique. Their egos can't handle that. So we can never judge beauty in art if we limit ourselves to just the life and meaning of an artist. If anyone ever says they don't like this art because of this artist was not nice or was abusive or held questionable beliefs then they are either illiterate fools or as shallow as the unfunny Hannah Gadsby is about Picasso.

There is much, much more to art, which, at its best, is always about transcending solipsism and reaching for beauty.

For Roger Scruton, the great philosopher of aesthetics, “Beauty is an ultimate value - something that we pursue for its own sake, and for the pursuit of which no further reason need be given. Beauty should therefore be compared to truth and goodness, one member of a trio of ultimate values which justify our rational inclinations,” Scruton developed a largely metaphysical aspect to understanding standards of art and beauty. For Scruton, the purpose of art is to save the sacred - the beautiful.

For Scruton, beauty is wrapped up in his view of the sacred. The sacred begins with the fundamental nature of man as an end, not merely a means - here childhood memories are a means not an end. Scruton then, is able to apply this concept of ends to beauty. The ability to place meaning on things is what gives man his sacredness and makes him an end unto himself. The sacred gives us a glimpse into eternity, and provides man with the cure to his temporal misery. In a manner almost Platonic, Scruton describes the sacred as pulling man out of the world of things and into the transcendental realm. It is an attempt not so much to find a glimpse of our childhood so much as to find Eden again, even if only in a finite temporal way, and to “prefigure our eternal home.”

Thus, it is this sacred nature of ends, not means, that Scruton puts forth in his understanding of beauty. In this Scruton echoes those philosophers of that past. Some like the Greek philosopher, Plotinus, beauty is seen as an ultimate value, pursued for its own sake, and the way in which the “divine unity makes itself known to the soul.”

Beauty is the glue that holds cultures together. It transcends individual places and ages. Light shining through stained glass in the Notre-Dame Cathedral, the face of Mary in Michelangelo’s La Pietà, a Bach orchestral suite, or a Frederico Fellini film (and none more so than the playful but sublime 8+1/2). Our experiences of these things connect us to the experiences of so many others over the decades and centuries since their creation. The beauty links us with a sense of profoundness and awe.

#baudelaire#charles baudelaire#quote#fellini#film#cinema#movie#art#aesthetics#beauty#childhood#memory#platonic#roger scruton#scruton#plotinus#eden#sacred#james fenton#frederico fellini#italian cinema#hannah gadsby is not funny#arts#culture

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

perseid meteor shower :: [Ignacio Municio :: Refugios en las Alturas]

* * * * "The stars are like letters which inscribe themselves at every moment in the sky. Everything in the world is full of signs. All events are coordinated. All things depend on each other; as has been said, "Everything breathes together.""

~ Plotinus

#meteor shower#quotes#the stars#Plotinus#The Heavens#my favorites#cycles#nature#stars#breath#movement

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Plotinus’s The Enneads

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Tres cosas conducen a Dios: la música, el amor y la filosofía”

Plotino

Fue un filósofo helenístico autor de las Enéadas y fundador del neoplatonismo junto con otros filósofos como Numenio de Apamea, Porfirio, Jámblico y Proclo.

Nació alrededor del año 205 d.C. en Licópolis Egipto. Su vida y filosofía fueron muy importantes en el pensamiento occidental y a pesar de haber vivido en una época llena de agitación política, Plotino centró su atención en el mundo de las ideas y en la filosofía.

Durante su juventud estudió con varios maestros filosóficos, desarrollando un carácter melancólico y reflexivo. A la edad de 28 años encontró a Ammonio, un maestro que le brindó paz espiritual y que durante 11 años lo marcó en un punto de inflexión filosófica y en su propia forma de vida.

No obstante, en un giro inesperado, Plotino se unió al ejército bajo las ordenes del general Gordiano quien planeaba una expedición a Persia. El fracaso de esta campaña hizo que a duras penas lograra salvar su vida, quien derivado de lo anterior, decidió abrazar completamente la filosofía y a desarrollar su propio sistema de pensamiento.

Durante su vida en Roma, Plotino llevó una vida inusual, se abstuvo de comer carne y realizó frecuentes ayunos, siguiendo algunos de los principios pitagóricos antiguos. Sin embargo a pesar de ello Plotino logró ganar gran prestigio como maestro público en Roma en donde sus enseñanzas atrajeron a estudiantes de diversas clases sociales.

El emperador Galeano y su esposa le tenían alta estima y estaban dispuestos a otorgar a Plotino una ciudad en la Campania para establecer una república platónica, sin embargo, los ministros imperiales se opusieron a esa idea argumentando ser inapropiado en el contexto del imperio Romano.

La propuesta central de Plotino consistía en en que existe una realidad que funda cualquier otra existencia en donde el principio básico es solamente lo “Uno”, la unidad, lo más grande, como un Dios único e infinito. De donde se funda la existencia de todas las cosas, en donde el uno está mas allá del ser.

El Uno representa la realidad inmejorable y suprema de la cual el nous y el alma provienen.

El Nous no tiene una traducción adecuada pero algunos autores lo traducen como el espíritu, mientras que otros prefieren hablar de inteligencia, mas esta vez no con un sentido místico sino intelectual. En la explicación del Nous, Plotino parte de la semejanza entre el Sol y la Luz. El Uno sería el sol y la luz como el Nous. La función del Nous como luz es la de que el Uno pueda verse a si mismo, pero como es imagen del Uno, es la puerta por donde nosotros podemos ver al Uno. Plotino manifiesta que el nous es el resultante del “contacto” con el Uno.

El tercer elemento es el alma, el cual en un extremo está ligada el Nous y tira de él, y en el otro extremo esta asociado al mundo de los sentidos del cual es creadora, es decir, el gobernante de todos los objetos y pensamientos en el mundo tangible, es decir, el nuestro, el cual se encarga de generar materia debido a la insuficiencia de producir ideas y ejecutarlas.

El enfoque filosófico de Plotino se caracteriza por su estilo razonador y dialéctico en donde cada tema se reduce a una idea fundamental. Siendo sus escritos, referentes de estudio y admiración en el mundo académico.

Plotino murió en Roma, a la edad de 66 años en el año 270 d.C. Sus obras, conocidas como la Enéadas, son una síntesis de la filosofía, y se inspira en gran medida en el pensamiento de Platón, pero también incorpora elementos del aristotelismo y el estoicismo.

Fuente: Wikipedia.

#egipto#plotinus#plotino#frases de reflexion#citas de la vida#filosofos#filosofo#filosofía#frases de filosofos#citas de filosofía#citas de filosofos#eneadas#citas de reflexion#notasfilosoficas

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The World Soul of Plotinus. Paul Laffoley. 1972-75.

#neoplatonism#platonism#stoicism#philosophy#classical philosophy#plotinus#plato#porphyry#proclus#iamblichus#hermeticism#hermetic#platonic

13 notes

·

View notes

Quote

This would be similar to two people who lived in the same house and one of them despises the structure and the person who built it but still stays there any way. The other does not hate it but claims that the builder made it most skillfully, even though he longs for the time when he can leave because he will no longer need a house. The first person thinks he is wiser and more prepared to leave because he knows how to claim that the walls are made of lifeless stone and wood and lack much in comparison to the true home. He does not understand, however, that he is only special because he cannot endure what he must—unless he admits that he is upset even though he secretly delights in the beauty of the stone. As long as we have a body, we must remain in the homes which have been made for us by that good sister of a soul who has the power to build without effort. Τοῦτο δὲ ὅμοιον ἂν εἴη, ὥσπερ ἂν εἰ δύο οἶκον καλὸν τὸν αὐτὸν οἰκούντων, τοῦ μὲν ψέγοντος τὴν κατασκευὴν καὶ τὸν ποιήσαντα καὶ μένοντος οὐχ ἧττον ἐν αὐτῷ, τοῦ δὲ μὴ ψέγοντος, ἀλλὰ τὸν ποιήσαντα τεχνικώτατα πεποιηκέναι λέγοντος, τὸν δὲ χρόνον ἀναμένοντος ἕως ἂν ἥκῃ, ἐν ᾧ ἀπαλλάξεται, οὗ μηκέτι οἴκου δεήσοιτο, ὁ δὲ σοφώτερος οἴοιτο εἶναι καὶ ἑτοιμότερος ἐξελθεῖν, ὅτι οἶδε λέγειν ἐκ λίθων ἀψύχων τοὺς τοίχους καὶ ξύλων συνεστάναι καὶ πολλοῦ δεῖν τ��ς ἀληθινῆς οἰκήσεως, ἀγνοῶν ὅτι τῷ μὴ φέρειν τὰ ἀναγκαῖα διαφέρει, εἴπερ καὶ μὴ ποιεῖται δυσχεραίνειν ἀγαπῶν ἡσυχῇ τὸ κάλλος τῶν λίθων. Δεῖ δὲ μένειν μὲν ἐν οἴκοις σῶμα ἔχοντας κατασκευασθεῖσιν ὑπὸ ψυχῆς ἀδελφῆς ἀγαθῆς πολλὴν δύναμιν εἰς τὸ δημιουργεῖν ἀπόνως ἐχούσης.

Plotinus, Ennead 2.9

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

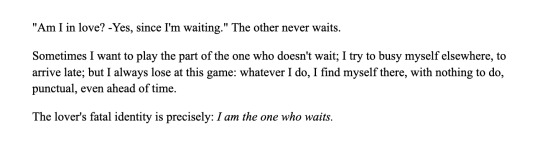

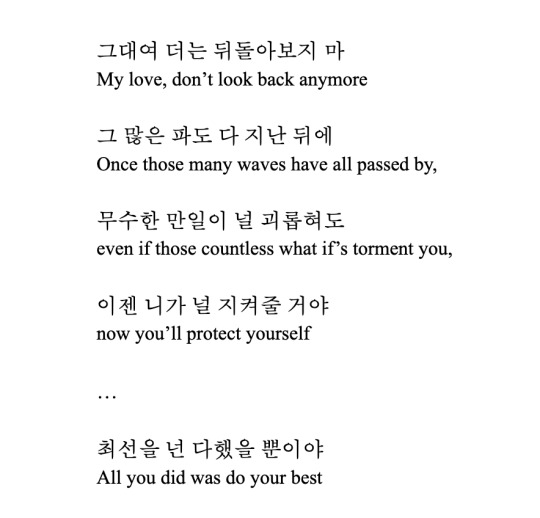

the fact is, phaedrus, i myself am a lover of these divisions and collections

sources: orpheus, eurydice, hermes; on beauty; SDL; a lover's discourse; hadestown (NYTW); the descent; no.2

#quotes#web weaving#literature#musicals#musical theatre#rilke#orpheus and eurydice#orpheus#eurydice#beauty#plotinus#agust d#roland barthes#hadestown#hadestown nytw#broadway#music#song lyrics#poetry#bts#kim namjoon#min yoongi#aesthetic#aesthetic quotes#greek mythology#greek myths#stephen mitchell#book#book quotes#literature quotes

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

our endeavor is not to be out of sin, but to be a god

Plotinus, in the Enneads, surprisingly almost anticipating what people often take be to the ethos of the Left Hand Path, at least where it is concerned with apotheosis.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Divine Will is Creativity

— the divine word or verb becomes flesh

The truly wise of any culture, time or place do not disagree on the true Nature of Reality.

Many have observed the great similarities between Greek & Indian philosophies & attribute it to the routes of travel that existed between cultures at times in the past via trade routes, settler colonies etc. leading to a confluence of knowledge.

This may well be true, but outward connectedness is because behind the outer connections, between things lies a higher order unity & wholeness.

The primordial tradition informs all culture's wise knowledge- true knowledge belongs to no one & any particular culture is but another iteration & expression of the higher in a particular time & place.

The ephemeral space in-between things, places & times is what mediates interconnection, contact & touch. Between ourselves & another there seems to be a gap through which we must make contact & in this space is where objects arise, our tools of creation, like the pen, the instrument with which we can establish contact with another.

Even this body-mind system, with its senses is but an instrument, but this instrument, because it is endowed with intellect & imagination can perceive outwardly, & can also look within.

When intellect looks back on itself it can 'see' possibilities & potentialities within 'space' - for what may come into actuality in the next moment of Now- assessing possibilities happens spontaneously, but can become more conscious & deliberate if we notice (& participation non-spontaneously), here the faculty of Will/knowing comes in & its relevance in creativity.

The creation is the outgoing creative activity of Will, bringing possibilities into actuality, innately productive.

Creativity is fundamental 'being' as an activity or verb, out of the activity of spontaneous being as a verb, the divine or God as a noun emerges—

the word is born as flesh.

Philosophers may say 'process' — precedes & underlies forms— all forms are momentary appearances/perceptions arising from the confluence of movement/activity of the one.

We can't throw out perceptions, because they are the one, momentarily appearing as the other, mediated by space pervaded by knowing.

#Plotinus #will

#alchemy#witch#oracle#esoteric#presence#love#patriarchy#magic#consciousness#Plotinus#divine Will#free will#spares#contact#philosophy

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Devotion to the One: Theurgy, Neoplatonism & Ritual

Theurgy is derived from the Greek words “theos” meaning “God” and “ergos” meaning “working”, resulting in “God-working.” The word was first used in the Neoplatonist text the “Chaldean Oracles” and refers to the process of working through the several divine emanations in order to achieve henosis, or unity with the One. I personally find theurgy to be an extremely fascinating though equally as complex topic, and I aim to explain it’s origins, philosophy, and practical application in this blog post.

Origins

Theurgy itself is rooted in early Neoplatonism and each emanation is described by its founder, Plotinus. The One, also referred to as God or in some cases the Godhead, is the origin point of all things. A popular neoplatonist symbol is that of a dot encircled by a larger circle- the One is that dot and the larger circle is all other multitudes of emanation. The one is inherently good and beautiful and this goodness may descend through each level. The Nous, also referred to as the Intellect, is the conscience of the cosmos, and the Soul may refer to that of the individual or the universe. The Soul is the unified life-form of all living things. Theurgy was an essential element of the Hellenic faith, though can also be found in various sects of Christianity as well as Gnosticism.

Philosophy, Porphyry vs. Iamblichus

Perhaps the most prominent figure contributing to the practice and philosophy of theurgy is the Syrian philosopher Iamblichus. He was a Neoplatonist, although he differed from earlier Platonic thinkers as he emphasized the necessity of ritual for union with the divine. Porphyry, another Neoplatonist philosopher whom Iamblichus studied under, argued for a more ascetic approach and the salvation of the soul. He also believed that unification with the One was a contemplative, introspective process, and that ritual was a distraction from this goal. Porphyry along with Plotinus felt that material was impure and could essentially corrupt the immaterial. Plotinus also stated that matter was an ontological evil. Matter was a product of the Soul which generated all life, and through the action of creation, generated matter as well. Iamblichus adopts a somewhat different approach to theurgy, arguing against Porphyry’s view of solitude and intellectualization as being what motivates the outcome of theurgy while highlighting the practical use of rituals. Furthermore, he opposes Porphyry’s denunciation of the Hellenic and Egyptian rites, which he writes of extensively in his work “On the Mysteries of the Egyptians, Chaldeans, and Assyrians.” Iamblichus reasoned that one can reach this synthesis with God by purifying oneself and navigating the various multitudes of emanation through devotional acts towards the divine and the use of symbols, characterizing this process as being cosmogonic and anagogic in nature.

Ritual

Before beginning a theurgic ritual, or any ritual involving communion with the divine, it is important to purify oneself. This is recorded extensively in various pieces of Hellenic literature at the time. The Hellenes believed in a concept called Miasma, which is a state of spiritual impurity. Miasma is accumulated through disrupting the natural order of things or going against the Gods. There is both lesser and greater miasma. For example, lying or any non virtuous act would be a form of lesser miasma. Greater miasma would include something such as killing somebody, which is why soldiers were believed to have more severe miasma. To become spiritually pure, one may enter katharsis through performing katharmos or using khernips. Katharmos is typically used when one has accumulated more serious miasma and there are records of soldiers performing it. However, khernips is used when someone has only lesser miasma. Khernips is a type of sacred water used to wash oneself in order to get rid of these impurities before ritual. The water is typically made using water from a natural source and then burning and submerging herbs into it. It is also important to note that this did not mean the Hellenes viewed themselves as naturally impure, dirty beings. As I had written earlier, the good and the beautiful descend through each level of emanation, including us. There are metaphysical vices that one must cleanse themself from. You may then wash your hands with this while repeating hymns or calling out to the divine in some way. Sunthemata, or tokens containing sympathies of the divine in the material realm, were also used to invoke a certain deity. According to Iamblichus, these tokens were intentionally weaved into the universe by the divine. Sunthemata can include anything from herbs to visual symbols. Epithets of the gods and nomina barbara are also forms of vocal sunthemata. You may also use an idol or anything containing a physical depiction of the deity. A theurgic ritual is typically a highly euphoric and fulfilling experience where one’s connection to the divine is truly centered and fully explored. Another important thing to keep in mind is Iamblichus wrote that every theurgist should perform a ritual to the extent that they can. This means, do what feels comfortable to you and what you’re confident in and be aware of your skill level. A theurgic ritual will only be effective if you have the ability and means to make it, so do not attempt to do anything extremely complex or above your level of knowledge and experience.

Relevance to Germanic paganism

Theurgy did not only exist amongst the Greeks and Egyptians, as many different cultures across the globe understood the importance of uniting with their creator. Since this account focuses heavily on Germanic paganism, it would only make sense to discuss the relevance of theurgy within these cultures. Acts of devotion are a significant part of any pre-Christian religion, especially those of sacrifices. Although I did not discuss it in this post, animal sacrifice was a crucial element to theurgy according to Iamblichus and Julian the Apostate later attempted to revive this custom. Of course, the Germanic tribes were no stranger to sacrifices whether they be for a good harvest or simply as a dedication to the Gods. This is further demonstrated when we look at the etymology of the word blót, which translates to “serving God” in Gothic. Moreover, there are several instances of deities being invoked in various charms, as I have discussed in previous articles. Idols and effigies were also used, sometimes in quite theatrical processions. For the sake of length, I won’t linger on this too much, but the idea of “God-working” is certainly there. Seeing that all Indo-European religions are interrelated in some way, it’s understandable that each culture would have some conception of uniting with God. This will be further discussed in my next blog post!

Summary

Theurgy, which translates to “God-working,” is reaching henosis or unity with the One by working through the multitudes of emanation. It’s philosophy was heavily influenced by Neoplatonist thinkers such as Plotinus and Porphyry while it’s practice was largely shaped by Iamblichus. The former argues for asceticism and contemplation while the latter pushed for the use of rituals. The Hellenes believed a theurgic ritual could be carried out upon cleansing oneself of all spiritual impurities, or miasma. This was achieved by entering Katharsis. Although theurgy specifically is of Hellenic origins, many other pre-Christian cultures all had their own idea of and method of uniting with the divine.

#paganism#neoplatonism#plotinus#porphyry#iamblichus#theurgy#gnosticism#germanic paganism#philosophy#esotericism#occult#occultism

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

MONAD by Plotinus, Porphyry, and Proclus – Gallowglass Books

#Thomas Taylor#Ken Wheeler#The Enneads by Plotinus#On The Abstinence From Animal Food by Porphyry#Elements of Theology by Proclus#Plotinus#Porphyry#Proclus#Neoplatonism#Kuba Sokólski

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gonna go become a Neoplatonic drag queen and call myself Emma Nation.

#neoplatonism#emanationism#occult shitpost#drag ideas#plotinus#why is this not a grant morrison character yet

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

«Por lo tanto, puesto que la naturaleza simple del Bien se nos ha manifestado además como primera -pues todo lo no primero no es simple- y como algo que no posee nada en sí mismo, sino como una sola cosa, y puesto que la naturaleza del llamado Uno es la misma -pues tampoco ésta es otra cosa y luego Uno, y este Uno tampoco es otra cosa y luego Bien-, siempre que digamos “el Uno” y siempre que digamos “el Bien”, hay que pensar que su naturaleza es la misma, y que la llamamos «una» no tratando de predicar nada de ella, sino tratando de mostrárnosla a nosotros mismos como podemos; que la llamamos “el Primero”, por esta razón, porque es algo simplicísimo, y “el Autosuficiente”, porque no consta de varios componentes; si no, dependería de sus componentes; y lo que decimos que no está en otro, porque todo lo que está en otro, también proviene de otro. Si, pues, tampoco proviene de otro, ni está en otro ni es ningún compuesto, síguese forzosamente que no hay nada por encima de él.»

Plotino: Enéadas, I-II. Editorial Gredos, pág. 483. Madrid, 1982.

TGO

@bocadosdefilosofia

@dias-de-la-ira- 1

#plotino#Πλωτίνος#plotinus#Ἐννεάδες#Enneades#enéadas#el bien#el uno#identificación del bien con el uno#el primero#el autosuficiente#otro#filosofía griega#filosofía helenística#época antigua#neoplatonismo#idealismo platónico#teo gómez otero

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“On the subject of that which is beyond Intellect, many statements are made on the basis of intellection, but it is contemplated (θεωρεῖται) by a non-intellection (ἀνοησία) superior to intellection; even as concerning sleep many statements may be made in a waking state, but only through sleeping can one gain knowledge and comprehension (γνῶσις καὶ κατ��ληψις); for like is known by like, because all knowledge consists of assimilation to the object of knowledge.”

— Porphyry of Tyre, Sententiae XXV

#platonism#neoplatonism#henosis#mysticism#unification#mystic union#theoria#classical philosophy#philosophy#platonic#theosis#plotinus#porphyry#iamblichus#proclus

4 notes

·

View notes