#planat de la faye

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Part two of my fav exhibits in the FC Musuem! 🇵🇱

1. Chopin’s pencil ✏️ (Before 1848)

Chopin used pencils not only to make notes in his diary, but also for drawing and to add comments to his pupils' scores. He was known to break them in anger while giving piano lessons. As Frederick Niecks, one of Chopin's first biographers, wrote: 'Madame Rubio [... informed me that Chopin was very irritable, and when teaching amateurs used to have always a packet of pencils about him which, to vent his anger, he silently broke into bits!]

I’m sure he’d break all the pencils and chairs if I were his student. 🤣

2. Chopin’s tie pins and pendant 📍

'Impeccably dressed, he wore, after the latest fashion, a navy-blue tailcoat with gold buttons, fastened over a white waistcoat, pearl-coloured trousers with clasps. A long tie, fastened with a diamond pin, encircled his neck' - wrote Chopin's pupil Georges Mathias

Choppy was very fashionable! ✨

3. A copy of Chopin’s armchair in his last apartment 🪑

This rosewood armchair is the only authentic piece of furniture belonging to Fryderyk Chopin that survived after the auction of items from the composer's last apartment. It was bought by Chopin's close friend, the artist Teofil Kwiatkowski.

4. Chopin’s portrait in 1843 (Teofil Kwiatkowski)

What a cutie!!! 😚

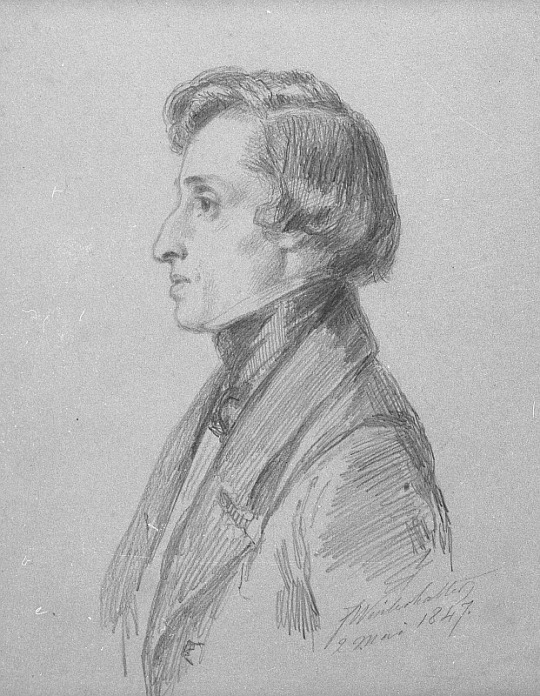

5. Chopin’s portrait (Franz Xaver Winterhalter, 1847-1861)

A portrait probably made after a pencil drawing that Winterhalter produced from nature on a May 1847. 👇🏻This one!

In a letter to his family, Chopin related: 'Yesterday I posed for Scheffer again, and the portrait is coming along. - Winterhalter has also done a small pencil one for my old friend Planat de la Faye (about whom I wrote to you once).- A very good likeness. Winterhalter is no doubt known to you by name, a good honest man of great talent'

😍😍😍

6. Chopin’s piano 🎹

Woah😚

7. Chopin on his deathbed😿 (Teofil Kwiatkowski, after 17 October 1849)

In this picture, besides Fryderyk, we see Princess Marcelina Czartoryska, Chopin's sister Ludwika Jedrzejewicz, Wojciech Grzymala, Fr Aleksander Petowicki and Kwiatkowski himself.

Aww🥹🥹🥹

8. Chopin’s travelling hat box 🎩

Choppy kept his hat in this box when travelling. He was known for his sartorial punctiliousness. In a letter to Julian Fontana, he wrote: 'apart from that, I forgot to ask you to have a hat made for me by my Dupont on your street. He has my measurements and knows what light ones I require. Have him give it this year's form, not overstated, because I don't know how you dress these days!’

Omg I don’t even know hat box is a thing, cute! 😍

9. Chopin playing the piano 🎹 (Teofil Kwiatkowski, 1847)

Urghh I love this sketch so much!! ❤️

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

He could not give more details as he was indeed not there 😊. He had been on the march to reinforce Eugène, but only arrived after the battle had ended. Macdonald actually was not with Eugène for a large part of that campaign in 1809, as he had been detached with a part of the Italian army to Ljubljana and Graz, while Eugène was crossing the Alpes in order to join Napoleon before Vienna. Napoleon then sent Eugène into Hungary in pursuit of Johann’s Austrian corps, while Macdonald, I believe, was supposed to seek contact with Marmont, who was marching up from Dalmatia but had gone missing. It was only when Eugène had located the enemy in Hungary that Macdonald received orders to join him, but too late for the battle.

Fun fact: When Macdonald had died in 1840, the eulogy held at his funeral also listed the battle of Raab among his victories (despite better knowledge, apparently). Which caused another furious outburst by Planat de la Faye in a French newspaper, defending Eugène’s memory and reclaiming that victory for his former master.

As today is the 14th of June, the threefold battle anniversary, I suspect there might be some talk about the battles of Marengo and Friedland. So I'll link to another brief report among the translations on Jonas de Neef's website - a site that I am absolutely thrilled with!

This report concerns the least known and least important of those battles, and the only one where Napoleon was not present, the battle of Raab, won by Eugène's army of Italy against the Austrians under archdukes Johann and Josef.

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(King Maximilian I. Joseph of Bavaria, by Stieler)

The attempts to sway Eugène to join the side of the Allies are particularly well-documented. Partially because of Marmont. The "Duc de Raguse", suffering for the rest of his life from accusations of having betrayed Napoleon, had written rather controversial memoirs, that were only to be published after his death in 1852. (Someone compared him to a sharpshooter hiding behind his own tombstone which is an image I really love.) He made accusations against several people; most prominent among them figured Eugène, whom Marmont accused of having disobeyed Napoleon's order to lead his troops across the Alpes to France and to defend French soil rather than Upper Italy, thus having been the real cause for the lost war of 1814.

By that time, Eugène himself was long dead, both his sons were dead, and even Auguste had died in 1851. However, his daughters protested vehemently against these accusations, and Planat de la Faye, who had only been in Eugène's service for the last brief years, fought tooth and nails to protect Eugène's memoir all his life. Eugène's family and friends actually went to court over this question (and unsurprisingly, considering by then Napoleon III ruled France, they won).

However, this was not the first time similar accusations had been made, and Auguste at earlier occasions already had collected testimonies, letters and documents in order to be able to refute them. In court, much of it became public, and some of it even had to be added to Marmont's memoirs.

That's why we have a detailed report by one prince of Thurn und Taxis, aide-de-camp to the king of Bavaria, about his mission to convince Eugène of the necessity to join the allies in mid-November 1813. The young man, who had served under Eugène's orders in Russia, was sent to Bellegarde's Austrian troops from Frankfurt, armed with a letter by King Max Joseph. It turned into a real undercover movie; the Bavarian had to put on the uniform of an Austrian major and present himself to Eugène's outposts as a negotiator sent by Bellegarde, was taken into custody and blindfolded by Eugène's Italians, led behind their lines and, after convincing them that he really, really had to talk to Eugène in person, locked into a church while they went to search their viceroy. On entering the building, Eugène immediately recognized his former subordinate and explained to his entourage that he was certain he would be safe around this gentleman and wanted to take him outside on a walk, for a one-on-one interview. In which his first question, according to the prince Thurn und Taxis, apparently was not "What the f are you doing here?" but "Is the king okay?«, before even opening Max Joseph’s letter.

For the rest, we can let Eugène speak for himself, because as usual, he immediately had to write to Auguste about the encounter.

Le prince Eugène à la princesse Auguste. Vérone, 23 novembre 1813.

Je t'envoie, ma bonne Auguste, une lettre que j'ai reçue du roi par un officier parlementaire. Cet officier n'était autre que le prince Taxis. J'ai causé plus d'une heure avec lui, et je t'assure que je n'ai dit que ce que je devais. En deux mots, il m'a apporté la proposition.de la part de tous les alliés, pour me faire quitter la cause de l'Empereur, de me reconnaître comme roi d'Italie. J'ai répondu tout ce que toi-même tu aurais répondu, et il est parti ému et admirateur de ma manière de penser; comme il a vu que je ne voulais entendre à rien qu'à un armistice, il m'a assuré que le roi l'obtiendrait d'autant plus « que les alliés admiraient mon caractère et ma conduite. » C'est déjà une bien belle récompense que de commander ainsi l'estime à ses ennemis. Déchire le billet du roi, ne parle de rien de tout cela. Dans l'armée on ne sait qu'il est venu un parlementaire que comme officier autrichien.

**

Prince Eugene to Princess Auguste. Verona, 23rd November 1813.

I am sending you, my good Auguste, a letter which I received from the King through a parliamentary officer. This officer was none other than Prince Taxis. I talked with him for over an hour, and I assure you that I only said what I had to. In two words, he came to me with a proposal on behalf of all the allies, in order to make me leave the Emperor's cause, to recognise me as King of Italy.

I answered all that you yourself would have answered, and he left deeply moved and impressed by my way of thinking; seeing that I only wanted to agree to an armistice, he assured me that the King would obtain it all the more "as the allies admired my character and my conduct."

It is already a fine reward to thus command the esteem of one's enemies.

Tear up the king's note, do not mention any of this. In the army it is only known that an Austrian officer came as a parliamentarian.

As Eugène would soon learn, this professed "esteem" his enemies had for him would not lead him anywhere. Neither did he receive an armistice from Bellegarde in 1813/4, nor a principality in 1814/5. But everybody agreed that Eugéne was a really great guy, and maybe that was worth it for him.

Eugène of course also immediately sent a detailed report of his meeting to Napoleon – for his own safety if for no other reason, so he could not be accused of secret conspiracies. It’s a rather businesslike letter, listing the content of the conversation in bullet points, but Eugène also repeatedly puts in declarations of loyalty and tries to reassure Napoleon that he will remain by his side.

The report by the prince Thurn und Taxis, written from memory in 1836, contains a lot more sighs and worrying and even tears on Eugène’s side about the future of his children. But the interesting part is that the prince claims to also have talked about Murat’s probable defection:

Finally, when as a last argument I began, as my instructions prescribed, to speak to him of the fairly clear willingness that King Joachim had shown to deal with the allied sovereigns, and when I added that before six weeks his right flank would be exposed, compromised perhaps, the Prince said to me: "I like to believe that you are mistaken; if, however, it were so, I would certainly be the last to condone the conduct of the King of Naples; still the situation would not be exactly the same: he is sovereign, I, here, am only the lieutenant of the Emperor."

So, in a way even Eugène recognized that Murat’s actions, if possibly questionable from a moral standpoint, were justified by the fact that Murat was an independent king, bearing responsibilty for the well-being of his country. Whereas Eugène could shed this responsibilty; after all, he was only following orders, and thus his line of conduct was never in doubt.

Plus, Eugène always knew that, even if he himself went down with Napoleon, his family had a safety net in their Bavarian royal relations. Murat had no support among the other European nations, unless he joined their cause. Napoleon’s two “Italians” were indeed in very different situations.

#eugene de beauharnais#joachim murat#napoleon#italy1813#italy1814#marmont#napoleon's marshals#bavaria#king max joseph#planat de la faye

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi ! Who was Eugène friends with throughout his life and were there people with whom he was not so friendly? How was your relationship with your wife's family? Thank you!

Hi there, and thanks for the question! Also, please bear with me, ´coz this is going to be lengthy.

Eugène's position changed a lot over the years but there are some people, usually not well-known, who will remain friends with him throughout all his life.

During the Consulate, Eugène was something like everybody's darling. This was partly due to his position as stepson of the new chief of state. First Consul Bonaparte increasingly resembled a monarch, and Eugène, the son of Madame Bonaparte,was the closest thing to a crown prince there was. Eugène's biographer Michel Kérautret emphasises how much he (and in a different vein his sister) were seen as the »next generation of France«. Eugène commanded one of the most famous regiments, the Chasseurs au Cheval de la Garde, and was universally admired. Little boys looked at him with big eyes when he walked by. Besides, he was completely apolitical, only interested in women, horses and the army, and could therefore be invited by anyone. As long as there was music and dancing, Eugène was happy.

His closest friends also came from the ranks of the army. His probably best friend is hardly known: Auguste Bataille (de Tancarville), later Baron of the Empire and one of Eugène's aides-de-camp. Napoleon was not very enthusiastic about him and his abilities. (If I remember correctly, poor Bataille once had the misfortune to have a thief steal the briefcase with the documents he was supposed to bring to Napoleon. Eugène then got a nasty letter saying "Don't send me that idiot any more!")

Auguste Bataille remained in Eugène's service until his death in 1821. He is the one Eugène sends to Napoleon in 1809 to report the arrival of the Armée d'Italie in Austria (when Eugène was probably expecting the thrashing of his life and instead received a hero's welcome). But he is also the one whom Eugène's sister and wife turn to when they want news of Eugène and he himself has no time to write, so clearly someone who is quasi-family. When Eugène had to leave Italy, Bataille, who was married there, remained behind to administer Eugène's Italian properties. He died in 1821, and when Planat de la Faye asked Eugène for a job in 1822, Eugène explicitly referred to the late Bataille and said "You have seen who else belongs to my entourage. Bataille was my friend and the only one I could really rely on - I want someone like that again." (Planat de la Faye will take this job very seriously and later defend Eugène's memory like a bloodhound).

Just to mention a few other people who became important to Eugène since his time in Italy and who also accompanied him to Munich into exile: his cousin Louis Tascher and his wife, his adjutant General Triaire and the family of his former secretary for political affairs, Etienne Méjean and his only remaining son. After Eugène's death, Eugène’s children will grow up with the children of Méjean Jr.; they will call them "Papa Méjean" and Grand-Papa Méjean".

Let's move on to more prominent people. Among the marshals, Eugène's best friend was clearly Bessières. Bessières had been Eugène's superior since Egypt and remained so until Eugène went to Italy as viceroy. Apparently Napoleon had tasked Bessières with taking Eugène under his wing (or perhaps just with preventing his overzealous stepson from accidentally killing himself in the Sahara in an attempt to somehow distinguish himself). This resulted in a friendship that lasted for years. Eugène called Bessières "tu" in his letters, even when he had become prince and viceroy; there are apparently over a dozen letters to him in the "Archives Nationales", which are according to the description "of a predominantly private nature". After returning from Egypt, Eugène and Bessières shared a house in Paris (and apparently the two also plunged into Paris nightlife together). Eugène also accompanied Bessières when the latter visited his fiancée in Cahors and repeatedly sent his regards to Madame Bessières. After Bessières' death, there were several letters of condolence between Eugène and Bessières’ widow. In his memoirs, Eugène defended Bessières against some accusations that Lannes had made against him after the battle of Marengo. (One would think that this would have been time-barred by 1823).

Duroc, from whom Eugène sometimes sent greetings in his letters to Hortense, completed the trio of friends (but Duroc seemed to get on well with everyone). Eugène recounts in his memoirs how Duroc once stopped him from literally sleeping through his duty in Egypt; later they lay wounded side by side in the military hospital outside Acre (Duroc, however, considerably worse). When Eugène was left all alone and clueless in Milan as Viceroy of Italy (that was how he saw the matter), Duroc seems to have been the only one who regularly looked after him and wrote to him. Apparently Duroc and Eugène also "shared" the attentions of a young lady from the stage (Emilie Bigottini). Later, whenever Napoleon was particularly angry with Eugène (which happened with a certain frequency), he did not write to him himself, but had someone else write; usually it was Duroc. Duroc was also the one who delivered the marriage proposal to Eugène's prospective father-in-law. When Eugène was in Vienna in 1809, he wrote an enthusiastic letter home to his wife because he had finally, for the first time in three years, been dining together with Bessières and Duroc! (Funnily enough, Bessières wrote almost the same letter to his wife).

However, Eugène's oldest friend among Napoleon's close collaborators, who even became his relative, was Lavalette. When Eugène, not quite 16 and just out of school, went to Italy as Napoleon's adjutant, the first Italian campaign was basically over. Napoleon sent his stepson to Corfu with dispatches (and explicit orders to get some rest and sightseeing there), and gave him Lavalette as an escort. Before the Egyptian campaign, when Lavalette was to ask for the hand of Emilie de Beauharnais, Eugène had to chaperone him and his cousin for a walk, only to remember that he had urgent business elsewhere and leave them alone. Lavalette was also among those whom Eugène continued to address as "tu" in his letters after he was promoted to viceroy. And after Lavalette narrowly escaped execution in the Second Restoration, he took refuge with Eugène in Bavaria, where Eugène and King Max more or less successfully hid him.

I'm limiting this to Eugène's male friends, by the way. Female acquaintances are another matter altogether.

Who did Eugène not get on so well with? Quite a lot of people, interestingly enough, consideringhe is described in almost all sources as incredibly amiable, patient and sociable.

There is, of course, his rivalry with Murat, the exact origins and background of which would interest me immensely. The two were actually in a very similar position from 1810 on at the latest, but rather than communicating with each other, the two seem to have been constantly at each other's throats. I have the impression that Murat made a timid attempt at reconciliation now and then, and that at this stage Eugène was the one who no longer wished to hear anything from Murat. Probably because he held Murat responsible for Napoleon's separation from Josephine.

And only to avoid any false impression: Murat and Eugène also called each other "tu" when they met in private. But in their official correspondence, they almost suffocate from the pompous phrases they throw at each other.

Someone Eugène did not get on with at all was Marshal André Masséna. For this, I think alot of things came together: a social background that couldn't be more different, and perhaps a sense of class superiority on Eugène's part. On the other side, Masséna, who had really fought his way up from the gutter by his own efforts, was unlikely to have taken seriously this brat who, thanks to his stepdad, was allowed to play viceroy in Italy. Eugène, for his part, with his rather naïve attitude to war, was horrified by Masséna's ... rather creative approach to the subject of requisition and his general attitude to "mine" and "yours". In 1805 he complained bitterly about the way Masséna and his men had plundered the Italians they were supposed to protect, and Masséna actually had to pay back a huge amount of money. In 1809, Eugène desperately wanted no marshal (it would probably have been Masséna) to be sent to Italy, but to be allowed to take command himself. When the battle of Sacile promptly turned into a disaster, Napoleon told him pointedly that this would not have happened with Masséna, Masséna’s plundering notwithstanding.

Similarly, Eugène clashed with Auguste Marmont. This was also about money, financial trickery and personal enrichment. On this point, Eugène did not joke (and presumably this was precisely the reason why Napoleon had appointed him as overseer in Italy). The friction with Marmont developed into an enmity that lasted truly until after the death of the two adversaries, or rather only really erupted there: Marmont accused Eugène in his posthumously published memoirs (not entirely without reason, but in a rather exaggerated manner) of having been the main reason for Napoleon's defeat in 1814, and Eugène's daughters and Planat de la Faye (see above) then took the editor of the memoirs to court. Absolutely crazy.

From his correspondence, I take it he also at least once discovered Bourienne’s financial shenanigans in Hamburg.

I unfortunately do not know how his relationship with Marshal Lannes was (but I would love to know). My gut feeling says: probably similar to Masséna. Eugène does mention Lannes twice in his memoirs, both times respectfully. But I have not come across any personal interaction or correspondence between them at all. As Lannes was close to Murat and somewhat at odds with Bessières, he’s unlikely to have been friends with Eugène.

As this has gotten so long already, I’ll stop here and put anything about Eugène’s Bavarian in-laws into an extra post at a later date. Just so much for now: If this was Facebook, I’d pick »It’s complicated«.

#eugene de beauharnais#napoleon#auguste bataille#etienne méjean#jean baptiste bessières#jean lannes#antoine marie lavalette#geraud christophe michel duroc#andré masséna#auguste marmont

67 notes

·

View notes

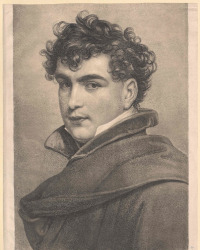

Photo

This, btw, was the same Planat de la Faye who would after Napoleon’s death come to Munich in order to serve as Eugène de Beauharnais’ private secretary and who would years later vehemently defend (late) Eugène’s memory against (late) Marmont’s accusations.

I observed, during the whole time of breakfast, that Colonel Planat, who was much attached to him, and of whom Buonaparte always expressed himself in terms of affection, had tears running down his cheeks, and seemed greatly distressed at the situation of his master. And, from the opportunities I afterwards had of observing this young man’s character, I feel convinced he had a strong personal attachment to Buonaparte;—and this, indeed, as far as I could judge, was the case also with all his other attendants, without exception.

— Surrender of Napoleon by Frederick Maitland. Drawing by Nicolas-Louis Planat de la Faye on July 24, 1815.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon has returned from Elba and made it to the Tuileries. Here, Planat de la Faye relates what happened to Gourgaud at this joyous time.

When I went down to the service lounge, the first person I saw was Gourgaud in full officer's uniform. "Hey," I said to him, "are you no longer ill?" He replied: "The arrival of the Emperor has restored my health." He seemed cheerful, he laughed and made jokes to which no one responded. However, this good countenance did not last long; the Emperor having refused to see him, it concluded with immense grief, which did not prevent him from installing himself, somehow or other, in a small room in the attic of the palace. He remained there eight days without being able to achieve his ends. He abandoned himself without any constraint to his sorrow: he cried, and swore every day that he was going to blow his brains out if the Emperor did not want to see him again. We went with [Armand de] Briqueville from time to time to console him, telling him to be patient, that with the Emperor there's never complete disgrace, which was true, that he always turned around eventually. Indeed, after this eight-day ordeal, Gourgaud received the prize for his perseverance. He obtained his pardon and subsequently the confirmation of his rank of colonel, and the title of first ordnance officer, because he was the only one left from the old promotion of 1812-1813.

—le Général Gourgaud by Jacques Macé

#someone else told this anecdote I think#Gourgaud's drama#return from Elba#100 Days#Gourgaud hadn't gone to Elba so Napoleon was a bit miffed#I didn't realize that Napoleon actually knew Gourgaud extremely well

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

I posted 696 times in 2021

230 posts created (33%)

466 posts reblogged (67%)

For every post I created, I reblogged 2.0 posts.

I added 1.176 tags in 2021

#napoleon - 361 posts

#joachim murat - 192 posts

#napoleon's marshals - 171 posts

#eugene de beauharnais - 158 posts

#caroline murat - 71 posts

#napoleon bonaparte - 54 posts

#napoleon's family - 50 posts

#naples - 43 posts

#marie louise - 39 posts

#josephine de beauharnais - 37 posts

Longest Tag: 119 characters

#is there another justification for the existence of monarchs than the fact they provide entertainment through scandals?

My Top Posts in 2021

#5

I imagine Napoleon would be thrilled with today's means of communication. I could easily see him calling Soult every two minutes during the Battle of Austerlitz to make sure that the attack on Pratzen Heights would really happen.

45 notes • Posted 2021-07-09 21:08:24 GMT

#4

Hi ! Who was Eugène friends with throughout his life and were there people with whom he was not so friendly? How was your relationship with your wife's family? Thank you!

Hi there, and thanks for the question! Also, please bear with me, ´coz this is going to be lengthy.

Eugène's position changed a lot over the years but there are some people, usually not well-known, who will remain friends with him throughout all his life.

During the Consulate, Eugène was something like everybody's darling. This was partly due to his position as stepson of the new chief of state. First Consul Bonaparte increasingly resembled a monarch, and Eugène, the son of Madame Bonaparte,was the closest thing to a crown prince there was. Eugène's biographer Michel Kérautret emphasises how much he (and in a different vein his sister) were seen as the »next generation of France«. Eugène commanded one of the most famous regiments, the Chasseurs au Cheval de la Garde, and was universally admired. Little boys looked at him with big eyes when he walked by. Besides, he was completely apolitical, only interested in women, horses and the army, and could therefore be invited by anyone. As long as there was music and dancing, Eugène was happy.

His closest friends also came from the ranks of the army. His probably best friend is hardly known: Auguste Bataille (de Tancarville), later Baron of the Empire and one of Eugène's aides-de-camp. Napoleon was not very enthusiastic about him and his abilities. (If I remember correctly, poor Bataille once had the misfortune to have a thief steal the briefcase with the documents he was supposed to bring to Napoleon. Eugène then got a nasty letter saying "Don't send me that idiot any more!")

Auguste Bataille remained in Eugène's service until his death in 1821. He is the one Eugène sends to Napoleon in 1809 to report the arrival of the Armée d'Italie in Austria (when Eugène was probably expecting the thrashing of his life and instead received a hero's welcome). But he is also the one whom Eugène's sister and wife turn to when they want news of Eugène and he himself has no time to write, so clearly someone who is quasi-family. When Eugène had to leave Italy, Bataille, who was married there, remained behind to administer Eugène's Italian properties. He died in 1821, and when Planat de la Faye asked Eugène for a job in 1822, Eugène explicitly referred to the late Bataille and said "You have seen who else belongs to my entourage. Bataille was my friend and the only one I could really rely on - I want someone like that again." (Planat de la Faye will take this job very seriously and later defend Eugène's memory like a bloodhound).

Just to mention a few other people who became important to Eugène since his time in Italy and who also accompanied him to Munich into exile: his cousin Louis Tascher and his wife, his adjutant General Triaire and the family of his former secretary for political affairs, Etienne Méjean and his only remaining son. After Eugène's death, Eugène’s children will grow up with the children of Méjean Jr.; they will call them "Papa Méjean" and Grand-Papa Méjean".

Let's move on to more prominent people. Among the marshals, Eugène's best friend was clearly Bessières. Bessières had been Eugène's superior since Egypt and remained so until Eugène went to Italy as viceroy. Apparently Napoleon had tasked Bessières with taking Eugène under his wing (or perhaps just with preventing his overzealous stepson from accidentally killing himself in the Sahara in an attempt to somehow distinguish himself). This resulted in a friendship that lasted for years. Eugène called Bessières "tu" in his letters, even when he had become prince and viceroy; there are apparently over a dozen letters to him in the "Archives Nationales", which are according to the description "of a predominantly private nature". After returning from Egypt, Eugène and Bessières shared a house in Paris (and apparently the two also plunged into Paris nightlife together). Eugène also accompanied Bessières when the latter visited his fiancée in Cahors and repeatedly sent his regards to Madame Bessières. After Bessières' death, there were several letters of condolence between Eugène and Bessières’ widow. In his memoirs, Eugène defended Bessières against some accusations that Lannes had made against him after the battle of Marengo. (One would think that this would have been time-barred by 1823).

Duroc, from whom Eugène sometimes sent greetings in his letters to Hortense, completed the trio of friends (but Duroc seemed to get on well with everyone). Eugène recounts in his memoirs how Duroc once stopped him from literally sleeping through his duty in Egypt; later they lay wounded side by side in the military hospital outside Acre (Duroc, however, considerably worse). When Eugène was left all alone and clueless in Milan as Viceroy of Italy (that was how he saw the matter), Duroc seems to have been the only one who regularly looked after him and wrote to him. Apparently Duroc and Eugène also "shared" the attentions of a young lady from the stage (Emilie Bigottini). Later, whenever Napoleon was particularly angry with Eugène (which happened with a certain frequency), he did not write to him himself, but had someone else write; usually it was Duroc. Duroc was also the one who delivered the marriage proposal to Eugène's prospective father-in-law. When Eugène was in Vienna in 1809, he wrote an enthusiastic letter home to his wife because he had finally, for the first time in three years, been dining together with Bessières and Duroc! (Funnily enough, Bessières wrote almost the same letter to his wife).

However, Eugène's oldest friend among Napoleon's close collaborators, who even became his relative, was Lavalette. When Eugène, not quite 16 and just out of school, went to Italy as Napoleon's adjutant, the first Italian campaign was basically over. Napoleon sent his stepson to Corfu with dispatches (and explicit orders to get some rest and sightseeing there), and gave him Lavalette as an escort. Before the Egyptian campaign, when Lavalette was to ask for the hand of Emilie de Beauharnais, Eugène had to chaperone him and his cousin for a walk, only to remember that he had urgent business elsewhere and leave them alone. Lavalette was also among those whom Eugène continued to address as "tu" in his letters after he was promoted to viceroy. And after Lavalette narrowly escaped execution in the Second Restoration, he took refuge with Eugène in Bavaria, where Eugène and King Max more or less successfully hid him.

I'm limiting this to Eugène's male friends, by the way. Female acquaintances are another matter altogether.

Who did Eugène not get on so well with? Quite a lot of people, interestingly enough, consideringhe is described in almost all sources as incredibly amiable, patient and sociable.

There is, of course, his rivalry with Murat, the exact origins and background of which would interest me immensely. The two were actually in a very similar position from 1810 on at the latest, but rather than communicating with each other, the two seem to have been constantly at each other's throats. I have the impression that Murat made a timid attempt at reconciliation now and then, and that at this stage Eugène was the one who no longer wished to hear anything from Murat. Probably because he held Murat responsible for Napoleon's separation from Josephine.

And only to avoid any false impression: Murat and Eugène also called each other "tu" when they met in private. But in their official correspondence, they almost suffocate from the pompous phrases they throw at each other.

Someone Eugène did not get on with at all was Marshal André Masséna. For this, I think alot of things came together: a social background that couldn't be more different, and perhaps a sense of class superiority on Eugène's part. On the other side, Masséna, who had really fought his way up from the gutter by his own efforts, was unlikely to have taken seriously this brat who, thanks to his stepdad, was allowed to play viceroy in Italy. Eugène, for his part, with his rather naïve attitude to war, was horrified by Masséna's ... rather creative approach to the subject of requisition and his general attitude to "mine" and "yours". In 1805 he complained bitterly about the way Masséna and his men had plundered the Italians they were supposed to protect, and Masséna actually had to pay back a huge amount of money. In 1809, Eugène desperately wanted no marshal (it would probably have been Masséna) to be sent to Italy, but to be allowed to take command himself. When the battle of Sacile promptly turned into a disaster, Napoleon told him pointedly that this would not have happened with Masséna, Masséna’s plundering notwithstanding.

Similarly, Eugène clashed with Auguste Marmont. This was also about money, financial trickery and personal enrichment. On this point, Eugène did not joke (and presumably this was precisely the reason why Napoleon had appointed him as overseer in Italy). The friction with Marmont developed into an enmity that lasted truly until after the death of the two adversaries, or rather only really erupted there: Marmont accused Eugène in his posthumously published memoirs (not entirely without reason, but in a rather exaggerated manner) of having been the main reason for Napoleon's defeat in 1814, and Eugène's daughters and Planat de la Faye (see above) then took the editor of the memoirs to court. Absolutely crazy.

From his correspondence, I take it he also at least once discovered Bourienne’s financial shenanigans in Hamburg.

I unfortunately do not know how his relationship with Marshal Lannes was (but I would love to know). My gut feeling says: probably similar to Masséna. Eugène does mention Lannes twice in his memoirs, both times respectfully. But I have not come across any personal interaction or correspondence between them at all. As Lannes was close to Murat and somewhat at odds with Bessières, he’s unlikely to have been friends with Eugène.

As this has gotten so long already, I’ll stop here and put anything about Eugène’s Bavarian in-laws into an extra post at a later date. Just so much for now: If this was Facebook, I’d pick »It’s complicated«.

53 notes • Posted 2021-06-02 16:51:38 GMT

#3

“A Montagnard sans-culotte”

This may be something for once that could interest also the »neighbours« from the Frev era. Maybe somebody from there could even give more details on this? It’s a letter by future empress Josephine from November 1793.

As mentioned here in a brief excerpt of Eugène’s memoirs, his uncle, Alexandre Beauharnais’ older brother François, had been a staunch royalist. He fled the country, if I remember correctly, at the end of 1792. One year later, in November 1793, his (former, as she divorced him in 1793) wife Marie-Françoise (mother to the famous Emilie who would later become Madame Lavalette and save her husband from prison during the Second Restauration) was arrested and taken to the Prison de Sainte-Pélagie. Future Josephine, still named Rose at the time, tried to intervene on behalf of her sister-in-law with Marc Guillaume Alexis Vadier, member of the »Comité de la Sureté générale«. As he refused to see her, she wrote him a letter – as it seems, more defending herself and her whole family than her imprisoned sister-in-law specifically.

Unfortunately, the tone of the letter (translated from Chevallier/Picemaille “L’impératrice Josephine”] cannot be accurately reproduced in English; Josephine, of course, addresses this high official throughout with the confidential, or in this case republican, "tu".

Since it is not possible to see you, I hope that you will be kind enough to read the memorandum which I enclose here. Your colleague told me of your severity, but at the same time he told me of your pure and virtuous patriotism and that, despite your doubts about the good citizenship of the ci-devant, you are always interested in the unfortunate victims of error.

I am persuaded that on reading the memorandum, your humanity and your justice will make you take into consideration the situation of a woman unhappy in all respects, but solely for having belonged to an enemy of the Republic, to Beauharnais the elder, whom you knew and who, in the Constituent Assembly, was in opposition with Alexandre, your colleague and my husband. I would be very sorry, Citizen Representative, if you confused in your thought Alexandre with Beauharnais the elder. I put myself in your place: you must doubt the patriotism of the ci-devant, but it is in the range of possibilities that, among them, there are ardent friends of Liberty and Equality.

This is actually an interesting phrase. Josephine here clearly assumes that it is indeed the fact that she and her relatives all are ex-nobles that endangers their freedom and their lives. So, apparently she already thought that »the Revolution wants to kill the nobles«, before any »Thermidorian propaganda«?

Alexandre has never deviated from his principles: he has always walked a straight line. If he were not a republican, he would have neither my esteem nor my friendship.

Also an interesting phrase, considering the couple had been living separated for years at that time.

I am an American and know only him of his family, and if I had been allowed to see you, you would have been cured of your doubts. My household is a republican household: before the Revolution, my children were not distinguishable from the sans-culottes, and I hope they will be worthy of the Republic.

I am writing to you honestly, as a Montagnard sans-culotte. I only complain about your severity because it deprives me of seeing you and having a little conference with you. I ask you neither favour nor grace, but I claim your sensibility and your humanity in favour of an unfortunate citizen. In spite of your refusal, I applaud your severity as far as I am concerned, but I cannot applaud your doubts about my husband. You see that your colleague has repeated to me everything you told him: he had doubts as well as you, but, seeing that I lived only with republicans, he stopped doubting. You would be just as fair, you would stop doubting if you had wanted to see me.

Farewell, esteemed citizen, you have my confidence.

Lapagerie-Beauharnais

Josephine may not be Josephine yet but she is clearly already doing what she will later excel in, working her »social net« as her biographer Pierre Branda calls it. She has connections in both royalist and revolutionary circles. As for Alexandre, he had apparently been close to one François Chabot, recently imprisoned due to corruptions apparently on a scale even exceptional and unbearable for those times. I assume that’s the reason for both Vadier’s suspicions and Rose-Josephine’s attempt to clear her family’s name.

(I must admit the more names I look up in Wikipedia, the more disgusted I am with this era. A lot of factions full of strong men who are all afraid of each other, trying to get each other out of the way, using other people as pawns. Oh, and enriching themselves as much as possible, of course.)

So, getting back to Marie-Françoise de Beauharnais, the lady in prison: As Josephine could not procure any help from one of her friends in higher-up circles, what were her options? Except for sitting in prison, hoping nobody would incite another mob riot in order to free up some space there? According to Hortense’s memoirs, when both her parents were imprisoned, she and her brother would bring them fresh clothes but were never allowed to see them nor even to write to them (which probably occasioned the nice little anecdote about ugly pug Fortuné taking letters to Josephine); in order to let them know they were still alive, they took turns in writing the laundry list enclosed in the package, so they would at least see both their handwritings. Can people from the FRev era confirm this, is this a credible detail? As soon as somebody had been arrested, what could they do in order to defend themselves? Was anybody even interested in hearing them? What was the point in imprisoning family members of émigrés, except trying to seize those people’s property or intimidate other people?

57 notes • Posted 2021-11-17 03:18:30 GMT

#2

About Marie Louise

Yes, Marie Louise, once more. I'm not sure if tumblr really is the best forum for this but I would love to hear people's thoughts. When I did the posts on Marie Louise's honeymoon trip I realized to my own surprise that I had actually read several things about her already. There's a German biography of her, plus Vial's edition of her diaries, plus a book of her last letters to Napoleon (though admittedly I only got that one because it has three letters by Eugene). Not to mention all the stuff online. And yet I actually don't have a grasp of who this woman was. In German sources she's usually depicted as the martyr, the "virgin sacrificed to the Corsican ogre", who, however, then committed the unforgivable sin of not following her husband into whatever quagmire he got himself into - which does not make much sense. And in French sources she's simply the woman who chose one Neipperg over Napoleon. 'Nuff said. Both sides condemn her for mistreating her oldest son. So, I wondered: At what points in her life could and should she have acted differently, when did she have other options and what were her reasons for not doing it?

61 notes • Posted 2021-08-25 05:02:50 GMT

#1

I really liked those “classic art in modern setting” pics. So I tried to do my own. Nap, Berthier and Jojo have their first encounter with modern means of transportation.

102 notes • Posted 2021-08-26 14:00:19 GMT

Get your Tumblr 2021 Year in Review →

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

How did Eugène occupy his time after 1814? Did he have any responsibilities or functions, or was he put in mothballs?

First of all, thanks for the question. Eugène’s final years, those ten years of agony that, ostensibly, were filled with nothing but joy and pleasure, are a sad story. But if you want the short version: yes, mothballs, mostly. Or as Eugène put it later to Planat de la Faye: »I have sacrificed my independance for the sake of my family.«

Let’s start at the beginning: In 1814, after Josephine’s death, Eugène left France for good. Despite the fact he still owned both Malmaison and Navarre he would never be allowed to return to his country of birth. After leaving wife and children in Munich, he joined the Congress of Vienna in order to receive that »suitable« principality that was to be given to him according to the treaty of Fontainebleau. He is, to my knowledge, the only »napoleonide« to go to Vienna in person.

His situation there is best summed up in a diary entry by archduke Johann, his former opponent in the war of 1809, about Eugène’s obligatory courtesy visit:

1815, October 3: Beauharnais. I quite liked this man […] He has acted most honestly of all the French; how must he feel; he a few months ago at the head of Italy, now barely a French marshal, begging for some piece of land […]

As Eugène would soon realize, he was indeed reduced to begging, and beggars can’t be choosers. I’ll leave out all the humiliations during the congress, or this will turn too long. In the end, he nominally received his principality: Ponte-Corvo. Yes, Bernadotte’s former principality. It was, however, clear that Eugène would not accept it, but immediately sell it off for, according to Auguste, »12 millions«. With that money, he could settle down whereever he pleased and whereever people wanted to have him (which excluded France, from where Napoleon’s family was exiled).

Eugène chose Bavaria, in order to please Auguste, and because he could expect this country would be the least hostile to him. He was right, as far as regular people and king were concerned, who both loved him dearly. Not so much about nobility and crown prince though.

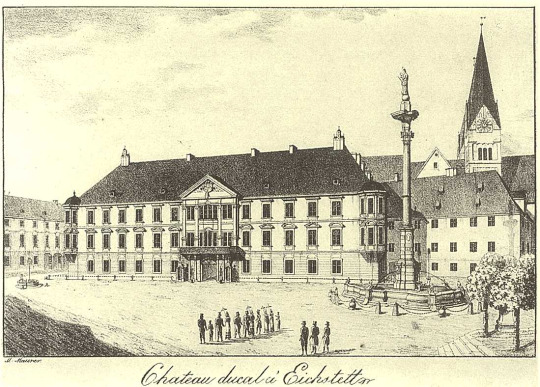

The relationship between Ludwig of Bavaria and his French brother-in-law is a topic of its own, and I do not know enough about Ludwig to be able to truely comment. Let’s just say that as crown prince, according to the law, he did already have some say in matters of the state, and when King Max Joseph wanted to make Eugène and his children official members of the royal family, i.e., a new branch of the house of Wittelsbach, he intervened. There were family disputes and public humiliations for the pesky French brother-in-law. At one point, Eugène was so fed up he wanted to leave the country, leading to workers rioting in front of Ludwig’s house. In the end, Max Joseph had to give in. He gave Eugène a principality (Eichstätt), the title of a duke (Leuchtenberg) and a status of »first prince after the Royal house of Wittelsbach«, with the rights of a mediatised prince. That was in October 1817.

Just for comparison’s sake: The Kingdom of Italy had had about 6 million inhabitants. Eichstätt had 24,000. The principality also was deficient, it had no real economy to speak of and would always cost Eugène more than it earned him.

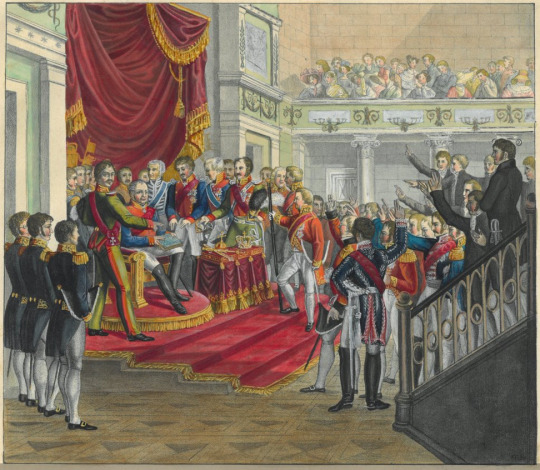

But he now was at least officially a nobleman of the country – or as his French biographer Françoise de Bernardy put it, he had found his »corner in the world«. His very, very small corner of the world. He did take part in all court activities, built himself a representative palace in Munich, where he had brilliant parties and receptions, thus ostensibly claiming his former rank, was officially declared colonel of a regiment of chevaux-legers (the 6th, »Leuchtenberg«-regiment), and he belonged to one of the chambers of the Bavarian parliament (Landtag). He even can be seen taking an oath to the Bavarian constitution of 1818 among the Royal princes in the drawing below (in truth, even this was vetoed by Ludwig, Eugène took his oath together with the other nobles).

He did take part in the sessions of the Bavarian parliament and at least once held a speech in German (which was duely noted in all the newspapers!) but in general his personal situation and his lack of language skills prevented him from playing an active role. Auguste was already mortified to see Eugène get involved in politics at all, especially as in the matter concerned Eugène did not agree with his father-in-law and sole protector (Max Joseph wanted to weaken the role of the parliament, Eugène wanted to strengthen it). She would always fear that at some point the family would be chucked out of this refuge they had found.

She needn’t have worried. With that incredible Beauharnais tact, Eugène, a changed man ever since the fall of the empire, overweight, taciturn, circumspect, managed to die one year before king Max Joseph and before, under new king Ludwig I., his person would have become a real burden for his family. He suffered his first stroke during mass of Holy Thursday 1823, then briefly recovered during summer and finally gradually got worse until his death on February 21, 1824.

I have left out his relations with Napoleon on Saint Helena as I am not fully clear about them myself, and in any case, those were hardly political except in the eyes of all the foreign observers and secret agents who seem to have panicked whenever Eugène was seen or even only suspected of doing ... anything.

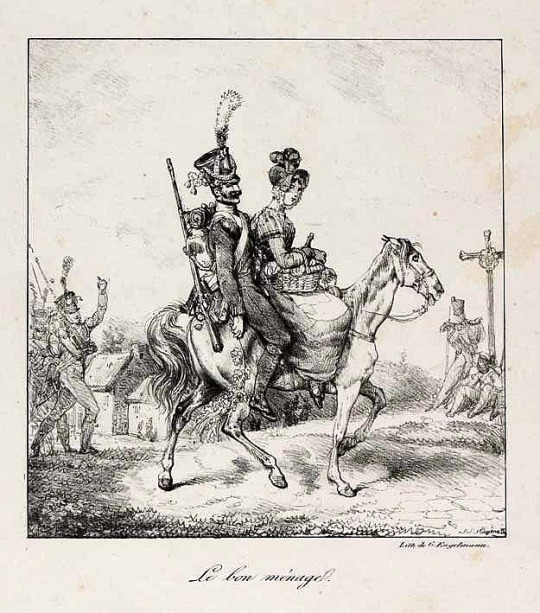

A drawing by Godefroy Engelmann that, if not directly done by Eugène, seems to be based on a sketch by him, according to the museum of Malmaison, hints at the fact that Eugène was quite aware of what was in store for him:

That would be a French soldier deserting his comrades calling after him, led by his wife to a future where a cross (Auguste was indeed very religious) rises above some faceless figures.

Or as he told Planat: »My position here is fake and entirely dependent on the king.«

#eugene de beauharnais#kingdom of bavaria#bavaria#congress of vienna#auguste von bayern#ludwig i#king max joseph

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the favorite historical figure ask game: may I ask you about 7,8, 11 and 12?

7. Let us know three random facts about them!

Possibly already known by some: Eugène briefly worked as an apprentice to a joiner when he was twelve, after both his parents had been arrested during the Terror and he was left behind with his sister and her governess. It seems he rather enjoyed himself, at least according to Hortense, who claims that Eugène’s master was a staunch republican, but also hid his two sisters, former nuns, in his house (who doted on Eugène and presented him with little religious pictures). The catalogue of an exhibition in Malmaison in 1999 has a photo of a small box fabricated by »le Prince Eugène, Duc de Leuchtenberg«, which would indicate that he may have taken woodworking up as a hobby later.

According to Planat de la Faye, Eugène once told him some time before his death that, if he had had a say in the matter, he would have loved to be a sailor.

When Eugène had been exiled to Bavaria, he was not officially a member of the royal family, but factually. In a newspaper article I found a nice episode: The Bavarian family visited a rather weird sports competition at a public park: runners had to carry heavy stones in their hands behind their back over a longer distance. As their hands got numb, they often lost these stones without noticing, continuing their course without them to the amusement of the audience. - You guess which not-quite-a-member of the royal family had to try that out himself… Eugène also became a member of the Bavarian »Landtag« (a form or parliament) and even held a speech in German (which was duly noted in all the newspapers!).

8. When did you hear of them for the first time and what was your first impression?

I’m pretty sure I heard about Eugène already somewhen in school and found his figure rather chivalrous. I’ve always had a penchant for (complicated) father-son-relationships. But I only really got interested in him when we went on a guided tour through Munich and ur guide told us the funny story of that one Wittelsbach princess who was SO in love with her fiancé but had to give him up in order to marry Napoleon’s stepson, and how that princess cried and wailed and lamented and dropped unconscious … until the horrible Frenchman stood in the door and she was like »Hey, hold a second! Noone told me they also come like that! Leave that one here!«

11. What is your favourite portrayal of them in fiction (e.g. movies, novels etc.)?

Truely, there is none that particularly stands out. Eugène plays such a small role in the huge napoleonic saga that you have to be happy to find him mentioned in novels at all, and I have not read many of those. (Eugène has brought me back to writing, if that counts.) I liked him in Sandra Gulland’s »Josephine« trilogy, though. As for movies – same thing. If he does show up at all, it’s usually as a child, for the obligatory »saber« event, and then he disappears. Which of course is a result of these movies usually focusing on the »big« battles: Austerlitz, Jena, Friedland etc., and Eugène did not take part in those. Honorable mention: The »Napoleon and Love« series with Ian Holm, in which Eugène is played by – Tim Curry. Which goes perfectly with the overall craziness of that show.

12. Let us know the three best books about your favourite historical figure!

My favourite biography is in German and, to my knowledge, has only partially been translated into French: Adalbert von Bayern, »Eugen Beauharnais«. It’s quite old and in some aspects even outdated but it really covers both Eugène’s qualities and his flaws, and it usually cites its sources neatly.

Recently added: Michel Kerautret, »Eugène de Beauharnais. Fils et vice-roi de Napoléon«. This book covers in particular the political aspect much better, evaluates the role that Eugène played in Napoleon’s »system« and also has more information on sources that were discovered after Adalbert’s death, like Eugène’s last letters to Napoleon on Elba and the role Eugène played during Napoleon’s captivity in Saint Helena.

And finally a book that is rather critical of him: Françoise de Bernardy, »Eugène de Beauharnais. Le fils adoptiv de Napoléon«. It has some letters from Eugène’s youth and also has a closer look at the relationship with Josephine.

Thanks a lot for asking!

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eugène and his Bavarian family

This is the second part of the answer to the question by @mademoisellewhistler about Eugène's friends, this time dealing with Eugène's relatives by marriage, the royal family of Bavaria. Thank you once more for the Ask.

(Max Joseph, his second wife Karoline and their five daughters, painting from 1821)

***

Let's start with his spouse, Auguste. In short, she adored him. After having yielded in tears to the raison d'état and sacrificed herself for the fatherland (her own words) at Christmas 1805, she apparently realised rather quickly that she had not made a bad bargain when she gave up her cousin Charles. At the end of May 1806, Eugène for the first time had to leave her for a few days, and she whined about it in letters to anyone who would listen, Napoleon included. (Napoleon must have been quite puzzled by this; things had been very different in his own marriage).

After all, who could have guessed that this totally unacceptable bridegroom would turn out to be such a nice guy?

Napoleon was otherwise not very successful as a marriage broker, but this marriage, which he had coerced, actually turned out to be very happy, and my impression is that he was immensely proud of it. However, he was to suffer as a result of this success, because Auguste soon felt that her Eugène was getting the short end of the stick compared to Napoleon's brothers and brothers-in-law. Napoleon charged him with most of the work, but the royal crowns and honours went to other people. From the time of his divorce from Josephine at the latest, she was not at all well disposed towards Napoleon. But that is another story. Even the loss of his position could not change her affection for Eugène. On the contrary, we have some of the most touching letters between them from this period.

Next, Eugène’s father-in-law, King Max Joseph of Bavaria. In short, he adored him. If Auguste hadn't married Eugène, Max would probably have done it himself, just to keep this guy in the family. This was exactly the son he had always wanted, handsome, polite, cheerful, well-mannered, brave soldier and, above all, French! (And what had fate given him instead? Crown Prince Ludwig.) Eugène and Max Joseph were, in Auguste's opinion, very much alike in many ways; no wonder they got on well together. Max took a lively interest in all things concerning Eugène and Auguste; when Auguste finally gave birth to their long-awaited son in 1810, he wrote from Munich that he had not been able to sleep all night because of his excitement and happiness at the news. Normally I would consider this a rhetorical phrase; in Max's case it is probably to be understood literally.

The relationship between Eugène and Max Joseph seems, as far as can be deduced from the letters, to have been more family-like than that between Eugène and Napoleon. Towards Napoleon, Eugène always maintains a very submissive, respectful tone; Napoleon is always "Sire" and "Votre Majesté". But he addresses Max as "Mon bon père", my good father, and in his letters to Auguste he likes to speak of "notre père", our father, referring to Max.

I have already written about the negotiations that took place between the two of them in 1813/4, even though they belonged to opposing camps.

They also quarrelled - once, over Tyrol. Max Joseph did not agree at all with a proclamation that Eugène had published, and wrote to him about it. Whereupon Eugène wrote to his wife almost in despair, oh crap, crap, crap! Now I've quarrelled with your father over this thing, I hate this Tyrol!

(The disgruntlement did not last long.)

Eugène's early death hit Max Joseph hard. According to Planat de la Faye, he never afterwards referred to his son-in-law as anything other than "mon pauvre Eugène", my poor Eugène.

Crown Prince Ludwig. In short, he hated him. Or possibly not. Unless he did. In any case, he hated everything French and in particular everything connected with Napoleon, which at least at times certainly included his French brother-in-law. He got so upset about his sister's forced marriage to the unworthy Beauharnais that he wrote a play about the matter over the next few years (a tragedy, some of it being unintentionally funny if you know the actual story).

Of course, the guy, on the other hand, was very very nice. But that didn't change the fact that he was French. "Of all the Frenchmen, Eugène is probably still the best," Ludwig is supposed to have said. This was probably the greatest compliment Eugène could expect from his brother-in-law.

In part, Ludwig's dislike may have been jealousy. Ludwig and Max Joseph did not get on at all; Ludwig probably feared that Eugène would replace him with Max. Napoleon did not make matters any better when he occasionally pointed out that crown princes could also be shot for disobedience and that, after all, Eugène's children were also grandchildren of the Bavarian king.

On top of that, Max Joseph and Auguste had the idea that good-natured Eugène should speak to Ludwig's conscience from time to time about Ludwig’s attitude towards the French Emperor, his frequenting of dubious taverns and the good behaviour of crown princes in general. Eugène did it, as he did almost everything he was told, but it did not go down well at all with Ludwig.

When Eugène finally ended up in Bavaria after the fall of the Empire, the rivalry escalated to the point where Louis wanted to duel him (he was quick with duel demands - he knew full well that someone would always stop it). He prevented Eugène's children from becoming part of the royal family, and it almost came to the point that Eugène and his family would have left Bavaria again. In the end, Auguste wrote a bitterly blunt letter to her brother, and they came to an arrangement.

And, as I said, Eugène was a terribly nice guy. Besides, he had bought a small castle outside Munich, in Ismaning, at just the right distance from town to ride out there in the morning and then have breakfast with sister, brother-in-law and nieces and nephews ... which Ludwig, when he was in Munich, did regularly. Apparently his aversion to all things French did not extend to breakfast.

Queen Karoline of Bavaria, second wife to Max Joseph and stepmother to Auguste. Which I guess makes her Eugène’s stepmother-in-law? In short: Undecided. In theory, she couldn't stand Eugène. In theory, she never forgave him for stealing her little brother's bride. In theory, she was forbidden to like the guy if only because he was Napoleon's stepson and she didn't like Napoleon, being sister to the tsarina. But in practice it was always so hard to keep up that dislike once you met him, with him being so damn charming.

When Eugène came to Bavaria, relations were quite strained, especially between Auguste and Karoline. On the other hand, Eugène simply became part of the family. There are touching letters from Karoline about Eugène's death, in which she describes in detail to her mother how he was no longer able to speak at the end and took her hand and put it on his heart to say goodbye ... when reading this, one has the feeling that she was truely very touched and that she really had to get something off her chest.

By the way, there was a second source of conflict between Eugène and Karoline: Karoline's sister, Friederike, was the wife of ousted King Gustav of Sweden. And Eugène married his daughter to the son of the "usurper" Bernadotte. Karoline was not happy about this.

Auguste’s younger brother, Karl Theodor, called »Charles« in the family. He was still a child when Auguste left for Italy but seems to have liked Eugène from the beginning. In spring 1813, when Eugène was at the head of what was left of the Grande Armée, Karl Theodor wrote him an urgent letter and begged that Eugène would call him to the army as his ADC. Eugène, having his hands full with generals who turned blind and deaf with shock when orders came in, and soldiers who broke down in fear at the word "cossack", wrote back politely but firmly that now was a very bad time. Maybe later, when war resembled war again.

During his time in Bavaria, Karl Theodor was one of Eugène's friends in Munich, but he was only the second son, with future King Ludwig calling the shots. Eugène made him executor of his will.

How Auguste's younger sister Charlotte, the family's ugly duckling, viewed Eugène, I don't know, but she seems to have been more on Ludwig's side. Auguste's younger half-sisters, born of Max Joseph's marriage to Karoline, were close in age to Eugène's children, with whom they often played together. It is said of Ludwig's eldest son, the future King Maximilian II, that he always retained very positive memories of his French uncle, especially because Eugène was the exact opposite of the authoritarian, stubborn and stingy Ludwig.

And then there is somebody who was not officially part of the family, but factually: Auguste's old governess, Madame de Wurmb, called "Machère", whom Eugène had, so to speak, co-wed. "Machère" had substituted for Auguste's mother, deceased at an early age, and meant a great deal to her. Throughout her life, she kept a strict regime over her former pupil and, since she accompanied Auguste to Italy as a lady-in-waiting, also over Auguste's husband. Planat de la Faye, who met her in 1822, gives a rather amusing description of her. She had still been brought up in "Ancien Régime" Paris and lived entirely according to its principles (or what she regarded as its principles). When, after the end of the Empire, Eugène and Auguste travelled to Baden with very little luggage and entourage for financial reasons, and Eugène helped his wife into the carriage himself for want of a servant, the world came to an end for Madame de Wurmb ...

"Machère" probably never really forgave Eugène for daring, as a mere Beauharnais, to marry "her" princess. But she had to acknowledge that he made Auguste very happy, and that most of the time he really did behave as if he were a real prince (or what Machère regarded as one).

Eugène's biographer Adalbert of Bavaria suggests that Napoleon advised Eugène upon his marriage to first take the old governess to Italy and then throw her out as soon as possible. Which, of course, good-natured Eugène never did. There is a very funny anecdote about the first meeting between "Machère" and Napoleon, which Napoleon himself reported and which I will reproduce here soon anyway. In his letters to Auguste, Napoleon sent greetings to the lady every now and then - or maybe that was his way of finding out if the old dragon was still there and if it was already safe to visit Italy...

#eugene de beauharnais#napoleon#king max joseph#auguste von bayern#karoline von bayern#max joseph#eugene's marriage#ludwig i#bavaria#munich

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I observed, during the whole time of breakfast, that Colonel Planat, who was much attached to him, and of whom Buonaparte always expressed himself in terms of affection, had tears running down his cheeks, and seemed greatly distressed at the situation of his master. And, from the opportunities I afterwards had of observing this young man's character, I feel convinced he had a strong personal attachment to Buonaparte;—and this, indeed, as far as I could judge, was the case also with all his other attendants, without exception.

— Surrender of Napoleon by Frederick Maitland. Drawing by Nicolas-Louis Planat de la Faye on July 24, 1815.

17 notes

·

View notes