#permian period animals

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Some of my favorite permian period creatures:

- GORGONOPSIDS

- Coelurosauravus

- Eryops

- Dimetrodon

- Lystrosaurus

- Scutosaurus

Also Heliocoprion gets a shoutout here because of how terrifying that creature looked.

What are your favorite ancient Permian creatures?

#permian period#permian period animals#ancient#paleontology#paleoblr#extinct animals#gorgonopsid#Coelurosauravus#Eryops#dimetrodon#lystrosaurus#Scutosaurus#Heliocoprion

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

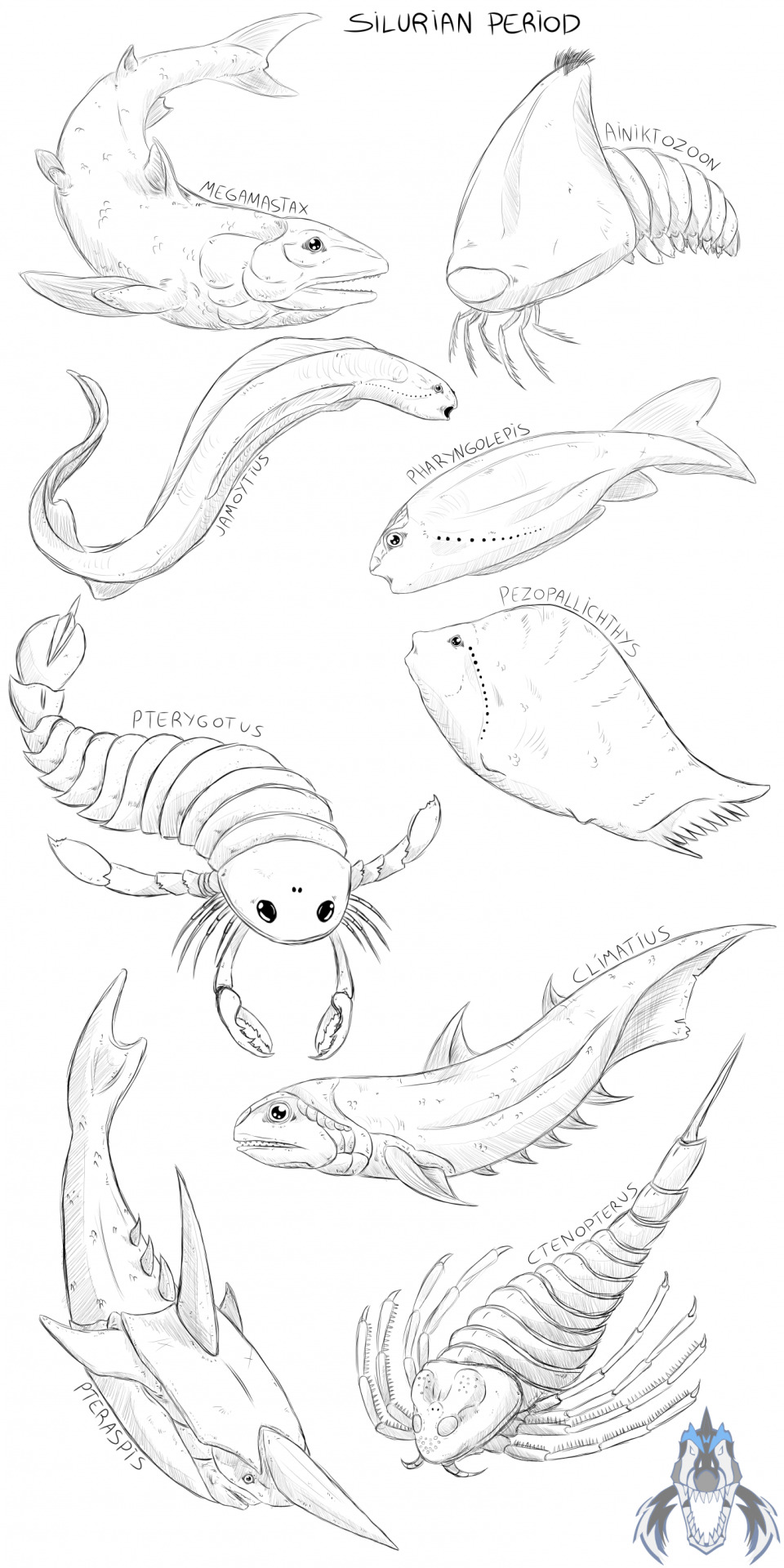

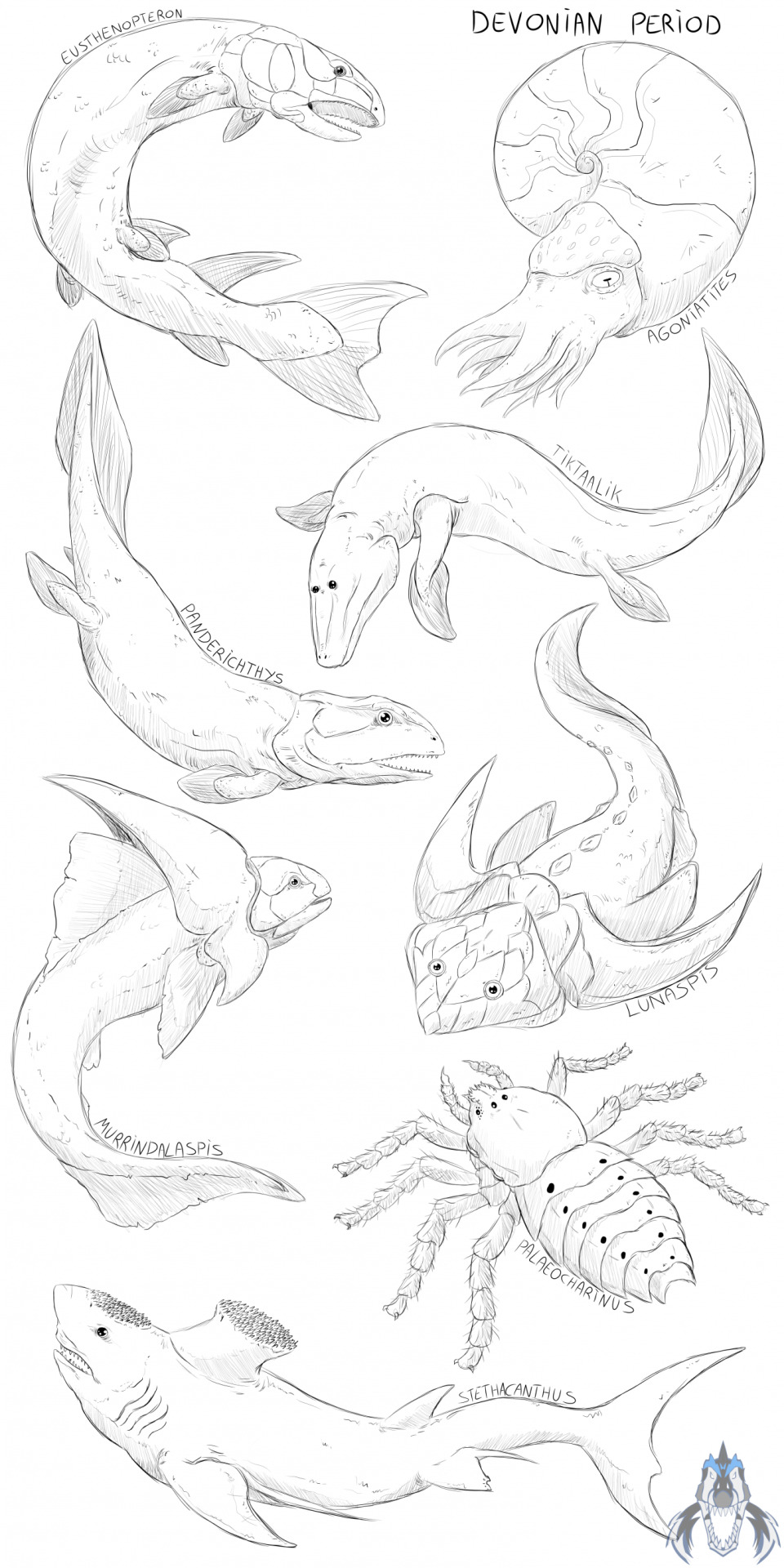

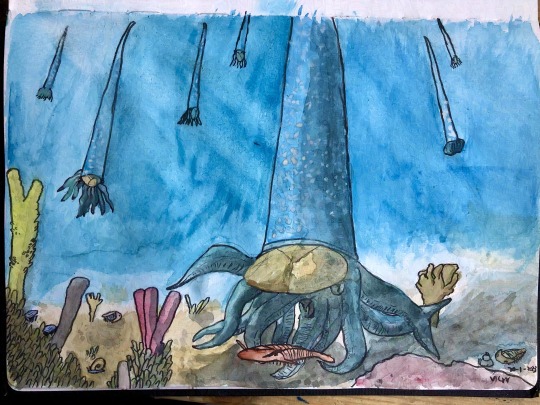

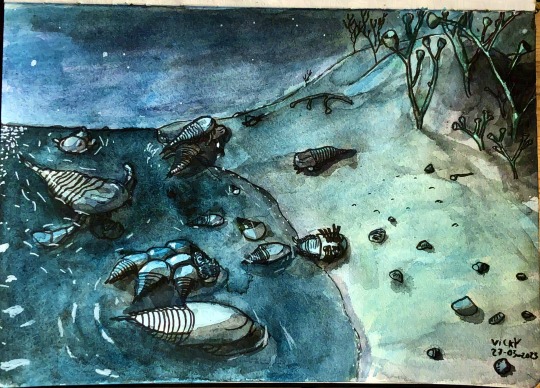

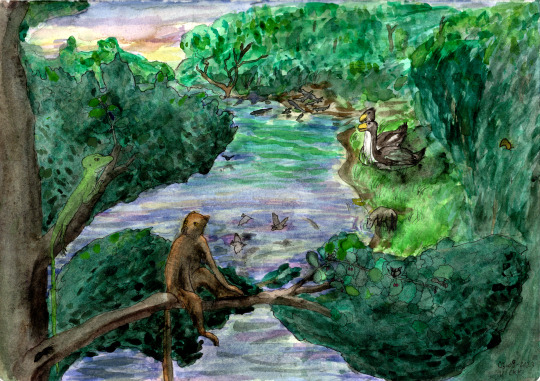

Repost of my paleozoic fellas drawings

#paleozoic#paleozoic era#cambrian period#ordovician period#silurian period#devonian period#carboniferous period#permian period#prehistoric animals#prehistoric fellas#paleozoic era deserves more attention

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

Walking in the Lower Fremouw Formation

Back to the dawn of the Mesozoic Era, Walking in the Lower Fremouw Formation.

View On WordPress

#adobe photoshop#antartica#artistatwork#Commissions Open#Concept Art#cynodont#cynodonts#Dicynodont#Digital Art#DigitalPainting#Environment Design#landscape#landscape art#Landscape Painting#Lystrosaurus#paleo art#paleontology#Palo Art#pangea#permian#prehistoric animals#prehistoric life#protomammals#Thrinaxodon#Triassic#Triassic Period#Wacom Tablet

1 note

·

View note

Text

"The Entity" is the first and most powerful organism in our planet's history. It has witnessed and regulated every era of life on this planet. When the earth population becomes rather unruly, it intervenes; breaking out of its usual dormant state to initiate a rather brutal regulation process. The Entity transfers all of its energy into a small embryotic form, lying in wait for an unsuspecting creature to devour it.

Upon being consumed, the assimilation process begins and the entity mutates its host into a giant titanic organism; "Gojira" as it has been referred to in modern times. Throughout earth's lifespan, The Gojiras have been responsible for most of earth's extinction events, the greatest of which was caused by one known as "Primordius" from the Permian/Triassic era. The monsters pollute the atmosphere sending down toxic rain and fog that poison at most 90% of life.

The one known failed instance of a Gojira Level Event was set during the late cretaceous period when the subject known as "Penultimus" was struck by an asteroid before it could fully initiate the extinction process

While the process of mutation takes roughly a few centuries to complete, due to scientific medaling, subject "Proximus" underwent scientific experimentation. The result of which caused the animal to mutate into a Gojira within a week while also creating a rather...unorthodox extinction event.

673 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anisopleurodontis - a shark-like fish from the Permian period, related to the famous Helicoprion. Found in the same fossil formation as Prionosuchus, it lived in rivers, lakes or maybe even swamps in Brazil ~270 million years ago, being the second-largest predator there. Although smaller than Prionosuchus, these two predators likely coexisted peacefully, focusing on smaller prey to avoid direct conflict. However, occasional clashes between them may have happened, especially over shared resources.

Unlike Helicoprion, Anisopleurodontis had teeth and mouth not as specialized for hard-shelled prey, allowing it to puncture soft-bodied organisms. Fossil evidence shows wearing on these teeth, suggesting it could also fed on shelled animals, indicating a flexible diet.

#3d#paleoart#paleontology#shark#anisopleurodontis#prionosuchus#brazilichtys#prehistoric#blender#lowpoly#animal#brazil

158 notes

·

View notes

Text

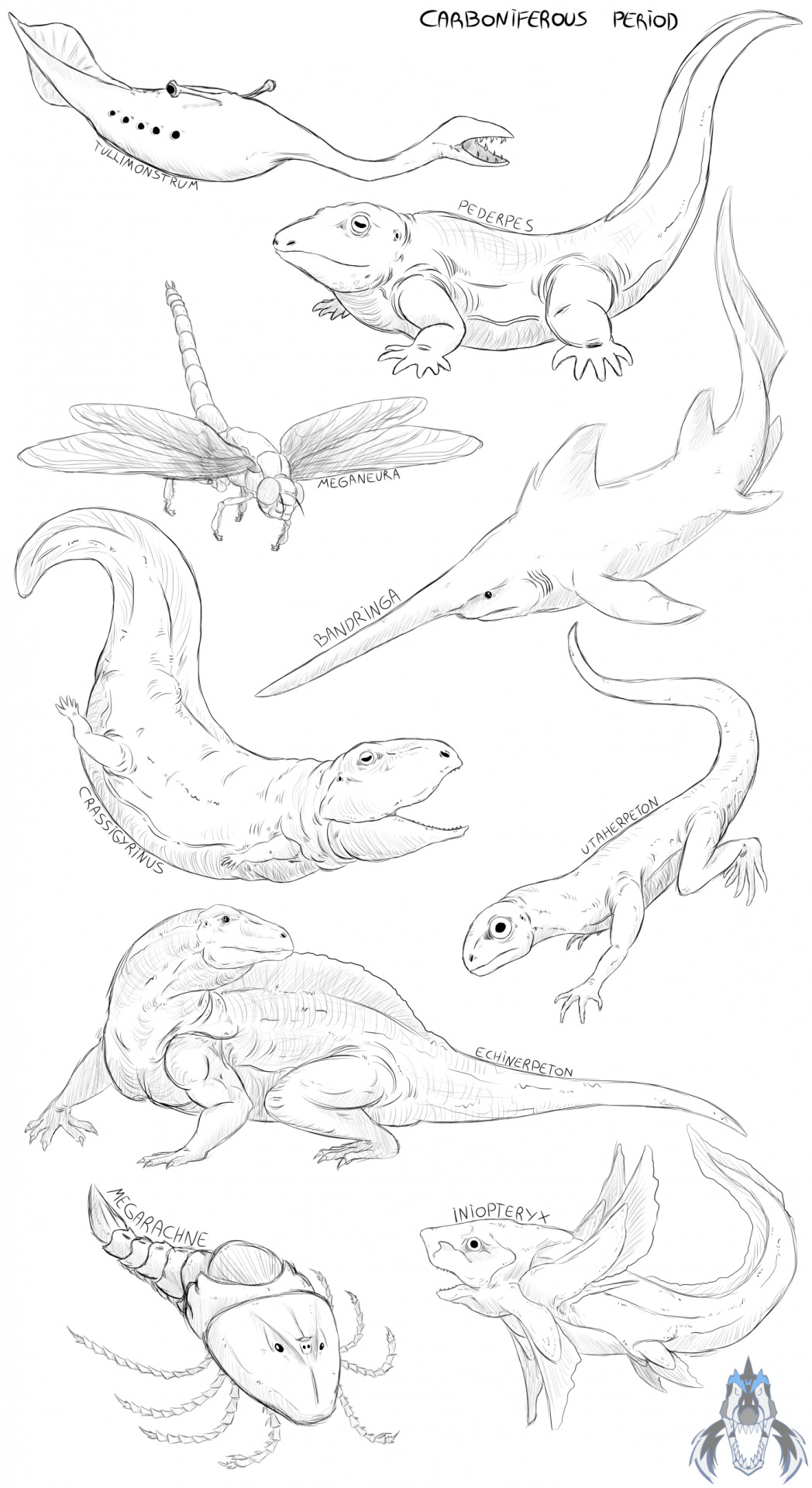

Meig's Comprehensive Guide to Reptiles, aka: the vast majority of land vertebrates

Welcome! This is another long post by me, one of tumblr's most annoying resident paleontologists. But I promise: it'll be fun, it'll be engaging, and you'll be glad you read it.

What the Everloving Fuck is a Reptile?

Well, back in the day, you probably learned reptiles were land animals, with backbones, that were covered in scales, were cold-blooded, and laid eggs with hard shells.

But, you see, we classified organisms based on traits back when we didn't know about evolution. Or prehistoric life. And turns out, there are a lot of things in the past that do not fit in the categories we made based on living things today. A lot of things.

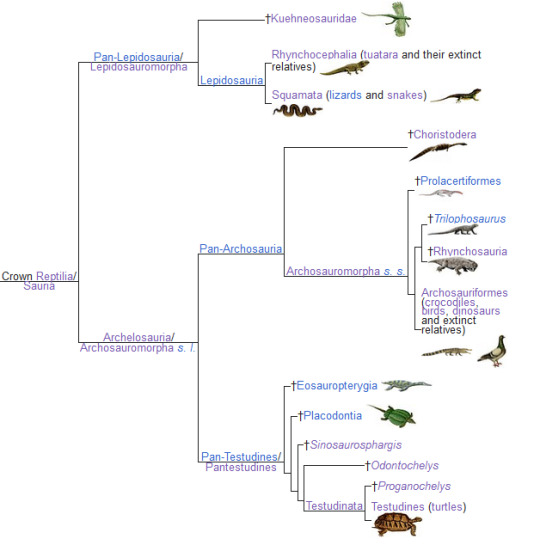

Soooooooo... now we classify based on evolutionary relationships! Aka, family trees.

So what is a reptile?

A reptile is any animal more closely related to living crocodilians (Crocs, Gators, etc.) than to rodents.

Aka, back around ~330 million years ago, animals that laid land-adapted eggs split into two groups: Proto-Mammals (that would eventually become mammals), and Reptiles.

So, a reptile is, anything closer to the group of "classical reptiles" than to mammals. Simple enough. And it is the entirety of an evolutionary unit - a single clade, consisting of a common ancestor and *all* of that ancestor's descendants.

Turns out, this includes birds, but I'll get to that.

The First Reptile Group to Branch Off: Parareptiles

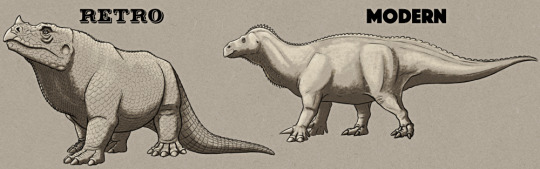

So now we go through our groups of reptiles based on their evolutionary/familial relationships, and the first group to branch off from other reptiles were the Parareptiles.

(Note: Their evolutionary history is in flux and it's possible they're actually further down on the reptile tree, or not even a natural group. for now, we're going to go with them as the earliest branching group and assume they're a single thing, even though that is probably going to be very wrong in the next few years).

These were weird mfers, living from around 310 million years ago until 200 million years ago. They had robust bodies that were low to the ground, with legs *usually* sprawled out on either side. They also had very robust and broad skulls. Many of them look superficially like lizards, in that they're quadrupedal animals with limbs splayed out to the sides, but they were *nothing* like lizards. While early members of the group had long tails, over time, the bodies of parareptiles became more stout with shorter tails. They also had swollen, thick vertebrae, and stout upper limb bones. They were CHONKY.

The earliest members to branch off were the Mesosaurs, a small group of aquatic reptiles! They were long and slender, and quite small compared to later aquatic reptile groups. The next group to branch off were Millerettids, which were small insectivores with superficially lizard-like apperances. Most Parareptiles were Procolophonomorphs, and included everything from the bipedal Eudibamus to the huge Pareiasaurs that were major megafaunal herbivores during most of the Permian period.

All Parareptiles, as far as we can tell, are extinct today. Unless their evolutionary relationships change. Yay science!

All the rest of reptiles are in Eureptilia, which have smaller bones in the lower back of the skull that no longer connect to the roof of the skull. So, skulls like living reptiles!

Captorhinids

The next group to branch off are the Captorhinids, a group of interesting little reptiles with shorter tails, sprawling limbs, and weirdly boxy heads. Living from 300 to 252 million years ago, they started out as small carnivores, and eventually evolved to be large herbivores!

Protorothyridids

Next to branch off are the Protorothyridids, which lived only in the latest Carboniferous. They were small, superficially lizard-like animals, but their limbs were a lot more slender and long than lizards, as were their bodies and heads. In fact, they seemed to have been adapted for climbing trees, making them among the earliest known animals to do so!

All remaining reptiles are Diapsids, characterized by having two holes (postorbital fenestrae) behind the eye socket. This is where all living reptiles are.

Araeoscelidans

Our first group of Diapsids are the Araeoscelidans, which - again - were SUPERFICIALLY lizard like. I cannot stress enough that nothing so far has been an actual lizard. In fact, they had more slender limbs, longer tails, and less specialized heads than lizards. That said, they probably lived similarly to them, though some members may have been adapted for climbing, and others for swimming.

Unfortunately, we're now at the part of the tree where evolutionary relationships are a mess. Parareptiles may actually go here, or only some of them. Lots of different groups diverged here very quickly. It's a messssss. I will go through each group, but just know all we know is that these groups fall outside the next big chunk - Sauria - but within Diapsids.

Younginidae

Younginids are reptiles from right around the End-Permian extinction, basically only living in the latest Permian and earliest Triassic. They were as big as living monitors, and they had less kinetic (mobile) skulls than living reptiles. They would have been superficially lizard-like - again - but very different, and they had ridiculously long tails and toes, making them powerful movers.

Tangasaurids

Tangasaurids were a weird group of end-Permian to earliest Triassic animals, with some adapted for aquatic life in freshwater and lake environments, and other living life on land like other reptiles. As such, Tangasaurids represent another experiment in secondarily-aquatic life among reptiles. The land dwellers had long toes for efficient land movement, while the aquatic ones had those amazing water adapted traits that we associate more with living species. In fact, some of their tails were flattened, like sea snakes today!

Longisquama

For the sake of my sanity, I'm trying to group things up in as few groups as possible without ignoring anything. But this is a weirdo, and it doesn't have any family members, so I have to talk about it alone. You know that reptile you may have seen in books with the hockey-stick like things coming off of its back? That's Longisquama. The problem is, we don't know much about it. It had a small, slender head, and a typical reptile body, with limbs splayed out to the sides. Those fins on the back were *not* like feathers, but something else entirely - maybe just elongated scales. Or maybe it died on top of a plant (unlikely). Many bad scientists point to this animal and say its the ancestor of birds, but that's been thoroughly debunked at this point. It lived in the Middle Triassic, around 235 million years go.

Thalattosaurs

Thalattosaurs were Triassic reptiles - so living between 252 and 200 million y ears ago - that were semiaquatic! They had long, narrow skulls adapted for grabbing fish, and slender bodies for moving through the water. Their tails were long and paddle-like. Some of them had long necks, while others had shorter necks. Some even had a hook-like end of the snout for trapping slippery fish prey! They ate many different things, with a few species adapted for crunchy marine food, others for slippery, and so on.

Ichthyosauromorphs

Some of the most famous extinct reptiles go in this group - the group of reptiles that essentially evolved to be dolphins before dolphins were even a thing - a classic case of convergent evolution. These marine reptiles were extremely successful, living from the beginning of the Triassic - 252 million years ago, possibly even older - until the middle of the Cretaceous, 90 million years ago. We have early forms that show only partial adaptations to marine life, but they very quickly became fully aquatic, even giving birth to live young under water. Some of the largest marine animals ever fall into this group, including Shonisaurus and Shastasaurus. The earliest members showcase the evolution from typical reptile-shape to the weird reptile-dolphins they would become. Proper Ichthyosaurs had big eyes, round bodies, long narrow heads, and four flippers - one for each limb. Their tails were also long and ended in a fin like living sharks and whales. Some even had a dorsal fin! This group is *huge*, so I recommend digging into their wikipedia pages to learn more! Note that these are their own, huge, distinct group of reptiles - completely separate from lizards *or* dinosaurs!

Claudiosaurus

Claudiosaurus is another unique, who knows where it goes reptile, and it showcases another shift into aquatic life for reptiles during the end-Permian mass extinction. It was 60 centimeters long, and had flippers on its feet. It probably couldn't move very much on land, so it would have lived most of its life in the water. Its tail, torso, and neck were all very long, while its head was on the smaller side. Its limbs were also quite long compared to its body size. So this was a weird animal - and we're not sure where it falls in the story of marine reptiles yet. More research on this critter is needed!

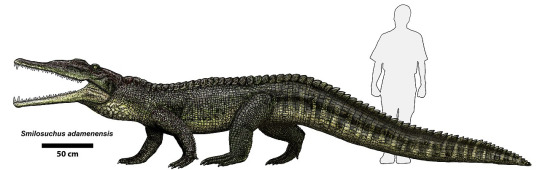

Choristoderes

Choristoderes were semiaquatic, unplaceable reptiles that varied a lot in size over their time and managed to live through to the Miocene - so they existed from sometime in the Triassic to as recently as 11.6 million years ago! Some were as small as 30 centimeters, while others grew up to 5 meters. They were convergently similar to living crocodilians, with bodies built for semiquatic life and long narrow skulls for grabbing fish. In fact, their heads are kind of weird looking - like a heart at the base with a long projection coming off of it, if you look at it from the top. They had very simple teeth, and thin overlapping scales that were probably very soft in life. They also had webbed feet! They were exclusively fresh water animals, and may have had eggs that hatched immediately after being laid. It's wild we missed them being extant by like... a blink of an eye geologically.

Weigeltisaurids

Reptiles have evolved gliding membranes from their ribs multiple times, and this is the first one we're talking about in this article. They lived at the end of the Permian, between 259 and 252 million years ago - only going extinct in the mass extinction, though a possible Triassic fossil is known. They were not close to lizards or dinos, but had a lot of convergently similar traits to lizards. The lower ribs, aka modified gastralia, are pulled out to the side in pairs of long hollow rods, which would have supported a gliding membrane that was controlled by the abdominal muscles. They were big, which made them less efficient gliders than living gliding lizards. Their heads were very triangular, and they had extremely long tails.

Sauropterygia

Okay, so this group is going in "miscellaneous reptiles" because currently their evolutionary origin is in flux. We used to think they were close to the lizard and snake group, which we'll get to at the end of this post (long way to go). Then we thought they were close to turtles, and we didn't know where turtles went, so they were kind of in limbo. Then we figured out turtles were closer to crocodilians and birds than to lizards and snakes, so we dragged Sauropterygians there with them. And now studies are indicating that Sauropterygians and Ichthyosauromorphs are closely related, along with a bunch of other marine reptiles. And sometimes that group comes outside of crown-reptiles (Sauria, in a sec), and sometimes that group comes into the close to crocs and birds group like turtles. I don't know. I don't know where they go. They're going here.

Anyways, Sauropterygians includes a lot of weird marine reptiles. Helveticosaurs may be in this group - they had wide torsos, short limbs and tails, and a small square head, and were early marine reptiles during the middle Triassic. Saurospharigds may also go here - this group were superficially like turtles, but they were actually convergently similar, not related to living turtles closely at all (unless all Sauropterygians are?). They had elongated flat vertebrae on their backs, with matching chest ribs, to form a rib basket. Placodonts are the first definite group of Sauropterygians, which were *also* weirdly turtle-convergent. Some members of this group had huge scutes on their bodies, for part or all of their torsos, to protect them - different anatomically from turtle shells, but similar looking from a distance. They had teeth built for crushing shellfish, and had long tails to aid with swimming. Many members just looked like typical marine reptiles, however, and did not have those shells that later members had. Nothosaurs were Sauropterygians with long necks and tails and limbs that still had toes and were capable of going on land, but were more similar to the famous Plesiosaurs than the Placodonts were. Their feet were webbed, they ate primarily fish and squid. Pachypleurosaurs were similar, but had longer necks and limbs that were unable to go on land. The next group, Pistosaurs, had full flippers on their limbs, and long necks with triangular heads. This includes all Plesiosaurs, aka "Loch Ness Monsters", as well as things like Liopleurodon - many forms had very long necks, while many others had short necks, all across this group. Sauropterygians lived for the whole of the Mesozoic, showing up in the Early Triassic and lasting until the very end of the Cretaceous, and lived worldwide.

Drepanosaurs

In the Triassic, a group of mystery reptiles - possibly in this group of not closely related to anything today weirdos, possibly closer to crocs and birds - that truly showcase the weirdness of the Triassic Period. Living between 230 and 201 million years ago, Drepanosaurs had very long bodies, with flexible limbs and hands adapted for grasping branches, including opposable toes on the foot and giant claws on the hands. Their heads were very small and triangular. They had a hump on their upper backs to allow for strong muscle attachments, giving them the ability to rapidly catch insects in midair. The tails of some species ended in a freaking extra claw. In short, they were generic reptiles - or almost-archosaurs - trying their damnedest to be monkeys. And they got terrifyingly close. Some had heads that were so convergently bird like that they confused bird researchers for years, but it was convergence - in fact, the beaks of Drepanosaurs are completely different anatomically.

SAURIA

If we defined reptiles above as everything closer to living reptiles than to living mammals - ie, the most inclusive group that has crocodiles but does not have mammals - this is the *least* inclusive group that still includes every living reptile. So like, Sauropsida - where we started - is like a huge clan, with only some surviving members, but the most recent grandparent those ancestors shared was not the start of the clan, it was later on in the clan's history. I hope that made sense. Anyways, this is the group we call Crown-Reptiles.

And it, by that definition, has to include birds. Because birds and crocodilians are more closely related to each other than either are to lizards and snakes. Saurians first appeared at the end of the Permian, and diversified like crazy during the Triassic when all the niches opened up after the Great Dying. We can thank the End-Permian extinction for the sheer diversity of reptiles we have in the fossil record *and* today! Because while all those lovely friends from before were great - including the ones that persist to the Jurassic - most reptiles? Are in Sauria. There are so. Many. Reptiles. In fact, today, over 20,000 species of animals are reptiles! Mammals are only 5,513 species, and living amphibians are at 7,302. Among tetrapods, Reptiles are King! Saurians come in two groups: Archelosaurs, and Lepidosauromorphs.

ARCHELOSAURIA

The first division of Saurians is Archelosauria, the group that consists of Turtles, Crocodilians, and Birds, and *all* of their extinct relatives. For a while the position of turtles was uncertain - were they the only surviving Parareptiles? Were they cousins of Lizards? But genetic data has revealed that they go with what we call "Archosaurs" - Ruling Reptiles - the group of crocodilians and birds. How their fossil relatives are or are not a part of that story is where the mess remains. Archelosaurs come in two main flavors: Pantestudines, and Archosauromorphs.

Pantestudines

All living turtles, and everything closer to them than to any other living thing, go in this group. Turtles are truly bizarre animals, because their shells are unique among animals and not repeated by any other group. During development, ribs grow sidewise into a ridge along the back, entering the skin and supporting the carapace, which is made of dermal plates that form a hard shell, that is then covered in scutes made of keratin. The lower ribs, or gastralia, along with the collar bones, extend to form the Plastron, or lower shell. The lower shell flattens out and extends on the sides to connect with the carapace. Scutes also cover this side of the shell. It's just *weird*. Turtles are just *weird*. They originally evolved from aquatic ancestors, such as Odontochelys; though some forms became secondarily terrestrial again, with many lines of the group going back and forth - making this a rare example of a secondarily aquatic tetrapod returning to the land! Turtles laugh in the face of biome preferences.

Many extinct turtles took on interesting forms, with some having large feet, others having extensive ornamentation - horns and bumps and nodules - on their heads. Some, like Meiolania, grew to extreme sizes. As the turtle group evolved, many returned to the sea, and became the largest ocean-dwelling turtles of all time - animals like the somewhat well known Archelon. Living turtles come in two main groups: side-necked turtles and hidden-necked turtles. They differ exactly how you'd expect - side neck turtles will retract their heads via the side of the body, curling it around the circumference, while hidden-necked turtles curl their neck into the body, pulling the head directly back into the shell. Most turtles - and all tortoises - fall into the hidden-necked group, including sea turtles! Turtles vary in size, limb length, head shape, and tail length, and live on every continent in the world today. In general, turtles are omnivorous, though many species show preferences for plants or meat.

ARCHOSAUROMORPHA

We now dive into the rest of this side of the reptile family tree, everything closer to crocodilians and birds than they are to turtles - the Archosauromorphs. During the Triassic, this group took on many different and weird forms, making the entire group one of the most diverse groups of reptiles in terms of species count and differences in shape. All of these animals have a few things in common in their skeleton, though modern archosaur features took a while to evolve. Animals such as Sharovipteryx, the long-tailed reptile that used its legs for gliding membranes, the end-Permian survivor Protorosaurus, the *ridiculously* long-necked Tanystropheus, and aquatic Dinocephalosaurus were all early branching members of this group. But as we get closer to Archosaurs proper, we see more and more weirdness.

Allokotosaurs

Allokotosaurs were weird large herbivores, with sprawling limbs and long tails, as well as short necks and boxy heads. They lived throughout the Triassic and were just bizarre. Some species even had horny beaks in the front of their jaws to help clip off plant material. One species, Teraterpeton, had a long, downward-pointing mouth. Other species had long, thin necks to reach higher vegetation. And, to just round out the craziness that is this group, Shringasaurus falls in here - a weird reptile with a sprawling body, shorter tail, long neck, small head, and horns on its head. Just for funsies. These herbivorous behemoths were some of the most unique animals of the Triassic Period.

Rhynchosaurs

During the Triassic, there was a group of small, quadrupedal Archosauromorphs that really showcase the fun of convergent evolution. See, these little animals? Were Archosauromorphs doing their best to be rodents, long before rodents would ever appear. These little herbivores had short tails, stout bodies, short limbs, and front teeth that grew long for gnawing on plants - much like living rodents. Some got as long as two meters, and these were a fixture of much of the Triassic, before going extinct during the end-Triassic extinction.

Proterosuchids

Proterosuchids were a group of Archosauriformes - so still Archosauromorphs, but now getting closer to proper Archosaurs - that were a group of predators that really capitalized on the whole End Permian Mass Extinction thing. Found only in the latest Permian and earliest Triassic, these were medium sized reptiles with long tails and stout bodies. Their heads were long and narrow, with a hooked upper jaw interlocking with the lower jaw. They looked superficially like crocodilians, but lacked the scutes that are found in said group.

Erythrosuchids

The next group to branch off, the Triassic Erythrosuchids were the apex predators of the Early and Middle Triassic, before Pseudosuchians really took over later on. They were extremely large, reaching between 2.5 and 5 meters long, with huge heads and robust bodies. When I say huge heads, I *mean* huge heads - they were robust and deep, and the upper jaw has a distinct dip that goes down lower than the lower jaw, giving their heads a very characteristic shape. They also are some of the first animals to have the Archosaur Hip Shape, so they only had a semi-sprawling posture - their limbs were more nimble!

Euparkeria

Many people have heard of Euparkeria. They even think it's a dinosaur ancestor. Well, it's not, not really. Euparkeria goes around here in the Archosaur tree, closer to living Archosaurs than the Erythrosuchids but not as close as the next group. In truth, Euparkeria is very similar to what we'd expect the common ancestor of both crocodilians and dinosaurs to be like, with fairly upright limbs - though recent studies indicate it was only quadrupedal, not capable of bipedalism. It had a long, rectangular skull, similar to early members of proper Archosauria, and osteoderms (scutes) on its back. This little guy from the Early Triassic gives us a hint as to how Archosaurs came about, with the specialized ankles we'd see in the Archosaur group first showing up in Euparkeria.

Proterochampsia

The closest group to living Archosaurs, Proterochampsians were weirdly crocodilian like, to the point of often being found to be in the crocodile line of Archosaurs! These were Triassic reptiles shaped very much like living crocodilians, with long wide bodies and tails, and very long triangular skulls. They had sprawling limbs, and scutes along their backs and bodies. The heavy osteoderms are well documented in a fully aquatic member, Vancleavea. In fact, on that side of the group, the animals had less of a crocodilian like head and more of small, tempered heads, possibly due to different lifestyles.

Phytosaurs

Okay, these guys are either actually in the crocodilian line or just outside of Archosauria, it's a huge question. They were also weirdly crocodile like reptiles that lived during the Triassic, but were distinct from the Proterochampsians. Some had long snouts with conical teeth to eat fish, but others had shorter snouts with differently shaped teeth for eating land animals. They had distinctly serrated teeth, unlike living crocodilians, and didn't have erect or even semi erect gaits like living Archosaurs. Though many specialized for life in the water, this was a very diverse group that was doing a lot of the crocodilian-type jobs of later periods, but weren't crocodilians. They didn't have the secondary palate bone that allows crocodilians to breathe when their mouths are full of water! Weirdly, they were way more heavily armored than crocodilians, with heavy bony scutes and dense abdominal ribs (gastralia) for protection. Finally, they had their nostrils near their eyes, rather than at the end of the snout - allowing for them to breathe while submerged without that secondary bony palate.

ARCHOSAURIA

This is the group of the most recent common ancestor of living crocodilians and birds, and all of that ancestor's descendants. So while everything from Archosauromorpha to this have been closer to Archosaurs to anything else, these are the proper Ruling Reptiles as we currently define them. Archosaurs have teeth set in deep sockets, extra openings in the skull, and a pronounced ridge on their femur. They also only have claws on their first three fingers of the hand - the fourth and fifth, if they have them, lack claws. Archosaurs immediately branched into two groups: Crocodilians and their relatives, versus Birds and their relatives. We will start with the Crocodilians.

Pseudosuchia

A lot of early crocodilian relatives were superficially similar to living members, so they were originally given the name "fake crocodiles" or Pseudosuchia. Then, it turns out, that group was just the ancestors of crocodilians - which underwent many different shifts and turns in their evolution - so that means real crocs are... fake crocs. Remember friends, the names we give these things? Are extremely arbitrary. Do not take them for indicators of what these things are like. Early members had very broad, bulky skulls and even somewhat upright gaits, allowing for active predatory lifestyles. Everything from here until Avemetatarsalia are all Psuedosuchians.

Aetosauriformes

In the Late Triassic, there weren't any armored dinosaurs, but there were Aetosaurs! These animals had extreme armor all over their bodies, with overlapping scutes on their back and often spikes or other armor on their limbs and back. They also had small, triangular heads, built for feasting on a variety of plants! These were extremely common animals, often having weirdly pig-like snouts if you squint, and mostly sprawling limbs. Found worldwide, their armor would have allowed them to be protected from the many varieties of large predator reptile around them, though they still ultimately went extinct during the end-Triassic extinction.

Poposauroids

A group that used to include other animals, this weird hodgepodge of a variety of Triassic Pseudosuchians including sail-backed animals, toothless creatures with beaks, and animals weirdly similar to dinosaurs to the point of being confused with them in the past. All of these crazies had upright limbs, and in the Shuvosaurids, this lead to animals evolving into essentially scaly lithe bipeds, what we used to think dinosaurs looked like! In fact, Effigia and Shuvosaurus both had long necks, beaks in the front of their small mouths, and completely upright postures, making them just straight up look like scaly versions of their dinosaur neighbors like Coelophysis. Alas, the Poposauroids, like many groups, went extinct in the end-Triassic extinction.

Rauisuchians

The top predators of the late Triassic, these were very large terrestrial pseudosuchians, with large boxy heads and upright limbs. This allowed them to move quickly and attack prey efficiently, making them extremely well adapted hypercarnivores. In a lot of ways, Postosuchus and its relatives in this group were convergent with later theropod predatory dinosaurs - even having huge boxy heads like Tyrannosaurs would. This means that what dinosaurs one day perfected, crocodile relatives tried out first! Alas, like most apex predators, they were not immune to mass extinctions, going extinct during the end-Triassic.

Crocodylomorpha

Now, at this point, the line that would lead to living crocodilians - Crocodylomorpha - actually look less like living crocs than the Rauisuchians and Phytosaurs did at the same time! These little reptiles were quadrupedal, thin, and built for running fast - they were lithe creatures built to avoid all of those big scary animals around them. But these were the only Pseudosuchians to survive the end-Triassic! And the first group to branch off here?

Thalattosuchians

During the Jurassic and earliest Cretaceous, a common feature in the oceans were marine crocs - the Thalattosuchians! Still fairly distantly related to modern crocodilians, these reptiles convergently evolved many of the same adaptations for ocean dwelling as the Sauropterygians we met earlier. Some members, like Metriorhynchus, even evolved flippers and a tail fin! They had elongate bodies and very long, thin skulls for catching fish and other animals. They also gave live birth - possibly the only Archosaurs to ever do so!

Many more croc relatives would evolve into a variety of active terrestrial predatory niches, so we're going to jump down to the next major group:

Ziphosuchians

Ziphosuchians were a group of croc relatives that actually lived from the Jurassic until the Miocene, as recently as 11 million years ago. These animals were ridiculously diverse in both diet and lifestyle, with a wide variety of shapes and sizes. Some, like Kaprosuchus, straddled the line between aquatic and terrestrial predation; others, like Sebecus, were completely terrestrial and huge predators during the Cenozoic; others had weirdly diverse teeth and thus potentially unique diets; and still others just straight up evolved to eat plants or to be omnivores, even shortening and squishing their skulls to be dubbed by modern researchers as "Pug Crocs". This huge diversity of form and ecology makes Ziphosuchians an intriguing extinct group, one that will benefit from increased research in the future. Some were even built for running around, and others had duck like snouts! This was a very diverse group I recommend learning more about.

Neosuchia

The rest of Pseudosuchia - Neosuchia - are all living crocs and their closest relatives, closer than those Ziphosuchians. Many were very similar to living crocodilians, even filling similar niches, though evolving to do so independently. Some had huge, long jaws, potentially to hold onto a throat pouch for catching large prey during the Cretaceous. Some were slender, marine reptiles, evolving to be aquatic again! The Dyrosaurids were a group of global marine, long-jawed crocs that survived the end-Cretaceous extinction and were some of the only predators in the post-extinction seas other than sharks. They had teeth in deep pits, distinct from other croc relatives. While they never developed flippers like Thalattosuchians, they did adapt their limbs for more efficient marine locomotion.

Crocodylians

Living Crocodylians, a group of Neosuchians, only first appeared at the end of the Cretaceous, and were not the only surviving Pseudosuchians until relatively recently - many other forms, like the Ziphosuchians and Dyrosaurids, lasted until late in the Neogene, within the last 20 million years. Crocodylians have semi-sprawling limbs, lots of scutes all of their bodies, and even hearts like birds, pointing to their close relationship. They are semiaquatic animals, spending time both on land and in the water, and have their nostrils on the ends of their jaws. They have a sturdy second palate that allows them to hold water in their jaws and breathe at the same time! They also have some of the most powerful bite forces of any animal ever. Some extinct forms even did more terrestrial predation. Living species come in two groups - the Alligatorids, which have both caiman and alligators; and Longirostres, which have proper crocodiles and gharials. While most of them look very similar, Gharials have very long narrow snouts, while crocs caimans and alligators all have broader snouts.

That concludes the Pseudosuchia. Now we go back to the base of Archosauria, and look at the other half of their family - the bird line archosaurs!

Avemetatarsalia

All animals closer to birds than to crocodilians fall into this group. But that doesn't mean they were all shaped like living birds, just like so many Pseudosuchians looked very different from living crocodilians! They were originally characterized by having bird like ankles, though now the earliest members of the group lack them. At some point early on, members of this group evolved both warm-blooded metabolism and feathers, and we're not sure where. The earliest members of the group, Aphanosaurs, were semi sprawling long-bodied reptiles, fairly nondescript in appearance. That said, long was just their thing - their vertebrae are weirdly stretched out!

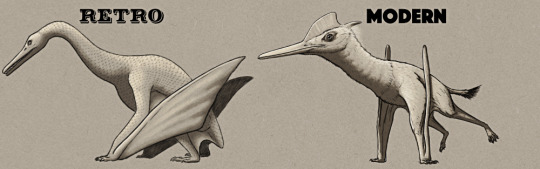

Pterosaurs

Also commonly called "pterodactyls" even though that's... wrong; this is the classical group known as Flying Reptiles, and the next group to branch from the Avemetatarsalia tree! Evolving from thin, lithe, agile floofins - things like Scleromochlus and Lagerpetids - these animals extended their fourth finger extremely long, attaching a membrane of skin and muscle to that dramatically lengthened finger and down to the ankles. Early forms had long tails, with later forms shortening the tails to smaller nubbins. These were the FIRST vertebrates to evolve powered flight. Early forms were fairly generic, but over time they diversified extensively - having diamond tail ends, interlocking long thin teeth in their jaws for catching fish; others grew bristle like teeth for filter feeding small invertebrates; some grew huge bodies, with crests and display structures on their heads like Pteranodon. The Azhdarchids, huge forms that had long necks and giant heads, were some of the most successful members of this group, becoming apex predators in many ecosystems - and no wonder, given they were the largest flying animals ever and stood as tall as giraffes. In general, pterosaurs walked on four limbs, folding up their wings at their sides in order to do so. They first appeared in the Triassic, and, alas, went extinct during the end-Cretaceous extinction. This group is so diverse and fascinating that I could go on forever, so I will leave it here - but feel free to dive into their extensive wikipedia pages!

DINOSAURS

We now move on to Dinosaurs and their closest relatives, the rest of the Avemetatarsalians. We define Dinosauria as the group composed of the two branches of the family - Ornithischians and Saurischians - usually phrased as the Most Recent Common Ancestor of Megalosaurus (a Saurischian) and Iguanodon (an Ornithischian) and all of that ancestor's descendants. Everything from here until the end of our trip through Archosaurs is a dinosaur - including every. single. bird. However, *nothing* outside of these paragraphs are dinosaurs! Dinosaurs are a single group of extremely successful reptiles, unique from all these other reptile groups - and all these other reptile groups are unique from dinosaurs. The main feature dinosaurs have in common? A completely open hip socket, allowing for limbs to be placed directly underneath the body, making dinosaurs very different in locomotion and posture than living nonavian reptiles, and very similar to their living members the birds. Early relatives showcase this evolution from semi-sprawling archosaurs to fully upright dinosaurs. Dinosaurs first appeared in the middle Triassic, though they weren't common until the Late. All the early forms were pretty much the same - small, bipedal animals, with long necks and tails, and fluffy bodies.

Ornithischians

The first main group of dinosaurs are the Ornithischians, which are united in having a small beak in the front of the jaws, called a predentary. It is possible that Silesaurids, once thought to be early Dinosaur relatives - quadrupedal lanky herbivores from the Triassic - fall in this group. All Ornithischians were primarily herbivores. Most of them were small, bipedal herbivores, but four main groups showed up over time: Stegosaurs, Ankylosaurs, Marginocephalians, and Ornithopods. Among the miscellaneous dinosaurs outside of those four groups, however, were interesting weirdos - the toothy and small Heterodontosaurs; the burrowing and armored Thescelosaurs; and, of course, the fluffy Kulindadromeus.

Stegosaurs

Stegosaurs were huge, quadrupedal herbivores with plates and spikes on their backs, necks, and tails. The plates were primarily for display and communication, while the spikes were for both display and self defense. They had very small heads, too, giving them a weird appearance. Alas, Stegosaurs lived mainly in the Jurassic, going extinct in the early Cretaceous... probably. Jury's still out based on some fragmentary fossils and tracks.

Ankylosaurs

Ankylosaurs, cousins of Stegosaurs, lived through to the end of the Cretaceous. They were heavily armored dinosaurs, with non-overlapping osteoderm scutes all over their backs and necks and heads. Many had spikes on the sides of their bodies, while other forms grew strengthened tails with clubs at the end for fighting each other. Still others grew weird sharp tail ends, formed from scutes creating a flat surface at the end of a stubby tail. They were not just like turtles, with the scutes evolving from scales rather than a shell evolving from the ribs. In fact, often times the scutes formed distinct rows along the body, not even really touching. There were tons of these dinosaurs throughout the Jurassic and Cretaceous, only going extinct in the end-Cretaceous extinction.

Marginocephalians

Marginocephalians included both Pachycephalosaurs - the dome-headed dinosaurs - and Ceratopsians, the horned and frilled dinosaurs. Pachycephalosaurs were bipedal animals, with huge domed heads and extremely strengthened tails - allowing them to butt heads and fight each other much like rams today. Ceratopsians had frills on the back of their heads - though in early forms it was very small, like Psittacosaurus - that evolved into large crests for display. Many grew horns on the side of these crests, while others grew huge horns on their faces in a variety of patterns. These horns were great for defense, but primarily served for communication and display, because some - like the curved downward horn of Einiosaurus - weren't really built for defense. Pachycephalosaurs were rare, but Ceratopsians were some of the most common dinosaurs around the world, with both groups only going extinct in the end-Cretaceous extinction.

Ornithopods

Finally, Ornithopods! Ornithopods were cousins of Marginocephalians, much as Ankylosaurs and Stegosaurs were more closely related to each other earlier. Some forms from the southern hemisphere (known as Elasmarians) were weirdly diverse, with lots of different forms from stocky and armored to small and lithe. Rhabdodonts had ridiculously complex teeth for efficient foraging, with some forms being more quadrupedal and others more bipedal. Some of the Ornithopods, Dryosaurids, evolved into extremely fast reptiles, adapted for running quickly away from predators with elongate, lean bodies. The second dinosaur ever described, Iguanodon, is from the Ornithopod group, with huge spike claws on their thumbs. Others, like Ouranosaurus, grew huge sails on their backs. While in the Jurassic and Early Cretaceous these animals were well adapted for feeding on dry hard plants, as the world grew more wet in the Late Cretaceous, they adapted to be able to chew on soft mushy plants. This huge group of Ornithopods - the Hadrosaurs- were extremely social animals, living in large herds with complex nesting sites. Some forms even grew huge crests on their heads, connected to their nostrils and lungs - allowing them to blow air through the crests, creating different sounds like brass instruments! What's really weird is that to chew that soft plant material, they grew thousands and thousands of teeth, which formed a single serrated surface for chewing. They also had weirdly long heads, superficially similar to horses; and hooves on their front feet! These diverse dinosaurs also only went extinct due to the end-Cretaceous extinction.

Saurischians

The other branch of the dinosaur family tree were the Saurischians - animals with hollow bones and lungs much like living birds, and it is from this group that birds would evolve. They come in two main flavors: Sauropodomorphs, and Theropods.

Sauropodomorphs

This is where all of the "long-necked" dinosaurs go, as well as their early relatives. In the Triassic, most of these animals were "prosauropods" - an artificial group of dinosaurs that were very successful, and from which proper Sauropods would evolve. Originally small bipedal omnivores, over time Sauropodomorphs grew longer necks, quadrupedal stances, and bulky bodies. The earliest Sauropods appeared in the Triassic, with four pillar like legs and huge torsos. Over time, a variety of different Sauropod groups would evolve. The Mamenchisaurs of Asia had the longest necks of any animal ever - reaching enormous sizes. The stocky Turiasaurs of Europe, North America, and Africa had short stocky necks and sturdy bodies. Diplodocoids included classic dinosaurs such as Apatosaurus/Brontosaurus and Diplodocus, but also weird squished forms like Brachytrachelopan, sailed ones like Rebbachisaurus, super grazers like Nigersaurus, and the weird spine-neck having Bajadasaurus. However, most sauropods fall into the group Macronaria. These were bulky dinosaurs, but evolved into some of the tallest animals ever in Brachiosaurus and Sauroposeidon. And, from this group evolved the Titanosaurs: The Largest Land Animals Ever. These were the dominant sauropods for the Cretaceous period, and were found on every continent around the world. Some grew to enormous sizes, while others were smaller; some grew armor on their backs, while others weirdly curled their tails into a spiral. Some had humps on their backs, others lost all their toe claws for maximum front limb pillar supportive action. While all other Sauropod groups had gone extinct by this point, Titanosaurs were extremely diverse and common right until the end-Cretaceous extinction.

Theropods

All remaining dinosaurs fall into this group, the Theropods. These were all bipedal animals, and where feathers were regularly retained (other dinosaur groups usually lost their feathers as they grew bigger). Early members, like Coelophysis, had long thin necks and small heads, and were efficient fast predators in the Triassic - though not the dominant ones by any means (that went to the Pseudosuchians). Over time they grew bulkier and more powerful, with display crests on their heads like in Dilophosaurus (note: it did not have a neck frill, it did not spit poison).

Ceratosaurs

The first big grouping of Theropods to diverge were the Ceratosaurs, which were bulky predators with huge skulls and progressively smaller arms. Many had horns on their heads and armor on their bodies. Some forms remained small and thin, like Masiakasaurus, and even evolved herbivory, like Limusaurus. Others, the Abelisaurs, evolved very long thick bodies - sosig/sausage bodies - and teeny tiny arms for display purposes. They primarily caught and ate other animals with their huge, sturdy, square shaped jaws.

Megalosaurs & Allosauroids

On the line leading to birds, many different types of large predators evolved. Megalosaurs - of which the first named dinosaur, Megalosaurus, is a member - were lean predators with long arms and long heads, found across Europe and North America. One group, the Spinosaurids, evolved to be huge heron like predators, living at or near the water and scooping up fish and other animals - even creating pouches in their mouths to do so. Some evolved huge sails on their backs, presumably for display. Efficient, flexible jawed hypercarnivores - the Allosauroids - appeared in the Jurassic and were some of the largest predatory dinosaurs to ever live, lasting until the mid Cretaceous.

Coelurosaurs

Coelurosaurs contains all the rest of the Theropods, and these were very birdlike animals with more complex feathers and brains more similar to birds. Here we had Megaraptors, huge predators with giant hand claws. They were also very unique in another way. Outside of mammals, terapods are not able to turn their wrists inward, ie, form "bunny hands", rendering the "T. rex" pose that many people do to mimic dinosaurs extremely inaccurate, and all the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park et al have very broken wrists. However, Megaraptors? Could turn their wrists inward. So, I guess everyone was just mimicking Australovenator this whole time, or something.

Tyrannosaurs

Tyrannosaurs were a huge group of Coelurosaurs with a variety of different members - some were small fast bipeds covered in floof with display crests on their heads; while others were bulky predators evolving bigger and bigger heads. The bulkiest known land predator, Tyrannosaurus, was one of the last members of this group. Tyrannosaurs evolved shorter and shorter arms in order to grow stronger, bigger heads - and were some of the most highly adapted carnivores in history. They lived throughout the Northern Hemisphere, and only went extinct thanks to the end-Cretaceous extinction.

Maniraptoriformes

Many different types of small, bipedal floofins evolved in Coelurosaurs - things like Compsognathus, Sinosauropteryx, and Ornitholestes. These animals progressively evolved more feathers on their arms, until finally in Maniraptoriformes we see the appearance of bird-like wings. The "Ostrich Mimics" - even though they came first - Ornithomimosaurs were dinosaurs that essentially looked like modern ostriches but with long, bony tails. These fluffy dinosaurs had simple wings on their arms for display. Some members grew huge and weird - Deinocheirus, the Demon Duck, was a huge herbivore with giant arms and a hump on its back. Evolution is amazing like that. The Alvarezsaurs remained small, and their front limbs shortened until they had a single claw on each wing - allowing them to dig up bugs and other animals from hard to reach places. Therzinosaurs grew to be upright in posture, with huge hand claws and pot bellies, allowing them to digest huge quantities of plants.

Oviraptorosaurs

The Chickenparrots - Oviraptorosaurs - were herbivorous dinosaurs with near-modern wings. They had shortened tails, and long necks, and squat bodies. They lived throughout the Cretaceous and were extremely common. Some members had huge crests on their heads; most of the later members had huge, parrot-like beaks as well. Honestly, Oviraptorosaurs were very weird and charismatic dinosaurs, and mainly ate an omnivorous to herbivorous diet.

Scansoriopterygids

At this point, one of the weirdest dinosaur groups - the Scansoriopterygids - diverged. They didn't live for very long, only found in the Jurassic of China; but they evolved membraneous wings between their fingers, making them - essentially - actual (small) wyverns.

Dromaeosaurs

Dromaeosaurs - "raptor" dinosaurs - are where we see the first signs of flight in dinosaurs, with Microraptor having wings on its arms and legs allowing for a clumsy version of flight. Most members couldn't fly, but they came in a lot of weird shapes and sizes - with some even being semi aquatic and shaped like geese! They had sickle claws on their feet, which were good for stabbing strategically at certain places in their prey, leading to the prey bleeding out. They would hold their prey steady by rapidly flapping their wings, which they could also do to move quickly up steep surfaces. These predators ranged in size from very small to bear sized, though Velociraptor - the most famous one - was only the size of a coyote. All of them - ALL of them - were feathered like living birds.

Troodontids and early Avialae

Their cousins, the Troodontids - which may or may not be closer to birds, we don't know - were also very bird like, but more slender in proportion and with smaller sickle claws. Interestingly, they had some of the largest brains for their bodies among Mesozoic ("nonavian") dinosaurs. Other forms similar to them - may or may not be in a group with them - called Anchisaurids, still retained the leg wings of Microraptor and co. Many of these animals have been preserved with complex, fluffy feathers, similar to living birds. Still similar yet, Archaeopteryx didn't have four wings, but did have fluffy legs and sickle claws on its feet similar to Troodontids and Anchisaurids. One dinosaur, Jeholornis, evolved to eat seeds; while another, Sapeornis, was one of the first dinosaurs to try out a lifestyle similar to living birds of prey.

Enantiornithines

At this point, dinosaurs lost their bony tails and grew shortened, fused tails - the tails of modern birds. They tried out lots of different forms with this - dinosaurs with ribbon tail feathers like Confuciusornis, and then the Opposite Birds, or Enantiornithines. See, living birds have a concave joint location on the coracoid (shoulder bone) and a convex joint on the scapula to link to it; in Enantiornithines, the concave joint is the scapula, and the convex is the coracoid. Enantiornithines were extremely common, with countless forms across the Cretaceous period - some were waders, others were like birds of prey, some even adapted to look like toucans with teeth. Still, all of them went extinct at the end of the Cretaceous.

Euornithes

The line to true birds, with the correct wing articulation, wasn't quite as diverse, but had many members. Many of these animals were adapted for water based life, while others evolved to be large flightless animals. Others were simple tree dwelling birds, living alongside the similar looking Enantiornithines. The closer you get to living birds, the more teeth were lost - and the modern bird beak began to evolve. Still, teeth are found in the closest relatives to modern birds, Ichthyornis and the Hesperornithes. Hesperornithes were a group of Cretaceous dinosaurs that evolved for aquatic life, spending all their time in the water hunting fish - kind of looking like a toothy penguin or loon.

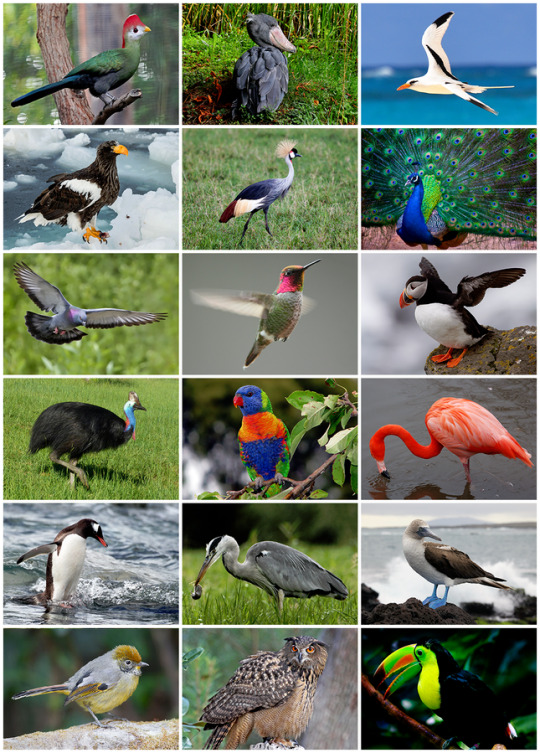

NEORNITHES

All remaining dinosaurs fall into Neornithes, the least inclusive group that still has all living birds, a derived clade of the Theropods. These were the only dinosaurs to survive the end-Cretaceous extinction. You can literally divide dinosaurs based on that extinction - everyting above this, from the Mesozoic; everything below this, from the Cenozoic. Today, half of all reptiles - over 10,000 species, possibly up to 20,000 - are birds. There is no way for me to go over all birds without losing my mind, so I'm going to summarize them as simply as I can. But these dinosaurs are, as you can see, firmly nested in the dinosaur family tree - there is no way to separate them out. What follows is the world's most efficient description of bird diversity ever.

Palaeognaths

The first major division is between Palaeognaths and Neognaths. Palaeognaths include ratites like Ostriches, Cassowaries, and Emu, but also the flighted Tinamou. It seems that this group evolved flightlessness multiple times, and did not all stem from a flighted ancestor - an extinct group, the Lithornithids, were fully flighted, tree dwelling dinosaurs of the Paleocene and Eocene (right after the end-Cretaceous extinction). Neognaths contains all other birds.

Galloanserans

Neognaths contains Fowl - chickens, ducks, and relatives - and all other birds. The fowl group, Galloanserae, has some of the only Neornithines we have fossils of from the Cretaceous. These animals come in a wide variety of forms - including the extinct, large, flightless Gastornis and Mihirungs. Ducks, Geese, Swans, Screamers, and Magpie-Geese all fall into the Waterfowl side of Galloanserae; while Chickens, Pheasants, Megapodes, Partridges, Grouse, Curassow, Guineafowl, Quail, Guans, and Chachalacas are on the Landfowl side.

One group of birds, the extinct pseudotoothed Pelagornithids, resist classification - it's unclear where they go, but they might actually be closely related to the fowl. These were some of the largest flying birds ever, and had eldritch horror mouths. Birds can't reevolve teeth - they lost the genes for enamel - so instead, some make their tongues sharp, while Pelagornithids just decided to eff up their jaws.

Neoaves

Now, the rest of birds are in Neoaves, which seems to have arisen at the very end of the Cretaceous and diversified extremely rapidly at the start of the Paleocene. This means their evolutionary relationships are a MESS and we don't really know what goes where between here and Telluraves. Different groups of these miscellaneous Neoavians include Mirandornithes (flamingos, grebes, and the extinct giant swimming flamingos), Columbimorphs (pigeons, mesites, and sandgrouse), Otidimorphs (bustards, cuckoos, and maybe turacos), Strisores (hummingbirds, swifts, potoo, frogmouth, nightbirds - the flying specialist clade), Gruiformes (cranes and rails), Charadriiformes (waders, gulls, and auks), Eurypygimorphs (Sunbittern, Kagu, and Tropicbirds), and Aequornithes (water birds). Aequornithes is an extremely diverse group, including loons, penguins, albatross, petrels, storks, boobies, cormorants, herons, ibises, shoebill, hamerkop, and pelicans - as well as an extinct group, the Plotopterids, which were boobies doing their best penguin impression! There's also the Hoatzin, which is a mysterious bird among these mysteriously related birds, that doesn't really go with anything - but man, does it smell.

Telluraves

The rest of birds fall into Telluraves, known as the tree dwelling birds, which evolved from a predatory common ancestor. These include the Accipitrimorphs, which fall into Cathartiformes - Western Hemisphere Vultures, including the Teratorns that went extinct recently - and Accipitriformes, which includes all hawks, eagles, buzzards, Eastern Hemisphere vultures, the Secretarybird, kites, and other diurnal birds of prey that aren't falcons or seriemas. Owls, aka nocturnal birds of prey, form another group in this clade, with many weird extinct forms - including the stilt-owls. Coraciimorphs are a major group of Telluraves, which includes mouse birds, cuckoo roller, trogons, quetzals, hornbills, kingfishers, hoopoe, and woodpeckers - this extremely diverse group of tree dwellers is found worldwide and includes so many weird animals (have y'all seen how the tongue works in woodpeckers? Yeah).

Australaves

Australaves is the last remaining clade, still within Telluraves, and its a group of birds that arose in Australasia. The first group to diverge were the Seriemas and their relatives, which includes all the Terror Birds - one of the most successful predator bird lineages ever, with tons of species that carried on the theropod legacy excellently in South America and then North America, only going extinct due to the ice age. Next to diverge are the falcons and caracacaras, which are very different and separated from the other diurnal birds of prey we discussed above - and also, very cute. Next up? Parrots! Finally! Parrots includes everything from the Kakapo to the Macaw, and had a lot of huge varieties over their evolution.

Passeriformes

Sister to Parrots, our last bird group, within Australaves, and including HALF of all bird species, are the Passerines - Perching Birds. Literally, there are more species of Passerines - just one group of birds - than there are of all mammals. I'm going to list them now as simply as I can, but just know, there are so many of these, and they are very diverse and very colorful and very weird and they include the second smartest animal on earth after people, the members of the genus Corvus. So, Perching Birds include New Zealand Wrens, Asities, Broadbills, Sapayoa, Pittas, Crescentchests, Gnateaters and Gnatpittas, Antbirds, Antpittas, Tapaculos, Antthrushes, Ovenbirds, Woodcreepers, Manakins, Cotingas (including the Cock of the Rock), Tityras, Tyrant Flycatchers, Scrub-Birds, Lyrebirds, Australian treecreepers, Bowerbirds, Fairywrens, Emu-wrens, Grasswrens, Bristlebirds, Pardalotes, Scrubwrens, Thornbills, Gerygones, Honeyeaters, Pseudo-babblers, Logrunners, Jewel-Babblers, Quail-Thrushes, Cuckooshrikes, Trillers, Whiteheads, Sittellas, Whipbirds, Wattled Ploughbill, Shirketits, Australo-Papuan Bellbirds, Painted Berrypeckers, Vireos, Whistlers, Oriols, Figbirds, Boatbills, Woodswallows, Butcherbirds, Currawongs, Australian Magpie, Berryhunters, Shrikes, Boubous, Tchagras, Bristleheads, Ioras, Wattle-eyes, Batises, Vangas, Fantails, Drongos, Flycatchers, Ifrits, Birds of Paradise, Choughs, Apostlebirds, Melampittas, Jayshrikes, Crows, Ravens, Jays, Satinbirds, Berrypeckers, New Zealand Wattlebirds, Longbills, Stitchbirds, Australian Robins, Rail Babblers, Rockfowl, Rock jumpers, Hyliotas, Fairy Flycatchers, Tits, chickadees, Titmice, Reedlings, Larks, Nicators, Warblers, Crombecs, Cisticolas, Reed Warblers, Grassbirds, Donacobius, Malagasy Warblers, Wren-Babblers, Swallows, Martins, Bulbuls, Babblers, Parrotbills, White-eyes, Laughinthrushes, Fulvettas, Leaf-warblers, Hylias, Bushtits, Scrub Warblers, Bush Warblers, Yellow FLycatchers, Palmchats, Waxwings, Silky Flycatchers, Hylocitrea, Hypocolius, Hawaiian Honeyeaters, Elachura, Dippers, Chats, Thrushes, Oxpeckers, Starlings, Rhabdorns, Mockingbirds, Thrashers, Goldcrests, Kinglets, Wallcreeper, Nuthatches, Treecreepers, Gnatcatchers, Wrens, Sugarbirds, Dapple-Throat, Sunbirds, Flowerpeckers, Leafbirds, Fairy-Bluebirds, Olive Warbler, Przewalski's Finch, Weavers, Indigobirds, Whydahs, Waxbills, Munias, Accentors, Sparrows, Snowfinches, Wagtails, Pipits, Finches, Euphonias, Thrush-Tanagers, Longspurs, Buntings, Cardinals, Mitrospingid Tanagers, regular Tanagers, Yellow Breasted Chat, Grackles, Blackbirds, Orioles, Wrentthrush, a bunch of weird warblers, spindalises, and Hispaniolan Tanagers.

Why the fuck are passerines so diverse, you ask? Apparently their genetic makeup leads to speciation at the drop of a hat. It's wild.

And that, my friends, is all dinosaurs. Everything from the Dinosaur header to now.

Let's go back to the base of Sauria! Take it back now y'all!

LEPIDOSAUROMORPHA

Finally, the other half of the Saurian tree! Lepidosauromorphs, unlike Archosaurs, kept a fully sprawling gait, but had a sliding joint in the shoulder blade chest area to allow for longer strides while moving, and pleurodont teeth - teeth fused to the inner surface of the jaw bone. They also retain the Parietal Eye - a small "third eye" on the top of the head found in earlier reptiles and amphibians - which is not found in Archosaurs or Turtles. Thus, these are extremely unique reptiles - though they superficially look similar to many of the reptile groups we've covered, they have adaptations for more efficient feeding and locomotion. In addition, many Lepidosaurs - including Tuatara and many forms of lizard - have tail autonomy, meaning, they can shed their tail and regrow it in order to elude predators, a feature not found in Archosaurs. This group is the group of Lizards, Snakes, and Tuatara, and all of their extinct relatives - things closer to them than to the Archosaur side of the tree.

Kuehneosaurids

Unlike Archosaurs, Lepidosaurs don't have a lot of varied and diverse extinct relatives - while Archosauromorpha is filled to the brim with weirdos, Lepidosauromorphs only have a few isolated forms showing the evolution to Lepidosaurs, and possibly the Kuehneosaurids. Kuehneosaurids were another experiment in reptilian gliding via rib extinctions, living entirely in the Triassic and completley separate from the Weigeltisaurids from earlier. They were insectivores, with pin like teeth, and very small heads. Some members were capable of gliding, while others were only really good at leaping from branch to branch.

Crown Lepidosaurs are made up of two groups: Rhynchocephalians (Tuatara) and Squamates (lizards and snakes).

Rhynchocephalia

Today, there is only one: the Tuatara. In the past, they were everywhere, extremely common reptiles found around the world, especially in the Triassic and Jurassic. Compeletely separate from lizards, these reptiles had fused skull bones into a bar across the top of each side of the head, and unique teeth for digesting a wide variety of food. While the only living member looks superficially like lizards, extinct species took many forms - including one that had very small legs and a very elongate body for simming through the water (Pleurosaurus). Sapheosaurids had huge broad tooth plates, allowing them to eat hard shelled organisms. Today, the living Tuatara doesn't replace its teeth during its life, leading to a changing diet from childhoood to adulthood, switching from hard prey to softer prey as they age. Today, they are only found in Aotearoa.

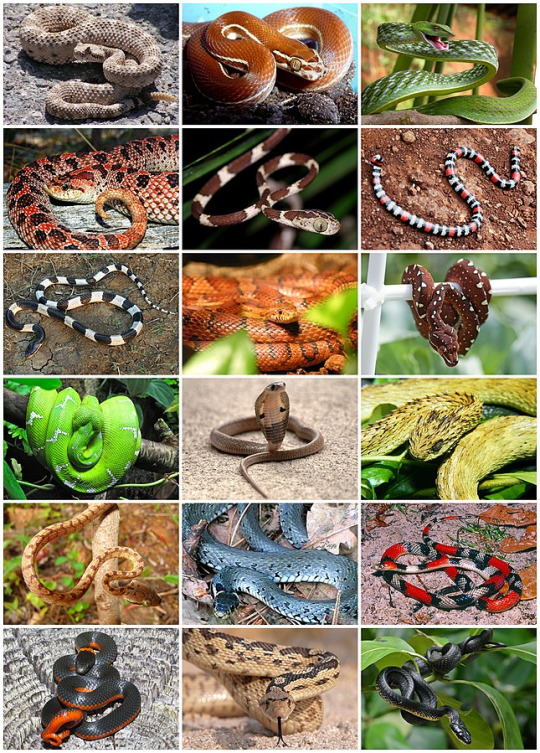

Squamates

All remaining reptiles - including just as many species as birds - are the Squamates, otherwise known as lizards and snakes. Squamates aren't just generic reptiles, but highly specialized animals with very unique adaptations. They have horny scales all over their body that have to be shed via moulting, and are very differently formed than the scales found in Archelosaurs. They have movable bones in the quadrate, allowing the upper jaw to move independently. In addition, viviparity - giving birth to live young rather than eggs - evolved multiple times in Squamates, across a variety of members. And they varied extensively in size, with extremely small members less than an inch long, to huge marine members that are long extinct.

The first group to diverge are the Dibamids, or Blind Skinks, which are small insectivorous lizards that burrow into the soil. They also lack limbs, but will not be the last lizards to lose their limbs.

Gekkotans

Next up are the Gekkos - small, mainly carnivorous lizards found everywhere but Antarctica. They have a variety of clicking and chirping sounds, unique among lizards, and have loud mating calls. They are usually nocturnal, and many have specialized toe pads, allowing them to grab and climb on smooth and vertical surfaces. There are over a thousand species of Gekkos alone.

Scincomorphs

Next are the Skinks and their close relatives, the Scincomorphs. This has a lot of different forms, including many extinct ones. These lizards have cone shaped heads with very large and symmetrical scales, forming kind of a shield over their bodies. These scales are smooth and glossy. They have dermal armor, as well, and long tapering tails. There are over a thousand species, and many are found in the desertws of Australia and temperate areas of North America. Girdled Lizards, Spinytail Lizards, and Night Lizards all fall into this group along with Skinks.

Lacertoidea

Up next are the Lacertoids, a big group of diverse lizards united by having tile-like scales on their bodies, which form characteristic rings in Amphisbaenians. Members include the Amphisbaenians - aka worm lizards, yet another lizard group that lost their legs - as well as the Wall Lizards (Lacertids), Largescale Lizards (Alopoglossids), Spectacled Lizards (Gymnophthalmids), Whiptails, Racerunners, and Tegus (Teiids). This group also has over a thousand species with a variety of ecologies - and some members even are capable of parthenogenesis! Most Lacertoids are small or medium sized, though Tegus get quite big. They are slender lizards, with long tails, and a wide vareity of colors.

Toxicofera

All remaining squamates - literally all - fall into a single group, the Toxicoferans. As the name suggests, these reptiles have in common the presence of venemous members - species that produce venom and are able to deliver it to prey via biting. In fact, venom seems to have only evolved the once in reptiles: in th ancestor of this group, Toxicofera (see why a venomous Dilophosaurus, a dinosaur very far removed from this group, was ridiculous?). Containing half to sixty percent of all Squamates, Toxicoferans are to Squamates as Passerines are to Birds. There's just SO many of them. We used to not know about this group, because they don't have morphological similarities other than the venom - but thanks to genetic studies, we have been able to recover it with genomic phylogenetics. Evolution sure is fun! They first appeared in the Late Triassic, meaning all these other lizard groups diverged rapidly during that period. Toxicoferans have two main groups: Iguanians with Anguimorphs, and Snakes.

Anguimorphs

Anguimorphs include a lot of different varied lizards, such as beaded lizards, Gila Monster, Knob-Scaled Lizards, Galliwasps, American Legless Lizards, Glass Lizards, Alligator Lizards, Crocodile Lizards, and Monitor Lizards. As such, it includes the largest living lizard species, the Komodo Dragon! These reptiles can have limbs or be limbless, can have long tails or short tails, can give birth to live young, feed on insects, be hypercarnivores, be semiaquatic, or even have well developed limbs for climbing. There were also many extinct forms of this group, which were venomous and often very dangerous predators in their Mesozoic environments.

Polyglyphanodontians

A completely extinct group of lizards, these reptiles were relatives of Iguanians and were the dominant type of lizard across North America and Asia during the Cretaceous and earliest Paleogene. Many had large, blunt teeth for crushing food; others were specialized herbivores with iguana like teeth; and yet others had blade like teeth for shearing plants. Most went extinct at the end-Cretaceous, with only one form surviving into the Cenozoic and going extinct in the Eocene.

Iguanians

Iguanians, the remainder of the non-snake lizards, includes two thousand species of Iguanas, Chameleons, Anoles, Phrynosomatids, Agamids, and more - such as Collared Lizards, Leopard Lizards, Helmet Lizards, Curly-Tailed Lizards, Spiny Lizards, Swift Lizards, and Tree Lizards. Most are arboreal, but many are terrestrial. They have non-prehensile tongues, which are extremely unique and modified in Chameleons. Most are found in the Western Hemisphere, though many are found on islands around the world.

Mosasaurs

A group of large marine lizards, closely related to snakes (which we will visit next), these huge predators were a fixture of the Late Cretaceous seas, before going extinct during the end-Cretaceous extinction. These reptiles over time turned their legs into flippers, and developed fins on their tails, completely adapting for aquatic life. They had bodies similar to living monitor lizards, but elongated and streamlined for swimming. They would swim through the water with strong tail propulsions, similar to sharks and ichthyosaurs. They probably would rapidly pounce on prey, swimming extremely fast to catch them by surprise. Many were adapted for eating on shelly hard prey, while others were more adapted for feeding on fish and other vertebrates (such as other marine reptiles). They had double hinged jaws and flexible skulls allowing them to swallow huge prey whole. They gave birth to live young, and had a lot of similar adaptations for marine life to living cetaceans - kind of making them the lizard version of whales, especially given they were warm blooded. They had diamond shaped scales over their body, similar to their living relatives, the snakes.

Ophidians

Snakes and their relatives, Ophidians, are our last group of Squamates. Firmly nested in the group, more closely related to some lizards (Iguanians and Anguimorphs) than to others, this makes snakes - by every definition - a kind of lizard. This bothers a lot of people, but there's no way around it: Snakes are highly adapted lizards. They had many extinct relatives, where all living snakes are in the group Serpentes. Early relatives, such as Lapparentophiids and Simoliophiids, show the evolution of snakes from their lizard ancestors. Some indicators show that snakes may have originally been marine - which explains the whole "Mosasaurs are closest to snakes" thing, at least somewhat. Some early fossils even showcase the reduction of the limbs, which would be lost entirely in proper snakes. However, most researchers think snakes certainly started out as burrowers, with an early relative Najash in the Cretaceous being a terrestrial burrowing animal and the even earlier Tetrapodophis also showing adpatations for burrowing life. Snakes first arose in the Cretaceous, and exploded in diversity during the Cenozoic. The puzzle of snake and mosasaur evolution is one that many scientists are actively working to solve - did snakes start as burrowers, or swimmers?

Madtsoiids

One group of snakes, the Madtsoiids, evolved in the Late Cretaceous and persisted up until the Pleistocene - so very recently - in Australia. Including some of the longest snakes known, they were either just outside the group of living snakes or the first group of them to split out (or maybe they aren't a natural group, but this post is already too long so I'll leave that there). They didn't have the highly mobile jaws of living snakes, so they couldn't swallow large prey, but they did have strong trunks to allow them to squeeze their prey like living boids. If this is a natural group, they only went extinct probably due to the climate change of the Pleistocene, or maybe due to human activity.

Scolecophidians

The nexzt group to diverge are blind and thread snakes, which definitely bolsters the burrowing idea, as many of these snakes have extremely reduced eyes and spend their lives burrowing in the ground. These snakes only use one lung and one oviduct, presumably to make themselves more streamlined and efficient for burrowing life. They do sometimes come up after rain, which is usually the only time you can see them - they do this to escape flooding in their burrows. These are small snakes, found across the world.

Amerophidians

Amerophidians, which is a very small group of unique snakes, includes the American Pipe Snake, Dwarf Boas, and Thunder Snakes. Most members of this group aren't venemous. They have very striking color patterns and are found in South and Central America. Some species are arboreal, while others mainly spend their time burrowing underground. The American Pipe Snake especially eats a very wide variety of other animals, including Caecilians, Amphisbaenids, other snakes, fish, and frogs.

Uropeltoids

This next group of snakes includes shield tailed snakes, earth snakes, pipe and cylinder snakes, and dwarf pipe snakes. These snakes are also burrowers, ranging across South and Southeast Asia. They are nonvenemous, and have distinctive patterns on their bodies. These are some of the most enigmatic snakes, with many poorly understood by researchers. They eat a variety of food, including small invertebrates as well as other snakes and vertebrates.

Pythonoids

Pythons and snakes closer to pythons than to Boas or Caenophidians are what we find in this group, though it's unclear how they're related to those two other groups (the three of them together make up most snakes). Pythons are nonvenomous snakes, suffocating their prey to kill it, and are found across Africa Asia and Australia (with invasive forms in Florida thanks to pet release and one species just native to Mexico). They are ambush predators, hiding to strike prey by surprise. Many forms have very iridescent scales, and some species do burrow and spend most of their time underground before coming up to hunt for frogs and small mammals. They reproduce with eggs.

Booids

Boas, anacondas, tree boas, and their relatives fall into this group, which are extremely common snakes in the Americas and also found in other continents around thew orld. They also, interestingly, have vestigial hindlimbs, that are spurs near the vent region. They, like pythons, kill their prey with Constriction, but can eat prey up to the size of tapirs - even swallowing prey whole, taking weeks to fully digest. They don't crush their prey to death, but rather kill them with suffocation. Unlike pythons, most booids give birth to live young.

Caenophidians

This is our last reptile group, and it includes 80% of all living snake species - basically every snake not previously mentioned. As such, this includes file snakes, racer snakes, odd-scaled snakes, snail-eaters, vipers, water snakes, mudsnakes, cobras, coral snakes, sea snakes, mole snakes, sand snakes, shovel-snouts, burrowing asps, stiletto snakes, hognose snakes, ratsnakes, and so many more. Venemous snakes - like vipers and cobras, including rattlesnakes - are in this group, but not all members are venemous. These snakes are found all around the world, and feed on a wide variety of prey items, including other snakes and lizards.

And those are the reptiles. So many weird extinct forms, so many diverse living ones, the age of reptiles did not end with the Mesozoic - instead, it adapted into the wonderful forms we see today.

I hope you enjoyed this, as long as it was, and thanks for reading!

#reptiles#lizards#dinosaurs#birds#turtles#snakes#crocodilians#tuatara#pterosaurs#plesiosaurs#ichthyosaurs#parareptiles#prehistoric life#repblr#sciblr#palaeoblr#birblr

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

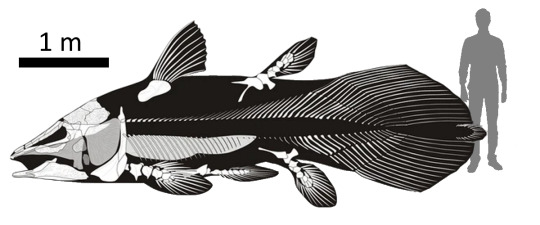

Round 2 - Chordata - Actinistia

(Sources - 1, 2)

The Sarcopterygians (“Lobe-finned Fishes”), are the last of the three groups of “fish”, and are so named for the prominent muscular limb buds (lobes) within their fins. Of the Sarcopterygians living today, they are represented by the coelacanths, lungfish, and tetrapods (including humans), who all diverged in the Silurian. These next fish are closer related to us than they are to Actinopterygiians.

The class Actinistia, the “Coelacanths”, are an ancient group of fish that have been around since the Devonian but today are only represented by two remaining species: The West Indian Ocean Coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) and the Indonesian Coelacanth (Latimeria menadoensis).

Coelacanths can live as deep as 700 m (2,300 ft) below the sea, but are more commonly found at depths of 90 to 200 m (300 to 660 ft). They have sensitive eyes which include a tapetum lucidum and many rods which help them see better in dark water, as they are most active at night. They are opportunistic hunters, feeding on cuttlefish, squid, snipe eels, small sharks, and other fish found around their deep reef and volcanic slope habitats. Their abundance of fins allow for high maneuverability, and coelacanths can orient their body in almost any direction in the water. They have been seen doing headstands as well as swimming belly up. They are able to slow their metabolisms at will, sinking into less-inhabited depths and going into a hibernation mode to conserve energy.

Coelacanths are ovoviviparous, with the female retaining the fertilized eggs within her body while the embryos develop over a gestation period of five years. The female will give live birth to around 5-26 young. Young coelacanths resemble the adult, but carry an external yolk sac below their pelvic fins, and have larger eyes relative to body size. Individual coelacanths may live as long as 80 to 100 years.