#paul motian trio

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

paul motian trio ft. bill frisell, joe lovano -- portrait of t.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Various Artists - Music With 58 Musicians, Volume One (1980)

#ecm records#keith jarrett#old and new dreams#steve reich and musicians#codona#gary burton#chick corea#john abercrombie#ralph towner#jack dejohnette's special edition#paul motian trio#art ensemble of chicago#steve kuhn#sheila jordan band#charlie haden#jan garbarek#egberto gismonti#pat metheny group#loading

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Brilliance of Keith Jarrett: A Jazz Legend

Introduction: Keith Jarrett is a name synonymous with virtuosity, innovation, and boundless creativity in the world of jazz. Born seventy-nine years ago today on May 8, 1945, in Allentown, Pennsylvania, Jarrett’s musical journey began at a young age. His prodigious talent was evident early on, and he quickly established himself as a gifted pianist and composer. Early Career and Formation of the…

View On WordPress

#American Quartet#Art Blakey#Charles Lloyd#Charlie Haden#Dewey Redman#Gary Peacock#Jack DeJohnette#Jazz History#Jazz Pianists#Keith Jarrett#Michala Petri#Michelle Makarski#Miles Davis#Paul Motian#The Köln Concert#The Standards Trio

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

I know it's only been a week, but I'm bringing Charlie Haden back, this time has part of the Keith Jarrett Trio with Paul Motian. Some people don't love this because if you listen to enough Jarrett, there's typically a lot more rhythmic angularity and harmonic complexity. This really is just a bluesy folk song--Somewhere Before is right after Restoration Ruin--and I feel like you can hear him working out what he wants to do with what was then the new popular music.

I love Motian on this. It's just propulsive enough and then he pushes things for three minutes and then elegantly gives Haden a little more room for his solo and gradually brings things around again.

Bob Dylan, too, for writing a hell of a song.

#my back pages#keith jarrett trio#keith jarrett#charlie haden#paul motian#somewhere before#bob dylan#our daily jam#Youtube

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

Martial Solal

French jazz pianist who loved to improvise and wrote the score for Jean-Luc Godard’s film A Bout de Souffle

A squint through the metal fence around Martial Solal’s tree-shrouded villa, in Chatou, the suburb of Paris known as the “ville des impressionistes”, could have confirmed that the great French pianist was not the average jazz musician. Solal, who has died aged 97, was the most famous jazz musician in France from the 1950s onwards, and widely known across Europe and the US.

The breakthrough that paid for that Chatou villa came when Solal – then a little-known club pianist – wrote the score for Jean-Luc Godard’s 1960 film A Bout de Souffle (Breathless). The commission came out of the blue via Godard’s jazz-loving friend and fellow director Jean-Pierre Melville, and Solal collected royalties on it for ever after. “It’s like I won the Lotto,” he said in 2010. “Because back in 1959 when I did it, I was mainly just known for being the house pianist in the Saint-Germain-des-Prés jazz club.” Godard had few ideas about the music he wanted, beyond joking to Solal that he might compose a piece for a banjo player, to save money. The pianist promptly produced a soundtrack for big band and 30 violins.

Solal went on to work on several more films, and was one of the first Europeans to perform at the Newport jazz festival in the US. Into his 80s, he could still walk the tightrope of unaccompanied improvised performance, and his compositions had a signature as personal and harmonically idiosyncratic as Thelonious Monk’s. Solal, who liked stop-start melodies and constant rhythmic changes, wrote elegant pieces that slowly coalesced out of scattered fragments. He loved peppering classic jazz material – even as sacrosanct as Duke Ellington’s – with disrespectful quotes going all the way back to his danceband days in Algiers, the city where he was born.

Solal’s mother, Sultana Abrami, an amateur opera singer, introduced him to classical piano as a child. During the second world war, under Nazi race laws, Martial was excluded from a secondary education because his father, Jacob Cohen-Solal, an accountant, was Jewish. He took jazz clarinet and piano lessons from a local bandleader, with whom he was soon performing tangos, waltzes and Benny Goodmanesque swing. Soon, Fats Waller, Erroll Garner, Art Tatum and the bebop virtuoso Bud Powell began to displace Chopin and Bach among Solal’s keyboard models.

He moved to Paris in 1950 after his military service, and teamed up with the American bebop drums pioneer Kenny Clarke in the house band at the Saint-Germain-des-Prés club. The young pianist’s nervous recording debut was in April 1953 with the jazz-guitar genius Django Reinhardt, who turned out to be playing on his last; Reinhardt died the following month. That year, Solal recorded Modern Sounds with his own trio and also recorded unaccompanied. After working with Sidney Bechet in 1957, he received the commission for the Breathless score.

The word about Solal then began to reach America – both Oscar Peterson and Ellington had been entranced by him in Paris, with Ellington pronouncing him a “soul brother”. In 1963, he played at Newport, with the bassist Teddy Kotick and the drummer Paul Motian; despite barely knowing his new partners, Solal boldly added his 11-minute tempo-shuffling Suite Pour Une Frise to the usual programme of standard songs.

Turning down an invitation to move to the US, Solal led world-class groups in the 1960s and 70s, often including the drummer Daniel Humair, the bassist Niels-Henning Orsted Pedersen, and even an advanced two-bass trio for piano and the double-bassists Gilbert Rovère and Jean-François Jenny-Clark. He also explored fruitful duo partnerships with the American saxophonists Lee Konitz and Phil Woods between the 70s and the 90s, and led innovative big bands, notably on the thrilling Martial Solal Big Band session (for the Gaumont label in 1981) and Plays Hodeir (1984).

An insatiable capacity for self-education helped Solal to develop a characteristically pungent harmonic language. He wrote and performed contemporary classical music and published jazz-piano pieces modelled on the Mikrokosmos educational cycles of Béla Bartók.

In 1989 the Martial Solal jazz piano competition was founded. Its winners have included the Frenchman Baptiste Trotignon and the charismatic Armenian virtuoso Tigran Hamasyan. In the 90s, Solal often worked with the Moutin twins, François and Louis, on bass and drums – both were flexible enough to follow their leader’s tendency to launch a tune without telling them what it was, change key without warning, or turn it into a different song entirely.

As he entered his 70s, Solal seemed to be playing with a revitalised and swashbuckling confidence – as if he was finally sure that he would still sound like himself whether he played within the regular rules, or broke them. In 1999, he won Denmark’s Jazzpar prize, and celebrated by writing parts for the accompanying Danish Radio Jazz Orchestra owing as much to the French impressionist classical composers as to jazz. In that decade, Solal also had an unprecedented 30-concert solo run on French national radio.

In 2000, with his 12-piece Dodecaband, he recorded Martial Solal Dodecaband Plays Ellington. During the following decade, he recorded two live albums at the Village Vanguard in New York; the brilliant unaccompanied session Solitude; the duet Rue de Seine, with the trumpeter Dave Douglas; and the Exposition Sans Tableau session for his woodwind-less, brass-packed Decaband – a typically quirky lineup featuring Solal’s talented daughter Claudia singing the roles of a missing sax section.

His final public performance was a solo concert in 2019, at the Salle Gaveau hall where he had made his Paris debut in 1961. After a masterly exposition later issued on the album Coming Yesterday, Solal’s typically elegant exit was prefaced by the words: “I don’t want to bore you. It’s better that you leave here serene.” Then he played “a nice chord like this” – a single F major – said “Voilà. Merci” and left the stage.

Solal undoubtedly loved improvisation, but he believed it needed the spur of challenging composition to stop improvisers from slipping into habits. Not everyone shared his enthusiasm for musical jokes and maybe Solal was unnecessarily diverted by whether or not jazz could satisfy what he saw as classical listeners’ expectations of “perfection”. But he was a jazz-lover to his nimble fingertips, nonetheless. Speculating that probably no more than 10% of his fellow countryfolk knew anything about jazz, Solal phelgmatically declared that “as long as we can live, and play the music we like, it’s too bad for the 90%. It’s their loss.”

Solal is survived by his wife, Anna, their son, Eric, and daughter, Claudia, two grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

🔔 Martial Saul Cohen-Solal, musician, born 23 August 1927; died 12 December 2024

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bill Evans Trio – Autumn Leaves

From the album “Portrait In Jazz” (1959)

Bill Evans – piano

Scott LaFaro – bass

Paul Motian – drums

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Memoirs (1992, Soul Note) was recorded by the Paul Bley/Charlie Haden/Paul Motian trio in July of 1990 in Milan. Three tunes written by my father were included, including "Dark Victory".

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

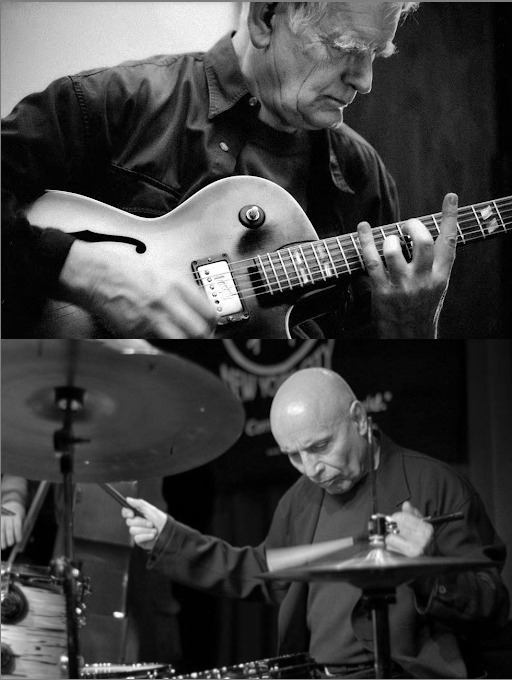

Derek Bailey / Paul Motian — Duo in Concert (frozen reeds)

Specializing in archival recordings, the Helsinki frozen reeds label has come up with another doozy. This time unearthing in the Incus archives previously unreleased concert recordings of guitarist Derek Bailey and drummer Paul Motian for the release "Duo in Concert." Released at the tail-end of 2023, the LP version captures the duo live at the 1990 Jazz Marathon at De Oosterpoort festival in the city of Groningen, the Netherlands. As bonus digital tracks, the label offers recordings made at the New Music Cafe in New York City in 1991. A conversation between Bill Frisell and Henry Kaiser discussing these recordings and their collective experiences playing with Bailey and Motian is included as liner notes.

It's hard to approach a recording from two of my all-time favorite artists with any sense of objectivity, not to mention a heavy dose of expectation. And with a pairing that — at least on paper — doesn't immediately make outright sense, a certain degree of trepidation preempts the initial listening process as well. Accounts of both Bailey and Motian's contrariness and adversarial approach to performing are legion. Having seen both musicians live, I always had the feeling that everything could go off the rails at any moment. There was a certain sense of peril and uncertainty that pervaded their music — and not only because what they were doing was risky but more because they didn't seem to adhere to any rules of musical decorum.

When I first saw Bailey play solo in the mid-1980s, he broke off his set mid-concert to start sharing what seemed like random anecdotes with the audience, then picked right back up and started to play all over again. He stopped abruptly once more a bit later to tune his guitar (actually not much unlike what goes on in Indian classical music). It was almost as if he didn't see the point of himself being there. What he played — when he actually played — was undeniably brilliant. But his attitude came across as ambivalent and irascible, to say the least.

Similarly when I caught Motian in the early 1990s with his trio of Bill Frisell and Joe Lovano, he seemed to revel in the act of eloquent disruption, of not letting things ride but of seeking to derail and create situations where the music took sudden turns down unknown roads. Motian soloed like a kid discovering the drums for the first time, alternately bashing the toms or dropping bombs of bass drum cymbal crashes, then suddenly shifting to exquisite brush work on the snare, echoing his time with Bill Evans.

So, what was I to think of this improbable pairing? Obviously, from the start I was rooting for them. These guys were my heroes. But heroes also fall. I'm happy to say that over repeated listens "Duo in Concert" did not disappoint for one second of these recordings. It would be interesting to know if this concert in Groningen was their first meeting, or if they'd had the chance to play together in a more informal setting beforehand, because the 35-minute set sounds so fresh and invigorating. As if they had met for the first time, discovering their shared language and limitations in real-time before a festival audience. Adding to this the music also comes across as very intimate, as if Motian and Bailey had already played many years together and were picking up on a conversation they'd been having the last time they met. Consequently, both players sound not only completely engaged with the music, but actually excited by what they're coming up with. Practically as though they found themselves in a perpetual state of surprise and delight for the entire length of the concert. "Duo in Concert" is truly an inspiring listen.

There is much to expect that actually transpires: Bailey's spikey, chromatic fields played in jagged rhythmic runs across an incredibly wide dynamic range, spanning the spectrum from ringing harmonics on the verge of feedback to barely caressing the strings with his pick. And then there's Motian's incredible brush work paired with bombastic tom fills and tremorous bass drum drops. The real mystery is how this all manages to coalesce into — for lack of a more apt expression — an undeniable example of sheer poetry in sound. The mutual respect and inspiration between Motian and Bailey so evident in these recordings is in itself one of the most compelling aspects of this release.

A major unifier here would have to be Bailey and Motian's shared backgrounds in jazz. Bailey used to refer to himself in his earlier musical incarnation as previously sounding something like Jim Hall. But of course by the mid-1960s had realized he would, as Henry Kaiser states in the liner notes, have to depart for Planet Improv and leave the world of jazz behind. By this point in his long career Motian still had certainly more invested in the jazz tradition but seemed not to worry about what this meant. He'd long since moved on beyond what the rule keepers of the jazz world had imposed. Yet Motian also never went totally free like Bailey. And in fact, this would be the first record I'd heard where Motian plays from scratch, without any vague road map or composition to steer the musical proceedings.

But it is precisely this jazz background which lends an unmistakable narrative thread to the concert at Groningen. Bailey and Motian's collaboration is truly like a conversation in the most literal sense of the word. And like the greatest musical conversations in the context of jazz music, both players join together for this one brief point in time to tell a story together, listening and building their musical ideas from their dialogue. As hackneyed as this may sound, the end effect is a perfect example of instant composing, of creating a totally cohesive, rigorously structured piece of music from thin air.

And this encompasses signifiers of a more narrative approach along the way: towards the midpoint of the set, Bailey fades out to let Motian take the practically obligatory drum solo, a roiling, thunderous affair across the toms and cymbals. This is followed by Bailey jumping back in with what in a more conventional jazz piece, could be the main soloist picking up again with another long passage. Along the way Bailey engages in some of the most impressionistic and nearly melodic playing I've ever heard from him, even approaching what one could construe as comping rapid chord variations to Motian's hard-driving pulse. The set ends with Motian playing a very grooving swing pattern on the high hat that not only absolutely works with Bailey's field of dissonant harmonic notes but is in itself a stroke of genius, melding the two worlds of jazz and obdurate free improvisation with a gesture of contrast and a nod to the history both of these musicians had left far behind but by no means forgotten.

For fans of Derek Bailey and Paul Motian "Duo in Concert" is an absolute must listen. For those unfamiliar with either of these artists' work, this release would be a great place to start, not only because it captures them both at the height of their powers but is also a convincing and highly moving documentation of free improvised music that shouldn't be missed.

Jason Kahn

#derek bailey#paul motian#duo in concert#frozen reeds#jason kahn#albumreview#dusted magazine#jazz#Jazz Marathon at De Oosterpoort#live#free improvisation

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scott LaFaro, Bill Evans & Paul Motian

(English / Español / Italiano)

In December 1959-June 1961 Bill Evans formed a musical collaboration with drummer Paul Motian and double bassist, Scott LaFaro. This inter-pair alliance revolutionised the concept of the piano trio by proposing the abandonment of the old scheme of accompanists in front of the main soloist and replacing it with a three-way dialogue with perfectly complementary voices.

(listen here)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

En diciembre de 1959-Junio de 1961 Bill Evans formó la colaboración musical con el batería Paul Motian y el contrabajista, Scott LaFaro, esta alianza interpares revolucionó el concepto de trío de piano, al proponer el abandono del viejo esquema de acompañantes frente al solista principal y sustituirlo por un diálogo a tres con voces perfectamente complementarias.

(escucha aquí)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Nel dicembre 1959-giugno 1961 Bill Evans stringe una collaborazione musicale con il batterista Paul Motian e il contrabbassista Scott LaFaro. Questa alleanza tra coppie rivoluziona il concetto di trio pianistico proponendo l'abbandono del vecchio schema degli accompagnatori davanti al solista principale e sostituendolo con un dialogo a tre con voci perfettamente complementari.

(ascolta quì)

Source: Jazz y algo más / posted by Adrian Bernal

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

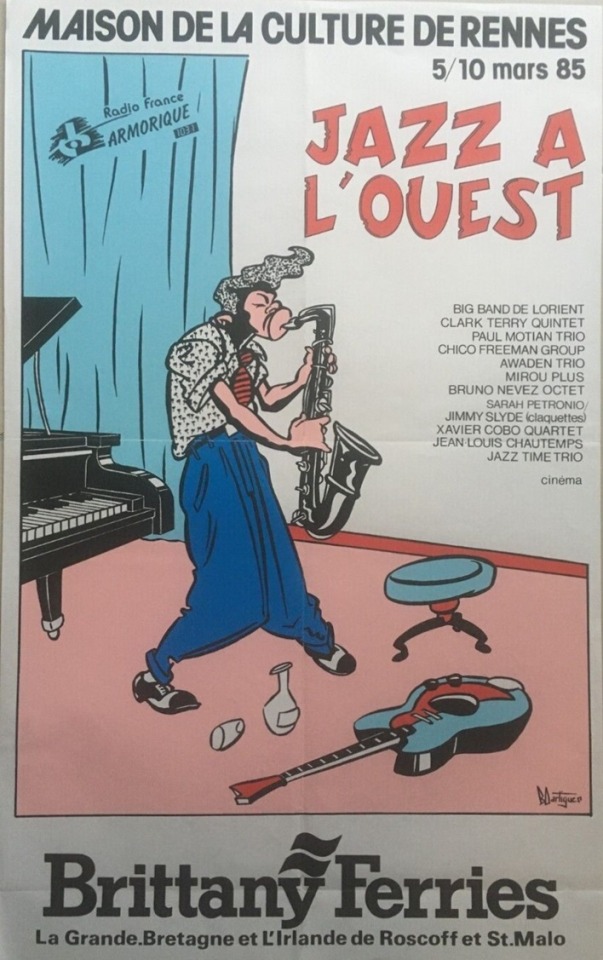

1985 - Jazz à l'Ouest - Maison de la Culture de Rennes

Big Band de Lorient

Clark Terry Quintet

Paul Motian Trio

Chico Freeman Group

Jimmy Slyde

Xavier Cobo Quartet

Jean-Louis Chautemps

...

#jazz#poster flyer#clark terry#paul motian#chico freeman#jimmy slyde#xavier cobo#jean louis chautemps#1985

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

CONSIDERING KEITH JARRETT’S AMERICAN QUARTET

At the end of February, pianist/critic Ethan Iverson called his Transitional Technology/Do the Math readers’ attention to an YouTube interview with Keith Jarrett conducted by Rick Beato. Besides archival performances, commentary, and conversation, there were incredibly poignant latter-day one handed performances. Post-strokes the genius is still there, but it is cut literally in half.

Keith Jarrett was hugely influential on me as a new jazz fan. As with so many, that he played with Miles Davis (electric piano and organ (!?!) on at Fillmore and Live-Evil) put him on my radar. I had the Bremen/Lausanne solo concerts even before the justly legendary Koln. I had Belonging by the European Quartet and Reflections and Fort Yawuh with Dewey Redman, Charlie Haden, and Paul Motian. I also really liked the album with Gary Burton from this same period. More on that later.

I liked my albums and played them frequently. When the 10 discs of Sun Bear came out as the next solo concerts, that was too expensive for me to be a completist. As remarkable as Bremen/Lausanne and Koln were, I felt I knew what Jarrett was up to. Those vamps, melodies, gospel elements, free breakdowns were also present in the band records. It was all conceptually fascinating, but the experiments and juxtapositions were always adventurous but not always successful. In the moment, there too I thought I had a bead on what was going on, but didn’t think I needed more.

When I returned to the music, the Standards Trio with Gary Peacock and Jack DeJohnette better suited my aesthetic. I found “my” albums again and gave them a single fond refamiliarizing listen. I have now listened to all the American Quartet albums and a 3 1/2 hours playlist derived from Iverson’s extensive, tune-by-tune review of the band’s entire output. He is quite impressed with the later Shades of Jazz and some of Bya-Blue too.

But with those exceptions, I don’t think I missed that much and so bristle a little bit at the suggestion that this was the last great band. As a contrarian, I nominate the Dave Holland Quintet and maybe Woody Shaw’s band. But it was something special—a young phenom recruits the elders Paul Motian from THE Bill Evans Trio and Dewey Redman and Charlie Haden from Ornette Coleman and ambitiously mashes them up with elements of his own aesthetic from the solo concerts.

It’s an interesting mix—Motian’s free sense of time up against Haden’s solidity with Redman’s earthy primitivism at the service of Jarrett’s capacious vision. Again, it’s not always successful, but they are unavoidably interesting.

Iverson doubles down on a judgment drawn from initial reportage that Jarrett didn’t do his bebop homework because of this:

“In the Beato video, Jarrett says that when he was finding his voice, he didn’t want to play modal like McCoy Tyner. He then says he wanted to be more “Bach-ian,” meaning voice-leading in the contrapuntal European tradition like Bach.”

So, yes, Jarrett has a cerebrality that maybe wears thin or that prompts admiration first with affection following—or not.

But the other interesting idea is that there is a Midwestern “country” or at least folk aesthetic that draws on major chords. Iverson draws a line that also includes Pat Metheny, Charlie Haden, Gary Burton, and even Ornette—and maybe Fred Hersch from Cincinnati belongs too. And that makes the Jarrett/Burton album stand out as probably the best Jarrett band album. Burton and Steve Swallow with his compositions structure and rein in Jarrett while he adds to a tough appealing set.

I am left after this valuable exercise with fond memories and admiration for Keith Jarrett, but my affection still lags.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scott LaFaro: Revolutionizing the Role of the Bass in Jazz

Introduction: Scott LaFaro was a jazz bassist whose brief yet impactful career revolutionized the role of the bass in jazz. Best known for his groundbreaking work with the Bill Evans Trio, LaFaro’s innovative approach to bass playing helped to redefine the possibilities of the instrument, inspiring generations of bassists to come. In this blog post, we will explore the life, music, and legacy of…

View On WordPress

#Bill Evans#Bill Evans Trio#Jazz Bassists#Jazz History#Paul Motian#Scott LaFaro#Sunday at the Village Vanguard

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bill Evans, Scott LaFaro, Paul Motian, un trio de rêve...(clin d'oeil à Alex Dutilh pour ses 40 ans de radio)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Waltz for Debby – Bill Evans

Waltz for Debby (1961) by Bill Evans Trio is a quintessential live jazz album, recorded at the Village Vanguard and showcasing Evans' delicate touch and deep emotional expression. The title track, dedicated to his niece, is a stunning example of his lyrical piano style, blending impressionistic harmonies with fluid improvisation. Backed by Scott LaFaro on bass and Paul Motian on drums, the trio’s chemistry is unmatched, making each performance feel intimate and spontaneous. A timeless masterpiece that captures the essence of jazz elegance.

I'll probably keep making pixel arts of album covers, so if you have any suggestions, feel free to let me know. If you're going to use my content or upload it to other sites, please let me know.

#art#music#pokemon#artists on tumblr#rock#vinyl#album#pixel art#jazz#vinylcollection#BillEvans#WaltzForDebby#JazzTrio#ScottLaFaro#PaulMotian#ClassicJazz#PianoLegend#VillageVanguard#JazzImprovisation#ModalJazz#VinylCollection#TimelessMusic#MusicMasterpiece#LegendaryAlbum#CoolJazz#LiveJazz#EssentialJazz#JazzPiano#IconicAlbum#MusicRock

1 note

·

View note