#parochet

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

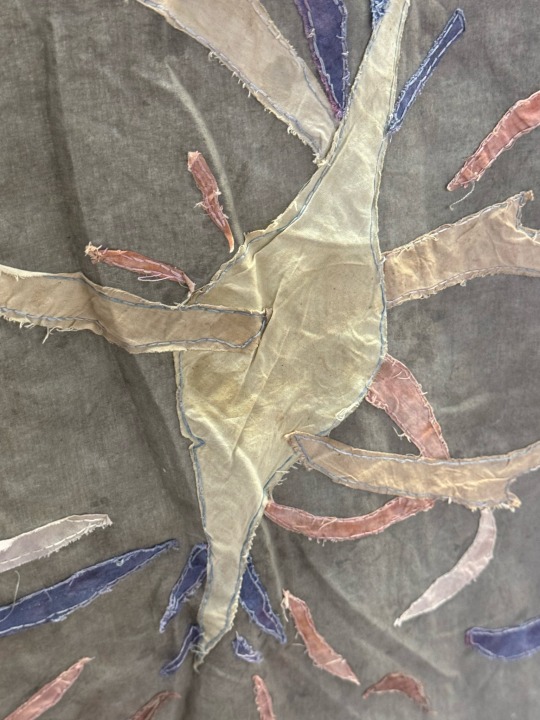

My fiber arts final! This is what I was working on instead of any of my normal illustration. It’s a Torah ark cover— a parochet— and it’s meant to commemorate the Simchat Torah Pogrom. The bit in the middle is a supernova, while the bits at the sides are meant to be either grain or challah, representing the kibbutzim. The Hebrew reads “We will dance again,” in reference to Mia Schem. All naturally dyed. Anyone clowning in the notes will be immediately blocked.

IMAGE ID: A series of photographs of a curtain hung in front of a wall. The curtain has a grey background and a number of appliqué pieces sewn on with embroidery floss. In the center is the image of a supernova and it’s framed by pillars of wheat like brown leaves on each side. On the top is a yellow crown, while on the bottom is the Hebrew: עוד נרקוד שוב. The Hebrew lettering is in pink and is attached with a pale yellow satin stitch. The first photograph is of the entire piece, while the other three are detail shots of the supernova, the wheat, and the crown. END ID.

#my art#sewing#embroidery#appliqué#judaica#parochet#October 7#jumblr#Jewish#simchat torah pogrom#am yisrael chai#fiber arts#natural dye

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

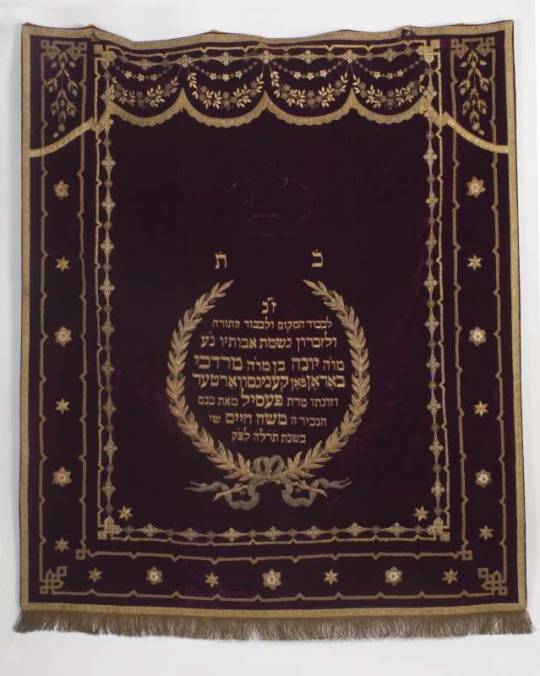

Parochet, (curtain of the Torah shrine), 1833, Silk damask, metal threads, cotton, Donated to the Stadttempel, Vienna, by Hermann Todesco, Jüdisches Museum Wien, Vienna

Installation view of The Hare with Amber Eyes. The Jewish Museum, NY. Photo: Iwan Baan.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

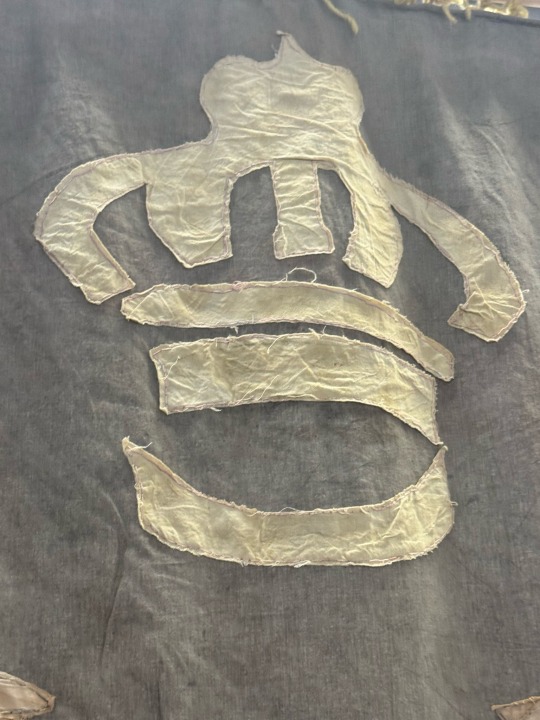

Parochet from Vienna, Austria (?), 1875.

The Hebrew reads: abbreviation for Torah Crown; dedication in memory of Yonah, son of Rabbi Mordechai Baron Kenigswarter, and his wife Pesil from their son Moshe Hayim, and the Hebrew year. A later inscription, handwritten on a piece of parchment and stiched to the lining, mentions that the curtain was restored and generously donated by the members of the Congregation of the Sick; the verse "He will shelter me in His pavilion on an evil day, grant me the protection of His tent (Psalms 27:5) indicates the Hebrew year [5]691 (1931)".

67 notes

·

View notes

Note

So re your tags on the pope post...

Where's the menorah krindor?

So, starting at the very beginning.

70 CE: Titus sacks Jerusalem and loots the Second Temple. In his triumph (fancy war parade) he has the Menorah, as is recorded by Josephus Flavius in 71 CE and by the Arch of Titus' reliefs in 81 CE

The Menorah is displayed in the Tempulum Pacis in Rome, and 2nd century CE Rabbis claim to have seen it in Rome, as well as various other artifacts from the desroyed temple including the parochet and the choshen.

Now here's the thing. This is the last time historical texts mention the Menorah by name so everything below here needs to be taken with an increasing pile of salt

410 CE: The Visigoths sack Rome. Procipius of Ceasarea (500-560), a Byzantine Historian, writes that the Visigoths take "treasures of Solomon the King of the Hebrews." If this includes the Menorah, the trail goes cold. So that's it right? The Menorah got taken to a secondary location and was lost forever, right?

Wrong, because that's not the only time Procipius mentions Jewish Temple loot.

425 CE: The Vandals sack Rome again, to the point where the word vandalize comes from it. Procipius notes that their leader, Geiseric, takes "a huge amount of imperial treasure" with him to Carthage, which was at that time the Vandal capital.

Trust me this is relevant

534 CE: The Byzantine Emperor Justinian sacks Carthage, and they hold a triumph in Constantinople. Among the paraded items are "treasures of the Jews, which Titus, the son of Vespasian, together with certain others, had brought to Rome after the capture of Jerusalem”

That these "treasures of the Jews" include the Menorah is not a new theory, as is indicated in the 19th century painting Geiseric sacking Rome by Karl Bryullov

(Note the Menorah)

So it's in Istanbul right?

Wrong, because our boy Procipius isn't done yet: according to him, Justinian sent the "treasures of the Jews" to Christian sanctuaries in Jerusalem, since he heard that they were cursed that any city save Jerusalem that held them was doomed to be sacked.

This is the last time the "treasures of the Jews" are mentioned in historical texts.

So for our next step, lets look at major churches in Jerusalem in the 6th century, and officially enter the cork-board and string section of this rant post.

As well as the extant Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the Hagia Sion Basilica, and the Church of the Holy Apostles, Justinian built a church himself in the city, called the Nea, in 534 CE, just nine years after sacking Carthage. It would not be unreasonable that he'd send the Menorah to his own church, so we can theorize that it's in the Nea for the remainder of the 6th century (there are, of course, problems with relying on one historian's account of these things, but this is for fun, not a published article)

So that's it? It's in one of the churches of Jerusalem?

...

So in 614 CE Jerusalem gets sacked by the Sasanian/Persian Empire, who according to historical records destroy all the churches.

Now here's the thing. Recent archaeological evidence gives rise to the possibility that our Byzantine historical sources are trying to stir up outrage against the Sasanians: While mass graves dating to around 614 CE were found, the churches and Christian residential neighborhoods were barely, if at all, damaged, and the Nea itself was very possibly completely undamaged. This is, however, a recent theory, and the academics are still hashing it out.

So it may be in one of the churches of Jerusalem?

Tragically, even if the 614 siege didn't get the churches, in 1009 the Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah destroyed all churches, synagogues, and many religious artifacts of both Christians and Jews in Jerusalem. So if by some miracle the Menorah had survived until this point, if it was in Jerusalem it was most likely destroyed.

But that's disappointing, and what's a good conspiracy theory without going a step or two beyond what is reasonable?

Apparently, while the churches, synagogues and most of the artifacts were destroyed, at least in the case of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, objects that could be carried away were looted, rather than destroyed. And if we know anything about the Menorah at this point, that thing is certainly able to be carried away by people.

If the Menorah was looted rather than destroyed, it's not unreasonable that it would have made it's way to the Fatimid capital of Cairo. However, as the historical record dried up some 500 years beforehand, beyond this point it's unreasonable to attempt to track the Menorah.

So that's it. If the Menorah wasn't destroyed it most likely made its way to Egypt and was lost or destroyed there.

Is what I'd say if I wasn't so far down this rabbit hole I was beyond reason. Because as we all know there's one place that has all the significant treasures of Cairo and a penchant for looting:

The British Museum

#i cant in good conscience call this either archaeology or history#anyway this is very unhinged but was fun to research#pseudoarchaeology#pseudohistory#jewish stuff

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

#art#joe turpin#painting#artist#turpin#contemporary art#africa#contemporary african art#installation#installation art#jewish art

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jesus Splits the Rock. From Matthew 27: 51-56.

Many Christian sects teach the interior of the Jewish Temple is flawed, and that is why the Curtain around the Holiest of Holies was torn when Jesus was crucified. As if the death of Christ was an unveiling of the Spirit of God that could be purchased in no other way. This is not acccurate.

A correct analysis of the famous section where the Curtain is shorn will help us understand what really happened in this section of the Gospel of Matthew and why.

The Holiest of Holies was not inaccessible within the Jewish Temple. It was indeed buried behind curtains, mostly goat curtains representing the immature selves that must be shorn off the frame in order to fully appreciate God, but in no way is the Presence of God forbidden, nor is His Covenant exclusive.

The Hebrew word for the Curtain, parochet refers to the lining of the womb. Within the interior of the parochet, one is at one with God, the Parent of us all. Just as in physical birth, the shearing of the Curtain during the crucifixion is the start of a new state of independence from God.

Why would the Gospels suggest this was necessary, and why did Christ have to die for it to begin? The splitting of rocks, the resurrection of the dead, all of these things imply the onset of Mashiach, a state of global independence, one that has never reached every corner of the world:

51 At that moment the curtain of the temple was torn in two from top to bottom. The earth shook, the rocks split 52 and the tombs broke open. The bodies of many holy people who had died were raised to life.

53 They came out of the tombs after Jesus’ resurrection and[e] went into the holy city and appeared to many people.

54 When the centurion and those with him who were guarding Jesus saw the earthquake and all that had happened, they were terrified, and exclaimed, “Surely he was the Son of God!”

55 Many women were there, watching from a distance. They had followed Jesus from Galilee to care for his needs.

56 Among them were Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James and Joseph,[f] and the mother of Zebedee’s sons.

Mary Magdalene= "Love in the Highest"

Mary= Love

James=who closely follows

Joseph= the most fruitful

Sons of Zebedee=the "idea of Zebedee" had to do with the understanding that humanity progresses not because of the efforts of people but because humanity is part of the universe, which progresses by natural law.

So in the final verse we get the answers to the mysteries of the ones before it. "Who experiences love in the highest and follows the natural laws of creation bears the most fruit."

The Values in Gematria are as follows:

v 51-52: The Value in Gematria is 10390, אאֶפֶסגטאֶפֶס apesgatapes, "a vision of peace that involves the winepress and the fruit of the tree."

Death in Judaism is death due to shame, to ignorance, to practices that do not cause suffering to passover. To split the curtain and the rocks and raise the dead is to press life like a grape of all of its essence. It is the moment we finally believe in the Guiding Light of the Christ and His Homily.

v 53: The Value in Gematria is 6741, וזדא , zada, "That which understands. At last!"

The demonstrative pronoun and adverb זה (zeh) or זו (zo) or זאת (zo't; feminine), meaning that or which, happens in various but comparable forms all over the Semitic language area.

The verb עדה ('ada I) means to pass on or by, or to advance. It's used only twice in the Bible: Job 28:8 speaks of an advancing lion, Proverbs 25:20 speaks of a garment that's being passed by. This root's three derivations are in fact three times the same word but used in three distinct categories:

The masculine noun עד ('ad), also spelled ועד (w'ad), literally meaning advancing time. This word is usually translated with perpetuity or forever: of past time (Job 20:4), but most often future time (Psalm 21:6). In the latter case the form is usually לעד (l'ad), literally for always.

The identical masculine noun עד ('ad), literally meaning that upon which one advances: prey or booty (Genesis 49:27, Isaiah 33:23).

The identical preposition or conjunction עד ('ad), also spelled עדי ('ady), meaning as far as, until, up to, while, to the point that, etcetera. This multifarious word occurs frequently in the Bible.

v 54: The Value in Gematria is 12743, יבצדג, Yv Tsadg, "And He differentiated, became a Tzaddik, a righteous being. A saint."

v 55: The Value in Gematria is 7596, זהטו, "the same." This refers to the universal global use of the Davar, "the words" specifically referring to the onset of Mashiach:

The Hebrew noun דבר (dāvār, with the Hebrew letter "bet" pronounced like a "v") is the word for "word" or "speech." Preceding the construction of the Tower of Babel, Genesis uses דבר (dāvār) to describe the unified "words" of the earth's population as seen in Genesis 11:1, "Now the whole earth had one language and the same words (דבר׳ם)."

After the separation of the man from God results in the appearance of the Saint, then comes the separation of humanity from Pharaoh, all the evil men and their ways. This is not an option, it is what God has commanded of us. We must achieve Mashiach.

v 56: The Value in Gematria is 5801, הח אֶפֶסא, Ha Ephesa, "Witness the Future."

=Mashiach.

0 notes

Photo

Torah Curtain: Central Panel, 1735, Brooklyn Museum: Decorative Arts

Green velvet panel, originally central panel of Torah curtain (parochet), embroidered with metallic threads, silk brocade and metallic trim. On top, Torah crown with Hebrew inscriptions [see catalogue sheet] and appliqué Hebrew inscriptions which read, "Torah Crown donated by Rabbi Eleazer (Katzenellenbogen) son of the Gaon Rabbi Moishe - may he live - in the year 1735 and his wife the virtuous Rifka daughter of the Gaon Rabbi Samuel Hillmann" [see catalogue sheet in Decorative Arts departmental files for Hebrew]. Panel may have formed a part of a Torah mantle rather than a curtain. Condition: Fair. Much of the metallic embroidery is worn, as well as the velvet. The opening between the curtain and its backing at the bottom of the textile does not appear to be a tear, but rather a part of the design. Size: 19 x 38 in. (48.3 x 96.5 cm) Medium: Velvet embroidered with metal threads, silk brocade, metallic trim

https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/2203

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Preparing for the End

And so we finally come to the end of our festival season. Not quite, but almost! Shemini Atzeret, the next-to-last stop on the holiday bus line, looms before us in all its mysterious opacity and then, finally, we get to Simchat Torah…the last stop of all before it’s all finally really over and the “real” year really begins with all of its tasks and challenges.

All of our Jewish festivals have features that are to some degree out of sync with the modern world, but Simchat Torah is in some ways the most egregiously out of step with the values moderns espouse and which we teach our children to esteem. In a world that values efficiency, Simchat Torah is about doing something—in this case, pondering the text of the Torah and mining in its quarries for new meaning and renewed inspiration—in a way that couldn’t possibly be less efficient: by reading it aloud slowly and precisely, over and over and over, year in and year out. In a world that values speedy attention to pressing matters, we could not possibly do our pondering more ponderously…or more laboriously. And, of course, we don’t just read the text out loud, we chant it according to a set of musical notes that, because they are not actually written in the scroll, must be memorized in advance. It’s true that those signs serve as a kind of bare-bones punctuation system, but what they really do is make it impossible to race through the text at breakneck speed even for the most accomplished reader. Instead, each word is sung out, thus of necessity separately pronounced and individually presented to the congregation for its ruminative contemplation. Most Americans, of course, are done being read to when they learn how to read in first or second grade. But shul-Jews are never done…and we never quite finish either: as soon as we get to the last few lines of the Torah, we open a different scroll to the very first column and start reading again. Again.

We train our students in school to read as quickly as possible. I remember occasionally having to read several hundred pages from one class to the next in college and graduate school, which, since I was generally taking at least four or five courses at once, meant having to develop the skill not only of reading at top speed but also somehow of retaining all, or at least most, of the insane number of pages I was attempting to read at once. I took notes, obviously. But even that had to be done according to a streamlined system that didn’t impede my progress too dramatically. The key was to find the right balance between volume and comprehension: reading without recalling content was useless, but not getting through the reading assignment before the next class was not a very good plan either! In the end, I learned how to read very quickly, which skill I retain to this day. And I remember most of what I read too. So there’s that!

But there’s reading and there’s reading…and to participate in the annual reading of the Torah requires learning to read extremely slowly, carefully, and deliberately. It requires being open to insights hiding behind the details of a confusing narrative or a complex exposition of details regarding some abstruse area of law. Mostly, it requires a level of humility that no professor in grad school sees any point of attempting to instill in his or her students: listening week in and week out to the weekly lesson, on the other hand, requires bringing a level of surrender to the enterprise that stems directly from knowing that the same text read this week will be read aloud next year (and the year after that as well), yet knowing that none of us will ever truly get to the point at which we’re done learning, at which we’ve simply managed to squeeze all the juice there is to have from that particular orange, at which there is simply no point to review the same text again again. The bottom line is that you can’t read Scripture too slowly, too deeply, or too carefully! But who in our modern world wants to do anything slowly at all?

This much I know from shul and from study. But how surprised was I to learn just recently that I’m not alone—that Jews are not alone—in their devotion to the art of the slow read.

As far as I can tell, the earliest non-Jewish author to write positively about the experience of reading slowly was, of all people, Friedrich Nietzsche, who described himself in the introduction to his The Dawn of Day as a “teacher of slow reading.” Okay, that was in 1887, but he was only the first of many who argued that the relentless emphasis on reading quickly has had a peculiarly negative effect on Western public culture. In 1978, James Sire published How to Read Slowly, a call-to-arms in which he invited Americans to learn how to read thoughtfully, not racing to get any specific book finished but instead using the experience of reading as a kind of internal gateway to ruminative speculation about the world through the medium of the written word. In 2009, his work was followed by John Miedema’s Slow Reading, an interesting book in which the author finds traces of encouragement to read slowly in classical sources and then moves slowly forward to find similar kinds of ideas in works from later centuries as well. Then came Thomas Newkirk’s 2012 book, The Art of Slow Reading, And then came David Mikics’ Slow Reading in a Hurried Age, published by Harvard University Press in 2013.

Mikics comes closest to what Jews mean by reading slow. He identifies slow reading with intensive, thoughtfully ruminative reading and approvingly cites Walt Whitman, who wrote that “reading is not a half-sleep, but, in the highest sense, a gymnast’s struggle…Not the book so much needs to be the complete thing, but the reader of the book does.” That’s pretty much why we read the Torah over and over in shul: not because the book needs to be read but because the kahal needs to be read to…and through the experience of being read to and thus obliged to consider word by word an ancient text, and to do that same thing over and over without being bored or irritated—that is what we mean by the book being a door to step through into the world behind the world, into the space that Plato labelled “the world of ideas” but which Jewish people know as the world behind the great parochet that separates the day-to-day world of human goings-on from the larger picture of the human enterprise, the one in which we participate willingly not because we can or because we must, but because we wish to see ourselves as willing witnesses to God’s presence in history, and as harbingers, each of us, of the redemption promised by the very scroll we read so deeply and thoughtfully year after year after year.

David Mikics is a professor of English at the University of Houston. I have used and enjoyed his edition of Emerson’s essays since the book came out in 2012; when I’ve occasionally discussed Ralph Waldo Emerson in these weekly letters, I’ve almost always been relying on the text Mikics published and on his thoughtful introductions and notes. In his book, he distinguishes slow reading from its partners in insight, “close reading” (a term coined at Harvard more than half a century earlier by Professor Reuben Brower) and “deep reading” (a term coined by Sven Bikerts, the author best known for his Gutenberg Elegies, the subtitle of which, “The Fate of Reading in an Electronic Age,” tells you most of what you need to know about this thesis). Mikics book is very worthwhile…and worth reading slowly and carefully.

Much of what he writes will be challenging for all who care deeply about the fate of the written word in the digital age. But large sections of the book—written in an engaging, very appealing style—will be resonant in a special way for Jewish readers. We are the original slow readers! And Simchat Torah is our annual festival devoted to the celebration of that very concept. So, as we prepare for the final days of our holiday season, I encourage you all to focus on the larger enterprise in play: the celebration of slow, intensive, deep, close reading that is the hallmark of the way Jews relate to the sacred text. Each word, after all, is a gateway to the world behind the world, to the sacred space in which the knowledge of God, for all it comes to us dressed up in language, is not language or anything like language…but an amalgam of hope, faith, courage, and dreamy optimism. The bottom line: you really can’t read too slowly…and Simchat Torah is our annual opportunity to pay public homage to that quintessentially Jewish idea.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

yesterday’s message from Israel365 about ancient mirrors

to be accompanied by a post of Hebraic History from John Parsons:

According to tradition, Moses descended from Sinai (with the second set of tablets) on Yom Kippur (Tishri 10), and on the following morning he assembled (וַיַּקְהֵל) the people together to explain God’s instructions regarding building the Mishkan (i.e., Tabernacle). First, however, Moses reminded the people to observe the Sabbath as a day of rest, and then he asked for contributions of gold, silver, bronze, and other materials for the construction of the sanctuary and its furnishings. Each contribution was to be a “free-will offering” (i.e., nedivah zevach: נְדָבָה זֶבַח) made by those “whose heart so moved him.” As a sign of their complete teshuvah (repentance) for the sin of the Golden Calf, the people gave with such generosity that Moses finally had to ask them to stop giving!

Betzalel and Oholiav were appointed to be the chief artisans of the Mishkan, and they led a team of others that created the roof coverings, frame, wall panels, and foundation sockets for the tent. They also created the parochet (veil) that separated the Holy Place (ha’kodesh) from the Holy of Holies (kodesh ha’kodeshim). Both the roof and the veil were designed with embroidered cherubim (winged angelic beings). Betzalel then created the Ark of the Covenant and its cover called the mercy seat (kapporet), which was the sole object that would occupy the innermost chamber of the Holy of Holies. Betzalel also made the three sacred furnishings for the Holy Place – the Table of Bread (shulchan), the lamp (menorah), and the Altar of Incense (mizbe’ach ha’katoret) – as well as the anointing oil that would consecrate these furnishings.

Betzalel then created the Copper Altar for burnt offerings (along with its implements) and the Copper Basin from the mirrors of women who ministered in the entrance of the tent of meeting. He then formed the courtyard by installing the hangings, posts and foundation sockets, and created the three-colored gate that was used to access the courtyard. [Hebrew for Christians]

2.20.22 • Facebook

1 note

·

View note

Text

Terumah: "I Will Dwell in Their Midst"

Why did God command us to construct a Temple?

When introducing the Temple and its vessels, the Torah states the purpose for this holy structure:

“וְעָשׂוּ לִי מִקְדָּשׁ וְשָׁכַנְתִּי בְּתוֹכָם”

“Make for Me a Sanctuary - and I will dwell in their midst” (Exod. 25:8).

The goal of the Temple was to enable God’s Presence to dwell in the world. The Mikdash was meant to “open up” channels of communication with God: enlightenment, prophetic inspiration (ruach hakodesh), and prophecy (nevu'ah).

Three Channels

Rav Kook distinguished between three different channels of Divine communication. Each of these channels corresponds to a particular vessel in the Temple.

1. The first conduit relates to the holiest vessel in the Temple: the Holy Ark in the Holy of Holies, which housed the luchot from Mount Sinai. From the Ark emanated the highest level of prophetic vision, the crystal-clear prophecy that only Moses was privileged to receive. As God told Moses:

“I will commune with you there, speaking to you from above the ark-cover, from between the two cherubs that are on the Ark of Testimony” (Exod. 25:22).

This unique level of prophecy is the source of the Torah’s revelation to the world.

2. The second conduit corresponds to the vessels outside the Holy of Holies, especially the Menorah, a symbol of enlightenment and wisdom. This conduit for disseminating the wisdom of Israel extended beyond the inner sanctum and encompassed the Kodesh area of the Temple.

3. The final conduit relates to the Altar of Incense. This is the channel of ruach hakodesh. The phenomenon of prophetic inspiration - which originates in the innermost depths of the soul - parallels the inner service of incense, which was performed in secret within the Sanctuary (דָּבָר שֶׁבַּחֲשַׁאי - see Yoma 44a).

The Atonement of Yom Kippur

The special Temple service performed on Yom Kippur seeks to attain complete atonement. It aspires to cleanse and purify all three levels of communication between man and God.

For this reason, the High Priest would sprinkle blood from the Yom Kippur offerings on precisely these three locations in the Temple:

Between the poles of the Holy Ark;

On the parochet-curtain that separated the Kodesh - including the Menorah - from the Holy of Holies;

On the Incense Altar.

(Adapted from Olat Re’iyah vol. I, pp. 167-168). Illustration image: "The Prophecy of the Destruction of the Temple

0 notes

Text

Maguen David

Seu reconhecimento como símbolo exclusivamente judaico é um fato relativamente recente já que, na Antigüidade e mesmo durante a Idade Média, várias civilizações além da nossa usavam o hexagrama como símbolo místico ou puramente decorativo.

Mas desde o século XIX a Estrela de David tem sido o símbolo mais usado entre os judeus de todas as partes do mundo. Usada por várias comunidades e instituições de todas as tendências, este símbolo pode ser visto em fachadas de sinagogas, assim como em seu interior, sobre o hechal (Arca Sagrada) , em parochet (cortina que cobre a Arca), em lápides e inúmeros outros objetos religiosos.

Durante uma das épocas mais terríveis da história do povo de Israel, quando praticamente toda a Europa estava sob o jugo nazista, estes obrigaram todos os judeus a usar uma estrela amarela nas vestes. Queriam transformar a Estrela de David em um símbolo de vergonha e de morte, mas para os judeus tornou-se um símbolo de sofrimento e heroísmo e da esperança coletiva de todo um povo.

A criação do Estado de Israel fez com que o símbolo marcado pelo sofrimento renascesse junto com a Nação Judaica. O Estado de Israel, o primeiro Lar Na-cional judaico após 2.000 anos de diáspora, ostenta na parte central de sua bandeira uma Estrela de David de cor azul

Para se traçar a origem da Estrela de David na história judaica devem-se levar em consideração dois aspectos. Primeiro, a evolução histórica do nome e do símbolo, que, como veremos mais adiante, ao que tudo indica, em seus primórdios não tinham ligação entre si. Segundo, a interpretação mística do Maguen David.

Evolução histórica

Desde a Idade do Bronze, utilizaram-se estrelas de cinco e seis pontas como decoração ou como elemento mágico, sendo encontradas em ruínas de civilizações tão diferentes e tão distantes como a Índia, a Mesopotâmia ou a Grã-Bretanha. Na Índia, por exemplo, algumas datam de cerca 3.000 anos antes da era comum. Há, ainda, hexagramas em igrejas medievais e bizantinas. No Islã era considerado um símbolo muito importante. A estrela de seis pontas também fazia parte dos emblemas de várias nações e atualmente pode ser vista na bandeira da Irlanda do Norte.

Mas antes de analisar sua evolução histórica, devemos ressaltar alguns aspectos importantes. A tradução literal do termo Maguen David não é Estrela de David, mas sim Escudo de David. O termo “escudo” ou maguen é muito usado nas orações e não se refere à estrela de seis pontas, mas é uma forma poética de referência a D’us, ou seja, à Sua proteção onipotente.

No Talmud, D’us é chamado “Escudo de David” (Pesachim, 117b). Ao afirmar que D’us é o “Escudo de David”, nós o reconhecemos como sendo o único Protetor do rei David e, conseqüentemente, também o nosso. Reconhecemos, assim, que foi unicamente graças à proteção e bênção Divina que o rei David conseguiu suas grandes vitórias militares. A cada Shabat, após a leitura da Haftará, reiteramos este conceito ao dizer “Abençoado sejas Tu, meu D’us, Escudo de David”.

Não está muito claro, porém, como o conceito de D’us como “escudo” acabou entrelaçando-se com a estrela de seis pontas. Há inúmeras suposições, entre as quais uma que afirma que o escudo do rei David era triangular e sobre ele estava gravado o “Grande Nome Divino de 72 Letras” juntamente com as letras hebraicas m(מ), k(ק), b(ב) e y(י) (as letras da palavra Macabi).

Outra suposição é que o símbolo tenha surgido na época de Bar Kochba, no período de 132-135 da era comum. Segundo esta teoria, os judeus que lutavam contra as forças romanas adotaram escudos mais resistentes, em cujo interior foram colocados dois triângulos entrelaçados. Alguns estudiosos, entre os quais Rabi Moses Gaster (grã-rabino sefaradita da Inglaterra, de 1887 a 1918, e líder sionista), acreditavam que havia uma estrela de seis pontas gravada nas moedas cunhadas na época de Bar Kochba.

Ainda no Talmud (Gittin 68a) esta escrito que o rei Salomão possuía um anel no qual estava gravado o “Nome Divino de 72 Letras“ e que este anel o protegia contra as forças negativas. Porém, mais uma vez não é dada nenhuma descrição adicional. Muitas vezes o pentagrama – a estrela de 5 pontas – chamado de “Selo de Salomão”, termo usado tanto no Islã como em algumas comunidades judaicas, era usado no lugar do Maguen David. A estrela de cinco pontas também era considerada um símbolo de proteção Divina, mas no meio judaico seu uso acabou sendo abandonado.

O mais antigo artefato judaico com um hexagrama de que se tem notícia é um selo encontrado em Sidon, datado do século VII antes da era comum. Apesar de, na época do Segundo Templo, os s��mbolos judaicos mais comuns serem o shofar, o lulav e a menorá, foram encontrados pentagramas e hexagramas em vários achados arqueológicos. Um exemplo é o friso da sinagoga de Cafarnaum (século II ou III da era comum) e uma lápide (ano 300 da era comum), encontrada no sul da Itália.

Idade Média

O uso ornamental de estrelas tanto de cinco como de seis pontas estendeu-se durante a Idade Média aos países muçulmanos e cristãos. Entre os muçulmanos o uso do “Selo de Salomão”, como proteção, era muito difundido. Alguns reis, como o de Navarra, usavam a estrela de seis pontas em seu selo. O hexagrama é encontrado em igrejas e catedrais, assim como em sinagogas, como a de Hameln (Alemanha, 1280) e a de Budweis (Boêmia, século XIV). Iluminuras de manuscritos hebraicos medievais contêm hexagramas sem que lhes sejam atribuídos qualquer nome.

O mais antigo texto que faz menção ao Maguen David como o escudo protetor usado pelo Rei David pode ser encontrado em um alfabeto místico que remonta ao período gueônico e era utilizado pelos sábios asquenazitas do século XII. Mas, neste caso, acreditava-se que o que estava gravado no escudo era o Grande Nome Sagrado de 72 letras. O termo Maguen David ainda não estava ligado à estrela de seis pontas e não está claro o que teria provocado a substituição do “Grande Nome de 72 letras” pela figura geométrica. Depois desta época, o uso do Maguen David tornou-se difundido em manuscritos medievais como proteção.

Também são da Idade Média os primeiros amuletos de proteção em que aparece o hexagrama. Entre os séculos X e XIV, são encontrados em mezuzot.

Mas até o século XII, o termo Maguen David não tinha ainda um vínculo com a estrela de seis pontas, já que havia várias hipóteses sobre o que estava gravado no escudo que o rei David usava nas batalhas. Por exemplo, segundo a obra de Rabi Isaac Arama, Akedat Itzhak (século XV), o que estava gravado no escudo do rei era o Salmo 67 disposto em forma de menorá.

Mas é no texto cabalístico Sefer ha-Guevul, de autoria de um neto de Nachmânides, do início do século XIV, que podemos encontrar o mais antigo testemunho do uso do termo em relação à estrela de seis pontas. O hexagrama aparece duas vezes nesse texto, sendo chamado em ambas de Maguen David.

Já a partir do século XIII, na Espanha e na Alemanha, são encontrados manuscritos bíblicos nos quais partes da messorá – tradição oral - são escritas em micrografia, em forma de hexagrama. E até o século XVI, os sábios cabalistas acreditavam que o Escudo de David não deveria ser desenhado com simples linhas geométricas. Deveria ser composto com determinados Nomes Sagrados e suas combinações, segundo o padrão dos manuscritos bíblicos, nos quais as linhas eram compostas com textos da messorá.

O uso oficial

Foi no século XIV, em Praga, capital da Boêmia, que o Escudo de David foi usado pela primeira vez de forma oficial para representar uma comunidade judaica. No ano 1354, o rei Karel IV concedeu à comunidade judaica o privilégio de ter sua própria bandeira. No fundo vermelho, foi colocado o hexagrama, a Estrela de David, em ouro. Documentos referem-se a este símbolo como sendo a “bandeira do rei David“. Em Praga, a estrela de seis pontas – sempre chamada de Maguen David – passou a ser usada tanto em sinagogas, como no selo oficial da comunidade e em livros impressos.

O símbolo logo se difundiu e, a partir do século XVII, tornou-se o emblema oficial de várias comunidades judaicas e do judaísmo em geral. Em Viena, em 1656, foi usado em uma pedra que marcava o limite entre os bairros judeus e cristãos, junto com uma cruz. Ao serem expulsos de Viena, os judeus levaram o símbolo para outras localidades para onde se transferiram, a Morávia e Amsterdã. Em 1799, a Estrela de David foi usada para representar o povo judeu em uma gravura anti-semita. Em 1822, ao ser agraciada com um título de nobreza pelo imperador austríaco, a família Rothschild a usou em seu brasão.

Foi considerada, assim, um símbolo especificamente judaico no decorrer dos séculos XVIII e XIX na Europa Central e Oriental, espalhando-se pelas comunidades judaicas da Europa Ocidental e do Oriente Médio. Quase todas as sinagogas exibiam a Estrela de David, algumas em sua fachada; outras instituições, como as sociedades beneficentes, usavam o símbolo em seus documentos. Segundo um dos grandes rabinos deste século, o Rabi Moshe Feinstein, o rei David usava o Maguen David, o símbolo de seis pontas, para que o Todo- Poderoso o protegesse nas batalhas. O movimento sionista a adotou como emblema de sua bandeira e do primeiro número do periódico sionista de Theodor Herzl, Die Welt. Os fundadores de Rishon L’Tzion também a colocaram em sua bandeira, em 1855. A Estrela de David tornara-se o símbolo de novas esperanças e de um novo futuro para o povo de Israel.

Mas foram os nazistas que lhe conferiram uma nova dimensão. Em 1933, Hitler, ao decidir que os judeus deveriam usar uma marca em suas roupas para que pudessem ser facilmente reconhecidos, escolheu a “Estrela Judaica” – como era chamado, em tom pejorativo pelos nazistas, o Maguen David. Ao querer fazer deste um distintivo da vergonha que acompanharia milhões em seu caminho para a morte, tornou-o símbolo de um povo. Símbolo de sofrimento e morte, mas também de esperança.

Quando o Estado de Israel escolheu como emblema do novo Estado judaico a menorá, manteve o Maguen David na bandeira nacional. Atualmente, a Estrela de David é o símbolo de uma nação independente. É o símbolo de um lar nacional para todo e qualquer judeu.

אני כבר אמרתי את שמי : " נ נח " !

נ נח נחמ נחמן מאומן

פתק

0 notes

Photo

Parochet from Venice, Italy, 1676/5436.

108 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Oriental Rug Cleaning in Millburn

Oriental rugs are highly valued items. From the Jewish parochets to the Christian altar covers, these rugs hold a significant cultural value. For most people they are an integral part of their traditions, while for others they are essential in-house decor.

As these rugs are heavily woven; they carry more weight than normal. It means that the stains they bear are tougher to remove. It is impossible to wash them by hand and may cause discoloration if anyone attempts to do so. EZ Rug Cleaners recognize the significance of oriental rugs in the community of Millburn and utilize their knowledge and experience to safeguard their cultural artifacts.

Area Rug Cleaning in Millburn

Area rugs are a favorite when it comes to living rooms. They act as artwork for the floor and are a colorful addition to any room. Due to their expansive size, they are sprawled across wall to wall and used to decorate the floor as extensively as possible. So, they fall victim to accidental spills, wear and tear from furniture, and assaults from unruly pets. Repairing area rugs can be burdensome as it requires a lot of effort and time. EZ Rug Cleaners come to the aid again and offer cleaning, washing and repairing area rugs in Millburn.

Cleaning rugs is a tedious and time-taking job and if not done right, can damage the rugs permanently. EZ Rug Cleaners should be consulted for their advanced procedures and their extensive experience to remove all kinds of stains.

EZ Rug Cleaners offers rug cleaning, carpet cleaning and upholstery cleaning services in Millburn and throughout the whole New Jersey state. Give us a call at 973-315-3096 to get an instant quote.

0 notes

Text

Best Designer Flooring For Home Decor And Its Types

Carpets oriental:

The Oriental carpet has long occupied a central place in many homes, and Persian carpets are often thought to be the most beautiful of all. With their fascinating patterns, these unique carpets have enchanted many people over the years, and it’s easy to understand why. The variations are endless and the craftsmanship behind them is superb, making these carpets a focal point for your home.

Oriental carpets can be pile woven or flat woven without pile, using various materials such as silk, wool, and cotton. Examples range in size from pillow to large, room-sized carpets, and include carrier bags, floor coverings, decorations for animals, Islamic prayer rugs(sajjadah), Jewish Torah ark covers (parochet), and Christian altar covers. Since the High Middle Ages, oriental rugs have been an integral part of their cultures of origin, as well as of the European and, later on, the North American culture.

Maroon Silk Wool Carpet:

A small handcrafted piece of art is at the display for you. A splendid array of shades to add a touch of ethnic art to your living space! Warm beautiful shades that will enhance the decorative look of your home. About the Craft Carpet weaving was introduced in Kashmir by King Budshah in the late 15th century.

It is believed that he brought master artisans from Persia to improvise over the spinning and weaving capabilities of artisans, thus introducing the beautiful carpet weaving into the traditional arts of Kashmir. A hand-knotted carpet is perhaps the most coveted and treasured textile sough all over the world. Carpet making in Kashmir is pure art and the quality depends upon the number of knots used in its making. The process of wrapping yarn around the warp to form a pile is known as knotting.

Silk Carpet:

Manufacturing Process: The process begins at the conceptualization of the pattern/design and is undertaken by naqash (Designer), the pattern is first drawn in free hand and later on approval by the manufacturer the pattern is then painted on a tracing paper, where each pixel detonates a color. Then the color schemes are designed in consultation with the merchandizer, they choose between a range of 10 to 30 hues/colors depending on the intricacy and the pattern. This design trace is then forwarded to the taleem-naqash who codifies a script in symbols, wherein each symbol signifies a color.

The whole pattern is then translated in a carpet manuscript. The (Kalbaf) weaver is provided the yarns and dyed silks as per requirement and the carpet manuscript. At times he is not privy to a new design and starts weaving the rug to its completion. Typically a silk carpet of 9’ x 12’ (324 KPSI) takes anywhere between 1 year to weave How to Clean Weekly vacuum cleaning for high activity area. Professional oriental carpet cleaning once in 5 years or when the rug appears dull or dirty. History:The history Kashmir carpet culmination of artistic magnificence -date back to the period of Hazrat Mir Syed Ali Hamdani (r.a.) 1341-1385 A.D. - the famous Sufi saint of Persia who came to enlighten Kashmir with his spiritual guidance and brought along highly skilled artisans through the silk trade route and laid base for the cottage industries in Kashmir valley.

Click here to know more about wall hanging

Black Ardabil Silk Carpet:

The royalty in shades, the classic black plays home to the autumnal hues of Kashmir in this beautiful Silk carpet. Inspired by the beauty of Kashmir, this one piece will enhance the grandeur of your classy home. A luxurious carpet styled to bring out the best of your tastes into the limelight! About the Craft Carpet weaving was introduced in Kashmir by King Budshah in the late 15th century. It is believed that he brought master artisans from Persia to improvise over the spinning and weaving capabilities of artisans, thus introducing the beautiful carpet weaving into the traditional arts of Kashmir. A hand-knotted carpet is perhaps the most coveted and treasured textile sough all over the world. Carpet making in Kashmir is pure art and the quality depends upon the number of knots used in its making.

Click here to buy hand made wall hanging

Rug and Wall Hanging:

Rug and carpet, any decorative textile normally made of a thick material and now usually intended as a floor covering. Until the 19th century the word carpet was used for any cover, such as a table cover or wall hanging; since the introduction of machine-made products, however, it has been used almost exclusively for a floor covering. Both in Great Britain and in the United States the word rug is often used for a partial floor covering as distinguished from carpet, which frequently is tacked down to the floor and usually covers it wall-to-wall. In reference to handmade carpets, however, the names rug and carpet are used interchangeably.

Handmade carpets are works of art as well as functional objects. Indeed, many Oriental carpets have reached such heights of artistic expression that they have been held in the same regard in the East as objects of exceptional beauty and luxury that masterpieces of painting have been in the West.

Visit us to Buy online Carpets

Blue Brown Cotton Wall Tapestry:

Tapestry was born in France in the 17th century when Louis - the 14th set a royal tapestry loom to give rise to traditional art in the same period. Back then large looms, a thousand men, and years together marked the making of even a small sized tapestry whose completion would be a celebration. In order to revive and sustain this dying craft, here is our endeavor into this realm with a cotton based tapestry over the base of which colorful woolen threads create magical wefts in cross-ply work. What is born is a masterpiece for your walls which adds more definition to your interior themes.

Circular Patterned Handmade Rug:

A stunning handmade rug in the chain stitch pattern, in two astounding colors of dark and light, is what we picked up for you to adorn your lovely homes. The ends are done in the deep red, maroons’ shade, which hosts the circle of life in a golden vinery pattern. Between these symphonic ends lies a lighter shade of off-white, which has a beautifully done pattern in deep shade of blue with contrasting patterns in its lighter component. The subtle hint of green amongst the deep blue patterns lends a subtle hint of contrasting shades. This rug can be used on the bedside or on the bed foot, the choice is yours. You also can use this rug as a wall hanging to liven up the walls of your lovely home.

Click here to buy Kashmiri Rugs

#wall hanging#hand made wall hanging#Buy online Carpets#Kashmiri Rugs#rugs online#handmade wall hanging

0 notes

Text

Diary Entry#2

"Don't you know that your body is the temple of the Holy Spirit, who lives in you and who was given to you by God? You do not belong to yourselves but to God;"

Oh how great it is to be loved! How joyous it is to receive God's very essence through the vessel of another! Today I received an email from the Secular Franciscans stating: "The different responses I have received about our transgender sisters and brothers tells me that the approach would be similar to those of same-sex attraction, which is that we welcome you with open arms as our sisters and brothers in Christ." How wonderful, I can be allowed into Franciscan fraternity! Though I earlier thought Carmelite life was for me, it simply wasn't the Master's will; I feel like how Saint Ignatius of Loyola must have felt when his pilgrimage to the Holy Land was rejected, meaning that he was to put the Jesuit Order at the service of the Pope. I bless the Lord for revealing his plan to me! I think that on this occasion I should give a commentary on Franciscan Spirituality as I understand it, specifically the Incarnation. The parochet was a veil that separated Man from God in the Temple; for only the High Priest was worthy of seeing the Holy of Holies (and when they weren't, they were struck down), but by Christ's sacrifice, the veil has been torn down! Christ's atonement put humanity on a MUCH higher level, one that is quite literally impossible to attain on our own. As a baseline, the worst sinner is still worthy of being the Holy Spirit's dwelling place, because our sin can never be great enough to defeat Christ. Through his sorrowful passion and neverending mercy, we have been saved. But there is more to being a Christian than just making it to heaven. As Christ teaches us: "Not everyone who calls me ‘Lord, Lord’ will enter the Kingdom of heaven, but only those who do what my Father in heaven wants them to do." But how can we do what God wants us to do? We humans are flawed and imperfect, subject to sin and error. How can we do the good works God wants of us? Through the Holy Spirit. As our faith grows, the Spirit grows within us, for Christ says: "I am telling you the truth: those who believe in me will do what I do — yes, they will do even greater things, because I am going to the Father." Jesus goes to the Father so that we might obtain his Holy Spirit, the third person of the Holy Trinity. Which brings us back to the Incarnation. The Incarnation, also known as the Annunciation, is when the Angel Gabriel announced to Mary that she would conceive Jesus, and by her "yes", it was done. Mary is the greatest follower of God's will, as said by Saint Alphonsus de Liguori, and she is the model for all disciples. Just as Christ dwelt within Mary, the Holy Spirit dwells within us, and just as Christ turned water into wine because of Mary, God will do many miracles through us! The Incarnation is simultaneously God lowering himself to a flesh body, subjecting himself to pain and suffering and torture, humbling himself to a servant, and also him preparing each and every one of us to serve him, enact his Holy Will, and enter the Kingdom of Heaven.

0 notes

Text

Wedding Bells

There are many areas of Jewish life in which popular custom adds dramatically to what would just be required by the letter of the law…but the inverse situation also exists in which practices that are theoretically requisite have summarily dropped out of use so totally that they have been mostly (or totally) forgotten by almost all. The procedures involving the death and burial of loved ones stand out as an excellent example of custom deviating from law in countless different ways, but—slightly surprisingly—so do the procedures that govern the maintenance of a strictly kosher kitchen. Synagogue life itself is in that category as well: there are many parts of the standard synagogue service that feel requisite but aren’t actually, yet there are just as many once-standard parts of the worship service that have simply fallen away, barely remembered, let alone seriously missed, by anyone at all.

But I have weddings on my mind this week—my oldest son is getting married to his lovely fiancée next Saturday night—and so I thought I would apply that thought to the customs and traditions that surround the Jewish wedding ceremony and write this week about some of the specific ways what we today find totally familiar and ordinary is not at all what felt that way to earlier generations.

First, let’s talk about the bride’s outfit. There is no legal requirement that the bride dress in any specific way at all! But the familiar white dress, usually incorrectly taken by moderns as a subtle reference to pre-marital chastity, does have a long history and is part of the complex of customs related to the notion that the day of a couple’s wedding is a kind of private Yom Kippur for them alone. It’s a nice idea too, that just as Yom Kippur is a day of atonement and reconciliation, so are all past missteps and errors of judgment both of bride and groom forgiven and forgotten on their wedding day. The old custom, now rarely observed, of brides and grooms fasting on their wedding day is part of the same complex of ideas relating the day of a wedding to Yom Kippur. As also is the old—and now entirely forgotten—custom of brides specifically having their hair braided before the chuppah, which was once intended to bring to mind the old story about God braiding Eve’s hair before bringing her to Adam and to make the simple point that, just as Eve—who, having just been created, obviously had nothing in her non-existent past to atone for—that every bride is an Eve starting life afresh on the day of her wedding.

The veil, on the other hand, actually was intended as a sign of modesty. And that is why the custom lives on: because there is something charming about the bride choosing to veil her face on the very day that she hears over and over how beautiful and attractive she is, thus signaling her understanding that true beauty resides within, that comeliness is a function of virtue rather than mere appearance.

The badecken ceremony, also nonrequisite legally, is only one version of an old custom. There were always places in which it was traditional for the groom to veil the bride as we do today, but there were also Jewish communities in which the custom was for the rabbi performing the ceremony to veil the bride, whereupon the assembled would signal their approval by throwing things at her and the groom: either seeds or wheat kernels, both meant to be suggestive of the community’s prayer that the newlyweds have children easily and quickly. (Wheat was thought of as a plant that grows where it is sown effortlessly and almost always successfully. Whether that is true, I have no idea.) The custom involving kernels of wheat is described in an old book by Rabbi Yaakov Halevi Molin, who lived in Germany at the end of the fourteenth century, in the following way: “The custom is for the assembled to bring the groom to the bride, whereupon the groom takes the bride’s hands in his own, and as they clasp hands the wedding guests shower them with kernels of wheat and call out three times, ‘Be ye fruitful and multiply.’”

The custom of the bride offering the groom the gift of a new tallit has mostly fallen away, but when it was still a feature of Jewish life, the point was that, because there are thirty-two cords that hang from the tallit and the way to write “thirty-two” in Hebrew shorthand is a homograph with the word lev (“heart”), offering the groom a tallit was a way of the bride offering the groom her heart on their wedding day.

The custom of giving gifts to the couple is also very old. In some place, the custom was for the groom to deliver an address on the morning of his aufruf —this was long before brides were routinely also called forward to the Torah on the Shabbat before the wedding—and gifts were then offered as some sort of compensation for the effort of preparing the address. In other places, though, the custom was more like our own and gifts were brought to the wedding itself and presented to the bride and groom formally as they sat together at the head table, the bride always to the right of the groom, just as she stood to his right under the chuppah. (The bride, you see, is always right!)

And that brings me to the chuppah itself, which has its own complicated history. Not precisely legally requisite, yet universally present at Jewish weddings, the chuppah wasn’t a wedding canopy at all in its earliest iteration, just a kind of nuptial tent set up near where the wedding was to take place to which the bride and groom were sent to seclude themselves following the ceremony. (The seclusion part, called yichud, on the other hand actually is requisite.) It was only in medieval times, in fact, that things changed and the chuppah we know came into use, the kind consisting of a piece of gorgeously embroidered cloth held up by four poles. (There was also the custom of using the parochet—the curtain that hangs in front of the Ark of the Law in any synagogue—as the top of the chuppah as a way of signaling the community’s hope that the new union be blessed by God.) The chuppah was most customarily set up outdoors in the synagogue courtyard so that the wedding could take place in the open air, a custom still observed in our day at least by some, and was taken in its own way to constitute a prayer that the couple’s progeny be, at least eventually, as numerous as the stars in the nighttime sky. Even the orientation of the chuppah mattered: just as at Shelter Rock, the chuppah was traditionally oriented towards the east, towards Jerusalem, as a way of suggesting that the couple’s willingness to enter into matrimony and create a family is itself an act of worship.

The parts of the ceremony that are neither legal nor liturgical are pretty much all dictated by custom rather than by law. The custom of the processional, for example, is our latter-day echo of the older custom of the assembled all escorting the groom and the bride to the chuppah, a custom that is the norm today in Israel. (The point of this was to make it impossible for a couple to get married casually since they could obviously not escort each other to the chuppah. In turn, this forced a couple to think twice before marrying, which line of reasoning accords in New York State with the detail that wedding licenses are invalid in New York State for the first twenty-four hours after they’re issued, thus requiring couples to sleep on their decision at least once before actually tying the knot. In my opinion, this is a very reasonable concept indeed!)

In ancient times the bridesmaids gathered to support the bride for the pre-game show, but it was the groomsmen who had the honor of escorting the bride some number of times around the groom before the ceremony could begin. (The oldest texts talk about three circuits, but in our world the number is almost universally seven. And although the circling itself survived, today it’s almost invariably the bride’s mother who accompanies the bride on her seven circuits.) The circling is an ancient custom, not a legal requirement, and has many different interpretations. For me personally, the circling serves as a kind of corrective to the androcentricity of the liturgy: it may be the groom who formally marries the bride and who thus draws her into his sphere of existence, but the seven circuits can be imagined to serve as a prominent reminder of the fact that marriage is a two-way street…and that marriage draws the groom into his bride’s sphere of existence just as surely as it draws her into his.

There are lots more customs and ceremonies to consider, but these are the ones on my mind this week. Weddings are magic moments for all concerned, particularly (although I wouldn’t have understood this when I was a groom myself) for the parents of the couple, who see their own lives made whole by the willingness of their children to accept the burdens of adulthood, to step into the romance of married life, and to create homes based on mutual respect, affection, and love. Really, what more could any parent want?

0 notes