#other sopranos in Puccini’s operas are also more interesting

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

This might be an unpopular opinion, but I really can’t stand Mimi. Musetta is a far better part to sing.

#Quando me’n vo’ is just an amazing aria#and Mimi’s part is quite boring#other sopranos in Puccini’s operas are also more interesting#Tosca or Butterfly for example#opera#Puccini#Giacomo Puccini#La Bohème#La Boheme#soprano

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Opera anon here - I'm so pleased you looked up Jessye!! She's probably my favorite soprano and was just such an incredible figure in opera for so long.

In the interest of spreading even more weird opera stuff in case it's even remotely interesting to the Loustat folks that frequent your blog - sticking with Puccini I also think it would be hilarious for Louis and Lestat to see a production of La Fanciulla Del West. It premiered at the Met ~1910 and it's straight up a spaghetti western. It is the most ridiculous thing to watch and it's wonderful. Act 1 opens up with a bunch of coal miners (sometimes dressed as cowboys??) singing "Hello" in English for the first 5-7 minutes just because. The whole thing is an inadvertent comic masterpiece.

It's also like, an interesting one musically for Lestat because Puccini is so well regarded but La Fanciulla was through-composed (something Puccini didn't do) and I feel so passionately that Lestat would HATE it haha. Like, this is a man who lives for those big heartstopping arias and La Fanciulla goes against most of what he probably thinks opera should be (at least at that time). But on the other hand, I can so easily see Louis being taken in by the actual artistry of the music and story (it's genuinely such a good piece but at the time it was more considered a crowd-pleaser with little redeeming musical value and was critically panned which is wild to think about now. Today it's recognized as an incredible piece of composition.)

Also, not that it super matters but I tend to think of Lestat's enjoyment of Don Pasquale (the opera he and Louis see in 1.02) as being at least partially related to the light orchestration and focus on vocal dexterity which is...not what's happening in a lot of then-modern operas like La Fanciulla.

And sorry this got so long! Feel free not to publish/answer it. It's just so rare that characters are canonically into opera I get swept away thinking about all the productions Lestat and Louis might have seen (or will see in the future because I refuse to believe they never go to the opera together again).

(x)

Anon, don't apologise, I loved reading this so much. It's so great to have characters that are just so fully realised on a show like this because it really does mean there are so many layers to their personalities and interests that are going to resonate with different people.

That whole situation with La Fanciulla Del West is sooo interesting too, I love hearing about productions that flop on release but are really recontextualised by time. That sounds like both such a fun and fascinating one too.

#i loooove these elements of different forms of live performance being woven into the show#(also to the anon who sent me that ask for fringe show recs the other day i'm going to try and answer today! the flash sale's on in two day#so hopefully you can earmark some for the sale too :-) )#theatre asks#iwtv asks

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Franco Zeffirelli dies at 96

Franco Zeffirelli, the Italian director and designer who reigned in theater, film and opera as the unrivaled master of grandeur, orchestrating the youthful 1968 movie version of “Romeo and Juliet” and transporting operagoers to Parisian rooftops and the pyramids of Egypt in productions widely regarded as classics, died June 15 at his home in Rome. He was 96.

A son, Luciano, confirmed the death to the Associated Press but did not cite a cause.

Mr. Zeffirelli — a self-proclaimed “flag-bearer of the crusade against boredom, bad taste and stupidity in the theater” — was a defining presence in the arts since the 1950s. In his view, less was not more. “More is fine,” a collaborator recalled Mr. Zeffirelli saying, and as a set designer, he delivered more gilt, more brocade and more grandiosity than many theater patrons expected to find on a single stage.

“A spectacle,” Mr. Zeffirelli once told the New York Times, “is a good investment.”

From his earliest days, he seemed to belong to the opera. Born in Italy to a married woman and her lover, he received neither parent’s surname. His mother dubbed him “Zeffiretti,” an Italian word that means “little breezes” and that arises in Mozart’s opera “Idomeneo,” in the aria “Zeffiretti lusinghieri.” An official mistakenly recorded the name as “Zeffirelli.”

Mr. Zeffirelli grew up mainly in Florence, amid the city’s Renaissance riches, and trained as an artist before being pulled into theater and then film by an early and influential mentor, Luchino Visconti. Mr. Zeffirelli matured into a sought-after director in his own right, staging works in Milan, London and New York City, where he became a mainstay of the Metropolitan Opera.

His first major work as a film director was “The Taming of the Shrew” (1967), a screen adaptation of Shakespeare’s comedy, starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. But Mr. Zeffirelli was best known for the Shakespearean adaptation released the next year — “Romeo and Juliet,” starring Leonard Whiting and Olivia Hussey in the title roles.

He reportedly reviewed the work of hundreds of young actors before selecting his two stars, both of whom were still in their teens. With a lush soundtrack by Nino Rota, and with its equally lush visuals, the film won the Academy Award for best cinematography and was a runaway box office success. Film critic Roger Ebert declared it “the most exciting film of Shakespeare ever made.”

It “is the first production of ‘Romeo and Juliet’ I am familiar with in which the romance is taken seriously,” Ebert wrote. “Always before, we have had actors in their 20s or 30s or even older, reciting Shakespeare’s speeches to each other as if it were the words that mattered. They do not, as anyone who has proposed marriage will agree.”

In the opera, an art form already known for its opulence, big voices and bigger personalities, Mr. Zeffirelli permitted himself to be deterred by neither physical nor financial constraints. “Opera audiences demand the spectacular,” he told the Times.

Mr. Zeffirelli had notable artistic relationships with two of the most celebrated sopranos of the 20th century, Maria Callas and Joan Sutherland. But certain Zeffirelli sets seemed to excite the opera world even more than the performers who sang upon them.

One such example was his production of Puccini’s “La Boheme,” an extravaganza set in 19th-century Paris and famous for its exuberant street scene and magical snowfall. After its 1981 premiere at the Met, it was said that the audience lavished on Mr. Zeffirelli a grander ovation than the one reserved for conductor James Levine and the singers who played the opera’s bohemian lovers.

“For the first time,” Mr. Zeffirelli told the Times, “audiences will have a sense of the immensity of Paris, and the smallness of this little group’s place — the actual space of a garret. The acting is now intimate and conversational, which is exactly what Puccini wanted. Since the garret is raised, every whisper and gesture will come across clearly in the theater.”

His production of Verdi’s “Aida,” performed at Milan’s La Scala in 1963 with soprano Leontyne Price and tenor Carlo Bergonzi, featured 600 singers and dancers (including scantily clad belly dancers), 10 horses, towering idols, palm trees and sphinxes littering the expanse of the stage. “I have tried to give the public the best that Cecil B. DeMille could offer,” Mr. Zeffirelli told Time magazine, referring to the Hollywood director’s biblical epics, “but in good taste.”

It was sometimes said that Mr. Zeffirelli was beloved by everyone except music reviewers, some of whom disparaged his style as excessive to the point of taking attention away from the music. Writing in the Times, Bernard Holland panned Mr. Zeffirelli’s set for Puccini’s “Turandot,” set in China, as “acres of white paint and gold leaf topped by the gaudiest of pagodas” and quipped that “if the gods eat dim sum, they certainly do it in a place like this.”

In time, the Metropolitan Opera replaced some of Mr. Zeffirelli’s productions, although the modernistic newcomers — notably Luc Bondy’s dreary “Tosca” in 2009 — did not always prove as popular.

“It’s like somebody decides that the Sistine Chapel is out of fashion,” Mr. Zeffirelli told the Times. “They go there and make something a la Warhol. . . . You don’t like it? O.K., fine, but let’s have it for future generations.”

As for those who had criticized his direction of “Romeo and Juliet” for similar reasons, he retorted, “In all honesty, I don’t believe that millions of young people throughout the world wept over my film ... just because the costumes were splendid.”

Mr. Zeffirelli was born in Florence on Feb. 12, 1923. His father, Ottorino Corsi, was a Florentine businessman, and his mother, Alaide Garosi, was a fashion designer. Her husband was a lawyer, and he died before Mr. Zeffirelli was born.

His mother continued a fraught relationship with Corsi, once attempting to stab him with a hat pin. “The opera? My destiny?” Mr. Zeffirelli observed in a 1986 autobiography, “Zeffirelli.” “I think there is a case to be made.”

After the death of his mother when he was 6, he became the charge of an aunt. He recalled his upbringing in the 1930s in the semi-autobiographical film “Tea With Mussolini” (1999), which he directed and which starred Maggie Smith, Judi Dench and Joan Plowright as English expatriates in Florence who take in a parentless child during the era of fascist rule.

Mr. Zeffirelli attended art school before studying architecture at the University of Florence. His studies were put on hold during World War II, when he fought alongside antifascist partisans. His interests shifted more toward film, particularly after he saw Laurence Olivier star in the 1944 Technicolor film adaptation of Shakespeare’s “Henry V,” which Olivier also directed.

“The lights went down and that glorious film began,” Mr. Zeffirelli recalled in his memoir. “I knew then what I was going to do. Architecture was not for me; it had to be the stage.”

He met Visconti while working in Florence as a stagehand. Visconti, with whom he lived for a period, gave him his push into professional work, hiring him to work as a designer for an Italian stage production of Tennessee Williams’s “A Streetcar Named Desire” in 1949.

Mr. Zeffirelli soon began designing and directing at La Scala and later the Met. He designed, directed and adapted from Shakespeare the libretto for the production of Samuel Barber’s “Antony and Cleopatra” that opened the Met’s new opera house at Lincoln Center in 1966.

Mr. Zeffirelli said he found it invigorating to shift from one art form to another. His theatrical productions starred top-flight actors including Albert Finney and Anna Magnani. On television, he directed “Jesus of Nazareth,” an acclaimed 1977 miniseries with a reported price tag of $18 million and a cast that included Robert Powell as Jesus, Hussey as the Virgin Mary, Olivier as Nicodemus, Anne Bancroft as Mary Magdalene and James Earl Jones as Balthazar.

Mr. Zeffirelli received a best director Oscar nomination for “Romeo and Juliet.” (He lost to Carol Reed for the musical “Oliver!”) He also garnered a nomination for best art direction for his 1982 film adaptation of Verdi’s opera “La Traviata,” starring Teresa Stratas and Plácido Domingo, one of several such operatic film adaptations he made.

His other notable films included “Hamlet” (1990) starring Mel Gibson and Glenn Close. Less acclaimed was “Endless Love” (1981), starring Brooke Shields and Martin Hewitt in a tragic story of teen romance, which Mr. Zeffirelli admitted was “wretched.”

Politically, Mr. Zeffirelli positioned himself on the right, serving as a senator in the political party Forza Italia. “I have found it an irritating irony that those who espouse populist political views often want art to be ‘difficult,’ ” he wrote in his memoir. “Yet I, who favor the Right in our democracy, believe passionately in a broad culture made accessible to as many as possible.”

He described himself as homosexual, preferring not to use the word “gay.” In 2000, he adopted two adult sons, Pippo and Luciano, both former lovers, according to the newspaper the Australian. A complete list of survivors was not immediately available.

Looking back on his life and career, Mr. Zeffirelli once told The Washington Post that he was struck by “how much is risked to become something” — “to make something of his life,” he continued, speaking of himself in the third person. To show that “he’s not a bastard.”

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

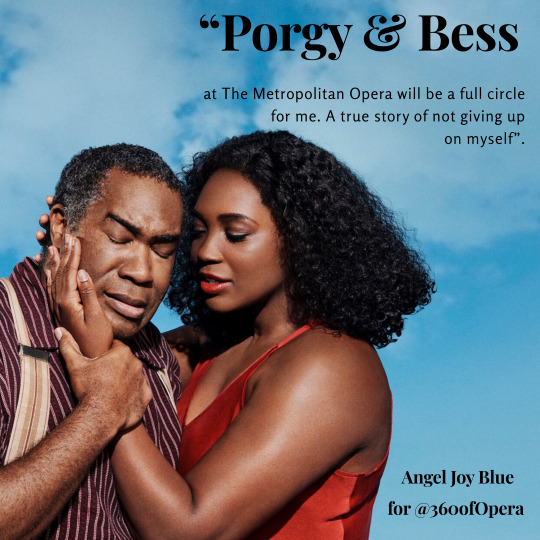

ANGEL JOY BLUE

A couple of weeks ago, I had the pleasure of talking to American soprano Angel Joy Blue on the phone, in between her performances of Mimì in La Bohème at Canadian Opera Company in Toronto. At the time of our talk, she was in a practice room working on one of her future roles, Tosca, also by Puccini. Never a dull moment, folks! I had already been following Angel’s career for a while of course, but during this run of La Bohème she went live on her Facebook channel and it was so genuine and inspiring that I felt the urge to communicate with her, understand where this was coming from and share it with all of you!

Click Here to Watch Video!

360 of Opera: What inspired this video? You truly touched a lot of people with it, especially young singers working hard towards a career in opera.

I’m so happy to hear that! There’s so much going on in the world at the moment. I’m pretty sure that was the day Notre Dame was in flames. I’m a pastor’s kid, I grew up in the church and I was really touched by what happened in Paris. This great monument that was burning, watching it being engulfed in flames, watch it go down like in a movie, it was very disturbing. That, coupled with the fact that it was opening night and there is so much going on in general in my personal life. I’ve been studying new roles and I’ve had quite a few people say very negative things to me. In our profession, the first job is to learn the music, and then there is all this other stuff, but ultimately we are supposed to be able to sing what is on the page. I was thinking about everything that I have coming up and all these opinions that I wanted to get out of my head. I also thought it was my 50th performance of La Bohème, which it was, but I guess I was including dress rehearsals and student matinees and one of my friends told me I’m not supposed to include dress rehearsals!

You know, ten years ago when I was a young artist, I wasn’t able to sing Mimì’s arias and I had a lot of comments about my low voice and my middle voice: “You can’t do this, you can’t do that. You’re not going to be Mimì, you’re too tall, you don’t look fit…”

I like to turn off the lights of my dressing room before I go on and sing. I do that every show and I just sit there. And this time I had this overwhelming feeling of: “Angel you get to sing these roles because you didn’t listen to all that stuff. You didn’t listen to what people were saying to you” and I was overcome with a really big feeling of gratitude and thankfulness just to be able to have a job. Maybe some years ago I was not able to sing some of these roles but I still worked on them diligently. That’s the reason I put that video out there, because I knew that someone out there would need that. I feel like in opera we’re always told what we’re not supposed to do. It comes down to what YOU want to do, it’s your voice.

360 Of Opera: You are now singing roles that you were not able to sing 10 years ago. This concept of maintaining a big picture mindset is hard for young singers. How was it for you?

I always had it in my mind. My sister is a clinical psychologist. I had a concert a couple of years ago and I noticed that my voice really changed around 2013. I was telling her how it felt weird and it was out of control. I felt like I was out of control. She said: “you’re not telling me that you don’t think you can sing, all this stuff that you’re saying is psychological.” I was constantly doubting everything. I was really beating myself up for every single thing I did. And my sister said: “Number one, you need to celebrate your successes, number two, give yourself permission to be successful.” And when she said that it really hit me! Whatever success means to you. For me it doesn’t mean that I’m getting to sing at all of these houses, that is a form of success for sure, but at that time what it meant specifically was for me to be able to appreciate and enjoy my talent.

Everybody has an opinion, that’s what people do. It’s a battle, but since then, I’ve really tried to stay in this positive mindset and be excited about my talent and what I can do, be thankful for my talent. My message to young singers is to not let other people decide how you feel about your own voice. That would be weird! I’m constantly working on myself, but it is important to have a very strong opinion about your voice and to find things about your voice that you love.

360 of Opera: You have an exciting year ahead, especially with ‘Porgy and Bess’ at The Metropolitan Opera, which will open the 2019/2020 season. What does this mean for you?

The historical value of it is what makes it special for me. It’s also a full circle for me because my first professional opera role after being a young artist was Clara in ‘Porgy and Bess’ in 2009. Back then, I never would have thought that in 10 years I would be singing Bess and opening the Met Opera season with it! It’s interesting because Eric Owens was also in that production. For me it’s a true story of not giving up on myself. It’s hard to do, this is not an easy career. Once you get in it, it’s full of highs and as high as you can go, you can get as low.

I’m really thankful for this opportunity. I think the opera hasn’t been performed in 25 or 30 years at the Met so I feel really blessed to be a part of the cast that is bringing it back to that stage. I think it’s going to be a very big success and I’m very happy that they decided to call me for it! They believe that I can do it and it’s a wonderful thing to be able to perform this American opera. I’m a very proud American, I love my country and it means a lot to bring this great American opera back where it all began.

360 of Opera: Talking about American opera, what are your thoughts on new compositions? Is there any contemporary American opera in your future?

I love it, I thinks it’s great. Especially composers like Jake Heggie and also Bruce Adolphe who has some beautiful song cycles. It’s amazing, Jake Heggie is one of my go-to composers whenever I do recitals. I would hope to be a part of new projects, operas or song cycles that have yet to be written.

You know, I’ve been to 41 countries. I made it to 30 in 6 years. For politicians it’s nothing but for me that was random and very unexpected. I’m so happy I had the opportunity to travel and see what music is for other cultures. When I came home, I was very happy to confirm that we have a big classical music culture. We’re so far geographically from a lot of the European classical music scene. But I think we don’t give ourselves enough credit for having a rich culture of classical music. I think we really do and it’s unfortunate that people don’t really recognize that we do. It may be that it’s expressed in different ways, maybe a lot of it is through film but I think that we do have a lot for opera and orchestral music as well. I would be really happy to be a part of new compositions based on this American culture.

360 of Opera: What are some of the new roles you are preparing and how are you approaching them now that you are able to sing them?

The voice is just like our bodies when we are growing up as teenagers, first we look funny and awkward and then we level up! The same happens with opera, you have to grow into your voice. It’s something that happens throughout your life but being 25 versus 35 years old is very different. And I’m sure that when I’m 45 it will also be different. But at least now I have a better understanding of my voice and I look at my voice in a different way. I’ve grown into my voice more and as times goes on, hopefully I’ll be able to continue to grow into it and be able to make the proper changes that are right for myself.

As far as roles, I’m learning Leonora, Luisa Miller and Tosca. I’m actually in the practice room right now! I’m making sure I can get the roles into my body. I do believe most things get better with time. So, I’m sure Tosca will be one of those. I can sing it now, but I have it coming up in 2020/2021 and 2022. As I get older, I hope it gets better and better, I pray. It happened with La Bohème and I keep learning more and more about the piece as I go.

360 Of Opera: The opera lifestyle can be challenging. What is your relationship to it and how do you stay grounded?

It’s hard, this is not an easy job because we are gone a lot, we are not home most of the time. I think having a healthy lifestyle and mind is important. My thing is more spiritual, I have to have peace in my heart and in my mind to be able to do my job.

The psychology of singing is important. You cannot let everybody into your head or into your world. I have a very small circle of friends, a coach and a voice teacher, with whom I’ve been working for 15 years, his name is Vladimir Chernov. Whenever I need to talk to somebody, I talk to those people. If I’m not grounded, I feel like I’ll be a walking mess.

Scheduling can be very difficult too. Right now, we have three days between shows, some people fly home in between shows, but that extra traveling can be stressful for me. It takes a lot of balancing. The biggest thing for me is to have my spiritual life in order.

360 of Opera: Could you tell me about your work with Sylvia’s Kids Foundation?

Sylvia’s Kids Foundation is an organization that I founded with my mom. She grew up in what would be considered the ghetto near Cleveland, Ohio. Her parents were restless with trying to provide her and her siblings with a better lifestyle, but they were not able to get them out of that environment. My mom and her siblings all worked very hard to eventually get out of there.

I’m the only one in my family who sings. All are musical, but everyone is either a teacher or a psychologist, or a therapist. When we moved to California, my mom was working with a lot of inner-city kids, who grew up like her. Then, my siblings and I became mentors of the church my parents were working with. In 2016 I said to my mom: “I would like to go back to that, it would be great to work with kids again.”

She was teaching in Nevada and she had a student who was struggling to graduate, we wanted her to succeed. So, my mom helped prepare her and I funded her to get through the schooling, so she could graduate. That’s when I realized we should start an organization for inner-city high school kids, who are graduating and trying to go to college. It could be anything, but they need to be continuing on with their studies. I thought we should name it Sylvia’s Kids Foundation after my mom, because they are all her kids!

I’m so excited with how all this is developing. With our foundation and the Arts High School I went to in California, we’re giving two awards this year to graduating seniors. It’s such a blessing to be able to give back and see the excitement on young people’s faces when they have that kind of encouragement to go to the next level.

Going back to that video on my channels, that’s one of the reasons that I put that out there. I just want people to have encouragement and be helped and happy, because I know I need that too. And I just want everyone to know that there really is greatness inside of each of us. It just depends what we choose to do with it!

To learn more about Angel Joy Blue, visit www.angeljoyblue.com and follow Angel on her social channels under @angeljoyblue.

Photo Credits: The Metropolitan Opera & AngelJoyBlue.com

#360ofopera#AngelJoyBlue#Soprano#MetOpera#OperaPerTutti#OperaLover#OperaSinger#ClassicalMusic#OperaLife

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Va, Tosca!

I’ve been fascinated by ‘Tosca’ since three years ago, when I first heard it in Kiev opera. What motivated me to dig deeper was the stubborn anti-Puccini bias of music critics that started with the opera’s (nay, it's antecedent play’s) premiere and didn’t really cease by this day. Which I cannot understand at all: ‘Tosca’ is literally one of the most popular operas in the world, outperformed only by such eminent names as Verdi’s ‘La Traviata’, Mozart’s ‘Die Zauberflöte’, Puccini’s own ‘La Boheme’ and Bizet’s ‘Carmen’. So what gives?

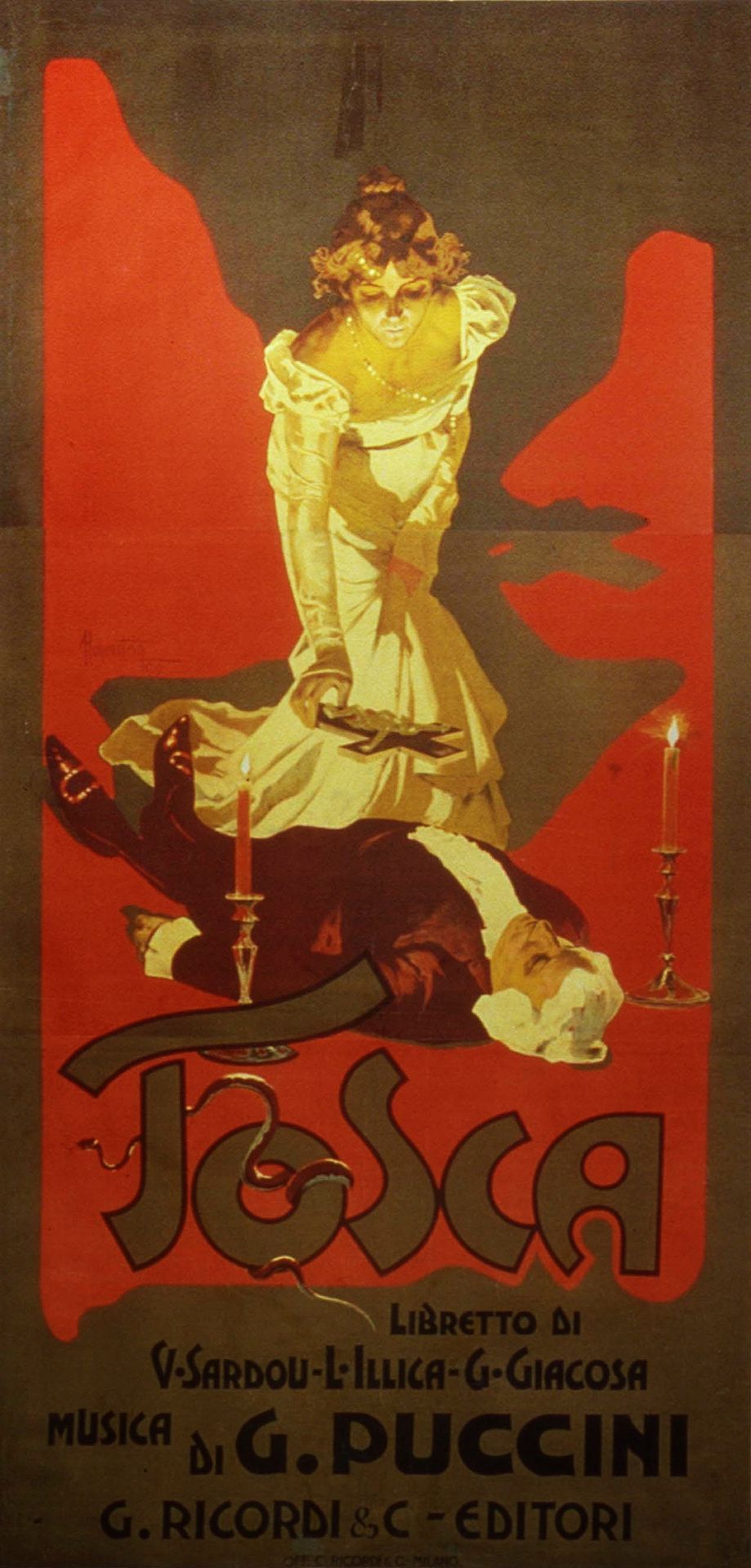

‘Tosca’, original poster, 1899

The premise of this 3-act opera by Giacomo Puccini is rather simple: a villain wants a girl who loves a boy who loves her back and also helps revolutionaries. And also it’s a tragedy, like in a Shakespearean Everybody Dies kind of tragedy. You can pretty much guess the plot from there.

What I personally like about this opera is the combination of lightning-fast plot (the action takes place within several hours on June 17-18, 1800), finely developed character portraits, and music that explains and foreshadows everything you need to know.

Naturally, I don’t take the vague criticisms of ‘Tosca’ all that well.

Ha più forte sapore [bits of history and background]

Puccini’s opera is based on a 1887 5-act play ‘La Tosca’ by Victorien Sardou.

Puccini had seen La Tosca at least twice, in Milan and Turin. On 7 May 1889 he wrote to his publisher, Giulio Ricordi, begging him to get Sardou’s permission for the work to be made into an opera: ‘I see in this Tosca the opera I need, with no overblown proportions, no elaborate spectacle, nor will it call for the usual excessive amount of music.’

M.J. Philips-Matz ‘Puccini: A Biography’

I found this quote, and it instantly clicked: it’s exactly why I like ‘Tosca’.

In contrast to Sardou’s initial work, Puccini’s opera is much more succinct and direct. It has almost zero overblown dialogues and soliloquies that don’t promote the plot or develop characters (well, maybe there is this one lyric soprano-tenor duetto ‘Amaro sol per te m’era il morire’ [‘Only for you did death taste bitter for me’] in act III that’s a bit too long for my taste, but even this slow moment is essential because it gives the audience an opportunity to breathe as the final shockwave looms closer). But the rest of it is actually interesting to see and hear.

For me, ‘Tosca’ is one of the very few operas that are targeted at people who are not fifteen and overly dramatic adult audiences who don’t need same things repeated at them all the time and who can catch what is happening without seeing each and every small detail. Puccini squeezed Sardou’s acts II, III and IV into a single second act, and it works. We as an audience don’t need to see the whole scene at Cavaradossi’s house to understand what happened there. We can use our imagination to paint the rest of the picture.

Looks like the critics do not agree with me on this one.

Perché, perché, Signore [criticisms galore]

The infuriating part about the critical landscape of ‘Tosca’ is that the critics don’t seem to agree on a single point of reproof. Some complain that the opera is too wordy; others, conversely, are not satisfied with the plot rushness (the view that both librettists of ‘Tosca’, Illica and Giacosa shared). Critics called the opera ‘three hours of noise’ that lacks style and cohesion. Julian Budden [opera scholar] faulted the ‘inept handling of the political element’ while commending ‘a triumph of pure theatre’. Burton Fisher [opera writer] described the sensuous love duet ‘Qual’occhio’ as ‘an almost erotic lyricism’ and ‘pornophony’.

Is it just me, or do the critics dislike ‘Tosca’ precisely for the nuances I love about it: coherence of the plot, acute and restrained drama, absence of excessive political speculations (it was not meant to be goddamn ‘Les Miserables’) and, well, musical puns? More on that later.

Not to say ‘Tosca’ didn’t receive its share of praise. Charles Osborne [music critic] believed the plot of ‘Tosca’ was taut and effective while the characters had enough opportunities to shine both in terms of dramatic development and musical elaborateness. Some also praised the richness of Puccini’s score:

[Puccini] finds in his palette all colours, all shades; in his hands, the instrumental texture becomes completely supple, the gradations of sonority are innumerable, the blend unfailingly grateful to the ear.

Ippolito Valetta [music critic] ‘Rassegna Musicale’ in ‘Nuova Antologia’

The aspect of criticism that I did find explainable was based on ‘disconcerting vulgarities’ as put by Gabriel Fauré [composer]. To be honest, the opera really does not lack in violence: Tosca undergoes sexual assault, is broken by the need to defend her chastity with murder and by the death of a beloved, and finally commits suicide. For the public back in 1900 such developments truly could be regarded as a bit too much.

For modern audiences, however, the events are nothing to be shied away from. The opera aged exceedingly well, not losing a bit of its attractiveness in romantic and dramatic sense. Even more so, the criticism that ‘Tosca’ still receives today makes little sense. Joseph Kerman’s [musicologist] remark on ‘Tosca’ as a ‘shabby little shocker’ from the middle of the century, well after the actual real-life shock of two world wars and the brusque shift of public morale, was way off the mark. Thomas Beecham [conductor] bitingly responded that anything Kerman said about Puccini could ‘safely be ignored’ (it almost makes one thing something personal’s involved).

Besides, some modern scholars share my perception of ‘Tosca’s treatment:

Scholarly presses and journals still deeming [Puccini’s] operas too popular to be worthy of serious study continue to shoot themselves in their collective foot.

Deborah Burton ‘Tosca’s Rome: The Play and the Opera in Historical Perspective (review)’

By Burton, Puccini was often simply ‘snubbed by the musicological establishment’. The fun part? Puccini put on his Scarpia persona to cynically and kind of affectionately if you ask me describe ‘Tosca’ as ‘zibaldone’ [‘hodgepodge’]. He referred to it as ‘a vile opera’ and ‘quella putana di Roma’ [‘that Roman whore’]. If this isn’t love.

Già, mi dicon venal [quick glance at the initial play]

Similar criticism of abundance of violence was applied to Sardou’s play. Tosca’s behavior was deemed ‘unchaste’, and the brutality disturbed both critics and theatre fans. Jules Favre [statesman] even called it ‘cette pièce vulgaire, sans intrigue, sans caractères, sans moeurs’ [‘vulgar piece, without intrigue, without characters, without morals’].

The most offensive part of the play was, apparently, Cavaradossi’s torture. Even off-stage, his screams prodded the critics to warn women against seeing ‘La Tosca’ as the play could ‘inflict irreparable injury on persons yet unborn’.

Despite this, the play was an immediate success. It toured around the world, and even the harshest critics couldn’t ignore its dramatic effect:

As to the play itself, I will only add that it is offensive in its morals, corrupt in its teaching, and revolting in its brutality, and yet everyone who admires acting is bound to see it.

Cecil Howard [theatre critic] ‘La Tosca’, ‘The Theatre’

So. Let’s see what threw people in such a dismay, shall we.

Io de’ sospiri [plot and why it’s good]

Sylvester Feodosiyevich Shchedrin ‘New Rome. Castel Sant’Angelo’, oil on canvas, 1823

It all starts with Roman ex-consul Angelotti escaping the clutches of tyrannical justice. The fugitive runs into Mario Cavaradossi, painter and Bonapartist who agrees to help him. Two men are interrupted by Mario’s passionate lover and Roman opera celebrity, Floria Tosca. After a fit of jealousy she leaves the church, and Cavaradossi leads Angelotti away from the city to hide in his villa. Right afterwards, Baron Scarpia, chief of police and the embodiment of tyranny emerges on stage and, when Tosca returns, devises to use her jealousy to lead him to Mario and Angelotti.

Second act is all about torturing Cavaradossi (off-stage) and Tosca’s gradual breakdown. Scarpia demands the location of Angelotti, which she surrenders to save Mario from suffering. Then Scarpia tries to force Tosca to give herself to him, which she agrees in exchange for her lover’s life - only to stab unsuspecting Scarpia with a knife.

The rest of the main cast dies during the third act. Mario’s ‘staged’ execution appears to be not so fake as Scarpia promised. Tosca, inconsolable and heartbroken, jumps to her death as the soldiers, who discovered Scarpia’s body, corner her on the ramparts of Castel Sant’Angelo.

The plot pretty much follows Sardou’s play, although the action was tightened (mostly by avoiding obvious plot turns) and the list of characters sharply compressed.

Sardou’s act III features a scene that is not present in Puccini’s opera: Cavaradossi’s villa, the painter, Angelotti, and later Tosca and Scarpia. One of the things I liked about the opera is that it doesn’t have this scene. It’s excessive and basically tells nothing that audience couldn’t have picked up from the unobtrusive operatic dialogue in act II. Puccini - Sardou 1:0.

Obviously, Mario’s execution was not fake. In the play, Spoletta reveals this fact to Tosca. In the opera, he at first misunderstands Scarpia’s order (hilariously so, as he nearly confesses the whole thing to Tosca), which allows the audience to guess their scheme. 2:0 for subtlety.

In act II, Scarpia questions Mario with the backdrop of Tosca’s cantata performance off-stage, in the depths of Palazzo Farnese. 3:0, this whole piece is just gorgeous.

Puccini wanted ‘La Tosca’s plot stripped of everything excessive (which is, lamentably, a rare practice for operatic genre):

[Puccini] cut Tosca to the bone, leaving three strong characters trapped in an airless, violent, tightly wound melodrama that had little room for lyricism.

M.J. Philips-Matz ‘Puccini: A Biography’

Ignoring criticisms, Puccini also persevered in his clear vision of how the ending should be - by the way, nearly the single thing he and Sardou agreed upon. A good thing undoubtedly; I’d hate for this to happen:

Puccini’s librettists also disliked the suicide, and an alternate ending for the opera was (briefly) considered: rather than leap, Tosca would go mad, collapse, and die on the body of her lover (presumably of Sudden Operatic Death Syndrome).

Susan Vandiver Nicassio ‘Ten Things You Didn’t Know about Tosca’

Pure gold of a remark. Thank you, Susan.

‘Tosca’ is a very tight, succinct work, beautifully paced. I like how the acts are structured and developed. Act I, the longest one, was clearly meant to be expositional. Also, it’s the melodramatic one, with inclusion of comedic motifs that significantly lighten the mood (think the character of the Sacristan and continuous good-hearted mocking of Tosca by her lover).

Act II is unexpectedly macabre: there’s not a trace of the lightheartedness of act I. A real drama ensues, with torture, violence and grim ending (Tosca murders Scarpia in cold blood, which I, as a cynic, viciously enjoy every time). This act is also shorter while it still has enough room for Scarpia’s intricate manipulation and blooming deconstruction of Tosca. The characters are well-developed and nicely motivated (at least in part Sardou’s merit).

Act III is the shortest (just over 20 minutes), and it’s a full-on tragedy. The final plot twist was hardly intended as one. This act is an emotional roller-coaster. Combining hope and death, it is based on fragmented pieces, which makes the whole thing feel real, not operatic. The opera ends strong and loud, and it’s perfect that way. The audience is left with the sense of tragedy that is not undermined by unnecessary lyricism of long pre-death arias (like in Verdi’s ‘La Traviata’, I absolutely hate the last act). With the rush of events, the delay at this point would be unendurable.

‘Tosca’ is chaotic in its final scene, just as it should be. Tosca the character makes the (suicide) decision in a blink of an eye, and I absolutely love the impression that she makes it out of egotistical motives: she is to be captured by the soldiers - not because Mario is dead. This is the kind of nuance that defines the difference between real living people and operatic character embryos. When the opera ends, I always find myself speechless and anguished not irritated at how annoyingly long it takes for the characters to die (looking at you, Verdi).

E lucevan le stelle [characters breakdown]

Palazzo Farnese, 2018. Now French Embassy in Rome

First and strongest impression about the characters of ‘Tosca’: gosh, they are not dumb! So it is possible.

One of the major appeals of ‘Tosca’ is that the characters feel like real people instead of archetypal damsel in distress, knight in shining armor and flat cardboard villain. Although Scarpia bends a bit in that direction, being completely satisfied with his villainous villainy, he acknowledges it, giving off the air of a ‘connoisseur of evil’ instead. William Ashbrook [musicologist] recognized Puccini as a portraitist who honed lifelike characters. Even the smaller characters like the Sacristan (‘an avaricious hypocrite’), Angelotti (exhausted but proud-spirited escapee) and Spoletta (when Scarpia says ‘jump’ he asks how high a perfect minion) are miniature studies of human nature. ‘Tosca’, in his opinion, is a portrait gallery of real-life people.

Floria Tosca [soprano]

For some unfathomable reason, ‘Tosca’ is defined as a melodrama, which is totally different from how it feels with its darkness and the fact that everybody of significance dies in the end. Wiki says melodrama is ‘a dramatic work in which the plot, which is typically sensational and designed to appeal strongly to the emotions’ - basically, plot over characters. Instead, [scenic] tragedy (defined by Google) is ‘a play dealing with tragic events and having an unhappy ending, especially one concerning the downfall of the main character’.

The latter is literally the plot of ‘Tosca’, especially as the title character undergoes a whole set of the most traumatic experiences (concessions to conscience, attempted rape, murder in defense, witnessing torture and execution of a loved one) in a span of just several hours. This set of experiences naturally draws a basis for her downfall (literally): under stress and with no opportunity to think thoroughly, it is not surprising that Tosca commits suicide.

She is strong-willed and passionate, pure-hearted (which is probably why she doesn’t see through Scarpia’s schemes) but not stupid, loyal but also jealous. More out of habit, if we to believe Julian Budden [opera scholar]:

[Cavaradossi, act I, scene 5] Mia gelosa! [My jealous [Tosca]!]

[Tosca] Si, lo sento, ti tormento, senza posa. [Yes, I feel it, I torment you unceasingly.]

All in all, she is a harmonious character in dire circumstances, and it’s a true delight to observe how Tosca, despite how broken and devastated she is, finds the power to oppose her offender. This is the real plot twist (character twist?) of the opera - and I assume the reason that ‘Vissi d’arte’, Tosca’s major aria (an emotional plea of a character who is about to betray her very self) is so well-known and recognized.

Mario Cavaradossi [tenor]

In comparison with Tosca, Cavaradossi is a deceptive character. At first glance he might appear rather flat: nothing more than a loyal lover and a proud revolutionary. Upon closer inspection, however, the audience discovers liveliness and realism many male operatic characters severely lack: he jokes with Tosca instead of oh-so-common sickeningly sweet sighs of love. He knows her flaw of being prone to jealousy - but doesn’t take it too close to heart. He listens to her without interruption as she tells him about Scarpia’s advances (for sure, I was waiting for a hateful scene where he would scream ‘how could you’ at his lover and bang his head against a wall). And he actually knows how to appreciate that she willingly sacrificed her purity for his sake (and he sings an aria about it, too: ‘O dolci mani’ [‘Oh, sweet hands’]).

Besides the believable romance with Tosca, Cavaradossi has excellent dynamics with Scarpia. As the news of Napoleon’s victory arrive, Mario - once tortured - cannot resist the urge to relish in how stars turned for his nemesis:

[Cavaradossi, act II, scene 4] Vittoria! Vittoria! L’alba vindice appar che fa gli empi tremar! Libertà sorge, crollan tirannidi! [Victory! Victory! The avenging dawn now rises to make the wicked tremble! And liberty returns, the scourge of tyrants!]

Tosca tries to stop his prideful speech, aware of how this flows right into Scarpia’s intention to lock revolutionary Cavaradossi up. But Mario is lost in his surging emotions and forgets both himself and his lover at this moment - truly a detail each of us can relate to.

And also Cavaradossi seems to know that his death is not going to be faked - a twist that no one but pure-hearted Tosca is fooled by. He doesn’t believe in Scarpia’s generosity for a moment, and so he doesn’t even try to pretend he is surprised but ironically ridicules the mere idea of a magnanimous villain:

[Cavaradossi, act III, scene 3] Scarpia che cede? La prima sua grazia è questa… [Scarpia yields? This is his first act of clemency…]

Unbelieving but relieved by Tosca’s appearance and intoxicated by her hopeful rambling, Mario chooses to spend his last moments languishing in her presence: he doesn’t want to spoil this time for neither of them. Beniamino Gigli [opera singer, performed as Cavaradossi] wrote in his autobiography that ‘[Mario] is certain that these are their last moments together on earth, and that he is about to die’.

This interpretation of the character is common among the opera singers:

Unlike Floria, Cavaradossi knows that Scarpia never yields, though he pretends to believe in order to delay the pain for Tosca.

Tito Gobbi [opera singer and director]

However, instead of displaying understandable despair, Cavaradossi falls back to his original optimistic self and starts to subtly mock Tosca’s attempts to teach him how to die theatrically. She replies with ‘non ridere’ [‘you mustn’t laugh’], and he softly reassures her. They’re just so sweet together without the usual operatic mawkishness.

(I suspect Tosca is not entirely convinced of their unscathed escape from the clutches of now-dead Scarpia, as well. No wonder she feels uncomfortable at the prolonged preparations.)

Baron Scarpia [baritone]

The villain of this story was actually the first among the main cast to catch my attention. Scarpia is just so explicitly entertaining in his sardonic wickedness. Still, I can see how he could be interpreted as the least 3-dimensional of the three.

Scarpia is a clever interrogator and a talented manipulator. He knows where to hit and when to push to get the answers he needs. Pressing Tosca more and more, he breaks through her defenses until she is frustrated and annoyed to the point of losing her self-control:

[Scarpia, act II, scene 4] L’Attavanti non era dunque alla villa? [So, the Attavanti was not at the villa?]

[Tosca] No, egli era solo. [No, he was alone.]

[Scarpia] Solo? Ne siete ben sicura? [Alone? Are you quite sure?]

[Tosca] Nulla sfugge ai gelosi. Solo! Solo! [Nothing escapes a jealous eye. Alone. Alone!]

[Scarpia] Davver? [Indeed!]

[Tosca] Solo, sì! [Yes. Alone!]

[Scarpia] Quanto fuoco! Par che abbiate paura di tradirvi. [You protest too much! Perhaps you fear you may betray yourself.]

Tosca, with her passionate, fiery temperament, explodes - Scarpia knows about this peculiarity all too well and is able to use her outburst as a clue in his investigation. He continues the pressure all through act II: Mario is tortured, and Tosca is forced to listen to his agony. She eventually crumbles, unable to persevere in keeping Mario’s secret:

[Tosca, act II, scene 4] Nel pozzo… nel giardino… [In the well… in the garden…]

This confession is so succinct, just like the rest of the dialogue in this opera. Tosca doesn’t say ‘wait, I’ll tell you everything’, doesn’t try to play for time; she just betrays the whole thing in two short phrases, without specifying what she means. There’s no need: they’re on the same page.

And then Scarpia goes one step beyond and acknowledges his villainous ways, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing but makes him a bit more caricature. Delightfully so, but still. While Tosca nurtures released Cavaradossi to conscience, Baron cunningly waits for the opportune moment, and strikes, ordering Spoletta to bring in Angelotti. He gloats at Cavaradossi, smugness dripping off of him: see, she betrayed your trust! Mario, tortured, exhausted, half-conscious, falls for it, throwing Tosca’s hands away:

[Scarpia, act II, scene 4] Nel pozzo… del giardino. Va, Spoletta. [In the well… In the garden. Get him, Spoletta.]

[Cavaradossi] Ah! M’hai tradito! [Ah, you have betrayed me!]

Cavaradossi picks this up from the dialogue between Scarpia and Spoletta - again, no one clarifies anything. Like you do in real life. Subtlety y’all.

Now that the villain has Cavaradossi locked up and preparations for his execution in progress, he is one step away from getting what he wanted from the start. Tosca consents to sleep with him but still cannot conceal her hatred, unavoidable ‘you can have my body but not my heart’ trope, which doesn’t stop his lust in the least - on the contrary, inflames him more:

[Scarpia, act II, scene 5] Che importa? Spasimi d’ira, spasimi d’amore! [What does it matter? Spasms of wrath or spasms of passion…]

Naturally, when Scarpia is finally killed by Tosca, the audience is bound to feel satisfaction and not regret. Even Floria, the established virtuous character, has no shame as she recognizes Scarpia as the ultimate threat:

[Tosca, act II, scene 5] Ti soffoca il sangue? Muori dannato! Muori! Muori! Muori! È morto! Or gli perdono! E avanti a lui tremava tutta Roma! [Is your blood choking you? Die accursed! Die! Die! Die! He is dead! And now I pardon him! All Rome trembled before him!]

But Scarpia is a disillusioned aristocrat rather than a one-dimensional villain. What lets him gain more flesh is his motivations - get rid of the rebels (for power rather than ideological considerations) and get the girl (personal gain), - his backstory and notoriety among the revolutionaries, working relationships with other characters and the fact that he continues to live through his actions (arguably the main theme of the opera). Even when dead, Scarpia continues to serve as a villain of the story: Mario dies, and Tosca shouts her curses at him:

[Tosca, act III, scene 4] O Scarpia, avanti a Dio! [Oh, Scarpia, [we meet] before God!]

This gives weight to the character as Baron doesn’t disappear as soon as he dies. His life and death both have consequences. His actions have lasting power - a feature that fictional villains far too commonly neglect.

Even though Scarpia possesses some cartoonish features, he is far from being as simple as Wile E. Coyote. Meep meep.

Vissi d’arte [finally, let’s talk music]

Riccardo Manci ‘Mario Cavaradossi singing ‘E lucevan le stelle’, inspired by the tenor Giancarlo Monsalve’, 2014

William Ashbrook described Puccini’s music as ‘telegraphic’ and ‘highly charged’. The reason behind such an impression is the combination of several major leitmotifs that interact, evolve and explain the story. Fugitive motif, love of Tosca and Mario, Scarpia’s theme, torture motif, Tosca’s theme and Cavaradossi’s farewell to life are used as a patchwork that tells the story. These leitmotifs - what Edward Greenfield [music critic] calls ‘Grand Tune’ concept - are memorable and unique, as well as quite distinct from their musical surroundings:

Puccini does not develop or modify his motifs, nor weave them into the music symphonically, but uses them to refer to characters, objects and ideas, and as reminders within the narrative.

Burton Fisher ‘Tosca: Opera Study Guide and Libretto’

Torture motif is one succinct example of how a single simple melody is used to pump up the mood. It first appears as a foreshadowing with Scarpia’s forming intention as he learns Cavaradossi was taken into custody:

[Scarpia, act II, scene 2] Meno male! [Not bad, not bad!]

It grows more and more pronounced as Cavaradossi is questioned - threatening but not quite powerful yet. On the backdrop, Tosca’s cantata also gains volume and solemnity - pure delight mixed with anticipation of terror:

[Scarpia, act II, scene 3] Questo è luogo di lagrime! Badate! Or basta! Rispondete! [Beware! This is a place for tears! Enough now. Answer me!]

And the theme finally loses its careful insinuative tone and thunders at full volume when Scarpia orders Mario into the torture chamber, right before Tosca’s eyes:

[Scarpia, act II, scene 4] Mario Cavaradossi, qual testimone il Giudice vi aspetta. [Mario Cavaradossi, the judge awaits your testimony.]

The melody elaborates with Mario’s torture heard from off-stage, reaching its breaking point as Tosca breaks and reveals Angelotti’s hiding. It repeats again after Mario is released - slow and woeful, intertwined with Tosca’s and Mario’s love theme that is now devoid of its previous light hopefulness.

Statue of Michael the Archangel, Castel Sant'Angelo, 2018

I love how music acts as a separate character in the opera. It talks to the characters, responds to them, inquires and leads the conversation. In act I, while Cavaradossi sings about his love to Tosca, the Sacristan reprovingly grumbles about obscene youth on the background. Besides, here lies the great benefit of veristic [realistic] opera that allows the characters to have duologues - Mario and Floria sing their lines separately in a conversational form rather than a boring duet.

Music gives the opportunities of quieter moments, to talk in phrases but also in gestures. During act II, Tosca uses gestures a number of times to answer Scarpia: a nod of the head, a wave; subtle yet expressive. They nearly don’t talk while Scarpia writes her a letter of safe passage. This quiet scene also allows Tosca’s character to unfold, her decision to feel earned. She sees the knife, she hesitates a moment; then she grabs it and hides behind her back: the decision is made. No words necessary; the score allows the characters to be silent while it tells and develops their story.

And it also allows the characters to talk all at once, without listening to each other. By the middle of Act II, as they learn about the battle of Marengo, Mario starts to shout about victory, Tosca tries to shut him up, and Scarpia reels about hanging the revolutionary. They clamor; chaos ensues, and music supports the flurry of eddying noises by playing disparate motifs. The best part about this scene is that it delivers the message loud and clear, on both levels of plot and emotions.

Talking about Puccini’s score, it’s impossible to ignore the musical cohesion and integrity: each of the three main characters has their theme and their own designated aria that allows them to shine. Moreover, as each of their arias happen once per act, I enjoy the interpretation of their dominance: Scarpia in act I, Tosca in act II, Cavaradossi in act III.

Act I. Scarpia’s ‘Te Deum’: lust, menace, church bells

The theme of the villain is played out in contrasts that reflect his character: cunning and smart - but ruthless and just on this side of crazy. Scarpia is also a figure of power, both literally and figuratively, and he is foreshadowed in the score long before the actual appearance of the character on stage. As Baron is first mentioned in the conversation of Angelotti and Cavaradossi, his dark theme abruptly breaks through the much less strident music:

[Angelotti, act I, scene 6] Tutto ella ha osato onde sottrarmi a Scarpia scellerato! [She has dared all to save me from that scoundrel Scarpia!]

Immediately, this menacing ascending theme is associated with the villain. Later, as he enters the stage, no one calls him by his name, yet the audience immediately recognizes him as Scarpia as he is accompanied by that same simple motif.

The appearance of Baron sobers and darkens the mood instantly, his leitmotif invading other themes unscrupulously. Establishing yet another contrast, his conversation with Tosca is escorted by the tolling of bells that lasts till the end of act I. Scarpia raves about his poison spreading through Tosca’s thoughts, and his unnerving, acrid soliloquy transforms into the solemn Adagio religioso in ‘Te Deum’.

This superposition of profane lust of a ferocious man and sacred sublimity of the Catholic chant is what makes the audience shudder. The final ‘Te aeternum Patrem omnis terra veneratur’ [‘Everlasting Father, all the earth worships thee’] should be the solemn virtuous hymn to God but instead the act ends with Scarpia’s theme reiterated in thunderous chords - an ominous admonition of impending threat. Brilliant. Act I definitely belongs to Scarpia.

Act II. Tosca’s ‘Vissi d’arte’: plea of a broken soul

Second act is all about tempo. The action rushes forward non-stop. Scarpia gives Tosca less and less time to think, to estimate her situation, pushing her to her into the abyss (count how many falling jokes I make through this post). However, he misjudges Tosca’s limits and pushes her just a bit too far.

The point of no return for Tosca is her aria where she asks God why she has to endure all this suffering.

[Tosca, act II, scene 5] Vissi d’arte, vissi d’amore, non feci mai male ad anima viva! […] Nell’ora del dolore perché, perché, Signore, perché me ne rimuneri cosi? [I lived for art, I lived for love: never did I harm a living creature! [...] In this hour of pain, why, why, oh Lord, why dost Thou repay me thus?]

The score is lyrical, slow and wailing as Tosca mourns her faith. The aria ends with a low sob that is nearly spoken with raw emotion instead of sang. (Fun fact: while today the opera is probably most well-known for this aria, Puccini didn’t really like it and wanted to cut it out of the opera altogether; in all honesty, it does lack the musical potency of ‘Te Deum’ and ‘E lucevan le stelle’ even though it’s a palatable piece that delivers the idea of character deconstruction rather well.)

Tosca is left completely broken. Modern sopranos commonly fall to their knees while performing this aria, and there’s a good reason: when Tosca finally finds the power to stand up, she is a different woman. For me, this is when the main plot twist happens: usually, heroines in operas are meek and hesitant instead of decisive and offensive. Tosca breaks the pattern and shoves the knife through her offender’s ribcage. She owns act II.

Act III. Cavaradossi’s ‘E lucevan le stelle’: I die in despair

This aria is so renown even people who dislike opera have heard it at some point. It starts with a subtle, tender clarinet solo (possibly the most well-known operatic clarinet theme of all times). The melody is forced up but then sags, losing its power. It’s the pace of destiny, dragging and sorrowful, measuring what little time Cavaradossi has left. This is Andante lento composed in minor key and slow tempo - something that Mosco Carner [musicologist and conductor] calls ‘Puccinian lament, reserved for a character in an extreme situation - death or suicide’. Perfect to denote present anguished dolor.

Mario meditatively recites the first two lines, which feels like an improvisation. The audience witnesses an extremely intimate although fragmentary memory that ends in a grieving ‘muoio disperato’ [‘I die in despair’]:

Puccini insisted on the inclusion of these words, and later stated that admirers of the aria had treble cause to be grateful to him: for composing the music, for having the lyrics written, and ‘for declining expert advice to throw the result in the waste-paper basket’.

William Ashbrook ‘The Operas of Puccini’

Bravo, maestro!

I dislike the currently popular hysterical sobbing at the end of the aria that can be heard from modern tenors (e.g, in staging of ‘Tosca’ at La Scala). It sounds as a ‘hoquet tragique’ [‘tragic hiccup’] that jumps out too much and is slightly out of character - such rendering is more appropriate for Tosca’s character not Cavaradossi’s.

Still, this is arguably the most beautiful, heart-wrenching lyrical aria I’ve ever heard; I’m literally still not over it, after 3 whole years of listening to it, sometimes on repeat. Also, Placido Domingo is the best Cavaradossi, shut up I’m not wrong (1976 film starring him and Raina Kabaivanska is wildly enjoyable).

As a bonus, act III (specifically its beginning and ending) deserve an honorable mention. Despite where the plot says the most dramatic moment of the plot is, for me, it’s the beginning of act III. Here’s the pinnacle of the opera: the contrast between the serene aria of a shepherd boy accompanied by the love motif - and the grim, heavy, shuddering theme of Cavaradossi’s farewell that the orchestra splashes on you as if it is a bucket of ice cold water. The music swells - you wait for the volume to stop growing, but instead it just tears through your eardrums.

The timpani are impossibly good for this piece. Intruding the peaceful, pastoral Roman morning full of hopeful dreams and the colors of sunrise, they suddenly throw the audience into the pit of pure unadulterated horror. Trembling and vibrating on low frequencies, they gift you with the feeling of earth opening under your feet, sucking you into the dark depths you’ll never get out of to see light - say farewell to life.

Similarly, the ending is extremely powerful. The drums start slowly at first, setting the rhythm. Before Cavaradossi’s execution, the orchestra is subtle and insinuating; it accrues and thickens in its vicious predictions. After the shots, as Tosca discovers Mario’s death, the tempo breaks through the roof. The music is desperately, deafeningly loud, it screams of tragedy. And, well, I am aware of the plot of the opera by now, but I’m caught off guard every time. I blame this on music. It just so perfectly reflects the mood of the events; it’s pure gorgeousness that gets to my very core every time.

There’s another point of criticism I need to mention in regard to the final theme that ends the opera: against logic, it is Cavaradossi’s farewell instead of more fitting love theme or, even more appropriately, Scarpia’s motif. This I cannot disagree with as, plot-wise, using this theme would provide the dramatic closure for the opera. However, given my love for theme of farewell, I cannot find the heart to dislike Puccini’s choice after all. Act III is largely focused on Cavaradossi, and the finale acknowledges this.

...Undoubtedly, Puccini was a genius. It’s not easy to comprehend the mastery with which he weaved a handful of simple motifs into a powerful story I cannot stop listening to. But also, there’s this:

Puccini’s sense of humor was often of the schoolboy variety, and he found risqué musical puns irresistible. In Act II of the opera, after Spoletta has assured Scarpia that ‘everything is ready’ for the execution of Cavaradossi, the Chief of Police turns to Tosca and softly asks, ‘Ebbene?’—’Well?’ She says nothing, and the score tells us that she indicates her submission by nodding her head. But at her silent reply the orchestra, anticipating the two-note theme of the ‘execution’ motif, plays the two-note phrase, A and C, or in Italian solfeggio, La and Do. The syllables, in addition to being musical symbols, also happen to be words in Italian: the words ‘La do’ mean ‘I'm giving it,’ and it is the usual way for women to say, I'm ready to give ‘it’ (to you).

Susan Vandiver Nicassio ‘Ten Things You Didn’t Know about Tosca’

It is quite possible there’s more of such minutiae. I’m not sure how to feel about a piece that simultaneously cracks me up and throws me into a pit of despair. But I definitely like it - that much I know.

Castel Sant’Angelo, 2018

Recondita armonia [some fun trivia]

The tone of the dialogue was elevated quite a bit. Get this: comforting Cavaradossi after he was tortured, Tosca says ‘Ma il giusto Iddio lo punirá’ [‘But a just God will punish [Scarpia]’]. The initial line was ‘Ma il sozzo sbirro lo pagherà’ [‘But the filthy cop will pay for it’]. Far less distinguished, my dear.

Puccini visited Rome specifically to mimic the early morning bells. Kudos for authenticity. Also, initially, the composer spent an ungodly amount of money to cast the bells he needed for the performance of ‘Tosca’. The orchestras till today have difficulties satisfying the composer’s vision.

Sarah Bernhardt, an actress who became the prototype for Tosca in Sardou’s play, while performing in Rio de Janeiro in 1905, injured her leg in the final scene when jumping from the rampart. As a result of poor treatment, she lost her leg ten years later. Gory.

Two of the most famous opera singers chose this opera as their farewell: Maria Callas as Tosca gave her last performance in 1965, and Luciano Pavarotti as Mario Cavaradossi in 2004.

In one of the performances with Placido Domingo as Mario Cavaradossi, his son was featured as a shepherd boy.

Before Puccini got to write ‘Tosca’, Giuseppe Verdi expressed his interest. He didn’t like the ending though and wanted it changed - I think we’ve barely avoided another ‘La Traviata’ there, oof.

Oscar Wilde saw ‘La Tosca’ and believed the torture scene was great as it showed how far people can go (no wonder; he was working on ‘Salome’ that evoked indignant discontent of the critics in a similar fashion). George Bernard Shaw also saw the play and, while disliking it utterly, still predicted it would be great as an opera.

In Sardou’s play, Cavaradossi gained a reputation of a Bonapartist in large part because of his mustache. That’s the conclusion I’ve made after seeing these two quotes: ‘Even his mustache was suspect’ and ‘Tosca’s confessor told her it marked him as a revolutionary’. This is gold.

#opera#puccini#tosca#IMHO#why criticism#lots of rambling#greatest opera ever#i don't understand why critics abuse it

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The conductor…in the power he has over others…it is in his interest as a human being, as well as that of his musical achievements, to resist the temptation to misuse it. Tyranny can never bring to fruition artistic-or for that matter human- gifts; subordination under a despot does not make for joy in one’s music-making. Intimidation deprives the musician of the full enjoyment of his talent and proficiency. Yet I should certainly not want to impugn the employment of earnest severity or even the occasional borrowing of the Bolt of Zeus; the latter if the hand knows how to wield it, can in exceptional situations bring surprisingly good results. Severity is a legitimate even indispensable means of dealing with people...”

Bruno Walter

In my Summer of 42 (years), I was a college freshman…again. With neither Mexican weed nor dormitory hijinks to distract me, I worked through the full Brooklyn College Core Curriculum and a handful of music courses. My degree plan also required an ensemble each semester. When the Assistant Dean interviewed me, he looked over my CV and immediately suggested their Jazz Band. After hearing them, I chose a contemporary music ensemble founded by a composition professor. Fall semester, she was on sabbatical and a trumpet prof, Juilliard guy and veteran freelancer, ran the class. To begin, he sat everyone in a circle and asked us to play “Happy Birthday" in hocket. Most of the class was unsure of the melody and some also thought it a stupid idea. With our nonstandard instrumentation, we massacred Second Viennese School composers for the rest of the term.

Spring term, the founder returned. She was just over five feet tall, brown-skinned, with narrow shoulders and mineshaft dark eyes. When she listened, her head nodded while bottomless eyes fixed on you. Raised in a distressed country, her life moved from prodigy to conservatory-trained professional with impeccable musicianship: piano, score reading, solfege, conducting, improvising, composing. Then, she came to the US, with zero money and English and rebuilt her career from scratch. At BC, she conducted the orchestra until politics pushed her out. Now, she gave composition lessons and led this ensemble.

Our roster still read as spare parts: three singers, three pianists, two flutes, violin, saxophone, clarinet, guitar; some highly skilled, others not. For most, English was a second or even third language. Our professor's first assignment: list your colleagues’ instruments, find pieces for a subset of our forces, select only pieces written after 1960, bring scores/parts for audition.

The following week, we presented our finds. First, someone showed her a John Cage duet. As she turned pages, Maestra’s face went blank .

“Why did you get this?”

A mumbled answer.

Maestra closed the score. “You got eet because eet looks easy. Didn't you? First of all, it’s a short duet. Three, maybe four minutes of music. Nothing to do on a real pro-GRAM. Not serious. Not serious at all.”

More mumbling.

“Get something else. Thank you.”

She jabbed the score into their hands, then addressed the class.

“Nothing about John Cage. John is extraordinary. When you choose music, don’t just take a name you theenk you know. Read the score. You are musicians …supposed to be….”

Next, one of the singers produced a folio. Its font, ornate and oversized. I winced. Maestra saw it was a Puccini aria with piano accompaniment and recoiled.

“After nineteen-sixty? Thees? You are kidding me!”

Again, she faced us.

“Thees is NOT opera work-SHOP. I know some of you did not make it there. I'm very sorry about that. Please find some other music to sing. There are so many good theengs. I hope you will find out. Music does not end with Verdi, Puccini.”

So it went. Gratefully, she anticipated our poor choices and suggested some pieces.

Meastra spoke Spanish to some students, aware of the terrain they navigated and supportive. Jorge, a Mexican pianist, was one of her projects. He was a skilled player, an enthusiastic and warm colleague. His giggle often broke up the class. In our third meeting, we rolled the piano front, Jorge sat on the bench. While he longed for mama's home cooking, he wasn’t missing any meals in Brooklyn. His midsection expanded well beyond his tight-waisted pants, straining shirt buttons. Maestra questioned him on preparation: “you’re playing the second movement, what about the third?”

Unaffected by the prodding, he began to play. A minute in, she said, “stop”.

He continued, eyes closed.

She shouted, “Stop! I’m telling you, STOP"

He looked over.

“JORGE….WHAT…ARE…YOU….DOING?”

It wasn’t meant as a question. Jorge smiled and gently shook his head.

“Why are you smiling? Look at you!”

Her voice leveled.

“This is not ready. It’s better, but it's not ready.”

She shifted.

“I am very worried about you. Look..at…your…STOMACH. You need to take better care of yourself. You know, pianists perform in pro-FILE. Theenk what you show to the audience.”

Jorge wasn't smiling. He put his hand on his belly.

“Everyone should con-see-der an exer-CISE pro-GRAM. I am forty years, Dio mio! Almost FEEFTY years older than some of you. Take care of yourselves.”

She dismissed him with a sweeping gesture.

“Ok, who is next? Anna, where is the list? Geeve it to me!”

Her assistant, a brilliant, tiny, Yankee grad student, always cleaned up.

Maestra partnered Jorge with another pianist for a Gyorgy Ligeti duo. Its ingenious architecture, a complex cycle revealed one beat at a time. In Yogi Berra's construction, half the score was ninety-nine percent rests. The players needed infallible inner time. While they played, Maestra leaned over the piano, right hand supporting her, left turning pages. She nodded her head slightly in tempo. The pianist's hits charged toward and away from each other like Pacman's gobbling goblins.

“You are late!” she slammed her left hand down. They went back. Another hammer blow. Back again. The piece never made it to the program.

At the end of the initial class, she approached me about Milhaud's “Le Creation du Monde", a chamber work for winds, including alto saxophone. We didn’t have the other winds, of course, but a young woodwind quintet, in residence for the year, would help out.

“Le Creation" story moves from brooding chorale to a raggy bolero where the winds pass around jumpy tunes, then strut them all, polyphonically, in a joyous finale.

At the first of four rehearsals, we were less than half personnel. Maestra had been enthusiastic about the quintet, encouraging us to meet, hear and study with them. But they were collaborating with major artists and appearing all over the world. Their residency, now in name only. No one in the group even bothered to return her emails. Our conductor was livid. (Later, the assistant assured us that Maestra never returned emails, either.) In rehearsal, the music just marked time. In long stretches with no tune and no landmarks, I fell into a hole and missed my entrance.

“What are you DOING! Counting! Count-ting! I can’t do everytheeng for you.”

Concert day was the first we all sat down to play. In the midst of my disciplined colleagues, I was a bellowing hippo. During the chorale, my slow descending notes were either out-of-tune, out-of-time, the wrong dynamic, or all three.

The baton came down hard “NO..NO..NO. WHAT ARE YOU DOING?"

“How can you be late. It's jazz. Jazz! You play jazz? Right? You know who is John Col-TRANE? Play it like Col-TRANE! Why should I have to tell YOU this. Come on!”

I wore other hats that night: soprano, clarinet. Still, my mind remained fogged through the Milhaud finale.

The quintet players all demolished their solos. With a huge smile, Maestra gave each well-deserved bows. When they were done, she flashed her eyes at me, scowling. Then, jerked both her hands upwards, like she was flipping a pool toy. I stood up and stared straight down.

Next semester, a composition student brought a score. It was mostly squiggles and arrows, notation designed to move the music forward without defining functional harmony or conventional melody. She conducted a circle for each “bar”. We could gauge the length of each gesture and respond in time. Simultaneously, she sang the gestures using their pitched start/end points, conducted, turned pages and offered substantive commentary. If one of us was even a second late, her glance immolated them.

I became friends with some of her students. Waiting outside her office, they often heard shouting. When the door opened, students walked out in tears. Some planned to work closely with Maestra toward their Master's or DMA. Those plans would change...

An alumni couple created an endowed chair for Maestra, protecting her from political games. To celebrate, students accompanied her to the donors’ Connecticut home for a musicale. We loaded two vans with the usual music school suspects: waifish Asian virtuoso string players, an Eastern European sturm und drang pianist, a diffident “difficult” composer, and bit players like me.

Both donors were in their eighties and fabulously rich, earnest, lefty intellectuals. The wife wore a gas mask-like apparatus, its hoses attached to a whirring box on her back. I strained to understand her speech, but her eyes shone with love and curiosity. The couple warmly welcomed us to a large room packed with guests.

I was part of a quartet: oboe, flute, clarinet and piano, playing a student work. The composer, a young Dominican guy, rising star in the program. A Caribbean undergraduate writing skilled takes on contemporary European music. His piece used the difference-tone clusters of Gyorgy Ligeti: loud, high notes, staggered and longheld, producing acoustic anomalies: window-fan undertones and piercing oscillations. Bathing in timbral waves and madly counting beats, I couldn’t find the piano part, though we made it to the end without requiring oxygen or a conductor. The composer took a awkward bow and disappeared.

With Maestra as Maitre’d we served up a baroque cello sonata, Beethoven piano music and some Sondheim. Then, our little foursome loudly dropped a turd on the buffet table.

The donor husband was one of those ruddy-faced white guys who wear baggy corduroys and turtle necks over their barrel physiques. He sought me out, towering above me as I packed up my clarinet.

“What did he mean with that piece?"

“Sir, I…I wouldn’t want to represent the composer, he never said anything about..”

“Now, you must know something.”

He was an important man accustomed to getting answers, fast and in full.

“I know my part and how it fits with the others. The woodwinds are playing difference tones, Stravinsky used...”

“Why didn’t HE explain that to us? We go to concerts all the time. Conductors explain new music. They give examples, give context. You can’t just write something like that and expect people to automatically understand it.”

Gulp....“Of course.”

“It’s his responsibility to help the audience understand the music”

I looked over. By the buffet, the composer was holding a plate, one of the string players laughing next to him. Mrs Donor approached me, extending her hand. The box on her back hissed and clicked. Above the mask, searching eyes, below, a voice from a radio in another room. Was she talking about the quartet? It was too uncomfortable. I interrupted.

“Thank you so much for your hospitality and the opportunity to play for you. You and your husband are so generous.”

She squeezed my hand and leaned in, radio transmission drowning in static. Her husband came to her side.

“My wife is saying we've been to many, many concerts of new music. Starting way back, with Lenny Bernstein. He taught us there’s always something to learn. He introduced us to many extraordinary artists”

He put his hand lightly on her back. Over her shoulder, Maestra was listening to a guest, head level with their sternum, eyes searchlights in reverse. The radio faded and its whirring submerged in the din.

We got back very late. Our vans parked by the gatehouse and turnstile on the east side of campus. A few yellow lights glowed in the music building. Maestra thanked us. We said goodnight.

Drifting on an acoustic sea, our ancestors explored sound, harnessing the waves. Between foaming peaks and psychic undertow, they found power. From our African beginnings, to the stars, every lineage counted on those who navigated, who mastered instruments, who carried in them songs and stories. They became the music, while it lasted.

1 note

·

View note

Text

DMMD Opera AU

Seragaki Aoba is a brand new stage director for the Midorijima Opera Company, whose vision and creativity with the New National Theatre in Tokyo has helped him make a name for himself, as he has achieved critical acclaim for many of his productions. He is the grandson of Seragaki Tae, a former soprano with the company, and the son of Seragaki Naine and Haruka, a famous tenor and soprano couple. Aoba has worked with many of the popular singers of the Midorijima Opera Company, and they all love working with him. The most popular singers are Koujaku, Noiz, Mink, Clear, and Ren.

Koujaku is a spinto tenor. He is the star of the MOC and is sought out for productions from opera companies worldwide, especially after his critically-acclaimed performance as Mario Cavaradossi from Puccini’s Tosca with Teatro alla Scala in Italy. The lyric-tenor-sweetness of his voice allows him to give spinto tenor roles a warm and gentle side, making them truly enjoyable to watch, and is what earned him his popularity. Offstage, Koujaku is still a complete sweetheart and is very kind towards his fellow singers, always ready to give advice to aspiring singers as well. He has great respect for all his singers and truly enjoys learning from them, and he especially enjoys performing alongside baritone Ren. The both of them are noted to have more chemistry and sexual tension together, more than the chemistry between Koujaku and any soprano. His signature role is Radamès from Verdi’s Aida. Here is what his voice sounds like. (Aria: “Celeste Aida” from Verdi’s Aida, tenor: Franco Corelli)

Noiz is a buffo tenor. Not only can he create distinct voices for smaller comic roles, but he is incredibly skilled in acting. He rose to popularity after his performance of Spoletta from Puccini’s Tosca with the Deutsche Oper Berlin, and has worked with numerous German opera companies before arriving at the MOC. While he appears cold onstage, Noiz is quite kind offstage, and interviewing him is always a pleasure. He and Koujaku used to be rivals, but have since warmed up to one another and enjoy working together. According to Koujaku, “Noiz is someone with great talent and a truly wonderful voice, and I find it a pleasure to work with him”. Noiz has also said that “Koujaku is quite the hero onstage, and his passion is something I admire a lot”. His signature role is Don Basilio from Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro. Here’s what his voice sounds like. (Aria: “In quegli anni” from Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro, tenor buffo: Luigi Alva)