#or the victorian medicines with opium and lead

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Sorry for the miscommunication! It did come off kind of condescending, and I really appreciate the clarification. Text is a tricky medium. Here, as a virtual handshake, have the 'asbestos' section of the book! It's a short paragraph split over 2 pages.

(And here's the book on Internet Archive!)

I bought a weaving book at a thrift store yesterday because it had some really useful info on double weave techniques and I'd like to flip through it more.

Anyway I discovered it was from 1978 when in the "fibers you can weave with" section it listed asbestos

#my posts#like to me its like seeing lead everywhere in the past#i know it was useful in its time#and even has use cases today#but all my life its been displayed as wildly dangerous#so much so that seeing it used as a common thing gives me whiplash#like seeing those old ads for coca cola with the cocaine in it#or the victorian medicines with opium and lead#like useful info and interesting techniques and OH yep thats dated

582 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi friend this ask is a request for you to wax lyrical about Crowley slowly dying of a poisonous dose of laudanum, because it seems That Scene is still on all our minds. <3

Godbless (they said agnostically). This is going to be a mess of a response because I have been working a lot of overtime and am pretty sleep deprived, and also because there are a lot of angles to this.

First off: you're so correct to point out that laudanum is an analgesic and not literally a poison, because I think this slots in so nicely with the pattern of stuff we see Aziraphale consume and why (food and wine, for sensual pleasure) and stuff we see Crowley consume and why (alcohol for numbing and six shots of espresso to brace himself, and now laudanum, a medical grade numbing agent, at a dosage that would have killed Elspeth had he not intervened).

To really get into this I'm going to have to talk a little about something I have a lot of approximate knowledge about: Victorian era medicine. Why I find poison sexy (maybe compelling is a better word here) is partially tied up in the Victorian era and this exact subset of knowledge, which I am going to disclaim right now as not very precise. I research stuff primarily to regurgitate it in fiction, and not for complete factual accuracy.

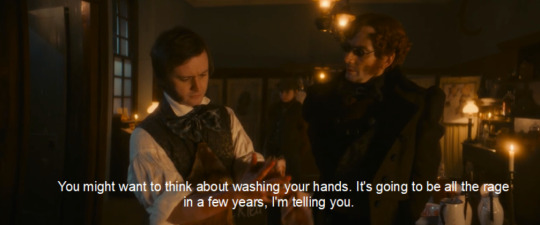

First off, let's take a moment to admire Crowley's prognosticative abilities once again.

Antiseptic is 25 years off, germ theory is held in disdain by the western world, but here's Anthony "that went down like a lead balloon" Crowley just trying to be helpful to this guy covered in blood.

Antiseptic was not in common medical and surgical use until the 1850s. It was pioneered by Joseph Lister, who actually worked at the University of Edinburgh, which was kind of the place to be in terms of medical breakthroughs of this time period. Before the advent of washing your hands and sterilizing surgical equipment, something like 2/3rds of surgical patients died either on the operating table or of infection afterwards. Medicine during this time period was difficult, dangerous work with a high risk of complications, and surgery was haunted by death and disease. Dr. Darymple would have administered laudanum to a patient and then strapped their limbs down and put something in their mouth so they didn't bite through their tongue before cutting into them, and even if he was a good surgeon they might have died a week later from gangrene or sepsis anyway.

It's in this world that laudanum and opium more generally got romanticized by literature and poetry. The Victorians loved opium, but the symbolism of the poppy, from which opium is derived, has been sleep and death since the classical world. My go-to example of the blending of these themes (poppies as sleep and death symbolism and this time period's interest in the classical world) is The Garden of Proserpine by Algernon Charles Swinburne, of which I will include an excerpt below:

No growth of moor or coppice, No heather-flower or vine, But bloomless buds of poppies, Green grapes of Proserpine, Pale beds of blowing rushes Where no leaf blooms or blushes Save this whereout she crushes For dead men deadly wine.

The symbolic connection between opium (and thus laudanum) and sleep and death is my strongest association with either drug. The poppies = death association is used all the time even in the modern day. See this song, Flowers, from the musical Hadestown:

Lily white and poppy red I trembled when he laid me out "You won't feel a thing," he said, "When you go down" Nothing gonna wake you up now

Poppy symbolism is doing a lot of work in this song, actually, drawing a line between virginity and death, and the flower imagery standing in for both Euridyce's sexual relationship with Hades as well as her death but I disgress.

This is my personal context for laudanum and opium. I think it's encouraged to read the sleep and death connection into both of these medicines, both by the artistic tradition that arose contemporaneously with their use and by continued references back to it in the modern day. I am thinking of the scene in Inception where the opium den they visit is full of people who go to be drugged in order to dream their lives away as just one of many other modern day examples. Opium is sleep and sleep is death.

So while the laudanum is not literally poison, I think there is cultural context in which it is possible to read it as symbolically poison, regardless of whether Crowley's not-actually-human body should be able to withstand it. I think that it is compelling to read it as such, given the above-mentioned pattern of Crowley's habits of consumption.

I've seen a lot of posts about how the next time Aziraphale and Crowley see each other after this flashback is the time Crowley asks Aziraphale to bring him holy water and Aziraphale refuses on the grounds that he won't provide Crowley with a suicide pill. While I think this says more about Aziraphale than it does about Crowley (Crowley has never struck me, by behavior or attitude, to be the kind of person who would kill themself, whereas for Aziraphale one of the worst things that could happen would be losing Crowley) there is something there, something in that tartan thermos, something in the idea that Crowley would drink his death.

There is one more angle to this, and this is going to be a bit of a reach. I once read an analysis post in another fandom about the symbolism of poison as a choice of weapon. This line will haunt me until my grave: "a man stabs, a woman poisons". Just as a sword is a phallic symbol, poison (to me) is a feminine coded way to kill another person. For more context, please read The Laboratory by Robert Browning, a poem about a woman procuring a poison to kill her husband's lover, written by another Victorian poet. Crowley dying being discorporated by self-administered poison compels me for all the reasons mentioned above but also for gender reasons. Nonbinary icon.

Crowley dying being discorporated by self-administered poison feels like it is in conversation with two events that happen chronologically later but narratively earlier: the "suicide pill" conversation and Crowley trying to wait out the apocalypse in the bar after the bookshop burned. For all intents and purposes he seems to have given up at that point and only pulls himself together because Aziraphale appears to him and proves he isn't gone gone. It makes sense as an exploration of Aziraphale's anxieties (the suicide pill convo), and the extent to which they might be justified (Crowley drinking as the world ends). It's interesting it's compelling it's symbolically rich it's consistent with characterization choices in the show.

I think realistically Crowley would keep from Aziraphale that he was in pain until he physically couldn't do so, because it would threaten the wall they've had to erect to keep each other safe to do otherwise, but in a scenario where Crowley was hurt, properly hurt, Aziraphale would find a way to excuse them because he would not stand for Crowley suffering.

Just...

The idea of Aziraphale gathering Crowley close in the dark graveyard, feeling him stumble, Crowley who is so bright and brave and beautiful reduced to clutching to Aziraphale and the pair of them trying to will him back to health the way they can choose to sober up, and failing... Crowley because by this point he's too weak, he waited too long putting up a front for Aziraphale, Aziraphale because of conflicting magic or because he's too anxious, his own personal moment of the gun shaking in Crowley's hands during the bullet catch, where he knows what he has to do but he can't do it, can't trust himself not to make it worse.

And then Crowley's body going cold, Aziraphale holding it and crying because despite knowing it's just a body and that Crowley can get another one, he failed to protect him. Crowley died for someone and Aziraphale couldn't prevent it. And the things they don't say to each other, all rushing in to fill the silence left by Crowley's stopped breath. Aziraphale whispering to him, kissing his temple, part of him wondering if he'd ever be able to do this if he wasn't already gone.

It would just be really good, okay. It would be really good.

#the resurrectionist#good omens#meta#i stayed up way too late to write this and now i am going to sleep#tw suicide#tw death

252 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introduction

Drugs can be found present at any point in history, but how the public approaches them completely changes the context around them. While one drug is seen as a threat for society, it can be legalized a few decades later to completely change the narrative around it- and vice versa.

Victorian England was a land of prosperity and booming industry but it also held a dark secret: a widespread dependence on opium. Drugs, no matter what substance it is, always depend on a cultural acceptance. Far from being pushed to the margins of society, opium use can be seen in daily life at the beginning of 19th century, from the comfort of the middle-class poets to the hands of farmers as you will see. This exhibition delves into the vast world of opium in the Victorian era, exploring its presence in several different mediums, from artworks such as poems and gravings to newsletter articles and scientific writings.

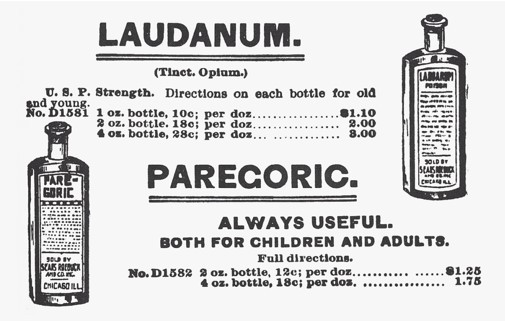

The exhibition begins by showing the visitor that the myth of opium was not something marginal. Advertisements of cough syrups laced with laudanum could be seen, while chemists freely dispensed the drug to heal different conditions such as anxiety or diarrhea. This open access caused a culture of casual consumption, with the working class finding comfort in opium's numbing effects after work hours. This was mainly because they could not afford spirit. Newsletter articles and police reports are snapshots of the era's concerns, as well as their approach to the drug as something beneficial.

Yet, opium wasn't solely viewed as a medicine that helped patients. Literary names of the age such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge and John Keats turned to opium for inspiration, which juxtaposes the use of the drug for relieving illness symptoms. Even though their poems do not primarily focus on the substance, opium can be still found lingering between the lines. Euphoria of the drug is mainly likened to the embrace of death, or a peaceful sleep as seen in the poems. These artworks portray a heightened sensory experience and an introspective peace. The artistic exploration sometimes masks a deep feeling of despair and addiction. The very drug that helped with creativity could also lead to crippling addiction, which can be seen in detail throughout the opening piece "The Gate of A Hundred Sorrows", which was not included in full due to length.

As the allure of opium deepened, so did its association with the Orient. The British Empire's control over vast regions in Asia emerged as a fascination with the East. Opium dens became synonymous with an exotic underworld full of foreigners in East London. Engravings and photographs depicted these dens as places of danger and misery, as well as a place for euphoria. You can see the half-asleep figures shrouded in smoke, and that they were mainly associated with Asians (and thus the Opium War between England and China). This imagery causes stereotyping of the Orient as a land of indolence and moral decay while overlooking the role of British trade in creating an opium addiction across Asia.

This exhibition is a look at advertisements, poetry, and depictions of opium dens to create an image around the substance, as well as a look at daily users who smoke in their houses. Depicting a drug is hard, as the effects and consequences are always bound to subjective experience: So it is hard to depict the complex and often contradictory relationship Victorians had with this narcotic. Here, you will encounter not only the physical dependence, but also the artistic yearnings and societal anxieties. Through examining opium's presence in both the social and literary spheres, we gain a richer understanding of Victorian society, its success and its flaws. So, let's have a closer look at the poppy flower's miracle poison.

0 notes

Text

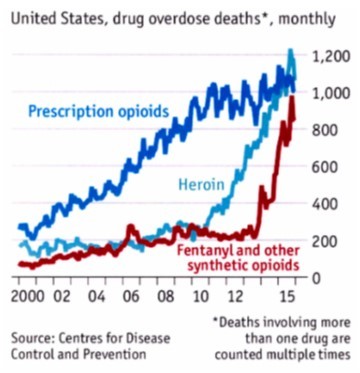

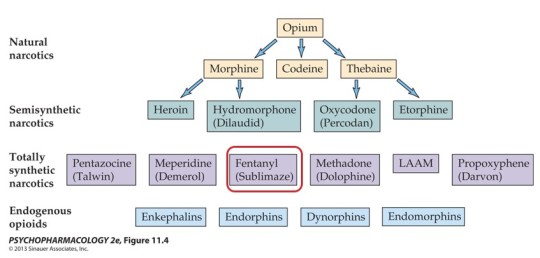

All About: Opioids

- Opioids are substances that act on opioid receptors to produce morphine-like effects.

- Opioids include opiates, an older term that refers to the drugs derived from opium, including morphine.

Opioids = Narcotic Analgesics

- The opioid drugs are narcotic analgesics:

sleep-inducing (narcotic)

pain-relieving (analgesic)

- They are the best painkillers known to humankind, and they also produce a sense of euphoria.

- They create a sense of relaxation, but at high doses, they can lead to coma and death.

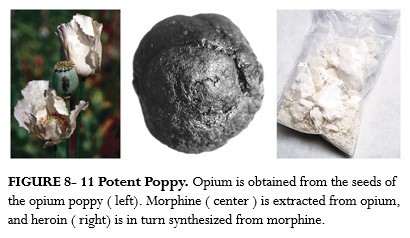

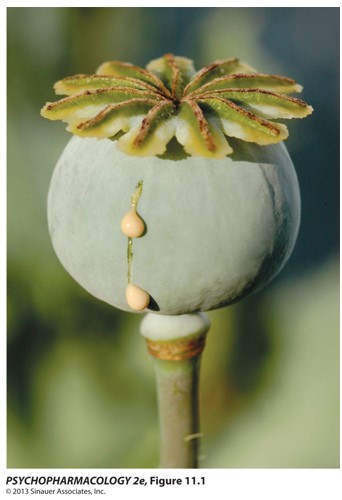

Opium

- Opium has been used recreationally and in medicine for thousands of years (since 5000 BC in China).

- Opium is an extract of the poppy plant (Papaver somniferum).

- Opium is prepared by drying and powdering the milky juice taken from the seed capsules of the opium poppy just before ripening.

- Opium contains morphine, codeine, thebaine, narcotine, and other ingredients.

- Recreational users often smoke opium for its rapid absorption from the lungs.

Opium-Based Products

- Laudanum, an opium-based medicinal drink, was introduced to England in 1680.

- Drinking laudanum-laced wine was the accepted form of opium use in Victorian England & USA.

- Up to the 20th century, laudanum was common in popular remedies.

Morphine

- extracted from the poppy plant in 1805 by a German chemist named Friedrich Serturner

- It was the first time an active ingredient of any medicinal plant was isolated.

- Extraction of morphine allowed doctors to prescribe it in known dosages.

- very powerful analgesic and euphoric drug

- named after Morpheus, the Greek god of dreams

Codeine

- isolated in 1832

- less analgesic effect and fewer side effects than morphine

- A potent cough suppressant, it is often included in cough medicine and in pain relievers.

Heroin

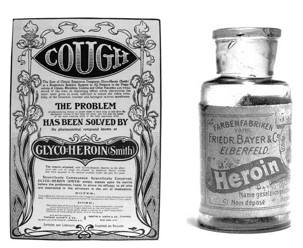

- was developed by the Bayer Company in 1874 to be more effective in relieving pain and cough without the danger of addiction.

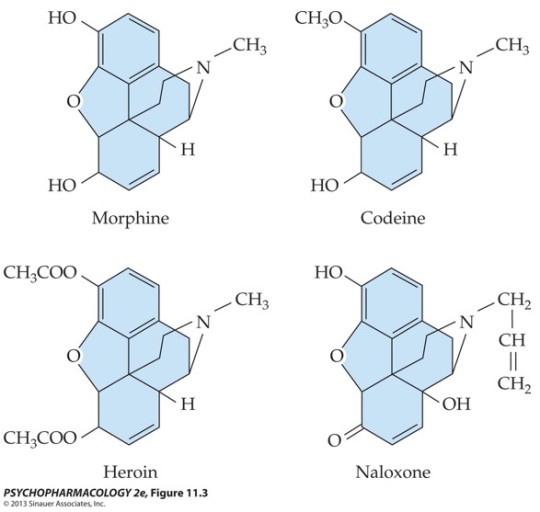

- Heroin was made by adding two acetyl groups to morphine, making it more lipid soluble. The very rapid action of heroin is responsible for the dramatic euphoric effects achieved with that drug.

- as a street drug, preferred over morphine

- pharmacological effects of morphine and heroin are essentially identical because heroin is converted to morphine in the brain.

Oxycodone

- semisynthetic opioid derived from thebaine

- In 1916, German scientists at the University of Frankfurt developed oxycodone as an analgesic less addictive than morphine.

- Oxycodone was approved by the FDA in 1950 as Percodan (mix of oxycodone & aspirin).

- Since the early 1960s, abuse of prescription opioids containing oxycodone has been a major concern in the USA.

- In 1996, Purdue Pharma introduced (and aggressively marketed) OxyContin, a controlled release formulation of oxycodone.

- Purdue advertised Oxycontin as non-addictive because the drug was designed to be released within the body over a 12-hour period.

- Recreational drug users quickly learned to get high by crushing or dissolving these time-release pills.

- Spread of Oxycontin abuse has resulted in increased deaths from overdose.

Molecular structure of morphine, codeine, heroin, and naloxone

Selected natural and synthetic opioid drugs

Heroin = Schedule I

Morphine, oxycodone, fentanyl, opium, methadone = Schedule II

Opioids: Routes of Administration

- Recreational users often smoke opium for its rapid absorption from the lungs.

- Morphine:

in hospitals: intravenous, intramuscular, or subcutaneous injection; or given orally

in the streets: inhalation

- Oxycodone, vicodine: taken orally as pills

- “Snorting” heroin leads to rapid absorption through the nasal mucosa. Subcutaneous administration (”skin popping”) may precede the more dangerous “mainlining” (IV injection).

Opioids: Distribution

- Morphine and oxycodone have similar fat-solubility and only a small fraction of the drugs can cross the blood-brain barrier.

- Heroin and fentanyl are much more fat soluble and can reach the brain faster. They are much more potent when injected.

- Opioids easily cross the placenta. Newborns can suffer withdrawal symptoms but can be stabilized with low doses of opioids.

Opioids: Metabolism

- Morphine reaches peak levels with oral administration within 60 minutes; with IV injection, within 15 minutes. The drug has a half-life of about 90 minutes to 3 hours.

- Fentanyl: with IV injection, peaks in 1 minute; half-life of 1.5 hours.

- Oxycodone: oral administration peaks in 30-60 minutes (controlled release 3 hours); half-life is 3-5 hours.

- Oral administration: first-pass metabolism in the liver reduces the bio-availability of opioids.

- Most opioids are metabolized via CYP-mediated oxidation (codeine, oxycodone, methadone) and have substantial drug interaction potential (with the exception of morphine).

Opioids: Excretion

- After metabolism in the liver, most opioid metabolites are excreted in the urine within 24 hours.

- Typically, morphine can be detected in urine for 1-2 days. In cases of heavy or chronic use, morphine might be detectable for slightly longer, but it usually can’t be detected after about 4-5 days.

Pharmacodynamics: Effects of Opioids

- Effects of opioids on the CNS are related to dose and rate of absorption.

- Low to moderate doses result in:

pain relief (analgesia)

relaxation

dreamy sleep

- Some researchers suggest morphine relieves anxiety, aggression, and feelings of inadequacy. This may lead to more drug use.

- At higher doses, there is an abnormal state of elation or euphoria, described as a “kick,” “bang,” or “rush.” This acts as a powerful reinforcer that encourages repeated drug use.

Pharmacodynamics: Side Effects

(A) Behavioral

- drowsiness, inability to concentrate

- (rarely) adverse effects, such as dysphoria, restlessness and anxiety

- At highest doses, the sedative effects may lead to unconsciousness.

(B) Physiological

- constricted pupils

- nausea and vomiting. Opioids affect the area postrema in the brain stem that elicits vomiting.

- constipation: Opium and morphine have been used to treat diarrhea and can be life-saving to stop fluid loss in severe bacterial and parasitic diseases.

Opioid Overdose

- at highest doses = respiratory depression. In recreational users, tolerance to euphoria develops faster than to respiratory depression.

- Opioids act on the brain stem’s respiratory center; respiratory failure is the ultimate cause of death in overdose.

- sedative effects may lead to loss of consciousness.

- body temperature and blood pressure fall

- pupils become very constricted

- antidote = naloxone (Narcan)

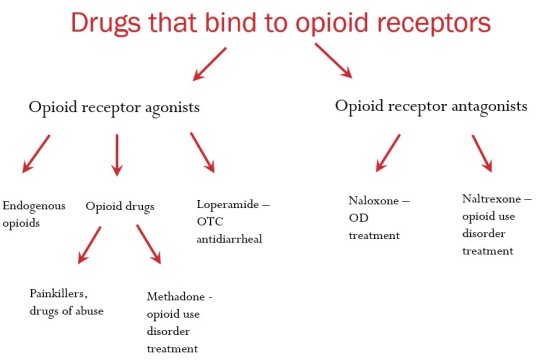

Opioid agonists = morphine, oxycodone, fentanyl, etc.

Opioid antagonists = naloxone, naltrexone

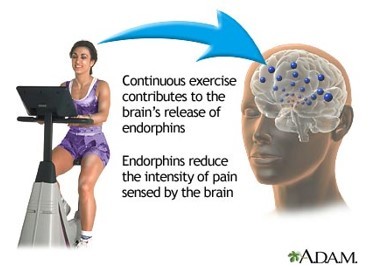

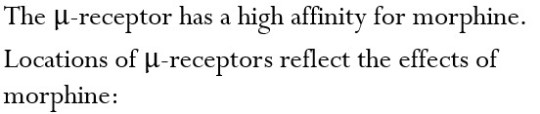

Neurochemical Effects: Receptors and Endogenous Opioids

- Our bodies synthesize our own analgesic substances: endogenous opioids (endorphin, enkephalin, dynorphin)

- Endogenous = produced in our body

- discovered in 1974

- produced in response to pain, but also to exercise, laughter, etc.

- Both opioid drugs and endogenous opioids produce their effects via endogenous opioid receptors in the CNS.

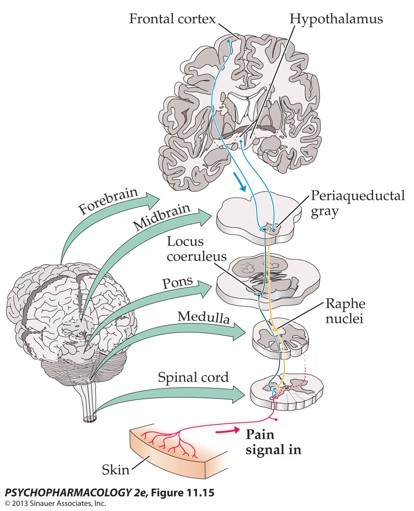

Analgesia - medial thalamus, periaqueductal gray (PAG), median raphe, spinal cord

Positive reinforcement - nucleus accumbens, VTA

Cardiovascular and respiratory depression, cough control, nausea and vomiting - brainstem

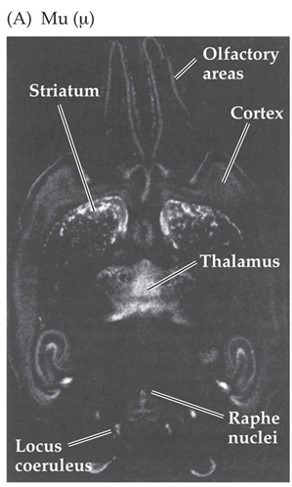

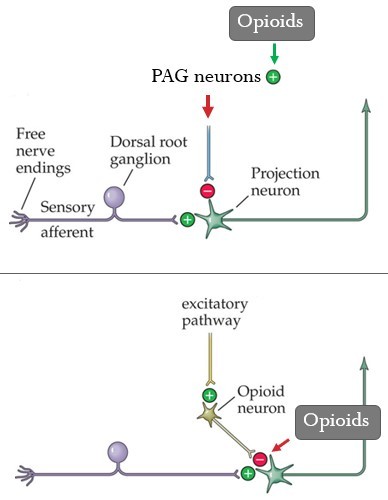

Opioids: Mechanism of Action

- Opioid receptors are metabotropic.

- Opioids inhibit nerve activity in multiple ways:

Postsynaptic inhibition - receptors activate a G protein that opens K+ channels to hyperpolarize the post-synaptic cells, reducing firing rate.

Axoaxonic inhibition - receptors activate G proteins that close Ca2+ channels, reducing the release of neurotransmitter.

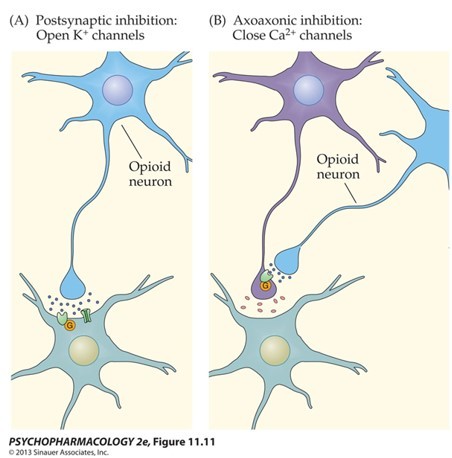

Pain Pathways to the Brain

- How do we feel pain?

- Painful stimuli can be detected by special receptors (nociceptors) located all over our body (including in our skin).

- Sensory information is sent through the spinal cord to the brain, where painful sensation is formed.

- Nociceptors --> Spinal cord --> Thalamus --> Cortex

Pain Management

- Multiple regions in the brain can suppress activity of the pain sensory neurons in the spinal cord.

- PAG (periaqueductal gray) is the key structure.

(I) Opioids stimulate neurons in the PAG that are responsible for inhibition of the pain sensory neurons in the spinal cord.

(II) Opioids directly inhibit the pain sensory neurons in the spinal cord.

(III) Opioids also affect higher sensory areas, hypothalamus and limbic structures in the brain.

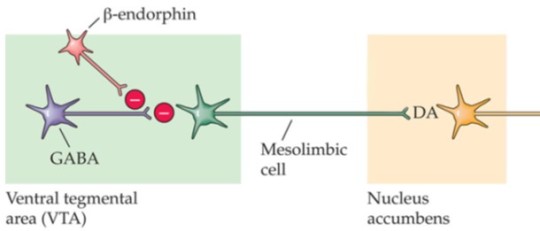

Opioids: Reward Pathway

Reward pathway: mesolimbic: VTA ---> Nacc

- Opioids suppress GABA synapses on VTA dopaminergic neurons

--> Disinhibition --> Increase in firing --> Increase in dopamine release in Nacc

- Experiment: opioids micro-injected into the VTA increase dopaminergic cell firing

- Continued activation of the dopaminergic reward pathway leads to the feelings of euphoria and the ‘high’ associated with opiate use

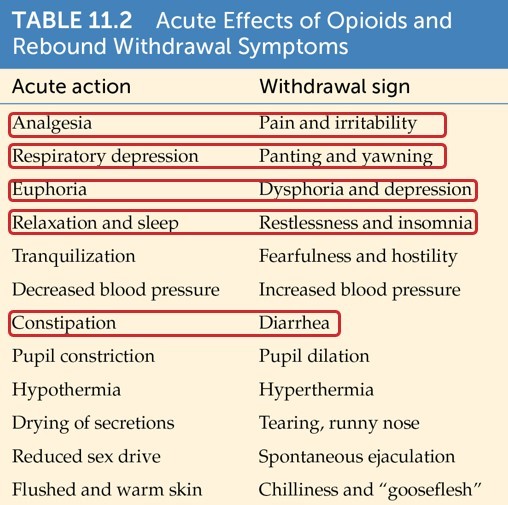

Chronic Use of Opioids

- Chronic use of opioids leads to neuro-adaptive changes, which are responsible for tolerance, sensitization, and dependence.

- Opioids have significant reinforcing properties.

- Opioids effectively produce tolerance.

- Cross-tolerance among the opioids also exists.

- Example: after chronic heroin use, codeine will elicit a milder-than-normal response even if the individual has never used codeine before.

- Physical dependence: neuro-adaptive state in response to long-term occupation of opioid receptors.

- Physical dependence does not necessarily lead to abuse or addiction.

- When the drug is no longer present, cell function returns to normal and overshoots basal levels. Effects are seen in withdrawal symptoms (abstinence syndrome).

- Opioids in general depress CNS function; opioid withdrawal is rebound hyperactivity.

- Abstinence signs reflect a loss of inhibitory opioid action at all receptors in the CNS and elsewhere, as blood levels of the drug gradually decline.

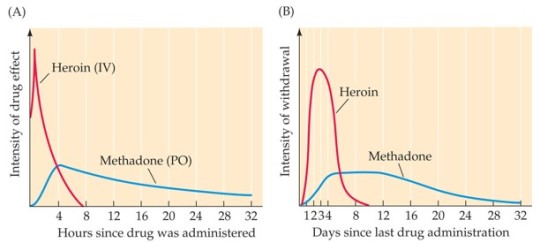

- Severity and time course of withdrawal symptoms can vary with many factors, including the particular drug used:

Heroin: peak within few minutes; withdrawal may begin within 6-24 hours of discontinuation of the drug

Methadone: gradual increase over several days and a gradual decrease over several weeks

- Drug’s time frame can fluctuate with the degree of tolerance as well as the amount of the last consumed dose.

- Withdrawal symptoms can also be classically conditioned.

- The high rate of relapse may be due to the conditioned abstinence syndrome in the old environment.

- Some addicts describe withdrawal symptoms when they visit areas of prior drug use, even years later.

Opioid Addiction

DSM-5: Opioid Use Disorder

- A problematic pattern of opioid use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by at least two of the 11 criteria, occurring within a 12-month period.

Treatment

- A multidimensional approach includes detoxification, pharmacological support, and group or individual counseling.

- Counseling helps addicts identify the environmental cues that trigger relapse and design a behavioral response to those cues.

- Narcotics Anonymous is another option, based on the program for alcohol abuse.

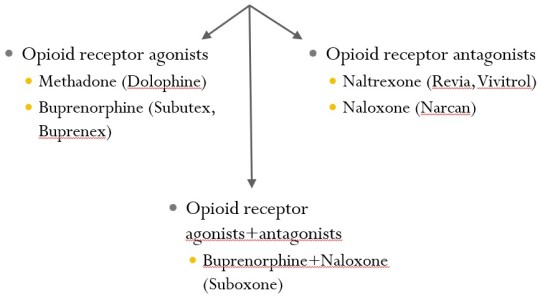

Detoxification is the first step, which can be assisted by opioids such as methadone and buprenorphine (opioid receptor agonists):

substitutes for heroin

reduce symptoms to a comfortable level

Methadone maintenance program:

The most common and effective treatment for heroin addiction. Relieves craving for heroin.

Methadone is long-acting, producing a constant level of drug in the blood.

Methadone has cross-dependence with heroin, which prevents severe withdrawal symptoms.

Methadone can produce a “high” if injected, which could lead to illegal diversion of the drug.

Thus, programs require daily supervised oral administration. Little or no euphoria occurs with oral administration.

Oral administration reduces use of the needle by the addict and the ritual surrounding its use.

- Some treatment programs use narcotic antagonists (= opioid receptor antagonists).

Naltrexone (Trexan) is most commonly used because it has a longer duration of action than naloxone, is effective when taken orally, and has few side effects.

This method is effective for highly motivated individuals. Craving for the drug is not eliminated, so most less-motivated addicts stop antagonist treatment and return to drug use.

Experimental Treatment:

A vaccine is being developed to produce antibodies that would bind to the drug molecules in the blood circulation and prevent entry into the brain.

A vaccine that recognizes heroin and its active metabolites has been tested in rats.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

How would a Victorian woman become a doctor? (Making a female Dr. Watson, part 1)

(This is an ongoing series about the historical case for how canon Sherlock Holmes and John Watson could have been women. It is leading up to the launch of my new web novel series on Patreon, Ladies of Baker Street—a sapphic/wlw, Victorian women adaptation of Sherlock Holmes.

As usual, I’m using the hashtag #A Study In Victorian Women for this series, if you want to follow along. If this interests you, please follow me as well as comment on/like/share this post. Thanks!)

(Photo Credit: Edinburgh Seven & the Surgeons' Hall Riot of 18th Nov 1870,© David Hutchinson, acrylic on board)

Could Dr. Watson have been female in late-Victorian England?

Judging from the number of Victorian-set, gender-swapped Holmes & Watson stories that make Watson a nurse or the wife of a doctor, the answer would seem to be “NO.”

And history would, on first glance, seem to agree with them. Even though there is a long record of female physicians throughout the world, 19th century Britain was unusually hostile toward the idea—even more so than the rest of Europe.

Before we can consider the case for a female Dr. Watson, we need to understand what the situation was for women medical students and doctors leading up to 1878 when canon Watson earned his MD from the University of London.

Most of the hostility toward women doctors wasn’t really based on ideas of female inferiority and weakness or the Victorian “angel of the home” stereotype. Those were just the arguments various men used as an excuse to keep women out of medical training.

Maybe a few actually believed women were mentally and physically inferior, but the loudest protests about women doctors were coming from male doctors and medical students themselves. And it wasn’t because they truly feared for the women’s mental health and safety. Quite the opposite: they felt economically and socially threatened.

You see, up until the mid-1900’s in Britain, being a medical doctor in Georgian and early Victorian Britain was often (but not always) a bullshit job for second sons of wealthy families. All it really took to become a doctor was a lot of money (for university classes in Greek and Latin and botany and anatomy you might or might not actually attend)—or simply enough chutzpah to call yourself a doctor and the marketing skills to con people into thinking your toxic sludge of cow blood, opium, and mercury could cure a huge list of ailments.

In addition to physicians, there were also two other kinds of male medical providers in Britain: surgeons and apothecaries. Both were lower class than physicians, and instead of attending university, their training was usually through apprenticeship. Surgeons sometimes operated on people, but mostly they functioned as general practitioners, doing the actual work of treating patients. Apothecaries were the forerunners of today’s pharmacists and also were able to give medical advice as well as provide medication.

And let’s not ignore the fact that a lot of real medical care was being provided by women in the form of midwifery, nursing, and herbal knowledge.

So all in all, medicine was definitely not a prestige profession. In general, the pay was low unless you were lucky enough to have wealthy patients to support you on retainer or unless you were a good enough con artist to get people to buy your fraudulent remedies.

Obviously, if you are a doctor or surgeon in that time, this is a problem for you. But how to go about raising the status of your profession? Well, there are a couple of options. (Read the rest on my blog)

#a study in victorian women#dr. watson#acd watson#female dr watson#victorian women#women in medicine#victorian history#sherlock holmes meta#acd canon

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

N.S _Wk 1

Today, we had our briefing for the new project. This project seems to be very exciting as I really like the story of Jekyll and Hyde. Having to write my own version of the story is going to be very interesting.

We will be writing a short film screenplay along with a critical essay, both together will be 2000 words. We can go over or under the word limit by 10%. Knowing my writing style I always end up going over the normal word limit I’m so glad that we have a +/- 10%. For the essay we should ideally divide the writings into 1000 words for the screenplay and 1000 words for the essay.

Adapted stories has been popular in the history of animation.

'When I was a boy, animation was... a magical power that could bring fossilised art forms to life'.

Sylvain Chomet (as quoted in Cavalier, 2011, p6)

Calder, S. (2011) The World History of Animation. London: Aurum Press.

In our short film screenplay we may have dialogue or voice-overs, but it may be entirely visual.

Of course we have to read the story in order to understand it. I've read it before but that was a very long time ago. At the time I suppose I didn't fully understand the text. I have to re-read the novella in order to have a better understanding of the text and so that I can create a story inspired by the original story.

I have decided to listen to an Audible version of the novella. This way I can listen anywhere without looking at a book or an e-reader.

Strange case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

A novella by Robert Louis Stevenson published in 1886, the late Victorian era. It was also significantly 2 years before the Whitechapel murders or when Jack the Ripper appeared and disappeared.

This novella is considered the first example of 'Urban Gothic' which is a genre originated from the genre 'Urban Horror'.

We looked the 1st chapter of the novella. There was a few spoilers for people who didn't know the story of the novella.

There has been many film adaptation of this story, the main reason is that it has a strong thematic question as well as a gripping narrative.

Story of Jekyll and Hyde is an Allegory: meaning it has a deeper hidden meaning.

There are many themes that address human condition in this novella, in fact many are still relevant.

This is the main reason it is perfect for an adaptation. The concealed themes/meanings can be shown in various different forms.

In my adaptation I would like to have Hyde as the main character rather than Jekyll.

Though in the original version Hyde is a very vague figure at least according to the other characters. They can't describe him and because Stevenson left the description for Hyde vague it allows the readers' imagination to run wild and is open to interpretation. However in my version he will be described as beautiful young man which takes away certain mysterious air of the character. When the reader imagines the Mr Hyde, they project their own fears and fantasies into the gaps in the description of the character, an example of this happening is when Utterson, a character from the story, imagines how Hyde looks like from Enfield's description. We see that Utterson is haunted by his fantasies of how Hyde looks like, that is until he sees him and the image from his dreams were destroyed.

The first draft of the novella was written quickly, based on a (supposedly drug-fueled) dream. Stevenson called it a 'fine bogey tale'. It is said that his wife Fanny told him to rewrite the story as it could be more than a mere horror story.

Drug-fueled because Stevenson was very ill and weak meaning he had to take a lot of drugs.

I want to keep my story set in Victorian England. I feel that this is one of the key things that will keep my adaptation related to the original story.

Victorian facts:

Prostitution was illegal yet it was rife(common occurrence, widespread). It was estimated that there was around 80,000 prostitutes in London at the time.

Heroin was given to children to keep them quiet. Children were given opiate-based medicines such as Godfrey's Cordial, and the ominously-named 'Infant Quietness'...

'Drug abuse was widespread among Victorian babies' (Goodman, 2013).

Victorians in general were drug takers. Many people often visited opium dens (or gin palaces). It was possible for people to buy cocaine, laudanum, and even arsenic without prescription. Drug addiction is a theme in 'Jekyll and Hyde'. I have decided to keep this theme alive in my story.

Average life expectancy was 38 yrs. Infant mortality was very high, 20% of children died before their fifth birthday in the poorer areas of Britain's larger cities.

They took post-mortem photos. Super creepy! Most families may not have had a chance or the financial resources to take a picture of them when they were alive.

In 1861 there were 640 charities in London alone, mostly run by well-meaning middle class women.

Wallpaper, baby's bottle, drinking water, central heating and painted toys could get you killed.

Painted toys were painted with lead paint - lead poisoning + child = death

Gas heating and lighting were used before the invention of the light bulb. they were very hazardous, switch on light = BOOM! Stoves exploded and people suffocated in their sleep.

Due to the birth of gas lighting, bright coloured walls became a trend, the were dying to have their homes look fashionable, literally. Scheele’s Green’ a brilliant and long-lasting, but deadly wallpaper that was popular at the time. It was made from copper arsenite. This and the Victorian belief that windows should be kept shut resulted in the creation of noxious fumes that killed many in their sleep.

Corsets were worn by women of the Victorian Era. It made it difficult for them to breath and they were easily bruised. Just climbing the stairs made them dizzy.

The high society of the Victorian Era saw ‘tight lacing’ as fashion. The ladies competed to achieve the smallest waist.

The Victorians were hypocrites. They didn’t like to have their hypocrisy pointed out.

They had Anatomical museums opened in order to warn people of the different diseases that they could possibly get if they weren’t careful.

Homosexual activity was made illegal.

Onanism was not permitted and there were devices to help people from refrain from these activities. Famous playwright Oscar Wilde was imprisoned for Homosexual activity in 1895.

The women had it rough for their wrong doing. They had visible evidence of the wrongdoing, this caused many to suicide by drowning themselves in the Thames.

In summary:

Victorian England was a place of strict religious morals.

Violation of the moral code lead to social ruin(loss of job, home, family, children, status...) and possible imprisonment.

Social repression of the unacceptable desires didn’t eliminate those desires, instead it forced them to hide them, thus forming a dual lifestyle, one of a respectable gentleman and one of a secretive man who feed on his secret desires, in a man’s case anyways. Women in general were considered as accessories or the property of a man after they are married. So glad I’m not living in the Victorian England.

0 notes

Text

Drinker's Dictionary Defined - What Does It All Mean?

200+ Intoxicating Expressions Meaning Drunk

Ben Franklin published a list of 229 dictionary words, slang definitions and phrases synonymous with being intoxicated in the Pennsylvania Gazette in 1737.† Like similar inebriated sayings used today, these idioms contain a mixture of condemnation and humor to describe being groggy.

The phrases in the dictionary are not borrowed from foreign languages... but gathered wholly from the modern tavern conversation of tipplers.

~ Ben Franklin

However, only one expression actually mentions a tavern and none use ‘bar’ or public house a.k.a ‘pub’ as a reference. That time period reflects the terms used in the second part of the description in the title: America Walks into a Bar: A Spirited History of Taverns and Saloons, Speakeasies and Grog Shops.

Drinkers Dictionary

Here's all of the saucy synonyms for sloshed used during American colonial times that Ben Franklin collected and compiled for printing in his revolutionary newspaper. Many are still popular tippling terms now.

Ever wonder where all these words, idioms and assorted jargon came from?

The history behind the vocabulary of many of these spirited sayings is documented below. Some are fairly obvious, while others need further research.

We'll keep you posted. Enjoy!

Annotated List of Colonial Drinking Terminology:

- A -

He is casting up his Accounts

He's Addled - Which means confused and so are we. How does a word originally meaning urine or liquid manure morph into this definition?‡

Afflicted

In his Airs

- B -

Has been at Barbados - Settlers on this tiny Caribbean island discovered that molasses, a byproduct of the sugar cane industry, could be fermented into alcohol. This first led to a spirited drink called 'Kill-Devil' which later turned into rum once distillation methods were improved. is quite possibly the birthplace of rum.1

in the Bibbing Plot

Has Drank more than he has Bled

Has Stole a Manchet out of the Brewer’s Basket - A loaf of bread analogy. Grain and yeast is the tie that binds bakers and brewers.

He is as Drunk as a Beggar

He's Bewitch’d

Biggy

Kiss’d Black Betty - A bottle of whiskey in this case; as opposed to a musket, a penitentiary transfer wagon, a whip or the queen of spades et al.

Block and Block

Boozy

Bowz’d

Bridgey

Piss’d in the Brook

Bungey - Sickened; not feeling well.

Burdock’d - Got mead? British Isle beverages made from fermented dandelion and burdock roots have been around since the Middle Ages when Catholic priest and future Saint Thomas Aquinas wandered out for a prayer walk and decided to brew the first two plants he came across.2

Buskey

Buzzey

His Head is full of Bees

He sees the Bears

- C -

He cuts his Capers - An excessive drinking spree, possibly of caper juice (American slang for whiskey).3 Also capernoited: Scottish for muddleheaded or tipsy.

Has taken a Chirriping-Glass - As in a cheer-upping or chirping cup. Yes, that's right. A merry-making glass of liquor that may lead to being cheerfully drunk causing some to sing for joy or even chirp like a bird. You'll probably need to call it a night and hail a taxi home if you ever actually start chirping though.4,5

Come turn up the Boats, let's put on our Coats, and to Ben's there's a chirriping cup; Let's comsort our Hearts, e'ry Man his two Quarts, And to morrow all Hands to cut up;

~ The Whale Fisher's Delight6

He’s been in the Cellar - There's just so many wine varietals to choose from.

Too free with the Creature - Intoxicating liquor, especially whiskey, that Puritan clergyman and Harvard College president Increase Mather called the "good creature of God."7

He is Cagrin’d - Much to his chagrin.

Sir Richard has taken off his Considering Cap - Replaced by the term thinking cap in the late 1800s.

He’s Capable - Or maybe not.

Loaded his Cart

Cat - Katzenjammer, which translates from German as "the cat's misery," is the nausea or headache that goes along with the hangover from drinking.8 Catsood, a corruption of quatre sous, was the price of a drink in WWI France and obviously appeared much later.

Catch’d

Cherry Merry

Cherubimical - Like a child.

Chipper - Perhaps from kipper, meaning cheerful and lively.

Chickery

Chap-fallen

Cock’d - And definitely loaded. May be in reference to Cock ale which is a type of beer mixed with the jellied or minced meat of a boiled chicken along with assorted fruits and spices that was popular in 17th — 18th century England.9

Coguy

Concern’d

Half Way to Concord

Copey

Heat his Copper

Got Corns in his Head

Crack’d

Cramp’d

Crocus - In the Victorian language of flowers, often referred to as floriography, this genus symbolized youthful gladness and mirth causing much merriment and laughter.10,11 Perhaps an Easter Crocus cocktail or two will do the same for you.

Wamble Crop’d - Denotes feeling nausea in his stomach. However, wambling also signifies staggering with an unsteady gait and/or rolling motion which also applies.

A Cup to much

In his Cups

Curv’d

Cut

- D -

He Kill’d his Dog

Has Dipp’d his Bill

He is Disguiz’d

He’s got a Dish

A Dead Man

Dagg’d - A wet fog.

Seen the Devil

He Took his Drops

It is a Dark Day with him

- E -

He has Eat a Toad & half for Breakfast

He is in his Element

He's Enter’d

Prince Eugene - The general of the Imperial Army in August, 1717 personally dispenses extra rations of wine, beer and brandy to his troops to boost their courage as he declares, “Either I will take Belgrade, or the Turks will take me!”12

Got the Pole Evil

Made an Example

Cock Ey’d

Got a brass Eye

Wet both Eyes

- F -

He Owes no Man a Farthing - Former UK coin worth a quarter i.e. 'fourthing' of a penny.

Fears no Man

He’s Been at an Indian Feast

He’s Fetter’d - Shackled with restricted movement.

Fishey

Flush’d

Crump Footed

Sore Footed

Well in For’t

Fox’d

Been to France

Spoke with his Friend

Froze his Mouth

Frozen

Fuddled - Confused and stupefied.

Been to a Funeral

Fuzl’d

His Flag is out

- G -

He had a Kick in the Guts

He’s Been at Geneva

before George

with Sir John Goa - All in the family? See Sir Richard Rum.

He’s Booz’d the Gage

Generous

Glad

Glaiz’d

Got the Glanders

Globular

Gold-headed

As Dizzy as a Goose

Got the Gout

Groatable

- H -

He is Half and Half

He's Hammerish

Hardy

Got on his little Hat

Haunted with Evil Spirits

Got by the Head

Top Heavy

Hiddey

Loose in the Hilts

Taken Hippocrates grand Elixir - Please pass the vīnum Hippocraticum. The spiced wine in this medicinal liqueur will surely kill off these intestinal worms that seem to keep coming back.13

Knows not the way Home

Got the Hornson / Got the Horns on.

- I -

He’s Intoxicated

- J -

He has been to Jerico

He is Jagg’d - Rough around the edges.

He's Jambled

Going to Jerusalem

Jocular

Jolly

Juicy

- K -

He Het his Kettle

Clips the King’s English - Proper speech is trimmed back a bit.

He’s Got Kib’d Heels

A King

Seen the French King

Knapt

The King is his Cousin

- L -

He is Lappy - Laps liquid refreshment with his tongue until loopy.

He’s Light

Limber

In Liquor

Well to Live

Lordly

He makes Indentures with his Leggs

- M -

He is Maudlin - Weeping self-pity makes Mary Magdelen seem austere.

He's Mellow

Merry

Middling

Moon-Ey’d

Seen a Flock of Moons

Rais’d his Monuments

Mountous

Muddled - And his drink was probably muddled too.

Muddy

He sees two Moons

- N -

He has Got the Night Mare

He is Nimptopsical

He’s Non Compos - Mentally unsound for sure.

Eat the Cocoa Nut

- O -

He Smelt of an Onion

He is Oil’d

He's Eat Opium

Overset

Oxycrocium - Possibly from Oxycratum, a solution of water and vinegar, or similarly, Emplastrum Oxycroceum, a medicinal plaster made with saffron, olibanum (frankincense), myrrh and vinegar.14,15 Wanna get plastered?

- P -

He has scalt his Head Pan

He Wasted his Paunch

He drank till he gave up his Half-Penny

He’s contending with Pharaoh

He’s been among the Philippians

The Philistines - See Samson.

He is Pidgeon Ey’d

He’s Polite

Priddy - No doubt giddy as well from attending the Folk Festival and Sheep Fair held in this Somerset village since 1348.

In his Prosperity

Eat a Pudding Bagg - High alcohol content prevents spoilage of the dried fruits and spices sweetened with molasses and held together with eggs and suet fat in this dessert that's a cross between haggis and fruitcake. Usually aged for a month or more, containers made from napkin and cloth bags became more popular than the stomach linings and intestines of animals typically used for storage by the mid to late 1600s since they were safer, easier and more convenient.16

Pungey

As good conditioned as a Puppy

- Q -

He’s Quarrelsome

- R -

He is Raddled

He’s Ragged

Rais’d

Like a Rat in Trouble

Been too free with Sir Richard (Rum) - Along with Captain Whiskey and Sir John Barleycorn.17

Religious

Rich

Rocky

Lost his Rudder

- S -

He carries too much Sail

He has got his Top Gallant Sails out

He is right before the Wind with all his Studding Sails out

He's Seafaring

Half Seas over

Sold his Senses

Burnt his Shoulder

Soak’d

Soft

As Drunk as David’s Sow - Tourists, expecting to view a six legged oddity, instead see the English alehouse keeper's wife sleeping herself sober in the stall and say, "she was the drunkennest sow they ever saw."4

Staggerish

Seen the yellow Star

It is Star-light with him

Steady

Stew’d

Stiff

As Stiff as a Ring-bolt

Stitch’d

Been too free with Sir John Strawberry - Any relation to Thomas Goodale, Richard Beere or Sir William Whitewine? See Sir Richard Rum.

Strong

Stubb’d

In the Sudds

Been in the Sun

Swampt

His Shoe pinches him

His Skin is full

- T -

He has had a Thump over the Head with Samson’s Jawbone (of a donkey) - Not enough to kill him, but probably disoriented and acting like an ass.

Swallow’d a Tavern Token

He is Tann’d

He’s Thaw’d

Tipium Grove

Tipsey

Double Tongu’d

Tongue-ty’d

Top’d

Topsy Turvey

Trammel’d

In a Trance

- V -

He makes Virginia Fence - While many Connecticut settlers stacked up over 50,000 miles of rock barrier, some Maryland pilgrims made Virginia Fence by drinking some of the colonial era Stone Fence cocktails that they invented. A reference to the zig zag construction of split rail fencing that resembles a drunkard walking.18

He's Valiant - Sure is brave after he's had a few. See Prince Eugene.

Got the Indian Vapours

- W -

He has been to the Salt Water

He is Water-soaken

The Malt is above the Water

He's Out of the Way

Very Weary

Wet

Drunk as a Wheelbarrow - Like a German general courtiered [sic] off after too many Lambeth ales.19

Wise

References

* - This misquote is from a letter Franklin wrote to Abbe Morellet where he talks about the rain from heaven watering the vineyards down below which then leads to the grapes changing to wine. Although not verbatim, the rest of the quote is accurate. Guess the analogy became popular because its easier to fit on a tee shirt. You can find more wit and wisdom regarding drink and drinking from Ben Franklin in the Poor Richard's Almanack which he published from 1732 to 1758 under the alias Richard Saunders.

† - Franklin, Benjamin. "The Drinkers Dictionary." The Pennsylvania Gazette [Philadelphia] 13 January 1736/7. Print via.

‡ - Joseph T. Shipley, Dictionary of Early English (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2014), 12. Print. Original was same author and New York, NY: Philosophical Library, 1955.

1 - Barbados - The Birthplace of Rum.

2 - Legend has it anyway. Anecdotal evidence surrounding the origins of the friar's supposed divine intervention appear to be unconfirmed.

3 - John Stephen Farmer and W. E. Henley, Slang and Its Analogues Past and Present: A Dictionary, Historical and Comparative, of the Heterodox Speech of all Classes of Society for more than 300 Years. Vol. II. - C. to Fizzle. (For Subscribers Only, 1891), 34. Print.

4 - Francis Grose with assistance from Hell-Fire Dick and James Gordon, Esqrs. of Cambridge; and William Soames, Esq. of the Honorary Society of Newman's Hotel, 1811 Dictionary in the Vulgar Tongue. A Dictionary of Buckish Slang, University Wit and Pickpocket Eloquence. (originally London: S. Hooper, 1785). Print.

5 - Besides cheer-upping or chirping, other word spellings and forms include chirruping, cherupping, cheeruping and chearupping as in the quote, "for he would take a chearupping Cup off in a Corner" via The Fourth and Last Volume of The Works of Mr. Thomas Brown, Serious and Comical in Prose and Verse. (London: Printed for Sam Briscoe, 1720), 229. Print.

6 - "The Greenland Voyage or, the Whale-Fisher's Delight" A Collection of Old Ballads: Corrected from the Best and Most Ancient Copies Extant. Vol. III. (London: Printed for J. Roberts, D. Leach and J. Batley, 1723-1725), 175. Print.

7 - Harry Gene Levine, "The Good Creature of God and the Demon Rum: Colonial American and 19th Century Ideas about Alcohol, Crime and Accidents," pp. 111-161, by Robin Room and Gary Collins, eds., Alcohol and Disinhibition: Nature and Meaning of the Link, NIAAA Research Monograph No. 12. (Washington D.C.: USGPO, 1983).

8 - 17 of the Finest Words for Drinking. Lots of Happy Hour fun. However, katzenjammer only dates back to 1834 for sure, so it may not be the source of this drunken expression from 100 years earlier.

9 - Kenelm Digby, The Closet of Sir Kenelm Digby Knight Opened: Newly edited, with introduction, notes, and glossary by Anne MacDonell (London: Philip Lee Warner, 1910), 147. Print. Includes facsimile reproduction of 1669 original.

10 - H. G. Adams, The Language and Poetry of Flowers (New York: Derby & Jackson, 1858, [c1853]), 31. Print.

11 - As a somewhat contradictory side note, questionable folklore suggests saffron is a magical medicinal herb that strengthens teeth when drank with beer and will chase away wine odors as well as prevent drunkenness when worn around your neck. (via Pliny the Elder in Naturalis Historia, Book 21, section 81, 79 AD. as translated by John Bostock and H. T. Eiley.)

12 - Dyck, Ludwig. "Prince Eugene's Last Ride." Warfare History Network 26 November, 2018. Accessed 23 January, 2019.

13 - Hunt, Leah (translator). "Medieval Hippocras." Old Cook Accessed 27 January, 2019. Note: similar to mulled wine and said to have inspired the creation of Sangria.

14 - Juhanni Norri, Dictionary of Medical Vocabulary in English, 1375-1550: Body Parts, Sicknesses, Instruments, and Medicinal Preparations (London and New York: Routledge, 2016), 776. Print.

15 - C. L. Lochman (translator). Pharmacopoea Germanica: The German Pharmacopoeia (Philadelphia: David D. Elder & Co., 1873), 79. Print.

16 - Kim Connor. "The Pudding Bag — A Revelation." Turnspit & Table 6 September, 2014. Accessed 25 January, 2019.

17 - The Indictment and Trial of Sir Richard Rum (Boston, 1724). Print. A satirical pamphlet with analysis via "The Transit of 'Small, Merry' Anglo-American Culture: Sir John Barley-Corne and Sir Richard Rum (and Captain Whiskey)" by Joel Bernard of the American Antiquarian Society.

18 - Robert Hendrickson, Dictionary of American Regionalisms - Local Expressions from Coast to Coast. (New York: Facts on File, 2000), 153. Print. Originally published in 1933.

19 - Thomas Dilke, The City Lady: or, Folly Reclaim'd. A Comedy Acted by his Majesty's Servants at the Theatre in Little-Lincolns-Inn-Fields. (London: For H. Newman at the Grasshopper in the Poultry, 1697), 5. Print.

0 notes

Link

A Visit to a Poison Garden Dr. Mercola By Dr. Mercola The 12-acre Alnwick Garden in northern England is home to fragrant rose bushes, manicured hedges, a cherry orchard and stunning water features — all things you'd expect in a traditional English garden. But behind a locked gate is a garden with a much more sinister air — a poison garden home to plants that have the ability to kill. A sign on the gate reads, "These plants can kill," and visitors may only enter with a guide, in groups of 20 or less, who are warned not to touch, sniff or venture too close to the deadly plants. Some are so dangerous they're grown in metal cages with cameras tracking them 24/7. The project was started in 2005 by Jane Percy, the Duchess of Northumberland. Centuries ago, apothecary gardens were quite common in England and were used to grow medicinal plants used for a variety of treatments. Percy was intrigued by the more macabre side of the plant world, however, explaining to Australia's News.com, "What's really interesting is to know how a plant kills you, and how the patient dies, and what you feel like before you die … Most plants that kill are quite interesting."1 Plants That Can Kill in the Poison Garden More than 100 deadly plant species can be found in Alnwick's poison garden. The poisonous properties are often used by the plants as a form of protection. Many of them may be harnessed for good (for instance in the treatment of cancer or nerve pain), with the difference between benefit and harm coming in the dose. For instance, the Helleborus genus of flowering perennials grown in the poison garden were once used to help children get rid of intestinal worms, but if too much was given, it were deadly.2 Other poisonous plants in the garden range from common daffodil bulbs and laurel hedges to marijuana, cocaine, magic mushrooms and opium poppies, for which Percy obtained a special permit to grow. NPR expanded on some of the garden's highlights:3 " … [I]t doesn't take many berries from Atropa belladonna (deadly nightshade) to kill … the plant is common in England and growing happily in the Poison Garden. The duchess also warns that that merely brushing up against the bushy green Ruta graveolens (commonly called Rue) or touching the sap from Euphorbia (the Dr. Suess-like plants sometimes called spurge) can give a person a nasty rash." Another intriguing plant in the garden is datura, also known as angel's trumpets, a night-blooming perennial and member of the nightshade family. Most part of the plant contain hallucinogens that can cause delirious behavior and death.4 Percy told The Telegraph:5 "Datura is an incredible poison, but an amazing aphrodisiac, too, and you see it everywhere. In Argentina, even nowadays, some people put a bell of Datura … on a baby's pillow at night, then take it away after five minutes and the baby has gone to sleep. If it were left all night the baby would be dead in the morning. Victorian ladies used to sit around a table with a datura plant in the middle and play cards or have tea. They'd pop their cup under a bell, tap it, and pollen would fall into the cup. They would experience similar effects to that of LSD." 15 More Plants That Can Kill If you look around your backyard and possibly even your kitchen, you may find a surprising number of toxic plants, ranging from mildly poisonous to deadly. Among them:6 1. Apple Trees Apple seeds contain amygdalin, a plant compound known as a cyanogenic glycoside. When apple seeds are chewed or crushed and metabolized, the amygdalin turns into hydrogen cyanide, which is poisonous. That being said, the cyanide is produced only if the seeds are damaged (i.e., crushed or chewed), so swallowing a few seeds whole is virtually harmless. 2. Nightshade Plants The Solanaceae family of vegetables, informally known as nightshades, includes tobacco, tomatoes, peppers, eggplants and potatoes. The foliage, vines and berries of such plants are toxic and should be avoided. 3. Rosary Pea This plant goes by many names, including precatory bean, Buddhist rosary bead, love bean, lucky bean, Indian licorice, prayer bean and weather plant. Rosary peas are used as ornamental beads for jewelry around the world, but they contain toxic compounds called abrin (a relative of extremely toxic ricin) and abric acid. It's said that jewelry makers have died after from pricking a finger and handling the peas.7 Consuming even one rosary pea can be deadly to pets, but fortunately the seed's hard outer coat must be damaged (crushed or cut open) to cause harm. So in many cases ingesting the seeds may lead to only mild illness. However, if a broken pea is ingested, it can lead to severe vomiting and diarrhea (sometimes bloody), tremors, high heart rate, shock, fever and death among dogs, cats and horses. 4. Oleander Oleander, or rose bay, contains cardiac glycosides that can cause vomiting, dizziness and cardiac dysrhythmias. In Sri Lanka, yellow oleander seeds are often used as a suicide agent, with thousands of cases reported each year. About 10 percent of cases of oleander poisoning in Sri Lanka are fatal.8 Your pet may also be poisoned from access to pruned or fallen oleander branches while horses may be poisoned by consuming this ornamental plant near horse show arenas. 5. European Yew Yew contains toxic taxine in its bark, leaves and seeds, which, if consumed, can lead to sudden death from heart failure. Yew leaves and seeds are also sometimes used by people attempting to commit suicide. Keep an eye out on your dogs if you have yew in your yard; even playing with the branches or sticks from the yew tree could be potentially deadly to dogs. 6. Daffodils Also known as narcissus, daffodils contain lycorine, particularly in the bulbs. This toxic chemical can lead to nausea and vomiting followed by low blood pressure and liver damage. 7. Doll's Eye This plant, also known as white baneberry, is a member of the buttercup family. It has distinctive white berries with an eye-like black dot in the center, growing on red stalks. The berries are particularly poisonous, as they contain cardiogenic toxins. It's said that eating five or six of the berries can make you sick while consuming more can be deadly.9 8. Hemlock All parts of the hemlock plant are poisonous, but the root contains the greatest concentration of poison. Hemlock is said to have been used to execute Socrates, and there are reports of children dying after making whistles out of hollow hemlock stems.10 Ingesting the plant may lead to muscle weakness and paralysis, progressing into respiratory failure. 9. Stinging Tree Found in Australian and Indonesian forests, this stinging nettle can lead to a stinging sensation that lasts for weeks. In animals, brushing past the plant may cause a severe allergic reaction. 10. Castor Beans Castor beans contain the extremely toxic substance ricin. Consuming even one castor bean can kill a human or pet, but the plants are relatively common, even in public areas. Ricin inhibits protein synthesis, leading to convulsions and kidney failure.11 According to NPR:12 "In 1978 a member of the Bulgarian secret police used an umbrella tip to inject ricin — a powerful poison extracted from the beans of a castor plant — into the leg of a political dissident, as he walked down a London street." 11. Monkshood This plant, also known as devil's helmet and aconitum, is so deadly that a U.K. gardener died in 2014 after handling the plant.13 It was also a well-known poison in ancient times, used during battles to poison enemies' water.14 12. White Snakeroot This plant contains toxic tremetol, which is poisonous if ingested, either directly or via contaminated meat or milk. If a cow grazes on the plant, for instance, its meat and milk will become poisonous. Nancy Hanks, Abraham Lincoln's mother, reportedly died from "milk sickness" after consuming milk contaminated with white snakeroot.15 13. Larkspur Larkspur contains compounds called diterpene alkaloids that are toxic to humans, dogs, cats and horses. It's thought the toxicity of this plant varies depending on the conditions in which it's grown and becomes less toxic as it matures. If consumed, larkspur can cause neuromuscular paralysis and symptoms such as muscle tremors, stiffness, weakness, convulsions, heart failure and death from respiratory paralysis. 14. Foxglove This plant grows striking bell-shaped flowers, but all parts of the plant contain digitalis glycosides, which can affect heart function, leading to irregular heartbeat and death in humans and pets. 15. Melia Azedarach This flowering tree, also known as white cedar, is native to Australia and contains berries with neurotoxic poisons. Consuming just six berries may be enough to kill a person, but birds are not affected, so they feast on the berries regularly.16 Plant Poisonings Are Relatively Common in the US While pharmaceuticals remain a top cause of calls to poison control centers, plant exposures also have a top spot on the list. Data from the American Association of Poison Control Centers' National Poison Data System (NPDS) 2013 annual report revealed more than 46,000 plant exposures in the U.S., with more than 29,000 involving children aged 5 years or younger.17 Three deaths were also reported. To avoid poisonous plants, be very careful when selecting which plants to put in your garden or home, especially if you have young children or pets. If you're planning to forage for wild edible plants, consume only those you are sure you can correctly identify and are not poisonous. Fortunately, there are far more edible plants than poisonous ones. Wild plant enthusiast Sergei Boutenko claims there are thousands of safe, edible plants growing wild in North America, but there are only 150 listed by the American Association of Poison Control as poisonous.18 Of those 150, only about 50 are considered to be "highly poisonous" (i.e., can be fatal), and the rest are classified as "mildly poisonous," which means they may cause nausea, diarrhea, or headache, but probably will not kill you. If you see a wild plant you can't identify, the characteristics that you should regard as "red flags" for toxicity include the following. As always, if you're not sure, don't eat it. ✓ Milky or discolored sap ✓ Beans, bulbs or seeds in pods ✓ Bitter or soapy taste ✓ Spines, fine hairs or thorns ✓ Dill, carrot, parsnip or parsley-like foliage ✓ "Almond" scent in woody parts or leaves ✓ Grain heads with pink, purple or black spurs ✓ Three-leaved growth pattern

0 notes

Text

America's First Addiction Crisis Had Some Striking Parallels To Today

Doctors prescribing painkillers willy-nilly. Outrage over foreigners importing “poison” into America. Expensive treatment facilities marketed to addicts from well-off families. These are things America has seen before, when the country went through its first opioid crisis.

“There’s definitely a parallel between our historical moment and the 1860s,” said Susan Zieger, author of Inventing the Addict, a history of addiction in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In the late 1860s, doctors were battling to get the public to respect them as scientifically oriented professionals, distinct from traditional healers. With the invention of hypodermic morphine, they gained a powerful weapon in this battle.

But the drug created a generation of patients who struggled with dependence, leading to attitudes about drug use, treatment, and “worthy” and “unworthy” addicts that remain with us today.

Opium pods had long been a staple of folk medicine, brewed in teas or used in tinctures to treat a huge variety of troubles, from infants’ colic to tuberculosis. By the 1860s, medical journals touted morphine, a distilled form of opium’s active ingredient, as a miracle drug. It launched a big business, and more potent painkillers soon followed.

Victorians Had Their Own ‘Big Pharma’

We can lay a lot of the blame for the current opioid epidemic on the pharmaceutical industry, which has long promoted the heavy use of opioids to treat pain. In the 1990s, doctors increasingly relied on opioid prescriptions to treat chronic pain as a separate problem from any underlying diseases.

In the 19th century, doctors made less of a distinction between a disease and its symptoms. “Any change that could be effected in a patient’s symptoms was seen as acting on the disease; the more effect a treatment had on a patient, the better,” writes anthropologist Marcus Aurin.

At the time, doctors needed to set themselves apart from “homeopaths, regular physicians, natural bone-setters, local wise ones, and so on,” the late medical historian David F. Musto wrote. Medicine that could successfully treat pain gave them that competitive advantage.

That’s why morphine, combined with the hypodermic syringe, was such an important innovation: It was a far more potent way to treat pain. Injected morphine came to be widely adopted in the 1860s and was promoted in medical journals as a “miracle of biomedical science,” according to Aurin.

Describing hypodermic morphine in 1868, Dr. Francis Anstie, editor of the British medical journal The Practitioner, wrote that “of danger, there is absolutely none ... The advantages of the hypodermic injection of morphia over its administration by the mouth are immense ... the majority of the unpleasant symptoms which opiates can produce are entirely absent ... it is certainly the fact that there is far less tendency with hypodermic than with gastric medication to rapid and large increase of the dose.”

In 1898, Bayer began promoting an even more potent injected painkiller ― heroin ― a name meant to suggest a “heroic” treatment.

Rich Addicts Are Sick, Poor Addicts Are Criminals

Many observers have noted how today’s middle-class, white opioid addicts are generally treated as victims of a disease, while poorer black and Latino drug users are more likely to be considered criminals.

The notion of addiction as an illness was a middle-class thing from the start. When doctors first started using the term “addiction” in the late 1860s, it was mainly to describe middle- to upper-class women who typically got hooked on morphine their doctors prescribed. Through the last decades of the 19th century, many physicians set up profitable sanatoriums and addiction clinics to treat these patients.

But by the turn of the century, doctors began to recognize the dangers of handing out morphine syringes to every patient with menstrual cramps or a cough. Fewer well-to-do addicts were being created, and many of those receiving treatment either got well or died off.

“The field of inebriety cure and treatment ceased to be a lucrative one, and doctors rapidly divested themselves of their interest in it,” Aurin writes. “Addiction remained a curable disease only so long as there were patients willing and able to pay for treatment.”

As the number of upper- and middle-class addicts declined, the public face of addiction became the working-class urban man. By the early 20th century, cheap, widely available heroin was the drug of choice for this demographic.

Heroin was essentially the same drug as morphine, but doctors associated it with working-class people and immigrants ― and, therefore, with deviant personalities.

“The heroin addict is of an inferior personality type compared with the morphanist,” AMA President Dr. Alexander Lambert wrote in 1921. “Morphine is the drug of the stronger personality.”

Lambert added that, while heroin and cocaine caused “social and public health problems,” morphine addicts “show no tendency to become a social menace.”

Racism Was Always Part Of The War On Drugs

Speaking at the Mexican border recently, Attorney General Jeff Sessions railed against criminals entering the country to “rape and kill innocent citizens” and “profit by smuggling poison.”

Last year, Maine Gov. Paul LePage (R) complained about “guys with the name D-Money, Smoothie, Shifty” who he claimed bring heroin into the state and “impregnate a young white girl before they leave.”

The first government warnings about the dangers of drugs were also deeply entwined with racism. In 1909, Aurin writes, prominent doctor Hamilton Wright, working on behalf of the State Department to address the opium issue, complained that the country was “contaminated through the presence of a large Chinese population.”

By the 1920s and ‘30s, Zieger said, popular fiction depicted a Chinese-American underworld in which white people risked becoming “enslaved” by opium.

“It was also obviously kind of a fear of white women being seduced by people of another race,” she said.

In fact, this fear had come to San Francisco, a center of Chinese immigrant life, even before the turn of the century. Physician Winslow Anderson described the “sickening sight of young girls ... lying half-undressed on the floor or couches, smoking with their lovers.”

Not surprisingly, San Francisco became the first place in the country to pass anti-opium legislation in 1875. In the early 20th century, as xenophobia spread and heroin and opium use became increasingly associated with the poor, the federal government passed new anti-drug laws.

The epidemic caused by Victorian-era prescribing patterns was over, replaced by Americans’ modern beliefs about drugs ― which are deeply tied to racial and class stereotypes.

Zieger said the war on drugs that began in the Nixon era continues to appeal to some of the same racist and classist attitudes that drove the first wave of criminalization.

“They play to a certain type of right-wing, middle-class desire to punish whoever they can punish,” she said.

Today, that view of drug use as a blameworthy, criminal habit of the “lower classes” is again vying with the concept of addiction as a disease for which the medical community bears some responsibility.

The question, this time, is whether we can extend a more compassionate view of addiction beyond the white middle class.

This reporting is brought to you by HuffPost’s health and science platform, The Scope. Like us on Facebook and Twitter and tell us your story: [email protected].

Sign up for the HuffPost Must Reads newsletter. Each Sunday, we will bring you the best original reporting, long form writing and breaking news from The Huffington Post and around the web, plus behind-the-scenes looks at how it’s all made. Click here to sign up!

-- This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

America's First Addiction Crisis Had Some Striking Parallels To Today published first on http://ift.tt/2lnpciY

0 notes

Text

America's First Addiction Crisis Had Some Striking Parallels To Today

Doctors prescribing painkillers willy-nilly. Outrage over foreigners importing “poison” into America. Expensive treatment facilities marketed to addicts from well-off families. These are things America has seen before, when the country went through its first opioid crisis.

“There’s definitely a parallel between our historical moment and the 1860s,” said Susan Zieger, author of Inventing the Addict, a history of addiction in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In the late 1860s, doctors were battling to get the public to respect them as scientifically oriented professionals, distinct from traditional healers. With the invention of hypodermic morphine, they gained a powerful weapon in this battle.

But the drug created a generation of patients who struggled with dependence, leading to attitudes about drug use, treatment, and “worthy” and “unworthy” addicts that remain with us today.

Opium pods had long been a staple of folk medicine, brewed in teas or used in tinctures to treat a huge variety of troubles, from infants’ colic to tuberculosis. By the 1860s, medical journals touted morphine, a distilled form of opium’s active ingredient, as a miracle drug. It launched a big business, and more potent painkillers soon followed.

Victorians Had Their Own ‘Big Pharma’

We can lay a lot of the blame for the current opioid epidemic on the pharmaceutical industry, which has long promoted the heavy use of opioids to treat pain. In the 1990s, doctors increasingly relied on opioid prescriptions to treat chronic pain as a separate problem from any underlying diseases.

In the 19th century, doctors made less of a distinction between a disease and its symptoms. “Any change that could be effected in a patient’s symptoms was seen as acting on the disease; the more effect a treatment had on a patient, the better,” writes anthropologist Marcus Aurin.

At the time, doctors needed to set themselves apart from “homeopaths, regular physicians, natural bone-setters, local wise ones, and so on,” the late medical historian David F. Musto wrote. Medicine that could successfully treat pain gave them that competitive advantage.

That’s why morphine, combined with the hypodermic syringe, was such an important innovation: It was a far more potent way to treat pain. Injected morphine came to be widely adopted in the 1860s and was promoted in medical journals as a “miracle of biomedical science,” according to Aurin.

Describing hypodermic morphine in 1868, Dr. Francis Anstie, editor of the British medical journal The Practitioner, wrote that “of danger, there is absolutely none ... The advantages of the hypodermic injection of morphia over its administration by the mouth are immense ... the majority of the unpleasant symptoms which opiates can produce are entirely absent ... it is certainly the fact that there is far less tendency with hypodermic than with gastric medication to rapid and large increase of the dose.”

In 1898, Bayer began promoting an even more potent injected painkiller ― heroin ― a name meant to suggest a “heroic” treatment.

Rich Addicts Are Sick, Poor Addicts Are Criminals

Many observers have noted how today’s middle-class, white opioid addicts are generally treated as victims of a disease, while poorer black and Latino drug users are more likely to be considered criminals.

The notion of addiction as an illness was a middle-class thing from the start. When doctors first started using the term “addiction” in the late 1860s, it was mainly to describe middle- to upper-class women who typically got hooked on morphine their doctors prescribed. Through the last decades of the 19th century, many physicians set up profitable sanatoriums and addiction clinics to treat these patients.

But by the turn of the century, doctors began to recognize the dangers of handing out morphine syringes to every patient with menstrual cramps or a cough. Fewer well-to-do addicts were being created, and many of those receiving treatment either got well or died off.

“The field of inebriety cure and treatment ceased to be a lucrative one, and doctors rapidly divested themselves of their interest in it,” Aurin writes. “Addiction remained a curable disease only so long as there were patients willing and able to pay for treatment.”

As the number of upper- and middle-class addicts declined, the public face of addiction became the working-class urban man. By the early 20th century, cheap, widely available heroin was the drug of choice for this demographic.

Heroin was essentially the same drug as morphine, but doctors associated it with working-class people and immigrants ― and, therefore, with deviant personalities.

“The heroin addict is of an inferior personality type compared with the morphanist,” AMA President Dr. Alexander Lambert wrote in 1921. “Morphine is the drug of the stronger personality.”

Lambert added that, while heroin and cocaine caused “social and public health problems,” morphine addicts “show no tendency to become a social menace.”

Racism Was Always Part Of The War On Drugs

Speaking at the Mexican border recently, Attorney General Jeff Sessions railed against criminals entering the country to “rape and kill innocent citizens” and “profit by smuggling poison.”

Last year, Maine Gov. Paul LePage (R) complained about “guys with the name D-Money, Smoothie, Shifty” who he claimed bring heroin into the state and “impregnate a young white girl before they leave.”