#or men who use atashi or uchi

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Okay I do often imagine my OCs conversing in Japanese language by default but Killian likely takes the cake for codeswitching the most often depending on the situation. He uses ore (俺) when personally speaking to people he’s familiar with or when he’s being boastful or feeling like he wants to be a rude delinquent for a bit, boku (僕) when speaking to strangers, his family/employer or in a more professional setting and watashi (私) when he’s reverting into his knight persona. His second-person pronoun aka “you” also varies depending on the situation, but please also imagine him going おい, てめえ!

#★ — 𝙗𝙚𝙣𝙚𝙖𝙩𝙝 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙢𝙖𝙨𝙠. ( ooc )#and yes in jp language personal pronouns =/= gender expression or identity#thus you see many ore onna and bokukko tropes in jp-language works#or men who use atashi or uchi#i love how jp language basically gives more leeway to experiment with characterization really

1 note

·

View note

Text

not to be a weeb but i do think about tarts personal pronoun changing over the years

in arr its アタシ (atashi, its girly and kinda childish) then changed to ワタシ (watashi, technically proper except being written in katakana suggests shes a bit awkward w it) in hvw except when she avoided using that around edmont or the other high house members (even francel tbh, haurchefant and emmanellain are the only exceptions) then in stb zenos made her slip back to オレ(ore, the masculine pronoun which is rude to use irl but its normal for anime boys. in katakana its more casual) its just one time though tart mumbling to herself abt thinking of zenos as her friend.. best friend... (ominous) or it was until he killed himself and tart fully became an ore girl around the alliance soldiers. she didnt rly like this abt herself tbh... so after falling at the ghymlit dark she told aymeric "うちに帰らせてありがとう" (thanks for bringing me home) うち(uchi) taking on a double meaning as both home and a feminine personal pronoun so it also means "thanks for bringing me back to myself" oh im crazy i dont even speak japanese ignore what i say this probably doesnt work lmaooo [if aymeric ever brings this up again tart will absolutely murder him] anyway so in shb and edw she uses ワタシ again except around reeq she would use オレ tbh but its fine this time its different trust me. anyway the big bombshell is when tart the catboy calls the scions to introduce himself after his "fantasia" and uses 私 (watashi. the normal way you write it) in this context i mean it to say that tart has shed his awkwardness and despite the complicated Circumstances around his gender change he is comfortable in his own skin. so even just from that its easy for the scions to accept who he is now. but then. when the rite of succession is over and tart rejects wuk lamats offer to stay as her companion, he starts to use 自分 (jibun, meaning oneself) why, oh dont worry ab--(a page from the website japanesewithanime dot com falls out of my pocket) "The pronoun jibun 自分 is associated with military officers, police men, detectives, professions that follow a strict rules, and where knowing your place in the hierarchy is fundamental." ahem i said dont worry about it hes not a clear reflection of zoraal ja or anything, definitely not someone feeling like hes losing his place in life bc he doesnt know how to exist as his own person and not a weapon for the military. definitely not a problem so bad that sphene cant stand to see him denying his own personhood and she kills him about it. yeah no its all good. so tart as souleater definitely uses オレさま(oresama, the most pompous male pronoun in existence. however not in kanji like 俺様 bc his ass is faking that pomposity) onstage. in fact he should call himself このオレさま(same thing but with emphasis. you want to smack this brat upside the head so so bad) once it would be so funny. hearing tart say jibun outside the arena gives yaana whiplash but honeyb is just like "okay repressed catholic i know what you are 😒" okay thats all i have to say thanks

#tart the wol#if you read this im so sorry. i take no responsibility for the psychic damage im causing

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Oh, by Kaito's Kazuha I meant Kaito's disguise/imitation of Kazuha. I see Kaito's disguises as an interesting look into how he sees them and their relationships and how he uses his disguise of choice for each scheme he has is fun to watch. Characters in-universe can guess at Kaito's face and build do to how he disguises as each person too.

I wonder why he used 'uchi' instead of 'atashi' when disguised as her, it gave them away?

My main complaint with his disguise is that he left her in the stained clothes. He was in a rush so he disguised as an annoying American woman who ignored the no drinks sign and ignored her surroundings. But seeing as he gave Kazuha the outfit after creating a situation where she'd be forced to go and change, I expected him to have a duplicate like when he disguised as Ran when he stole the black star pearl (both detective love interests, both special pearls) by being a dry cleaner and copying her good taste in evening wear. She was safely asleep in the woman's bathroom, a shut single stall at that, but he has changed woman's outfits before (the actress Furuhata Megumi and his childhood friend Aoko) even if he doesn't strip them like he does men and could have at least let her change before knocking her out so she didn't have to continue walking around with a huge stain and could have had the compensation of nice clothes for the inconvenience. It felt out of character to me at least, he's normally a gentleman as KID.

Oh, I get it now.

And yeah, I also agree with the out of character part.

It was also weird when he scattered a bunch of cards to determine when to act. I still don't get why he did that, though. I guess he needs a change of plan because there was a new opponent. Even then, that decision was short-sighted.

Some of the recent heists not only boring compared to the previous ones but also not as clever as they were.

The same can be said when he disguised as Genta and Agasa. Where the mistakes he makes is a little detail he had gotten wrong. Genta's bald spot and Agasa's bandage (There were more on the Agasa's part, but I just think the last one was unnecessary). On one hand, it shows that he's flawed and has a long way to go. On the other hand, these flaws are suck.

When he disguised himself as Ran, there were no obvious mistakes, making it harder for Conan to figure him out. Conan had to treat everyone, even familiar characters, as suspects. This was a clever twist because we were used to the daily-new-characters-are-the-suspects formula that we did not realize he is one of the main ones.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Okay someone asked for an explanation so here is Japanese casual first person pronouns 101 as explained by someone who only mostly knows what they're talking about:

Post title: When you speak Japanese with your friends, which pronoun do you usually use?

私: "watashi". This is the default first person pronoun, like if you pick up a textbook to learn Japanese, this is what you will be taught. In reality, men (especially younger men) generally don't use this casually so it comes off feminine if you're talking to peers, though even women often will use a different pronoun

あたし: "atashi" this i think is one of the more common ways for women to refer to themselves in casual speech, based off of 'watashi'.

僕: "boku" this is a more masculine pronoun, a little bit boyish. Like masculine but in a gentle and friendly way, i feel like i associate it more with people who are outside of the like maybe 13-30 age range but i'm not sure of that

俺: "ore" which is much more masculine in a rougher way. i think this tends to be used more by "the youth" while boys are talking to other boys so i rarely hear this in real life (since most of the Japanese people i know are middle aged women)

うち: "uchi" i don't know much about this one, it's a more feminine and younger pronoun generally. but i hear it's also a regional dialect thing. in real life, i mostly hear it across genders/ages when talking about family like "my children" "my siblings" etc

自分: "jibun" literally it means 'self' and is used as a reflexive pronoun by everyone and as a second person pronoun in some regional dialects and as a first person pronoun by others. basically a super versatile pronoun, i think it's a bit more masculine but i also see it be used as like "the gender neutral pronoun". apparently it's also used by soldiers

自分の名前: your own name (literally "self's name", see the 'jibun' here again). this is more childish and feminine, i definitely used my name instead of a pronoun growing up

他の: something else

1以上: more than one

Note: a lot of these pronouns are "more masculine" or "more feminine" but these are not absolutes. people can and do use pronouns that are not aligned with the gender they're perceived at, for trans and non-trans reasons, both for one-offs and more frequently. I honestly don't know enough about all the ins and outs to be able to say a whole lot more on that, but these are more about vibes than anything concrete

also there's huge amounts of dialect variation that i'm only barely touching the surface of here, and there's a lot of more older pronouns i also didn't include because polls only have so many options and i figured there are not many like 70+ japanese people on tumblr

タッグでなんでこの代名詞を使うか言ってください!

#if anyone knows what they're talking about feel free to correct me on this#i've definitely looked into this and studied it as well as have a fair bit of personal experience#but my perspective does largely come from an english speaker in america#reading stuff in english about it and talking to fellow queer japanese diaspora#and isn't necessarily what the average japanese person would think#my post#spyld

54 notes

·

View notes

Note

ah, I'mtrans (he/him pronouns), and was wondering which words I should use for stuff like "I, me, my"? like, boku is my right? I don't know any ohers though.

Hi! Thank you for your ask. First person pronouns (I, me, mine) can get pretty complex in Japanese, but that gives you much more freedom of expression than English. Let me give you a thorough description of each so you can make an informed decision on which one is right for you. :)

First Person Pronouns in Japanese

Who do you want to be?

In English, we only have one pronoun to express ourselves. “I.” It really doesn’t get any more boring than that.

Maybe that’s why personal pronouns are one of the most interesting aspects of Japanese in my opinion. I actually did a research paper on the history of second-person pronouns (you) in Japanese back in uni.

Why does Japanese have so many ways to say “I?” As I’m sure most of you know, social class and politeness is a fundamental aspect of Japanese culture and language. Different personal pronouns for oneself and others clarify the social standing of each person in the conversation.

I’ll introduce the commonly used ones in order of politeness (most polite to least polite), and then cover the rare ones.

私 Watakushi

Gender: neutral

Plural Form: Watakushi-tachi

This is the most formal personal pronoun, and is used in very formal situations, like when you’re speaking to the president of a company or someone very important. In writing, because it has the same kanji as “watashi,” it is commonly written in hiragana.

私 Watashi

Gender: neutral (kind of)

Plural Form: Watashi-tachi, watashira

This is the most common personal pronoun.

Like the above watakushi, it conveys a sense of politeness. When used by men, it carries a note of humility and politeness.

However, it is the standard pronoun for women. Because we’re all supposed to be humble at all times? haha

So this is gender neutral and you can use it when you want to be polite.

あたし Atashi

Gender: Female

Plural form: Atashi-tachi, atashira

This is a bastardization of watashi.

It is casual and used exclusively by women. It sounds very feminine. In Japanese tv shows and anime, most male characters cross-dressing as women use “atashi” and it sounds very hyper-feminine. Like, if drag is hyper-feminine dress, “atashi” is the hyper-feminine way of speaking that would go with it.

うち Uchi

Gender: Female

Plural: Uchira

This comes from the word 家 uchi. The kanji literally means “house,” but it can be used to mean “my family” or “us” in certain contexts. For example:

Japanese: 田中さんは自宅でどんな醤油を使っていますか?うちはやっぱりキッコーマンです。

Romaji: Tanaka-san ha jitaku de donna shouyu wo tsukatte imasu ka? Uchi ha yappari Kikkoman desu.

English: Tanaka-san, what kind of soy sauce do you use at home? We use Kikkoman.

From that use of uchi we get the personal pronoun uchi. This is generally used by young girls, college age and younger. It definitely has a very Valley Girl feel to it and isn’t professional.

僕 Boku

Gender: Mostly male, but female in certain contexts

Plural: Boku-tachi, bokura

If you want to rely on tropes to understand what sort of person would use “boku,” think of those harem anime. The nicest, sweetest guy almost always uses “boku” for himself. Contrasted with “ore,” it sounds softer, humbler, and kinder.

It can also sound very slightly childish. Well, not childish. It sounds young. My boss’s boss, who is in his 60′s, uses boku instead of ore and it always strikes me as peculiar because he’s kinda too old to use boku. It makes him sound very humble and kind and the most approachable person ever.

Boku is a good pronoun to use if you want to give off a soft, friendly, safe aura. While it isn’t as polite as watashi, you can still use it in formal settings.

Occasionally, this pronoun is used by women. Specifically, it is used by female singers. It doesn’t matter the band, it doesn’t matter the song–every single female singer uses “boku” in their songs to refer to themselves.

“Why?” you may ask. This is because singers want to connect to their listeners, and “watashi” is too formal and creates a bit of a barrier. “Atashi” and “uchi” are too feminine/childish, and “ore” is way too harsh. So “boku” became the choice for female singers.

俺 Ore

Gender: Male

Plural: Orera, ore-tachi

Going back to anime tropes, “ore” is used by the “bad boy” or the “I don’t give a shit what you think” boy. Inuyasha, Kurosaki Ichigo (Bleach), and Eren Yeager (Attack on Titan) all use “ore.” This is in contrast to “nicer” characters in the shows that use “boku,” like Miroku (Inuyasha), Ishida Uryuu (Bleach), and Armin Arlert (Attack on Titan).

Ore is considered “rough and tough” because it is very informal. It is used when the people you are talking to are within your inner circle or are beneath you. So you would never use it when talking to, say, your boss’s boss. (You might be able to use it with your boss if you are close with him and you have a friendship though.)

That said, the vast majority of Japanese men I know use ore more than boku. So it wouldn’t be strange if you used ore. Just be aware that it isn’t as polite as you may want to be.

And now for the rare pronouns…

Disclaimer: DON’T USE THESE. Japanese people will think you’re super weird and not in a good way. But you are likely to hear them in anime, dramas, or conversations.

👆 Me outside your door if you use “sessha” to refer to yourself unironically

拙者 Sessha

Literally “Unskilled one,” this is a very humble way to refer to yourself. It was commonly used by samurai, and probably the most famous anime character that uses it is Kenshin from Ruroni Kenshin. DO. NOT. USE. IT. unless you are jokingly pretending to be a samurai for like one sentence.

吾輩 Wagahai

Though no longer in common usage, there isn’t a Japanese person that isn’t aware of this pronoun because of Natsume Soseki’s famous book Wagahai ha Neko de Aru (I Am a Cat). Written in 1905, it’s about a cat who observes its owners and the uneasy mix of Western culture and Japanese traditions and the aping of Western customs.

“Wagahai” is the pronoun a nobleman or someone of very high rank would use to refer to himself, so the fact that a common house cat is using it to refer it self shows that, even a hundred years ago, everyone thought that cats were self-important.

我 Ware

Plural: 我々 Wareware, 我ら Warera

To be honest, I don’t know a lot about this one. You hear it quite a bit in anime, and it’s always said by some stuffy important old guy. So…it’s probably for stuffy, old, important men to use? Just don’t use it.

己 Ora

Used exclusively by men, the only somewhat main character I’ve seen use this pronoun is King from Seven Deadly Sins. In manga, it is usually written in hiragana or katakana. It has a very “country bumpkin” feel to it. A simple country person who doesn’t know the ways of the world (but not in a bad way).

俺様 Oresama

DO NOT USE THIS UNDER ANY CIRCUMSTANCES. It is the rudest personal pronoun “ore” with the honorific “sama” attached to it.There is nothing ruder, nothing more “you are the dirt I walk upon” than this. If you use this and you’re not joking, the Japanese people around you will instantly dislike you.

儂 Washi

Usually written in hiragana or katakana, “washi” is the way that old people refer to themselves. It’s gender-neutral. Like…idk, 60 and upwards? So don’t use this unless you fall into that age range.

某 Soregashi

I think I’ve only seen this once, used by a character in Rurouni Kenshin who was quickly killed. It was used by samurai. So unless YOU are a samurai from 150 years ago, don’t use it. It’s so low frequency that if you used it as a joke I doubt Japanese people would understand. But hey. You learned a cool new word.

The End!

I hope that this post helps you choose the pronoun that fits you best. ♡

#moderately interesting Japanese#personal pronouns#study japanese#japanese#japanese language#learn japanese#kanji#study kanji#learn kanji#ask me anything#answer#first person pronouns#JLPT#jlpt n5#jlpt n4#jlpt n3#jlpt n2#jlpt n1#n5 vocabulary#n4 vocabulary#nihongo#japanese vocabulary#japanese vocab#japanese history#japanese culture#japanese linguistics#samurai#asks are open#anime#manga

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

I was told that grell has "outbursts of masculine speech" in the manga...whatever that means.

Dear Anon,

At risk of sounding rude, I hope whoever told you that is not aiming for a JLPT1-certificate…

In the manga, Grell’s speech is not demure or calm (traditionally feminine qualities) in the slightest. As such, the ‘outbursts’ are one of unconstrained energy, not masculinity.

The femininity in Grell’s speech is very, very consistent throughout the entire manga (after she has dropped her role as the male butler, of course). I could therefore take photographs of the entire manga, but this one text-balloon itself is already a rather perfect sum-up of her speech. I shall go into more detail.

アタシだってアンタみたいなガキよりもっとイイ男としたかったワヨ!

ATASHI datte ANTA mitai na gaki yori motto II otoko to shitakatta WA YO!

I too would have wanted to do this with a much SMEXIER man than YOU, [YOU KNOW]!

As briefly touched upon in this post and this post, in Japanese, language is an exceptionally telling method with which speakers express their identity. While the latter post only discussed ‘formality vs informality’, the same goes for gendered markers.

Pronouns

Many of us are familiar with ‘Watashi - Boku - Ore’. Among the humongous list of 1st person pronouns, Japanese 1st person pronouns also include three hyper feminine ones: ‘atashi’, ‘warawa’ and ‘uchi’. As ‘warawa’ is incredibly old-fashioned and is only used by wives of lords, and ‘uchi’ is rather infantilised, only ‘atashi’ remains as a pronoun that may accurately represent a modern and sophisticated woman.

Similarly, ‘anta’, a feminine-coded version of ‘anata’ (you), is the 2nd person pronoun Grell consistently uses. ‘Anta’ is not used by speakers who wish to express masculinity or gender-neutrality.

Ending Particles

Though perhaps less widely known, Japanese is also punctuated with ending particles that helps the speaker express their identity. Among many others, feminine ending particles include ‘wa’, ‘yo’, and ‘wa yo’. Grell ends most of her lines with these ending particles. Other users of these ending particles include Madam Red, Nina Hopkins, Queen Victoria, Lizzie, and Irene Diaz.

Emphasis

Japanese uses three writing systems, Kanji, Hiragana and Katakana. Without going into details about the first two, the last, ‘Katakana’ is used to write 1. loanwords, 2. obscure negative connotations (sometimes ‘pimple’ or ‘brat’ for example are written in Katakana), or 3. to catch the reader’s attention. Number 3 is bit similar to CAPS LOCK. The feminine ending particles used by Grell are always written in ‘Katakana’.

The speech pattern Grell uses is known as ‘Onee Kotoba’, or **‘Tranny Language’, also briefly touched upon in this post. “Tranny/Onee” is of course a slur, but (trans)gender studies evolved very different in Japanese society, but 10 years ago there was a lack of accurate terminology, hence this offensive use of term.

The main difference between this so-called ‘Tranny Language’ and ‘feminine speech’ boils down to emphasis. Transwomen are not taken very seriously and still seen as ‘effeminate men’. It is likely that the greater emphasis originated from an attempt to ‘compensate’ for the speaker’s perceived masculinity. Nowadays the language has been more or less coined, and is more of a lingual statement. Hence: Grell’s use of language is to make a statement about her gender identity.

The ‘motto ii otoko’ or ‘SMEXIER’ in Grell’s line above is also an emphasised, very femininely marked use of language. (Do masculine-presenting English speakers use ‘smexy’ unironically??? Honest question. I am not 100% sure.)

TLN: ‘Smexy’ is not an accurate translation of ‘ii otoko’ (‘a good man’), but the connotation is what is important here.

For Comparison

As we are talking about this topic anyway, I wish to draw attention to Sieglinde.

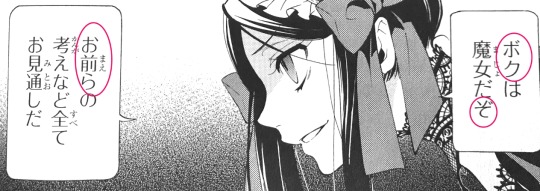

ボクは魔女だぞ お前らの考えなど全てお見通しだ

Boku wa majo da zo, Omae-ra no kangae nado subete omitooshi da

I am a witch, I have seen through all your thoughts.

In this post I mentioned Sieglinde’s use of language that defies gendered expectations. Many of us know that ‘boku’ is a traditionally masculine language marker. On top of using ‘boku’, Sieglinde also uses ending particles such as ‘zo’, or other markers such as ‘omae-ra’ (plr. you), as opposed to the slightly more neutral ‘omae-tachi’ or fully neutral ‘anata-tachi’.

Other markers are ‘tomaran’, as opposed to ‘tomaranai/tomarimasen’ (to stop). More strongly even, ‘iza!!’ (⇈ left), a masculine and almost military way of saying: “Alright!!”, or ‘美味い!‘ (umai・⇊ right), an incredibly ungraceful way of saying ‘delicious’.

How did Sieglinde come to use this speech? Considering how Sieglinde grew up in a village consisting of only women with one notable exception - Wolfram - the only way to explain this is that she learned talking from Wolf ❤🐺 Well, I think it’s cute and a small, meaningful addition to her connection with him (*´▽`*)ノ

BONUS!

In case anyone is interested in how gendered the use of language is by some of the characters on a scale from feminine-coded to masculine-coded. (I know, I know, gender is not a linear scale, but for lack of a better visual representation, a bar).

#Kuroshitsuji#Black Butler#Manga#Grell Sutcliff#Grelle Sutcliff#LGBT+#Transgender#Gender#Language#Japanese#Analysis#Sieglinde#Wolfram

707 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to say “I” in Japanese

わたくし (私) /watakushi/

Very formal.

PR professionals (CEO, politicians...) usually use it when making official announcements.

It may sound a bit arrogant to the listeners so you should avoid using this.

わたし (私) /watashi/

A shortened form of「わたくし」.

The most standard way to say “I”.

Gender-free but women tend to use it more than men.

If you don’t know what word to use,「わたし」 is the best choice.

あたし /atashi/

An informal form of「わたし」.

It’s generally used by younger girls and women to sound cuter and more feminine.

It is written in either Hiragana or Katakana.

「あたくし」 is a more formal form of「あたし」.

あたい /atai/

A slang version of「あたし」.

It’s originally used by women in certain red light districts and eventually picked up by those wanting to show a "bad girl" image.

People who use this are implied to be lower-class and uneducated.

ぼく (僕) /boku/

An informal, “soft-masculine” way for men (especially young boys) to adress themselves, but young or boyish girls sometimes use it too.

「僕」literally means “servant” so you could use it when you try to sound humble.

Be careful when using it with strangers, superiors or colleagues.

おれ (俺) /ore/

An informal, “hard-masculine” word that tough guys use.

It can be seen as “rude” depending on the context.

A very common way to say “I” in groups of men (except in formal settings).

おいら /oira/ - おら /ora/

Similar to「俺」, but more casual.

They convey a feeling of being from a low-class, rural area.

「おら」is more rural than「おいら」 and it’s a dialect in Kanto and further north.

うち (内) /uchi/

Informal and gender-free but women mostly use it.

It’s often used in Kansai dialect.

Women uses it when they wants to say an informal word without adding the cuteness like「あたし」.

こちら /kochira/ - こっち /kocchi/

It literally means “this way.” and can be understood as “we”.

「こちら」is highly formal and usually used in business, especially on the phone.

「こっち」is an abbreviated version of「こちら」and much more informal than the other, usually used between friends.

われ (我) /ware/

More common in plural form:「我々」/wareware/ (we).

It’s used in literary style and as rude second person in western dialects.

わし /washi/

A shortened form of「わたし」.

It’s often used in western dialects and fictional settings to stereotypically represent old men.

「わい」/wai/ is a slang version of「わし」in Kansai dialect.

*These are just some common pronouns to adress yourself, not all of them.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

“You” and “I” in Japanese

Different ways of saying “you”:

Informal:

君 (kimi): used by men toward people of lower status. Not rude.

お前 (omae): used in very informal situations or toward people of lower status.

あんた (anta): a shortened version of anata, highly informal and generally rude or admonishing in nature

Derogatory “you”:

kisama – きさま (貴様)

temee – てめえ (手前)

onore – 己

(don’t use these)

Also:

お主 (onushi): This is an old “you” word, not impolite but never used toward superiors.

お宅 (otaku) : Somewhat older “you” expression, but still used sometimes. This word is respectful in nature and shouldn’t ruffle many feathers. Note that this word not the same as that which refers to anime-loving オタク.

Different ways of saying “I”:

Watashi (私) : is the standard, gender-free way to say “I” and is the first one learners are introduced to. If you don’t know which I-word to use, this is your best bet.

Watakushi (私): This word is a highly formal “I.” You might hear politicians, CEOs, or other public-relations figures use it when making official announcements, but generally you should avoid this word as it can come across as arrogant or condescending.

Boku (僕) : is what you could think of as the “soft-masculine” I-word. It literally means “manservant” so when you use it there is a sense that you are humbling yourself before the speaker.It has a more informal feeling than watashi, however, so you may want to be careful when using it with strangers, authority figures and colleagues.

Ore (俺): If boku is the “soft-masculine” I-word then ore (俺) is the “hard-masculine.” This is the word tough guys use, and as such you would almost never hear it used with a polite verb form.

It’s not polite by any stretch of the imagination, but to say it’s a “rude” word would be a mistake as well. Ore can actually convey a sense of intimacy (we’re close friends, so I don’t need to worry about being polite with you). This is probably the most common I-word among groups of men (except in business or other formal settings).

Atashi: This is an informal effeminate form of watashi. It has a kind of “cute” nuance to it. Because kanji are generally seen as masculine, this word has no kanji form. It is written in either hiragana or katakana. (Well, the word does come from watashi so you might see it listed with 私 in a dictionary)

Uchi (内) : is one word for “I” that I didn’t learn until well after I came to Japan, but once I did I was surprised at how commonly used it was. It literally means “inside.”Saying uchi for “I” is informal and has no gender connotation. This is a good word for women to use if they want to be informal, but avoid the cuteness of atashi.

Kochira/kocchi: This is another popular and versatile way to say “I.” It literally means “this way.”While kochira and kocchi are the same word (kocchi is an abbreviated version), they differ pretty dramatically in how formal they are.

Kochira is highly polite and is often used in business situations, especially one the phone. Because of it’s root meaning of “this way” it is ambiguous in number, it can be used to mean “we” without any changes to the word.

Kocchi is much more informal and frequently used among friends. It’s also handy for its neutrality, meaning that when you use it you’re not making a statement about your social position relative to the listener (you are–however–still making a statement about social distance).

Ware: Used more commonly in it’s “we” form (我々/wareware), ware (我) by itself and meaning just “I” is pretty uncommon, but not unheard of.

It’s also probably the the most difficult I-word in this post because depending on how you use it it can come out not only as “I” but either as “one’s self” (not necessarily the speaker), or even “you” (although usage as “you” is very dated).

My impression of this word is it has a kind of wise, sage-like feeling to it. It’s almost always used in a short, declarative statement of some kind.

Washi: This is yet a further shortening of the word watashi. It is reserved for use by old men or men who for some reason have acquired a very slurred speech style. Perhaps they dropped the ta to keep themselves from spitting on people when they talked.

In the Kansai region, this I-word can be further shortened to just wai.

Personal name: While we don’t do this in English, in Japanese it’s possible to use your own personal name when saying “I.” Basically, you can speak in third person perspective. This manner of speaking is somewhat frowned upon as being childish, however, so be careful should you decide to use it.

Important side note! I got this amazing info from nihonshock.com.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

First person pronouns in Japanese

[Japanese - language - vocabulary - pronouns]

The words/structures of personal pronouns in Japanese are different from those in English.

You may have heard ‘watashi’ or ‘boku’ as the English equivalent for “I”. Actually, there are many words indicating “I” in Japanese and those vary by region and dialect.

私(わたし)[watashi]

Formal/informal – both genders

In formal or polite contexts, this is gender neutral but usually perceived as feminine when used in informal or casual contexts.

私(わたくし)[watakushi]

Very formal - both genders

The most formal and polite form.

我 or 吾(われ)[ware]

Very formal - both genders

Used in literary style. Also used as rude second person in western dialects.

僕(ぼく)[boku]

Informal - males

Commonly used by males.

俺(おれ)[ore]

Informal - males

Frequently used by men (not little boys). It can be seen as rude depending on the context. Establishes a sense of masculinity. Emphasizes one's own status when used with peers and with those who are younger or who have less status. Among close friends or family, its use is a sign of familiarity rather than of masculinity or of superiority.

おい [oi] = “ore” in the Kyushu dialect.

儂(わし)[washi]

Formal/informal - mainly males

Often used in western dialects and fictional settings to stereotypically represent characters of old age.

わい [wai] = “washi” in the Kansai dialect.

自分(じぶん)[jibun]

Formal/informal - mainly males

Literally "oneself". Originally a military term. Also used as casual second person in the Kansai dialect.

あたし [atashi]

Informal - females

Often considered cute. Common in conversation, especially among younger women.

あたい [atai]

Very informal – females

Slang version of “atashi”

あたくし [atakushi]

Informal – females

Slang version of “watakushi”

うち [uchi]

Informal – mainly females

Means "one's own". Often used in western dialects. Plural form uchi-ra is used by both genders.

おいら [oira]

Informal – mainly males

Similar to “ore” but more casual. May give off sense of more country bumpkin.

おら [ora]

Informal – both genders

Dialect in Kanto and further north. Similar to “oira” but more rural.

わて [wate]

Informal – both genders

Dated Kansai dialect.

わだす [wadasu] = “watashi” in the Tohoku dialect

あだす [adasu] orわす [wasu] = slang version of “wadasu”

おい [oi] orおいどん [oidon] = “ore” in the Southern Kyushu dialect

Mainly males

うら [ura] = the Hokuriku dialect

わ [wa] orわー [wā] = “ware” in the Tsugaru dialect

<old-fashioned> ---You may hear these in historical dramas or old novels

我輩 or吾輩 or我が輩or吾が輩(わがはい)[wagahai]

Rather arrogant

某(それがし)[soregashi]

Rather arrogant – mainly males (common in the Warring States period)

朕(��ん)[chin]

Only by emperor

麻呂 or 麿(まろ)[maro]

Mainly males

余 or予(よ) [yo]

Recently this is used by a ruler in historical dramas

小生(しょうせい)[shōsē]

Literary style - males

小官(しょうかん) [shōkan]

Humble language for government officers - males

吾人(ごじん)[gojin]

Literary style (rare) - males

愚生(ぐせい)[gusē]

Literary style/humble lanuage - males

非才(ひさい)[hisai] or 不才(ふさい)[fusai] or 不佞(ふねい)[funei]

Humble language - males

あっし [asshi] = from “atashi”

Used by ordinary people – both genders

あちき [achiki]

Vulgar word used by prostitutes in the Edo period – female prostitutes

わっち [wacchi]

Used to be a vulgar word for prostitutes in the Edo period. Also used by both genders in Mino dialect.

妾(わらわ)[warawa]

Humble word for lady’s maids – females

拙者(せっしゃ) [sessha]

Used by samurai.

僕(やつがれ)[yatsugare] or 手前(てまえ)[temae]

The plural form of ‘temae’, “temae-domo” is used in business occasionally.

此方(こなた)[konata] or 此方人等(こちとら)[kochitora]

Mainly used by samurai (males) and the nobility (both genders)

私め(わたしめ)[watashime] or(わたくしめ) [watakushime]

Humble language – female maids or people of low birth

…and more.

In books, we can tell the gender, occupation, class or hometown of characters from the word of “I” they use.

#japanese#language#vocabulary#first-person pronoun#self#watashi#boku#ore#english#subject#calan-coloan-japan

0 notes