#or anything that purports as nonfiction

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Me trying to figure out where all of my friend's suddenly alt right ideology is coming from 🤝🏻 she tells me her cis het boyfriend has been playing political podcasts in the car on drives for his job that she partakes in.

Me: ah shit.

#listen#listening to podcasts is fine in fact you should#but im willing to guess if you're listening to them on drives#you probably arent fact checking anything being said#PLEASE FACT CHECK#just because its a podcast#or documentary#or anything that purports as nonfiction#does not mean it is not taking data and skewing it for their narrative#or just outright lying to you#please do your own research#trying to explain that even if there are bathing suits in target for children that are made to allow for tucking#that its not a bad thing because that extra fabric has a lot of important uses that go beyond trans people#shes literally queer but some of the shit she says is starting to be really transphobic#and im trying so hard to be patient and course correct her

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Books recs on Alexander? And also any books to avoid? I've read the Robin Lane Fox biography but that's it.

ooooh I love this question. A lot depends on what kind of stuff you want to read about (military history? sexuality? politics? greater context of the era? history of Macedon in general? biography of Alexander specifically? focus on Hephaestion? Olympias? etc.), but here are some general nonfiction recommendations from my shelves*:

Alexander of Macedon, 356-323 B.C. (Peter Green). If I had to recommend one single book it would be this one; Green’s writing is factual, engaging, entertaining, and well-contextualised. The book is delightfully bitchy at times, and appropriately sober at others. Only real downside is that Green doesn’t much care for Hephaestion, but he doesn’t let that opinion get too intrusive when discussing Alexander’s relationship to him.

Alexander the Great (Robin Lane Fox). You already read this one but it’s a classic so I’m sticking it on the list again anyway.

The Search for Alexander (Ibid.). Similar to his other book, but with the cool benefit of his having re-traced Alexander’s footsteps as closely as possible.

Brill’s Companion to Ancient Macedon: Studies in the Archaeology and History of Macedon, 650 BC - 300 AD (ed. Lane Fox).

The Landmark Arrian: The Campaigns of Alexander (ed. Romm, Strassler). This is by far my favourite edition of Arrian’s writing on Alexander, primarily because of the contextualising information.

The History of Alexander (Quintus Curtius Rufus). There are various English-language translations available; I prefer the Loeb editions.

The Life of Alexander (Plutarch). Again, I like the Loeb translations, but most English-language translations of Plutarch are acceptable.

Alexander the Great (Paul Cartledge).

Alexander the Great (Ulrich Wilcken).

Alexander the Great (Richard Stoneman).

Alexander the Great (Philip Freeman).

Alexander and the East: The Tragedy of Triumph (A.B. Bosworth). Pretty much everything by Bosworth is good in my opinion.

Responses to Oliver Stone’s Alexander (ed. Cartledge, Greenland). Very much a mixed bag, but a lot of really cool historical information about specifics aspects of Alexander’s time that might not be covered in straightforward biographies, e.g. typical fashion of the time period.

The Conquests of Alexander the Great (Waldemar Heckel). Most writing by Heckel is good, and recommended.

Dividing the Spoils: The War for Alexander the Great’s Empire (Robin Waterfield). Focused more on the aftermath of Alexander’s death, but interesting nonetheless.

The Nature of Alexander (Mary Renault). Some (myself included) would call it outdated, but Renault’s classic biography is just a really enjoyable read regardless. The appendices she adds to her Alexander novel trilogy, especially the first book (Fire from Heaven), are also lovely.

*By this I mean these are all books I own and have read multiple times.

To avoid: Anything by Richard A. Gabriel; anything by E.A. Wallis Budge; anything sensationalising Alexander’s death (e.g. claiming that he was poisoned and this new book explains all about how and who was to blame); most books or articles published before 1975; anything basing itself on the premise that Alexander was an unpopular or generally incompetent ruler (you can pick out these books easily by eschewing anything with a title like “Alexander the Great... FAILURE” or similar — a real work by John Grainger); Alexander the Great: His Life and His Mysterious Death by Anthony Everitt... a book so knowledgeable about Alexander that it uses a bas-relief of Scipio Africanus on the cover instead of one of its purported subject. Yes, that is a real thing that this book does.

Anyway, I hope that helps! I only provided books in English (excluding the Latin/Greek original texts obviously) because you asked in English, but I can also recommend some books in French and German. If any of these books aren’t available in your region, just send me an ask (off anon, please) and I’ll be more than happy to provide you with a PDF or EPUB copy on request.

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Curious as to what Jean Berenson's opinion on A-Town would be, and if she has ever been asked to write for it, maybe in a crossover episode with a show she is working on?

[For everyone just tuning in: A-Town is my idea for a shitty postwar sitcom inspired by Jake Berenson’s life.]

Honestly, Jean would never. The problem with her having anything to do with A-Town is that then it lends the show too much legitimacy. It would be like when King Kong trumpeted about having consulted with Jane Goodall and Fay Wray all over its marketing materials. It'd be Full Metal Jacket making its whole press tour about how all its actors got a week of Army training, for realsies. It'd be Titanic hunting down the three octogenarians who survived the wreck as infants and trying to parade them at the premier. So on and so forth.

And to be clear, the team from A-Town has most certainly tried to get Jean to write or consult or at minimum comment on the show. They know that it'd be absolute gold to get one of their real-life inspirations to comment on their stupid crappy show. That's part of why people are even bothering to hound Tom (who isn't even famous outside of being Jake's brother) for comment. That's also the only reason anyone bothers to air his comments, even though said comments have to have the awkward pauses edited out and must always be subtitled with "Tom Berenson (real life inspiration for Daisy A) (not Visser Seventeen)".

Jean is totally, utterly silent on the subject. Like Jake, she loathes and abhors that show. Unlike Jake, she has a grudging respect for the industry being what it is, trite nonsense and all. Like Tom, she can appreciate that A-Town is not nearly as bad as the historical fiction blockbusters that purport to be The Untold Story of the Animorphs, because unlike the blockbusters it's not implying the lie that it's nonfiction. Like Steve, she has moods when she's willing to get wine-drunk and binge-watch a few episodes, falling off the couch laughing at the inaccuracies. Like Steve, there are times when she finds the whole concept so upsetting she can't even think about it.

But all the public's ever getting out of her is "no comment."

#animorphs#a-town#jean berenson#animorphs meta#postwar headcanons#hollywood bullshit#lies; damned lies; and 'based on a true story'#the animated titanic musical with singing rats is inoffensive by comparison#the titanic live-action movie actively damaged the reputations of several people who gave their lives evacuating the ship#give me singing rats any day

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

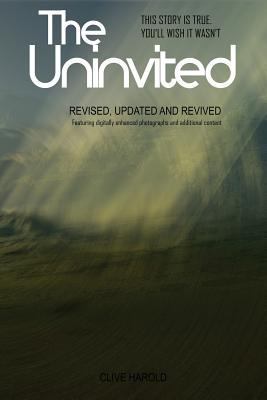

The Uninvited - Clive Harold Review

The Uninvited by Clive Harold purports to be nonfiction book about a series of UFO events that happen in the lives of the Coombs family, primarily on their farm in 1977. It begins fairly innocuously strange lights in the sky, malfunctions in electronics in their house. Then it begins to escalate; their cows show up multiple times in a neighboring farmers field, despite them being unable to find a single hoof print or human print around the cows that would indicate someone would have moved the cows. And it escalates to a direct encounter with extra terrestrials. So The Uninvited is a super interesting book to me. I think it was good. It's a good horror story, regardless of whether or not the events described are true so if that's what you care about, then I highly recommend this book. It's a creepy book. Chilling events happen. What I want to primarily talk about is whether or not the case of the Coombs family *is* true. When I'm writing my reviews, I try to do like at least a smidgen of research about the book to make sure none of the information I'm giving out is not factual. Looking up The Uninvited, any smidgen of information about this case, would lead back to this book. Which is interesting to me, because in the back of the edition of the book I read, there's a section where Clive Harold talks about interviewing the family, so clearly the primary source that Harold relied on is the Coombs family. As a nonfiction book, if The Uninvited is that, I found the book really, really lacking. There is no sourced information. None. Zero. Supposedly policemen in the area investigated these events, there's no interviews by the author with these policemen. The area is said to be a hotbed of UFO activity, with tons of other people around the area supposedly saw similar events and with rare exception, the book seems uninterested in that. I guess what I'm trying to say is there's no corroboration of the Coombs family, we're just supposed to take them at their word. Trying to find information about the case online, leads you back to The Uninvited. Every. Single. Place. I. Looked. Google. Bing. YouTube. Amazon. Goodreads. UFO sites. You name it. I want to take this a step further. Looking into the author, Clive Harold, correct me if I'm wrong, I'm more than willing to be corrected on this. I can't find anything about the author that doesn't directly tie back into this book. He was supposedly a journalist, but there's no articles or anything online written by him, every single shred of information I could find about this Harold led me back to The Uninvited. Which leads me to my conclusion, I think Clive Harold is a pseudonym for someone and that The Uninvited is a fictional story. Maybe based on an article or something that this person read, that's cool, that happens all the time. Authors, myself included, see something, are inspired and write an idea. I'm not even mad thinking this is a fictional story, because as I said, it's a creepy horror story and "based on a true story" was all the rage back in the 1970s (Texas Chain Saw, Amityville). It *just* feels to me like if this story were true, there'd be more interest because the claims in it are so extraordinary. More investigations into what happen that don't lead back to The Uninvited. There's way more detail than other cases like probably the most famous UFO case, the UFO crashing near Roswell. Right down to what individual members of the Coombs family were thinking years previous. I don't know about you, but I can't remember *exactly* what I was thinking two minutes ago while I was writing this. So do I recommend The Uninvited? Yes. With the above in mind. As a fictional UFO horror story, it's one of the better ones that I've read. There's some chilling ideas in here. And hey, if I'm wrong, then I'm wrong and am willing to be proven wrong. If I'm wrong and this *is* a true story, then it's even more terrifying than I previously thought and I think the *possibility* of it being true makes it a worthwhile read.

4/5

#halloween reading 2023#horror#horror fiction#horror nonfiction#the uninvited#clive harold#ufology#ufo#unidentified flying objects#unidentified aerial phenomena#uap#coombs family#coombs#extra terrestrial#aliens#men in black#wales#farming#texas chain saw#amityville#roswell

1 note

·

View note

Note

thank you for your answer, that was very helpful! can i ask another stupid question - what is the difference between a book and a novel? thank you so much for taking the time to answer my questions by the way!!

Aha, well, at the risk of stating the obvious, a book is that lovely square paper thing (or these days, e-format file) that is about any topic, any genre, fiction or nonfiction, so on and so forth. It only refers to the physical format of the media, as compared to, say, a TV show or movie or podcast or newspaper or magazine or anything that’s not a book. It is by anyone about anything and just tells you what shape that particular narrative comes in. But anyone can say they’re writing a book, no matter what that is -- because, well, that’s what they’re doing, or at least how they intend it to look when they’re done.

A novel, on the other hand, is a specific type of book, i.e. fiction. It’s most often used to denote literary or more “serious” fiction (which is elitist, but ANYWAY). When you open a book and see “a novel” underneath the title on the front page, that means a) it’s fiction, and b) it’s the sort of thing that would usually be shelved as General or Literary Fiction. Clearly “genre” books, like mystery, fantasy, science-fiction, horror, etc, don’t usually have to describe themselves as novels, because it’s clear from a glance at the cover of Godzilla shooting laser beams at spaceships or whatever’s going on there that it’s obviously a fantastical/fictional story. But we can still describe these as “mystery novels,” “fantasy novels,” “sci-fi novels,” and so on, because once again, it’s a reference to the format. It’s describing the fact that the story within is a product of the author’s imagination and not a non-fiction/factual account of something that happened in the real world. In the case of some genres of books, such as autobiographical/memoirs/partially based on a true story, that can get blurred, which the author sometimes discloses and sometimes does not. See for example the A Million Little Pieces controversy a while back, in which a best-selling memoir by a guy named James Frey, purporting to be an entirely truthful account of recovery from drug addiction, turned out to be substantially faked or fictionalized in parts. The publisher defended it on grounds that it still told a valid story, iirc, but the fact that he presented it as a truthful account when it wasn’t really touches on a whole other can of worms about literary merit, expression, expected pretense of truth, authorial responsibility, and so on. It seems like a practically more innocent age in the Land of Fake News we live in now.

If you say that you’re writing a novel, you just mean that you’re writing a fictional story, and you can add a specific description or type of story if you want, but once again, you don’t have to. Literary fiction tends to mean “realistic” fiction, or that dealing with stylized or abstract themes or consciously constructing itself in a way that the writing is as much part of the book as the story, or otherwise presenting itself as something that it is of intellectual merit to read. Whereas genre fiction gets a bad rap as being “less serious” literature, which again is total nonsense in my very humble opinion, because clearly if you just read a book because you like the story and want to have fun, INTELLECTUALISM DONE INCORRECTLY. (This concept would also be familiar to the Tumblr Purity Police, in which you can never enjoy anything that might be slightly Problematic, and must only consume media that fits that kind of narrow self-righteous moral worldview and Shun those who do not.) Which... come on, guys. Every sane person reads one kind of books because they want to learn things, and another kind of books to enjoy themselves. (There is another large strain of people who never read books at all, but we don’t trust them). But anyway. I DIGRESS!

This is changing as genre fiction becomes more mainstream, and pretty much every major cultural property on film or TV is based in some part on something with genre elements (superheroes, fantasy, dystopia, etc etc). Once again, I feel like I have rambled away past what you were actually asking and/or need to know about, but hopefully that was helpful.

I just really love books, okay.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Goodreads interview with Seanan McGuire

Author Seanan McGuire is the busiest person you know, even if you don't know her yet. She's that busy. McGuire has 33 novel-length works currently listed on her bibliography page, and that's not counting her pseudonymous acquaintance, Mira Grant. Scroll down and you'll find short fiction, essays, comics, nonfiction, and poetry. The crazy part? She didn't turn to full-time writing until about three years ago. Along the way, McGuire has won several marquee book prizes, including Hugo and Nebula awards for speculative fiction. Her series of fantasy novellas Wayward Children was recently picked up by the TV network Syfy for development. McGuire's brain is clearly a restless explorer, and her ambitious new novel, Middlegame, maps out another enormous chunk of notional real estate. In the new book, a pair of separated twins named Roger and Dodger endeavor to solve a series of increasingly sinister mysteries. Why were they separated? Why are they being hunted? Why are they developing world-breaking powers? And perhaps most importantly—why did they get such ridiculous names? The brother-and-sister team find themselves squaring off against a cabal of eldritch predators who have cracked the ancient code of alchemy, the missing link between science and magic. Speaking from her home outside Seattle, McGuire talked with Goodreads contributor Glenn McDonald about the new book, the weird science of alchemy, and the curious case of the prescription typewriter… Your bibliography is really astonishing. Are you just writing all the time? Seanan McGuire: Well, I'm not writing at the moment because I'm talking to you. But yeah, I was writing right up to the point where my phone rang. That's pretty much my life, because I am a workaholic and I enjoy what I do. GR: When did you make the leap into full-time writing? SM: I made the transition around January 2016, I think. The best advice I ever received from anyone, about professional writing, was from Todd McCaffrey. He said: Don't quit your day job until you're reasonably sure you can pay your bills off of your royalties. My last job was for a nonprofit, and I was basically sick all the time because I was writing all these books and I was still working a full-time day job. My friends never saw me. Like, never. Then the ACA happened, the Affordable Care Act. I don't think people realize what a difference that made, for all of us that work in the creative fields, to be able to get affordable insurance. I kept my day job for a few years after I strictly had to, just because I was terrified of dying under a bridge. The attacks on the ACA that are happening now are terrifying. Genuinely terrifying. Especially if they take away the protection for preexisting conditions. GR: Were you into writing as a little kid?

I was. I did not figure out that writing was an option until I was about three. I started reading before I was talking, really. Then I started getting migraines because I was trying to write, but I didn't have the physical coordination to actually write at the speed that I could think. So the doctor prescribed a typewriter. Really. My mom went to a yard sale and got me this gigantic thing. It weighed more than I did. I started writing stories. At the beginning, they were all very factual. I would write stories about going to look for my cat. A lot of my earliest work was what we would classify as fan fiction now. There were a lot of adventures with My Little Ponies. The thing about being a genius when you're a kid is that you grow out of it. I was perfectly average by the time I hit school. But there was that brief, frustrating time when I was so far ahead of where they wanted me to be that they just didn't know what to do with me. I would write until 3 a.m. on my typewriter, which sounded like gunfire. GR: There seems to be some of that experience in the new book, with the child prodigies Roger and Dodger. Their relationship is fascinating; it's a sibling thing but also this deeper connection that suggests they're resonating on the cosmic level. SM: I love that this is my best-reviewed book so far and it's about characters with intentionally terrible names. It's a delight to have people have to try to talk seriously about the relationship between Roger and Dodger. It's terrible, and it makes me so happy. Roger and Dodger really are soul mates because they are functionally the same person. They're one person split into two to embody the Ethos [the alchemy formulation sought after in the story]. I don't think that's a huge spoiler; that's basically the premise of the book. We know that, but they don't for a good part of the story. Locking down their relationship, a lot of that was looking at my own relationships with my siblings and the places where it's good or weird or awkward. GR: For readers who might not be familiar, what do we mean when we talk about alchemy? SM: Alchemy is sort of like magical chemistry. It's this idea that you can transform parts of the world into other parts of the world. You just have to figure out the right combination of elements. The classical example is lead into gold. But alchemists also believed that there were spirits and such that could be called upon to help with these processes. It has some of what we might call sorcerous ideas. They were trying to find the magical formulae for these things, like the panacea, which is the cure for everything. Or the alkahest, which is the universal destroyer, a fluid that could dissolve literally anything. Then there's the Philosopher's Stone, which was said to give eternal life. Harry Potter fans are probably familiar with alchemy, more than previous generations, because of the character Flamel, who was an actual and quite famous real-world alchemist. GR: Did you research the actual history of alchemy?

Yes, this was the first time I really jumped into it. I did a lot of research, and research makes me so happy. I hunted down every book I could find on alchemy; they're all downstairs in the library now. Alchemy was a real thing, even if it never worked, even if they never turned lead into gold with these processes. Really smart people spent a really long time trying hard to make these things happen. I wanted to make sure what I was trying to do would fit into at least one school of alchemical thought—and there were many, many schools of thought. Alchemy sounds a little ridiculous now, but there was a time when it was a commonly accepted belief. GR: In the book you have a great villainous force in the Alchemical Congress, who are modern practitioners of the ancient art. They reminded me of historical groups that purported to be keepers of secret knowledge, like the Masons. SM: Right, or like the Order of the Golden Dawn. I never found a specific historical analog to that in alchemy, but maybe that's because they never got it to work. My Alchemical Congress is a group of people who can actually say that alchemy works. They're able to do all kinds of ethically negotiable things. With that kind of power, you're absolutely going to have a group that locks it down so it stays in what these people consider the right hands. GR: The cover image of the book depicts a delightfully creepy magical item known as the Hand of Glory, which also has a historical basis. Do you recall when you first came across that? SM: I feel like I've always known. I don't remember where I first read about that. I studied folklore in college, and the Hand of Glory was very common in certain parts of Europe. It's amazing. Everyone was chopping hands off for a while there. GR: When did you actually start writing Middlegame? SM: Middlegame is kind of unique. I'd been thinking about it for ten years, but it took me a while to develop the technical skill to tell the story and have it make sense to people who don't live inside my head. My brother must have heard me explain this story 90 times before I even sat down to write it. At this point in my career, I have the enviable problem that, for the most part, I don't get to just sit down and decide that I'm going to write. Everything has been pre-sold. I'm working off contracts until 2023. So I know exactly what I'm going to be writing every day when I get out of bed. GR: Don't you ever just get burned out? SM: Well, I think I'm dealing with ten years of systemic burnout because I'm exhausted all the time. But if you mean: Do I ever get to the point that I can't write? Thankfully, no. I think everybody's wired differently that way. So much of my storage space is devoted to people who don't exist. There's a certain concern that if I leave them alone, those parts of my brain will go offline. GR: There are fictional lives at stake! SM: There are! You don't depend on me for your persistence of existence. If I forget about you, you'll still be fine. GR: Your series Wayward Children was just picked up for development with the Syfy channel. Is there anything you can disclose about that? SM: No, not really. For the most part, for myself and other creators, we can't disclose anything because they don't want to let us know what's happening. We have family members that are going to ask, and they don't want us to be the leaks and endanger the production, so we're frequently not told things. I've basically just sold them my canvas, because I'm a wee baby author from the perspective of Hollywood. I have no properties under my belt, I have no track record. There's not a lot of bargaining power on my side of the table. But I trust the people that are involved in this project. And even if I didn't, honestly, television changes everything. The worst show that absolutely butchers my concepts—which is not a thing I'm expecting with this team at all—but the worst show in the world is going to be seen by more people than have read the first book. So that bumps my book sales, almost guaranteed. That sounds very mercenary, I'm sure, but that's just the math of it. Jim Butcher, Charlaine Harris, even Neil Gaiman—they weren't household names until they got something on TV. My mother raised three daughters on welfare, and she lives with me. I'm basically her sole support. I worry fairly regularly about what would happen if I get hit by a bus and can't write anymore. But what happens with a successful TV show—or even a failed TV show—is that my mom lives off my royalties for the rest of her life. GR: This is a question we've been polling authors on: When you read for pleasure, do you read one book at a time or do you have several going at once? Some people say it's insane to read multiple books at the same time, but I usually have two or three going. SM: Well, I'm currently reading six. GR: Is there anything else you'd like to highlight or discuss about the new book? SM: Middlegame is currently a standalone, but there are two follow-ups I'd really like to write, so please buy Middlegame from your local bookstore so that my publisher will let me continue!

#fucking awesome!!!#love this author#love that they're finally getting some wider recognition#love love love#seanan mcguire#mira grant#goodreads#syfy#scifi#scifi-fantasy#fantasy#recommended books#recommended#middlegame#newsflesh#roger dodger#charlaine harris#neil gaiman#todd mccaffrey#aca#preexisting conditions#vote#obamacare#insurance#freelance#book to tv#book to movie#book series#horror#mythology

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey gang, rec me gossipy historical reads! I’d love works purporting to be nonfiction, works about marginalized folks in history, and/or works centering on historical women, but I’m down for just whatever is thrilling/trashy/FULL OF DRAMA. I’m going through Possets’ scents right now and all her historical bio blurbs have me really jonesing for in particular medieval and Early Modern goss. But I wouldn’t say no to anything from any time period. Think of those huge biographies of, like, Lucrezia Borgia and Cleopatra that you read in the bathtub in high school and got drippy fingerprints all over when you had to turn the page.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

January 8th- Day 6

I mean is there anything that describes me better?

I didn’t write anything yesterday because we didn’t really do anything very interesting yesterday, we all slept a lot and sat around on the couch. We did end up leaving the apartment eventually to do some shopping at this store called Flying Tiger Copenhagen which is basically the lovechild of a dollar store and Ikea and I want them to come to the states soooo desperately. I found a lot of really cute lunch container items that I will be shipping back to the states at the end of this because they are just the most ingenious little things. We also went to a crystal shop called Dervish which I spent quite a bit of time in trying not to make disparaging remarks about some of the purported “benefits” having these regular old rocks in your home was supposed to have.

Today was the first day of classes, and it wasn’t a bad day at that. I sat in on an Irish language class this morning that I really didn’t care too much for. It wasn’t too bad until we learned that there are 3 different dialects of Irish and each dialect has completely different ways of saying things. I thought that the different Spanish tenses were bad, but this is a whole other level. I do know the words for male and female, so I don’t have to worry about going into the wrong bathroom.

The second class I had was a writing class that I really think I’m going to enjoy, it’s all about writing nonfiction (travel writing, memoir, journalism) but in a creative way, which I think will be a very interesting thing to learn about. For our first assignment we are supposed to take a walk through the city and focus on our senses and what we see and hear and such. I’ve decided to take a walk up to either Iveagh Gardens or St. Stephens Green after class tomorrow because I would really like to explore some of the green spaces of this city.

Tomorrow night is also the Irish dance class, so I will make sure that I get some good pictures from that.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Horace Grant’s hatred of ‘The Last Dance’ isn’t his first beef with MJ

Photo by Nathaniel S. Butler/NBAE via Getty Images

This dates back almost 30 years.

Everyone is in love with The Last Dance renewing interest not only in Michael Jordan, but the entire 90s Chicago Bulls era. Well, that is, almost everyone. On Monday former Bulls forward Horace Grant blasted the documentary series, accusing it of being a one man show, among other things.

Appearing on ESPN Radio in Chicago, Grant re-ignited his long-standing beef with Jordan, saying that disagreeing with Jordan was tantamount to a death sentence due to MJ’s influence.

“It’s only a grudge, man. I’m telling you, it was only a grudge. And I think he proved that during this so-called documentary. When if you say something about him, he’s going to cut you off, he’s going to try to destroy your character.”

This isn’t a one-off situation, but rather the result of long-standing tension between the two that dates back almost 30 years.

The genesis of the Jordan/Grant beef comes from a book.

In 1993, at the height of Jordan’s popularity, Sam Smith’s book The Jordan Rules was published. It focused on strategies used by the Detroit Pistons during the 1990-91 NBA Finals to limit Jordan’s effectiveness on the court.

While the book was billed as basketball nonfiction, it also included numerous anecdotes purporting to have occurred with Jordan at the Bulls’ helm. This included alleging that Jordan punched Will Perdue, and intentionally threw hard passes at Bill Cartwright to expose him and break him down.

At the time of release Jordan’s teammates rallied around their star, saying the details in the book were fabricated. Stacey King called it a work of fiction, and Jordan himself said he’d laugh off the book and move on.

Behind the scenes things weren’t so smooth. It was Jordan’s belief that much of Smith’s information came from Horace Grant, which led to immense tension between the two. Grant left the Bulls in 1994 to join the Orlando Magic, the only team during the Jordan era to beat the Bulls in the NBA Playoffs. Grant and Jordan never mended their fences and continue to have an icy relationship to this day. The saying goes that “time heals all wounds,” but that was tossed aside Sunday night when Jordan referenced the release of the book, and re-ignited the beef saying:

“I didn’t contribute to that. That was Horace. He was telling everything that was happening within the group.”

Grant says that Jordan controlled the message of The Last Dance, which cast him as the villain in the scenario. While he acknowledges he had a close friendship with Smith, he vehemently denies he supplied the writer with details from the Bulls locker room. Instead, he turned the focus back on Jordan, calling him “a damn snitch” for discussing the rampant drug use he witnessed at a team hotel during his rookie season.

“My point is, he says I was the snitch, but still after 35 years he brings up his rookie year, going into one of his teammates rooms and seeing coke and weed and women. My point is, why did he want to bring that up? What does that got to do with anything? If you want to call somebody a snitch, that’s a damn snitch right there.”

Grant went on to allege that Jordan ostracized Charles Barkley and has’t spoken to him in years for criticizing how MJ runs the Charlotte Hornets.

Where does the beef go from here?

Neither producers of The Last Dance or Jordan have said anything about Grant’s claims about the series. It’s clear, however, that there’s a lot of bad blood between the former teammates, and from what we know about Jordan he won’t be the one to extend the olive branch.

Perdue, a player central to one of the most damning stories in The Jordan Rules said that Grant’s issue with Jordan was that he was forced to take a backseat to the phenomenon surrounding No. 23.

“As we started winning championships, and everybody talked about Michael, and everybody talked about everybody else, I mean that really pissed off Horace. He felt slighted. He was in Michael’s shadow.”

Grant and Jordan appear to have so much disdain for each other that they may never have a close relationship again. In time this beef will be pushed to the back burner once more, but it’s just waiting for the next occasion for the pair to take shots at each other and start it again.

0 notes

Text

Oh, and –

all the examples I've listed in this post are Nonfiction. Nonfiction portraying and encouraging hate and violence to varying degrees.

Non-fiction or nonfiction is content (sometimes, in the form of a story) whose creator, in good faith, assumes responsibility for the truth or accuracy of the events, people, or information presented.[1] In contrast, a story whose creator explicitly leaves open if and how the work refers to reality is usually classified as fiction.[1][2] Nonfiction, which may be presented either objectively or subjectively, is traditionally one of the two main divisions of narratives (and, specifically, prose writing),[3] the other traditional division being fiction, which contrasts with nonfiction by dealing in information, events, and characters expected to be partly or largely imaginary.

Nonfiction's specific factual assertions and descriptions may or may not be accurate, and can give either a true or a false account of the subject in question. However, authors of such accounts genuinely believe or claim them to be truthful at the time of their composition or, at least, pose them to a convinced audience as historically or empirically factual. Reporting the beliefs of others in a nonfiction format is not necessarily an endorsement of the ultimate veracity of those beliefs, it is simply saying it is true that people believe them (for such topics as mythology). Nonfiction can also be written about fiction, typically known as literary criticism, giving information and analysis on these other works. Nonfiction need not necessarily be written text, since pictures and film can also purport to present a factual account of a subject. (source)

Again, I am decidedly for Free Speech, but I've not seen an instance of antis giving a singular collective fuck about Nonfiction. I'm not claiming they don't care about anything not fiction ( – although, y'know). I'm stating very clearly that they're missing the one thing that quite clearly has a much more direct, more intense, and much less questionable effect on reality.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mountains between the Light and the World: On Walls and Greed and the Privilege of Isolation

[This essay was originally written for the Personal Essay prompt for @backtomiddleearthmonth, on the orange/nonfiction path. There have been some amazing comments on the original post here. It’s a personal essay, so it delves into my personal politics a bit more than I usually do in my fandom stuff.]

I've recently been rereading the early chapters of The Silmarillion, and the other day, I also read Lyra's thought-provoking story The Parting of the Ways, a conversation between Finwë and Morwë about the decision of the Avari to remain in Middle-earth. This line from Lyra's story sums up where my thoughts have been wandering these past few days:

"I do not doubt the splendour of the Blessed Realm," Morwë interrupted him. "It is, in fact, one of the things that rub me the wrong way. Why only there? If the Valar have the power to create such splendour, such light, why have they limited it to a secluded place? Does not the rest of the world deserve such light?"

I've always been bothered by the Silmarils: not that Fëanor had the audacity to make them but what they represent of the worst of human nature, carrying on a trajectory originating with the Valar, who were the first to covet and hoard light, a gift of Ilúvatar himself.

In The Book of Lost Tales 1, light "flowed and quivered in uneven streams about the airs, or at times fell gently to the earth in glittering rain and ran like water on the ground" (The Coming of the Valar). Like most of the details in the BoLT, this idea did not make it into the published Silmarillion, which conveniently skirts around the question of where the light in the Lamps came from:

And since, when the fires were subdued or buried beneath the primeval hills, there was need of light, Aulë at the prayer of Yavanna wrought two mighty lamps for the lighting of the Middle-earth which he had built amid the encircling seas. Then Varda filled the lamps and Manwë hallowed them … and the light of the Lamps of the Valar flowed out over the Earth, so that all was lit as it were in a changeless day. ("Of the Beginning of Days")

But the ubiquity of light after the making of the Lamps certainly echoes this early idea. Furthermore, in a late writing found in Myths Transformed (Morgoth's Ring):

Therefore Ilúvatar, at the entering in of the Valar into Eä, added a theme to the Great Song which was not in it at the first Singing, and he called one of the Ainur to him. Now this was that Spirit which afterwards became Varda (and taking female form became the spouse of Manwë). To Varda Ilúvatar said: 'I will give unto thee a parting gift. Thou shalt take into Eä a light that is holy, coming new from Me, unsullied by the thought and lust of Melkor, and with thee it shall enter into Eä, and be in Eä, but not of Eä.' . . . Now the Sun was designed to be the heart of Arda, and the Valar purposed that it should give light to all that Realm, unceasingly and without wearying or diminution, and that from its light the world should receive health and life and growth. Therefore Varda set there the most ardent and beautiful of all those spirits that had entered with her into Ea, and she was named Ar(i), and Varda gave to her keeping a portion of the gift of Ilúvatar so that the Sun should endure and be blessed and give blessing. (Section II)

This is a mishmash of sources, I know. But what unites them is the idea that light was initially (and ideally) supposed to be freely available to all of the world. It is also at least implied that light had a divine origin in Ilúvatar and was not a creation of the Valar.

What happens, then, to that divine light? Slowly, it is corralled into ever more restrictive spaces; slowly, it is reduced to the entitlement of the few rather than the right of all. Driven by fear, the Valar raise the Pelóri so that, behind barriers of safety, they might recreate what was lost. Afterward, "they came seldom over the mountains to Middle-earth, but gave to the land beyond the Pelóri their care and their love" ("Of the Beginning of Days"). The Elves awake in darkness and quickly learn the terrors of Melkor. When the Valar discover them, they are permitted access to the light only on the terms of the Valar. It is as Morwë asks in Lyra's story: "Why should we have to leave our ancestral home, forever? Why are we told to do it now or never? Why can we not choose at any time, or go back and forth as it pleases us?"

Because the Valar desire control and, with it, the illusion of safety it provides. But with this purported safety comes neglect, usually of the most vulnerable and in need of their aid. The later isolationist tendencies of the Eldar are instigated by this choice of the Valar: the sequestered, "protected" realms of Doriath, Nargothrond, and Gondolin. All of these realms achieve a high degree of splendor, often in explicit mimicry of Valinor, but at what price? Rarely do they contribute their share to the defense of Beleriand; instead, they rely on the Fëanorians, Fingolfin and Fingon, and the younger sons of Finarfin, as well as the native Sindar and Avari (and later Mortals and Dwarves) who do not dwell within these protected realms. These peoples bear the brunt of the assault of Morgoth (and very often the neglect or outright scorn of the chronicler of The Silmarillion is the thanks they receive). In all cases, there is a simultaneous fear and a desire to consolidate onto oneself and one's own the good things in life, to the suffering and exclusion of others.

This hits close to home, especially in an era where popular opinion would have us stop our ears against the suffering of others in the name of safety, when the naked need of the most vulnerable is not enough to stem the greed of the privileged, when nearly all of us succumb at times to the desire to wall ourselves in with the comfortable sound of our own views in others' voices. I doubt Tolkien intended this message, but as I've lately been rereading these texts, it seems all I can hear.

I've sometimes questioned my long-standing interest in the Fëanorians. I am an advocate for peace, and they hardly seem to represent my values in this regard. Pengolodh gives us an exhaustive list of their sins. But one thing they did not do is hole themselves up in the name of safety, nor did they ask others to fight their battles while they stood aside. Maedhros "was very willing that the chief peril of assault should fall upon himself "; if you look at a map of Beleriand, the open, exposed places most convenient for Morgoth's forces to access Beleriand were occupied by the Fëanorians. They took the most peril onto themselves. Thingol hated them, and yet for hundreds of years, their presence protected him.

As I said, I've always been bothered by the Silmarils. Perhaps that sounds contradictory. I am bothered by the impulse to put something that should belong to all into a form that can be possessed by the few. The Silmarillion concedes that "some shadow of foreknowledge came to [Fëanor] of the doom that drew near; and he pondered how the light of the Trees, the glory of the Blessed Realm, might be preserved imperishable"; his making of the Silmarils was perhaps a corrective to the original crime of raising mountains between the light and the world, not to mention the folly of the Valar in inviting the destroyer of the original Lamps to dwell within the safe bounds of those mountains. I am bothered also because, corrective or not, the Silmarils certainly don't allow a happy ending. Probably because a happy ending isn't possible. Once you take what is god-given and hoard it for the benefit of a few, how is envy, greed--how is darkness upon a swath of the world--not the inevitable result?

As an agnostic, I shy from proclaiming anything "god-given." But I do believe that all humans are born with the potential to leave this world better than they found it. Let's say this potential is the light. Let's say that it is shared freely upon all of the earth. What could we accomplish?

I sometimes say that anyone who suffers from disease, bad/stupid laws, inconvenience, the inanity of bureaucracy, anything really; who regrets that 21st-century technology isn't more like sci-fi authors imagined it'd be, should curse inequality. Imagine where we would be if all people had been able to contribute equally to solving the world's problems; imagine the genius minds squandered on picking cotton or scrubbing floors or knowing their place, minds that might have built and cured and innovated. Imagine what we could yet accomplish if we worked actively to grant all equal access to their potential.

Over the years, I've read eloquent defenses of the Valar, and I've tried to open my mind to such arguments. But I find I cannot because when they could have shared the light they'd been given, they hoarded it; when they could have risen to the defense of others, they largely hid away, more concerned for the safety of their pretty things than the lives of others, and if I am to expect more of myself, then I must expect more of the Wise. And this raises a big point that I think the narrator of The Silmarillion misses in his obsession over the ill-fated mission of the Noldor in Middle-earth: that at least they did something.

29 notes

·

View notes

Link

“I WANTED TO SAY something to you,” John Gilmore whispered to Charles Schmid Jr., who was sitting in front of him, alone, during a recess at Schmid’s murder trial in the Pima County courthouse. Schmid (who was known locally as “Smitty”) was accused of killing two Tucson girls, Gretchen and Wendy Fritz, though there was every reason to believe he’d also killed another teenager named Alleen Rowe. Gilmore, Schmid, and the bailiff were the only ones in the courtroom that afternoon in Tucson in 1965.

Schmid leaned back and Gilmore, who was then writing for the Los Angeles Free Press, quietly introduced himself: “I’m a friend of Lois Hudson’s.” (This was a friend of Schmid’s wife.) A bond would soon develop between the actor-turned-journalist and the accused killer, but Schmid’s lawyer, William Tinney, disapproved. “I don’t give a good God-damn if he’s a friend of Jesus Christ,” Tinney told his client. “You don’t say a word during the entire duration of this trial!”

The Charles Schmid case marked the beginning of one Los Angeles writer’s trip into certain dark caves of midcentury American insanity, which he would transform into a series of gonzo true-crime books and Hollywood memoirs. It was the moment when a handsome and promising young television actor named Jonathan Gilmore left Los Angeles and, in effect, disappeared — to be replaced by John Gilmore, nonfiction writer and firsthand witness to some of America’s gaudiest nightmares.

The author of Laid Bare: A Memoir of Wrecked Lives and the Hollywood Death Trip; Severed: The True Story of the Black Dahlia Murder; Live Fast-Die Young: Remembering the Short Life of James Dean; and The Garbage People, one of the first books ever written on the Manson case, seemed instinctively drawn to negatively charged individuals like Schmid, the so-called “Pied Piper of Tucson,” a talentless wannabe musician whose Manson-like hold over his teenage followers extended all the way to killing-for-fun. (Gilmore would later claim that when he first met Charles Manson in 1969, the latter recognized Schmid’s name and exclaimed, “I love the guy!”)

Not since the gory murder spree of James Dean–aping garbageman Charles Starkweather in the late 1950s had Americans been given such a fright as by the Charles Schmid case. It seemed to represent to Americans in 1965 a collision of everything gone wrong with kids-these-days: not just sex, drugs, and rock and roll, but full-on motiveless homicide. Charles Schmid himself was an oddball to beat oddballs, with his troweled-on pancake makeup, a fake rubber beauty mark on his cheek, and the crushed tin cans pounded down inside his boots for height. He dreamed of becoming a duplicate Elvis, “except I’ll be better.” It was all daydreams and fluff. He played tape recordings inside his amp while pretending to strum his guitar.

To John Gilmore, a 30-year-old of considerable experience in late 1950s Beat circles and in the worlds of theater and television, Schmid was something else: a charmer capable of getting people to do anything he wanted, whose antisocial, rock-hard psychopathy was masked by genuine charisma. Gilmore was enthralled.

Schmid, in turn, recognized the hepcat from Hollywood as someone he could relate to and trust. “Of all these old newspapermen, he singled me out,” the writer remembered, decades later. “Smitty would look over at me whenever there was a mistake or a discrepancy in the testimony: an arched eyebrow, a nod, or a pursed, mocking smile.” This was a meeting between two simpatico personalities, representing flip sides of the artistic outsider: one ambitious, dishonest, pathological and manipulative, the other ambitious, openly curious, and talented.

“He was a consummate actor,” Gilmore recalled. “He’d never get angry. He was always cool, calculated, just calmly telling you, in that very convincing and soft baritone voice of his, ‘where it’s at.’ Talking about the prosecutors, he’d say, ‘this is just more of their way of building a case against me…’ He never raised his voice. Nothing rattled him.” During a recess in the courtroom, Gilmore watched Schmid talking with Diane, his new bride, “his head sort of dipping, insinuating, and I could see her knees sort of getting weak under the chair, shaking.” Any actor, not just John Gilmore, might have frankly admired such a performance.

He was present later, on a windswept afternoon when Charles Schmid led sheriff’s deputies to the lonely spot in the desert near Tucson where Alleen Rowe’s skull and skeleton were found, tightly buried underneath dry, hard-packed dirt. “Tight where he buried her. Shallow,” Gilmore remembered.

¤

“Diane, the girl Smitty had just married, knocked on the door of my hotel room one day,” Gilmore told me in 2014. “At the door she said, ‘Smitty wants to see you.’” They drove to the Pima County Jail. There, behind glass, sat Schmid, who’d already decided to make Gilmore his personal manager: “I’ve already written 120 pages to give you.” Thus began Gilmore’s first business meeting (the first of many) with a murderer.

An agreement was reached. Thanks in part to his sudden ownership of Smitty’s writings, Gilmore was able to write his first true-crime book, The Tucson Murders (Dial Press, 1970). The book treats its readers to long, generous quotations from Schmid’s crazily verbose letters and his jailhouse musings, which carry a very special tang of ’60s kid slang: not just descriptions of his bitchin’ threads (“I sure miss decking out in my Continentals and vest and high-collar shirts like I used to, Baby”) but the sad delusions of his dreams of life after prison (“If this RCA audition falls through, I’ll try again and again and again until I prove I’m good enough to cut my songs. I know I can”). At its worst, the material is pop-psych schlock:

The uncertainties of tomorrow and the lost yesterdays add tangible fuel to my inner rebellion […] As I played and sang I projected sex with intent […] even the basic simplicity of my dancing became tainted with sexual suggestiveness […] Any mask I wear to disguise this becomes far more translucent and my carnal appetite becomes visible to the apparent embarrassment of my onlookers […] I truly wish I could be a great surgeon, or philosopher, or anything constructive, but in all honesty I’d rather turn my amplifier full-blast and listen to the noise until I’m enveloped.

(This reminds me that Gilmore later would mock the convoluted writings of Ed Wood, whom he had known both as a local Hollywood wino and a fellow paperback writer.)

¤

Like James Ellroy, another son of Los Angeles who grew up addicted to crime books, John Gilmore made no bones about his relentless pursuit of fame. The difference was, Gilmore started out in life more or less on the high road. His early ’50s friendship with fellow aspiring actor James Dean is a matter of public record (in most, if not all, Dean biographies). His interactions with the young Jack Nicholson and Dennis Hopper, as well as with such “successful losers” in Hollywood as Ed Wood, TV horror-hostess Vampira, and actress-turned-prostitute Barbara Payton (all highlighted in his book Laid Bare), naturally became grist for the mill of a writer who’d once worked for Confidential Magazine back in 1958.

As his own half-successful quest for movie stardom seemed about to peter out by the mid-’60s, Gilmore took the advice of a Broadway producer who told him “you’re not an actor, you’re a writer.” Years of churning out cheap paperbacks followed while he was living at the Hollywood Tower on Franklin Avenue (circa 1962–’65) and taking occasional acting jobs, mainly in TV Westerns. His close friendships with Dennis Hopper and avant-garde filmmaker Curtis Harrington during this period should have produced something, but didn’t; though thoroughly committed to “the art life,” Gilmore was never an avant-gardist himself. For him, the human condition was always the target.

When the Schmid story broke nationally, in late 1965, the young paperback writer from Hollywood was able to inject himself into the case without difficulty. His book doesn’t purport to solve the mystery of Smitty’s urge to kill, but the current reprint edition (retitled Cold-Blooded: The Tucson Murders and published by LA-based Amok Books) lets present-day readers enjoy its seedy, mid-’60s desert-town ambience, and the incredulous spectacle of a teenage girl’s strange willingness to help someone lure her “best friend” out of her bedroom one night, after that someone suddenly decided, “I want to kill a girl tonight! I want to see what it’s like, and if I can get away with it!”

¤

Gilmore is on record as stating that, in the 1950s, “if you didn’t want a business degree or want to get married, you were branded as an outlaw.” This chip on the shoulder against ’50s society seems to have cemented his personality (despite his pro-police sympathies; his father was an LAPD patrolman). He nursed lifelong obsessions for certain L.A. crime cases. To his peculiarly open mind, it was a short step from hanging out with James Dean to meeting in cheap bars with a shadowy skid-row character who may have killed the Black Dahlia.

A New York–based writer and filmmaker named Rémy Bennett, 33, has been working on a documentary about Gilmore’s life and work, to be titled L.A. Despair: Chasing Death with John Gilmore. She’s been fascinated by his books since childhood. “I was 13 when I pulled Severed off of my father’s bookshelf,” she remembers. “The story haunted and transfixed me with its sad and darkly beautiful telling of the life of Elizabeth Short, and the eerie atmosphere of 1940s Los Angeles that she inhabited.” Bennett would ultimately read through the entire shelf of Gilmore books, true crime and fiction, and come away fascinated by the writer’s own quixotic, “maverick” life: his relentless search for witnesses-to-the-crime and the damaged survivors of scandal, for the aging criminals, actors, and actresses he’d once known from the aborted movie career that might have been, had his luck run differently.

“Maybe he was too much of a loner himself to make it, in that collaborative world of acting,” Bennett wonders. As Gilmore himself boyishly put it in his Jimmy Dean memoir: “Other people had told me I was misanthropic…”

¤

In late 1969, Gilmore decided to head up to Death Valley and interview Charles Manson, recently arrested and being held in jail in the town of Independence. He snagged the interview, and was appalled by the spastic facial contortions and con-man jive this particular monster was spewing forth. “You can’t really have an exchange with Charlie. You are the target […] for a gamut of histrionics,” he wrote in the resulting book, The Garbage People:

He had the shuck down to a first-rate act. Charlie talked and talked […] and to give his ricocheting mental aberrations a little religious zing, he’d mouth half of what he said […] as cryptic parables: a seer whispering through his beard. But to an eye trained to the cages, it was philosophical mumbo-jumbo. Basically it did nothing more than clog like wax. To me, having repeatedly supped with the Devil, you might say, it is very understandable.

In an April 1971 newspaper article titled “Manson: Happiness Is a Cell,” Gilmore presented extensive excerpts from his interviews, most of which never made it into The Garbage People. Here, Charlie’s crackpot philosophy was laid bare:

If you want to get to people and unlock their minds the basic way you get to them is through fear […] I told Sadie to sweep the floor and make me a sandwich, because this is all a woman is for. That is why God put them here […] (then) I can get to her mind and get inside her soul, and body. The Black Muslims know the way, they’re ahead of us,” said the failed race-warrior. “Fifty years ahead of us, fifty years ahead. They know what’s happening. I turn them on because I’m the only white guy in here who knows about Mohammed […] I have no fear of dying. I’ll know where and I’ll know when it is my time. I’m going to lie down, put a little white tag on my toe with the name Charles Manson on it and then I’m going to lie down and die.

The attraction to this kind of darkness never left Gilmore, but he survived unscathed. “I never had the self-destructive urge,” he once said, unlike so many of his earlier Hollywood friends who would fall by the wayside: Sal Mineo, noir movie actor Tom Neal (I guess you could throw Ed Wood in here, too), and, of course, James Dean himself — “Jimmy had talked about Paris, but he never made it out of the country except to Tijuana to see the bulls.”

Looking back at his work when we spoke in 2014, Gilmore said that he realized his “unconscious intent” was always to insert himself into the books as he wrote them, whether fiction or nonfiction: “The creative artist is always part and parcel of what he’s doing; basically, it’s the world according to me. However that sounds, selfish or not, why should I let that be buried underneath?”

The days of having business meetings with murderers were over by then. He’d spent his 60s writing more books, was interviewed for European TV, and had to shrug it off when a proposed David Lynch movie, to be based on his Black Dahlia book, fell through. He was living in a large, book-filled house in suburban North Hollywood, though he had always dreamed of leaving Los Angeles and retiring to the desert. “I’m a committed indoorsman,” he once told me, over coffee and pancakes at Du-Pars.

John Gilmore died at the age of 81 on October 13, 2016, from leukemia. He no doubt shared his friend Jimmy Dean’s outlook on the afterlife, which he quoted in Live Fast, Die Young: “‘What bullshit!’ he said. There was no God, there was only art, only the composer, the creator of the symphony. ‘No matter what they say, there isn’t any heaven. There’s no hell either. There’s nothing before you’re born and there’s nothing after you’re dead.’” Gilmore’s two children spread his ashes somewhere in Death Valley.

At the memorial held for him at Hollywood’s Museum of Death, writers and L.A. historian-types as diverse as Kim Cooper of Los Angeles Visionaries Association, Stuart Swezey (his publisher at Amok), and filmmaker Richard Connor remembered the maverick who chucked a budding Hollywood career for the hinterlands of the American psyche. “He never compromised,” his son Carson told the assembled. “I’ve seen personal relationships go straight out the window, if it meant giving up what he knew he had to do.”

Rémy Bennett flew out from New York to attend the memorial. When we met at the 101 Coffee Shop on Franklin Avenue, she told me that Gilmore’s empathy for the “Black Dahlia,” Elizabeth Short, had moved her:

She became more than just a symbol of “L.A. despair” to me. I saw a young woman whose yearning I could identify with, and a spirit of tragedy that “echoed” in so many lives of people that were lost and searching in those days in Hollywood. John’s ability to get under the skin of his subjects speaks more to a collective sense of grief, and a desire to understand rather than exploit. Cold-Blooded, I think especially, should be mentioned in the same breath as Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood and Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song. But somehow he’s remained in the shadows as a cult figure, not the innovator of new journalistic crime writing that I think he deserves to be remembered as.

She envisions her work-in-progress as an impressionistic montage of period photos, quotes, and recordings of Gilmore’s writings, talks with surviving friends, and shots of those places conjured in his books, including the Hollywood rooming houses haunted by Elizabeth Short.

At the memorial, one of the actor-writer’s old friends got up to speak. He looked around and said simply, “Well, John was a solo act.” He deserves an encore.

¤

Anthony Mostrom, a former Los Angeles Times columnist, is currently a book reviewer and travel writer for the LA Weekly.

The post “Having Repeatedly Supped with the Devil…”: The Strange Muses of John Gilmore appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2MbG76u via IFTTT

0 notes

Photo

I half-expected George Saunders to look like a sunken-faced crystal-meth addict. I mean, what kinds of person dreams up stories like these? Even as a crazed teenager, high in high school in the Haight-Ashbury, my hallucinations weren't nearly as vivid and outrageous as Saunders' stories.

But Saunders showed no hint of being a strung-out, crazy person. He was an affable, congenial man with an open heart, who gladly answered questions about his work and shared his thoughts on writing.

Not only did I have the privilege of joining Saunders and a group of other writers for dinner before his reading, but I also got to introduce him at his reading. For a writing geek like me it doesn't get much better than that.

I want to fill you in on everything I learned from Saunders, but it's late and I've got to turn in. When I'm rested and fresh I'll dish more, but for now I'll leave you with my introduction speech, which just hints at the genius of George Saunders.

My first taste of George Saunders' writing was in “The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip,” his children's book. Here, parasites take the center stage. They come in the shape of bright, orange balls known as Gappers, that crawl from the shore and attach themselves to the village's goats, rendering the goats incapable of producing milk. One day the Gappers begin to attach to the goats of one girl, Capable, while leaving the neighbors' goats alone. Now Capable can't manage by herself. She asks for help. Unfortunately, her neighbors hadn't yet heard the phrase 'it takes a village.” Not only do they refuse to help Capable, but they take their new Gapper-less status as a sign they are better than Capable. Here's a quote from the book:"Not that we're saying we're better than you, necessarily, it's just that, since gappers are bad, and since you and you alone now have them, it only stands to reason that you are not, perhaps, quite as good as us." “The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip” is a fable that's entertaining, thought-provoking, and lesson-teaching. It opens a window for readers of all ages to look at the issues of justice, class, and dignity.

My next Saunders pick was “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline,” a collection of short stories and a novella in which many of the same themes thread. Sad-sack characters struggle to find safety and happiness in the alternate versions of a dystopic America. Saunders puts his characters in outrageous setups that force them to commit savage and heroic acts just to survive. Saunders characters are so compellingly flawed, so tender, and so human that I was riveted. One character, for instance, is a 400-pound man who becomes the head honcho at Humane Raccoon Alternatives – a business that purports to rid its clients of pesky racoons without inflicting suffering or bloodshed on the animals. In fact, no surprise here, we're in a Saunders' book, their methods involve nothing but suffering and bloodshed. Another character, this time from Saunders' novella, Bounty, has been branded a Flawed, and that's flawed with a capital F. He's a sympathetic, loving brother who tries to reunite with his sister. He fights the shame he feels as a result of his deformity, hideously clawed feet. How could anyone not fall in love with characters like these? Just as in real life, Saunder's characters straddle the fence – they have facets that are both beautiful and revolting. They always have an altruistic side, but sometimes, when they're pushed over the edge, they just might murder their bosses. Their struggle is the human struggle – that of believing they are valuable despite the outside messages that tell them otherwise. Saunders' stories take place in alternate realities that serve to highlight the absurdities of the world we live in today. But no matter where he sets his stories, Saunders' exuberant, wacky voice comes through loud and clear. Saunders' most recent offering is a departure from the rest – a collection of essays that still manages to capture the clear-thinking, bullshit-exposing voice of whimsy and vitality that gives his fiction its bite.

All the writers that come to Butler share their thoughts on the craft, but the ones who do so by opening up and sharing of themselves are the ones who remain with us. George Saunders was one of those authors. Here are some of his comments from the Q & A sessions from his visit. Saunders was asked about his background in geophysics and how this informs his writing. He answered that back when he first worked in the oil fields of Sumatra he read Ayn Rand and saw himself as a right-winger. But, as time went on, working in far-flung parts of the world served to open his eyes and reform his politics, and, naturally, this informs his fiction. About writing in general he commented that all our minds are similar, and that anything that manifests in the world has a presence in each of us. Saunders said that at one point in his life his worst fear came true: he had an office job. At that time he thought that in order to find stories he had to be in an exotic locale, but he soon realized that his boring office job was a blessing in disguise -- it showed him that stories were all around him, wherever he was. Saunders reported that after the birth of his second child he found himself able to allow humor into his work, and that bits of wisdom manifested as he wrote freely. He sought to emulate the clean, spare sentences of Barry Hannah and Raymond Carver, and convey his ideas using as few words as possible, even if the sentences lost some of their elegance. When asked what advice he would give aspiring writers he emphasized revision. He said any given piece of writing has infinite doors, and that a writer should live with a story a long time before sending it out. In this way, if the piece is rejected, at least the author can feel (s)he sent out his/her best work. Saunders revises obsessively, and he sees this same trait among other writers who succeed in publishing their work. Many pieces, he suggested, would improve if only the author let them sit awhile and then revisited them at a later date. Saunders emphasized how vital it is not to short-shrift revision. I asked Saunders about his recent move into the realm of nonfiction with "The Brain-Dead Megaphone," a collection of essays. He replied that he sees himself primarily as a fiction writer, that he's better at short stories than big ideas (I'm not sure I agree with him on this point.) He said his essay, The New Mecca, was written as an assignment for GQ, He joked that his daughter claimed he never did anything cool, so he accepted the job, and was sent to four-star hotels in Dubai. He feels his nonfiction work allowed him to more fully describe the physical world in which his writing took place. When I asked Saunders if the book's title essay most conveyed his essence, Saunders said yes, although he added that he thought the piece was preachier than he would have liked.

0 notes