#one holy catholic apostolic

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

This is why I am proud to be Catholic. I love my faith and I would never wish for myself to be born into another one.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Extraordinary Significance of the Royal Priesthood of Believers

This doctrine impacts every area of your life!

The apostle Peter makes a somewhat shocking declaration about the Christian life in the second chapter of his first epistle. Well, actually, he makes several fascinating declarations, but for now, we’ll mainly focus on one. With all its implications, contemporary Christians largely ignore this doctrine. The current religious atmosphere of flagrant biblical illiteracy probably explains why most…

View On WordPress

#Did Constantine invent the Trinity#Does God Care How We Dress#how are we a holy priesthood#how do we present our bodies a living sacrifice unto God?#how does the Bible define modesty?#how to be born again#is the trinity true#should christians dress modestly#what are spiritual sacrifices#what is a royal priesthood#what is christian ordination#what is the priesthood of believers?#what is the sacrifice of praise#why do catholics have priests?#why do pentecostals wear skirts below the knee#Why I am a oneness apostolic pentecostal not a Trinitarian#Why I&039;m not a Trinitarian

0 notes

Text

Okay so the small cock gods have apparently spoken my best friend sent this pic to me 🙏🏻 Catholics man we are a bunch of fucking deviants

1 note

·

View note

Text

[ID: First image shows four small porcelain bowls of a pudding topped with slivered almonds and pomegranates seeds, seen from above. Second image is an extreme close-up showing the blue floral pattern on the china, slivered almonds, golden raisins, and pomegranate seeds on top of part of the pudding. End ID]

անուշապուր / Anush apur (Armenian wheat dessert)

Anush apur is a sweet boiled wheat pudding, enriched with nuts and dried fruits, that is eaten by Armenians to celebrate special occasions. One legend associates the dish with Noah's Ark: standing on Mt. Ararat (Արարատ լեռը) and seeing the rainbow of God's covenant with humanity, Noah wished to celebrate, and called for a stew to be prepared; because the Ark's stores were diminishing, the stew had to be made with small amounts of many different ingredients.

The consumption of boiled grains is of ancient origin throughout the Levant and elsewhere in West Asia, and so variations of this dish are widespread. The Armenian term is from "անուշ" ("anush") "sweet" + "ապուր" ("apur") "soup," but closely related dishes (or, arguably, versions of the same dish) have many different, overlapping names.

In Arabic, an enriched wheat pudding may be known as "سْنَينِيّة" ("snaynīyya"), presumably from "سِنّ" "sinn" "tooth" and related to the tradition of serving it on the occasion of an infant's teething; "قَمْح مَسْلُوق" ("qamḥ masluq"), "boiled wheat"; or "سَلِيقَة" ("salīqa") or "سَلِيقَة القَمْح" ("salīqa al-qamḥ"), "stew" or "wheat stew," from "سَلَقَ" "salaqa" "to boil." Though these dishes are often related to celebrations and happy occasions, in some places they retain an ancient association with death and funerary rites: qamh masluq is often served at funerals in the Christian town of بَيْت جَالَا ("bayt jālā," Beit Jala, near Bethlehem).

A Lebanese iteration, often made with milk rather than water, is known as "قَمْحِيَّة" ("qamḥīyya," from "qamḥ" "wheat" + "ـِيَّة" "iyya," noun suffix).

A similar dish is known as "بُرْبَارَة" ("burbāra") by Palestinian and Jordanian Christians when eaten to celebrate the feast of Saint Barbara, which falls on the 4th of December (compare Greek "βαρβάρα" "varvára"). It may be garnished with sugar-coated chickpeas and small, brightly colored fennel candies in addition to the expected dried fruits and nuts.

In Turkish it is "aşure," from the Arabic "عَاشُوْرَاء" ("'āshūrā"), itself from "عَاشِر" ("'āshir") "tenth"—because it is often served on the tenth day of the month of ٱلْمُحَرَّم ("muḥarram"), to commemorate Gabriel's teaching Adam and Eve how to farm wheat; Noah's disembarkment from the Ark; Moses' parting of the Red Sea; and the killing of the prophet الْحُسَيْن بْنِ عَلِي (Husayn ibn 'Ali), all of which took place on this day in the Islamic calendar. Here it also includes various types of beans and chickpeas. There is also "diş buğdayı," "tooth wheat" (compare "snayniyya").

These dishes, as well as slight variations in add-ins, have varying consistencies. At one extreme, koliva (Greek: "κόλλυβα"; Serbian: "Кољиво"; Bulgarian: "Кутя"; Romanian: "colivă"; Georgian: "კოლიო") is made from wheat that has been boiled and then strained to remove the boiling water; at the other, Armenian anush apur is usually made thin, and cools to a jelly-like consistency.

Anush apur is eaten to celebrate occasions including New Year's Eve, Easter, and Christmas. In Palestine, Christmas is celebrated by members of the Armenian Apostolic church from the evening of December 24th to the day of December 25th by the old Julian calendar (January 6th–7th, according to the new Gregorian calendar); Armenian Catholics celebrate on December 24th and 25th by the Gregorian calendar. Families will make large batches of anush apur and exchange bowls with their neighbors and friends.

The history of Armenians in Palestine is deeply interwoven with the history of Palestinian Christianity. Armenian Christian pilgrimages to holy sites in Palestine date back to the 4th century A.D., and permanent Armenian monastic communities have existed in Jerusalem since the 6th century. This enduring presence, bolstered by subsequent waves of immigration which have increased and changed the character of the Armenian population in Palestine in the intervening centuries, has produced a rich history of mutual influence between Armenian and Palestinian food cultures.

In the centuries following the establishment of the monasteries, communities of Armenian laypeople arose and grew, centered around Jerusalem's Վանք Հայոց Սրբոց Յակոբեանց ("vank hayots surbots yakobeants"; Monastery of St. James) (Arabic: دَيْر مَار يَعْقُوب "dayr mār ya'qūb"). Some of these laypeople were descended from the earlier pilgrims. By the end of the 11th century, what is now called the Armenian Quarter—an area covering about a sixth of the Old City of Jerusalem, to the southwest—had largely attained its present boundaries.

Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, the Patriarchate in Jerusalem came to have direct administrative authority over Armenian Christians across Palestine, Lebanon, Egypt, and Cyprus, and was an important figure in Christian leadership and management of holy sites in Jerusalem (alongside the Greek Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches). By the middle of the 19th century, a small population of Armenian Catholics had joined the larger Armenian Apostolic community as permanent residents in Jerusalem, living throughout the Muslim Quarter (but mostly in a concentrated enclave in the southwest); in the beginning of the 20th century, there were between 2,000 and 3,000 Armenians of both churches in Palestine, a plurality of whom (1,200) lived in Jerusalem.

The Turkish genocide of Armenians beginning in 1915 caused significant increases in the populations of Armenian enclaves in Palestine. The Armenian population in Jerusalem grew from 1,500 to 5,000 between the years of 1918 and 1922; over the next 3 years, the total number of Armenians in Palestine (according to Patriarchate data) would grow to 15,000. More than 800 children were taken into Armenian orphanages in Jerusalem; students from the destroyed Չարխափան Սուրբ Աստվածածին վանք (Charkhapan Surb Astvatsatsin Monastery) and theological seminary in Armash, Armenia were brought to the Jerusalem Seminary. The population of Armenian Catholics in the Muslim Quarter also increased during the first half of the 20th century as immigrants from Cilicia and elsewhere arrived.

The immediate importance of feeding and housing the refugees despite a new lack of donations from Armenian pilgrims, who had stopped coming during WW1—as well as the fact that the established Armenian-Palestinians were now outnumbered by recent immigrants who largely did not share their reformist views—disrupted efforts on the part of lay communities and some priests to give Armenian laypeople a say in church governance.

The British Mandate, under which Britain assumed political and military control of Palestine from 1923–1948, would further decrease the Armenian lay community's voice in Jerusalem (removing, for example, their say in elections of new church Patriarchs). The British knew that the indigenous population would be easier to control if they were politically and socially divided into their separate religious groups and subjected to the authority of their various religious hierarchies, rather than having direct political representation in government; they also took advantage of the fact that the ecclesiastical orders of several Palestinian Christian sects (including the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem) comprised people from outside of Palestine, who identified with religious hierarchy and the British authorities more than they identified with the Palestinian lay communities.

British policy, as well as alienating Armenians from politics affecting their communities, isolated them from Arab Palestinians. Though the previously extant Armenian community (called "քաղաքացի" "kaghakatsi," "city-dwellers") were thoroughly integrated with the Arab Palestinians in the 1920s, speaking Arabic and Arabic-accented Armenian and eating Palestinian foods, the newer arrivals (called "زُوَّار" / "զուվվար" "zuwwar," "visitors") were unfamiliar with Palestinian cuisine and customs, and spoke only Armenian and/or Turkish. Thus British policies, which differentiated people based on status as "Arab" (Muslim and Christian) versus "Jewish," left new Armenian immigrants, who did not identify as Arab, disconnected from the issues that concerned most Palestinians. They were predominantly interested in preserving Armenian culture, and more concerned with the politics of the Armenian diaspora than with local ones.

Despite these challenges, the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem came to be a vital center of religious and secular culture for the Armenian diaspora during the British Mandate years. In 1929, Patriarch Yeghishe Turian reëstablished the Սուրբ Յակոբեանց Տպարան ("surbots yakobeants taparan"; St. James printing house); the Patriarchate housed important archives relating to the history of the Armenian people; pilgrimages of Armenians from Syria, Lebanon, and Egypt increased and the economy improved, attracting Armenian immigrants in higher numbers; Armenians held secular roles in governance, policing, and business, and founded social, religious, and educational organizations and institutions; Armenians in the Old and New Cities of Jerusalem were able to send financial aid to Armenian victims of a 1933 earthquake in Beirut, and to Armenians expelled in 1939 when Turkey annexed Alexandretta.

The situation would decline rapidly after the 1947 UN partition resolution gave Zionists tacit permission to expel Palestinians from broad swathes of Palestine. Jerusalem, intended by the plan to be a "corpus separatum" under international administration, was in fact subjected to a months-long war that ended with its being divided into western (Israeli) and eastern (Palestinian) sections. The Armenian population of Palestine began to decline; already, 1947 saw 1,500 Armenians resettled in Soviet Armenia. The Armenian populations in Yafa and Haifa would fall yet more significantly.

Still, the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem maintained its role as the center of Armenian life in Palestine; the compound provided food and shelter to thousands of Armenians during the Battle for Jerusalem and the Nakba (which began in 1948). Some Armenians formed a militia to defend the Armenian Quarter against Haganah shelling during the battle.

In the following years, historical British contributions to the shoring up of insular power in the Patriarchate would cause new problems. The Armenian secular community, no longer empowered to oversee the internal workings of the Patriarchate, could do nothing to prevent embezzling, corruption, and even the sale of church-owned land and buildings to settlers.

In 1967, Israeli military forces annexed East Jerusalem, causing another, albeit smaller, surge in Armenian emigration from the city. Daphne Tsimhoni estimates based on various censuses that the Armenian population of Jerusalem, which had reached 5,000-7,000 at its peak in 1945–6, had fallen back to 1,200 by 1978.

Today, as in the 20th century, Armenians in Jerusalem (who made up nearly 90% of the Armenian population of Palestine as of 1972) are known for the insularity of their community, and for their skill at various crafts. Armenian food culture has been kept alive and well-defined by successive waves of immigrants. As of 2017, the Armenian Patriarchate supplied about 120 people a day with Armenian dishes, including Ղափամա / غاباما "ghapama" (pumpkin stuffed with rice and dried fruits), թոփիկ / توبيك "topig" (chickpea-and-potato dough stuffed with an onion, nut, fruit, and herb filling, often eaten during Lent), and Իչ / ايتش "eetch" (bulgur salad with tomatoes and herbs).

Restaurants lining the streets of the Armenian and Christian quarters serve a mixture of Armenian and Palestinian food. Լահմաջո "lahmadjoun" (meat-topped flatbread), and հարիսա / هريس "harisa" (stew with wheat and lamb) are served alongside ֆալաֆել / فلافل ("falafel") and մուսախան / مسخن ("musakhkhan"). One such restaurant, Taboon Wine Bar, was the site of a settler attack on Armenian diners in January 2023.

Up until 2023, despite fluctuations in population, the Armenian community in Jerusalem had been relatively stable when compared to other Armenian communities and to other quarters of the Old City; the Armenian Quarter had not been subjected to the development projects to which other quarters had been subjected. However, a deal which the Armenian Patriarchate had secretly and unilaterally made with Israel real estate developer Danny Rotham in 2021 to lease land and buildings (including family homes) in the Quarter led Jordan and Palestine to suspend their recognition of the Patriarch in May of 2023.

On 26th October, the Patriarchate announced that it was cancelling the leasing deal. Later the same day, Israeli bulldozers tore up pavement and part of a wall in حديقة البقر ("ḥadīqa al-baqar"; Cows' Garden; Armenian: "Կովերի այգու"), the planned site of a new luxury hotel. On 5th November, Rothman and other representatives of Xana Gardens arrived with 15 settlers—some of them with guns and attack dogs—and told local Armenians to leave. About 200 Armenian Palestinians arrived and forced the settlers to stand down.

On 12th and 13th November, the developer again arrived with bulldozers and attempted to continue demolition. In response, Armenian Palestinians have executed constant sit-ins, faced off against bulldozers, and set up barricades to prevent further destruction. The Israeli occupation police backed settlers on another incursion on 15th November, ordering Armenian residents to vacate the land and arresting three.

On December 28th, a group of Armenian bishops, priests, deacons, and seminary students (including Bishop Koryoun Baghdasaryan, the director of the Patriarchate's real estate department) were attacked by a group of more than 30 people armed with sticks and tear gas. The Patriarchate attributed this attack to Israeli real estate interests trying to intimidate the Patriarchate into abandoning their attempt to reverse the lease through the court system. Meanwhile, anti-Armenian hate crimes (including spitting on priests) had noticeably increased for the year of 2023.

These events in Palestine come immediately after the ethnic cleansing of Լեռնային Ղարաբաղ ("Lernayin Gharabagh"; Nagorno-Karabakh); Israel supplied exploding drones, long-range missiles, and rocket launchers to help Azerbaijan force nearly 120,000 Armenians out of the historically Armenian territory in September of 2023 (Azerbaijan receives about 70% of its weapons from Israel, and supplies about 40% of Israel's oil).

Support Palestinian resistance by donating to Palestine Action’s bail fund; buying an e-sim for distribution in Gaza; or donating to help a family leave Gaza.

Ingredients

180g (1 cup) pearled wheat (قمح مقشور / խոշոր ձաւար), soaked overnight

3 cups water

180-360g (a scant cup - 1 3/4 cup) sugar, or to taste

Honey or agave nectar (optional)

1 cup total diced dried apricots, prunes, golden raisins, dried figs

1 cup total chopped walnuts, almonds, pistachios

1 tsp rosewater (optional)

Ceylon cinnamon (դարչին) or cassia cinnamon (կասիա)

Aniseed (անիսոն) (optional)

Large pinch of salt

Pomegranate seeds, to top (optional)

A Palestinian version of this dish may add pine nuts and ground fennel.

Pearled wheat is whole wheat berry that has gone through a "pearling" process to remove the bran. It can be found sold as "pearled wheat" or "haleem wheat" in a halal grocery store, or a store specializing in South Asian produce.

Amounts of sugar called for in Armenian recipes range from none (honey is stirred into the dish after cooking) to twice the amount of wheat by weight. If you want to add less sugar than is called for here, cook down to a thicker consistency than called for (as the sugar will not be able to thicken the pudding as much).

Instructions

1. Submerge wheat in water and scrub between your hands to clean and remove excess starch. Drain and cover by a couple inches with hot water. Cover and leave overnight.

2. Drain wheat and add to a large pot. Add water to cover and simmer for about 30 minutes until softened, stirring and adding more hot water as necessary.

Wheat before cooking

Wheat after cooking

3. Add dried fruit, sugar, salt, and spices and simmer for another 30 minutes, stirring occasionally, until wheat is very tender. Add water as necessary; the pudding should be relatively thin, but still able to coat the back of a spoon.

4. Remove from heat and stir in rosewater and honey. Ladle pudding into individual serving bowls and let cool in the refrigerator. Serve cold decorated with nuts and pomegranate seeds.

#the last link is a different / new fundraiser#Armenian#Palestinian#fusion#wheat berries#pearled wheats#pomegranate#prunes#dried apricot#dates#long post /

376 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Feast Day

Saint Ignatius of Antioch

35-107

Feast Day: October 17 (New), February 1 (Trad)

Patronage: Against throat diseases, the Church in the Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa

St. Ignatius of Antioch is one of the five "Apostolic Fathers," and was the third Bishop of Antioch. He was a disciple of St. John the Evangelist and is known for explaining Church theology. Ignatius was arrested by Roman soldiers and taken to Rome where he was sentenced to death at the Coliseum for his Christian teachings, practices, and faith. On his way to being martyred in Rome, he wrote letters to the early Christians, which we still have today, that connect the Catholic Church to the early, unbroken, clear teaching of the Apostles given directly by Jesus Christ. He urged the Christians to remain faithful to God, warned them against heretical doctrine, and provided them with the solid truths of the faith.

Prints, plaques & holy cards available for purchase. (website)

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Nicene Creed

We believe in one God,

the Father, the Almighty,

maker of heaven and earth,

of all that is,

seen and unseen.

We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ,

the only Son of God,

eternally begotten of the Father,

God from God, Light from Light,

true God from true God,

begotten, not made,

of one Being with the Father;

through him all things were made.

For us and for our salvation he came down from heaven,

was incarnate from the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary

and was made man.

For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate;

he suffered death and was buried.

On the third day he rose again

in accordance with the Scriptures;

he ascended into heaven

and is seated at the right hand of the Father.

He will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead,

and his kingdom will have no end.

We believe in the Holy Spirit,

the Lord, the giver of life,

who proceeds from the Father and the Son,

who with the Father and the Son is worshipped and glorified,

who has spoken through the prophets.

We believe in one holy catholic and apostolic Church.

We acknowledge one baptism for the forgiveness of sins.

We look for the resurrection of the dead,

and the life of the world to come.

Amen.

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

inclusion this, diversity that… why don’t you include yourself in the one holy catholic and apostolic Church through Baptism and experience the diverse gifts of life in Christ

#“truth is subjective” yeah how about you Subject yourself to the Truth of the deposit of faith#catholic#catholicism#file under caroline#greatest hits

747 notes

·

View notes

Text

x . x

transcript of the wikipedia screenshot from here (click):

Climbing the Holy Stairs on one's knees is a devotion much in favour with pilgrims and the faithful. Several popes have performed the devotion,[5] and the Catholic Church has granted indulgences for it.[10] Pope Pius VII on 2 September 1817 granted those who ascend the Stairs in the prescribed manner an indulgence of nine years for every step. Pope Pius X, on 26 February 1908, conceded a plenary indulgence as often as the Stairs are devoutly ascended after Confession and Holy Communion. On 11 August 2015, the Apostolic Penitentiary granted a plenary indulgence to all who, "inspired by love", climbed the Stairs on their knees while meditating on Christ's passion, and also went to Confession, received Holy Communion, and recited certain other Catholic prayers, including a prayer for the Pope's intentions.

#taemin#shinee#lee taemin#ephemeral gaze#just enjoying the various thoughts on Heaven#heaven#taemin heaven#shinee twitter#taemin t#eternal meta

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

by Adam Gregerman

Pope Francis has called for an investigation to determine if Israel’s operation in Gaza constitutes genocide, according to a new book published for the Catholic Church’s jubilee year. “According to some experts, what is happening in Gaza has the characteristics of a genocide,” the pope said in excerpts published Sunday by the Italian daily La Stampa.

What makes the inflammatory statements in the pope’s book especially disturbing is that they follow on remarks by the pope that appear to demonize Jews even more broadly and which are contrary to teachings of the Church. Pope Francis’ prior Letter to Catholics of the Middle East on the first anniversary of the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas attack on Israel from Gaza provoked widespread confusion and consternation among Jews and Catholics. While he has spoken regularly about the attack and the fighting that erupted in its wake, his inclusion in the letter of a citation of John 8:44 to denounce the evils of war was to many inexplicable.

The verse chosen by the pontiff, a vitriolic accusation that the Jews “are from [their] father, the devil,” has for centuries provoked and been used to justify Church hostility to Jews. Yet such terrible imagery of Jewish malfeasance is thoroughly out of place in a modern Catholic document. Regrettably, the pope nonetheless chose to use this notorious verse at a time when global antisemitism has reached disturbingly high levels. Such a statement threatens the intellectual work of his Catholic predecessors going back to the 1960s.

While the citation is surely troubling, more significant is the letter itself, for it is yet another example of an ongoing presentation of Francis’ extensive and controversial views on the Israel-Hamas war. This letter has made people aware of this significant body of statements and demonstrates the compelling need to understand current relations with one of the Jewish community’s most influential and important partners, Pope Francis and the Catholic Church. In the year after the attack, Francis has spoken publicly about the war at least 75 different times. The conflict is not just like other conflicts, for it occurs in a place “which has witnessed the history of revelation” (2/2/24). Not only is he understandably very distressed about the war, but he is also clearly knowledgeable about it and notes many aspects of it (e.g., hostages, negotiations, humanitarian aid, Israeli airstrikes, challenges for aid workers). With the possible exception of Russia’s war on Ukraine, no other conflict has received such frequent mention by Francis, nor has he engaged so intimately with the specific features of other, often more deadly conflicts. He addressed the war most often in scheduled gatherings for the Sunday Angelus Prayer and in weekly audiences with the general public, though he has discussed it at greater length in official contexts (e.g., Address to Members of the Diplomatic Corps Accredited to the Holy See, 1/8/24).

Pope Francis does not just speak homiletically. His statements express his deep-seated and passionate convictions about morality and political affairs. They also both reflect and influence current trends in Catholic thinking about the Israel-Hamas war. The Holy See of course is not just a religious institution but also a state, engaged in pragmatic exchanges and negotiations with other states and organizations. The pope’s views on war and peace necessarily shape Vatican diplomacy and guide Catholic political proposals, as seen for example in the statement of the Apostolic Nuncio to the U.N. in January 2024, which is replete with references to Francis’ speeches and elaboration on his ideas.

Francis is struggling to reconcile traditional Catholic just war theory, which began with St. Augustine centuries ago, with contemporary Catholic resistance to almost any justification of war, especially without international sanction (Fratelli Tutti 258 n. 242; see also the Catechism of the Catholic Church 2302-17). The latter, more skeptical view of war has roots in the 19th century but emerged strongly after World War II and the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), especially in the wake of the Shoah and the development of nuclear weapons. It continues to develop today, with Francis giving it his own emphases that reflect his roots in the global south and the influence of liberationist theology.

It is ironic, or perhaps predictable, that the Catholic Church in the modern period, now without access to military power, has moved away from just war theory and now largely deploys its more restrained views of war and peace in judging others. Given the prominence of the Israel-Hamas war in Francis’ speeches and its moral and political complexity, as well as his stature internationally, his views are relevant and influential.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

thank christ that's over, back to composing smut

my kid really wants to see her best friend’s baptism this morning, so I’m masking up so I don’t breathe in whatever nondenominational-but-dogmatic-in-a-new-way-we-made-up stuff they’ve got going on, and I might bring a bible with the apocrypha just for yuks

#religion cw#Christianity cw#'this is a church?? this looks like an information center or a place where you handle rent'#my child has been spoiled by attending mass three times a week in a cathedral and I love her so much#guy who lifted his whole order of worship from the liturgy but for some reason made the sign of peace last twenty minutes:#'now obviously we don't *believe* the eucharist *really* transforms inside us to the blood and body of christ'#me: ChristianBaleNodding.gif#they did the Apostles' Creed for the baptisms but it was 'one holy ~universal~ and apostolic church'#like... uh-huh. can't wait until you find out what catholic means

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

Please pray for me, I have been a catechumen for almost 2 years but the more time the passes the more uncertain I become about joining any church. Recently another person I know left orthodoxy for catholicism and explained all their reasonings for why and I just feel inner turmoil about my choices. I do find my church to be very beautiful but at the same time I just dont fit in with the people there and always feel like an outsider even though they have been very welcoming and that also makes it hard for me...I just dont know...

I’ll be praying for you dear anon! You’re welcome to send me a pm if you want to talk more about it.

Church isn’t really about socializing, I’m sure you’ve figured that out. The main objective of the spiritual life isn’t just to improve this temporal life by making friends or adopting a Christian culture or having a third-space (Church).

St. Seraphim of Sarov, a most wise Orthodox saint, exhorted us, Acquiring the Spirit of God is the true aim of our Christian life, while prayer, fasting, almsgiving and other good works done for Christ's sake are merely means for acquiring the Spirit of God.

The word of God does not say in vain: The Kingdom of God is within you (Luke 17:21), and it suffers violence, and the violent take it by force (Matt. 11:12). That means that people who, in spite of the bonds of sin which fetter them and (by their violence and by inciting them to new sins) prevent them from coming to Him, our Savior, with perfect repentance for reckoning with Him. They force themselves to break their bonds, despising all the strength of the fetters of sin—such people at last actually appear before the face of God made whiter than snow by His grace. Come, says the Lord: Though your sins be as purple, I will make you white as snow (Is. 1:18).

God has given us all the weapons we need to acquire the Holy Spirit: He has given it to us through the one holy, catholic, and apostolic Church! From the first martyr Stephen until this day, Orthodox Christians are dying at the hands of barbarians, choosing to preserve their faith from heresies, atheism, and all manner of demonic forces. We must force ourselves to break the fetters of lethargy, to rise from the drowsiness of sin, to be warm in the coldness of the modern age. We must hold fast to the Ark of Salvation, the Church that has not changed since the time of its creation on Pentecost, lest we capsize amidst the tumultuous waves of the age and perish.

Someday, God willing, you will receive an Orthodox baptism; your soul will receive a spotless wedding garment, and when you approach the chalice, you will recite the prayer of preparation for Holy Communion:

“It is good for me to cleave unto God and to place in Him the hope of my salvation.”

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was the morning of May 24, 1888, and a large, ethnically diverse crowd waited in the Sala Ducale of the Apostolic Palace in Rome for the pope to arrive. Led by Cardinal Charles Lavigerie, the French missionary archbishop of Algiers, the group had traveled to Rome on a double pilgrimage from North Africa and from the Diocese of Lyon, France. The pilgrims had earlier entered St. Peter’s Square with camels and a special gift for the pope: a pair of gazelles wearing silver collars inscribed with Latin verse.

Shortly after noon, the smiling Pope Leo XIII and his entourage entered the Sala Ducale to sustained applause from the pilgrims. It was a special year for Leo: the golden jubilee of his ordination to the priesthood. Preparations had been underway throughout nearly the entirety of 1887 for the yearlong celebration in which the pope would receive thousands of gifts from all over the world and greet an abundance of well-wishers.

Among the pilgrims who traveled to Rome during Leo’s jubilee, however, this group was unique, and its uniqueness was indicated by the 12 men strategically placed at the front of the crowd. These 12 African men had been enslaved before their freedom was purchased by Lavigerie and his missionaries. They were at the head of the group because today’s audience was an unofficial celebration of the release of Pope Leo’s encyclical on slavery.

On Feb. 10, the Brazilian statesman and abolitionist Joaquim Nabuco had met with Leo in a private audience and asked the pope to write the encyclical. Brazil was on the cusp of abolishing slavery, which would make it the last country in the Western Hemisphere to do so. Due to the Brazilian princess regent Isabel’s devout Catholicism, Nabuco thought a letter from the pope condemning slavery might embolden her to support abolition more aggressively. Leo was happy to oblige, and the news about this antislavery encyclical began to spread.

Upon hearing of it, Cardinal Lavigerie wrote to the pope and asked him to include something about the continuing presence of slavery in Africa. The anti-abolition prime minister of Brazil, however, was not happy with the news from Rome, and he successfully pressed the Holy See to delay the issuance of the encyclical.

Despite the prime minister’s back-channel machinations, Brazil’s parliament passed the abolition bill, and it was signed into law by Isabel on May 13. When the encyclical, titled “In Plurimis,” was released to the public on May 24, it was dated May 5, as if Pope Leo wanted it on the record that he had supported Brazilian abolition before it became the law of the land. Nevertheless, this late release intersected perfectly with Cardinal Lavigerie’s pilgrimage. The day before the audience, the 12 formerly enslaved men had been given the chance to read the document. Though other encyclicals of Leo would come to overshadow this one, it surely was one of his most theologically significant. For with “In Plurimis” and his follow-up encyclical, “Catholicae Ecclesiae,” Leo XIII did something astounding: He changed the church’s teaching on slavery. The Catholic Church, for the first time in its history, had finally gotten on board with abolitionism.

Divergent Explanations

That revolutionary day when Leo XIII became the first pope to condemn slavery is not well known by many Catholics and is rarely mentioned in scholarship related to the church’s history. This is not terribly surprising. The church’s historical engagement with slaveholding is very complex, and it is also widely misunderstood. Even in the past several years, well-intentioned Catholic writers have published accounts of the church and slavery that are full of inaccuracies.

Often, those inaccurate accounts are written to defend the church in some way. In 2005, for example, Cardinal Avery Dulles wrote a book review in First Things claiming that the popes had denounced the trade in African slaves from its very beginnings and yet had never condemned slavery as such, retaining a continuity of teaching that always allowed for some “attenuated forms of servitude.” Other apologists have taken a more absolute position: The church has always been against slavery itself. Both these lines of argumentation seem to agree on two central assertions: The popes always condemned the trade in African slaves, and the church’s teaching did not change.

Defending the church, either in its reputation or its doctrinal continuity, can be praiseworthy. But when it comes to the history of the Catholic Church and slaveholding, this posture of defense has been deeply damaging. It has unnecessarily led to confusion around the church’s history with slaveholding, and that confusion has helped to prevent the church from reckoning with a troubling history whose consequences are still present in our world.

The history of the church was nothing close to a steady, if interrupted, march to eliminate slavery.

And yet it was once widely known, and still is among historians of slavery today, that the Catholic Church once embraced slavery in theory and in practice, repeatedly authorized the trade in enslaved Africans, and allowed its priests, religious and laity to keep people as enslaved chattel. The Jesuits, for example, by the historian Andrew Dial’s count, owned over 20,000 enslaved people circa 1760. The Jesuits and other slaveholding bishops, priests and religious were not disciplined for their slaveholding because they were not breaking church teaching. Slaveholding was allowed by the Catholic Church.

One of the reasons the church’s past approval of slaveholding is so little known among the general Catholic population today is that the very popes who reversed the church’s course on slavery and the slave trade also promoted that same inaccurate narrative that defended the church’s reputation and continuity—even, intentionally or not, at the cost of the truth.

Condemning the Atlantic Slave Trade

The shifts began quietly. In 1814, Pope Pius VII, at the request of Great Britain prior to the upcoming Congress of Vienna, privately sent letters to the kings of France and Spain asking them to condemn the slave trade. At this time in history, condemning the trade did not equate to condemning slavery itself. “The slave trade” meant the transatlantic shipping of enslaved persons from the African continent to the New World. Hence, the slaveholding U.S. President Thomas Jefferson, prior to signing an anti-slave-trade bill into law in 1807, saw no contradiction in referring to the trade as “those violations of human rights” against “the unoffending inhabitants of Africa” all while continuing to keep Black descendants of the trade’s immediate victims enslaved. Britain itself outlawed the trade in 1807, but slaveholding remained legal afterward in parts of its empire. In the same vein, Pius’s private letters referred only to the trade, not to slavery itself.The Door of No Return is a memorial in Ouidah, a former slave trade post in Benin, a country in West Africa. (Alamy)

The papacy’s condemnation of the trade became a public one in 1839 with Gregory XVI’s bull “In Supremo Apostolatus.” Though the bull came, once again, at the request of Great Britain, Gregory deserves praise for being the first pope to publicly condemn the Atlantic slave trade after nearly four centuries of its operation. The bull was a strong one in many ways, blaming the advent of the trade on Christians who were “basely blinded by the lust of sordid greed.” And yet, as with Pius VII, Gregory did not speak directly on the issue of whether slaveholders in the Americas should free their enslaved people, something he easily could have included.

So when some abolitionists in the United States greeted Gregory’s bull as a fully antislavery document, Catholic bishops like John England of Charleston, S.C., and Francis Patrick Kenrick of Philadelphia argued that the only thing the bull did was precisely what the United States had already done: ban participation in the international slave trade. Gregory corrected no one’s interpretation, and so Catholic slaveholding was able to continue in the United States and elsewhere, arguably without disobedience to church teaching.

The Catholic Church approved, multiple times and at some of its highest levels of authority, of one of the gravest crimes against humanity in modern history.

Why Gregory was the first pope to publicly condemn the trade is an agonizing and perhaps unanswerable question. The arguments that Gregory used to support his condemnation had been articulated by countless theologians and activists over the previous few centuries, including by the representatives of Black Catholic confraternities who protested the trade before the Holy See in the 1680s. Any pope since at least the 1540s, when the Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas changed his opinion on the trade after researching its injustices, could have issued nearly the same bull as Gregory did. Gregory was just the first to choose to do it.

Rewriting History

Unfortunately, Gregory also provided a narrative in his bull that did not present a truthful portrait of the church’s engagement with the trade. Pius VII had made an ambiguous and dubious claim that the church had helped to abolish much of the world’s slavery and that the popes had always “rejected the practice of subjecting men to barbarous slavery,” but Gregory expanded upon this claim in detail. He wrote that in ancient times, “those wretched persons, who, at that time, in such great number went down into the most rigorous slavery, principally by occasion of wars, felt their condition very much alleviated among the Christians.” He claimed that slavery was gradually eliminated from many Christian nations because of “the darkness of pagan superstition being more fully dissipated, and the morals also of the ruder nations being softened by means of faith working by charity.”

In Gregory’s telling, this steady Christian march toward eliminating slavery from the earth was then interrupted by greedy Christians who reduced Black and Indigenous peoples to slavery or who bought already enslaved persons and trafficked them.

Gregory claimed that the papacy had been opposed to these new situations of enslavement: “Indeed, many of our predecessors, the Roman Pontiffs of glorious memory, by no means neglected to severely criticize this.” As evidence for this statement, he cited the bulls prohibiting the enslavement of Indigenous peoples in the Americas written by Paul III, Urban VIII and Benedict XIV, as well as the then recent condemnations of the trade by Pius VII. He also included a curious reference: a 1462 letter of Pius II that, Gregory wrote, “severely rebuked those Christians who dragged neophytes into slavery.”

This narrative was deeply misleading. The history of the church was nothing close to a steady, if interrupted, march to eliminate slavery. Rather, the early church embraced slaveholding both before and after Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire, and the medieval church expanded the ways by which someone could become enslaved beyond those allowed by pagan Rome—allowing, for example, that women in illicit relationships with clerics could be punished with enslavement. Theologians like St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas theologically defended the practice of keeping humans enslaved, and St. Gregory the Great gave enslaved people to his friends as gifts.

Moreover, while it was true that the popes condemned the enslavement of Indigenous peoples in the Americas, the trade in African slaves was permitted and encouraged by a series of popes from Nicholas V, who died in 1455, forward. Gregory XVI mentioned none of this, instead seeming to suggest that Pius II’s letter meant the popes’ hands had always been clean with regard to the trade. But Pius II’s condemnation had nothing to do with the general Portuguese trade in enslaved Africans; it instead concerned a particular instance of Catholic converts being kidnapped. Nicholas V’s bulls had specified that only non-Christians could be seized and enslaved. Pius II’s letter was in accordance with Nicholas’ permissions, not against them.

While it was true that the popes condemned the enslavement of Indigenous peoples in the Americas, the trade in African slaves was permitted and encouraged by a series of popes.

The inaccuracy of this narrative did not go unnoticed. The Portuguese consul in Brazil scoffed at the bull, writing that “its doctrine has been most rarely sent forth from the Palace of the Vatican, for it is well known that Nicholas V…and Calistus III…approved of the commerce in slaves” and that Sixtus IV and Leo X also approved of the trade even after the letter of Pius II. He noted that Scripture did not condemn slavery and that the popes had previously condemned only the enslavement of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

Erroneous as Gregory’s narrative may have been, he was not pulling it out of thin air. Some British and American abolitionist historians had been promoting such a narrative for decades in an attempt to argue that Christianity had historically been an antislavery religion. Just five years prior to Gregory’s bull, for example, the American historian George Bancroft falsely claimed that the slave trade “was never sanctioned by the see of Rome.” It is possible, then, perhaps even likely, that Gregory XVI honestly believed this narrative to be accurate. Nevertheless, it was wrong, and its publication in a papal bull meant that it would spread more widely.

An Abolitionist Church

When Leo XIII condemned not merely the slave trade but slavery itself on that exciting day in 1888, it may have not been too shocking to most people who heard the news. Slavery was now legally abolished in the Christian world; why would the church not be opposed to it? And yet both Nabuco and Lavigerie understood that Leo was making history. The condemnations of slaveholding that Leo issued in 1888 and 1890 did not represent merely a change in policy, which itself would have been momentous enough. The change was a theological one. What the Holy Office only a couple decades prior had proclaimed was “not at all contrary to natural and divine law” was now declared by Leo to be contrary to both.

Leo even used the arguments of abolitionists to make his case. There was a certain set of theological propositions that abolitionist theologians had been promoting for centuries, from as early as St. Gregory of Nyssa to the 19th-century abolitionists Maria Stewart, Frederick Douglass and the French Catholic journalist Augustin Cochin. These propositions had been criticized or ignored by most Catholic theologians who wrote in favor of slavery, but Leo’s documents were filled with them. His successors would repeat and even deepen those abolitionist ideas in their own antislavery documents over and over again.

And yet, bold and praiseworthy as Leo’s abolitionist encyclicals were, he further concealed the truth about church history. Ignoring centuries of papal, conciliar and canonical approval of slavery, Leo strengthened Gregory’s narrative of a long antislavery march through history and inaccurately listed additional popes who had supposedly condemned the trade in African slaves and even slavery itself—including one of the popes who had renewed Nicholas V’s permissions.

What the Holy Office only a couple decades prior had proclaimed was ‘not at all contrary to natural and divine law’ was now declared by Leo to be contrary to both.

As with Gregory, Leo may sincerely have believed these falsehoods to be true. But far from being officially corrected, this erroneous papal narrative has survived online and in print. Even St. John Paul II, who apologized for the participation of Christians in the slave trade, repeated the false claim that the trade had been condemned by Pius II.

The Need for Reckoning and Reconciliation

The Catholic Church’s change in teaching regarding slavery was striking. While that change raises important theological questions about ecclesiology and doctrinal development, we must reject the temptation to jump straight to those questions without also doing the hard and painful work of reckoning with this history. It is morally imperative that we admit and deal with a series of difficult truths: that the Catholic Church approved, multiple times and at some of its highest levels of authority, of one of the gravest and longest-lasting crimes against humanity in modern history—and did not withdraw that approval for nearly 400 years.

During the full history of the Atlantic slave trade, roughly 12.5 million African men, women and children were forced onto ships to be sent across the ocean to a life of forced labor. Almost two million did not survive that journey. The survivors and millions of their descendants, all human beings made in God’s image, were the chattel property of other humans who had the power to whip them, force them to work unpaid their entire lives and keep their children enslaved as well.A bas-relief sculpture on the wall of the Our Mother of Africa chapel at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C., depicts the African American experience from slavery to emancipation and the civil rights movement. (CNS photo/Patrick Ryan for the National Black Catholic Congress via Catholic Standard)

As Catholics, we must consider the human beings affected by the church’s actions. How many people died chained to the disease-ridden hulls of ships because the popes before Gregory XVI repeatedly failed to take a bold stand? How many enslaved people were sexually assaulted because they were placed in a legal position allowed by the popes before Leo XIII that left them vulnerable to such abuse? How many enslaved people fell away from the Catholic faith because priests told them that the oppression they were experiencing was occurring with the approval of Holy Mother Church?

A process of reconciliation is needed. Our church needs to admit these past injustices.

As part of that reconciliation process, we need to do our best to repair the harm caused by the injustices our church perpetuated. Anti-slave-trade Catholic theologians of the 16th century were already writing about the need to make restitution to enslaved people. One 17th-century Capuchin even wrote about the eventual need for the descendants of slaveholders to make restitution to the descendants of the enslaved. Some religious communities have taken steps toward reconciliation, including the Jesuits of the United States, but at some point the Vatican will have to do the same. Perhaps there could be an international commission, or maybe a synod. When we consider the millions of lives the trade harmed and still harms to this day, it is difficult to imagine even the convoking of an ecumenical council as being too extreme a remedy.

Pope Leo XIII righted one significant wrong when he changed the Catholic Church’s teaching on slavery in 1888, and the popes since then should be lauded for their continual denunciation of slavery, slavery-like economic practices and contemporary human trafficking. But as with every unconfessed and unaddressed sin, harm remains. It takes courage to pick up that examination of conscience and pray with it. It takes courage to enter the confessional, say what needs to be said and commit to doing what needs to be done. And yet the justice and love of God demand such steps.

#Slavery and the Catholic Church: It’s time to correct the historical record#catholic church#curse of cannan#church lies#white lies#Black Lives Matter#Reparations

66 notes

·

View notes

Note

How much Latin should a Catholic know? For example, should one know Our Father? Hail Mary? The whole rosary? Entire Creeds? None? Would love your opinion/scholarly analysis! Always appreciate you, God bless

I don't think there is a cookie-cutter answer for this. If I had to give a no-nuance answer to the minimum amount of Latin an individual Catholic should know, I'd say "the amount of Latin used in your region's average Novus Ordo Mass."

That being said, I am never going to advocate against learning a language. I think there are a lot of benefits in learning and studying a given text in its original language (or, in the case of the Creeds and the standard prayers, in the language through which the Latin Church Fathers interpreted them).

To use one example: in the United States, the English translation of the Nicene Creed used in the Roman Rite uses the phrase "I believe in one, holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church." But if you look at the original ("original"; bear with me) Latin, there is no "I believe in," but "I believe." (Credo in unum Deum […] Et in unum Dominum […] Et in Spiritum Sanctum […] Et unum, sanctam, catholicam et apostolicam Ecclesiam). This linguistic construction was considered very important to the Latin Fathers; you "believed in," you placed your faith in, the three Persons of the Trinity in a way you didn't "believe in" the Church. You simply believed the Church in what She said about the God who established Her. This is a nuance that is lost in our English translation.

To be quite honest with you, I pray purely in the vernacular. English is the one and only language that I feel comfortable inhabiting enough to speak to God in. (Hopefully someday soon I will add Swedish to that list, but for now I am a living American stereotype). But if you look at the Pater Noster, or the Ave Maria, or the text of the Missale Romanum, you know, you potentially learn to look at these prayers in a new way.

So the short answer, really; you shouldn't feel obligated to know Latin, but learning Latin might help you gain further insight into the prayer life of the Latin Church.

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

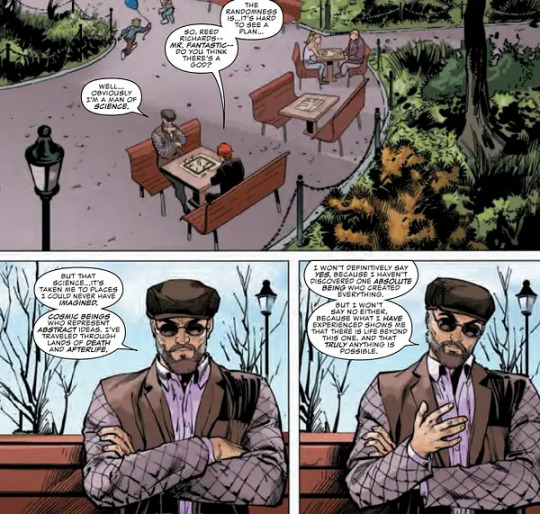

Hi! Rookie X-Men question, given how every so often characters tend to die (and then come back), have any of the more specifically religious members of the group, like Nightcrawler, had to wrangle the theological implications of that, or having to deal with dying in-Marvel being very different to how they expect?

Theology is a tricky concept in the Marvel Universe more broadly. Start with the baseline weirdness of what it means to believe in a monotheistic deity when the gods of various pantheons walk the earth as heroes and villains, and where many beings of ultimate cosmic significance can be met in the vastness of space:

Reed Richards is actually lying here. He's gone to the actual Heaven (to retrieve the soul of Ben Grimm) and met the "One Above All" in Fantastic Four #511, and it turns out that in the Marvel Universe, God is literally Jack Kirby, drawing everything into existence:

How this fits in with the existence of multiple gods, multiple Heavens and multiple Hells, is left up to the reader to untangle - just another continuity wrangle to No Prize.

The X-Comics haven't always done much better. As you point out, Kurt Wagner is a faithful son of the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church - although I'm sometimes annoyed by writers who can only remember this one detail about him and forget the dashing swashbuckler stuff that's actually way more fun - and his belief ought to be tempered that he's actually died, gone to the explicitly Christian Heaven, and been resurrected by bamfs (it was weird). On the other hand, in the infamous "Draco" storyline, Kurt has also found out that angels and demons are tribes of mutants and that he's the son of the demon Azazel. And in the equally infamous "Holy War" storyline, Kurt became a Catholic priest as part of a theologically-unsound plan to make him Pope so that he could be revealed as the Antichrist and convince people that the Rapture had begun - even though Catholics don't believe in the Rapture.

However, things got a lot better with Jonathan Hickman's House of X/Powers of X and the advent of Krakoa, because all of the sudden there were much more interesting questions to ask. Were mutants the new gods, as Magneto had proclaimed? What did the Church's promise of immortal life mean, now that mutants had defeated death and brought about immortality in this life? What would be the new commandments of the mutant Eden?

As a member of the Quiet Council and the X-Men's resident philosopher, Nightcrawler would be the one asking and answering these questions. In my absolute favorite issue of Hickman's run on the X-Men, Kurt is pushed to seek answers to these questions by the new mutant tradition of "Crucible" - by which depowered mutants must face [A] in the arena to win their right to be reborn into glory through enduring a slow and violent death - and his discovery that Krakoa had built for him a cathedral that only a mutant who can teleport could enter.

In Si Spurrier's run, Kurt investigates these questions by interrogating the laws of Krakoa and how they shape the nascent mutant culture being born on the island. The danger is, that in a world in which life extends forever and death has no meaning, that mutants will fall into sadism and apathy. Kurt's new religion, "the Spark," seeks to combat spiritual neurasthenia with a commitment to the relentless pursuit of the new.

But questions remain: why, in both Moira's Ninth Life and the Sins of Sinister timeline, does Kurt Wagner become the originator of a new sub-species of chimeras with his mutant powers and his appearance and a common commitment to the last religion in existence? What happened to the Golden Child miraculously born to his genetic descendent Wagnerine? Did she survive the destruction of the timeline?

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint Ignatius of Antioch

35-107

Feast Day: October 17 (New), February 1 (Trad)

Patronage: Against throat diseases, the Church in the Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa

Saint Ignatius of Antioch is one of the five "Apostolic Fathers," and was the third Bishop of Antioch. He was a disciple of St. John the Evangelist and is known for explaining Church theology. Ignatius was arrested by Roman soldiers and taken to Rome where he was sentenced to death at the Coliseum for his Christian teachings, practices and faith. On his way to being martyred in Rome, he wrote letters to the early Christians, which we still have today, that connect the Catholic Church to the early, unbroken, clear teaching of the Apostles given directly by Jesus Christ. He urged the Christians to remain faithful to God, warned them against heretical doctrine, and provided them with the solid truths of the faith.

Prints, plaques & holy cards available for purchase here: (website)

95 notes

·

View notes