#octave aubry

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Books about Napoleonic era (and Polish history) - 3

Good day, dear all, and let me share with you some books I've read recently.

And because today is the birthday of Tadeusz Kościuszko I'll start with a biography of him The Peasant Prince, by the American historian Alex Storozynski:

2. One more position about the Polish history, in English, I'd like to recommend you is Richard Butterwick's The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, 1733–1795: Light and Flame, dedicated to the reigns of Polish-Lithuanian two last kings, Augustus III Wettin and Stanisław August Poniatowski:

From the topic of Polish history let's switch to the French one.

3. One more addition to my collection of Talleyrand's biographies was this one, written by Robin Harris:

4-5. Then, there were two books about Napoleon's private life, by Octave Aubry and Sigrid-Maria Größing:

6-7. A study on the topic of French revolutionary and imperial generals, by Georges Six, and George Nafziger's Imperial Bayonets. (These were books with lots of military details, so I can't say I've enjoyed them thoroughly, rather not belonging to their target audience))

8. And this is a book I really liked, The anatomy of Glory by Henry Lachouque! And though its subtitle (Napoleon and his Guards) kinda states the book will be focused on the Imperial Guards, in fact its topics turned out much more wider, including information on Napoleon himself, France and even some details of the usual life of that times:

9. The book majority of you have already read, The Iron Marshal, a biography of Louis Nicolas Davout by John Gallaher:

10-11. And the last but not the least - two books on Murat. The first is a book by the French historian Jean Tulard and the second is an impressive work of Sarah Hammel @joachimnapoleon.

Thanks a lot, Sarah, for letting as see Joachim Murat through his letters, from his own point of view!

#books#napoleonic era#history books#kościuszko#tadeusz kościuszko#Alex Storozynski#Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth#Richard Butterwick#Talleyrand#charles maurice de talleyrand périgord#Robin Harris#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#Octave Aubry#Sigrid-Maria Größing#Georges Six#George Nafziger#Henry Lachouque#Louis Nicolas Davout#John Gallaher#joachim murat#jean tulard#Sarah Hammel

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

A picture featuring Paul Barras as a young man.

From: Octave Aubry, Napoléon, Editions Flammarion (1961)

#I couldn't believe it was him when I stumbled upon this pic lol#ngl he looks like the average 21th century mmorpg player#paul barras#barras#directoire#directory#frev#french revolution#frev art#art

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I think I read in a few biographies that Marmont later met the Duke of Reichstadt, aka, Napoleon’s legitimate son? Can you tell me about that meeting from Marmont’s perspective? Thanks a bunch!!!

Hi!

Thank you alot for asking me

Marmont was his tutor in French and just literature in general ( I'm like 90% it was those subjects, but if I'm wrong, I'll make a correction)

At first Napoleon II. didn't like him (I'm mean he DID surrender Paris....betray his dad....and all that stuff)

But over time they even made a bond. Now it isn't 100% for certain....that bond might have grown because of the fact that Marmont was giving him stories about his dad. Of course he wasn't allowed to do that, you have to remember this is Marmont-he does not care.

Marmont was his tutor for around 3 or so months, and when his tutoring was over the Duke lifted him a portrait of himself as a parting gift (Marmont cherished this portrait, and its in amazing condition....it's keept at his home)

Here is said portrait:

Even after they somewhat bonded because of their ties to Napoleon, I wouldn't say that Napoleon II really "loved" or even "liked" him.

More of a. ... "I guess I can tolerate you?"

I think this quote that @promises-of-paradise sent to the discord server from Napoleon II biography is a good example of what Napoleon II thought of him (the book is "the king of Rome" by Octave Aubry)

Marmont thought he was a smart boy, he did all of his work and was passionate

I hope that I answered your question well ☺️💕💕

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

The short and very miserable life of Napoleon II, aka the Eaglet, aka Franz, Duke of Reichstadt: PART ONE

Napoleon’s son with Marie Louise, his second wife, the daughter of the Holy Roman Emperor Habsburg Emperor Francis II, is known by a variety of names: Napoleon II, the Eaglet, l’Aiglon, King of Rome, or Franz, Duke of Reichstadt. It seems to me this kid barely gets mentioned as a footnote in most popular biographies of Napoleon. Of course Napoleon loved kids, and was over the moon that he finally had his own legitimate child, his own son and heir. He doted on this adorable and spirited blond moppet, being super affectionate with him, playing with him, spending lots of time with him, bringing him into his study to cuddle with him as he read dispatches, or tossing him up into the air when the toddler pulled on his coat-tails.

It’s very sweet and heart-warming to read all these adorable father-son moments, but honestly it’s depressing as hell to realize the best years of the Eaglet’s life was up to the age of four.

When he parted from his father after his defeat in Russia, it was all horribly and sickeningly downhill from there.

So I was reading Octave Aubry’s biography The King of Rome: Napoleon II. It’s not a new bio by any means— it’s from 1932. But it is thoroughly researched and very well written, with lots of cites from various Viennese archives, and Jesus Christ, it is depressing. The Eaglet was physically and emotionally abused by the Habsburg side of his family and by their minions for most of his very short life, and it makes for a harrowing read.

What did his mother do to stop it, you may ask? Unfortunately, the answer is absolutely nothing.

TW: CHILD ABUSE

So, the best that could be said about his mother, Marie Louise, was that she was a weak character. If I wanted to be more blunt, I’d say she was spineless enough to the point I wonder if she was even a vertebrate.

She was, of course, raised to hate Napoleon as a child. But then she met him and fell in love with him. She was very eager to be loved and do everything he asked her to do, even if (as Andrew Roberts points out in his own mammoth biography of Napoleon) she wasn’t the brightest bulb. But perhaps she was a perfectly cromulent empress when war wasn’t on her doorstep and she wasn’t asked to make decisions: but once the war WAS on her doorstep and decision-making was called of her, she fell apart like wet tissue. As Aubry explains:

That it would be a capital mistake for Marie Louise and her son to leave Paris was painfully evident to everyone, even to the Empress herself. But no initiative could have been expected of her. Willing, always of the best intentions, she was a passive creature both by temperament and education. She could never be more than an instrument in the hands of others. But Hortense, who had a resolute spirit behind that bleat of hers, showed both intelligence and heart in the circumstances. She was waiting for Marie Louise when the council was over, and said to her:

‘Sister dear, you must realize that in leaving Paris you will be neutralizing the defense and so lose your crown. I observe that you are making the sacrifice with great resignation.’

The Empress replied gently, almost humbly:

‘You are right. It is not my fault— the Council has decided that way.’

She was hoping vaguely for a letter from the Emperor, a counter-order that would permit her to remain. [Aubry pg 54]

At this point Louise, after fleeing Paris, wanted to be reunited with Napoleon, but she just cried and wrung her hands, as her lady-in-waiting Mme Lannes, in cahoots with Talleyrand, poured poison into her ear about how Napoleon never loved her. Then Talleyrand conspired to have all of Louise’s stuff stolen. The soon-to-be-ex-empress continued to cry and do nothing, only to go “to her room to collapse on her knees at her bedside.”

Anyway, her father swooped in and picked her up, and Metternich arranged to have Neipperg, a dashing, managing middle-aged man in uniform (Louise definitely had a type), seduce her. Within the space of weeks, she immediately changed her tune with regards to her husband, and wanted to have nothing more to do with him. As for the Eaglet, though he ended up in Vienna, he was in the care of his beloved governess, Mme de Montesquiou, aka “Maman ‘Quiou.” He was in good hands while Maman ‘Quiou was allowed to stay with him, but she was deathly afraid of being sent away, since she knew Louise was indifferent to her child and would never do the right thing, now that she was the puppet of her father and of Metternich.

With her son whom she had not seen for three months and who was enraptured at her return, she [Marie Louise] concerned herself less and less. In spite of the caresses and the gifts that were showered upon her, Mme. de Montesquiou saw things clearly and passed her judgment. Writing to her husband who was urging her to leave Vienna she said:

“My dear, do not call it my duty to return to France. As I have already advised you, you would be putting me in the greatest embarrassment, and my conscience would trouble me all my life long… If that child has a mother, very well, I could place him in her hands and be satisfied. But she is nothing less than that: she is more indifferent to his fate than the veriest stranger in his service.”

And to an intimate she confided in disgust at what she suspected and intuited:

“I have seen painful things, and I keep seeing them every day.” [Aubry pg 81]

Unfortunately, in 1815, Maman ‘Quiou was sent away. The Eaglet wept for two days straight, and was put into the care of a certain Countess Mitrovsky, “a creature of the Empress Maria-Ludovica and an intimate of Neipperg.” The loyal Meneval, who was also to be sent away, said good-bye to the little boy, and the change in the child’s demeanor was striking.

He was struck by the child’s earnest and melancholy air. He did not run to meet Meneval with his usual lively gestures and gay exclamations. He watched him, as he entered, with the utmost indifference. Countess Mitrovsky was with him. Every few seconds he would look at her as though in fear of a reprimand. After a few conventional phrases, Meneval took his hand and asked him if he had anything to say to his papa, for he was going soon to see him. The child looked at him sadly and went away, still silent, towards the embrasure of a distant window. Meneval bade good-bye to the Countess and Mme. Soufflot [one of the few remaining French waiting women], then, as he was leaving, stepped over to the little boy who stood watching him from the window. He bent low to bid him good-bye. And at that moment, he felt a tug at his coat and heard a trembling little voice say:

“Monsieur Meva, you will tell him that I still love him dearly.”

He was only four years old and for fourteen months he had not seen his father…

When he reached the antechamber, Meneval burst into tears. [Aubry, pgs 89-90]

Not long after this, the young King was delivered into the care of a tutor named Count Dietrichstein. The Eaglet, who was “dragged” by Countess Mitrovsky to meet Dietrichstein, refused to have anything to do with him, and Dietrichstein, while weeping, dramatically claimed to a friend “he cannot love me” as long as the last French women, even the aged nurse, were in Franz’s service. So Mme Soufflot, her daughter Fanny, and the others were banished, leaving Franz completely alone.

No more warmth about him, no more deep interest, no more deep interest, no soft hands to stroke his curls, no arms to clasp him too tight when he returned weary from a drive, no knees to spread him to let him rest, no more smiling reproofs for his shortcomings, no more love in short— real love, that is disinterested, unselfish love, love for himself and love for what he was. His mother was soon to leave him, to ascend to her throne in Parma. HIs grandfather Franz treated him kindly; but he had always sacrificed him for the interests of State and would sacrifice him again, if the Chancellor [Metternich] so ordered. As for his uncles, aunts, and cousins of Austria, however well they might treat him, however generous they might be, as certain of them were, they could not— and this was natural— help seeing in him, first of all, the son of Napoleon.

He was born with an affectionate disposition. He had loved his father infinitely. With his mother he had been tender and gentle. He had adored Mme de Montesquiou and Fanny Soufflot. Now he was compelled to close his heart. Brought up by men, raised only by men, but still too much of a child to become a man, he turned inward, escaped into the little universe he had made for himself with his memories of former days. For as young as he was, he had no hope, and he did not know there was a future. He was going to grow up that way, not unhappy if one only looks at the material content of life, but if one thinks of the needs of the heart, certainly not happy. [Aubry pgs 97-98]

Count Dietrichstein decided that he was going to stamp all the Frenchness out of the Eaglet’s mind, for he must become 100% a Habsburg. Nothing but German would be spoken to him, and when he clung to speaking French, crying that he didn’t want to be a German, that he wished to be a Frenchman, he was chastised, deprived of play and outings, and then, with the Emperor Franz’s approval, actually whipped. Yes— he was whipped. When he was only five years old, because he wouldn’t speak German.

But when even that wouldn’t work, Marie Louise sat him on her knee and told him solemnly that he must speak German to please his grandfather, which finally did the trick. Not long after this, she went to the little court in Parma. She requested for her son to go with her, but when Metternich refused, she acquiesced meekly.

Once so light-hearted and gay, the child became timid and mistrustful, and after the departure of his friends, the French women, and would lie to protect himself. In such cases he would be punished, not harshly, but not gently either. He shrank more and more into himself, accordingly, and since the world had grown hostile, he now began to offer it only a surface of indifference. [Aubry, pg 100]

He began to act out, destroying his copy books and mutilating his toys, but would also become sensitive to injustice or cruelty, like a dog being whipped or a bird eating a worm. He was told he would no longer be called Napoleon: he was to be called Franz. When he objected, he was “promptly silenced.” He became used to the name, and from here on out he was usually called Franz.

Franz still fought with Dietrichstein, who commented on his “laziness” and “ill will,” and his many quarrels with the prince, although he was happy to note in his letters to Marie Louise that it ended with “my victories.” Metternich had the boy closely followed, reports sent regularly and classified into a “ponderous file.” Meanwhile, his mother, off in Parma, when she wasn’t writing letters to her son exhorting him to pious obedience, made the feeblest attempt to defend the interests of the newly christened Franz— Franz was cut off from the succession of Parma after Metternich decided that this was in the best interests of the monarchy in Italy, Marie Louise was “readily brought into line by Neipperg, who owned her now body and soul.”

…She expressed herself as satisfied in a private letter of October, 1817:

“My son’s future has been determined. You know that I was never ambitious for thrones or States for him, but hoped he would be the richest and most charming gentleman in Austria.” [Aubry pg 110]

Meanwhile, Napoleon was kept on the island of St Helena, waiting for news from his son, but he heard not a word from his wife or a line from his son for six years. When he died, he was looking at Franz’s portrait, and left him many legacies, such as his books, engravings, papers, coffee service and the family house in Ajaccio, but Franz saw none of it. His mother, who was pregnant at the time with Neipperg’s son, didn’t even tell her son of his father’s death. She refused to accept Napoleon’s heart, which his will bequeathed her, because, as Aubry says, “she was more interested in the inheritance: she filed objection to the transfer of the six millions on deposit with Laffitte out of which the bequests of the Emperor were to be paid. She would not permit Marchand [Napoleon’s valet] to deliver to her at Parma Napoleon’s laces and the bracelet made of his hair.” Napoleon even begged her to take his last physician, Dr Antommarchi, into her service: she refused to even meet with him, palming the doctor off on Neipperg, who glad-handed Antommachi and pushed him out the door when he started asking too many questions about Franz.

Louise did moan about Napoleon’s suffering on St Helena while she was giving birth to Neipperg’s child, but she promptly forgot it. “She was a weak and frivolous soul. She would have grieved longer over her pet parrot, Marguerite. She even expressed astonishment that Madame Mere should have asked the British government for Napoleon’s body.” [Aubry pg 120]

One of the junior tutors named Foresti was given the task to tell the ten year old Franz that his father was dead.

The child began to weep and he wept a long time, doubtless calling up in his memory the pale face which had softened to such tenderness whenever it drew near his own. He sat down near the window, his cheeks, and his hands that covered them, wet with tears. Foresti himself was deeply moved and tried to comfort him. But the child did not hear him. [Aubry pg 122]

As Prokesch, his best friend of his short adult life, put it later:

“The prince wept for a whole day, almost without stopping. Then, suddenly, he mastered his emotions, dried his eyes, rose and paced the floor up and down. Not a word came from his lips. And several weeks passed before he alluded to his father’s death. He felt he must keep his grief to himself.”

Meanwhile, Franz was now thinking in German, but he still rebelled against his teachers, who, for years, beat him with the ferule (a type of paddle that resembled a long and large wooden spoon, the circular head often pierced with holes, and sometimes as large as a child’s head)— his grandfather the Emperor authorized “great severity” against him when he was being “stubborn”— but this stopped when it was clear beatings no longer had any affect. Except for brief months of pleasure during summer vacations at the castle of Persenbeug where Marie Louise deigned to leave Parma, Franz, who was completely without friends, was kept in solitude. He responded by withdrawing into himself and going into a fantasy world.

He dreamed, and gained freedom by dreaming. As a small boy he loved to play: now that he was growing up, it was still what he liked to do best. Never did child love to dream more than he: that escape from time, from responsibilities, from disappointments, that journey without end, where ideas, colors and forms mingled according to one’s fantasy! As soon as he could flee the watchful care of Foresti or of Collin, instead of working at his translations, his themes, or his arithmetic exercises, he would open the huge gilt-edged volumes given to him on his birthdays by his grandfather or the Archdukes and leaning his head on his hand, began to dream with his eyes upon the awkward, rather ridiculous illustrations of those days, in which one could see beplumed generals prancing besides their armies with spent cannonballs lying at their horses’ feet, while down in one corner an aide-de-camp would be reading an order and in the other an almoner kneeling besides a stretcher to confess a dying soldier.

Sometimes, bending low over an atlas, he would travel in spirit far out over the blue seas to the continents bordered in loud colors. One day, Matthias Collin came into the room and found him, with his cheek resting on a map. The little prince did not get up at his approach. His teacher thought he was asleep. But on going towards him, he saw the child’s eyes were wide open. The boy gave a start of surprise and blushed. He had been dreaming. Collin was more indulgent than Foresti. He did not punish him. [Aubry pg 132]

* * *

More to come in part two!

#napoleon II#franz duke of reichstadt#l'aiglon#eaglet#reichstadt#marie louise#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#octave aubry#king of rome#depressing shit#I'm sorry guys

92 notes

·

View notes

Photo

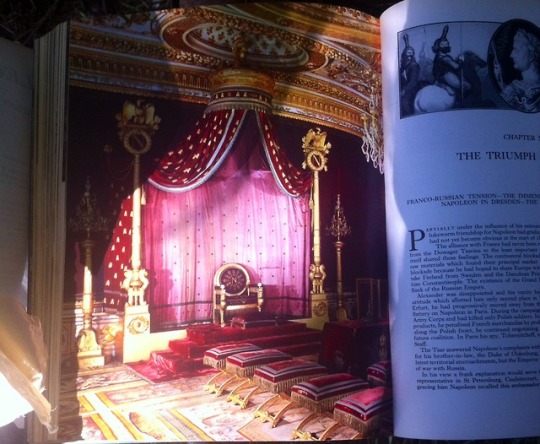

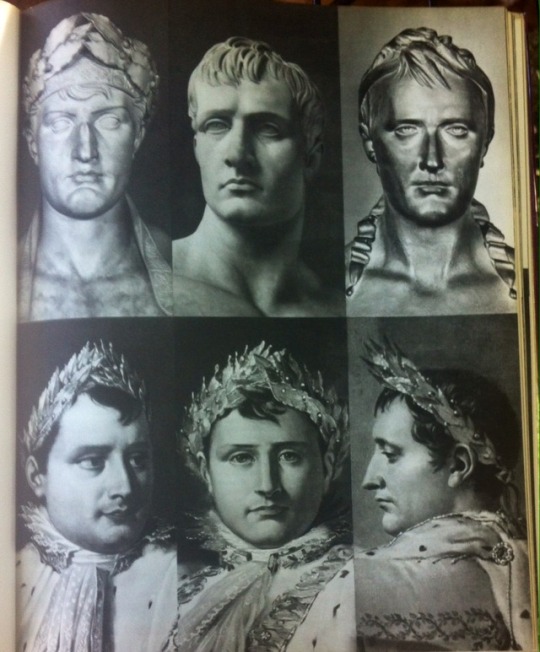

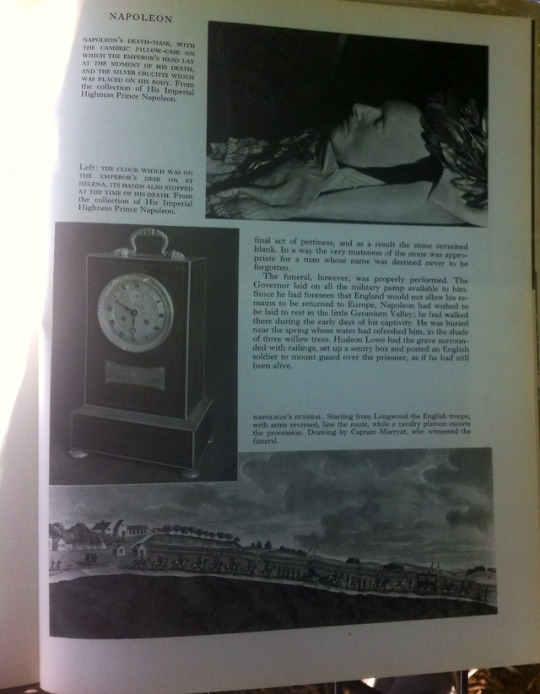

New Napoleon book for the shelf: Napoleon by Octave Aubry

#napoleon#bonaparte#Napoleon Bonaparte#Napoleon I#Napoleon Ier#Emperor Napoleon#Emperor Napoleon I#Octave Aubry#new book for the collection#my collection#my stuff#napoleon books#books on Napoleon#from the book shelf#napoleondidthat

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I finished it the other day and overall I thought was a really good biography! Obviously is outdated since it was published in the 1930s but I found it way more enjoyable than Castelot's bio. I think Castelot - and he seems to have been following a general theme in literature regarding Napoleon II - focused too much on the tragedy, dedicating an almost ridiculous amount of pages to the collapse of his father's empire and later on to his illness. Franz lamented on his deathbed that his whole story would be his birth and death, and it seems that for many authors indeed that's the case. I think that's a disservice to him. 21 years is a very short lifetime, but it is a lifetime nonetheless: he had friends, he studied, he went to balls and dinners, he charmed people, he was proud of his father and his legacy, he had dreams and plans for his future, he lived. So I liked that in Aubry's book Franz comes off as clever young man full of potential rather than a sad tragic figure whose life was only ever miserable.

I read the English edition available at the Archive, which annoyingly did not have a bibliography. I don't know if Aubry legit did not provide one or if it is a problem of this edition; he did provide footnotes citing sources, so that makes me think it's the latter. Also Aubry was a novelist and it shows, but you know what? The novel-like passages go so hard that I forgive him:

he was like a bird forever breaking his wings as each upward flight hurled him against the ceilings of Schönbrunn and the Hofburg

When I read this I actually had to stop and take a moment. Just the most breathtaking imagery casually thrown in the middle of a random paragraph about how Franz didn't like the Prussians.

I've been reading Octave Aubry's biography of Napoleon II and while I'm only half-way through, it already is better than Castelot's biography, mainly because Reichstadt is actually the main subject of the entire book. Castelot spent a crazy amount of time on the fall of the First Empire and Napoleon I on his book (almost half of it?? and it's not even a very long book??), Aubry only dedicates about 60 pages to this. Aubry also cites things, so that's another point for him. And while Aubry is critical about Marie Louise he is not weird about who was she sleeping with, so I appreciate that.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Metternich: Master of Napoleon's son.

When someone reads about the short and desperate life of Napoleon's son; the King of Rome (Napoleon II, L'aiglon, the Duke of Reichstadt or Franz) soon realizes that, in fact, his life was never his, but Metternich's. Of course, the signs are not at first glance when one barely gets to know the history between these two (and other) characters, even more so knowing that it is said that they only spoke directly with the other on five counted occasions.*¹ We know (or in case you don't, dear reader, you can ask me for the context in private or by asking me to write a blog about it) his governors; his tutors: Count Dietrichstein, captain Foresti and professor Collin -initially - but who was behind all of them? It was Prince Metternich, of course, being he the one who assigned the men to "take care" of the King of Rome, replacing with them his french ladies that the boy loved so much; this way, the Austrian Chancellor guarding since his arrival in Austria the little heir of the "Ogre". It was his work - that is, his careful administration, his observations and movements from far away - that doomed from such a young age the boy who once had everything, only to have nothing the next day.

I bring to you this excerpt from "The King of Rome: Napoleon II, L'Aiglon" by Octave Aubry, which although it isn’t the most descriptive of the point to be discussed in this blog, allows us to peek for a moment at how was the dynamic between Klemens and the boy... or rather, how the chancellor had control of the life of the King of Rome from a distance.

Dietrichstein's reports to Marie Louise make frequent complaints about the child's laziness and ill-will, in spite of his great intelligence. And what can that mean except that he was still resisting? But under that exacting ferule, gripped in a mold that was crushing his instincts and his will more and more, how could the little King fail to yield in the long run? And in fact he did yield, only to rebel again, be punished once more, and submit a second time. He was rewarded with toys, albums, favorite dishes, sweets, picnics in the country, the circus, a dog, some birds. His grandfather ordered a handsomely chased shotgun for him, just his size, and one day invited him to go hunting, not as an onlooker now, but as a participant. Among Dietrichstein's papers is one of the child's corrected exercises, a little composition describing with a naive importance that day of relaxation and undisguided pleasure. August 25, 1819. "To-day I went hunting with my grandfather. We drove as far as the suburbs of Hassendorf where we left the carriage and where the other hunters were waiting for us." I was with my grandfather all the time. We went to the shelters, where I was given a gun, which caused me great pleasure. My grandfather, my Uncle Franz and I went through the shelters to come out on the other side. There my uncle left us to take up the post that had been assigned to him. We waited for the game to come out of the tickets, while the other wing was making a turning movement. After a long wait, the game appeared. I tried a shot, but missed my aim. The other wing was more fortunate than ours. In the beginning my grandfather had no luck, but later on he shot very well. I shot once more. The aged Councilor George, who saw me, came toward me and told me that the shot had frightened him. He took off his hat, showed me the eagle on it, and said he had caught the bird. That made me laugh.” (…) Victories over a child sad words indeed to register! Though, of course, not so much over a child as over the heir of Napoleon Bonaparte! Count Maurice was a prisoner of the method he was applying. His task was to form a character, and he was without character himself. He could be a tutor to the Prince of Parma, but never a friend. Reports were also regularly sent to Metternich. Everything the child said and did, his work, his amusements, his caprices, his tempers, his tears, his laughs were all set down on huge sheets of paper, and submitted to the Chancellor; and the latter, adjusting his lorgnette, read attentively and classified them in a ponderous file. He seldom referred to such reports at his daily audiences with the Emperor; for he affected a manner of polite indifference toward the young prince. (…) But was it not enough for Prince Metternich to have reduced the son of his enemy to such a pass?*² No, that hostage had also to change in appearance as he had changed in dress and decorations. That submissive little Frenchman, so alone and so helpless, who had so stoutly resisted his governors, had to become a spiritless, satisfied subject, without personality and without initiative, a pawn for the Chancellor to manipulate at will on the diplomatic chessboard for, after all, who could say but that he might prove useful later on in some subtle combination? And the Chancellor had eyes which were never so full of tears as not to be able to see far, far into the future. REFERENCES: King of Rome: A Biography of Napoleon's Tragic Son André Castelot*¹ This means, reducing him from a crown prince of the French empire, to a prince of Parma, to an Austrian Duke with no political power, or no power at all.*² Source.

#klemens von metternich#metternich#the king of rome#napoleon ii#duke of reichstadt#l'aiglon#marie louise#francis ii#napoleonic wars

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

SW OC Masterpost (or smth)

The thing ins parenthesis are there races, if they're in italics it means they're races I created, if they're in bold they're races I created that don't yet have a name haha...

Mains :

- Asha (She has a tail ok) - Kana Kiltleca (Human) - (Eun-ji) Beryl Lee (Antroposae) - Lili (Human)

Supporting Cast (ig) :

- Nora (Human) - Priamos (Saxuerec) - Cyclamen (Plant Humanoïde) - Aaron (Human) - Raxle Uhead (Vissle) - Kerwan (Idk men) ----------------------------------- - Po’ll Krimar (Human) ----------------------------------- - Meduss (Gorgon Type Alien) - Lygie (Human and Theelin) - Brunhilde (Human) - Ezekiel (Twi’lek) - Aria (Human) - Octave (Human) ------------------------------------ - Artair (Human) ------------------------------------ - Dargo (Zabrak)

Jedi :

- Sezny Eskrsimm (Human) - Nausicaa Rimefaul (Human) - Vaj Kravhenn (Thruun) - Krystah Martano (Zygerrian) - Paloma/Malu (Human) - Kritte’opuawi’llotho (Chiss) - Lesdesi Groury (Theelin) - Omaira (Human)

Clones :

- Ryley - Crash - Hyott - Gin - Dee - Nix - Calypso - Alley - Carmin - Mulberry - Fig - Jacandra - Forgie - Oyk - Sloth - Phantom - Puma

Epihl Fam :

- Neven (Human, Mandalorians Origins) - Celia (Human, Mandalorians Origins) - Kisa (Human) - Janx Epihl (Mandalorian)

Mandalorians :

- Kha Rook (Mon Calamari) - Luts Krarmi (human) - Ti’llandra Degor (Theelin) - Hojal Degor (Theelin)

Bounty Hunters :

- Li (Pantoran) - Loris (Pantoran) - Creenk aka Sylvain (Trandoshan) - Hyperion (Human) - Lahek (Pyke)

Kids :

- (Bong Cha) Faye Lee (Antroposae/Clone/Human?) - (Haneul) Ashton Lee (Antroposae/Clone/Human?) - Tukyaan Ry (Togruta) - Oatu (Zabrak) - Maqok (Zabrak) - Laf (Rodian)

Antroposae :

- Dal-Rae - Soomin - Kwan (desert antroposae) - Ailisieu (archipelago antroposae) - Chin (archipelago antroposae) - Byeol (lowlands antroposae) - Yona (montain antroposae) - Heejin (cave antroposae)

Stormtroopers (all humans):

- Caddy - Aubry - Benjamin - Steve - Bob

Animals/Droïds :

- Sandy (Hamsani) - Z-0-r (Droïd) - Stripey (Loth-cat) - Garbage (Loth-cat)

#haha so um...#i'm making them all identity cards ig...#every talks#star wars#star wars oc#every's life

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the favorite historical figure ask game: 5, 6, and 9

5. What is the most ridiculous statement on him you have ever read?

The most ridiculous statements on him I probably have not even read as I have not studied the Second Empire, when people tried to turn Eugène into some kind of hero and a shining example of chivalry and loyalty, which he clearly was not.

Krettly in his memoirs calls him »le brave et vertueux Eugène, le prince sans tache, celui qui refusa tout pour rester fidèle à son bienfaiteur« (»brave and virtuous Eugene, the flawless prince, the one who refused everything in order to remain faithful to his benefactor«). Which is, when you look a little closer at what really happened between Napoleon and Eugène during the last couple of years, just not so. And considering that meeting his mother, stepfather and friends in Munich already went against his modesty (according to Darnay), he probably would be quite embarrassed by that kind of talk.

The most painful and, while not entirely ridiculous, at least unfair statement would come from Octave Aubry who called Eugène »the most ungrateful of them all«. (»De tous les proches de l’Empéreur, avec les moins d’excuses, il est le plus ingrat.«)

6. In your opinion, what is his biggest flaw?

Lack of self-confidence, a deep-rooted insecurity and, related to that, the wish (read: need) to make himself loved by everyone. Throughout his life, Eugène always needed somebody to look up to, whose praise and approval he tried to win. As Michel Kérautret states: He always remains »le fils«, the son. He never truely came into his own, was always looking for a father figure, very ready to fight for somebody else, but never for himself.

9. What is your favourite depiction of him (e.g. in painting, sculpture etc.)?

There’s a miniature made after Gérard’s portrait that I like because it really shows a very boyish, »baby face« Eugène that I assume captures him quite well:

I'm also fond of this one, still as Colonel in the Guard:

Among the "official" portraits as viceroy I prefer the second one by Appiani as I find it less embellished - all contemporaries agree that Eugène was not truely handsome.

It also seems closer to this bust:

And finally, the one that touches me the most, the last portrait, made in Munich by Stieler, when he clearly is already worn-out by depression and his illness (this one is today in Munich's Residence Museum, by the way):

Thank you so much for asking!

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mme. Bertrand tries to throw herself off the Bellerophon

(St. Helena, by Octave Aubry)

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

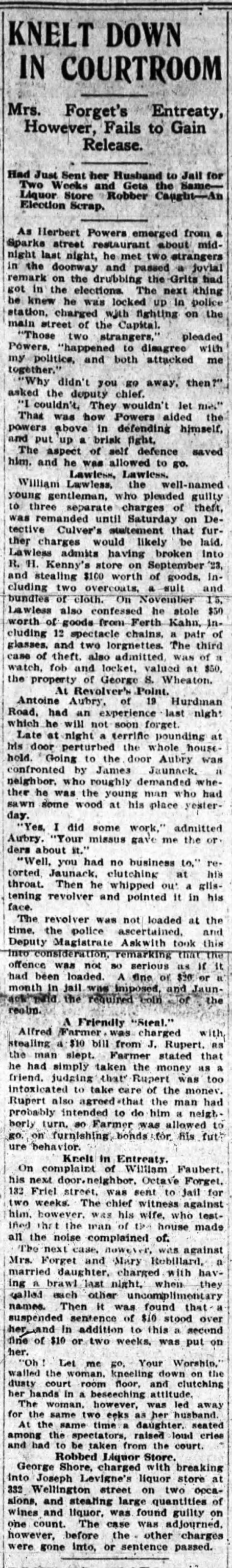

“KNELT DOWN IN COURTROOM,” Ottawa Journal. December 13, 1911. Page 9. ---- Mrs. Forget's Entreaty, However, Fails to Gain Release. ---- Had Just Sent Her Husband to Jail for Two Weeks and Gets the Same - Liquor Store Robber Caught - An Election Scrap ---- As Herbert Powers emerged from a Sparks street restaurant about midnight last night, he met two strangers in the doorway and passed jovial remarks on the drubbing the Grits had got in the elections. The next thing he knew he was locked up in police station, charged with fighting on the main street of the Capital.

'Those two strangers,’ pleaded Powers, ‘happened to disagree with my politics, and both attacked me together." .

‘Why didn’t you go away, then?’ asked the deputy chief.

"I couldn't, They wouldn't let me.'

That was how Powers aided the powers above in defending himself, and put up a brisk fight.

The aspect of self defence saved him,, and he was allowed to go.

Lawless, Lawless William Lawless, the well-named, young gentleman, who pleaded guilty to three separate charges of theft, was remanded until Saturday on Detective Culver’s statement that further charges would likely be laid. Lawless admits having broken into R. H. Kenny’s store on September 23, and stealing $100 worth of goods, including two overcoats, a suit and bundles of cloth. On November 15, Lawless also confessed he stole $50 worth of goods from Ferth Kahn, including 12 spectacle chains, a pair of glasses, and two lorgnettes. The third case of theft, also admitted, was of a watch, fob, and locket, valued at $50, the property of George S. Wheaton.

At Revolver’s Point Antoine Aubry, of 19 Hurdman Road, had an experience last night which he will not soon forget.

Late at night a terrific pounding at his door perturbed the whole household. Going to the door Aubry was confronted by James Juunack. a neighbor, who roughly demanded where he was the young man who had sawn some wood at his place yesterday.

"Yes I did some work," admitted Aubry. "Your missus gave me the orders about it.'

"Well, you had no business to," retorted Jaunack, clutching at his throat. Then he whipped out a glistening revolver and pointed it in his face.

The revolver was not loaded at the time, the police ascertained, and Deputy Magistrate Askwith took that into consideration, remarking that the offence was not so serious as if it had been loaded. A fine of $20 or a month in jail was imposed, and Jaunack paid, the required coin of the realm.

A Friendly ‘Steal.’ Alfred Farmer was charged with stealing a $10 bill from J. Rupert, as the man slept. Farmer stated that he had simply taken the money as a friend, judging that Rupert was too intoxicated to take care of the money. Rupert also agreed that the man had probably intended to do him a neighborly turn, so Farmer was allowed to go on furnishing bonds for his future behavior.

Knelt in Entreaty On complainant of William Faubert, his next door neighbor, Octave Forgert, 132 Friel street, was sent to jail for two weeks. The chief witness against him, however, was his wife, who testified that the man of the house made all the noise complained of.

The next case, however, was against Mrs. Forget and Mary Robillard, a married daughter, charged with having a brawl last night, when they called each other uncomplimentary names. Then it was found that a suspended sentence of $10 stood over her and in addition to this a second fine of $10 or two weeks, was put on her.

‘Oh! Let me go. Your Worship," wailed the woman, kneeling down on the dusty courtroom floor, and clutching her hands in a beseeching attitude,

The woman, however, was led away for the same two weeks as her husband.

At the same time a daughter., seated among the spectators, raised loud cries and had to be taken from the court.

Robbed Liquor Store George Shore, charged with breaking into Joseph Lavigne’s liquor store at 332 Wellington street on two occasions, and stealing large quantities of wines and liquor, was found guilty on one count. The case was adjourned. however, before the other charges were gone into, or sentence passed.

#ottawa#police court#street fight#assault#threats of violence#carrying a revolver#uncomplimentary names#robbery#liquor store#theft#stolen liquor#stolen goods#sentenced to prison#ottawa jail#fines or jail#suspended sentence#history of crime and punishment in canada#crime and punishment in canada

0 notes

Quote

He is said to have composed part of a poem on the deliverance of Corsica, in which slumbering in one of her numerous Caverns, the Genius of his country appeared to him in a dream, and putting a dagger in his hand called on him for vengeance. This was the commencement of the poem, and whenever he added anything to it, he would go and dig up a rusty short sword which he called his dagger, and enthusiastically repeated to one of his companions the lines he had just written, after which he returned to bury his poignard.

J. W. Robertson, The Life and Campaigns of Napoleon Bonaparte, p. 7. Napoleon you weirdo. Fortunately he got over the Corsican nationalist phase, eh.

P.S.: I don’t really confide that much in Robertson’s accuracy; this same anecdote, less detailed, is told by Octave Aubry (who, in his turn, is sometimes inaccurate). The lad who had to listen to all that crap about daggers (Des Mazis?). Poor guy.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Des concerts à Paris et autour

Mai 02. Antoine Schmitt, Violaine Lochu & Garth Knox (fest. OW-AO) – Le Générateur (Gentilly) 03. Best Available Technology + Adrien Kanter + Gaël Segalen – L'Alimentation générale (gratuit) 03. Meat Wave – La mécanique ondulatoire 03. Seabuckthorn + Raoul Vignal + Albane Aubry – Les 3 baudets 04. Qual – Espace B 04. Gravels + One Lick Less – Centre culturel suisse 04. Group A + N.M.O. – Instants chavirés (Montreuil) 04. Vale Poher + Hotel – Mains d'oeuvre (Saint-Ouen) 04. Jeff Mills : Spirale Deluxe – La Seine musicale (Boulogne-Billancourt) 05. La Novia & Yann Gourdon : “In C” de Terry Riley – Centre Pompidou 05. La Chasse + Copydex + Hess + Léopard + Yeah You – église Saint-Merry 05. Poni Hoax + Yula Kasp – La Station 05. C.A.R. + Léonie Pernet + Lil'Sugar – Le Klub 05. Anetha – La Machine 06. Richard Francès & Konpyuta – centre Montgallet (gratuit sur résa) 06. Esmerine + Bärlin – Espace B 06. Little Nemo + Babel 17 – Candy Shop 06. Les Hôpitaux + Skiing + Dubais + Disc Jockey – L'Époque 06. Paris Acid Boys + Peev (Marathon électronique) – 6, rue de La Pointe (Romainville) 07. Infecticide + Sydney Valette (fest. Restons sérieux) – Supersonic (gratuit) 09. Blanck Mass – Point FMR 09. Erevan Tusk + Nick Grey & The Random Orchestra + Franck Rabeyrolles + Hop on Me – La Java 10. Zombie Zombie + Tomaga + None + Tristesse contemporaine (dj) (Zombie Jamboree fest./10 ans de Julie Tipex) – La Machine 11. Cocaine Piss + Miss France + The Sunflowers – Supersonic (gratuit) 11. Oiseaux-Tempête + L'Effondras + Noyades – Trabendo 11. Laetitia Sadier + Solo Astra + Beat Mark (Le Beau fest.) – Espace B 11. Ambassador 21 + Lying Figures + Wild + Yorblind – Bus Palladium 11. Violent quand on aime + Tamara Goukassova + Numuw – L'Époque 12. Wire + Blackmail + Teknomom – La Maroquinerie 12. Fabrizio Rat + Camera – La Station 12. Étienne Jaumet + Gilb'r + Tolouse Low Trax (Zombie Jamboree fest./10 ans de Julie Tipex) – La Machine 12. Manu le Malin + AZF + 14anger + Sinus 0 – La Machine 12. Rebekah + Jonas Kopp + Linkwood + Saint-James – Concrete 13. Collection d'Arnell Andrea – Batofar 13. Jumo + Giorgia Angiuli + Nova Materia (Sound Design Party|D'Days) – Gaîté lyrique 13. Mammane Sadi + Novella + Blondi's Salvation + Biche + Mohamed Lamouri (Le Beau fest.) – La Station 13. Graal + CIA débutante + Lazy Terms + Pierre-Yves Billet & Corentin Lahaye – Treize 13. Headless Horseman + Ventress + Blindr + Illnurse + Paulie Jan – Trabendo 13. Bas Mooy + UVB + Charlton + Sleeparchive – Nuits fauves 14. Lee Patterson – péniche Adélaïde 14. Thee Oh Sees + Häxxan – Trabendo 15. Chameleons Vox + Blue Mountain Expansion – Supersonic 15. James Ferraro + Ducktails + Typhonian Highlife – Instants chavirés (Montreuil) 16. ToutEstBeau + Fiodor Novski & The Shiners – Espace B 16. Guerre froide + Wallenberg + The Saint Cyr & Pascale Le Berre – Petit Bain 17. Xiu Xiu + Le Prince Harry + Delacave – Petit Bain 18. Poison Point – Angora bar (gratuit) 18. Molecule + Pierre Berthet & Rie Nakajima (Soirée sonore) – Centre Pompidou (gratuit) 18. Jac Berrocal, David Fenech & Vincent Epplay – Pop Culture shop (gratuit) 18. Philippe Laurent + Das Ding – La Java 18. Xamān + Perrine en morceaux + Chaos E.T. Sexual – Olympic café 19. Eloïse Descazes & Eric Chenaux – Médiathèque musicale (gratuit) 19. Vril + Henning Baer + James Ruskin + DJ Pete + Parfait – Dock Eiffel (La Plaine-Saint-Denis) 23. Sleaford Mods + Mark Wynn – Gaîté lyrique 23/24. Pascal Bouaziz : musique live pour "Nos féroces" de Séverine Rième (Rencontres chorégraphiques de Seine-Saint-Denis) – théâtre Berthelot (Montreuil) 24. Death in Vegas – Gaîté lyrique 24. God is an Astronaut – Flow 25. Collectif_Sin (Villette sonique) – Wip 25. Keiji Haino, Merzbow & Balasz Pandi + Afrirampo + Puce Mary (Villette sonique) – Trabendo 25. RA + Drab Majesty – Espace B 26. Soviet Soviet + Empereur + Dead + Scaffolder – Supersonic (gratuit) 26. Royal Trux + Groupe Doueh & Cheveu + Uranium Club + Bernardino Femminielli (Villette sonique) – Grande Halle de La Villette 26. La Colonie de vacances (Villette sonique) – Périphérique 26. Actress + Jacques Greene – Nuits fauves 26. BLNDR + Natural/Electronic.system. – Batofar 26. Marcel Fengler + Scan X + Chris Honorat + Théophiluss – Rex Club 27. Annette Peacock + OOIOO (Villette sonique) – Cité de la musique|Philharmonie 27. Marie Davidson + Doomsday Student + Pizza Noise Mafia + Deena Abdelwahed + Mdou Moctar... (Villette sonique) – Parc de La Villette (gratuit) 28. Princess Nokia + Randomer + Mandolin Sister + The Goon Sax + Volition Immanent... (Villette sonique) – Parc de La Villette (gratuit) 28. Einstürzende Neubauten + Jenny Hval – Grande Halle de La Villette 29. Ruins + Akaten + Zubi Zuva X + Acid Mother Temple SWR + Acid Mother Kirisute Gomen + Psyche Bugyo + Makoto Kawabata + Zoffy + Atsushi Tsuyama + Emiko Ota (Japanese New Music) – Gaîté lyrique 29. MSHR + Max Eilbacher & Duncan Moore + Acqua Dentata + Meryll Ampe & Romain Arnette – tba 29. Psychic TV 3 + Aikula – Petit Bain 30. Broken Social Scene – L'Alhambra 31. The Make Up + The Blind Shake (Villette sonique) – Cabaret sauvage

Juin 01. Kim Myrh & Lasse Marhaug + EKT (EriKm, Harald Kimmig & Olaf Tzschoppe) – Instants chavirés (Montreuil) 01. Society of Silence + Charles Fencker – Nuits fauves 02. Ansome + Myler + Ossian + Ayarcana + 138 – La Machine 03. Sister Iodine + Les Hôpitaux + Warsawwasraw – La Station 04. Karima Walker + Mikko Savela – tba 04. Anetha + Kas:st + Octave One + Paranoid London + Rodhad... – Vélodrome (Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines) 06. John Russell + Michel Doneda & Lê Quan Ninh – Instants chavirés (Montreuil) 08. Primal Scream – Gaîté lyrique 08. Mikky Blanco (Loud & Proud) – tba 08. Soror Dolorosa + Schonwald – Bus Palladium 08. Sida + Cellular Chaos – Instants chavirés (Montreuil) 08. Phase Fatale + Rendered + Sarin + Schwefelgelb – Nuits fauves 09. Blurt – Espace b 09. Maud Geffray + Chloé + Voiron + Casual Gabberz + Krampf – Gaîté lyrique 09. Skinny Puppy + Carpenter Brut (fest. Download) – Base aérienne 217 (Brétigny/Orge) 10. Mesparrow (fest. TaParole) – La Marbrerie (Montreuil) 10/11. Richie Hawtin + Flying Lotus + Jon Hopkins (dj) + Moderat + Motor City Drums Ensemble + Recondite + A Tribe Called Quest + Solange + Nicolas Jaar + Parcels + Jessy Lanza + Action Bronson + Anderson Paak + Abra... (We Love Green) – Bois de Vincennes 11. Inhalt + Poison Point – La mécanique ondulatoire 11. Amanda Palmer & Edward Ka Spel – La Cigale 14. King Dude + Suzie Stapleton – La plage de Glazart (gratuit) 14. Charlemagne Palestine – musée d'Art et d'Histoire du judaïsme 15. Arlt + Bégayer (fest. TaParole) – Instants chavirés (Montreuil) 16. Warum Joe + Asphalt + Last Night + Police Control + Colombey – La Station 17. Miossec (fest. TaParole) – La Parole errante (Montreuil) 22. Joëlle Léandre & Mike Ladd – Galerie Hus (sur résa) 25. Matt Elliott (fest. BD6Né) – médiathèque Marguerite Duras 28. Blondie – Olympia 29 > 02.07. Belmont Witch + Mariachi + Ella a. Thaun + Nana Benamer + Sleep Loan Sharks + Big Meufs + Miaux + Méryll Ampe + Félon + Las Kellies... (fest. Comme nous brûlons) – La Station 30. Geneviève Pasquier + Position parallèle + Black Light Ascension – Le Zèbre de Belleville 30. Objekt + Rrose + Paula Temple (Macki music fest.) – La Machine 30>10.07. Air + Metronomy + Jarvis Cocker & Chilly Gonzales + Savages + Devendra Banhart + Michael Kiwanuka + Tindesticks présentent "Minute Bodies" + James Vincent McMorrow + Lady Sir (Rachida Brakni & Gaëtan Roussel) + Kate Tempest + Calypso Valois + The Color Bars Experience joue Nick Drake (fest. Days Off) – Philharmonie

Juillet 01. Ke/Hil + Kommando + Tunnels of Āh + AntiVallium – Le Zèbre de Belleville 01/02. Soichi Terada + Antal b2b Hunee + San Proper + Margie + Renart + Mézigue + Rendez-vous... (Macki Music fest.) – parc de la mairie (Carrières/Seine) 02. The Color Bars Experience joue Nick Drake (Days Off) – Salle de répétition|Philharmonie 02. Tindersticks : cineconcert sur "Minute Bodies" de Suart Staples (Days Off) – Cité de la musique 03. Metronomy (Days Off) – Salle Boulez|Philharmonie 04. Savages + Kate Tempest (Days Off) – Cité de la musique 05. Group Doueh & Cheveu – Institut des Cultures d'Islam 06. Devandra Banhart + Lisa Hannigan (Days Off) – Salle Boulez|Philharmonie 07. Ancient Methods + Marie Davidson + Voiski + Varg + Exal + BLNDR + Carl Craig + Marcel Dettmann + Nina Kraviz + The Martinez Brothers + Jackmaster + Levon Vincent + Konstantin + Peggy Gou + Hugo LX + Codex Empire (Peacock Society) – Parc floral (Vincennes) 07/08. Daikiri + Gloria + Tomaga + Le Villejuif Underground + The Limiñanas + Hey Colossus + Fai Baba + Stratocastors + Cocaine Piss... (La ferme électrique) – La Ferme du Plateau (Tournan-en-Brie) 08. Sourdure + Piu Piu (dj) + N.M.O. + Danny L. Harle (dj) (Siestes électroniques) – musée du Quai Branly (gratuit sur résa) 08. Air (Days Off) – Salle Boulez|Philharmonie 09. Jarvis Cocker & Chilly Gonzales (Days Off) – Cité de la musique 08. Dixon + Kaytranada + Apollonia + The Black Madonna + Moodymann + DVS1 + Midland + Romare + Tommy Genesis + Avalon Emerson + Jlin + AZF + Raheem Experience + Fils de Vénus + Bamao Yende + TGAF (Peacock Society) – Parc floral (Vincennes) 09. Carl Stone (dj) + Manu le Malin (dj) (Siestes électroniques) – musée du Quai Branly (gratuit sur résa) 10. Sufjan Stevens, Bryce Dessner, Nico Muhly & James McAlister (Days Off) – Salle Boulez|Philharmonie 15. Blawan – Rex Club 21. Hocico + Shaârghot – Petit Bain

Août 25>27. PJ Harvey + The XX + At the Drive In + Franz Ferdinand + Cypress Hill + Ty Segall + Rone + The Kills... (Rock en Seine) – Parc de Saint-Cloud

Septembre 21. Ennio Morricone – Bercy Arena 22. She Past Away – Petit Bain 27. Sigur Ros – Grand Rex ||COMPLET|| 28/29. Sigur Ros – Grand Rex

Octobre 03. Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds – Zénith ||COMPLET|| 04. Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds – Zénith 14. Wardruna – La Cigale 19. Nosfell – Café de la danse 23. Mogwai – Grand Rex 28. Peter Hook & The Light – Le Trianon

Novembre 15. Igorrr – La Maroquinerie 21. Sun Kil Moon – Gaîté lyrique

en gras : les derniers ajouts / in bold: the last news

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The short and very miserable life of Napoleon II, aka the Eaglet, aka Franz, Duke of Reichstadt: PART TWO

Although the beatings had ceased, Franz’s life continued in refined isolation until his fifteenth year, when his cousin Franz Karl married the beautiful and charming Sophie of Bavaria.

She was only six years older than he, a fine, pretty girl of sweet features and merry lips, with light chestnut brown hair arranged in great loops on her temples. She had done away with the stiff sumptuousness of her apartment at the Burg, and refurnished it in a more intimate atmosphere. In her salon, with its mahogany furniture covered in yellow velours and minus the usual gilding. Reichstadt would often come and sit beside her, looking through the pictures in her albums while she would paint, or play graceful Italian airs on her piano. And they would talk. She sided with him when things went wrong, pitied him, loved him. She was the only one to whom he could talk to with an open heart. Thanks to Sophie, in those troubled years of adolescence when the child is disappearing and the man is trying to find himself, he had at last found what had been refused him for so long: a friend. [Aubry pg 140]

Franz was growing into a handsome young man, with his mother’s blue eyes and blond curls, but his father’s striking bone structure and deep-set eyes, and the emotional Bonaparte temperament. Though he was robust and “glowing with health” as a baby, by the time he was an adolescent he became more frail. Doctors said he had a “scrofulous tendency,” which was 19th century medical gobbledygook for some sort of disorder connected with the lymphatic glands. It seems to me that this kid was isolated and beaten for years, and suffered from pretty severe depression— on top of that, he didn’t eat (Aubry records that he had “a poor appetite”). Throw in an inherited tendency from his mother to have lung trouble, I’m not surprised he struggled with illness going forwards.

Apart from Sophie, there was no one to really look out after him. She encouraged him, his interests, his passions, his keen desire to be a soldier, his love for his father and of France, helping undo all the years of Habsburg brainwashing. As the years passed, he even learned how his father’s executors were continually frustrated in trying to pass on the legacy his father had tried to leave to him. “They had been kept away, or driven away: or else the relics they had brought had been politely taken from them and stuffed away into strongboxes, thus cheating the son of the only material inheritance his father had left him. Who had so ordained? Metternich, none other!” [Aubry pg 154]

Metternich, the true ruler of this not-so-holy and not-so-Roman empire, was the one man who had schemed and plotted to keep Franz so isolated and alone. Metternich, and this is no exaggeration, hated every atom of Franz since he was a baby, and he never let Franz forget it. Franz was under police surveillance at all times: the Chancellor had the Corsican’s son in his grasp, and would not lose him. He wouldn’t even allow the young man contact with his own grandmother, Letizia, Madame Mère, now eighty years old and blind from cataracts. He wouldn’t even allow a single letter— a single sentence.

That statesman, who had a government for a soul, had made Austria a prison for him instead of the home it should have been! Metternich had been his father’s enemy; he was his enemy too, and always had been! The young man felt the hostility underneath the Chancellor’s icy courtesy, and he hated him. Altogether without basis in fact are those accounts of numerous conversations between Metternich and the Duke of Reichstadt during this period. Prokesch maintains that the Minister talked to the Prince just five times in seventeen years. Far from seeking to influence the Duke of Reichstadt during this period, Metternich avoided all contact with him. He hated him as he hated his father. The likeness to the Corsican which he found again in the young man’s features offended him like an insult. He could not bear the sight of that forehead, the sound of that voice. At a Court reception on the evening of the Duke’s eighteenth birthday, the Chancellor paid the obligatory compliments and turned away hastily. Those who spoke to him immediately afterwards found him more distant than usual. As soon as he could do so without attracting attention, he left the palace. [Aubry pg 162]

After years of being force-fed Austrian propaganda, Franz had started reading as much as he could about the greatness of Napoleon— obsessively reading Las Cases’ Memorial of St Helena, which he found on one of the top shelves of the library. Imagine his feelings when he read his father’s will for the first time, discovering what affects and relics were left to him, but which he would never see, thanks to Metternich’s machinations (and Louise’s clumsy attempts to lay claim to Napoleon’s inheritance, which had sabotaged the work of the executors in the first place, did not cease until 1837). Franz, fascinated with his father’s campaigns and personal history, threw himself into his studies. Through books, he vicariously experienced Lodi, Arcole, Marengo, the Pyramids, Jena, Austerlitz… He became drunk with the glory of the past. A spell had been cast, and Franz became determined to make his father proud of him. When one of his tutors began to lecture him on his father’s shortcomings, Franz replied impatiently:

“The actions of great men are not to be weighed with ordinary scales.” [Aubry pg 156]

Franz was slowly shedding the relationships of his childhood. When, upon Neipperg’s death in 1829, he had discovered his mother had contracted a morganatic marriage with the one-eyed Neipperg, he “felt deeply insulted and humiliated.” He was enraged enough to discover just that: of course, keep in mind he had no idea that she was sleeping with Neipperg and had given Franz two illegitimate half-siblings while his father was living with the rats on St. Helena. I doubt he would have ever talked to her again if that was the case. Even without knowing that, he withdrew, “his letters were less affectionate and he mentioned her name more rarely. She had been expected at Schoenbrunn for the summer. Her son learned with relief that she preferred to take a cure in Switzerland.” [Aubry pg 160]

Of course, Louise kept doing her thing, weeping for Neipperg over “gay dinner tables and at the opera,” being annoyed whenever the name of Napoleon reached her ears, and then finding “a substitute for the one-eyed general in the person of the Count de Bombelles, at first Grand Master of her Household, then her lover, and then finally her third husband.” [Aubry pg 161]

Meanwhile, for years Franz had struggled with depression. The July Revolution had happened, with the kind and comfortable Louis-Philippe installed on the throne, and even though the King of Rome was still a popular figure in France, with perhaps a chance to ascend the throne, Franz was still, for all intents and purposes, a prisoner. And the older he got, the more obvious this became. Suggestions to become a monarch in Poland or Greece were pushed asides by Metternich. Attempts by his uncles Lucien and Joseph to discuss Franz’s future with Metternich were completely blocked. All he wanted to do was to start his military career, and make himself useful, but he couldn’t even join his regiment, or even visit his mother in Italy. His health was floated as the reason why he should stay inactive, but Franz doubted this was the only reason. Bouts of rage alternated with deep sloughs of “sadness and tedium,” and he could barely summon the interest to hold a conversation. Not surprisingly, his mother lacked sympathy. In 1830, when Louise was summering in Baden, taking the waters, she “rebuked him for his apathy. She could not understand why her son could be ‘so little like other young people.’” [Aubry pg 181]

It grew worse a year later. Italy was on fire with the revolutionary activities of the Carbonari, and Louise had fled Parma in fear of her life. Franz pleaded with his grandfather to let him go rescue her, but Metternich intervened. Let the son of Napoleon, the King of Rome, go to Italy, where his father won his own fame? Of course not! Emperor Francis gave into Metternich, and poor Franz was left feeling torn between misery, fury and desperation. Even Prokesch, his best friend apart from Sophie—a major in the Viennese army, a loyal soldier, scholar and diplomat who had worked for Metternich, but had defied him on a few occasions-- couldn’t calm him.

His despair was palpable. He knew he would spend his entire life bound and trapped, with Metternich as his jailer.

The young man had sealed himself up in a silence that was almost complete, venting his feelings at the most in talks with Sophie and Prokesch, during which he expressed many severe judgments on members of the Imperial family. He loved Sophie and he had an affection for his grandfather, but he did not like the Empress, fond as she was of him. He thought the Archduke Ferdinand, heir-apparent and King of Hungary, was a ninny. [Editor’s note: Ferdinand was actually a brain-damaged hydrocephalic epileptic who couldn’t even consummate his own marriage with his wife Maria Anna, married in 1835.] He hated the Archduke Franz Karl, Sophie’s husband, calling him deceitful, mean and vulgar. Table conversations at the Hofburg were stupid, the Court life was cheap and in bad taste. Comparing himself with those pious, submissive and conceited Archudukes and those ugly, insipid Archduchesses, he felt himself of a superior race. He even said one day— and Prokesch recorded the words in his secret notes:

“If Josephine had been my mother, my father would not have gone to St. Helena, and I would not be languishing in Vienna. My mother certainly has a kind heart, but no backbone! She was not the wife my father deserved!”

And he added, burying his face in Prokesch’s hands:

“You do not respect her, do you?”

And Prokesch replied:

“She was what she could be. The woman your father deserved for a wife did not exist. But he chose her, and she is your mother…”

Reichstadt was now weeping, and a long silence followed. [Aubry pg 207]

And that was when he seriously began to think about escaping.

While the two began to consider exactly what they could do, Franz decided that he had had quite enough of the chaperonage of Count Dietrichstein, his head tutor. This was the man who whipped him when he was five, who thrashed him when he was ten, who drilled him for countless hours on his German and his Italian translations and all the minutiae of court etiquette. He claimed to be utterly devoted to the young prince. Maybe he was, in his own weird way. But Franz was spreading his wings (or at least attempting to— even when he was 20, his imperial grandpa was still prone to treating him like a child, forcing him to dine with him in austerity if his own personal dinner parties became, in Francis’s opinion, too extravagant). In addition to the sensible and devoted Prokesch, Franz had befriended a few other young men, rakes and dandies all, like Neipperg’s eldest son and the young Esterhazy. Franz was gorgeous, brooding, romantic, and with perfect manners, and the women were obsessed with him (a Polish nun who had never met him but only saw him from a distance once swore undying love, even writing letters to this effect).

There was one woman that Franz danced with at a masquerade ball, a certain Naudine Karolyi, black-haired, handsome and bold, and not only did they manage to dodge Metternich’s spies, but they exchanged a lot of letters. This was 1831, and he was 20. But Dietrichstein soon found out about the correspondence.

At any rate, he strode into the Duke’s room, began rummaging through his desk, and finding a drawer locked, commanded him to open it. Reichstadt did not dare refuse— he obeyed, and his governor saw before him a pile of letters from Esterhazy. He opened a few, ran through them, and turned around livid with anger:

“What?” he cried. “You have a love affair?”

“Yes,” replied the prince coolly. “You can see with whom.”

“Do you write to her directly?”

“No, sir.”

“Then through an intermediary? Someone I know?”

He was besides himself with rage and almost shouting. Other persons had just entered the room and stood looking on in surprise at the strange scene. Reichstadt begged the Count to calm himself.

“Come downstairs with me,” he whispered. “You shall have all the letters afterwards, I promise you.”

The Count mastered his anger and went down with him to the Emperor. On the return, the Duke scrupulously handed him the entire correspondence, and it was forthwith consigned to the flames. [Aubry, pg 212]

But this didn’t stop Dietrichstein from trying to intercept Franz’s personal letters. At one point he saw that Esterhazy called him “the old woman,” and Dietrichstein was “extremely hurt.” He tried everything he could to break up the friendship from that day on, but didn’t succeed, as Franz could be extremely stubborn and loyal to a fault.

The affair with Naudine didn’t go anywhere, but there were others— there was even a reputed bastard daughter who later called herself the Comtesse de la Pommiere— but no matter what happened, his heart belonged to Sophie.

* * *

I’m cutting this off here, because LONG POST IS LONG, but more angst and drama will be coming with the next post!

Part One

Part Two

Part Three

#napoleon II#sophie of bavaria#franz duke of reichstadt#l'aiglon#eaglet#octave aubry#marie louise#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#count dietrichstein#metternich#austria#habsburgs#prokesch#king of rome#this poor kid#fucking habsburgs jesus christ

70 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could you recommend books about Napoleon that focus on him as a person? There are so many about his military campaigns.

The struggle is real. Napoleon, of course, is primarily known for his campaigns, Napoleonic warfare and all the politics that go with that. If you’re wanting to get behind all that, it can be difficult. I’ve studied Napoleon for 25 plus years and I was never into the military side of his history. So with my experiences behind me, here’s what I suggest.

1. The Memoirs.

Memoirs are always a good place to start, if you can track them down. Yes, some are faulty, some aren’t accurate, but that doesn’t make them total garbage either. It’s just important to do some research if you can on the writer, know their bias and judge accordingly. Of course, this should be done with the memoirs written today, both auto and not. Memoirs are always going to contain biases and points of views of their writers and their agendas. Welcome to History!

You can break down your memoirs into sections. There are the military memoirs (de Segur, Caulaincourt etc). There will be moments of what I will term “candid life” but be prepared to wade through a lot of military (de Segur was aide-de-camp to Napoleon and wrote about the Russian Campaign) and statesmanship (Caulaincourt was Ambassador to Russia among other things and wrote extensively on Russia as well as the whole political scene after Russia).

There is the court memoirs. These can be a bit more candid but still can have biases of course. Duchess d’Abrantes (Junot) wrote a great set of memoirs that unfortunately are more than likely not all true but make entertaining reading. Claire de Remusat (lady in waiting to Josephine) wrote a set of memoirs but there is some belief that Talleyrand influenced her perhaps and her view of Napoleon isn’t that great. Napoleon’s secretaries wrote memoirs (Bourrienne, Meneval, Fain). Bourrienne is suspect because he was fired from Napoleon’s cabinet due to money issues and he may have an ax to grind. However, he is also one of the few who knew Napoleon as a “kid” due to their years in military school together. Meneval is considered a pretty solid source for the most part and Fain’s memoirs don’t get the attention as much as the other two, but having read them, they’re decent. There will also be political and military matters here of course but not as constant as the pure military memoirs. Constant (Napoleon’s valet) wrote memoirs along with Roustam and St. Denis (bodyguard/valet). There is some question on those and some (like in Roustam’s case) who become apologists for why they left when they left and how it’s really not their fault. Same goes for the mistress memoirs or accounts that are out there. But again, this goes back to the problem with any set of memoirs past or present.

There are the family memoirs…namely Lucien Bonaparte and Hortense de Beauharnais. Lucien, who happens to be my very favorite Bonaparte outside of Napoleon, of course had a very volatile relationship with Napoleon, keep that in mind. Hortense, who happened to be married to my least liked Bonaparte, had a legacy and reputation to protect as well as that of her brother, mother and children.

Last set we’ll call the St. Helena memoirs. I have four sets of St. Helena memoirs (O’Meara, Bertrand, Gourgaud, Marchand). Bertrand is very dry, if you like reading status reports, Bertrand is your guy. He doesn’t put a lot of emotion one way or another into his views, so that may give them a bit more accuracy. O’Meara was an English/Scottish doctor and Gourgaud is the dramatic, over the top, want-to-be best friend of Napoleon. Marchand (Napoleon’s last valet) writes a great memoir that are trusted for the most part. Antommachi is suspect for various reasons in his memoirs.

I am only listing a few here, off the top of my head, but the short version of this would be, memoirs are still your best go-to source (and where most biographies get their content). Just remember that when you read them, you are getting agendas and personalities, just as you do in real life.

2. Biographies

There’s scores of these of course. It’s an old one but I feel pretty good biography on Napoleon is “Napoleon” by Emil Ludwig. Vincent Cronin’s biography is also good. I wouldn’t recommend Alan Schom’s biography as it tends to be a bit titled in the anti-Napoleon line. Some historian’s obviously take a stance on where they see Napoleon and find information that confirms their stance, which is fine. They’re presenting an argument, these are pretty easy to spot. And of course, for every historian that wants to paint Napoleon an ogre, there is one who wants to paint him a saint. Those are as easy to see and obviously, like memoirs, need to be taken into consideration. Biographies can be either a mixture of personality and poli-sci or can favor one over the other.

3.Misc.

These books are probably my favorite. Try to find books that aren’t 100% biography but break down into sections of a life or a personality. If you want to see Napoleon outside of a military camp, sometimes you have to skip the Napoleon biographies and jump into the biographies of the family. Felix Markham and Theo Aronson (author of “The Golden Bees”) both wrote biographies on the Bonapartes as a family. There are biographies written on the various siblings (all of them in fact) that will show more personal sides to Napoleon as son and brother and not so much as commander-in-chief. R. F. Delderfield wrote a book called “Napoleon in Love” which concentrates only on Napoleon’s love life and there have been several books written by various authors (Octave Aubry for example wrote a book titled “Private Life of Napoleon”). Scores have been written about Josephine, and even if you don’t have a primary interest in her or her life, the books dedicated to her are a good place to find Napoleon’s personality more. And there is a ton of books written on the marriages (more on Josephine as wife probably) that are good places to find the more personal side to Napoleon. (Theo Aronson “Josephine and Napoleon; A Love Story.��� Frances Mossiker “Napoleon and Josephine; An Improbable Marriage.” Evangeline Bruce “Napoleon and Josephine; A Biography of a Marriage”, to name but a few). Be prepared for agendas there too, on who was the better spouse, who manipulated who, who was ultimately to blame for what. Check out the biographies done on the mistresses, the step-children, the children etc. as all places to find more personal history versus political history.

St. Helena also gives you the memoirs of Betsy Balcombe (there are several versions out there. A popular one is “St. Helena Story” by Dame Mabel Brookes who was a descendant of Balcombe’s). There are two books that show a more human side to Napoleon, one called “The Black Room at Longwood” by Jean Paul Kauffmann and the other is “The Emperor’s Last Island” but Julia Blackburn. Both of which I would recommend.

There are also books where authors have given Napoleon the main voice, one being “Napoleon on Napoleon”. But like memoirs, remember Napoleon himself had an agenda and a bias.

And lastly, there are some books that have focused purely on Napoleon as a personality. “Napoleon Against Himself” by Avner Falk is a biography written purely from a psychological point of view. I have the book “The Riddle of Napoleon” by Raoul Brice that I found an interesting read that is also written on a personality/psychology point of view.

These are but a small few. I didn’t even touch the “historical fiction” that authors have written that are based on their researches of source materials.

This may have turned out to be a more detailed account than what you were looking for. But I shortened as much as I could! If you like, and are willing to wait a week or so, I can generate a list of the books I have (but it’ll be a bit of time as my collection is rather big) that I found to be good. Of course, you’ll have to keep in mind that I am also giving only an opinion and that I will also be biased.

After you have read enough, you will be able to pick out the common themes and threads and find some truth.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been reading Octave Aubry's biography of Napoleon II and while I'm only half-way through, it already is better than Castelot's biography, mainly because Reichstadt is actually the main subject of the entire book. Castelot spent a crazy amount of time on the fall of the First Empire and Napoleon I on his book (almost half of it?? and it's not even a very long book??), Aubry only dedicates about 60 pages to this. Aubry also cites things, so that's another point for him. And while Aubry is critical about Marie Louise he is not weird about who was she sleeping with, so I appreciate that.

#the only con is that the book doesn't seem to have a bibliography?? but that might just be the english edition that's on the archive#napoleon ii duke of reichstadt

15 notes

·

View notes