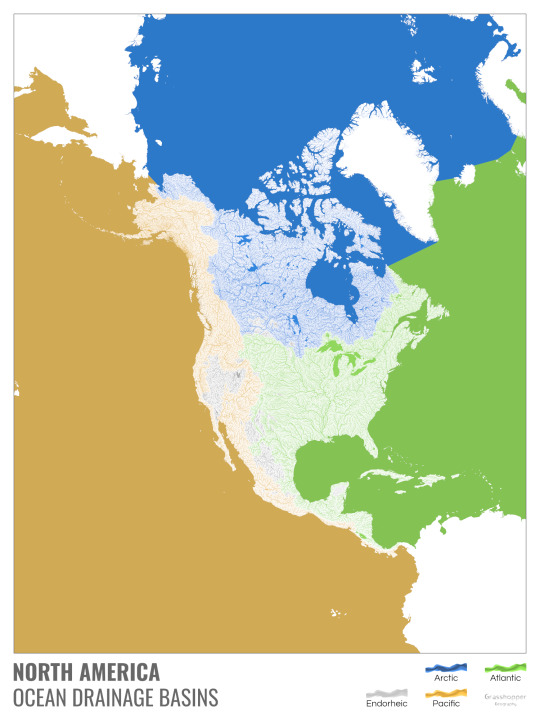

#ocean drainage basins

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

This is still so neat

Hey All,

I've been away for some time, as we've been working really hard on something quite exciting:

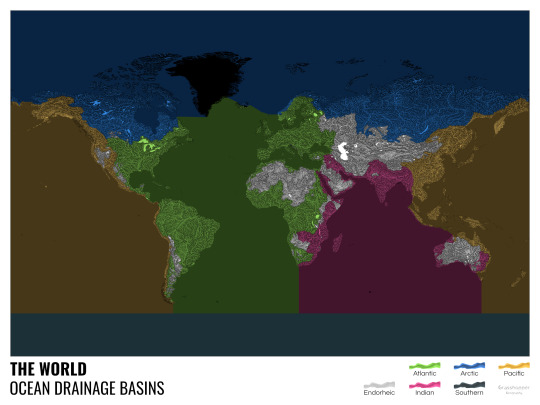

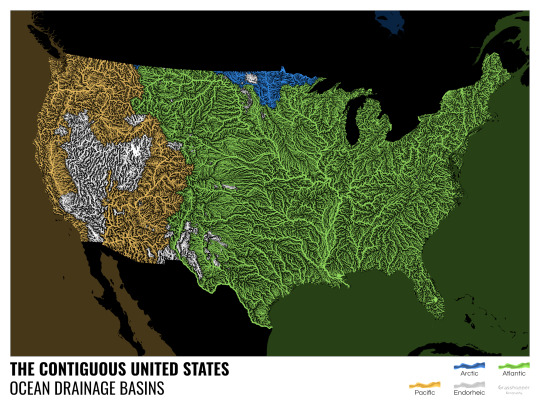

let me present to you the world's first ever global ocean drainage basin map that shows all permanent and temporary water flows on the planet.

This is quite big news, as far as I know this has never been done before. There are hundreds of hours of work in it (with the data + manual work as well) and it's quite a relief that they are all finished now.

But what is an ocean drainage basin map, I hear most of you asking? A couple of years ago I tried to find a map that shows which ocean does each of the world's rivers end up in. I was a bit surprised to see there is no map like that, so I just decided I'll make it myself - as usual :) Well, after realizing all the technical difficulties, I wasn't so surprised any more that it didn't exist. So yeah, it was quite a challenge but I am very happy with the result.

In addition to the global map I've created a set of 43 maps for different countries, states and continents, four versions for each: maps with white and black background, and a version for both with coloured oceans (aka polygons). Here's the global map with polygons:

I know from experience that maps can be great conversation starters, and I aim to make maps that are visually striking and can effectively deliver a message. With these ocean drainage basin maps the most important part was to make them easily understandable, so after you have seen one, the others all become effortless to interpret as well. Let me know how I did, I really appreciate any and all kinds of feedback.

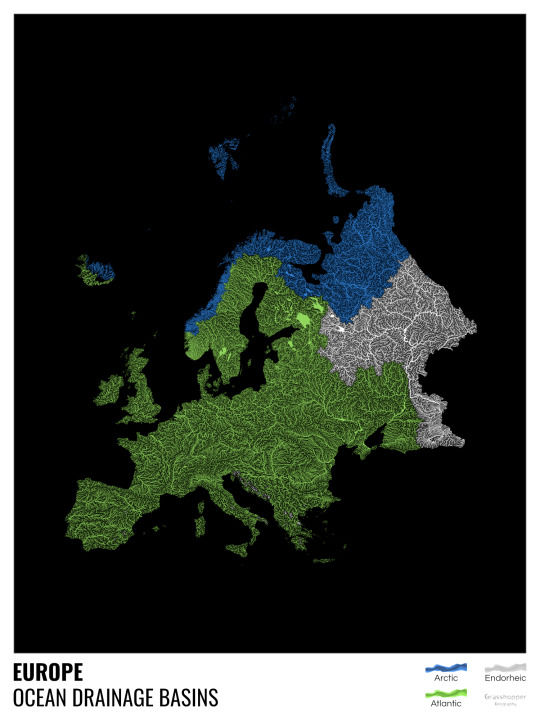

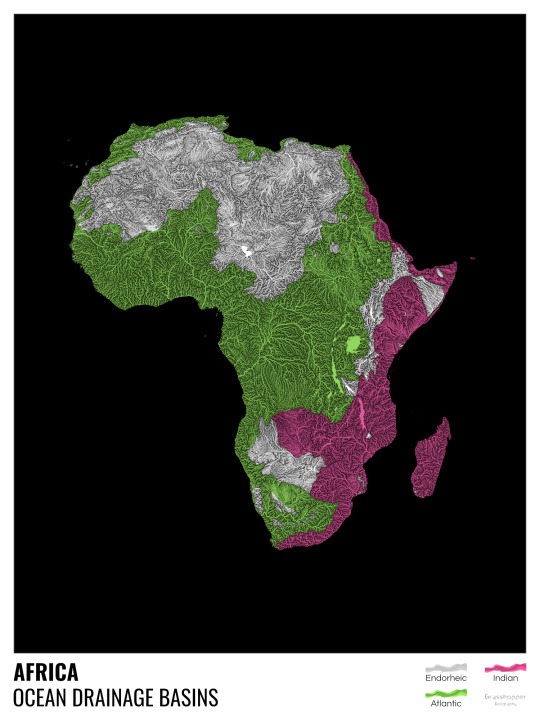

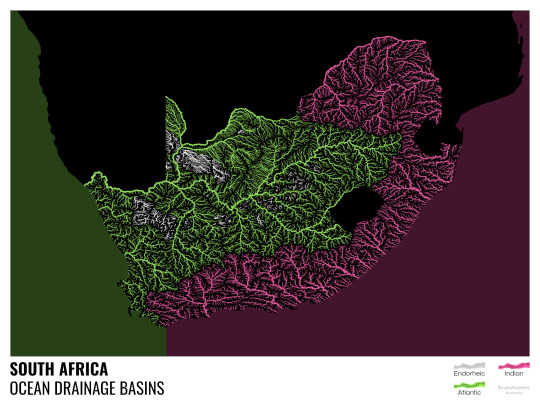

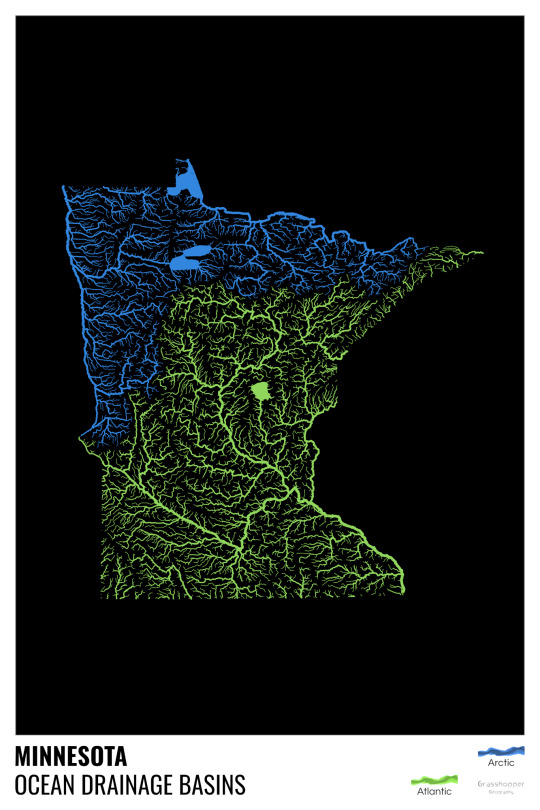

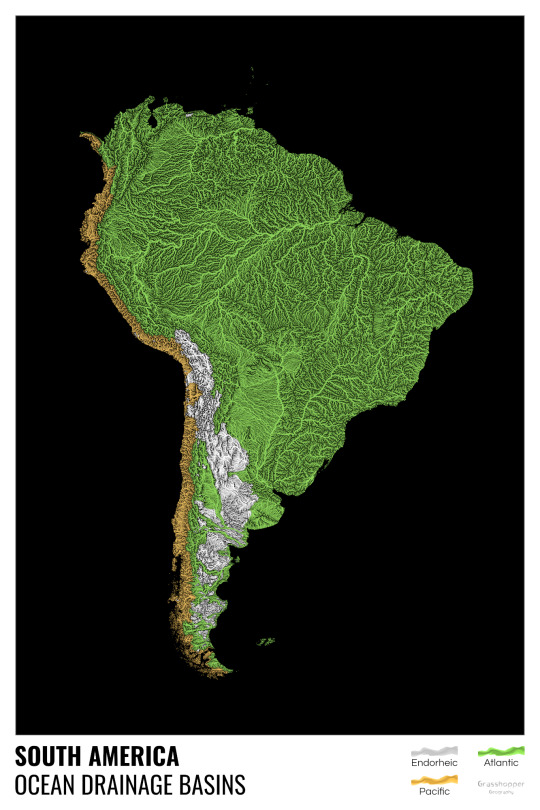

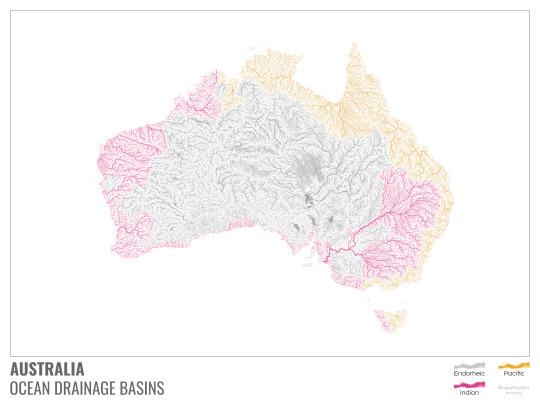

Here are a few more from the set, I hope you too learn something new from them. I certainly did, and I am a geographer.

The greatest surprise with Europe is that its biggest river is all grey, as the Volga flows into the Caspian sea, therefore its basin counts as endorheic.

An endorheic basin is one which never reaches the ocean, mostly because it dries out in desert areas or ends up in lakes with no outflow. The biggest endorheic basin is the Caspian’s, but the area of the Great Basin in the US is also a good example of endorheic basins.

I love how the green of the Atlantic Ocean tangles together in the middle.

No, the dividing line is not at Cape Town, unfortunately.

I know these two colours weren’t the best choice for colourblind people and I sincerely apologize for that. I’ve been planning to make colourblind-friendly versions of my maps for ages now – still not sure when I get there, but I want you to know that it’s just moved up on my todo-list. A lot further up.

Minnesota is quite crazy with all that blue, right? Some other US states that are equally mind-blowing: North Dakota, New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming. You can check them all out here.

Yes, most of the Peruvian waters drain into the Atlantic Ocean. Here are the maps of Peru, if you want to take a closer look.

Asia is amazingly colourful with lots of endorheic basins in the middle areas: deserts, the Himalayas and the Caspian sea are to blame. Also note how the Indonesian islands of Java and Sumatra are divided.

I mentioned earlier that I also made white versions of all maps. Here’s Australia with its vast deserts. If you're wondering about the weird lines in the middle: that’s the Simpson desert with its famous parallel sand dunes.

North America with white background and colourful oceans looks pretty neat, I think.

Finally, I made the drainage basin maps of the individual oceans: The Atlantic, the Arctic, the Indian and the Pacific. The Arctic is my favourite one.

I really hope you like my new maps, and that they will become as popular as my river basin maps. Those have already helped dozens of environmental NGOs to illustrate their important messages all around the world. It would be nice if these maps too could find their purpose.

#maps reimagined#geography#cartography#maps#rivers of the world#ocean drainage basins#ocean maps#river maps

17K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ocean drainage basin map of the United States

by u/Fejetlenfej

281 notes

·

View notes

Text

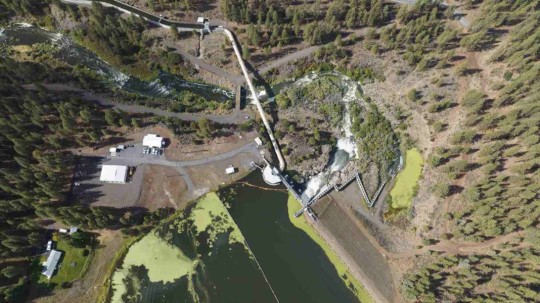

"For years, California was slated to undertake the world’s largest dam removal project in order to free the Klamath River to flow as it had done for thousands of years.

Now, as the project nears completion, imagery is percolating out of Klamath showing the waterway’s dramatic transformation, and they are breathtaking to behold.

Pictured: Klamath River flows freely, after Copco-2 dam was removed in California.

Incredibly, the project has been nearly completed on schedule and under budget, and recently concluded with the removal of two dams, Iron Gate and Copco 1. Small “cofferdams” which helped divert water for the main dams’ construction, still need to be removed.

The river, along which salmon and trout had migrated and bred for centuries, can flow freely between Lake Ewauna in Klamath Falls, Oregon, to the Pacific Ocean for the first time since the dams were constructed between 1903 and 1962.

“This is a monumental achievement—not just for the Klamath River but for our entire state, nation, and planet,” Governor Gavin Newsom said in a statement. “By taking down these outdated dams, we are giving salmon and other species a chance to thrive once again, while also restoring an essential lifeline for tribal communities who have long depended on the health of the river.”

“We had a really incredible moment to share with tribes as we watched the final cofferdams be broken,” Ren Brownell, Klamath River Renewal Corp. public information officer, told SFGATE. “So we’ve officially returned the river to its historic channel at all the dam sites. But the work continues.”

Pictured: Iron Gate Dam, before and after.

“The dams that have divided the basin are now gone and the river is free,” Frankie Myers, vice chairman of the Yurok Tribe, said in a tribal news release from late August. “Our sacred duty to our children, our ancestors, and for ourselves, is to take care of the river, and today’s events represent a fulfillment of that obligation.”

The Yurok Tribe has lived along the Klamath River forever, and it was they who led the decades-long campaign to dismantle the dams.

At first the water was turbid, brown, murky, and filled with dead algae—discharges from riverside sediment deposits and reservoir drainage. However, Brownell said the water quality will improve over a short time span as the river normalizes.

“I think in September, we may have some Chinook salmon and steelhead moseying upstream and checking things out for the first time in over 60 years,” said Bob Pagliuco, a marine habitat resource specialist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in July.

Pictured: JC Boyle Dam, before and after.

“Based on what I’ve seen and what I know these fish can do, I think they will start occupying these habitats immediately. There won’t be any great numbers at first, but within several generations—10 to 15 years—new populations will be established.”

Ironically, a news release from the NOAA states that the simplification of the Klamath River by way of the dams actually made it harder for salmon and steelhead to survive and adapt to climate change.

“When you simplify the habitat as we did with the dams, salmon can’t express the full range of their life-history diversity,” said NOAA Research Fisheries Biologist Tommy Williams.

“The Klamath watershed is very prone to disturbance. The environment throughout the historical range of Pacific salmon and steelhead is very dynamic. We have fires, floods, earthquakes, you name it. These fish not only deal with it well, it’s required for their survival by allowing the expression of the full range of their diversity. It challenges them. Through this, they develop this capacity to deal with environmental changes.”

-via Good News Network, October 9, 2024

#california#oregon#klamath river#dam#dam removal#yurok#first nations#indigenous activism#rivers#wildlife#biodiversity#salmon#rewilding#nature photography#ecosystems#good news#hope

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Mackenzie River, NWT

The Mackenzie River (French: Fleuve (de) Mackenzie; Slavey: Deh-Cho [tèh tʃʰò], literally big river; Inuvialuktun: Kuukpak [kuːkpɑk], literally great river) is a river in the Canadian boreal forest. It forms, along with the Slave, Peace, and Finlay, the longest river system in Canada, and includes the second largest drainage basin of any North American river after the Mississippi.

The Mackenzie River flows through a vast, thinly populated region of forest and tundra entirely within the Northwest Territories in Canada, although its many tributaries reach into five other Canadian provinces and territories. The river's main stem is 1,738 kilometres (1,080 mi) long, flowing north-northwest from Great Slave Lake into the Arctic Ocean, where it forms a large delta at its mouth. Its extensive watershed drains about 20 percent of Canada. It is the largest river flowing into the Arctic from North America, and including its tributaries has a total length of 4,241 kilometres (2,635 mi), making it the thirteenth longest river system in the world.

The ultimate source of the Mackenzie River is Thutade Lake, in the Northern Interior of British Columbia. The Mackenzie valley is believed to have been the path taken by prehistoric peoples during the initial human migration from Asia to North America over 10,000 years ago, despite sparse evidence.

The Inuvialuit, Gwich'in and other Indigenous peoples lived along the river for thousands of years. The river provided the major route into Canada's northern interior for early European explorers.

Economic development remains limited along the river. During the 19th century, fur trading became a lucrative business, but this was affected by harsh weather conditions. The discovery of oil at Norman Wells in the 1920s began a period of industrialization in the Mackenzie valley. Metallic minerals have been found along the eastern and southern edges of the basin; these include uranium, gold, lead, and zinc. Agriculture remains prevalent along the south, particularly in the Peace River area. Various tributaries and headwaters of the river have been developed for hydroelectricity production, flood control and irrigation.

Source: Wikipedia

The Deh Cho Bridge is a 1.1 km-long (0.68 mi) cable-stayed bridge across a 1.6 km (0.99 mi) span of the Mackenzie River on the Yellowknife Highway (Highway 3) near Fort Providence, Northwest Territories. Construction began in 2008 and was expected to be completed in 2010 but faced delays due to technical and financial difficulties. The bridge officially opened to traffic on November 30, 2012. The bridge replaced the MV Merv Hardie, the ferry in operation at the time of opening, and ice bridge combination used for river crossing.

Deh Cho (lit. "Big River") is the Slavey language name for the Mackenzie River.

Source: Wikipedia

#Mackenzie River Access Point#Mackenzie River#Deh Cho Bridge by JR Spronken and Associates Ltd#engineering#Northwest Territories#nature#travel#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#landscape#Canada#summer 2024#river bank#the North#Fort Providence#South Slave Region#flora#meadow#forest#woods

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Geomorphology is the study of the form of the earth. Coastal geomorphologists study the way that the coastal zone, one of the most dynamic and changeable parts of the earth, evolves, including its profile, plan-form, and the architecture of foreshore, backshore, and nearshore rock and sediment bodies. To understand these it is necessary to examine wave processes and current action, but it may also involve drainage basins that feed to the coast, and the shallow continental shelves which modify oceanographic processes before they impinge upon the shore. Morphodynamics, study of the mutual co-adjustment of form and process, leads to development of conceptual, physical, mathematical, and simulation models, which may help explain the changes that are experienced on the coast.

C. Woodroffe, Geomorphology, in Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences, 2001

#quote#geology#geomorphology#nature#science#Colin David Woodroffe#Colin Woodroffe#coastal science#morphodynamics

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

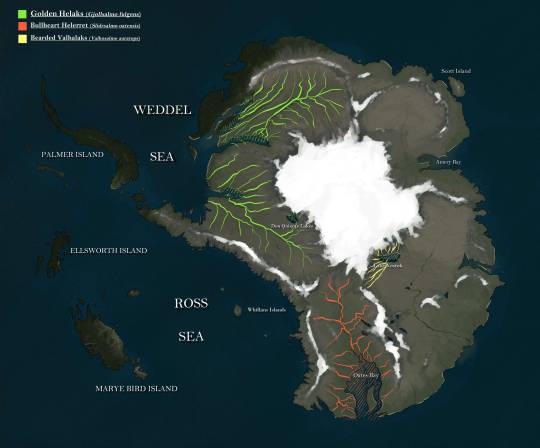

Salmonids of Artechocene Antarctica:

While thawing, the glaciers of Antarctica created an abundance of meltwater streams that now feed countless kilometres of freshwater ecosystems. At first nothing more than insect larvae and some crustaceans called these new environments home, but eventually fish entered the equation and quickly dominated.

One group of these fish were salmonids coming from South American coasts, descendants of invasive species such as the brown trout. They weren't the first, but they were much better at filling a lot of niches than the native Nothotenioids, which lacked hemoglobin and swim bladders.

And so they almost outcompeted these to extinction, and diversified into several genera classified roughly in three distinct groups: Helaks, Helerrets, and Valhallaks.

Most of the Helaks species are amongst the largest predators of the continent, and the Golden Helaks (Gjollsalmo fulgens) is the largest of them all, measuring up to 2 meters (7ft) long and more than 100kg (250lb) in weight. They're apex predators, using their size to block scape routes for prey fish of any size and swallowing them whole, preventing them from scaping thanks to its huge backwards facing teeth. They're also known to eat crustaceans and even birds that venture too deep into the water. They live in every waterway across Antarctica, with the adults being confined to the deeper canals and lakes.

Helerrets are the most common salmonids that can be found in the rivers, lakes and wetlands of the continent. These medium sized predators mainly feed on the abundance of mollusks and other hard shelled invertebrates, as well as smaller vertebrates occasionally. This diet is enabled by their strong jaws, combined with blunt teeth that can crack open the shells of most freshwater invertebrates in their habitats. They're also the only Antarctic salmonids that retain the anadromous habits of its ancestors, living in freshwater but migrating to coastal waters to reproduce and release their young into the rich waters of the Southern Ocean.

The Bullheart Helerret (Slidrsalmo oatensis) in particular is native to the drainage basins that flow into Oates bay, where members of this species comes to spawn.

Valhallaks are a group of salmonids with remarkable sexual dimorphism compared to their close relatives. They are typically found in shallow rivers all across the continent, where they feed on invertebrates and vegetation.

Although not as common as Helerrets, they are abundant, specially in alpine streams and lakes during the end of the summer, where they come to spawn, away from predators so their eggs are protected by ice during the winter.

The Bearded Valhallaks (Valholsalmo auratops) specifically is endemic to the Vostok river drainage basin, which originates in Vostok Lake where they reproduce.

Range of the species featured:

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Southern Ocean

In 2000, the Southern Ocean is the newest ocean recognized by the International Hydrographic Organization.

It borders Antarctica in its entirety.

In terms of size, it’s the fourth-largest at 20,327,000 square kilometers. It extends out to 60 degrees South latitude.

It’s an extreme environment and is the least understood of the 5 oceans. This is because it is unexplored, far from populated areas, and has a severe climate. Despite the Southern Ocean being unexplored, about 80% of all oceans in the world are unexplored. There’s still a lot of work to do for ocean exploration.

Includes: Amundsen Sea, Bellingshausen Sea, part of the Drake Passage, Ross Sea, a small part of the Scotia Sea, Weddell Sea, and other tributary water bodies

Area

Total Area: 21.96 million sq km

Area - Comparative: Slightly more than twice the size of the US

Coastline: 17,968 km

Climate: Sea temperatures vary from about 10 degrees Celsius to -2 degrees Celsius; cyclonic storms travel eastward around the continent and frequently are intense because of the temperature contrast between ice and open ocean; the ocean area from about latitude 40 south to the Antarctic Circle has the strongest average winds found anywhere on Earth; in winter the ocean freezes outward to 65 degrees south latitude in the Pacific sector and 55 degrees south latitude in the Atlantic sector, lowering surface temperatures well below 0 degrees Celsius; at some coastal points intense persistent drainage winds from the interior keep the shoreline ice-free throughout the winter

Ocean Volume: 71.8 million cu km

Percent of World Ocean Total Volume: 5.4%

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Bathymetry

Continental Shelf: A rather flat area of the sea floor adjacent to the coast that gradually slopes down from the shore to water depths of about 200 m (660 ft). Dimensions can vary: they may be narrow or nearly nonexistent in some places or extend for hundreds of miles in others. The waters along the continental shelf are usually productive in both plant and animal life, both from sunlight and nutrients from ocean upwelling and terrestrial runoff. Compared to the continental shelf found in other oceans, in Antarctica the continental shelf is narrower and much deeper. In addition, the continental shelf has been deeply scoured by glacial action.

Astrid Ridge

Belgrano Bank

Gunnerus Ridge

Hayes Bank

Iselin Bank

Continental Slope: Where the ocean bottom drops off more rapidly until it meets the deep-sea floor (abyssal plain) at about 3,200 m (10,500 ft) water depth. The deep waters of the continental slope are characterized by cold temperatures, low light conditions, and very high pressures. Sunlight does not penetrate to these depths, having been absorbed or reflected in the water above. The continental slope can be indented by submarine canyons, often associated with the outflow of major rivers. In the case of Antarctica, the continental slope has been scoured by glacial action cutting troughs and canyons down the slope. Another feature of the continental slope are alluvial fans or cones of sediments carried downstream to the ocean by major rivers and deposited down the slope.

Southern Ocean

Amery Basin

Filchner Trough

Hillary Canyon

Pobeda Canyon

Abyssal Plains: At depths of over 3,000 m (10,000 ft) and covering 70% of the ocean floor, are the largest habitat on earth. Sunlight does not penetrate to the sea floor, making these deep, dark ecosystems less productive than those along the continental shelf. Despite their name, these “plains” are not uniformly flat; they are interrupted by features like hills, valleys, and seamounts.

Amundsen (Abyssal) Plain

Enderby (Abyssal) Plain

South Indian/Australian-Antarctic Basin

Southeast Pacific/Bellinghausen Basin

Weddell (Abyssal) Plain

Mid-Ocean Ridge: Rising up from the abyssal plain, is an underwater mountain range, over 64,000 km (40,000 mi) long, rising to an average depth of 2,400 m (8,000 ft). Mid-ocean ridges form at divergent plate boundaries where two tectonic plates are moving apart and new crust is created by magma pushing up from the mantle. Tracing their way around the global ocean, this system of underwater volcanoes forms the longest mountain range on Earth. Fracture Zones are linear transform faults that develop perpendicular to the line of the mid-ocean ridge which can offset the ridge line and divide it into segments.

Pacific-Antarctic Ridge

Undersea Terrain Features: The Abyssal Plain is commonly interrupted by a variety of commonly named undersea terrain features including seamounts, guyots, ridges, and plateaus. Seamounts are submarine mountains at least 1,000 m (3,300 ft) high formed from individual volcanoes on the ocean floor. They are distinct from the plate-boundary volcanic system of the mid-ocean ridges, because seamounts tend to be circular or conical. A circular collapse caldera is often centered at the summit, evidence of a magma chamber within the volcano. Flat topped seamounts are known as guyots. Long chains of seamounts are often fed by "hot spots" in the deep mantle. These hot spots are associated with stationary plumes of molten rock rising from deep within the Earth's mantle. These hot spot plumes melt through the overlying tectonic plate as it moves and supplies magma to the active volcanic island at the end of the chain of volcanic islands and seamounts. An undersea ridge is an elongated elevation of varying complexity and size, generally having steep sides. An undersea plateau is a large, relatively flat elevation that is higher than the surrounding relief with one or more relatively steep sides. Although submerged, these features can reach close to sea level.

Akopov Seamounts

De Gerlache Seamounts

Endurance Ridge

Marie Byrd Seamount

Maud Rise

Scott Seamounts

Ocean Trenches: The deepest parts of the ocean floor and are created by the process of subduction. Trenches form along convergent boundaries where tectonic plates are moving toward each other, and one plate sinks (is subducted) under another. The location where the sinking of a plate occurs is called a subduction zone. Subduction can occur when oceanic crust collides with and sinks under (subducts) continental crust resulting in volcanic, seismic, and mountain-building processes. Subduction can also occur in the convergence of two oceanic plates where one will sink under the other and in the process create a deep ocean trench. Subduction processes in oceanic-oceanic plate convergence also result in the formation of volcanoes. Over millions of years, the erupted lava and volcanic debris pile up on the ocean floor until a submarine volcano rises above sea level to form a volcanic island. Such volcanoes are typically strung out in chains called island arcs. As the name implies, volcanic island arcs, which closely parallel the trenches, are generally curved.

South Sandwich Trench; the deepest location in the Southern Ocean

Atolls: Due to the extremely cold water there are no atolls in the Southern Ocean

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Highest Point: Sea Level

Lowest Point: Southern end of the South Sandwich Trench -7,434 m unnamed deep

Mean Depth: -3,270 m

Ocean Zones: Composed of water and in a fluid state, the ocean is delimited differently than the solid continents. The ocean is divided into three zones based on depth and light level. Although some sea creatures depend on light to live, others can do without it. Sunlight entering the water may travel about 1,000 m into the oceans under the right conditions, but there is rarely any significant light beyond 200 m.

The upper 200 m (656 ft) of the ocean is called the euphotic, or "sunlight," zone. This zone contains the vast majority of commercial fisheries and is home to many protected marine mammals and sea turtles. Only a small amount of light penetrates beyond this depth.

The zone between 200 m (656 ft) and 1,000 m (3,280 ft) is usually referred to as the "twilight" zone, but is officially the dysphotic zone. In this zone, the intensity of light rapidly dissipates as depth increases. Such a minuscule amount of light penetrates beyond a depth of 200 m that photosynthesis is no longer possible.

The aphotic, or "midnight," zone exists in depths below 1,000 m (3,280 ft). Sunlight does not penetrate to these depths and the zone is bathed in darkness.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Natural Resources: Probable large oil and gas fields on the continental margin; manganese nodules, possible placer deposits, sand and gravel, fresh water as icebergs; squid, whales, and seals - none exploited; krill, fish

Natural Hazards: Huge icebergs with drafts up to several hundred meters; smaller bergs and iceberg fragments; sea ice (generally 0.5 to 1 m thick) with sometimes dynamic short-term variations and with large annual and interannual variations; deep continental shelf floored by glacial deposits varying widely over short distances; high winds and large waves much of the year; ship icing, especially May-October; most of region is remote from sources of search and rescue

Geography - Note: The major chokepoint is the Drake Passage between South America and Antarctica; the Polar Front (Antarctic Convergence) is the best natural definition of the northern extent of the Southern Ocean; it is a distinct region at the middle of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current that separates the cold polar surface waters to the south from the warmer waters to the north; the Front and the Current extend entirely around Antarctica, reaching south of 60 degrees south near New Zealand and near 48 degrees south in the far South Atlantic coinciding with the path of the maximum westerly winds

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Enviornment

Enviornment - Current Issues: Changes to the ocean's physical, chemical, and biological systems have taken place because of climate change, ocean acidification, and commercial exploitation

Enviornment - International Agreements: The Southern Ocean is subject to all international agreements regarding the world's oceans; in addition, it is subject to these agreements specific to the Antarctic region: International Whaling Commission (prohibits commercial whaling south of 40 degrees south [south of 60 degrees south between 50 degrees and 130 degrees west]); Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Seals (limits sealing); Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (regulates fishing) note: mineral exploitation except for scientific research is banned by the Environmental Protocol to the Antarctic Treaty; additionally, many nations (including the US) prohibit mineral resource exploration and exploitation south of the fluctuating Polar Front (Antarctic Convergence), which is in the middle of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current and serves as the dividing line between the cold polar surface waters to the south and the warmer waters to the north

Climate: Sea temperatures vary from about 10 degrees Celsius to -2 degrees Celsius; cyclonic storms travel eastward around the continent and frequently are intense because of the temperature contrast between ice and open ocean; the ocean area from about latitude 40 south to the Antarctic Circle has the strongest average winds found anywhere on Earth; in winter the ocean freezes outward to 65 degrees south latitude in the Pacific sector and 55 degrees south latitude in the Atlantic sector, lowering surface temperatures well below 0 degrees Celsius; at some coastal points intense persistent drainage winds from the interior keep the shoreline ice-free throughout the winter

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Ports and Terminals

Major Seaport(s): McMurdo, Palmer, and offshore anchorages in Antarctica

Note: Few ports or harbors exist on the southern side of the Southern Ocean; ice conditions limit use of most to short periods in midsummer; even then some cannot be entered without icebreaker escort; most Antarctic ports are operated by government research stations and, except in an emergency, are not open to commercial or private vessels

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been in a creative frenzy these past few days and I went from just having a vague idea of just a regional map for my dnd campaign, to suddenly having a rough topological world map almost finished. It's in the cahill butterfly projection because it's easier to ideate in and I cannot be asked to account for much distortion so I just decided to make the world fit easily onto the projection. I'm not gonna be too anal about the tectonic realism but my goal is for someone with like a bachelor's in geology to be able to take a look at this and think it at least feels truthy (and you can see some of my sketching of what the tectonic activity is)

next step: atmospheric circulation

next next step: oceanic circulation

next next next step: climate zoning

next next next next step: drainage basins, rivers, and hydrology

next next next next next step: major eco-zones

next next next next next next step: major cultural zoning and fitting in the other cultures I've thought of but haven't mapped yet onto the map

I desperately need sleep

#mine#personal#I also spent way too long getting a decent implementation of this projection working in blender#so now I'm able to export the map and actually view it on a globe when I want to make sure everything fits together right#so I have krita open on one monitor and blender open on the other#players don't look if you do somehow manage to see this no you didn't#there's certain parts of the map I don't love but overall I'm pretty happy with it#the layout was hard though#I got way less ocean than the real earth but I choose to be okay with that#it's still like... more than half ocean I think#so that should be fine#worldbuilding

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I made a world where I did that. I drew plates, flipped a coin for oceanic vs continental, then drew drift directions that seemed sensible. This let me determine where the mountain ranges, volcanoes, and oceans were. From there you can use other physical geography basics like rain shadow and latitude to figure out what the climate and vegetation of an area should look like. After that I decided some basic drainage basins, which helped determine where rivers, and therefore settlements would be. Only after that did I start populating the standard fantasy races.

reminder to worldbuilders: don't get caught up in things that aren't important to the story you're writing, like plot and characters! instead, try to focus on what readers actually care about: detailed plate tectonics

137K notes

·

View notes

Text

Understanding Stormwater Plans: Key Elements and Importance

Stormwater management is a crucial aspect of property and urban planning, ensuring that rainwater runoff is appropriately managed to prevent flooding, water pollution, and damage to infrastructure. One essential tool in this process is a stormwater plan, which outlines how stormwater will be managed on a site. Stormwater plans are essential in safeguarding the environment and maintaining the structural integrity of buildings and roads, whether for residential, commercial, or industrial properties.

What is a Stormwater Plan?

A stormwater plan is a detailed blueprint that describes how stormwater will be handled during and after a rainstorm, ensuring that it doesn’t negatively impact the surrounding area. This plan typically covers how water will be captured, treated, and diverted away from the site, following specific regulations and standards set by local councils or governing bodies.

Key Elements of a Stormwater Plan

Site AnalysisA stormwater plan begins with analysing the site’s geography and hydrology. Inspectors and engineers assess soil type, slope, existing drainage systems, and historical rainfall data. This analysis helps determine how water flows across the site and where it needs to be directed to avoid pooling or flooding.

Collection and Storage SystemsStormwater plans typically outline methods for collecting rainwater runoff. This can include installing gutters, drains, or swales (shallow ditches) to capture water as it flows off surfaces like roofs, roads, or parking lots. Additionally, the plan may include provisions for water storage in retention basins or underground tanks, allowing for controlled release over time.

Treatment SystemsTreating stormwater is essential to a stormwater plan to ensure that it doesn’t carry pollutants into local water sources. Filtration systems, oil-water separators, and vegetated swales are commonly used to remove contaminants before the water is released into natural waterways or storm drains.

Water Flow DiversionDirecting stormwater away from buildings, foundations, and roads is vital to prevent damage. A stormwater plan will include strategies for diverting water flow through the use of trenches, channels, or pipes that safely direct runoff to designated areas like retention ponds or municipal stormwater systems.

Maintenance and MonitoringA successful stormwater management plan includes provisions for regular maintenance. This includes cleaning gutters, checking pipes for blockages, and inspecting detention systems to ensure everything functions properly. Monitoring water quality and drainage performance is also essential for long-term success.

Why Are Stormwater Plans Important?

Flood PreventionProper stormwater management prevents localised flooding, which can damage property and infrastructure and disrupt daily activities. A stormwater plan ensures that runoff is managed to avoid overloading drainage systems and reduce the risk of flooding.

Environmental ProtectionBy treating stormwater before it is released into local water bodies, a stormwater plan helps protect ecosystems from pollution. This is particularly important in urban areas, where runoff from roads and buildings can carry pollutants like oil, chemicals, and debris into rivers, lakes, and oceans.

Compliance with RegulationsMany local authorities require stormwater management plans as part of development approval processes. These plans must adhere to regulations to protect the environment and public safety. Ensuring that a stormwater plan meets these requirements is critical for obtaining permits and avoiding fines.

Enhancing Property ValueProperties with well-designed stormwater systems can see increased value, as effective water management reduces the potential for future water-related damage. In addition, homes and businesses in areas prone to flooding can benefit from stormwater plans that ensure long-term protection.

Conclusion

A well-designed stormwater plan is essential for managing water runoff and preventing potential environmental and structural issues. Whether building a new property or improving an existing one, having a comprehensive stormwater plan ensures your property remains safe, compliant, and sustainable. For tailored advice and professional support, contact a stormwater management expert today and take the first step toward effective water management.

0 notes

Photo

Ocean drainage basin map of the world

by u/Fejetlenfej

189 notes

·

View notes

Text

Freshwater fishes of the Madagascan continent are not the most popular among aquarium fishes. But one species of rainbowfish from eastern Madagascar, Bedotia madagascariensis, is common enough and traded as the Madagascan rainbowfish. This name can apply to more than one species of Bedotia sp. which are also known as the zonas. These are not very large fishes, growing to around 8 and 1/2 centimeters or nearly 3 and 1/2 inches.

B. madagascariensis are known from rivers and lakes between the Ivoloina and the Manambolo rivers. Following their translocation to marshes near Antananarivo, the species has become established in the Betsiboka basin. This species inhabits clear, shaded streams, preferring slow-flowing sections.

Shade from an overhanging forest canopy, is demonstrably an important habitat requirement for these fish in the wild, and they depend on arthropods from the canopy overhead as their natural food. Without shading from above they are also more vulnerable to predatory birds that hunt fish. Adult B. madagascariensis inhabit deeper water than do the younger fishes.

B. madagascariensis is often confused with a more southern and upland species, B. geayi, that is only known from the Mananjary drainage in the south of Madagascar. There it can be found in small streams, between 300 and 600 meters above sea level. Most of the rainbowfish traded as B. geayi are more accurately B. madagascariensis, and there are some anatomical differences between these two related species.

Rainbowfish are a freshwater subclade of silversides, distributed in the nowadays well separated regions of Madagascar and Australasia. This is a difficult distribution to explain, other than to note that the Madagascan and Australasian rainbowfishes are only distantly related, though together comprise an ancient clade. Their kinship among the other silversides is revealed by similarities of behaviors, and physical sexual dimorphism, among other characteristics.

It is thus assumed that ancient, ancestral rainbowfishes had lived on both continents, prior to the breakup of Gondwana into island fragments. If this is correct, then rainbowfishes related to Bedotia must once have lived in India, of which Madagascar was once a part. Freshwater organisms cannot cross oceans, so like land animals, their distributions and relationships predict continental drift.

B. madagascariensis are a rainbowfish that can usually be kept without problems, and can be recommended for beginners. Regarding the chemical parameters of aquarium water, and the matter of food, these pretty fishes are rather undemanding. These are schooling fishes, and they need to be maintained together in some numbers. Yet the presence of too many males in the group will create conflicts and distress.

Though Bedotia sp. are not very large fishes they are active, and their aquarium must allow them good, unobstructed swimming space, but also opportunity to retreat. Without which these fish are less likely to 'color up'. Dense planting in part of the aquarium allows this, and gives the females somewhere to scatter their eggs. Bedotia sp. have mouths large enough for small fish to be eaten. Thus it is advised that their tankmates be relatively large in proportion to the rainbowfishes.

Madagascar rainbowfishes are easy to feed on defrosted food of suitable nature, and they will also consume proprietary flake preparations. For these fishes, flakes are quite apt because they float at the water surface. Despite claims circulated in the popular aquarium literature, fish from the eastern flowing drainages of Madagascar, are in fact inhabitants of soft water with a low pH. They are not native to hard or strongly alkaline waters.

On Madagascar this species is recorded even in waters with a pH slightly below 5. But people actually are keeping them in water that is more neutral and even a bit alkaline, such as a pH of 7.5. It is sometimes repeated that Madagascan rainbowfishes like a temperature of 20 to 24 degrees centigrade.

B. madagascariensis are lowland fish found only at altitudes below 30 meters, and in the wild, the water temperature they experience can reportedly range from 23 to 32 degrees, within the period of one month. More recently, information based on zookeeping has indicated and standardized their care, at a temperature of 24 to 25 degrees centigrade.

It is definitely worth pointing out, that despite misinformation that Madagascan rainbowfishes are brackish water fishes, neither B. madagascariensis nor B. geayi are native to estuaries. These species are in fact unable to tolerate salinities above 5 ppt, which is a low salinity, and as truly freshwater fishes, they do not need any salt added to their water at all.

#Bedotia madagascariensis#Madagascan rainbowfish#zona#rainbowfishes#schooling fishes#community fishes#misunderstood fish#madagascan fishes

0 notes

Text

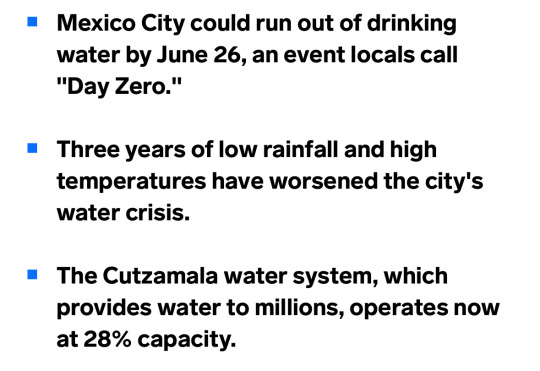

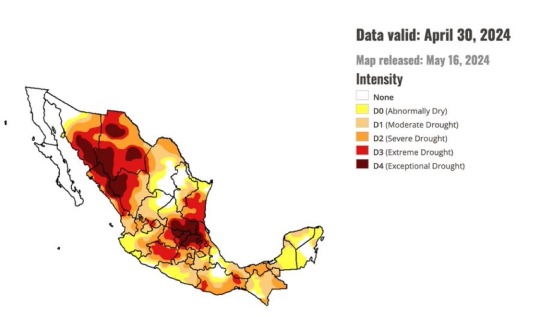

I don't want to blame anyone for, but Mexico's water situation is totally preventable.

Mexico city was built on an area where there were abundant lakes and wetlands, and these were drained to build the city. This act was incredibly ecologically destructive and the region's ecology has never really recovered.

One of the things that is lost when wetlands are drained is that the whole hydrology shifts from retaining water to percolate into the groundwater, to running it off where it runs off into the ocean faster.

While this is nice for people upstream in times of heavy rain, it is terrible in a long list of ways. One of the major downsides is an increase in drought.

With wetland draining and channelization, water tables are more dependent on short-term rain events, and thus tend to fall more (and aquifers can eventually get depleted and streams drying up) during times of drought. So a drought that would have historically made water levels fall somewhat, might lead to entire streams, lakes, and rivers drying up, following channelization.

The removal of wetlands also hugely reduces evapotranspiration in a region, which can reduce rainfall in areas downwind. Mexico City is surrounded by mountains, and there was originally an equilibrium in which a certain portion of the water stayed local: it would evaporate, then orographic lift would dump the water as rain on surrounding mountains, and a large portion of that would flow back right into the basin of wetlands. With the drainage of the lake and wetlands, that water now leaves the region. So rainfall has decreased, which compounds the problem.

Worsening these problems are widespread deforestation and desertification due to unsustainable agriculture and ranching practices, which is a problem in Mexico far broader than just the Mexico City region. And these practices have the same effect of worsening drought, decreasing rainfall, and speeding runoff when it does rain.

I'm not saying Mexico City wouldn't face a problem even if they had done everything perfectly, but Mexico has definitely created a huge portion of the problems they are suffering from now. It's a lot like the Dust Bowl in the US.

We need to stop messing with nature and stop destroying ecosystems. We need ecosystems especially rich ones like forests and wetlands. We need to protect them and learn how to live with and sustain ourselves from these wild ecosystems instead of clearing them and replacing them with anthropogenic habitats that are worse at water cycling.

Source

Source

28K notes

·

View notes

Text

Jasper National Park, AB (No. 6)

The park was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1984, together with the other national and provincial parks that form the Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks, for the mountain landscapes containing mountain peaks, glaciers, lakes, waterfalls, canyons, and limestone caves as well as fossils found here.

Most of the park's area forms the headwaters of the Athabasca River, which originates in the parks extreme southernmost point at an unnamed lake unofficially known as Columbia Lake due to it being fed by one of the Columbia Icefield's many outlet glaciers. Despite its misleading name, the well-known Athabasca Glacier is actually the source of the Sunwapta River, a tributary of the Athabasca, not the main river itself. Other major tributaries of the Athabasca River that drain large areas of the park include the Maligne River, the Snake Indian River, Rocky River and the Miette River. The northernmost area of the park is drained separately by the Smoky River. Both the Smoky and Athabasca Rivers form part of the Mackenzie River drainage, the largest river system in Canada, which itself is part of the Arctic Ocean basin. The southeast section of the park is drained by the Brazeau River which is part of the Saskatchewan/Nelson River system which ultimately flows into Hudson Bay.

The park is coextensive with the province of Alberta's Improvement District No. 12.

Source: Wikipedia

#Talbot Lake#Alberta#Rocky Mountains#Northern Rockies#Alberta's Rockies#travel#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#landscape#summer 2023#Canada#woods#forest#reflection#flora#nature#countryside#fir#pine#Jasper National Park#UNESCO World Heritage Site#Yellowhead Highway#wildlife#animal#fauna

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Climate of New Hampshire

See Weather Forecast for New Hampshire today: https://weatherusa.app/new-hampshire

See more: https://edition.cnn.com/2024/05/03/weather/brazil-rain-floods-intl/index.html?iid=cnn_buildContentRecirc_end_recirc

New Hampshire, located in the northeastern United States, experiences a varied climate influenced by its proximity to the Atlantic Ocean and its terrain. Summers are generally warm and humid, while winters are cold and snowy. The state's climate is categorized as humid continental, with distinct four seasons.

During the summer months, which typically span from June to August, temperatures in New Hampshire can range from mild to hot. Daytime highs often reach into the 80s Fahrenheit (around 27 to 32°C), occasionally exceeding 90°F (32°C) during heatwaves. Humidity levels can be relatively high, especially in July and August, but the presence of lakes and rivers provides opportunities for outdoor recreation and relief from the heat.

Fall, from September to November, is a spectacular season in New Hampshire, known for its vibrant foliage as the leaves change color. Temperatures gradually decrease, with daytime highs ranging from the upper 50s to the 70s Fahrenheit (around 15 to 25°C). Crisp, cool evenings contribute to the beauty of the autumn landscape, making it a popular time for leaf-peeping and outdoor activities.

See more: https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-03269

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-03266

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-03261

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-03260

Winter in New Hampshire, lasting from December to February, is characterized by cold temperatures and ample snowfall, particularly in the mountainous regions. Daytime highs typically range from the 20s to the 30s Fahrenheit (around -6 to -1°C), while nighttime lows can plummet below freezing, often into the single digits Fahrenheit (around -15 to -10°C). Snowstorms are common, and snow accumulations contribute to skiing, snowboarding, and other winter sports enjoyed in the state's numerous ski resorts.

Spring, from March to May, brings a gradual thaw and the return of warmer temperatures to New Hampshire. Daytime highs slowly climb from the 40s to the 60s Fahrenheit (around 4 to 20°C), signaling the start of the growing season. However, spring also brings the possibility of rain showers and occasional snowstorms, particularly in March and early April.

Overall, New Hampshire's climate offers residents and visitors the opportunity to enjoy a wide range of outdoor activities throughout the year, from skiing and snowmobiling in the winter to hiking, fishing, and leaf-peeping in the summer and fall.

New Hampshire boasts five primary drainage basins, each contributing to its diverse waterways and landscapes. The largest basin belongs to the Merrimack River, located in the central region of the state. Following closely is the Connecticut River basin, situated along the western border. Additional waters flow into the Saco, Piscataqua, and Androscoggin rivers, collectively referred to as the coastal rivers, alongside various smaller streams.

See more: https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-03257

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-03251

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-03246

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-03241

While these riverbanks harbor rich deposits of deep soil conducive to agriculture, the state's overall soil composition tends to be rocky, thin, and challenging for farming. Nonetheless, the rivers serve as vital arteries, shaping New Hampshire's geography and providing essential resources for its communities.

New Hampshire exhibits a highly varied climate, with distinct seasonal characteristics. Winters can be bitterly cold, with temperatures plunging below 0 °F (-18 °C) for extended periods. Summers, on the other hand, tend to be relatively cool, contributing to an average annual temperature of about 44 °F (7 °C).

Annual precipitation in New Hampshire averages around 42 inches (1,070 mm), distributed fairly evenly across the four seasons. Snowfall is a notable feature, with an average of about 50 inches (1,270 mm) along the coast and double that amount, approximately 100 inches (2,540 mm), in the northern and western regions of the state.

The most extreme climatic conditions can be found atop Mount Washington, home to a renowned weather observatory. On April 12, 1934, this summit recorded a world-record wind speed of 231 miles (372 km) per hour, highlighting the remarkable weather phenomena experienced in this region.

See more: https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-03101

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-03105

0 notes