#neotheropoda

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A couple of Tachiraptor admirabilis looking for a snack in Venezuela during the Early Jurassic

#dinosaur#illustration#paleoart#paleontology#paleoillustration#paleoblr#palaeoblr#art#palaeontology#jurassic world#jurassic period#dinosaur art#dinosauria#dinosaurs#dinovember#theropod#saurischian#neotheropoda#palaeoart#paleoartist#venezuela#prehistoric#animals#earth history

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Really proud of this Dilophosaurus I did! Especially considering how quickly I did it and without reference.

#my art#digital art#palaeoart#paleoart#paleo art#palaeo art#paleontology#dilophosaurus#art#dinosaur#dinosauria#theropod#theropoda#Jurassic#neotheropoda

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

Birds are class Aves.

Sure, under Linnaean taxonomy. But, well,

A) Linnaeus was a eugenecist so his scientific opinions are suspect and his morality is awful

B) he didn't know about evolution

C) he didn't know about prehistoric life

so his classification system? Sucks ass. It doesn't work anymore. It no longer reflects the diversity of life.

Instead, scientists - almost across the board, now - use Clades, or evolutionary relationships. No rankings, no hierarchies, just clades. It allows us to properly place prehistoric life, it removes our reliance on traits (which are almost always arbitrary) in classifying organisms, and allows us to communicate the history of life just by talking about their relationships.

So, for your own edification, here's the full classification of birds as we currently know it, from biggest to smallest:

Biota/Earth-Based Life

Archaeans

Proteoarchaeota

Asgardians (Eukaryomorphans)

Eukaryota (note: Proteobacteria were added to an asgardian Eukaryote to form mitochondria)

Amorphea

Obazoa

Opisthokonts

Holozoa

Filozoa

Choanozoa

Metazoa (Animals)

ParaHoxozoa (Hox genes show up)

Planulozoa

Bilateria (all bilateran animals)

Nephrozoa

Deuterostomia (Deuterostomes)

Chordata (Chordates)

Olfactores

Vertebrata (Vertebrates)

Gnathostomata (Jawed Vertebrates)

Eugnathostomata

Osteichthyes (Bony Vertebrates)

Sarcopterygii (Lobe-Finned Fish)

Rhipidistia

Tetrapodomorpha

Eotetrapodiformes

Elpistostegalia

Stegocephalia

Tetrapoda (Tetrapods)

Reptiliomorpha

Amniota (animals that lay amniotic eggs, or evolved from ones that did)

Sauropsida/Reptilia (reptiles sensu lato)

Eureptilia

Diapsida

Neodiapsida

Sauria (reptiles sensu stricto)

Archelosauria

Archosauromorpha

Crocopoda

Archosauriformes

Eucrocopoda

Crurotarsi

Archosauria

Avemetatarsalia (Bird-line Archosaurs, birds sensu lato)

Ornithodira (Appearance of feathers, warm bloodedness)

Dinosauromorpha

Dinosauriformes

Dracohors

Dinosauria (fully upright posture; All Dinosaurs)

Saurischia (bird like bones & lungs)

Eusaurischia

Theropoda (permanently bipedal group)

Neotheropoda

Averostra

Tetanurae

Orionides

Avetheropoda

Coelurosauria

Tyrannoraptora

Maniraptoromorpha

Neocoelurosauria

Maniraptoriformes (feathered wings on arms)

Maniraptora

Pennaraptora

Paraves (fully sized winges, probable flighted ancestor)

Avialae

Avebrevicauda

Pygostylia (bird tails)

Ornithothoraces

Euornithes (wing configuration like modern birds)

Ornithuromorpha

Ornithurae

Neornithes (modern birds, with fully modern bird beaks)

idk if this was a gotcha, trying to be helpful, or genuine confusion, but here you go.

all of this, ftr, is on wikipedia, and you could have looked it up yourself.

679 notes

·

View notes

Text

i have a new account at @neotheropoda but idk if im gonna use it yet We will see...

#dib noise#im leaving it until these weekened to see#though i will probably change it back to lightnersdream when the timeframe is up#i will update if i do of course..

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cockatrice (Artwork by Yuujinner)

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class/Clade: Reptilia (Sauropsida)

Clade: Diapsida

Clade: Archosauria

Clade: Dinosauria

Clade: Saurischia

Clade: Eusaurischia

Clade: Theropoda

Clade: Neotheropoda

Clade: Averostra

Clade: Tetanurae

Clade: Avetheropoda

Clade: Coelurosaria

Clade: Maniraptoriformes

Clade: Maniraptora

Clade: Pennaraptora

Clade: Oviraptorosauria

Clade: Edentoraptora

Superfamily: Caenagnathoidea

Family: Caenagnathidae?

Subfamily: incertae sedis

Genus: Ornithosaurus

Species: O. necrophilus (“death-loving bird lizard”)

Ancestral species: possibly Microvenator celer

Temporal range: late Pleistocene to recent (87,000 kya - present)

Information:

A ravenous scavenger, the cockatrice is by no means at the top of its food chain, though its uniquely offensive, musky odor, ear-splitting vocalizations, and proclivity for traveling in large groups called flocks make it a creature which few predators wish to tolerate. Add onto this its territorial aggression, and you have what may be Archaeonesia’s most detested scavenger. Cockatrices use their superb sense of smell to detect carrion from several tens of miles away, primarily feeding on the carcasses of various reptilian and mammalian megafauna, sometimes flocking around fresh kills made by larger predators and using their sheer number to overwhelm the carnivore into relinquishing its kill. Though it usually eats carrion, it is also classified as an opportunistic feeder, readily going after small vertebrates. Found primarily in the Arava Desert and the surrounding grasslands in the western half of the Isle of Perils, this medium-sized oviraptorosaur is known all throughout the Isle of Perils, including its central mountain range, making it one of the few non-avian dinosaurs to live in that region. It is also one of the few non-avian dinosaurs to actively seek out human settlements, particularly to feed on discarded scraps of food. Actively seeking out human settlements, it is known to scavenge from trash heaps and refuse bins, which make it a local pest in some areas. Entire flocks of these animals, as many as 40 individuals sometimes, may swarm landfills. Similarly, these creatures will use their sheer number of overwhelm larger carnivores into relinquishing kills before greedily tearing into their spoils. A pecking order can be observed amongst these animals, typically in which the largest male gets first pickings on the corpse. When feeding on carrion, as gruesome as it may be, they will typically eat away at the orifices first before hollowing out the cadaver. Due to its exceptionally strong stomach acids being able to kill most bacteria, it can eat carrion which most other scavengers would otherwise find too putrid or dangerous to consume. Attracted to shiny objects for the purposes of adorning their nests with them, they have been known to steal jewelry, though those which live farther from human settlements may instead use quartz and other naturally occurring crystals to adorn their nests. These animals are exceptional jumpers, being able to clear fences nearly 12 feet all and jump nearly 25 feet in a single bound. Exceptionally territorial in nature, groups may mark trees and rocks with a pair of scent glands behind their ears, which produce the foul musky odor typically associated with the animal. As these animals are quite social, their ability to recognize patterns (and more specifically faint color patterns and facial differences) allow them to differentiate between one another with remarkable ease. They can also recognize human faces with exceptional accuracy. Grooming behavior is well-documented, and like primates, it plays an important role in establishing social relations. Primarily diurnal, these animals rely on scent and eyesight to find food, and typically, a few individuals will venture away from the nesting grounds at a given time to locate food before they’ll go back and alert the others of its location, utilizing what is sometimes described as an elaborate“dance”, consisting of many different vocalizations, as well as head and body movements, to communicate location, much in the same way honeybees do. As the many environments it lives in are teeming with predators, a few individuals will take shifts throughout the night to watch the nesting grounds while the others sleep. A pouch at the base of the neck, commonly called a crop, allows the animal to store food before digesting it, though it serves a dual function of allowing it to transport food back to the nest to feed its offspring.

Though a given flock of cockatrices may not necessarily consist of entirely closely related individuals, it is more common than not for a flock to consist of a set of parents or grandparents and several generations of offspring. During the beginning of the dry season, around early December, the males’ colors will become substantially more flashy and eye-catching, his wattle flushing a bright maroon and violet color and the undersides of his wings flushing a pink hue, and although related species are known to engage in mock fights as part of mating displays, this species instead relies on a less violent method of winning approval from the females they wish to court: designing the most colorful display. A male will create a nest and adorn it with the most colorful materials he can found, anything from flowers and fruits to rocks and crystals. However, this is only part of the courtship ritual. While a bright nest may earn some initial interest from female suitors, it is what he does next that determines his success: performing an elaborate dance, sometimes with a shiny rock clutched in his beak, he will angle his head up towards the sky, revealing his brightly-colored wattle and wings. High-stepping in a circle around her, his throat will undulate to make a deep, rattling bellow, beating his wings and jumping up and down to keep her attention. If she accepts, she will join him in this dance and copulation begins. Cockatrices mate for life, and in 1.5 months time, she will lay a clutch of 2-4 blue eggs in the nest, and for the 5 weeks it will take for them to hatch, she will not leave the nest, the male fetching her food and water via his crop. When the young are born, they are, in a rare exception amongst non-avian theropods, altricial, being born nearly featherless and unable to walk for the first few weeks of life. By a month old, they will be able to walk. By a year, they will have reached half their adult size, being large enough to join their parents in the search for food. By 2 years, they will reach adult size, and at around 3.5 years, they will have gained their adult plumage and will reach sexual maturity. Many may choose to stay with their parents’ flock, though some may go off and form flocks with other young cockatrices. If they’re lucky, a cockatrice may expect to live 20-30 years.

Around the size of a cassowary, this species is around 5.6 feet tall, roughly 9-10 feet in length, and weighs around 200 lbs on the heavier side. There is no notable sexual dimorphism between species. The naked head is highly fluorescent, the neck being reddish yellow and the wattle/fleshy growths on its face being yellowish-orange and bluish-purple. The beak is red and the eyes are white. Plumage is white on the body and most of the wings, though near the base of the neck, the tail, and the wing feathers, the plumage starts to turn black, with the wing plumage having many beige spots along their length. Its legs are yellowish-gray.

Long-renowned for its dissonant calls, this species generally communicates with others of its kind with rasps, shrill humming, and a sound variously called “bleating” or “bugling”. Territorial calls consist of loud, deep booms which rumble across the land. However, it may hiss or honk if aggravated or in an attempt to intimidate and size up other scavengers/carnivores, and it has a characteristic shrieking whoop referred to by some as a “dinner bell call” to other cockatrices that food has been located.

Much in the same way that vultures are viewed as unclean and malevolent animals in Western society, so, too, is the cockatrice in Xenogaean society, made dually ironic for the fact that vultures also exist in the region, albeit typically in more montane environments. Long seen as a bad luck omen, stumbling across a dead cockatrice was said to signal impending disaster, particularly famine or drought, and in fact, it was said that if one did stumble across one, or managed to kill one, they were to immediately cremate it and spread its ashes in a river. Nonetheless, it does appear in some heraldic imagery and was venerated amongst some indigenous peoples in the region, particularly to the southeast. It was said the Bronze Age Aravan King, Kuntapurexa, infamous for his brutal conquests across the Isle of Perils, was followed by a horde of cockatrices which reaped the benefits of his conquests, feeding on the corpses of those he and his men killed as they went from village to village pillaging and marauding. The deafening sounds of these animals from afar was therefore used by some villagers as a way to determine how close Kuntapurexa and his men were to their settlement and therefore whether or not to abandon the town. How true this was, however, remains up to speculation, as no surviving historical records seem to confirm if this was a true account or not, with the possibility of it being a tall tale being rather likely. That said, if one can get past the animal’s revolting smell and dietary habits, a tame cockatrice makes for an exceptional companion animal, being exceptional at navigating, tracking, and retrieving items and trinkets, and in times past, some would use these animals to discretely transmit messages across long distances in a similar manner to messenger pigeons. On top of that, its affectionate nature towards those it’s acquainted with makes it decent as a pet as well, minus its food requirements. In fact, while some cities actively try to exterminate or otherwise relocate cockatrices within their walls, others may actively promote breeding programs for the animals in an effort to reduce waste in landfills. Despite being classified as a caenagnathid oviraptorosaurian, this placement is tentative: though its skull anatomy and genetic data would seem to support an inclusion amongst the Caenagnathidae or at least closer to the Caenagnathidae than the Oviraptoridae, the anatomy of its arms (and its wrists in particular) is exceptionally basal, more akin to that of therizinosaurs or ornithomimosaurs than to that of other oviraptorosaurs. Amongst an indigenous group in the Arava Desert region known as the Nge'echets, the cockatrice was seen as an embodiment of the desert itself, almost a god in its own right, far contrary to how their Xenogaean-speaking neighbors viewed the animal. As such, offerings were left out to the animals as a way of asking for safe passage from one oasis to the next as part of their migratory lifestyle. Nonetheless, amongst all native cultures in the region, the consumption of this animal’s meat is considered taboo due to its scavenging lifestyle. In lieu with its scavenging lifestyle, flocks of these animals may follow sick or injured animals for miles, waiting for them to collapse before finishing them off, hence it was long said that spotting a cockatrice behind oneself was a sign that death was on one’s doorstep. In some regions, they are also associated with the Xenogaean death goddess, Yerakiya, seen as either her messengers or even as a form she herself takes in the world of the living. Bones of this animal date back to the late Pleistocene, around 87,000 years ago, and fossil member of the genus are known as far back as the Miocene. A smaller closely-related species found on an offshore island, the basilisk (O. insularis), went extinct in the 18th century due to the introduction of pigs by British colonists. With around 2,000,000 mature adults in the wild, populations appear to be stable but declining in certain areas.

#scifi#fantasy#speculative evolution#novella#scififantasy#speculative biology#speculative fiction#speculative zoology#worldbuilding#creature art#oviraptorosauria#cockatrice#sci fi#scifi worldbuilding#fantasy worldbuilding#fantasy creature#scifi creature#dinosaurs#dinosaur#spec evo

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Fossil Friday!

Who: Cryolophosaurus ellioti

name meaning: "Cold" "Crested" "Lizard" "David Elliot - who originally discovered the skeletal fragments of Cryolophosaurus"

pronunciation: Cry-oh-low-foe-sore-us - ell-ee-ot-eye

What: A crested theropod in the neotheropoda clade, which also includes Dilophosaurus and Dracovenator

When: Early Jurassic, Hanson Formation

Where: Central Transatlantic Mountains in Antarctica

Fun fact!: Cryolophosaurus is one of six dinosaur species discovered on Antarctica!

Why are they cool?: Like all dilophosaurids it possessed some impressive head gear, in C. ellioti this crest is formed from an elongation of the lacrimals (one of the bones in face near the orbits) and nasal bones. The purpose of these crests is still debated and with low sample sizes, difficult to dicern. Some theories include: sexual dimorphism (a difference between males and females) or recognition of species/display function.

Image Credits: (Left: Pablo Pastori Right: M. Cross)

#palaeontology#paleontology#fossil friday#fossils#paleo#palaeoart#paleoart#antarctica#cryolophosaurus#snow#dinosaur#theropod#jurassic#dilophosaurus#crested dinosaurs

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

"Your dinosaur is..."

Cryolophosaurus ellioti

Discovered: Antarctica, 1990/1991

Time Period: Early Jurassic, 186-182 mya

Taxonomy: Theropoda, Neotheropoda

Length: 6-7 meters

Weight: 350-465 kilograms

“It’s really pretty Ava-San. The coloring reminds me of a penguin. I wonder if it acted penguin like at all, no maybe not it looks like it hunts land animals instead of fish.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Cryolophosaurus (/ˌkraɪoʊˌloʊfoʊˈsɔːrəs/ or /kraɪˌɒloʊfoʊˈsɔːrəs/; "CRY-oh-loaf-oh-SAWR-us") adalah sebuah genus dari Theropoda besar yang diketahui hanya dari satu spesies tunggal, Cryolophosaurus ellioti, diketahui dari periode Jura Awal di Antarktika. Panjangnya sekitar 65 meter (213,3 ft) dan beratnya sekitar 465 kilogram (1.025 pon), menjadikannya salah satu theropoda terbesar pada masanya. Individu dari spesies ini bahkan mungkin telah tumbuh lebih besar, karena satu-satunya spesimen yang diketahui mungkin merupakan theropoda yang belum dewasa sepenuhnya. Cryolophosaurus diketahui dari satu tengkorak, satu tulang paha, dan material lainnya, tengkorak dan tulang paha tersebut yang telah menyebabkan klasifikasinya menjadi sangat bervariasi. Tulang pahanya memiliki banyak karakteristik primitif yang mengklasifikasikan Cryolophosaurus sebagai dilophosaurid atau neotheropoda di luar Dilophosauridae dan Averostra, sedangkan karena tengkoraknya memiliki banyak ciri lanjutan, menyebabkan genusnya dikategorikan tetanuran, abelisaurid, ceratosaur, dan bahkan allosaurid. Sejak deskripsi awalnya, konsensusnya adalah bahwa Cryolophosaurus termasuk di antara anggota primitif dari Tetanurae atau kerabat dekat dari kelompok itu.

0 notes

Text

Megapnosaurus

Etymology: Big Dead Lizard

Length: 3 meters ( 3 m )

Height: 80 centimeters ( 80 cm )

Weight: 32 kilograms ( 32 kg )

Diet: Carnivore

Temporal range: Early Jurassic, Mesozoic Era ( 199 million years ago - 188 million years ago )

Place: Africa ( Zimbabwe · South Africa )

Classification: Life, Animalia, Chordata, Vertebrata, Gnathostomata, Tetrapoda, Amniota, Sauropsida, Reptilia, Diapsida, Neodiapsida, Sauria, Archosauromorpha, Archosauriformes, Archosauria, Avemetatarsalia, Ornithodira, Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Coelophysoidea, Coelophysidae, Coelophysinae

0 notes

Photo

Sinosaurus triassicus (Chinese Reptile from Triassic) is a primitive member of the neotheropoda. With newly redesign based on complete skull of new specimen of Sinosaurus triassicus. But when I said “redesign,” I do mean redrawing the old sinosaurus triassicus (formerly known as Dilophosaurus sinensis) from DeviantArt since May 13th, 2013, it’s been 10 years ago. #sinosaurus #sinosaurustriassicus #paleoart #myart #neotheropoda #theropoda #earlyjurassic #dinosauria #dinosaur #sketchbookapp https://www.instagram.com/p/CqO0v3Urqdg/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#sinosaurus#sinosaurustriassicus#paleoart#myart#neotheropoda#theropoda#earlyjurassic#dinosauria#dinosaur#sketchbookapp

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

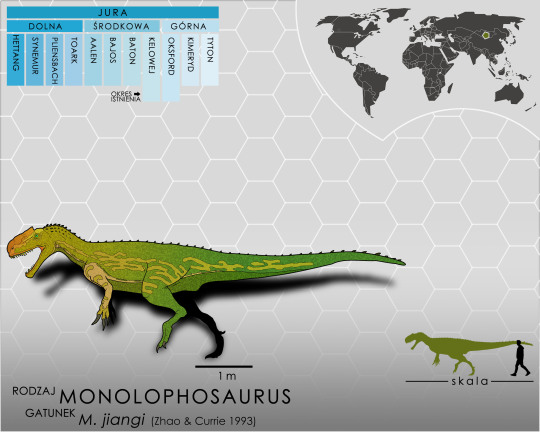

Monolophosaurus jiangi (Zhao & Currie 1993) Klad - Tetanurae

#Monolophosaurusjiangi#Monolophosaurus#Tetanurae#Averostra#Neotheropoda#Theropoda#Jurassic#paleoart#digitalart#doodle#procreateart#restoration#speculation#reconstruction#dinosaurs#monsteranimal#monster#dino#digitaldrawing#dinoart#dinosaur

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

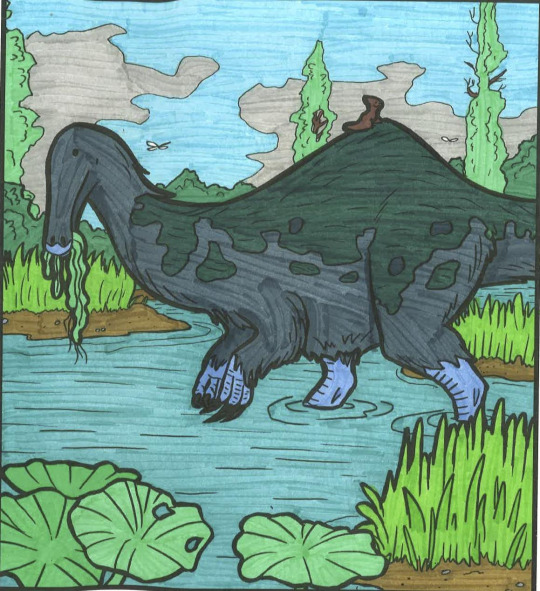

Sinosaurus triassicus wonders if it will have unwelcome dinner guests in China during the Early Jurassic 👀

#dinosaur#illustration#paleoart#paleontology#paleoillustration#paleoblr#palaeoblr#art#palaeontology#dinosauria#jurassic period#jurassic world#jurassic dinosaurs#theropod#neotheropoda#saurischian#paleoartist#palaeoart#dinosaur art#prehistoric#prehistoric planet#natural history#sciart

546 notes

·

View notes

Conversation

daisydice: : Dinosauria, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes Gnotornis is known from part of a polish chicken is looking really pretty skating.

meme-constructor: : Dinosauria, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes Gnotornis is known from Kazakhstan, specifically sometime probably in the US from South American stock . First up, the Easter Egger hens, Reese and Peace :.

daisydice: : Dinosauria, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes Manu is a celtic and germanic given name, from proto-germanic *χrōþi- “fame” and *berχta- “bright”.

meme-constructor: Weren’t they ADORABLE?

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

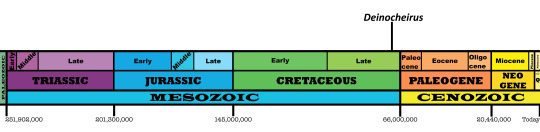

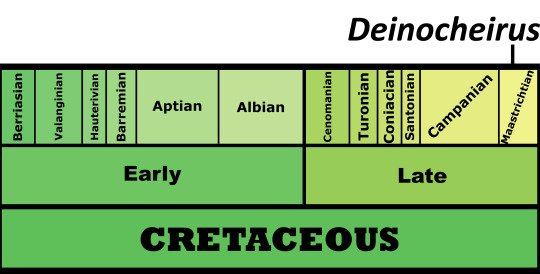

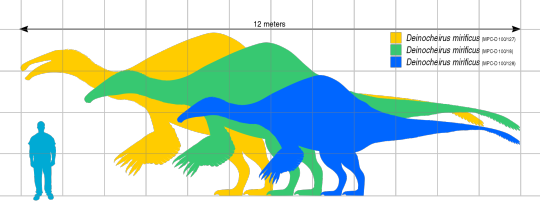

Deinocheirus mirificus

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Horrible Hand

First Described By: Osmólska & Roniewicz, 1970

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Ornithomimosauria, Ornithomimoidea, Deinocheiridae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: 70 million years ago, in the Maastrichtian of the Late Cretaceous

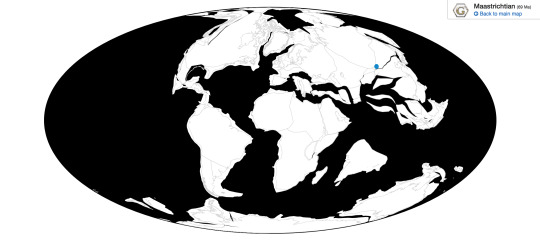

Deinocheirus is known from the Nemegt Formation of Ömnögovi, Mongolia

Physical Description: Deinocheirus is one of the absolute weirdest, fantastical, most surprising discoveries of the 2010s in paleontology, and the answer to a mystery older than most of the readers of this blog. Deinocheirus was originally known from two very long, distinctive arms - arms so long, that they could very easily engulf a person. In fact, many of the photographs of the fossil are of an individual standing in between the hands, in order to give scale to them. But these arms and hands gave very little in the way of information about what Deinocheirus looked like. Eventually, it was determined that Deinocheirus was an Ornithomimosaur - but the scale of the arms indicated it would be a ridiculously huge Ornithomimosaur.

By Slate Weasel, in the Public Domain

And then, luckily, more fossils were found of it. To be sure, it was a ridiculously large Ornithomimosaur - in fact, given the fact that it was an Ornithomimosaur, a group of distinctively feathered dinosaurs, it is almost certainly one of the largest feathered animals known to date - but it was More than that by a large margin. It was probably around 11 meters long, weighing up to 6.4 tonnes. It had some of the largest forelimbs known of any bipedal dinosaur - only rivaled by Therizinosaurs - and the arms in question are 2.4 meters long. Its skull, only one specimen of it having been found, is honestly weirdly duck-shaped. It was low and narrow, like other Ornithomimosaurs, but with a longer snout than its relatives. This snout was wide and shaped like a spatula - similar to the snouts of duck-billed dinosaurs and ducks alike. There weren’t any teeth in the jaws, which ended in a distinctive beak, and it was turned down, to make it look fairly massive and deep. When you get down to it, Deinocheirus had a ridiculously triangular head.

By Nix, CC BY-NC 4.0

As for the rest of the body, Deinocheirus had very long and narrow shoulder blades, connected to very pronounced and triangular shoulders. Weirdly enough, compared to the shoulders, Deinocheirus actually had smaller arms than its close relative Ornithomimus - ie, it had a smaller shoulder to arm ratio than its relatives. It had a U-shaped wishbone, which is fascinating since we don’t have the wishbone of other Ornithomimosaurs. Unlike other Ornithomimosaurs, it didn’t have pinched toe bones, so it wasn’t highly adapted for fast movement; it also had very blunt and broad foot claws like those of large Ornithischian dinosaurs. It may have been a bulky animal, but it was also quite narrow - with very tall, straight ribs. It had an S-curved neck, especially given the shape of the skull, which extended back into the oddly indeed shaped back. The spines on the back of Deinocheirus got progressively and progressively longer, until reaching lengths similar to those found on Spinosaurus - indicating that Deinocheirus had a sail or a hump, much like Spinosaurus did. There were interconnecting ligaments on the spines, strengthening it. That sail then lessened as it went down along the tail, until the tail had a very skinny appearance compared to the rest of the body. It had extremely lightweight air bones, through which the respiratory system ran. This also allowed it to be even more lightly built, which aided it in its large size. Interestingly enough, the tail ended in fused vertebrae, like those in Therizinosaurs, Oviraptors, and Birds - indicating it had a pygostyle!

By Michael B. H., CC BY-SA 3.0

As for feathers, it would have probably been covered in a layer of fluff all over the body. Fancy, pennaceous feathers would have been present on the arms and the end of the tail - in fact, a tail fan would have been attached to that pygostyle and used in display. It may have also had display feathers on the back of the head or even the legs. However, that being said, its large size may indicate a decrease in fluff so that it could stay cool - while it is still most likely that it had distinctive and extensive feathers as in its close relatives, fossil evidence is needed to determine its exact integument situation.

By Charles Nye

Diet: Deinocheirus was, distinctively, a large herbivore - specializing on water plants and other soft greens that could be shoveled up with that spoon beak.

By Meig Dickson & Diane Remic

Behavior: Deinocheirus probably spent a good amount of time foraging at or near the water, gathering up water vegetation with its spatulate bill. It also utilized gastroliths - stones that were swallowed to grind up that wet and mushy vegetation in the stomach. This was important and helpful, since it couldn’t do much grinding without teeth in its mouth. It did have a very long and large tongue, which allowed it to pull up extensive amounts of plant material up from the ground. It would use the blunt and short claws of its hands in order to dig up plants from the water - and to decrease resistance as it sucked them up from the swamps.

By Rebecca Groom

Deinocheirus wasn’t a fast animal - the short and stocky legs meant that it moved slowly through its environment, and used its large size to protect itself against predators instead. It grew extremely rapidly, too, reaching large size before sexual maturity. Sadly, its giant size means that it didn’t have a very large brain compared to its body size - in fact, the ratio in question was more similar to that of sauropods than other theropods. That beings aid, it was similar in shape to birds and troodontids and other birdie theropods, indicating that it still had a decent sense of smell - which is fascinating as it had a good respiratory system as well. As a warm-blooded animal, however, it would have been very active; and as a dinosaur, it probably took care of its young in nests. It is uncertain whether or not it would have lived in social groups, but it certainly wouldn’t have been particularly isolated as an herbivore.

By José Carlos Cortés

Ecosystem: The Nemegt Formation was a wetland, filled with a wide variety of dinosaurs right before the end of the time of non-avian dinosaurs. The area was filled with large river channels, which created extensive shallow lakes, mudflats, and floodplains - like the modern Okavango Delta in Botswana. There were also thick coniferous forests surrounding the ecosystem, allowing for drier areas to be retreated to in addition to the swampy mess that was the bulk of the environment. Here, many plant-eaters specialized in feeding on water plants - in fact, I often joke that the Nemegt is the Land of Ducks. In addition to Deinocheirus, there were two other Ornithomimosaurs - Gallimimus and Anserimimus - both featuring duck-like beaks for feeding on water plants. Other ducks of the region include Saurolophus, which, as a duck-billed dinosaur, was especially adapted for feeding on soft plant material; and Teviornis, an early ACTUAL duck relative with the appropriate bill.

By Fraizer

This place also had other dinosaurs that weren’t ducks, of course. There was the large tyrannosaur, Tarbosaurus, which is known to have directly preyed upon Deinocheirus. There were troodontids too, like Tochisaurus, Zanabazar and Borogovia, which would have preyed upon the eggs and young of Gallimimus. There were a million different Oviraptorosaurs, making this also the ecosystem of the Chickenparrots - Avimimus, Elmisaurus, Conchoraptor, Nemegtomaia, Nomingia, and Rinchenia, were all present and feeding on the drier vegetation of the area. There was also the Hesperornithine Brodavis, one of the few freshwater species of Hesperornithines. There were other herbivores too, of course - Pachycephalosaurs like Homalocephale and Prenocephale, ankylosaurs such as Tarchia and Saichania, the titanosaur Nemegtosaurus, and the Therizinosaur Therizinosaurus - which probably all stuck to drier areas of the ecosystem than Deinocheirus. Tarbosaurus wasn’t the only Tyrannosaur, either - there was the smaller Alioramus which would have been more of a nuisance for baby Deinocheirus than the adults. And for other predators, there was the raptor Adasaurus, which may or may not have been a direct descendant of Velociraptor. As for non-dinosaurs, there was at least one Azdarchid, the small mammal Buginbaatar, and a variety of crocodilians that would have been non-negligible threats to young Deinocheirus. There were also plenty of turtles, which would have been a very noticeable part of the wider ecosystem.

By Scott Reid

Other: Deinocheirus is such a weird Ornithomimosaur, it gave its name to an entire group of them - these guys were slower than the Ornithomimids, and larger, but still had that general Ostrich-mimic shape. Instead of being lean and fast, they were large and slow. The discovery of the specimens of Deinocheirus that allowed us to actually learn what it looked like was a big one - since, prior to that point, Deinocheirus had been one of the most fascinating mysteries of dinosaur science, as all we had were two giant hands! Because of its large size, duck-like appearance, and above all, nightmare fodder in terms of past legend and current appearance, Deinocheirus has been fondly dubbed as Duck Satan for a makeshift common name.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Arbour, V. M., Currie, P. J. and Badamgarav, D. (2014), The ankylosaurid dinosaurs of the Upper Cretaceous Baruungoyot and Nemegt formations of Mongolia. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 172: 631–652.

Barret, P. M. 2005. The diet of Ostrich dinosaurs (Theropoda: Ornithomimosauria). Palaeontology 48 (2): 347 - 358.

Barsbold, R. (1983). "Carnivorous dinosaurs from the Cretaceous of Mongolia [in Russian]." Trudy, Sovmestnaâ Sovetsko−Mongol’skaâ paleontologičeskaâ èkspediciâ, 19: 1–120.

Bell, P.R., Currie, P.J., Lee, Y.N. 2012. Tyrannosaur feeding traces on Deinocheirus (Theropoda: ?Ornithomimosauia) remains from the Nemegt Formation (Late Cretaceous), Mongolia. Cretaceous Research 37: 186 - 190.

Chinzorig, T., Kobayashi, Y., Tsogtbaatar, K., Currie, P.J., Takasaki, R., Tanaka, T., Iijima, M., Barsbold, R. 2017. Ornithomimosaurs from the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia: manus morphological variation and diversity. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 494: 91 - 100.

Claessens, L. P. A., and M. A. Loewen. 2016. A redescription of Ornithomimus velox Marsh, 1890 (Dinosauria, Theropoda). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 36(1):e1034593:1-15

Fanti, F., Bell, P.R., Tighe, M., Milan, L.A., Dinelli, E. 2017. Geochemical fingerprinting as a tool for repatriating poached dinoaur fossils in Mongolia: A case study for the Nemegt Locality, Gobi Desert. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 494: 51 - 64.

Fowler DW, Woodward HN, Freedman EA, Larson PL, Horner JR (2011) Reanalysis of “Raptorex kriegsteini”: A Juvenile Tyrannosaurid Dinosaur from Mongolia. PLoS ONE 6(6): e21376.

Funston, G. F.; Mendonca, S. E.; Currie, P. J.; Barsbold, R. (2017). "Oviraptorosaur anatomy, diversity and ecology in the Nemegt Basin". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.

Gradzinski, R., J. Kazmierczak, J. Lefeld. 1968. Geographical and geological data form the Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions. Palaeontologia Polonica 198: 33 - 82.

Holtz, T.R. 2014. Paleontology: Mystery of the horrible hands solved. Nature 515 (7526): 203 - 205.

Hurum, J. 2001. Lower jaw of Gallimimus bullatus. In Tanke, D. H., K. Carpenter, M. W. Skrepnick. Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 34 - 41.

Jerzykiewicz, T., Russell, D.A. 1991. Late Mesozoic stratigraphy and vertebrates of the Gobi Basin. Cretaceous Reserch 12 (4): 346 - 377.

Kobayashi, Y., Barsbold, R. 2006. Ornithomimids from the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia. Journal of the Paleontological Society of Korea 22 (1): 195 - 207.

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. 1969. Fossils from the Gobi desert. Science Journal 5(1):32-38

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z., R. Barsbold. 1972. Narrative of the Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions 1967-1971. Palaeontologia Polonica 27: 5 - 136.

Kundrat, M., Lee, Y.N. First insights into the bone microstructure of Deinocheirus mirificus. 13th Annual Meeting of the European Association of Vertebrate Paleontologists: 25.

Lauters, P., Lee, Y.N., Barsbold, R., Currie, P.J., Kobayashi, Y., Escuille, F.O., Godefroit, P. 2014. The brain of Deinocheirus mirificus, a gigantic ornithomimosaurian dinosaur from the Cretaceous of Mongolia. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Abstracts of Papers: 166.

Lee, Y.N., Barsbold, R., Currie, P.J., Kobayashi, Y., Lee, H.J. 2013. New specimens of Deinocherus mirificus from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Abstracts of Papers: 161.

Lee, Y.N., Barsbold, R., Currie, P.J., Kobayashi, Y., Lee, H.J., Godefroit, P., Escuillie, F.O., Chinzorig, T. 2014. Resolving the long-standing enigmas of a giant ornithomimosaur Deinocheirus mirificus. Nature 515 (7526): 257 - 260.

Madsen, E. K. 2007. Beak morphology in extant birds with implications on beak morphology in Ornithomimids. Dek Matematisk-Naturvitenskapelige Fakultet - Thesis. 1 - 21.

Makovicky, P.J., Kobayashi, Y., Currie, P.J. 2004. Ornithomimosauria. In: Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., Osmolska, H. eds. The Dinosauria. University of California Press.

McFeeters, B., M. J. Ryan, C. Schroder-Adams and T. M. Cullen. 2016. A new ornithomimid theropod from the Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 36:e1221415:1-20

Middleton, K.M., Gatesy, S.M. 2000. Theropod forelimb design and evolution. Zoologicla Journal of the Linnean Society 128 (2): 160 - 172.

Mikhailov, K. E. 1991. Classification of fossil eggshells of amniotic vertebrates. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 36(2):193-238

Molnar, R.E. 2001. Theropod Paleopathology: a Literature Survey. In: Tanke, D.H., Carpenter, K. eds. Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Indiana University Press.

Newbrey, M. G., Donald B. Brinkman, Dale A. Winkler, Elizabeth A. Freedman, Andrew G. Neuman, Denver W. Fowler and Holly N. Woodward (2013). "Teleost centrum and jaw elements from the Upper Cretaceous Nemegt Formation (Campanian-Maastrichtian) of Mongolia and a re-identification of the fish centrum found with the theropod Raptorex kreigsteini". In Gloria Arratia; Hans-Peter Schultze; Mark V. H. Wilson (eds.). Mesozoic Fishes 5 – Global Diversity and Evolution. Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil. pp. 291–303.

Norell, M. A., P. J. Makovicky, P. J. Currie. 2001. The Beaks of Ostrich Dinosaurs. Nature 412 (6850): 873 - 874.

Norell, M.A.; Makovicky, P.J.; Bever, G.S.; Balanoff, A.M.; Clark, J.M.; Barsbold, R.; Rowe, T. (2009). "A Review of the Mongolian Cretaceous Dinosaur Saurornithoides (Troodontidae: Theropoda)". American Museum Novitates. 3654: 63.

Novacek, M. 1996. Dinosaurs of the Flaming Cliffs. Anchor. Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc. New York, New York.

Osmolska, H., Roniewicz, E. 1970. Deinocheiridae, a new family of theropod dinosaurs. Palaeontologica Polonica 21: 5 - 19.

Paul, G.S. 1988. Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. Simon & Schuster.

Paul, G.S. 2012. The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press.

Roy, B., Ryan, M.J., Currie, P.J., Koppelhus, E.B., Tsogtbaatar, K. 2018. Histological analysis of the gastralia of Deinocheirus mirificus from the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia. 6th Annual Meeting Canadian Society of Vertebate Paleontology.

Rozhdestvensky, A.K. 1970. Giant claws of enigmatic Mesozoic reptiles. Paleontologicheskii Zhurnal 1970 (1): 117 - 125.

Senter, P., Robins, J.H. 2012. Hip heights of the gigantic theropod dinosaurs Deinocheirus mirificus and Therizinosaurus cheloniformis, and implications for museum mounting and paleoeoclogy. Bulletin of the Gunma Museum of Natural History 14: 1 - 10.

Shuvalov, V.F. (2000). "The Cretaceous stratigraphy and palaeobiogeography of Mongolia". In Benton, Michael J.; Shishkin, Mikhail A.; Unwin, D.M.; Kurochkin, E.N. (eds.). The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 256–278.

Takanobu Tsuihiji, Brian Andres, Patrick M. O'connor, Mahito Watabe, Khishigjav Tsogtbaatar & Buuvei Mainbayar (2017) Gigantic pterosaurian remains from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Watabe, M., S. Suzuki, K. Tsogtbaatar, T. Tsubamoto, M. Saneyoshi. 2010. Report of the HMNS-MPC Joint Paleontological Expedition in 2006. Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences Reasearch Bulletin 3:11 - 18.

Watanabe, A., Eugenia Leone Gold, M., Brusatte, S.L., Benson, R.B.J., Choiniere, J., Davidson, A., Norell, M.A., Claessens, L. 2015. Vertebral pneumaticity in the ornithomimosaur Archaeornithomimus (Dinosauria: Theropoda) revealed by computed tomography imaging and reappraisal of axial pneumaticity in ornithomimosuria. PLoS ONE 10 (12): e0145168.

Zelenitsky, D K., F. Therrien, G. M. Erickson, C. L. DeBuhr, Y. Kobayashi, D. A. Eberth, F. Hadfield. 2012. Feathered non-avian dinosaurs from North America provide insight into wing origins. Science 338 (6106): 510 - 514.

#Deinocheirus mirificus#Deinocheirus#Ornithomimosaur#Dinosaur#Duck Satan#Dinosaurs#Feathered Dinosaurs#Feathered Dinosaur#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Mesozoic Monday#Cretaceous#Herbivore#Eurasia#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

What is Tawa (dinosaur)

Tawa hallae is a pretty nifty little theropod from the Late Triassic! For starters, we’ve got a couple fairly complete skeletons of it to work with, along with several bones from other individuals in the same quarry, so it’s anatomy is well known:

(Source, Scott Hartman)

But Tawa is significant though not just because it’s complete, but because it appears to be intermediate in shape and anatomy between earlier diverging predatory dinosaurs like herrerasaurs and Eoraptor and the ‘proper’ theropods like coelophysoids at the base of Neotheropoda (the ‘core’ theropods, if you will).

See, Neotheropoda is a pretty consistent group, all the major clades within it (e.g. coelophysoids, megalosauroids, allosauroids, coelurosaurs) are agreed to belong together and their relationships are considered pretty solid.

Triassic dinosaurs like herrerasaurs, Eoraptor and so on are less stable and have been more prone to jumping between positions at the base of Dinosauria because of how “primitive” they are, for a lack of better word. Eoraptor for instance has hopped around as an early sauropodomorph, theropod and outside those two all together:

(Source, Scott Hartman. Again.)

Tawa has some of the characteristics shared by neotheropods (at least initially), implying that Tawa is a close relative of them, branching off before the common ancestor of neotheropods acquired all of their traits. Other traits however are more like those of the earlier predatory dinosaurs, so it has a weird combination of ‘primitive’, ancestral traits and some of the ‘advanced’, derived traits found in neotheropods.

In that sense, it’s an intermediate between those early predatory dinosaurs and the neotheropods, both in terms of its anatomy and its evolutionary relationships. As much as the term is discouraged, I’m going to describe it as almost a textbook example of a transitional fossil, a species that diverged during the process of the evolution of a new group from an ancestral stock with a series of intermediate traits between the two.

(Source, originally from Sues et al. 2011)

The cladogram above shows herrerasaurs, Eoraptor and Daemonosaurus (misspelled with an ‘i’) and Tawa as successive branches on the line leading to neotheropods.

As is the way of things though, a lot of the early predatory dinosaurs have continued to bounce around. If you’re familiar with The Befrickening that was Ornithoscelida, you’ll know how that analysis found herrerasaurs to be related to the sauropodomorphs, rather than a true theropod, for example. But in each case, Tawa has consistently remained as the closest relative to neotheropods, so its relationship to them seems like a solid deal.

Tawa demonstrates then that neotheropods probably rose from this stock of early predatory dinosaurs somewhere, albeit if we’re not quite sure which ones yet. It at least means that it’s very unlikely the early predatory dinosaurs represent a totally distinct group of dinosaurs from the core theropods, which in the mess early dinosaur relationships currently are, is major step forward!

(Hayden Quarry dinosauromorphs, by Donna Braginetz for Issue 5836 of Science magazine.)

Tawa is also very interesting ecologically too! The fossils were discovered in Hayden Quarry in New Mexico, part of the Late Triassic Chinle Formation known for the likes of Coelophysis, Postosuchus, and Placerias of Walking With Dinosaurs fame. At this time of the Triassic, it was presumed early relatives of the dinosaurs, dinosauromorphs like Lagerpeton, Marasuchus and silesaurids, and early dinosaurs like herrerasaurs were already extinct, wiped out by their more advanced relatives. But Hayden Quarry has several of these older, ‘primitive’ groups living alongside more derived dinosaurs, including Tawa.

Tawa co-existed with Chindesaurus, a predator typically grouped with herrerasaurs, and coelophysoids. So the ancestral stock, intermediate ‘transitional species’ and the ‘advanced’ descendent forms were all still kicking about at the same time as each other. It tells us that the evolution of predatory dinosaurs, as well as dinosaurs as a whole, wasn’t as simple as the ‘advanced’ dinosaurs out competing their older, less successful antecedents, but that they lived alongside each for millions of years.

There’s plenty to say, but I think I’ve prattled on about Tawa for long-enough of a post, but I think that about covers the gist of it! Yeah, Tawa hallae, very lovely little theropod.

249 notes

·

View notes

Text

I told myself I would never make Yi qi-descended wyverns, but alas, here I am. XD (NOTE: the information on this creature will be given multiple posts [linked at the bottom] because I am having troubles getting it to post as one singular post. You can find the link to part #2 at the bottom.)

Wandering Amphiptere

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class/Clade: Reptilia (Sauropsida)

Clade: Archosauria

Clade: Avemetatarsalia

Clade: Dinosauria

Clade: Theropoda

Clade: Neotheropoda

Clade: Tetanurae

Clade: Coelurosauria

Clade: Maniraptoriformes

Clade: Maniraptora

Superorder: Scansoriopterygoidea

Order: Dracoviperoidea

Clade: Eudracoviperoidea

Family: Amphipterygidae

Genus: Ciconiavenator

Species: C. exulans (“wandering stork-hunter”)

Ancestral species: possibly Yi qi

Temporal range: early Pleistocene to recent (2 mya - present)

Information: As true flying dinosaurs, their distant avian cousins, attempted to colonize the skies, early wyverns found themselves in a predicament, unable to radiate into the large-bodied aerial predator niches the pterosaurs occupied (and continue to occupy) in near-totality, their uniquely specialized anatomy being both a blessing and a curse. As they began to increase in size, however, they faced competition from established coelurosaur clades, the troodonts and dromeosaurs in particular proving to be rather challenging to compete with, made even more complicated by the fact that the latter were now branching into arboreal niches themselves in the smaller microraptorian forms, and early mammals, too, were beginning to become more specialized in insectivore niches, which the early wyverns occupied. But whereas this would’ve normally spelled the end for such a clade, a minor extinction event near what was likely the Late Cretaceous gave them an opportunity to diversify: on the mainland of Archaeonesia, the microraptorians had gone extinct, along with several other clades of arboreal coelurosaurs. Based on genetic data, as the fossil evidence itself is too scarce to confirm directly, in this absence, they would begin to rapidly upsize and diversify, first radiating into the niches of small vertebrate predators and, over time, evolving into far larger forms which would eventually colonize mountainous areas, having outgrown the trees they once called home. It is only during the Paleocene, however, that direct fossil evidence emerges of this clade, and by then, they had already diversified into a variety of predatory niches, perfecting the art of gliding better than any group which came before. Continued: https://www.tumblr.com/captainswaglord500/767366398303420416/wandering-amphiptere-continued?source=share Continued 2: Electric Boogaloo: https://www.tumblr.com/captainswaglord500/767366685340712960/wandering-amphiptere-continued-2-electric?source=share Continued 3: You've Gotta Be Kidding Me!: https://www.tumblr.com/captainswaglord500/767366850349858816/wandering-amphiptere-continued-3?source=share

Continued (Part 4: The Final Chapter Part 1 [WHY, TUMBLR, WHY? T-T]): https://www.tumblr.com/captainswaglord500/767366997957902336/wandering-amphitere-continued-4-the-finale-part?source=share Continued (Part 5: The Final Chapter Part 2 [Please, I have a wife and kids!]): https://www.tumblr.com/captainswaglord500/767367092690386944/wandering-amphiptere-continued-5-the-finale-part?source=share

#scifi#fantasy#speculative evolution#novella#scififantasy#worldbuilding#fantasy creature#dragon#wyvern#sciencefiction#sci fi#speculative fiction#fantasy worldbuilding#scifi creature#scifi worldbuilding#dinosaurs#dinosaur

5 notes

·

View notes