#neogene period

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

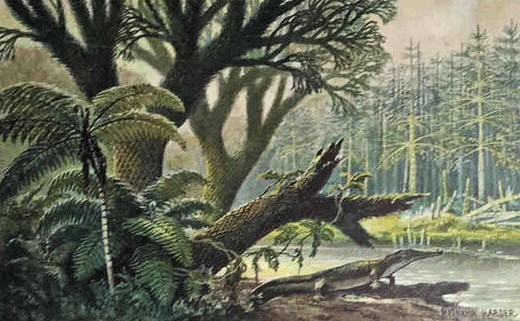

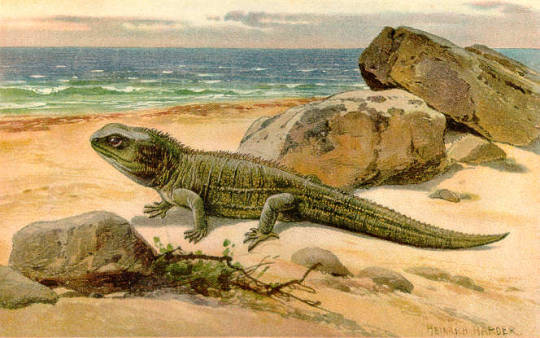

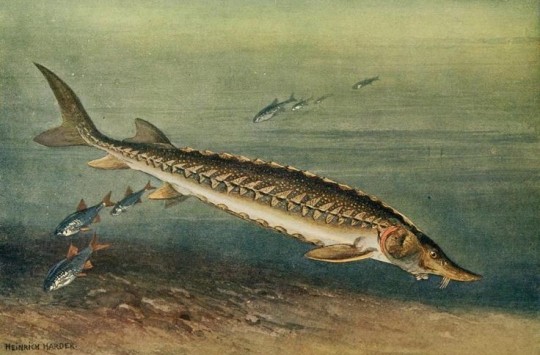

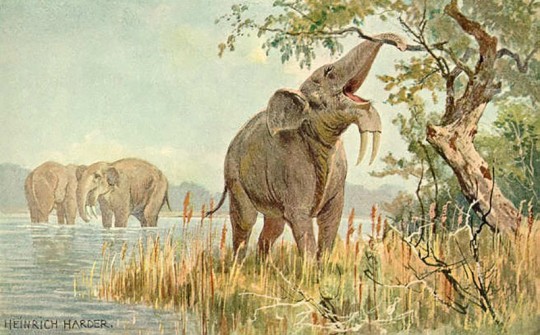

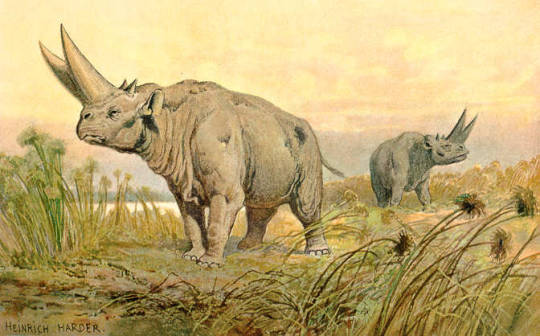

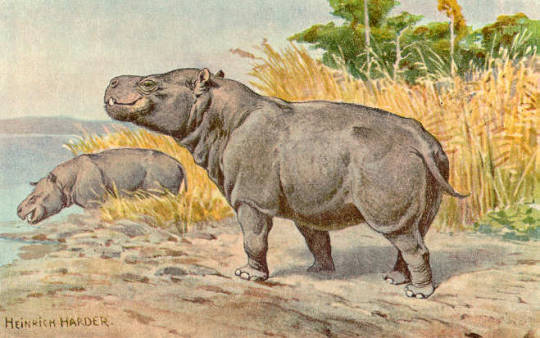

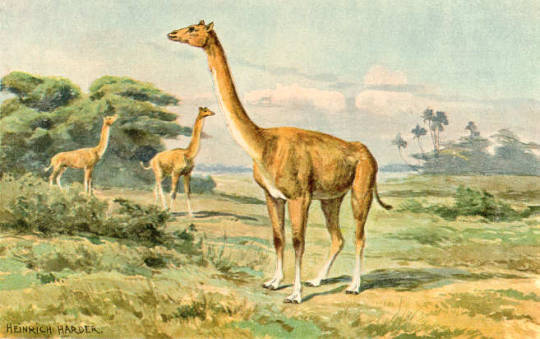

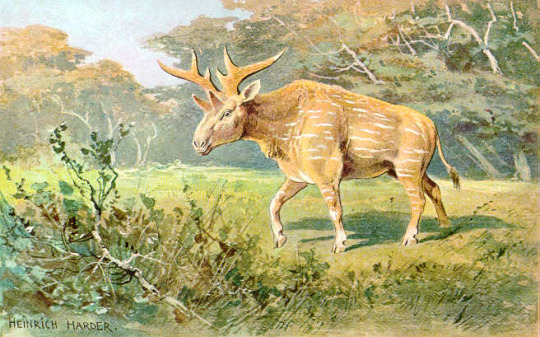

Animals of the Primeval World - art by Heinrich Harder (c. 1910)

#heinrich harder#animals of the primeval world#vintage palaeoart#vintage prehistoric art#natural history#palaeo artist#cenozoic#tertiary period#neogene period#1910s#1910

794 notes

·

View notes

Text

my life's work as someone who definitely didn't go to college and will have no impact on the earth is largely ignoring the existence of the Jurassic and Cretaceous period in order to prop up the history of life on Earth that is not the constantly presented non-scientific dinosaurs depicted in every piece of popular art. I do not wish to speak of the Triceratops, I wish to speak of when nearly all life onland was Lystrosaurus, big old cow-like synopsid with fangs. get your sauropods out of here, i want to talk about when crocodiles had land genuses and how we almost lived in a world where some still survived. i never want to see a fucking t-rex ever again, but the world should be as obsessed with sloth bears like megatherium as i am. get these fucking dinosaurs out of my face i want OTHER EXTINCT ANIMALS TO TAKE THE SPOTLIGHT AND I WILL BREAK THE WORLD IN ORDER TO SHOW YOU ALL----

#dinosaurs are a dead meme#kinda cringe to post them tbh#Dinosaurs#Megatherium#Synopsids#Permian Period#Permian Extinction#Triceratops#Crocodiles#Alligators#Jurassic#Triassic#Cretacious#Devonian#carboniferous#Cenozoic#Paleocene#Eocene#Oligocene#Neogene#Miocene#Pliocene#Pleistocene#Mammals#Reptiles#Birds#T-Rex#tyrannosaurus rex#Sauropod#i don't know how to tag this

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The seven deadliest seas of all time.

#sea monsters#chased by sea monsters#walking with#cretaceous period#jurassic period#pliocene epoch#eocene epoch#devonian period#triassic period#ordovician period#mine#tbh the neogene was deadlier than the cretaceous since there were the raptorial sperm whales in addition to megalodon#the current day ocean is probably the actual deadliest in earth's history with pirates battleships and submarines in addition to pollution#q

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

345 notes

·

View notes

Text

well it still took me like 8 hrs to beat her. can't forget that lmfao. i think the big easy to parry attack just worked rlly well for my playstyle.

au where fusang was only like 60% done at the start of the fight so by the end its only at 80% so eigong tries to bide her time like yanlao did (lmfao what is it with old ppl and bad timing hahahahahahahahahahaha) but it!! doesnt work and he fuckin Gets Her. Please. Pretty please

#spamming the parry button my beloved. you cant die from an imperfect parry and i LOVE the less than 25% health jade#OH ALSO. was jamming out so hard to the music shift that i got so in the zone for the 3rd phase lmao#shout out to youtuber lindsay Nikole for the sick video i was listening to that ended RIGHT AS I BEAT HER. the neogene period is fascinatin

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

No cheating, please! Answer the trivia question to the best of your ability, then check below the cut! Please do not give away answers in comments or tags!

Answer below:

The triceratops lived in the Late Cretaceous period.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triceratops

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

October's Fossil of the Month - Simbakubwa (Simbakubwa kutokaafrika)

Family: Hyena Cat Family (Hyainailouridae)

Time Period: 23-22 Million Years Ago (Early Neogene)

Currently known only from fossilised teeth and lower jaws discovered in Kenya's Messa Bridge fossil site, Simbakubwa kutokaaffrika was originally described as a prehistoric species of hyena before reexamination of fossils housed at the Nairobi National Museum of Kenya led to it being reclassified as a hyaenadont (a member of the extinct order Hyaenadonta, the members of which were generally dog-like animals with similar jaws and teeth to modern hyenas, although their teeth differed from true carnivorans today in that they lacked modified molars used for crushing and tearing seen in animals such as bears and dogs, and seemed to grow their teeth in slower than most modern carnivores.) While the limited variety of Simbakubwa fossils means that much of its biology is a mystery, it is notable among the hyaenadonts because of its size; estimates of its body size based on the size of its jaws suggest that, while most hyaenodonts were comparable to a large dog in size, it was at least as large as a lion, with the most generous estimates suggesting that it may have weighed as much as 1,500kg/3,307lbs (surpassing even modern Polar Bears in size,) although as the more complete fossils of related species suggest that members of the "hyena-cat" family of hyaenodonts that Simbakubwa belonged to had extremely large heads compared to their bodies it is unlikely that it actually reached such as size. Based on the shape of its teeth and the presumed strength of its jaws it is likely that Simbakubwa was purely carnivorous and fed on large mammals such as rhinoceros and gomphotheres (extinct relatives of modern elephants,) although based on the lack of any preserved teeth showing adaptations for crushing it is unclear if members of this species also fed on bones as other hyaenodonts and modern hyenas are known to do. While the circumstances of Simbakubwa's extinction are unclear, it is plausible that as the earth gradually became cooler and drier as it approached a series of "ice ages" in the later neogene resources became scarcer and large carnivores were among the first species to be affected by this. While the binomial names of most species are derived from Greek and/or Latin, Simbakubwa kutokaaffrika is Swahili, translating roughly to "great lion from Africa."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

*Note - The second image above shows a Simbakubwa lower jaw (bottom) compared to a modern Lion skull (top.)

Image Sources: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Simbakubwa-kutokaafrika_2.jpg

and

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/new-species-ancient-carnivore-was-bigger-than-polar-bear-hyaenodonts

#Simbakubwa#hyeanodont#hyaenodonts#zoology#biology#paleontology#mammalogy#prehistoric wildlife#animal#animals#wildlife#African wildlife#African fossils#fossil#fossils#mammal#mammals#prehistoric animals#prehistoric mammals

253 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trying to find others who are elderly like I am...

If you don't know, make sure to look it up before saying other :>

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

I get that complex life had a way faster rate of morphological evolution and that it makes sense to subdivide the Phanerozoic (and Ediacaran. Please split the Ediacaran at Gaskiers) in smaller periods than the Proterozoic.

But like. Evolution wasn't magically faster in the Cenozoic than the Paleozoic. Now, the amount of species was higher, but that's because of fragmented post-Pangea habitats and flowering plants offering more specific ecological niches. Still, stuff wasn't happening faster, and subdividing the late Cenozoic in absurdly small amounts doesn't reflect the actual rate of "stuff happening".

#i'm mildly against merging the whole cenozoic into one period because that means the two longest periods are back-to-back#and the timescale feels unbalanced in the other direction#but splitting into paleogene and neogene is already largely enough#and if you want that split to make sense bring the oligocene in the neogene

383 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fossil Novembirb 12: Peak Penguin Party

The Eocene was one of the golden ages of penguins - having gotten their start right away in the Paleocene, this group was exceptionally common during the Eocene, found throughout the Southern Hemisphere, reaching larger sizes and weirder shapes than penguins today. So, since we've been spending too much time on Europe and North America, we're diving right in to the Penguin Party! In fact, while today there are 6 genera of penguins, the Eocene had 17 - and given fossil taxa tend to underestimate diversity...

Anthropornis by Caz41985

One of the more famous of these penguins was Anthropornis, possibly the largest known genus of penguin, ever. Reading up to 2 meters in height, it's nearly twice as tall as the living Emperor Penguin - and would have essentially been the size of person, a tall one at that. It was the largest, but one of many, giant penguins that lived during the Eocene and into the Oligocene - and possibly even through to the Miocene. Unlike living penguins, it still had a bent joint in its wing, making it somewhat less efficient in terms of ocean swimming. Like the living emperor penguin, it lived in Antarctica, and also in Aotearoa.

Icadyptes by @quetzalpali-art

Pachydyptes was another large penguin, found in Aotearoa, and was the second tallest known species of penguin after Anthropornis. Its slightly smaller cousin, Icadyptes, had an extremely long beak like that of a heron, and may have hunted for fish very differently than its relatives, possibly using it to spear fish and squid rather than catching them outright. Icadyptes lived in Peru, living in warmer latitudes than most other penguins at the time, which would have been extra warm due to the hothouse world - only a few penguins today live in such temperatures.

Inkayacu by @iguanodont

Peru was also the home of Inkayacu, a contemporary of Icadyptes. Unlike living penguins, it was very differently colored - having grey and reddish brown coloration rather than black and white. Not only is this an exciting fossil of color in a dinosaur, it also indicates our assumption that penguins have always looked the same is probably extremely incorrect - and who knows what other kinds of color variation they may have evolved over the millennia! Despite not being a completely modern penguin, it did have feathers that were beginning to be adapted for efficient movement through the water. Being smaller than other contemporary penguins, it probably wouldn't have dived particularly deep.

Aprosdokitos by @thewoodparable

Of course, not all the penguins of this time were large! Mesetaornis was smaller like living species, but had really long toes compared to other penguins, even still using the fourth toe. Still having the bend in the wing, it wasn't an efficient swimmer like living small penguins, indicating that the larger size was probably not to aid with swimming efficiency. Aprosdokitos, an extremely small penguin from this time, was also known from the later Eocene of Antarctica like Mesetaornis. In fact, Aprosdokitos was only a little bigger than living Little Penguins. There must have been a lot of niche partitioning going on between all these kinds of penguins!

Kairuku by Tim Bertelink

Kairuku shows up at the tail end of this period and was one of the last of the Large Penguins, and had particularly long legs for a penguin even at the time. Some also had slender long beaks like Icadyptes, and was probably an excellent diver, able to go deeper than living species of penguin. In fact, there were so many species of Kairuku that were all contemporaneous, they may have had niche partitioning based on their preferred prey or diving range.

Mesetaornis by @drawingwithdinosaurs

As the Paleogene transitioned into the Neogene, penguins become less common, with smaller and more modern-type species replacing the large and less efficient swimmers of the Peak Penguin Party. The reasons behind this transition remain uncertain: competition from newly evolving pinnipeds and other marine mammals? Climate change? New forms of fish and other food sources? The answers will only come with more research. But penguins would bounce back for another round in the Neogene, through to today.

Sources:

Giovanardi, S., D. T. Ksepka, D. B. Thomas. 2021. A giant Oligocene fossil penguin from the North Island of New Zealand. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 41(3): e1953047.

Hospitaleche, C.A., Reguero, M. and Santillana, S., 2017. Aprosdokitos mikrotero gen. et sp. nov., the tiniest Sphenisciformes that lived in Antarctica during the Paleogene. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie-Abhandlungen, 283(1), pp.25-34.

Mayr, 2022. Paleogene Fossil Birds, 2nd Edition. Springer Cham.

Mayr, 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance (TOPA Topics in Paleobiology). Wiley Blackwell.

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

167 notes

·

View notes

Note

i'd love to hear you talk about terror birds, i don't think i've heard of them. - gutz

love you for this gutz oh my god

i love paleontology so much i wish i took it instead of business god kill me

please dont mind the silly nature about this post because this is one of my only interests and i never get to gush about them ever i cry at night wishing i owned one of their skulls or some of their fossils in general

TERROR BIRDS!! (phorusrhacids)

phorusrhacids lived from the middle paleocene epoch to early pleistocene epoch (during paleogene, neogene and quaternary periods, 62–2 million years ago). (which means our ancestors dealt with them.) (we were hunted by birds in the past.)

they were carnivorous and they were huge. it's like if ostriches went sicko mode and started eating every breathing thing in its environment. but they arent related to ostriches. sadly. these giant fucks to nature are direct ancestors to falcons, instead.

one of the largest specimens we have to current date, from the early pleistocene of uruguay, possibly belonging to devincenzia, would have weighed up to 350 kilograms (770 lb in freedom units) and actually is speculated to have gotten to around 3-4m tall (9-12ft in freedom units)

the closest living connection to them that we know of is actually not even falcons, is seriemas!! (look at those beautiful shits.)

when it comes to wingspan, one of the terror birds absolutely PEAKED OUT; the argentavis. just,,, JUST LOOK AT IT??

I LOVE YOU ARGENTAVIS. (not THE biggest wingspan of dead birds, that belongs to the pelagornis, BUT STILL. FUCKING. HUGE.)

again, circling back to the diet part here quickly before i talk too much, these guys were monsters. their beaks, as you have probably noticed in the photos ive added to this post, are pointed and curved for easier attack and gutting of their prey. their claws were also thick and sharp, similar to, you guessed it, falcons.

"oH, bUt PuDdLeS, aReNt ThEy SlOw?? CaUsE tHeY'rE sO bIg!!!1!" NO. THEY WERE FAST AS SHIT. FASTER THAN FUCKING HORSES.

LIKE RACE HORSES AT MAX SPEED TYPE HORSES. THESE GUYS WERE DEMONS.

these birds were so fucking metal that they even drove the remaining mammalian predators to hunt and live in forested areas instead of the plains that they thrived in. the birds fucking RULED the place.

their only competitors/natural predators were fucking SABERTOOTH TIGERS.

let me reiterate that,

ONLY SABERTOOTH TIGERS ATE THESE BIRDS.

im gonna cut myself off here because it's late as shit, im hearing fucking static again, and i have classes tomorrow at seven in the fucking morning

(fuck them for that, honestly. i have enough shit to deal with already and they keep me in the building for seven hours straight when we dont even have lectures anymore and we are more than able to do this shit at home, gas is SO expensive now.)

but oh my god if this interests you PLEASE go look more into them, or the very least, listen about them from lindsay nikole (the queen of this field of study) they show up in the neogene period video like really early in.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

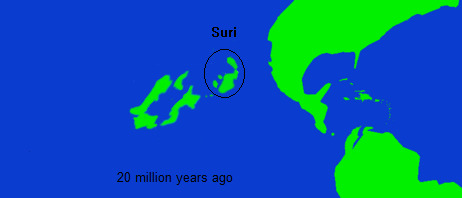

Paleontological Biogeography of Niur

The unique characteristics of Niuri fauna (and to a lesser extent flora) have been shaped by the geology and isolation of the islands, as they moved through time and space, as well as the unique conditions surrounding them.

Already at the start of the Paleocene, the landmass that would one day form the Niuri islands was already somewhat loosely attached to the South American mainland. Although it fluctuated with sea levels, for most of this period only an isthmus connected the two, and this prevented total faunal exchange from occurring, allowing, even then, isolation enough for the Niuri fauna to diversify separately from their South American relatives.

The Niuri landmass was climatically quite different from the neighboring region of South America, which additionally was a factor limiting the free transfer of organisms back and forth between the landmasses. Even so, outside of insects and some other groups of invertebrates, the fauna of the Niuri landmass, and for the most part the flora, was largely indistinct from that of South America until the middle of the Paleocene, differing mainly in the varying amounts of taxa found rather than the types. Towards the middle Paleocene , however , a low lying area in the middle of the Niuri landmass began to sink and was flooded, first as a large lake and then shortly after as a bay.

In tens of millions of years this bay would become part of the Faln sea, but even from its formation it began to change the life in the surrounding area. The most immediate effect was the change in marine fossils, as the shape of the land around the bay isolated it from the greater Pacific and also provided a unique habitat within it. Additionally, it triggered a further differentiation of the habitat of the Niuri landmass from the South American mainland, especially in the region of the isthmus. Finally, it is believed to have contributed to a broad shift in the climatic stability of the landmass as a whole, as prior to this point, the portion of Gondwana that would one day split of that would eventually become the Niuri landmass was subject to a high degree of climate instability , particularly in inland environments, and tended to support a very low diversity of megafaunal animals.

Beginning with the formation of the Paleo-Faln Bay the middle Paleocene the Niuri climate would change to instead become remarkably stable and consistent during the Neogene, much more so than neighboring continents or indeed most of the world. That said any semblance of stability during the last half of the Paleocene was rather abruptly interrupted by the end of that period.

The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum appears to have abruptly altered the environment of the Niuri landmass, and it triggered a rapid shift in its faunal makeup. Taxa which had previously been common throughout both Niur and the adjoining regions of South America disappeared or were heavily reduced in Niur, while some groups that all but disappeared in mainland South America continued to flourish in Niur. In the Ypresian, the first period of the Eocene, for the uniquely Niuri fossils of mammals, reptiles, and birds begin to make up a substantial degree of the Paleo record, by the beginning of the Middle Eocene the fossil taxa of Niur is almost wholly distinct from South American forms. It's also around this time when the last connection to mainland South America disappeared, and from then on Niur was an island landmass, drifting to the northwest on its Continental plate.

While it last was directly connected to South America no later than 40 million years ago, Niur was still close enough that birds, plants , some insects and bats could readily cross the gap. Even so this isolation was complete enough that from then on all future introductions of new fauna to the Niuri Islands are termed as distinct events. Even prior to becoming truly isolated, the faunal interchanges of Niur and South America in the Paleocene and Early Eocene are also considered to be distinct events, namely the First and Second South American introductions. The First Introduction refers to a period of time in the late Paleocene, where after some degree of distinction had already emerged in the islands some new faunal groups migrated over from South America. The more impactful Second Introduction occured immediately prior to the final severance, somewhere around 45-40 million years ago, perhaps caused by a temporary widening of the connection between the landmasses before it finally was buried under the sea. These new groups were subject to almost immediate, intense evolutionary pressures upon Niur's isolation, and those that survived rapidly diversified into new forms.

In the early Eocene, the western half of the Niuri landmass had been rendered an island and with the separation from South America, and these would retain separate faunal assemblages until the Oligocene, when changes in the landscape and sea level led to an interchange of animal taxa across the islands. The landmasses that composed these islands were heavily altered in position and shape, and are not to be confused with the two later proto-islands that would appear (along with Senika) later in the Neogene. The largest differences between these two assemblages were mammalian taxa, with birds and reptiles appearing to be less affected by the gap between them, although it's believed that the poisonous bird groups originated in the western island before also expanding into the eastern island as well. While both western and eastern islands included members of the initial mammalian assemblages, as well as those that arrived during the First South American introduction, the mammals that arrived in the Second and later Third South American (which occurred in the latest eocene or earliest oligocene, as a chain of islands allowed some taxa to island hop from northern South America) introductions were limited to the eastern island until the late Oligocene. Most prominent among the eastern limited animals were the Notoungulates, the Pyrotheres, and later the Astrapotheres and ameridelphian marsupials all of which would lead to unique Niuri taxa that are still extant. In addition to this, xenarthrans were present in the eastern island as well, although these remained species poor and went extinct by the end of the Oligocene. There are at least some teeth fossils that suggest that Litopterns may have briefly been present in the eastern island, in the mid Eocene.

Meanwhile the only major group of placental mammal to survive in the western island during this time period were the xenungulates (of the first South American introduction), which although initially being somewhat diverse and common in the early Eocene, afterwards appeared to have been in a long decline before disappearing in the Oligocene. The other mammals present in the western island were the various non-placental mammals, which along with the Niuri ameridelphians (Kaulodelphidae) , are collectively called "Koutou" in modern Niur, despite not being particularly closely related. These include the Gondwanatheres, and Polydolopimorphia, both present from the earliest Paleocene, and the Sparrassodonts, and the Xenodelphians from the First South America introduction. The Sparrassodonts were additionally present in the fauna that arrived during the Second South American introduction, and the new arrivals appear to have replaced the Sparrassodonts still present on the Eastern Island, although after the faunal interchanges in the Oligocene both Western and Eastern Sparrassodonts continued to flourish. Additionally, the Polydolopimorphia maintained high diversity on both western and eastern islands until the Oligocene, and all three modern families appeared nearly simultaneously on both islands before the faunal interchanges that unified the assemblages (although one extinct, enigmatic family that appeared to be endemic to the eastern island went extinct not long after).

Shortly prior to the Oligocene Faunal Interchange, there was one additional "introduction event" wherein, most likely via a single rafting event, salamanders were introduced to what is now Senika (which was the earliest modern island to differentiate itself clearly in the fossil record). In the Niuri paleontology this is called either the First North American Introduction or the Zero Suri Introduction, as its debated whether they rafted from North America or from the Suri islands. They would gradually spread during the rest of the Oligocene, before more heavily diversifying in the Miocene.

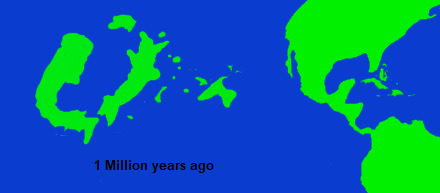

In the mid to late Miocene, the Suri islands, themselves subject to a long and generally less understood geological history, approached close enough to the east of Niuri that fauna and flora could exchange between these two island chains. The fossil record of the Suri islands is confusing, and this is further complicated by the fact that they have been subject to gradually increasing subsidence for the past 10 million years, which along with the rise of sea levels during the Holocene , has buried much of the former Suri landmass under the sea. This process of sinking was somewhat abated by a period of volcanism which created new land inbetween Suri and Niur, as well as contributed to the geological features of eastern Niur, that said much of this volcanism had dissipated by the Pleistocene.

The first evidence of an interchange between Suri and Niur, actually appears in Suri, around 15-18 million years , when rather abruptly various distinctly Niuri plant pollen taxa appear almost simultaneously throughout fossil sites in Suri. This is followed shortly after by Niuri avian fauna, which although less attested appears to rather rapidly replace the indigenous Suri birds (although how complete this replacement was is hard to say, given the fragmentary record). The introduction of Niuri life in Suri seemed to trigger a wave of extinctions as well as spur the new evolution of Suri life.

Generally it seems that during the Miocene, most introductions between Niur and Suri tended to follow the pattern of Niuri life establishing itself in Suri, with little managing to travel the other way. Following the avifauna, Niuri Astrapotheres and Xenodelphians arrived in Suri, becoming firmly established during the late middle Miocene. Around this time, the two island chains reached their closest point of contact, after which Niur would continue to drift eastward at a greater speed than Suri. Even so, because of the lowered sea levels during the Pliocene and Pleistocene, and continuing volcanicism creating temporary, connective archipelagos, the faunal interchanges would continue, although in separate pulses. The last phase of the the first Suri introduction was the point at which Suri fauna, perhaps finally adapted to the pressures of the Niuri arrivals, managed for the first time to make the journey to Niur. Between 10 and 7 million years ago, a variety of Suri taxa became established in Niur. The first, and most widespread of these groups, were the two Suri families of salamander, which now accompanied the earlier cryptobranchid salamanders that had been introduced in the Oligocene. Additionally, for the first time, rodents found their way to Niur, the small mouse like members of the family Sminthidae (one of the only rodent families to survive in Suri) adapted to alpine habitats in Niur, and in present at least five species are known in the genus Subtilicus. The one megafaunal introduction, though, was the most impactful, the carnivoran feneraks. These catlike predators are part of the larger clade Felarimorpha which is either a suborder of Carnivora itself or an infraorder of Feliformia (although some phylogenetic analyses have proposed that Felarimorpha might instead be the sister taxa of all other carnivorans) . Feneraks make up one of the two living clades of Felarimorphs, although the first feneraks in Niur were part of a now extinct group, often called the Crested Fenerak, after the unusual protrusions that later members developed on their skulls. Crested fenerak gradually spread throughout much of Niur, and took the place of the sparrasodonts as top mammalian predators (and indeed, in many habitats, as top terrestrial predators in general). Crested fenerak would continue to evolve in Niur, while new groups, more closely related to modern fenerak, evolved in Suri. Niur and Suri drifted away from each other, the first period of interchange ended, with the fauna of both islands profoundly shifted.

The two island chains, for much of the Pliocene, existed largely in separation from each other, although birds and plants still managed to easily cross from one to the other. Niur, especially the southern parts of it, has many plant genera in common with Central America and Northern South America, and while its unknown exactly when they made the journey there, many groups present are believed to be relatively recent evolutionarily speaking, and therefore may have been the result of birds ferrying their seeds from the continents , to the southern parts of Suri, and then to Niur. Most prominently, the wide variety of cactuses in Niur, many of which are relatively closely related to species found in North and South America, is believed to be caused by such patterns. This might also be where many of the Solanaceae present in Niur originate from, and unless the result of an ancient introduction by people, almost certainly how the genus Capsicum arrived.

Both Niur and Suri experienced environmental and ecological changes during the Pliocene, and in Niur at least, this lead to the decline of the crested-fenerak in most locations other than what is modern day Nirou, by the end of the Pliocene. Rather than disappear all at once, they seemed to gradually decline area by area, at first in the south of greater Kaita, with their disappearance spreading from there until they were restricted to the northern plains of Nirou. This disappearance was historically tied to the onset of the Second Suri introduction, which is considered to have started shortly before the onset of the Pleistocene, as lower sea levels and renewed volcanic activity again created a bridge between Suri and Niur, and allowed the dispersal of the modern feneraks into Niur. However, more recent research suggests that the crested-feneraks began their decline before modern feneraks arrived, and in fact it was only in areas where they had already disappeared that modern feneraks were able to establish themselves, with the exception of northern Nirou, where crested-feneraks survived for much longer and coexisted with their modern cousins until eventually going extinct during the late Pleistocene. There are five species of fenerak alive today in Niur, and they probably evolved from at least somewhat semi-aquatic ancestor (as the water-fenerak is today still) which managed to island hop to eastern Niur, although its unclear if this was the result of one or two introductions. The record throughout much of the Pleistocene is ambiguous, and the exact history of the fenerak might be better elucidated by further genetic studies. The other group of Suri animals that is typically considered to be part of the second introduction were the peccaries, which live today in various forests on the eastern Islands of Niur. Although their choice of habitats is different (both in Niur and Suri they exclusively live in relatively cool forests) they seem closely related to the American peccaries, to the point where its a bit of mystery as to how they arrived in Suri in the first place. Compared to the fenerak which are usually apex predators or at least dominant in their environments, Niuri peccaries, while locally common, tend to be more marginal parts of their ecosystem, and even still mostly live in areas where they have less competition from other mid to large size herbivorous animals.

There is no exact boundary between the Second and Third Suri introductions, because low sea levels throughout the Pleistocene meant that there was an almost continuous potential for island hopping between Niur and Suri. Rather, the Third introduction is defined by its most famous member, the people of Niur, the felar-mesai, who first arrived in Niur from Suri, sometime in middle Pleistocene. Because of their beliefs regarding remains of the dead and genetics, most studies on Niuri paleoarcheology have focused on material culture, and because of this many dates regarding the earliest records of people in Niur are subject to massive ranges. Its also unclear if the earliest people in Niur were members of the same species as present day mesai, and the fragmentary record of remains is complicated by the fact that there is a high degree of genetic diversity within the present day mesai (much more so than modern humans), meaning that any species level determinations based on bone fragments are highly contested. Different methods of dating have suggested various results of when the first people in Niur arrived (or at least, the first member of the clade of felarimorpha to which modern mesai belong to), anywhere from 150,000 to 800,000 years ago, a time range of over half a million years. These inconsistencies might be explained by the "lost seeds" hypotheses, which views these early records as evidence not of permanent populations but rather temporary, small groups of mesai, which periodically would arrive in Niur during certain climatic periods, which corresponded to a spread of specific Suri plant taxa in Niur, and then disappear when the climate shifted again and those plants became less common, without ever becoming fully established in Niur. Even those that oppose this theory, tend to view the populations of Niur during this time as being sparse and likely subsumed by later arrivals. The period around 120,000-70,000 years ago is seen as the first clear period of continuous inhabitation of Niur, and appears to correspond with a new group of people arriving from Suri, or at least a new material culture spreading from there. Even so, population density was incredibly low, and subsequent migration from Suri in various pulses continued until around 20,000 during the last glacial maximum. The mesai population in Suri would decline considerably after this point, with the last evidence of living mesai dating to perhaps around 10,000 years ago, although there may have been a very small remnant population until as late as 8,200 years ago.

Along with mesai, at least in the later migrations, included various semi-domesticated Suri plants, which form the bulk of the other arrivals during the Third Suri introduction. By the time of the last glacial maximum, the volcanicism that had created island chains between Suri and Niur had mostly subsided, and the islands that were left gradually sunk into the rising sea levels of the Holocene. The last remnants of that volcanism are the hot springs and mountains of Senika, Nacre and the islands to its north. Despite the massive changes in climate and land, as well as the arrival of people, most of Niur's native fauna remains highly successful, and incredibly distinct. Groups that have long gone extinct elsewhere thrive there, and its unique ecosystems have so far avoided the fate of other isolated environments that has so often come about as the result of new introductions. Outside of some plants and a few insects associated with introduced agriculture, almost no invasive species have managed to take hold in Niur, and few if any native taxa have gone extinct in the last 10,000 years.

On the contrary, the robustness of Niuri ecosystems have leant some Niuri taxa the ignominious status of being invaders themselves, mostly a handful of insects and plants, aside from one specific incidence where one of the large Niuri ratites (the Upland Takako) become established in parts of Spain after a failed attempt to farm them. These large birds have proved to be a nuisance in Spain, as well as being environmentally damaging, as they will kill foxes or other mammals they view as a threat to their eggs or young, as well as domestic goats and sheep they view as competition for food. Attempts to control them via hunting have been partially successful, although the surviving population (mostly in the Pyrenees) is much more wary of humans and traps and is also notoriously dangerous, sometimes injuring or even killing hunters (in addition to sheep and goats).

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you like the late Proterozoic just put it in the tags I ran out of options...

(rb for sample size)

*Info graphic below the cut

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animal Disinfectants Market Forecast to 2029: Key Players, Trends, and Opportunities

The global animal disinfectants market is projected to grow from USD 3.9 billion in 2024 to USD 5.7 billion by 2029, registering a CAGR of 7.9% during the forecast period. The versatility and wide-ranging applications of animal disinfectants make them an essential component in maintaining livestock health and welfare. These products are particularly effective in eliminating harmful microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites, which can thrive in animal housing, equipment, and surrounding areas.

Regular use of animal disinfectants significantly reduces the risk of disease outbreaks, ensuring a safe and healthy environment for livestock. They are frequently utilized in settings where cleanliness is paramount, such as farms, veterinary clinics, and animal shelters. When choosing a disinfectant, factors such as the type of pathogen, the surface to be sanitized, and potential impacts on humans or animals must be carefully considered. Effective disinfection, combined with stringent hygiene and biosecurity protocols, is critical for preventing and managing biohazards.

Download PDF Brochure: https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/pdfdownloadNew.asp?id=38718363

Dairy Cleaning: A Leading Application Segment

Dairy cleaning is expected to dominate the animal disinfectants market between 2024 and 2029. Disinfectants play a vital role in eliminating pathogens from dairy equipment, surfaces, and facilities. According to the United States Department of Agriculture, the global cattle population exceeded 1 billion in 2022, driving demand for animal disinfectant products. Proper cleaning of milking machines, teat dips, and milk tongs minimizes pathogen transmission and helps ensure the production of safe, high-quality milk.

Cleaning protocols often involve the use of acid or alkaline solutions for equipment, while hydrogen peroxide combined with peracetic acid is commonly employed for sanitizing pipelines and storage tanks. Regular application of disinfectants in areas like milking parlors, holding pens, and feeding zones not only fosters a healthier environment for animals and workers but also enhances the overall efficiency of dairy operations.

Iodine: A Dominant Disinfectant Type

Iodine-based disinfectants are expected to hold the largest share within the type segment of the animal disinfectants market. Renowned for their broad-spectrum efficacy against bacteria, viruses, and fungi, iodine products are a preferred choice in animal healthcare and biosecurity. Additionally, iodine-based solutions are regarded as relatively safe and less toxic, driving their popularity in the market.

In 2021, Zagro launched IOGUARD 300, a powerful iodophor-based disinfectant containing 3.4% iodine. This product is highly effective against bacteria, viruses, and fungi and is designed for use in livestock housing, equipment, and hatcheries. The combination of iodine’s benefits and continuous innovation by key companies is expected to solidify its dominance in the market.

Request Sample Pages: https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/requestsampleNew.asp?id=38718363

North America: A Key Regional Market

North America is projected to hold a substantial share of the animal disinfectants market, with key contributors being the US, Canada, and Mexico. The USDA reported significant growth in poultry production in the region between 2020 and 2022, with Mexico's production increasing from 983.43 million to 1.25 billion and Canada’s rising from 350.26 million to 563.94 million. This surge highlights the growing need for effective animal disinfectant products to maintain biosecurity and livestock health in intensively populated farming operations.

Leading Animal Disinfectants Manufacturers:

Key Market Players in this include Neogen Corporation (US), GEA Group Aktiengesellschaftv (Germany), Lanxess (Germany), Zoetis (US), Solvay (Belgium), Stockmeier Group (Germany), Kersia Group (France), Ecolab (US), Albert Kerbl GmbH (Germany), PCC Group (Germany), DeLaval Inc. (Sweden), Diversey Holdings Ltd. (US), Virbac (France), Kemin Industries Inc. (US) and Fink Tec GmbH (Germany).

#Animal Disinfectants Market#Animal Disinfectants#Animal Disinfectants Market Size#Animal Disinfectants Market Share#Animal Disinfectants Market Growth#Animal Disinfectants Market Trends#Animal Disinfectants Market Forecast#Animal Disinfectants Market Analysis#Animal Disinfectants Market Report#Animal Disinfectants Market Scope#Animal Disinfectants Market Overview#Animal Disinfectants Market Outlook#Animal Disinfectants Market Drivers#Animal Disinfectants Industry#Animal Disinfectants Companies

0 notes