#mythos and logos

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Early Greek prose inquiry (historia) and mythical tradition-V

The Early Greek Prose-writing Tradition: Bridging the Myth-History Divide

Gaston Javier Basile

Dans Dialogues d'histoire ancienne 2019/2 (45/2), pages 81 à 112

“IV- Conclusions

This paper has tried to illustrate the engagement of early Greek prose inquiries (historiai) with the mythical tradition of Homer, Hesiod and the archaic poets. Naturally, the process should not be read in terms of advancement, progress or the realization of a telos (such as the transition from poetry to prose, orality to script culture or mythos to logos) but as the emergence of new discursive genres and cognitive schemata – possibly facilitated by certain technical and intellectual developments – that fostered a reworking of tradition and the use of alternative expressive means. It has been the aim of this paper to further ‘deconstruct’ the deep-seated myth/history polarity by redefining certain terms of the controversy. A crucial assumption in our discussion is the broad notion of historia, which is not understood anachronistically in terms of truth claims and fidelity to the facts of the past (whatever that may mean even today) but rather as a cognitive category and discursive mode that comprised a variety of intellectual undertakings throughout the archaic and classical period. In our view, historia designates an individual, comprehensive and active mode of inquiry bearing on empirical matters or involving a first-hand gathering and record of experience or source analysis. This inquiry adopted a new form of discourse: expository texts, largely narrative or descriptive, written in prose.

The myth/history divide – if we are to retain the slippery distinction – has been expatiated here in terms of the inception of new commentarial and heuristic procedures by writers through the sixth and fifth century and the development of new discursive prose types. These texts offered unprecedented expository and argumentative leeway for the engagement with the mythical past and the exploration of new forms of knowledge that often diverged from or criticized the mainstream poetic accounts. Some of the procedures deployed by early prose writers surveyed in this paper are: a) the emergence of an enunciator third-person voice in the narrative in charge of explaining or commenting on the source text; b) the production of synoptic and organic narrative accounts from the multifarious assortment of oral traditions; c) the recourse to etymology and verisimilitude in the appraisal of myths in the earlier texts, which soon turned into more sophisticated modes of explanation including reasoning by induction and deduction (as is the case with Herodotus); d) the anchoring of myths to the ‘realia’ – whether topographical sites, cult heroes, cult practices, etc. – or the historicization of myths; e) the treatment of myths and legends as ‘sources’ or testimonies that are open to various and often conflicting interpretations, as featured chiefly in Herodotus’ approach.

The change of medium plays a pivotal role in this reworking of the mythical legacy and the new intellectual pursuits. The abandonment of poetry in favour of prose can be envisioned as the response to the adaptation of language to new audiences, to new areas of inquiry, social needs and modes of circulation of knowledge. On the other hand, the choice of prose both required and favored a preeminent authorial control over the text, and called for the inscription of contextual elements (traditionally activated through performance) into the linguistic co-text. In sum, our analysis shows that these broadly-defined early prose-inquiries display a number of discursive strategies and commentarial procedures that depart from those deployed by poetic discourse (as featured chiefly by the Homeric, Hesiodic and elegiac traditions), but also (we can surmise) from the kind of prosaic speech that is generally associated with in vivo, spoken, oral interaction. Thus, early prose, largely of an expository type, exhibits procedures that recur in several distinct prose genres and that are explicated not only in terms of subject matter or disciplinary interests, but also of functional, pragmatic or sociolinguistic adjustments of language. Moreover, far from being a natural, default occurrence stemming from the abandonment of meter as an expressive medium, the linguistic fabric of early Greek prose reveals traces of its ‘constructed’ nature which have not yet been fully explored.

Notes

[1]Willhem Nestle’s developmental account of the progress of the Greek thought has been radically challenged over the past two decades (see, for example, the collection of essays in Buxton 1999). For a recent re-evaluation of the mythos/logos polarity, see Fowler 2011; Baragwanath, de Bakker 2012. On the applicability of the term mythos in the contemporary sense to Greek literature in general, see Calame 1996, 1999; Detienne 1967, 1986. [2]On this see Connor 1993, p. 7. See Hesiodus, Opera et Dies, 792 who talks about a “sound-witted” or sagacious man being born (ἵστορα φῶτα); Homer, Odyssea, XXI, 26 for Heracles’ skill at killing, or the Homeric Hymn (to Selene) for the Muses who know or are skilled in songs. Also Bacchylides in his Epinicians (poem 9) refers to the Amazons as “the women skilled with the spear” (ἐγχέων ἵστορες κοῦραι). [3]Cf. Lateiner 1986; Thomas 2000, p. 134-167. For historia as the new kind of research into the human past as initiated by Herodotus, cf. Bakker 2002, p. 15-19; Schepens 2007; Hartog 2001, p. 27-28; Lachenaud 2004, p. 12-19. [4]See Hartog 2001, p. 395-459; Schepens 1975; Fowler 1996; Fowler 2001; Bakker 2002; Schepens 2007, p. 42-45. On the connection between the ἵστωρ and ἱστορία, see Snell 1924; Nagy 1990, p. 250; Dewald 1987, p. 153; Thomas 2000, p. 164; Hartog 2001; Bakker 2002, p. 13-19; Darbo-Peschanski 2001, 2007; Schepens 2007, p. 39-55. [5]See Louis 1955; Lennox 1991, n. 4; Gotthelf 1988, n. 6. Cf. Aristoteles, Rhetorica, I, 4, 1359b22, 1360a24; III, 9, 1409a28; Problemata, XVIII 917b8; Poetica, 1451b1 and 1459a21-24; Analytica priora, 30, 46a24; De Caelo, III, 1, 298b2; De anima, I, 1, 402a4; Historia animalium, I, 6, 491a12, 2; De Generatione animalium, III, 8, 757b35 (historikôs). [6]Cf. Thomas 1992, 2003. [7]Cf. Kahn 2003; Asper 2007. [8]Herodotus’ “splendid isolationism” within the early Greek prose writing tradition has been the standard view in the second half of the twentieth century. This scholarly approach – which tended to separate Herodotus from his contemporaries and the early prose writing tradition – was grounded on Jacoby’s evolutionary model of explanation of Herodotus’ career. See Luraghi 2001, p. 6. [9]The collection of essays in Most 1997 offers a good starting-point for the classical tradition and its engagement with fragmentary sources. On the sources of ancient scholarship and the fragmentary nature of much of the extant material, see Dickey’s 2015 comprehensive overview, in particular, her discussion of fragmentary grammars, commentaries, lexica and scholia, p. 493-497. For cautions and important methodological approaches to dealing with fragments see Brunt 1980 and Schepens 1997. [10]On the use of the word logographos, see Thucydides, I, 2, 21; Hellanicus, T23; F25b; also Palaephatus, I, 11-16; 26. On the ancient historians, see also: Strabo, VIII, 3, 9 (Hecataeus, T10 = F25); Strabo, I, 2, 8; I, 2, 35 (Hellanicus, T19); Plutarch, De Iside et Osiride, 20; Polybius, VII, 7, 1. The term logographos in antiquity – though scarcely used – was loaded with pejorative overtones (Aeschines, In Ctesiphon, 173, De Falsa Legatione, 180; Demosthenes, XIX, 246, 250; Plato, Phaedo, 257C) and was employed as a term of abuse by rhetoricians and by Thucydides in his disparagement of his predecessors (Thucydides, I, 21). The general derogatory sense attached to the word was that of lack of accuracy, lack of concern for the truth claims of the narration or an inclination toward the fabulous. [11]Brill’s New Jacoby (online) is a fully-revised and enlarged edition of Jacoby’s FGrHist I-III with English translations and critical commentaries. [12]On the transition from poetry to prose, see Krischer 1965; Lang 1984, p. 37-51; Nagy 1987; 1990, p. 17-51, 215 f.; Herington 1991; Bakker 2002; Boedeker 2002, 2003, with further bibliography; Marincola 2006, 2007. [13]On early Greek prose in general, see Norden 1898; Zuntz 1972; Denniston 1952; Lilja 1968. For Attic prose and its connection to orality and performance, see the recent study by Vatri 2017. For a general discussion about Herodotus and his prose predecessors, see Thomas 2000; Fowler 2000, p. xxvii-xxxviii ; 2001; Raaflaub 2002; Fowler 2007. For Hecataeus, see Bertelli 2001; for Ion of Chios, see West 1985 and Dover 1986; for Hellanicus, see Möller 2001; for Antiochus of Syracuse, see Luraghi 2002. On Herodotus' text as ‘exceptional’ in the context of early Greek prose, a work which defies generic categories and establishes intertextual relations with (often blending) multiple discourse types, see Bakker 2007; Thomas 2007. For the overlapping and fluid genre distinctions in these early prose writers, see Marincola 1999; Fowler 2007, p. 96-98. [14]This is the view adopted by Murray 2001, p. 34, who sees Herodotus as the heir of an oral tradition of Ionian logopoioi (storytellers). Though Herodotus certainly draws on an oral tradition, in my view, his work is best understood within the general framework of an Ionian prose-writing tradition (which he incidentally criticizes, updates and reworks in view of his subject matter and the influx of the fifth-century intellectual milieu). [15]On the difference between oral and written conceptions as two poles of a continuum, see Oesterreicher 1997, p. 192-193; Tannen 1982; Chafe 1982, p. 49; Bakker 1997, 1999; Vatri 2017, p. 1-22. [16]In relation to the genesis and circulation of Herodotus’ logoi, see Lateiner 1989, p. 4-8; de Jong 2002; Evans 2008. It is still unsettled whether Herodotus lectured in front of an audience, read or improvised based on annotations or delivered a full text. Possible venues for Herodotus’ logoi may have been the symposium, the palaestra, private houses as well as pan-Hellenic gatherings such as the Olympic Games or religious festivals (see Stadter 1997). [17]Cf. West 1971, p. 3-4; Fritz 1938; Toye 1997 and Fowler 1999. See Schibli 1990, fr. 1, 2, 9, 10, 11, 12 for testimonia attributing the first prose narrative to Pherecydes. [18]This vexed question has been recently revisited in a collection of essays exploring the interface between myth and history in Herodotus (cf. Baragwanath, de Bakker 2012). A change in scholarly approach has started to come to terms with the mythical content of Herodotus’ Histories in its own right, rather than seeing it as a residue or remnant of an archaic mentality which detracted from the text’s historical rigour (cf. Griffiths 2006). The commonplace term for any kind of tale in Herodotus is logos, while the term mythos is only used twice (in the restricted sense of unaccountable story). As to the long-debated question of whether Herodotus identifies a spatium mythicum as separate from a spatium historicum, equally plausible arguments have been proposed on either side (answering in the affirmative: inter alia Shimrom 1973; Fornara 1983, p. 6-8; Darbo-Peschanski 1987, p. 25-38; Canfora 1991, p. 5-6; in the negative: Hunter 1982, p. 93-115; Harrison 2000, p. 203-207; Cobet 2002, p. 405-411). [19]Prosification is as a standard procedure in cultural development over time. Mise en prose is a fully-fledged, complex, literary transformation that involves a new expressive medium altogether. As the case of medieval renderings of verse into prose shows, the prosator excises, condenses or expands segments of the poems, but also produces omissions or additions. On the exegetical and critical use of tradition by the early prose writers, see Bertelli 2001, p. 69. [20]See, for example, Hecataeus, F15 and the genealogy of the Deucalionids; also, his correction of Hesiod in F26. On Hecataeus’ ‘rationalism’ see Momigliano 1931; Gitti 1952; Tozzi 1963; 1964; 1966; Bertelli 2001, p. 84-89; Fowler 2013, p. xv-xvi. For a comprehensive recent examination of the Greek tendency to rationalize myths and its implications, see Hawes 2014, p. 1-36. [21]Hecataeus, F1. [22]De elocutione, 12. [23]These programmatic opening lines have received considerable scholarly attention. See Calame 1986, p. 81; Corcella 1996; Svenbro 1988, p. 166; Bertelli 2001, p. 80-81; Fowler 2001, p. 101-103. Hecataeus’ critique of the Greek logoi, which are many (polloi) and absurd (geloioi), probably entailed making corrections, amendments or offering conjectures of his own or drawing on local traditions. [24]On the importance of the Hesiodic Catalogue in the works of the first prose genealogists, see Bertelli 2001. [25]See, for instance, Herodotus, II, 143 (= Hecataeus, T5; 6; 7) reporting Hecateus’ alleged conversation with the Egyptian priests at Thebes; also Hellanicus’ Priestesses of Hera attempts at chronology as an alternative to the old reckoning by generations. The use of prose to render poetic genealogies cannot be regarded as a simple and unproblematic change of medium, as sometimes believed. The choice of prose rather than verse enables a critical attitude to the genealogical material (see Bertelli 2001). As to whether there are traces of any chronological criteria in the organization of these genealogies, see Mitchel 1956 – who rejects Meyer’s 1892 forty-year generation span in Hecataeus –; Fowler 1996, p. 75, Bertelli 2001, p. 90-95; Fowler 2001, p. 103-105. For the transition from relative chronology to absolute chronography, see Mosshammer 1979. On Hecataeus FGrH I F1-35, see Meyer 1892; on Pherecydes FGrH 3, see Ruschenhusch 1995, 1999, 2000; on Hellanicus FGrH 4 F74-86, see Jacoby 1912, p. 114-127. For a discussion of the organization of time in the Histories and whether Herodotus elaborated a systematic chronology, see Cobet 1999, p. 604-605; Asheri 1988, p. cxii; Cobet 2002. Cobet 2002, p. 411 distinguishes three time periods in the Histories: “1) the complex stories about beginnings, the age or the Greek poets’ gods and heroes, traditionally the mythical period; 2) the meagrely filled in a ‘floating gap’ or Dark Age; 3) the spatium historicum in the proper sense, to be divided into the horizon of the oriental kings and the ‘recent past’ of the three generations”. [26]See Pearson 1939, p. 152-235; Ambaglio 1980, p. 40-41; Mösler 2001, p. 241-262. [27]For a general outline of some of these procedures common to the early Greek prose writing tradition, see Bertelli 2001; Möller 2001; Raaflaub 2002, p. 157-158; Fowler 2007, p. 37-38. [28]The genealogy of the Deucalionids (Athenaeus, II, 35 = Hecataeus, F15); the real nature of Cerberus the “dog of Hades” of Cape Taenarum (Pausanias, III, 25, 4 = Hecataeus, F27); Hecataeus, F19 (Aegyptus’ sons); Hellanicus of Lesbos, F111 (vitulus/Vitulia) F28 (rationalization of Iliad, XXI, 242); F175 (etymology of Osiris); Hecataeus, FGrH 1 F22 (Mykenai is derived from Perseus’ scabbard μύκης). Similar procedures are used by Herodotus in his Egyptian logos to discuss mythological and/or ethnographical and historical material. Herodotus, II, 28; 30; 44-46 (Heracles); 52; 56-7 (foundation legend of the oracle of Dodona). Herodotus also deploys more sophisticated modes of explanation including reasoning by induction and deduction. [29]On the various ways in which ‘names’ often generate myths, see Kraus 1987, p. 18; Leclerc 1993, p. 271; Peradotto 1990, p. 107-108. On ancient, especially Greek, etymology, see the comprehensive discussion by Sluiter 2015. [30]Odyssea, XIX, 406-408. [31]Theogony, 140-144. [32]Theogony, 280-284. [33]Cf. Odyssea, VII, 54: Ἀρήτη δ᾽ ���νομ᾽ ἐστὶν ἐπώνυμον (‘the Desired’); Odyssea, XIX, 409 (τῷ δ᾽ Ὀδυσεὺς ὄνομ' ἔστω ἐπώνυμον); Iliad, IX, 562 (Ἀλκυόνην καλέεσκον ἐπώνυμον, οὕνεκ᾽) cf. Homeric Hymn to Apollo, 372-373; Hesiodus, Theogony, 144 (Κύκλωπες δ᾽ ὄνομ᾽ ἦσαν ἐπώνυμοι, οὕνεκα), Theogony, 282 (τῷ μὲν ἐπώνυμον ἦεν [Χρυσάωρ], ὅτ᾽). On the metaphorical quality of Greek proper names which, by way of etymology, evoke the identity of the bearer, see Calame 1995, p. 183-185. [34]cf. Hesiodus, Opera et Dies, 572 and [Sc.] 292; see also Iliad, XIV, 114. Cf. also Catalogue of Women, fr. 2-7 and 234. [35]Hecataeus, F15; Athenaeus, II 35AB. [36]Interestingly, Hesiod (Opera et Dies, 571-572) in two successive verses connects the words φυτά (plants) and οἰνέων (vineyards). [37]This observation is at least partially confirmed by the use of the word οἴνη by Hesiod (Opera et Dies, 572). [38]Surprisingly, these early occurrences of the term Έλληνες in Hecataeus to designate the Greeks as a national unit have been, to the best of my knowledge, largely ignored. The word also figures in the genitive case in Hecataeus’ proem (see above). In fact, Hecataeus – and possibly the early Greek prose-writers – could be seen as the missing link in the dissemination of this ethnical term, which becomes commonplace in the fifth-century (presumably, after the Persian wars). In archaic poetry, the usual term is Πανέλληνες rather than ῾Έλληνες (cf. Hesiodus, Opera et Dies, 526-8; fr. 130 Merkelbach-West; Archilochus, fr. 54 Diehl). Indeed, the earlier record of the term Hellenes in the wider meaning (to indicate a collective national identity) appears in writing for the first time – according to Pausanias’ citation (X, 7, 6) – in an inscription by Echembrotus, dedicated to Heracles for his victory in the Amphictyonic Games (584 BCE). According to Thucydides (I, 132), after the Greco-Persian Wars, an inscription was written in Delphi celebrating the victory over the Persians and calling Pausanias the leading general of the ‘Hellenes’ (cf. Hall 2003, p. 125-154). Now, this reference to language as a common ethnical linkage between the Greeks of the past and the present by Hecataeus is highly significant and predates the celebrated definition of ‘hellenicity’ (to hellenikon) by Herodotus at VIII, 144, where a common language is mentioned as one of the constituent elements of Greek identity. [39]On the distinction between the often confused Pherecydes of Athens and Pherecydes of Syros, cf. Fowler 1999; Pamias 2005. On Pherecydes of Athens’ genealogical work, the mythological content of his writings, and the stylistic and narrative character of his prose, see the edition Dolcetti 2004, p. 16-33; also Fowler 2013, p. 706-715. [40]Pythian IV, 75. [41]Pherecydes of Athens (F105) Scholia at Pindar, Pythian IV, 133a. [42]Transl. by Fowler 2006, p. 39. [43]For a linguistic analysis of this fragment and its enunciative circumstances, see Fowler’s 2006 instructive examination of Jason’s account by Pherecydes and other sources. Some of his insightful remarks are reproduced in my own analysis. For further references, see Fowler’s 2013 ad locum commentary of this fragment, p. 723-724. [44]Cf. Farnell 1930-1932, II, p. 147. [45]Later Apollodoros (I, 8-11) building up on Pherecydes’ account said Jason lost his sandal when he tried to ford the river in its winter spate. [46]Cf. Pindar, Pythian IV, 155-170. Earlier poetic accounts (Hesiod, Theogony, 994 and Mimnermus, fr. 11.3) simply allude to Pelias’ vengeful and evil scheme but offer no explicit motivation. [47]In Homer, Hera helps the Argo past the Planktai (Odyssea, XII, 69 f.) and, in Pindar, she inspires the Argonauts with a passion for their ship. It is only here that we hear about Hera’s vengeful design against Pelias. The reason behind Hera’s spite against Pelias is recounted by Apollonius (Argonautica, I, 13-14), who probably drew it from Pherercydes. The reason was that Pelias had paid homage to Poseidon and the other gods, but not to Hera. [48]For an analysis of Pythian IV, see the detailed monograph by Segal 1986. The sequential chronological arrangement of events in Pindar’s version is often broken up or altered for dramatic effect. On the encounter between Jason and Pelias in Pindar’s account, see Robbins 1975; Carey 1980; Schubert 2004, who offer reviews of earlier discussions and references. As to the connection between Pindar and Pherecydes’ account it is unclear whether one or the other drew on his contemporary’s work. The differences between their accounts seem to suggest that both authors elaborated on a pre-existing source rather than derived from each other’s work. Indeed, the only formal similarity between both accounts is the reference to the oracle, possibly a standard motif in the saga. The details of the narrative vary substantially: in Pindar’s version Jason arrives alone in the market-place while Pherecydes arrives in the midst of a crowd on occasion of a sacrifice; Pherecydes narrates the search for the Golden Fleece as a self-imposed task, while Pindar mentions Pelias’ dream and his cunning plot (cf. Farnell 1930-1932, II, p. 144-148; Hurst 1983, p. 157 f.; Segal 1986, p. 50-51). [49]Cf. Fowler 2006. [50]See Calame 1995; Fowler 2006. [51]Cf. Pherecydes of Athens F146; Hecataeus, F26 (Geryon) 27; F138 (virgin sacrifice to Lemnian goddess); F305 (shrine of Leto in Boutoi); Herodotus, II, 91 (festival in honour of Perseus at Chemmis); II, 156 (etiology of the floating island of Chemmis); II, 171 (the Thesmophoria). [52]Cf. Schibli 1990 fr. 1, 2, 9, 10, 11, 12 for testimonia attributing the first prose narrative to Pherecydes. Diogenes Laertius (I, 1) includes him among the sages of Ancient Greece. On eastern influences on Pherecydes and other early Greek intellectuals, see West 1971, p. 174-175. As to the circulation of Pherecydes’ text, scholars tend to believe it should be understood as a kind of script (συγγραφή) that would aid the public performance (ἐπιδείξις) of its content in relatively restricted circles (cf. Granger 2007, p. 425-428; Kahn 2003, p. 152). [53]See Granger 2007. [54]Schibli 1990, p. 54-55. [55]On the aetiological significance of this fragment, see the detailed discussion in Schibli 1990, p. 61-69; on the anakalupteria, see Llewellyn-Jones 2003, p. 27-30. [56]Cf. Hartog 1988, p. 276, 315; Nagy 1987; Thomas 2000, p. 267; Boedeker 2002, p. 108. Marincola 2006, p. 21-22; Said 2007, p. 83. Lloyd 1992, p. 46-52; de Jong 2012. [57]Cf. Lloyd 1992, p. 46-52. Lloyd suggests that Herodotus’ variant version may have been already in Hecataeus. For a general survey of these versions, see Austin 1995. [58]Herodotus, II, 116, 1. [59]Herodotus, II, 117, 1.”

Source: https://www.cairn.info/revue-dialogues-d-histoire-ancienne-2019-2-page-81.htm

Gaston J. Basile , Andrew W Mellon Fellow, is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Classics at the University of Buenos Aires. He has conducted postdoctoral research on topics related to the genesis of Greek scientific discourse, the Italian humanists’ intellectual engagement with Greek and Latin texts and, most recently, on the theory and practice of translation in the Italian Quattrocento with a special focus on scientific texts. He was visiting scholar at the Università degli Studi di Siena (2011 and 2016); postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Buenos Aires (2015-2017); Visiting Scholar at the Institut für Klassische Philologie, Humbodlt-Universität (2018); and Erasmus/Henri Crawford Fellow at the Warburg Institute, University of London (2019).

Source: http://itatti.harvard.edu/people/gaston-javier-basile

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

WAIT!!!!!??????!!!!?????

「ミュトス」 was “mythos” this ENTIRE TIME????

#feels#ff16#jj: huh logos like mythos and logos?#lol wonder what myutosu is a reference of#also jj scrolling through tumblr#why they be calling him mythos#2 braincells weakly rub together for a lethargic pop of static electricity#omg is myutos mythos?#this is finding out lancer is cu!chulainn all over again

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

«En efecto, aquellos dioses se habían vuelto tan personales, tan individuales y tan humanos, que únicamente una amplia libertad en la interpretación alegórica podía sustentar los ídolos sobre sus pedestales. Sin embargo, una vez eliminados los dioses, aún persistió ese carácter moral o sacro inherente a la misma estructura del mundo, esto es, aquel sistema de dominios dentro del cual los dioses habían emergido y se habían desarrollado hasta ser desbancados y perecer. El material del mundo, la physis repartida en esos dominios, era también, como ahora veremos, una concepción de estirpe mítica. Dicho de otra manera: cuando Anaximandro pensó que se enfrentaba de cerca con la naturaleza no era simplemente el mundo exterior que se nos presenta a través de los sentidos, sino una representación del orden del mundo, de hecho más primitiva que los mismos dioses. Esa representación tenía, además, un carácter mágico, pues la filosofía la tomó de la religión, no la dedujo, de manera independiente, de la observación del mundo y de los procesos naturales».

Francis M. Confort: De la religión a la filosofía. Editorial Ariel, pág. 60. Barcelona, 1984.

TGO

@bocadosdefilosofia

@dies-irae-1

#francis m.confort#comfort#de la religión a la filosofía#religión#filosofía#filosofía griega#origen de la filosofía#physis#naturaleza#paso del mito al logos#lôgos#logos#λóγος#mito#mythos#Anaximadro#magia#observación#observación del mundo#dioses#procesos naturales#antigua grecia#época antigua#teo gómez otero#representación#orden#mundo#representación del orden del mundo#mundo exterior#sentidos

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Entenda o conceito de Mythos na Filosofia

O conceito de “mythos” remonta à Grécia Antiga e desempenha um papel fundamental na compreensão da forma como as culturas interpretam o mundo e articulam suas narrativas. “Mythos” originalmente referia-se a um tipo de discurso ou relato, frequentemente contrastado com “logos”, que significava razão ou lógica. No entanto, ao longo do tempo, o conceito de mythos evoluiu e adquiriu uma profundidade…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

(via "Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah'nagl fhtagn" Tank Top for Sale by obstinator)

#findyourthing#redbubble#cthulhu#cthul#lovecraft#lovecrafian#yog-sothoth#call of cthulhu#nyarlathotep#rpg#logo#cthulhu mythos

0 notes

Text

Meditation Mondays: Is “Spiritual” Becoming More Than Watered Down “Religious”?

I used to think that when someone would say that they were “spiritual,” they were saying that they used to be “religious” but no longer practice the faith they were raised in. Generally, they’re not anti-religion, but they reject organized religion. In the non-believing community some feel it’s similar to someone saying that they’re agnostic because they’re not ready to say that they’re fully…

View On WordPress

#atheism#Brian Greene#Cosmology#faith#in bad faith#Karen Armstrong#Logos and Mythos#meditation mondays#Monday Meditation#mythology#Rainn Wilson#religion#spirituality#the meaning of life

0 notes

Photo

Live, Die, Repeat :: Brahma, Shiva, Vishnu: What else is there to do?Spiritually, physically, chemically, biologically, psychologically...Spiritually.....physically........Spiritually.............? What is Eternal Recurrance if it's not the repetition of the whole, and Reincarnation, of its parts, and rebirth, of its spatio-temporal quanta? #edgeoftomorrow #emilyblunt #differencefeminism #egalitarianfeminism #paralogical #gestalt #artwork #digitalart #procreate #spirituality #philosophy #physics #chemistry #biology #neuroscience #psychology #logos #mythos #quantummechanics #paralogic #nonduality #eternalrecurrence #reincarnation #rebirth (at Nallur Shiva Temple) https://www.instagram.com/p/CndfImGPd0N/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#edgeoftomorrow#emilyblunt#differencefeminism#egalitarianfeminism#paralogical#gestalt#artwork#digitalart#procreate#spirituality#philosophy#physics#chemistry#biology#neuroscience#psychology#logos#mythos#quantummechanics#paralogic#nonduality#eternalrecurrence#reincarnation#rebirth

0 notes

Note

Just added another fic idea that I had a while ago but forgot to write down, thank you ttrpg planning for reminding me

If you get this, answer with three random facts about yourself and send it to the last seven blogs in your notifs! anon or not, doesn't matter, lets get to know the person behind the blog <3

Hi, wasn't expecting this, but cool!

I'm pb-and-jammothy, I'll probably answer to any variation of that pseudonym, except for Jim, and quite a few unrelated nicknames, here are some fun facts about me:

I'm British American, but in a kinda weird way, often this can be seen in my relatively shallow understanding about British or American things, and me using British and American spelling (though I tend to stick to one spelling of a word, it may just be an American spelling right next to a British one).

I really like cooking! I'm rather a picky eater for sensory reasons, and I'm really not a fan of trying new foods, so I'm rather proud of my abilities in the kitchen. Learning how to cook vegetables in a way where I actually enjoy them is an Absolute Game Changer whooo boy. My goal this year (which I've been achieving - 2 I've tried and been successful with and a handful ready to try next) is to learn new recipes for things I can make regularly.

I have 3 notes for fanfic ideas for a combined total of just under 14k words, with the separation being by fandom. I want to make progress in turning them from rambles about ideas into actual fics, but most of them are geared towards multi-chapter long-fics, which I've tried writing over the years, but haven't finished a single one, hence why my current ao3 accounts only have one shots published. Can't really work on any of them right now since I've got deadlines, but maybe this is a project for the summer (alongside reading a bunch of mythology books in prep for a Percy Jackson inspired ttrpg campaign I'm gonna run).

Uhh yeah, that's me. 😁👍

#it's ya boi jammothy#ttrpg#City of Mist#<- that's the system I'm starting with#but I'm gonna mess with it a lil to make it work#and by that I mean like thematically not mechanically#thematically the system has the players have their Logos (human side) and Mythos (myth attached to them)#the way I'm gonna use it it'll still kinda be like that#but instead of for example a player's Mythos being Little Red Riding Hood#they'll have the Mythos be their divine parent#but not in a 'they are a vessel for that god' way like the way it's set up to be like seems to imply#rather in a 'this is the genetic source of your powers' kinda way#so multiple people can have the same Mythos if they have the same divine parent#if that makes sense#idk I guess we'll see in like 8/9 months when I actually start the campaign#need to actually plot out some missions for them

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

yo yo! ttrpg trick or treat!

I mean if you're gonna come at me with this I'm never gonna turn down a chance to talk about City of Mist and its spinoffs, the game I am the most normal anyone has ever been about anything. (if I understand the rules correctly, this is Treat)

ahem.

City of Mist is an urban fantasy noir RPG heavily inspired by Netflix's Daredevil TV series. It now comes in LGBT-themed Sentai flavor (Queerz!) and Cyberpunk flavor ( :Otherscape) as well, with a High Fantasy version (Legend in the Mist) in the works! It also has some pretty great community support, just look up City of Mist Garage on DriveThruRPG!

The thing this game does that makes it special to me is that player creation and advancement is almost 100% driven by character development, and it does it better than most other RPGs that I've seen that try to offer the same.

at character creation, you choose four Themes for your character. You use these themes to determine what kind of character you're working with, and what kind of skills their life experience might have given them. It's also how you can tie in fantasy elements and give yourself literal super powers.

Once you've chosen your Themes, you answer four questions about your character for each Theme. These become your Power Tags, which you use in place of stats to make your roll modifiers, as well as your Weakness Tags, which you or the MC can invoke to give you a -1 to a roll, or to add a complication to the current scene. (this also gives you an XP point in that Theme so it's worth it to you to let this happen.)

But the other thing that comes with every Theme is a Mystery or an Identity. The idea of City of Mist is that you aren't born with powers, you Awaken to them when a Mythos - an idea, concept, or character from a story - decides to enact its will through you. Examples from the pre-made characters would be Excalibur, the wealthy socialite who became the Rift of King Arthur after she finds the Ultimate Weapon, which manifests for her as a piece of jewlery that transforms into whatever she needs in the moment. But the idea of a Mythos never fully survives contact with reality, as your character is still the person they were before - someone with a life, family, friends, goals - an identity. Another of the pre-gens is Kit, a Kitsune spirit who manifested itself fully in our world, but has disguised itself as a teenage girl after falling in love with a boy. Her affections form an identity outside of her purpose as a Mythos.

You as a player have the choice between trying to live the life you had before by creating Identities for your Logos themes - things that anchor you to your life in this world - or by pursing mysteries for your Mythos themes - finding out what your Mythos expects of you, and then deciding whether or not to do it.

Progression in this is interesting because the main story will put your characters' identities in conflict with the will of their Mythos, as well as the needs of the group as a whole. As you play, you can decide that your character is ignoring their Mystery to the point that getting answers no longer truly matters to them, or abandoning their Identity to the point that they wouldn't recognize their old self anymore. The attention to the themes you advance the plot of will grant you new powers in those themes, whereas the ones you allow to fade away will eventually be replaced by new character aspects that became important in the meantime. And it happens entirely at your discretion - the MC can't tell you to mark Crack/Fade on a Theme, they can't force you to explore your characters' personal story arc, but doing so MAKES YOUR CHARACTER GROW AND CHANGE, WHICH IS HOW YOU LEVEL UP!

I could probably write a few more paragraphs about this game if anyone cared.

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know Ify’s idea that Vic exists as a separate consciousness to either listen to or ignore was an improvisation, and thus not built into how the game’s story would go (like the modern Jumanji movies where the players are the characters only in appearance and capabilities).

But man, if it HAD BEEN intended from the beginning instead, they could have had fun with a City of Mist reskin.

Edit: For those unfamiliar, CoM is a system where a PC is divided into two facets of their identity: Mythos (the fantastical, a representation of a story they embody) and Logos (the mundane, their life as a normal person), each with their own capabilities. By giving narrative attention to one or the other, you can strengthen and improve that facet; by ignoring one in favor of the other, you can ultimately lose that facet and replace it with more of the other.

To put it into perspective: The players would be divided between their real selves and the movie characters they’ve been fused with. They can go back and forth embracing their movie selves or their real selves. If they chose their real selves more, they might lose aspects of their movie selves until they’re entirely mundane; if they gave more attention to their movie selves, they could lose their real selves and fully become the movie character.

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

South of Midnight | Official Gameplay Trailer

South of Midnight will launch for Xbox Series and PC (Steam, Microsoft Store) in 2025. It will also be available via Xbox Game Pass.

Title Logo

Key visual

Screenshots

Overview

About

From the creators of Contrast and We Happy Few, South of Midnight is a spellbinding third-person action adventure game set in the American Deep South.

As Hazel, you will explore the mythos and encounter creatures of Southern folklore in a macabre and fantastical world. When disaster strikes her hometown, Hazel is called to become a Weaver: a magical mender of broken bonds and spirits. Imbued with these new abilities, Hazel will confront and subdue dangerous creatures, untangle the webs of her own family’s shared past and -if she’s lucky – find her way to a place that feels like home.

Key Features

A Dark Modern Folktale – When a hurricane rips through Prospero, Hazel is pulled into a Southern Gothic world where reality and fantasy are interwoven, and ancient creatures from folklore emerge. In this coming-of-age adventure, Hazel journeys forth to rescue her mother and delves into a haunting web of folklore and family secrets, untangling her own identity.

Confront Mythical Creatures – Wield an ancient power to restore creatures and uncover the traumas that consume them. Cast weaving magic to fight destructive Haints, explore the diverse regions of the South, and reweave the tears in the Grand Tapestry.

Haunting Beauty of the Gothic South – Discover the lush, decayed county of Prospero and its locals. Experience a crafted visual style, touching storytelling, and immersive music inspired by the complex and rich history of the South.

#South of Midnight#Compulsion Games#Xbox Game Studios#video game#Xbox Series#Xbox Series X#Xbox Series S#PC#Steam#Microsoft Store#Xbox Games Showcase#Xbox Games Showcase 2024#long post

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Early Greek prose inquiry (historia) and mythical tradition-I

“The Early Greek Prose-writing Tradition: Bridging the Myth-History Divide

Gaston Javier Basile

Dans Dialogues d'histoire ancienne 2019/2 (45/2), pages 81 à 112

The so-called move ‘vom Mythos zum Logos’ as well as the myth-history divide have been recurrently revisited in the last decades. The Greek notions of μῦθος, λόγος and ἱστορία have been reassessed. [1] So was the anachronistic compartmentalization of texts in view of the later development of specific institutionalized ‘genres’ or the labelling of texts in terms of contemporary areas of knowledge which were foreign to the intellectual milieu where they first appeared. This paper aims to advance the de-construction of such hermeneutical constructs – often expressed as polarities – by examining some of the methodological and linguistic procedures used by the early Greek prose-writers (6-5th century BCE) to engage with the mythical tradition. Rather than as a categorical distinction, the interface between mythos and logos will be explored in terms of the inception of new discursive prose genres in Archaic Greece and the deployment of novel linguistic procedures.

The sixth century BCE saw the emergence of a new breed of Greek intellectuals in Ionia who, often abandoning verse for prose and adopting a critical stance towards mythology and poetry, gradually began to step beyond the boundaries of the so-called spatium mythicum. They inaugurated a form of prose writing, largely of a narrative or descriptive type, which was based on the first-hand record of experience or some form of source analysis. Though scholars have grouped them by different criteria and given them assorted names (polymaths, logographoi, histores, etc.), these intellectuals can all be said to have produced some form of prose-inquiry (ἱστορίη). These prose narratives ranged from local traditions, popular tales, mythological rationalizations, genealogies, accounts of foreign travel and people, to the kind of discourse about the human past we now narrowly count as “histories”. Regrettably, with the exception of Herodotus’ Histories, an exceptional work which is often regarded as the epigone of the Ionian prose-writing tradition, the works attributed to the logographers have only survived in the form of fragments and testimonies preserved by Alexandrian and later scholars.

Whatever the specific subject matter of these early texts, they can all be said to have produced some kind of ἱστορίη (inquiry) which departed from, but also engaged with and was often critical of, the standard mythical tradition. Hence the term historia does not designate a specific genre dealing with the human past but rather a novel cognitive category and discursive form. It designates an individual, comprehensive and critical mode of inquiry which involved a first-hand gathering and record of experience and source examination. Additionally, this inquiry adopted a new form of discourse: expository texts, largely narrative or descriptive, written in prose. Under this description, the standard myth-history divide appears at best immaterial, if not altogether flawed. Indeed, far from steering clear of myth, the Gods and archaic legends, these early Greek prose writings often actively engaged with the mythical tradition. It is the purpose of this paper to draw on the category of historia in order to sketch out some of the methodological and linguistic features of these early texts. Through a selection of fragments or passages – from Hecataeus of Miletus, Pherecydes of Athens, Pherecydes of Syros to Herodotus of Halicarnassus’ History (Book II) – the paper explores the inception of a number of commentarial and exegetical procedures ranging from straightforward etymological observations to more complex explanatory or critical operations on the traditional material.

I- Mapping the province of early Greek historia: some methodological remarks

As has been well established by classical scholars, historia is a misnomer. Though the Greek term ἱστορίη – as used by Herodotus in the proem to his groundbreaking work – was soon associated with a form of inquiry and record of the human past, the early (and, incidentally, relatively few) occurrences of the word in the Greek classical world indicate otherwise. The now regular meaning of the word historia as an inquiry into the past appears to be in fifth-century Greece a derivative one, or perhaps even a novel and more technical use inaugurated by Herodotus himself. Scholars have insisted on the meaning of the term ἱστορία in general as an “intellectual activity” and, in a more technical sense, chiefly as first used by Herodotus, as the record of the human past. In fact, early and classical uses of the lexical family of ἵστωρ and its cognates – ἱστορέω, ἱστορία – mainly refer to some unspecified kind or act of knowing in general or to the act of acquiring, recording or reporting such knowledge. In this sense, the term has been frequently rendered after Herodotus’ inaugural text as ‘inquiry’ or ‘investigation’. [2]

The notion of historia is seen as embedded in a “pre-disciplinary” world where the boundaries between what later became separate forms of knowledge were fuzzy or ill-defined. At any rate, ἱστορία (ἱστορίη in the Ionian dialect) is generally taken to indicate an active form of learning (“to learn by inquiry”). There have been attempts at pinning down the scope of ἱστορία both in terms of the precise cognitive operations involved (seeing, hearing, questioning, inquiring, adjudicating, etc.) as well as the particular field of inquiry (ethnographical, geographical, historical, etc.). However, scholars tend to regard it as an umbrella term designating a complex intellectual activity spanning the Ionian science, the works of the early Ionian prose-writers, the medical teachings, etc. [3] As more fully illustrated in Herodotus’ work, historia is best understood as a cognitive category entailing a number of heuristic operations – ὄψις, ἀκοή, γνώμη, ἱστορίη (in the narrow sense of questioning the informants) which are not often easy to disentangle or rank. [4]

Aristotle represents both a landmark and a turning-point in the semantic development of the word historia. Even if the use Aristotle makes of this term in his encyclopedic treatises is far from consistent, ranging from narrative or ‘story’ in general, to something close to our modern notion of ‘history’, to ‘inquiry’ or, more precisely, the preliminary stages of an inquiry, Aristotle provides a key to understanding the more technical side of historia as a modus cognoscendi. [5] Following Aristotle’s categorization and revisiting earlier uses of the word, the scope of historia comes more clearly into focus. In this paper historia is understood as a cognitive category and as a discursive form. It designates an individual, comprehensive and active mode of inquiry bearing on empirical matters or involving a first-hand gathering and record of experience. Additionally, this inquiry adopted a new form of discourse: expository texts, largely narrative or descriptive, written in prose. More specifically, the term historia will be used in this paper to characterize the production of a group of intellectuals from Ionia (or epigones of such Ionian tradition) who inaugurated a form of inquiry and discourse on a wide range of topics – ranging from mythography, genealogy, geography and ethnography to history proper – which departed from (and was often critical of) traditional myths.

The term ‘prose’ itself is problematic and deserves a closer examination. While there are earlier records of public uses of prose in Greece through the eight and seventh century [6] in the form of graffiti, law codes and stone inscriptions, the sixth-century witnessed an increasingly widespread use of prose, notably in the Ionian milieu, as a medium to compose and disseminate new forms of knowledge and intellectual inquiries. This new use of prose was not merely aphoristic – as the private record of graffiti in the public space – or apodictic – as was the case with public legislation engraved in stone, but was chosen as the medium to communicate the findings of an extended process of inquiry (and, accordingly, imposed new demands on language). If this choice was not unanimous (for example, as shown by Parmenides, Xenophanes and Empedocles’ preference for metrical rendering), it was by far the medium that the logographers, irrespective of their objects of study (mythography philosophy, history, science, etc.) favored to communicate their individual historiai to a (possibly) semi-literate audience. It is highly probable that these written prose texts were the basis for some kind of attendant epideixis, possibly in the form of public reading or lectures in small circles, but they may have also served as records for private use by the author himself or his disciples and acolytes. This paper will examine a number of formal patterns of this expository prose (or ‘technical’ prose) [7] by comparison with the old genre of didactic epic verse.”

Source: https://www.cairn.info/revue-dialogues-d-histoire-ancienne-2019-2-page-81.htm

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

DSB Headcanon: Cardinal just uses the Red Robin logo because. well. who's gonna stop him? Nobody even knows what RR is. Absolutely zero connections to be found there.

-🎭☕

Love the headcanon- though I will say Cardinal doesnt use any sort of moniker (the most recognizable thing being the mask, and even that wasnt part of the beta costume)

Cardianal leans HARD into the whole mythos of the early day Batclan, where Batman's very existance was a very hot topic and a silly ghost story to anyone outside of Gotham.

At this rate the general opinion is either, know/know someone who met Cardinal, or with the bullshit in Gotham? Not suprised the Bat has another one hidden under his cape.

#gothamites#do believe#Cardinal is just- with the bats??#and whose gonna deny???#of course#no one#VOICES it#and others know better#see how fast#Cardinal vanishes#the moment a bat gets near#but its the same sticth w/ canon red hood#“theres some history and I aint touching THAT”#dc cardinal#fic headcanons#the drakes spoiled brat#sunny asks#tim drake#trash tim au#ty for the ask!!#batfamily

40 notes

·

View notes

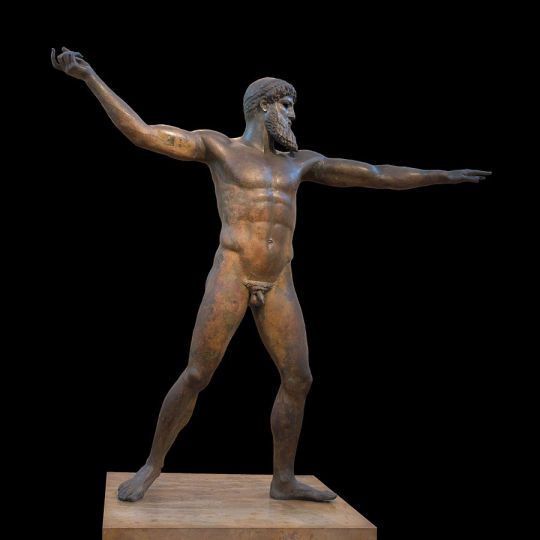

Photo

Logos Yearns for Mythos

224 notes

·

View notes

Text

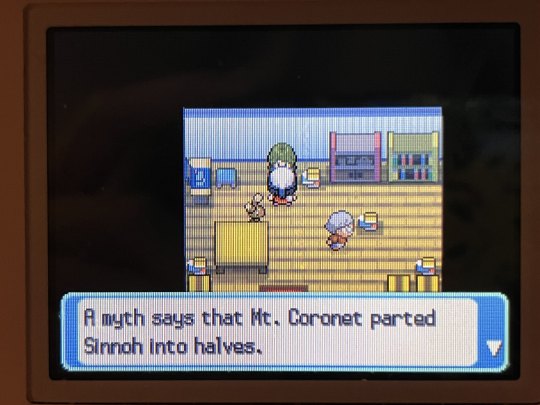

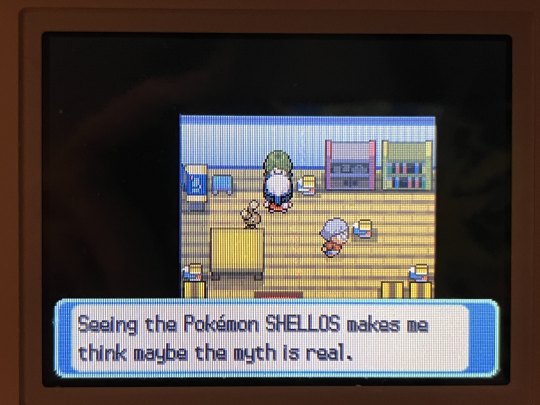

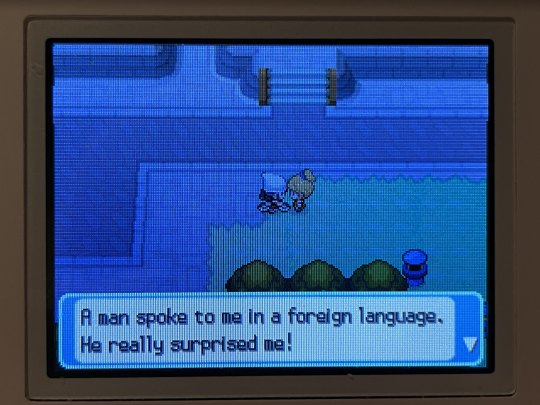

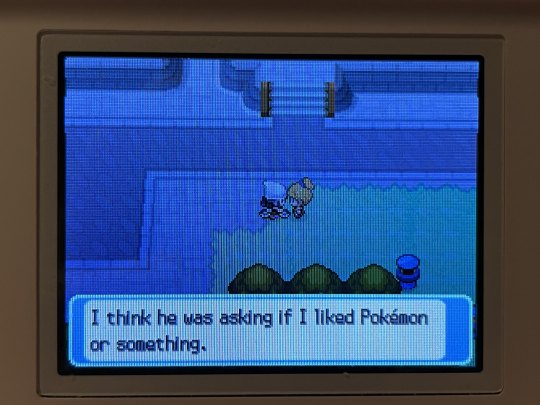

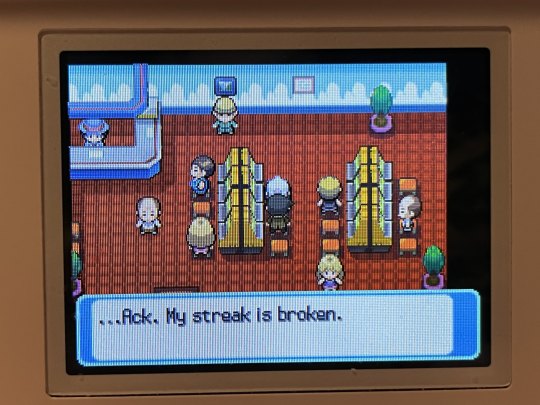

okay i just talked to every NPC in veilstone because it's been a long time and man sinnoh's NPCs are peak, at least out of the 2D games i feel like they provide the most humor and the most random lore tidbits and stuff. i love this region. i'm going to talk about it

first off sinnoh is full of little things like this. random dialogue/flavor text that ties back to the mythos of the region. i love how widespread the sinnoh myths are

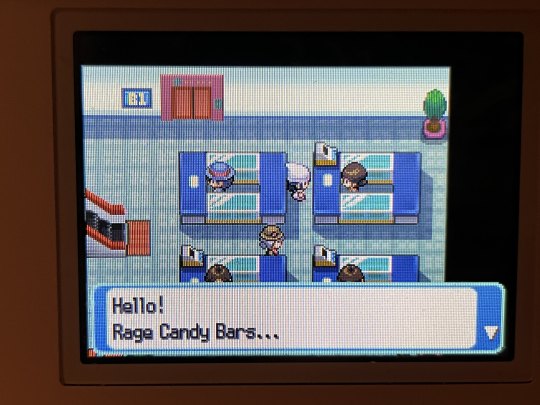

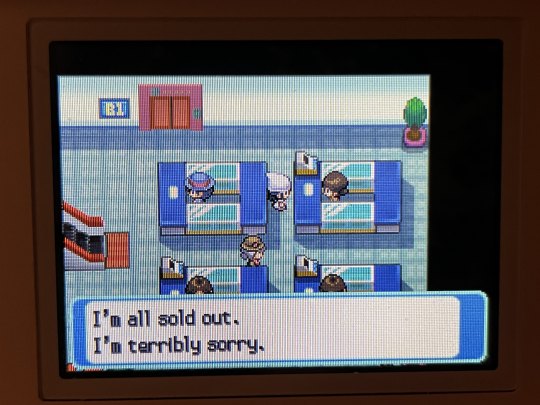

i'm also obsessed with when there's two NPCs that link together like this. you talk to one and you move on and then you talk to another and you're like oh! lmao. by the way the rage candy bars being here is cool because sinnoh is canonically connected to johto through the sinjoh ruins and the rage candy bars are from johto, which means they're imported and sold here. in general i'm obsessed with the locations in pokemon that have special treats associated with them, like the pewter crunchies of pewter city in kanto, or the lava cookies from lavaridge in hoenn. iconic

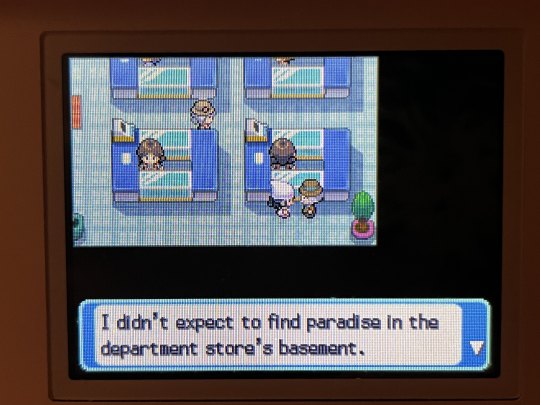

btw don't worry lady literally everyone sucks at making poffins. unless you have four players it's pretty much impossible to make poffins that are better than the storebought ones. good luck getting four people with rare berries who are good at the minigame to play with you, ESPECIALLY in 2023 jesus christ. the basement poffins are OPTIMAL

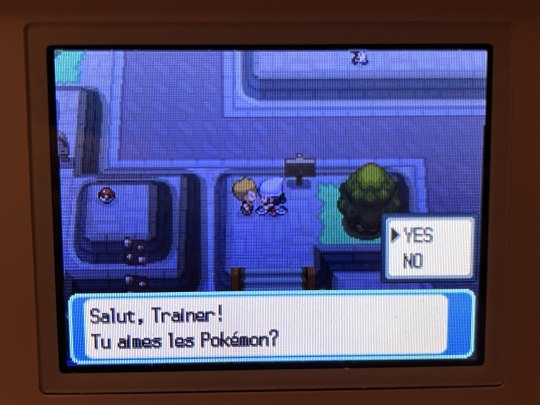

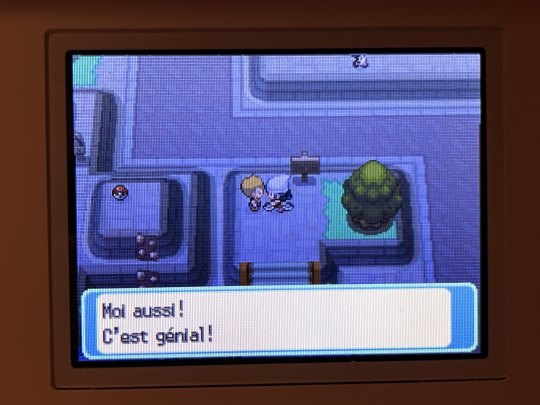

anyway in speaking of linking NPCs, these two - i wonder if the dialogue in the french version of this game is turned into english? they did that for lt. surge's french pikachu trade, the french versions of HGSS make the pikachu english instead lol. but anyway as usual it's very fascinating to me how much pokemon loves to drop foreign language in its titles, and fittingly i know a lot of people with english as their second language got interested in learning english from a young age due to wanting to play pokemon. how many kids do you think got interested in french because of dialogue like this. the girl even implies what the meaning of his words is

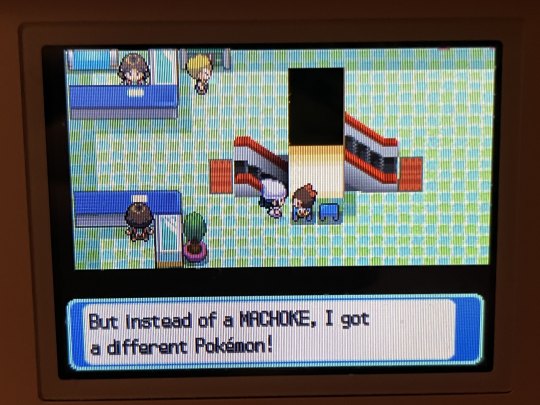

veilstone isn't short on game hints either, useless to me now as an adult longterm pokemon player who knows all this stuff already but still really cool to see. if sinnoh is your first time playing pokemon, those hints on trade evos and stuff are always appreciated.

of course, funny dialogue too that got a wheeze out of my nose, not uncommon for pokemon NPC dialogue SDKFSFDK some of this shit takes me so offguard it's like extra funny

like GIRL ISN'T THAT WHAT A PARASOL IS FOR????

edit: my DUMB ASS (lighthearted) has been reminded that parasols are for the sun and are NOT an umbrella equivalent. okay she makes more sense now LOOL

also LOOKER JUSTIFYING HIS GAMBLING :skull emoji: this shit is taking me out. see this is useful because it's like oh galactic is really all over this city huh. not only their massive building but they have their logo in the fucking slot machines, they probably have some amount of ownership over this place like team rocket did over the celadon game corner. but also it's funny because SDFSDFK

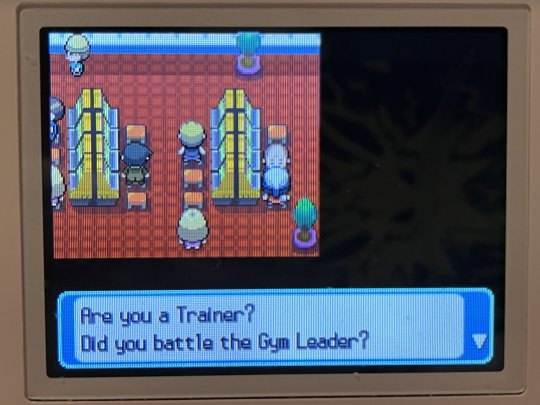

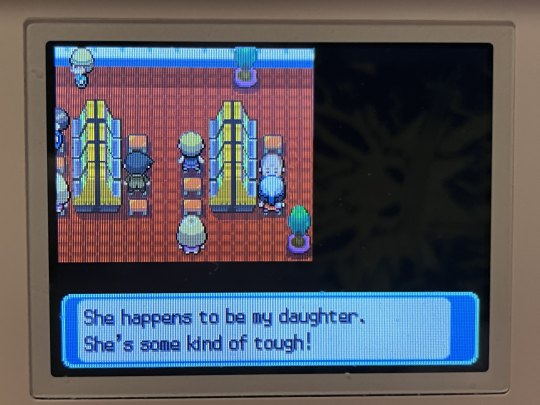

OH AND MAYLENE'S DAD IS JUST... HERE? generic NPC. generic sprite. no name. he's just here. maylene's dad. you know, one of the gym leaders. help girl

anyways i'm aware i basically just posted most of the dialogue in veilstone city verbatim but I JUST THINK IT'S INTERESTING! I MISS WHEN POKEMON GAMES WERE FULL OF DIALOGUE LIKE THIS AHHHH i have more to say about the galactic lore but i'm running out of image space and i need to use the bathroom and get some food so i'll post about that a little later

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

urge to write ffxvi time travel fic,,,

ANYWAYS, here are the fic ideas that have been circling my mind.

Barnabas and Clive (maybe Jill) travel back in time, probably to Phoenix Gate.

Barnabas destroys Sanbreque’s army and just takes Clive to Waloed. Everything is thrown into disarray. Barnabas looks like an absolute creep of a king (always was, but still.)

Nobody has any idea what Clive and Barnabas’ dynamic is supposed to be. Ultima is incredibly angry but Clive has him blocked, so. Cid has no idea why this kid with extreme trust issues trusts him so much.

Clive is a terrible liar and the revelation that he’s the second Dominant of Fire basically blows everything up. He’s even worse at hiding the fact that he’s Mythos, since he’s used to fighting with all of the Eikon’s powers.

Clive somehow gets away with using Mythos’ powers against Barnabas so his family just believes that Clive primed as Ifrit and Barnabas just took him away to gain another Dominant in his ranks. Barnabas finds this vaguely amusing. It’s not very funny to Joshua or Elwin.

If Jill has traveled back in time, she and Clive have a cute teenage romance where they make Barnabas look even more like a creep and put flowers into each others’ hair.

Clive travels back in time to Phoenix Gate as his 33 year old self and basically cuts through Sanbreque, saving his past self, younger brother, and father.

Annabella mysteriously disappears under the chaos. Joshua registers older Clive as his brother and Elwin claims him as his younger cousin.

Essentially, older Clive becomes a mysterious new Rosfield and well-known as the second Dominant of Fire. In reality, older Clive, now going by Ifrit or some other alias has magically become perfect Mythos/ Logos/ vessel to account for younger Clive, meaning he’s no longer Ifrit’s dominant, but purely balanced in terms of Eikons.

In one world, Clive spends thirteen years trying to find and kill the second Dominant of Fire. In this world, Clive looks up to his older brother/ self as a protector and a powerful Dominant. Clive is trained by Ifrit and when he first primes, it’s a moment of pride awash with exhaustion, not pain and trauma.

Joshua loves his two older brothers and never has to grow up raised under a cult that worships him, never has to distance himself or put the weight of the world in his chest.

Ifrit starts destroying Mothercrystals using Ramuh after Cid defects. It would be funny, if it didn’t completely confound and stress Cid out.

Barnabas starts taking extreme interest in Rosaria. It’s not a good thing.

#ffxvi#ff16#my writing#my fics#clive rosfield#cidolfus telamon#barnabas tharmr#elwin rosfield#joshua rosfield#time travel#not relevant but#in my head benedikta is like 7 yrs older than clive#so cid defects when clive is around 15#clive has the worst trust issues#also while trusting everyone

31 notes

·

View notes