#myth of disenchantment

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Nor has [belief in the paranormal] vanished with compulsory mass education. While there is a connection between education and specific paranormal beliefs, there is little correlation between level of education and having paranormal beliefs as such. For instance, Bader, Mencken, and Baker conclude that college graduates are less likely to believe in UFOs but more likely to believe in psychics. Other surveys targeting the issue specifically have also suggested that “higher education fuels [a] stronger belief in ghosts.” At the very least, college seniors are more likely to be open to the possibility of ghosts and psychical powers than their less educated peers. A related point worth underscoring is that sociological evidence suggests that self-identified magicians and witches are generally better educated than average and more likely to hold a college degree. Hence, it would be a mistake to assume that education necessarily leads toward disenchantment.

–Jason Ā. Josephson-Storm, The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The idea of it..."

This is obviously a reference to the ol' argument:

"The Jedi weren't bad but the Jedi Order as an institution needed to go."

So as a quick reminder I thought I'd point out:

1) George Lucas describes the Jedi's eradication as a sad thing, not something sad-but-necessary:

"[The] Jedi getting killed through the Order 66 of the clones is just done as one of those kind of inevitable pay offs in terms of getting rid of everybody, the Emperor is getting rid of all his enemies, but there’s a certain inevitability of it all and a sadness to it. - Revenge of the Sith, Director’s Commentary, 2005

2) Out of 770 George Lucas quotes, I've never seen him refer to the Jedi Order as "an institution" once.

He does refer to the Republic itself as an institution.

"[In The Phantom Menace one of the many storylines is] the story of a young queen who's faced with the total annihilation of a people, and how she can get a sluggish political institution to pay attention to what's going on." - Premiere, 1999

He might be referring to the Senate instead of the Republic as a whole, but the point stands: he's not talking about the Jedi.

Which tracks with what Lucas defined as Dooku's reason for leaving the Order: his disenchantment with the Republic/Senate, not the Jedi themselves.

But let's go slightly further:

The Jedi Temple was designed as a place of worship that would contrast with the corporate coldness of the Senate.

Also, the Jedi were originally designed as a more organized police force. As the script evolved, they were turned into peacekeepers, diplomats.

Mace's room was redesigned so as to not convey that the Jedi were mired in bureaucracy and protocol.

And when describing the political situation of the Prequels, Lucas doesn't blame the Jedi, but rather the corporations and Senate:

"But as often happens when wealth and power grow beyond all reasonable proportion, an evil fueled by greed arose. The massive organs of commerce mushroomed in power, the Senate became corrupt, and an ambitious named Palpatine was voted Supreme Chancellor." - Shatterpoint, Prologue, 2004

Wow, it's looking like not only is the "Jedi Order as an institution needed to go" narrative not a thing per Lucas, but

3) Lucas went out of his way to make it clear that the Jedi aren't the issue, here, the Republic/Senate is.

So how did we get this narrative?

Well, it comes from a generation of fans and Star Wars creators who were not the target audience.

You know the type. It's the kind who, when asked if they like the Prequel Trilogy, will respond that they liked...

... but not the execution.

AKA they disliked the Prequels, but then EU books and The Clone Wars came out and provided them with enough material to form a headcanon justifying why they didn't like the Jedi, despite wanting to: it's because the Jedi are meant to be disliked! Totally!

The Jedi failed as an institution is an idea that comes from authors who wanted to engage with the material (it IS Star Wars, after all) but not the narrative that George Lucas had crafted, whose work then influenced older fans who preferred the author's retconned version of the story to the original one.

The rest is history.

As Prequels producer Rick McCallum put it:

"The myth begins on paper. During preproduction, filming, and postproduction, the myth becomes visible through the work of hundreds of dedicated people. Following the film's release, the myth becomes public and the public makes it its own." - Rick McCallum, Mythmaking: Behind the Scenes of Attack of the Clones, 2002

#I find it ironic that Filoni unwittingly gave Baylan the same line repeated by 'Prequel fans' who only became fans by...#... injecting gray morality into the films and said “it was there all along! the Prequels are subversive films!”#They're not. They're films for kids. The SITUATION is more complex than in the Original Trilogy... but the morality is still good vs evil.#baylan skoll#ahsoka series#jedi order#george lucas#meta#star wars#ahsoka spoilers#ahsoka show#ahsoka#in defense of the jedi

522 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think the original Phantom of the Opera book has any sort of fairytale-like elements to it? If so, could you list some?

This ask is seven billion years old, but yes!

For one thing, the Phantom story is essentially a more specific version of the old Beauty and the Beast fairy tale - in both, a father "gives" his daughter to a terrifying monster who appears to be dangerous but turns out to love her, and she must find a way to love that monster in turn in order to keep herself safe and search for a happy ending. The Phantom story adds embellished elements, such as the heavy focus on music and the Phantom being a disfigured human instead of a cursed one, but the story is essentially the same, which means it carries over a lot of beats from the original fairy tale.

If you didn't know I'm a sucker for Aarne-Thompson-Uther, you do now, so let's go down a quick list of some of the fairy tale elements we see!

The Child Who Won't Leave Home: Lots of fairy/folktales have this element, where a child needs to leave home and make their way in the world or they will never truly grow up (which usually, in these stories, means they won't be able to be happy and/or they'll be a burden on their aging parents/community). Christine fits this trope, remaining somewhat locked in eternal childhood, focused on her memories of her father and his tales of the Angel of Music, until she is finally forced to see reality and make choices about her adult life.

The Girl as the Monster's Wife: This is a common fairy tale/folklore stock element: a beautiful young girl is given to a monster to become its bride. You see echoes of it in dragon/monster sacrifice tales, too, but the story usually uses its fairy tale themes to address real-life anxieties about women in earlier centuries having little to no control over who they married or how they were treated when they did. (And parents' fear over that for their daughters!)

The Animal Bridegroom: A subset of the Monster's Wife above, there are an absolute load of stories about young women being forced, either through trickery, blackmail, or magic, into marrying actual animals. Often, these animals can later be turned into humans through the power of her love and/or loyalty and devotion, but sometimes the moral is more about making the best of a weird situation. Obviously, the Phantom story inherits this from its Beauty and the Beast roots, even though the Phantom is no longer a literal animal.

The Dangerous Husband: The most common version of this is probably the tale of Bluebeard, but it appears in many stories and cultures (from the same anxieties as above!). In these stories, the husband is hiding a dark secret, and his innocent wife must realize he's evil and get out before it's too late or join others he has previously preyed on; in the Phantom story, Christine must realize that her "angel of music" is actually the murderous Phantom, and is in a constant state of discovering things like torture chambers and death threats until she and Raoul finally resolve the situation and escape.

Disenchantment by Kiss: In many fairy tales, the curse/transformation/evil is broken or defeated by a pure kiss from a loved one; in the Phantom story, it is Christine's kiss on his forehead (or mouth in later derivative versions) that causes him to realize that he has been behaving like a monster and end his reign of terror.

In addition to all this, there's also of course the mythology angle, which I mention a lot in reviews! Greek mythology is especially good with this - the Phantom story has heavy overtones of both the myth of Hades and Persephone, in which the god of the dead rises up from the underground to kidnap the beautiful young goddess of spring and everyone goes absolutely bonkers trying to get her back, and the myth of Eros and Psyche, in which the beautiful Psyche is forbidden from seeing her lover, who always comes to her in darkness with his face hidden, and when she breaks her promise and brings in a light to see him destroys the relationship and suffers as a result. The first has obvious parallels to Erik's kidnapping of Christine, while the second is a pretty clear comparison to the unmasking scene.

#phantom of the opera#mythology#fairy tales#anne pretends to be a real librarian#did you guys know they'll just let you learn about this stuff? for free?

113 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello, i hope you’re having a good day today :D I was wondering if you had any favorite readings on folklore/fairytales that you’d be willing to share. many thanks again for all the information you share!

hi! i don't read a ton on this topic honestly, but i thought 'pregnant fictions: childbirth and the fairy tale in early modern france' by holly tucker (2003) was fun, and 'the myth of disenchantment: magic, modernity, and the birth of the human sciences' by jason josephson-storm is a decent intro to critique of weberian 'disenchantment' theses that talks about how these ideas shaped the early disciplinary history of (among other things) folklore studies

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leila and The Wolves: Revolutionary Feminism and the Importance of Third Cinema

Image by Cinema of Women Presents

Leila and the Wolves created in 1984 by Lebanese filmmaker Heiny Srour follows the story of a young woman named Leila. Leila lives in London and can travel through different points of Middle Eastern history through the collective memory of women a part of the 20th-century Palestinian and Lebanese resistance movements. The film is framed through a radical and feminist lens and highlights the women central to the Palestinian liberation struggle, serving as a testimony to their revolutionary spirit.

Srour’s approach to the film's formal elements solidified her status as an innovative filmmaker — reflected through the film’s radical political commitments through challenging dominating structures of occupation and colonialism. The film reflects these commitments through Leila’s ability to travel through time and space. Leila’s power bridges the gap between the past and present, giving agency to the Arab women often erased in historical narratives. Srour employs Leila's ability to time travel offers a transformative approach to interconnecting various periods of a collective history — contributing to a richer and textured narrative.

At the beginning of the film, Leila is transported to the West Bank in the 1920s. While Leila is there, she witnesses a violent demonstration and the cruelty inflicted on the Palestinian people. She is shortly taken back to the present, and the brutal imagery remains etched in her memory. During a conversation with her partner, Leila questions why he exclusively selected photos of men in the exhibit showcasing the Palestinian struggle.

He responds, claiming he doesn't recall any images featuring women and that they had no role in politics back then. This scene is juxtaposed moments later when Leila is transported back to the West Bank in the 1920s, and the viewer witnesses how the women resist colonial subjugation. The women are strategic in their resistance — flinging rocks and pouring boiling water at the unsuspecting colonial officers from the balcony.

Film scholar Vivianne Saglier expands on this theme, “My argument navigates the tension between historical continuities and ruptures intrinsic to disenchantment by re-articulating the relationship between historical projects of decolonization and later decolonial feminist approaches, which materialize in Srour’s “post-Third-Worldist praxis”.

Srour’s filmmaking style in Leila and the Wolves resonates with the principles of third cinema, which disrupts conventional American narratives. As mentioned by Saglier, “Srour’s cinema of liberation experiments with myth-based historiography to establish connections between distinct epistemic worlds across time, space, and gendered groups—what Lugones calls “world-travelling,” the realization and negotiation of the plurality of epistemic worlds that enrich the construction of collectivities”

With this framework in mind, the spectator immerses themselves in the gendered collective memory of the Palestinian liberation struggle. These instances are witnessed through Leila, as she acts as the viewer's guide. The viewer can observe the women gathering to manufacture bullets out of old residue, strategically concealing weapons to bypass checkpoints, and taking up arms to resist the 1948 Deir-Yassin massacre. These acts of resistance reflect how Leila and the Wolves stand as a tribute to the revolutionary and feminist spirit of Arab women.

Leila’s ability to serve as a historical witness in combination with archive footage enables the viewer to tap into the collective memory and shared trauma of the Palestinian plight. The archive footage often shows the violence occurring on the front lines and the heartbreaking display of Palestinian refugee camps.

While Srour's methodology enhances the depth and authenticity of the story, many Arab male filmmakers during Srour's time, often fell short in this respect. Srour comments on Arab men’s films such as Borhane Alaouie´’s Kafr Kassem (1968), Youssef Chahine’s Al-Asfour/The Sparrow (1972), or Tewfiq Saleh’s Al-Makhdu‘un/The Dupes (1973) often represented women in a one-dimensional perspective—typically relegating Palestinian women into symbolic representations that mirrored patriarchal narratives such as passive beings or the docile mother identity.

Srour’s decision to integrate archive footage while displaying women’s political role in liberation struggles contrasts with this traditional narrative. This approach to storytelling not only adds a layer of historical context but underlines that the efforts and struggles of Arab women are not fictitious or symbolic representations but are grounded in historical authenticity.

In doing so, the film paints a broader picture of the Palestinian liberation struggle and illustrates its feminist principles. In a world that often erases the contribution of women’s historical efforts, Leila and the Wolves is a groundbreaking form of media that commemorates the revolutionary commitments of women at the heart of the Palestinian liberation struggle.

Heiny Srour gives us more than just a story; she presents a lesson, a memory, and a call to not forget the sacrifices made by Arab women at the forefront of the Palestinian liberation movement. Although Leila and the Wolves was released nearly 40 years ago, the depiction shown in the film reflects the material reality of Palestinians today, from having to navigate checkpoints in their own land to being displaced from their homes to live the rest of their lives in refugee camps. Srour’s approach to storytelling is a reminder that the struggles of the past continue to echo in the present, urging the viewer to reflect on the challenges Palestinians face today.

Saglier, Viviane. "Decolonization, Disenchantment, and Arab Feminist Genealogies of Worldmaking." Feminist Media Histories, vol. 8, no. 1, 200.

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Irish literature has a special place as part of the British/English-Language canon, thanks largely to Wilde-Yeats-Joyce-Beckett, but which would you say are the best works and writers of Scotland and Wales?

I will unfortunately have to pass on Wales. I don't think I've read any Welsh literature except for the Mabinogion (selections) and Dylan Thomas (anthology pieces). And Raymond Williams, I suppose: not, however, my favorite critic. Surely Dylan Thomas is the most celebrated of Welsh writers, though. And Roald Dahl, but he's a blank to me.

I'm no expert on Scotland, either, but I appear to have read a reasonable amount of Scottish literature by accident. I have nothing non-obvious to say, however. There's their celebrated Enlightenment, first of all, with David Hume's urbane and skeptical review of the limits to our knowledge and Adam Smith's humane interest in the emotional origin and economic extension of what we're morally capable of. And Charlotte Lenox, looking forward to Austen's disenchantments with her Female Quixote. Then comes the counter-Enlightenment: Robert Burns's earthy testaments in dialect that presage Romantic verse and its lyrical ballads, Walter Scott's recreation of the vanquished clan-life that invents the historical novel, and perhaps above all Thomas Carlyle's thundering proto-fascist denunciations of modernity in a prose that destroys forever all rhetorical decorum and prepares the ways for everyone from Emerson to Melville to Lawrence. Modern myths at the fin de siècle: Robert Louis Stevenson giving us Long John Silver and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Arthur Conan Doyle coming through with Sherlock Holmes. And Peter Pan, too, though I've never actually read that, either play or novel—just caught its later refractions. Who in the 20th century? David Lindsay with his cult fantasy novel A Voyage to Arcturus, favorite of Frank Lloyd Wright and Harold Bloom and Alan Moore, which bored and horrified me so much. Muriel Spark, skeptical as Hume, inventive as Stevenson: I must read more of her. I must read more of Alasdair Gray, too, but I just recently enjoyed his enviably inventive Poor Things on account of the film. (And I must read more of Scott. And something of Smollett. And Scottish Boswell's life of English Johnson. I've read as much Adam Smith as I ever want to read, however.) Finally, I was a teen in the mid-to-late '90s, so, too old for Harry Potter and his semi-Scottish creator—that was kids' stuff, I thought, and still think—I spent my adolescent time instead poring over (as I have exhaustively mentioned) Grant Morrison and (as I may not have mentioned at all) Irvine Welsh. That's all this provincial American has to tell you about Scottish literature for now.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

As myth is based on the contrast between the sacred and the profane, romance is based on a contrast between a sense of wonder and what we might call the disenchantment of ordinary life. Like the sacred, the sense of wonder imparts to anything it touches a kind of numinous otherness, which can be mysterious, fearful, and fascinating all at once.

Northrop Frye's notebooks on Romance, ed. by Michael Dolzani

#this book costs like my whole soul and a spare limb but it's everything#it's my red book#romance#mythos#the sacred feminine#profane#literary#northrop frye#romantic academia#booklr#quotes#quotations#book quote#kate bush#light academia#dark academia#fair folk#paganism#inspo#fiction and quotes

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

IME these Thoreau-dunks come alongside a desire, on the part of the dunker, to puncture American myths, to be severed from any felt obligation to its ideals, or loyalty to its project.

These are parables of disenchantment opportunistically repeated until critical virality; the actual conditions of the actual subjects of the parable are considered irrelevant from the get.

Sometimes the stories that get passed around about a subject tell you more about the ideology of the super-spreaders than they do the ostensible subject.

I hate the “Thoreau’s mom did his laundry” criticism so much, it drives me crazy.

Henry Thoreau did not go to Walden Pond because he thought it would be a fun adventure. He went into the woods because he was deeply depressed and burnt out. He was running from the horror of his brother and best friend recently dying in his arms, and the haunting memory of causing the Fairhaven Bay fire. His friend Ellery Channing literally gave him the ultimatum of either taking some time off to write and think, or else be institutionalized.

I think Thoreau’s mother saw her depressed son choosing to retreat into a small cabin in the woods, and was worried about him. Of course she did his laundry - just as Ralph Waldo Emerson probably brought him firewood and bread. These were not chores of obligation to support a “great” man, but services of love to help their deeply depressed 28yo son and friend.

And if you ask me, there’s a lesson in that - to “suck out the marrow of life” and “live deliberately,” one must also accept help offered from the people in your life who love you. There is no true transcendentalism or individualism without love and friendship behind it.

33K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Great War

Historians have long debated the cultural consequences of the Great War. What role did its memory play in interwar unbelief? One major school of thought, centred around Paul Fussell’s classic The Great War and Modern Memory, sees the war as unleashing the disenchantment of the modern age. Traumatized by the vast machine of industrialized warfare, most veterans returned home deeply skeptical of authority figures and official narratives. Fussell does not address religion in any detail, but the implications of his argument are clear: the chaos of war exposed a world devoid of divine meaning.

The historian Jonathan Vance takes issue with Fussell’s interpretation in Death So Noble, his examination of Canada’s memory of the Great War. Pointing out that Fussell rests his argument mainly on the work of elite writers and thinkers, Vance turns instead to newspapers, war memorials, lesser novels, and patriotic memoirs, and finds that many (perhaps most) ordinary Canadians could not accept a cynical, modernist critique. To say that the war had been futile and meaningless was to disparage the sacrifices made by veterans and their families, and this was intolerable. Thus, Vance argues, Canadians constructed a myth to justify the war, whereby noble soldiers fighting to defend Christianity and civilization had laid down their lives in willing sacrifice, like Christ himself.

When it comes to the question of religious doubt, the two positions are not as far apart as they might appear. Vance acknowledges that many Canadian soldiers came to view “the entire edifice of organized religion more sceptically after four years of war.” While some veterans may have found the language of soldier-as-Christ deeply satisfying, this view did not necessarily entail respect for organized churches or reverence for a providential God. The stress and horror of war also led many men to discard the norms of Christian propriety in everyday life. Vance notes too that, upon returning to Canada, a significant proportion of Methodist chaplains and probationers cut their ties to the church. Duff Crerar’s study of Canadian chaplains in the Great War, Padres in No Man’s Land, confirms a similar pattern for seminary students of all denominations who served overseas. He mentions as an example the fact that most of the students from Queen’s Theological College who enlisted chose not to return to their studies after the war. The Methodist leader S.D. Chown said:

In many minds the war shook with the violence of a moral and intellectual earthquake the foundations of Christian faith. It shattered many structures of belief in which devout people found refuge from the storms of life.

Crerar surveyed other scholars’ research on the British and Australian armies and found that only a small minority of enlisted men, perhaps as few as 10 per cent, were strongly devout Christians. A great many more, perhaps even a majority, were hostile to religion and to the chaplains, while the remainder were lukewarm or ambivalent in their feelings. From his own research, Crerar estimates similar proportions among Canadians: a small contingent of faithful Christians, a large number of “sceptics and cynics,” and a third group, the largest, which was “uncommitted and disillusioned but not entirely irreligious.” Crerar mentions the memoir of Thomas Dinesen, an unbelieving Dane who enlisted to fight alongside the Canadians. Dinesen found that many of the soldiers with whom he spoke were skeptical of organized religion but also refused to accept his brand of hard-edged atheism.

Army chaplains were aware of this widespread dearth of religious sentiment. The historian David Marshall summarizes the findings of a Baptist chaplain who interviewed a number of soldiers on their return to Canada:

Few of the soldiers expressed belief in any particular creed, and they did not express their religious beliefs in biblical language. Moreover, many claimed to hold no religion.

The chaplain attempted to put a positive spin on the situation by claiming that the soldiers nevertheless displayed Christian character through their actions. A fellow Baptist took issue with this interpretation, arguing that the chaplain was moving the goal posts. The men in question were “unbelievers,” not Christians in disguise. Apathy and sheer ignorance were also problems the churches encountered among soldiers. Presbyterian chaplains who were surveyed near war’s end complained that the men exhibited “an amazing ignorance of the Bible” and the Christian creeds. These clergymen had to confront the fact that, even before the war, many Canadian men had had only a vague and shallow relationship with the churches.

Crerar expresses the view that novels and memoirs of the interwar period overstate how cynical and disillusioned soldiers were about religion. He suggests, rather, that it was in the 1920s and ’30s, as Canadian veterans grappled with a harsh economic situation and a difficult transition back to civilian life, that their mood soured. They could not help but notice that the Kingdom of God on Earth preached by optimistic chaplains had failed to materialize, and they began to wonder if their sacrifices had really been worthwhile. Crerar suggests that during the war itself soldiers were somewhat more idealistic than they later recalled being.

It is true that there is little evidence of unbelief arising directly from the war years. Expressions of atheistic angst in letters, for example, would neither have encouraged family members at home nor made it past the censors. Canadians were frequently told, after all, that they were fighting a crusade for the survival of Christianity itself. For the purposes of this study, however, irreverence on the part of Canadian veterans in the interwar period is worth noting. Even if they came late to their doubts, the fact that they began expressing them in the 1920s tells us something about the mood of the time.

We find such skepticism in the work of a few Canadian authors who were themselves combat veterans. Peregrine Acland had fought and been badly wounded at the Battle of the Somme. In his semi-autobiographical novel All Else Is Folly, published in 1929, the main character finds himself alone with a kindly Anglican priest who invites him to take Communion with him:

Falcon was embarrassed. He had been brought up a sound Anglican, but he had long since lost his belief in orthodox Christianity. He had, now, no religion … except a love for his fellow man. And his being here, as a soldier, was the absolute negation of that. He couldn’t, however, explain all these things to the Canon.

For Acland, war destroyed not only faith but whatever secularized ethics remained in its wake.

The canon in Acland’s novel is likely a fictionalized version of Canon Frederick George Scott, who earned a good reputation among Canadian soldiers for his tireless efforts on behalf of the enlisted men. James H. Pedley’s 1927 memoir, Only This, mentions Scott directly with great respect. But he makes it clear that in his opinion Scott was an exception when it came to chaplains. Before Pedley met him he assumed the man was simply another “highly successful fakir,” a term used contemptuously. Pedley’s feelings went beyond a general anti-clericalism, extending, as with Acland, to theology itself. Later in the book, Pedley mulls over one of the horrible injustices of war and asks:

Is there a God? … Must this kind of rough-and-ready justice be ascribed to all-seeing Deity, or to sportive chance? Who will dare to say?

Canadian veteran George Godwin’s autobiographical 1930 war novel Why Stay We Here? concludes with an affirmation of the notion of soldier-as-Christ and holds out hope for an eventual resurrection. The body of the book conveys a much more skeptical tone, however. As the main character, Stephen, and his comrade Piers wander over a battlefield where “sixty thousand Frenchmen” were killed earlier in the war, they reflect bitterly on faith. Piers concludes:

Well, personally, I’ve given up speculating about that sort of thing. I don’t know, and I don’t much care whether there’s a God or no. This place is enough evidence that He returns the compliment. If He exists at all, then He must be an impersonal God who doesn’t care a hoot about mankind.

Stephen concurs: “Exactly what I feel lately."

The best-known novel about the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) is Charles Yale Harrison’s Generals Die in Bed, first serialized in 1928 and then published in book form in 1930. Harrison served in the CEF from 1916 to 1918. Of Jewish descent, he seems to have already been an unbeliever before the war. He was born in Philadelphia and spent much of his life in the United States, so his work may not be entirely representative of the disenchanted Canadian. He was, however, observant of his Canadian comrades, and the book illustrates the critique of religion that was common in anti-war literature of the period.

Generals Die in Bed opens with a scene of new recruits returning to their Montreal barracks after visiting assorted brothels. Anderson, a middle-aged Methodist lay preacher from northern Ontario, sits on a bunk reading his Bible. He attempts to tell the younger men about the sinfulness of their actions but is shouted down. “Shut up, sky pilot!” yells one drunken teenager. The narrator’s own attitude to Anderson is not clear at first. As the book progresses, however, we see that Anderson represents something larger than himself: the old-fashioned effort to justify the war in terms of Victorian evangelical piety. The character also tries to predict the war’s end using chronological calculations drawn from biblical prophecy. In response, his younger comrades heap mockery and abuse on him. When Anderson tells the young men they should not curse, the narrator muses bitterly:

To think we could propitiate a senseless god by abstaining from cursing! What god is there as mighty as the fury of a bombardment? … How will we ever be able to go back to peaceful ways and hear pallid preachers whimper of their puny little gods who can only torment sinners with sulphur, we who have seen a hell that no god, however cruel, would fashion for his most deadly enemies? Yes, all of us have prayed during the manic frenzy of a bombardment. Who can live through the terror-laden minutes of drumfire and not feel his reason slipping, his manhood dissolving?

The book’s predominant view is that religion is for irrational women and feminized men who have lost their wits. Harrison goes on to condemn the religiosity of those supporting the war in Canada:

Back home they are praying too – praying for victory – and that means we must lie here and rot and tremble forever.

Generals Die in Bed and All Else Is Folly are often cited as the most original and realistic of Canada’s Great War novels, alongside a third text, God’s Sparrows. Written by Philip Child and published in 1937, the book was based on Child’s own experience of the war. The protagonist, Dan Thatcher, is a relatively steady sort who maintains his faith throughout the novel, but much of the text’s emotional energy centres on two other characters, the mystic Dolughoff and Dan’s philosophical cousin Quentin. Dolughoff is convinced that he has a message from God that will bring an end to the war. Overcome by the horror of battle, he runs out into no-man’s-land and in God’s name orders both sides to stop. When they ignore him and continue to slaughter one another, Dolughoff shoots himself in the head, terrified of what the “indifferent and empty” sky implies. Quentin, on the other hand, is a sensitive character who doubts that he has a soul or that any providential God is watching. In one extended sequence Dan dreams of a dead Quentin wandering a bureaucratic, mechanized afterlife in search of a “Commander-in-Chief” whom he never finds.

It seems unlikely that these veteran authors who expressed doubt or unbelief were simply offering a cynical audience a position they did not personally hold. It is not hard to imagine that other CEF soldiers suffered a personal crisis like that of the Victoria Cross recipient Cyril Martin, a Baptist who began to doubt God’s goodness while serving in France. Seeing children with missing limbs deeply disturbed him. It “really got to me,” he later recalled.

I thought, if God is all powerful, why doesn’t he stop this war? And it was quite a while afterwards before I got [my faith] back.

\Martin returned to Christian belief by reinterpreting the war as a sin, a revolt against God’s will. Others never did regain their faith. As one Canadian Anglican recalled about his grandfather, who had fought in the Great War:

I don’t think he ever got over what happened to him in the war. He used to say that the church told him God wanted him to go to war. What he saw in the war made him believe there was no God. He never wanted to be a hypocrite – so he never went back inside a church.

The veteran in question was the son of Anglican priest and had previously been very active in the church, but after his loss of faith he would not even attend the weddings of his children and grandchildren. As his grandson put it, “He wasn’t willing to pretend something that wasn’t real for him anymore.”

- Elliot Hanowski, Towards A Godless Dominion: Unbelief in Interwar Canada. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2024. p. 13-18.

#world war 1#world war 1 canada#canadian expeditionary force#canadian soldiers#canadian veterans#canadian literature#literary study#anticlericalism#christianity in canada#history of irreligion#atheism#history of atheism#history of religion#academic quote#canadian history#towards a godless dominion#great depression in canada#interwar period#reading 2024

0 notes

Text

Notes on *Zero to One* by Peter Thiel

Not a recap per se of his book on startups, subtitled Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future, but rather a hodgepodge of things I found interesting or memorable from my fairly quick (<1 week) read...

2 main things I remember:

Business leaders praising competition is B.S. You don't want competition, you want monopoly. Business leaders that praise competition are trying to cover for the fact the really run a monopoly. Business leaders saying they have a monopoly are coping due to the fact they run a commoditized business dealing with immense competition.

His definite/indefinite-optimistic/pessimistic framework of explaining the world, how the Baby Boomers flipped American society to indefinite from definite because things kept getting better for them without them having to do anything, how I was raised by Boomers so maybe my worldview is more shaped by that than I realize, how we need to get back to definite, the future must be planned.

10 other notes:

Startups do better the less cash the CEO is paid, cash signals you value the present more than the future.

The best startups are like cults, don't worry if your company doesn't make sense to conventional professionals (difference is cults tend to be fantastically wrong about something, startups are fantastically right about something)

Distribution doldrums - small and medium businesses don't not use tools common to bigger businesses on account of being particularly backward, it just didn't make sense for someone to sell to them, they are in the dead zone of needing more attention than traditional advertising aimed at consumers, insteading personal sales like big business needs but being too small to be worth the sales effort

Look around, if you don't see any sales people, you are the sales person

Computers are complements for humans not replacements, the most valuable businesses of the coming decades will be built by entrepreneurs seeking to empower people rather than making them obsolete, this book came out in 2014, I wonder what he thinks of AI

We should be more tolerant of founders who seem strange or extreme, we need unusual individuals to lead companies beyond mere incrementalism

Startup questions - engineering (breakthrough tech over incremental improvement?), timing (why now?), monopoly (starting with big share of market?), people (right people? suit and tie to pitch is red flag, tech leaders wear T-shirt and jeans), distribution (do you have a way to deliver not just create you product?), durability (defensible market pos in 10-20 years?), secret (identified a unique opportunity other don't see?)

Founder's paradox - single greatest danger for a founder is to become so certain of his own myth that he loses his mind, but an equally insidious danger for every business is to lose all sense of myth and mistake disenchantment for wisdom

No one knows what the future will bring - recurrent collapse (boom and bust), plateau (incrementalism, the future will look like the present), extinction (everyone dies), takeoff (the singularity)

Only by seeing our work anew, as fresh and strange as it was to the ancients who saw it first, can we both recreate it and preserve it for the future...because our task to day is to find singular ways to create the new things that will make the future not just different, but better, to go from 0 to 1...the essential first step is to think for yourself

0 notes

Text

[...] the concept of true or orthodox “religion” was in some sense constructed by being distinguished from the false religion of “superstition” (we can hear echoes of Protestant anti-Catholicism and earlier Christian anti-paganism). Similarly, true “science” or proper scholarship was formulated in opposition to “superstition” (often understood as occult or fake science). Moreover, from both vantages, the prototypical superstitions were belief in spirits and “magic.” In this respect, terms like superstition and magic, while fluid, open ended, and constantly changing, nevertheless were not completely empty signifiers because they inherited these older polemics. Superstition went from “wrong” because it was diabolical or pagan to “mistaken” because it was antiscientific.

– Jason Ā. Josephson-Storm, The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I still identify as a Christian but I don't follow the church for this very reason. First off any creation myth where life comes from a male is a projection of womb envy. The word origionally used for god was gender-nutral, god does not have a human body so he/she does not have a penis or vagina so they can neither be male or female.

Second, for the time in which it was recorded, the Gospel was ENORMOUSLY progressive. It gave women dominion over the home (where previously they had dominion over absolutely fucking nothing so this was a big upgrade, progress happens in steps, we can't apply today's politics to an ancient civilization), it spoke out against imperialist occupation, it spoke out against capitalism and in favor of community, i don't think theres a single thing that Jesus himself said that I disagree with.

It was man who perverted religion, not god. No intelligent or loving god would punish you for rejecting an archaic oppressive system being carried out in his name. No god who sent his son to die for our sins wants to see anybody oppressed (when Jesus came to earth he did not come to the religious or political leaders, he went to poor fishermen and prostitutes and tax collectors and lepers and the disenfranchised). A religion that preaches oppression and has not updated itself politically since the days of the romans is NOT what god sent a son or profit or even himself to accomplish.

I believe in a loving God who made me in his image and sent his son to die for my sins so that one day I can be reunited with my lost loved ones in paradise or whatever the next stage is, and that God does not punish for questioning or challenging things that need to be updated or are oppressing people. God will forgive your disenchantment with what men have done to his word. He will not forgive the men who corrupted it into a tool of hatred and oppression.

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

The recent spate of accounting fraud scandals signals the end of an era. Disillusionment and disenchantment with American capitalism may yet lead to a tectonic ideological shift from laissez faire and self regulation to state intervention and regulation. This would be the reversal of a trend dating back to Thatcher in Britain and Reagan in the USA. It would also cast some fundamental - and way more ancient - tenets of free-marketry in grave doubt.

Markets are perceived as self-organizing, self-assembling, exchanges of information, goods, and services. Adam Smith's "invisible hand" is the sum of all the mechanisms whose interaction gives rise to the optimal allocation of economic resources. The market's great advantages over central planning are precisely its randomness and its lack of self-awareness.

Market participants go about their egoistic business, trying to maximize their utility, oblivious of the interests and action of all, bar those they interact with directly. Somehow, out of the chaos and clamor, a structure emerges of order and efficiency unmatched. Man is incapable of intentionally producing better outcomes. Thus, any intervention and interference are deemed to be detrimental to the proper functioning of the economy.

It is a minor step from this idealized worldview back to the Physiocrats, who preceded Adam Smith, and who propounded the doctrine of "laissez faire, laissez passer" - the hands-off battle cry. Theirs was a natural religion. The market, as an agglomeration of individuals, they thundered, was surely entitled to enjoy the rights and freedoms accorded to each and every person. John Stuart Mill weighed against the state's involvement in the economy in his influential and exquisitely-timed "Principles of Political Economy", published in 1848.

Undaunted by mounting evidence of market failures - for instance to provide affordable and plentiful public goods - this flawed theory returned with a vengeance in the last two decades of the past century. Privatization, deregulation, and self-regulation became faddish buzzwords and part of a global consensus propagated by both commercial banks and multilateral lenders.

As applied to the professions - to accountants, stock brokers, lawyers, bankers, insurers, and so on - self-regulation was premised on the belief in long-term self-preservation. Rational economic players and moral agents are supposed to maximize their utility in the long-run by observing the rules and regulations of a level playing field.

This noble propensity seemed, alas, to have been tampered by avarice and narcissism and by the immature inability to postpone gratification. Self-regulation failed so spectacularly to conquer human nature that its demise gave rise to the most intrusive statal stratagems ever devised. In both the UK and the USA, the government is much more heavily and pervasively involved in the minutia of accountancy, stock dealing, and banking than it was only two years ago.

But the ethos and myth of "order out of chaos" - with its proponents in the exact sciences as well - ran deeper than that. The very culture of commerce was thoroughly permeated and transformed. It is not surprising that the Internet - a chaotic network with an anarchic modus operandi - flourished at these times.

The dotcom revolution was less about technology than about new ways of doing business - mixing umpteen irreconcilable ingredients, stirring well, and hoping for the best. No one, for instance, offered a linear revenue model of how to translate "eyeballs" - i.e., the number of visitors to a Web site - to money ("monetizing"). It was dogmatically held to be true that, miraculously, traffic - a chaotic phenomenon - will translate to profit - hitherto the outcome of painstaking labour.

Privatization itself was such a leap of faith. State owned assets - including utilities and suppliers of public goods such as health and education - were transferred wholesale to the hands of profit maximizers. The implicit belief was that the price mechanism will provide the missing planning and regulation. In other words, higher prices were supposed to guarantee an uninterrupted service. Predictably, failure ensued - from electricity utilities in California to railway operators in Britain.

The simultaneous crumbling of these urban legends - the liberating power of the Net, the self-regulating markets, the unbridled merits of privatization - inevitably gave rise to a backlash.

The state has acquired monstrous proportions in the decades since the Second world War. It is about to grow further and to digest the few sectors hitherto left untouched. To say the least, these are not good news. But we libertarians - proponents of both individual freedom and individual responsibility - have brought it on ourselves by thwarting the work of that invisible regulator - the market.

#businessman#dealer#director#merchant#executive#tycoon#industrialist#manager#entrepreneur#magnate#trader#broker

0 notes

Text

References

Greenwood, S. (2009). ‘Not Only, but Also’: A New Attitude Toward Science. In The Anthropology of Magic (pp. 145–157). Anthropology Book, Routledge.

Gregory, K. (2012). Negotiating Precarity: Tarot as Spiritual Entrepreneurialism. Women’s Studies Quarterly, 40(3/4), 264–280. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23333498.

Josephson-Storm, J. A. (2017). Introduction. In The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and The Birth of The Human Sciences (pp. 1–8). The University of Chicago Press.

Kieffer, K.G. (2020). Manifesting Millions: How Women’s Spiritual Entrepreneurship Genders Capitalism. Nova Religio 24(2), 80-104. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/772841.

Latour, B. (1993). We Have Never Been Modern. Harvard University Press.

0 notes

Conversation

Sigyn: [about Theoric] I'm gonna have to kill him or something.

Loki: Do it! Do it! Do it! And after you kill him we can hide the body. Then we could join the search party, and you and I can look at each other and try not to laugh.

#loki#sigyn#logyn#Loki Laufeyson#loki god of mischief#Loki God of stories#norse myth#norse mythology#disenchantment

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

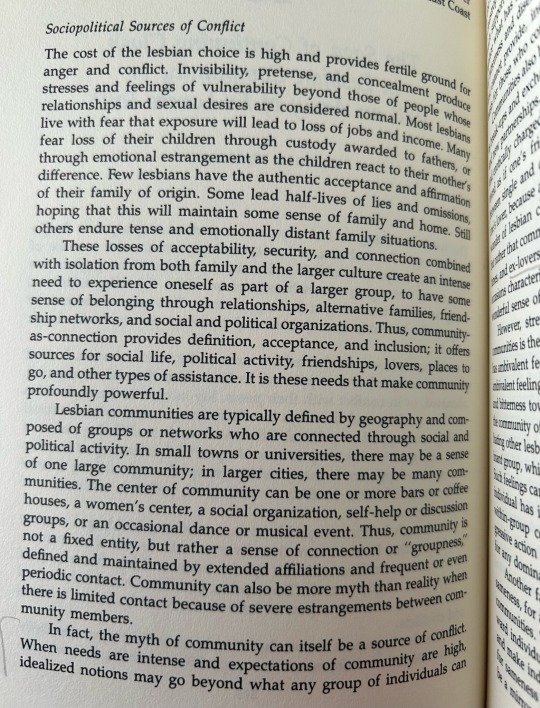

["Sociopolitical sources of conflict

The cost of the lesbian choice is high and provides fertile ground for anger and conflict. Invisibility, pretense, and concealment produce stresses and feelings of vulnerability beyond those of people whose relationships and sexual desires are considered normal. Most lesbians live with fear that exposure will lead to loss of jobs and income. Many fear loss of their children through custody awarded to fathers, or through emotional estrangement as the children react to their mother's difference. Few lesbians have the authentic acceptance and affirmation of their family of origin. Some lead half-lives of lies and omissions, hoping that this will maintain some sense of family and home. Still others endure tense and emotionally distance family situations.

These losses of acceptability, security, and connection combined with isolation from both family and the larger culture create an intense need to experience oneself as part of a larger group, to have some sense of belonging through relationships, alternative families, friendship networks, and social and political organizations. Thus, community-as-connection provides definition, acceptance, and inclusion; it offers sources for social life, political activity, friendships, lovers, places to go, and other types of assistance. It is these needs that make community profoundly powerful.

Lesbian communities are typically defined by geography and composed of groups or networks who are connected through social and political activity. In small towns or universities, there may be a sense of one larger community; in larger cities, there may be many communities. The center of community can be one or more bars or coffee houses, a women's center, a social organization, self-help or discussion groups, or an occasional dance or musical event Thus, community is not a fixed entity, but rather a sense of connection or "groupness," defined and maintained by extended affiliations and frequent or even periodic contact. Community can also be more myth than reality when there is limited contact because of severe estrangement between community members.

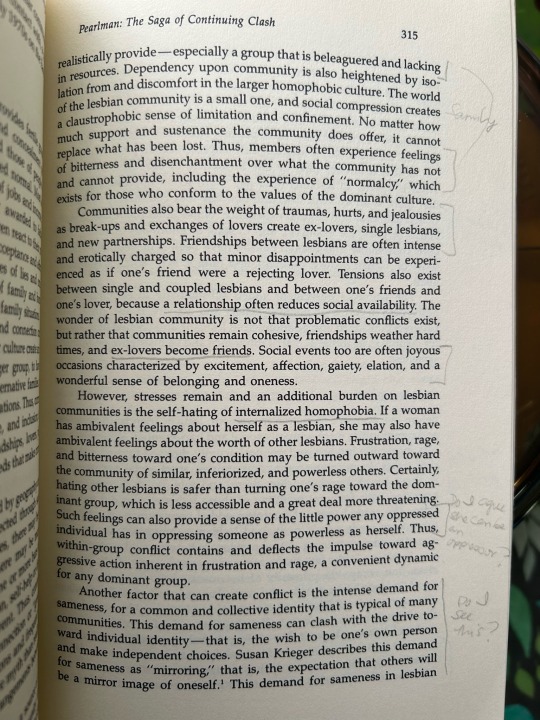

In fact, the myth of community itself can be a source of conflict. When needs are intense and expectations of community are high, idealized notions may go beyond what any group of individuals can realistically provide— especially a group that is beleaguered and lacking in resources. Dependency upon community is also heightened by isolation from and discomfort in the larger homophobic culture. The world of the lesbian community is a small one, and social compression creates a claustrophobic sense of limitation and confinement. No matter how much support and sustenance the community does offer, it cannot replace what has been lost. Thus, members often experience feelings of bitterness and disenchantment over what the community has not and cannot provide, including the experience of "normalcy," which exists for those who conform to the values of the dominant culture. Communities also bear the weight of traumas, hurts, and jealousies as break-ups and exchanges of lovers creates ex-lovers, single lesbians, and new partnerships. Friendships between lesbians are often intense and erotically charged so that minor disagreements can be experienced as if one's friend were a rejecting lover. Tensions also exist between single and coupled lesbians and between one's friends and one's lover, because a relationship often reduces social availability. The wonder of lesbian community is not that problematic conflicts exist, but rather that communities remain cohesive, friendships weather hard times, and ex-lovers become friends. Social events too often are joyous occasions characterized by excitement, affection, gaiety, elation, and a wonderful sense of belonging and oneness.

However, stresses remain and an addition burden on lesbian communities is the self-hating of internalized homophobia. If a woman has ambivalent feelings about herself as a lesbian, she may also have ambivalent feelings about the worth of other lesbians. Frustration, rage, and bitterness toward one's condition may be turned outward toward the community of similar, inferiorized, and powerless others. Certainly, hating other lesbians is safer than turning one's rage toward the dominant group, which is less accessible and a great deal more threatening. Such feelings can also provide a sense of the little power any oppressed individual has in oppressing someone as powerless as herself. Thus, within-group conflict contains and deflects the impulse toward aggressive action inherent in frustration and rage, a convenient dynamic for any dominant group.

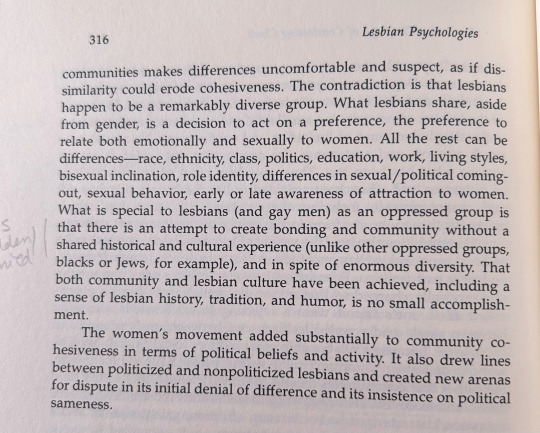

Another factor that can create conflict is the intense demand for sameness, for a common and collective identity that is typical of many communities. This demand for sameness can clash with the drive toward individual identity— that is, the wish to be one's own person and make independent choices. Susan Kreiger describes this demand for sameness as "mirroring," that is, the expectation that others will be a mirror image of oneself. This demand for sameness in lesbian community makes difference uncomfortable and suspect, as if dissimilarity could erode cohesiveness. The contradiction is that lesbians happen to be a remarkably diverse group. What lesbians share, aside from gender, is a decision to act on a preference, the preference to relate both emotionally and sexually to women. All the rest can be differences— race, ethnicity, class, politics, education, work, living styles, bisexual inclination, role identity, differences in sexual/political coming out, sexual behavior, early or late awareness of attraction to women. What is special to lesbians (and gay men) as an oppressed group is that there is an attempt to create bonding and community without a shared historical or cultural experience (unlike other oppressed groups, Blacks or Jews, for example), and in spite of enormous diversity. That both community and lesbian culture have been achieved, including a sense of lesbian history, tradition, and humor, is no small accomplishment.

The women's movement added substantially to community cohesiveness in terms of political beliefs and activities. It also drew lines between politicized and nonpoliticized lesbians and created new arenas for dispute in its initial denial of difference and its insistence on political sameness."]

sarah f. pearlman, from the saga of continuing clash in lesbian community, or will an army of ex lovers fail? from lesbian psychologies: explorations and challenges, edited by the boston lesbian psychologies collective, 1987

99 notes

·

View notes