#my controversial civil war history opinion

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Genius genius genius idea for the university thing omg

Who would teach what because I'm so conflicted.

At first I thought Johnny would teach chemistry (I'm a sucker for fics that show how smart he can be) but then again art teacher Jonny giving reader drawings of them is just so ugh</3

Simon teaching history?? Maybe?? I just have a feeling he gets super into ancient Greece and Roman war tactics. Presents old artifacts to reader like a cat catching a mouse and reader being like "did you take this from the archives without permission???"

I can feel in my bones that Price would be a philosophy teacher. He's an older man! He's experienced a lot of things in his life and it's made him very introspective. And seeing such an interesting bird like reader makes him want to have deep and meaningful conversations!

Gaz as a physics professor possibly? (helicopter joke) but he has such a passion for the topic and the way he talks about it (despite how God awful that subject is) sort of woos reader in a way, he's just so charismatic! Maybe reader struggles, or maybe they don't, either way you bet their ass is pouncing on the opportunity to get private tutoring from him the second he offers it.

Anywho I hope you have a good day!! Mwah!!

MY DAY IS GOOD NOW

I had some thoughts about this man but I do love your takes!!

I think Johnny would be painting/art history/ceramics because those concentrations are artistic and make excellent use of chemistry! Maybe he used to be a restoration specialist, he's an expert in the chemical compounds that make up varnishes and glazes used in antiquity. And yeah. When you're at the pottery wheel he can sit behind you and guide your hands like in the movie Ghost. What about it.

Controversial opinion. Ghost as a fibers/fashion professor. While I think Gaz is conventionally the best dressed, Gaz dresses safe. Simon does make his own masks-- I think if he had the time and resources, he could get really into making his own clothing. And during your meetings he has you act his dress form, because he thinks a live model is always better, and it gives him a reason to touch and squeeze you.

I thought of Gaz as a sociology/social sciences professor. I think he's got a lot of empathy and is interested in the study of relationships. And if that gets him the chance to act out certain scenarios for the purposes of demonstration, all the better. If we're going full arts I could see him in theater studies as well.

I Initially thought of Price as the history teacher. I think he's got the british disease of being obsessed with foreign antiquity. And he's always going on about the rituals and practices of ancient civilizations... Did you know noble Roman couples would sleep in a special bed just for their wedding night? And then it would be displayed in the house as a symbol. He just thinks that's so neat. Aztec people sometimes used cacao as a very special, sacred courting gift. But yeah, him always coming to office hours meetings with a hot chocolate for you could mean nothing.... But i do LOVE the idea of him as the Philosophy teacher always getting lost on tangents... And he just wants your opinions on everything. The way he stares so intently as you speak. Such an interesting little bird, with such a fresh perspective.

#writing#cod fanfic#john price#cod#simon ghost riley#john soap mactavish#john soap mctavish x reader#simon ghost riley x reader#ghost x reader#soap x reader#kyle gaz garrick x reader#kyle gaz garrick#gaz x reader#john price x reader#university AU

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

My (possibly) controversial dance era opinion is that even if Rhaenyra and her children had left Westeros entirely, there still would have been an ursurpation and civil war.

Aemond blatantly hated those brothers of his. Even for a historical text, Fire and Blood really drives the nail in regarding his selfishness and his aversion to “sharing [his] glory.” And, if I remember correctly, this point isn’t even debatable according to the scholars writing about this point in history. F&B just straight up states “yeah, this guy really wanted it all for himself” without leaving room for speculation, debate, or even attaching a disclaimer to it like other wild stories have.

#hotd#house of the dragon#the dance of the dragons#fire and blood#house targaryen#aemond targaryen#aegon ii targaryen#daeron targaryen#team black#pro team black#anti team green

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why People Are Wrong About the Puritans of the English Civil War and New England

Oh well, if you all insist, I suppose I can write something.

(oh good, my subtle scheme is working...)

Introduction:

So the Puritans of the English Civil War is something I studied in graduate school and found endlessly fascinating in its rich cultural complexity, but it's also a subject that is popularly wildly misunderstood because it's caught in the jaws of a pair of distorted propagandistic images.

On the one hand, because the Puritans settled colonial New England, since the late 19th century they've been wrapped up with this nationalist narrative of American exceptionalism (that provides a handy excuse for schoolteachers to avoid talking about colonial Virginia and the centrality of slavery to the origins of the United States). If you went to public school in the United States, you're familiar with the old story: the United States was founded by a people fleeing religious persecution and seeking their freedom, who founded a society based on social contracts and the idea that in the New World they were building a city on a hill blah blah America is an exceptional and perfect country that's meant to be an example to the world, and in more conservative areas the whole idea that America was founded as an explicitly Christian country and society. Then on the other hand, you have (and this is the kind of thing that you see a lot of on Tumblr) what I call the Matt Damon-in-Good-Will-Hunting, "I just read Zinn's People's History of the United States in U.S History 101 and I'm home for my first Thanksgiving since I left for colleg and I'm going to share My Opinions with Uncle Burt" approach. In this version, everything in the above nationalist narrative is revealed as a hideous lie: the Puritans are the source of everything wrong with American society, a bunch of evangelical fanatics who came to New England because they wanted to build a theocracy where they could oppress all other religions and they're the reason that abortion-banning, homophobic and transphobic evangelical Christians are running the country, they were all dour killjoys who were all hopelessly sexually repressed freaks who hated women, and the Salem Witch Trials were a thing, right?

And if anyone spares a thought to examine the role that Puritans played in the English Civil War, it basically short-hands to Oliver Cromwell is history's greatest monster, and didn't they ban Christmas?

Here's the thing, though: as I hope I've gotten across in my posts about Jan Hus, John Knox, and John Calvin, the era of the Reformation and the Wars of Religion that convulsed the Early Modern period were a time of very big personalities who were complicated and not very easy for modern audiences to understand, because of the somewhat oblique way that Early Modern people interpreted and really believed in the cultural politics of religious symbolism. So what I want to do with this post is to bust a few myths and tease out some of the complications behind the actual history of the Puritans.

Did the Puritans Experience Religious Persecution?

Yes, but that wasn't the reason they came to New England, or at the very least the two periods were divided by some decades. To start at the beginning, Puritans were pretty much just straightforward Calvinists who wanted the Church of England to be a Calvinist Church. This was a fairly mainstream position within the Anglican Church, but the "hotter sort of Protestant" who started to organize into active groups during the reigns of Elizabeth and James I were particularly sensitive to religious symbolism they (like the Hussites) felt smacked of Catholicism and especially the idea of a hierarchy where clergy were a better class of person than the laity.

So for example, Puritans really first start to emerge during the Vestments Controversy in the reign of Edward VI where Bishop Hooper got very mad that Anglican priests were wearing the cope and surplice, which he thought were Catholic ritual garments that sought to enhance priestly status and that went against the simplicity of the early Christian Church. Likewise, during the run-up to the English Civil War, the Puritans were extremely sensitive to the installation of altar rails which separated the congregation from the altar - they considered this to be once again a veneration of the clergy, but also a symbolic affirmation of the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation.

At the same time, they were not the only religious faction within the Anglican Church - and this is where the religious persecution thing kicks in, although it should be noted that this was a fairly brief but very emotionally intense period. Archbishop William Laud was a leading High Church Episcopalian who led a faction in the Church that would become known as Laudians, and he was just as intense about his religious views as the Puritans were about his. A favorite of Charles I and a first advocate of absolutist monarchy, Laud was appointed Archbishop of Canturbury in 1630 and acted quickly to impose religious uniformity of Laudian beliefs and practices - ultimately culminating in the disastrous decision to try imposing Episcopalianism on Scotland that set off the Bishop's Wars. The Puritans were a special target of Laud's wrath: in addition to ordering the clergy to do various things offensive to Puritans that he used as a shibboleth to root out clergy with Puritan sympathies and fire them from their positions in the Church, he established official religious censors who went after Puritan writers like William Prynne for seditious libel and tortured them for their criticisms of his actions, cropping their ears and branding them with the letters SL on their faces. Bringing together the powers of Church and State, Laud used the Court of Star Chamber (a royal criminal court with no system of due process) to go after anyone who he viewed as having Puritan sympathies, imposing sentences of judicial torture along the way.

It was here that the Puritans began to make their first connections to the growing democratic movement in England that was forming in opposition to Charles I, when John Liliburne the founder of the Levellers was targeted by Laud for importing religious texts that criticized Laudianism - Laud had him repeatedly flogged for challenging the constitutionality of the Star Chamber court, and "freeborn John" became a martyr-hero to the Puritans.

When the Long Parliament met in 1640, Puritans were elected in huge numbers, motivated as they were by a combination of resistance to the absolutist monarchism of Charles I and the religious policies of Archbishop Laud - who Parliament was able to impeach and imprison in the Tower of the London in 1641. This relatively brief period of official persecution that powerfully shaped the Puritan mindset was nevertheless disconnected from the phenomena of migration to New England - which had started a decade before Laud became Archbishop of Canterbury and continued decades after his impeachment.

The Puritans Just Wanted to Oppress Everyone Else's Religion:

This is the very short-hand Howard Zinn-esque critique we often see of the Puritan project in the discourse, and while there is a grain of truth to it - in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the Congregational Church was the official state religion, no other church could be established without permission from the Congregational Church, all residents were required to pay taxes to support the Congregational Church, and only Puritans could vote. Moreover, there were several infamous incidents where the Puritan establishment put Anne Hutchinson on trial and banished her, expelled Roger Williams, and hanged Quakers.

Here's the thing, though: during the Early Modern period, every single side of every single religious conflict wanted to establish religious uniformity and oppress the heretics: the Catholics did it to the Protestants where they could mobilize the power of the Holy Roman Emperor against the Protestant Princes, the Protestants did it right back to the Catholics when Gustavus Adolphus' armies rolled through town, the Lutherans and the Catholics did it to the Calvinists, and everybody did it to the Anabaptists.

That New England was founded as a Calvinist colony is pretty unremarkable, in the final analysis. (By the by, both Hutchinson and Williams were devout if schismatic Puritans who were firmly of the belief that the Anglican Church was a false church.) What's more interesting is how quickly the whole religious project broke down and evolved into something completely different.

Essentially, New England became a bunch of little religious communes that were all tax-funded, which is even more the case because the Congregationalist Church was a "gathered church" where the full members of the Church (who were the only people allowed to vote on matters involving the church, and were the only ones who were allowed to be given baptism and Communion, which had all kinds of knock-on effects on important social practices like marriages and burials) and were made up of people who had experienced a conversion where they can gained an assurance of salvation that they were definitely of the Elect. You became a full member by publicly sharing your story of conversion (which had a certain cultural schema of steps that were supposed to be followed) and having the other full members accept it as genuine.

This is a system that works really well to bind together a bunch of people living in a commune in the wilderness into a tight-knit community, but it broke down almost immediately in the next generation, leading to a crisis called the Half-Way Covenant.

The problem was that the second generation of Puritans - all men and women who had been baptized and raised in the Congrgeationalist Church - weren't becoming converted. Either they never had the religious awakening that their parents had had, or their narratives weren't accepted as genuine by the first generation of commune members. This meant that they couldn't hold church office or vote, and more crucially it meant that they couldn't receive the sacrament or have their own children baptized.

This seemed to suggest that, within a generation, the Congregationalist Church would essentially define itself into non-existence and between the 1640s and 1650s leading ministers recommended that each congregation (which was supposed to decide on policy questions on a local basis, remember) adopt a policy whereby the children of baptized but unconverted members could be baptized as long as they did a ceremony where they affirmed the church covenant. This proved hugely controversial and ministers and laypeople alike started publishing pamphlets, and voting in opposing directions, and un-electing ministers who decided in the wrong direction, and ultimately it kind of broke the authority of the Congregationalist Church and led to its eventual dis-establishment.

The Puritans are the Reason America is So Evangelical:

This is another area where there's a grain of truth, but ultimately the real history is way more complicated.

Almost immediately from the founding of the colony, the Puritans begin to undergo mutation from their European counterparts - to begin with, while English Puritans were Calvinists and thus believed in a Presbyterian form of church government (indeed, a faction of Puritans during the English Civil War would attempt to impose a Presbyterian Church on England.), New England Puritans almost immediately adopted a congregationalist system where each town's faithful would sign a local religious constitution, elect their own ministers, and decide on local governance issues at town meetings.

Essentially, New England became a bunch of little religious communes that were all tax-funded, which is even more the case because the Congregationalist Church was a "gathered church" where the full members of the Church (who were the only people allowed to vote on matters involving the church, and were the only ones who were allowed to be given baptism and Communion, which had all kinds of knock-on effects on important social practices like marriages and burials) and were made up of people who had experienced a conversion where they can gained an assurance of salvation that they were definitely of the Elect. You became a full member by publicly sharing your story of conversion (which had a certain cultural schema of steps that were supposed to be followed) and having the other full members accept it as genuine.

This is a system that works really well to bind together a bunch of people living in a commune in the wilderness into a tight-knit community, but it broke down almost immediately in the next generation, leading to a crisis called the Half-Way Covenant.

The problem was that the second generation of Puritans - all men and women who had been baptized and raised in the Congrgeationalist Church - weren't becoming converted. Either they never had the religious awakening that their parents had had, or their narratives weren't accepted as genuine by the first generation of commune members. This meant that they couldn't hold church office or vote, and more crucially it meant that they couldn't receive the sacrament or have their own children baptized.

This seemed to suggest that, within a generation, the Congregationalist Church would essentially define itself into non-existence and between the 1640s and 1650s leading ministers recommended that each congregation (which was supposed to decide on policy questions on a local basis, remember) adopt a policy whereby the children of baptized but unconverted members could be baptized as long as they did a ceremony where they affirmed the church covenant. This proved hugely controversial and ministers and laypeople alike started publishing pamphlets, and voting in opposing directions, and un-electing ministers who decided in the wrong direction, and accusing one another of being witches. (More on that in a bit.)

And then the Great Awakening - which to be fair, was a major evangelical effort by the Puritan Congregationalist Church, so it's not like there's no link between evangelical - which was supposed to promote Congregational piety ended up dividing the Church and pretty soon the Congregationalist Church is dis-established and it's safe to be a Quaker or even a Catholic on the streets of Boston.

But here's the thing - if we look at which denominations in the United States can draw a direct line from themselves to the Congregationalist Church of the Puritans, it's the modern Congregationalists who are entirely mainstream Protestants whose churches are pretty solidly liberal in their politics, the United Church of Christ which is extremely cultural liberal, and it's the Unitarian Universalists who are practically issued DSA memberships. (I say this with love as a fellow comrade.)

By contrast, modern evangelical Christianity (although there's a complicated distinction between evangelical and fundamentalist that I don't have time to get into) in the United States is made up of an entirely different set of denominations - here, we're talking Baptists, Pentacostalists, Methodists, non-denominational churches, and sometimes Presbyterians.

The Puritans Were Dour Killjoys Who Hated Sex:

This one owes a lot to Nathaniel Hawthorne's Scarlet Letter.

The reality is actually the opposite - for their time, the Puritans were a bunch of weird hippies. At a time when most major religious institutions tended to emphasize the sinful nature of sex and Catholicism in particular tended to emphasize the moral superiority of virginity, the Puritans stressed that sexual pleasure was a gift from God, that married couples had an obligation to not just have children but to get each other off, and both men and women could be taken to court and fined for failing to fulfill their maritial obligations.

The Puritans also didn't have much of a problem with pre-marital sex. As long as there was an absolute agreement that you were going to get married if and when someone ended up pregnant, Puritan elders were perfectly happy to let young people be young people. Indeed, despite the objection of Jonathan Edwards and others there was an (oddly similar to modern Scandinavian customs) old New England custom of "bundling," whereby a young couple would be put into bed together by their parents with a sack or bundle tied between them as a putative modesty shield, but where everyone involved knew that the young couple would remove the bundle as soon as the lights were turned out.

One of my favorite little social circumlocutions is that there was a custom of pretending that a child clearly born out of wedlock was actually just born prematurely to a bride who was clearly nine months along, leading to a rash of surprisingly large and healthy premature births being recorded in the diary of Puritan midwife Martha Ballard. Historians have even applied statistical modeling to show that about 30-40% of births in colonial America were pre-mature.

But what about non-sexual dourness? Well, here we have to understand that, while they were concerned about public morality, the Puritans were simultaneously very strict when it came to matters of religion and otherwise normal people who liked having fun. So if you go down the long list of things that Puritans banned that has landed them with a reputation as a bunch of killjoys, they usually hide some sort of religious motivation.

So for example, let's take the Puritan iconoclastic tendency to smash stained glass windows, whitewash church walls, and smash church organs during the English Civil War - all of these things have to do with a rejection of Catholicism, and in the case of church organs a belief that the only kind of music that should be allowed in church is the congregation singing psalms as an expression of social equality. At the same time, Puritans enjoyed art in a secular context and often had portraits of themselves made and paintings hung on their walls, and they owned musical instruments in their homes.

What about the wearing nothing but black clothing? See, in our time wearing nothing but black is considered rather staid (or Goth), but in the Early Modern period the dyes that were needed to produce pure black cloth were incredibly expensive - so wearing all black was a sign of status and wealth, hence why the Hapsburgs started emphasizing wearing all-black in the same period. However, your ordinary Puritan couldn't afford an all-black attire and would have worn quite colorful (but much cheaper) browns and blues and greens.

What about booze and gambling and sports and the theater and other sinful pursuits? Well, the Puritans were mostly ok with booze - every New England village had its tavern - but they did regulate how much they could serve, again because they were worried that drunkenness would lead to blasphemy. Likewise, the Puritans were mostly ok with gambling, and they didn't mind people playing sports - except that they went absolutely beserk about drinking, gambling, and sports if they happened on the Sabbath because the Puritans really cared about the Sabbath and Charles I had a habit of poking them about that issue. They were against the theater because of its association with prostitution and cross-dressing, though, I can't deny that. On the other hand, the Puritans were also morally opposed to bloodsports like bear-baiting, cock-fighting, and bare-knuckle boxing because of the violence it did to God's creatures, which I guess makes them some of the first animal rights activsts?

They Banned Christmas:

Again, this comes down to a religious thing, not a hatred of presents and trees - keep in mind that the whole presents-and-trees paradigm of Christmas didn't really exist until the 19th century and Dickens' Christmas Carol, so what we're really talking about here is a conflict over religious holidays - so what people were complaining about was not going to church an extra day in the year. I don't get it, personally.

See, the thing is that Puritans were known for being extremely close Bible readers, and one of the things that you discover almost immediately if you even cursorily read the New Testament is that Christ was clearly not born on December 25th. Which meant that the whole December 25th thing was a false religious holiday, which is why they banned it.

The Puritans Were Democrats:

One thing that I don't think Puritans get enough credit for is that, at a time when pretty much the whole of European society was some form of monarchist, the Puritans were some of the few people out there who really committed themselves to democratic principles.

As I've already said, this process starts when John Liliburne, an activist and pamphleteer who promoted the concept of universal human rights (what he called "freeborn rights"), took up the anti-Laudian cause and it continued through the mobilization of large numbers of Puritans to campaign for election to the Long Parliament.

There, not only did the Puritans vote to revenge themselves on their old enemy William Laud, but they also took part in a gradual process of Parliamentary radicalization, starting with the impeachment of Strafford as the architect of arbitrary rule, the passage of the Triennal Acts, the re-statement that non-Parliamentary taxation was illegal, the Grand Remonstrance, and the Militia Ordinance.

Then over the course of the war, Puritans served with distinction in the Parliamentary army, especially and disproportionately in the New Model Army where they beat the living hell out of the aristocratic armies of Charles I, while defying both the expectations and active interference of the House of Lords.

At this point, I should mention that during this period the Puritans divided into two main factions - Presbyterians, who developed a close political and religious alliance with the Scottish Covenanters who had secured the Presbyterian Church in Scotland during the Bishops' Wars and who were quite interested in extending an established Presbyterian Church; and Independents, who advocated local congregationalism (sound familiar) and opposed the concept of established churches.

Finally, we have the coming together of the Independents of the New Model Army and the Leveller movement - during the war, John Liliburne had served with bravery and distinction at Edgehill and Marston Moore, and personally capturing Tickhill Castle without firing a shot. His fellow Leveller Thomas Rainsborough proved a decisive cavalry commander at Naseby, Leicester, the Western Campaign, and Langport, a gifted siege commander at Bridgwater, Bristol, Berkeley Castle, Oxford, and Worcester. Thus, when it came time to hold the Putney Debates, the Independent/Leveller bloc had both credibility within the New Model Army and the only political program out there. Their proposal:

redistricting of Parliament on the basis of equal population; i.e one man, one vote.

the election of a Parliament every two years.

freedom of conscience.

equality under the law.

In the context of the 17th century, this was dangerously radical stuff and it prompted Cromwell and Fairfax into paroxyms of fear that the propertied were in danger of being swamped by democratic enthusiasm - leading to the imprisonment of Lilburne and the other Leveller leaders and ultimately the violent suppression of the Leveller rank-and-file.

As for Cromwell, well - even the Quakers produced Richard Nixon.

#history#puritans#calvinism#english civil war#oliver cromwell#the stupid meme about christmas#new england#protestantism

450 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the topic of judging historical figures by modern morals

This is heavily opinionated, and it's a topic I've seen debated a lot, so I figured as an American Revolutionary War account I'd give my take on it. I'd love to hear other people's takes, as long as we keep the discussion civil and respectful. Thank you!

There are so many things that were considered fine years ago but wouldn't be tolerated at all in modern society, and that's not a bad thing. In fact, it's good; it shows just how much we as a species have improved over time. I think it's beautiful that we've managed to come this far. However, because we as a society have advanced so much, the past starts to seem barbaric, and it'll only seem worse as we improve more and we'll have a longer list of what we see as wrong.

I don't believe it's fair to hold people who've been dead for years and years to a modern standard because how could they possibly know that what they were doing would be seen as horrible in the future if it was fine in their day? What if after we die, driving cars is seen as absolutely unnacceptable (bad example, but I couldn't think of anything that's acceptable now but could be horrible in the future)? We would have had no way of knowing that it would be seen as such an intolerable act and what if because driving cars would be seen as bad, any and all achievements we'd made would be dismissed and we'd be villainised for something we never could've had anyway of knowing would be wrong in future? It'd be unjust. The fact that I had to come up with an example proves that we have no way of knowing what'll be considered horrible in future, we can only guess.

But when a historical figure did something that was wrong even for their time, That's a completely different situation because then the 'they couldn't possibly know that it'd be seen as bad in the future' justification doesn't work anymore. I believe that it's perfectly fair to despise those kinds of historical figures because they would've known that what they were doing was wrong. such as men like Thomas Jefferson, who publicly spoke out against slavery but profited off of it, owned lots of slaves, and started having non-consensual relations with a girl who was considered too young even by 18th-century standards.

Also, when I say it's fair to hate such historical figures, I think I need to add: do not to hate on people for their favourite historical figure; some people like studying controversial men. I hate Thomas Jefferson and James Monroe, but I wouldn't belittle anyone who likes them and I can understand that they did a lot for America. It's incredibly important that, regardless on how much you love or hate a historical figure you have to remember the most important part about studying history: nuance! Everyone's morally grey and the best historians, anthropologists, etc. understand that looking at everything with a shallow black and white bad and good isn't going to get you anywere!

In conclusion, I believe that we shouldn't judge people by standards they never knew would exist and instead judge them by the standards of their day. Every person in the history of the world is morally grey and if you can't understand or don't want to acknowledge that nuance (the most important part of studying this kind of thing!) then history isn't for you.

#history#amrev#just going to tag all history fandoms#frev#civil war#american history#french history#controversial opinion?#opinion#controversial#american revolutionary war#world history#historical#19th century#18th century#16th century#17th century#1600s#1910s#american revolution#revwar#hamilton#thomas jefferson#us history#anthropology

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Opinion: Town Sums up the Delusions of the Right Wing

The embrace of the country star’s anti-city ‘modern lynching song’ by Republicans encapsulates their nostalgia and paranoia

— Arwa Mahdawi | July 20; 2023

‘Small towns are full of “good ol’ boys” who were “raised up right”. Cities, meanwhile, are hotbeds of violence … and diversity.’ Photograph: Wade Payne/Invision/AP

Jason Aldean is a country music star and a big fan of law and order. He loves the law so much, in fact, that he’s willing to take it into his own hands.

If you come to his (imaginary) small town and disrespect a cop or engage in any sort of protest, you will regret it.

Such is the theme of Aldean’s new song, Try That in a Small Town, which is all about how the singer and his pals will aggressively deal with unseemly behaviour on their turf. A sample extract: “Cuss out a cop, spit in his face … Well, try that in a small town / See how far ya make it down the road. / Around here, we take care of our own …”

A little later in the song Aldean elaborates further on what might happen if lines are crossed. “Got a gun that my grandad gave me / They say one day they’re gonna round up. / Well, that shit might fly in the city, good luck.” He is, it would appear, referencing a conspiracy theory that the government is going to confiscate Americans’ guns to impose martial law.

Try That in a Small Town was released in May but when the music video came out last Friday it generated immediate controversy. The video leaves little doubt as to what Aldean is trying to communicate: it intersperses footage of him singing in front of Maury county courthouse in Tennessee – the site of the lynching of a Black man, Henry Choate, in 1927 – with footage from protests, looting and civil unrest. Small towns are wholesome, the message is. Full of “good ol’ boys” who were “raised up right”. Cities, meanwhile, are hotbeds of violence … and diversity.

That last bit isn’t spelled out – it’s not like Aldean yells “I’m a massive racist!” in the middle of the track – but the dog whistles are difficult to ignore. The song has been called “a modern lynching song” by detractors and the video was pulled from Country Music Television (CMT) on Monday. (While CMT has confirmed the video was taken off rotation, it hasn’t put out a statement as to why.) Fellow country star Sheryl Crow has also voiced her disapproval. “There’s nothing small-town or American about promoting violence,” Crow tweeted on Tuesday. She further noted that Aldean should know better, “having survived a mass shooting”. Crow was referencing the shooting at Las Vegas’s Route 91 Harvest festival in 2017: the deadliest mass shooting by a lone shooter in modern US history. Aldean was performing and got out unscathed. He was lucky. Sixty people were killed and 867 injured. Those people weren’t killed and injured by a Black Lives Matter protester. They were killed by Stephen Paddock, an angry white man from Iowa.

Try That in a Small Town has generated a lot of criticism, but it also has fervent supporters. Including, of course, GOP lawmakers. “I am shocked by what I’m seeing in this country with people attempting to cancel this song and cancel Jason and his beliefs,” the South Dakota Republican governor, Kristi Noem, posted in a video on Twitter on Wednesday. The Tennessee house GOP leader, William Lamberth, similarly tweeted: “Loved this song since it was released and will continue to fight every day to spread small town values … Give it a listen. The woke mob will hate you for liking this song.” Sarah Huckabee Sanders, the governor of Arkansas, also didn’t miss the chance to stoke a little culture war. “The Left is now more concerned about Jason Aldean’s song calling out looters and criminals than they are about stopping looters and criminals,” she tweeted.

Aldean, for his part, is furious at insinuations there is anything racist in his song about shooting outsiders who come to his little country town.

“In the past 24 hours I have been accused of releasing a pro-lynching song,” Aldean tweeted on Wednesday, “and was subject to the comparison that I (direct quote) was not too pleased with the nationwide BLM protests. These references are not only meritless, but dangerous. There is not a single lyric in the song that references race or points to it – and there isn’t a single video clip that isn’t real news footage.”

If Aldean isn’t trying to make a point about the Black Lives Matter protests, what is Try That in a Small Town about then? Community, apparently. “When u grow up in a small town, it’s that unspoken rule of ‘we all have each other’s backs and we look out for each other,’” Aldean wrote on Instagram when he launched the video. “It feels like somewhere along the way, that sense of community and respect has gotten lost.”

Jason Aldean, from the ‘small town’ of Macon, Georgia. Photograph: Amy Harris/Invision/AP

Perhaps you’re wondering which quaint small town Aldean grew up in. The answer is: he didn’t. Aldean is from Macon, Georgia – a city with a population of about 153,000 people. Now he lives in Nashville, a city with a population of approximately 700,000. The small town he’s singing about is a product of his imagination.

But that’s conservatives for you. Last month Nikki Haley tweeted about how much better the US used to be back in the days before marginalized people had rights. “Do you remember when you were growing up, do you remember how simple life was, how easy it felt? It was about faith, family, and country,” she tweeted.

Was the past really that easy for the former South Carolina governor? By her own admission things have got a hell of a lot better for people who, like her, aren’t 100% white. “Years ago I was disqualified from a pageant because they didn’t know whether to put me in the white category or the black,” she wrote on Facebook in 2012. “I was neither. Tonight I watched my daughter get first place in her school pageant. God has an amazing way of bringing things full circle.” God also has an amazing away of depriving people like Haley of self-awareness.

Aldean’s song doesn’t just epitomize manufactured rightwing nostalgia, it also encapsulates rightwing paranoia. People on the right are obsessed with the idea that big cities are violent hotbeds of crime where you risk your life every time you nip out for a pint of milk. In reality, however, big cities tend to be safer than small towns. A 2013 study by the University of Pennsylvania, for example, found the risk of death from an injury was more than 20% higher in rural small towns than in larger cities. “Cars, guns and drugs are the unholy trinity causing the majority of injury deaths in the US” one of the researchers told NBC News at the time.

The pandemic, to be fair, saw a rise in violent crimes in cities. But even still, you’ve got a better chance of living a long, healthy life in a city. A 2021 US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report on mortality data from 1999 to 2019 found people living in rural areas die at higher rates than those living in urban areas. That’s because they have less access to healthcare and are more likely to live in poverty.

So what’s next for Aldean? Well, I’ve got some good news for all the Republican lawmakers screeching about how unfair it is that Aldean has been cancelled by the woke mob: he’s going to be fine. Indeed, he’s going to be more than fine. Country music (and America) has a way of opening its arms to people accused of racism and making them feel right at home. Just look at Morgan Wallen, for example. In February 2021 TMZ published a video of the musician drunkenly yelling the N-word during a conversation with a friend. He was shunned from polite society for a few months but made a rapid comeback. He won album of the year at the Academy of Country Music Awards in 2022. His song Last Night is currently in its 14th week at number one on the Billboard Hot 100. If it sticks there a little longer he’ll beat the 19-week record currently held by Lil Nas X’s Old Town Road, featuring Billy Ray Cyrus.

While people on the right may be railing about Aldean being “cancelled”, the sad truth is that this will probably help his career. He’ll go on Fox News and yell about wokeness. He’ll wallow in his imagined victimhood. His song will probably be played in rallies for the next Republican nominee for president. Aldean hasn’t been cancelled or silenced – his message has been amplified.

#Country | Race | Music | US News | Republicans#US Politics | Article | Comment | Arwa Mahdawi#The Guardian USA 🇺🇸

73 notes

·

View notes

Note

FYI: the author of that ""they deserve to die" is something you should never hear a leftist say. if you do, run" post is a Zionist. I guess that mindset doesn't apply to brown people, huh?

But also, you should consider that this is an extremely shallow view of leftism and violence as a tactic. What, you're a "punk" and you think any punk space got safe without a few nazis getting their teeth kicked in? They didn't. Sorry.

I hope you develop a punk mindset that's a little less about shitty bands and an aesthetic and a little more about having firmer political opinions and not agreeing with Zionists.

Your concern in the first paragraph was addressed in a previous post I’ll link to here.

Going off of that, I’m not sure what on my blog, besides the controversy surrounding this specific post (which again has already been addressed), would ever make you think that I would exclude anyone from the statement of ‘we shouldn't say anyone deserves to die’??? I simply. Do not think humans should be killing other humans. At all. Anywhere. On either side of any war. Like. One human should not be granted the power to decide the lifespan of another in my opinion

On that note, being anti-war is actually both a very punk stance AND a left-wing movement. Though I agree, it is a shallow view of leftism. Because leftism is SO much more than a single movement (like the civil rights movement, the feminist movement, the LGBTQ+ movement, the environmentalism movement, anarchy, socialism, the labor movement, and GOD the list goes on). But also. It *does* include being anti-war and anti-'they deserve to die'.

As far as Punk being anti-war and taking non-violent approaches to the larger socio-political changes in the world, I'd recommend looking into Peace Punk. It was very popular in the 70's and early 80's with bands like Subhumans, Zounds, and The Mob. Here's a great beginner article on it!

As to your point about nazis. I promise you I'm not oblivious to the history behind the phrase 'Nazi Punks Fuck Off'. I also would have hoped that someone would be able to see nuance in a statement that say 'lets not say everyone deserves death' and not read it as 'we should let nazis do what they want'. Because that would be stupid. And if you've interacted with my blog for any real length of time, then you would know that I ALWAYS support punching nazis. But evidently that must have slipped your brain.

Now as far as this part of your ask: "I hope you develop a punk mindset that's a little less about shitty bands and an aesthetic and a little more about having firmer political opinions"

First of all buddy, I think I've already demonstrated that my political opinions are pretty firmly set (and that someone hoping on anon isn't going to change them). Personally, I don't feel the need to scream about my political stances every second of the day to make myself feel validated and like a good person. Because I have a life outside of the internet. But you do you I guess. I would however say that its kinda a dick move to just assume that others aren't well educated or have developed opinions when you've evidently only looked at a single post on my blog without actually looking at my blog. Otherwise you would have seen the EXTENSIVE amount of research and punk culture that I've written about or collected either on my own or in collaboration with others.

Really its either that you just didn't look, or because you didn't immediately agree with me, that you decided that my political views had a very shaky foundation. In which case, please do grow the fuck up and learn how to deal with people that have differing opinions than you without being a bitch and ranting about it on anon thanks.

Also. I like my 'shitty bands'. Get over it (Also like. Punk is inherently connected to music and shitty bands? Do you not know that? Do you understand where punk even comes from? I'm all for not needing to listen to punk music to be a punk as long as you align with other facets of the counter culture, but being told NOT to focus on music that is politically charged and full of punk values and history. Well that's a new one lol)

And lastly. Dude if you don't like me, you don't have to be here? You can leave? No one is forcing you to read anything on my blog??? Bye???

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Asian Representation in Cyberpunk 2077

For a long while, I have this idea floating about writing what Cyberpunk 2077 did about Asian representation. This long overdue but similarly complex topic that was an unintended follow up to my previous post about my argument against Orientalism in Cyberpunk 2077. In that post, I tried to write as concisely as I can but I realized that I did not articulate further using the game itself which leads to some persistent confusion and casual assumptions about the game.

As a disclaimer, I am not defending orientalism or even war crimes while discussing about Cyberpunk 2077. I am not endorsing only negative portrayals of Asian people nor defending the problematic western stereotypes of Asians in the media history. We could have a civilized discussion over this entire matter because lucky for all of you, I am fluent enough in English that I could use my own voice for this. Every words that I wrote in this series; about the topics I explored, about myself, my lived experiences, my history, my opinions and my criticism are all solely my own. I think I am uniquely qualified to talk about many aspects of this topic but I like to think I am not immune to criticism and neither was the Cyberpunk 2077 game itself. What I generally hope was my writings would help, inform, educate and hopefully clarify some of the contentious takes directed towards me, CD Projekt RED, R. Talsorian Games and the video game; Cyberpunk 2077. There was simply no perfect Asian representation that could encompass all of the wealth of diversity. We couldn't perfectly portray everything either in academia, in media, in writing, non-fiction or even fictional works either by Asians or non-Asians. Asia is the largest continent on earth. Asian people are richly diverse, complex and sometimes described to many people across various ethnicities and nationalities. All we could in representation works was to attempt, to explore, to criticize and to create more and better works as an honor to ourselves and to our people. We all have our own stories to share and our interpretations. There was so many things that I could write about Asians in Cyberpunk franchise but I intend to fully explore again that was more than just the controversial Arasaka family or the Tyger Claws. I want to talk about the Asian aesthetics of Night City and many Asian characters in the game and including Cyberpunk Edgerunners' Lucyna Kushinada and Cyberpunk 2077 : No Coincidence's Aya and because of the impending release of Phantom Liberty, I am looking forward to explore Song So-mi @ Songbird. (Especially with the OST release, I know that CDPR used traditional Korean performance Pansori as Songbird's musical leitmotif and I'm so excited to explore that once I played the expansion) But for starters;

Not all Asians are East Asians

I wished I didn't have to write that down but I realized it was something that a lot of online discourses in English seemed to center itself either by non-Asians or East Asian diaspora in Western countries. It was most apparent within these published articles : Orientalism, Cyberpunk 2077, and Yellow Peril in Science Fiction and How Cyberpunk 2077 Resurrects the 1980s’ “Japan Panic” which were very hyperfixated on Arasaka and the Tyger Claws. Another element that I noticed from these articles and by their writers, they both neglect the fact that not every diasporic Asian portrayed in Cyberpunk 20777 are East Asians. Not every Asians are Japanese or Chinese or Korean.

I am not East Asian.

I am Southeast Asian.

My V was a Malay woman like me. Someone who was flawed, imperfect and maybe portrayed many sides that was very unbecoming to the image of a Malay Muslim woman. I created this Tumblr blog mainly to share my own CorpoV. She was my own OC that I was simply obsessed with. Cyberpunk 2077 remained to be the only game that truly allowed me to craft a genuine Southeast Asian woman protagonist with her personal history that was almost relevant to me on personal level.

However, V could be anyone of any races or ethnicity. She could also be Japanese, Korean or Chinese because the game have localization with those languages. In the game, V can love sushi, drink tea, burn incense and work for a fictional Imperial Japanese company. After all, Cyberpunk 2077 is a roleplaying game . But did you know who else was also a Southeast Asian in Cyberpunk 2077?

Aha... think I don't notice the casual disrespect towards our glorious living legendary Pinoy rockerboy ever? My next post will be all about Kerry Eurodyne.

We will discuss Kerry in the TTRPG, what he become in Cyberpunk 2077, his complicated history, his character analysis, his traditional Batok tattoos, his relationships to Johnny Silverhand, their band Samurai and other Filipino representation within Cyberpunk 2077 game. However, I have to admit that my own exposure to my dear neighbouring Philippines was genuinely abysmal. I live in West Malaysia and unlike my Sabahan and Sarawakian friends, I am not exposed enough to the Phillipines. Personally, I won't claim I am an expertabout Filipino people, culture and heritage (and if you are from Phillipines, feel free to DM me, please) but I hope to do justice about our beloved rockerboy in the way he truly deserved. Didn't just make music on that boat. Busted my ass servin' drinks, waitin' tables. Free time, I-I composed till my fingers bled. - Kerry Eurodyne "Boat Song"

#Cyberpunk 2077#Cyberpunk 2077 Essay#Asian Representation#Video Games#Corpo V#Kerry Eurodyne#R. Talsorian Games#Cyberpunk#CD Projekt RED

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

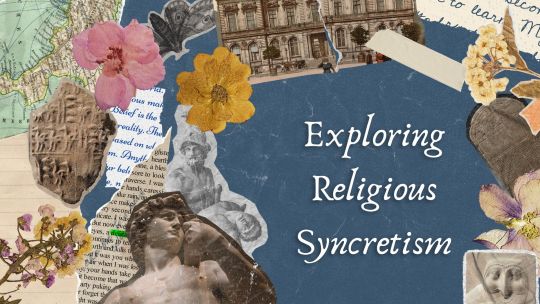

Exploring Religious Syncretism

As-Salam-u-Alaikum wa-rahmatullahi wa-barakatuh (“Peace be unto you and so may the mercy of Allah and his Blessings”)!

Religious syncretism is the practice of blending two or more religious beliefs. This phenomenon has occurred throughout history and has given us a plethora of diverse religious beliefs, rituals, and customs. Religious syncretism often occurs from assimilation and conquest. However, its origins are not always born from negative events; syncretism also comes from cultural exchange, trade, and other peaceful interactions between different religious communities.

The Ancient Origins of Religious Syncretism:

One of the oldest examples of religious syncretism is that of Ishtar. Ishtar was an ancient Mesopotamian goddess of fertility, love, and war. There is a list, known as the “Ishtar Tablet” which lists the names of other goddesses that are syncretic equivalents to Ishtar. Syncretic examples of Ishtar include Innana, Astarte (who is mentioned in the Old Testament and is my cat’s middle name), and Aphrodite.

Key Examples of Religious Syncretism:

Interpretatio Graeca/Interpretatio Romana: Ancient Greece would often try to identify foreign deities by using their own pantheon. Rome would do this same practice, especially with the Celtic pantheon. For example, Sirona is the name of a Celtic goddess. However, she was often paired with Apollo “Apollini et Si/ronae.”

Ancient Egyptian Religion: Syncretism was frequent in ancient Egypt. The god Amun and the god Ra were combined into Amun-Ra. Ancient Egypt would also combine their gods or goddesses with those of neighboring civilizations. For example, Osiris would be combined with Helios or Zeus. Whether the combination is due to religious similarities or political gain is up to historians.

Christmas Trees: Anyone familiar with the Gospels will tell you it never mentions evergreen trees or ornaments or even Santa Clause. However, these are iconic aspects of Christmas season. The Christmas tree finds its roots in pagan religious practices. The evergreen being a symbol of life in a dark, lifeless time.

Challenges and Controversies:

Critics of religious syncretism claim that it raises questions about authenticity, purity, and the preservation of traditional practices. Some religious purists may view syncretic movements as heretical or impure, leading to tensions within religious communities, even going so far as saying religious holidays are “fake” if they are touched by syncretism.

The Significance of Religious Syncretism:

Despite the critics, religious syncretism is still incorporated into most of today’s societies, religious or not. It’s clear in the examples given, but also in the names of the days of the week (Norse paganism), names of some of the months (Roman paganism), the workday/weekend schedule, etc. Ignoring thinks simply because they have been affected by syncretism is, in my opinion, silly.

For those of us trying to find some divine meaning in our lives, syncretism can show us the overlap of everyone’s beliefs. Personally, I always hated the idea that there is only one, chosen group of people that have had the truth revealed to them. The Qur’an tells us the names and stories of some of the prophets, but not all of them. Messengers have been sent to all ends of the Earth, to all people. Their messages just get lost in time and change into different religious beliefs (almost like a giant game of telephone). In my opinion, by seeing the reoccurring themes throughout religions, such is flood stories or “golden rules” that are prevalent in many belief systems, syncretism is just one of the many tools we can use to find the “truth.” Additionally, I personally see syncretism as a way for people to see how their beliefs are not so different from others.

Conclusion:

In a world characterized by globalization and cultural exchange, religious syncretism continues to shape the spiritual landscape, offering a glimpse into the rich tapestry of human belief and practice. By embracing diversity and dialogue, we can appreciate the beauty and complexity of syncretic traditions, fostering mutual understanding and respect across religious boundaries.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rudolf Berthold (Part 3)

Disclaimer: Now starts a part of German (and European) history that is highly controversial. The period shortly before the end of the war and the years afterwards were a mess of revolutions, fighting, terrorism and murder. Opinions of how good/bad it was depend on political/ideological convictions. For the sake of keeping it short, I will simplify and only mention events that are necessary to tell Bertholds story.

During the last month of the war Berthold still had hope that he will be able to return to the front: “I want to go back out to the frontlines! If only I had my healthy bones – but I can still do it. As long as the battle rages everyone with experience belongs out there.” But his health was too unstable for even his iron will to make a return possible. He returned to his home and waited. For what he wasn´t sure.

In November the situation at the front and in Germany worsened and Marine troops started mutinies. Revolutions broke out, inspired by the Bolshevik revolution in Russia. Berthold was a fervent monarchist and held on to his Kaiser and the established social order. “Overthrow! Constitutional change! In a few days, what strong men have built up over centuries will be destroyed. The people have been seduced. Doubts are cast on the army. We're still far in enemy territory and we're supposed to surrender? Madness!”. Bertholds opinion on all that was happening is clear.

After the Armistice in November a semi-civil war broke out in the bigger German cities. Communists, Socialists, Bolsheviks on the left; Nationalists and Monarchists on the right; Social Democrats in the middle. Mix in some Anarchists and foreign agents and the disaster was perfect. The soldiers returning from the front were being pursued by all sides to join. By many they were not treated well, their uniforms were ripped and they were called to throw down their weapons and join the fight against militarism. But many soldiers were still loyal to the emperor and did not want to accept the looming Republic.

Especially at the end of 1918 to early 1919 the communists were very powerful. The left-wing Spartakus movement tried to overthrow the government in Berlin and took over Munich. Separatists in Western Germany called for independence of the Rhineland.

Berthold spend the rest of 1918 depressed at home. He felt angry, devastated and useless but he stayed true to his convictions: “The oath of allegiance I once swore I keep for life. A life that now lies so dark before me!”. But his mood and his perspectives changed when more and more Freikorps units (mostly right-wing paramilitary units, used by the Social Democratic government to defend itself and suppress the communist/Bolshevik uprisings) were established. He saw that there was still fight in some men.

The newly formed Reichswehr (official military of the new German state) offered the Hauptmann an active duty posting at Döberitz Airfield. He soon was back in uniform, training men. His charisma and leadership ability enabled him to even get along with the Worker´s and Soldier´s Councils (that caused a lot of trouble in other places). But shortly after, Berthold was ordered to close the Airfield and dismiss his men. Berthold worried that the ever rising number of unemployment would drive the men towards the Spartakus and similar movements.

When Munich, capital of Bertholds home region, was taken over by Communists in April 1919 and proclaimed a “soviel republic”, several Freikorps from all over of the country came to free it. For Berthold this was a turning point. He saw a purpose again. He now saw an opportunity to keep fighting for his country. He put out a call for young men to join him and form their own Freikorps. Soon he had gathered around 1,200 men for his “Eiserne Schar Berthold”. He trained the mostly very young farmers boys and in August they answered the call to go to the Baltics to fight the Bolsheviks there.

Berthold and his men travelled to Mitau, Lithuania to join with the Eiserne Division (Iron Division). There, Germans and anti-Bolshevik Russian were fighting the Red Army side by side. But also local troops that wanted complete independence and both Germans and Russians out of their country. It was a brutal fight from all sides. Bertholds right hand was still paralyzed, he was not able to join in the active fighting but he rallied and motivated his men with great success. They came into the suburbs of Riga but then it was over. Pressure from the German government to cease fighting and return home as well as strong resistance made it impossible to keep fighting. The Freikorps did not get any new supplies, be it food or weapons; something that even Bertholds iron will and dedication could not substitute.

Starving and their numbers greatly decimated Berthold and his group returned to Germany in December 1919. There it was demanded that the Eiserne Schar be disbanded. Bertold did not agree to this, knowing that there was nothing waiting for him or his loyal fighters. They were ordered to report to several different locations, finally ending up in Harburg (near Hamburg), which was governed by Independent Socialists. During this time a military-backed putsch (“Kapp-Putsch”) to overthrow the Government in Berlin was about to be carried out, with support of Lieutenant-Commander Hermann Erhardt, with a Freikorps of his own.

Berthold was accused of wanting to come to its support and ordered to give up his weapons. Harburg officals ordered the officers of the Reichswehr stationed in the town to be arrested. Tensions rose and Berthold met with town representatives who promised safe accommodations and later on transportation for his troops. He and his men went to make camp in the local school. Local union trade leaders demanded of the Reichswehr soldiers to subdue Berthold but they were ordered to stay out of it. The trade leaders then called for their workers to take up arms against the Eiserne Schar Berthold. The men in the school readied their weapons, including machine guns, to defend themselves against the advancing lynch mob. A fight broke out (it is unclear who fired the first shot). Bertholds men were outnumbered and being fired at from all sides. Many died inside the school. After a while a cease fire was called. Berthold managed to come to an agreement with the local authorities: His men were to give up their arms and then be allowed to leave the city unharmed. But that deal was broken the second a disarmed Berthold and his men stepped out of the school. Some local sympathizers warned Berthold that he will be attacked and should try to sneak out on his own but he refused to leave his men. That was his doom. The men were attacked from all sides the second they stepped out of the school and soon lost sight of their leader. Shortly after one of the attackers called out tauntingly: “There lies your great leader”. The men of the Eiserne Schar Berthold looked towards a street corner where an unrecognizable body lay in the gutter.

Autopsy results:

The captain's blue tunic was completely torn open. There were severe scratch wounds to the neck. Terrible piston blows had shattered the entire top of his skull. Seven shots in the head, left and right chest shots, all from behind. The spine was completely separated.

Bibliography:

Iron Man – Rudolf Berthold: Germany´s indomitable fighter ace of World War I, Peter Kilduff

Kamerad Berthold, Thor Goote

Rudolf Berthold, Ludwig F. Gengler (this book consists mainly of Bertholds diary)

Die Geächteten, Ernst von Salomon

#Rudolf Berthold#Poor Rudi you deserved better#y´all the way I cried when I first read about his death#fuck communists#Weimarer Republik#Weimar Republic#Freikorps#wwi

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Profiles in Courage

In anticipation of the celebration this week of the 248th anniversary our nation’s independence, I undertook to re-read President John Kennedy’s Pulitzer-Prize-winning 1956 bestseller, Profiles in Courage, a book I first encountered when it was assigned to me by Mrs. Gore in my eleventh-grade American history class. If I remember correctly, it impressed me then. But it astounded me now, and in several different ways. Of course, I am more than aware of the widespread belief that the book was substantially written by Theodore Sorensen, at the time a Kennedy speechwriter with a strong interest in American history, and that a good deal of the research that went into the book was undertaken by Jules Davids, a professor of diplomatic history at Georgetown, where he had among his students the young Jackie Kennedy, then still Jacqueline Bouvier. (Sorensen’s remark that he wasn’t the book’s author, merely the guy who wrote “the first draft of most of the book’s chapters” says more than enough.) Of course, I was unaware of any of this when I was in Mrs. Gore’s class and took the book to be the work of our martyred thirty-fifth president, whose memory we all revered and whom we all believed would have gone on to do truly great things if he had lived to the end of a second term in the White House. For better or worse, I will refer here to John Kennedy as the book’s author.

The book itself consists of a series of essays, eight in total, describing acts of moral heroism undertaken at various moment’s in our nation’s history by sitting senators. Most of the senators in question served in the Senate in the decades leading up to the Civil War or in the ones that followed; all are depicted as men who, rather than following the advice of their party or even the wishes of their constituents, chose instead to do what they perceived to be the right thing regardless of the consequences of their actions. These senators, in Kennedy’s opinion, were therefore heroes: men who chose to remain true to their own ideals and who were prepared to pay a big price for doing so.

That notion, of course, was and remains controversial: is the job of elected officials to do what they personally believe to be right or to represent their constituents vigorously and to vote in accordance with the wishes of the people who put them in office specifically to represent them in the Congress? It’s a good question! And it is telling, at least to me, that that specific issue is not debated or even raised really in the pages of the book: for the author, it goes without saying that the job of public officials is always to act in accordance with their own moral code and so to fulfill the “real” reasons anyone is elected to office in the first place: to do good, to promote virtue, to act in the best interests of the people, and to lead the nation forward to (or at least towards) the fulfillment of its national destiny. No more than that, but also no less!

What I liked so much about the book the first time ‘round (i.e., back in eleventh grade), I can’t quite recall. But what struck me this time was how complicated it is to say that politicians who act in accordance with their own values and ideals are always behaving in a praiseworthy manner—and that the corollary, that it is always base and unworthy for politicians to bow to public opinion, including the public opinion of their own constituents, is also true.

A good example would be the case of Senator Robert A. Taft, the son of the twenty-seventh president of the United States and the senator from Ohio from 1939 through 1953. What JFK particularly admired in Taft was his willingness to face nation-wide opprobrium for publicly opposing the Nuremberg Trials of some of the worst Nazi war criminals, to which Taft sneeringly referred as victor’s justice under ex post facto laws. This latter idea—that no one may be tried, let alone executed, for breaking laws that were only enacted after the deed under consideration was done—is a pillar of Western justice. But there was no one in the nation—except for Senator Taft, it seems—who was willing to apply that to the Nazis being tried in Nuremberg, whose crimes against humanity were—at least for most—so beyond the pale of “normal” criminality that the regular rules could not reasonably apply to them. Nor did Taft mince his words on the topic, repeatedly referencing the trials as being far more about vengeance than justice. This could not possibly have been a less popular opinion and he was publicly lambasted both by Republicans and Democrats for daring suggest that there was something intrinsically illegal afoot in Nuremberg and for going so far as to characterize Nuremberg as “a miscarriage of justice that the American people would long regret.” (To read the New York Times article of October 6, 1946 recording the senator’s words, click here.) It is widely believed that this principled opposition to the Nuremberg Trials is what cost Taft the Republican nomination for President in 1952.

JFK admires Taft immensely for knowing what he believed to be right and for repeatedly paying gigantic prices for being true to his own self. (His pre-Pearl-Harbor opposition to US involvement in World War II is widely thought to have cost him the Republican nomination in 1940, which he also didn’t get in 1948 because—or at least probably because—of his isolationist positioning.) I felt myself swept along by Kennedy’s rhetoric too: I couldn’t have agreed with Robert Taft less on most issues, including—possibly most of all—the legitimacy of Nuremberg. And yet I was struck by the portrait of a man with the courage of his convictions, of a man who would simply not lie about how he felt for his own gain.

The other portraits in the book are equally stirring, most of all the portraits of Edmund G. Ross, the senator from Kansas who broke with his party and the large majority of his constituency to vote to acquit at the impeachment trial in the Senate of President Andrew Johnson, and of Lucius Lamar, senator from Mississippi, who alienated huge numbers of his constituents by attempting to re-integrate the South into the Union and by supporting Black suffrage. At this juncture in history, it would probably be a good thing for all Americans to review Kennedy’s book—including those of us who last read it as teenagers. The chapters are a bit uneven (and some presume a familiarity with American history that will not correspond to what most readers will bring along to their encounter with the book), but the book’s basic argument—that our nation has been blessed over the centuries to have among its leaders people whose devotion to their own ideals and principles was ironclad and unshakeable—is something American would do well to consider and reconsider as we wrap up the first quarter of this century and move on into the second.

We have evolved a system in which we esteem above all else flexibility of opinion and elasticity of conviction. We hail as our greats individuals who get things done, who are effective and energetic, who know how to compromise. And we specifically do not admire people who refuse to go along with the majority, who insist on sticking to their opinions no matter what the consequences, who don’t mind being widely reviled if such is the price for being true their personal convictions. Indeed, the notion itself that the job of senators and members of the House is to embody their own virtues rather than invariably to act in accordance with the opinions of their constituents is probably the opposite of what most people think. And that is what makes President Kennedy’s book so challenging and so interesting—because, in the end, the book is a provocative argument that democracy needs leaders with vision and virtue, not ones who see their job as simply doing what they are told by the voters. In turn, this question leads to others. With whom should the ultimate power rest in a democracy—with the people (who are, after all, the demos in democracy) or with its leaders, chose precisely because of their vision and personal philosophy? How should history judge those who claim to believe in democracy but who—like JFK, apparently—ultimately hail as heroes elected officials who refuse to obey the wishes of the people who put them office? What does it even mean to lead a nation, for that matter: to do as the people demand or to inspire them to want what you feel is in their own best interests? Is that paternalism or leadership? Does hoi polloi get the final vote? Or is putting that kind of power in the hands of the masses precisely what leads to Nazism and Maoism? These are the questions that Profiles in Courage awakened in me as we approach the nation’s semiquincentennial in just two years. Are our leaders supposed to lead or be led? Do the people have the final word? Or is their job to put in place leaders whose sense of allegiance to their own virtues and values will lead the nation forward to its destiny? These are all excellent questions…and one more timely than the next!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Algorithms is why Twitter sucks and is bad for mankind. My timeline gets flooded with the most brain dead and controversial tweets you can imagine because they have high engagement, are tangentually related to my interests, because someone I follow follows these idiots, or even just because this person wrote a response to a person who the algorithm thinks I would like. Just giving a fav to a guy because I like one of their tweets even once can doom my feed. Most if it is culture war garbage too. And sometimes I am stupid and engage.

I swear to God it will be the end of civilization, and the people who come after us will have religious commandments against this nonsense.

No, I am not interested in WhiteHeritage1488's opinions on race, genetics and non european history. Hahaha, 13/50 and mud hut jokes, very funny and original. I don't want to see TradMemes✝️ reach Reddit atheist levels of cringe. Not yet sick enough from people blaming every ill of the world on "(((them)))" or "muh capitalism"? Have some more! I am annoyed at seeing the 36796th Twitter communist justify mass violence, slander my country and post their sad nazi and Elon memes. Don't even begin with all the Elon tweets. I am also very much tired of witnessing interesting and cool posts vanish from my timeline in front of my very eyes.

It's such garbage.

I don't care if guys I follow like meme, drama, ultra tradcon or delusional race baiting commie accounts, but there are other, more fun, educational and less stressfull vectors I can use to engage with all the above topics if I want to. Twitter is not one of those, and probbably neither is tumblr. I don't need to see these things here or there. Keep stuff I don't request or from peoole I don't actively follow away from me.

HEY. @staff LISTEN TO US. LISTEN TO YOUR LOYAL USERS. DO. NOT. I REPEAT DO NOT GIVE THIS SITE AN ALGORITHM.

the whole reason I use this site is because it DOESNT have one. PLEASE. I swear you will lose half your user base if not more.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

US Lt General Ulysses S. Grant’s strategy to defeat Gen. Lee’s Confederate army during the Wilderness Campaign of 1864:

#american civil war#ulysses s grant#american history#zapp brannigan#futurama#i actually cannot stand certain Union generals#people put up statues of Robert E Lee because he was genuinely loved and respected#nobody out up statues of Grant or Sherman because they were butchers and nobody liked them#also if we’re tearing down statues of Lee we should get rid of anything honoring Tecumsah Sherman cuz he was a violent racist#sorry but there it is#my controversial civil war history opinion#disclaimer: I’m not pro-confederacy#i’m just saying just cuz certain people were on the ‘good’ side doesn’t mean they were good themselves#and vice versa

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Traitor of Atlas: In history class in beacon Professor Oobleck is teaching the class about the traitor and has the class decide whether he’s a good guy or not which ends up dividing the class

A Matter of Differing Perspectives

Weiss: He’s a villian!

Blake: He’s a hero!

Weiss: He betrayed his kingdom, and killed his fellow countrymen!

Blake: To save innocent faunas who were about to be slaughtered by, Atlas forces for just being faunas!

Oobaleck: Settle down children, settle down. While you both make good points, you miss onw of the key aspects upon why, Jaune Arc is seen as such a controversial character. Ms. Nikos, do you know what that one things is?

Pyrrha: The fact he was considered a villain, and a hero before he betrayed, Atlas?

Oobaleck: Correct! Prior before his betrayal he was considered a hero by the forces of, Atlas, and a villain to those that opposed them. Thus resulting in him developing a rather uncertain stance in public opinion. For he is considered a hero, villain, and neither, based upon whom you talk to. But nonetheless, he is an individual who is regarded in high esteem by both of them, but not for what he didnthat day. Can any students care to guess why?

Ruby: Oh! I know, I know!

Oobaleck: Yes, Ms. Rose?

Ruby: He is held in high regard because of his tactical brilliance, and his skill as a huntsman.

Oobaleck: Correct! But, why is that, Ms. Schnee.

Weiss: The tactics he created, and pioneered during the war are the bases of many current military doctrine used by the Atlas military. Many of the battles are in fact taught to students of Atlas Academy. Mostly to those that decide to join the military, than become Hunters.

Oobaleck: Correct. His strategies were the tide changers in many a battle. In fact, before he joined Atlas’s war effort they were losing, badly. After he joined, Atlas, and Mistral started winning and were pushing, the forces of, Vale, Vacuo, and their faunas allies back. When he defected to the faunas, this stance in the war quickly, and harsh changed in the other direction.

Ren: Would Atlas, and Mistral won the war if he didn’t defect?

Oobaleck: While, it unsure for certain what would have happened, many scholars and military theorist do agree that, Atlas would have won the war. This is based on the simple fact of how easily the tide of war changed, whether or not he was directly involved in a battle. At the end of the day class, whatever, Mr. Arc’s position is in the public eye, it is based upon your personal opinion. Of which, there is one students opinion, I’m sure we would all like to hear about; Ms. Arc?

Jeanne: M-M-Me?!

Oobaleck: Yes you, Ms. Arc. Would you like to tell the class what your personal opinion about your older brother is?

Jeanne: Uhhh… No…?

Oobaleck, ‘No?’ And, why is that?

Jeanne: I was only around five, since I last saw my brother. And, it wasn’t until years later I was able to comprehend what my brother did. And, there are… other reasons why I can’t really express my opinion…

Oobaleck: And, those are?

… : Probably because of how our dad reacted the last time we talk. That was… civil…

Oobaleck: Excuse me, who are…?! W-What are you doing here?!

Jaune: Excuse the interruption, Professor. I came looking for my students to see how they were doing. Then I just so happened to stumble across a history class talking about me, a rather surreal experience in all honesty. However, I found someone far more interesting than all of that in the end. Hello, Jeanne.

Jeanne: Jaune…?

Jaune: I don’t mean to be rude, but may I talk to my sister? Privately of course.

Oobaleck: Of course; if Ms. Arc is…?!

Jeanne: L-Let’s go to my room! N-Now!

Jaune: Huw? Okay. I shall take my leave then; again, sorry for interrupting your lesson. Have fun kids!

Weiss: T-That’s the Traitor…?

Pyrrha: He seems rather… normal?

Nora: Do you think I could take him?

Ren: I’m not sure, Jeanne would like it if you attacked her older brother.

Ruby: Where’s the cape?! I heard he had a cape! Hero’s need to have a cape!

Yang: And, who didn’t mention that he was fucking hot! Why didn’t you say he was hot, Blake?!

Blake: I refuse to answer that…