#mutoscope

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

‘Show off!’

Artist: Howard Connolly

Source: ‘International Mutoscope Reel Company’ (1941)

#pin up style#pin up art#pin up cartoon#good girl art#pulp art#pulp style#Mutoscope#Card#Poster#Howard Connolly#WW2#1940s#1941

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

via @blackmancruz

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Sherlock Holmes Baffled" Mutoscope silent film, earliest known film to feature Sherlock Holmes (1900, Arthur Marvin)

#tfw an androgynous stranger puts your doohickeys in a bag#sherlock holmes#sherlock holmes baffled#other#silent film#holmes#sherlock holmes film#silent movie#mutoscope#arthur marvin#1900#1900 film#early film#short film#internet archive

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pin-Up Girl Card Dispenser - "World's Fair Postcard Vender" by International Mutoscope Reel Co.

Maple case with decorated sides and maker's plaque at the top. Inset behind glass "A Machine Full Of Glorified Glamour Girls" above three sample cards and "You Will Require A Complete Set For Your Private Collection" followed by the vending instructions for obtaining the 1¢ cards.

Source: Hanover, MA Eldred's

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

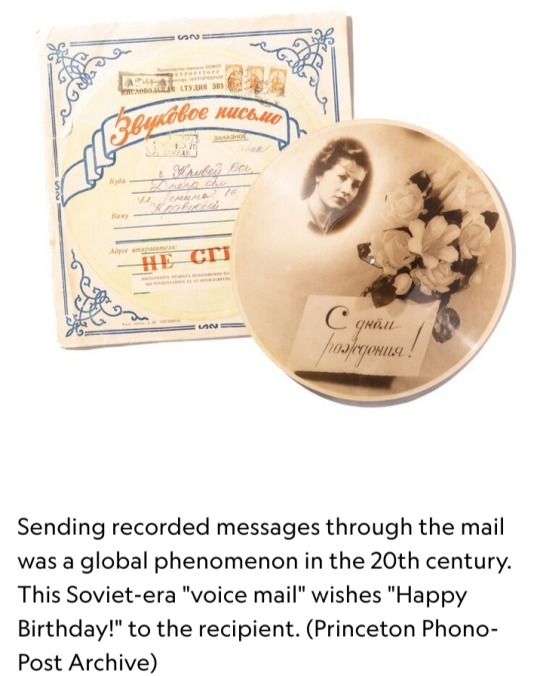

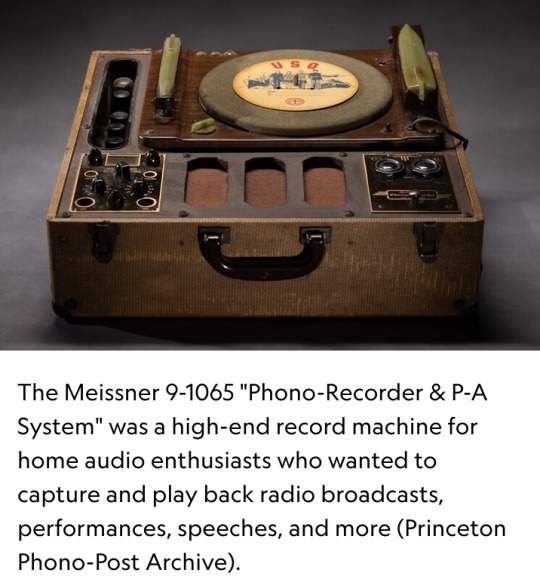

“Hello Mother, Dad, and Blanche,” a quiet voice says above the cracks and pops of an old vinyl record, which has clearly been played many times over.

“How’s everything at home? I’m recording this from Dallas…from this very little place where there are pinball machines and many other things like that…”

The disc is small, seven inches across, dated October 1954.

The faded green label shows that the speaker’s name is “Gene,” the recording addressed to “Folks.”

Gene suggests in his minute-long message that he is traveling — “seeing America” — and tells his family not to worry about him.

“I should complete my trip sometime around Thanksgiving,” he continues in a second recording made in Hot Springs, Texas, not too long after his first one.

“I hope you received my letter and I, in turn, hope to receive some of the letters that you sent me. It’s been a very long time since we’ve corresponded, and I’m looking forward to hearing from you very, very much.”

This largely forgotten sound is one of the world’s early “voice mails.”

During the first half of the 20th century, these audio letters and other messages were recorded largely in booths, pressed onto metal discs and vinyl records, and mailed in places all over the world.

Best known today for playing music at home, record players were then being used as a means of communication over long distances.

Reach out and touch someone

The idea of transporting a person’s voice had loomed large in the human imagination for some three centuries before it was finally achieved with the invention of the phonograph in the late 19th century.

Historical documents from the Qing Dynasty in 16th-century China suggest the existence of a mysterious device called the “thousand-mile speaker,” a wooden cylinder that could be spoken into and sealed, such that the recipient could still hear the reverberations when opening it back up.

Top: A Kodisk horn and recording stylus attachment in the Princeton Phono-Post Archive was used in the early 1920s for home recordings on pre-grooved blank metal discs using a normal gramophone.

Bottom: A Gem Recordmaker attachment at the Princeton Phono-Post Archive was used in the 1950s for children to "make your own permanent records" on blank six-inch discs using their own gramophone at home.

When Thomas Edison invented the phonograph in 1877, he envisioned a device that could reproduce music and even preserve languages.

He saw, in its earliest uses, the potential to transform business, education, and timekeeping.

He even imagined a so-called “Family Record” — a “registry of sayings, reminiscences, etc., by members of a family in their own voices and of the last words of dying persons.”

But correspondence was at the top of his mind: Edison thought his invention could be used for dictation and letter writing.

In the late 19th century, handwritten letters were the most common form of everyday personal communication.

The telegram, which later became popular in the early 1900s, was used for shorter, urgent messages.

While Alexander Graham Bell made the first transcontinental telephone call from New York to San Francisco in 1915, long-distance calling remained expensive and inaccessible to most ordinary people until the 1950s.

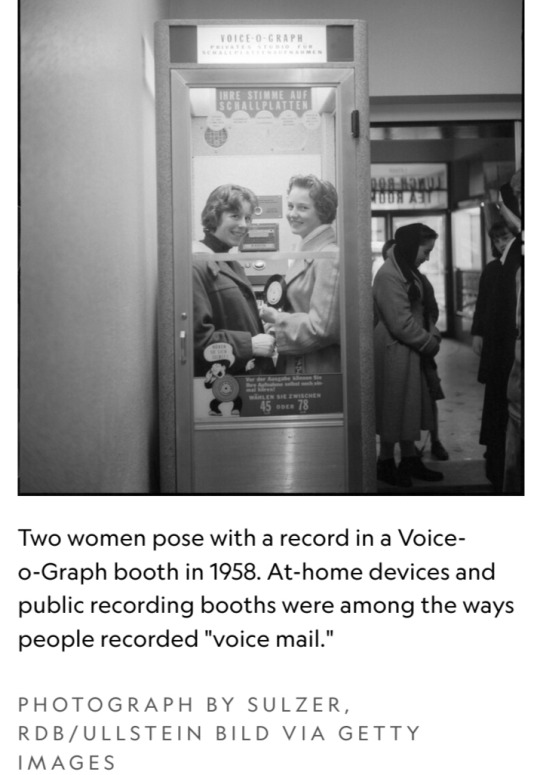

Voice-O-Graph

The gramophone, a later form of the phonograph developed by Emile Berliner in 1887, provided a first possibility for recorded sound being used for long distance communication.

It made recording and playback possible on discs, which were easier to store, reproduce, and send.

The earliest known record to have been put in the mail as a means of correspondence would be sent in the early 1920s, but the practice of sending voice mail really got going across the world in the 1930s and 1940s.

It was personal and affordable as long as customers could find a recording booth or home device.

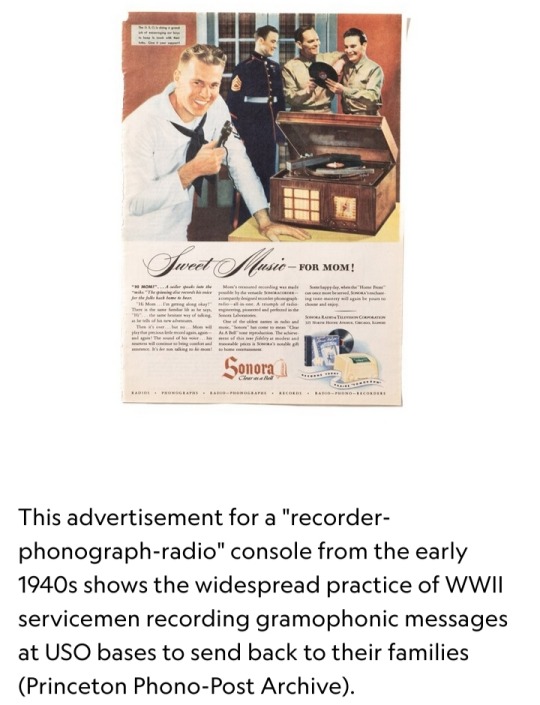

In the early 1940s, the American company Mutoscope rolled out the Voice-O-Graph machine, which vastly popularized voice mail in the United States.

It was a tall wooden cabinet, shaped not unlike a modern-day photo booth, that declared, on one side: RECORD YOUR OWN VOICE!

Invented by Alexander Lissiansky, these recording booths were marketed as novelties and set up at common gathering places: amusement parks, boardwalks, tourist attractions, transportation hubs, military bases and U.S.O. events.

There was a Voice-O-Graph machine at the top of the Empire State Building, on the piers of San Francisco, and by the Mississippi River in New Orleans.

The speaker entered the Voice-O-Graph, inserted a couple of coins, and had a few minutes to record a message.

Then, out popped a record the size of a 45-rpm single that was not only durable enough to be played multiple times, but also flimsy and lightweight enough to send in the mail for little more than the cost of a regular letter.

Oftentimes, the envelopes themselves would come included.

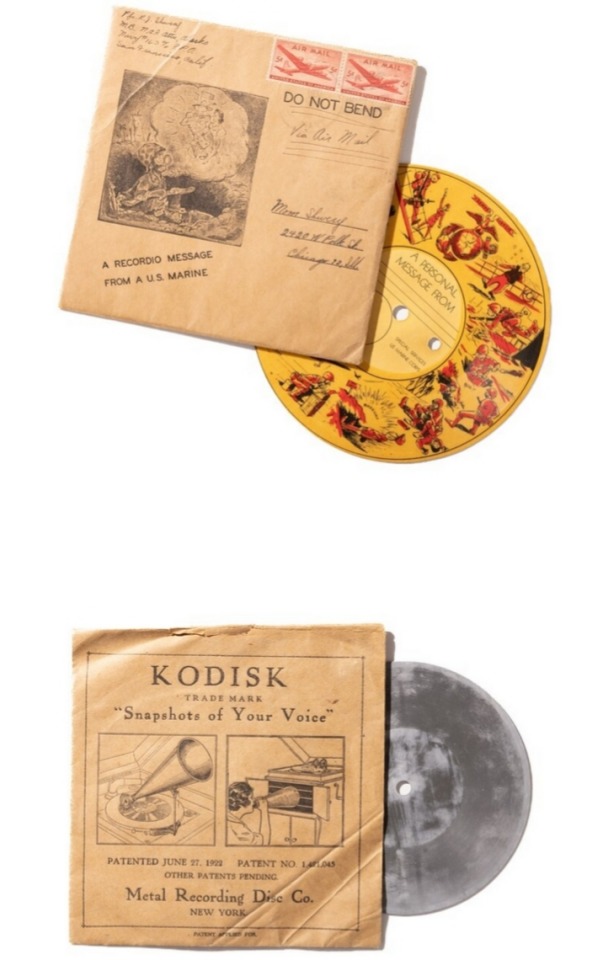

Top: A soldier sends a Christmas greeting to his mother in Chicago.

The envelope, which came with the record, depicts a soldier anxiously imagining his wife with another man in his absence (Princeton Phono-Post Archive).

Bottom: Pre-grooved metal discs were used for domestic gramophone recordings in the early 1920s.

The paper sleeve illustrates the two methods of recording: one, depicted on the right, involved using a megaphone to shout into the phonograph's horn; the other method, depicted on the left, involved using a Kodisk-branded external horn and recording stylus, which would be attached to one's home gramophone and is shown in another image above (Princeton Phono-Post Archive).

Top: A “Recordio” home-recording demonstration disc from the 1940s illustrating five different models of radio-recording-playback consoles made by the Wilcox-Gay Corporation, ranging from massive living-room consoles to portable “airplane type” suitcase versions (Princeton Phono-Post Archive).

Bottom: Wilcox-Gay Recordio demonstration picture disc featuring the violinist and radio star David Rubinoff (1897-1986) and his $100,000 Stradivarius making a recording at home (Princeton Phono-Post Archive).

Photographs by Rebecca Hale, NGM Staff

Words of love

The messages people sent would range in emotion — from excitement to nervousness, joy to embarrassment.

Travelers would make recordings to update family and friends on long trips.

Especially during World War II, where there were recording booths on military bases in nearly every theater of the conflict, soldiers used voice mail to reassure loved ones with the sound of their voice, even if some them would never return home.

There are countless “voice mail valentines,” surprisingly intimate audio love letters.

Many of the messages, sent from far away, express longing.

“You keep your chin up,” a voice named Leland tells his wife in a recording dated 1945, from a booth in New York City.

“All of you keep those chins up. Mike, all of us will all be home, be home where we can pick up, and carry on as we did before.”

In one recording made in Argentina in the 1940s, a man plays the violin before he recites a lullaby.

“Sleep, sleep my darling girl,” the man says. “It’s getting late.”

Phono-Post archive

Back then, families could listen to the messages on repeat — gathering together around the record player whenever one arrived.

They could play it proudly again anytime there were guests, but with each play, the needle would scrape away at the delicate grooves until the message could hardly be heard any longer.

Today at Princeton University, professor and media theorist Thomas Levin is dedicated to preserving these sounds of the past.

He maintains the world’s only archive dedicated to what he calls the “Phono-Post.”

At the height of the phenomenon, there were perhaps thousands of Voice-O-Graph machines in America and many more recording stations across the world.

“Millions of these audio letters were sent across the United States, South America, in Europe, in Russia, in China,” Levin says.

Levin’s office is crammed with many of the items he has collected over the years, including books, posters, and other ephemera—as well as, of course, the records themselves.

Levin has already digitized some 3,000 of the discs, all of which are tucked into clear plastic sleeves and carefully catalogued.

He keeps them filed into cabinets and stackable storage bins in a temperature-controlled room.

Thousands more records lie waiting to be processed in a nearly seven-year backlog that keeps growing as Levin continues collecting.

He employs AI bots that constantly comb through eBay pages and bid for items on his behalf.

Sometimes, he will come across people selling, knowingly or unknowingly, the voice of a relative.

“I write to them and I say, you��re selling the voice of your grandfather?’” Levin says.

“There’s not a sense of the value of the voice, such that people are willing to part with these objects.”

Still, he offers to share an MP3 file of the recording with them, and for that, they are often very grateful.

Voices of the Past

For the most part, there aren’t many celebrity voices stashed away in the Princeton Phono-Post Archive.

“The bulk of the recordings in this archive are of very unextraordinary people articulating desires, wishes, fantasies, of a very quotidian sort,” Levin says.

They are enormously telling, if one is willing to listen closely.

Much like paper letters, these audio missives can also reveal insights about particular moments in history through the accounts of individual lives lived within them, but with added layers of sensory detail.

Historical linguists are particularly interested in “voice mail” because it provides some of the earliest-ever recorded samples of how regular people spoke — their conversational vocabulary, their pronunciation and accents, their sentence structure, their intonation.

“There’s no editing. There’s no cleaning up,” Levin says. “Once the recording starts, it will run until it ends, whether you have something to say or not.”

He smiled. “If you don’t have anything to say, that says something too.”

The advent of cassette tapes in the 1960s meant that services like the Voice-O-Graph quickly fell out of fashion.

(For a few decades, people were sending long distance messages on audiocassettes, too — a practice that became particularly common for U.S. soldiers deployed in the Vietnam War.)

But this voice mail phenomenon, while short-lived, holds a significant place in the history of global communication.

“What we’re recovering now are the remnants of a chapter of media history, a cultural practice, that was huge, ubiquitous,” Levin says, “but has now been forgotten.”

For many people, these recordings were the first time they had ever recorded their own voice.

They sound nervous, even awkward, while others even sound like they are reading from a piece of paper.

Some, when faced with their very first self-recording, confronted the realization that they were leaving a highly personal trace that would likely outlive them.

“People strangely, but with remarkable regularity, talk about death,” Levin says.

“They’re writing to a future.” He pauses. “And one thing is known about that future: that they will not be a part of it.”

#voice mails#audio letters#old vinyl record#record players#phonograph#Thomas Edison#telegram#handwritten letters#Alexander Graham Bell#gramophone#Emile Berliner#Mutoscope#Voice-O-Graph#Alexander Lissiansky#Phono-Post#Princeton Phono-Post Archive#Historical linguists#cassette tapes#National Geographic

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mutoscopes en Californie, 1942. Un mutoscope est un appareil qui permet de visionner des images animées à partir de cartes photographiques disposées en cercle sur un tambour rotatif. L’utilisateur tourne une manivelle pour faire défiler les images et créer l’illusion du mouvement. Le mutoscope a été inventé en 1895. Il était très populaire dans les foires et les parcs d’attractions. Il est considéré comme l’un des ancêtres du cinéma.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

American Mutoscope card by The Brown & Bigelow Calendar Company. Image by Zoë Mozert.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another couple of background characters in Tron that I think are funny is the old man and woman visiting Flynn's Arcade, all dressed up in fancy clothes, sticking out among all the sweaty youngsters. Did they decide to have an evening at this new-fangled "video arcade" they had heard so much about, and didn't realize that it was a "casual dress" environment? Are they parents looking for their kid in the crowd? Maybe Flynn bought an old arcade with a long history, stretching back to the days of pinball, love testers, mutoscopes and other such non-electronic arcade entertainments, and this couple has visited the same spot ever since their youth, and are happy to see that their old haunt is still popular?

My craziest theory is that they're actually Alan and Lora time-travelling from the future, visiting on the day that would turn out to be so important for them.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 1: Secondary Research & my Idea.

These are some of the different artists I was looking at during the week.

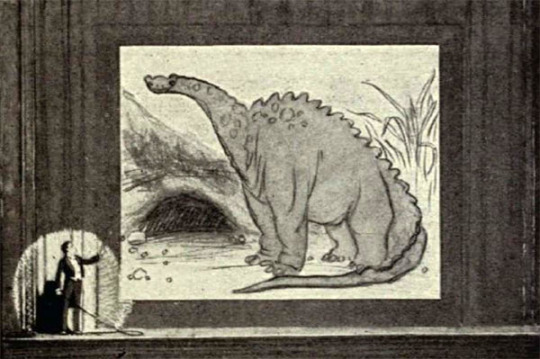

This is Stuart Blackton, the first person to use pixilation and the creator of the "the enchanted mirror". He would "interact" with the drawing, even "removing" parts of the drawing and making them "reappear" as real objects, and would make the face "react". He would stop the recording, make his changes, and continue as before.

This here is Windsor McCay, american cartoonist who created "Gertie the dinosaur", the earliest cartoon to ever feature a dinosaur. This was also the first film to ever use Keyframes, Registration marks, Tracing paper, Animation loops, and Mutoscope action viewer. He would similarly interact with the animation, "throwing" an apple onto the screen and pocketing it when no one looked while an "apple" would appear on the screen, or he would walk behind the stage and "reappear" on screen and ride Gertie.

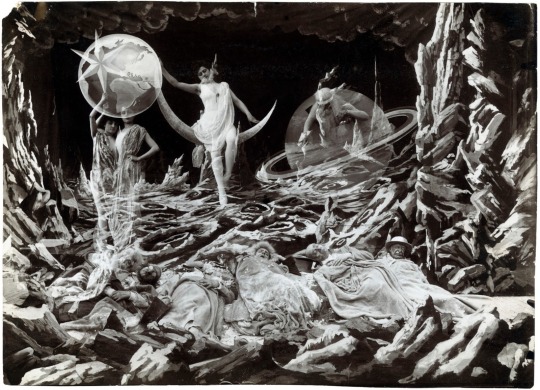

Georges meileis "trip to the moon (1902)", the first film to use Double exposure, Stop motion, and Slow motion. He was a illusionist film maker and a magician. The film took 3 months to make and was filmed in a greenhouse like building to get as much light as possible.

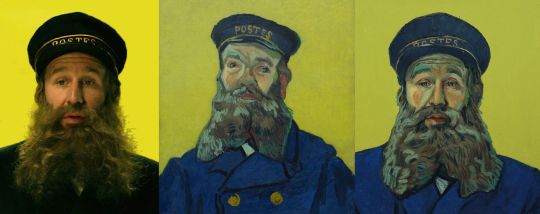

"Loving Vincent" directed by Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman, the worlds first fully painted film with over 65,000 frames. The they would record the actors dressed as their characters , and would use a projector to project the frames from the video onto the canvases and the animators would paint each frame in Van Gogh's art style.

I briefly looked at Jan Svankmajers "Darkness light Darkness", its a very peculiar piece of media, and it is a 7 minute clay stop motion animation. Its just a body reconstructing itself in a miniature house and figuring out where everything goes.

How does this relate to my project?

Well my idea is to create a mixed media short film based in a haunted art gallery/museum ( some place with a lot of artwork) with a security guard monitoring the building and the strange occurrences within its walls. The main focus will be the different security cameras, which will be changing perspectives a lot, and even the p.o.v of the guard. The centerpiece will be an an animation of a portrait crawling out of the frame, but the first part of the animation will be painted like in "Loving Vincent", but as the creature begins to leave the frame it transforms into stop motion animation with clay. I was thinking that since the creature is made of paint it would make a wet sound when it moves, which is where I want to incorporate foley sound, and leave traces of itself around the building. In the background I want to create other spooky visuals like other paintings distorting or objects from paintings disapearing and showing up in the wrong places like in "The enchanted mirror". I want to experiment with different Camera trick to create different visuals and create suspense like the dutch tilt. I want to slowly unnerve the viewer, using different visual affects and changes in each camera.

There's a lot of work to be done and I'm looking forward to see how I'll incorporate the different workshops into it too

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Things that will probably interest only me but resulted in an impromptu little excited chat to 4 mildly interested passersby at a random arcade museum: found roughly 20 fully functional Mutoscopes + Kinetoscopes and offbrand copycats!!!!

6 notes

·

View notes

Video

"The padlock was my own idea" Mutoscope card by Zoë Mozert by totallymystified

#Zoë Mozert#artist#illustrator#illustration#pin-up#showgirl#Mutoscope#card#retro#vintage#nostalgia#flickr

1 note

·

View note

Text

Mutoscope from the last century with an adult girlie reel!

This is just amazing!

Original photos and video are from Walter Chaw on X

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Per the EMI YouTube page…

‘This 'Mutoscope' was commissioned by the German branch of the Gramophone Company, and sent to the London branch in October 1900.

It comprises 700 photographs mounted onto cards and attached to a drum wheel, when the drum is turned in a 'What The Butler Saw' type of machine, it gives the impression of movement.

The film shows one gentleman preparing a gramophone while another watches. These gentleman are said to be Theodore Birnbaum, then Manager of the Berlin Sales Branch and Sinkler Darby, one of the Gramophone Company's recording experts based in Germany.

Soon Nipper appears and starts to howl at the sound coming out of the gramophone. The men watch on in amusement and then lift up the dog - with hilarious results! This table model mutoscope machine complete with the Nipper film were still at the company's office in the 1960s, but disappeared when the record factory moved to Uxbridge Road.

Happily, the mutoscope drum - albeit without the machine - has since been returned to the EMI Archive Trust. The film was on display at the EMI Centenary Exhibition in 1997.’

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

1901 - Boys diving, Honolulu - Robert Kates Bonine (American Mutoscope & Biograph). Films from the prehistory of Cinema. Watch and subscribe to the Channel's notifications! Os filmes da pré-história do Cinema. Assista e marque as notificações do Canal! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WT_O-DcPfOY

0 notes