#morton cushman

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Fancast for a Broadway version of The First Wives Club

Brenda Cushman. Idina Menzel.

Elise Eliot. Annaleigh Ashford.

Annie Paradis. Sutton Foster

Gunilla Garson Goldberg. Bonnie Langford.

Shelly Stewart. Emily Osment.

Morton Cushman. Adam Sandler.

Aaron Paradis. Patrick Wilson.

Leslie Rosen. Amanda Seyfried.

Bill Atchison. Cheyenne Jackson.

Phoebe LaVelle. Sophia Anne Caruso.

Catherine MacDuggan. Diane Keaton.

Cynthia Swann. Stephanie J Block

Chris Paradis. Olivia Holt.

Carmine Morelli. Mandy Patinkin.

#broadway#the first wives club#brenda cushman#idina menzel#elise eliot#annaleigh ashford#annie paradis#sutton foster#gunilla garson goldberg#bonnie langford#shelly stewart#emily osment#morton cushman#adam sandler#aaron paradis#patrick wilson#leslie rosen#amanda seyfried#bill atchison#cheyenne jackson#phoebe lavelle#sophia anne caruso#catherine macduggan#diane keaton#cynthia swann#stephanie j block#chris paradis#olivia holt#carmine morelli#mandy patinkin

0 notes

Text

Lewis Morrison (September 4, 1844 – August 18, 1906) was a Jamaican-born stage actor and theatrical manager, born Moritz (or Morris) W. Morris. He was of English, Spanish, Jewish, and African ancestry. He was known for his portrayal of Mephistopheles in his production of Faust, which he performed from 1885 to 1906.

He became a stage actor using the name Lewis Morrison. He first performed in New Orleans beginning in minor roles with Edwin Booth and Charlotte Cushman until he was featured in larger parts. He became a well-known actor in New Orleans and moved on to the stage in New York, where he gained greater fame in Faust. He founded his traveling theater troupe and traveled the world playing the role of Mephistopheles.

He was married first to Anglo-American actress Rose Wood. He was the father of actresses Rosabel Morrison and Adrienne Morrison; grandfather of actresses Constance, Barbara, and Joan Bennett; and great-grandfather of television talk show host Morton Downey Jr.

He and Rose Wood were divorced in 1890. He married the much younger stage actress Florence Roberts in 1892. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

0 notes

Text

After years of helping their hubbies climb the ladder of success, three mid-life Manhattanites have been dumped for a newer, curvier model. But the trio is determined to turn their pain into gain. They come up with a cleverly devious plan to hit their exes where it really hurts – in the wallet! Credits: TheMovieDb. Film Cast: Elise Elliot Atchison: Goldie Hawn Brenda Morelli Cushman: Bette Midler Annie MacDuggan Paradis: Diane Keaton Gunilla Garson Goldberg: Maggie Smith Shelly Stewart: Sarah Jessica Parker Morton Cushman: Dan Hedaya Cynthia Swann Griffin: Stockard Channing Bill Atchison: Victor Garber Aaron Paradis: Stephen Collins Phoebe LaVelle: Elizabeth Berkley Dr. Leslie Rosen: Marcia Gay Harden Duarto Feliz: Bronson Pinchot Chris Paradis: Jennifer Dundas Catherine MacDuggan: Eileen Heckart Uncle Carmine Morelli: Philip Bosco Dr. Morris Packman: Rob Reiner Gill Griffin: James Naughton Jason Cushman: Ari Greenberg Ivana Trump: Ivana Trump Kathie Lee Gifford: Kathie Lee Gifford Gloria Steinem: Gloria Steinem Elise’s Fan: Lea DeLaria Jilted Lover: Debra Monk Woman in Bed: Kate Burton Brett Artounian: Timothy Olyphant Federal Marshall: J.K. Simmons Young Brenda: Michele Brilliant Young Elise: Dina Spybey-Waters Young Annie: Adria Tennor Young Cynthia: Juliehera DeStefano Miss Sullivan: J. Smith-Cameron Eric Loest: Mark Nelson Gil’s New Wife: Heather Locklear Security Guard: Richard Council Film Crew: Producer: Scott Rudin Set Decoration: Leslie E. Rollins Second Unit Director: Jack Gill Director of Photography: Donald E. Thorin Editor: John Bloom Associate Editor: Antonia Van Drimmelen Casting: Ilene Starger Costume Design: Theoni V. Aldredge Music Supervisor: Marc Shaiman Production Design: Peter S. Larkin Associate Producer: Craig Perry Production Manager: Ezra Swerdlow Makeup Artist: Angela Levin Director: Hugh Wilson Screenplay: Robert Harling Hairstylist: Alan D’Angerio Assistant Art Director: Ed Check Art Direction: Charley Beal Choreographer: Patricia Birch Executive Producer: Adam Schroeder Camera Operator: Rob Hahn Casting Assistant: Kim Miscia Post Production Supervisor: Tod Scott Brody Sound Re-Recording Mixer: Lee Dichter Production Coordinator: Ray Angelic Sound Editor: Richard P. Cirincione Hairstylist: Frances Mathias Storyboard Artist: Brick Mason Construction Coordinator: Ron Petagna Makeup Artist: Bernadette Mazur Sound Editor: Laura Civiello Boom Operator: John Fundus Sound Mixer: Peter F. Kurland Location Manager: Joseph E. Iberti Assistant Art Director: Paul D. Kelly Negative Cutter: Noëlle Penraat Costume Supervisor: Hartsell Taylor Music Editor: Nic Ratner Special Effects Coordinator: Matt Vogel Costume Supervisor: Michael Adkins Still Photographer: Andrew D. Schwartz ADR Editor: Kenton Jakub Sound Editor: Eytan Mirsky Supervising Sound Editor: Maurice Schell Chief Lighting Technician: Jerry DeBlau Hairstylist: Werner Sherer Makeup Artist: E. Thomas Case Hairstylist: Robert Ramos Foley Editor: Bruce Kitzmeyer First Assistant Director: Michael E. Steele Script Supervisor: Shari L. Carpenter Music Editor: Nicholas Meyers Unit Publicist: Eric Myers Music Programmer: Nick Vidar Second Assistant Director: Julie A. Bloom Art Department Coordinator: Julia G. Hickman Transportation Captain: Steven R. Hammond Stunt Double: Joni Avery Transportation Co-Captain: Tom Heilig Color Timer: Tom Salvatore Cableman: Tommy Louie Co-Producer: Thomas A. Imperato Novel: Olivia Goldsmith Associate Producer: Heather Neely Associate Producer: Noah Ackerman Property Master: Octavio Molina Storyboard Artist: Lorenzo Contessa Makeup Artist: Marilyn Carbone Assistant Costume Designer: Wallace G. Lane Jr. Assistant Sound Editor: Jay Kessel Foley Editor: Stuart Stanley Movie Reviews:

#based on novel or book#Divorce#divorced woman#lgbt interest#reunited friends#Revenge#Top Rated Movies

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Until 1857, legal marriage in England was defined by its effective indissolubility, since divorce with the right to remarry was prohibitively complicated and expensive. The law of marriage also mandated the formal inequality of husbands and wives, since coverture dictated that they were legally one person, the husband. Serious reform of those laws began when Barbara Leigh Smith submitted a petition to Parliament in 1856, requesting a change to the laws governing married women’s property, which belonged entirely to husbands unless protected by the law of equity. Although that petition’s immediate success was only partial, it influenced politicians to create a civil divorce law the following year.

Eager to collect signatures from women who were not married to men and were therefore considered disinterested supporters of reform, Smith ended up soliciting signatures from several women who at some point in their lives were in female couples, including Isa Blagden, Geraldine Jewsbury, Amelia Edwards, Charlotte Cushman, and Matilda Hays. That a number of women more interested in relationships with women than in marriage to men signed a petition calling for a Married Women’s Property Act suggests an affinity Smith may not have anticipated between same-sex relationships and marriage reform, one that cannot simply be explained in terms of a feminist desire to increase the rights of all women.

Hays had always been a feminist, and she remained one well after signing the 1856 petition, but her support for divorce also stemmed from her experience with female marriage. When her relationship with Cushman ended in 1857, Hays returned to her feminist circle in London, where she helped run the English Woman’s Journal and the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women, and eventually formed another relationship with Theodosia, Dowager Lady Monson. She also supported herself as a translator and writer, and her novel Adrienne Hope (1866) included characters based on herself and Lady Monson, Miss Reay and her constant companion, the solicitous, widowed Lady Morton. Miss Reay declares her support for women’s rights and notes, “Until quite lately a married woman was only a chattel . . . absolutely belonging to her husband. . . . The new Divorce Court has mended this state of things.”

In an earlier work, Helen Stanley: A Tale, one character makes a didactic speech arguing that divorce is a valid solution to the problem of marital unhappiness and daringly asserting that one could love more than once. In her political and literary work, Hays developed practical and ethical underpinnings for divorce by working to increase women’s economic autonomy and by countering the pervasive accusation that divorce licensed a purely carnal promiscuity. Hays’s feminist vision of laws that would give women legally married to men more freedom incorporated the definition of marriage she had developed in forming and ending her own female marriage.

Although women in a female marriage did not have the benefit of a legally recognized union, they already enjoyed two of the privileges that women married to men fought for over the course of the century: independent rights to their income and property, and the freedom to dissolve their relationships and form new ones. They also created unions that did not depend on sexual difference, gender hierarchy, or biological reproduction for their underpinnings, as most Victorian marriages between men and women did in legal theory if not in social fact. Like many who supported new divorce or property rights for wives, Hays asserted that marriage could and should be based on the equality and similarity of spouses.

As we will see in the next section, “contract” was the term that summed up the view that legal, opposite-sex marriage should be dissoluble and grant equality and independence to wives—and “contract” was a term that already described most female marriages. Anne Lister and Anne Walker used wills and deeds to formalize their relationship, and Rosa Bonheur drew up detailed wills with her first and second spouses, Nathalie Micas and Anna Klumpke. Like male and female suitors, who combined sexual and romantic passion with economic calculations (think of the negotiations that accompany courtship in Trollope novels), women in female marriages made formal agreements that combined mutual love with financial interests.

When Rosa Bonheur asked Anna Klumpke to live with her, she first warmly declared her love, then wrote to Klumpke’s mother explaining their decision to “unite [their] existence” and assuring her that Bonheur would “arrange before a lawyer a situation where she [Anna] will be considered as in her own home.” Women like Bonheur and Klumpke modeled their relationships on romantic marriage, defined in terms of love and fidelity, but they also adopted a daringly modern notion of marriage as contract. Radical utopian William Thompson contended in 1825 that marriage was not really a contract because it was an unequal, indissoluble relationship whose terms were determined by the state.

By mid-century his critique had been absorbed into liberal and feminist arguments for the reform of legal marriage between men and women, some made by women in female marriages based on contractual principles. Contract marriage was egalitarian relative to legal coverture because it assumed a mutually beneficial exchange in which each side received consideration. Bonheur’s will explained that she was leaving all her assets to Klumpke because she had asked her “to stay with me and share my life,” and had therefore “decided to compensate her and protect her interests since she, in order to live with me, sacrificed the position she had already made for herself and shared the costs of maintaining and improving my house and estate.”

Forced by necessity to construct ad hoc legal frameworks for their relationships, nineteenth-century women in female marriages not only were precursors of late-twentieth-century “same-sex domestic partners,” but also anticipated forms of marriage between men and women that were only institutionalized decades after their deaths. Women in female marriages used principles derived from contract to dissolve their unions as well as to formalize them. Indeed, the very act of ending a union depended on the analogy between marriage and contract. As Oliver Wendell Holmes put it in The Common Law (1881), the essence of contract was that each party was “free to break his contract if he chooses.” The law did not compel people to perform their contracts, only to pay damages if they did not perform them.

…Female marriages had their share of troubles and were as plagued by infidelity, conflict, and power differences as legal ones, but because the state did not bind female couples for life, their unions exemplified the features that British activists fought to import into marriage between men and women: dissolubility, relative egalitarianism, and greater freedom for both spouses. These were matters of some urgency: the doctrine of coverture dictated that a wife’s income and property unprotected by equity belonged absolutely to the husband alone, as did the couple’s children.

Until 1891 a husband was legally allowed to hold his wife in custody against her will and there was no legal concept of marital rape. In the 1850s, feminists seeking to end coverture and obtain independent rights for legally married women joined forces with liberal utilitarians interested in rationalizing the law and transferring authority from church to state. Together they proposed the property act that Hays and Cushman supported and helped to pass the controversial 1857 Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Act, which made divorce available to many more people than ever before by shifting jurisdiction from an ecclesiastical court to the nation’s first civil divorce court.

The new law did not end coverture or hierarchical marriage, and it codified a double standard that made it more difficult for wives to sue for divorce than husbands. Nevertheless, it was widely perceived as undermining husbands’ power and prestige. A satiric set of sketches in Once a Week portrayed the divorce court as a place where wives tricked and victimized husbands, and the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine noted in 1864 that “the revelations of the Divorce Court show that there are bad husbands as well as good.” Statistics give some sense of the law’s actual effects: when divorce had to be finalized by parliamentary decree, only 190 were granted between 1801 and 1857, while in the ten years between 1858 and 1868, the new civil court granted 1,279 decrees.

The 1857 legislation provided an appealing new option for ending marriage, especially for women: before its passage, only four women had ever obtained a parliamentary divorce decree, but between 1858 and 1868, wives initiated 40 percent of divorce-court petitions and were successful about as often as husbands in dissolving marriages. The 1857 Act had cultural ramifications that went far beyond its legal ones. As Bessie Rayner Parkes put it in 1866, a “universal discussion of first principles . . . accompanied the passing of the New Divorce Bill.” Abstract debates about marriage as an institution were accompanied by a new public appetite for sensational news about marital breakdown.

…The 1857 law of divorce also changed the terms of celibacy, producing much journalistic discussion about whether marriage was necessary at all, especially in light of census figures that showed an increasing number of men and women never marrying. Victorian feminists charged that the social compulsion to marry consolidated male domination, since women entered marriages that made them inferiors only because the unmarried state entailed economic dependence and social death. Those who felt that the only suitable fate for a woman was to become a dependent wife made the unmarried “spinster�� an object of pity: “A single woman! Is there not something plaintive in the two words standing together? . . . No woman is single from choice.”

Others described the single state as unnatural: “There is nothing single in nature; celibacy was never contemplated in creation.” Feminist John Stuart Mill countered that as a result of such stereotypes, the desire to marry was really a revulsion against the stigma of being unmarried, since a “single woman . . . is felt both by herself and others as a kind of excrescence on the surface of society, having no use or function or office there.” For marriage between men and women to be equal, feminists argued, single women had to be able to lead practicable and pleasurable lives. The demand to reform marriage began as a quest to make it more equal and more flexible, then evolved into a demand to make it less obligatory.

To change the quality of life for the unmarried would alter marriage itself. While some drew attention to the difficulties unmarried women faced, others argued that life was already easier for unmarried women than many believed and that marriage was no longer the only desirable female destiny. In the 1860s, unmarried women became visible as activists, philanthropists, and artists whose labor earned them a place in a society made more porous by a general emphasis on reform. The spectacular effectiveness of single women during the Crimean War increased public respect for them. Imperialist rhetoric exhorting England to live up to its values of democracy and equality at home in order better to disseminate them abroad contributed to an increased appreciation of all women’s social contributions.

Feminist Caroline Cornwallis warned readers in 1857 that “to tie the hands of one half of mankind . . . is a suicidal act, and unworthy of a nation whom an omnipotent will seems to have marked out as the great civilizer of the world.” By the 1860s, writing about single women had become enough of a trend for a book reviewer to comment, “If in the multitude of counsellors there is safety, how blest must be the security of single women!” Turning single women into dependents needing guidance from a “multitude of counsellors,” the reviewer concluded that marriage was the best state, because “[m]an and woman need to be One.” Yet even he granted that women who lacked husbands needed work as an outlet for their talents.

Others suggested that single life might be preferable for women, especially in light of the marital miseries publicized by divorce court proceedings. Anne Thackeray noted in her essay “Toilers and Spinsters” (1858) that a single woman “certainly does not envy poor Mrs. C., who has to fly to Sir Cresswell Cresswell [a divorce-court judge] to get rid of a ‘life companion’ who beats her with his umbrella, spends her money, and knocks her down instead of ‘lifting her up.’” Even passionate advocates of marriage hostile to feminism began to accept that some women would never marry. As an example of this, take the most famous Victorian article about single women, W. R. Greg’s “Why Are Women Redundant?” (1862).

Greg’s article is frequently cited as evidence of the contempt Victorians heaped on unmarried women, because his strong commitment to marriage led him to propose sending “redundant” Englishwomen who could not find husbands to colonies where men outnumbered women. But Greg’s article also demonstrates the growing acceptance of single women. Although he pleaded that every woman who could be paired with a man should be, he assumed that because adult women outnumbered adult men, single women were as natural as monogamy.

Nature rules that “marriage, the union of one man with one woman, is unmistakably . . . the despotic law of life,” but “she not only proclaims the rule, she distinctly lays down the precise amount and limits of the exception” (279). Greg quantified the natural exception in terms of census figures showing 106 women over twenty years old for every 100 men in the same age group. What Greg considered a startling anomaly was the census finding that 30 percent of women over twenty were unmarried. By contrast, Greg deemed the “redundant six per cent for whom equivalent men do not exist” (282) a normal exception consonant with “a thoroughly natural, sound, and satisfactory state of society” (282) and proportionate to the “precise percentage of women whom Nature designed for single life” (279).

So natural was the single woman for Greg that he personified Nature herself as a single woman, busily making designs and laying down “the despotic law of life” with no husband to guide her. Greg decried the rising number of unmarried women in England, but he also identified a fixed number of women for whom celibacy was required. He defined those women as “natural anomalies” who lacked femininity, loved independence, wanted to serve humanity, or were “almost epicene” in their genius and power: “Such are rightly and naturally single; but they are abnormal and not perfect natures” (280). The abnormal is imperfect, but it is also natural, and Greg thus asserted that unmarried women (but not unmarried men) were inevitable and socially necessary.

Despite his vehement promotion of marriage, he noted dispassionately that some women “deliberately resolve upon celibacy as that which they like for itself” (281). In a footnote Greg even suggested that single life was the happier choice for many women: “In thousands of instances [maiden ladies] are, after a time, more happy [than wives and mothers]. In our day, if a lady is possessed of a very moderate competence, and a wellstored and well-regulated mind, she may have infinitely less care and infinitely more enjoyment than if she had drawn any of the numerous blanks which beset the lottery of marriage” (299). Greg’s acceptance of single life as natural transformed marriage from a fatal necessity into a lottery, a game of chance whose risks women could rationally choose not to incur.

The changing view of single women indicated the burgeoning of new ideas about marriage. Across the political and rhetorical spectrum, writers in the 1860s testified to the growing awareness that marriage between men and women was not a universal element of social life. In “What Shall We Do with Our Old Maids?” (1862), Frances Power Cobbe used the same statistics as Greg to show that single women were becoming a constitutive and transformative element of England’s social landscape. Cobbe and others argued that single women were happier than they had ever been, and that when unmarried women enjoyed the good life, marriage itself would also change. The suggestion that people could survive independent of marriage also undid the notion of marriage as the union of opposite sexes, each requiring the other in order to supplement a lack, and harmonized with a modern understanding of companionate marriage based on similarity and friendship.

Feminist John Stuart Mill, one of Cobbe’s many personal acquaintances, echoed her sentiments when he wrote in The Subjection of Women (1869) that “likeness,” not difference, should be the foundation of true unions, and that marriage should be modeled on what “often happens between two friends of the same sex.” If marriage was defined by love and patterned on same-sex friendship, then what happened between two friends of the same sex could also be understood as a marriage. In an 1862 essay, “Celibacy v. Marriage,” Frances Power Cobbe wrote that women who did not marry men could still be happy by forming “true and tender friendships”; the celibate woman need not fear “a solitary old age” since she could easily “find a woman ready to share” her life.

In later lectures on The Duties of Women, Cobbe mused, “I think that every one . . . must have the chance offered to them of forming a true marriage with one of the opposite sex or else a true friendship with one of their own, and that we should look to such marriages and friendships as the supreme joy and glory of mortal life,—unions wherein we may steep our whole hearts.” Cobbe subtly shifts her use of conjunctions, from “marriage . . . or . . . friendship” to “marriages and friendships” (emphasis added), thus transforming marriage and friendship from mutually exclusive alternatives into interchangeable bonds for which the sex of the partners makes little difference to the quality of the union.

The triumph of companionate marriage as an ideal not only changed the relationship between husband and wife, but also transformed the status of unmarried people and provided grounds for valorizing same sex unions. The belief that without love it was better not to marry made those who refused to wed out of expediency spiritually superior beings. Cobbe argued that women would marry for love only if the single state were “so free and happy that [women] shall have not one temptation to change it save the only temptation which ought to determine them— namely, love.” Her reasoning shrewdly framed her rejection of compulsory heterosexuality as a desire to improve marriage, and called on defenders of virtuous marriage to support the unmarried woman’s right to happiness.

Implicitly, Cobbe also rallied those who believed in marriage to ratify any union based on affection. In doing so, she may have had in mind a union like her own. As we recall from chapter 1, although Cobbe never legally wed, for over thirty years she lived with a woman she publicly called her “beloved friend,” sculptor Mary Lloyd. Cobbe’s life is an example of how social networks and informal, extralegal relationships affected the political and the legal. Because female marriage was not a marginal, secret practice confined to a subculture, but was integrated into far flung, open networks, women like Cobbe could model their relationships on a contractual ideal of marriage and propose that legal marriage remodel itself in the image of their own unions.”

- Sharon Marcus, “The Genealogy of Marriage.” in Between Women: Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

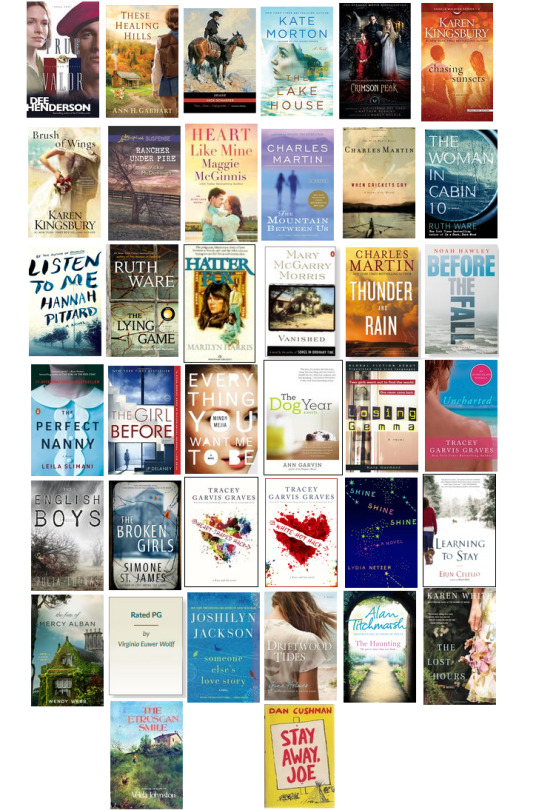

Books Read in 2018: The Why

Third year in a row* of answering the self-imposed question: why did you read this particular book?

(*Although 2017′s is presently flagged by the garbage bot and under appeal -- WHY DO U HATE MY BOOK COVER COLLAGES, MR. ALGORITHM)

I am beginning to deeply regret the extra work involved to split them by category, so next year is probably just gonna be a numbered chronological list after the Quilt of Many Covers, but for now they are still divided into adult fiction, YA, middle grade/children’s books, and nonfiction

FICTION

True Valor - Dee Henderson. 2002. Read because: I went hunting for a military romance in which to cast Dalton and Jaz [The Brave]. This one at least guaranteed me Dalton (and included rescuing a female soldier lost/hurt in combat, so).

These Healing Hills - Ann H. Gabhart. 2017. Had this one in my back pocket for a while as a quality-sounding stock romance (nurse/soldier) waiting for players. When my need for a Barbie/Julia [Under the Dome] story reached a new high, I deemed it a match.

Shane - Jack Schaefer. 1949. This is the book Fourmile is based on, so I thought I could get a two-for-one casting thrill out of it.

The Lake House - Kate Morton. 2015. A gorgeous historic mansion hidden within an abandoned estate. A mystery from the past to be solved in the present. What are "things I am here for always."

Crimson Peak (movie novelization) - Nancy Holder. 2015. I LOVED the movie, and the only thing I love more than amazing movies is when I can have them translated into and enriched by prose.

Chasing Sunsets - Karen Kingsbury. 2015. Brush of Wings - Karen Kingsbury. 2016. I was hunting, desperately, for Ben/Ryan-shaped books [Off the Map], and "Brush of Wings" checked all the boxes (young woman who needs a heart transplant volunteers in a third world country, love interest has to find a way to rush her home when the situation turns dire). I only read C.S. first because I didn't want to miss where the romance started.

Rancher Under Fire - Vickie Donoghue. 2014. I was looking for a different book when I casually stumbled upon this title, and listen. I am not gonna turn down a ready-made Barbie/Julia AU* with bonus "single father" angle. (*cowboy/journalist)

Heart Like Mine - Maggie McGinnis. 2016. "Ben/Ryan, Sexy Hookup AU Version please."

The Mountain Between Us - Charles Martin. 2010. The request list for the movie was too long, so I decided to see if it was based on a book. Upon reading the back cover and finding out one character was a surgeon, I immediately forgot the movie cast as my brain exploded with Shondaland options.

When Crickets Cry - Charles Martin. 2006. "Doctor whose wife died young of a lifelong heart condition" sounded like the best book-shaped Ben/Ryan approximation yet, with bonus "watching out for a little girl who is sick in the same way" cuteness as well.

The Woman in Cabin 10 - Ruth Ware. 2016. A woman at work recommended it to me, and I was like, "a well received general thriller? Sure!"

Listen to Me - Hannah Pittard. 2016. Put "road trip" into the library catalog --> picked 70% because "Gothic thriller" made me think of "The Strangers," and 30% because I was reliving the glory days of Derek And Addison and this marriage sounded similar.

The Lying Game - Ruth Ware. 2017. I enjoyed the other book of hers I read so my friend brought in the next one she had.

Hatter Fox - Marilyn Harris. 1973. Read in high school and forgotten until I reread the Goodreads summary, and "doctor drawn to help 17-year-old" set off my radar. Shippy or merely protective/caretaking, my radar reacts the same.

Vanished - Mary McGary Morris. 1988. The trailer for unreleased Martin Henderson film "Hellbent" whipped me into a frenzy so I did my best to find book-shaped approximations of it. (spoiler alert: this failed miserably, but I grudge-matched it out)

Thunder and Rain - Charles Martin. 2012. Former Texas Ranger who is a single dad. Rescuing & protecting a scared/abused woman and child. At his ranch with cows and horses. By an author who has proven his salt in the hurt/comfort and restrained-romance departments.

Before the Fall - Nick Hawley. 2016. Mostly I came for the dynamic between the young orphan and the passenger who saved him, but I also like witnessing the general aftermath of plane crash survivors.

The Perfect Nanny - Leila Slimani. 2018. My work friend loaned it to me with the statement, "This has such good reviews but I don't know if I 'got' it -- I am really curious to know what you think of it!"

The Girl Before - J.P. Delaney. 2017. She loaned me this one too, with a more glowing recommendation.

Everything You Want Me To Be - Mindy Mejia. 2017. Aaaand one last rec from my seasonal work friend before our projects took us in separate directions.

The Dog Year - Ann Wertz Garvin. 2014. Dog on the cover + synopsis was basically a list of tropes I love: a woman (a doctor to boot!) grieving loss of husband and unborn baby; dogs; a new love interest who is one of my favorite professions to pair with doctor (cop)...

Losing Gemma - Katy Gardner. 2002. "So basically this is the victim backstory to a Criminal Minds: Beyond Borders plot? Dude, sign me UP; I can so see this friendship!"

Uncharted - Tracey Garvis-Graves. 2013. The companion novella to a book I loved.

The English Boys - Julia Thomas. 2016. Mom checked it out of the library, "guy in piney unrequited love with his best friend's fiancee" intrigued me enough to open it, and by 3-5 pages in I was hooked.

The Broken Girls - Simone St. James. 2018. Abandoned boarding-school ruins, a murder mystery from the past being solved in the present day, possibly tied to a second murder from the past?? Yeah, give it.

Heart-Shaped Hack - Tracey Garvis-Graves. 2015. White-Hot Hack - Tracey Garvis-Graves. 2016. Proven quality romance writer's latest books feature a professional super-skilled hacker? Sounds right up my Scorpion-obsessed alley. First book was plenty good enough to launch me into Part II.

Shine Shine Shine - Lydia Netzer. 2012. In my continuing quest to find books in which to cast Walter/Paige, I searched the phrase "her genius husband" and this one's summary matched my desires well.

Learning to Stay - Erin Celello. 2013. Ever eager to expand my hurt/comfort scenario stockpile, I went looking for something where a husband suffers a TBI/brain damage that mostly affects their personality. The bonus dog content sold it.

The Fate of Mercy Alban - Wendy Webb. 2013. Came up on my Goodreads timeline. I read as far as "spine-tingling mystery about family secrets set in a big, old haunted house on Lake Superior" and immediately requested it from the library.

Rated PG - Virginia Euwer Wolff. 1981. I was rereading her Make Lemonade trilogy when I saw a quote in her author bio that said, "I did write an adult novel. Thank goodness it went out of print." Curious, I looked it up, and between its age and the fact that it sounded more like YA than a proper adult novel, I was immediately more intrigued by it than her boring-sounding middle grade books.

Someone Else's Love Story - Joshilyn Jackson. 2013. "Young single mom with genius son meeting a possibly-autistic scientist who protects them during a gas station holdup/hostage situation and later bonds with her son" was the exact literary approximation of a Scorpion AU I wanted in my brain. By the time I realized that was not the endgame ship, I had already flipped through it and fallen in love w/ William and his romantic memories of his wife instead.

Driftwood Tides - Gina Holmes. 2014. Cool title + I love the "young adult adoptee bonds with the spouse of their late birth mother" trope.

The Haunting - Alan Titchmarsh. 2011. Title caught my eye at the library near Halloween; I dug the "dual timelines" setup with a mystery from the past to be solved in the present, and hoped for ghosts.

The Lost Hours - Karen White. 2009. I searched "scrapbook" in the library catalog. A family member's formerly buried old scrapbook, an old house, and unearthing family history/secrets? GIVE IT TO ME.gif.

The Etruscan Smile - Velda Johnston. 1977. Slim (quick read), attractive cover painting, an exotic Italian countryside setting in a bygone era, and a young woman investigating the mystery of her sister's disappearance all appealed to me.

Stay Away, Joe - Dan Cushman. 1953. All I could tell from the book jacket was that it was somehow Western/ranch-themed, possibly full of wacky hijinx and had once been deemed appropriate for a high school library. I just wanted to know what the heck it was about!

-------------------

YOUNG ADULT

(I’m kind of guessing at the line of demarcation between teen and middle grade audiences for some of these, especially the older ones -- another reason that I should give up on categories in the future -- but let’s just go with it)

These Shallow Graves - Jennifer Donnelly. 2015. Seemed like a YA version of What the Dead Leave Behind (which itself I was using as a Crimson Peak AU), from an author whose work has always impressed me.

Snow Bound - Harry Fox Mazer. 1973. Always here for survival stories! Also, this is a good author.

The House - Christina Lauren. 2015. I LOVE evil/haunted mansion stories.

The Masked Truth - Kelley Armstrong. 2015. It looked like Criminal Minds in a YA novel.

Things I'm Seeing Without You - Peter Bognanni. 2017. Went googling for stories that sounded like contemporary variations on Miles & Charlie Matheson [Revolution]. "Teen shows up at estranged father's door" fit the bill.

Even When You Lie to Me - Jessica Alcott. 2015. I always turn out for student/teacher stories, given enough suggestion of it being mostly an emotional connection rather than an illicit hookup.

Too Shattered for Mending - Peter Brown Hoffmeister. 2017. I also dig stories where teenagers have to take care of/fend for themselves in the absence of a parent/guardian.

The Devil You Know - Trish Doller. 2015. I enjoyed a previous book of hers, and I always like road trips and teen thrillers.

The Raft - S.A. Bodeen. Terror at Bottle Creek underwhelmed, so I thought I'd try a YA/female protagonist option for a survival thriller, not least because the girl on the cover reminded me of Under the Dome's Melanie.

Ghost at Kimball Hill - Marie Blizard. 1956. Picked up randomly at an estate sale; the vintage cover and incredibly charming first 2 pages won my heart.

A New Penny - Biana Bradbury. 1971. The rare idea of a teen shotgun marriage in this era -- when it would still be expected, but also more likely to fall apart and end in a young divorce or separation -- fascinated me; I was curious to see how such an adult situation would play out.

Marie Antoinette, Serial Killer - Katie Alender. 2013. I mean...it is really all right there in the title and/or the awesful puns all over the cover. ("Let them eat cake...AND DIE!") Pure unadulterated crack, combining my two fave specialty genres of history and horror? Yes ma'am.

Me And My Mona Lisa Smile - Sheila Hayes. 1981. I was looking up this author of a Little Golden Book to see what else she had, found one that suggested a student/teacher romance, and bolted for it.

To Take a Dare - Crescent Dragonwagon/Paul Zindel. 1982. 50% due to the first author's cracktastic name and my full expectations of it being melodramatic, 50% because I was still on my "Hellbent" high and looking for similar teen runaway stories.

To All My Fans, With Love, From Sylvie - Ellen Conford. 1982. The last one from my attempt-at-a-Hellbent-esque-storyline set -- girl hitchhiking cross-country is picked up by a middle aged man who may or may not have pure intentions, by an established quality author.

Be Good Be Real Be Crazy - Chelsey Philpot. Bright cover called out to me; I was in the mood for a fun road trip novel for spring/early summer.

This is the Story of You - Beth Kephart. Kephart's name always gives me pause due to her fuzzy writing style, but I loved Nothing But Ghosts, so I could not resist the promise of surviving a super-storm disaster.

A Little in Love - Susan Fletcher. "Eponine's story from Les Mis" on a YA novel = immediately awesome; I LOVE HER??? Also it's just my fave musical, generally.

Adrift - Paul Griffin. 2015. I've been really digging survival stories this year, and while stories about survival at sea aren't typically my fave, they keep popping up in my path so I keep poppin' em like candy.

Life in Outer Space - Melissa Keil. 2013. After delighting my brain with concept sketches for a high school AU, I set out to find the equivalent of Scorpion's team dynamics/main relationship in a YA novel, and by god I found it.

Everything Must Go - Fanny Fran Davis. 2017. The brightly colored cover drew me in, and the format of being like a scrapbook of personal documents/paper ephemera lit up the scrap-collecting center of my brain.

Going Geek - Charlotte Huang. 2016.

originally I thought it might be like Life in Outer Space, but once I realized the title geeks were all girls I shrugged and went, "Eh, still a solid contemporary YA novel at a cool setting (boarding school)."

Like Mandarin - Kirsten Hubbard. 2011.

By the author of my beloved Wanderlove, I was drawn in by the title, intriguing cover photo, rural Wyoming setting and the concept of a high school freshman girl latching onto/idolizing a cool senior girl.

Sixteen: Short Stories By Outstanding Writers for Young Adults. ed. Donald R. Gallo. 1984. Tripped over it at the library, and immediately wanted to consume a set of 80s teen book content from a pack of authors I know and love.

A & L Do Summer - Jan Blazanin. 2011. In the summer, sometimes you just want to vicariously relive the feeling of being a largely-responsibility-free teen in a small-town location.

The Assassin Game - Kirsty McKay. 2015. Looked like the (Welsh!) boarding school version of Harper's Island. (spoiler alert: it is rather less stabby than that, but still fun)

We Are Still Tornadoes - Michael Kun/Susan Mullen. 2016. "College freshmen? Writing letters to each other? Sure, looks solid."

Nothing - Annie Barrows. 2017. It looked relatable: like the kind of book that would happen if I tried to turn my high school journals into a book. (spoiler alert: dumber)

The Memory Book - Laura Avery. 2016. Contemporary YA about a girl with a(n unusual) disease, but mostly, the title and promise of it being a collection of entries in different formats.

Kindess for Weakness - Shawn Goodman. 2013. LITERALLY AU RYAN ATWOOD.

Make Lemonade - Virginia Euwer Wolff. 1993. True Believer - Virginia Euwer Wolff. 2001. This Full House - Virginia Euwer Wolff. 2008. I reread the first two so I could give them proper reviews on Goodreads, and then realized I hadn't read the last one at all.

Blue Voyage - Diana Renn. 2015. A hefty teen mystery in a unique exotic location (Turkey) -- with an antiquities smuggling ring! - called out to me.

Girl Online - Zoe Sugg. 2014. I was really in the mood to read something on the younger end of YA, something cute and fun, when I saw this at the library.

Wilderness Peril - Thomas J. Dygard. 1985. Reread of a book I rated 4 stars in high school but couldn't remember, which happened to be lying next to me on a morning where I didn't wanna get out of bed yet.

Survive the Night - Danielle Vega. 2015. The cover had a GLITTERY SKULL. Give me that delightfully packaged horror story for the Halloween season!

The Hired Girl - Laura Amy Schlitz. 2015. I've been digging into my journals and old family photo albums lately, really fascinated by personal historical documents (also recently obsessed over The Scrapbook of Frankie Pratt), and when I saw a diary format book set in 1911 -- a housemaid's diary, no less; that must be interesting as far as recording grand house details -- it spoke to me.

Fans of the Impossible Life - Kate Scelsa. 2015. The colored-pencil-sketch cover gave me Rainbow Rowell vibes.

All The Truth That's In Me - Julie Berry. 2013. Someone who favorably reviewed The Hired Girl also recommended this one; the cover caught my eye, and it sounded like a thriller.

Girl In A Bad Place - Kaitlin Ward. 2017. I heart YA thrillers featuring girls.

Facing It - Julian F. Thompson. 1983. I was in desperate need of a book one night and my only option was to buy one off the library sale cart, so I snagged the one that looked like some entertaining 80s melodrama with a fun (summer camp) setting. (Spoiler alert: fun and entertaining it was not.)

A Good Idea - Cristina Moracho. 2017. "Rural literary noir," promised the cover blurb, and as I just mentioned: I heart YA thrillers.

Something Happened - Greg Logsted. 2008. Short/easy read + I was hoping for either a misinterpreted Genuinely Caring Teacher, or scenarios to use in an appropriate age difference context.

In Real Life - Jessica Love. 2016. My shipper radar pretty much looked at the summary and went "THE AU CHRISTIAN/GABBY SETUP OF MY DREAMS."

The Black Spaniel Mystery - Betty Cavanna. 1945.

Adorable cover (and dogs!) from an established quality author.

--------------

CHILDREN’S / MIDDLE GRADE

The Cloud Chamber - Joyce Maynard. 2005. The cover made me think of Under the Dome, and the MC immediately reminded me of Joe McAlister.

Terror at Bottle Creek - Watt Key. 2016. After rereading Fourmile, I got a hankering for more books I might be able to cast with the kids from Under the Dome, and figured more Watt Key + a thrilling survival adventure was the ticket for that.

Swampfire - Patricia Cecil Haas. 1973. One of approximately 100 unread vintage horse books I own at any given time; finally in mood because it was short and sweet.

Baby-sitting Is A Dangerous Job - Willo Davis Roberts. 1985. Reread a childhood favorite in order to give it a proper review on Goodreads.

In The Stone Circle - Elizabeth Cody Kimmel. 1998. Same as above.

Wild Spirits - Rosa Jordan. 2010. Clearly the "Kat & Tommy take Justin under their wing" Power Rangers AU of which I have always dreamed, in my very favorite version of it: the one where Kat surrounds herself with animals.

Claudia - Barbara Wallace. 1969. Picked up cheap at a book sale, standard cute vintage Scholastic about a girl and her school life. Comfort food.

Reasons to be Happy - Katrina Kittle. 2011. The cover and the 5 reasons excerpted in the summary were so cute that I wanted to know what more of the reasons were.

Dark Horse Barnaby - Marjorie Reynolds. 1967. Needed a quick read and I'll p. much read any vintage horse book.

Runaway - Dandi Daley Mackall. 2008. Start of a companion series to my beloved Winnie the Horse Gentler, featuring some favorite themes: foster care + animal rescue.

Wolf Wilder - Katherine Rundell. 2015. Pretty cover, girl protagonist, historical Russian setting, wolves. All good things!

Backwater - Joan Bauer. 1999. Sounded like a beautifully tranquil setting.

The Dingle Ridge Fox and Other Stories - Sam Savitt. 1978. Animal stories + author love = automatic win.

If Wishes Were Horses - Jean Slaughter Doty. 1984. Overdue reread of a childhood favorite because I needed some short books to finish the reading challenge.

-------------

NONFICTION

Junk: Digging Through America's Love Affair with Stuff - Alison Stewart. 2016. I mean, I am definitely an American who has a love affair with stuff.

Keeping Watch: 30 Sheep, 24 Rabbits, 2 Llamas, 1 Alpaca, and a Shepherdess with a Day Job - Kathryn Sletto. 2010.

As soon as I saw my favorite fluffy creature on the cover, I felt an immediate need to transport myself into this (dream) hobby farm setting.

(Side note: this is probably the lowest amount of nonfiction I have read in 1 year for a decade, but I was just so busy hunting down specific types of stories that I could not get distracted by random learning.)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Preston, Stockport and Macclesfield among ‘places to watch’ in 2020, says Cushman & Wakefield - Business Live https://t.co/4OVyvLjhX9

Preston, Stockport and Macclesfield among ‘places to watch’ in 2020, says Cushman & Wakefield - Business Live https://t.co/4OVyvLjhX9

— Mortons Solicitors (@MortonsSols) January 4, 2020

January 04, 2020 at 11:07AM

0 notes

Text

Oopsie. Up yours suckers

1 note

·

View note

Text

They brought in the mob

1 note

·

View note

Text

Oh no

1 note

·

View note

Text

You cwaffle

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Lewis Morrison (September 4, 1844 – August 18, 1906) was a Jamaican-born stage actor and theatrical manager, born Moritz (or Morris) W. Morris. He was of English, Spanish, Jewish, and African ancestry. He was known for his portrayal of Mephistopheles in his production of Faust, which he performed from 1885 to 1906. He became a stage actor using the name Lewis Morrison. He first performed in New Orleans beginning in minor roles with Edwin Booth and Charlotte Cushman until he was featured in larger parts. He became a well-known actor in New Orleans and moved on to the stage in New York, where he gained greater fame in Faust. He founded his traveling theater troupe and traveled the world playing the role of Mephistopheles. He was married first to Anglo-American actress Rose Wood. He was the father of actresses Rosabel Morrison and Adrienne Morrison; grandfather of actresses Constance, Barbara, and Joan Bennett; and great-grandfather of television talk show host Morton Downey Jr. He and Rose Wood were divorced in 1890. He married the much younger stage actress Florence Roberts in 1892. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence https://www.instagram.com/p/CiFWdAfOvtsfiEoi_v3HRkj7f0YIpO9XoNh10s0/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes