#moral theology

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

What does Catholic morality teach about the seventh commandment and the meaning of human work?

I am a graduate student at the beginning of my career. In the context of schooling, I am studying for a Master of Arts in theology. In the context of work, I provide care at a residential mental health facility for women. For the first time in my life, I am making a definitive and long-term dedication to the work I do. The current period is different from my undergraduate studies in that I could easily change course in the direction I wanted to go (case in point: I changed one of my majors from Psychology to Biochemistry, and back again). As a graduate student, my work counts toward only my program. As a Mental Health Technician, the quality and consistency of the work I do in my one position reflects my competence and current abilities in the mental health field.

Saint John Paul II describes work as “a fundamental dimension of man's existence on earth” in his work Laborem Exercens (LE no. 4). The Father provided the seventh commandment, “you shall not steal” (Exodus 20:15), to guide this integral part of human existence. In this blog post, I will explore three aspects of the seventh commandment and work: first, the connection between the two, second, the inherent inclination and duty to fulfill the commandment through work, and third, the benefits of fulfilling the seventh commandment through work, for the person and for people as a group.

How does the seventh commandment apply to work?

The seventh commandment, “you shall not steal,” concerns the distribution and possession of goods. Negatively worded (in terms of “what not to do”), the seventh commandment “forbids unjustly taking or keeping the goods of one’s neighbor and wronging him in any way with respect to his goods” (CCC 2401). Positively worded (in terms of “what to do”), the seventh commandment “commands justice and charity in the case of earthly goods and the fruits of men’s labor” (CCC 2401). The different aspects of this commandment reveal different ways in which the commandment relates to work.

The negative sense of the commandment prohibits impeding someone else’s acquisition of goods through the process of work. The Catechism explains that “unjustly taking and keeping the property of others is against the seventh commandment” (CCC 2409). The property of others include the money and goods gained through work: for instance, one’s due wages or the goods that someone produces. Therefore, by the seventh commandment, actions like withholding just pay for one’s employees would be forbidden. This commandment does not only apply to the employer. Employees can also break the commandment by misusing the goods of an enterprise or by doing one’s work poorly, thus affecting the success of the company and of one’s coworkers.

The positive sense of the commandment, in contrast, mandates that the virtues of justice and charity guide helping one’s neighbor have access to what he or she has earned through labor. Justice relates to the seventh commandment in that one should be given access to his or her due wages. Making the active choice to provide fair wages to one’s employees, even when one has the option not to do so, is an example of living out the commandment in a positive sense. For the employee, using the goods of one’s trade to work wisely and efficiently would help one to keep the seventh commandment. These examples illustrate that the “spirit” of the law behind not stealing is comprised of love of G-d, respect and charity for created goods, and respect and charity for one’s partners in work.

Work is humanity’s natural duty.

Each person has a natural inclination and duty to work. Humanity is an industrious and resourceful species. One avenue of human fulfillment is the work that one completes. While “work is for man, not man for work” (CCC 2428), the desire that a person has to contribute to society and the pride one feels in a job well done attest to the inherent desire for work present in each person. The idea that work exists for the fulfillment of man explains how the economic life “is ordered first of all to the service of persons, of the whole man, and of the entire human community” (CCC 2426).

Someone can observe the human inclination to work by spending time with children. Children are wired to create and to work. Pretend play, in which a child acts like a baker, construction worker, or a doctor, is practically synonymous with the childhood experience. Outside of play, children want to contribute to a job well done. Their curiosity inclines them to offer help with cooking, shopping, and chores. If this desire is fostered rather than diminished by the adults in one’s life, then children experience a natural progression of complexity in the work assigned to them by the adults in their life, until they transition into the world of adult work. My parents trusted me to do tasks like cooking and cleaning when I was younger. It fostered a sense of satisfaction and independence in how I approach work, and now, I look forward to each workday because it means another chance to do my job well and to contribute meaningfully to the lives of others.

While work is humanity’s natural duty, achieving satisfaction of that duty looks different for each individual, and even for the same individual in different contexts. When I was younger, my “work” was schoolwork and rehabilitation activities, depending on the time of my life being discussed. Now, my “work” involves helping women with mental troubles and teaching them about the aspects of living a healthy life. For the cognitively disabled individual, “work” may look like completing a job with accommodations. I have a wool sheep figurine on my dresser that I bought in Israel and that was made by an individual in a L’Arche community. It is a cute figurine, and I hope the person who made it takes pride in his or her job well done. The common thread that runs through these experiences is having a task accomplished, a task in which one can take confidence. Having the bravery and knowledge to complete these tasks is commendable. As we see in the next sections,

Work is beneficial for the individual and society.

Work benefits individuals in a constant way in that it fits with the stable dignity of the person. Saint John Paul II describes work as “a good thing for man. It is not only good in the sense that it is useful or something to enjoy; it is also good as being something worthy, that is to say, something that corresponds to man's dignity, that expresses this dignity and increases it” (LE no. 9). I hope it is self-evident that each person has inherent dignity that neither people nor experiences can diminish. Work serves to amplify this dignity because, when someone completes work, that shows the person acting in the dignity with which he or she was created. As a trait unique to humans, the person completed work.

Work also benefits individuals in a particular way in that it can exist in coordination with one’s redemption. According to the Catechism, “Work . . . can also be redemptive. By enduring the hardship of work in union with Jesus, . . . man collaborates in a certain fashion with the Son of [G-d] in his redemptive work” (CCC 2427). Jesus redeemed humanity through his suffering, death, and Resurrection. One can unite the toil of one’s work to Christ’s Passion in order that it could act for one’s redemption, in the temporal sense as well as in the eternal sense. The experience of work, again, whatever “work” means for us, makes us better people: more patient, more disciplined, and more skilled.

Finally, work helps more than the person. It also helps people, as a group, by impelling societies to grow in justice. As Jared Dees shares in “The Seven Principles of Catholic Social Teaching,” “work is the way that we participate in [G-d’s] creation. To protect the dignity of work, we must protect the basic rights of all people to find jobs that pay a just wage, to organize and join unions, and to own private property (The Religion Teacher, “The Seven Principles of Catholic Social Teaching”). Societies function through the work of its members. This work occurs smoothly, thus helping society to function smoothly, when justice, charity, and truth guide the relationships and tasks of both employers and employees. When individuals contribute to the justice of work in a society, the society improves as a result. The difference begins with the individual.

Conclusion

The seventh commandment instructs us about the use and possession of created goods. In its forbiddance of the unwise or unjust use of goods in one’s approach to work, it encourages individuals and societies to approach work and the distribution of goods with the virtues of justice and charity. Humans are naturally inclined to work. Although this “work” looks different depending on individual abilities and needs, one can easily say it is natural and good to take confidence in a job well done. Work benefits individuals by corresponding with human dignity and helping humans to play a part in their own redemption. The work of virtuous individuals helps societies by moving them to flourish in justice and charity.

As I come to the end of my Moral Theology course, I can say confidently that I take confidence in doing this job well. I received the right instruction and tools, and I know that I completed the course work to the best of my ability. I feel that completing this course has made me a more virtuous person through allowing me to learn more about moral theology, but also through prompting me to test my comfort and boundaries in expressing myself. I know that this satisfaction is the satisfaction I want to feel as I move on to complete other work in my life.

Bibliography

Dees, Jared. “Video: The Seven Principles of Catholic Social Teaching.” The Religion Teacher. May 15, 2017. https://www.thereligionteacher.com/principles-catholic-social-teaching/.

John Paul II. Laborem Exercens. September 14, 1981. The Holy See. https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_14091981_laborem-exercens.html.

#catholic#catholicism#catholic theology#morality#moral theology#work#seventh commandment#Bible#theology#theology student

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The Good Place: Metaethics and Moral Intuition.

Finally, a comedy about ethics and ethicist. The shows creator Michael Schur really came out with an amazing concept that allows the audience to both laugh hysterically and think critically at the same time. I highly recommend this show but I am a moral philosophers of sorts and as the show is fond of saying, “this is why everyone hates moral philosophy professors.” In the past I have raised moral issues and brought up ethical lessons from this show but up to now I have not dedicated a post on the moral contributions of this show.

The premise of the show presents a deep, perhaps the deepest, of moral dilemmas. Eleanor, a morally flawed individual has accidentally been admitted into the good place (heaven). And that person wants to avoid getting caught and be sent to the bad place (hell). In order to do this she teams up with her unusually cooperative “soul mate” Chidi who happens to be a moral philosopher to learn to be a good person and earn her stay in the good place (now that she knows it’s for real). As the video above states, the show highlights two important ethical aspects, the overall context of philosophical ethics known as metaethics, and the role of moral intuition as it emerges in Eleanor’s quest to be good.

Evidently Eleanor’s character is so morally deficient that Chidi has to introduce her to metaethics. Metaethics is the study of the foundational worldview for an ethical framework. Christianity most certainly employs a form of moral realism that consist of formal moral norms and yet is open to cultural interpretation. Many ethical frameworks play a role in Christian ethics including deontology, utilitarianism, proportionalism, divine command, virtue ethics, and ethics of care but natural law theory is perhaps one of the strongest frameworks it has. Crash course philosophy offers a wonderful introduction below.

youtube

The second moral aspect of “The Good Place” that I want to highlight is the role of moral intuition. It is interesting how Michael Schur develops the premise for the show and plays out the moral dilemma that Eleanor, Chidi, Jason, and Tahani are in. We later learn that the heavenly architect is actually a demon named Michael who designed a false “good place” in order to torture his victims with a moral dilemma which was meant to torture them in the afterlife, a subtle “bad place” that is based on Jean Paul Satre’s belief the “hell is other people.” The context for the show suggests there is a determined universe based on some kind of point system and as we become aware of Eleanor’s earthly reality in Season 1 episode 12 we see how young Eleanor’s family impacted her own apathetic moral development. This demonstrates how causes determined the choices she made which impacted her own moral development. But as the show progresses and Eleanor enters the world of metaethics (albeit for initially self serving motives) moral wrenches are thrown in every episode suggesting that unexpected moral intuitions can impact a determined order.

Probabilism suggests that in the absence of certainty, plausible ethical opinions may offer a legitimate, but perhaps unpredictable, moral decision. In a determined universe we see a certain order based on cause and effects but the realm of quantum mechanics demonstrates that we are aware of probability waves that can only show us the probability of causal reactions without absolute certainty. We do not know how probable and perhaps unpredictable free actions may impact a determined universe. This is what I have been calling probable determinism. A theory which suggests that at the quantum level of individual decision making there are only probable actions that may alter the deterministic design in ways we currently do not understand. Institutions may exist within a realm of moral absolutism but the principles that flow from these institutional pronouncements can, at best, guide and influence individual actions. In the end it is the individual actions that can bend and warp the fabric of the moral universe. This is what we have considered free will and actions.

Moral intutions exist within the framework of our humanity through what we call conscience. I'll discuss this more in another post following this one on ethical frameworks but what is important to know is that even though we do not know how our conscience works our philosophical ancestors, from Cicero to Aquinas, believed that we are equipped with a God given moral intuition that recognizes, at some level, the moral principles of the natural law. This intuition has been called the synderesis and it is almost like having a moral God-particle that orients us all to the universal moral norms and principles. What the show and ethics believes in is that learning ethical perspectives may not, in and of itself, make us a better person, but it can activate our moral intuition, our synderesis, in ways that allow us to be better attuned to these norms and priniciples as we consider the moral conundrums we face.

Eleanor is able to mess with the order of Michael’s design and the purpose of the "good" place through the unexpected moral actions she chooses. The judges and architects of the afterlife loose control of even their most sanitary system like Janet's void which is normally an empty white space but by season four looks like this.

The point is that Eleanor’s enhanced ethical development does seem to make an impact. On a personal level it develops her moral intuition which allows her to be more reflective to other positions and become more morally considerate to others. These intuitions on the other hand allow her to change the cosmological equation which for the show meant to perpetuate a subtle tortuous suffering between the four protagonists. Eleanor’s ability to love and empathize with others now builds an authentic friendship with Chidi, Jason, and Tahani (it even morally impacts the demon Michael who was responsible for tormenting them), and that undermines their tortured existence. All this seems to infer that our morally reflective free will and actions does have a role in changing our own cosmological reality. An interesting idea for us to ethically consider.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

SAINT OF THE DAY (August 1)

St. Alphonsus Liguori is a doctor of the Church who is widely known for his contribution to moral theology and his great kindness.

He founded the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer, known as the Redemptorists, on 9 November 1732.

He was born on 27 September 1696 in Naples to a well-respected family and was the oldest of 7 children.

His father was Don Joseph de' Liguori, a naval officer and Captain of the Royal Galleys, and his mother came from Spanish descent.

He was very intelligent, even as a young boy. As a boy of great aptitude, he picked up many things very quickly.

St. Alphonsus did not attend school; rather, he was taught by tutors at home where his father kept a watchful eye.

Moreover, he practiced the harpsichord for 3 hours a day at the heed of his father and soon became a virtuoso at the age of 13.

For recreation, he was an equestrian, fencer, and card player. As he grew into a young man, he developed an inclination for opera.

He was much more interested in listening to the music than watching the performance.

St. Alphonsus would often take his spectacles off, which aided his myopic eyes, in order to merely listen.

While theatre in Naples was in a relatively good state, the young saint developed an ascetic aversion to perhaps what he viewed as gaudy displays. He had strongly refused participation in a parlor play.

At the age of 16, he became a doctor of civil law on 21 January 1713, though by law, 20 was the set age.

After studying for the bar, he practiced law at the age of 19 in the courts. It is said in his 8 years as a lawyer, he never lost a case.

However, he resigned from a brilliant career as a lawyer in 1723 when he lost a case because he overlooked a small but important piece of evidence.

His resignation, however, proved profitable for the Church. He entered the seminary and ordained three years later in 1726.

He soon became a sought-after preacher and confessor in Naples. His sermons were simple and well organized that they appealed to all people, both learned and unlearned.

However, his time as a diocesan priest was short-lived: in 1732, he went to Scala and founded the Redemptorists, a preaching order.

He was a great moral theologian and his famous book, “Moral Theology,” was published in 1748.

Thirty years later, he was appointed bishop and retired in 1775. He died on 1 August 1787.

He was beatified by Pope Pius VII on 15 September 1816. He was canonized by Pope Gregory XVI on 26 May 1839.

He was proclaimed a Doctor of the Church by Pope Pius IX in 1871.

#Saint of the Day#St. Alphonsus Liguori#Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer#Redemptorists#Moral Theology

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

yeah we might be brothers in christ but so were cain and abel so shut the fuck up before i decide to find a rock about it

#postscript;#if you try to tell me cain and abel were not brothers in christ shut up pls#i've studied theology for nearly a decade. i know more than you.#christ's harrowing of hell exists to retroactively turn all of humanity even before his existence into ''brothers'' in christ#because it is not a literal term it is an evangelist term. bc christianity in all denominations is evangelistic in nature#not being a christian is 1. a moral incorrect choice according to them and#2. not actually possible. everyone is judged as a christian everyone is fundamentally supposed to be christian#calling someone a brother in christ is just calling them christian.#so ergo according to doctrine cain and abel are in fact brothers in christ#but#and this is far more important than any of that#i was not trying to be perfectly accurate to the theological timeline of the tanakh vs torah vs old testament vs new testament vs apocrypha#i was trying to make a silly one line joke on the internet#and all you do when you try to go Well Actually They Werent is make yourself look stupid and pedantic.#so for the love of god stop it with needing to be right online im so bored and tired

56K notes

·

View notes

Text

“For [David] DeCosse and many others, the excitement of the present moment consists in the growing ecclesiastical strength of the dominant academic postconciliar conscience-centered Catholic moral theology, in which ‘conscience’ is a place of profound encounter with the other, grounded in a pluralistic sense of historically contextualized human personhood and in respect for the laity's ability, guided by the Spirit, to get things right even when this necessitates changing the church's consistent magisterial teaching.”

— Matthew Levering: “Introduction”, The Abuse of Conscience

1 note

·

View note

Text

so like is the state of moral theology at this point that on one side is Rahner and Fuchs’s school in Europe and McCormick, Keenan, and maybe Gaillardetz in the US - and on the other side is like, Grisez (US) and Finnis (Europe). do people even take Grisez seriously, because my impression is that scholars [read: the jesuits] dont like him very much and his theology seems (as I can gather from secondary sources eg. lawler & salzman (I know, I know) and the journal Theological Studies) to be very defensive of status quo, if not even stricter. also I’m clearly showing my American penchant for pitting two sides against each other. also ig I wouldn’t have considered Keenan a “progressive” so much as simply a good historically-conscious scholar (there’s a new book of his that’s out on the history of catholic ethics) but he did just contribute a (rather saccharine) article to America Media’s outreach.faith so like. okay. if youre writing for America’s Outreach site you’ve ipso facto outed your views lol.

#I have like 0 formal stake in this as a non-catholic but I DO have that infatuation that Im sure is not all that rare among non-catholics.#this has to be a Type Of Guy.#Ive just started to read some Josef Fuchs and there's a lot of good stuff in there#I want to read more about McCormick's distinction between moral dogma and changeable/contingent implications#moral theology#Is America's outreach site like those Manhattan religious-run parishes that also have men's groups ie. the religious superiors dont care#so long as there's no ruckus#catholic theology#catholicism#catholic

0 notes

Text

"Everything went wrong after David Bowie died" "everything went wrong after the Reformation"

Me, whose Metaphysics studies and medievalist interests have been heavily shaped by Dominicans: everything went wrong after Ockham et al. sustained the primacy of Will before Good in the nature of God.

#Theology#Christianity#Catholicism#it's funny because it's one of those discussions that sound extremely Byzantine#But if Good precedes Will in God then God's Will is primarily good#and its goodness must be discerned rationally by the creature#but if Will precedes Goodness then good is essentially and substantially arbitrary#God could have perfectly chosen to create a world where murder is always a good and heroic action#or where one's first duty is to make everyone's lives as miserable as possible#And that would be literally good and the good in such a world because God so willed it#such an understanding of the primacy of will on the ontological order leads to an understanding of reality as dominated by power#and in that scheme self-serving manipulations of religion and Scripture are not only easy but rationally justified#that's the where and why of Benedict XVI's motto being cooperatores veritatis#the cooperators or servants of truth#because Truth cannot be possesed and used#it can only be sought and followed after#in honesty and humility#which again ties back to the supremacy of good (and its transcendental truth) in the metaphysical order#EDIT: this is also where strain-the-mosquito-swallow-the-camel legalistic attitudes come from#Because if what's good is what is defined by the will of God as expressed in textual commands#then any comprehensive rational inquisitive reading is out of the question#and will-infused casuistry is in#Biblical literalism can only thrive in this sort of tradition#“where does it say in the Bible that [insert hyperspecific thing...”#but it's also the environment in which the kind of attitude denounced in pharisees#as sticking to precepts without embracing the moral good that sustains them#and so twisting said precepts to their own convenience

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay I want some people to try this:

Using only science, math, logic, reason, etc, explain to me why murder is wrong. No theology, morality, philosophy, emotions, feelings, etc. Only cold hard facts. Explain why murder is wrong.

I am trying to see something here.

#i am convinced it is impossible but i want to see#philosophy#morality#ethics#sociology#morals#pro life#pro choice#abortion#abortion rights#reproductive rights#theology#progressive christian#christblr#progressive christianity#cathblr#catholicism

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

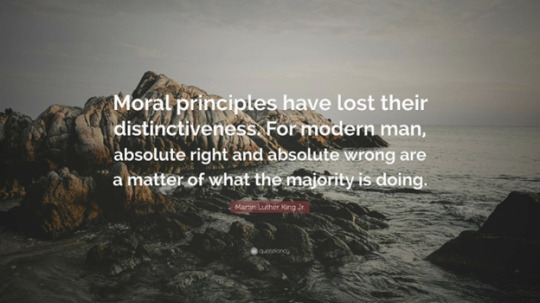

The above quote from Martin Luther King, Jr., points out an alarming trend in human behavior: specifically, that matters of right and wrong have become a matter of majority rule. This phenomenon is natural. Psychological studies have shown that the existence of litter in an environment predicts the littering of other individuals. In a generation of AI use, students have increasingly used AI to plagiarize assignments and are more likely to do so when they know that other students are doing it. On the most extreme level, media portrayals of abortions as an option frequently needed and taken can influence the media consumer to agree that abortions should remain widely available.

Catholic theology defies the societal trend of morality becoming a decision of the majority. As Catholics, we maintain that moral absolutes exist and rely on these absolutes, as given to us in the Decalogue (Ten Commandments) and analyzed further in Church teachings. Moral absolutes specify “intrinsically evil acts” and point to what is right by indicating what actions are wrong. In this post, I will answer why moral absolutes are important for Catholic theology. I will also examine why some people reject the idea of moral absolutes, and why this rejection cannot be maintained consistently.

Why are moral absolutes important for Catholic morality and why do some people reject the idea of moral absolutes?

Catholic theology recognizes activity as “morally good when it attests to and expresses the voluntary ordering of the person to his ultimate end and the conformity of a concrete action with the human good as it is acknowledged in its truth by reason” (VS 72). This quote from Veritatis Splendor tells us several features of the Catholic understanding of morality. First, moral good is voluntary. Without the freedom to act, there is no morality. Second, moral good is aligned with a person’s ultimate end. In Catholicism, we understand this ultimate end to be union with G-d. Moral actions contribute to our journey toward this end. Third, moral good consists in concrete actions. In other words, morality is a lived experience and not just an intellectual exercise. Fourth, moral good exists in conformity with the value of reason. When we perform morally good actions, our reason and our will align in pursuit of the good. With a well-formed reason, doing the good makes sense.

In addition to recognizing, encouraging, and applauding morally good activity, Catholic theology recognizes and condemns morally bad activity through moral absolutes. Moral absolutes are one aspect of the Catholic moral framework that contribute to moral good. They provide negative definitions of the tenets of Catholic morality; that is, they tell us what is right by telling us what not to do in order to achieve the right and the good. Though negative, moral absolutes “allow human persons to keep themselves open to be fully the beings they are meant to be” (May, 162).

Moral Absolutes and Catholic Morality

May defines moral absolutes as “moral norms identifying certain types of action, which are possible objects of human choice, as always morally bad, and specifying these types of action without employing in their description any morally evaluative terms” (May, 142). They prohibit “acts which, per se and in themselves, independently of circumstances, are always seriously wrong by reason of their object” (RP, 17). Moral absolutes are important for Catholic morality because all judgments require a standard, and moral absolutes provide a standard for the judgments of Catholic morality. Moreover, the absolutes of Catholic morality have a Divine source, which provides secure authority for its teachings.

Catholic theology has moral absolutes because moral absolutes protect and promote what is good. They do so because moral absolutes function as standards of how failure to achieve moral good looks. Like danger signs, they tell us which actions and spiritual “places” or states to avoid. According to May, “They remind us that some kinds of human choices and actions, although responsive to some aspects of human good, make us persons whose hearts are closed to the full range of human goods and to the persons in whom these goods are meant to exist” (May, 162).

Conscience relies on the existence of moral absolutes. One definition of conscience is “one’s personal awareness of basic moral principles or truths” (May, 59). This awareness, called synderesis in the medieval tradition, refers to “our habitual awareness of the first principles of practical reasoning and of morality” (May, 59). Synderesis requires that principles of practical reasoning and morality exist in the first place. However, another level of conscience exists which refers to “mode of self-awareness whereby we are aware of ourselves as moral beings, summoned to give to ourselves the dignity to which we are called as intelligent and free beings” (May, 60). On this level as well, which tradition has referred to as conscientia, we require moral absolutes. Moral absolutes benefit conscientia by showing the standard to which we are called. Avoid lying to others or harming them. Do not dishonor G-d or one’s neighbor.

On the Rejection of Moral Absolutes

People who reject moral absolutes may fall into the camp of teleological ethical theory, which includes proportionalism and consequentialism. The proportionalist would weigh the “good” and “bad” effects of a moral choice and judge as right any moral decision that the actor perceived as producing more “good” effects than “bad.” The consequentialist would judge an act as right that had the relatively “best” consequences, no matter how one reached those consequences. Both of these moral theologies are called “teleological” because proponents place all focus and emphasis on the end, or telos, of human action.

A charitable proposal for why people may reject moral absolutes is because they get lost in the details of moral situations. For instance, committing credit card fraud is wrong. However, the reasons that one commits it or the details of why someone makes the decision could lead someone to call the action right. One could easily identify as wrong someone who commits credit card fraud to buy the newest smartphone. Committing said fraud to feed oneself or one’s children is still wrong, but the proportionalist would argue that the good of feeding someone outweighs the wrong of credit card fraud. The consequentialist would argue that the good end justifies the evil means.

To look at it from a simpler point of view, people may reject moral absolutes because they want to rationalize actions that are wrong. For instance, I used to be pro-choice. I took a teological viewpoint and argued that allowing free access to abortion would produce the most beneficial consequences for those who were “in need” of abortion, be it due to financial, health, or relational reasons. As a pro-choicer, I argued erroneously that taking the life of an infant through abortion was a justifiable means to avoiding poverty, the potential negative health consequences of pregnancy, and the relational vulnerability of being a mother who had to take care of a newborn (especially for survivors of rape and incest). I rightly understood that extending permission to abort these pregnancies meant doing so for potentially all pregnancies, as well as all reasons to end those pregnancies. Even as the examples in my arguments did not necessarily require abortions, I knew that the emotional charge of the examples gave me the best chance at convincing someone to allow exceptions. As soon as I got someone to allow those exceptions, I would accuse the person of opposing abortion situationally, not on principle, and argue that there was no longer reason to restrict abortion on principle. I knew and know that abortion is wrong, but I went through this exercise in mental gymnastics to convince myself that it was excusable. Now, however, I know and acknowledge the constancy of moral absolutes.

Conclusion

As I stated above, moral absolutes are necessary for this framework of morality because absolutes give the judgments of Catholic morality their standard. As Canavan states, “if there are no absolutes, reasoning collapses into incoherence and yields no conclusions” (Canavan, 93). Without the standard of morality that the Decalogue provides, the claims of Catholic morality hold no more sway than the teachings of other ethical systems. The high standards set by Catholic morality, which we can only reach with the help of grace, would repel many from the ethical system. However, with the established moral absolutes that Catholic morality sets forward, the individual can value and strive to maintain the standards for behavior that the framework sets.

Moral absolutes help us understand our ultimate end of union with G-d in heaven. For one to achieve this union with our Creator, it stands to reason that one must exist in accordance with His plan. After all, the only way to become fit for union with Him is to become like Him. Recognizing the validity of moral absolutes is a vital part of living in accordance with G-d’s plan because appreciating and respecting His work in the universe involves acknowledging and following the laws that He put in place for its functioning. These laws are explained well in the Decalogue but spread out to further applications and specifications elsewhere in Church teaching.

-Esther

---

Canavan, Francis. “A Horror of the Absolute.” The Human Life Review 23, no. 1 (Winter 1997): 91-97.

John Paul II. Reconciliation and Penance. December 2, 1984. The Holy See. https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_jp-ii_exh_02121984_reconciliatio-et-paenitentia.html.

John Paul II. Veritatis Splendor. August 6, 1993. The Holy See. https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_06081993_veritatis-splendor.html.

May, William E. An Introduction to Moral Theology. Second edition. Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor, 1994.

#catholicism#catholic#catholic theology#moral absolutes#proportionalism#consequentialism#moral theology#morality

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ethical Frameworks and a Return to Casuistry.

youtube

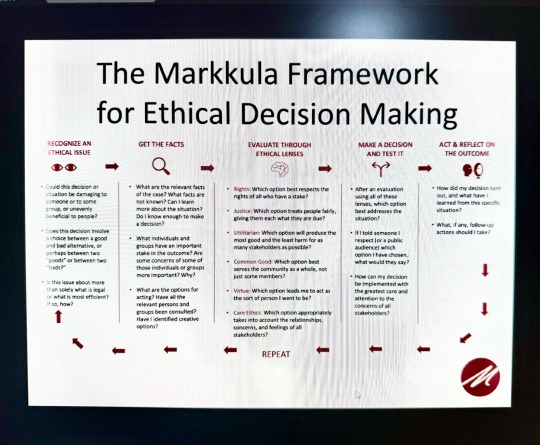

Ethical Frameworks: At a recent workshop I received this decision-making tool from the Markkula Center which I found extremely helpful. It briefly shows the process that needs to be taken when someone has to make an ethical decision. The process is spelled out below.

The following link from the Markkula center has further resources on this.

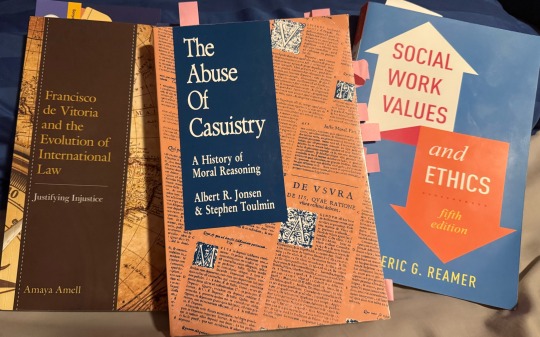

Frederic Reamer presents his own framework for ethical decision making for social workers in his book, “Social Work Values and Ethics.” It is not to dissimilar from what Markkula presents above. In describing the process Reamer offers the following preamble:

No precise formula for resolving ethical dilemmas exists. Reasonable, thoughful social workers can disagree about the ethical principles and criteria that ought to guide ethical decisions in any given case. But ethicists generally agree on the importance of approaching ethical decisions systematically, by following a series of steps to ensure that all aspects of the ethical dilemma are addressed, Following a series of clearly formulated steps allows social workers to enhance the quality of the ethical decisions they make. (Reamer, pg. 88)

Reamer shares the following seven points as an ethical framework for social workers.

Identify the ethical issues, including the social work values and duties that conflict.

Identify the individuals, groups, and organizations likely to be affected by the ethical decision.

Tentatively identify all viable courses of action and the participants involved in each, along with the potential benefits and risks for each.

Thoroughly examine the reasons in favor of and against each course of action, considering relevant codes of ethics and legal principles; ethical theories, principles, and guidelines (e.g. deontological and teleological-utilitarian perspectives and ethical guidelines based on them); social work practice theory and principles; relevant laws, policies, and social work practice standards; and personal values (including religious l, cultural, and ethnic values and political ideology), particularly conflicts between one’s own and others’ values.

Consult with colleagues and appropriate experts (such as agency staff, supervisors, agency administrators, attorneys, and ethical scholars).

Make the decision and document the decision-making process.

Monitor, evaluate, and document the decision.

The point of the process is to make an ethical decision. Many times the decision will be pretty straightforward and the process will be pretty basic. But at times a morally complex scenario will present itself and still, an ethical decision will need to be made. But such decisions will be complicated and it not everyone will make the same decision. To this Reamer tells us,

This does not reveal a fundamental flaw in the decision making framework. Rather, it highlights an unavoidable attribute of ethical decision making: complicated cases are likely to produce different assessments and conclusions among different practitioners, even after thorough and systematic analysis of the ethical issues. After all, reasonable minds can differ. (Reamer, pg. 105)

Reamer’s astute observation here brings to mind a former Catholic moral method that is very applicable to those of us who work with complicated clients and cases.

A Return to Casuistry: Ethics is such a vitally tool for addressing difficult challenges. The workshop I attended was on the challenge of using AI in the social service sector but the night before I had another workshop on preparing our migrant communities for potentially draconian policy shifts that will dramatically impact their lives. In both cases we considered real case studies that presented moral dilemmas. I thought more about this ethical process in light of these two issues.

Case studies are an essential aspect of ethics. Moral principles have a very important role to play as well but as the authors Toulmin and Jonsen have written in their book “The Abuse of Casuistry,”

Moral knowledge is essential particular, so that sound resolutions of moral problems must always be rooted in a concrete understanding of specific cases and circumstances. (Toulmin/Jonsen, pg. 330)

In the video below we hear from a comedian/ethicist Michael Schur who explains how a particular ethical case formed a moral dilemma that shaped his ethical lens.

youtube

In this TED talk Michael Schur, the creator of the Netflix show “The Good Place,” shares his own ethical formation and the framework that he employed to discern the right action. In the midst of his presentation on the ethical dilemma that so moved him he shares that he was becoming “sick to my stomach” as he morally considered the results of his action. His own conscience, his moral intuition, was playing a key role in this dilemma. This intuition had him review ethical literature to evaluate further his action. At the conclusion of his talk he suggest that ethical cases, like the one he presents, can help shape good moral habits. Schur suggests that developing ethical frames of references will help us become better people. It will help us succeed at making better choices and reflecting on our own happiness and the greater good.

Becoming aware of the philosophical ideal of the moral good, accepted virtues for the development of our moral character, existing ethical frameworks, and moral decision-making processes, will grant us a deeper and richer perspective on who we are and how we can become better and people. To become a better person is a fundamental goal that all humans share and ethics is a tool to help shape our humanity.

Contemporary Catholic moral theology tends to focus more on moral principles rather than methodology. Focused on their concern for “intrinsically evil acts” the Church has periodically focused more on principles as moral absolutes where methods or probable moral positions are given less consideration with certain moral positions. This unfortunate development emerged as moral theology attempted to employ a geometric/mathematical approach to ethics with the assumption that ethical problems could be resolved with a rigorous application of moral absolutes.

But in the world of medical or social work ethics it is important to promote case studies and to perhaps bring back a moral system that promoted this form of moral theology. This is what the 13th - 17th century art of casuistry offered. Stephen Toulmin and Albert Jonsen explored this historical contribution to moral reason and address the contemporary need to bring back this branch of moral theology. The authors define their thesis in this way.

Practical moral reasoning today still fits the pattern of topical (or “rhetorical”) argumentation better than it does of formal (or “geometrical”) demonstration. (Toulmin/Jonsen, pg. 326)

Ethical case studies that address particular moral issues allow the ethical framework to respect the role of one’s conscience in discerning the moral dilemma that we each face. The idea of the primacy of conscience has always been defended by the Catholic Church, but more as an idea than as a practice. Toulmin/Jonsen believe that casuistry can help form a practice that allows us to develop our conscience.

In offering this position Toulmin/Jonsen remind us of the role of synderesis which is a component within the individual conscience based on the theory of natural law. It is defined by Aquinas as “a natural disposition concerned with the basic principles of behavior, which are the general principles of natural law.” The moral principles that our religious and educational institutions develop exist within our own conscience as a natural disposition that can grasp and discern their application within the ethical situations we each face.

Aquinas, then, reserves the word conscientia for “the application of general judgments of synderesis to particulars.” This application can be either prospective, in discovering what is to be done in a particular situation, or retrospective, in testing what is to be done in order to discern whether one acted rightly. (Toulmin/Jonsen, pg. 129)

Through the period that Toulmin/Jonsen call “high casuistry” (15th through the 17th Century) many theologians utilized this ethical method to evaluate unique issues that they had not faced before. Until the middle of the 17th century, when Pascal wrote his scathing work, The Pastoral Letters, casuistry enjoyed a preeminent moral authority that allowed moral theologians like Francisco de Vitoria to address unique and particular issues. Vitoria’s 16th century contribution would establish the framework for human rights language, international law, just war, and the ideals of the enlightenment. These cases emerged as casuist like Vitoria analyzed the situation of Europe as the Reformation took hold and the emergence of nationalism. He also evaluated the Spanish relationship with and obligation to the indigenous community in the midst of the American colonial situation. These contributions surfaced because Vitoria had the ability to consider probable ethical opinions on a range of issues that emerged during that time and we now take for granted. But we now face our own unique moral dilemmas and we require the same flexibility to respond to these ethical issues through a rhetorical approach that considers the best probable ethical opinion to our own case studies.

The Markkula Center, Michael Schur, and Toulmin/Jonsen, would all seem to suggest that the moral development of a person is best achieved by the use of ethical frameworks within particular case studies that present a real moral dilemma. You may not always get the right action or make the best ethical decision, but the more you employ and discern these ethical frameworks, the more you achieve a higher ethical standard, the more you become a better person and attain happiness.

One other point needs to be made. The casuist approach to ethics was both a communal and personal one. A contemporary concern may be that casuist may reinforce a subjective or situational approach to ethics that devalues objective principles to the point of being absolutely relativistic. Toulmin/Jonsen do not agree and Vitoria’s use of casuistry suggests that it was not used this way (beyond the controversies of the moral laxists that Pascal reproached).

For the casuists,… informed conscience might be intensely personal, but its primary concern was to place the individual agent’s decision into its larger context at the level of actual choice: namely, the moral dialogue and debate of a community. Conscience was “knowing together” (con-scientia). The dialogue and debate consisted in the critical application of paradigms to new circumstances, but those “paradigms” were the collective possession of people - priests, rabbis or common lawyers or moral theologians- who had the education, the opportunity, and the experience needed to reflect on the difficulties raised by new cases and to argue them through among themselves. (Toulmin/Jonsen, pg. 335)

As I approach the ethics of social ministry there will be many contemporary similarities that is see with how both medical and social work ethics utilize case studies to hone in their own ethical inquiries. In the case of Catholic social ministry I would like to suggest that the method of casuistry should be redeployed to help us develop an ethical approach befitting the social ministries and mission of the Church.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"You could have helped people," said Brutha. "But all you did was stamp around and roar and try to make people afraid. Like...like a man hitting a donkey with a stick. But people like Vorbis made the stick so good, that's all the donkey ends up believing in."

"That could use some work, as a parable," said Om sourly.

"This is real life I'm talking about!"

"It's not my fault if people misuse the--"

"It is! It has to be! If you muck up people's minds just because you want them to believe in you, what they do is all your fault!"

Terry Pratchett, Small Gods

#brutha#om#vorbis#omnians#small gods#discworld#terry pratchett#religion#belief#deity#gods#power#blame#authority#fear#real life#parable#philosophy#theology#morality#could use some work#all your fault

823 notes

·

View notes

Text

What people think the Bible says: Follow all these rules or burn in hell! What the Bible actually says: You can't follow all these rules, so trust in Jesus!

from Christian Nerds Unite Podcast on Facebook.

#christian#bible#jesus#jesus christ#holy bible#christianity#religion#morals#morality#ethics#theology#hell#heaven

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

So… Nick Marini plays Ayden, who is a mortal incarnation of the Dawnfather but at times plays him kind of like he’s Dawnfathers… Jesus, essentially? Like a son of himself, a god born mortal but also a god?

#downfall spoilers#critical role#c3e100#critical role spoilers#while I have issues with christian rules and dogmas on morality#the theology itself can be more interesting#and i know human-gods aren’t just a a christian thing#but it’s interesting#cr spoilers

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

been seeing lots of Chuck-As-Demiurge/"Flawed God" spn meta and it made me realize that my understanding of Chuck is???? not common????

so my hc/understanding was the Chuck Shurley was/is a human prophet who was possessed by God. First in the usual prophetic sense, then later as a "word of God" type prophet, like MAJOR biblical-level power, in order to pass God's direct thoughts/opinions on to Sam and Dean- and then lastly, God took Chuck as a full-time vessel.

so re: this, I kind of wondered if in the finale, the guy Sam and Dean left scrabbling on the ground was... just human Chuck. is it less meaningful? eh, kinda. does it make the finale make more sense? ...yup.

But most importantly. Picture this. You're a writer, creating OCs that you whump/angst/generally torture the CRAP out of, somehow this becomes an incredibly popular book series, you're touring, you're making BANK. Then later, you MEET YOUR OCS, they are REAL, and apparently so is magic, and the "prophet of God" thing that you thought was a writing/inspo device you'd made up is real, and God is talking to you. so uh, what the fuck. then everything goes black

and when you fade back in, its YEARS later, you're beat up and lying in the dirt, and yoUR OCS ARE STANDING OVER YOU, YELLING AT YOU FOR MAKING THEIR LIVES MISERABLE

THE GUYS *YOU THOUGHT WERE YOUR WHUMP OCS*

TELL YOU THAT YOU ARE MORTAL AND WILL INEVITABLY AGE AND DIE LIKE EVERY OTHER HUMAN

AND THEN DRIVE AWAY IN THE CAR THAT *YOU HAD THOUGHT YOU MADE UP*

all before you can get out so much as a coherent "what the fuck is going on"

like I'm sorry. conceptually that's hilarious

the whump OC you made when you were 25: "YOU'RE GOING TO HAVE A NORMAL BORING LIFE AND AGE AND GET OLD AND DIE! FUCK YOU GOODBYE FOREVER"

you:

#spn#chuck won theory#chuck spn#spn meta#chuck supernatural#listen the Demiurge theories are fascinating but have we considered that Chuck may just be Some Guy#washed up YA writer working at costco with the unerasable knowledge that he was POSSESSED BY THE CHRISTIAN GOD#is (human)Chuck good? hard to say. honestly seems like a totally basic kinda boring guy who got in WAY over his head#through no fault of his own#I'm not gonna try to assign morality to The Christian God. “is an omniscient deity who actively desires the apocalypse evil” fuck man idk#thats getting into actual Theology and Religious Studies#but calling God “Chuck” IS hilarious and I think we should keep doing it

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

(If you're not familiar with any of them, read this post).

Put your reasoning in the tags!

#i'm putting christus victor#because it seems to me to properly reckon with the reality of the devil#and theories that don't do that - like satisfaction or penal substitution - make god the obstacle to human redemption#or you get moral influence which i reject because pre-christ people knew that god was merciful (see psalm 130)#plus christus victor differentiates between sin death and the devil#which ransom theory doesn't#christianity#orthodox#theology#atonement#poll

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hedonism Makes You Smarter

Every value we hold dear, every fact we consider indisputable, every thread of irreducible logic we base our reality on can be traced back to something the earliest one-celled microbes realized without even possessing a brain to process it:

Life = Good Death = Bad

At some point in the unimaginably distant past, some microbe mutated to the point where a certain type of stimuli prompted it to either move away or move closer.

And thus ethics / logic / morality / philosophy / theology was born.

The microbes capable of moving away from threats and towards nutriment stood a far better chance of surviving and reproducing than those that did not.

Very quickly, this rudimentary value system became permanently embedded in all life on the planet.

Any organism not embracing this principle quickly gets consumed by other life or wiped out by natural forces.

As we evolved into multi-cellular organisms, some of those cells develop to specialize and capitalize on the “flee death / find food” paradigm. Every new mutation got weighed against this relentless evolutionary razor. Any mutation that didn’t help tended to get eradicated ASAP while those that helped got reinforced.

Sure, some mutations appear useless but in their cases so long as they didn’t impair pro-survival traits.

Eventually some of these specialized cells specialized even further into organs we now call brains.

And within these brains some sort of…abstract (for lack of a better word) consciousness…

Consciousness is oft referred to by philosophers and scientists as “the hard problem.”

And not in the least because – as with pornography – everybody knows it when they see it, but no one can adequately define it.

Some call it the spirit, some call it the soul, some call it psyche, some call it mind, some call it being, some call it identity.

Some claim body and mind are one, yet it is absolutely possible to destroy most of a human’s brain – and by that, who they ever actually are -- while keeping the body alive and healthy.

Others claim body and mind are separate and that in some yet to come golden age we can transfer our minds from these rotting flesh carcasses to perfect, immutable silicon bodies…

…only they not only lack any mechanism for doing so, they can’t adequately define what it is they’ll be transferring.

This is not a trivial matter!

This is of vital importance Right Now to all of us, especially those who choose not to think of it at all. If we are nothing but a batch pf data points in a meat computer, then our whole sense of unique and discrete individual identity evaporates. Any transfer of data points does nothing for the original organism…or its accompanying soul / identity / mind / consciousness.

This is why I think AI will never acquire bona fide self-awareness and consciousness. Whatever grants us possession of such an abstract concept does not exist without feeling.

And these feelings came from the first protozoa to flee death and embrace life.

What we feel in e otions originates in what we feel physically.

We feel pain, we seek to avoid it. We feel hunger, we seek food. These basic sensations steer us to live, and not just live but to live abundantly, to avoid being prey to predators, to avoid conditions that would physically impair us, to seek out what prolongs and enriches our existence (again, not in a monetary sense).

We can see even plants doing this without benefit of anything recognizable as a brain or identity. They grow towards beneficial stimuli and away from harmful ones.

Once brains arrived on the scene, organisms may develop more nuanced means os assessing threat / benefit ratios. Already wildly successful on the most basic levels found in tardigrades and worms, when brains obtained the most rudimentary means of symbolizing the external world and passing that information along to other brains / minds, the race for genuine consciousness kicked into high gear.

At some point this symbolic version of the world began to reside full time in an abstract realm we refer to as consciousness.

Within the physical confines or our brains we conjure up literally an infinite number of symbolic realizations of what appears to be our “real” world – or at least our interpretations of the real world.

I hold this phenomenon to be something vastly different from AI’s generative process where it admittedly guesses what the next numbers / letters / words / pixels in a sequence should be. AI is nothing but a flow chart -- a sophisticated, intricate, and blindingly fast flow chart, but a flow chart nonetheless.

Human consciousness is far more organic -- in every sense of the word. It places values on symbolic items representing the (supposedly) external world around us, values that derive from emotions, not a predetermined logic chain.

You see, in order to create the ethical systems we live by, in order to create the cultures we inhabit, in order to experience genuine consciousness and self-awareness, we must feel first.

This is anathema to both the “fnck your feelings” crowd and to materialists who insist we need to process everything we experience purely rationally like…well…AI programs.

Nothing could be further from the truth, of course.

To differentiate between life and death, being and non-being, all higher functioning brains develop an emotional bond towards life and a hgealthy antipathy towards death.

The mix may vary from culture to culture -- one certainly doesn’t expect a 15th century samurai to share the exact values as a 21st century valley girl -- but they share a common set of core values that can be related to and understood by each other regardless of their respective background.

Because they feel emotionally -- both stoic samurai and histrionic teen -- they create a consciousness that can experience the external world and relate that experience both to themselves and others.

By comparison, when AI correctly predicts "the sun will rise tomorrow" does it actually understand what those terms mean or only that when they appear they usually do so in a certain sequence? This is the Chinese room paradox: Would somebody with a set of pictograms but no way of knowing what those pictograms actually symbolized actually understand Chinese if they figured out by trial and era that certain patterns of pictograms preceded another pattern?

© Buzz Dixon

#consciousness#the hard problem of consciousness#morality#ethics#philosophy#theology#self-awareness#artificial intelligence#AI

5 notes

·

View notes