#misleading graphs

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

I don't think this holds true for PC98 games. You can find sketched memory map sprite sheets for NES and SNES games and I'm sure people were still doing some of it on the PC98. You simply would not have graph paper big enough to do it, requires too many colors. Meanwhile there were packages like Paint Deluxe as early as 1985. Part of the benefit of making games on something like an IBM clone isn't just that it's more powerful, but that power gave you more wiggle room and flexibility in terms of formats and how stuff is stored on disk and in memory. These VNs (or well, the lower quality ones) could be pumped out relatively cheaply. The pipeline was smoother. Part of the reason something like... Metal Slader Glory is so absolutely insane is because it looked like one of these PC88/98 games, but on a much weaker system, where yeah... You'd have to sit there and figure out how to carve up an anime girl's face for both reusability and memory-tetris.

That project went so long there was probably a good mix of good ol graph paper, though they certainly had other tooling too. You can find Japanese studios for 16 bit games using early tablets to draw graphics. Companies were always trying to find ways to do better work faster and easier. While graph paper pixel art probably didn't go away entirely til... god, maybe even the 2000s, the people stuck doing that were left behind, graphically. For some receipts going back pretty far, this post has some cool photos of Sega's digitizer. https://www.tumblr.com/videogamesdensetsu/149092824100/the-sega-digitizer-system-a-tool-used-by-graphic

#not to be rude or anything#It's cool that really old games were made like that#But I don't wanna “Up hill in the snow both ways” pixel art#Can't have anyone thinking this picture was done on graph paper#people already got big enough art complexes#It's like saying medieval peasants died at 37 or something#Some truth to the numbers#but gives you some misleading ideas about the historic reality

73K notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you ever read someone’s argument where they are using a graph and you think “They’re reading that wrong, it’s not supporting their viewpoint as much as they think”?

#I want to correct them#however#I do not care enough about them or the subject in general#I know that realistically I only have a surface amount of information to bring to the discussion/argument#I just know that the graph is misleading#the y axis went up by percentages of 5 ending at 40%#The X axis has the years 1900 1940 1960 1980 2018#this is a line graph so it’s showing huge ass jumps but of course you would with x and y axis like that#in reality the numbers are on steady inclines and declines over 20-40 year periods#probably following world events the economies etc#but it’s more interesting to see the pretty lines jump like my heart monitor after having to run for like half a minute#the largest percentage difference that mattered to the argument was a 7% increase over a 60year period

1 note

·

View note

Text

In case you don't think your figures are professional enough looking this is Carl Linnaeus' figure from his thesis depicting plant pollination.

0 notes

Text

Hey. Hey buddy. You maybe... wanna... run the numbers into those pie charts again?

Especially the Undertale one?

I don't see a way that 15.8k is 25% of a graph while 5.2k is 23%.

Hey guys remind me how many properties there are on ao3 where m/m outnumbers f/f for no good reason

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

Need people to stop saying "that graph is misleading" when the y axis doesn't start at 0.

Yes sometimes graphs are indeed intentionally misleading you with a weird y axis. But I have seen on this website, three times in as many days, and referencing different graphics, people say "that graph is misleading" when the y axis not starting at 0 is for real simply the best way to convey that particular data.

"I initially misinterpreted this graph despite the perfectly reasonably and very well labeled y axis" ≠ "this graph is misleading." Your data comprehension skills just need work. That's a you problem.

#leemursays#mine#mathblr#if you think this is about you#don't worry about it#I'm not vaguing at anyone in particular#this is a widespread problem#I've seen it multiple times lately#and i don't remember the urls of the relevant people#I'm not holding anything against you#don't get defensive#just get better

450 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don’t think Fox believes in fall damage. He 100% believes he can survive any fall, to the great frustration of his medics. He’s got in enough arguments about it that he makes a graph of the height of the fall vs the amount of time spent in the med bay afterwards. While technically correct, the results are misleading because Fox refuses to stay in the med bay longer than 26 hours (that’s their record, he was sedated most of the time but he’s become immune to them).

543 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's so funny to see all of Dream's manipulative and malicious tactics he's always used in dramas to be properly called out.

None of this is new. Dream loves to sound patronizing to belittle his opponents, to downplay, to put things out of context while throwing so many words and explanation and confusion that it all gets lost. Dream keeps responding because the more he says, the more chance there is that the other person will just give arguing with him because why bother and Dream can act like he has the last word.

He is so misleading. Now he's demanding evidence from anyone he interacts with while cherrypicking what he wants to respond to. Evidence does not clear up as much as you might think.

Information is beautiful. Using graphs and screenshots and making use of data to support your points is gorgeous. It's so satisfying to read a well-constructed argument.

...

Misinformation is beautiful. Using carefully selected graphs and screenshots and making selective use of data to support your points and skew the narrative is gorgeous. It's so satisfying to read a well-constructed argument. It's almost impossible to tell it apart from the real thing.

But today, Dream has gone against someone who has a lot of fans, a lot of fans who know Dream very well and who are patient enough to genuinely dissect his arguments. He lashed out at a beloved figure who's had little real drama and it's crazy how obviously weak his justifications are.

Today he's getting a lot of attention from drama but soon enough it'll pass and Dream's left with even less than he had. Hatewatching is a very temporary hit.

He even mainchanneled this stuff so his viewers who only interacted with him on youtube and barely know much about drama have been made aware. His vid isn't that damning in isolation but some of them are gonna be intrigued enough to check out responses and find out how crazy it is.

298 notes

·

View notes

Text

For the past six years or so, this graph has been making its rounds on social media, always reappearing at conveniently timed moments…

The insinuation is loud and clear: parallels abound between 18th-century France and 21st-century USA. Cue the alarm bells—revolution is imminent! The 10% should panic, and ordinary folk should stock up on non-perishables and, of course, toilet paper, because it wouldn’t be a proper crisis without that particular frenzy. You know the drill.

Well, unfortunately, I have zero interest in commenting on the political implications or the parallels this graph is trying to make with today’s world. I have precisely zero interest in discussing modern-day politics here. And I also have zero interest in addressing the bottom graph.

This is not going to be one of those "the [insert random group of people] à la lanterne” (1) kind of posts. If you’re here for that, I’m afraid you’ll be disappointed.

What I am interested in is something much less click-worthy but far more useful: how historical data gets used and abused and why the illusion of historical parallels can be so seductive—and so misleading. It’s not glamorous, I’ll admit, but digging into this stuff teaches us a lot more than mindless rage.

So, let’s get into it. Step by step, we’ll examine the top graph, unpick its assumptions, and see whether its alarmist undertones hold any historical weight.

Step 1: Actually Look at the Picture and Use Your Brain

When I saw this graph, my first thought was, “That’s odd.” Not because it’s hard to believe the top 10% in 18th-century France controlled 60% of the wealth—that could very well be true. But because, in 15 years of studying the French Revolution, I’ve never encountered reliable data on wealth distribution from that period.

Why? Because to the best of my knowledge, no one was systematically tracking income or wealth across the population in the 18th century. There were no comprehensive records, no centralised statistics, and certainly no detailed breakdowns of who owned what across different classes. Graphs like this imply data, and data means either someone tracked it or someone made assumptions to reconstruct it. That’s not inherently bad, but it did get my spider senses tingling.

Then there’s the timeframe: 1760–1790. Thirty years is a long time— especially when discussing a period that included wars, failed financial policies, growing debt, and shifting social dynamics. Wealth distribution wouldn’t have stayed static during that time. Nobles who were at the top in 1760 could be destitute by 1790, while merchants starting out in 1760 could be climbing into the upper tiers by the end of the period. Economic mobility wasn’t common, but over three decades, it wasn’t unheard of either.

All of this raises questions about how this graph was created. Where’s the data coming from? How was it measured? And can we really trust it to represent such a complex period?

Step 2: Check the Fine Print

Since the graph seemed questionable, the obvious next step was to ask: Where does this thing come from? Luckily, the source is clearly cited at the bottom: “The Income Inequality of France in Historical Perspective” by Christian Morrisson and Wayne Snyder, published in the European Review of Economic History, Vol. 4, No. 1 (2000).

Great! A proper academic source. But, before diving into the article, there’s a crucial detail tucked into the fine print:

“Data for the bottom 40% in France is extrapolated given a single data point.”

What does that mean?

Extrapolation is a statistical method used to estimate unknown values by extending patterns or trends from a small sample of data. In this case, the graph’s creator used one single piece of data—one solitary data point—about the wealth of the bottom 40% of the French population. They then scaled or applied that one value to represent the entire group across the 30-year period (1760–1790).

Put simply, this means someone found one record—maybe a tax ledger, an income statement, or some financial data—pertaining to one specific year, region, or subset of the bottom 40%, and decided it was representative of the entire demographic for three decades.

Let’s be honest: you don’t need a degree in statistics to know that’s problematic. Using a single data point to make sweeping generalisations about a large, diverse population (let alone across an era of wars, famines, and economic shifts) is a massive leap. In fact, it’s about as reliable as guessing how the internet feels about a topic from a single tweet.

This immediately tells me that whatever numbers they claim for the bottom 40% of the population are, at best, speculative. At worst? Utterly meaningless.

It also raises another question: What kind of serious journal would let something like this slide? So, time to pull up the actual article and see what’s going on.

Step 3: Check the Sources

As I mentioned earlier, the source for this graph is conveniently listed at the bottom of the image. Three clicks later, I had downloaded the actual article: “The Income Inequality of France in Historical Perspective” by Morrisson and Snyder.

The first thing I noticed while skimming through the article? The graph itself is nowhere to be found in the publication.

This is important. It means the person who created the graph didn’t just lift it straight from the article—they derived it from the data in the publication. Now, that’s not necessarily a problem; secondary analysis of published data is common. But here’s the kicker: there’s no explanation in the screenshot of the graph about which dataset or calculations were used to make it. We’re left to guess.

So, to figure this out, I guess I’ll have to dive into the article itself, trying to identify where they might have pulled the numbers from. Translation: I signed myself up to read 20+ pages of economic history. Thrilling stuff.

But hey, someone has to do it. The things I endure to fight disinformation...

Step 4: Actually Assess the Sources Critically

It doesn’t take long, once you start reading the article, to realise that regardless of what the graph is based on, it’s bound to be somewhat unreliable. Right from the first paragraph, the authors of the paper point out the core issue with calculating income for 18th-century French households: THERE IS NO DATA.

The article is refreshingly honest about this. It states multiple times that there were no reliable income distribution estimates in France before World War II. To fill this gap, Morrisson and Snyder used a variety of proxy sources like the Capitation Tax Records (2), historical socio-professional tables, and Isnard’s income distribution estimates (3).

After reading the whole paper, I can say their methodology is intriguing and very reasonable. They’ve pieced together what they could by using available evidence, and their process is quite well thought-out. I won’t rehash their entire argument here, but if you’re curious, I’d genuinely recommend giving it a read.

Most importantly, the authors are painfully aware of the limitations of their approach. They make it very clear that their estimates are a form of educated guesswork—evidence-based, yes, but still guesswork. At no point do they overstate their findings or present their conclusions as definitive

As such, instead of concluding with a single, definitive version of the income distribution, they offer multiple possible scenarios.

It’s not as flashy as a bold, tidy graph, is it? But it’s far more honest—and far more reflective of the complexities involved in reconstructing historical economic data.

Step 5: Run the numbers

Now that we’ve established the authors of the paper don’t actually propose a definitive income distribution, the question remains: where did the creators of the graph get their data? More specifically, which of the proposed distributions did they use?

Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to locate the original article or post containing the graph. Admittedly, I haven’t tried very hard, but the first few pages of Google results just link back to Twitter, Reddit, Facebook, and Tumblr posts. In short, all I have to go on is this screenshot.

I’ll give the graph creators the benefit of the doubt and assume that, in the full article, they explain where they sourced their data. I really hope they do—because they absolutely should.

That being said, based on the information in Morrisson and Snyder’s paper, I’d make an educated guess that the data came from Table 6 or Table 10, as these are the sections where the authors attempt to provide income distribution estimates.

Now, which dataset does the graph use? Spoiler: None of them.

How can we tell? Since I don’t have access to the raw data or the article where this graph might have been originally posted, I resorted to a rather unscientific method: I used a graphical design program to divide each bar of the chart into 2.5% increments and measure the approximate percentage for each income group.

Here’s what I found:

Now, take a moment to spot the issue. Do you see it?

The problem is glaring: NONE of the datasets from the paper fit the graph. Granted, my measurements are just estimates, so there might be some rounding errors. But the discrepancies are impossible to ignore, particularly for the bottom 40% and the top 10%.

In Morrisson and Snyder’s paper, the lowest estimate for the bottom 40% (1st and 2nd quintiles) is 10%. Even if we use the most conservative proxy, the Capitation Tax estimate, it’s 9%. But the graph claims the bottom 40% held only 6%.

For the top 10% (10th decile), the highest estimate in the paper is 53%. Yet the graph inflates this to 60%.

Step 6: For fun, I made my own bar charts

Because I enjoy this sort of thing (yes, this is what I consider fun—I’m a very fun person), I decided to use the data from the paper to create my own bar charts. Here’s what came out:

What do you notice?

While the results don’t exactly scream “healthy economy,” they look much less dramatic than the graph we started with. The creators of the graph have clearly exaggerated the disparities, making inequality seem worse.

Step 7: Understand the context before drawing conclusions

Numbers, by themselves, mean nothing. Absolutely nothing.

I could tell you right now that 47% of people admit to arguing with inanimate objects when they don’t work, with printers being the most common offender, and you’d probably believe it. Why? Because it sounds plausible—printers are frustrating, I’ve used a percentage, and I’ve phrased it in a way that sounds “academic.”

You likely wouldn’t even pause to consider that I’m claiming 3.8 billion people argue with inanimate objects. And let’s be real: 3.8 billion is such an incomprehensibly large number that our brains tend to gloss over it.

If, instead, I said, “Half of your friends probably argue with their printers,” you might stop and think, “Wait, that seems a bit unlikely.” (For the record, I completely made that up—I have no clue how many people yell at their stoves or complain to their toasters.)

The point? Numbers mean nothing unless we put them into context.

The original paper does this well by contextualising its estimates, primarily through the calculation of the Gini coefficient (4).

The authors estimate France’s Gini coefficient in the late 18th century to be 0.59, indicating significant income inequality. However, they compare this figure to other regions and periods to provide a clearer picture:

Amsterdam (1742): Much higher inequality, with a Gini of 0.69.

Britain (1759): Lower inequality, with a Gini of 0.52, which rose to 0.59 by 1801.

Prussia (mid-19th century): Far less inequality, with a Gini of 0.34–0.36.

This comparison shows that income inequality wasn’t unique to France. Other regions experienced similar or even higher levels of inequality without spontaneously erupting into revolution.

Accounting for Variations

The authors also recalculated the Gini coefficient to account for potential variations. They assumed that the income of the top quintile (the wealthiest 20%) could vary by ±10%. Here’s what they found:

If the top quintile earned 10% more, the Gini coefficient rose to 0.66, placing France significantly above other European countries of the time.

If the top quintile earned 10% less, the Gini dropped to 0.55, bringing France closer to Britain’s level.

Ultimately, the authors admit there’s uncertainty about the exact level of inequality in France. Their best guess is that it was comparable to other countries or somewhat worse.

Step 8: Drawing Some Conclusions

Saying that most people in the 18th century were poor and miserable—perhaps the French more so than others—isn’t exactly a compelling statement if your goal is to gather clicks or make a dramatic political point.

It’s incredibly tempting to look at the past and find exactly what we want to see in it. History often acts as a mirror, reflecting our own expectations unless we challenge ourselves to think critically. Whether you call it wishful thinking or confirmation bias, it’s easy to project the future onto the past.

Looking at the initial graph, I understand why someone might fall into this trap. Simple, tidy narratives are appealing to everyone. But if you’ve studied history, you’ll know that such narratives are a myth. Human nature may not have changed in thousands of years, but the contexts we inhabit are so vastly different that direct parallels are meaningless.

So, is revolution imminent? Well, that’s up to you—not some random graph on the internet.

Notes

(1) A la lanterne was a revolutionary cry during the French Revolution, symbolising mob justice where individuals were sometimes hanged from lampposts as a form of public execution

(2) The capitation tax was a fixed head tax implemented in France during the Ancien Régime. It was levied on individuals, with the amount owed determined by their social and professional status. Unlike a proportional income tax, it was based on pre-assigned categories rather than actual earnings, meaning nobles, clergy, and commoners paid different rates regardless of their actual wealth or income.

(3) Jean-Baptiste Isnard was an 18th-century economist. These estimates attempted to describe the theoretical distribution of income among different social classes in pre-revolutionary France. Isnard’s work aimed to categorise income across groups like nobles, clergy, and commoners, providing a broad picture of economic disparity during the period.

(4) The Gini coefficient (or Gini index) is a widely used statistical measure of inequality within a population, specifically in terms of income or wealth distribution. It ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates perfect equality (everyone has the same income or wealth), and 1 represents maximum inequality (one person or household holds all the wealth).

#frev#french revolution#history#disinformation#income inequality#critical thinking#amateurvoltaire's essay ramblings#don't believe everything you see online#even if you really really want to

241 notes

·

View notes

Note

https://x.com/ferra_ria/status/1817615372104740934?s=46

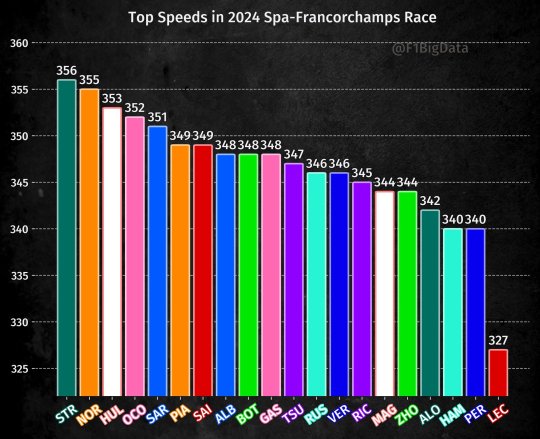

what is that ass top speed omg how is it so low compared to everyone? were we not running a low downforce setup i am confused

This is the graph shown in the tweet. And this is a very good example of how data can be very misleading without context.

So the reason for this is simple. Charles was not in DRS as much as the others. He made passes quickly, while many of these others had longer runs in DRS. The speed difference here is made by DRS, not the car. All this shows is who was in DRS and for the longest. It doesn't show anything substantive about the cars.

And it's pretty clear because while the Ferrari is not the fastest car are you trying to tell me it's slower than the Sauber? Really.

This kph difference is basically the exact difference that comes from DRS. All this shows was that Charles didn't have any long runs in DRS compared to the others. He also made any passes quickly instead of being stuck. Running on the straights without DRS was around 314kph(give or take) for everyone.

Mid field cars often have the chance to hit higher speeds simply because they are more likely to be in DRS for longer.

And this is why data in context is important. Just presenting the raw data this way does not inform anything about the cars and the race and borders on misinformation.

#luci answers#charles leclerc#scuderia ferrari#my beef with big data accounts is never ending when they put out shit like this

120 notes

·

View notes

Note

https://twitter.com/ZakugaMignon/status/1739703106466627976?t=6BRheBvMK4MlCt5gXaj4ig&s=19

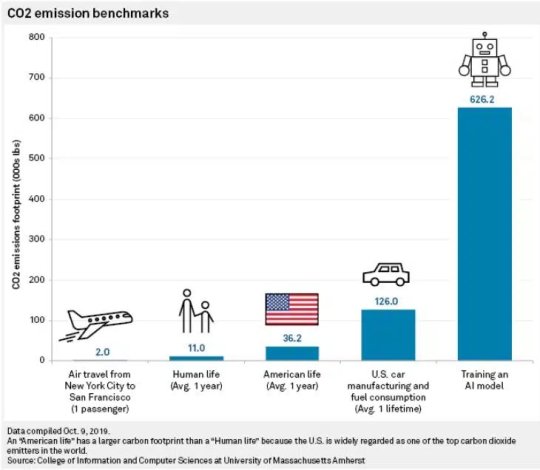

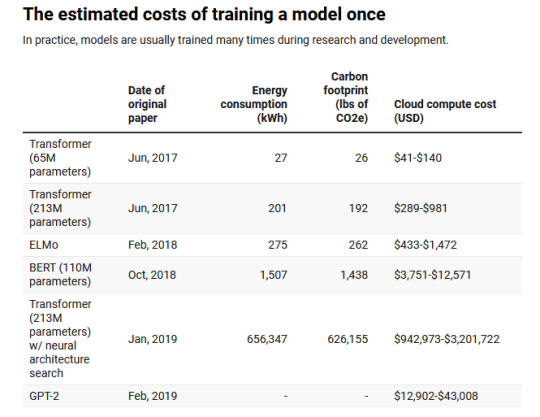

this is a comically misleading graph lol (copy-pasted it below)

like you look at this and obviously think 'wow training an AI model is so much more carbon-intensive than planes or cars' -- but if you look at the actual units being chosen, they're fucking stupid. like, why is the air travel one the only one measured per passenger? the AI model will presumably be used by more than one person. fuck, even the average car will often be transporting more than one person! why is the car the only one that has its lifetime use and manufacturing cost combined when the AI model only has its manufacturing cost and the plane only has the cost of a single flight divided per passenger?

these are absolutely fucking nonsensical things to compare, and obviously chosen in ways that make AI look disproportionately bad (and air travel look disproportionately good, for some reason?). i'm not even touching the profoundly Fucked political implications of measuring the CEO emissions of 'a human life'

but let's, just for funsies, assume that these are reasonable points of comparison -- in 2021, 9 million cars were made in the USA. for the environmental impact of training AI to be even equal to the effects that those cars will have over their lifetimes (which this graph obviously seeks to imply), there would have to be over a million AI models trained in that time. which--hey, hang on a minute, that reminds me, what the fuck is 'training an AI model'! AI models come in all kinds of sizes -- i don't think the machine learning model that the spiderverse animators used to put the outlines on miles' face cost as much to train as, say, DALL-E 3! there is no indicator that this is an 'average' AI model, or whether this is on the low or high end of the scale.

so having just had that above question, i went to look at the original study and lol, lmao even:

the 626,000 lbs figure is actually just the cost of that one specific model, and of course the most expensive in the study. there's no convincing evidence that this is a reasonable benchmark for most AI training -- for all this study's extremely limited set of examples tells us, this could be an enormous outlier in either direction!

so yeah, this is officially Bad Data Visualization, & if you originally saw this and thought "oh, it looks like AI art really has a huge environmental impact!" then, like, you're not stupid -- the person making this chart obviously wanted you to think that -- but i recommend taking some time when you look at a chart like this to ask questions like 'how was this data obtained?' and 'are these things it makes sense to compare on the same scale?', because there's a lot of misleading charts out there, both purposefully and through sheer incompetence.

370 notes

·

View notes

Text

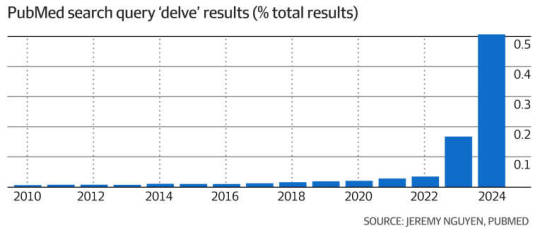

here, this is a better article.

apparently usage of "delve" is appearing in greater numbers in written text but it's unclear whether this is directly linked to AI or simply a language trend.

apparently ai writing includes some words that human writing doesn't include at much higher frequencies, such as the word "delve". supposedly ai writing is using this word with such higher frequency it's misleading data collection, as datasets focused on word usage over time are showing major skews since 2021

#not as massive increase as i thought (the graph is a little misleading)#but significant nonetheless

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

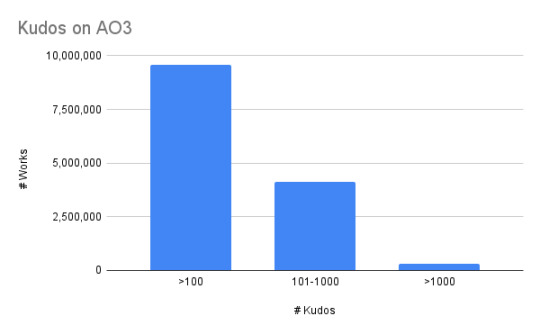

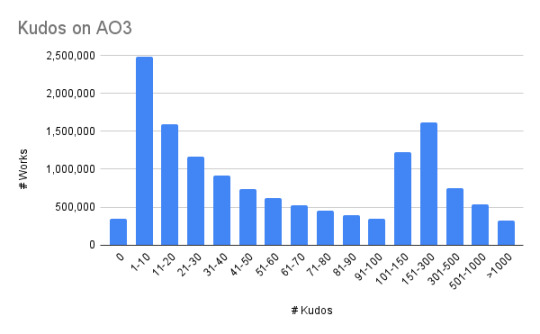

Hey, as someone who has never done statics before, is there a noob-friendly way to calculate how many kudos the average fic on ao3 has? Or does that statistic already exist somewhere?

I kinda feel it would be something like <50 kudos but that’s just me.

--

What kind of "average"?

One thing you have to consider is whether a straight average is misleading.

My guess is that many fandoms have a pattern where the majority of works have 0 or 1 kudos. Then there's some single popular fic with a gajillion kudos. Is an average of 3 kudos representative of that fandom?

It's like life expectancy. People are all: "Everyone in the Middle Ages died at 35!!! Wharrrrrrrgarbl!" Except they didn't. Shittons of people lived to be what we would consider a fairly normal old age now. The average was low because fucktons of small children died. If you made it past 5, you had an okay-ish life expectancy thereafter.

What you most likely actually want is a graph showing X stories with 0 kudos, Y with 1, Z with 2, etc.

You can use the Works Search to search by number of kudos. Currently, I'm getting:

How you choose to break it out really affects the vibe of the chart even if the numbers are all accurate. How you present numbers matters.

So decide what you're trying to say and make the chart brackets reflect that.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

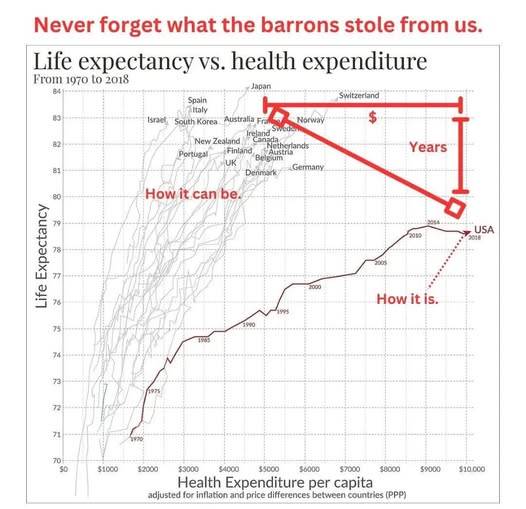

People smarter than me tell me that this graph is a little misleading, but the sentiment on a whole is one I agree with: we need to see some charts and data that show us exactly what being servants to a billionaire class costs the rest of us.

#billionaires should not exist#ceo mindset#ceo down#fuck corporate greed#end citizens united#tax the rich#eat the rich#anti capitalism#healthcare for all#universal basic income

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

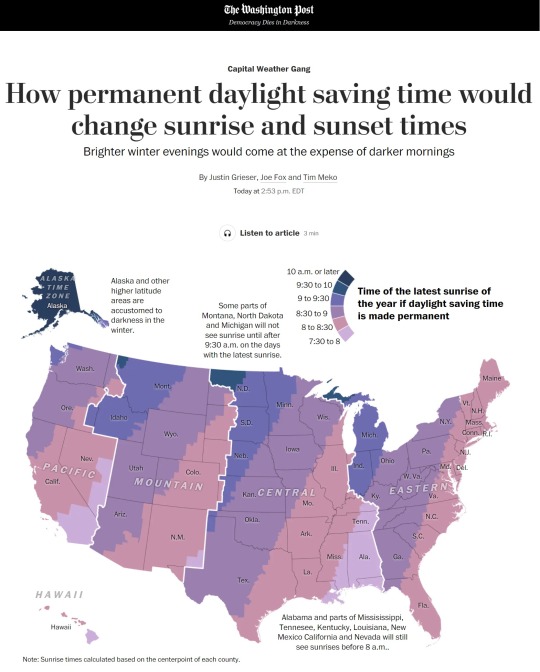

This map is a little bit misleading where it says Alabama and parts of Missisissippi etc will still see sunrises before 8 a.m. - this is for the literal darkest day of the year. Every state will see earlier sunrises on every other day of the year. This map is showing the extreme condition (which is cool! Don’t get me wrong!) but not any of the other conditions. Just wanted to point this out when looking at graphics, since many times they can be misleading and show you what the author wants you to see

How permanent daylight saving time would change sunrise and sunset times

513 notes

·

View notes

Text

I wasn't sure how consent was going to go over in Ashes in the Wind, given that it's a Kathleen Woodiwiss novel, but it turns out the character graph of who is misleading who into uninformed consent is WAY more convoluted than I expected.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

You’re not supposed to be like me. You deserve to be like you.

Never think, “I’m probably not really aromantic, because I’m not as completely aromantic as that person.”

Never think, “I’m probably not really asexual, because I’m not as completely asexual as that person.”

People like me are over-represented on the aromantic and asexual spectra, because we have the time and social appetite to be more visible. It can give the misleading impression that we represent what aromanticism, asexuality, or aromantic asexuality look like.

I was in the middle of writing a 1,500 word essay complete with scatter graphs and shit, but this was important, so for now I’ll just say it, and prove it later, because I think you know this is true, or at least probable:

There are a lot of people who feel like they experience a little less romantic or sexual attraction than other people do, but who still have found a way to make a relationship work. Many of them will never even hear about aromanticism or asexuality, and if they do they’ll think it must apply to someone other than them, because they’re with someone. Their “invisibility” (by way of not self-identifying as aspec) means their ends of the asexual and aromantic spectra are underrepresented or even erased.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

On this scale, 5 and 6 are safely in the middle of the purple numbers.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

On this scale, where 1-4 have excluded themselves, 5 and 6 are on the edge of the purple numbers.

The under representation or erasure of non-self-identifying aromantic and asexuals means you might feel like more of an edge-case or an outlier than you are, because it’s the real edge-cases and outliers—the very asexual or very aromantic—who generate most of the written discourse about aromanticism or asexuality, because we have more time to, and we have a stronger motivation to connect with others like us.

But you belong here. You’re probably the invisible majority of us, and have a lot to teach us about your far-more-complicated end of our spectra.

26 notes

·

View notes