#minoan pagan

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Yesterday I sat up in bed and immediately thought "I Must rewrite That One Hymn, but for Dionysus instead of Jesus." (So if you'd like to scroll past Christian inspired stuff this paragraph is here as a buffer.) I wove in some things from my Minoan pagan practice as well as Hellenic, like the name Divono and a slightly different version of the dolphin myth.

My Dívono, I love Thee, I know Thou art mine

Thy song calls the maenads, and Thy hands bear the vine

My gracious Diónysos, my Savior art Thou

If ever I loved Thee, my Dívono, 'tis now

I love Thee because Thou hast first lovéd me

Thy gift is Thy Joy-- may this Truth set us free!

I love Thee with ivy crowning Thy brow

If ever I loved Thee, my Dívono, 'tis now!

My Brother, I sever Thy bonds from this cross

As dolphins, we leap from this ship at her loss

Thy vines twine like serpents, embracing the prow--

If ever I loved Thee, my Dívono, 'tis now!

#dionysos#dionysos deity#minoan pagan#hellenic pagan#rewritten hymn#reclaiming christianity#sort of#we don't talk about the fact that my phone#thought “tits now” was more likely than “tis now”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

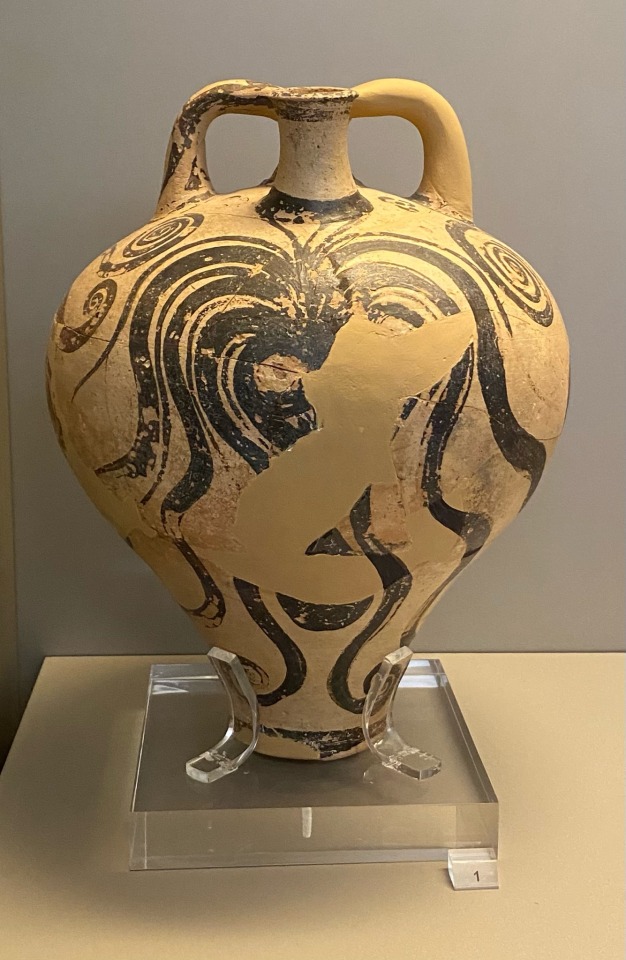

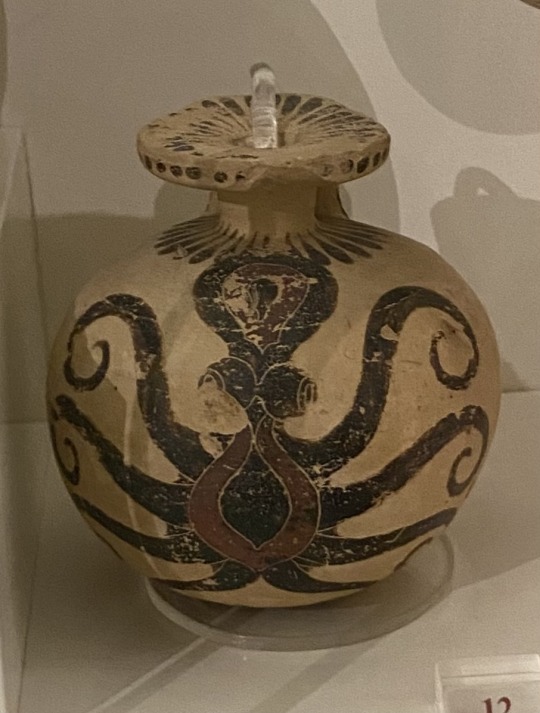

Cephalopod Spotting @ National Archaeological Museum, Athens

#Minoan squid#Mycenaean squid#squids#Ancient Greece#hellenic polytheism#hellenic paganism#athensposting#Minoan#tagamemnon

797 notes

·

View notes

Text

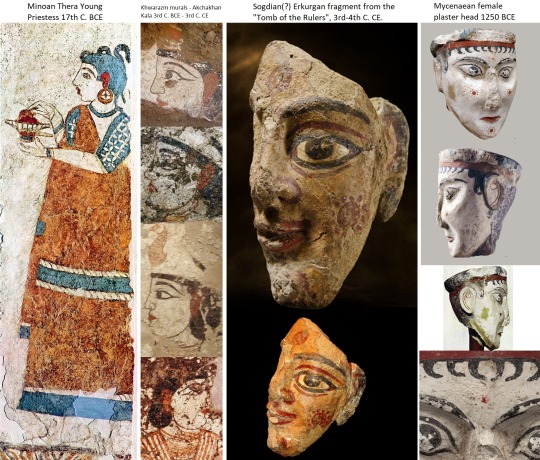

Comparison of Minoan, Mycenaean, Sogdian, & Khwarazm artworks 17th C. BCE - 4th C. CE

When I came across the Khwarazm (aka Chorasmian) murals I remembered this red-eared priestess from Thera. Their large eyebrows, red-painted ears, extremely light skin tone, and general facial features look very similar to each other despite being over 1,000 years apart and in different regions of the world. Other than that their clothing, jewelry, and hairstyle are quite different. I couldn't figure out what the significance of the red ears were, though Jason Earle speculates it might be an artistic depiction of a person hearing something divine from a deity (Cosmetics and Cult Practices in the Bronze Age Aegean? A Case Study of Women with Red Ears). These are the only images I've come across, that I can recall, of people with their ears painted red so I felt like comparing them.

The Erkurgan fragment has red solar symbols very similar to the Mycenaean plaster head. Again these two pieces of art are over 1,000 years apart and in different geographic locations. I don't know who the Erkurgan fragment should be attributed to, but this was a place in the heart of Sogdiana. I assume it represents a Sogdian because of location and time period, but that's just my assumption. Solar symbols appear in basically all civilizations, but I've never come across these specific red styled ones (that I can recall) except in these two instances. In both instances they appear on the cheeks, forehead, and probably the chin (the Erkurgan fragment's chin is damaged but seems to have some red paint). Again, seeing this unique symbol made me feel I should compare the two. From what I've read all the images here are generally thought to be depictions of females with religious significance.

#minoan#mycenaean#art history#ancient history#ancient#art#antiquities#history#paganism#pagan#goddess#priestess#indo european#ancient art#archaeology#anthropology#sogdiana#ancient greece

293 notes

·

View notes

Text

Late Bronze Age Aegean inspired Athena

(Methodology below)

Ok, so I've taken a bit of Classical inspiration as well. I read somewhere that her Peplos was saffron and purple so I took that colour scheme and was reminded of the artwork from Pylos. This lead me to being inspired by the Battle Frieze (Pylos) for the Gigantomachy detailing in her skirt. The colour scheme for the skirt is thus tans and purples for her skirt. Minoan artwork has shown more evidence for depictions of skirts with scenes and scenery on them so that aspect is perhaps more Minoan inspired.

The bodice and the apron both are inspired from the Necklace Swinger in the Saffron Gatherers wall art from Xeste 3 (Akrotiri). I've put crocus flowers as an embroidery detailing on the bodice as it is saffron dyed. The apron takes the design from the necklace swinger as it always makes me think of the night sky (due to colours) and I figured that would make an appropriate overgarment for the story of the gods vs the giants.

The aegis is blue and gold. I chose blue because Zeus has also been associated with the aegis and I wanted to add a connection to him (blue, sky god). Blue (glass) and gold was also a popular Aegean colour decision, which can also be seen in the glass diadem (wave/bracket bead) she wears, connected to a boar tusked helmet. A blue cloak with gold tassels is also somewhat inspired by the sword wielding figure in the fresco from Mycenae's cult centre although with less tassels. I've added two glass necklaces inspired by Mycenaean glass beads. She also has glass beads in her hair, something that is seen in several female figures in Minoan and Mycenaean art.

The snake is both a tie in to the Aegean Snake Goddess but also Athena's ties with snakes (Erichthonius and Medusa both have snake and Athena links, so this may be where the Classical stuff ties in, I'm less certain on the Classics stuff).

She stands in front of an olive tree on an acropolis (meant to be the acropolis of Athens but no way to identify that so could be any).

#Athena#Athens#Greek Mythology#greek myths#tagamemnon#pagan#Hellenism#Mycenaean#Minoan#Bronze Age Aegean#Greece#Aegean#Ancient Greece#archaeology#classics#my art

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

From what we can figure, the sun was a female entity in Minoan religion (Nanno et al 2013), possibly related to the “snake goddess”, perhaps via a “pan-goddess” caveat. Many greek goddesses (Rhea, Demeter, Artemis, Cybele, et cetera) are associated with lions; the lioness as a sun symbol is well attested in Hittite and Egyptian religion, and was probably a common Middle Eastern motif wherever solar goddesses were relevant.

The bull was relevant in minoan religion to the point that it is one of the most well known aspects of this culture. The “Moon Bull”, as it is, has been connected to the sun by classical authors, exposing the typical “every god is a sun god, every goddess is a lunar goddess” nonsense. However, the bull is a generally lunar symbol in the Near East (semetic, where it is connected to the many moon gods, anatolian, where it is similarly connected to the moon gods, even greek and egyptian, where it is associated with Selene and Dionysus and Osiris respectively), and a masculine moon god role can comfortably be implied.

So, basically:

Lion Sun Goddess

Bull Moon God

However, this leaves us with two hiccups:

– Talos, the “greek Helios”, which is the de facto word for “sun” in Crete and whose use may extend further back in time. Zeus as Tallaios is a solar god. That said, since Zeus Tallaios is more of a “death and rebirth” deity (mind you, almost no solar deity is one), it may call into question the status of Talos as originally a sun god.

– The Minotaur’s true name is Asterion. This has been interpreted as a vestige of solar symbols, since the “labyrinth” would instantly become the zodiac. That said, “Aster” and it’s derivatives are rarely applied to the sun outright, and could suggest a more esoteric stellar meaning.

It’s possible that, like ancient egypt, russia and india, the Minoan Civilisation perceived the sun as both male and female depending on the context. I’m leaning with a generally “Sun Lioness” for a solar figure and Talos as specifically the body of the sun.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pouring one out for Iphemedeia (Iphigenia) and Helen who started out as goddesses before regressing to humans in tales that later ascended. I'd include Ariande but that's still a big what-if because we don't 100% know she's the Lady of the Labyrinth, we can only guess as much as we can about Athene being Minoan too as the Master of the Home.

Pouring one out for the historical worship relationship between Hera and Hermes pre-Archaic Greece. *I'd say the Mycenaean era only, but we don't know if it started earlier than that

Pouring one out for the surviving harmony Hermes has with goddesses as a goddess' god (as I affectionately call it). If nothing else, a surviving part of the higher importance/preeminence of goddesses regionally.

*if you're curious to learn more I won't answer, just rely on your preferred search engine and libraries. Me saying anything won't help you cultivate research skills on your own. Just be painfully specific with what you're searching for and abuse "" around words you want focused on.

#dorian's polytheism diary#hellenic polytheism#helpol#hellenic paganism#hellenic gods#hellenic deities#mycenaean religion#minoan religion#mycenaean recon

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

✨‿︵‿︵୨˚̣̣̣͙୧ - 🌊 - ୨˚̣̣̣͙୧‿︵‿︵✨

Hello and Welcome Friend!

This is a devotional blog to Ariadnê

The names Ether!

Adult | They/She | PST

Asks are open for anything related!

I use mobile so please excuse the weird

formatting on PC.

‿︵‿︵‿︵‿︵‿︵‿︵

BASE ~ ( @wanderers-inn )

MAIN ~ ( @psychopomp-recital )

🧶‿︵‿︵*+:。.。 🐂 。.。:+* ‿︵‿︵🧶

#about the author#ariadne worship#devotional blog#ariadne#art offerings#digital altar#greek mythology#dionysus x ariadne#ariadne goddess#ariadne and dionysus#art#deity work#deity worship#pagan blog#helpol#hellenic polythiest#ariadne x dionysus#dionysos#devotee#pagan devotee#dionysus#hellenic worship#pagan#death witch#digital offering#minoan#online altar

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

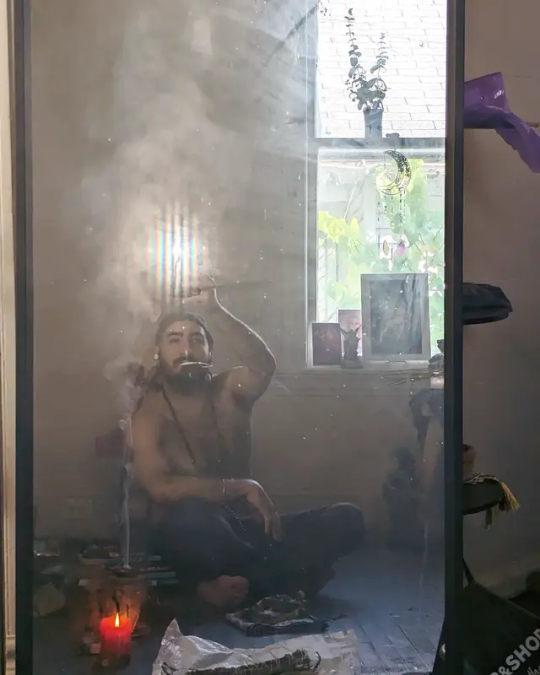

Sorcery & Brujería without filters without makeup, cause there is more happening in the behind the scenes than what people actually see.

Working transmutations at @thewitchscabinetcny (on Instagram)

Xxo. Elo 🌺🌹🐒

#wicca#witchcraft#magick#magic#witches#pagan#male witch#male wiccan#brujo#brujos#paganism#minoan witch#minoan brotherhood#minoan brother#Espiritismo venezolano#urban shaman#Spirit junkie#spirit worker#spiritual Worker#wiccan

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

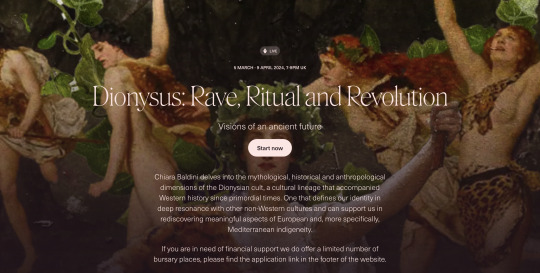

Chiara Baldini is currently running a gorgeous, image-saturated course for ADVAYA.LIFE on Dionysus: Rave, Ritual and Revolution.

She delves into the mythological, historical and anthropological dimensions of the Dionysian cult, a cultural lineage that accompanied Western history since primordial times. One that defines our identity in deep resonance with other non-Western cultures and can support us in rediscovering meaningful aspects of European and, more specifically, Mediterranean indigeneity.

This is part of her PhD work at the California Institute for Integral Studies and a longtime fascination of hers.

XLE.LIFE's Kai Altmann is enrolled and enthralled in the course as a guest.

ADVAYA.LIFE offers regular free webinars, paid courses and meetup events, with a primary hub in London. Focusing on ideas around spirituality, culture, history and theory, they present comparative lectures and exploratory discussions on pressing de-colonial and holistic issues, featuring some of the world's leading thinkers on the topics. Vandana Shiva and Timothy Morton have been recent presenters!

(Bursaries are available for the courses, apply at their site.)

#advaya#advaya.life#chiara baldini#rave#revolution#ritual#dionysus#minoan#pagan#pre-patriarchal#fertile crescent history#indigineity#queerness#pre-western#feminist#shamans#ecstatic#ecstatic dance#mediterranean#crete#greece#rome#xle#xle.life

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cretan "Labyrinth" Temple on the Papoura Akropolis. First discovered in June 2024.

#crete#labyrinth#temple#dungeon#legend of zelda#zelda#archaeology#minoan#animal sacrifice#banquet halls#worship#communal worship#excavation#site#bronze age

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Poetry for Minoan Deities

SO I’ve been writing poetry for a couple of months as part of my university coursework, and I’ve been writing about some Minoan deities. Now if you haven’t seen my posts about Asterius (the minotaur), you can find them here. I’ve worked with him for almost a year at this point, and these poems are a reflection on his family and some of the other characters that play a part in the Minoan section of Greek Mythology.

What I’m wondering is if anyone would like to read the poems? The ones I have so far are about these deities;

- Asterius

- Minos

- Pasiphae

- Britomartis

- Europa

- Androgeus

- Theseus

- Glaucus

- Dionysus Zagreus

I’m not super confident about my poetry but I wanted to know if anyone would want to read them anyway. They’re particularly niche/impossible deities to find anything for, and I thought someone might have an interest in them.

#minoan#myth of the minotaur#asterius deity#family of Asterius#asterion#minos#pasiphae deity#theseus#britomartis#europa deity#androgeus#glaucus#dionysus zagreus#zagreus#knossos#poetry#greek pantheon#pagan#hellenic pagan#witchcraft#deity work#deities#deity#deity worship#minoan paganism#deity poetry

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Great Goddess Ariadne most high;

The spider's web you weave into tapestry

As glowing and vibrant as your spirit.

Every where you go, joy and abundance blossoms.

From the lands of the living, where you kiss the scythe that feeds,

To the lands of the dead, where your honey-sweet nectar nourishes.

Love and light are your cape

That guides you through the labyrinth.

Wrap us with your blessings too,

And we shall give thanks everlastingly to you.

- HP Oboyski

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I need to get back into my faith, I've been astray too long

1 note

·

View note

Note

About this post, out of curiosity, when do you think it all started? Is there research on like how far back it goes? It obviously isn't inherent to human nature; I know it's not. Is it just one of those toxic things that started from the beginning of organized religion :( ?

There's research, but there's a lot of controversy on when/how patriarchy developed. The most important thing to note is that Greek/Roman/Chinese/Japanese style misogyny is not universal and has not always been the norm. Societies differed a lot in how much power and autonomy women had. At the same time, we must be conscious even the 'best' societies of the past still had faults surrounding women.

Some places to start are:

Alice Evans: Ten Thousand Years of Patriarchy: This article looks at it from an economic and cultural perspective. I strongly recommend reading her Substack, where she travels around the world interviewing Third World Women and Feminists to see why their women's liberation movements have succeeded or failed! From the linked article:

Our world is marked by the Great Gender Divergence. Objective data on employment, governance, laws, and violence shows that all societies are gender unequal, some more than others. In South Asia, North Africa and the Middle East, it is men who provide for their families and organise politically. Chinese women work but are still locked out of politics. Latin America has undergone radical transformation, staging massive rallies against male violence and nearly achieving gender parity in political representation. Scandinavia still comes closest to a feminist utopia, but for most of history Europe was far more patriarchal than matrilineal South East Asia and Southern Africa. [...] Why do some societies have a stronger preference for female cloistering? To answer that question, we must go back ten thousand years. Over the longue durée, there have been three major waves of patriarchy: the Neolithic Revolution, conquests, and Islam. These ancient ‘waves’ helped determine how gender relations in each region of the world would be transformed by the onset of modern economic growth.

Another thing to remember/consider when it comes to studying the past is how few resources we have. We only know so much about how pre-historical humans organized their societies. Colonialism destroyed evidence of other societies with different ways of approaching gender. Many of the great apes we study are endangered. And literate societies happened to be patriarchal societies (likely related to literacy going hand in hand with bureaucracy and agriculture and the development of a state?) so we don't know as much as we could about women in literate regions.

Organized religion definitely codified a lot about patriarchy, but the major religions (Christianity, Islam, Buddhism) arose in regions of the world that were already patriarchal. So it's kind of a chicken and the egg problem when it comes to patriarchy and religion. We know that religions that worshipped goddesses, like Greek and Roman paganism and Hinduism, can still coexist with sexist societies.

These aren't great answers, but it's a big question and there are a lot of people working on answering it! It ties back into the bigger question of what our human ancestors were like, and whether we're kind of doomed to violence and xenophobia or whether there are alternatives. Some other books I've read that may be useful reading on this front are:

The Dawn of Everything. A long book, but it's a tour of human history and different societies and ways of organizing society. One of the chapters is on women, if I recall correctly.

Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years: Women, Cloth, and Society in Early Times. Women have been working with cloth for a very long time. In some societies, this allowed women a high degree of status (see the Minoans!) and in others, women were worked to the bone producing textiles (Ancient Egypt).

The book "Demonic Males" looks at the birth of patriarchy from a primatology perspective. Our ape ancestors show male-dominant behaviors and societies. It's controversial the extent this is directly responsible for misogyny and male violence, but I think it's likely that our ape inheritance influenced the structure of early humans - so we basically have a lot of baggage.

Broadly speaking, reading books on feminist anthropology will help you, because a lot of what we know about patriarchy is based on highly literate societies, which as we established, are also agricultural societies with bureaucracies and a hierarchical culture. That's hardly representative of the human condition. As an example, look at Inuit society - on the one hand, there is arranged marriage and all that it implies; on the other, we do not have the same ideals of silent women who stay at home - women are valued members of the society and their skills are explicitly recognized as necessary for survival. Compare Western cultures that view domestic tasks as "support" tasks while the "real" work is done by men.

Finally, this one is a bit old (1974), but it may give you a starting point for understanding feminist anthropology and the search for the origins of patriarchy: "Is Female to Nature as Male is to Culture". It can help us understand how female subordination manifests itself in different cultures, and to know what to look for.

I hope this has been helpful. If anyone can recommend good books on the origin of patriarchy/female subordination (especially for non-Western cultures), please feel free to add in the replies or reblogs!

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Minoan Gods

Decided to take an old article and repackage it for the tumblr audience.

The double-edged axe or labris, likely the least controversial thing written here.

To honor the latest release of Minotaur Hotel I decided to do an article on what is known of the Minoan deities.

Known as the “first European city-makers” and a distant precursor to Greece, what is called the Minoan Civilization after King Minos of Crete was a mysterious Bronze Age nation that governed Crete and neighbouring parts of the Aegean. Its age, likely influences over posterior Greek (and by extension western) culture and unique art has long made it a subject of mystique and intrigue. Whereas it’s the several still undeciphered scripts and languages or the fact that it seems to have a rare genuinely matriarchal society, it seems the countless research and academia only raises more questions than answers.

One such well documented but ultimately unsuccessful endeavour is identifying the pantheon these people worshipped. It is strongly speculated that Minoan Crete was theocratic (Kristiansen & Larsson, 2005, among several others) and several art either represents cultic activities (such as the famous bull leaping) if not gods themselves, but in the absence of the proper written word this is beyond impossible to ascertain. The implications of understanding Minoan religion are very clear, as beyond offering a snapshot to the lives of these people it also bears the potential implication that many Greek gods and mythological figures ultimately had their origins here.

To completely compile, summarise and synthesize all that has been written on Minoan religion is a task far too vast to implement, so here are some of the most widely agreed upon gods.

Queen of the Gods

Snake goddess figurine by C messier. The most well known Minoan possible religious artifact, it’s still not clear if these figurines represent a goddess, multiple goddesses or human priests.

By far the most well kown figure attributed to Minoan religion is the Queen or Mother goddess, sometimes known as “Snake Goddess” due to an abundance of figurines depicting women holding snakes. Perhaps surprisingly (or not given the second paragraph), she’s not actually attested anywhere, given that Minoan scripts haven’t yet been deciphered, but her existence can be inferred due to a variety of factors:

Female figurines are by far the most common representation of what could be interpreted as a god in Minoan sites. Chief among these are the aforementioned “snake goddess” figurines. While there is considerable debate on whereas these truly represent deities (plural or singular) or mortal priestesses, they are comparable to apotropaic depictions of surrounding cultures, most notably those of the latter Athena Parthenos which similarly is associated with serpentine iconography as controlling these forces of chaos (Ogden 2013).

The fact that Minoan society was matriarchal in nature, which would lend credence to the supreme being in their cosmology being feminine in nature. While a dominant female deity does not always correlate to a matriarchal society (i.e. Amaterasu, Virgin Mary, et cetera), the opposite, a matriarchal society with a masculine supreme god, is yet to be documented (though see below).

Several Greek mother goddesses such as Demeter and Rheia are thought to have a Cretan origin (Mylonas 1966, Sidwell 1981 among several others), so it’s not terribly hard to see them as “descendents” of this Minoan deity.

The Philistines, contray to biblical assertions on Dagon worship, seem to have favoured a goddess as their primary deity (Schäfer-Lichtenberger 2000, Ben-Shlomo 2019). The Philistines, through genetic legacy and material culture, are now understood to have had an Aegean origin, so again seeing this as a continuation of a Minoan goddess is plausible.

Several names have been speculated for this deity, usually along the lines of the author’s interpretation of Minoan scripts (which should be noted, are not only undeciphered but very likely don’t mention deities at all, since all we have seem to brief texts likely attributed to tax reports). The name “Rhea” doesn’t seem to be of Indo-European origin (Nilsson 1950, Sidwell 1981), making it very likely that this is a theonym with Minoan origins. The same applies to Ariadne (Alexiou 1969) and possibly also Athena (Beekes 2009). Conversely, the Philistine goddess is possibly attested as “Ptgyh” (Ben-Shlomo 2019), a name that is speculated to be related to Greek “Potnia”, “mistress”. In all likelihood, such an important goddess likely was known by a variety of epithets.

Fertility is naturally considered a major function of this mother goddess, but perhaps in ways one might not expect. An emphasis on solar worship has been noted due to temple arrangements and material objects such as “frying pans” with solar iconography (Ridderstad 2009), suggesting that, rather than an earth goddess as one might expect, this was a solar goddess. Solar goddesses are known from a variety of Near Eastern cultures such as Egypt (Sekhmet, Hathor), Anatolia (Arinniti, Istanu, Estan, Wurunsemu) and Canaan (Shapash) so a solar interpretation of the Minoan supreme goddess isn’t unusual. In particular, this might imply a more “chthonic” interpretation of the sun than the Classical “object in the sky”, due to temple angles tressing sunrises and sunsets (Ridderstad 2009), whch is consistent with the Hittite notions of the sun goddess ruling the underworld. Regardless, as noted below in Talos there is also possible evidence for a Minoan male sun.

More unambiguously, this goddess had a civil and possibly domestic function. As noted above snake goddess figurines might be apotropaic in nature, used to ward off evil spirits or more mundane threats like snakes. If Athena is derived from this goddess then a role as the protector of the palace is also implied given Athena’s role in the Mycenaean era, and both Ariadne and Athena are associated with weaving. Conversely, so are solar goddesses in other places, like the Baltic Saule or the Turkic Gun Ana, as the rays of the sun are easily linked to threads, further suggesting this role for the Minoan goddess. Both Rhea and Demeter are also associated with lions, animals that not only are symbolic of the sun but also of a notable sun goddess across the sea, Sekhmet.

The fact that the Minoan ruling goddesses was the possible genesis for several Greek goddesses like Rheia, Demeter, Ariadne and Athena suggests a rather extensive and important function in ancient Cretan religion. Conversely, it might also suggest that what we might attributing to a single goddess was in fact several different deities, but as deities overlap and flow into one another it is possible that these goddesses were either seen as one or acquired independent identities several times throught Minoan history.

The Bull God

Bull-leaping fresco. A stapple of Minoan art.

The bull is extensively depicted in Minoan art. Most common are bull-leaping frescos depicting youths of both genders leaping or interacting with bulls, suggesting this was a common Minoan sport and perhaps even a religious ritual. But bulls are depicted in many other contexts as well, and as such the existence of an actual Minoan bull god is frequently speculated upon.

In Near-Eastern cultures, bulls are both solar and lunar symbols. On the one hand, the bull’s horn/s resemble/s a lunar crescent, and indeed not only are Middle Eastern male moon gods like Nanna and Suen associated with the bull but even the Greek Selene is described as having a chariot pulled by bulls, suggesting that not even a shift towards a feminine moon deity erased this iconography. On the other hand, a bull is a powerful animal and thus worthy of male solar gods, most notably the Mesopotamian Marduk (literally “calf of the sun”). Sometimes both interpretations show up in the same culture: in Egypt the Apis bull is associated both with Ra and with Osiris as Yah (the moon). Perhaps the same applied to ancient Crete (again, see Talos below), but a lunar bull would certainly be a vivid symbol contrasted against the sun goddess.

The bull is associated with Dionysus which otherwise is mired in more “exotic” symbols, suggesting that the putative “Minoan Dionysus” might be the bull god. It has long been speculated that the bull god is a male youth and son and consort to the queen of the gods, though women are also depicted bull leaping.

The Greek minotaur has long been speculated to be a remnant of the Minoan bull god, not without reason being so throughly linked with Crete as a concept. In this case, the monstrous depiction is either fully discontinuous from older practises or defamatory, with my personal two cents that it is also a jab against the bull gods of the Phoenicians, accused at the time of human sacrifice by the (infant killing) Greeks. Asterion is said to be the birth name of the minotaur by Pseudo-Apollodorus, but I wouldn’t read much into this since this name (literally “starry one”) is a common Greek name for many figures both historical and mythological, and at any rate a recent Indo-European name at odds with the most likely Pre-Greek Cretan languages.

“Dionysus”

“Prince of the Lilies” fresco, often but by no means universally interpreted as a male youth figure.

There is extensive evidence of wine cults in Minoan Crete (Kerényi 1976). This, combined with the Mycenaean depictions of a bull-horned Dionysus (or “di-wo-nu-so” as it is) seems to point to a Minoan origin for this god. “Dionysus” is an Indo-European name connected to Zeus and other sky father figures but the actual character of the god is not easily identified in the PIE world, suggesting a Pre-Greek, local origin. A possible exception is the Lusitanian god Andaeico (Teixeira 2014) which might resemble the putative “flower Dionysus” (see below), but this deity is himself not well understood and might be from an ancient Iberian stratum in Lusitanian culture.

The Mycenaean Dionysus is a figure with stronger ties to death and rebirth than revelry necessarily but the evolution from “eldritch god” to “party dude” might not have been as linear (geddit) a concept as one might expect. Male figurines thought to represent a young god increase in popularity in later stages of Minoan history (Vasilakis 2001) as do male youth figures often identified as “prince of the lilies/flowers” which alongside the wine cults is closer to the Classical Dionysus than the Mycenaean or later Orphic one. However once more in the absence of deciphered scripts it is impossible to say for certainty that these figurines represent deities let alone are Dionysus. Hell, the “flowery figures” have even been interpreted as female at times.

If an actual god, the “Minoan Dionysus” might very well be identified with the bull god, as the bull is a rather odd symbol for the “exotic” attributes the Classical Dionysus is associated with. Ariadne in Greek myth does get hitched with Dionysus; an imbalanced, reversed remnant of the male youth/Minoan queen goddess pairing perhaps?

Talos

Talos by laura Jastrow.

Perhaps the only Minoan or at least Cretan god we may truly known by name is Talos. In Greek myth Talos is best known as the strange automaton made by Hephaestus, but it was also the Cretan word for “sun”, analogous to “Helios” of mainland Greece according to Hesychius of Alexandria. Zeus was worshipped in Crete as Zeus Talaios, who was associated with the sun, and the Tallaia was a spur of Mt. Ida associated with sunrise rituals (Nilson 1923).

This association of Zeus with Talos is as peculiar as it is extensive. Zeus, a god whose origins are well documented to be Indo-European in nature, is held in Greek myth as born and raised in Crete, and Cretan depictions of Talos differ from those of mainland Greece in having wings. Further, the seduction of Europa by Zeus as a bull links the Classical Zeus to Crete in a very fundamental way. This seems to indicate a rather through syncretism between the Greek/Mycenaean sky god and this indigenous Cretan deity, which in turn implies a rather relevant role to the Minoan Talos.

Conversely, outside of Crete Talos is an enigmatic figure, as noted by Pausanias himself which seems more confused than anything. Certainly, the story of a pre-sci-fi robot is weird, let alone how it relates to an ancient Cretan god, linked to the supreme god of all Greeks down to his very birth.

Talos is truly an anomaly. A solar god which was important enough to warrant syncretism with Zeus, in a matriarchal culture where the sun seems to have been traditionally the supreme goddess herself. Crete was likely never a monolith even at the height of Minoan rule, but all current signs point to Talos being an ancient Cretan deity from before PIE influences in Greece, and he seems so out of place.

My personal two cents is that Minoan cosmology was similar to that of the Hittites and other Anatolian cultures, where the sun is male during the day as it travels through the sky and female at night where it rules the underworld. Talos’ syncretism with Zeus therefore would be derived from representing the male, skyward aspect of the sun, corroborated by worship at the Tallaia. In the original Minoan religion Talos was probably lesser compared to his female aspect (which even as a chthonic deity would easily be accepted as the supreme power; even Mycenaeans favoured the chthonic Poseidon to the celestial Zeus after all), but his roled ensured syncretism with the king of the gods once Crete was conquered.

Britomartis

Candiacervus by Peter Schouten.

Britomartis is possibly another deity we might know from a genuinely Minoan or at least Cretan name. Solinus claims it is “sweet virgin” in Cretan and the name doesn’t seem to have Indo-European roots. If true, I’d imagine this theonym is more due to syncretism with the Greek Artemis if anything as I doubt ancient Minoans cared much about virginity as a concept, though Artemis herself may be derived from this deity. Some archaeologists have further suggested that it is an euphemism for the deity’s actual name, since being a goddess of the wilds saying it might have been unwise (Ruck 1994). Another name attributed to her is Diktynna, “hunting nets”, or simply Dicte/Dikte (unsurprisingly, she named said mountain, and was likely its spirit). I’ve never seen the etymology of this name tracked, so I can’t say for sure if it is Greek or Pre-Greek in origin

Britomartis is in Greek myth a mere oread or mountain nymph, said to have invented hunting nets. She is said to have fled Minos’ lust, a tale that even Siculus expressed disbelief at due to her divinity. Thus, although greatly diminuished by Hellenistic times, she was still clearly held to be a deity, and still seems to have been worshipped in Crete during Classical times, frequently appearing in coinage as a winged figured. She is equated to Artemis, a goddess associated with the wilderness and mountains, and it can be assumed she represents a similar “lady of the beasts” archetype. Artemis herself has a name of unclear etymology, and could be of Minoan origin, being perhaps another name for Britomartis.

Some authors tempt to lump Britomartis with the Minoan mother goddess, but to me these seem like clearly distinct figures. Whereas the queen of the gods is a civic, fertility and possibly solar figure, Britomartis is alcearly a goddess of the wild places, perhaps even more specifically the embodiment of Mt. Dicte. Of course, overlap between these two goddesses likely happened at several points in Cretan history.

And that’s it for now.

Other Minoan gods have been positted, including a sea one (naturally), but they aren’t sufficiently supported by everyone in the field at large, so I won’t bother.

References

Kristiansen, Kristian & Thomas B. Larsson. The Rise of Bronze Age Society: Travels, Transmissions and Transformations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Ogden, Daniel (2013). Drakon: Dragon Myth and Serpent Cult in the Greek and Roman Worlds. Oxford University Press. pp. 7–9. ISBN 9780199557325 – via Google Books.

George Mylonas (1966), “Mycenae and the Mycenean world “

Sidwell, R.T. (1981). “Rhea was abroad: Pre-Hellenic Greek myths for post-Hellenic children”. Children’s Literature in Education. 12 (4): 171–176. doi:10.1007/BF01142761. S2CID 161230196.

Christa Schäfer-Lichtenberger, The Goddess of Ekron and the Religious-Cultural Background of the Philistines, Vol. 50, No. 1/2 (2000)

David Ben-Shlomo, Philistine Cult and Religion According to Archaeological Evidence, January 2019Religions 10(2):74, DOI: 10.3390/rel10020074

Nilsson, Martin Persson (1 January 1950). The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion and its Survival in Greek Religion. Biblo & Tannen Publishers. ISBN 9780819602732 – via Google Books.

Alexiou, Stylianos (1969). Minoan Civilization. Translated by Ridley, Cressida (6th revised ed.). Heraklion, Greece.

Beekes, Robert S. P. (2009), Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Leiden and Boston: Brill

Marianna Ridderstad, Evidence of Minoan astronomy and calendrical practices, October 2009

Kerényi, Karl. 1976. Dionysus. Trans. Ralph Manheim, Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691029156, 978-0691029153

Monteiro Teixeira, Sílvia. 2014. Cultos e cultuantes no Sul do território actualmente português em época romana (sécs. I a. C. – III d. C.). Masters’ dissertation on Archaeology.. Lisboa: Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa.

Andonis Vasilakis, MINOAN CRETE: FROM MYTH TO HISTORY Paperback – January 1, 2001

Nilsson, “Fire-Festivals in Ancient Greece” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 43.2 1923

Carl A.P. Ruck and Danny Staples, The World of Classical Myth [Carolina Academic Press], 1994

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can we just let the Greeks have their gods? Why are people so obsessed with origins proving The Theoi Aren't Actually Greek™. I don't see anyone saying "well Hindu deities aren't actually Hindu, they're not from India! They're from the Proto-Indo-Europeans so aCkTUalY they're Eurasian Gods not from the Indian Subcontinent." Seems Hellenic Polytheist/Pagan spaces are hellbent on allowing Greeks to only claim deities whose origin is in the Mycenaean Pantheon. Otherwise they aren't actually Greek they're Minoan, Hittite, Phoenician, Egyptian, general ""ANE"", Etruscan (I guess), etc— then again even the Mycenaeans are robbed of autonomy because thats just a PIE pantheon like the Hittites. It's ridiculous.

Tracing the origin of deities is pretty awesome, but when you deny a culture its deities just because you can trace their worship back in history you're plainly being disrespectful. For example, Ašratu is a chief deity of the Amorite tribe, which came to rule Babylon. Thus their Goddess became apart of the "Babylonian Pantheon" as the Daughter in Law of An. Athirat an important Ugaritic (Canaanite) deity undoubtedly shares her origin with this Amorite deity, and became a principal Goddess in the "Ugaritic/ Canaanite Pantheon". Does that mean Ašratu isn't actually Babylonian and therefore (pretending they still existed) Babylonians can't lay claim to her as part of their heritage, culture, and pantheon? Or that Athirat isn't actually Canaanite therefore (if they still existed) Canaanites can't lay claim to her as part of their heritage, culture, and pantheon? No. That makes no fucking sense— Ašratu is Babylonian & Athirat is Canaanite even if the deities have their "origins" with the semi-nomadic Amorite culture.

Since Mesopotamian Ašratu was understood to be an Amorite deity, a connection between Ašratu’s and Athirat’s origins appears to be virtually certain. Being transferred to a different culture would have led to some adaptation of the Goddess to her new culture. This should stand as a caution not to apply specific details of Ašratu’s characteristics developed in Mesopotamia to Athirat simply because the earliest records attest to the former.” [X]

The same principles goes for the Greek Gods, just because a Theos' origin, for example Zeus, can be traced back to an earlier culture—*Dyḗus from the PIE people of the Pontic-Caspian Steppe—doesn't make Zeus any less of a GREEK deity.

This "they aren't Greek" trend is strongest with Aphrodite— whose worship probably "began" somewhere in the Ancient Near East primarily Cyprus or Phoenicia. The trend is also present and increasing with Apollo who has multiple different possible "origins."

If you're so obsessed with determining that none of the Greek Gods are actually Greek pick a different tradition to worship them in. Stop using "Hellenic" and say you're a PIE polytheist or Phoenician Polytheist or whatever tradition the """original version"""" of the Theos you are worshipping comes from. If you want to be a Hellenic Polytheist don't try and negate the Theoi's Greekness. Its bafflingly disrespectful especially since Greeks still exist and this is still their heritage.

No this isn't a "folkish" post its a salty post. And it is not directed at any one person but a phenomenon that pops up and seems to be increasing and I'm annoyed with it.

-not audio proof read-

[Edit, no I'm not talking about people who use 'Greek names' in Greco-Roman, Greco-Egyptian or any other syncretic traditions. I'm specifically talking about Hellenic Polytheist/Pagans who are obsessed with the Greek Gods being non-Greek because "origins"]

112 notes

·

View notes