#mikhail romm

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Triumph Over Violence (Mikhail Romm, 1965).

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nine Days of One Year (1962) dir. Mikhail Romm

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Director Sergei Eisenstein (lower) and his colleague and fellow film director Mikhail Romm (upper) dressed in drag to play Queen Elizabeth I in what would go on to be the incomplete and destroyed third act of the film “Ivan the Terrible” (1944-1946).

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yuri Pimenov, Pyshka (Boule de Suif), 1935

Scanned from the book "The Soviet Arts Poster, 1917-1987", Penguin Books.

Feature film adapted from Maupassant. Director Mikhail Romm, Moskinokombinat

Moskow, Reklamfilm - Kinofotoizdat. Colour litograph. 122 X 83

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Zone of Interest: The Banal Dreams of Nazi Settler Colonialism”

In Jonathan Glazer's Oscar-Winning Movie, You Do Not See Auschwitz the Camp; You See Auschwitz the Colony. Neither Exists Without the Other

— Hazem Fahmy | 11 March 2024 | Middle East Eye

English Director Jonathan Glazer Poses with the Oscar for Best International Feature Film for "The Zone of Interest" during the 96th Annual Academy Awards on 10 March, 2024 (AFP)

In the 1965 Soviet Film Ordinary Fascism, Also Known as Triumph Over Violence, director Mikhail Romm’s voiceover implores the viewer to pay attention to the petit-bourgeois quality of fascism in general, and Nazism in particular.

Over archival footage of German small-business owners leaving their stores in uniform and hopping onto bicycles, he remarks, almost comically: "Here is a butcher, and there goes a baker." This brief scene succinctly captures Hannah Arendt’s (by now highly cliched) notion of the "banality of evil", a phrase she coined while covering the trial of Adolf Eichmann, known as the "architect of the Holocaust".

But Arendt’s own refusal to interrogate the inherently colonial nature of European fascism, a refusal inseparable from her own racism and western chauvinism, has blunted the sharpness of that term’s capacity for critical insight. Yes, the Holocaust was engineered by middle managers, but to what end? What did they get out of the horrific affair, besides satiating their sadism?

A simple answer is Jonathan Glazer’s Academy Award-winning film,The Zone of Interest: land - more specifically, enough land to replicate the expansionism of American manifest destiny, to recreate the German Aryan into the fascist ideal of the Ubermensch.

Over the weekend, the film won the Oscar's best international film award. In his acceptance speech, Glazer told the audience: "Right now we stand here as men who refute their Jewishness and the Holocaust being hijacked by an occupation which has led to conflict for so many innocent people, whether the victims of October 7 in Israel or the ongoing attack in Gaza."

The story follows the mundane domestic lives of Rudolf Hoss (Christian Friedel), the longest-serving commandant of the Auschwitz concentration camp, and his wife and children, as they go about their days in their idyllic house adjoining the camp grounds.

As the primary subject is the Holocaust, the film has been widely noted for its refusal to visually depict any of the atrocities that occurred within the camp, though the audience frequently hears gunshots and screams from over the wall. This bold narrative and political choice has been consistently misread in mainstream film criticism as a simple affirmation of Arendt’s limited perspective on the "banality of evil".

It is far too simplistic to describe the film as a truncated biopic of its subject, nor is it accurate to reduce it to a formal experiment; a film about the Holocaust in which you do not see the Holocaust. In other words, The Zone of Interest is not simply a film about the Nazi official as a middle manager, but is much more importantly a film about the Nazi official as a settler.

Cartoon Villains

Since 1939, mainstream western education, media, and discourse about World War II and the Holocaust have strived to depict Nazism as a catatonic movement of unbridled hate, rather than a settler-colonial one in continuum with those of other western powers.

Nazis tend to be portrayed as larger-than-life cartoon villains, rather than quite ordinary monsters, easily comparable to their colonial brethren in the Belgian Congo, French Algeria or British India, among countless other places around the world that have had the misfortune of experiencing western occupation and colonialism.

youtube

Writers and scholars from across the Third World have, of course, long questioned this narrative. One of the most notable and succinct critiques was levied by Aime Cesaire in his Discourse on Colonialism.

But such perspectives have been uncommon within the US. With the exception of Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, which has frequently been criticised for oversimplifying the primary terms of its investigation, writing on the intimate connections between western, and very specifically American, colonialism and Nazism is often marginalised. Scholars such as Carroll P Kakel and Edward B Westermann are few and far between.

The beauty of these scenes begs the (rhetorical) question: what is the difference between Hoss's family and that of any other frontiersman?

This connection is laid bare in The Zone of Interest, both visually and politically.

The amount of screen time dedicated to the lush vistas of the Nazi-occupied Polish countryside, in which Hoss and his family hike, swim and play, evokes the frontier romanticism of classic western films such as The Naked Spur, Shane and Johnny Guitar.

Being Hollywood productions, these stories, of course, implore the viewer to identify with the settlers’ yearning for the vast landscapes they seek to conquer and rid of their indigenous inhabitants.

In The Zone of Interest, the gaze is identical, but it is now one of a Nazi as opposed to that of a noble American pioneer. The beauty of these scenes begs the (rhetorical) question: what is the difference between Hoss’s family and that of any other frontiersman?

Pivotal Scene

Glazer’s identification of Poland as a frontier for Nazi German expansion is one shared unambiguously by his characters. In a pivotal scene, Hoss and his wife Hedwig (Sandra Huller) argue as to whether they should leave Auschwitz. He has been reassigned elsewhere by his higher-ups and his instinct, as that of any family man, is to take his wife and children with him.

But Hedwig refuses: “Your work is in Oranienburg now. Mine is raising our children.” When he insists, she delivers the final blow: “This is our home. We’re living how we dreamed we would since we were 17 - beyond how we dreamed. Out of the city finally. Everything we want, on our doorstep. And our children strong and healthy and happy. Everything the Fuhrer said about how we should live is exactly how we do. Drive east, Lebensraum. Here it is.”

Hedwig’s impassioned plea emphasises what the vast majority of western media narratives seek to suppress: that genocidal fascist projects are always about reproduction as much as they are about destruction. This is why Lebensraum, German for "living space", is so seldomly discussed in mainstream depictions of the Holocaust.

The Nazis’ ideology of eastward settler expansion did not simply echo American manifest destiny, but considered it a blueprint. This is why the robotically repeated line that the film is about not depicting, or “looking away” from Auschwitz is patently false. You do not see Auschwitz the camp. You see Auschwitz the colony. Neither exists without the other.

Ironically, and despite being the only filmmaker at the 96th Academy Awards to explicitly acknowledge the situation, Glazer himself apparently failed to see the resonance of his own work to the ongoing Israeli genocide in Gaza. In multiple interviews, he has responded meekly when asked about Israel’s mass slaughter and starvation of Palestinians since 7 October, with a shallow lamentation for “both sides”. He repeated this liberal sentiment during his acceptance speech for Best Foreign Language Film, ignoring how the Hoss family has been reborn time and time again in Sderot and Ashkelon and all the other settlements of the so-called Gaza envelope.

Anyone uncomfortable with such comparisons needs only to listen to the words of Israeli leaders speaking of Auschwitz as their end goal for Gaza. I wish Glazer had done so, rather than fall into the tired old trap his own work so brilliantly escapes.

When it comes to colonialism, what most urgently demands our attention is not the banality of evil, but the evil of banality.

#Youtube#Middle East Eye 👁️#The Zone of Interest#The Banal Dreams#Nazi Settler Colonialism#Jonathan Glazer#Winner of Oscar for Best International Feature Film#English Director#96th Annual Academy Awards#Hazem Fahmy

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pyshka (1934) Mikhail Romm

Pyshka (1934)

#Pyshka#Boule de Suif#Galina Sergeyeva#Sofya Levitina#Nina Sukhotskaya#Пышка#silent film#soviet cinema#1934#1930s#mikhail romm

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Triumph Over Violence (Fascismo de Todos os Dias/Обыкновенный фашизм) Mikhail Romm 1965 • 2h10 • Documentário

O documentário utiliza material documental para destacar o horror do fascismo na Europa e reforçar que tais eventos não devem se repetir em nenhum lugar do mundo

0 notes

Text

Triumph Over Violence

1965 ‘Обыкновенный фашизм’ Directed by Mikhail Romm

0 notes

Photo

*

*

#trinadtsat#the thirteen#mikhail romm#1936#the ghost that never returns#abram room#alexander room#1929#materials#flyweight#michel focault#surveiller et punir#naissance de la prison#fritz lang#die frau im mond#spione#mabuse#dune#david lynch#woman in the dunes#berlin alexanderplatz#der verlorene sohn#rudolf arnheim#film als kunst#das politische und die kunst#war and peace#ilm#13

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Don't get used to me, don't get used to me, I'm a habit that's like a chain, And with a look of joy in your eyes And every day you look at me with a new look. What new clouds in the sky, And a new sunshine in the morning! Don't get used to me, don't get used to me, Don't give me to someone… / Mikhail Romm

Не привыкай ко мне, не привыкай, Привычкой каждый словно цепью скован, И взглядом радостным меня встречай, И каждый день твой взгляд пусть будет новым.

Какие новые на небе облака, И солнце новое нам дарит утро! Не привыкай ко мне, не привыкай, Не отдавай меня кому-то…

/ Михаил Ромм

187 notes

·

View notes

Text

#innokenty smoktunovsky#иннокентий смоктуновский#mikhail romm#михаил ромм#9 дней одного года#советское кино#soviet movie

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nine Days of One Year (1962) dir. Mikhail Romm

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

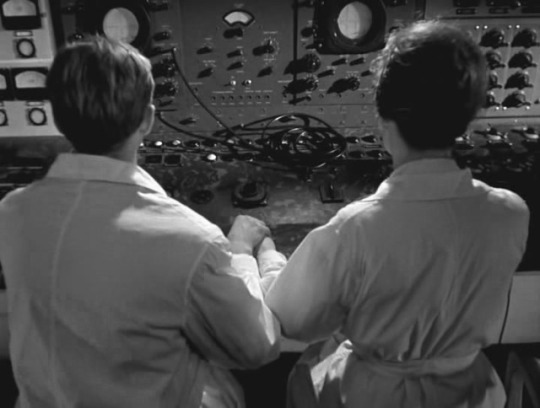

Девять Дней Одного Года/ Nine Days in One Year

Soviet Union, 1962

And why is that necessary for the humankind? Your humankind has enough of everything. The humankind reached such level of perfection, it can destroy all life on Earth in 20 minutes.

Science learned about chemistry - Germans created a poison gas. An internal combustion engine was invented - Brits built a tank. A chain reaction was discovered - Americans bombed Hiroshima. Doesn’t that make you wonder?

Do you seriously believe that people have become smarter in the last 30 000 years? Not at all. Our brain hasn’t grown and we have the same amount of grey matter as people back then. The person who invented a wheel was as much of a genius as Einstein. And the one who first learned to carve fire was more talented than the one who came up with quantum mechanics. Look at the statues of Akhenaten. He lived 4000 years ago. Look at Nefertiti. Such refined, intelligent, inspired features… And look around you now. Neanderthals.

But a pharaon could destroy 5000 or 10000 people. It’s nothing by modern standards. Genghis Khan couldn’t even imagine death camps and gas chambers. He could never think about fertilizing fields with ashes of burned bodies, filling mattresses with women’s hair, or making lampshades out of human skin.

#Soviet cinema#Russian cinema#USSR#Soviet Union#Russia#Soviet#Девять Дней Одного Года#Nine Days in One Year#1960's#1962#Aleksey Batalov#Innokenty Smoktunovsky#Tatyana Lavrova#Mikhail Romm#anti-war#nuclear#mine

42 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nine Days of One Year

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aleksey Batalov in Nine Days of One Year (Mikhail Romm, 1962)

Cast: Aleksey Batalov, Tatyana Lavrova, Innokentiy Smoktunovskiy, Nikolai Plotnikov, Zinoviy Gerdt. Screenplay: Daniil Khrabovitsky, Mikhail Romm. Cinematography: German Lavrov. Production design : Georgi Kolganov. Film editing : Yeva Ladyzhenskaya. Music: Dzhon Ter-Tatevosyan.

The Soviet film Nine Days of One Year, about nuclear physicists, appeared in 1962, which makes for an interesting counterpoint to the major news event of that year, the nuclear standoff known as the Cuban missile crisis. But for all its geopolitical significance, Mikhail Romm's film is a love story, a blend of the eternal triangle and a conflict between marriage and career. Dmitri Gusov, known as Mitya (Aleksey Batalov), is a dedicated scientist who in the first of the film's nine days -- they aren't consecutive but spread out over the year -- receives a dose of radiation while overseeing an experiment conducted by his mentor, Prof. Sintsov (Nikolai Plotnikov). The professor gets a lethal dose, but Mitya is told that he's safe as long as he doesn't get exposed to another large burst of radiation. Mitya is in love with a fellow physicist, Lyolya (Tatyana Lavrova), who is also involved with Mitya's friend Ilya (Innokentiy Smoktunovskiy), a theoretical physicist. Ilya and Lyolya are on the verge of telling Mitya that they're going to get married, but the accident propels Lyolya into marrying Mitya instead. It's a rocky marriage, to be sure, with Lyolya worrying that Mitya is putting himself in harm's way while at the same time fretting that she's not doing enough to overcome his coldness and obsession with work. Through all this there's much talk, especially between Ilya and Mitya, about the morality of nuclear science, the nature of humanity, and even about whether they're doing enough to advance the future of communism. Fortunately, the ideological talk is kept to a minimum. Romm directs all of this with great style: long takes shot at low angles and a camera that moves restlessly between the characters as they talk. Somehow the film never falls into the obvious clichés, maybe because Batalov, Lavrova, and Smoktunovskiy bring their characters to life.

0 notes

Photo

Illustrations in the book ‘Le Cinema Sovietique Par Ceux Qui L’ont Fait’ - 3

#le cinema sovietique par ceux qui l’ont fait#alexandre dovjenko#evgueny gabrilovitch#koukrinixy#mikhail romm

3 notes

·

View notes