#michael stein

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

candid shot of me adding the first i love you (orchestral) to the byler proof meme collage

#stranger things#80s#the duffer brothers#will byers#mike wheeler#byler#miwi#memes#stranger things day#st5#byler proof#st memes#finn wolfhard#score#kyle dixon#michael stein

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

GOD DAMN! I wish I could go to this!!!!!

#trent reznor#atticus ross#trent reznor and atticus ross#nine inch nails#GOBLIN#john carpenter#Ben Salisbury#geoff barrow#danny elfman#kyle dixon#Michael stein#mark mothersbaugh#questlove#music vibes#music visualization#music vlog#music venue#music blog#captainpirateface#bipolardepression#chemicalimbalance#wtf#captainpiratefacelovesyou#sighthsandsoundsofinstagram#sights and sounds of tumblr#future ruins

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stranger Things (season 3)

Favorite poster

#stranger things#stranger things 3#kyle dixon#michael stein#dustin henderson#lucas sinclair#mike wheeler#will byers#noah schnapp#millie bobby brown#eleven hopper#jane hopper#jane ives#eleven stranger things#stranger things eleven#eleven#11#011#sadie sink#max mayfield

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

November 8 2025 | Los Angeles,CA

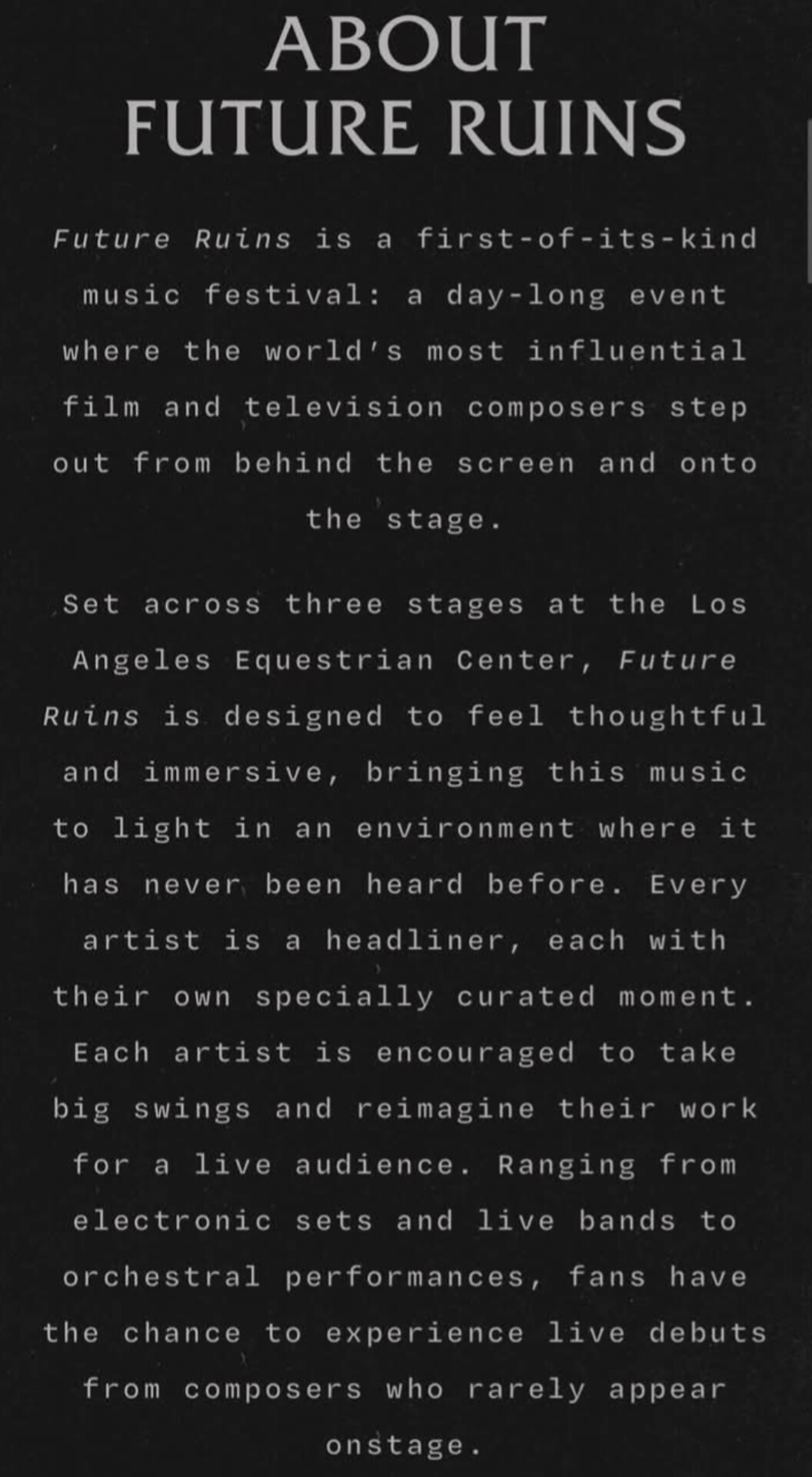

F UTURE R UINS is a first-of-its-kind music festival: a day-long event where the world’s most influential film and television composers step out from behind the screen and onto the stage.

via Future Ruins | Instagram

#future ruins#trent reznor#atticus ross#john carpenter#danny elfman#trent reznor and atticus ross#goblin#kyle dixon#michael stein#questlove#music festival#nine inch nails#nin#mark mothersbaugh#film composer#cinephile#film scores

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't know what instrument they used, but there's a point in Vecna's theme ("There are some things worse than ghosts") that sounds a lot like the Negaverse (Queen Beryl) theme from the DiC soundtrack for Sailor Moon.

It's easy to forget that the original dub for Sailor Moon was produced in the early '90s, when people had yet to shake the '80s corpse off their shoulders.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

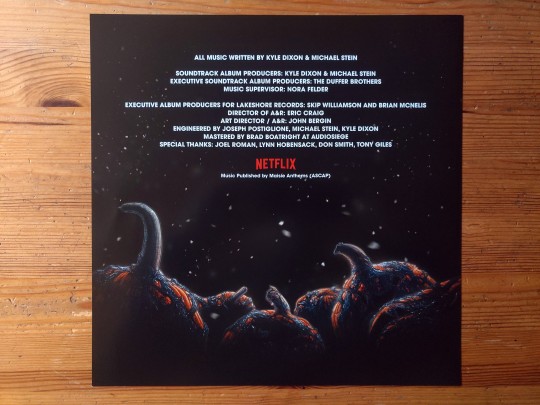

Kyle Dixon & Michael Stein - Stranger Things 2 | Invada Records | 2018 | Clear with Blue & White Splatter

#kyle dixon#michael stein#stranger things 2#invada records#vinyl#colored vinyl#lp#music#records#record collection#soundtrack#stranger things#netflix

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

Michael Stein - Grew up with Dyslexia and ADHD and Found Success as a Long Shot

Michael Stein is an entrepreneur, actor, writer, director, producer, stand-up comedian, and personal development expert. Michael is the founder and CEO of Abadak Inc. A company that he started with zero money and has since made 100+ million dollars. Started his entrepreneurial career when he was 19 years, becoming the #1 young nightclub promoter in Los Angeles. Michael has acted and worked with…

0 notes

Text

walkin in hawkins...

0 notes

Text

Stranger Things | Title Sequence [HD] | Netflix

youtube

Spooktober TV show song 🎵 of the day: Stranger Things Theme by Kyle Dixon & Michael Stein (2016) #strangerthings #KEVINDIXON #MichaelStein #2010s #spooktober #halloween #october

0 notes

Text

Album name: Stranger Things: Season 1 - OST

Song name: Tendril

My favorite soundtracks.

#stranger things#stranger things 1#ost#kyle dixon#michael stein#dustin henderson#lucas sinclair#mike wheeler

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Lager Darkly — In Search of Culmbacher, One of America’s Great, Extinct Beers

— Words By Michael Stein | Illustrations By Colette Holston | Published: March 17, 2021

A recipe for Culmbacher lives on in archival perpetuity in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. Introduced to American drinkers in the second half of the 19th century, the Lager style was born in Kulmbach, Germany before it found a receptive audience overseas. As its popularity increased in the ensuing decades, scores of breweries started making it, from New York to California.

According to source material, the original, Old World Kulmbacher was a dark beer. It had a pronounced malt flavor and a sweetish taste. For American brewers, it had Bavarian characteristics, in that it was brewed along the lines of a Bavarian Lager, with a strong starting gravity. Perhaps the greatest variation between the German original and the American adaptation is that U.S.-made Culmbacher was sometimes brewed to be a near beer—that is, high in extract and low in alcohol.

Borrowing a page from Germany, American brewers sold copious quantities of kegs to the beer-drinking public in biergartens adjacent to their breweries, or elsewhere across town. In Washington, D.C., where the historic Washington Brewery Company once produced large volumes of the style, numerous biergartens were run by German immigrants. Another was run by a Frenchman who, every July 14, staged a reenactment of the storming of the Bastille. And down by the docks, where there is still a seafood market today, customers would crush foaming seidels as they cracked hard-shelled Chesapeake crabs.

But for all the ways that Culmbacher reflected the push-and-pull of German-American beer culture and identity, the style was not to last. Ultimately, the nativism and xenophobic sentiment that sprung up around World War I meant that German beer traditions began to fall out of favor. Later, the hope that Culmbacher would weather Prohibition was a fanciful one, as most breweries that produced it ultimately closed. Today there is little trace of the style, beyond the recipe for “Kulmbacher” (it was spelled with a “C” in some places, and in others with a “K”) that remains in the National Museum of American History’s archives, on a single, typewritten page.

Still, discovering this trace—knowing that a shadow of this beer existed, even in obscurity—convinced me that Culmbacher could, and deserved to be, revived. When I read the recipe for the extinct near beer, I knew then, there in the archives in 2016, that I had to convince a brewer to help me recreate it.

Two Countries, Two Recipes

As early as 1831, Kulmbach began exporting beer to Saxony and other parts of Germany. Around 1863 and 1864, Kulmbach was exporting as much as 96,000 hectoliters of beer—or over 81,000 barrels. In 1868, the U.S. and Australia were listed as export markets. By 1896, Kulmbach was producing 600,000 hectoliters of Kulmbacher, or over half a million BBLs.

Beer historian Ron Pattinson has, in his collection, an 1879 Kulmbacher Export recipe made with two German malts, Munich and Carafa. The German recipe yielded a beer at 6.2% alcohol by volume, which was typical: In the 1880s, analysis of the Bavarian export showed it ranged from 5.2% to 6.6% ABV. (Once it arrived in the U.S., the style diminished in strength in many cases—Milwaukee’s Blatz Brewing Company, for instance, brewed a Culmbacher at 4.75% ABV.)

There are still many mysteries surrounding Kulmbach’s eponymous style, including its spelling. To begin: Is “Culmbacher” just an anglicized version of its name?

“I would have said ‘Culmbacher’ was an anglicized version, except I’ve seen a Heineken version with that spelling,” Pattinson says. “Which leaves me wondering where the hell it came from.”

“Beers were named after their hometown but they came to be brands and styles brewed elsewhere as well,” says Mark Dredge, author of A Brief History of Lager. “I don’t know why the ‘K’ or the ‘C’ in the spelling. Perhaps it was due to not wanting trademark infringements, as there were plenty at the end of the 1800s.” As an example, he notes the seemingly small but important differences between “Pils” and “Pilsener”: “Heineken was one of the first to add the extra ‘e’ in Pilsner, so maybe that’s why they had a ‘Culmbacher,’” he says. The difference between Dutch “Bok” and German “Bock” is another form of this discrepancy.

Further complicating our understanding of Kulmbacher is the fact that it could be brewed as a very low-alcohol near beer. In the 1920s, Pabst’s Kulmbacher contained less than .5% ABV. As for the recipe I found in the Smithsonian’s archives, which was donated by Walter Voigt—the son of German immigrants who was born in 1906, and who was a member of the Master Brewers Association of the Americas—the piece of paper reads in all capitals: “Malt to be used for various types of near beer.”

Voigt’s Kulmbacher recipe contains four malts: high-dried, pale, caramel, and black. Missing from the recipe are hops, corn, and yeast. As Pattinson puts it, the recipe “looks to have been adapted to U.S. malts. You wouldn’t see high-dried in Germany. The equivalent would be Munich malt.” He goes on to speculate that it “could also be that they had added different malts to give the near beer more body. Body might well be the reason for skipping the adjuncts, too.”

Dark Lager's Bright Rise

In Bavaria in 1863, master glassmaker Simon Hering began brewing on a large scale. His brewery, Export-Bier-Brauerei Simon Hering, started exporting beer to the United States in 1864, during the Civil War.

Hering was the first German brewer I could find who exported Kulmbacher to the U.S. However, there seemed to be earlier awareness of the style: In a German-language newspaper in the Library of Congress, an 1861 article published in Minnesota states that Benzberg’s Dampfbrauerei made Lager in St. Paul, and that it was as good as Culmbacher or Nürnberger.

“Eventually, as the years wore on, the U.S. began to import less Lager in favor of brewing it at home. That change happened gradually, as German-American brewers began to produce their own versions of traditional styles. ”

It was becoming common in the mid 19th century for exported German Lager to be bottled and sold stateside. Such beer wouldn’t have made the trip to America without demand. The largest contingent of immigrants in the Union army were German soldiers. Kulmbacher appealed to those immigrants as a product they could buy from the old country, in the new one.

Eventually, as the years wore on, the U.S. began to import less Lager in favor of brewing it at home. That change happened gradually, as German-American brewers began to produce their own versions of traditional styles.

In 1875, a saloon owner in Wheeling, West Virginia began his Lager beer-bottling business, and would deliver pints and quarts throughout the city. The same dealer advertised Kulmbacher in 1880. In 1889, a Pittsburgh brewer manufactured Culmbacher and Vienna Lagers for city use. And in 1889, the Washington Brewery Company sold more Lager in D.C. than all breweries currently operating in the District today: 36,000 BBLs of beer in 1889, versus a combined 35,857 BBLs from 12 breweries in 2019. By 1900, the Washington Brewery Company boasted that its Culmbacher equaled the finest imported beer. This would become a common claim for American brewers who wished to convince the beer-buying public that their product was just as good as, if not better than, German imports.

As domestic Lager proliferated at the turn of the 20th century, American breweries made dark beers from coast to coast. In its heyday, Culmbacher was brewed everywhere from New York City and Washington, D.C. to Milwaukee and San Jose. By 1909, Kulmbacher and Pilsner were even available at the Criterion Hotel in Honolulu, Hawaii. The beer was likely the imported article, though Honolulu did have its own brewery in 1909, making Pale Lager in the German style.

Today, former Culmbacher producers like Pabst and Blatz are better known than their historical competition. But in addition to businesses like the Washington Brewery Company, little-known breweries like the Fredericksburg Brewery in San Jose and the Lion Brewery in New York City also manufactured Culmbacher.

For Relaxing Times

In the early days of Culmbacher’s spread, the style was advertised mostly on draft. If you wanted it in Los Angeles in 1884, it would cost you five cents a glass for the Kulmbacher Lager brewed by the Fredericksburg Brewery, which could be quaffed at both Jake Phillipi’s Buena Vista or the Grand Central Hotel saloon.

The later transition from the saloon to the biergarten likely allowed brewers to sell more beer. In many cases, it benefited drinkers, too. At the Washington Brewery Company, for instance, the brewery’s biergarten was right next to the brewery. The Culmbacher manufactured, cellared, and eventually sold on draft there never traveled more than a hundred yards.

The concept of drinking for pleasure, rather than intoxication, is commonly credited to the influence of German beer culture. And if it was American to have drinking in saloons limited to men, it was German to have women drinking in biergartens. In 1885 in D.C., one saloon—Kozel’s Saloon on 14th Street—expanded to the back of a lot and took over a second floor. The second floor became a special room for women patrons.

Even if American societal norms frowned on women drinking Culmbacher in public, a case of beer for home use could be delivered in unmarked wagons, lest your neighbor judge. Washington Brewery Company encouraged consumers to “keep your ice box well supplied” with Culmbacher, which was also sold in 24-pint or 12-quart bottles. By the end of the 19th century, the brewery was marketing directly to women: Its beer was pure. It was as good as the imported article. It had double strength. And it was the best of all tonics. In fact, it was unsurpassed as a tonic. Alongside claims that it was calming to a woman’s nerves and stimulating to her appetite, depictions of women drinkers were featured in its ads.

“Double strength” here implies an alcoholic beer, at a time when we know some Lagers were 3% ABV and that the export beer coming out of Kulmbach was 6% ABV. While the Washington Brewery Company’s Culmbacher might not have had the same recipe as the Kulmbacher in the National Museum of American History’s archives, there is no doubt it was advertised to the public as “heavy in body.”

According to Truth, a London periodical in 1889, “American lager beer breweries possess great advantages over others, as thin light beer is the national drink of the United States, and suitable to the climate.” While thin light beer may have been the national drink, it had competition in the rich, potent Dark Lager sold across the country.

Several breweries that made Culmbacher, in addition to other Lager styles, were successful enough that they made attractive entities for acquisition. In 1889, the owner of the Washington Brewery Company was paid $400,000 for his brewery—over $11 million in today’s money. Similarly, in 1891, Valentin Blatz Brewing Company in Milwaukee sold for $3 million to a London investment group, or for between $80 and $90 million today. And while there’s no proof that these breweries were bought directly because of their Culmbacher production, they were able to build their reputations—and their fortunes—off the back of such Lager styles.

By Prohibition, an irrevocable transition had occurred from Kulmbacher as an import, bottled stateside, to Culmbacher, a domestically brewed beer. In the course of five decades, the recipe had also changed: The beer had gone from a strong Bavarian beer brewed with German malt, to, in some cases, a non-alcoholic near beer brewed with American-grown barley.

While the Washington Brewery Company went out of business in 1917, it is noteworthy that Blatz brewed the style even after Prohibition’s repeal. Blatz’s Kulmbacher won silver at the first-ever judged Great American Beer Festival in 1987, in the American Lagers category. At the time, the brewery was owned by G. Heileman Brewing Co. of La Crosse, Wisconsin.

Evil, Traitors, Spirs

Lagers remain America’s most popular beers today. But there was a point in time when temperance advocates and anti-immigration backers viewed them as too German.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Germans still made up the largest ethnic group among immigrants to the United States, as they had done throughout the 19th century. Between 1820 and World War I, nearly 6 million Germans arrived in the United States.

“‘They [Germans] changed America, notably its own beer-drinking culture, and America changed them right back. Naturally that led to some friction ranging from friendly to violent. And for all their ‘palatability’ to white, Anglo-American sensibilities, they could never seem to fully shake nativist animus either. Anti-German xenophobia during World War I showed that.’” — Brian Alberts, Historian

“They [Germans] changed America, notably its own beer-drinking culture, and America changed them right back,” says historian Brian Alberts. “Naturally that led to some friction ranging from friendly to violent. And for all their ‘palatability’ to white, Anglo-American sensibilities, they could never seem to fully shake nativist animus either. Anti-German xenophobia during World War I showed that.”

Anti-German sentiments flared leading up to World War I. From 1850 to 1870, Germans largely gained acceptance from white Americans. But, Alberts says, Germans “were the ‘other’ in a predominately Anglo-American society because [they thought] their neighborhoods stunk of sausage and Limburger cheese, and they let the Lager beer pour every Sunday.”

According to Alberts, Sunday festivities, parades, and biergarten picnics “seemed sacrilegious to some.” These modern aspects of German-American beer culture were regularly celebrated, but the xenophobia associated with bringing your family to the biergarten was often glossed over.

During World War I, that xenophobia extended to food and drink. Sauerkraut was rebranded as “liberty cabbage,” and hamburgers became Salisbury steak. Symphonies were banned from performing Beethoven. Teaching German was struck from many curriculums and angry mobs attacked German-American citizens. Violence resulted in beatings, or even murder.

In 1917, the Trading With the Enemy Act legalized seizing citizens’ businesses and livelihoods. New York brewer George Ehret’s mansion and brewery were both seized. At the time, his Hell Gate Brewery was the biggest in New York City. His estate, property, and possessions, worth $40 million, were all taken.

I asked Maureen Ogle, historian and author of Ambitious Brew: The Story of American Beer, which had had a bigger impact on German-Americans’ lives—the state-sanctioned xenophobia or the daily harassments they experienced. “Probably the state-sanctioned attacks, because those, in effect, gave regular folks ‘permission’ to act violently towards German-Americans,” she says. “Certainly the news, national, that the AG [attorney general] had gone after brewers’ property affirmed a belief that German-Americans were evil, traitors, spies, etc. Never mind that they were American citizens.”

Even citizenship could not save German-Americans from having their property seized, being beaten, or in the case of at least one man, being hung. Robert Prager was a German immigrant who was lynched in Collinsville, Illinois in 1918. Prager had been a mine worker, but was denied membership in the United Mine Workers of America. The dispute ultimately led to his death at the hands of an angry mob of hundreds. The marauders made Prager kiss the American flag and sing patriotic songs before ultimately taking his life. There were no convictions in Prager’s murder, and the 12 men indicted walked away from the trial.

Of course, angry mobs have used terrorism, and lynching, for centuries in America, with Black people making up the vast majority of the victims. Multiple anti-lynching bills have passed the House and the Senate, but never at the same time. The Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, first introduced in 1918, passed the House of Representatives in 1922. And while the first anti-lynching bill was introduced in Congress in 1900, still to this day no bill has been passed by both houses and signed.

The Comeback of Culmbacher

It’s tricky to pinpoint why Culmbacher was lost to history. In the U.S., multiple factors led to its decline, while according to Pattinson, Kulmbacher isn’t even brewed in Kulmbach today. Other traditional German styles can be found in breweries in Kulmbach, he says, but “no one really brews a beer in what I would call the ‘Kulmbacher style’—something that’s 16 degrees Plato, virtually black, and loads and loads of hops in it.”

Perhaps that’s why, when I saw that typewritten recipe in the museum archive, I knew I had to at least attempt to bring it back. So I reached out to the master brewer who helped me take my first homebrew recipe commercial in 2012: Favio Garcia, the director of brewing operations at Dynasty Brewing Company in Ashburn, Virginia.

“‘Certainly the news, national, that the AG [attorney general] had gone after brewers’ property affirmed a belief that German-Americans were evil, traitors, spies, etc. Never mind that they were American citizens.’” — Maureen Ogle, Historian

Garcia first brewed a Kulmbacher in 2016, sticking entirely to the historical malt bill outlined in the Smithsonian’s archives. Its requirements were 11 lbs of high-dried malt, 33 lbs of pale malt, 3 lbs of caramel malt, and 1 lb of black malt. In 2016, this was translated to 11 lbs of Vienna malt, 33 lbs of pale malt, 3 lbs of Caramunich malt, and 1 lb of Carafa Special 3. We hopped it with the American Empire hop, which originated in Sweden but whose new stock was propagated on a farm on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

The resulting beer was historically accurate with its malt proportions, but it wasn’t dark, and it wasn’t the immaculate beer Garcia is renowned for. The 2-BBL batch had a bitterness that clashed with the black and caramel malts; the resulting beer came across as a dry Lager. It was not the full-bodied, sweetish, rich Bavarian beer described in the source material.

In 2020, Garcia returned to the recipe. In addition to a mild tweaking of the recipe from the archives, Garcia also came armed with more primary research conducted by Ron Pattinson. He employed a decoction mash with two steps, and used German and Czech hops instead of American.

Garcia also selected Virginia malt from Murphy & Rude Malting Company. In the mash tun, Pilsner and crystal malts mingled with Vienna malt, made from a 2-row variety of barley called Calypso. It was grown on the Brann & King Farms in Christiansburg, Virginia. Later, he added black malt to color the wort. In the end, Garcia used 660 lbs of Pilsner malt, 300 lbs of Vienna malt, 50 pounds of crystal 40, and 50 pounds of Carafa Special 3.

Where the first batch of Garcia’s Kulmbacher was pale brown, the new iteration looked like a Stout. There was an unmistakable German and Czech hop character to the beer, and it had a perceived sweetness on the first sip, followed by a subtle bitterness and a pleasing dryness on the finish. It was a wonderful expression of fresh malt, and featured a deep bready character that was somehow sweet, full, dry, and very digestible all at once. At 6.2% ABV, it was stronger than most of the Lagers Garcia brews.

The beer, Love Vigilantes, is named after the New Order song. It was a three-part collaboration beer with Dynasty; Dulles, Virginia’s Ocelot Brewing Company; and my beverage research firm, Lost Lagers. My greater goal with the beer is to bring back something stuck in beer history that deserves a place in the beer world today.

My bias is shaped by my father, who came to New York City as a refugee from war-torn Prague. When he came, he only had his mother. His father, a Jewish concentration-camp survivor, couldn’t get a visa. So Petr Stein became Peter Stein, and a boy who lived in a room the size of a closet with his mother wound up becoming a doctor of sociology, a published author, and the director of a graduate sociology program featuring Holocaust and genocide studies. My grandfather experienced the loss of his family in death camps while he survived his interment in the Theresienstadt concentration camp. But he had his life, and his wife and son had visas, and eventually they were reunited in New York.

In spaces where we have the ability to ask hard questions, be it about beer or what we believe to be right or wrong in terms of immigration, we, humans, have endless opportunities to improve ourselves.

“Kulmbacher” on paper in the archives, as it sat for the better part of a century, was made better with its second modern brewing. And its story cannot be told without acknowledging its origins, and the people who made and shaped the style as it evolved. I hope we can all find our own time-lost Kulmbacher—that we can discover and revive vestiges from the past that still speak to, and make sense of, the world today.

— Michael Stein is President of Lost Lagers, Washington, DC’s premier beverage research firm. His historic beers have been served at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and the Polish Ambassador’s residence. Senior Staff Writer at DCBeer, his work appears in Washington City Paper, Brewery History Journal, and CIDERCRAFT Magazine.

— Source Material: Delving into the archives, digging up artifacts, and finding voices in the dark, this series illuminates old traditions that we're still part of today (whether we know it or not). Beer's past shapes its present and future. Follow along as these historians and writers take us back to the source.

— GoodBeerHunting.Com | September 10, 2023

#Source Material#Creating Baverage Brands#Feel Good#Michael Stein#Good | Beer | Hunting#Colette Holston#Culmbacher#America’s Great | Extinct Beers#Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History#Washington D.C.#New York—California#Old World Kulmbacher | Dark Beer 🍺#Bavarian Lager 🍺#Borrowed | Germany 🇩🇪 | American 🇺🇸#Washington Brewery Company#Biergartens#World War#National Museum of American History#Saxony#Beer Historian | Ron Pattinson#Milwaukee’s Blatz Brewing Company#Heineken#Mark Dredge#Pils | Pilsener#Pilsner#Dutch 🇳🇱 Bok | German 🇩🇪 Bock#Pabst’s Kulmbacher#Walter Voigt#Master Brewers Association#Malt

0 notes

Text

Today is a day of both love and affection, showing appreciation to those who gave us both protection, and guidance in a world that can be just as cruel and merciless-as it can be kind and warm--to the vulnerable. For not only those who are with us today, but the people who couldn't make the journey with us till now. For those who entered our lives later down the line, to give us what was either not given, or lost, and stepped up when no one else could, or would. We love you for being there for us, in the past, now, and forever more. Happy Father's Day!!

Crediting Artists for making this possible: ~@birdie-ghost ~@saltynsassy31 ~@notsodailycake ~@moonfang182-magic ~@galevonhjonkbringerofgoose

As for the owner of these delightful Father-Son pairs! Image 1: Growl and Michael by @soniccrazygal Navy and Freddy and Frank by @moonfang182-magic Archer and Tank by @carogdraws Found and Home by @theinsanefoxwriter D & T & Koal by @aboraccoons Rails and Foxy by @ghostthefox1997 Image 2: Bunny & Spring & Fred by @ghostthefox1997 Bunbun and Grizzly by @moonfang182-magic and @honey-bunnysaurus Kiwi and Freddy by @notsodailycake Estrella and Freddy by @aboraccoons Sunny & Puppet & Moon by @moonfang182-magic Rabid and Handler by @soniccrazygal

Image 3:

Wander and Henry Stein by @soniccrazygal Fizzy & Michael & Jeremy by @birdie-ghost Feathers and Angel by @soniccrazygal Jinx and Freddy by @moonfang182-magic Rift & Reset and Haunter by @galevonhjonkbringerofgoose Ed and Noah by @hexyz09

#fnaf gregory#gregaverse#fnaf#fnaf sb#fnaf security breach#five nights at freddy's#fnaf au#Father's Day#Henry Stein Bendy and the Ink Machine#Fnaf OC#Fnaf Michael#FNaF Jeremy#Fnaf SB Glamrock Freddy#Fnaf Foxy#Fnaf SB Sun#FnaF SB Moon#Fnaf SB Daycare Attendant

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

saw a post about making zines... so i decided to try my hand at it. and i'm actually so in love with this format!!

if anyone actually does want to print this out (i doubt it but it wouldn't be a zine otherwise heh) here you go! xDD

sorry it looks a bit trippy! i'd print it to see how it looks but i can't afford to waste the ink if i mess up TwT. but i had SO much fun making this!! if i ever go to a con i'll definitely make some fandom zines 🤭💖💖💖

#zine#hmm how to tag... a bunch of these fandoms are pretty inactive so guess ill tag those!#but ill just tag#mcspirk#six the musical#six the musical fanart#araleyn#total recall (1990)#(im a rarepair magnet ok!)#be more chill#be more chill fanart#meremine bmc#bmc#bmc musical#michael mell x christine canigula#frankie stein x abbey bominable#monster high#kingsman#roxy morton#ginger ale kingsman#roxy morton x ginger ale#(rare yuri has me in a chokehold obviously 🫡)#LMAO#melly plinius#(inhale) how do i tag them.... im sure this one is a shiny new tag#idv entomologist#idv entomologist x clerk#keimelly idv#identity v#dustys sketchbook chronicles

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

alice angel: hey bestie 🙏😔i am once again asking 🥺 for a favor🥺🥺 i NEED you 🥶🥶🥶to take this EMPTY toilet paper tube 🧻to thr 420th 💕floor and KILL 🔪🩸 three thicc 🥵gushing squelchers with it🤩👍and give me their organs 🥺🙏bestie boo please ✨and also you can’t die 😞👹👹i killed your dog btw😫

henry: i thought about killing you last cycle

#batim#bendy and the ink machine#alice angel#henry stein#batim chapter 3#batim shitpost#batim textpost#another michael original#this one was clawing screaming at the inside of my skull for three days begging me to post it#so i’m sorry

107 notes

·

View notes

Note

THERE'S GONNA BE A BENDY MOVIE

The divide between the Dad Friends™️ and Doug Houser continues to grow with this relevation

#answering asks#fnaf#five nights at freddy's#michael afton#mike schmidt#henry stein#bendy and the ink machine#bendy movie#dark deception#doug houser#willy's wonderland#the janitor#resident evil#ethan winters#i cant believe we got the bendy movie announcement before chapter 5 dark deception#laughing my ass off that the dad friends are all gonna have movies related to their franchise and doug still cant finish his story#doug's getting desperate#sorta excited to see where this movie will go given fnaf's success

363 notes

·

View notes