#maurizio nannucci

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Poésie Concrète, Texts by Paul Bernard, Gabriele Detterer, and Maurizio Nannucci, MAMCO, Genève, 2022 [Les presses du réel, Dijon]

Feat.: Ian Hamilton Finlay, Augusto and Haroldo de Campos, Dom Sylvester Houédard, John Furnival, Maurizio Nannucci, Franz Mon, Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt, Natalie Czech, Julien Blaine, Jean-François Bory, Pierre and Isle Garnier, Bob Cobbing and Richard Kostelanetz

#graphic design#art#poetry#concrete poetry#visual poetry#typewriting#catalogue#catalog#cover#paul bernard#gabriele detterer#maurizio nannucci#mamco#les presses du réel#2020s

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maurizio Nannucci | Decoding Different Directions, 1999. diameter 5.7 cm. cardboard box (6.3 x 6.7 x 6.7 cm), synthetic ball with integrated text and colour

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

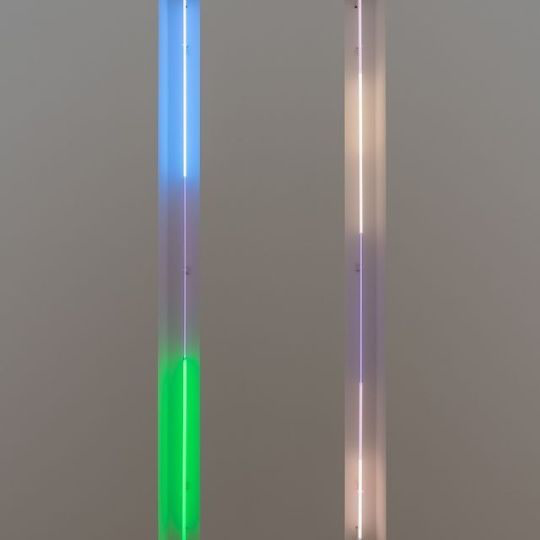

Maurizio Nannucci, Moving Between Different Opportunities and Open Singularities (Red), 2018

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maurizio Nannucci. 1969

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram

Maurizio Nannucci

.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

la fortuna economica della sperimentazione: marcel duchamp

« Je me souviens d’une anecdote racontée par Daniel Spoerri à propos de ses éditions MAT MOT. Un jour, à la fin des années 50, il téléphone à Duchamp et lui demande : « Vous avez encore des Rotoreliefs de votre éditions de 1935 ?- Oui, oui, j’en ai encore. – Combien en avez-vous fait ? – 100 – Et combien en reste t-il ? – 90… » Il n’en avait vendu que 10 ! » Maurizio Nannucci. Jeff Nimp:…

View On WordPress

#art#éditions#Daniel Spoerri#Duchamp#edizioni#Jeff Nimp#Marcel Duchamp#MAT MOT#Maurizio Nannucci#Rotoreliefs

0 notes

Text

Maurizio Nannucci. Nero, 1969.

1 note

·

View note

Text

261: Various Artists // Poesia Sonora

Poesia Sonora Various Artists 1975, CBS

Assembled in 1975 by Italian conceptual artist and sound poet Maurizio Nannuci, Poesia Sonora (Sound Poetry) was one of the first attempts to anthologize the then-predominantly European literary genre. Subtitled an “International anthology of phonetic research,” it emphasizes the experimental nature of these compositions. Sound poetry was on one hand the logical next step in the development of free verse (i.e. if a composition can be a poem without rhyme or meter, it can also be a poem without words), and on the other an outgrowth of currents in linguistics and semiotics that distinguished between language as a system of meaning and its arbitrary phonological characteristics. In other words, it freed writers to use language and the building blocks of language non-representationally, akin to music or abstract painting. Many early sound poets presented their works as conceptual experiments—to give but two examples, in his manifestos Kurt Schwitters, a key figure in early sound poetry thanks to his 1923 Ursonate (trans. Primeval Sonata), urged other artists to explore words and verbal sounds as entities independent of meaning, while Nannuci’s liner notes mention the Italian futurist Fortunato Depero, whose “‘onomalingua or abstract verbalization’ verbally reconstructed the noise of machines, trams, trains, cars, and natural forces including wind, thunder, and rain.”

youtube

Obviously, while these “experiments” wear pseudo-academic garb, this was a thoroughly poet-brained endeavor, and the reality of the genre was one of (predominantly) men flecked with spittle and profuse sweat honking and braying at vexed audiences. It was conceptual, but also an excuse to make strange noises. The terms of their experiments were not (and could not be) empirical, but the results could be as transfixing as the best avant-garde music of the 20th century, with the unchaining of the human voice giving performances a uniquely primal immediacy.

Sound poetry’s earliest texts date from the 1910s and ‘20s, but its real boom came with the wider availability of magnetic tape in the middle of the century. With the exception of the Swiss Arthur Pétronio, whose concept of “verbophonie” (a combination of abstract vocalizations and acoustic sounds) dates back to at least 1919, Poesia Sonora focuses on the generation of sound poets who came to prominence in the 1950s and ‘60s. The poems are presented almost without pause, giving each LP side a collage-like quality. The brilliant Englishman Bob Cobbing’s polyvocal mosaic “Hymn to the Sacred Mushroom” practically segues into Frenchman Henri Chopin’s “Dinamisme integral,” a percussive wave of minutely-chopped unidentifiable vocal sounds that conjures a sense of many dusty wings fluttering in an enclosed space, or Aphex Twin at his most minimal; Chopin’s piece gives way to the German Franz Mon’s “Articulation,” which utters individual consonant and vowel sounds in such a way that it gives the impression of an aphasic trying to recover their language.

Despite sound poetry’s mission to abstract and defamiliarize language, the international nature of the compilation does present challenges to the monoglot. Many of these poets still play with the meanings attached to language (for example by breaking down an emotionally- or politically-charged word into atomized nonsense), and that sort of resonance is lost when you’re just listening to a guy slowly spelling out words in Italian (?) (Nannuci’s “Spelling”). I’m therefore most intrigued by the pieces that are more purely sonic, like Chopin’s piece or François Dufrêne’s “Crirythme,” an athletic spectacle that finds the artist tormenting his throat into sounds resembling a coffee percolator, a whistling kettle, and the soup-slurping of a demented dinner guest. I’ve also long had a special fondness for British-Canadian Brion Gysin’s “I Am,” a piece I’ve heard performed as a lengthy koan-like meditation (by contemporary sound poet Jaap Blonk) and here as an echoing hell of tape manipulations.

youtube

I am far from a true connoisseur of sound poetry (and in fact, can almost hear Ottawa poet, publisher, micropress archivist, and good-natured curmudgeon jwcurry hollering at me for mistakes in this right up), but for those with a taste for the field and an interest in its history, Poesia Sonora (and the useful circa-1975 discography offered in its liner notes) is a good grab.

261/365

#brion gysin#henri chopin#bob cobbing#franz mon#arthur petronio#arrigo lora-totino#bernard heidsieck#sten hanson#maurizio nannucci#francois dufrene#paul de vree#sound poetry#spoken word poetry#poetry#vinyl record

0 notes

Photo

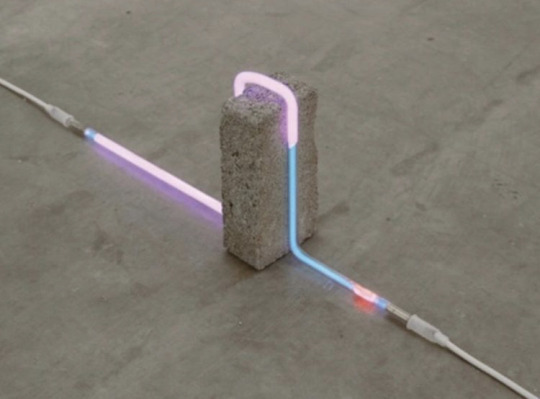

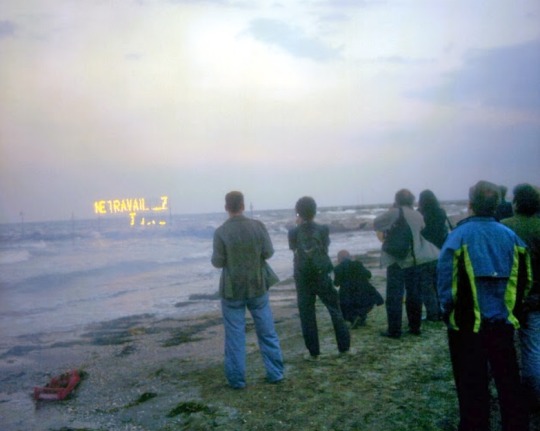

Something happened *

© Maurizio Nannucci

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

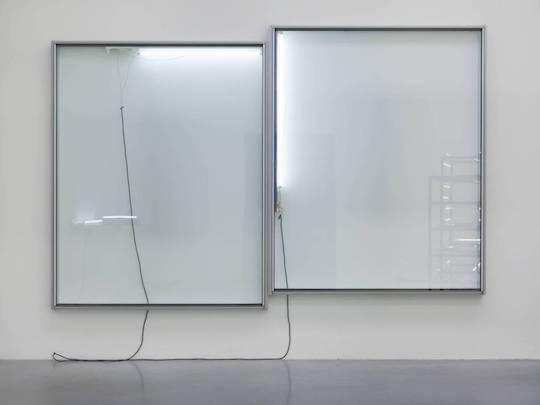

Maurizio Nannucci

What to see what not to see, 2021

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

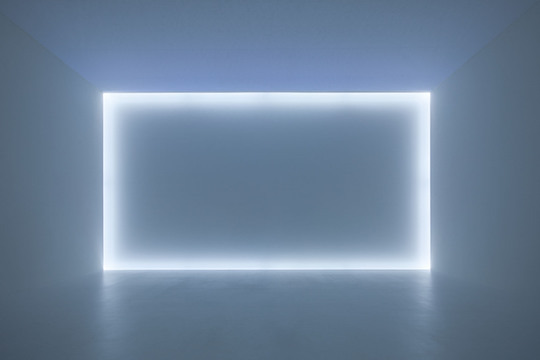

Let the Light In.

Christian Kerez - Chapel, Oberrealta

::

Laddie John Dill

::

neon, not neon

::

Pedro Cabrita Reis

::

after Pedro @ Chinati, Marfa TX

::

Monika Wulfers - Five Equal Lines not a Pentagon X

::

Jun Ong - Star, Malaysia

::

Maurizio Nannucci

::

Cerith Wyn Evans - Leaning Horizons

::

Nina Canell

::

Janet Echelman - installation Lumiere, London

::

Jan van Munster

::

Dan Flavin - 1976, Varese Corridor

::

Dan Flavin @ Chinati, Marfa TX

::

Doug Wheeler

::

Wednesday: beach days

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Art-Experience - “No Vitrines, No Museums, No Artists. Just a lot of people”.

19-23/05/04 “ workshop con Rirkrit Tiravanija, Philippe Parreno, Pierre Huyghe e Maurizio Nannucci, a Venezia.

5 giorni di incontri e approfondimenti su temi artistici coordinati da Rirkrit Tiravanija.

5 days of meetings and deeping on artistic themes coordinated by Rirkrit Tiravanija

relatori/ relators : Richard Shusterman, Daniel Birnbaum, Maurizio Nannucci; serata / evening with IUAV student IUAV and Giorgio Agamben. Performance di R.Tiravanija al Lido di Venezia.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maurizio Nannucci, Not All at Once, 1992/2011

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

seen at Peggy's place (October 2024)

photos: optikes

Maurizio Nannucci was born in Florence on April 20, 1939. He studied at Florence’s Fine Art Academy and in Berlin before working for many years with experimental theater groups as a set designer. During the first half of the 1960s, he consolidated the basic elements of what would become his visual language by exploring the relationship between art, language, and image, and by creating the first Dattilogrammi, in which words reclaim their strength as symbols. At the same time he was in contact with Fluxus artists, developed an interest for visual poetry, and collaborated with the studio “S 2F M” (Studio di Fonologia Musicale, Florence) to produce electronic music. Nannucci focused on using voices and words to produce sound installations.

In 1967, during his first solo exhibition at the Centro Arte Viva, Trieste, he presented his first neon light texts, thus emphasizing the temporary quality of writing and not the material quality of objects. In 1968 he founded the Exempla publishing house in Florence and Zona Archives Edizioni, both of which published books and catalogues on artists like John Armleder, Robert Filliou, Ian Hamilton Finlay, James Lee Byars, and Sol LeWitt. Nannucci believes that publications and multiples are themselves manifestations of a type of artistic practice that considers art a mental process, one that can be applied to the mass production of everyday objects in order to unify divergent threads in art. The art object may lose its uniqueness, but it gains presence and new freedom.

During the 1990s the artist renewed his interest in the relationship between works of art, architecture, and urban landscape by collaborating with the architects Auer & Weber, Mario Botta, Massimiliano Fuksas, and Renzo Piano. Some of his permanent installations can be seen at the Auditiorium of the Parco Della Musica and Fiumicino airport, both in Rome, and at the Bibliothek des Deutschen Bundestages, Berlin. Nannucci has been a featured artist at the Venice Biennale several times and has participated in Documenta, Kassel, and the São Paulo, Sydney, Istanbul, and Valencia biennials.

Alexander Calder was born July 22, 1898, in Lawnton, Pennsylvania. In 1919, he received an engineering degree from Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken. Calder attended the Art Students League, New York, from 1923 to 1925, studying briefly with Boardman Robinson and John Sloan. As a freelance artist for the National Police Gazette in 1925, he spent two weeks sketching at the circus and developed a particular fascination for the subject. He also made his first wire sculpture in 1925, and the following year he made several constructions of animals and figures with wire and wood.

Calder’s first exhibition of paintings took place in 1926 at the Artist’s Gallery, New York. Later that year, he went to Paris and attended the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. In Paris, he met Stanley William Hayter, exhibited at the 1926 Salon des Indépendants, and began giving performances of his miniature circus. The first show of his wire animals and caricature portraits was held at the Weyhe Gallery, New York, in 1928. That same year, he met Joan Miró, who became his lifelong friend. Subsequently, Calder divided his time between France and the United States. In 1929, the Galerie Billiet gave him his first solo show in Paris. He met Frederick Kiesler, Fernand Léger, and Theo van Doesburg and visited Piet Mondrian’s studio in 1930. Calder began to experiment with abstract sculpture and in 1931 and 1932 introduced moving parts into his works. These moving sculptures were called “mobiles,” while his stationary constructions were to be named “stabiles.”

He exhibited with the Abstraction-Création group in Paris in 1933. In 1943, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, gave him a retrospective. During the 1950s, Calder traveled widely and executed Towers (wall mobiles) and Gongs (sound mobiles). He won the Grand Prize for Sculpture at the 1952 Venice Biennale. Late in the decade, the artist worked extensively with gouache. During this period, he executed numerous major public commissions. In 1964–65, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, presented a Calder retrospective. He began the Totems in 1966 and the Animobiles in 1971, both of which are variations on the standing mobile. A Calder exhibition was held at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, in 1976. Alexander Calder died November 11, 1976, in New York.

guggenheim-venice.it

0 notes

Text

Poésie Concrète, Texts by Paul Bernard, Gabriele Detterer, and Maurizio Nannucci, MAMCO, Genève, 2022

0 notes