#mastozoology

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

wolf skull (tags are in spanish but it isn't too different from English)

#scientific illustration#canis lupus#wolf#lobo#scientific art#science#zoology#mastozoology#cranium#anatomy#skull#vulture culture#vulturecore#goblincore

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here I am, researching about the rabies virus in the americas for a work presentation, and WHAT THE FUCK DO YOU MEAN THAT FUCKING SPANIARDS INTRODUCED THE RABIES TO THE NEW WORLD INTO SPECIES OTHER THAN BATS

ARE YOU FUCKING KIDDING ME

#Apparently and according to the national mastozoology association#the bat variant of rabies also gave inspiration to the modern vampire myth#what the fuuuuuuuuck

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

bby wears boots

Maned wolf in Brazil

(via)

83K notes

·

View notes

Text

DR. RODRIGO A. MEDELLÍN

He was born in Mexico City and from very early on defined his vocation to study mammals. He has worked professionally on these issues since 1975. After completing his bachelor's degree at UNAM, he earned his doctorate from the University of Florida at Gainesville. Working in diverse systems from tropical rainforests to deserts to montane forests, Rodrigo uses a diverse approach including community ecology, plant-animal interactions, population biology, and many others.

His work on community ecology and bats as indicators and as providers of environmental services such as pest control, pollination and seed dispersal have been used to justify the creation of protected natural areas or to integrate management plans. His joint work with other colleagues on protocols for listing at-risk species is now a federal law.

He has produced more than 200 publications including 98 scientific articles in international journals and more than 50 books and book chapters on bat ecology, conservation and mammalian diversity. Rodrigo was General Director of Wildlife for the Mexican Federal Government in 1995–96 and President of the Mexican Association of Mastozoology from 1997 to 1999. Within the American Society of Mammologists, he has served as Chairman of various committees, and has been a Member of the Board of Directors from 2001 to 2007.

He has been a Member of the Scientific Advisory Council of Bat Conservation International and Lubee Bat Conservancy, and founder and director of the Program for the Conservation of Mexican Bats, which turned 15 in 2009.

Rodrigo is President of the Bat Specialist Group of the World Conservation Union (IUCN), and titular researcher "C" of the UNAM Institute of Ecology, He has taught conservation biology and community ecology for more than 15 years at the undergraduate and graduate level, and served as Head of the Department of Biodiversity Ecology from 2003 to 2006. He has directed 35 undergraduate, 17 master's and 5 doctoral theses.

He is an Associate Professor at Columbia University in New York and an Associate Researcher at the American Museum of Natural History and the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. Rodrigo has been Associate Editor of four of the most important scientific journals in the field of conservation and mammals in the world: Conservation Biology, Journal of Mammalogy, ORYX, and Acta Chiropterologica.

In 2000 he was appointed representative of Mexico to the CITES Animals Committee (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora), in 2002 he was elected Representative of North America and also Vice-Chairman of the CITES Animals Committee, in 2004 and 2007, At the request of the governments of Canada, Mexico and the United States, he was re-elected to the same posts. He is part of the United Nations Millennium Project as a member of Task Force 6: Stop the Loss of Natural Resources, and continues to be an adviser to the Mexican Government on wildlife issues. He was also a member of CONACYT's Biological Sciences Project Evaluation Committee from 2005 to 2009.

In April 2004, he received the Whitley Nature Conservation Award from Princess Anna of England. In October of that year, the American Society for the Study of Bats awarded him its highest honor, the Gerrit S. Miller Award, which is conferred on people "in recognition of an extraordinary service and contribution in the field of bat biology". In November, President Vicente Fox granted Rodrigo the 2004 Nature Conservation Award. In June 2007, the American Society of Mammologists awarded him the highest conservation recognition, the Aldo Leopold Award, which is given to individuals who have made extraordinary and lasting contributions to the conservation of mammals and their habitats. In September, the University of Florida Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation recognized him as Distinguished Alumni, and in October the Wildlife Trust Alliance recognized him as the Conservation Scientist of the Year. In 2009 he received the Rolex Associate Award for Enterprise and the Volkswagen Award “For Love to the Planet” in 2011 his NGO BIOCONCIENCIA was the winner of the BBVA Foundation Award for Biodiversity Conservation Activities in Latin America. The following year, he received the Whitley Gold Award for having made the most impact with the resources received earlier. He also received the Pollinator Advocate of the Year Award and was selected as one of the "50 Individuals Moving Mexico" by Expansión and Who Magazine.

Between 2013 and 2015 he was president of the Society for Conservation Biology. During this period he also produced with the BBC the documentary The Bat Man of Mexico, which was awarded at the Bristol Festival and the New York Wild Film Festival. In 2015 he was appointed a member of the Multidisciplinary Experts Panel of the Intergovernmental Platform for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.

Becoming the 'Bat Man' of Mexico

National Geographic Explorer at Large and ecologist Rodrigo Medellín uses a multidisciplinary approach to protect and conserve bat species.

youtube

Bats don’t often get the credit they deserve for the important role they play in their native ecosystems, where they serve as pest exterminators and crop pollinators. The lesser long-nosed bat, found in northern Mexico and the southwestern United States, is one of just three bat species in North America that are responsible for pollinating cacti and agave plants across the continent.

And it's not just the plants that benefit: Bat pollination is critical to the blue agave plants from which tequila is made — a fact that just may save this particular species, thanks in part to the work of conservationist and National Geographic Explorer-at-Large Rodrigo Medellín.

Medellín, known as the “Bat Man of Mexico,” is a professor of ecology and conservation at the Institute of Ecology at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. He says he was already determined to be a bat biologist when he held a bat for the first time at just 13 years old.

“My sense of awe and admiration and curiosity was then fully sealed for life,” he says. “I felt I was facing the most amazingly interesting and misunderstood organisms on Earth, and bats really had been beckoning me.” Medellín began studying the lesser long-nosed bat over three decades ago, before the animal was listed as a threatened species in 1994.

Official Instagram

Since then, he’s been instrumental in educating farmers about the importance of bats and role in agave pollination, convincing many to set aside part of their land to allow the plants there to flower and be pollinated. Previously, farmers seeking to boost the agave’s sugar content would cut off the flowers before they could be pollinated. In fields where farmers have allowed plants to flower, however, “they’re full of food and bats are visiting—it’s nothing short of historic,’’ says Medellín. “This is the way things were done six generations ago.”

It’s more than good news for the farmers and their fields: the lesser long-nosed bat was removed from the endangered species list in Mexico. “Today many millions of people protect and defend bats” says Medellín.

“Every day of our lives is touched by one or more ecosystem service that bats provide. From your cotton shirt to your coffee to your tacos to your rice to your tequila, and much, much more, your life has been touched by bats,” says Medellín.

“Inside I continue to be that 13 year old child every time I see a bat!”

youtube

Now, as the COVID-19 pandemic causes even more harmful bat myths, the world must once again realize that bats may not be the hero everyone wants—but they’re the hero we need.

A Skeptic's Guide to Loving Bats - Overheard at National Geographic

Sources: (x) (x)

#🇲🇽#mexico#animal#STEM#bat#vampire bat#latino#hispanic#latinx#Rodrigo Medellín#rodrigo medellin#AOM#national geographic#national geographic explorer#indigenous#native#maya#UNAM#conservation#spanish#europe#colonization#imperialism#colonialism#hernan cortes#history#dracula#books#bibliophilia#plant

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Phyllostomus discolor. #bat #phyllostomus #phyllostomusdiscolor #mastozoology #biology #life #nightanimals (en Universidad del Valle - Ciudad Universitaria)

0 notes

Text

I sailed in Banderas Bay with my marine mastozoology class and im so full of gratitude and love although my skin is suffering but it doesnt matter bc i love the fact that studying these amazing creatures will be my life from now on ?????

0 notes

Photo

Rare Conjoined Bat Twins Found in Brazil

Sarah B. Puschmann

July 31, 2017

This ad will end in 15 seconds.The corpses of rare conjoined bats found in Brazil have given scientists a closer look into a phenomenon that has only ever been recorded twice before.

When Marcelo Rodrigues Nogueira, a postdoctoral researcher in biology at the State University of Northern Rio de Janeiro first saw the bat twins, he was "completely astonished," he wrote in an email to Live Science. "I have handled many bats [in my career], some with very impressive morphological characters (and bats are very special in this respect!), but none [were as] surprising as these twins."

Only two other pairs of conjoined bat twins have been reported in the scientific literature, one in 1969 and another in 2015.

Although it's not known exactly what causes identical twins to be conjoined, the phenomenon is known to occur when a fertilized egg splits too late. If an egg splits four to five days after being fertilized, two separate identical twins will form. If, however, the splitting doesn't occur until 13 to 15 days after fertilization, the fertilized egg will only separate partially, and the twins will be conjoined.

The researchers first became aware of the conjoined bats after the animals were donated to the Laboratory of Mastozoology at the Rural Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. No one from Nogueira's team, which includes embryologists Nadja Lima Pinheiro and Adriana Ventura from the Area of Embryology at the Rural Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, saw the twins right when they were found. Because of this, the scientists, aren't certain if the twins were stillborn or if they had died shortly after birth.

The bats, found under a mango tree in southeastern Brazil in 2001, are dicephalic parapagus conjoined twins, which means they're oriented side by side with their whole trunks conjoined. X-rays revealed that the twins' spines form a "Y" shape, with two separate columns of vertebrae branching off at the lower back. Ultrasound images also revealed two hearts of equal size that researchers suspect are separate, the scientists said.

Since most bats have only one pup per litter, finding even nonconjoined bat twins is rare. In the five years Daniel Urban, a postdoctoral research associate in evolutionary developmental biology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, has been studying bats, he's only ever seen a single pup flying around or hanging onto its mother, he told Live Science. Urban was the lead author of the 2015 study on conjoined bat twins that was published in the journal Acta Chiropterologica.

It's even harder to find bat twins that are conjoined. But this doesn't mean conjoined twins are rarer in bats than in any other mammals, according to Scott Pedersen, a professor of biology and microbiology at South Dakota State University, who was not involved in the new study. It's just that humans find out about conjoined bats less often than they find out about other conjoined animals, he told Live Science in an email.

Even if conjoined bats are alive when they are born, it's likely that they'll die soon after, because their bodies can't sustain them, Pedersen said. Bats also tend to live in places humans aren't located, which means even if a person were to venture into a bat's domain, the person would need to find the conjoined bats before they degraded or were scavenged.

This is only made more unlikely by the fact that bats are nocturnal, said Urban. If a mother gives birth to conjoined bats during the day, it will likely be in a protected roost, which means people wouldn't see them. She may give birth while she's out in the open, but that would occur only at night, when the twins would be obscured by darkness, Urban said.

"If you combine all these factors together, it's amazing we even have any [conjoined bat twins]," he added.

Although little is known about the organs of the recently discovered conjoined bat twins, the researchers have opted not to use any invasive methods to further investigate the animals' bodies.

"It's so rare and precious that you find something like this, you don't want to do any type of destructive sampling to look further. You're, of course, very curious about it, but they're a one-shot deal so, for the most part, they're held onto until the future where a newer technology will allow us to pursue it further without completely damaging what we already have," Urban said.

The new study was published online June 16 in the journal Anatomia Histologia Embryologia.

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Mammalogy” or “mammology”?

Q: I’m perplexed by the spelling of “mammalogy.” Shouldn’t it be “mammology” or “mammalology,” as per “biology,” “neurology,” and other subjects of study with an “-ology” suffix?

A: You’re not the first person to question the legitimacy of “mammalogy.”

People began complaining about it soon after the word showed up in English in the 19th century, but primarily for a different reason. They were bothered that it combined a noun of Latin origin, “mammal,” with a suffix of Greek origin, “-logy.”

The English word was inspired by the French term for the study of mammals, mammalogie, which appeared in 1803, three decades before the Anglicized version made it into print, according to the Oxford English Dictionary.

The earliest English example for the word in the OED is from the first volume of the Penny Cyclopaedia, published in 27 volumes from 1833 to 1843:

“The following table exhibits the peculiar characters of American mammalogy, the manner in which the different orders are distributed … and the relative proportion which the number of American species bears to the whole number in each order.”

The next Oxford citation is from the third volume of the encyclopedia, which appeared in 1835: “Fischer, the most recent writer upon mammalogy, enumerates eleven different species of baboons.”

However, the third example (from the 14th volume of the encyclopedia, published in 1839) contains criticism of the usage:

“Vicious however as the word is, the term mammalogy is in such general use by the zoologists of England and France, that it seems to be less objectionable to retain it.”

And an 1857 citation from An Expository Lexicon of the Terms, Ancient and Modern, in Medical and General Science (1860), by Robert Gray Mayne, is also critical:

“Mammalogy, an imperfect term for a treatise or dissertation on, or a description of the Mammalia.” (The treatise sense of the term is now rare.)

The OED explains that the 1839 and 1857 citations “refer critically to the word’s formation from a prefix of classical Latin origin and a suffix of ancient Greek origin, and perhaps also to its coalescence of the last syllable of mammal with the first of -ology.”

The dictionary adds that the terms “mastology n., mastozoology n., mazology n., and therology n. were all proposed as substitutes in the 19th cent.”

Getting back to your question, why is the word “mammalogy” rather than “mammology” or “mammalology”?

Well, “mammology” would be confusing and might suggest the study of breasts (“mammo-” is a combing form for breast). And “mammalology” is awkward and a bit of a mouthful.

The word that caught on, “mammalogy,” is similar to “mineralogy” and “genealogy.” In all three words, the “a” is pronounced “ah,” so the “-alogy” ending sounds the same as “-ology.”

By the way, the OED has entries for both “-logy” and “-ology” as suffixes used to form “nouns with the sense ‘the science or discipline of (what is indicated by the first element).’ ”

The initial “o” in “-ology” words is generally considered a connective, or combining vowel. And this “o” often originates in the first element of the word rather than in the suffix.

The subject of study in “theology,” for example, is theos, Greek for God. The English word combines “theo-” and “-logy.” Similarly, the subject in “mythology” is mythos, Greek for story, and the subject in “biology” is bios, Greek for life.

As the Chambers Dictionary of Etymology explains, “the -o- is considered a connective, though in many instances it belonged to the preceding element as a stem-final or thematic vowel.” So the “o” in many “-ology” words evolved from the last letter or the key vowel of the subject of study.

In a 2014 post on the blog, we note that the ultimate source of “-ology” and “-logy” is the “Greek logos (variously meaning word, speech, discourse, reason). Added to the end of a word, -logos means one who discourses about or deals with a certain subject, as in astrologos (astronomer).”

We should also mention that the suffix is often used to form humorous nonce words, terms created for one occasion.

Here’s an 1820 example from William Buckland, an English theologian and Dean of Westminster: “Having allowed myself time to attend to nothing there but my undergroundology.” (From an 1894 biography of Buckland by Elizabeth Oke Gordan, his daughter.)

Help support the Grammarphobia Blog with your donation. And check out our books about the English language.

from Blog – Grammarphobia http://www.grammarphobia.com/blog/2017/01/mammalogy.html

0 notes

Text

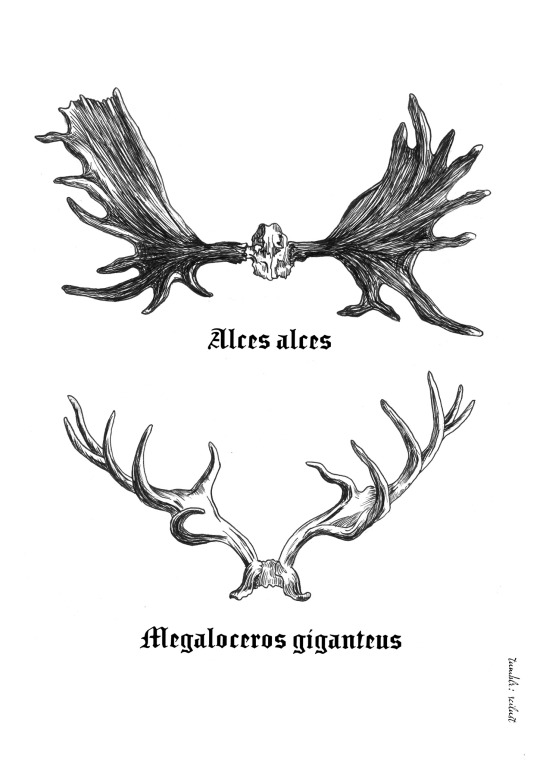

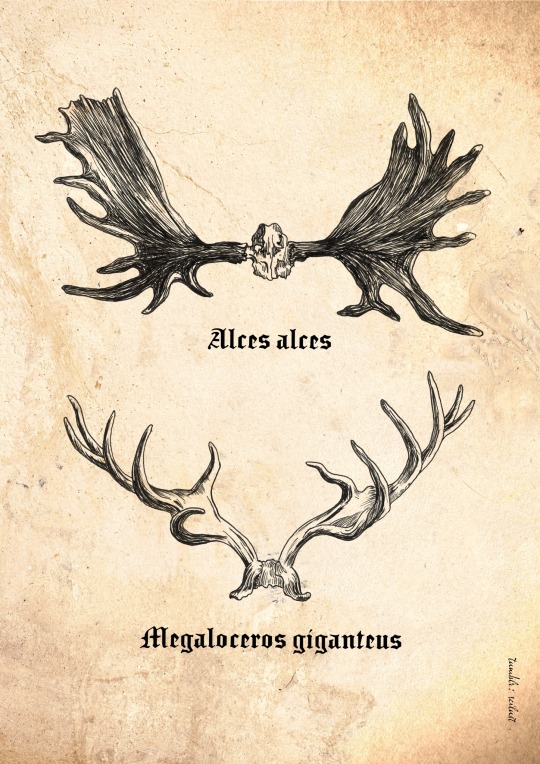

Alces alces and Megaloceros giganteus

I visited Glasgow's Kelvingrove Museum a few years ago and I marvelled with the magnitude of the Irish Elk skeleton they had on display so...I guess that's where I got the inspiration from

Disclaimer: these are not scaled, Megaloceros' are way larger

#scientific illustration#scientific art#zoology#paleontology#mastozoology#anatomy#antlers#megaloceros#irish elk#moose#alces alces

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Al final fue un día bonito para ver animalitos 💕🐵🐣🐦🕊🐿🐭 -Myotis nigricans -Carpintero real -Elaenia flavogaster

#animalia #animals #bat #bird #woodpecker #zoology #ornithology #mastozoology #myotis #Elaenia #Tyrannidae #biology (en Universidad del Valle - Ciudad Universitaria)

#bat#biology#animals#zoology#ornithology#animalia#woodpecker#elaenia#mastozoology#tyrannidae#myotis#bird

0 notes

Photo

Maternidad. Hembra preñada de Artibeus lituratus. #bat #mastozoology #zoology #biology #life #animals (en Universidad del Valle - Ciudad Universitaria)

0 notes