#masterworks of world literature

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

conflict of sticking with my environmental planning degree plan and a potentially more stable/well paying job vs wanting to go for an arts degree in literature analysis and writing and history and culture because i love it so so much but know it wont be considered ‘useful’. FIGHT

#like. did i pick this. yes.#but only because i like plants#and i like outdoor spaces#and when doing research it was a well paying and open field job-wise#however#while planning my courses i was looking under my ‘dicipline based writing’ requirement#and while i know i need to take something related to my major#oh my god#masterworks of world literature#fairytales then and now#enchanted worlds (course on germanic folk tales)#a course entirely on the age of reformation#a whole course on banned books#world cinema#politics of food and sex#extinction. an entire course on the extinction process. it goes into fossils and cultures and ethnic groups and languages and#endangered species and human extinction. that sounds so fucking cool and also extremely depressing#like. i wanna take all of these. i wanna learn!!!#but noooooo i have to pay thousands of dollars and deal with an extreme amount of stress with competing coursework and thinking about future#career paths. like. ok it’s late and these are late night thoughts. but i wanna be able to just take classes like these. and learn.#why do i have to be working towards a degree. why does there have to be an end goal. why can’t i just learn and write essays#why did they make learning stressful#and like. all of these are awesome. but realistically woudlnt work with my major. at all.#i could take extinction but there’s another course that fits my major way better that i /should/ take#me rambling#i think it’s funny there’s also a course called capitalism and debt. they just tell you don’t go to college because they take all your money#anyways. hoping that i get over it#or that i get a well enough paying job that i can take college courses when im old and still want to learn#edit: THEY ALSO HAVE A COURSE CALLED TALES OF HORROR#HISTORICAL SND POLITICAL CONTEXT OF HORROR STORIES

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

I don’t know who types up the ask answers on this blog but to whoever’s reading this: how do you all feel about being alive and sentient? What keeps you going, what purpose propels you through this chaotic void? What do you think (or hope) waits for you after your inevitable end? What do you think constitutes a life well lived?

I'm going to answer this in the most wayward and stupidly overlong manner possible, because the previous ask had me thinking about puppets, and I was already mid-way through writing up a book recommendation that's semi-relevant to your questions.

Everyone (but especially people who've enjoyed The Silt Verses and all the folks on Tumblr who loved Piranesi by Susanna Clarke) ought to seek out Riddley Walker by Russell Hoban.

Riddley Walker is a wild and woolly story set in post-apocalyptic Kent, where human society has (d)evolved into a Bronze Age collective of hunter-gatherer settlements. Dogs, apparently blaming us for our crimes against the world, have become our predators, hunting us through the trees. Labourers kill themselves unearthing ancient machinery that they cannot possibly understand.

A travelling crowd of thugs led by a Pry Mincer collect taxes and attempt to impose themselves upon those around them with a puppet-show - the closest possible approximation of a TV show - that tells a mangled story of the world's destruction, featuring a Prometheus-esque hero called Eusa who is tempted by the Clevver One into creating the atomic bomb.

Riddley himself, a twelve-year-old folk hero in-the-making surrounded by strange portents, ends up sowing the seeds of rebellion and change by becoming a conduit for the anti-tutelary anarchic madness (one apparently buried in our collective unconscious) of Punch 'n' Judy.

It's a book in love with twisted reinterpretation, the subjectivity of interpretation, buried or forbidden truths coming back to light (the opening quote is a curious allegory about reinvention and cyclical change from the extra-canonical Gospel of Thomas, which is a good joke and mission statement on a couple levels at once) and human beings somehow stumbling into forms of wisdom or insight through clumsy and nonsensical attempts to make sense of a world that is simply beyond them.

It rocks.

The book starts like this:

On my naming day when I come 12 I gone front spear and kilt a wyld boar he parbly the las wyld pig on the Bundel Downs any how there hadnt ben none for a long time befor him nor I aint looking to see none agen. He dint make the groun shake nor nothing like that when he come on to my spear he wernt all that big plus he lookit poorly. He done the reqwyrt he ternt and stood and clattert his teef and made his rush and there we wer then. Him on 1 end of the spear kicking his life out and me on the other end watching him dy. I said, 'Your tern now my tern later.'

Riddley's devolved language - a trick which has been nicked/homaged by many other works, most notably Cloud Atlas and Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome - is a masterwork choice which may seem offputting or overwhelming at first, but which has its own brutal poetry and cadence to it, and ultimately which makes us slow down as readers and unpick the wit, puns, double-meanings and playful themes buried in line after line.

(Even those first five sentences get us thinking about cyclical change, ritual and myth in opposition to the dissatisfactions of reality, and 'tern' to paradoxically indicate a rebellious change in direction but also an obedient acceptance of inevitable death.)

In one of my favourite passages in literature and a statement of thought that means a lot to me, Riddley has been smoking post-coital weed with Lorna, a 'tel-woman', who unexpectedly declares her belief in a kind of irrational, monstrous Logos that lives in us, wears us like clothes, and drives us onwards for its own purpose:

'You know Riddley theres some thing in us it dont have no name.' I said, 'What thing is that?' She said, 'Its some kynd of thing it aint us but yet its in us. Its lookin out thru our eye hoals...it aint you nor it dont even know your name. Its in us lorn and loan and shelterin how it can.' 'Tremmering it is and feart. It puts us on like we put on our cloes. Some times we dont fit. Some times it cant fynd the arm hoals and it tears us a part. I dont think I took all that much noatis of it when I ben yung. Now Im old I noatise it mor. It dont realy like to put me on no mor. Every morning I can feal how its tiret of me and readying to throw me a way. Iwl tel you some thing Riddley and keap this in memberment. What ever it is we dont come naturel to it.' I said, 'Lorna I dont know what you mean.' She said, 'We aint a naturel part of it. We dint begin when it begun we dint begin where it begun. It ben here befor us nor I dont know what we are to it. May be weare jus only sickness and a feaver to it or boyls on the arse of it I dont know. Now lissen what Im going to tel you Riddley. It thinks us but it dont think like us. It dont think the way we think. Plus like I said befor its afeart.' I said, 'Whats it afeart of?' She said, 'Its afeart of being beartht.'

While Hoban is, I think, deeply humanistic to his bones and even something of a wayward optimist, the notion of human beings as helpless and ignorant vessels, individual carriers - puppets, if you like - for an unknowable and awful inhuman power-in-potentia and life-drive that lacks a true shape or intent beyond its own continued survival (even when that means destroying us or visiting us with agonising atrophy in the process) conjures up the pessimism of Thomas Ligotti, another big influence on our work and a dude who was really into his marionettes-as-metaphor.

Let's go to him now for his opinion on the thing that lives beneath our skin. Thomas?

Through the prophylactic of self-deception, we keep hidden what we do not want to let into our heads, as if we will betray to ourselves a secret too terrible to know… …(that the universe is) a play with no plot and no players that were anything more than portions of a master drive of purposeless self-mutilation. Everything tears away at everything else forever. Nothing knows of its embroilment in a festival of massacres… Nothing can know what is going on.

Curiously, both Ligotti and Riddley Walker have appeared in the music of dark folk band Current 93, whose track In The Heart Of The Wood And What I Found There directly homages the novel and ends with the repeated words,

"All shall be well," she said But not for me

These words, in turn, hearken back to Kafka's* famous reported conversation with Max Brod:

'We are,' he said, 'nihilistic thoughts, suicidal thoughts that rise in God's head.' This reminded me of the worldview of the gnostic: God as an evil demiurge, the world as his original sin. 'Oh no', he said, 'our world is only a bad, fretful whim of God, a bad day.' 'So was there - outside of this world that we know - hope?' He smiled: 'Oh, hope - there is plenty. Infinite hope, just not for us."

So, we walk on.

We carry this thing that's riding on our backs, endlessly bonded to it, feeling its weight more and more with every passing day, unable to turn to look at it. Buried truths come briefly to life, and are hidden from us again. Perhaps they weren't truths at all. We couldn't stand to look the truth directly in the eyes in any case.

If there is hope, it's for the thing that looks out from our eyeholes, which thinks us but cannot think like us. We'll never get to where we're going, and the thing will never be born. There's no hope for it. Perhaps we don't want it to win anyway. It's nothing, and the key to everything.

The Jesus from the Gospel of Thomas says:

'When you see your own likeness, you rejoice. But when you see the visions that formed you and existed before you, which do not perish and which do not become visible - how much then will you be able to bear?'

Kafka, writing to his father, begins by expressing the inexpressibility of his own divine terror:

You asked me why I am afraid of you. I did not know how to answer - partly because of my fear, partly because an explanation would require more than I could make coherent in speech…even in writing, the magnitude of the causes exceeds my memory and my understanding.

Kafka concludes that while he cannot ever truly explain himself, and that the accusations in his letter are neat subjectivities that fail to account for the messiness of reality, perhaps 'something that in my opinion so closely resembles the truth…might comfort us both a little and make it easier for us to live and die.'**

It doesn't bring comfort to Kafka, whose diarised remarks both before and after the 1919 letter make it clear that he views his relationship with the things (people) that birthed him as an endless entrapment that prevents him from attaining any kind of self-actualisation or even comfort, since he cannot escape their influence or remember a time before them:

I was defeated by Father as a small boy and have been prevented since by pride from leaving the battleground, despite enduring defeat over and over again.

It's as if I wasn't fully born yet...as if I was dissolubly bound to these repulsive things (my parents).*** The bond is still attached to my feet, preventing them from walking, from escaping the original formless mush. That's how it is sometimes.

Samuel Beckett returns again and again (aptly) to this pursuit of a state of true humanity and final understanding that is at once fled and unrecoverable, yet to be born, never to be born, never-existed, endlessly to be pursued, pointless to pursue. From the astonishing end sequence of The Unnameable:

alone alone, the others are gone, they have been stilled, their voices stilled, their listening stilled, one by one, at each new-com- ing, another will come, I won’t be the last. I’ll be with the others. I’ll be as gone, in the silence, it won’t be I, it’s not I, I’m not there yet. I’ll go there now. I’ll try and go there now, no use trying, I wait for my turn, my turn to go there, my turn to talk there, my turn to listen there, my turn to wait there for my turn to go, to be as gone, it’s unending, it will be unending, gone where,where do you go from there, you must go somewhere else, wait somewhere else, for your turn to go again

I’m not the first, I won’t be the first, it will best me in the end, it has bested better than me, it will tell me what to do, in order to rise, move, act like a body endowed with despair, that’s how I reason, that’s how I hear myself reasoning, all lies, it’s not me they’re calling, not me they’re talking about, it’s not yet my turn, it’s someone else’s turn, that’s why I can’t stir, that’s why I don’t feel a body on me, I’m not suffering enough yet, it’s not yet my turn, not suffering enough to be able to stir, to have a body, complete with head, to be able to understand, to have eyes to light the way

From Thomas' Jesus:

When you make the two one, and you make the inside as the outside and the outside as the inside and the above as the below, and if male and female become a single unity which lacks 'masculine' and 'feminine' action, when you grow eyes where eyes should be and hands where hands should be and feet where feet should stand and the true image in its proper place, then shall you enter heaven.

Tom's Jesus makes a particularly Gnostic habit of both insisting that the hidden will be revealed and demonstrating the impossibility of attaining a state where the hidden ever can be revealed. Contrary to C.S. Lewis, we will never have faces with which to gaze upon the lost divine and the mysteries that shaped us, and crucially, as Christ puts it, we would not be able to bear the sight of ourselves if we did.

We will never become the thing that's riding on our backs.

Jesus again:

The disciples ask Jesus, 'Tell us how our end shall be.' Jesus says, 'Have you found the beginning yet, you who ask after the end? For at the place where the beginning is, there shall be the end.'

The Unnameable:

I’ll recognise it, in the end I’ll recognise it, the story of the silence that he never left, that I should never have left, that I may never find again, that I may find again, then it will be he, it will be I, it will be the place, the silence, the end, the beginning, the beginning again, how can I say it, that’s all words, they’re all I have, and not many of them, the words fail, the voice fails, so be it

The final passage of The Unnameable, which often is hilariously shorn and misinterpreted as an inspirational quote about how if you don't succeed, try again:

all words, there’s nothing else, you must go on, that’s all I know, they’re going to stop, I know that well, I can feel it, they’re going to abandon me, it will be the silence, for a moment, a good few moments, or it will be mine, the lasting one, that didn’t last, that still lasts, it will be I, you must go on, I can't go on, you must go on. I’ll go on, you must say words, as long as there are any, until they find me, until they say me, strange pain, strange sin, you must go on, perhaps it’s done already, perhaps they have said me already, perhaps they have carried me to the threshold of my story, before the door that opens on my story, that would surprise me, if it opens, it will be I, it will be the silence, where I am, I don’t know. I’ll never know, in the silence you don’t know, you must go on, I can’t go on. I’ll go on. †

We bear this thing that's riding on our backs. We'll never get to where we're going, and the thing will never be born. If it was born, it'd be too terrible for us to bear. There's nothing riding on our backs.

It will never speak us into being.

We keep on calling out into the silence, we keep trying to explain or understand the thing that's riding on our backs, searching for a way to birth it before we die. Our words about the thing are crucial, and they're meaningless, and they're all we have, and they're nothing at all. We cannot name it and we cannot express it, but we cannot stop trying, and we will keep turning back to our words about the thing, obsessing over them, tearing them to pieces, putting them back together.

I'm fumbling at something I can't think or say, but fumbling is all we're capable of. There could be beauty and meaning and comfort in the fumbling, but it's also vain, and foolish, and pointless, and we're lying to ourselves about the beauty and the meaning and the comfort, and we're indulging ourselves pointlessly by going on and on about the pointlessness of it. Nothing can know what's going on. We will never get close enough to understand without being destroyed.

Thomas' Jesus again, warning those who seek to reveal what's hidden:

He who is near me is near the fire.

Riddley Walker, reflecting on the Punch puppet's inexplicable desire to cook and eat his own child:

Whyis Punch crookit? Why wil he al ways kill the baby if he can? Parbly I wont ever know its jus on me to think on it.

If you got to the end of this, congratulations: but the above is honestly the most appropriate patchwork of what I believe, what propels me, what I feel.

As for what comes after life, I think it's fairly straightforwardly a nothingness we are tragically incapable of fully knowing or accepting - it's Beckett's unimaginable and unattainable silence, a silence that his characters' voices keep on shattering even as they cry out for it.

-Jon‡

*I can't remember if Kafka makes prominent reference to Czech puppets in his work, which is interesting in its own right given the thematic relevance (the protagonist in The Hunger Artist is perhaps a kind of self-directing puppet show?).

However, Gustav Meyrink - who some unsourced Google quotes suggest was pals with Czech puppeteer Richard Teschner - did write a strange little story, The Man On The Bottle, about an audience watching a 'marionette show' who are too wrapped up in performances and masks to interpret the reality that they're actually watching a human being suffocate to death.

**Thomas Ligotti: "Something had happened. They did not know what it was, but they did know it as that which should not be.

Something would have to be done if they were to live with that which should not be.

This would not (be enough); it would only be the best they could do."

***Beckett's Malone Dies actually kicks off with a related sentiment:" I am in my mother’s room. It’s I who live there now. I don’t know how I got there...In any case I have her room. I sleep in her bed. I piss and shit in her pot. I have taken her place. I must resemble her more and more."

† I don't necessarily align myself in humour with Ligotti on a lot of this stuff but I imagine he would recognise both Beckett's writing and Kafka's frustrations re explaining the causes of his hatred for his father as sublimation: finding artistic and philosophical ways of sketching the inexpressible horror and uncertainty of our existence in order to reckon with it at a remove without destroying ourselves. A higher form of self-deception, but self-deception nevertheless.

‡Muna's more of an anarcho-nihilist, I think.

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fortnight of Books: Day 1

Overall - best books read in 2023?

Of new-to-me books, the standouts of my year include (in rough chronological order of when I read them):

Endurance by Alfred Lansing: Thrilling and harrowing account of Shackleton's South Pole expedition. It made me very grateful as I went through my day-to-day life--no matter how bad things were, at least I had eaten things that weren't seal meat.

Daisy Miller and Washington Square by Henry James: Short, sad little novellas that drew me in with their compassionate realism and added a new name to my list of favorite classic authors.

A Field Guide to Mermaids by Emily B. Martin: Beautifully illustrated book that provides a detailed world of mermaid species and provides lots of interesting facts about the natural world. Child me would have loved this.

Mary Barton by Elizabeth Gaskell: I hated the ending, and the structure was very weird, but this was a look at a side of Victorian London I rarely see in literature, with some great characters and a really interesting dive into the issues in the background of North and South.

Team of Rivals by Doris Kearns Goodwin: It gave me an obsession with Lincoln's Cabinet. I still sometimes stop and think, "I need to read about some Seward shenanigans."

Destiny of the Republic by Candice Millard: Extremely readable history book that provided a lot of food for my obsession with James Garfield's and Chester Arthur's presidencies.

The Q by Beth Brower: Victorian Ruritanian fiction about a female newspaper tycoon that has a murky plot but also one of my favorite romantic couples of the year, one of the best tributes to autumn I've read, and most importantly (the real reason it's on this list), introduced me to the author of my favorite series of the year (more below).

Desire and The Good Comrade by Una L. Silsberrad: Forgotten turn-of-the-century women's fiction with some great female leads trying to find a place in society. Desire is a bit more literary while The Good Comrade is a bit more fun, but both were just the type of story that tends to make my list of favorites.

The Romance of a Shop by Amy Levy: Fun sister story with some fun romances. Very easy to read and provided a fascinating look at the world of Victorian photography.

The Law and the Lady by Wilkie Collins: I was so invested in the main character, a woman who would overcome anything that tried to stop her from helping her husband.

The Heir of Redclyffe by Charlotte Mary Yonge: The prose is dense and the author's too preachy, but this had some of my favorite characters of the year (Charles Edmonstone my beloved).

Best series you discovered in 2023?

The Unselected Journals of Emma M. Lion. If it weren't for this question, it would be at the top spot in the last list. They hit so many sweet spots for my perfect comfort read--Victorian England, memorable characters, lightly fantastical setting, fun narrative voice, friendships and comedy and heartbreak and literature and just so much fun.

Best reread of the year?

Definitely The Lord of the Rings. I had liked the series after my first read, but my appreciation was mostly bolstered by the fact that I'm surrounded by a huge fandom for it. This year's reread made me truly appreciate it for the masterwork it is and made it a cornerstone of my interior life.

If it weren't for that, this spot would go to A Christmas Carol, because I was shocked to find that it really is good enough to earn its dominant place in pop culture. The descriptions of Christmas are some of the best things in literature.

#fortnight of books 2023#books#i wanted to start on the first but alas#i think i'll try to catch up over the next few days

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Reviews: The Golden Compass - Philip Pullman

Rating: 5/5

The His Dark Materials trilogy has, by this point, earned its status as a children's fantasy classic, right alongside the series that inspired it, The Chronicles of Narnia. Taking place across a series of universes, most of which are quite unlike our own, His Dark Materials wrestles with many questions, but perhaps none so central as what it means to be a child in a world that is, even at the best of times, dark and unknowable.

This first book in the trilogy, The Golden Compass, does an excellent job of thrusting that question into the forefront. When protagonist Lyra Belacqua (later Silvertongue) discovers that her best friend Roger has been kidnapped by the mysterious Gobblers, she makes it her mission to rescue him from what she is sure is certain death. Her journey takes her far into the arctic north, among witches and armored bears, and finally into another world altogether.

Throughout the past several decades since this book's publication, there have been many who have argued whether it can truly be considered children's literature. After all, the vocabulary is decently high-level for a middle grade book, and apart from contending with questions of childhood, the book also delves into theology and gets pretty graphically brutal at times. But having now re-read this book as an adult (when I previously read it as a middle-grade child myself), I can say with certainty that this first book, at the very least, is definitively for children, because of the childist perspective it employs.

A childist perspective is when the world is considered from the point-of-view of a child. In fiction, this means not only having a child as the point-of-view character, but also focusing on issues and power structures that specifically affect children: namely, that the adults in the world have power over them, for good or ill. As Maria Nikolajeva states in her book Power, Voice and Subjectivity in Literature for Young Readers:

"The adults have unlimited power in our society, as compared to children, who lack economic resources of their own, lack voice in political and social decisions, and are subjected to a large number of laws and rules which the adults expect them to obey without interrogation. This is regarded as norm, in real life as well as literature. Not least is school depicted in children's books, from Tom Sawyer to Pippi Longstocking and beyond, as a mechanism for oppression. But what happens if the adults are no longer the smartest, the richest and the most powerful in the child/adult relationship?"

This is the function of the childist perspective in children's literature: to highlight the power imbalance between adults and children, but in such a way that allows the child — through the power of the point-of-view child character — to have a voice, to be heard, to have their view, perspective, and feelings validated, often by being the ones who are correct, more so than the adults in the story.

One reviewer of this book on [goodreads] has noted this, but did so with alarm; they recommend not allowing children to read this book, because it depicts the adults Lyra should trust the most (her parents) as villains, and that the adults who do help her are side characters whom Lyra ultimately leaves to go on her adventure by herself. To this I say: welcome to children's literature, or at least children's literature that is written for children, to uplift and inspire them, rather than be used as another tool to will them into submission. Children's literature centers children as the heroes, and centers children's concerns as real concerns; even the book the reviewer did recommend, Harry Potter, features mostly useless or antagonistic adults, leaving Harry and his friends (children themselves) to solve everything.

But the reviewer was tangentially correct about one thing, and it is what I said earlier in the review: The Golden Compass is a masterwork of childist literature, and here is why:

This is a fantasy book, with curious worldbuilding (who hasn't wanted a daemon at some point in their lives?) and a plot that moves along at a strong pace. But it is also, before anything else, Lyra's story. It is the story of a girl who wasn't raised by parents, but rather by servants and scholars at a college. A girl who, in the beginning of the book, wants nothing more than to run wild playing for the rest of her days, who resists lectures because they're boring, and who lives in fear of the adults in her life beating her. (It is mentioned many times in the beginning that Lyra has been physically assaulted by the adults in her life, and her father outright threatens to break her arm in the very beginning because she dared enter a room.) The central villains of the book are an organization of adults who kidnap children, spiriting them away from their families to a cold, remote place in the north in order to cut away their daemons (essentially ripping out their souls). At one point at the end of the book, Lyra sobs and wonders aloud why so many adults in the world want to hurt children so badly, why they hate them so. And while there have been adults in the book who have helped her, she had to fight to have her voice heard and listened to even among them, because they were certain they knew better than she did until they were outright proven wrong.

All of this settles The Golden Compass firmly into the childist perspective. There is much going on in the world, particularly politically, that Lyra doesn't understand; this is something that she knows and acknowledges. But the principle horrors of the book directly center children; Lyra has to go on this adventure and is the one needed to save the day despite so many adults trying to sideline and not listening to her. Ultimately, she is the one to rescue the kids from Bolvangar (despite the gyptians not wanting to take her at first), she is the one to get Iorek Byrnison back on his throne by tricking Iofur Raknison (something Iorek told her would be impossible), and she is betrayed by her father in the worst possible way, yet then sets off to thwart his plans in spite of it.

There is no question that this book brings concepts of theology to the forefront as well, as well as doses of violence; but neither thing is unheard of in children's literature, nor should it be. As the childist perspective teaches us, children do experience these things as well. As much as it shouldn't be the case, children are sometimes abused as Lyra was, children are dismissed by well-meaning adults as Lyra was, and children are sometimes introduced to religion very early, as Lyra was. If children can experience these things in their real, actual lives, there is no reason why they shouldn't be able to experience them in a book — especially one that sets them as the hero.

All of this is to say: this is a classic work of children's fantasy for a reason. It serves its purpose of being a children's book fantastically, and it's also just a thoroughly enjoyable read, with imaginative worldbuilding, unique and multifaceted characters, and an adventure plot that moves along at exactly the right pace. Even though it is a children's book, anyone of any age would be able to enjoy it, so long as they enjoy fantasy; and if they do, then I highly recommend they give this one a shot.

#book reviews#his dark materials#the golden compass#bookblr#crossposted from goodreads#date reviewed: January 21st 2025

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books read in 2023:

The secret life of bees (Jan 6) 4/5 (probably would have enjoyed it more when I was younger. Great overall but still the mammy stereotype. Don’t like it when poc women are portrayed as ~divine creatures~ we are just normal people and we just wanted to treated like normal people. Nothing more, nothing less. Too flowery and cliche at parts but still good overall.)

I’m glad my mom died (Jan 15) 5/5 (funny and thrilling. Reading this would probably help a lot of people with toxic parents think through their own trauma)

Evil Under the Sun (Jan 17) 4/5 (simple and entertaining. Not a masterwork of literature but satisfying nonetheless. A bit slow to get started but great overall)

The hunting party (Feb 4) 4/5 (found hard to get into it/get invested because of unlikeable cast of characters but stil high rating for unexpected ending. I was bored a few times in the beginning and middle parts but it really picked up in the end and made up for it. Would make a great movie)

Sparkling cyanide (audiobook) (Feb 20) 3/5 (good to listen to while doing other work around the house. Probably not worth it to take separate time out to read)

Last bus to Woodstock (Feb 24) 3/5 (hated the main detective and how he went about the investigation eg. relying on instinct and chance discoveries. But the side characters were super interesting and the ending was unexpected. Would have liked it better if inspector Lewis was the main character. No decent female characters. Only wh*res or the "shrill wife." But the crime itself was interesting and I liked the writing style).

And then there were none (audiobook) (Feb 26) 5/5 (Omg. I was in thrall throughout. My favorite Agatha Christie book I’ve read so far. I actually thought there had to be a supernatural explanation lol)

The dark remains (feb 26) 3/5 (not bad. Just boring. Can tell it was written by a dude. Not one interesting character despite being set in the gang world. Very cliche type of noir)

The Falls (Ian Rankin) (March 1) 4/5 (great buildup but disappointing payoff. Loved the concept of the quizmaster. Very likable the main detectives and very interesting plot. Sustains you throughout despite being so long. But yeah. Didn’t quite like the solution to the murder)

Wire in the blood (March 22) 5/5 (excellent. Gory but excellent. What a plot!)

The distant echo (March 30) 5/5 (omg. If someone asks me what’s your favorite crime fiction book I’d say this one! Very suspenseful and unpredictable loved it loved it loved it!!!!)

The Guest List (April 13) 6/5 (this surpasses the distant echo. This actually made me feel things. The amount of gasps I gusped could have powered the state of Texas for a year. Absolutely loved it. )

East of Eden (May 15) 100/5 (what kind of genius do you have to be to write such a book?

In Cold Blood 4/5 (May 30) maybe bc I already knew the story, I kinda had to force myself to finish this

Macbeth 5/5 (June 14) iconic

Northanger Abby by Val Mcdermid 4/5 (June 17) fun modern retelling. Expected a crime and twist but it was faithful to the original. Enjoyed reading.

Gone girl 6/5 (June 24) omg her mind. Will definitely read more by her. Wish I hadn’t seen the movie before so I could have been fully surprised. Liked the ending.

The Pearl (5/5) (July 3) not a page turner but a good depiction of reality. Very sad.

Age of Vice 3/5 (July 7) great beginning but I didn’t like the ending. I think the author tried to put too many stories and perspectives in one. That whole bit of Sunil was unnecessary? It just slowed the story down at such a crusial moment. And Sunny’s backstory with Vicky too. I don’t think it was necessary to have an unbelievably tragic backstory for every character and he already had his deal with his dad. Some things are never clarified like what happened to his mom, his true relationship with Vicky. Why Ajay agreed. Ajay turns out of be such a loser in the end. Maybe it’s “realistic” but lots of things that happen in this book are not realistic so I don’t know why only the ending has to be realistic. I wish I could have followed Ajay’s journey to a good ending.

Milk fed 2/5 (August 12) only read bc of booktok. Good seeds here and there. didn't realy like it.

The club (5/5) (august 19) excellent, gripping. A bit longer than it needed to be though.

The grownup Gillian Flynn (4/5) (October 19) great short story. Great writing. So engaging. Perfect length for getting back into reading

Emma by charlotte Brontë and another lady (5/5) (Nov 2) love. Mr. Ellin needs to be played by Simon Baker in a movie.

A room of one’s own by Virginia Woolf (Nov 11) (1000/5). This has been on my to read list for ages. I see quotes from this everywhere and every time I’m astounded by how she just she gets it and knows exactly what to say to express it perfectly. The essay was everything I imagined it would be. Forever grateful to that Destiel fanfic for introducing me to this.

Villette (4/5) (Dec 29) lovely

Girl, interrupted (5/5) (Dec 31) made me ponder about a lot of things. Her youth was really kind of stolen from her. Made to freeze just like that painting. what is the right thing to do? What is helping and what is hurting? What does “crazy” even mean? I think I tend to be very judgemental about this kind of stuff. But this book made me realize that people are people even if you do not understand why they act a certain way. They feel the same as me.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gloria (In Excelsis Deo)

Today is lesbian day, and so I've decided I will share my personal favourite lesbian song - Gloria (In Excelsis Deo) by Patti Smith.

Yes, it was written by a man, yes, Patti is not queer, and yes, I am aware that there is actual lesbian music out there.

But.

I was thirteen when I discovered Patti Smith, and when I was thirteen I had just started high school and had suddenly realised that there were more queer people in the world than I thought. Gloria is the first song on Horses, which I had read about and at some point was like 'hmm yeah I'll listen to that today' - and it was the most brilliant thing I had ever heard in my life. Horses is of course one of the best rock albums ever (in popular opinion, but Radio Ethipoia is my favourite), but not only was it everything I wanted to be - cool, effortlessly androgynous, full of references to literature, other songs, an art-punk masterwork - Gloria was a love song about another woman. She was singing about wanting another woman - something unparalleled in my 13 yr old experience of average sapphic YA books and a *certain* 2008 pop song (you know the one I mean).

Here was Patti Smith, androgynous, very very cool, looking defiantly from the cover of Horses, who I had been listening to for all of about two minutes before she declares her love for another woman in the sort of song which I had previously thought only men sung. It was 1975 when that came out - I heard that and assumed that she really was queer, just cos it would have taken a lot of balls to sing that on record, why would she sing it if she wasn't?

The song is of course a cover, written by a man, and Patti has said that when writing her songs she doesn't feel like a man or a woman, and that if women can be the muse for men, why can she not also use women as a muse? Interestingly PJ Harvey has said similar things about writing from a place beyond gender, and she has many sapphic songs and is also (as far as I'm aware) not queer.

I have since found both Patti songs that I like a lot more, and sapphic songs written by actual sapphics, but this initial act of revolution (in my worldview at least) altered my 13yr old existence on every plane. Patti was (and still is) my straight woman lesbian icon (along with the aforementioned PJ Harvey).

I listened to Gloria many many times, and it is easily still one of my favourite songs of hers, because of the impact of this initial experience, the first time I ever heard this is in a song, that reflected both who I was and who I wanted to be so clearly.

a couple actually sapphic artists for you -

Amy Ray (Indigo Girls)

Courtney Barnett (she's fantastic listen to her)

Kathleen Hanna (Bikini Kill)

Patty Schemel (drummer from Hole)

Ani Di Franco (actually haven't listened to her but I know she is)

Melissa Etheridge (my english teacher tells me to listen to her every year and I still haven't sorry Miss)

happy lesbian day to all my sister sapphics (inclusive of all) <3

#but seriously people there are so many sapphic songs written by straight women it's insane#they're mostly pretty good i'm not complaining though#lesbian#patti smith#pj harvey#indigo girls#courtney barnett#kathleen hanna#hole#gloria in excelsis deo#horses

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book 94 of 2023: Always Coming Home by Ursula K. LeGuin

“The difficulty of translation from a language that doesn’t yet exist is considerable, but there’s no need to exaggerate it. The past, after all, can be quite as obscure as the future. The ancient Chinese book called Tao teh ching has been translated into English dozens of times, and indeed the Chinese have to keep retranslating it into Chinese at every cycle of Cathay, but no translation can give us the book that Lao Tze (who may not have existed) wrote. All we have is the Tao teh ching that is here, now. And so with translations from a literature of the (or a) future. The fact that it hasn’t yet been written, the mere absence of a text to translate, doesn’t make all that much difference. What was and what may be lie, like children whose faces we cannot see, in the arms of silence. All we ever have is here, now.”

This is, of course, a masterwork. LeGuin has invented a future civilization that inhabits the Napa Valley, and this novel is a collection of stories, poems, and songs from this civilization. The culture she's created is heavily influenced by indigenous teachings, and I think by Buddhist philosophy as well. It's gorgeous and fascinating and kind of overwhelming and it just reaches into your brain and moves the furniture around in the gentlest possible way. Like: woah. I can't believe I hadn't read this before--I literally might get a tattoo of some of the spiral imagery. I mean, DAMN, Ursula. Holy SHIT.

What to read next: Braiding Sweetgrass, by Robin Wall Kimmerer, for another view of a life lived in harmony with the natural world.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ten Interesting Greek Novels

1. The Song of Achilles: A Novel by Madeline Miller

A tale of gods, kings, immortal fame, and the human heart, The Song of Achilles is a dazzling literary feat that brilliantly reimagines Homer’s enduring masterwork, The Iliad. An action-packed adventure, an epic love story, a marvelously conceived and executed page-turner, Miller’s monumental debut novel has already earned resounding acclaim from some of contemporary fiction’s brightest lights—and fans of Mary Renault, Bernard Cornwell, Steven Pressfield, and Colleen McCullough’s Masters of Rome series will delight in this unforgettable journey back to ancient Greece in the Age of Heroes.

“A captivating retelling of The Iliad and events leading up to it through the point of view of Patroclus: it’s a hard book to put down, and any classicist will be enthralled by her characterisation of the goddess Thetis, which carries the true savagery and chill of antiquity.” — Donna Tartt, The Times (Amazon.com)

2. Circe by Madeline Miller

In the house of Helios, god of the sun and mightiest of the Titans, a daughter is born. But Circe is a strange child--neither powerful like her father nor viciously alluring like her mother. Turning to the world of mortals for companionship, she discovers that she does possess power: the power of witchcraft, which can transform rivals into monsters and menace the gods themselves.

Threatened, Zeus banishes her to a deserted island, where she hones her occult craft, tames wild beasts, and crosses paths with many of the most famous figures in all of mythology, including the Minotaur, Daedalus and his doomed son Icarus, the murderous Medea, and, of course, wily Odysseus.

But there is danger, too, for a woman who stands alone, and Circe unwittingly draws the wrath of both men and gods, ultimately finding herself pitted against one of the most terrifying and vengeful of the Olympians. To protect what she loves most, Circe must summon all her strength and choose, once and for all, whether she belongs with the gods she is born from or with the mortals she has come to love. (Goodreads.com)

3. Zorba the Greek by Nikos Kazanzakis

First published in 1946, Zorba the Greek, is, on one hand, the story of a Greek working man named Zorba, a passionate lover of life, the unnamed narrator who he accompanies to Crete to work in a lignite mine, and the men and women of the town where they settle. On the other hand it is the story of God and man, The Devil and the Saints; the struggle of men to find their souls and purpose in life and it is about love, courage and faith. Zorba has been acclaimed as one of the truly memorable creations of literature—a character created on a huge scale in the tradition of Falstaff and Sancho Panza. His years have not dimmed the gusto and amazement with which he responds to all life offers him, whether he is working in the mine, confronting mad monks in a mountain monastery, embellishing the tales of his life or making love to avoid sin. Zorba’s life is rich with all the joys and sorrows that living brings and his example awakens in the narrator an understanding of the true meaning of humanity. This is one of the greatest life-affirming novels of our time. (Amazon.com) Part of the modern literary canon, Zorba the Greek, has achieved widespread international acclaim and recognition. This new edition translated, directly from Kazantzakis’s Greek original, is a more faithful rendition of his original language, ideas, and story, and presents Zorba as the author meant him to be. (Amazon.com)

4. The House on Paradise Street by Sofia Zinovieff

In 2008 Antigone Perifanis returns to her old family home in Athens after 60 years in exile. She has come to attend the funeral of her only son, Nikitas, who was born in prison, and whom she has not seen since she left him as a baby.

At the same time, Nikitas’s English widow Maud – disturbed by her husband’s strange behaviour in the days before his death – starts to investigate his complicated past. She soon finds herself reigniting a bitter family feud, and discovers a heartbreaking story of a young mother caught up in the political tides of the Greek Civil War, forced to make a terrible decision that will blight not only her life but that of future generations... (Amazon.com)

5. The Silence of the Girls: A Novel by Pat Barker

Here is the story of the Iliad as we’ve never heard it before: in the words of Briseis, Trojan queen and captive of Achilles. Given only a few words in Homer’s epic and largely erased by history, she is nonetheless a pivotal figure in the Trojan War. In these pages she comes fully to life: wry, watchful, forging connections among her fellow female prisoners even as she is caught between Greece’s two most powerful warriors. Her story pulls back the veil on the thousands of women who lived behind the scenes of the Greek army camp—concubines, nurses, prostitutes, the women who lay out the dead—as gods and mortals spar, and as a legendary war hurtles toward its inevitable conclusion. Brilliantly written, filled with moments of terror and beauty, The Silence of the Girls gives voice to an extraordinary woman—and makes an ancient story new again. (Amazon.com)

6. Ariadne by Jennifer Saint

Ariadne, Princess of Crete, grows up greeting the dawn from her beautiful dancing floor and listening to her nursemaid’s stories of gods and heroes. But beneath her golden palace echo the ever-present hoofbeats of her brother, the Minotaur, a monster who demands blood sacrifice. When Theseus, Prince of Athens, arrives to vanquish the beast, Ariadne sees in his green eyes not a threat but an escape. Defying the gods, betraying her family and country, and risking everything for love, Ariadne helps Theseus kill the Minotaur. But will Ariadne’s decision ensure her happy ending? And what of Phaedra, the beloved younger sister she leaves behind? (Amazon.com) Hypnotic, propulsive, and utterly transporting, Jennifer Saint's Ariadne forges a new epic, one that puts the forgotten women of Greek mythology back at the heart of the story, as they strive for a better world. (Amazon.com)

7. A Thousand Ships: A Novel by Natalie Haynes

This was never the story of one woman, or two. It was the story of them all . . .

In the middle of the night, a woman wakes to find her beloved city engulfed in flames. Ten seemingly endless years of conflict between the Greeks and the Trojans are over. Troy has fallen.

From the Trojan women whose fates now lie in the hands of the Greeks, to the Amazon princess who fought Achilles on their behalf, to Penelope awaiting the return of Odysseus, to the three goddesses whose feud started it all, these are the stories of the women whose lives, loves, and rivalries were forever altered by this long and tragic war.

A woman’s epic, powerfully imbued with new life, A Thousand Ships puts the women, girls and goddesses at the center of the Western world’s great tale ever told. (Amazon.com)

8. Elektra by Jennifer Saint

Three women, tangled in an ancient curse.

When Clytemnestra marries Agamemnon, she ignores the insidious whispers about his family line, the House of Atreus. But when, on the eve of the Trojan War, Agamemnon betrays Clytemnestra in the most unimaginable way, she must confront the curse that has long ravaged their family.

In Troy, Princess Cassandra has the gift of prophecy, but carries a curse of her own: no one will ever believe what she sees. When she is shown what will happen to her beloved city when Agamemnon and his army arrives, she is powerless to stop the tragedy from unfolding.

Elektra, Clytemnestra and Agamemnon’s youngest daughter, wants only for her beloved father to return home from war. But can she escape her family’s bloody history, or is her destiny bound by violence, too? (Amazon.com)

9. Clytemnestra: A Novel by Costanza Casati

As for queens, they are either hated or forgotten. She already knows which option suits her best…

You were born to a king, but you marry a tyrant. You stand by helplessly as he sacrifices your child to placate the gods. You watch him wage war on a foreign shore, and you comfort yourself with violent thoughts of your own. Because this was not the first offence against you. This was not the life you ever deserved. And this will not be your undoing. Slowly, you plot.

But when your husband returns in triumph, you become a woman with a choice.

Acceptance or vengeance, infamy follows both. So, you bide your time and force the gods' hands in the game of retribution. For you understood something long ago that the others never did.

If power isn't given to you, you have to take it for yourself.

A blazing novel set in the world of Ancient Greece, this is a thrilling tale of power and prophecies, of hatred, love, and of an unforgettable Queen who fiercely dealt out death to those who wronged her. (Amazon.com)

10. The Island by Victoria Hislop

On the brink of a life-changing decision, Alexis Fielding plans a trip to her mother’s childhood home in Plaka, Greece hoping to unravel Sofia’s hidden past. Given a letter to take to Sofia’s old friend, Fotini, Alexis is promised that through Fotini, she will learn more.

Arriving in Plaka, Alexis is astonished to see that it lies a stone’s throw from the tiny, deserted island of Spinalonga—Greece’s former leper colony. Fotini at last reveals the story that Sofia has buried all her life: the tale of her great-grandmother Eleni and her daughters, and a family rent by tragedy, war, and passion. Alexis discovers how intimately her family is connected with the island, and how secrecy holds them all in its powerful grip.

Atmospheric and captivating, The Island transports readers and keeps them gripped to the very last word. (Amazon.com)

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Claude Laydu and Jean Danet in Diary of a Country Priest (Robert Bresson, 1951)

Cast: Claude Laydu, Jean Riveyre, Adrien Borel, Rachel Bérandt, Nicole Maurey, Nicole Ladmiral, Martine Lemaire, Antoine Balpêtré, Jean Danet, Léon Arvel. Screenplay: Robert Bresson, based on a novel by Georges Bernanos. Cinematography: Léonce-Henri Burel. Art direction: Pierre Charbonnier. Film editing: Paulette Robert. Music: Jean-Jacques Grünenwald. The still above, of the young priest (Claude Laydu) happily accepting a ride on the back of a motorcycle from Olivier (Jean Danet) is not meant to be representative of the film as a whole. Quite the contrary, Olivier is a cousin of Chantal (Nicole Ladmiral), who, along with the rest of her family, has caused the priest much pain. Olivier is a soldier in the Foreign Legion, a character whose life is about as far from the priest's tormented spirituality as possible. The scene is a brief, liberated one, suggesting a world of potential other than that of the spiritual and physical suffering the priest has known in his assignment to the bleak and hostile parish of Ambricourt. The priest returns to his suffering after his motorcycle ride: He learns that he has terminal stomach cancer and dies in a slovenly apartment watched over by a former fellow seminarian, Fabregars (Léon Arvel), who is living with his mistress. As ascetic as the young priest has striven to be, he has to come to terms with a world that seems irrevocably fallen, even to the point of taking the last, absolving blessing from the lapsed Fabregars. Of all the celebrated masterworks of film, Bresson's Diary of a Country Priest may be the most uncompromising in making the case for cinema as an artistic medium on the same level as literature and music. In comparison, what is Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941) but a rather blobby melodrama about the rise and fall of a newspaper tycoon? Even the best of Alfred Hitchcock's oeuvre is little more than crafty embroidery on the thriller genre. The highest-praised directors, from Ford, Hawks, and Kurosawa to Godard, Kubrick, and Scorsese, never seem to stray far from the themes and tropes of popular culture. Even a film like Ozu's Tokyo Story (1953) falls back on sentiment as a way of engaging its audience. But Bresson strives for such a purity of character and narrative, down to the refusal to use well-known professional actors, and such a relentless intellectualizing, that you can't help comparing his film favorably to the great works of Flaubert or Dostoevsky. Having said that, I must admit that it's a work much easier to admire than to love, especially if, like me, you have no deep emotional or intellectual connection to religion -- or even an outright hostility to it. Does the suffering of the sickly young priest really result in the kind of transcendence the film posits? Are the questions of grace and redemption real, or merely the product of an ideology out of sync with actual human experience? What explains the hostility he encounters in the village he tries to serve: the work of the devil or just the bleakness of provincial existence? On the other hand, just asking those questions serves to point out how richly condensed is Bresson's drama of ideas. I love the movies I've alluded to above as somehow lacking in the intellectual seriousness of Bresson's film, but there's room in the pantheon for both kinds of film. Diary of a Country Priest remains for me one of film's great puzzles: What are we to make of the young priest's intellectualized faith? Is it a film for believers or for agnostics? In the end, these enigmas and ambiguities are integral to its greatness.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Explore Kata's Literary Journey on Amazon and BookBaby

Stories may influence attitudes, spark ideas, and motivate transformation. With Kata book on Amazon, readers can investigate an intriguing story of resilience, development, and discovery. Readers all around have been drawn to the Kata series because of its rich narrative and relevant subjects; it has become a treasure in the field of contemporary writing and narrative.

The Unique Appeal of BookBaby

Among the biggest online markets, Kata book on Amazon offers readers an easy approach to exploring its engaging story and rich characters. Amazon's platform guarantees that readers from all around the world may easily find and appreciate this amazing narrative. Amazon increases the availability of Kata by means of its dependable delivery system and easy-to-use interface, therefore enabling it to be a bestseller for readers of literature looking for meaningful labor.

The Unique Appeal of BookBaby

Apart from its Amazon presence, Kata book on BookBaby presents another reliable path for readers to feel its charm and depth. Book Baby is well-known for helping independent writers and offering excellent books for enthusiastic readers looking for uniqueness. Kata's availability on this platform emphasizes its appeal to a varied readership. It guarantees that readers looking for original literary treasures may quickly access it in their preferred format, therefore completing their reading trip.

Unveiling Kata’s Captivating Storyline

Kata book on Amazon has an engaging narrative that deftly combines vivid images with emotional depth and rich storytelling. Readers are pulled into Kata's path of overcoming obstacles, finding inner strength, and redefining what it means to flourish. The interesting story of the book and universal themes appeal to readers from many backgrounds. Kata has evolved into a must-read for everyone looking for significant, inspirational, and provocative narratives as it rises on Amazon's bestselling list.

Discovering Kata Through BookBaby

For readers who appreciate high-quality publishing and a curated selection, Kata book on BookBaby serves as a reliable source for discovering this literary masterpiece in its best form. BookBaby is the perfect venue for Kata's development and distribution because of its commitment to providing outstanding books. BookBaby provides a suitable home for the book's gripping narrative, so ensuring that readers who appreciate authenticity, originality, and depth in literature can find its artistic and narrative reach.

Kata: A Story Worth Exploring

Two outstanding approaches for readers to study this amazing and inspirational masterwork are provided by Kata book on Amazon and Kata book on BookBaby. Whether one prefers BookBaby's tailored approach or Amazon's broad reach, readers are assured of a unique literary experience that stays with them. Kata's narrative never fails to inspire and enthrall anybody who turns its pages, therefore highlighting the potency of excellent storytelling.

Conclusion

Visit katatheironthorn.com to learn further about Kata's inspirational narrative and its availability on these channels. This page offers an understanding of Kata's story, its ideas, and its cultural influence as well as its core. With its ageless and transforming message, Kata's path through Amazon and BookBaby guarantees its place as a beloved jewel in modern literature, captivating hearts and brains all around.

0 notes

Text

Price: [price_with_discount] (as of [price_update_date] - Details) [ad_1] About the Book A SCINTILLATING NEW TRANSLATION OF THE CLASSIC TAMIL NOVEL. Vallavarayan Vandiyadevan, a scion of the Vaanar clan, sets out across the Chozha land to deliver a secret message from Crown Prince Aditya Karikalan. Does he manage to safely deliver this message? Or does he get trapped in the sinister royal conspiracy that he unwittingly uncovers on his journey? When Ponniyin Selvan was first serialised in Kalki, no one could have imagined the impact it would have on the circulation of the magazine. Nor that, years later, this Tamil magnum opus, which blends travelogue with history and Chozha myth-making, would lend itself to the big screen, its cinematic form shaped by one of the finest directors of our time. The novel invented a distinct style, in which slang alternates with erudition, wordplay with euphoric prose and vivid imagery—a style that critics came to call ‘Kalki Tamil’. Today, this pioneering work is considered one of the great classics of Tamil literature. This unabridged and first-rate translation of Kalki Krishnamurthy’s masterwork by Nandini Krishnan is at once faithful to the original and accessible to the readers of this day. Carefully crafted in lyrical prose, First Flood—Book One in the Ponniyin Selvan series—is the quintessential page-turner: full of adventure, intrigue, conspiracy and romance. About the Author ‘Kalki’ is the pen name of Ramaswamy Krishnamurthy (1899-1954), whose career in writing and journalism began as activism during the struggle for Indian independence. He served as editor of the popular Tamil magazine Ananda Vikatan before launching Kalki. The magazine—and eventually its founder—was named for the mythological tenth avatar of Vishnu to symbolise a vision to ‘destroy regressive regimes, express radical thoughts, take readers into new directions, and create a new era’. Kalki wrote several novels, including Parthiban Kanavu and Sivakamiyin Sabadam, as well as political essays, film reviews, dance and music critiques and scholarly work. About the Translator Nandini Krishnan is the author of Hitched: The Modern Woman and Arranged Marriage and Invisible Men: Inside India’s Transmasculine Networks. She has translated two of Perumal Murugan’s works into English: Estuary and Four Strokes of Luck. She was shortlisted for the PEN Presents translation prize 2022 and the Ali Jawad Zaidi Memorial Prize for translation from Urdu 2022. She is an alumna of the Writer’s Bloc playwrights’ workshop by the Royal Court Theatre, London. Her novel-in-manuscript was a winner of the Caravan Writers of India Festival contest and showcased at the Writers of the World Festival, Paris, 2014. From the Publisher

Add to Cart Add to Cart Customer Reviews 4.6 out of 5 stars 32 4.7 out of 5 stars 15 Price ₹288.00₹288.00 ₹249.00₹249.00 Ponniyin Selvan - Book 1 Ponniyin Selvan - Book 2 Publisher : Eka (24 April 2023); Westland Books A Division of Nasadiya Technologies Pvt ltd Language : English Paperback : 290 pages ISBN-10 : 9357762825 ISBN-13 : 978-9357762823 Reading age : 18 years and up Item Weight : 380 g Dimensions : 13 x 2 x 20 cm Country of Origin : India Net Quantity : 1 Count Packer : Westland Books A Division of Nasadiya Technologies Pvt ltd Generic Name : Book [ad_2]

0 notes

Note

This is all really interesting analysis (which really makes me want to read the original Dragonball series again!) and I'm sure it helped the OP a lot! ...But as a librarian I have a VERY STRONG URGE to not let this particular question go past my dash without posting at least a FEW actual, specific, secondary sources, which seems like it was the original intent of the question.

I did a quick Google Scholar search for "'journey to the west' influence modern" and that turned up quite a few scholarly papers, but most of them weren't actually about modern culture and storytelling, so I also tried some variations like "'journey to the west' influence folklore" and "'journey to the west' influence mythology'". Between those 3 searches (which took like 15 minutes overall), here's the top 5 most promising papers I found that seemed like they would be helpful to a world mythology student:

Even if you don't find all of these helpful, you can get a lot of mileage out of just looking through their bibliographic citations, their "literature review" sections (if they have them), and also searching online for other papers that have bibliographic citations OF them! Also, keep in mind that I'm just using Google Scholar here because it's quick and generic; your local educational institution almost certainly can give you access to way more sources than this. And they also probably have IRL reference librarians can give you more in-depth help and specific recommendations!

hi red!! i'm doing an analysis of sun wukong's (and journey to the west in general's) impact on modern culture for my world mythology final, and for some reason i'm having a hard time finding sources. is there anything you can recommend?

The fact that Journey to the West has contributed an enormous number of tropes to modern media is very clear when the media in question is examined, but I don't know of a specific secondary source that's already done that analysis for you. However, this IS a very good excuse for you to plow through a metric buttload of shonen manga, since the lineage is basically Sun Wukong -> Son Goku -> like a solid third of all shonen action heroes written in the last forty years.

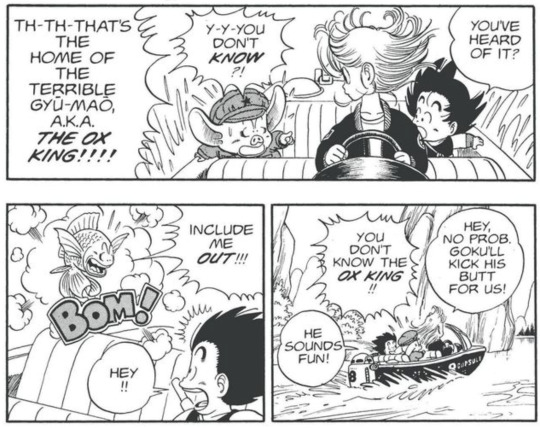

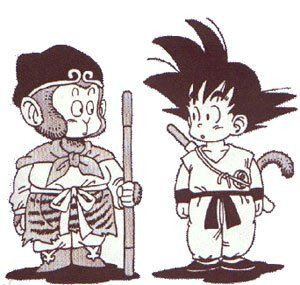

Dragon Ball kicks things off:

Started in 1984 and almost unquestionably the most influential manga ever made. Its first arc features the weird super-strong monkey-kid Son Goku - which is just the japanese pronunciation of the characters of Sun Wukong's name - meeting up with a wacky crew of thinly-veiled expys of the Journey to the West crew, with teen inventor Bulma filling the role of Tripitaka, Oolong the pig-man filling Zhu Bajie's role and Yamcha the desert-based bandit as Sha Wujing.

Hijinks ensue, and while the story drifts pretty far from Journey to the West's original plot, it actually stays pretty solidly referential in weirdly unexpected ways. Several the villains of the week are JttW references, and even the later appearance of three more Saiyans lines up with the surprise reveal of three more Wukong-like mystical apes in the original story.

The connection between Dragon Ball and JttW is very unsubtle and a frequent reference in the chapter covers and supplemental art.

Not every subsequent JttW reference is the result of Dragon Ball popularizing it or anything, since it was already enormously popular, but I think it's pretty hard to extricate Dragon Ball's influence on anime and manga from the original influence of Journey to the West itself.

One way that a distinction can be drawn is in the differences in characterization between Goku and Sun Wukong himself. A lot of the next generation of shonen protagonists were kind of Goku-alikes - pure-hearted dumbasses who only care for the three Fs: Food, Fighting and Friendship.

But the original characterization of Sun Wukong is not really all that similar. He's a trickster, sure, but he's far from a young, friendship-motivated goober. He's profoundly intelligent, pretty much the most well-educated entity on the planet, and routinely brings up that he's centuries older than most of his peers. The Goku-alikes from the later decades of shonen anime are tellingly far-removed from that original characterization. So you get characters based on Goku's cheerful idiocy, but it's just a small subset of the broader influence of Journey to the West on the space of literature.

In general, Journey to the West frequently shows up in very small, bite-sized tropes in other stories. It's less "this is wholly based on Journey to the West" and more "oh, I know where they maybe got this idea/aesthetic/power/weapon/villain of the week from." There are way too many to list, but some of the ones that tend to jump out at me are-

Sneaky characters with monkey motifs:

Tricksy, highly mobile characters who fight with a staff:

Characters afflicted with a magical restraint artifact that allows a much weaker character to stop them from misbehaving:

Specific esoteric weapons, eg. magical fans, rakes, gourds, namedropping The Sword of Seven Stars, etc.

Villains with prominent ox or pig design motifs:

Characters whose primary combat strat is just making Shitloads Of Disposable Copies Of Themselves:

Honestly it just keeps going like this. It's kinda everywhere. Finding the JttW in things is my favorite conspiracy theory rabbit hole because it's 100% harmless and more often than not completely correct.

#reference#world mythology#journey to the west#sun wukong#“I'm having trouble finding sources” is like a summoning call for librarians of all stripes#so I cannot be blamed for suddenly trying to answer this question which absolutely was not directed at me#librarians

679 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hard To Be a God by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky

Gautam Bhatia

"You shouldn't have come down from the sky." (p. 217)

In his introduction to Danilo Kis's A Tomb for Boris Davidovich, a collection of chilling stories about the individual's mental and moral degradation under Stalinism, Joseph Brodsky writes:

"By virtue of his place and time alone, Danilo Kis is able to avoid the faults of urgency which considerably marred the works of his listed and unlisted predecessors [such as Arthur Koestler]. Unlike them, he can afford to treat tragedy as a genre, and his art is more devastating than statistics." (A Tomb for Boris Davidovich, p. xi)

For Brodsky, it would seem, distance is essential in order to effectively sublimate tragedy into art—distance of time and of place, which provides the necessary creative sanctuary that a writer needs.

But for Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, who lived and worked in the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War, neither kind of distance could be possible. It was, instead, their choice of genre that allowed them the "ironic detachment" that Brodsky thought necessary to transform statistics into literature. In a series of novels, set in the "Noon Universe," the Strugatskys imagined a future in which the Marxist theory of history had been vindicated, a classless utopia established, and humans were now a space-faring species in a peaceful galaxy. By exploring the dysfunctions of that world, the Strugatskys were able to create a subversive literature that escaped the censor's knife.

One of the central novels in the Noon Universe is Hard To Be a God (1964), which for the last fifty years has only been available in a double translation—from Russian to English via German. This deficiency has finally been remedied. In April 2015, Gollancz brought out a new translation, by Olena Bormashenko, as part of their SF Masterworks Series. The translation features an afterword by Boris Strugatsky in which he writes that the original plan for Hard To Be a God was that of a "fun story in the spirit of The Three Musketeers" (p. 244). But in 1963, when the Soviet Writers' Union was caught up in a wave of puritan-nationalistic fervour, a backlash against the thaw of the Khrushchev years, the Strugatskys realized that "the time of 'light things,' the time of 'swords and cardinals' seemed to have passed . . . the adventure story had to, was obliged to, become a story about the fate of the intelligentsia, submerged in the twilight of the Middle Ages" (p. 244).

The fault of urgency. Brodsky would have raised his eyebrows. And indeed, the plot of Hard To Be a God suggests all the pitfalls of allegory. An unnamed planet in the Noon Universe has not yet progressed beyond the Middle Ages. Anton is one among fifty "operatives" sent by Earth to implant themselves into the society and culture of that world. The operatives are commanded to be non-interventionist gods; while they take the roles of nobles and barons in the various petty realms and kingdoms, they may only observe. Despite their ability to wield the powers of a civilisation a millennium ahead, they are forbidden from interfering with the natural progress of history. "Natural," that is, according to the "basis theory" (which, although never explicitly stated, is the Marxist materialist conception of history), which—as the book's characters repeat almost like a litany—postulates the inevitable progress from feudalism to monarchic absolutism, to capitalism, and ultimately, the communist utopia. The pain and violence of feudalism must be suffered by its inhabitants, in order to pave the necessary way to utopia. Any intervention, no matter how benevolent the aim, would be a disastrous disruption. "We're gods here, Anton, and we need to be wiser than the gods from the legends the locals have created in their image and likeness as best as they could" (p. 39).

But then Anton's realm gradually begins to descend into a seemingly unscripted orgy of violence, directed primarily against writers, artists, and historians; and when Don Reba, a leader with distinctly fascist tendencies draws ever closer to absolute power, Anton begins to feel the conflict between the postulates of the basis theory, and his own instincts to intervene as his conscience dictates. As each episode casts a further strain upon his ability to endure inaction, Anton begins to understand how hard it is to be a god.

Although Hard To Be a God was written four years before Soviet tanks rolled into Prague to "correct" the natural progression of history, the allegory is unmistakable. But perhaps what saves the novel from remaining just that is that the parallels are not limited to one historical situation. Within the genre, the theme itself is a familiar one (although the Strugatskys probably got to it first). As Ken Macleod points out in his Introduction, the Noon Universe "anticipates Star Trek and Iain M. Banks' Culture novels" (p. vi). And the way the Strugatskys write, the book could just as well be a wry take on contemporary debates around humanitarian intervention and the responsibility to protect, or a critique of colonialism's "civilizing mission." Like Coetzee's Waiting for the Barbarians, it could be located in any time, any place, and in the history of any culture. And because it could be everything and nothing, it becomes easier to read Hard To Be a God as a good science fiction yarn than an unsubtle critique of Soviet hubris.

Stalinist totalitarianism's sacrifice of individual freedom and autonomy to the iron constraints of the march towards an illusory utopia has served as the political backdrop for a number of science-fiction novels—from Yevgeny Zamyatin's We, written in the earliest years of the Soviet Union, to Orwell's 1984. What is unique about the setting of Hard To Be a God is that the internal destruction of individual freedom under Stalinism is transformed into an external set of constraints that are ultimately as morally destructive. Every time Anton is driven to act by a particularly egregious instance of violence, the "basis theory" stays his hand, causing ever-deepening crises of conscience. "I don't like that we've tied our hands and feet with the very formulation of the problem," he protests to his superior, at one stage. "I don't like that it's called the Problem of Nonviolent Impact. Because under my conditions, that means a scientifically justified inaction. I'm aware of all your objections!" (p. 37) Alexander Vasielivich's answer is simple: "Don't abuse terminology, Anton! Terminological confusion brings about dangerous consequences" (p. 40).

The primacy of terminology, the unwavering belief that history is—literally—universal, and that local situations must be interpreted to distortion, as long as they can fit within an a priori vision of historical progress, "developed in quiet offices and laboratories" (p. 45), immobilises Anton in another way: by cauterizing his very human tendencies towards moral judgment and the attribution of responsibility. In Broken April, the Albanian novelist Ismail Kadare describes the tribal law of the blood feud, the Kanun, thus: "Like all great things, the Kanun is beyond good and evil" (Broken April, p. 73). Broken April is a story about how the impersonal, amoral Kanun, which prescribes an endless cycle of revenge and counter-revenge for a crime committed time out of mind, absolves the characters of the burdens of choice, and the burdens of judging and being judged for those choices. But in Hard To Be a God, while the inevitability of the basis theory absolves Don Reba and his marauding soldiers of culpability, it casts an even more excruciating burden of choice upon Anton. "Grit your teeth," he tells himself, "and remember that you're a god in disguise, they know not what they do, almost none of them are to blame, and therefore you must be patient and tolerant" (p. 45). He is not convinced by that excuse, and neither are we.

The hubris of attempting to subject an aggregate of unpredictable, individual human actions into an iron law of historic inevitability is not new to science fiction. In Asimov's Foundation series, the scientist Hari Seldon invents the science of "psychohistory," which is predicated upon the assumption that group behaviour is as predictable and as exact as a "science." Of course, science is never predictable; and psychohistory meets (at least a temporary) failure in the shape of "The Mule," a mutant whose powers range beyond what Seldon could have imagined. When it comes to human beings, Asimov seems to be telling us, no law of necessity can ever truly account for individual variation. In a strikingly similar thought, Anton observes that "basis theory only concretely specifies the psychological motivations of the principal personality types, but there are in fact as many types as there are people; any sort of person could come to power" (p. 85). As his colleagues try—in increasingly strained ways—to fit Don Reba into a mould, into "the ranks of Richelieu, Necker, Tokugawa Ieyasu and Monck" (p. 220), Anton's suspicion grows that Reba's "psychological motivations" simply fall outside the scope of the theory. And if that is true, and as an apocalypse seems to be drawing even closer while Earth's operatives continue to theorise and temporise, will the theory's mandate of non-interference continue to hold?

As with other Strugatsky novels, that question is not answered until the very end of the book. The issue remains poised on the edge of a needle, and when we put the book down, it is simply impossible to judge which way it ought to have been decided. Like all the best science fiction, Hard To Be a God asks the most discomforting of questions, and denies us the comfort of a resolution.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Book Review: From Heaven He Came and Sought Her

How does the doctrine of definite atonement impact pastors and preachers today? From Heaven He Came and Sought Her is a comprehensive resource on definite atonement as it examines the issue from historical, biblical, theological, and pastoral perspectives. Edited by David Gibson and Jonathan Gibson, with a foreword by J. I. Packer, this 700-page book is a masterwork. Effective, Effectual, and Empowering

David Gibson and Jonathan Gibson begin the book. The doctrine of definite atonement is defined as the death of Christ intending to win the salvation of God’s people alone. This book champions the doctrine of definite atonement as the heart of the meaning of the cross. It addresses history, the Bible, theology, and pastoral practice in light of the doctrine of definite atonement and how it can be best articulated today.

Paul Helm’s chapter on Calvin, indefinite language, and definite atonement was especially enlightening to me as a preacher. He explained how because the preacher is ignorant of who is and who is not elected, the preacher may call men and women to Christ in universal or unrestricted terms. I can emphasize both the effective and intentional nature of Christ's sacrifice for believers. This was empowering to me as I call people to repentance and to Christ in my sermons.

The Suffering Servant and the Savior of the World