#marshall pétain

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Marshall Pétain, Foch and Joffre on the 1919 Victory Parade in Paris

French vintage postcard

#postal#sepia#marshall pétain#victory#ephemera#briefkaart#ptain#joffre#french#parade#photo#photography#historic#postcard#marshall#paris#vintage#foch#postkaart#tarjeta#carte postale#postkarte#1919#ansichtskarte

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

2023's Best Books

I meant to do this a few days ago so there was more time before the holidays, but here's a quick list of the best books that I read that were released in 2023. Obviously, I didn't read every book that came out this year, and I'm only listing the best books I read that were actually released in the 2023 calendar year.

In my opinion, the two very best books released in 2023 were An Ordinary Man: The Surprising Life and Historic Presidency of Gerald R. Ford by Richard Norton Smith (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO), and True West: Sam Shepard's Life, Work, and Times by Robert Greenfield (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO).

(The rest of this list is in no particular order)

President Garfield: From Radical to Unifier C.W. Goodyear (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

The World: A Family History of Humanity Simon Sebag Montefiore (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

France On Trial: The Case of Marshal Pétain Julian Jackson (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

The Last Island: Discovery, Defiance, and the Most Elusive Tribe on Earth Adam Goodheart (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

Emperor of Rome: Ruling the Ancient Roman World Mary Beard (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

City of Echoes: A New History of Rome, Its Popes, and Its People Jessica Wärnberg (BOOK | KINDLE)

We Are Your Soldiers: How Gamal Abdel Nasser Remade the Arab World Alex Rowell (BOOK | KINDLE)

Edison's Ghosts: The Untold Weirdness of History's Greatest Geniuses Katie Spalding (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

Waco Rising: David Koresh, the FBI, and the Birth of America's Modern Militias Kevin Cook (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

The Summer of 1876: Outlaws, Lawmen, and Legends in the Season That Defined the American West Chris Wimmer (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

King: A Life Jonathan Eig (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

LBJ's America: The Life and Legacies of Lyndon Baines Johnson Edited by Mark Atwood Lawrence and Mark K. Updegrove (BOOK | KINDLE)

Who Believes Is Not Alone: My Life Beside Benedict XVI Georg Gänswein with Saverio Gaeta (BOOK | KINDLE)

Eighteen Days in October: The Yom Kippur War and How It Created the Modern Middle East Uri Kaufman (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

The Rough Rider and the Professor: Theodore Roosevelt, Henry Cabot Lodge, and the Friendship That Changed American History Laurence Jurdem (BOOK | KINDLE)

White House Wild Child: How Alice Roosevelt Broke All the Rules and Won the Heart of America Shelley Fraser Mickle (BOOK | KINDLE)

Romney: A Reckoning McKay Coppins (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

Founding Partisans: Hamilton, Madison, Jefferson, Adams and the Brawling Birth of American Politics H.W. Brands (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

The Earth Transformed: An Untold History Peter Frankopan (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

LeBron Jeff Benedict (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

Ringmaster: Vince McMahon and the Unmaking of America Abraham Riesman (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

The Fight of His Life: Inside Joe Biden's White House Chris Whipple (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

#Books#Book Suggestions#Book Recommendations#Best Books of 2023#Best of 2023#An Ordinary Man#President Ford#Richard Norton Smith#True West#Sam Shepard#Robert Greenfield#President Garfield#C.W. Goodyear#The World#Simon Sebag Montefiore#France On Trial#Marshal Pétain#Julian Jackson#The Last Island#Adam Goodheart#Emperor of Rome#Mary Beard#City of Echoes#Jessica Wärnberg#We Are Your Soldiers#Gamel Abdel Nasser#Alex Rowell#Edison's Ghosts#Katie Spalding#Waco Rising

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The ideological climate of the defeat of 1940 and the establishment of the French State are related in many aspects to the climate that developed in reaction to Sedan and during the years that followed the defeat of the Paris Commune. For writers close to the National Revolution, the Commune was viewed in the same way as the Popular Front. A propaganda journal published by the new regime stated:

It is a constant law of history that defeats result in revolutions. The French had not forgotten the bloody disturbances of the commune of 1871… . France was going to add even more misfortune to those that already overwhelmed it. It was to be feared that, following the bent to which odious propaganda had accustomed them, minds would turn toward a bloody, fratricidal fight. . . . The Marshal’s government successfully confronted and dealt with this danger. Without any-movement, without one cry of dissension, the political revolution was brought about.

Henri Massis, the officer responsible for press relations to General Huntziger at the time, stated plainly that the first news of the armistice had evoked the memory of 1871 and the fear of a new Commune. Thus, the primary task of the armistice army was to maintain order. The defeat would appear to many intellectuals as the final blow to 'French decadence.’ The themes of national decline, collective fault, and biological and political sins echoed one another in an obsessive litany during the period following June 1940, just as during the 1870s. Maurras even suggested anthologizing Renan’s La Reforme intellectuelle et morale, which he felt might render “a great service to the French people of 1940, since those of 1870 failed to take proper note of it.” The precepts and maxims of the Marshal—the “guide in possession of incomparable and almost superhuman wisdom and intellectual control” — functioned like calls to self-flagellation, and many would lend their skills to an attempt at exegesis. Georges Bernanos offered a gripping expression of the political bases and effects of the encounter between the message of the defeat, spoken by the prophet, and the “expectation” of those who saw the National Revolution as a national opportunity:

All that is called the Right, which ranges from the self-styled monarchists of the Action francaise to the self-styled national socialist radicals and includes big industry, big business, the high clergy, the Academies, and the officers’ staff spontaneously united and cohered around the disaster of my country like a swarm of bees around their queen. I am not saying that they deliberately wished the disaster. They were waiting for it. This monstrous anticipation passes judgment on them.

- Francine Muel-Dreyfus, Vichy and the Eternal Feminine: A Contribution to a Political Sociology of Gender. Translated by Kathleen A. Johnson. Durham: Duke University Press, 2001. p. 15-16.

#révolution nationale#régime de vichy#vichy france#reactionary politics#paris commune#action francaise#marshal pétain#georges bernanos#renan#occupied france#world war ii#academic quote#histoire de france#reading 2024#disaster politics#popular front#front populaire

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“If any of us thought we could do our fellow creatures good by committing or, more probably, condoning an evil act, would we do so? Would we even recognize the moment when it happened, or accept that it was evil? Most of us are wonderfully good at persuading ourselves that our actions are pure. Does treason actually exist or, as Talleyrand quipped, is it just a matter of dates? Worse, is it a process of human sacrifice, in which exposed individuals are singled out to pay for the sins of thousands—who escape punishment? Switch allegiance at the right moment, or die opportunely, and you may be spared centuries of shame. Live too long, or cling to the wrong raft and your name will be a byword and a hissing. I suspect that Talleyrand, living in a wittier and less dogmatic age, might have reflected that Marshal Philippe Pétain was just unfortunate in his timing.

From this perspective, Pétain’s mistake was to carry on living after the fall of his Vichy State during the last grisly months of the Third Reich. If he had managed to die (he was after all 88) then he would have escaped much humiliation. If he had been shot out of hand by French resisters, a lot of scores would have been neatly settled. (Winston Churchill thought this would have been a much better way of dealing with the actual Nazi leadership than the dubious Nuremberg trials with their Soviet prosecutor). But, as Julian Jackson recounts in his book about Pétain’s surrender, trial, condemnation, and lifelong imprisonment, the old soldier more or less sought out his fate. The Germans had carried him off to the Reich. But Pétain found his way back to France, so compelling De Gaulle and his provisional government to put him on trial for treason. To do so, it had to reopen the whole bitter period, in which many apart from Pétain had behaved weakly, or dishonorably, or just mistakenly. As the title of this book reminds us, France was on trial alongside Pétain.

(…)

The shepherd, the argument runs, is supposed to stay and tend his sheep when the danger is at its worst, not to flee abroad—even if he eventually returns triumphant. Did Pétain perhaps stand between the French people and the full wrath of their conquerors? He may have thought so, at least to begin with. And when he spoke of “collaboration” with Hitler, the word did not seem to mean what it later came to mean.

But, as it happened, Pétain did not stand between the French people and their Nazi occupiers. He became their all-too-willing servant. We now know beyond doubt that Marshal Pétain’s Vichy state enthusiastically offered collaboration to the Nazis, so much so that the Germans actually rebuffed it. It had even suggested its own persecution of the Jews, rather than reluctantly given in to German pressure. In 1972 an American historian, Robert Paxton, obtained German documents on the Occupation which left no doubt about this. Pétain’s supposed “National Revolution” closely collaborated with the fiends and demons of the Third Reich and vigorously urged on one of its ugliest policies. Anybody who has any serious interest in Pétain now knows all this.

But they did not know it when it mattered most, when Pétain and France were on trial in 1945, or for some time afterwards. In fact, Pétain died in custody in 1951 before the facts were wholly known. Jackson’s book on the French state’s 1945 prosecution of Pétain contains a lengthy passage on Paxton’s discoveries. But it rightly leaves them until long after this extraordinary process was over and the Marshal slept with his fathers. So Jackson is able to treat seriously several French citizens, lay jurors, journalists, politicians—and Pétain’s brilliant, dangerous and inconvenient lawyer, Jacques Isorni. All these were determined to give the old man some semblance of fairness, at a time when violent hysteria would have been quite possible instead. Remember, it was not long since the repellent and chaotic epuration (purge) of actual and alleged collaborators after the German defeat in which wild, violent street “justice” was imposed on some of those believed to have been too helpful or friendly to the occupying power, especially the public shaving of women’s heads, not a brave action whatever else it was. France’s Communists, in particular, were keen to condemn the conservative Catholic Pétain as a national traitor comparable to the reviled Marshal Bazaine of the Franco-Prussian war. They published propaganda showing him dangling at the end of a hangman’s rope and urged the imposition of the death penalty.

(…)

It was not just Denmark where this sort of thing happened. British sneering at the weakness and cowardice of continentals under the jackboot is also badly shown up by the curious, embarrassing and largely-forgotten German occupation of the British Channel Islands in 1940. “But what would you have done?” the islanders ask their mainland critics, to this day. The islands’ local authorities were cut off from the British constitution and government when Churchill brusquely abandoned them as indefensible after Dunkirk. Suddenly these largely conservative gentlemen, some nearly as elderly as Pétain, found themselves implementing the decrees of the Third Reich rather than those of His Majesty the King. They felt they had little choice but to work with the German occupiers. Where can a resistance movement hide on a tiny island?

But compromise leads to compromise and to worse compromise. Some of their leading officials ended up cooperating in terrible acts, such as the deportation of local Jews to Auschwitz. Those who survived this distressing period are understandably angry about criticism from safe mainlanders who never saw a German soldier on their streets. When the author Madeleine Bunting wrote a severe account of the islands’ subjugation, The Model Occupation, she met much resentment from those who had experienced it. But I wish this story was better known so that boastful and ignorant British people would stop mocking the supposedly cowardly French for their collaboration in the Vichy period. The fate of the islanders suggests that it would have been the same for the British, if Hitler had ever got ashore.

(…)

Despite the French Communists’ righteous wrath at Pétain, they had their own highly embarrassing secrets from the era. This is hugely significant because of the undoubted (and gravely mistaken) attraction of the Pétain regime for French conservatives and Catholics. His national motto of Travail, Famille, Patrie, replacing the Republican Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite, made it plain that this was not just a necessary co-operation with a new master, but an attempt to overturn many of the principles of the French Revolution. To this day, some figures on the political right in France seek to defend Pétain, the most recent being the failed presidential candidate Eric Zemmour, who most unwisely and inaccurately sought to defend Vichy’s policy, for supposedly saving French Jews by sacrificing recently arrived Jewish refugees to the Nazis. Why would anyone bother to do this? Could it be because of an actual lingering sympathy with Pétain’s social policies?

The Communist attempts at collaboration with the Germans were (like Vichy’s active anti-Jewish behavior) not widely known at the time of Pétain’s trial. Julian Jackson discussed the Communist approach to the German occupation authorities in another work on France’s occupation period France: The Dark Years 1940-44. For many years after the war the episode was little more than a bitter Trotskyist rumour, but it has now taken solid form in serious research. To even begin to comprehend it you must recall that in May 1940, as France’s democratic government collapsed and Nazi power swept into Paris, the Nazis and the Communists were allies against the democracies, thanks to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939, which would endure until June 1941 and was far more than a brief flirtation. The previous September, there had been a joint Wehrmacht and Red Army victory parade over Poland in the city of Brest-Litovsk (pictures still exist of German and Soviet officers happily communing as they take the salute). Not long afterward the two worst secret police forces in the world, Hitler’s Gestapo and Stalin’s NKVD, exchanged prisoners, as each wanted to get their hands on persons the other had arrested. Much of the fuel and material used in the German Blitzkrieg against the European democracies in May 1940 had come from or through the USSR.

The French Communist Party was therefore considered a pro-enemy body by the French state. It was banned and its daily newspaper L’Humanite shut down. The French Communists brushed aside rumors of their behavior for long after the war, and their considerable power and popularity in Gaullist France allowed them to get away with doing so. But scholarship has now caught up with them. Beyond doubt, French Communists went voluntarily to the Nazis and sought permission for the re-issue of their newspaper. Apparently the Comintern, then the central headquarters of all Communist Parties, was taken by surprise by the French defeat in 1940. It did not know how to respond. The leaders of French Communism had been dispersed by the proscription of their Party, and were in hiding or abroad. But some heavyweight commissars, Jacques Duclos, Jean Catelas, and Maurice Treand, wondered if the fall of the French state might be a chance to recover their organization’s lost influence. This was in the Leninist tradition of ruthlessness and of scorn for patriotism and other such bourgeois notions.

The negotiations involved the subtle French-speaking Otto Abetz, Germany’s future ambassador to Vichy France. Treand and Catelas promised, Jackson writes, that if allowed to reappear, the Communist daily would “pursue a policy of European pacification” and “denounce the activities of the agents of British imperialism.” Underground editions of the paper (secretly printed since September 1939) published three articles in the summer of 1940 praising fraternization between French workers and the Germans. Perhaps these were aimed at persuading the Germans to allow open publication. Who can now say?

As so often in history with things that nearly happened, it is like watching a ghost begin to appear, and then disappear again. There was surprising sympathy for collaboration on both sides in France. Some conservatives loathed England, hoped for a British surrender, and thought Hitler was better than socialism. Some Communists suspected that Hitler might be kinder to them than democracy had been. Only as the occupation hardened, and as the French Communist leader in exile, Maurice Thorez, reasserted control, did the Communists end the talks. They did so very shortly before the Germans also went off the idea, though it was a close-run thing. One Communist, Robert Foissin, was made an internal scapegoat by the Party—which belatedly realized how embarrassing the talks would one day become. But Duclos was too important for such treatment. He would live to be the Communist candidate for the Presidency of France in 1969. No wonder that in 1945 the Communists—now covered in glory because of their post-1941 Resistance role—wanted to draw eyes away from their own behavior in 1940, and concentrate instead on the wickedness of the Catholic, conservative Pétain.

(…)

In truth, France was on trial in 1945 more than Pétain. And France emerges from the trial with perhaps a little more credit than we give it. This at least was not a howling enraged tribunal, as the Communists might have desired, but a genuine attempt to apply due process and so to restore some sort of legitimate stability. De Gaulle’s view of the old man was that he was a living corpse who had died to all intents and purposes in 1924. Probably those in French politics who (perhaps too willingly) let him take responsibility for making peace with Germany had a similar view. He was a cypher, not a person. Those who seriously imagined that he was the head of a conservative national revolution were deluded at the time, and those in modern French politics who suggest the same are equally deceived, though it now seems fairly certain that the Marshal was, more often than not, conscious of what was going on around him and aware of what was done in his name. His reprieve from execution was not only a recognition that he was too old to face a firing squad. It was a humane compromise between the De Gaulle and Pétain factions which still haunt French public life in surprising ways. After all, the Socialist President Francois Mitterrand served and was honored by the Vichy regime, yet lived to prosper. The far more brutal fate of Pétain’s colleague Pierre Laval, shot after a brief and undignified hearing and a botched suicide, probably satisfied the general desire to erase the shame and discomfort of the collaboration years which Mauriac had identified. How pleased any reader of this book must be that he and his country did not undergo such misery. Do not be defeated in war. Defeat corrupts the defeated, and it is far harder than we think to stand above the grim process. Pray that it never happens to you.”

“One of the greatest challenges human beings face is how to tease apart a bad act from a good character — or, conversely, a toxic personality from the good and worthy things he created. How do we separate the long-time childhood friend from his insane Facebook polemics? The good neighbour from his bad politics?

“People are thoughtless all the time,” writes Alexandra Hudson in her new book, The Soul of Civility, while arguing that the best way to depolarise our society is to recognise that good people can have bad ideas. This idea is classically Christian, but also fundamentally American: even after the Civil War, a central tenet of Reconstruction was that those who fought for the Confederacy should be given grace for having chosen the wrong side. But that’s a principle it’s easier to hold to in the wake of victory than in the fog of war — or, as this past week’s events have reminded us, War Discourse.

The response from certain corners of the progressive Left to the stories coming out of Israel has been extraordinary. The silhouette of a paragliding Hamas militant has been adopted by groups ranging from Black Lives Matter to the Democratic Socialists of America — a graphic successor to that Che Guevara block print that used to hang on every dorm room wall. A crowd on the steps of the Sydney Opera House in Australia chanted “gas the Jews”. A cheer went up in Times Square at the news that 700 Israelis had been killed. And among the academic and media classes, a series of statements ran the gamut from half-hearted condemnations of the terrorist attacks to triumphant and bloodthirsty snarling.

“What did y’all think decolonization meant? vibes? papers? essays? losers,” wrote Najma Sharif, a writer for Soho House magazine and Teen Vogue. “Today should be a day of celebration for supporters of democracy and human rights worldwide,” tweeted Rivkah Brown of Novara Media. The language varied, but the sentiment was the same: this is good, actually, and seeing it should fill you with the same cathartic glee as any underdog story. Don’t you see? This isn’t terrorism; it is justice.

(…)

The war in Israel, and the one in Ukraine: it’s not hard to see how our distance from these events, combined with the immediacy of so much coverage and conversation about them, lends itself to the most grotesque kind of rubbernecking. It’s war as spectator sport; people haggle over the reports of Hamas beheading babies with the same energy as a group of armchair referees debating an off-side call.

Some people, anyway. The term “luxury beliefs” was coined to describe how privileged progressives like to traffic in this sort of unhinged extremist rhetoric. Partly, it’s a hazard of their utter insulation from ever having to experience the practical impact of the policies they advocate. Violence and chaos have a way of breaking through the barriers that separate the ivory tower-dwellers from the masses they condescend; one imagines the occupants of Versailles looked out their windows at the guillotine being constructed in the public square and, not understanding what lay in store, pronouncing the structure adorable.

But it’s also what happens when you succumb to the Manichean worldview that every conflict, every issue, boils down to a simple question of who is the more oppressed party. Whichever guy has more privilege, more power: this is your villain. In trying to topple him from his unearned position of influence, his victim can do no wrong. Hamas, composed as it is of Muslim people of colour, is merely punching (and raping, and kidnapping) up.

While the attacks on Israel have given rise to a particularly stomach-turning iteration of this rhetoric, we have seen it before. In 2020, as the US protests against police violence spiralled out of control, members of the laptop class could reliably be found posting that Martin Luther King Jr quote about riots being “the voice of the unheard” — always from the safety of their homes, in nice neighbourhoods, in coastal cities, where things were conspicuously not on fire. The people looting, rioting, and wreaking havoc were members of an oppressed class, and hence above reproach.

But the most absurd example of how true-life horrors become grist for the mill of perverse progressive fantasy popped up downstream of the “decolonisation” discourse. Every now and then, someone announces on the internet that they would begrudgingly allow themselves to be murdered if Native Americans decided to violently re-exert ownership over their ancestral lands. The authenticity of such sentiments is obviously belied by the fact that these same people could, if they wanted to, voluntarily renounce their power instead of waiting for some noble savage to take it by force. If you truly believed yourself to be a colonist, illegitimately squatting on someone else’s property, why would you waste time tweeting about it? Wouldn’t you just leave?

(…)

If civility demands that we hold people to account for the hatred they spew, it also rejects the notion that a person of an “oppressed” identity category should get a free pass to spew hatred. The bar for human decency, surely, does not shift depending on the colour of your skin or the arrangement of your genitals — and to insist on this, on one standard for all people, creates a clear path forward, which may be the best thing about civility as an ethos. It works on the assumption that, as bleak as things are now, there will be an “after” in which we forgive, even if we don’t forget.

(…)

As I left Hudson’s event on Tuesday night, I found the street closed off. Instead of cars, the pavement was occupied by hundreds of people holding signs and banners and flags: the remnants of what had been a massive rally in support of Israel. I would later learn that some people present were captured on camera wishing for the annihilation of Palestine; no one side, as it turns out, has a monopoly on hatred.

As I weaved through the crowd, Leonard Cohen’s “You Want it Darker” was playing through my headphones, a fitting meditation on war, death, and the cruelty we inflict on each other in the name of a just cause.

They’re lining up the prisoners

And the guards are taking aim

I struggle with some demons

They were middle-class and tame

I didn’t know I had permission

To murder and to maim

The chorus to this song is a Hebrew word, a line from the Torah. It’s what Abraham says, in response to God’s request that he sacrifice his son; it is also what we might say to each other, eventually, when civility or decency or whatever deity you believe in asks us to confront and forgive each other’s failings in this moment, the better to thrive in the moments we have left.

Hineni, hineni. I’m ready, I’m ready.”

#hitchens#peter hitchens#petain#pétain#marshall petain#vichy#germany#france#collaborators#collaboration#nazis#antisemitism#rosenfield#kat rosenfield#israel#palestine#gaza#hamas#woke#leftism#communists#french communists#molotov ribbentrop pact#leonard cohen#you wanted it darker

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sunday sounds: 'Ami, si tu tombes, un ami sort de l'ombre à ta place'

This is a very important day for France, for Europe and for the entire world, to be honest.

Chaos strategy, irresponsible choices and an increasing social malaise could see a Fascist majority being very democratically elected, for the first time ever. The Vichy Regime does not count: in July 1940, a scared, fleeing Parliament granted full governing authority to Marshal Pétain without any other formalities than a hastily cobbled plenary session.

What followed was sublime and tragic. It took four years and many scars, never fully resorbed, for Law, Order and Honor to be reinstated. Against all odds and thanks to the desperate, extraordinary and merciless Résistance (yes, all of these three attributes).

Today, more than ever, these sounds resonate wide and deep:

youtube

... and the whole of Europe literally holds its breath. So you see, I am not even sorry to post this old, powerful song twice in a year. I will keep on posting it for as long as it's needed, really.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

The French Revolution may have been one of the world’s first experiments in mass democracy, but those governing France have long had a problem with the idea.

Throughout the 19th century, successive rulers tried to curtail democratic rights or did away with them altogether. Even the advent of universal male suffrage in 1848 did little to inflect this skepticism. A large swath of the governing classes mistrusted the masses and the elections that gave them a voice. (And most of those in power also agreed that women should not be given the vote; they were only enfranchised in 1945.)

The catastrophic defeat of 1940 at the hands of the Germans and France’s experience of authoritarian rule under Marshal Philippe Pétain ensured that, after the liberation of France in 1944, most anti-democratic voices were silenced. But French politicians did not suddenly embrace the democratic process.

On the contrary, the reconstruction of the country after the war was led by unelected technocrats, and when Charles de Gaulle returned to power in 1958, he changed the constitution to ensure that the democratic urges of the French were firmly kept in check. His new constitutional settlement—known as the Fifth Republic—bypassed parliament by creating one of the most powerful directly elected executives in the world. It also instituted a two-round electoral system that was designed to allow voters to express their frustration in the first round before making a “sensible” choice in the subsequent runoff.

As for the French themselves, they have long been aware of the various attempts to keep their political urges at bay. That is why the power of protest and the fear of the angry mob have been powerful driving forces in French politics. Even today, every minister knows that their days are numbered if the street turns against them, regardless of the result of the previous election.

With all of this historical baggage, it is not hard to see why almost everyone was completely taken aback by President Emmanuel Macron’s unexpected announcement on June 9 that he would be dissolving parliament. Only an hour before, the first estimations of the results of the European Parliament elections had been released. There was little in the way of suspense: Opinion polls had predicted for months that the far-right National Rally party would do very well. In the moments before Macron spoke, people were more likely to be worried about finishing their washing-up than the composition of the European Parliament.

But Macron had other ideas. His decision to call an election flew in the face of two centuries of French political history. Every single one of his predecessors would have told him the same thing: When the chips are down, the very last thing you do is ask the French people to decide. They will punish you—not simply because they don’t like you, but also because you had the temerity to ask them what they think.

How, then, can we explain such a momentous and uncharacteristic decision?

In the days since Macron’s announcement, even the most experienced political journalists have struggled to answer this question. It appears that there was a special group of advisors working on the possibility of dissolving parliament. There were also members of Macron’s coalition who were recommending this course of action—especially a cluster of right-wing senators, whose mandate is not dependent on the outcome of direct elections.

But this is hardly an adequate explanation. Presidents always have teams whose job it is to game different political scenarios, and they also have to deal with incessant lobbying from their allies. If we want to understand Macron’s logic then we need to probe deeper into his worldview and his vision of French politics.

We might start with the historical precedents that exist for Macron’s dissolution of parliament. There have been only three preemptive dissolutions of the parliament under the Fifth Republic: In 1962, de Gaulle needed parliamentary support for his decision to create the directly elected presidency. In 1968, he sought a new mandate in the wake of the huge student and worker protests that had taken place in the spring. And in 1997, Chirac hoped to confirm his success in the presidential elections of 1995 by renewing the right-wing majority in parliament.

It is clear which of these precedents is in Macron’s mind. In 1962 and 1968, de Gaulle’s party was massively reelected, and he came away with renewed legitimacy for his policies. In 1997, by contrast, Chirac was severely punished. The left gained more than 200 seats and formed the majority in parliament until 2002. Given how much more fragmented French politics is in 2024—and given the collapse in party discipline since the 1990s—the dissolution of 1997 seems to be a far more accurate guide to what might happen in a few weeks’ time.

Of course, Macron knows his political history; he knows the risks. He might believe that he has the charisma and stature of de Gaulle, but he will be aware that the general himself was punished by the popular vote. When de Gaulle called a referendum on decentralization only a year after his spectacular success in the 1968 parliamentary election, he told the French that he would resign if he lost. And he still lost.

Even the most formidable French leader of the 20th century was ejected from power by a dissatisfied electorate. What makes Macron think he can do better?

The only credible answer, it seems to me, is that he has belatedly embraced the power of chaos. After telling the French incessantly since his first victory in 2017 that he is the guarantor of stability and the only bulwark against the political extremes in France and Europe, he has decided that his goals can be most successfully achieved by utterly destroying the existing system of political parties and coalition.

Already in the past few days, profound realignments have taken place on the left and right of the political spectrum. It is not impossible that the French center right—the political heirs of Gaullism—will all but disappear. On the left, the real fear of a far-right government has forced entirely incompatible politicians, from Trotskyists to centrist social democrats, into an ad hoc alliance. In the best-case scenario, Macron emerges from this turmoil as the only credible figure of government, like a revolutionary leader left standing after a purge.

But the risks of unleashing chaos are huge. Macron could lose his parliamentary power and his party. He could suffer a crushing defeat at the hands of an angry electorate. Most of all, he could permanently tarnish his legacy by being the first French president to swear in a far-right prime minister who is supported by a far-right majority in parliament. The symbolism of this would be almost as powerful as the notorious picture of Pétain shaking hands with Hitler in 1940.

Many people have compared Macron’s gamble to former Prime Minister David Cameron’s decision to call a referendum on the United Kingdom’s membership of the European Union in 2016. But Cameron was naive: He was told he would win, and he had not drawn any lessons from the near-miss of the referendum on Scottish independence in 2014.

Macron is not naive; he understands exactly what he has done. He may, in time, be vindicated. But if he fails, he alone will bear the responsibility for tearing France apart.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

IMAGENES Y DATOS INTERESANTES DEL DIA 12 DE MAYO DE 2024

Día Internacional de la Enfermería, Día Internacional de las Mujeres Matemáticas, Día Mundial de la Fibromialgia y del Síndrome de la Fatiga Crónica, Día Europeo de las PYMEs, Día Internacional de la Sanidad Vegetal, Semana de Acción Contra los Mosquitos, Año Internacional de los Camélidos.

San Nereo, Santo Domingo de la Calzada y Santa Domitila.

Tal día como hoy en el año 2017

Un ciberataque masivo (más de 200.000 infectados) golpea a grandes empresas en al menos 140 países. El virus informático, del tipo rasonware, lanzado desde servidores chinos, afecta a empresas como Fedex, el sistema de salud británico o Telefónica de España. (Hace 7 años)

2010

Se estrella el vuelo 711en la maniobra de aterrizaje en las inmediaciones de la pista del aeropuerto de Trípoli (Libia). En el accidente pierden la vida 103 personas y sólo hay un sobreviviente, un niño de 9 años.

1951

El presidente estadounidense Truman da luz verde a experimentar la bomba de hidrógeno, un arma tan poderosa que, a su lado, la bomba atómica no pasa de ser un mero fuego artificial. La explosión de prueba se realiza en un desolado atolón de Micronesia, en el Océano Pacífico, concretamente, en el islote Eniwetok (islas Marshall). La bomba de hidrógeno, también llamada bomba H, es un ingenio formado por dos bombas, una primera atómica que, al estallar, provoca una reacción de fisión dentro una segunda que consiste en una mezcla de hidrógeno, deuterio, tritio y litio, lo que le otorga un potencial enormemente superior a las bombas de uranio y de plutonio, también llamadas bombas de fisión. (Hace 73 años)

1949

Los EE.UU. y la URSS llegan a un acuerdo negociado en el seno de la ONU para poner fin al bloqueo que sufre la ciudad alemana de Berlín. (Hace 75 años)

1940

Las panzerdivisionen alemanas, después de franquear el bosque de las Ardenas en Bélgica, irrumpen con sus potentes blindados en la llanura francesa, y rebasan por la espalda al ejército francés y la Línea Maginot. El 10 de junio se firmará el armisticio por el que Francia quedará dividida en dos zonas: la ocupada y la "libre", bajo el gobierno colaboracionista con la Alemania nazi del mariscal Pétain. El 14 de junio los alemanes desfilarán victoriosos por los Campos Elíseos de París. (Hace 84 años)

1927

En Nicaragua, Augusto César Sandino anuncia, mediante una circular dirigida a las autoridades locales de todos los departamentos, su determinación de continuar la lucha contra las tropas de intervención estadounidenses que en enero desembarcaron en Corinto. (Hace 97 años)

1926

A bordo del dirigible Norge, el explorador noruego Roald Amundsen, el científico americano Lincoln Ellsworth y el ingeniero italiano Umberto Nobile (diseñador del dirigible), logran sobrevolar el Polo Norte por primera vez. (Hace 98 años)

1776

En Francia, Luis XVI, presionado por la nobleza, destituye al director general de Finanzas que ha suprimido los impuestos que pesan sobre los económicamente débiles, cargándoselos a cambio a los terratenientes. (Hace 248 años)

1588

Enrique III, rey de Francia, huye durante un levantamiento de los católicos y será apresado más tarde por el pretendiente católico al trono, duque Enrique de Guisa. El rey se verá obligado a nombrar al duque, lugarteniente general de Francia. (Hace 436 años)

1551

En Lima, Perú, se funda la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, la más antigua de América. (Hace 473 años)

1539

El conquistador y explorador español Hernando de Soto, hasta hoy gobernador de Cuba, sale de La Habana con 11 naves y casi 1.000 hombres aprovisionado con abundantes víveres y armas para emprender la conquista de La Florida, descubierta por Juan Ponce de León en 1513. Unos días después llegará a la costa occidental de la Florida, cerca de la actual Bradenton. Desde allí iniciará la exploración del territorio y descubrirá, para su desgracia, que en vez de hallar abundante oro, el lugar bulle de pantanos plagados de mosquitos, con una húmedad y calor extremos. Los nativos también le hostigarán complicándole su labor de exploración. (Hace 485 años)

907

El emperador chino Ai Di es depuesto por el ejército de Zhu Wen, cabecilla de la insurrección campesina, poniendo punto final a la dinastía Tang tras 289 años de gobierno y 21 emperadores, en los que China se mantuvo unida convirtiéndose en modelo político y centro cultural del Asia Oriental. (Hace 1117 años)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Background: 127 Years of History

May Day is observed as International Workers’ Day in France, as it is in many other countries. For more than a century, workers, trade unionists, traditional leftists, and anarchists have demonstrated together or separately to pay tribute to the struggles of the late 19th century and the introduction of the eight-hour workday.

Yet May Day has never been limited to legal demonstrations. On May 1, 1891, in Fourmies, soldiers shot at striking workers, killing nine people—including four under the age of 18—and injuring 35 more. Afterwards, a crowd took the streets of Clichy brandishing a red flag. At the end of the demonstration, police attempted to seize the revolutionary emblem, provoking a riot. Gunshots echoed in the streets and some policemen were injured. Three anarchists were arrested and detained. Tried in August 1891, the defendants were sentenced to up to 5 years in prison. These events awoke the convictions of many future radicals, including the notorious anarchist François Koënigstein, better known by his nickname, Ravachol.

In France, May Day also has other connotations. In 1941, aiming to force a rupture with socialism, Marshal Pétain—fervent anti-Semite, head of the French government during the occupation, and among those chiefly responsible for state collaboration with the Nazis—passed legislation declaring that May Day would be called la Fête du Travail et de la Concorde Sociale (“the day of labor and social harmony”). Since then, Labor Day in France continues to bear the name “Fête du Travail,” paying tribute to Pétain’s maxim ”Travail, Famille, Patrie” (“Work, Family, Fatherland”).

During the 1950s and 1960s, Labor Day disappeared in France. During the war in Indochina (1946–1954) and the Algerian War of Independence (1954–1962), successive French governments seeking to preserve their colonial holdings instituted a State of Emergency (1955-1958-1961). The state used this “exceptional” law granting special powers to the executive branch to forbid demonstrations of all kinds in France. It was only on May 1, 1968 that people in France were once again able to take the streets to celebrate Labor Day.

More recently, in 2016 and 2017, anarchists and other autonomous rebels succeeded in taking the front of the afternoon May Day demonstration, relegating trade unions and political parties to the end of the procession. By adopting an offensive strategy—attacking every single potential target on our route—we brought new life to the demonstration, interrupting the ritual it had become.

As we approached May Day 2018, we faced a new challenge. Once again, we had to rewrite the story.

#analysis#France#May Day#Paris#labor#may 1st#anarchism#resistance#autonomy#revolution#community building#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#anarchy#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economics#anarchy works#environmentalism

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was not until 1941, under Marshal Pétain (France), that lily of the valley was officially associated with the “festival of labor and social harmony” established by the head of the Vichy regime. The latter in fact prefers the white flower to the red wild rose, the latter being too associated with the left and communism for his taste.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 6.16 (after 1910)

1911 – IBM founded as the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company in Endicott, New York. 1922 – General election in the Irish Free State: The pro-Treaty Sinn Féin party wins a large majority. 1925 – Artek, the most famous Young Pioneer camp of the Soviet Union, is established. 1930 – Sovnarkom establishes decree time in the USSR. 1933 – The National Industrial Recovery Act is passed in the United States, allowing businesses to avoid antitrust prosecution if they establish voluntary wage, price, and working condition regulations on an industry-wide basis. 1940 – World War II: Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain becomes Chief of State of Vichy France (Chef de l'État Français). 1940 – A Communist government is installed in Lithuania. 1948 – Members of the Malayan Communist Party kill three British plantation managers in Sungai Siput; in response, British Malaya declares a state of emergency. 1955 – In a futile effort to topple Argentine President Juan Perón, rogue aircraft pilots of the Argentine Navy drop several bombs upon an unarmed crowd demonstrating in favor of Perón in Buenos Aires, killing 364 and injuring at least 800. At the same time on the ground, some soldiers attempt to stage a coup but are suppressed by loyal forces. 1958 – Imre Nagy, Pál Maléter and other leaders of the 1956 Hungarian Uprising are executed. 1961 – While on tour with the Kirov Ballet in Paris, Rudolf Nureyev defects from the Soviet Union. 1963 – Soviet Space Program: Vostok 6 mission: Cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova becomes the first woman in space. 1963 – In an attempt to resolve the Buddhist crisis in South Vietnam, a Joint Communique was signed between President Ngo Dinh Diem and Buddhist leaders. 1972 – The largest single-site hydroelectric power project in Canada is inaugurated at Churchill Falls Generating Station. 1976 – Soweto uprising: A non-violent march by 15,000 students in Soweto, South Africa, turns into days of rioting when police open fire on the crowd. 1977 – Oracle Corporation is incorporated in Redwood Shores, California, as Software Development Laboratories (SDL), by Larry Ellison, Bob Miner and Ed Oates. 1981 – US President Ronald Reagan awards the Congressional Gold Medal to Ken Taylor, Canada's former ambassador to Iran, for helping six Americans escape from Iran during the hostage crisis of 1979–81; he is the first foreign citizen bestowed the honor. 1989 – Revolutions of 1989: Imre Nagy, the former Hungarian prime minister, is reburied in Budapest following the collapse of Communism in Hungary. 1997 – Fifty people are killed in the Daïat Labguer (M'sila) massacre in Algeria. 2000 – The Secretary-General of the UN reports that Israel has complied with United Nations Security Council Resolution 425, 22 years after its issuance, and completely withdrew from Lebanon. The Resolution does not encompass the Shebaa farms, which is claimed by Israel, Syria and Lebanon. 2002 – Padre Pio is canonized by the Roman Catholic Church. 2010 – Bhutan becomes the first country to institute a total ban on tobacco. 2012 – China successfully launches its Shenzhou 9 spacecraft, carrying three astronauts, including the first female Chinese astronaut Liu Yang, to the Tiangong-1 orbital module. 2012 – The United States Air Force's robotic Boeing X-37B spaceplane returns to Earth after a classified 469-day orbital mission. 2013 – A multi-day cloudburst, centered on the North Indian state of Uttarakhand, causes devastating floods and landslides, becoming the country's worst natural disaster since the 2004 tsunami. 2015 – American businessman Donald Trump announces his campaign to run for President of the United States in the upcoming election. 2016 – Shanghai Disneyland Park, the first Disney Park in Mainland China, opens to the public. 2019 – Upwards of 2,000,000 people participate in the 2019–20 Hong Kong protests, the largest in Hong Kong's history.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Marshal Pétain on a vintage postcard

#postal#ptain#briefkaart#photo#sepia#postkaart#vintage#pétain#tarjeta#ephemera#postcard#postkarte#photography#marshal#historic#ansichtskarte#carte postale

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Vichy regime incorporated the forest into its ‘back-to-the-land’ programme constructing the forest as a traditional, stable site in which to morally regenerate France. Jacques Chevalier, conservative philosopher and minister for public instruction between December 1940 and February 1941, considered that ‘life in the forest is the most healthy there is for the body and the soul, freeing us from the artifices of modern society’. He suggested that ‘eternal’ France resides in the forest. The forest constituted:

A living symbol of tradition, perpetuating history; old France is preserved better here than anywhere else; the present unites effortlessly with the past. In the silence and depth of the forest centuries replace one another, slowly, continuously, in the same way that the oak’s sapwood binds a new layer to those of springs and autumns past.

For Chevalier, trees represented a link between France’s past and present and acted as a guarantor of French traditions. Chevalier’s musings on trees and tradition are by no means uncharacteristic of the symbolic appropriation of trees. In the words of Douglas Davies, the tree is ‘a living entity, spanning many human generations. As such it avails itself as a historical marker and social focus of events’.

Forestry associations strove to incorporate the forest within the ‘National Revolution’. Just after the defeat, J. Jagerschmidt, the general secretary of the Comité des forêts argued that the forest was a ‘refuge of [the] old principles’ of Work, Family, Homeland. For Jagerschmidt, the forest epitomised the virtues of labour because ‘woodcutters and charcoal burners laughed at the paid holidays and forty hour week that the [Third Republic] wanted to impose on them’. Forest workers did not need to be told to work ‘from sunrise to sunset’. Family and forest also went together, according to Jagerschmidt, because the latter was a

symbol of tradition . . . of which the evolutionary rhythm exceeds several times the length of human life, [so] chimes perfectly well with the notion of the family, the linking of successive generations.

Furthermore, it was in the depths of the forest that the country’s ‘heart’ belonged. It is unclear whether such rhetoric represents deeply held beliefs or lip service to the newly installed regime. Either way, the forest’s politicisation is evident. The irony was, however, that such ‘back-to-the-land’ rhetoric simultaneously politicised the forest and constructed it as a space of ‘natural’ (and therefore apolitical) values and traditions

In a similar way to the peasant, the bûcheron (or woodcutter) was transformed into a patriotic figure labouring to regenerate France. Working in the forest helped strengthen male bodies and remake masculinity in post-defeat France. Two state foresters, Roger Blais and Gérard Luzu, published a guide to the ‘tough school’ of the forest, which presented forestry work as the most ‘radical’ return to the land and ‘an integral part of rural reconstruction’. They highlighted the ‘physical and moral enrichment’ the forester gleaned from the forest, ‘contributing to the affirmation of values and personal autonomy within the framework of nature’s laws and collective life’. In contrast to the ease of city living, life in the forest was ‘hard and healthy’ and woodcutting a ‘noble and free occupation’. Blais and Luzu also called for the forestry profession to conform to the principles of ‘social spirit and true hierarchy as outlined by the head of state’. Similarly, a 1943 article in Revue des Eaux et Forêts argued that ‘living in nature’ is the ‘best school’ and working in forestry teams countered individualism and selfishness because it cultivated the qualities of ‘sacrifice and charity’. These visions of forest life chimed with Vichy’s assumption that hard work was redemptive and served a national purpose.

Likewise, the forestry work of the Chantiers de la Jeunesse was supposed to contribute to male moral and physical regeneration. The Chantiers leadership viewed the forest as a safe and wholesome place, distant from the supposed immorality and decadence of modern society that reached its zenith in the city. From the outset, the Chantiers strove to remove its recruits from the ‘deleterious influence of the towns’ by making them camp out ‘in the great outdoors (en pleine nature), in the middle of the forest, hidden from all forms of trouble or agitation’.

The forest supposedly held important lessons for these young men, as it did for the rest of society. At Tronçais, Group One of the Chantiers dedicated a tree to their leader, Commissaire Furioux. In his speech during the ceremony, Forestry Inspector Desjeux pronounced that

it is through the living example of the forest, an example of tradition, continuity, and grandeur that [Furioux] wanted to impress on all those who had the honour of obeying [his] orders.

In a similar vein, Forestry Conservator Pascaud used his speech to identify the forest’s exemplary demonstration of ‘solidarity’. In particular, the oak tree towering serenely above surrounding trees protects them so that they grow to share the ‘light in which he bathes’. Addressing the Chantiers, Pascaud continued:

This solidarity of all plants, is it not the image of the best of societies where the leader must dominate in his pre-eminence while feeling himself surrounded, supported, [and] aided [by his followers]? If his entourage fails him, he succumbs, whatever his qualities. Let us remember this example at a moment when divisions lie in wait for us.

There was, however, some discrepancy between the regime’s rhetoric and the reality of forest life. The Chantiers’ leaders were well aware of the young men’s indifference, even outright hostility, to their new role as woodcutters. A 1943 report lamented that the Chantiers’ early enthusiasm and their ‘mentality of explorers out to discover new lands’ had since dissipated. Instead, the men no longer recognised the ‘usefulness of their work’ and the leadership itself admitted that ‘forestry work, interesting at first, quickly becomes monotonous, [and] tedious. Their hearts are not in the felling. Boredom is the dominant characteristic’. The joys of being a woodcutter were lost on those forced to work in the forests.

Nonetheless, the image of a stately oak leading and protecting his followers was a popular one. Yvonne Estienne’s illustrated children’s story La belle histoire d’un chêne (1943) compared France to a forest that had just been struck by a fierce storm. During the storm, trees swayed alarmingly in the wind and petrified birds and animals rushed to find shelter 'all the forest is unhappy. It looks for help’. Help came from the forest’s leader, a ‘tall, solid, upright tree’ who fears nothing and protects its charges. In case her young readers had missed the analogy, Estienne moved the story onto contemporary events: during the military defeat the French had fled from the enemy and its bombs ‘like the rabbits of the wood’. But luckily for France there was hope:

there existed, as well, in the forest of France – because men [sic] resemble trees – a tall, beautiful oak, already old but so valiant that he stood strong to protect everybody. And this tall, beautiful oak was called Marshal Pétain.

Helpfully, the Pétain oak tree carefully explained where the forest had gone wrong and how it should reform itself.

Vichy’s ideological appropriation of the forest reached its high point in Tronçais where an oak tree was named after Pétain on the initiative of Chevalier (his godson) and in the presence of forestry officials. Like the supposedly exceptional qualities of Pétain, the oak tree chosen to bear his name stood out from the rest: it stood 35 m high, was 260 years old and boasted good foliage. During the naming ceremony, Pétain unveiled a plaque bearing the words ‘Chêne Maréchal Pétain’ and made three marks on the tree with a Forestry Administration hammer. On one level, this event can be interpreted within the framework of the cult of personality created around Pétain, who admitted that he hoped that he would be able to ‘remain as upright as this tree in order to be able to devote [himself] to the service of the country’. The ceremony also implied that Pétain, like his oak tree, embodied the latest in a vulnerable line of strong, upright men devoted to France. As Chevalier asked during the ceremony; ‘who could doubt a country which produces such trees and such men?’

But beyond the construction of Pétain’s cult of personality, it is not too fanciful to see this marking of the tree as a performative device to reinforce the importance of the forest and the state’s claim to govern it. The occasion also served as a reminder of the forest’s historical role as ‘saviour’ of France. During the ceremony, Chevalier reminded his audience that this ancient forest provided wood for the Navy in 1793 and timber for the Army in 1917. Caziot, in a speech prepared for the ceremony, also emphasised the forest’s role as a productive space of ‘exceptional value for the material reconstruction of the country’. Now that France had crumbled under German invasion, forests would enable the nation to recover its former glory.

The ceremony suggested that Tronçais, which the state had replanted in the late seventeenth century, was physical evidence that France could rebuild itself under Vichy’s guidance. Caziot called for a contemporary display of determination equal to that of foresters who had replanted Tronçais:

The state of the Tronçais forest in 1670, was it not the image of France today, of the ravaged France, morally demolished by more than half a century of hideous demagogy? The war then added its own disasters. Today, everything must be remade, morally and materially. It is a fearsome task and one which demands long and patient effort as the rot runs deep. But the base has remained healthy and solid and allows for hope . . . On this solid base, which is the foundation of France, we can, in the image of Tronçais, remake a vigorous and healthy France. The oak which bears [Pétain’s] name must be a lesson and a symbol for everyone.

In this speech, Caziot compared the Third Republic with the damaged pre-1670 forest, but suggested that all was not lost because the forest’s essential nature (like France’s) had remained intact. There is also a sense that the forest’s and France’s ‘true’ essence lay beneath the surface of democracy and modernity, waiting to be recovered and restored. This speech was a manifestation of the right-wing idealisation of ‘True France’, which, as Herman Lebovics suggests, relied on a ‘discourse [that] employs the essentialist determinist language of a lost hidden authenticity that, once uncovered, yields a single, immutable national identity’.

Yet the forest’s political symbolism need not be reactionary. Vichy’s appropriation of the oak tree echoed previous state manipulation of this species. Ironically, given Vichy’s hostility to the French Republic, in the years following the French Revolution oaks were moulded into ‘Liberty Trees’. Like Vichy, revolutionary governments elevated the oak to the status of a ‘beacon tree’ controlling and sheltering surrounding trees. Moreover, French resistance units occupied the forest’s physical and symbolic space, transforming it into a site of resistance.

As the Occupation dragged on, resistance fighters identified the forest as a place to seek refuge and a base from which to oppose the Vichy regime and the German occupier. In places this development manifested itself symbolically. At Tronçais in February 1943, a resister reportedly scaled Pétain’s oak, replacing the plaque bearing the Marshall’s name with the following:

Chêne Gabriel Peri French Patriot Shot by the Nazis

Consequently, Pétain’s oak is now officially known as the ‘Oak of the Resistance’. But beyond this symbolic act, the resistance reclaimed the forest in more material ways." - Chris Pearson, Scarred Landscapes: War and Nature in Vichy France. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2008. p. 56-61.

#world war ii#occupied france#vichy france#régime de vichy#forêt de tronçais#l'allier#forêt domaniale#environmental history#histoire de france#research quote#reading 2024#national revolution#oak tree#reclaiming youth#forestry#revoluntion nationale#back to the land#chantiers de la jeunesse#marshal pétain

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I, the intellectual

I acted perfectly consciously, in the middle of my life, according to the idea I had formed of the duties of an intellectual.

The intellectual, the writer, the artist is not a citizen like any other. He has duties and rights which are superior to those of others.

This is why I took a bold decision; but in moments of turmoil the average individual is in the same situation as the artist. In those moments the State does not provide any definite direction or any aim which is sufficiently elevated. This is how it was in 1940. Marshal Pétain offered us unity, but that was all: it was a shadow void of content. So some brave men went to Paris, others to London.

Those who chose London have been more fortunate; but for the time being the last word has not been said.

I went to Paris and, together with a few other people, we decided to take it on ourselves to go beyond strictly national interests, to brave general opinion, to be in a minority regarded with hesitation, doubt, distrust, and, finally, to be cursed when our luck turned at El Alamein and Stalingrad.

It is the duty of the intellectual, or at least of some of them, to go beyond the event, to take risks, to try out the roads of History. If they choose the wrong moment, it is too bad. They have performed a necessary mission, that of being outside the crowd - whether before, behind, or beside, is of no consequence: what matters is to be outside. Tomorrow is not made of what one side has seen today. Tomorrow is made both of what the majority have seen and what the minority have seen.

A nation is not a single voice, it is a concert. There must always be a minority; and we were that minority. We lost, we have been stigmatised as traitors: that is right. You would have been the traitors if your cause had been defeated.

And France would have been no less France; Europe, Europe.

I am one of those intellectuals whose duty is to be in the minority.

Minority! We are several minorities. There is no majority. That of 1940 soon dissolved, and yours, too, will dissolve.

The resistance

So many minorities: The old democracy

The communists

I am proud of having been one of those intellectuals. Later people will lean over us in order to hear a sound different to the common sound. And this weak sound will grow louder.

I did not want to be an intellectual who prudently measures his words. I could have written in secret (I had thought of doing so), written in the free zone, abroad.

No, one must assume one's responsibilities, join impure groups, acknowledge that political law which obliges us to accept contemptible or odious allies. We must dirty our feet, at least, but not our hands. And this is what I did. My feet are dirty, but my hands are clean.

I did not indulge in any activity in these groups. But I joined them so that you could judge me today, so that you could pronounce a common, vulgar sentence. Judge me, then, since you are the judges or the jurors.

I put myself at your mercy. But I am sure of escaping from you in the long run. I am sure of finding a place of my own, in time, in the distant future.

But, when the time comes, you must judge me in full. That is why I am here.

You will not escape me, I will not escape you.

Be true to the pride of the Resistance as I am true to the pride of the Collaborators. Do not cheat me any more than I am cheating you. Sentence me to death.

No half measures, now. Thought had become easy and it has now become difficult again. Do not allow the former facility to return.

Yes, I am a traitor. Yes, I worked with the enemy. I offered the enemy French intelligence. It is no fault of mine if this enemy was not intelligent.

Yes, I am no ordinary patriot, no limited nationalist: I am an internationalist.

I am not only a Frenchman, I am a European.

You are Europeans too, whether you know it or not. But we played and I lost.

I demand the death penalty.”

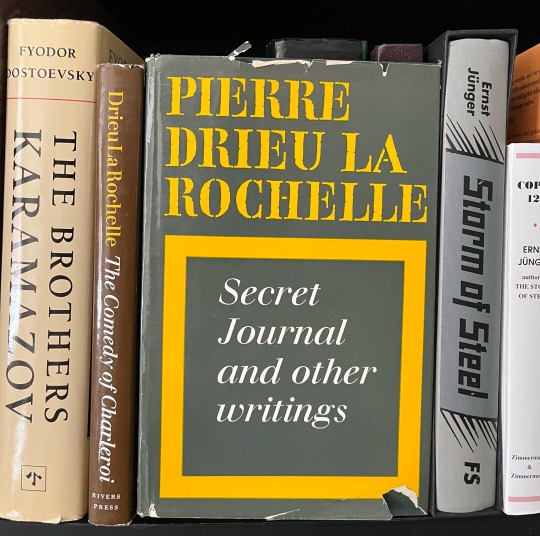

#drieu la rochelle#pierre drieu la rochelle#secret journal#petain#marshal pétain#vichy#vichy france#collaborators#ppf#doriot#fascism#fascist#intellectual#suicide#death#dostoevksy#brothers karamazov#jünger#ernst jünger#storm of steel#books#bookshelf#library#wwiii

1 note

·

View note

Text

Dear 'Hi, darling' Anon

You are so polite and I am so sorry. But I am not going to publish your ask here. The question has been asked before, in many different ways, which tells me a lot about this fandom's - maybe understandable - impatience. The reason I will not answer it in here is simple: as tempted as I might be, I will not write the damn script.

I am an optimist and I believe these two are good people. It is as simple as that.

However, what I can and will do for you, is to tell you a real French story I will try to sum up as best as possible. You take out of it whatever you want. I am just the narrator, here.

I suppose you are not very familiar with this guy, are you?

His name was François Mitterrand, and from 1981 to 1995 he was the President of the French Republic. A cunning, even ruthless politician, he managed the feat of uniting a French Left in shambles and leading it back to power after more than twenty years on the opposition benches. He truly was the master of all combinations, with an almost diabolic sense of human nature and a cult for secrecy and privacy. So much so, that even in a country like France (where people are rather fond of gossip and backstage gaming, provided all of this is masterfully executed) he was nicknamed both 'The Florentine', in an expected parallel to Machiavelli, by politicos & pundits, and 'Tonton' (Uncle), by all the rest of the nation.

His only weakness was to have led a double life for 30 years.

A scion of a deeply Catholic bourgeois family of vinegar distillers from Jarnac, Mitterrand married the atheist and radical Danielle Gouze in 1944. They met in harsh times, while he was one of the chiefs of the French Résistance, after being an underling of Marshal Pétain's Nazi collaborating puppet regime, based in Vichy. They never divorced, even if the couple became increasingly estranged after the birth of three sons, in rapid succession. She found solace in the arms of a Corsican sports instructor and he, by now a rising star of French politics, went his merry way with probably hundreds of affairs. I bet you couldn't tell, by simply looking at his official portrait, but hey - never judge a book by its cover.

By the autumn of 1965, Mitterrand started his lifelong affair with Anne Pingeot, an Art History student at the fabulous Ecole du Louvre, hailing from a well-heeled family in Clermont-Ferrand. She met him in 1957, while vacationing with her parents in Hossegor, a posh summer resort on the Atlantic coast. Both families stroke up a polite holiday friendship, so when Anne went to study in Paris, Madame Pingeot naturally asked 'François' to keep an eye on her daughter. It took him two years to seduce her, with flowers, daily letters, books, midnight walks, art exhibitions, concerts, lies, stories, restaurants and drama - Frenchmen really, really are unparalleled at this cat and mouse game. They never broke up and if Mitterrand never was exclusively attached to her, she remained the love of his life until his very last day on Earth.

The only real crisis moment in this stars aligned story came in 1973, when Anne really wanted out of the whole charade. She wanted a younger partner, an easier plot and (of course) a child. He relented. Mazarine was born in December 1974, in the deepest possible secrecy, somewhere in Southern France (this is a well-known plot device in any good French Nineteenth century novel, by the way). Her father legally recognized her only in 1984, via a simple notary statement. From 1981 to 1995, the second family shared an apartment in a building reserved for the Elysée Palace top level public servants, on Quai Branly, in Paris. At the same time, Mitterrand kept his usual home on rue de Bièvre, steps away from Notre Dame cathedral, on the Left Bank and made sure he was regularly seen there by the press, the paparazzi and the odd passerby. Anne and Mazarine were always monitored by the President's security detail, of course.

Did people know? Many did and at least as many didn't have a clue. Mitterrand was a master at separating his social life into concentric zones, but even as such, lots of people in his intimate circle had no idea he was a new father to that little girl whose toys they sometimes saw in the trunk of his official car, or who happened to be around at political gatherings. They simply assumed the toys belonged to his grand-daughters, the fugitive appearance was a relative and in general, they knew better than asking questions. Sometimes, he joked in interviews, as in 1986, when he told, on a very relaxed tone, to French TV star journalist Yves Mourousi "a certain little miss of my acquaintance told me I have to be more chébran (slang for also slang branché - trendy) and as you see, I am doing my best". Nobody batted an eyelid. When Mazarine dutifully wrote on her first day at school, sometime around 1983, "President of the French Republic" under the Father's job entry on the yearly data sheet every pupil must fill in, the headmistress thought she was joking and never brought it up again. Some of her school friends were even invited for pajama parties at Souzy-la-Briche, at the time the week-end residence of the French President, and even met Mitterrand. Nobody ever spoke.

But some people did know and could not exactly remain silent. When Françoise Giroud, a legend of French journalism, published, in 1983, at the Mazarine publishing house (!), her roman à clef (novel with a key), Le bon plaisir (As He Saw Fit), heavily alluding to the Mitterrand situation, she was forced by her editor to write a very clear frontpage disclaimer. She also had to tinker a bit with details: it was a boy, not a girl, etc. But when venomous polemist Jean-Edern Hallier, disgruntled that his support efforts were left unrewarded, wrote a tell-all pamphlet L'Honneur perdu de François Mitterrand (François Mitterrand's Lost Honor), in 1984, the manuscript mysteriously vanished without a trace (the book appeared, however, after Mitterand's death, in 1996).

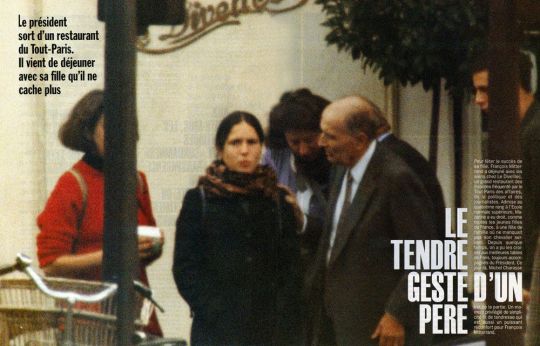

All was revealed in 1995, by a paparazzi photograph being published by the reliable people's magazine Paris Match, with no intervention of the French Presidency administration to stop it. On its cover, a by now terminally ill with cancer Mitterrand was seen standing with Mazarine in front of the (wonderful) fish restaurant Le Divellec, in Paris, under the caption (I will never forget it): La fille cachée du Président (The President's Hidden Daughter). Body language was very clear (another caption: The tender gesture of a father):

And the good people of France could finally see Anne and Mazarine mourning him, on January 11, 1996, after he let himself die upon finding out that the disease attacked his brain:

First row, near the official family.

As I said, draw your own conclusions, Anon. I am not implying anything and I do not think, by any means, this is a copycat scenario. Two fifi la plume (= scoundrel, but also naïve) B-listers are not a powerful French politician, with a decisive influence on the country's society, media and secret services. The UK or the US are not France, never will be. The Eighties had no Facebook, no Twitter, no Internet and no cell phones, able and willing to turn just about anybody into a paparazzo. Mitterrand's fandom, if you want, was the Socialist Party and its army of ambitious technocrats, not the considerable mess that is the OL circus.

What I am implying, is that no secret, no matter how deeply buried, stays forever in the shadows. Have a little more patience and, damn it, faith.

I rest my case.

PS: Anne Pingeot is a Taurus. Don't mind me. I am just babbling, as usually. ;)

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reinstate Pre-Occupied Vichy to Flee There.

After France suffered a crushing defeat in the campaign on the Western Front against the Wehrmacht in May and June 1940, it was forced to sign a separate capitulatory armistice with the Germans. The liberal regime of the parliamentary Third Republic lost legitimacy in the eyes of most of society. On July 10, in the resort town of Vichy, where the government and parliament had fled, deputies voted to transfer all power to the Prime Minister, the 84-year-old hero of the First World War, Marshal Philippe Pétain. The absolute majority of deputies, both right and left, voted to abolish the republic in favor of Pétain's unrestricted war-time power. Most foreign countries, not only Axis members, but also the USA, USSR, Canada, Switzerland and others, recognized the new regime.

The crisis of legitimacy of Vichy Republic occurred in November 1942. Then the Americans landed in North Africa and convinced the local military loyal to President Pétain to go over to the Allies. Hitler considered the Vichy authority unreliable and in response ordered the occupation of southern France. At the time of the occupation of southern France, Pétain did not fly over to the British as it did leader of Free France gen. De Gaulle, but remained in the metropolis. According to the marshal's supporters, he thereby saved France, at the cost of his reputation, from the fate of, for example, Poland, where there was no collaborationist government, and the Germans had a free hand to commit terror against the local population.

0 notes