#marcel proust novels

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

My growing collection of NYRB classics.

Flaubert: “We have fallen into the habit of remembering, whenever we use our eyes, what people before us have thought of the things we are looking at. Even the slightest thing contains a little that is unknown. We must find it. To describe a blazing fire or a tree in a plain, we must remain before that fire or that tree until they no longer resemble for us any other tree or any other fire.”

#classics#art#philosophy#aesthetics#poetry#books#academia aesthetic#literature#gustave flaubert#adolfo bioy casares#marcel proust#nyrb classics#dark academia#light academia#chaotic academia#cottagecore#novels#novella#letters#coffee#jorge luis borges#winter#winter reading#cozy aesthetic#cozy vibes#cozy#winter cozy#cozy winter#reading

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

#marcel proust#novelist#writers#creative writing#writing#writing community#writers of tumblr#creative writers#writing inspiration#writeblr#writerblr#novel writing#writer#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#writers and poets#creative inspiration#let's write#writers corner#writers life#writer stuff#writers community#writers and artists

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

If a little dreaming is dangerous, the cure for it is not to dream less, but to dream more, to dream all the time.

In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

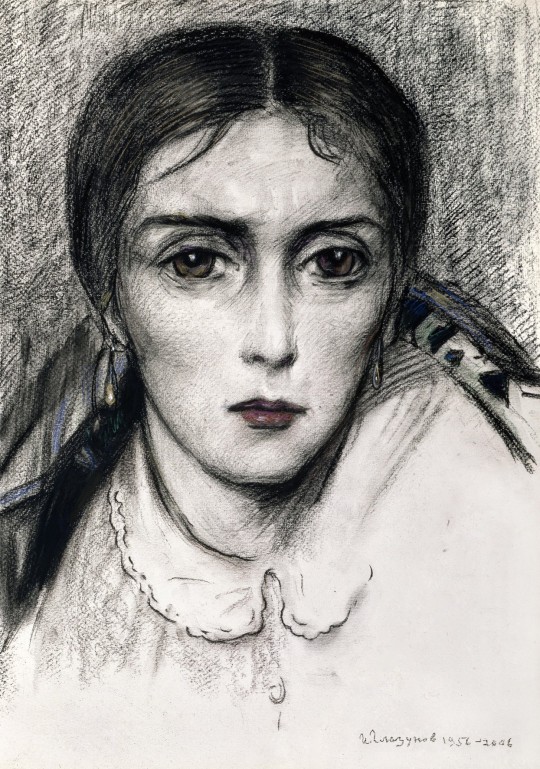

'the Dostoevsky woman (as distinctive as a Rembrandt woman) with her mysterious face, whose engaging beauty changes abruptly, as though her apparent good nature had been but make-believe, to a terrible insolence.' (Marcel Proust)

+ Terrence Malick, Olga Kurylenko: 'He wanted me to combine their influences—the romantic and innocent side, with the insolent and daring side.'

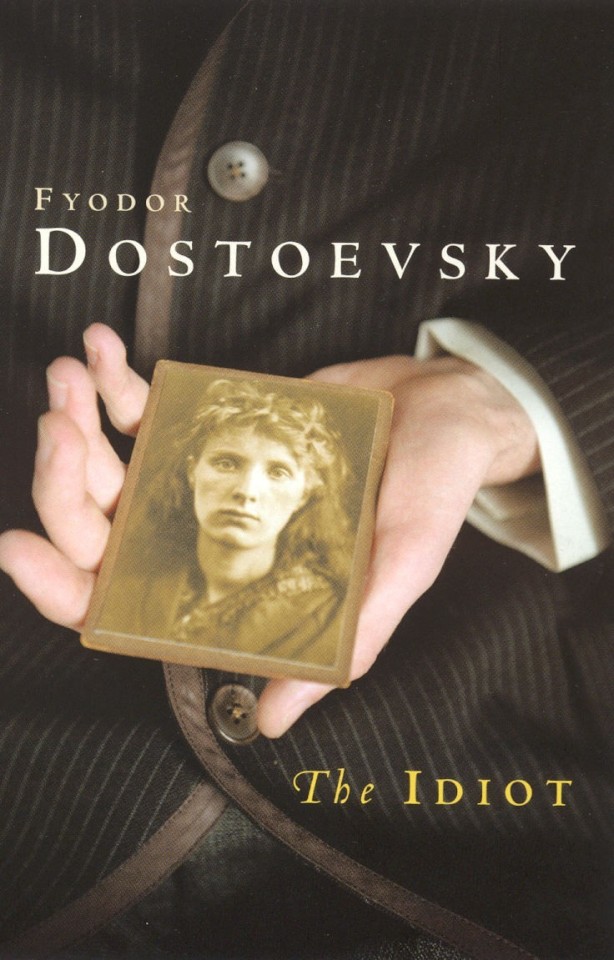

Nastasya Filippovna - Dostoevsky (The Idiot)

“I know that once when your sister Adelaida saw my portrait she said that such beauty could overthrow the world. But I have renounced the world. You think it strange that I should say so, for you saw me decked with lace and diamonds, in the company of drunkards and wastrels. Take no notice of that; I know that I have almost ceased to exist. God knows what it is dwelling within me now–it is not myself. I can see it every day in two dreadful eyes which are always looking at me, even when not present. These eyes are silent now, they say nothing; but I know their secret. His house is gloomy, and there is a secret in it. I am convinced that in some box he has a razor hidden, tied round with silk, just like the one that Moscow murderer had. This man also lived with his mother, and had a razor hidden away, tied round with white silk, and with this razor he intended to cut a throat.

All the while I was in their house I felt sure that somewhere beneath the floor there was hidden away some dreadful corpse, wrapped in oil-cloth, perhaps buried there by his father, who knows? Just as in the Moscow case. I could have shown you the very spot!

He is always silent, but I know well that he loves me so much that he must hate me. My wedding and yours are to be on the same day; so I have arranged with him. I have no secrets from him. I would kill him from very fright, but he will kill me first. He has just burst out laughing, and says that I am raving. He knows I am writing to you.”

Dostoevsky’s Nastasya Filippovna from “THE IDIOT” (Snegovski _)

“but when he was two rooms distant from the drawing-room, where they all were, he stopped as though recalling something; went to the window, nearer the light, and began to examine the portrait in his hand.

He longed to solve the mystery of something in the face of Nastasia Philipovna, something which had struck him as he looked at the portrait for the first time; the impression had not left him. It was partly the fact of her marvellous beauty that struck him, and partly something else. There was a suggestion of immense pride and disdain in the face almost of hatred, and at the same time something confiding and very full of simplicity. The contrast aroused a deep sympathy in his heart as he looked at the lovely face. The blinding loveliness of it was almost intolerable, this pale thin face with its flaming eyes; it was a strange beauty.

The prince gazed at it for a minute or two, then glanced around him, and hurriedly raised the portrait to his lips. When, a minute after, he reached the drawing-room door, his face was quite composed.

…

Mrs. Epanchin examined the portrait of Nastasia Philipovna for some little while, holding it critically at arm’s length.

“Yes, she is pretty,” she said at last, “even very pretty. I have seen her twice, but only at a distance. So you admire this kind of beauty, do you?” she asked the prince, suddenly.

“Yes, I do—this kind.”

“Do you mean especially this kind?”

“Yes, especially this kind.”

“Why?”

“There is much suffering in this face,” murmured the prince, more as though talking to himself than answering the question.

“I think you are wandering a little, prince,” Mrs. Epanchin decided, after a lengthened survey of his face; and she tossed the portrait on to the table, haughtily.

Alexandra took it, and Adelaida came up, and both the girls examined the photograph. Just then Aglaya entered the room.

“What a power!” cried Adelaida suddenly, as she earnestly examined the portrait over her sister’s shoulder.

“Whom? What power?” asked her mother, crossly.

“Such beauty is real power,” said Adelaida. “With such beauty as that one might overthrow the world.” She returned to her easel thoughtfully.

Aglaya merely glanced at the portrait—frowned, and put out her underlip; then went and sat down on the sofa with folded hands.”

“The prince declares, upon marrying Nastasya Filippovna, that it is better to resurrect a woman than to perform the actions of Alexander of Macedonia.”

“The prince. Essential social conviction: the economic doctrine of the uselessness of individual good actions is absurd. On the contrary, everything is based on individual action.”

Dostoevsky, The Idiot’s Notebooks

Photo via X/Twitter

“All we Karamazovs are such insects, and, angel as you are, that insect lives in you, too, and will stir up a tempest in your blood. Tempests, because sensual lust is a tempest—worse than a tempest! Beauty is a terrible and awful thing! It is terrible because it has not been fathomed and never can be fathomed, for God sets us nothing but riddles. Here the boundaries meet and all contradictions exist side by side. I am not a cultivated man, brother, but I’ve thought a lot about this. It’s terrible what mysteries there are! Too many riddles weigh men down on earth. We must solve them as we can, and try to keep a dry skin in the water. Beauty!

… Yes, man is broad, too broad, indeed. I’d have him narrower. The devil only knows what to make of it! What to the mind is shameful is beauty and nothing else to the heart. Is there beauty in Sodom? Believe me, that for the immense mass of mankind beauty is found in Sodom. Did you know that secret? The awful thing is that beauty is mysterious as well as terrible. God and the devil are fighting there and the battlefield is the heart of man. But a man always talks of his own ache.”

The Brothers Karamazov - Dostoevsky

Marcel Proust: “Well, then, this novel beauty remains identical in all Dostoevsky’s works, the Dostoevsky woman (as distinctive as a Rembrandt woman) with her mysterious face, whose engaging beauty changes abruptly, as though her apparent good nature had been but make-believe, to a terrible insolence (although at heart it seems that she is more good than bad), is she not always the same, whether it be Nastasia Philipovna writing love letters to Aglaé and telling her that she hates her, or in a visit which is wholly identical with this — as also with that in which Nastasia Philipovna insults Vania’s family — Grouchenka, as charming in Katherina Ivanovna’s house as the other had supposed her to be terrible, then suddenly revealing her malevolence by insulting Katherina Ivanovna (although Grouchenka is good at heart); Grouchenka, Nastasia, figures as original, as mysterious not merely as Carpaccio’s courtesans but as Rembrandt’s Bathsheba.”

“This radiant, dual face, with sudden bursts of pride that make the woman appear other than she is (‘You are not such,’ Muichkine says to Nastasia in the visit to Gania’s parents, and Alyosha could say it to Grushenka in the visit to Katherina Ivanovna).”

Photo: Olga Kurylenko: Marina, To the Wonder, Terrence Malick

“Terrence Malick recommended that Olga Kurylenko read The Idiot with a particular eye on two characters: the young and prideful Aglaya Yepanchin, and the fallen, tragic Nastassya Filippovna.”

Olga Kurylenko: “He wanted me to combine their influences — the romantic and innocent side, with the insolent and daring side. ‘For some reason, you only ever see that combination in Russian characters,’ he said to me.”

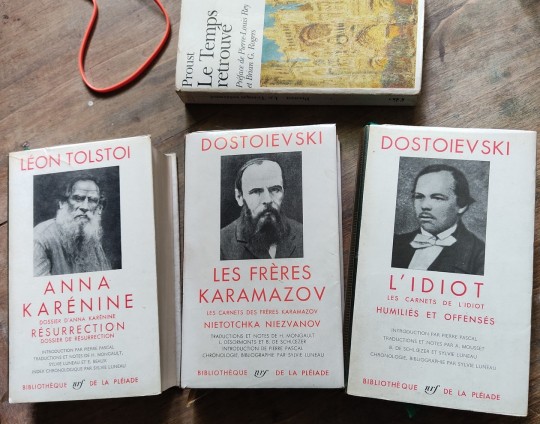

“Anna Karenina, The Brothers Karamazov, and The Idiot: Those books were, in a way, his script,” Olga Kurylenko says”. - BEHIND THE SCENES: https://www.vulture.com/2013/04/how-terrence-malick-wrote-filmed-edited-to-the-wonder.html

…

“In To the Wonder (Terrence Malick), Marina (Olga Kurylenko) has a predisposition to melancholy,” Kurylenko says. “She’s a very unstable woman. She’s suffering. So when she meets a man, she sees him as the ending of all her suffering. But it’s just an illusion.” To prepare, Terrence Malick directed the actress to the bricks of Russian literature – Anna Karenina (Leo Tolstoy), The Brothers Karamazov, and The Idiot (Dostoevsky). Olga Kurylenko: “I didn’t even need the script after that. Those were my script. I built the character as a combination of the different female characters in those books.” https://www.rollingstone.com/tv-movies/tv-movie-news/olga-kurylenko-talks-russian-literature-and-terrence-malick-181787/

"Terrence Malick asked me to reread Anna Karenina, The Brothers Karamazov and The Idiot. All the three of them are that thick!" Olga Kurylenko, 'To The Wonder’, Terrence Malick

“Because life is not a thin book. It is terribly long, and tangled, and dense. Tolstoy didn’t even want to stop War and Peace. Two epilogues, eight new chapters… it was like Time itself in motion. And Dostoevsky, writing these gigantic books precisely because he always wants to start reality anew.” George Steiner, translated from French

#art#heroine#artist#dostoevsky#terrence malick#literature#marcel proust#dostoyevski#novel#portrait#goddess#cinema#proust#girl power#dostoevksy#beauty#malick#olga kurylenko#nastasya filippovna#fyodor dostoevsky#woman#fyodor dostoyevsky#the idiot

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Life' contains situations more interesting, more novelistic than any novel.

from In Search of Lost Time, Book 1: Swann’s Way by Marcel Proust

#in search of lost time#swann's way#marcel proust#proust#life#the book of life#book of life#life is a book#life is an adventure#life is interesting#life is novelistic#life is a novel#novel#novelistic#novelty

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

inspired by a conversation w a friend. literary buffs: what's something based on your reading habits that people probably would assume you've read, but you just haven't? not counting things that are on your i'm-gonna-read-this-soon, oh-i-can't-wait-to-read-this list. just things that certainly exist in the world indifferent to your reading habits. i'll start. i've been a theater buff for as long as i've been a habitual reader and i've never read george bernard shaw.

#text post#literature#this is also a safe space to admit wo shame things youve been too intimidated to read and havent approached if you want to#im not much of a novel reader so its not that ironic or strange for me not to have read it but. ill probably never read tolstoy#or marcel proust or james joyce#well. i wont say never. but its not on my radar for any time soon.#its not that i cant read a novel but i struggle w the medium a lot and id rather just read what comes more naturally to me#not like i dont get a good range out of reading mostly plays and poetry#reblog bait

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remembrance of Things Past #2: Within A Budding Grove, Volume 1

3/5

Heuet's art is very charming with the character designs and gorgeous when it comes to the background and architectural art. As someone who didn't know who Proust is, though, this wasn't great as an entry point. Certainly doesn't help that the rassa-frassin' 500 Essential Graphic Novels book chose this volume instead of the first. Regardless, it's done little to make the very dense text easier to understand, especially when it's still so dense that there's often a panel's worth of space replaced with a paragraph of text. The French album format isn't helping things, either, as it has to try and fit as much as it can within 48 pages, where a full graphic novel would have the room to spread itself out. Maybe this hits real good if you already know Proust and the original novel but didn't do much for us.

Goodreads

#comics#graphic novels#remembrance of things past#within a budding grove#marcel proust#stephane heuet

1 note

·

View note

Text

really missing CHAPTERS right about now like it’s so hard to gain momentum when you can’t tell yourself “just one more quick chapter” bc every part is like 300 pages :)

#i guess it’s all proportional since this book is technically just the first volume of basically the longest novel to ever exist#but i will not be reading the other volumes at least not right away bc omg this is so much#i’m like 150 pages in and the writing is beautiful but i feel like nothing has actually HAPPENED yet#marcel proust undefeated yapping champion#lj reads swann’s way#lj reads books

0 notes

Text

Books the LoTR characters would read:

First of all, a disclaimer: this is my own opinion and I will not care if you think otherwise. Second of all, I always gift books to my friends and family, and I've never got a complaint, so that has to count for something. I'm also putting some of my favourite books but that's just me of course ♡

Frodo:

Sloggiest classical high fantasy books you can find. Yknow these '90s fantasy books with like eleven books in a series, and each book is at least 500 pages long? He would love that.

I'm currently reading the first book of Crown of Stars (seven books baby), which is like an alternate fantasy medieval Europe, with lots of details and research done and it's super gritty and entertaining. Frodo would inhale that. The rest of the Fellowship are worried for him, they haven't seen him in days.

Sam:

Fantasy and poetry because he's cool like that.

Something not to complicated like Uprooted by Naomi Novik, and then he will surprise you by reading something super dark like Blood Over Bright Haven by M.L. Wang.

Also really likes literary fiction. Idk he strikes me as someone who would like reading about people's lives, and a plot where the action is less important than the characters evolution. Tried to read weird lit but didn't like that the main themes were rot and body fluids, it reminds him of Frodo during the Quest.

Merry:

I'm basing this on personal experience; but every time I see a cute guy either on the bus or on the Friday train, they'll be reading something like Marcus Aurelius' Meditations, or something by Hemingway, which does not strike trust, and it's a bit pretentious and on the nose. Like are you really reading Marcel Proust for fun? Be honest with me, my guy, you looked gay (for legal reasons this is a joke).

He likes non-fiction. Some of the books he has are Tristes Tropiques by Claude Lévi-Strauss; Folie et déraison by Michel Foucault; and he once even started talking about how he didn't really agree with Freud's Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis. The glare that the rest of the Fellowship gave him could have killed Sauron on the spot.

Pippin:

I doubt his AuDHD allows him to read anything really dense (or maybe he hyperfixates so badly that he reads one book in less than 12 hours who knows)

Graphic novels and comics are a must in his bookshelf! Eventually becomes a Marvel brainrot fan, to the dismay of everyone else, especially Aragorn who has to pay for the merch.

YA fantasy bc I'm taking into account his age. Percy Jackson hyperfixation and that's why he's gay now (again a joke)

Aragorn:

Romantasy but not of his own volition, he is just a really good partner, and Arwen seems to me like a romantasy girlie. Poor guy has been forced to read A Court of Thorns and Roses, and Fourth Wing, and Powerless. Put the limit at Colleen Hoover (not saying that Arwen likes her either, she just likes to make Aragorn suffer like a good gf). Will deny again and again to the rest of the Fellowship that he likes any of these books, and once even drew his sword at Boromir.

Legolas:

These random ass raunchy period romance books you find on your mother's bookcase just lying there and you read them out of curiosity and end up learning about things you should not be aware of yet, and they're not even written well but you can't stop reading. Chick lit, if you want.

Has read the Bridgerton books multiple times.

Gimli:

Science fiction. Gets really nerdy about alien invasions, but it's not like he believes in any conspiracy theory of course. Legolas barely understands what he's talking about half of the time but who cares when your boyfriend is that cute.

He loves and actually understands pretty well space operas. The Final Architecture trilogy by Adrian Tchaikovsky, and Project Hail Mary by Andy Weir are favourites of his.

Boromir:

Sports romance. HOCKEY. He just likes the whole "turn off your brain to enjoy this" honestly, he needs a break sometimes of course!

Read Vampire Academy out of curiosity and really liked it, though he does admit it and Faramir will act like he doesn't know him (it's actually a good saga I'm sorry okay)

Faramir:

This guy right here owns the entire Realm of the Elderlings book saga. It pains me to admit that he would relate a lot with Fitz.

Heartstopper by Alice Oseman because he's not dead inside, okay?

Éowyn:

Really basic sorry but she is a Hunger Games girlie through and through.

Actually, I feel she would like dystopian fiction a lot. Has watched Divergent (only the first movie, the rest are trash) with Faramir more times than she can count. Faramir gets cold sweats whenever he hears something that reminds him of the movie (he knows the dialogues by heart)

Éomer:

Yes, yes, I know Rohirrim don't read or write, BUT he would own all the Valdemar books by Mercedes Lackey. Why, do you ask? Well, purely because it's a fantasy series of mages that are Chosen by their Companions, which are white horses. And Éomer is a good ol' horse girl so what more could he ask for.

#lotr#lord of the rings#lotr fanfic#lotr headcanons#frodo baggins#sam gamgee#merry brandybuck#pippin took#aragorn#legolas#gimli#boromir#faramir#éowyn of rohan#éomer of rohan

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Notes: Autofiction

Autofiction - (short for autobiographical fiction) is a genre of literature that combines elements of autobiography and fiction.

In autofiction, details of the author’s life blend with fictional information, characters, and events.

It often reads as like a published first-person account of the writer’s real life.

The line between fiction and fact might not always be clear to the reader, leading to a sense of instability in the narrative.

Autobiographical novels are novels that use elements of autofiction.

Characteristics of Autofiction

The specific characteristics of autofiction are subject to interpretation, but some common features in autofiction works include:

Life proximity: Beyond character names, the work will contain similarities between the author’s life and that of the protagonist. The most important one tends to be the role of writing in the protagonist’s life. Often, the protagonist is a professional writer. Some autofiction is a type of autobiographical metafiction, which focuses on the writing and storytelling process.

Name sharing: Authors of autofiction will sometimes share the same name as the protagonist of the novel or short story.

Uncertainty: Much of the tension in autofiction comes from uncertainty about what is real and what is fictional. Some details will be verifiable, but others may be difficult or impossible to determine by a reader, causing speculation.

Examples of Autofiction

Autofiction is a fairly popular genre, and there have been several recent examples of this blend of the real and the fictional:

Every Day is for the Thief (2007): The first novel by Nigerian-American writer Teju Cole, this account of a young man’s journey to Nigeria has a diaristic form, reflecting Cole’s own journey to discover his roots.

My Struggle (2009-2011): In this epic cycle of novels by Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgaard, the author tells the story of his own life. Knausgaard made up details to fill in the blanks of his recollection.

How Should a Person Be? (2010): Canadian writer Sheila Heti constructed this work from interviews with various personal friends, offering a unique version of autofiction.

The Outline Trilogy (2014-2018): Rachel Cusk, a British-Canadian writer, has worked in both fiction and essay form. Critics consider her trilogy of novels, Outline, Transit, and Kudos, to be autobiographical fiction. Unlike most autofiction, the narrator in this trilogy relays information about other characters and not much about herself.

Motherhood (2018): This work of autofiction by Canadian writer Sheila Heti focuses on her struggles about deciding whether or not to have children.

The Topeka School (2019): In Ben Lerner’s work of autofiction, the author describes experiences that closely mirror events from his own life, in scenes set in Kansas and then New York.

A Brief History of Autofiction

Autofiction dates back to Ancient Greece, and its popularity continues to rise.

First-person narratives: First-person narratives with an autobiographical component are nearly as old as literature itself. Some scholars credit “I,” a lyric poem by the Archaic Greek poet Sappho, as an early example of this type of text.

In Search of Lost Time (1913-1927): Scholars consider this seven-volume work by the French novelist Marcel Proust an early version of autofiction. It involves many details and characters from Proust’s own life, although much else is fictionalized.

Autofiction: The term “autofiction” first surfaced when the author Serge Doubrovsky used it to describe his 1977 novel Fils. Sleepless Nights (1979) by Elizabeth Hardwick and I Love Dick (1997) by Chris Kraus were instrumental in popularizing the genre and the use of the term in scholarship and book reviews.

Source ⚜ More: References ⚜ Writing Resources PDFs

#autofiction#autobiography#writeblr#literature#writers on tumblr#writing reference#dark academia#spilled ink#writing prompt#creative writing#books#writing tips#fiction#light academia#booklr#writing advice#bookblr#writing inspiration#writing ideas#writing resources

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remembrance of things past is not necessarily the remembrance of things as they were.

In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marcel Proust

Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust (July 10, 1871 – November 18, 1922) was a French novelist, literary critic, and essayist, best known for his monumental semi-autobiographical novel À la recherche du temps perdu (in French – translated in English as Remembrance of Things Past and more recently as In Search of Lost Time) published in seven volumes between 1913-27. The novel had a profound influence on 20th century literature and helped pioneer the literary form of the stream of consciousness novel. Proust is considered by critics and writers to be one of the most influential authors of the 20th century.

Marcel Proust in 1895

Photo of Marcel Proust by Otto Wegener (1849-1924). On photographer's cardboard, dimensions 14.2 x 10.2 cm. From the series of several poses in 1895, the bottom of the cardboard is not reproduced. Private collection

Photo of Marcel Proust by Otto Wegener (1849-1924), 1895. On photographer's cardboard, dimensions 14.2 x 10.2 cm. Private collection. Source: Vente Sotheby's 7 octobre 2014, Paris, bibliothèque R. et B. L.

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you have any book recommendations for us :D

MAYBE SO.......!!!! u know i love talkin abt books!!!

well, ok since ive posted about most of the books ive been reading recently MAYBE i can also post about some that i ordered and am waiting to arrive??? because all of these sounded very interesting to me!!!

SO books i have coming in the mail:

surrealist novels:

the woman in the dunes by kobo abe

the hearing trumpet by leonora carrington

the melancholy of resistance by laszlo krasznahorkai:

the third policeman by flann o'brien

nadja by andre breton

(been really into surrealism lately if it isn't apparent. most excited for melancholy of resistance i think)

horror, gothic, etc:

bruges-la-morte by georges rodenbach

the damned (la-bas) by joris-karl huysmans

floating dragon by peter straub

classics, short stories, etc:

french decadent tales (oxford world's classics) by stephen romer

in watermelon sugar by richard brautigan

swann's way (in search of lost time, #1) by marcel proust

selected short stories by balzac

icefields by thomas wharton

some ive picked up recently & stoked to read:

ada, or ardor by nabokov (my most beloved author of all time)

carmilla by le fanu

nightmare alley by william lindsay gresham

a king alone by jean giono

twilight of the idols by nietzsche

transparent things by nabokov

dark water by koji suzuki

selected poems by jorge luis borges (also beloved)

trolled my goodreads for more recs

books ive read & enjoyed so far this year:

the iliac crest by cristina rivera garza

the tenant by roland topor (FAV!!! huge fav)

crimson labyrinth by yusuke kishi

pedro paramo by juan rulfo

carolina ghost woods by judy jordan

death in her hands by ottessa moshfegh

the unbearable lightness of being by milan kundera

in the lake of the woods by tim o'brien

disgrace by j m coetzee

goth by otsuichi

books i enjoyed from last year:

the lottery & other stories by shirley jackson

the vegetarian by han kang

rosemary's baby by ira levin

piercing by ryu murakami (an all time fav)

the bloody chamber by angela carter (fav)

starve acre by andrew michael hurley (also a fav)

the glassy, burning floor of hell by brian evenson

the devil's larder by jim crace

monstrilio by gerardo samano cordova

and as a bonus, literally anything by nabokov. i have a big book of his short fiction that ive been reading slowly for a long while. despair by him is my fav book of all time, hands down. he is a master of absurdism (and a master of every language he writes in).

ALSO!!!! if youre into poetry, anything and every single thing by: t.s. eliot, baudelaire, rimbaud, borges. i also love neruda's poetry but i have heard he was an awful man so keep that in mind

#thotbox#thotmail#talky cherub#library cherub#i buy 95% of my books secondhand#i have something of a problem but i figure books are not the worst addiction one can have.....OOPS

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Philip Marlowe, BI: Novels quotes (part 1)

Look, someone had to do it…

When I say Philip Marlowe is bi, I know I’m preaching to the choir, but maybe you need to make someone else realize this very important truth. For your convenience, here’s some quotes from the novels, so you can prove that you’re not ins- okay, you’re on Tumblr so you’re probably insane, but now you’re insane with proof at the tip of your fingers.

This is not an exhaustive list, the quotes are all Marlowe-centred (otherwise I’d quote half the books) and your mileage may vary.

The Big Sleep

Chap 11

“I was beginning to think perhaps you worked in bed, like Marcel Proust.” “Who’s he?” I put a cigarette in my mouth and stared at her. She looked a little pale and strained, but she looked like a girl who could function under a strain. “A French writer, a connoisseur in degenerates. You wouldn’t know him.”

(Reminder that Proust was gay as hell.)

Chap 13

“The pug sidled over flatfooted and felt my pockets with care. I turned around for him like a bored beauty modeling an evening gown.”

Chap 24

“She called me a filthy name. I didn’t mind that. I didn’t mind what she called me, what anybody called me. But this was the room I had to live in. It was all I had in the way of a home. In it was everything that was mine, that had any association for me, any past, anything that took the place of a family. Not much; a few books, pictures, radio, chessmen, old letters, stuff like that. Nothing. Such as they were they had all my memories. I couldn’t stand her in that room any longer. What she called me only reminded me of that.”

(it’s probably a queer slur. Even the radio drama included it.)

Chap 28

“Just a plain pine box,” I said. “Don’t bother with bronze or silver handles. And don’t scatter my ashes over the blue Pacific. I like the worms better. Did you know that worms are of both sexes and that any worm can love any other worm?”

Farewell my lovely

Oh boy. I had to skip a lot.

Chap 3

“He just picked me up. I’m kind of cute sometimes.”

Chap 22

“I think I went to sleep, just like that, with a bloody face on the table, and a thin beautiful devil with my gun in his hand watching me and smiling.”

Chap 35

Everything about Red, but there you go:

“He smiled a slow tired smile. His voice was soft, dreamy, so delicate for a big man that it was startling. It made me think of another soft-voiced big man I had strangely liked.” (ie Malloy)

Chap 36

“I looked at him again. He had the eyes you never see, that you only read about. Violet eyes. Almost purple. Eyes like a girl, a lovely girl. His skin was as soft as silk. Lightly reddened, but it would never tan. It was too delicate. He was bigger than Hemingway and younger, by many years. He was not as big as Moose Malloy, but he looked very fast on his feet. His hair was that shade of red that glints with gold. But except for the eyes he had a plain farmer face, with no stagy kind of handsomeness.”

“I told him about it. I told him a great deal more than I intended to. It must have been his eyes.”

Chap 37

(Still about Red:)

“Put your dough away,” Red said. “You paid me for the trip back. I think you’re scared.” He took hold of my hand. His was strong, hard, warm and slightly sticky. “I know you’re scared,” he whispered. “I’ll get over it,” I said. “One way or another.” He turned away from me with a curious look I couldn’t read in that light.”

(About Brunette:)

“He had a cat smile, but I like cats. He was neither young nor old, neither fat nor thin. Spending a lot of time on or near the ocean had given him a good healthy complexion. His hair was nut-brown and waved naturally and waved still more at sea. His forehead was narrow and brainy and his eyes held a delicate menace. They were yellowish in color. He had nice hands, not babied to the point of insipidity, but well-kept. His dinner clothes were midnight blue, I judged, because they looked so black. I thought his pearl was a little too large, but that might have been jealousy.”

The High Window

Nothing too obvious.

The Lady in the Lake

Chap 3

“He had everything in the way of good looks the snapshot had indicated. He had a terrific torso and magnificent thighs. His eyes were chestnut brown and the whites of them slightly gray-white. His hair was rather long and curled a little over his temples. His brown skin showed no signs of dissipation. He was a nice piece of beef, but to me that was all he was. I could understand that women would think he was something to yell for.” (…) “At the moment I’m not doing anything,” he said coldly. “I expect a commission in the navy almost any day.” “You ought to do well at that,” I said. (...) “So long, beautiful hunk,” I said, and left him standing there.”

(He said the last one to be a jerk but he said it.)

Chap 13

(All of it is a scene between a half-naked Marlowe and the three guys he's bribing with booze and money. Personally I think it’s just a mix between it’s too hot + zero-fuck-given attitude, but I can’t not mention it.)

Unsurprisingly this got long, so part 2 is coming.

#raymond chandler#philip marlowe#the big sleep#farewell my lovely#the lady in the lake#oh the tags in this one <3

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

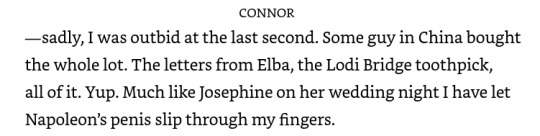

Alan Ruck on what Connor does with his time (and bonus historic penis story).

“If you judge Connor by a business world metric of any kind, he’s a moron. He’s got no game and no interest, but he reads all the time. I think he reads history and I think he reads novels that are 100 years old. I don’t think he reads anything new that he might have to form an opinion about – 'well I didn’t think it was so great' or 'I thought it was really interesting' – he wants something like Marcel Proust Remembrance of Things Past, one of the great works of all time, because people have already made that decision. They’ve already given it that value. So actually, Connor reads a lot it’s just, he just doesn’t know anything of current events.”

“I did a little historic penis research. There’s this thing in a jar that actually looks like it once belonged to a donkey. But it’s claimed to be Rasputin’s penis, and apparently Napoleon’s penis was never very impressive to begin with, but some dentist owns it in new jersey and apparently it’s like a schmeckle, it’s just like a little button of a thing. . . . I did throw that ad-lib into that episode. I was talking about how small Napoleon’s penis was but then I said, ‘but Rasputin’s penis was amazing’. I made Matthew MacFadyen giggle to the point of bending over which is kind of my mission in life.”

Excerpt from the official HBO Succession Podcast: Interview with Alan Ruck - Episode 7

Scene referenced is below the cut.

The Saga of Connor and Napoleon's Dick:

And the thrilling conclusion:

Part 1 of the script excerpt from "The Summer Palace" and conclusion from "Vaulter."

#post-show Connor should start a historic penis podcast#Maxim Pierce can co-host#Willa will produce and it'll be amazing#every episode would be unhinged and awful#I'm 100% here for it#connor roy#hbo succession#cast interviews#succession#alan ruck

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here are some fascinating facts about books that will leave you amazed:

1. Roosevelt read an average of one book per day.

2. Harvard University Library has four books bound in human skin.

3. Iceland tops the world in per capita book reading.

4. People who read books are less likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease.

5. In Brazilian prisons, reading a book can reduce a prisoner's sentence by four days.

6. The most stolen book is the Bible.

7. Victor Hugo’s *Les Misérables* contains a sentence with 823 words.

8. Virginia Woolf wrote all her books while standing.

9. Leo Tolstoy's wife hand-copied the manuscript of *War and Peace* seven times.

10. There are over 20,000 books written about chess.

11. Noah Webster took 36 years to write his first dictionary.

12. The Mahabharata is the only book or epic in the world with over 1,200 characters.

13. Words like “hurry” and “addiction” were invented by Shakespeare.

14. If all the books in the New York Public Library were lined up, they would stretch 8 miles.

15. The longest novel ever written is *In Search of Lost Time* by Marcel Proust, with over 1.2 million words.

16. The first book ever printed was the Gutenberg Bible in 1455.

17. J.K. Rowling is the first billionaire author, thanks to the success of the Harry Potter series.

18. Charles Dickens was paid by the word, which is why many of his books are so lengthy.

8 notes

·

View notes