#manthia diawara

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Quote

We must not tell ourselves that the indeterminate, the uncertain, the un-obvious, is a weakness. We must say to ourselves that it opens our minds to unexpected forms of complexities. The Tremulous thought is not a thought out of fear, scared thinking, it is a thought that is opposed to systematic thinking. All the poets have said it. The gasping, the breathing, the pulse, the misfortunes, the fears, the insane hopes, and the sterile obsessions. All of these need to be relearned and remixed. The poetics of this endeavor seems more important than the categories of quick thinking, that lead to definitive and fixed conclusions. We understand the world better if we tremble with it.

Édouard Glissant in One World In Relation (2010), Manthia Diawara. Film.

#documentary#manthia diawara#edouard glissant#one world in relation#creolization#Black Atlantic#memory#memory studies#decolonial thought#poetics of relation

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

pelican 𓅡

from a letter from yene (2022)

dir. manthia diawara

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

“Um pouco da complexidade africana a partir de seus artistas“: resenha do livro “Em busca da África” (por Silas Fiorotti, A Pátria, Funchal, 17 fev. 2023).

#resenha de livro#revisão#resenha#livros#leituras#books#book review#Manthia Diawara#Editora Zahar#Companhia das Letras#salif keita#williams sassine#guinea#africa#african studies#estudos africanos#silas fiorotti#jornal A Pátria

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black Skin White Screens

Another email response that I think might be useful here. Person was asking a question about why nobody cites Black film as influences: When Moonlight dropped nobody was talking about Clockers even though there were clear visual and dramatic elements referenced. Instead everyone (the filmmakers, critics, etc) was talking about French and Hong Kong cinema. So people even deny Spike's influence.

But, I think you might be mistaking a symptom for the disease. Tons of Black filmmakers were influenced by nonBlack filmmakers. French Impressionism & German Expressionism influenced Julie Dash; Charles Burnett loved British Kitchen Sink cinema; Bradford Young and I had a great convo about Apichatpong Weerasethakul one time; Haile Gerima almost killed me bc I interrupted a screening of Solaris by one of his GOATS Andrei Tarkovsky 😂 Even John Akomfrah's affective proximity, which AJ loves to employ, is an evolution of Eisenstinian montage.

The difference is that most of these filmmakers were steeped in, trained in, and worked in Black film. They weren't working within the studio system (though Burnett would go on to work with Disney in the 90s). There were Black spaces from Studio Museum in Harlem to Performing Arts Society of Los Angeles. There was public funding for TV that Marlon Riggs, Chamba Productions, etc. were able to take advantage of. Now all of these programs are either severely underfunded or gone completely. I think this is the primary reason: There aren't that many (semi)autonomous Black film/cultural spaces left. And so there's no cultural push for such things.

All the money and attention is in white spaces. I know some filmmakers who either did a concept short for a feature or are in prepro on their first feature. The people around them have told them that they need to find European equivalents to their Black influences or else the money and attention will dry up. It's a structural thing. Two suggested comparisons that stuck out to me were Bill Gunn & Steven Soderbergh and Kathleen Collins & Maya Deren. These directors are not doing anything close to the other. It's just "scrappy indie director" and "known female director". I guess that's how things are commodified now.

Back in the 90s John Singleton went to Senegal to study under Ousmane Sembène. Part of the conversation is in Manthia Diawara's Sembéne: The Making of African Cinema. Diawara screened a bunch of cut footage from this conversation a couple years back but I don't think it's online. So literally 30 years ago there was still a connection to the past. What you're describing is a recent development.

So much of the last decade of Black cinema is animated by liberal identity politics and white guilt. from How They See Us to Birth Of A Nation. Even films that aren't so explicit about the white gaze like Moonlight are still affected by this phenomenon. It's not shocking that it won best picture after #OscarsSoWhite nor is the volume of Black cinema represented that year surprising. I have my suspicions that Barry was affected by the same antiBlack forces my friends are fighting now. He was tweeting about Clockers in the months preceding production.

The industry is in flux right now + the transition from Obama to Trump (which we're still in btw) are all at play here. Film, especially Black film, is in retreat right now. The best we can do at this moment is be torch bearers of our lineage. I always feel like I'm mopping the ocean but every now and then a legend messages me a thank you or a new subscriber shows their appreciation.

In this climate of "Black firsts" (well firsts in white spaces) it's good to see you articulate how you want to build on the past. Being the Black 101st means that despite colonialism and slavery and Jim Crow and prison and everything else, nothing can stop the force of the Black camera and that should be honoured and celebrated.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Panel Presentation: "Telephone" and "Thot Shit"

youtube

“TELEPHONE” LADY GAGA & BEYONCE

In Lady Gaga’s “Telephone” (ft. Beyonce) music video, she centers two women criminals, half of the video taking place at a women's prison and the other half following the homicide the women (played by Gaga and Beyonce) set out to commit. The first striking thing about the video is the immediate use of women’s bodies. All the women in the prison are wearing revealing outfits, even the women security guards. As Gaga walks down the cells, the fellow prisoners (all female-presenting) hoot and holler and as character is thrown into her cell, the guards promptly rip off her clothes. This is an example of the use of a woman’s body that is not centering the male gaze. While a male gaze still may derive pleasure from the revealing costumes in the video, these characters are not necessarily designed to be seen as sexy by the male spectator. In Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” she writes that media depictions of women in a patriarchal culture stand as a signifier for the male other - meaning that women characters are present to engage with the male fantasy (1). While most of the women in the music video are partially nude or in revealing costumes, they are not doing so in a sexual nature. Their nudity and sexuality isn’t aiming to please men but to claim their own sexual identity. Mulvey also touches on how women’s bodies in “alternative cinema” can be also a radical or political aspect that challenges the basic assumptions of mainstream media, instead of just being objects for pleasure (2). Women’s bodies are shown in “Telephone” in different ways than usual music videos – there is more of a diversity in beauty and a roughness to them – these bodies are asking to be looked at.

In hooks’ “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators,” she writes about the “right to gaze.” Specifically, she references: “the politics of slavery, of racialized power relations, were such that the slaves were denied their right to gaze” (3). In these racialized power relations, she writes that Black people were not permitted to engage in the same freedom of watching, entertainment, or deriving pleasure from what they were seeing. This structure ultimately permeates to this day, as hooks writes that of the Black women she spoke to, none were excited to attend the movie theaters, knowing they would not be properly represented (4). How “Telephone” works in contrast with this trend is allowing spectators to look at and derive pleasure from the woman’s body. The idea of the oppositional gaze is a major part of the video because it challenges the ideas of dominant images that women must conform to. The video’s way of resisting the hegemonic gaze was to place the power into the hands of the women characters and for their bodies and strength to be shown without comparing it to that of a male character. hooks references Manthia Diawara to talk about the power of the spectator: “Every narration places the spectator in a position of agency; and race, class and sexual relations influence the way in which this subjecthood is filled by the spectator” (4) (309). Each person, specifically women, watching this music video could feel a sense of agency after experiencing women characters having power over their own bodies.

On the topic of bodies, the music video employs a semi-diverse cast of women in the video (the majority of women in the video are still white). Specifically, a lot of the women have stark differences about them like ethnicities, age, or sexual identity. In Audre Lorde’s “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” she writes that emphasizing differences is usually taught to be bad or ignored, “or to view them as causes for separation and suspicion rather than as forces for change” (5). In “Telephone,” the differences between these women in prison or Beyonce and Gaga as criminals is distinctly outlined. It is unclear with what Gaga and the writers of the video were trying to accomplish with the “outsider-ness” of the characters in the video – if they were trying to make them look bad or powerful –but one could argue that these women could fit into the archetype of rebels, not caring about society’s rules for them, and that would empower the viewer. It could also be argued that these women are represented by a stereotype of women in prison: violent, erratic, and their homosexuality coming off as predatory and creepy. Mulvey references those who have stood “outside the circle of this society’s definition of acceptable women; those of us who have been forged in the crucibles of difference” (6). “Telephone” puts examples in its video of women on the “margins of society,” but their purpose of being there is unclear to the viewer.

Questions:

Do you think that the other women in the video are meant to be powerful or other-ed, just perpetuating a stereotype?

Do you think “Telephone” practices using the “oppositional gaze”?

How do you think the sexual nature of woman characters in the video differs from other media depictions we have seen?

youtube

“THOT SHIT” MEGAN THEE STALLION

At the beginning of the “Thot Shit” music video, the character of the senator is shown leaving a hate comment on one of Megan’s former music videos (“Body”). When he receives a phone call from Megan she tells him “the women that you are trying to step on are the women you depend on. They treat your diseases, they cook your meals, they haul your trash, they drive your ambulances, they guard you while you sleep. They control every part of your life. Do not fuck with them.” This quote is then the theme for the rest of the video. As the senator tries to escape, Megan and her dancers have taken over every occupation and are dancing in his face. Something interesting in this video is the idea of scopophilia that the senator is taking part in. While he is at first closing his blinds and leaving hate comments before gazing, now Megan and her dancers are forcing him to look, owning their image. Mulvey writes about scopophilia in media/cinema, especially tasteful/pleasurable looking (7). While so much of scopophilia in mainstream media is about privacy and what’s “implied,” it could be argued that Megan is subverting the narrative by using her body and her dancers’ bodies freely and without concerns of what is “forbidden.” It could be seen as an act of agency.

hooks herself may argue that “Thot Shit” is an example of Black women having that sense of agency – the Black women throughout the video have multiple careers while also having the freedom of sexuality. She writes: “Spaces of agency exist for Black people, wherein we can both interrogate the gaze of the Other but also look back, and at one another, naming what we see” (8). This quote encapsulates “Thot Shit” perfectly: a place that Black people can exist freely while also interrogating the gaze of the other. The music video is special because it is a way that Megan celebrates Black women but also the integral part that Black women play in society. They are portrayed as critical parts of a working society but also they dance in the video, owning their sexuality. The sexual nature of the women in the video ties to another example of hooks’ writings about Black women in film/media: the absence “that denies the 'body' of the Black female so as to perpetuate white supremacy and with it a phallocentric spectatorship where the woman to be looked at and desired is ‘white’” (9). hooks writes that too often Black women have been denied ownership and agency over their own bodies, but also the ability to be desired by white phallocentric audiences. By using the character of the senator, they show the inherent racism imposed against Black women - people criticize them but then still sexualize them. Something important to mention is Megan’s lyricism in this song - the word “thot” was coined in the hip-hop world as a derogatory term for a woman, similar to the word “slut,” “with added derision for being working class” (10). The reclamation of this term is outright powerful because it is using a word that has been weaponized against Black women for years and she repurposes it to be something powerful. This subversion in itself can be tied to the work of the oppositional gaze - taking something used to oppress Black women and flipping it to empower them instead.

Rarely in popular media as big as “Thot Shit” do viewers see something with such a clear message. Megan does include a lot of Black female empowerment throughout her music and music videos, especially through sexual agency. Lorde writes, “Black women and our children know the fabric of our lives is stitched with violence and with hatred, that there is no rest. We do not deal with it only on the picket lines, or in dark midnight alleys, or in the places where we dare to verbalize our resistance. For us, increasingly, violence weaves through the daily tissues of our living … ” (11). “Thot Shit” is a form of protesting against the dehumanization and oppression of Black women in mainstream culture. Megan consistently brings Black women into the cultural conversation when they are neglected. Her empowerment is similar to that Lorde writes of: “It is learning how to stand alone, unpopular and sometimes reviled, and how to make common cause with those others identified as outside the structures in order to define and seek a world in which we can all flourish” (12).

Questions:

What are other ways that “Thot Shit” practices scopophilia and voyeurism in nuanced ways?

How is the video different from other music videos you have seen before?

How does “Thot Shit” work in conjunction with “Telephone”?

Works cited:

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” in Film Theory and Criticism, 712. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009)

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” 712

hooks, bell, “The Oppositional gaze: Black Female Spectators” in Feminist Film Theory, 307. (New York: New York University Press, 1999)

hooks, bell “The Oppositional gaze: Black Female Spectators.” 310

Lorde, Audre. "Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference." In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, 112. Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 2007

Lorde, Audre “Age, Race, Class and Sex: Women Redefining Difference.” (112)

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.”

hooks, bell, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.” 308

hooks, bell, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.” 310

O’Neal, Lonnae, “I had a thot but didn’t know it was a thing” The Washington Post, March 19, 2015

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” 119

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” (112)

@theuncannyprofessoro

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Malik Sidibé Photographs

interview by André Magnin, essay from Manthia Diawara

Hasselblad Center / Steidl Gottingen 2003, 113 pages, 30,5x30,5cm, ISBN 3-88243-973-4

euro 140,00

email if you want to buy [email protected]

Published to commemorate Malick Sidibé's reception of the 2003 Hasselblad Foundation International Photography Award; the first time the honor was conferred upon an African photographer. Featuring 65 full-page black-and-white plates, reproducing Sidibé's photography; mostly portraits and party photos, from the late '60s through the early '80s. Accompanied by an interview of Sidibé by André Magnin, and essay from Manthia Diawara on the influence of both Black Power and James Brown on the culture of Sidibé's hometown of Bamako, Mali.

"Malick Sidibé documented an important period of West African history with great commitment, enthusiasm, and insight, focusing on Malian youth in the 1950s and 60s. His portraits and documentary photography captured the unique atmosphere and vitality of an African capital in a period of great euphoria. From the earliest days of the postcolonial period, Sidibé was a privileged witness to a period of tremendous, euphoric cultural change. As a young but well thought-of photographer, he captured a time of paradigm shift and youthful insouciance with a healthy curiosity about the rest of the world, and a valiant sense of pride and confidence in the future. Sidibé learned the basic skills of studio photography as an apprentice before he began making reportage photographs. Since then, he has been devoted to photography. His portraits and documentary photographs, from the late 1950s to the mid-1970s, now bear witness to the cultural and social development of post-colonial Mali. We see joy, hope, beauty, and power in these psychologically captivating images. Sidibé's work, originally intended for an African audience, is a unique memoir and testimony for a world audience."

25/10/24

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Film still of Edouard Glissant in the documentary Édouard Glissant: One World In Relation (2010), dir. Manthia Diawara. Subtitle reads: "Empires collapse, and empires aren't eternal."

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

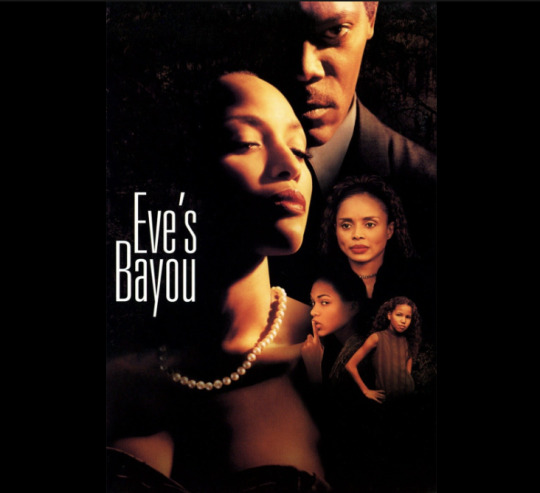

Critical Film Analysis: Eve's Bayou (1997)

In Black Spectatorship: Problems of Identification and Resistance, Manthia Diawara hones in on the racial inequalities present within the Hollywood film industry. Because Hollywood and other major media outlets are so heavily dominated by whiteness, there are a wide range of films that speak to the white experience. This creates an obvious disparity between the viewing experience had by white people, and those who don’t see themselves accurately reflected on screen. Diawara speaks on the idea of spectatorship, which encompasses the perception, interpretation, and social context of the respective viewer. Spectatorship changes as the spectators lived experiences shape their understanding of the world. Diawara notes that there is a pleasure in identification through spectatorship. Those whose identities are reflected on screen, are able to achieve a higher sense of enjoyment through television. This, however, is not commonly afforded to Black spectators, who receive only a sliver of representation. “And at the level of spectatorship, the Black spectator, regardless of gender or sexuality, fails to enjoy the pleasures which are at least available to the white male heterosexual spectator positioned as the subject of the films' discourse”(771). Black people, time and time again, are forced to bare witness the misinformation that their lives are given in film and television. Because of this, the term “resisting spectator” emerged. The idea of resistant spectatorship implies that viewers have the ability to reinterpret, reimagine, and resist on-screen portrayals, rather than passively accept them. Viewers are made to actively question, challenge, and resist the ideologies presented in the movie in order to reimagine widely perpetuated, though harmful, norms. Black people who do not resonate with the painting of Blackness in television, embraced the ability to critique, and even create. As this oppositional form of spectatorship grew, as did creative experts’ efforts to reflect this resistance on screen. Diawara states that “resisting spectators are transforming the problem of passive identification into active criticism which both informs and interrelates with contemporary oppositional film-making. The development of Black independent productions has sharpened the Afro-American spectator's critical attitude towards Hollywood films” (775). The emergence of all Black productions worked to combat Black spectators’ desensitization to wrongful depictions of Blackness, and urge positive representation to become the new norm. Eve’s Bayou is a 1997 film that practices being unapologetically Black through its all Black cast, and its devotion to exploration into Black girlhood and family life, through a lens unfiltered by whiteness.

Eve’s Bayou (1997), is an American horror/drama written and directed by Kasi Lemmons. The film follows 10 year old Eve Batiste and her family in their affluent Creole-American community in 1960s Louisiana. The story is shown through Eve’s perspective, as she witnesses events that start to unravel the secrets and complexities of her family. Being told from the lens of Eve, a young Black girl, makes the film a pertinent example of the rejection of the white gaze in media. In bell hooks’, Black Looks: Race and Representation, hooks engages with the concept of “the gaze”, particularly in the context of Black women. She introduces the notion of the "oppositional gaze," which is a gaze that challenges and resists the dominant, often white, male gaze. A gaze that is both male and white can not accurately capture the experience of those outside of themselves, especially that of Black women. Black women have been subjected to being represented only through the gaze of others, often having to act out stereotypical tropes on camera. Eve’s Bayou, however, allows the narrative to be constructed by actual Black people, bringing more truth to the Black experience than predominantly white films do. The film opens with shots of the the town in which Eve’s family lives in, paired with her own narration, explaining the origins of the land. She states that the town was named after an enslaved woman named Eve, who saved the life of General Jean Paul Batiste, and was freed, and granted their piece of land in return. The setting of the film itself is already indicative of how it aims to shed a different and less stereotypical light on Black life. Oftentimes within media, especially during the late 20th century, Black people were portrayed as being limited to the slums of urban environments, and prosperous Black communities in rural surroundings went unrepresented. This scene contradicts the way of life that the white gaze has created for Black communities, and places Black bodies in a setting where they are traditionally not ‘supposed’ to be. The first glimpse we get of the characters is at a party in the Batiste’s home. The mise-en-scene work to highlight the elevated status of the Batiste family, and their extended community. There is dancey background music, their home is nicely decorated, and everyone is dressed in finery. Not to mention, all of the attendees are Black, displaying a range of skin tone, hair color, gender, and age. The film strays away from tokenism, and embraces the variety of Blackness through its characters.

Though Eve’s Bayou is centered around the supposed dazzling Batistes’, the film hones in on the dark, uncomfortable, and sometimes supernatural reality of the family, unraveling a tale of mysticism, secrets, and complexities of human relationships. The film is a Southern Gothic, which is substantiated by its taking place in the Louisiana bayous, on land that was once used for enslavement. Lemmons masterfully employs elements of voodoo and folklore, interwoven with psychological horror, to construct a narrative that is both eerie and thought-provoking. Unlike other predominantly Black horror films, Eve’s Bayou does not use racism and poverty, as the terror for all Black people. The film's horror is deeply rooted in the personal and familial struggles of the characters, transcending the racial boundaries seen in traditional, hegemonic plot lines. The Batiste family must grapple with consequences of choices made, and the haunting specters from the past, neither of which rely on their Blackness. Eve’s Bayou serves as a poignant example of a story told from the Black female gaze, one that focuses on the intricacies of human life, but through bodies that are Black.

Works Cited:

Hooks, Bell. Black Looks: Race and Representation. Routledge, 2015.

“Black spectatorship: Problems of identification and resistance: Manthia Diawara.” Black American Cinema, 2012, pp. 217–226, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203873304-20.

0 notes

Text

Posted @withregram • @amy_sall Apropos of it all, empires must fall.

Leaders of the imperial core, the formerly colonized nations that perpetuate imperial harm, and nations that place profit + power over people, will have to reckon with their moral depravity.

Love and salvation to Palestine, Congo, Haiti, Sudan, Tigray, to the migrants, the asylum seekers, the displaced, the dispossessed, the disenfranchised, the self-determining, ++++

———

Film still of Édouard Glissant in the documentary Édouard Glissant: One World In Relation (2010), dir. Manthia Diawara. Subtitle reads: “Empires collapse, and empires aren’t eternal.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

First African film by an African

Below is the first African film made by an African: the Senegalese film director Ousmane Sembène who is also regarded as the father of African cinema. Archived along with the film is Manthia Diawara's remarkable analysis of it.

0 notes

Text

Back in ‘22 Manthia Diawara exhibited Towards A New Baroque of Voices at Amant Gallery. I think it had footage of this interview? the whole thing was a compilation of footage Diawara had shot over the years and included some clips from various docs he made that were left on the cutting room floor, including from Sembène: The Making of African Cinema wherein Singleton interviewed Sembène.

I’m full of contradictions. Manthia asks me that all the time, and I don’t know how to answer. I assure you, I have no secrets, but I don’t like to explain anything. OK, I use Marxist dialectics to try to understand the walk of the individual within a community. The dynamics of Marxist economic theory are very important to creating this complexity. Man needs to eat, but did he produce what he’s eating or did someone else? These are questions that arise when I’m writing. There is a proverb in Bambara that says, “If you manage to eat for a whole year without touching your wallet, it’s because you are living in someone else’s pocket.” So when you’re in contact with a man like that, you have to describe his whole mentality as well as the society surrounding him, to understand how he thinks. That’s how I proceed.

Ousmane Sembène, Ousmane Sembene by John Singleton and Reginald Woolery, Spring 1993 issue

92 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Manthia Diawara | Sembène | The New York Times

14 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Let us never forget: that the poem was entombed in a collapse of the earth. By habit, rather than commodity, the singularity and multiplicity of things were presented as divided couples and dualities, before the genres and species were discovered. This cadence allowed for a better distinction between things (we still think and react in this dual manner, and often take a surprising pleasure from it). But we’re also waiting for the renewed perception of differences to reveal themselves as such, and for the poem to reemerge once more.

Édouard Glissant, Philosophie de la Relation, p. 15. Translated by the Manthia Diawara.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you're in the city anytime between 20 nov and 30 jan you gotta check this out!

This new Diawara joint is a compilation of interviews and conversations he's recorded over the years. Of particular note is Velma Bury showing David Hammons rare photos of black americans in paris (and Hammons' shady ass reading Basquiat 🤣); Ousmane Sembène mentoring John Singleton 🥲; and Marlyatou Barry reflecting on her relationship with Kwame Turé.

In this era of black excellence highlight reels which are no more than ink blot tests or choose your own adventure meaning movies, it's so refreshing seeing a principled and intentional work by an academic! And with so many pillaging the archives over the last decade it's very special to see someone sharing bits of their own archive on their own terms.

ngl tho Amant is a shady money laundering front moreso than a gallery. very sketchy. so be careful

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The female image upholds patriarchal ideology in visual media by reaffirming the power of the phallus, which occurs through symbolic gestures throughout the medium. Mulvey identifies these two actions: “she first symbolises the castration threat by her real absence of a penis and second thereby raises her child into the symbolic.”(1) The woman’s presence in physical opposition to the man is a threat to his masculinity, and then the product of the women’s existence in the film is used to reaffirm the power of said masculinity. All viewers are satisfied by the male gaze due to the innate scopophilic nature of film. Mulvey writes that “looking itself is a source of pleasure,”(2) showing that each and every audience member derives a default pleasure from viewing subjects in films. She also claims that cinema itself “implies a separation of the erotic identity of the subject from the object onscreen (active scopophilia),”(3) which in turn objectifies the character displayed. This allows viewers to insert the visual subject into their imagination and derive pleasure from any circumstance presented to them. Through the application of these ideas, film has been used as a tool to objectify women for the satisfaction of the male gaze.

Racial and sexual differences between viewers influence their perspective on visual pleasure due to the historical and social implications of their looking. bell hooks quotes Manthia Diawara’s claim that “race, class and sexual relations influence the way in which this subjecthood is filled by the spectator.”(4) Through different perspectives on the subject, audience members of different backgrounds identify with the subject in unique ways, causing variations in their experiences of pleasure in regards to the events that occur to the subject onscreen. The oppositional gaze empowers viewers by giving them agency over their own visual perspective, allowing them to shape their own relationship with the medium through their look. hooks writes about the oppositional gaze, describing that “By courageously looking, we defiantly declared: 'Not only will I stare. I want my look to change reality.'”(5) This quote exemplifies the power that marginalized people are able to attain through the oppositional gaze, redefining the way they relate to subject and narrative on screen. While circumstances of oppression have motivated groups to avert their gaze, the oppositional gaze gives them the opportunity to look on their own terms.

Bibliography:

1 Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” in Film Theory and Criticism (New York: oxford University Press, 2009), 712

2 Mulvey, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, 713

3 Mulvey, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, 715

4 bell hooks, “The Oppositional gaze: Black Female Spectators” in Feminist Film Theory (New York: New York University Press, 1999), 309

5 hooks, The Oppositional gaze, 308

@theuncannyprofessoro

Reading Notes 7: Mulvey to hooks

Shifting our visual analysis and critical inquiries to gender and sexuality, we will begin our explorations with Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” and bell hooks’s “Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.”

How does the spectacle of the female image relate to patriarchal ideology, and in what ways do all viewers, regardless of race or sexuality, take pleasure in films that are designed to satisfy the male gaze?

How do racial and sexual differences between viewers inform their experience of viewing pleasure, and in what ways does the oppositional gaze empower viewers?

@theuncannyprofessoro

17 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Manthia Diawara - "Edouard Glissant: A Demand for the Right of Opacity"

August 2019, European Graduate School

4 notes

·

View notes