#maclean's magazine

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"During the winter of 1918–19, Ottawa was rattled by the extreme rhetoric it was hearing from some of the country’s labour leaders. Police spies were sending in alarmist reports that unions were seething with revolutionary discontent. In response, the government set in motion a campaign of counter-propaganda to discredit the Reds. Chief press censor Ernest Chambers routinely fed information gleaned from police reports to members of the print media. Chambers kept his eyes peeled for anti-Red articles in the daily press so that he could dash off a letter offering the author more inflammatory information about the present danger. He did his best to orchestrate a comprehensive propaganda campaign, involving the press, university professors, service clubs, churches, even movies, all fuelled by information of the right type provided by his department. In January he wrote to the presidents of several major universities asking that they makes speeches or write articles exposing the fallacies of “extreme red Socialism and Bolshevism.” At the same time, he warned against revealing the existence of this anti-Red campaign. “Were the agitators conducting this propaganda able to plead that they are being made the subject of organized attack,” he wrote the president of the University of Toronto, Sir Robert Falconer, “it would aid them tremendously in their campaign with the disaffected.” (Falconer wrote back declining the invitation to take part in Chambers’ campaign: “If prices could be kept down and employment could be assured,” he told the censor, “I think many of our immediate troubles could be quickly surmounted.”)

The kind of information Chambers wanted to disseminate could be found in the Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs, published by J. Castell Hopkins, a prolific author of popular biographies and encyclopedias. Hopkins’ portrait of the Soviet Union under Bolshevik rule exemplified the mixture of misinformation, fear, and smug middle-class superiority which fuelled anti-Red hysteria in Canada. “In Russia,” he told his readers, “disorganization, starvation, individual license, robbery, brutal crime, the over-throw of social laws and religious influence and ordered government, wholesale immorality, were natural products of the rule of men who were ignorant of all but wild theories nursed in malignant or disordered minds.” For Hopkins, Bolshevism simply meant “wholesale pillage and the murder of the classes owning money or property.” Things were better under the tsars, he said; at least the Romanovs were honest and meant well. The Bolsheviks were terrorists who roused the basest instincts in the Russian masses and rode them to power. Life in Russia, he told his readers, had become a living hell. There was no free speech, no democracy, no private property, only terror, mass executions, and torture,

including mutilations of all kinds, slow starvation, burning alive, piercing with bayonets [...], deliberate breaking of arms and legs, stamping on wounded living bodies with hob-nailed boots, nailing officers’ shoulder straps to their bodies, thrusting of gramophone needles through finger nails, blinding in most brutal forms.

Hopkins’ list of bizarre atrocities was reminiscent of the most extreme anti-German propaganda during the war, now turned against a new enemy, the Bolshevik.

Implicit in Hopkins’ overheated prose was a warning to his Canadian readers: This could happen here. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and other socialists preached a form of class warfare every bit as frightening as their Russian counterparts, he said. Working under the cover of the One Big Union and organizations such as the Social Democratic Party, they intended to destabilize the economic situation with general strikes and exploit the chaos to seize power from the government. According to Hopkins, this was no theoretical danger. “At the end of 1918 there were 21 Soviets established in the country awaiting for action,” he announced, without any evidence whatsoever.

One powerful institution that shared the concern about the insidious threat of Bolshevism was the Canadian Pacific Railway. In the fall of 1918, John Murray Gibbon, CPR publicist, broached the subject with filmmaker George Brownridge. Gibbon was one of the country’s leading intellectuals. A graduate of Oxford University and an experienced journalist, he had joined the CPR’s London operations in 1907 and had moved to the company’s Montreal head office just before the war. He was not only an ambassador for the railway but, as author and festival impresario, he was an energetic promoter of Canadian culture as well. The CPR had a problem with Bolsheviks stirring up its workers, Gibbon told Brownridge, and he thought that the film industry could do something about it. During the war Brownridge had established a studio, Canadian National Features, in Trenton, Ontario, where he managed to make two feature films before going broke. Neither of those films was ever released, but the indefatigable Brownridge was back in business at Trenton two years later as the Adanac Producing Company (the name is Canada spelled backwards) and eager to attract corporate support from the likes of the CPR.

After talking to Gibbon, Brownridge, armed with a suitable script about a Red plot to take over a trade union, came back to the railway for financial help. Eventually the CPR and several other large employers did put up the money. CPR president Edward Beatty made his position clear in a letter that he wrote to journalist and president of the Canadian Reconstruction Association, John Willison.

Of course there can be no doubt that from one end of the country to the other an effort must be made to stamp out this extreme socialism which practically amounts to disloyalty…

Brownridge began work on his film, called The Great Shadow and starring Tyrone Power Sr. The film was directed by Harley Knoles, who had just completed another anti-Red feature in the United States called Bolshevism on Trial co-starring his Canadian-born wife Pinna Nesbitt. The final script of the new film included most of the elements of Red Scare melodrama: vicious Bolsheviks determined to destroy society by setting one class against another; a handsome secret service agent to provide love interest; a fairminded employer who only wants what is best for his workers; and a “responsible” labour leader who must wage a life-and-death struggle to keep his union free of extremism. The Great Shadow was one of several Red Scare features to appear at this time in Canada and the US. The newest forms of popular entertainment were not ignored when it came to combatting the threat of Bolshevism. The film was finished too late to influence opinion during the crucial spring of 1919, but when it did reach the screen in the late fall it met with widespread critical praise. Unfortunately, no copy has survived.

Another busy scaremonger was Charles Cahan. In January Cahan, whose extreme views had managed to alienate most of his support in the federal Cabinet, resigned from his job as director of public safety. He had failed to convince the government to create a secret service modelled on the American Bureau of Investigation, and with his departure the entire Public Safety Branch was abolished after just three months in operation. In a letter to Prime Minister Borden, Cahan explained that,

I tried in vain, after your departure [for Europe], to obtain a hearing from your colleagues; but they treated my representations with such contemptuous indifference, that there was for me no alternative but to retire quietly and await events.

In Cahan’s view, the ultimate aim of the “Reds” was to “kick the Government off Parliament Hill.”

Cahan had no intention of retiring quietly; far from it. He continued to speak out at every opportunity about the Bolshevik threat, and one of his speeches, “Socialistic Propaganda in Canada,” was printed as a pamphlet and had wide distribution. In it, he summarized the four main doctrines of “International Socialism” as he understood them. First of all, class warfare between workers and capitalists caused “envy and hatred of all who have acquired property of any kind whatsoever.” Second, the state acquired ownership of all means of production and responsibility for all social relationships. Third, only the interests of workers had any importance. And last, the capitalist class was stripped of all possessions. Propaganda in favour of these views was flooding the western world, said Cahan. In Canada it was mainly the IWW that was fomenting class warfare, especially among the large “alien” population. If this was allowed to continue, he warned, there would be “tumults and disorders” that would require the intervention of the army. He suggested denying the right to strike, keeping a watchful eye on labour organizations and the foreign-language press, restricting immigration, and the speedy acculturation of immigrant children in the schools. Cahan’s basic message was that anyone who accepted the concept of class differences was contributing to a civil war in Canada that threatened democratic institutions and individual liberties.

Cahan carried his campaign to the pages of Maclean’s magazine. Under the ownership of Colonel John Bayne Maclean and the editorship of Thomas Costain, this magazine had become a major organ of the Red Scare. Cahan sounded his familiar warning about the IWW and other “Red” elements who were spreading “pacifist, socialistic, revolutionary and seditious literature” and organizing “societies for the insidious propagation of doctrines destructive of our existing political, social and industrial institutions.” He revealed that these activities were funded by thousands of dollars provided by agents of the Russian government, and he even hinted that the conspiracy to overthrow the government reached into the corridors of power in Ottawa. In the absence of Borden (in Europe), he wrote, the cabinet had been “utterly lacking in unity of purpose and in courageous action.” In case after case, Cahan claimed, federal authorities had intervened to secure the release of agitators who had been arrested for their activities. And, of course, had he not been removed from any position of influence under suspicious circumstances?

Colonel Maclean was an enthusiastic proponent of conspiracy theories. A long-time member of the militia, he had encouraged the government to take a hard-line, anti-Hun, anti-pacifist approach during the war. At the end of 1918, he wrote in his magazine that the Germans, had they won the war, had plans to dismember Canada and distribute parts of it to their leading bankers, nobles, and businessmen. Quite literally, therefore, the Canadian army had saved the country from extinction; it only made sense, wrote Maclean, to put the army in charge of society now that the war was over. He recommended, for instance, that military men take control of the school system. “It makes one dizzy to think of the great things that could be accomplished,” he wrote.

The January 1919 edition of Maclean’s carried an article titled “Is Bolshevism Brewing in Canada?” to which the author, Thomas Fraser, answered with an emphatic “Yes.” The magazine had commissioned Fraser to discover if Bolshevism was present in Canada. His conclusion: “There is a bold, systematic and dangerous effort being made to lay the fuse of Bolshevism from one end of the Dominion to the other.” The IWW was behind it, he explained. “Their idea is to seize control of all industries and abolish the wage system.” Their aims were completely hostile to democracy, Fraser warned, and to the middle class. The “root of the whole matter” was that “much of the good old Anglo-Saxon stock” was gone, slaughtered in the recent war, and Canada was filled up with “workmen of foreign extraction” sympathetic to Bolshevik propaganda.

One appreciative reader of Fraser’s article was press censor Ernest Chambers. He wrote Colonel Maclean a congratulatory note in which he warned that “the situation is very much more dangerous, in my opinion, than the public has the least conception of.” Encouraging Maclean to continue to raise the alarm, he concluded:

I am firmly convinced that, without the real solid, sensible people of the country taking into their own hand the active combatting of this Bolshevist propaganda, we run the risk of reaching, within measureable time, the conditions which at present prevail in Russia.

Among the more extreme anti-Red fanatics, a rationale seemed to be emerging that justified taking the law into their own hands to preserve the nation from revolution.

In the June 1919 issue of his magazine, Maclean himself took Chambers’ advice. In a provocative article titled “Why Did We Let Trotzky Go?” he blamed unnamed “politicians or officials” in Ottawa for allowing Trotsky to leave his Amherst internment camp and return to Russia to lead the revolution there. Trotsky, claimed Maclean, was a German agent paid to take Russia out of the war. If Canada had held onto him, the war would have been shortened by a year. This was a familiar belief at the time, but Maclean went further. He claimed that Trotsky had organized groups of revolutionaries in Toronto and Ottawa who were poised to take over the country. Charles Cahan had revealed some of this threat, wrote Maclean, but then “the Trotzky influences got busy and Mr. Cahan was ordered to cease his inquiries and send in his resignation.” (Despite the allegations of Cahan and Maclean, no evidence was ever produced that Leon Trotsky had supporters within the Canadian government who were twisting its policies in his favour.)

By the August issue, Maclean was getting even more alarmist. By then, of course, the Winnipeg General Strike had taken place. Not surprisingly, Maclean’s saw it as a prelude to revolution. The Bolsheviks were pouring money into the country to cause strikes and encourage social unrest, the Colonel wrote. It was all a conspiracy organized by the Germans and their Russian Bolshevik agents to disrupt western countries so that Germany could rebuild its economy and regain its markets. For Maclean, and for many others, the Hun and the Bolshevik were indistinguishable. In their view, the war was still going on and it was being fought in the streets of Winnipeg and other Canadian cities."

- Daniel Francis, Seeing Reds: the Red Scare of 1918-1919, Canada’s First War on Terror. Arsenal Pulp Press, 2011. p. 58-62.

#world war 1 canada#red scare#world war 1#canadian history#suppression of dissidents#seditious literature#canadian socialism#anti-communism#working class struggle#what the ruling class does when it rules#seeing reds#reading 2024#research quote#canadian veterans#xenophobia in canada#public safety branch#russian revolution#leon trotsky#winnipeg general strike#maclean's magazine#reactionary politics#industrial workers of the world#one big union

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

ELLA PURNELL ELLE's Rising Stars 2024

#ella purnell#ellapurnelledit#epurnelledit#womenedit#falloutedit#fallout#lucy maclean#falloutcastedit#yellowjacketscastedit#yjcastedit#yellowjackets#usershelby#userhann#userbru#useremz#userlindsay#userladiesblr#userladiesofcinema#elle magazine#elle#femalestunning#femalegifsource#chewieblog#userbbelcher#userstream#brunettessource#gifset#actoredit#my edit

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

FALLOUT - First Scene

#falloutedit#foedit#tvedit#fallout prime#fallout#lucy maclean#the ghoul#cooper howard#ma june#long post#mine#gif:mine#gif:fallouttv#i loooved this#also watching this last night for the first time i spotted that hot rodder 1 flame job magazine from fo4 immediately. im not normal i know#the laser rifle sign? cute. the implication of that caps only sign? interesting. those iguanas getting smoked on their sticks? delicious

759 notes

·

View notes

Text

Smoother, Longer, Lasts Forever...

Benson & Hedges, 1972

#70s ads#cigarette ads#innuendo#1970s#70s#benson & hedges#1972#seventies#70s advertising#vintage ads#vintage advertising#tobacco ads#70s clothing#70s hair#70s couples#magazine ad#macleans magazine#canada#smoking is hazardous to your health

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maclean's, magazine, Vol. 80, N. 11, Maclean-Hunter, November 1967

#witches#college students#occult#vintage#magazine#maclean's#maclean-hunter#vol. 80#n. 11#november 1967#1967#canada#campus '67

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

GOSHSHEISSOPRETTY❣️😍

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

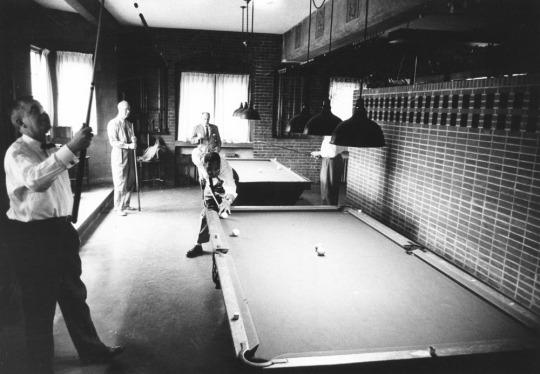

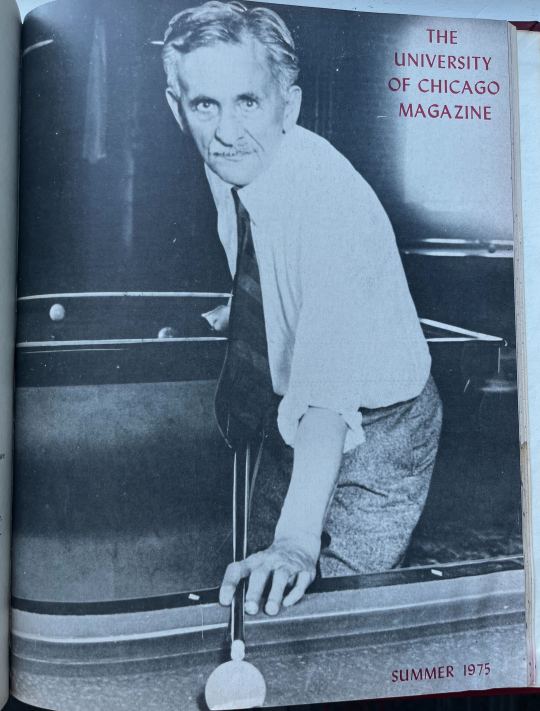

Want more Norman Maclean, PhD’40? Read his reflections on Nobel laureate and UChicago physics professor Albert A. Michelson and gamesmanship, from our Summer 1975 issue.

Archival photo: University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf2-06092r, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library

#uchicago#university of chicago#alumni#campus#chicago#university of chicago magazine#archives#photography#magazine#billiards#norman maclean#albert michelson#physics#1975

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alex MacLean | Aesthetica

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

#rolling stone#rolling stone magazine#the fortieth anniversary#victor moscoso#lee conklin#rick griffin#stanley mouse#alton kelley#gary grimshaw#wes wilson#leidenthal#bonnie maclean

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#mccain#Schneiders Deli Meats#adobe#branding#design#infographic#wonder bread#video games#youtube video#vedio#McGregor Socks#del monte#provincial government#federal government#federal employees#provincial employees#lgtbq community#jewish tumblr#christian tumblr#elle magazine#Macleans Magazine#flair airlines#air canada#boeing#mcdonalds#Reitmans#dollarama#dollar tree#Max Factor#Revelon

1 note

·

View note

Text

1966.

Maclean's Magazine trashes Disney's Winnie the Pooh

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

ELLA PURNELL Photographed by Thomas Whiteside for Interview Magazine, April 2024

#ella purnell#epurnelledit#ellapurnelledit#falloutedit#fallout#yellowjacketsedit#womenedit#dailywomen#femalestunning#userbru#userlindsay#userhann#usershelby#userbecca#useremz#lucy maclean#yellowjacketscastedit#yjcastedit#userladiesofcinema#useroptional#userstream#userbbelcher#chewieblog#interview magazine#actoredit#my edit

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

In Green Waves / Ruairidh MacLean

In Green Waves, by Ruairidh MacLean is one of three winning stories from 3d Wednesday’s annual flash fiction contest. Contest judge, John F. Buckley said, this tale of appetites and silence artfully charts an entire lifetime, from conception to death, without seeming either rushed or glib.You can read it HERE or in the autumn issue of the magazine.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Stand Out in a Crowd Without Even Trying...

#1970#1970s#70s#seventies#70s ads#70s advertising#vintage ads#retro ads#70s fashion#1970s fashion#70s menswear#rainshine#croydon#macleans magazine

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Their names are Geneva Robertson-Dworet and Graham Wagner and they know their shit when it comes to the games. It seems like they tried really hard to make something appealing for fans of the game first, and appealing to wider audiences second.

Robertson-Dworet also wrote Captain Marvel (one of my favourite Marvel movies) and the 2018 adaptation of Tomb Raider.

Wagner wrote for Silicon Valley and Portlandia, and wow does his comedic style show through.

They have a great interview with GQ that I recommend anyone who loved the series read. Side note - GQ has weirdly consistently amazing entertainment journalism. Their interview with Rob Pattinson is one of the funniest things I have ever read.

I'm actually astounded that Fallout seems to have avoided the curse of game to movie/tv adaptations being completely totally awful. I need to go research who was on the writing team so I can understand how they pulled this off. Also I need S2 yesterday.

12 notes

·

View notes