#lydias of Miletus

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#stealing Fire#in a mostly dramatic historical fantasy fiction#there are some banging comedic scenes#ptolemy#lydias of Miletus#some light hearse stealing#Alexander the Great#if I post enough someone will read this series and come talk to me#single handed making a new tag#I mean it’s a pretty hopepunk book#and song of Achilles had a moment#and this is like that but much more accessible and lots of action and adventure too

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

another quick vibe check but this time with colours

the chapter is mostly focused around corinth, but we have equal parts athens and sparta as supporting storylines so I wanted to kind of. shift the colours a little as we move around the ancient world to follow each story. Corinth has the main turquoise/cyan colour, Athens leans towards green, and Sparta leans towards indigo.

#athens and sparta adventures#aasa corinth#aasa megara#aasa athens#aasa ionia#aasa miletus#aasa greece#aasa sparta#aasa persia#aasa lydia#aasa sardis#hapo art#hapo doodles#aasa illustration#aph ancient greece#hws ancient greece

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Coinage

Coins were introduced as a method of payment around the 6th or 5th century BCE. The invention of coins is still shrouded in mystery: According to Herodotus (I, 94), coins were first minted by the Lydians, while Aristotle claims that the first coins were minted by Demodike of Kyrme, the wife of King Midas of Phrygia. Numismatists consider that the first coins were minted on the Greek island of Aegina, either by the local rulers or by King Pheidon of Argos.

Aegina, Samos, and Miletus all minted coins for the Egyptians, through the Greek trading post of Naucratis in the Nile Delta. It is certain that when Lydia was conquered by the Persians in 546 BCE, coins were introduced to Persia. The Phoenicians did not mint any coins until the middle of the fifth century BCE, which quickly spread to the Carthaginians who minted coins in Sicily. The Romans only started minting coins from 326 BCE.

Coins were brought to India through the Achaemenid Empire, as well as the successor kingdoms of Alexander the Great. Especially the Indo-Greek kingdoms minted (often bilingual) coins in the 2nd century BCE. The most beautiful coins of the classical age are said to have been minted by Samudragupta (335-376 CE), who portrayed himself as both a conqueror and a musician.

The first coins were made of electrum, an alloy of silver and gold. It appears that many early Lydian coins were minted by merchants as tokens to be used in trade transactions. The Lydian state also minted coins, most of the coins mentioning King Alyattes of Lydia. Some Lydian coins have a so-called legend, a sort of dedication. One famous example found in Caria reads "I am the badge of Phanes" - it is still unclear who Phanes was.

In China, gold coins were first standardized during the Qin Dynasty (221-207 BCE). After the fall of the Qin dynasty, the Han emperors added two other legal tenders: silver coins and "deerskin notes", a predecessor of paper currency which was a Chinese invention.

Continue reading...

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

One interesting connection between the Trojan royal family and the line of Tantalos is something that's spread out in various bits and pieces throughout several sources. It's only mentioned briefly in each of them too, but the general idea is pretty coherent.

To start with; in the Suda, a late variant of Ganymede's abduction (one of the two rationalizing accounts, the other one has Minos doing the kidnapping). Here it is Tantalos/a Tantalos (as he's called the king of Thrace, but that might just be one more variant of where Tantalos lives, since it wasn't very consistent, instead of being a different Tantalos from our famous one) who takes a fancy to Ganymede, after suspecting espionage when Ganymede is sent to sacrifice at a shrine to Zeus.

Next, the scattered mentions I talked of above; all touch on some sort of war(s) between usually Ilus and either Tantalos or Pelops, from Pausanias 2.22.3, Diodorus Siculus 4.74.4 and Dictys Cretensis 1.6.

Ilus, being cast as pious and aggravated by Tantalos' misconduct drives him out of his country (here Paphlagonia) in Diodorus - he's one of the rationalizing/realistic ones, so obviously Tantalos isn't here getting any divine punishments and instead Ilus is standing in as such. Pausanias and Dictys mention war between Ilus and Pelops (and Pelops driven out of Lydia). Dictys strangely has a little line that intimates the war between Ilus and Pelops was for a reason "similar to this one" - that is, the Trojan war, Helen being in Troy. There's no explanation for what that might mean, and nothing such is mentioned elsewhere.

So what you can get out of is this a generational conflict and, undoubtedly, resentment on the part of Pelops from being driven out of his native country. Even more usefully, it's a very neat explanation as for why Pelops settles in Pisa with Hippodamia instead of taking her to Sipylos/Lydia/Phrygia/wherethefuckever in Anatolia.

And even if the "Agamemnon is greedy and is using Helen in Troy as a pretext" is a modern invention, using these pieces of mythic "worldbuilding" as background it's very easy to add extra flavour to especially Agamemnon's (but why not Menelaos' as well?) reasons for going through with the war. Revenge, and to retake their hold in their ancestral homeland.

(I can tell you I have happily used this to pad out the geography/local mythical history for the Anatolian families, also using the historical connection of Miletus being Mycenaean as it being an attempt by Pelops to gain some ground on the coast that ultimately fails, with Miletus/Caria being firmly aligned towards its Anatolian neighbours.)

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yves here. One asset America has that most anti-globalists overlook is our legal and court system. The value of foreign exchange transactions due to investment flows was estimated by the Bank of International Settlements at 60 times that of transactions related to trade, although cross border capital flows collapse during financial crises.

Investors greatly prefer transacting though US institutions due to our well-settled precedents. Recall that multinationals investing in Russia as well as some Russian corporations, were often loath to invest directly. They would would go through Cyprus to be subject to English law and a court system run on UK lines. I’ve belatedly come to the view that the reason Cyprus banks blew up in 2013 and were not rescued was the power that be wanted to impede foreign investment in Russia.

That is not to say that US hegemony isn’t past its sell-by date, but that the idea that a new system will come into being soon is way way overdone. I’m of the Gramsci view:

The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.

By Michael Hudson, a research professor of Economics at University of Missouri, Kansas City, and a research associate at the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College. His latest book is The Destiny of Civilization.

Herodotus (History, Book 1.53) tells the story of Croesus, king of Lydia c. 585-546 BC in what is now Western Turkey and the Ionian shore of the Mediterranean. Croesus conquered Ephesus, Miletus and neighboring Greek-speaking realms, obtaining tribute and booty that made him one of the richest rulers of his time. But these victories and wealth led to arrogance and hubris. Croesus turned his eyes eastward, ambitious to conquer Persia, ruled by Cyrus the Great.

Having endowed the region’s cosmopolitan Temple of Delphi with substantial silver and gold, Croesus asked its Oracle whether he would be successful in the conquest that he had planned. The Pythia priestess answered: “If you go to war against Persia, you will destroy a great empire.”

Croesus therefore set out to attack Persia c. 547 BC. Marching eastward, he attacked Persia’s vassal-state Phrygia. Cyrus mounted a Special Military Operation to drive Croesus back, defeating Croesus’s army, capturing him and taking the opportunity to seize Lydia’s gold to introduce his own Persian gold coinage. So Croesus did indeed destroy a great empire, but it was his own.

Fast-forward to today’s drive by the Biden administration to extend American military power against Russia and, behind it, China. The president asked for advice from today’s analogue to antiquity’s Delphi oracle: the CIA and its allied think tanks. Instead of warning against hubris, they encouraged the neocon dream that attacking Russia and China would consolidate its control of the world economy, achieving the End of History.

Having organized a coup d’état in Ukraine in 2014, the United States sent its NATO proxy army eastward, giving weapons to Ukraine to fight an ethnic war against its Russian-speaking population and turn Russia’s Crimean naval base into a NATO fortress. This Croesus-level ambition aimed at drawing Russia into combat and depleting its ability to defend itself, wrecking its economy in the process and destroying its ability to provide military support to China and other countries targeted as rivals by U.S. hegemony.

After eight years of provocation, a new military attack on Russian-speaking Ukrainians was conspicuously prepared to drive toward the Russian border in February 2022. Russia protected its fellow Russian-speakers from further ethnic violence by mounting its own Special Military Operation. The United States and its NATO allies immediately seized Russia’s foreign-exchange reserves held in Europe and North America, and demanded that all countries impose sanctions against importing Russian energy and grain, hoping that this would crash the ruble’s exchange rate. The Delphic State Department expected that this would cause Russian consumers to revolt and overthrow Vladimir Putin’s government, enabling U.S. maneuvering to install a client oligarchy like the one it had nurtured in the 1990s under President Yeltsin.

A byproduct of this confrontation with Russia was to lock in control over America’s Western European satellites. The aim of this intra-NATO jockeying was to foreclose Europe’s dream of profiting from closer trade and investment relations with Russia by exchanging its industrial manufactures for Russian raw materials. The United States derailed that prospect by blowing up the Nord Stream gas pipeline, cutting off Germany and other countries from access to low-priced Russian gas. That left Europe’s leading economy dependent on higher-cost U.S. Liquified Natural Gas (LNG).

In addition to having to subsidize domestic European gas to prevent widespread insolvency, a large proportion of German Leopard tanks, U.S. Patriot missiles and other NATO “wonder weapons” were destroyed in combat against the Russian army. It became clear that the U.S. strategy was not simply to “fight to the last Ukrainian,” but to fight to the last tank, missile and other weapon being deleted from NATO stocks.

This depletion of NATO’s arms was expected to create a vast replacement market to enrich America’s military-industrial complex. Its NATO customers are being told to increase their military spending to 3 or even 4 percent of GDP. But the weak performance of U.S. and German arms may have crashed this dream, along with Europe’s economies sinking into depression. And with German ‘s industrial economy deranged by the severing of its trade with Russia, German Finance Minister Christian Lindner told the Die Welt newspaper on June 16, 2023 that his country cannot afford to pay more money into the European Union budget, to which it has long been the largest contributor.

Without German exports supporting the euro’s exchange rate, the currency will come under pressure against the dollar as Europe buys LNG and NATO replenishes its depleted weaponry stocks by buying new arms from America. A lower exchange rate will squeeze the purchasing power of European labor, while lower social spending to pay for rearmament and provide gas subsidies threatens to plunge the continent into a depression.

A nationalist reaction against U.S. dominance is rising throughout European politics, and instead of America locking in its control over European policy, the United States may end up losing – not only in Europe but throughout the Global South. Instead of turning Russia’s “ruble to rubble” as President Biden promised, Russia’s balance of trade has soared and its gold supply has increased. So have the gold holdings of other countries whose governments are now aiming to de-dollarize their economies.

It is American diplomacy that is driving Eurasia and the Global South out of the U.S. orbit. America’s hubristic drive for unipolar world dominance could only have been dismantled so rapidly from within. The Biden-Blinken-Nuland administration has done what neither Vladimir Putin nor Chinese President Xi could have hoped to achieve in so short a period. Neither was prepared to throw down the gauntlet and create an alternative to the U.S.-centered world order. But U.S. sanctions against Russia, Iran, Venezuela and China have had the effect of protective tariff barriers to force self-sufficiency in what EU diplomat Josep Borrell calls the world “jungle” outside of the US/NATO “garden.”

Although the Global South and other countries have been complaining ever since the Bandung Conference of Non-Aligned Nations in 1955, they have lacked a critical mass to create a viable alternative. But their attention has now been focused by the U.S. confiscation of Russia’s official dollar reserves in NATO countries. That dispelled the thought of the dollar as a safe vehicle in which to hold international savings. The Bank of England’s earlier seizure of Venezuela’s gold reserves kept in London – promising to donate it to whatever unelected opponents of its socialist regime U.S. diplomats designate – shows how the euro as well as the dollar have been weaponized. And by the way, what ever happened to Libya’s gold reserves?

American diplomats avoid thinking about this scenario. They rely to the one unique advantage the United States has to offer. It may refrain from bombing them, from staging a color revolution to “Pinochet” them by the National Endowment for Democracy, or install a new “Yeltsin” giving the economy away to a client oligarchy.

But refraining from such behavior is all that America can offer. It has de-industrialized its own economy, and its idea of foreign investment is to carve out monopoly-rent seeking opportunities by concentrating technological monopolies and control of oil and grain trade in U.S. hands, as if this is economic efficiency, not rent-seeking.

What has occurred is a change in consciousness. We are seeing the Global Majority trying to create an independent and peacefully negotiated choice as to just what kind of an international order they want. Their aim is not merely to create alternatives to the use of dollars, but an entire new set of institutional alternatives to the IMF and World Bank, the SWIFT bank clearing system, the International Criminal Court and the entire array of institutions that U.S. diplomats have hijacked from the United Nations.

The upshot will be civilizational in scope. We are seeing not the End of History but a fresh alternative to neoliberal finance capitalism and its junk economics of privatization, class war against labor, and the idea that money and credit should be privatized in the hands of a narrow financial class instead of being a public utility to finance economic needs and rising living standards..

#michael hudson#naked capitalism#nato#russia#united states#ukraine#ukraine conflict#the end of history

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

15th May >> Mass Readings (Except USA)

Monday, Sixth Week of Eastertide

or

Saint Carthage, Bishop.

Monday, Sixth Week of Eastertide

(Liturgical Colour: White: A(1))

First Reading Acts of the Apostles 16:11-15 The Lord opened Lydia's heart to accept what Paul was saying.

Sailing from Troas we made a straight run for Samothrace; the next day for Neapolis, and from there for Philippi, a Roman colony and the principal city of that particular district of Macedonia. After a few days in this city we went along the river outside the gates as it was the sabbath and this was a customary place for prayer. We sat down and preached to the women who had come to the meeting. One of these women was called Lydia, a devout woman from the town of Thyatira who was in the purple-dye trade. She listened to us, and the Lord opened her heart to accept what Paul was saying. After she and her household had been baptised she sent us an invitation: ‘If you really think me a true believer in the Lord,’ she said ‘come and stay with us’; and she would take no refusal.

The Word of the Lord

R/ Thanks be to God.

Responsorial Psalm Psalm 149:1-6,9

R/ The Lord takes delight in his people. or R/ Alleluia!

Sing a new song to the Lord, his praise in the assembly of the faithful. Let Israel rejoice in its Maker, let Zion’s sons exult in their king.

R/ The Lord takes delight in his people. or R/ Alleluia!

Let them praise his name with dancing and make music with timbrel and harp. For the Lord takes delight in his people. He crowns the poor with salvation.

R/ The Lord takes delight in his people. or R/ Alleluia!

Let the faithful rejoice in their glory, shout for joy and take their rest. Let the praise of God be on their lips: this honour is for all his faithful.

R/ The Lord takes delight in his people. or R/ Alleluia!

Gospel Acclamation cf. Luke 24:46,26

Alleluia, alleluia! It was ordained that the Christ should suffer and rise from the dead, and so enter into his glory. Alleluia!

Or: John 15:26,27

Alleluia, alleluia! The Spirit of truth will be my witness; and you too will be my witnesses. Alleluia!

Gospel John 15:26-16:4 The Spirit of truth will be my witness.

Jesus said to his disciples:

‘When the Advocate comes, whom I shall send to you from the Father, the Spirit of truth who issues from the Father, he will be my witness. And you too will be witnesses, because you have been with me from the outset.

‘I have told you all this that your faith may not be shaken. They will expel you from the synagogues, and indeed the hour is coming when anyone who kills you will think he is doing a holy duty for God. They will do these things because they have never known either the Father or myself. But I have told you all this, so that when the time for it comes you may remember that I told you.’

The Gospel of the Lord

R/ Praise to you, Lord Jesus Christ.

----------------------------------------

Saint Carthage, Bishop

Liturgical Colour: White: A(1))

Readings for the memorial

There is a choice today between the readings for the ferial day (Monday) and those for the memorial. The ferial readings are recommended unless pastoral reasons suggest otherwise.

EITHER: --------

First reading Acts 13:46-49 Since you have rejected the word of God, we must turn to the pagans

Paul and Barnabas spoke out boldly. ‘We had to proclaim the word of God to you first, but since you have rejected it, since you do not think yourselves worthy of eternal life, we must turn to the pagans. For this is what the Lord commanded us to do when he said:

I have made you a light for the nations, so that my salvation may reach the ends of the earth.’

It made the pagans very happy to hear this and they thanked the Lord for his message; all who were destined for eternal life became believers. Thus the word of the Lord spread through the whole countryside.

OR: --------

First reading Acts 20:17-18,28-32,36 I commend you to God and to the word of his grace, and its power

From Miletus Paul sent for the elders of the church of Ephesus. When they arrived he addressed these words to them: ‘Be on your guard for yourselves and for all the flock of which the Holy Spirit has made you the overseers, to feed the Church of God which he bought with his own blood. I know quite well that when I have gone fierce wolves will invade you and will have no mercy on the flock. Even from your own ranks there will be men coming forward with a travesty of the truth on their lips to induce the disciples to follow them. So be on your guard, remembering how night and day for three years I never failed to keep you right, shedding tears over each one of you. And now I commend you to God, and to the word of his grace that has power to build you up and to give you your inheritance among all the sanctified.’ When he had finished speaking he knelt down with them all and prayed.

OR: --------

First reading Acts 26:19-23 I have stood firm to this day, testifying to great and small alike

Paul said: ‘King Agrippa, I could not disobey the heavenly vision. On the contrary I started preaching, first to the people of Damascus, then to those of Jerusalem and all the countryside of Judaea, and also to the pagans, urging them to repent and turn to God, proving their change of heart by their deeds. This was why the Jews laid hands on me in the Temple and tried to do away with me. But I was blessed with God’s help, and so I have stood firm to this day, testifying to great and small alike, saying nothing more than what the prophets and Moses himself said would happen: that the Christ was to suffer and that, as the first to rise from the dead, he was to proclaim that light now shone for our people and for the pagans too.’

Responsorial Psalm Psalm 88(89):2-5,21-22,25,27

I will sing for ever of your love, O Lord.

I will sing for ever of your love, O Lord; through all ages my mouth will proclaim your truth. Of this I am sure, that your love lasts for ever, that your truth is firmly established as the heavens.

I will sing for ever of your love, O Lord.

‘I have made a covenant with my chosen one; I have sworn to David my servant: I will establish your dynasty for ever and set up your throne through all ages.

I will sing for ever of your love, O Lord.

‘I have found David my servant and with my holy oil anointed him. My hand shall always be with him and my arm shall make him strong.

I will sing for ever of your love, O Lord.

‘My truth and my love shall be with him; by my name his might shall be exalted. He will say to me: “You are my father, my God, the rock who saves me.”’

I will sing for ever of your love, O Lord.

Gospel Acclamation Mt23:9,10

Alleluia, alleluia! You have only one Father, and he is in heaven; you have only one Teacher, the Christ. Alleluia!

Or: Mt28:19,20

Alleluia, alleluia! Go, make disciples of all the nations. I am with you always; yes, to the end of time. Alleluia!

Or: Mk1:17

Alleluia, alleluia! Follow me, says the Lord, and I will make you into fishers of men. Alleluia!

Or: Lk4:18

Alleluia, alleluia! The Lord has sent me to bring the good news to the poor, to proclaim liberty to captives. Alleluia!

Or: Jn10:14

Alleluia, alleluia! I am the good shepherd, says the Lord; I know my own sheep and my own know me. Alleluia!

Or: Jn15:5

Alleluia, alleluia! I am the vine, you are the branches. Whoever remains in me, with me in him, bears fruit in plenty, says the Lord. Alleluia!

Or: 2Co5:19

Alleluia, alleluia! God in Christ was reconciling the world to himself, and he has entrusted to us the news that they are reconciled. Alleluia!

EITHER: --------

Gospel Matthew 9:35-37 The harvest is rich but the labourers are few

Jesus made a tour through all the towns and villages, teaching in their synagogues, proclaiming the Good News of the kingdom and curing all kinds of diseases and sickness. And when he saw the crowds he felt sorry for them because they were harassed and dejected, like sheep without a shepherd. Then he said to his disciples, ‘The harvest is rich but the labourers are few, so ask the Lord of the harvest to send labourers to his harvest.’

OR: --------

Gospel Matthew 16:13-19 You are Peter and on this rock I will build my Church

When Jesus came to the region of Caesarea Philippi he put this question to his disciples, ‘Who do people say the Son of Man is?’ And they said, ‘Some say he is John the Baptist, some Elijah, and others Jeremiah or one of the prophets.’ ‘But you,’ he said ‘who do you say I am?’ Then Simon Peter spoke up, ‘You are the Christ,’ he said ‘the Son of the living God.’ Jesus replied, ‘Simon son of Jonah, you are a happy man! Because it was not flesh and blood that revealed this to you but my Father in heaven. So I now say to you: You are Peter and on this rock I will build my Church. And the gates of the underworld can never hold out against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven: whatever you bind on earth shall be considered bound in heaven; whatever you loose on earth shall be considered loosed in heaven.’

OR: --------

Gospel Matthew 23:8-12 The greatest among you must be your servant

Jesus said to his disciples, ‘You must not allow yourselves to be called Rabbi, since you have only one master, and you are all brothers. You must call no one on earth your father, since you have only one Father, and he is in heaven. Nor must you allow yourselves to be called teachers, for you have only one Teacher, the Christ. The greatest among you must be your servant. Anyone who exalts himself will be humbled, and anyone who humbles himself will exalted.’

OR: --------

Gospel Matthew 28:16-20 Go and make disciples of all nations

The eleven disciples set out for Galilee, to the mountain where Jesus had arranged to meet them. When they saw him they fell down before him, though some hesitated. Jesus came up and spoke to them. He said, ‘All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go, therefore, make disciples of all the nations; baptise them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teach them to observe all the commands I gave you. And know that I am with you always; yes, to the end of time.’

OR: --------

Gospel Mark 1:14-20 I will make you into fishers of men

After John had been arrested, Jesus went into Galilee. There he proclaimed the Good News from God. ‘The time has come’ he said ‘and the kingdom of God is close at hand. Repent, and believe the Good News.’ As he was walking along by the Sea of Galilee he saw Simon and his brother Andrew casting a net in the lake – for they were fishermen. And Jesus said to them, ‘Follow me and I will make you into fishers of men.’ And at once they left their nets and followed him. Going on a little further, he saw James son of Zebedee and his brother John; they too were in their boat, mending their nets. He called them at once and, leaving their father Zebedee in the boat with the men he employed, they went after him.

OR: --------

Gospel Mark 16:15-20 Go out to the whole world; proclaim the Good News

Jesus showed himself to the Eleven and said to them: ‘Go out to the whole world; proclaim the Good News to all creation. He who believes and is baptised will be saved; he who does not believe will be condemned. These are the signs that will be associated with believers: in my name they will cast out devils; they will have the gift of tongues; they will pick up snakes in their hands, and be unharmed should they drink deadly poison; they will lay their hands on the sick, who will recover.’ And so the Lord Jesus, after he had spoken to them, was taken up into heaven: there at the right hand of God he took his place, while they, going out, preached everywhere, the Lord working with them and confirming the word by the signs that accompanied it.

OR: --------

Gospel Luke 5:1-11 They left everything and followed him

Jesus was standing one day by the Lake of Gennesaret, with the crowd pressing round him listening to the word of God, when he caught sight of two boats close to the bank. The fishermen had gone out of them and were washing their nets. He got into one of the boats – it was Simon’s – and asked him to put out a little from the shore. Then he sat down and taught the crowds from the boat. When he had finished speaking he said to Simon, ‘Put out into deep water and pay out your nets for a catch.’ ‘Master,’ Simon replied, ‘we worked hard all night long and caught nothing, but if you say so, I will pay out the nets.’ And when they had done this they netted such a huge number of fish that their nets began to tear, so they signalled to their companions in the other boat to come and help them; when these came, they filled the two boats to sinking point. When Simon Peter saw this he fell at the knees of Jesus saying, ‘Leave me, Lord; I am a sinful man.’ For he and all his companions were completely overcome by the catch they had made; so also were James and John, sons of Zebedee, who were Simon’s partners. But Jesus said to Simon, ‘Do not be afraid; from now on it is men you will catch.’ Then, bringing their boats back to land, they left everything and followed him.

OR: --------

Gospel Luke 10:1-9 Your peace will rest on that man

The Lord appointed seventy-two others and sent them out ahead of him, in pairs, to all the towns and places he himself was to visit. He said to them, ‘The harvest is rich but the labourers are few, so ask the Lord of the harvest to send labourers to his harvest. Start off now, but remember, I am sending you out like lambs among wolves. Carry no purse, no haversack, no sandals. Salute no one on the road. Whatever house you go into, let your first words be, “Peace to this house!” And if a man of peace lives there, your peace will go and rest on him; if not, it will come back to you. Stay in the same house, taking what food and drink they have to offer, for the labourer deserves his wages; do not move from house to house. Whenever you go into a town where they make you welcome, eat what is set before you. Cure those in it who are sick, and say, “The kingdom of God is very near to you.”’

OR: --------

Gospel Luke 22:24-30 I confer a kingdom on you, just as the Father conferred one on me

A dispute arose between the disciples about which should be reckoned the greatest, but Jesus said to them: ‘Among pagans it is the kings who lord it over them, and those who have authority over them are given the title Benefactor. This must not happen with you. No; the greatest among you must behave as if he were the youngest, the leader as if he were the one who serves. For who is the greater: the one at table or the one who serves? The one at table, surely? Yet here am I among you as one who serves! ‘You are the men who have stood by me faithfully in my trials; and now I confer a kingdom on you, just as my Father conferred one on me: you will eat and drink at my table in my kingdom, and you will sit on thrones to judge the twelve tribes of Israel.’

OR: --------

Gospel John 10:11-16 The good shepherd is one who lays down his life for his sheep

Jesus said:

‘I am the good shepherd: the good shepherd is one who lays down his life for his sheep. The hired man, since he is not the shepherd and the sheep do not belong to him, abandons the sheep and runs away as soon as he sees a wolf coming, and then the wolf attacks and scatters the sheep; this is because he is only a hired man and has no concern for the sheep.

‘I am the good shepherd; I know my own and my own know me, just as the Father knows me and I know the Father; and I lay down my life for my sheep. And there are other sheep I have that are not of this fold, and these I have to lead as well. They too will listen to my voice, and there will be only one flock, and one shepherd.’

OR: --------

Gospel John 15:9-17 You are my friends if you do what I command you

Jesus said to his disciples:

‘As the Father has loved me, so I have loved you. Remain in my love. If you keep my commandments you will remain in my love, just as I have kept my Father’s commandments and remain in his love. I have told you this so that my own joy may be in you and your joy be complete. This is my commandment: love one another, as I have loved you. A man can have no greater love than to lay down his life for his friends. You are my friends, if you do what I command you. I shall not call you servants any more, because a servant does not know his master’s business; I call you friends, because I have made known to you everything I have learnt from my Father. You did not choose me: no, I chose you; and I commissioned you to go out and to bear fruit, fruit that will last; and then the Father will give you anything you ask him in my name. What I command you is to love one another.’

OR: --------

Gospel John 21:15-17 Feed my lambs, feed my sheep

Jesus showed himself to his disciples, and after they had eaten he said to Simon Peter, ‘Simon son of John, do you love me more than these others do?’ He answered, ‘Yes Lord, you know I love you.’ Jesus said to him, ‘Feed my lambs.’ A second time he said to him, ‘Simon son of John, do you love me?’ He replied, ‘Yes, Lord, you know I love you.’ Jesus said to him, ‘Look after my sheep.’ Then he said to him a third time, ‘Simon son of John, do you love me?’ Peter was upset that he asked him the third time, ‘Do you love me?’ and said, ‘Lord, you know everything; you know I love you.’ Jesus said to him, ‘Feed my sheep.’

1 note

·

View note

Text

Persian War Wednesdays: 1.15-1.22

Or, How the Lydians and Milesians Became BFFs

Time to dredge up some OCs I rarely draw lol

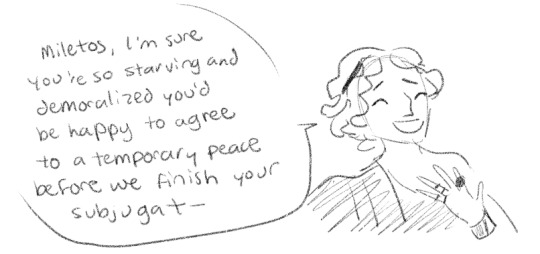

So once upon a time the Lydians who you may remember from such fun and exciting hits as “good at horse warfare” and “invented coinage” decided to siege Miletus, and this siege took a few generations of their kings.

The plan was to leave buildings and homes untouched and torch all the crops and trees so that every year just before harvest the Milesians would be demoralized enough to consider surrendering. Lydia was playing the long game.

This went on for 11 years and Miletus didn’t receive help from any of the other Ionian Greeks (save for one bit they’d helped out earlier in a different war).

In the twelfth year, the Lydians accidentally burnt down a temple to Athena of Assesos when the wind caused fire to spread from the crops they were trying to burn. Mysteriously, the King of Lydia (Alyattes) came down with an illness.

So off goes Lydia to the Oracle at Delphi which is where most people go to solve Mysteriously Coincidental Monarchical Maladies and the Oracle cleverly suggests Maybe You Should Rebuild That Temple You Burnt By Accident.

The Lydians get set to go ask the Milesians nicely if they are ok with not being sieged this year while they make reparations, they only wanted to starve them a little after all and they’re sure once this temple is fixed that they can go back to destroying their crops again!

The Milesians, hearing that the Lydians are on their way, quickly gather up every scrap of food they have and pile it up in the middle of town right where the Lydians are going to be marching through...

The Milesians threw a huge party with tons of food and drink and dancing, just like they totally, honestly, really seriously do all the time even when the Lydians have been setting fire to all their food.

And thus the Lydians and the Milesians set aside their differences and became friends and allies (until Persia noticed how shiny Lydia was anyway).

Bonus:

#hapo reads herodotus#hapo reads greek lit#ancientalia#aph ionia#aph miletus#aph lydia#aph corinth#hapo doodles#athens and sparta adventures#digital art#clip studio paint#aph persia#aasa persia

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Favorite characters meme

I’ve been tagged by the marvelous @aceoftigers - thank you, dear!

Share ten different favorite characters from ten different pieces of media in no particular order, and feel free to pass it on!

1) Eskel (game/book/fandom) version, The Witcher

2) Finn, Star Wars: The Force Awakens

3) Maia Drazhar, The Goblin Emperor by Katherine Addison

4) Cliopher “Kip” Mdang, The Hands of the Emperor by Victoria Goddard

5) Hazel-rah, Watership Down by Richard Adams

6) Mariel, Mariel of Redwall by Brian Jacques

7) Digger-of-Unnecessarily-Complicated-Tunnels, Digger by Ursula Vernon

8) Jamethiel Priest’s-Bane, God Stalk by P.C. Hodgell

9) Lydias of Miletus, Stealing Fire by Jo Graham

10) Aerin-sol, The Hero and the Crown by Robin McKinley

Tagging anyone who would like to play!

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cultures and Places (tags)

Mainly Roman and Greek artworks from different parts of Europe. Also some pics from Etruscan and other non-Roman/Non-Greek cultures.

https://romegreeceart.tumblr.com/tagged/

A

Aegai

Aenona

Afghanistan

Agricento

Ajerbaijan

Akrotiri

Alexandria

Algeria

Andalucia

Antioch

Aphrodisias

Apollonia-Pontica

Apulia

Aquileia

Aquitane

Arabia

Arabia Petraea

Arcadia

Argos

Arezzo

Ariccia (sanctuary)

Arles

Armenia

Arrotino

Asia Minor

Assos

Assyria

Athens

Attica

Augusta Raurica (Switzerland)

Aurunci (people)

Austria

B

Bad Kreuznach Römerhalle

Baiae

Barbarians

Basilicata

Baths of Caracalla

Belgium

Berthouville (silver treasure)

Bithynia

Black Sea

Bordeaux

Boscoreale

Boscotrecase

Bosporan Kingdom

Brescia

Bulgaria

C

Cabra

Caere / Cerveteri

Caere

Caesarea Mauretania

Cagliari

Calabria

Campania

Campus Martius

Canosa

Cappadocia

Capri

Capua

Caria

Carinthia

Carthage

Celtic

Centocelle

Chalcidice

Chalcis

Chiusi / Clusium

Colosseum

Cologne

Cordoba

Corinth

Corinthian

Crete

Crimea

Croatia

Cumae

Cyclades

Cyprus

Cyrenaica

Cyrene

Cyzicus

Czech Repuplic

D

Dacia

Delphi

Delos

Denmark

Derveni

Dion

Dura Europos

E

East Roman

Eastern Mediterranean

Egypt

Ejica

Eleusis

Elis

Emesa

Ephesus

Eretria

Eryx

Esquiline Hill

Estonia

Etruscans

Euboea

F

Fayum

Felix Romuliana

Ferrara

Finland

Forum Romanum

France

G

Gabii

Gallic empire

Gaul

Gaul 2 (gallic)

Gela

Germania Inferior

Germania Superior

Germania

Germany

Gnathia

Goths

Greece

Greek colony

H

Hellenistic

Herakleion (sunken city)

Herculaneum

Horti Lamiani

House of the Citharist

House of the Centenary

House of the Epigrams

House of the Golden Bracelet

House of the Hanging Balcony

House of Julia Felix

House of Lovers

House of Lucius Cecilius Jucundus

House of Marcus Lucretius Fronto

House of the Vettii

Houses - Case Romane del Celio

Hungary

Huns

I

Illyrians

Ionia

Israel

Italic peoples

Italica

Italy

J

Jordan

Judea

K

Kerameikos

Kingdom of Aksum

Knossos

Kos

Kosovo

L

Latium

Lavinium (Italic cult site)

Lebanon

Leptis Magna

Lesbos

Libya

Limes

Limyra

Locri

London

Lucanians

Luna

Lydia

Lyon

M

Macedonia

Magna Graecia

Mainz

Malta

Mallorca

Mantova

Marathon

Marche

Mauretania

Merida

Mesopotamia

Metapontum

Milan

Miletus

Minoan

Milos

Moesia Superior

Morocco

Mycenae 1

Mycenae 2

Mykonos

Myrina

N

Nabatea

Netherlands

Nemi (sanctuary)

Nimes

Nola

North Africa

Numidia

O

Olympia

Oplontis

Orvieto

Oscan

Osteria dell’Osa necropolis (early italic cultures)

Ostia Antica

P

Paestum

Palatine hill

Palestine

Palmyra

Paphos

Paros

Parthia

Peleus

Pella

Peloponnesos

Penteskouphia

Pergamon

Perge

Persia

Perugia

Petra

Phanagoria

Philippi

Phrygia

Picentes (italic people)

Piraeus

Poland

Pompeii

Pontus

Poros

Portugal

Posillipo

Positano

Potenza

Pozzuoli

Praeneste

Priene

Prima Porta (Livia’s villa)

Ptolemaic-Egypt

Pylos

R

Ravenna

Rhodes

Riace

Rimini

Roman Britain

Roman Britain (England)

Roman Britain (Scotland)

Roman Britain (Wales)

Roman Egypt

Romania

Rome

Russia

S

Sabines

Salona

Samnites

Samonthrace

Samos

Santorini

Sardinia

Sarmatians

Sarsina

Scythians

Seleucid

Seleucid empire

Selinunte

Sicily

Sicyon

Sidrona

Slovakia

Slovenia

Southern Italy

Spain 1

Spain 2 (Iberia)

Spain 3 (Hispania)

Sparta

Stabiae

Stobi

Sweden

Switzerland

Syracuse

Syria

T

Tanagra

Taranto

Tarentum

Tarquinia

Thebes

Thera

Thessaloniki

Thracia

Timgad

Tiryns

Tivoli

Tomis (Ovid died here)

Toulouse

Trastevere

Trier

Tunisia 1

Tunisia 2

Turkey

U

Ukraine

Umbria

V

Veii

Velia

Veneto

Vercelli

Verona

Vienne

Villa del Mitra

Villa Farnesina (Trastevere / Palazzo Massimo)

Villa of the Mysteries

Villa of the Papyri

Villa of Poppaea

Villa Romana del Casale (Sicily)

Vindolanda

Volterra

Vulci

Volsci

Y

Yemen

York

Z

Zeugma

#my tags#culrures and places#Ancient Rome#Ancient Greece#Etruscans#ancient world#ancient art#history

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

The totality of things… is an exchange for fire, and fire an exchange for all things, in the way goods (are an exchange) for gold, and gold for goods.

Heraclitus

After the first coins were minted around 6oo BC in the kingdom of Lydia, the practice quickly spread to Ionia, the Greek cities of the adjacent coast. The greatest of these was the great walled metropolis of Miletus, which also appears to have been the first Greek city to strike its own coins. It was Ionia, too, that provided the bulk of the Greek mercenaries active in the Mediterranean at the time, with Miletus their effective headquarters. Miletus was also the commercial center of the region, and, perhaps, the first city in the world where everyday market transactions came to be carried out primarily in coins instead of credit. Greek philosophy, in turn, begins with three men: Thales, of Miletus (c. 624 BC-c. 546 BC) , Anaximander, of Miletus (c. 610 BC-c. 546 BC) , and Anaximenes, of Miletus (c. 585 BC-C. 525 BC)--in other words, men who were living in that city at exactly the time that coinage was first introduced. All three are remembered chiefly for their speculations on the nature of the physical substance from which the world ultimately sprang. Thales proposed water, Anaximenes, air. Anaximander made up a new term, apeiron, "the unlimited," a kind of pure abstract substance that could not itself be perceived but was the material basis of everything that could be. In each case, the assumption was that this primal substance, by being heated, cooled, combined, divided, compressed, extended, or set in motion, gave rise to the endless particular stuffs and substances that humans actually encounter in the world, from which physical objects are composed--and was also that into which all those forms would eventually dissolve.

It was something that could turn into everything. As [Richard] Seaford emphasizes, so was money. Gold, shaped into coins, is a material substance that is also an abstraction. It is both a lump of metal and something more than a lump of metal--it's a drachma or an obol, a unit of currency which (at least if collected in sufficient quantity, taken to the right place at the right time, turned over to the right person) could be exchanged for absolutely any other object whatsoever.

…

… Greek thinkers were suddenly confronted with a profoundly new type of object, one of extraordinary importance--as evidenced by the fact that so many men were willing to risk their lives to get their hands on it--but whose nature was a profound enigma.

David Graeber, Debt: The First 5000 Years

[Aristotle] … sees that the value-relation which provides the framework for this expression of value itself requires that the house should be qualitatively equated with the bed, and that these things, being distinct to the senses, could not be compared with each other as commensurable magnitudes if they lacked this essential identity. 'There can be no exchange,' he says, 'without equality, and no equality without commensurability' … Here, however, he falters, and abandons the further analysis of the form of value. 'It is, however, in reality, impossible … that such unlike things can be commensurable,' i.e. qualitatively equal. This form of equation can only be something foreign to the true nature of the things, it is therefore only 'a makeshift for practical purposes'.

…

However, Aristotle himself was unable to extract this fact, that, in the form of commodity-values, all labour is expressed as equal human labour and therefore as labour of equal quality, by inspection from the form of value, because Greek society was founded on the labour of slaves, hence had as its natural basis the inequality of men and of their labour-powers. The secret of the expression of value, namely the equality and equivalence of all kinds of labour because and in so far as they are human labour in general, could not be deciphered until the concept of human equality had already acquired the permanence of a fixed popular opinion. This however becomes possible only in a society where the commodity-form is the universal form of the product of labour, hence the dominant social relation is the relation between men as possessors of commodities. …

Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Chapter 1

The generalization of commodity production is only possible when production itself is transformed into capitalist production, when the multiplication and augmentation of abstract wealth becomes the direct goal of production and all other social relationships are subsumed to this goal. The “destructive power of money” which was the object of much criticism in many pre-capitalist modes of production (by many authors in ancient Greece, for example) is rooted precisely in this process of the capitalization of society as a result of the generalization of the money relationship.

Michael Heinrich, “A Thing with Transcendental Qualities: Money as a Social Relationship in Capitalism”

Aristotle contrasts economics with 'chrematistics '. He starts with economics. So far as it is the art of acquisition, it is limited to procuring the articles necessary to existence and useful either to a household or the state. … With the discovery of money, barter of necessity developed … into trading in commodities, and this again, in contradiction with its original tendency, grew into chrematistics, the art of making money. Now chrematistics can be distinguished from economics in that 'for chrematistics, circulation is the source of riches … And it appears to revolve around money, for money is the beginning and the end of this kind of exchange … Therefore also riches, such as chrematistics strives for, are unlimited. Just as every art which is not a means to an end, but an end in itself, has no limit to its aims, because it seeks constantly to approach nearer and nearer to that end, while those arts which pursue means to an end are not boundless, since the goal itself imposes a limit on them, so with chrematistics there are no bounds to its aims, these aims being absolute wealth. Economics, unlike chrematistics, has a limit ... for the object of the former is something different from money, of the latter the augmentation of money … By confusing these two forms, which overlap each other, some people have been led to look upon the preservation and increase of money ad infinitum as the final goal of economics' (Aristotle, De Republica, ed. Bekker, lib. I, c. 8, 9, passim).

Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Chapter 4

75 notes

·

View notes

Photo

KINGSHIP AND THE OIKOUMEN: The term oikoumene (οἰκουμένη) is commonly translated as simply “the world,” and is sometimes identified as an expression of Hellenistic thought, and therefore regarded as an anachronism when applied to Anaximander’s map. In fact, the term was in use as early as the earliest Ionic prose, and the context of its use by Herodotus reveals its established meaning. Oikoumene means “settled,” in the sense “possessing established communities” and, by extension, “possessing productive communities.” Oikoumene as a description of the earth, therefore refers to that part of the earth that is settled and cultivated from towns, and by extension, it describes all the lands of the earth under the regime of settled agriculture.

The word oikoumene is used in this sense by Herodotus to describe Greek towns in Ionia and on the settled islands of the Aegean, to characterize India as the most distant settled land, to describe the frontier of settlement in Libya, Scythia, or among distant settled Thracians, and to describe Athens. [In Herodotus’ almost consistent usage, sedentary agriculturalists “inhabit” the land, while nomads “use” or “graze” it, and, with rare exceptions, do “not sow” the land.] Settled land, as understood by Herodotus and by Thucydides as well, was desirable land, and was therefore vulnerable to appropriation by anyone who was strong enough to seize it. Herodotus and Thucydides both recognized that the relationship between sovereign power and the productive lands that sustained sovereignty was the central problem facing the leading actors in their histories. [Adumbrated already in Herodotus’ opening chapters on Lydia, this key problem is directly addressed in the closing passage of his Histories (9.122), where Cyrus advises the Persians, to whom “Zeus has given hegemony” and who now “rule over many men and all of Asia,” to maintain their sovereignty by remaining stronger than those who inhabit cultivated lands. The relationship of power to surplus or material resources, ultimately resting on the quality of the land, is likewise explicitly addressed in Thucydides’ opening chapters (1.2–17).] Anaximander was certainly aware of the importance of this relationship as well. As an Asiatic Greek whose city, Miletus, had submitted to the power exercised by the tyrants of Lydia over their agricultural land, Anaximander knew that the settled land of the earth was the foundation of sovereignty. The concepts were inextricably linked.

The oikoumene was the proper domain of sovereign kings who possessed that domain in order to assure both its prosperity and their own. Xenophon, who always sought meaning in archaic paradigms, presents just such a definition of oikoumene in his Cyropaedia, an idealized account of Cyrus the Great and his creation of the Persian empire. When Cyrus and his forces had invaded a land formerly controlled by the Assyrians, Cyrus inquired of some captured enemy cavalrymen “how long a way they had ridden, and if the country was inhabited”:

They said that they had ridden a great distance, and that the entire country was inhabited and full of sheep and goats and cattle and horses and grain and all good things. “There are two things,” Cyrus said, “that we must make sure of: that we are more powerful than those who possess these things, and that they stay where they are. For an inhabited land is a possession of great value; but when it is deserted, it becomes worthless.

Cyrus’ formulation of the relationship between sovereign power and the subjugation of the cultivated oikoumene was precisely the meaning of the sign that appeared to Gordius father of Midas, as Arrian tells it: “One day, while he was plowing, an eagle flew down onto the yoke and remained sitting there until the time came for the unyoking of the oxen at the end of the day.” The unshakable grip of the eagle on the yoke of the plowman’s team, an alarming sight to Gordius the farmer, was the sign that a true king must always be “more powerful than those who possess these [fruits of the earth].” This was the relationship of tyrant to subject demonstrated in the ritual march of Midas through lands neighboring Phrygia, and of Alyattes through the land of Miletus; and the relationship of sovereign to subject was commonly signified by the yoke of submission and the power of an eagle or a hawk. Order in the settled world, therefore, depended on the orderly yet forceful relationship between sovereign and subjects. Force was demonstrated by indomitable prowess in war, exemplified by the conquests of Cyrus, and of Alyattes and Midas before him. The legitimacy of the resulting order was signified by reverence to the divinities who upheld order. While the prosperity of the settled, cultivated oikoumene was generally associated with the beneficence of a maternal deity, such as Demeter or the Phrygian Mother, the divinity who most actively and forcefully extended the conditions for settled life was the young warrior usually identified as the son of the divine Mother. To the Greeks and their Asiatic neighbors, this was Apollo.

Apollo was the champion of sovereignty in a divinely ordered system. He was the archer and warrior whose power could threaten the gods, but whose loyalty to his father, Zeus the King, was steadfast. With his sister, Artemis, he was also known as the offspring of the divine Mother, Leto, called the Mother of the Gods in Lycian texts, possibly appearing as the Mother in Lydian inscriptions. Greeks acknowledged that Apollo had ancient and venerable seats in Asia Minor, in Lycia and Lydia as well as at Miletus. Among the Lydians, he was honored as Qldãns, sometimes called the “great” or “powerful” god, and partner of Artimus. Apollo’s birthplace on the island of Delos (according to the Greeks) and his many oracular shrines made him especially accessible as a link between gods and men. Through Apollo, kingship on earth was established, and order within the oikoumene was maintained and extended. Among Greeks, Apollo championed kingship and the expansion of the oikoumene chiefly by instigating or legitimizing the foundation of colonies. The oracle exercised that role by designating or instructing a founder, the oikistes, whose role as leader of the new community was analogous, in several respects, to that of a conquering king. Through the god-supported oikist, a new orderly and prospering community was brought into existence. The identity of the oikist as a king or tyrant is even explicit in numerous instances early in the history of Greek colonization, when founders came from royal or tyrannical houses. In the case of Battus, founder of Cyrene, Apollo’s oracle calls him basileus, “king,” and Battus’ leadership resulted in the establishment of a royal dynasty. The role of the founder approached that of the god himself by the fact that both were addressed as archegetes, “first leader,” and by the heroic cult accorded to the founder after death. Such heroic honors after death recall the funerary honors accorded to the kings of Sparta and, as Herodotus notes, to kings in Asia. They also recall the honors accorded to the memory of King Midas. In the dedication of the Midas Monument, inscribed in the seventh or sixth century, Midas is addressed as wanax, “lord,” a title commonly used of Apollo. Midas is also called lawag<e>tas, “leader of the host,” a title close to archegetes. Kingship was assimilated to divine leadership here, and Apollo provided the paradigm of leadership that drew every rightful ruler to him. So it is that sovereign rulers, including colonial founders, the kings of Sparta, and the tyrants of Lydia, all sought guidance and justification from Apollo, especially through his oracular shrine at Delphi. Gyges legitimized his usurpation of the throne by Apollo’s oracle, Herodotus reports (1.14), and memorialized the event by gifts to Apollo at Delphi that bore his name thereafter. Alyattes reached a settlement in his war against Miletus through the mediation of Apollo at Delphi (1.19–21, 25). Croesus sought divine support for the expansion of his empire from Apollo’s oracles, and displayed his reverence to the god’s shrine at Delphi especially through his fabulously rich dedications (1.46–55, 87, 90–92; 8.35). A generous gift to Apollo in Laconia was an important gesture in Croesus’ formation of an alliance with the Spartans (1.69.4). In all of these instances, we see the Mermnad rulers acting not as outsiders making deferential gestures to Greek customs, but as partners with Greeks in a shared cult. In their day Lydia was home to indomitable prowess in war, and to the most magnificent kingship. By Apollo’s authorization, the Mermnad tyrants of Lydia could be seen as the preeminent champions of order within the oikoumene.

THE ITINERARY OF THE OIKOUMEN: The concept of a world order established through the actions of kings and founders guided by divinity is an idea that implies a historical geography of the oikoumene. That is, it implies a place of historical (or myth-historical) origin for this order, and it suggests that, with divine guidance, this order can be renewed or perpetuated, and even more widely extended. It thus becomes relevant to consider how such a historical geography might have been represented on Anaximander’s map of the oikoumene.

A place of origin for a cultural system would most appropriately be the center of a circular map. In deference to the strong tradition, attested by Pindar, Aeschylus, Euripides, and later sources, that the omphalos beside the Pythia’s oracular seat at Delphi marked the center of the world, it is often assumed that Anaximander’s map placed Delphi at its center. In view of the importance of Apollo’s oracle at Delphi by the time Anaximander composed his map, this is not an unreasonable supposition. But there are plausible alternatives. Apollo’s birthplace, the island of Delos, also has a strong claim for consideration as the midpoint of Anaximander’s map, especially if we accept that it depicted the earth as two continents separated by the waters of the Aegean and greater Mediterranean. There is no way of knowing if any single place was identified as precisely the center of Anaximander’s map, although it is a reasonable assumption that the Aegean and its shores were depicted as the central region of the oikoumene. The dissemination of a cultural system could be represented on a circular map in some manner other than radiation from an exact central point. Both the terminology used to describe Anaximander’s map and the only surviving example of a world map contemporary to Anaximander, the Babylonian map of the world, suggest how this may have been achieved. “Itinerary of the earth,” periodos ges was one of the names by which Anaximander’s map was known. Periodos ges is usually taken to mean simply “map of the world,” but its literal meaning, “itinerary of the earth,” is also an appropriate description for a written treatise accompanying a map, as was the case in Hecataeus’ geographical work and almost certainly for Anaximander as well. It is probable that Anaximander described the oikoumene shown on his map in some manner of a written itinerary. The record of an itinerary, describing a march through the land and the places of importance encountered along the way, was often a symbol of appropriation in both ritual and military terms. Such topographical lists have a long history in cuneiform literature, especially among the Hittites, where historical annals, treaties, and ritual texts alike include itineraries of conquest and appropriation. In a Mesopotamian tradition known to the Hittites, the third-millennium empire of Sargon of Akkad was represented in stories of conquest. By the late eighth century, in the time of Sargon II of Assyria, these stories were arranged into a more or less canonical series of itineraries embracing lands from the “Upper Sea” (Mediterranean) to the “Lower Sea” (Persian Gulf), establishing a pattern of conquest that the contemporary kings of Assyria sought to emulate. A fragmentary version of Sargon’s legendary conquests survives on the cuneiform tablet of the seventh or sixth century b.c.e. that also preserves the Babylonian map of the world. This schematic map depicts the world as a circle, surrounded by the sea. The circle of the earth is divided in two by the Euphrates River, with Babylon placed prominently astride the river, but not at the center of the map, which is marked by a compass point. Other lands, such as Assyria and Urartu, are dispersed around Babylon within the circle of the surrounding sea. Geography merges with legend and mythology in the texts that accompany this map. The principles that established the configuration of the known world, from this Babylonian perspective, are the relative centricity of Babylon and the historical example of the conquests of Sargon of Akkad, who came not from Babylon itself, but from the land of “Sumer and Akkad” that the Babylonians claimed as their own. It is likely that Anaximander adapted the principles of Mesopotamian geography to an Anatolian context in his depiction of the oikoumene and description of its extent, just as he is known to have utilized other aspects of Babylonian science. Anaximander’s map probably displayed the framework for an itinerary of appropriation emanating from Lydian Asia, possibly from Sardis itself. A written itinerary (periodos) through the settled communities of the earth was probably the manner by which Anaximander defined the extent of the oikoumene. ... Midas was for Lydian Asia what Sargon of Akkad was for contemporary Babylonia, and Sesostris was for Egypt—the model world conqueror. An ancient Mesopotamian literary tradition provided the authority for Sargon’s wide conquests. A pastiche of Egyptian records and misappropriated Hittite monuments documented Sesostris’ itinerary. Compared with Midas, these traditions were vastly different in the nature and antiquity of their origins, yet the traditions of Sargon, Sesostris, and Midas appear to have matured into their most familiar forms contemporaneously, in the seventh and early sixth centuries. Anaximander’s map and the commentary that accompanied it appear to have been an outgrowth of the Asiatic tradition of Midas, for they represented the itineraries that defined Midas’ kingdom, and suggested the ways along which it could be extended by his heirs. The oikoumene, as described and depicted by Anaximander, represented the natural domain of the world tyrant.

THE BALANCE OF JUSTICE IN THE WORLD Scholars commenting on Anaximander’s cosmological ideas have always been struck by the manner in which he conceived of the elements of the natural world as governed by a moral principle, in which justice is rendered for wrongs committed. Such is the concept at the core of the single surviving passage of Anaximander’s writings, as quoted by Simplicius:

Anaximander . . . says that the “first principle” [or “rule,” ] was neither water nor any of the other so-called elements, but some other “boundless nature, out of which all the heavens and all the orders within them arise. Out of these comes the generation of existing things, and back to them by necessity things disintegrate, for these things render justice and retribution to each other for wrongdoing according to the ordering of time.”

It seems likely that the idea of cosmic balance and symmetry also informed Anaximander’s image of the rightful domain of sovereignty conveyed by his map and description of the oikoumene, in an abstract as well as a graphic way. Like all paradigms of “the heavens and all the orders [that arise] within them,” worldly sovereignty, too, grew and declined in accordance with justice and in retribution for wrongdoing. Among the Mermnads of Lydia as well as among other long-suffering neighbors of the Assyrians, belief in such a world order was a powerful incentive to establish their own just sovereignty over the world. So we find that the concept of world dominion expressed in terms of cosmic justice, supported by omens, and symbolized by a map of the world was also at the forefront of scholarship in the Babylonian court of Nebuchadnezzar II and his successors, the contemporaries and allies of Alyattes and Croesus. Acts of piety and devotion to traditional cults are prominent among the measures taken by Babylonian rulers to demonstrate their worthiness. Neo-Babylonian Sargonic texts emphasize these same devotions as the basis for Sargon’s legendary success, and their neglect as the reason for the dissolution of his empire under his successors. Other texts describe the divine sanction by which a new world empire now was deemed to belong to King Nebuchadnezzar. Among these are references to the inhabited world (Akkadian dadmu) in terms that echo the concepts embedded in the story of the Gordian knot and Anaximander’s map of the oikoumene.

So Nebuchadnezzar is proclaimed as king of all the lands [matatu], the entire inhabited world [dadmu] from the Upper Sea to the Lower Sea, distant lands, the people of vast territories, kings of faraway mountains and remote nagu [“regions” or “islands”] in the Upper and Lower Sea, whose lead-rope Marduk, my lord, placed in my hand in order to pull his yoke.

Babylon in the time of Nebuchadnezzar II (605–562 b.c.e.) was very much a city of the world. By the time of the treaty on the Halys in 585, Nebuchadnezzar had established his undisputed sway “from the Upper Sea to the Lower Sea” (from the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf). His claim to wider suzerainty over “kings of faraway nagu was more wishful than actual, but it was based on the reality that men of every station, from royal emissaries and high-ranking exiles to skilled and unskilled laborers from Greece, Lydia, Egypt, Media, Elam, and Arabia, were to be found in Babylon.

The reign of Nebuchadnezzar was the acme of Babylon’s worldly dominion. But the prosperity it enjoyed as a result of the collapse of Assyria might have been lost even more rapidly than it had been gained if the war between the Lydians and the Medes along the Halys had resulted in a clear victory for either of those two powers. Lands to the south, from Cilicia to Palestine and Mesopotamia, would surely have suffered if a single superpower had emerged. For that reason, Nabonidus (Herodotus’ Labynetus), representing Nebuchadnezzar, and Syennesis the king of Cilicia were keen to resolve the war of the Lydians and the Medes along the Halys, and to establish a rough equilibrium among all neighboring powers. Thereafter, each side looked for subtle signs in omens and oracles, and to the insights gained from ancient wisdom and world knowledge, indicating that the balance of worldly power and of divine justice had shifted in its favor. The first half of the sixth century, and particularly the era between the treaty on the Halys in 585 and the fall of Sardis to Cyrus in 547, was remembered in Greek tradition as the era of the Seven Sages. Including in their number such prominent men as Thales of Miletus, Solon of Athens, Chilon of Sparta, and Periander of Corinth, the fame of the Seven came in part from their travels to the courts of Sardis and Egypt, if not also to Babylon. Their collective reputation, and the favor with which several among them were received in the courts of the powerful, reflect the keen interest of this era in an understanding of the world and its relationship to orderly society, and ultimately to world sovereignty. The Seven were reputed to have formed their association in the name of Apollo after settling the disposition of a prize that was to be awarded “to the wisest.” Unlike the legendary Apple of Discord, which was to be given “to the fairest,” and which, by the will of Aphrodite, led to the war between Asiatics and Achaeans at Troy, a tripod said to have been pulled from the sea bearing the inscription To the Wisest produced gestures of deference among these men, who passed it from hand to hand until they agreed to dedicate it in common to Apollo The Sages were certainly aware of the fall of Assyria, and were witnesses to the competing claims to supremacy of Sardis, Egypt, Babylon, and Media. They were therefore aware of the fragility of the actual supremacy of any one of these powers, and their peaceful association may reflect their awareness that true world power could come only from collaborative harmony. Here was a significant conceptual development in the relationship between world knowledge and world power. Such a notion, on a small scale, had been the heart of a plan that Herodotus attributes to Thales for preserving Ionian independence by forming a league of Ionian cities participating in a common council at a central location. Anaximander expressed the same notion on a larger scale, as the balance of cosmic justice, and on his map he displayed its practical implications for the benefit of Croesus’ understanding of Lydia’s place in the balance of power in the world. If, according to Anaximander, “boundless nature” was the origin of “all the orders [kovsmoi]” that might arise in this world, then the only limitations on the physical extent of a sovereign power were, first, its ability to conform to justice and to benefit more than to suffer from retribution, and second, the physical extent of the oikoumene that it would dominate. Human understanding could best grasp the first of these conditions through some manner of consultative and deliberative process, and the second through a map of the world. Sardis lay close to the center of the world map, as it was drawn by Anaximander, but not at the precise center, for the world was divided by waters into two great continents. Across those waters from Sardis lay Sparta, then the most powerful state in Greece. Balance across this cosmic fulcrum was symbolized by alliance between Sardis and Sparta. The harmony of their names—Greek Sardis was Sfar[da-] in Lydian, Sapardu in Akkadian, Sprd in Aramaic, Sepharad in Hebrew, and Sparda in Persian—may have suggested the harmony of their interests. To gain an alliance with Sparta, Croesus pursued a long-term policy of courting Spartan favor by making impressive gifts to Apollo at Delphi and to the Spartans on behalf of Apollo. Croesus intensified his efforts in this undertaking especially after the world order established under Alyattes was upset by the overthrow of the Median dynasty by Cyrus in 550. As has been suggested above, Croesus’ piety was probably motivated by more than a simple desire to gain the support of the strongest military power in Greece. Through Apollo Croesus was seeking an affirmation that his ambitions were consistent with just order in the world. Croesus may also have acted in accordance with a sense of cosmic balance in this union of two powers poised on either side of the center of the earth. This notion derives support from one of the few items of information left to us about the life of Anaximander. We are told that Anaximander paid a visit to Sparta for the purpose of establishing a “solar indicator on ‘The Sundials.’” A solar indicator, a gnomon, was a device that could signify the relationship of the place where it was erected to the orbit of the sun through the path traced by the gnomon’s shadow. Anaximander’s gnomon and the monument called The Sundials were almost certainly related to the building near the agora of Sparta called The Sunshade (Skias) according to Pausanias, “where even today the Spartans meet in assembly; they say this Skias was the work of Theodorus the Samian.” Theodorus of Samos was a distinguished contemporary and intellectual peer of Anaximander, and was known to have worked for Croesus.

It is entirely plausible, therefore, that these two men came to Sparta together as representatives of Croesus and, in consummation of the Spartan alliance with him, participated in the founding of a house of assembly that included on it a conspicuous solar indicator, a gnomon (a device that the Greeks learned about from the Babylonians, according to Herodotus). A sundial and a building called the Skias were associated with sovereign deliberative bodies at Athens as well, in the century after Anaximander and Theodorus’ visit to Sparta. The tholos (round building) built in the agora of Athens as a meeting place for the fifty prytaneis, the presiding board of the Athenian council, was also called the Skias; the meeting place of the Athenian assembly on the Pnyx was marked by the sundial erected by the astronomer Meton. Before the construction of these Greek “sunshades” as meeting places for deliberative bodies, the skias was known in its original form as a portable royal sunshade, which was a conspicuous sign of the presence of sovereign authority in Assyrian and, later, Persian royal ceremony. With the visit of Anaximander to Sparta, this symbol of sovereignty was brought from the East to signify the seat of deliberative sovereignty at Sparta, the counterpart to the seat of Lydian sovereignty at Sardis, and a visible token of the cosmic relationships depicted theoretically on Anaximander’s map. A gnomon, in theory, could demonstrate the relationship of a place to a map of the earth. To an observer like Anaximander, who assumed a flat earth over which the sun rose everywhere at the same time, a gnomon (a vertical rod) was a means of calculating proximity to the apparent center of the earth. The shadow cast by a gnomon at midday, its shortest shadow, indicates the local meridian (north-south line). If the sun rose over a flat earth, only the meridian actually crossing the center point of the earth would exactly bisect the angle between sunrise and sunset. By comparing readings at different points, at substantial distances across the earth, early observers like Anaximander could hope to determine which points were closer to, and which points were farther from, the apparent center of the earth. In fact, because of the sphericity of the earth, every observable meridian lies exactly midway between sunrise and sunset, a fact that would initially encourage observers to believe that they were close to the mark. Only after a long accumulation of observations at many points, however, would the futility of seeking the center of the flat earth become evident. But by the time empirical science had proceeded this far, the tradition connecting monumental solar indicators with the center of the earth was well established as a symbol of sovereignty.”

- Mark Munn, The Mother of the Gods, Athens, and the Tyranny of Asia: A Study of Sovereignty in Ancient Religion. University of California Press, 2006. pp. 188-202

#oikoumene#οἰκουμένη#sovereignity#sovereign power#kingship#divine kingship#anaximander#world map#itinerary#oikist#archegetes#settlement#agricultural settlement#sundial#astronomy#agora#sparta#sardis#croesus#nebuchadnezzar#sargon#lydia#skias#royal sunshade#ritual practice#ritual procession#mother of the gods

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

#chekov’s crocodiles 🐊 have been deployed#I shall see you later crocodiles#stealing fire#lydias of Miletus#yeah they don’t need protection#they are big fucking crocodiles#ptolemy#sobek

0 notes

Text

[ Chapter 1 ] [ table of contents ] [ recap ] [ Chapter 9 ] [uquiz!]

Welcome to Athens and Sparta Adventures!

Reference map for Chapter 9 of Athens and Sparta Adventures. Characters may be added as they appear or are mentioned in the chapter. Updates on Saturdays, stay tuned!

This chapter has three concurrent storylines: one takes place in Corinth, one in Miletus, and one in Sardis.

New Readers: please note that this comic is not as mobile friendly as some other comics out there. Some directory links such as the table of contents only work on desktop, though mobile users should still be able to navigate using the bolded links above. I started writing this comic back in 2011 and reuploaded it to tumblr around 2018, which is why there’s significant gaps in both my consistency as a creator and in the changes in usability on this hellsite.

See below for brief Character Bios

Characters of Note

MAJOR CHARACTERS

Athens - The arrogant, egotistical and hubristic almost-capital of Greece. Athens’ more legitimate claims to hegemony are primarily his large navy and alliance of islands and city-states throughout the Aegean that purports to defend Greece from future Persian incursions. Although he is entering what we know as the “Golden Age” while the Parthenon and other such major renovations are nearing completion, Athens seems somewhat preoccupied with his vacation in Miletus...

Sparta - Known as Greece’s greatest warrior despite rarely finding reason to leave home on time, Sparta is uneasily resting after emerging somewhat victorious from the First Peloponnesian War. Although accepting a thirty year period of peace with rival Athens, Sparta finds the upstart city-state’s obsession with ‘democracy’ and the growing excuses to coerce new alliances increasingly worrisome. Curiously, he seems to have turned up in Sardis...

Corinth - The rich merchant city-state of Corinth has a vested interest in decreasing Athens’ power. Despite recently recovering her daughter-city of Megara, Corinth still finds others’ loyalties to her being tested. Frustrated by Sparta’s unwillingness to act on her warnings, Corinth suspects that a thirty years peace will do even less to stave off war in Greece. Recently however, she has been receiving disturbing omens...

Megara - Corinth's daughter city, formerly allied with Athens in the previous war to strategically block the path from the Peloponnese. After being herded back in league with the Peloponnesians, Megara is contemplating her divided allegiances and trying to adjust to living with her mother city again. Perhaps she can reach out to someone who might shed some insight on these troubles...