#ludwig hilberseimer

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

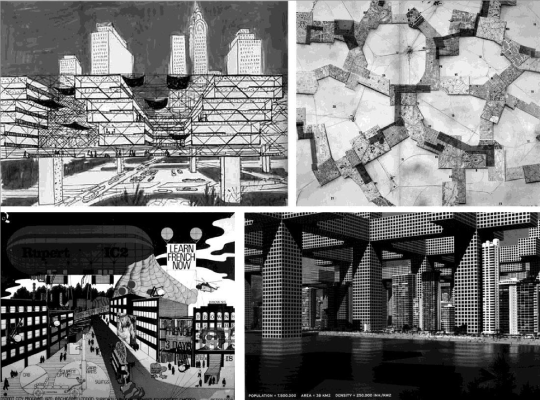

Highrise City (Hochhausstadt), 1924

Ludwig Karl Hilberseimer American, born Germany, 1885-1967

One of the central components of architect and planner Ludwig Hilberseimer’s treatise on urban planning of 1924 was a vertically integrated high-rise city where residents would live and work in one seamless unit, traveling up to apartments and down to factories in elevators. These drawings underscore the impersonal nature of Hilberseimer’s imagined society, removed from all identifying markers of history or geography. Although Hilberseimer would later renounce this project, the images remain as powerful expressions of modern architects’ preoccupation with functionalist models for urban society.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s and well into the early 1970s the example of Mies van der Rohe inspired countless younger architects to follow the master’s idiom. The Swiss architect Frank Geiser (*1935) belongs to the successful adepts of Mies who undoubtedly belongs to the country’s most significant architects working in steel. But although Geiser still regards the first 1956 issue of „Das Werk“ dedicated to the work of Mies, Ludwig Hilberseimer and Konrad Wachsmann as a quintessential representation of his architectural thinking, his preference for the square and clear geometry harks back to Geiser’s early acquaintance with art: during his training as a draftsman in Berne in the early to mid-1950s Geiser moved in the circles of the local avant-garde and himself made artworks in the style of the Art concret.

Following his training in Berne Geiser in 1956 moved to Ulm in Germany to study architecture at the legendary Hochschule für Gestaltung (HfG) where Herbert Ohl was his teacher and from which he graduated in 1960 with a diploma project about social housing. Afterwards he returned to Berne where he also established his office as early as 1962 and in the subsequent two decades realized a number of very Miesian projects, among them the Radio Schweiz high-rise (1969-72), single-family homes and

These projects and many others are featured in Konrad Tobler’s monograph „Frank Geiser. Architekt – Hauptwerke 1955–2015“, published in 2015 by Park Books. Tobler, based on a multitude of interviews conducted with the architect, elaborates on his formation and work. But the major part of the book is dedicated to a selection of projects from the 1960s to the present, all presented in comprehensive dossiers including photographs and plans. The featured projects demonstrate Geiser’s ability to make the Miesian idiom his own and how he rigorously refined the grid as basis of his architecture. And even though the 1980s saw him introduce postmodern elements these were always subordinated to the grid.

Tobler’s book on Frank Geiser is a beautifully designed and highly readable tribute to a lesser-known yet significant Swiss architect that is warmly recommended!

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yet another female artist let down by society... left for certain death... :(

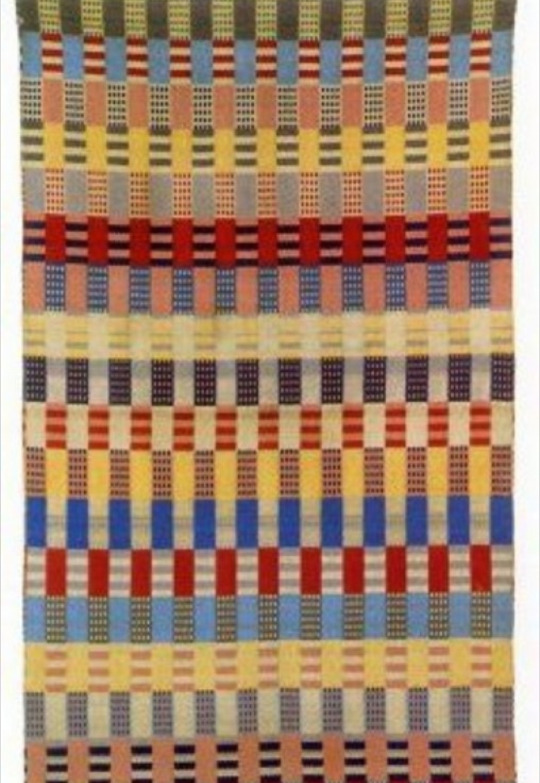

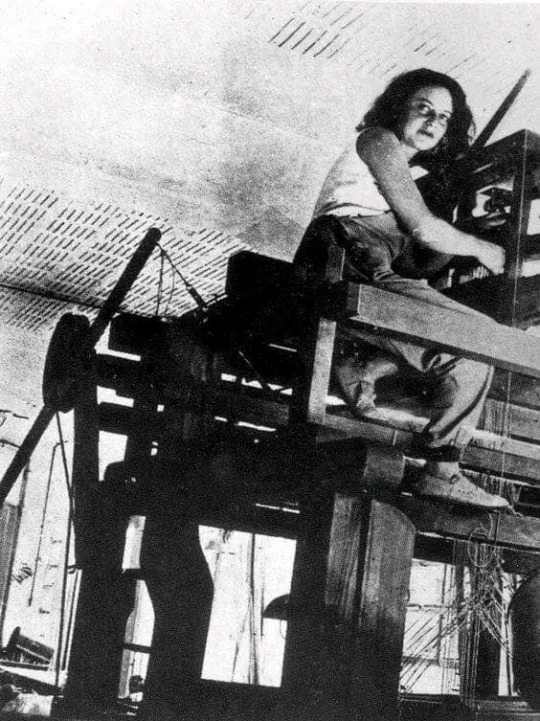

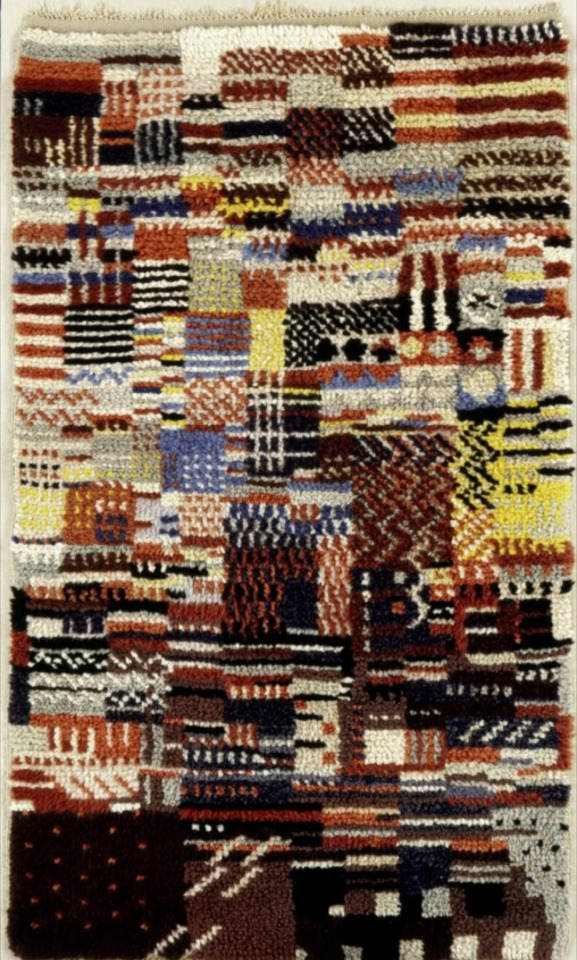

Otti Berger (4 October 1898 - 1944/45) was a textile artist and weaver. She was a student and later teacher at the #Bauhaus.

#HolocaustRemembranceDay

Berger was born in Zmajevac in Austro-Hungarian Empire (present-day Croatia). She completed education at the Collegiate School for Girls in Vienna before enrolling in the Royal Academy of Arts and Crafts in Zagreb, now the Academy of Fine Arts, University of Zagreb.

She continued her studies in Zagreb until 1926 before attending Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany. There, Berger studied under László Moholy-Nagy, Paul Klee, and Wassily Kandinsky, among others. Berger has been described as "one of the most talented students at the weaving workshop in Dessau."

...

Not allowed to work in Germany under Nazi rule because of her Jewish roots, Berger closed her company down in 1936. Berger fled to London, where attempts to emigrate to United States to work with her fiancee Ludwig Hilberseimer and other Bauhaus professors failed. She wrote to László Moholy-Nagy, Naum Gabo, Walter Gropius, and other friends trying to gain a teaching visa in 1937 but never acquired one.

Berger was unable to find steady work in London, in part because she did not speak the language, but also because she had impaired hearing, and no social circle.

Berger returned to Zmajevac in 1938 to help her family with her mother's poor health. From there, she was deported with her family to the Auschwitz concentration camp in April 1944, where she was murdered. Via Wikipedia

see also: Bauhaus 100: Otti Berger, Lost Woman of the Bauhaus (2019)

https://rachelwithane.com/womens-history/bauhaus-100-otti-berger-lost-woman-of-the-bauhaus

#womenofbauhaus #OttiBerger

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Otti Berger (4 October 1898 – 1944) was a textile artist and weaver. She was a student and later teacher at the Bauhaus. She was murdered in the Holocaust. Berger fled to London, where attempts to emigrate to United States to work with her fiancee Ludwig Hilberseimer and other Bauhaus professors failed. She wrote to László Moholy-Nagy, Naum Gabo, Walter Gropius, and other friends trying to gain a teaching visa in 1937 but never acquired one. Berger was unable to find steady work in London, in part because she did not speak the language, but also because she had impaired hearing, and no social circle. Berger returned to Zmajevac in 1938 to help her family with her mother's poor health. From there, she was deported with her family to the Auschwitz concentration camp in April 1944, where she was murdered.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

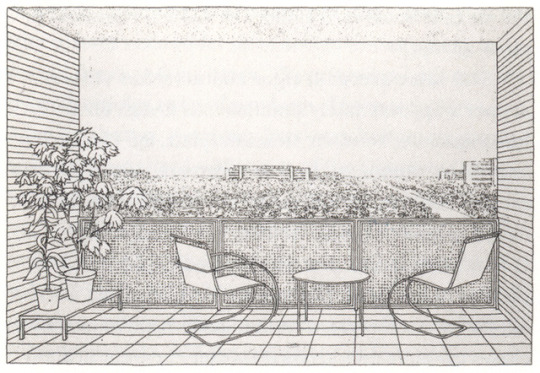

View from the Facade, a surface at the edge of the world - based on a drawing by Ludwig Hilberseimer

0 notes

Text

LAS CIUDADES UTÓPICAS

Utopía o utopia. (Del gr. οὐ, no, y τόπος, lugar: lugar que no existe).

1. f. Plan, proyecto, doctrina o sistema optimista que aparece como irrealizable en el momento de su formulación. (RAE)

¿Cómo dibujar la quimera, fantasía, invención, idealización, imaginación, ficción, anhelo, la ciudad ideal?

Desde la percepción de los espacios urbanos en los relatos utópicos clásicos (Aristóteles, Platón, Moro, Campanella), hasta las propuestas más imaginativas del siglo XX, se observa una evolución en el diseño y representación de las ciudades ideales.

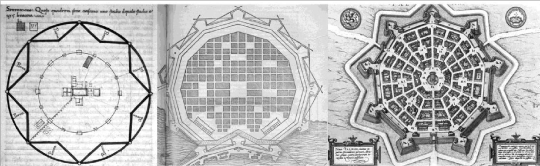

Partiendo de la proyección de la Utopía de Platón, se considera el círculo como la perfecta forma de la representación teórica del simbolismo platónico. Pero en el Renacimiento se debe considerar la incontestable influencia de las enseñanzas de la antigüedad romana y en especial los Diez Libros de la Arquitectura de Vitruvio. En el libro I describe las consideraciones fundamentales que deben ser tenidas en cuenta en el diseño de poblaciones: en ellos se defiende la forma circular frente a la cuadrícula, y no la octogonal, las torres serán circulares o poligonales para mejor defensa de la ciudad y el trazado interior tendrá una forma radio concéntrica, con ocho calles principales orientadas evitando la dirección de los vientos dominantes. La representación de esa “imagen mental” de las ciudades no se encuentra hasta el Renacimiento. Los trazos y líneas empiezan a dar forma a las urbes imaginadas, y a partir del siglo XV vieron la luz un gran número de publicaciones en donde se describían y representaban diseños de ciudades ideales. En todas ellas la expresión formal es la misma, imágenes de plantas, más o menos detalladas, con un claro componente defensivo; donde la regularidad de los trazados geométricos marca definitivamente los proyectos. Debemos considerar las propuestas de Antonio Averlino, Il Filarete, Pietro Cataneo o Vicenzo Scamozzi entre otros mucho interesantes autores.

Figura 1. Averlino Antonio di Pietro, il Filarete. Trattato di architettura, c. 1464 (izquierda). Pietro Cataneo, Quattro libri del l´Arquitettura, 1554 (centro). Vicenzo Scamozzi, Palma Nova, 1593 (derecha).

Como excepción se debe señalar el gran interés gráfico que tienen las imágenes de La Ciudad Ideal de da Vinci. Se cambia la forma de representar la urbe, a una escala más cercana a los usuarios, permitiendo un detalle arquitectónico imposible en las anteriores representaciones generales.

En ellos se adelanta varios siglos al proponer la separación del tráfico peatonal y el rodado, -dedicado principalmente al tráfico de mercancías- a diferentes niveles. Se puede comprobar una clara y directa relación con varias de las propuestas de ciudades ideales desarrolladas en el siglo XX. En especial la similitud de idea con La Ciudad Vertical de Ludwig Hilberseimer, proyecto de 1927 en el que se separan y estratifican en varios niveles los usos en búsqueda de una mejora en las circulaciones y salubridad de sus habitantes.

Figura 2. Leonardo da Vinci, la Ciudad Ideal, 1490 (abajo izquierda). Ludwig Hilberseimer, La Ciudad Vertical, 1927 (abajo derecha).

Los dibujos de la totalidad de la ciudad o vistas desde distancias muy lejanas, en donde es fácil apreciar el conjunto de la propuesta urbana, serán una constante hasta entrado el siglo XX.

Ya en los inicios del siglo pasado las innovaciones sobre la circulación de vehículos y los proyectos regulados por vías de comunicación en altura fueron impulsadas tempranamente por Eugene Hénard (1849-1923). En 1905 publicó una obra en la que proponía la ciudad futurista cuyo subsuelo estaría programado para la instalación de los sistemas de infraestructuras, saneamiento y por donde pasarían los transportes públicos. En La ciudad del futuro, se abre camino a una nueva forma de representación de las ciudades imaginadas al acercar la escala al hombre. Un viaje al mundo imaginado que nos remitiría a los esbozos futuristas de Gustavo Sant Elía en su Città Nuova de 1914, con calles que perforaban el suelo y pasarelas peatonales que se entrecruzaban en diferentes niveles entre los edificios, vinculadas con torres de ascensores que funcionaban como “calles verticales” para personas y servicios.

A lo largo del siglo XX las propuestas de Moses King, The Cosmopolis of the Future (1908), la Ciudad Industrial (1917) de Garnier , Plan Voisin de Paris (1925) de Le Corbusier, Richard Neutra con la Rush City Reformed en 1925, la ya nombrada La Ciudad Vertical (1927) de Hilberseimer, Metropolis of Tomorrow (1931) de Hugh Ferriss, o The Living City (1958) de Frank Lloyd Wright, son algunos de los interesantes proyectos de ciudad imaginada en los que se pueden encontrar dibujos que explican cómo se desarrolla la vida en esas ciudades.

Figura 4. Yona Friedman, La Ville Spatiale, 1958 (arriba izquierda). New Babylon, Constant Nieuwenhuys, 1956-1974 (arriba derecha). Archigram, Instant City, 1968–70 (abajo izquierda). MVRDV, Benidorm, 2002 (abajo derecha).

Y en la actualidad, ya en el siglo XXI, ¿cómo dibujarán nuestros alumnos estos mundos imaginarios?, ¿Dónde estarán, cómo serán, cómo vivirán, de qué materiales estarán construidas las utopías modernas?

0 notes

Photo

Mário Bonito 1OO anos | 23.09 - 31.12 2021

17.12: [conferência] Marco De Michelis | Evocação da Circunstância V, Auditório da Casa das Artes - Porto

O arquiteto Marco De Michelis estará pela primeira vez no Porto, a 17 de dezembro, para a apresentação de “Heinrich Tessenow as a modern architect”. A conferência acontecerá na Casa das Artes – Porto, pelas 18:30, no âmbito da celebração dos 100 anos do nascimento de Mário Bonito.Marco De Michelis estudou arquitetura em Veneza, onde foi docente de História da Arquitetura e fundador e reitor da Faculdade de Artes e Design. Foi bolseiro da Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (Berlim e Munique) e do Getty Center, em Santa Mónica, CA. Entre 1999 e 2003, foi nomeado “The Walter Gropius Professor” pela Bauhaus University, de Weimar e, em 2005, foi-lhe atribuída a “Mellon Senior Fellow” pelo CCA/Montreal. É Professor Convidado em Hamburgo e em Leeds; na Cooper Union, na Columbia University e na New York University/IFA.Publica extensivamente sobre arquitetura e arte contemporânea, nomeadamente sobre Heinrich Tessenow, Walter Gropius, Ludwig Hilberseimer, Bauhaus, Bruce Nauman. Foi o editor de “Ottagono” (1989-1991) e o curador principal da Trienal de Milão, entre 1993 e 1996.

Marco De Michelis será apresentado por José Miguel Rodrigues.

www.mariobonito100anos.com

Organização: Matéria. Conferências Brancas em parcecia com Casa das Artes – Porto | Patrocinador: Jofebar – Panoramah!

0 notes

Photo

WERKBUNDAUSTELLUNG 1927 Stuttgart

#die wohnung#werkbundausstellung#architecture#ciam#Le Corbusier#weißenhofsiedlung#stuttgart#germany#apartment#mies van der rohe#behrens#josef frank#hans scharoun#ludwig hilberseimer#archdaily#living#space#architect#design#poster#dezeen#juliaknz#graphic

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Highrise city Berlin, Germany 1924–1927 Ludwig Hilberseimer (1885–1967), architect Adam Caruso (1962–), model

#ludwig hilberseimer#1920s#20th century#berlin#germany#europe#adam caruso#architecture#infrastructure#urban#ideal cities#patterns#vertical architecture

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Francois-Joseph Belanger, Garden of Monsieur de Ste. James at Neuilly, France, 1785 VS Ludwig Hilberseimer, Highrise City (Hochhausstadt) | Perspective View: North-South Street, 1924

#Ludwig Hilberseimer#francois-joseph belanger#garden#drawing#architecture#collage#collage art#cut and paste#highrise city#Hochhausstadt

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Werkbund Ausstellung "Die Wohnung", Weissenhof Stuttgart

1927

#josef frank#jjp oud#jacobus johannes pieter oud#mart stam#le corbusier#pierre jeanneret#peter behrens#richard döcker#walter gropius#ludwig hilberseimer#ludwig mies van der rohe#mies van der rohe#hans poelzig#adolf rading#hans scharoun#adolf gustav schneck#bruno taut#max taut#style international#weissenhof#stuttgart

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rheinlandhaus (1926) in Berlin, Germany, by Ludwig Hilberseimer & Heinrich Kosina

#1920s#commercial building#modernism#modernist#architecture#germany#architektur#berlin#ludwig hilberseimer#heinrich kosina

205 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ludwig Hilberseimer (1955), The Nature of Cities

Washington decentralized.

0 notes

Photo

Ludwig Hilberseimer - New City : Principles of Planning, 1944

pinterest

350 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ludwig Hilberseimer. Vertical City

187 notes

·

View notes

Text

View from the Facade, a surface at the edge of the world - based on a drawing by Ludwig Hilberseimer

0 notes