#lowndes county

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

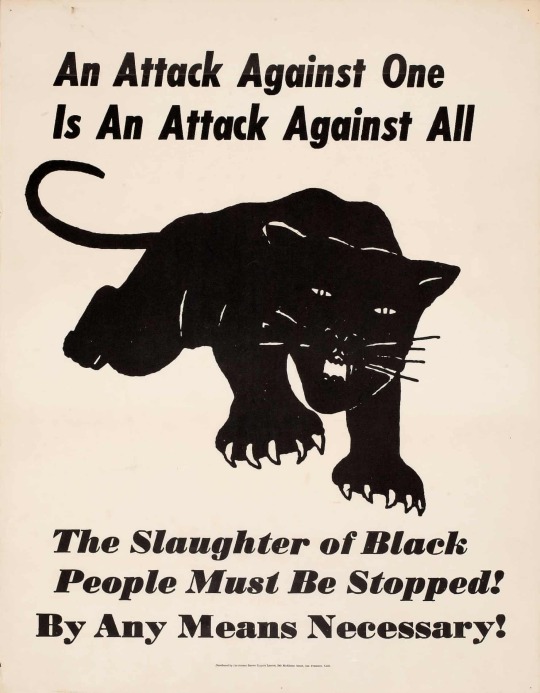

Power to the people: the branding of the Black Panther party

An Attack Against One Is an Attack Against All, 1968 Designer Unknown

The history of the logo can be traced back to designer Ruth Howard, a member of the Atlanta branch of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee where she learned how visuals could galvanize a community. In 1966, SNCC organizers in Lowndes county approached her to create the symbol. Howard originally designed a dove to express power and autonomy but it wasn’t well received. She eventually based it on the school mascot of Clark College, a local HBCU. Dorothy Zeller, a white Jewish woman, added whiskers and the black color

Photograph: The Merrill C Berman Collection

#the merrill c berman collection#black panther party#an attack against one is an attack against all#poster#activism#history#student nonviolent coordinating committee#lowndes county#georgia#ruth howard#designer#dorothy zeller#clark college

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m greatly tired of hiding this from the public.

CW// DESCRIBED SEXUAL ASSAULT/ABUSE

This blog is about my sexual abuser, Dean Evans Hunter. I attended Lowndes High School with him (I graduated in 2021) and he sexually assaulted me for two weeks in February of 2020. He was 18 years old and I was 17. I was very vulnerable at the time because my girlfriend had just broken up with me awhile before. We sat together at lunch and bonded over our love for music and Pokémon. We would play Pixelmon and voice call on Discord after school when we had time. Whenever we would leave the lunchroom and go to our separate classes, he would hug me and often grope my chest or ass. Mind you that school has about 3,000+ students, so we had ALOT of eyes on us. No one stopped him. It made me very uncomfortable and would ask him to stop, but he refused and played it off as a joke. There was one point where I had even yelled and hit him to stop, but he didn’t take me seriously at all. I was young and naive at the time, so I had very foolishly developed a crush on him. At one point, I confessed to him over call on Discord, but he never gave me a solid answer on if he was already in a relationship or not. He still continued to grope me and prey on me. When I had found out he already had a girlfriend, I was very upset that he had led me on and was preying on me. I didn’t have anyone else to sit with at lunch, so I sat at our table and just ignored him. He kept asking me what was wrong, and after I continued to not reply, He grabbed my face and nearly forced me to kiss him to get me to talk. I pulled away from him and was luckily saved by the bell. I quickly walked away from the table but he followed after me. He tried to grab me again but I just kept moving through the crowd to get to my class. I was terrified for my life. After I broke contact with him and told friends what he did to me, he proceeded to call me a lying bitch. I tried speaking with my school counselor about it, but unsurprisingly nothing was done. He got to graduate with zero repercussions. Lowndes High School also has a history of similar behavior, letting terrible people run scott-free on their school grounds.

I am severely traumatized by the things he has said and done to me. It has given me numerous nightmares over the years and has caused me to be afraid of men. I also had a mild case of agoraphobia when Covid hit later that year. I was terrified to leave my house and scared to even be at school because I was afraid he was going to find me and hurt me again.

I don’t have any physical evidence anymore because it was years ago and I lost the journal I logged my experience in, but I do know there are multiple other victims out there. I do, however have screenshots of previous twitter posts of mine speaking of my experience with him from past years and a picture of me wearing one of his hoodies. If you or someone you know has had a similar experience with him, please reach out to me. You can remain anonymous if you wish.

If you see this, you don’t get the privilege of hiding from this, Dean. I will air this shit out as far as possible to make sure you NEVER forget what you did to me and other young women. You are a predator. You do not deserve to have a social platform or any sort of kindness in your life after the things you have done. There is no hope for you to change.

#dean evans hunter#dean hunter#lowndes#lowndes high school#lowndes highschool#lowndes county#lowndes county schools#valdosta#valdosta georgia#georgia

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

has the nonviolent integrated path the Black DOS Community in the USA chose, been worth it ? https://aalbc.com/tc/topic/10268-has-the-nonviolent-integrated-path-the-black-dos-community-in-the-usa-chose-been-worth-it/ #rmaalbc

0 notes

Text

Stokely Carmichael, Lowndes County, Alabama, 1966, printed 2022, gelatin silver print, courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation.

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kennel Quilts

Hurricane Helene has left people without homes, and many pets are now in shelters. Kennel quilts are very much needed, and are a low budget option for those with limited supplies and time.

Here's the FB page for Kennel Quilts. If you're on FB, I suggest following them. If you don't use FB, got to the link below to sign up for their mailing list. Emails are sent out only when a kennel quilts are needed.

If you can't make a quilt, but would still like to help, you have the option to donate to Petfinder here.

25 kennel quilts can fit into a medium size USPS flat rate box. These are not large quilts. Here are guidelines and free patterns you can download and use for making these. The finished size is about 12x18 inches, the same size as most placemats. This is the form to print and include with the quilts you finish and donate.

These are shelters listed in the various emails I receive from Kennel Quilts:

Humane Society of Sarasota County 2331 15th Street Sarasota, FL 34237

Cat Depot, Inc. 2542 17th Street Sarasota FL 34234

SPCA Florida 5850 Brannen Road S. Lakeland, FL 33813 Attn: Shelley Thayer

Suwannee Valley Humane Society 1156 S E Bisbee Loop Madison, FL 32340

Appalachian Highlands Humane Society 2101 W. Walnut Street Johnson City, TN 37604

Friends of Greeneville-Greene County TN Humane Society 400 N. Rufe Taylor Road Greeneville, TN 37745-2030

Asheville Humane Society 14 Forever Friend Lane Asheville, NC 28806 Attn: Jessica Moore

Humane Society of Valdosta Lowndes County 1740 W. Gordon Street Valdosta, GA 31601

Forsyth Humane Society 4881 Country Club Road Winston-Salem, NC 27104

Watuaga Humane Society has two shipping option:

For USPS: Watuaga Humane Society PO Box 1835 Boone, NC 28607 For UPS or Fedex: Watuaga Humane Society 312 Paws Way Boone, NC 28607

Alaqua Animal Refuge 155 Dugas Way Freeport, FL 32439-3357

Peyton Davis Humane Society of Pinellas 3040 State Route - 590 Clearwater, FL 33759

Gulf Coast Humane Society 2010 Arcadia Street Fort Myers, FL 33916 Attn: Lori Burke

Hope for Brevard 1465 Cypress Avenue Melbourne, FL 32935

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

KWAME TURE BLASTS AFRICAN BOURGEOISIE

On this day in 1998, Pan-African revolutionary and icon Kwame Ture died in Guinea, Conakry. Born on 29 June 1941, Ture, formerly known as Stokely Carmichael, moved to the United States from Trinidad with his family at 11. He led a life marked by a strong dedication to the Pan-African cause. In his mid-20s, he became chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which primarily focused on organising and mobilising Black people in the US South to exercise their voting rights. He later oversaw SNCC members who co-founded the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, an SNCC affiliate focused on registering Black voters in Lowndes County, Alabama. Ture was at the forefront of this struggle throughout the 1960s, from the Freedom Rides (challenging segregation at bus stops) to the rise of the Black Power Movement. He later helped found the All-African People's Revolutionary Party. The majority of Ture's last three decades were spent in the West African nation of Guinea, a testament to his commitment to Pan-Africanism. Here, he adopted the name ‘Kwame Tureaud in honour of Ghana's founding leader and Pan-African icon Kwame Nkrumah and Guinea's then-president Sékou Touré, two revolutionaries he drew a lot of inspiration from.

Despite becoming friends with many African leaders during his time on the continent, Ture never held back from calling out the worst tendencies of the African bourgeoisie. He pointed out that it was essential to understand that not all Africans are on the side of the masses and revolutionaries. In remembrance of this great son of Africa, here is a 1989 clip of him exposing the African bourgeoisie.

My comment: Bro Kwame, all I see are beautiful, black humans being corrupted into consumatronic zombies by Whiteness and capitalism. Until we remove that veil of idiocy and outright drunken adultery, Blk ppl will NEVER be free.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elmore Bolling, he was too successful.

Elmore Bolling, whose brothers called him Buddy, was a kind of one-man economy in Lowndesboro, Ala. He leased a plantation, where he had a general store with a gas station out front and a catering business; he grew cotton, corn and sugar cane. He also owned a small fleet of trucks that ran livestock and made deliveries between Lowndesboro and Montgomery. At his peak, Bolling employed as many as 40 people, all of them African like him.

One December day in 1947, a group of white men showed up along a stretch of Highway 80 just yards from Bolling’s home and store, where he lived with his wife, Bertha Mae, and their seven young children. The men confronted him on a section of road he had helped lay and shot him seven times — six times with a pistol and once with a shotgun blast to the back. His family rushed from the store to find him lying dead in a ditch.

The shooters didn’t even cover their faces; they didn’t need to. Everyone knew who had done it and why. “He was too successful to be a Negro,” someone who knew Bolling told a newspaper at the time. When Bolling was killed, his family estimates he had as much as $40,000 in the bank and more than $5,000 in assets, about $500,000 in today’s dollars. But within months of his murder nearly all of it would be gone. White creditors and people posing as creditors took the money the family got from the sale of their trucks and cattle. They even staked claims on what was left of the family’s savings. The jobs that he provided were gone, too. Almost overnight the Bollings went from prosperity to poverty. Bertha Mae found work at a dry cleaner. The older children dropped out of school to help support the family. Within two years, the Bollings fled Lowndes County, fearing for their lives.

Elmore Bolling and his wife, Bertha Mae Nowden Bolling, in Alabama circa 1945.

#elmore bolling#bolling#alabama#creditors#african#kemetic dreams#africans#afrakan#brownskin#brown skin#afrakans#business#african american#bertha mae

272 notes

·

View notes

Photo

William "Bill" Traylor (1853–1949) was an African-American self-taught artist from Lowndes County, Alabama. Born into slavery, Traylor spent the majority of his life after emancipation as a sharecropper. It was only after 1939, following his move to Montgomery, Alabama that Traylor began to draw.

At the age of 85, he took up a pencil and a scrap of cardboard to document his recollections and observations. From 1939 to 1942, while working on the sidewalks of Montgomery, Traylor produced nearly 1,500 pieces of art.

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dark Nights in Georgia

Hurricane Helene’s winds surged in strength as the storm churned over unusually warm waters in the Gulf of Mexico and closed in on the Florida Panhandle and southern Georgia on September 26, 2024. When the deadly Category 4 storm struck Florida’s Big Bend area and then pushed north, winds in some areas exceeded 140 miles per hour (225 kilometers per hour)—strong enough to snap trees, tear the roofs off buildings, and topple power lines.

After the storm passed, millions of people across several states were left without electricty. The Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the NOAA-NASA Suomi NPP satellite has a low-light sensor, the day-night band, that measures nighttime light emissions and reflections. It captured views of some of those losses in hard-hit communities in Georgia, including Augusta (above), Savannah (below), and Valdosta (second pair below).

Scientists with the Black Marble Project at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Science Systems and Applications, Inc., and the University of Maryland, College Park, processed VIIRS data to show nighttime lights before and after Helene passed through the Southeast. Data from September 28 were compared to a pre-storm composite (August) and overlaid on landcover data collected by the Landsat 8 and 9 satellites. These three cities were not the only communities in Georgia that lost power.

Data published by Georgia Power showed that power had been restored to more than 840,000 customers by October 1. However, more than 400,000 Georgians still lacked power on that date, including 65,000 customers in Richmond County (Augusta), 38,000 in Chatham County (Savannah), and 40,000 in Lowndes County (Valdosta), according to data compiled by PowerOutage.us. More than 61,000 customers in Florida, 589,000 in South Carolina, and 383,000 in North Carolina were also without power on October 1.

Precision is critical for studies of night lights, said Ranjay Shrestha, a scientist based at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and member of the Black Marble team. Raw, unprocessed images can be misleading because moonlight, clouds, pollution, seasonal vegetation—even the position of the satellite—can change how light is reflected and distort observations. The processing by the Black Marble team accounts for such changes and filters out stray light from sources that are not electric lights.

“Satellite-derived nighttime lights products like Black Marble are invaluable for capturing widespread outages in distributed energy systems,” said Shrestha. “These images not only reveal the immediate impact of disasters at the neighborhood scale but also provide insights into recovery trends over time, aiding in response, resource allocation, and damage assessment.”

The rate at which power is restored after hurricanes can vary significantly based on a variety of factors. Researchers from Florida Atlantic University and Georgia State University analyzed VIIRS data from Hurricane Ian, which roared across Florida in September 2022, and found notable differences in power restoration rates between urban and rural areas and between disadvantaged and more affluent communities.

NASA’s Disasters Response Coordination System has been activated to support agencies responding to the storm, including the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Florida Division of Emergency Management. The team will be posting maps and data products on its open-access mapping portal as new information becomes available about flooding, power outages, precipitation totals, and other topics.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using Black Marble data courtesy of Ranjay Shrestha/NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Story by Adam Voiland.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#youtube#gangstalking#targeted individuals#corrupt law enforcement#criminal stalking#richard moore#united states anti gang stalking association#u.s. anti gang stalking#north mississippi anti gang stalking association#havana syndrome

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edgar Daniel Nixon (July 12, 1899 – February 25, 1987) known as E. D. Nixon, was a civil rights leader and union organizer in Alabama who played a crucial role in organizing the landmark Montgomery bus boycott.

A longtime organizer and activist, he was president of the local chapter of the NAACP, the Montgomery Welfare League, and the Montgomery Voters League. He had led the Montgomery branch of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters Union, known as the Pullman Porters Union, which he had helped organize.

Martin Luther King Jr. described him as “one of the chief voices of the Negro community in the area of civil rights,” and “a symbol of the hopes and aspirations of the long oppressed people of the State of Alabama.”

He was born in rural, majority-African-American Lowndes County, Alabama to Wesley M. Nixon and Sue Ann Chappell Nixon. As a child, Nixon received 16 months of formal education, as African American students were ill-served in the segregated public school system. His mother died when he was young, and he and his seven siblings were reared among extended family in Montgomery. His father was a Baptist minister.

After working in a train station baggage room, he rose to become a Pullman car porter, which was a well-respected position with good pay. He was able to travel around the country and worked steadily. He worked with them until 1964. In 1928, he joined the new union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, helping organize its branch in Montgomery. He served as its president for many years.

He married Alease Curry (1927-1934). She died in 1934. They had a son, Edgar Daniel Nixon Jr. (1928–2011) who became an actor known by the stage name of Nick LaTour. He married Arlet Campbell. She was with him during many of the civil rights events. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rep. Kelvin Lawrence, D-Hayneville, enters the Alabama House of Representatives on Feb. 8, 2024 in Montgomery, Alabama. (Brian Lyman/Alabama Reflector)

The Alabama Attorney General’s Office said Tuesday that Rep. Kelvin Lawrence, D-Hayneville, had been arrested on felony charges.

The office said in a statement that Lawrence was charged with second-degree forgery and with second-degree criminal possession of a forged instrument.

“The indictment alleges that Lawrence, with the intent to defraud, falsely made, completed, or altered a builder’s license,” the statement said.

A copy of the indictment was not immediately available Tuesday morning. Messages seeking comment were left with Lawrence on Tuesday and with the attorney general’s office.

Both charges are Class C felonies, punishable by up to 10 years in prison.

The statement said the case is being prosecuted by the Attorney General’s office of Special Prosecutions Division.

Lawrence was first elected to the House in 2014, and is currently serving his third term representing House District 69, which includes portions of Autauga, Lowndes, Montgomery and Wilcox counties.

Alabama House Speaker Nathaniel Ledbetter, R-Rainsville, said in a statement that he expects representatives “to hold themselves to the highest standard of integrity in both their personal and professional lives.”

“Rep. Kelvin Lawrence’s indictment presents an unfortunate situation for his constituents and colleagues alike. I have full confidence in our justice system’s ability to assess the facts of this case and determine an appropriate course of action,” Ledbetter said in a statement.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHRONOLOGY OF AMERICAN RACE RIOTS AND RACIAL VIOLENCE p-5

1961 May First Freedom Ride. 1962 Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited (HARYOU) is founded. Robert F. Williams publishes Negroes with Guns, exploring Williams’ philosophy of black self-defense. October Two die in riots when President John F. Kennedy sends troops to Oxford,Mississippi, to allow James Meredith to become the first African American student to register for classes at the University of Mississippi. 1963 Publication of The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin. Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) is founded. April Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., writes his ‘‘Letter from Birmingham Jail.’’

June Civil rights leader Medgar Evers is assassinated in Mississippi. August March on Washington; Rev. King delivers his ‘‘I Have a Dream’’ speech before the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.

September Four African American girls—Carol Denise McNair, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, and Addie Mae Collins—are killed when a bomb explodes at theSixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. 1964 June–August Three Freedom Summer activists—James Earl Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner—are arrested in Philadelphia, Mississippi; their bodies are discovered six weeks later; white resistance to Freedom Summer activities leads to six deaths, numerous injuries and arrests, and property damage acrossMississippi. July President Lyndon Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act. New York City (Harlem) riot. Rochester, New York, riot. Brooklyn, New York, riot. August Riots in Jersey City, Paterson, and Elizabeth, New Jersey. Chicago, Illinois, riot. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, riot. 1965 February While participating in a civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, Jimmie Lee Jackson is shot by an Alabama state trooper. Malcolm X is assassinated while speaking in New York City. March Bloody Sunday march ends with civil rights marchers attacked and beaten by local lawmen at the Edmund Pettus Bridge outside Selma, Alabama. Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) is formed in Lowndes County,Alabama. First distribution of The Negro Family: The Case for National Action, better known as The Moynihan Report, which was written by Undersecretary of Labor Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Nathan Glazer. July Springfield, Massachusetts, riot. August Los Angeles (Watts), California, riot. 1965–1967 A series of northern urban riots occurring during these years, including disorders in the Watts section of Los Angeles, California (1965), Newark, New Jersey (1967), and Detroit, Michigan (1967), becomes known as the Long Hot Summer Riots. 1966 May Stokely Carmichael elected national director of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). June James Meredith is wounded by a sniper while walking from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi; Meredith’s March Against Fear is taken up by Martin Luther King, Jr., Stokely Carmichael, and others. July Cleveland, Ohio, riot. Murder of civil rights demonstrator Clarence Triggs in Bogalusa, Louisiana. September Dayton, Ohio, riot. San Francisco (Hunters Point), California, riot. October Black Panther Party (BPP) founded by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale. 1967

Publication of Black Power: The Politics of Liberation by Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton. May Civil rights worker Benjamin Brown is shot in the back during a student protest in Jackson, Mississippi. H. Rap Brown succeeds Stokely Carmichael as national director of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Texas Southern University riot (Houston, Texas). June Atlanta, Georgia, riot. Buffalo, New York, riot. Cincinnati, Ohio, riot. Boston, Massachusetts, riot. July Detroit, Michigan, riot. Newark, New Jersey, riot. 1968 Publication of Soul on Ice by Eldridge Cleaver. February During the so-called Orangeburg, South Carolina Massacre, three black college students are killed and twenty-seven others are injured in a confrontation with police on the adjoining campuses of South Carolina State College and Claflin College. March Kerner Commission Report is published. April Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., is assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. President Lyndon Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1968. Washington, D.C., riot. Cincinnati, Ohio, riot. August Antiwar protestors disrupt the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. 1969 May James Forman of the SNCC reads his Black Manifesto, which calls for monetary reparations for the crime of slavery, to the congregation of Riverside Church in New York; many in the congregation walk out in protest. July York, Pennsylvania, riot. 1970 May Two unarmed black students are shot and killed by police attempting to control civil rights demonstrators at Jackson State University in Mississippi. Augusta, Georgia, riot. July New Bedford, Massachusetts, riot. Asbury Park, New Jersey, riot. 1973 July So-called Dallas Disturbance results from community anger over the murder of a twelve-year-old Mexican-American boy by a Dallas police officer. 1975–1976 A series of antibusing riots rock Boston, Massachusetts, with the violence reaching a climax in April 1976. 1976 February Pensacola, Florida, riot. 1980 May Miami, Florida, riot. 1981 March Michael Donald, a black man, is beaten and murdered by Ku Klux Klan members in Mobile, Alabama. 1982 December Miami, Florida, riot. 1985 May Philadelphia police drop a bomb on MOVE headquarters, thereby starting a fire that consumed a city block. 1986 December Three black men are beaten and chased by a gang of white teenagers in Howard Beach, New York; one of the victims of the so-called Howard Beach Incident is killed while trying to flee from his attackers. 1987 February–April Tampa, Florida, riots. 1989 Release of Spike Lee’s film, Do the Right Thing. Representative John Conyers introduces the first reparations bill into Congress—the Commission to Study Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act; this and all subsequent reparations measures fail passage. August Murder of Yusef Hawkins, an African American student killed by Italian-American youths in Bensonhurst, New York. 1991 March Shooting in Los Angeles of an African American girl, fifteen-year-old Latasha Harlins, by a Korean woman who accused the girl of stealing. Los Angeles police officers are caught on videotape beating African American motorist Rodney King. 1992 April Los Angeles (Rodney King), California, riot. 1994 Survivors of the Rosewood, Florida, riot of 1923 receive reparations. February Standing trial for a third time, Byron de la Beckwith is convicted of murdering civil rights worker Medgar Evers in June 1963.

19 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

Wild Jaw-dropping Body cam footage captured by Georgia Police shows the moment as a distracted woman drove and launched her vehicle off a parked tow truck ramp in Lowndes County, Georgia last week. Amazingly nobody was killed in the accident only the driver got injured

13 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Car Launches Off Tow Truck Ramp in Lowndes County, Georgia Crazy shit... 👀

1 note

·

View note

Text

In early 2010, amid the mounting job losses and growing budget deficits of the Great Recession, the conservative radio commentator Rush Limbaugh took to the air to warn his listeners of a group of “freeloaders . . . [who] live off of your tax payments and they want more. . . . They don’t produce anything. They live solely off the output of the private sector.” They were, he explained on another show, “parasites of government.” Wisconsin governor Scott Walker described members of the same group as the “haves” and the “taxpayers who foot the bills” as the “have-nots.” Indiana’s governor Mitch Daniels labeled the group’s members “a new privileged class in America.” The charges rehearsed by Limbaugh and others draw from an enduring discourse of producerism in US political culture, in which the virtuous, striving, and browbeaten producer struggles to fend off the parasite, a dependent subject that consumes tax dollars and productive labor to subsidize a profligate and excessive lifestyle. These representations have long been racialized and gendered; subjects marked as “welfare queens” and “illegal aliens,” among others, have been similarly condemned as freeloaders and parasites who feed off the labor of hardworking (white) taxpayers. The focus of Limbaugh’s scorn, however, was a group of wage earners rarely represented on the latter side of the producerist–parasite divide: public-sector workers and their unions. While women and people of color constitute a larger proportion of state and municipal workers in comparison with the private sector, 70 percent of this workforce in 2011 was still identified as white, and nearly a third were white men. Indeed, in Wisconsin, the site of the highest profile attack on public-sector workers, whites are slightly overrepresented in the public-sector workforce compared with the overall population of the state, while Black and Latino workers are slightly underrepresented. Yet their whiteness did not indemnify significant numbers of public-sector workers from these attacks. Emergency workers, lifeguards, city and county employees, teachers, and other school employees became increasingly criticized as parasitic—excessive, indulgent, dependent, and a threat to the body politic. As Minnesota governor Tim Pawlenty explained after the election, “Unionized public employees are making more money, receiving more generous benefits, and enjoying greater job security than the working families forced to pay for it with ever-higher taxes, deficits and debt.” [...] How did public-sector workers come so easily to symbolize the cause of the 2008 recession, and thus become the object of widespread political attack? They reflect, we argue, the most recent development of a racialized antistatist politics. The rise of the modern Right in the United States was articulated through an antipathy to state power in which the redistributive state as a whole was stigmatized through its association with racialized dependents. With the demobilization of the Black freedom movement in particular and the withering of the welfare state, antistatist projects have sought to extend this logic to white beneficiaries of state action. Thus, in the contemporary age of inequality, commitments to state-sponsored “affirmative action for whites” that were long guaranteed in the postwar era have become vulnerable. The use of racialized antistatism to assail public-sector unions more generally is an example of what we call racial transposition: a process through which the meaning, valence, and signification of race can be transferred from one context, group, or setting to another.

“Parasites of Government”: Racial Antistatism and Representations of Public Employees amid the Great Recession by Hosang and Lowndes (2016)

1 note

·

View note