#louis xvi and his trial

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Niels Schneider as Saint-Just in Un peuple et son roi (2018)

#saint just#saint-just#antoine saint just#louis xvi and his trial#louis antoine saint-just#un peuple et son roi

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

— Яitual ²

Rockstar!Ellie Williams x Vampire!Reader (w/c: 2.5k)

DO NOT BUY TLOU

AO3 PART ¹/SERIES MAS.

⚠︎ WARNINGS +18 MINORS/MEN DNI, blood consumption, angst (kinda), mentions of infidelity, backstory chapter in a way, less dialogue, less ellie, vampire!abby anderson, references, sex, death, weapons, mentions of religion no mentions of readers skin colour or hair texture.

ⓘ A/N: i’m so sorry pretty people the second part is coming out this late :(, luv yall pls enjoy and share with me your thoughts and ideas about our cuckoo gals<3 also if there's any warning i failed to mention tell me.

The two infamous covens, a divine picture drawn to the naked eye, a unity, somewhere you could belong-at least that’s what they told everyone when they preached their sermons. Although the consequences included losing your soul for a higher connection..some might claim it was worth it.

All the pain and all the agony started with Selene for Aaron questioned why she bit into the snake when she was asked to not give into the temptation by Kanchelsis—the god of the underworld. It wasn't the apple hanging high from up the tree she was after, she had her eyes set on the shimmering green snake, she smelled the blood and tasted the flesh before she even pierced her canines into the flailing reptile.

What everyone failed to know is that the highest mother was carrying a child when she started feeding on her mortal dutiful husband for he was the only one she was allowed to feed on—as demanded by kanchelsis. bringing forth the mankind of vampires and the formation of the first ever coven to go down in the books, The Ancients. They were and still are known for their reserved nature, never seeking or raising their children to be anything other than thankful and graceful with the humankind.

Selene’s pregnancy went as smooth as it could but it was naught without losses, it seemed that her feeding off of her husband wasn’t the safest option for she killed him whilst giving birth in a moment of utter fury, she sat in the water tub in total shock and distress whilst she was encouraged to push by her maker and the servants surrounding her thrashing body in a circle

Tears well up in her eyes “i cannot bear his child..orphaned, i beg of you my lord”

He ignores her pleas, focusing on the task at hand of making her deliver a healthy child. “Push my lady” squeezing her hand in his long clawed one, her agonizing scream reverberating off the walls of the chamber and into the dark night, awakening all types of demons and creatures alike.

“I can see this head! Come on push my highest mother! Push” the shrill cries of the fragile babe with the tiniest of canines for teeth can be heard by everyone in the chamber prompting them to sigh in relief including the mother who is drenched in sweat with red emerald tears streaming down her face.

and it flew right over their heads, the intensity this child could bring and what his uproar did. Elijah grew into the most rebellious vampire known all over the world, word got out that he is a wanted man for being the deadliest of the whole lineage. That's when the second and last coven was made, in the First Republic of France.

They call themselves the La Brumes, 10 vampires always gloating about their agility and power to vanish through thin air, facing no consequences whatsoever regarding their relation to the french revolution. Elijah made sure to be close to every nobility he could ever get to know including Louis XVI. It is heard around the streets of good ol France that Louis died at the hand of a creature that tore him apart and threw him all around his humble abode..in pieces might i add. And of course the servants and whoever found his pieces had to say that he was found dead in his bed.

He rebelled against his mother Selene and shunned her to a locked palace under an alias. putting her on trial simply for refusing his request to turn even more mortals into vampires around the world—talking all about the “tremendous power” it’ll give the covens. With the help of Kanchelsis, he ensured the highest and the mother of his kind doesn’t see the sun ever again. Stupid was he for he still yet has to face you.

𓃭

The candle lit room seemed to have seen better days, clothes and undergarments strewn all over the floor and around, where your naked form is laying on the lounge chair with nothing covering your lower intimate area but a light satin shawl.

Your observer for the day who is just as equally naked as you was your companion, or maybe lover? Not quite that..even though the both of you were really really close and she was one of the few people who managed to give you a bone thrashing orgasm. not to forget that the entanglements among the coven's members were a bit frowned upon by the higher ups—and all you replied with after making love to her was..fuck the higher ups, your coven or hers can suck it just how she does on a sunday morning.

“What ails your mind now? Do we need to go for a third round??” she questions, chuckling when you snort from your place with your arm under your head. “Now wouldn’t you love that Anderson?” you ask with a raised eyebrow.

You shrug “and let’s not get this twisted, I'm always the one that dominates you.”

she tuts with a sly smile etched on her cheeks “you read me like an open book mon cher” her brush cladded hand moving in calculated strokes against the canvas, focusing on painting your crimson glinting irises.

A smug look graces your face before you exclaim. “But we’re not lovers Abigail..remember?”

she shakes her head “And do you ever let me forget”

Abigail Anderson, the history you’ve had with her extends far back into your teenagehood, when her dad was your dad’s right hand. At first she saw you as a very smug, fragile, mommy dearest type of person, waltzing around in her mothers french garden with your Ted Lapidus glasses on and a red scarf that compliments your eyes around your neck, your figure cladded in a black on black suit. you’ve kept to yourself that day—until your younger brother decided it was a good day to throw you into the Anderson’s gigantic fish pool.

and oh boy was she ready to dunk in and save your poor self from the little fishies. holding your body close to hers where she was wearing a white simple shirt with nothing underneath and some grey trousers, her nipples hardening against the shirt and her eyes never leaving yours—the intensity of her stare definitely left you aching for something more.

she carries you out where your brother snickers and laughs at your sticky and wet form with a nod. shooting him a death glare, eyes shining in pure red, he closes his mouth not uttering a word when you pass him by the door with the water dripping down your back and forming a trail behind you.

“Good luck sister” he whispers.

that day she lent you her clothes—you never returned them. which was a little bit big on your frame. “Hopefully the stench will come out when you shower, there’s a towel behind the door for you, and plenty of hot water.”

“oh you’re not coming with?” you ask, feigning innocence.

she chuckles in amusement, fangs shining underneath her pink luscious lips. taking two steps towards you. “I don't think you’re ready for this” cold icy hand reaching to cradle your equally cold chin, she rubs it once before walking out of the door, leaving you to watch her wet shirt cladded back retort into the hallway.

“you know i really wanted you” you look up at her with glossy eyes and a downturned smile. prompting her hands movement on the canvas to pause, her back going rigid from her place in front of the aisle. shaking her head, inhaling hard “you know i would’ve never been able to hold you down”

you snorted in mockery “oh yeah i was the literal face of Studio 54 wasn’t i? Still I wouldn't have minded if you showed me around instead of gawking from the other side of the dance floor.” a manic laugh spurts out of you uncontrollably “i’ve searched for your face in every mortal i could find..man or woman, i wanted them big, hard, french with a mean streak..but they never were all of that. They were never that perfect, not like you at least.”

standing up, she rests the palette and the brush on the stool beside her. stretching out her back you can hear a few cracks bellow in defiance. walking up to you in slow calculated steps before kneeling down to your level, her big body creating a shadow that looked like it could engulf yours.

“and how can I make it up to you..hm?”

“Does anyone in your coven even know that you’re here? Your partner??” a look of disdain..confusion crossing your face when she holds out the palm of your hand to her lips, light feathery kiss after the other getting plastered all over your lightly held arm. Holding her dead stare you make no effort of moving or reciprocating her advances.

“Isn’t mommy dearest gonna get upset if she knows that i've been between these lush thighs for years?? Day in and night out you’ll have me right here, ravishing you and getting ravished by you and your heavenly sex” she points out looking up at you from her kneeling spot, a vision of art that she is, maybe you should’ve been the one who made her pose for you, you’ll probably end up hanging the portrait on the wall facing your bed..and maybe using it to relieve yourself while you whisper her name, knowing that she can hear you even with thousands of miles between the both of you.

“Bite me” a knowing look crosses her face, almost proud before she does exactly that without uttering any other words. Sinking her teeth into your forearm gulping down your sweet blood, abby’s loud throaty sounds and her humming into your skin sends pure vibrations urging your back to arch in immense pleasure. “Do you know the amount of people who’d love for me to tell them that? Bite me?” you push her teeth off with a low snarl. blood gushing and then trickling down your forearm, the veins around your eyes more prominent than ever.

Sparing her a scrutinizing look while you rise to your feet, the shawl sliding down your body and onto the floor beside her thigh. “And yet you’re the one asking your supposedly sworn enemy to do it” she retorts.

You can’t help but snicker at her whilst you put on your robe “says the one sitting knees down on my floor like a good kitten” words spitting out of your mouth like venom you failed to notice that in a fast whiff of air she appears in front of you, nails digging into your waist, the shine of her eyes speaking a foreign language to you, nose flaring uncontrollably with a lustful look gracing her face. She bites into your neck after a low growl, taking slow calculated strides until your back hits the wall of your room in a loud thud, swallowing your soft moan.

𓃭

“I need my sister gone”

“Here we fucking go again, i told you i am not that capable, i can’t kill your sister. Can’t you find a Cerbera Odollam stake or whatever your kind uses to kill each other and pierce it through her heart if the idea of her walking amongst the living haunts you still? It’s been two decades and you won’t let it rest.”

Not liking what she was hearing—the harsh and painful truth from her dear witch friend she mutters. “Your great grandmother did it once on my deranged uncle”

“You said it..deranged, your dear sister is eccentric..but not like him, he went on a killing rampage and it’s literally written down in history which was exactly what he dreamt of achieving and your coven gave it to him on a golden platter when your dad wrote a ‘fictional book’ about him”

Before getting executed by order of the two covens. Your uncle, David, claimed he saw god and that the almighty asked him to form a cult, your mother tried talking him out of it but it just resulted in him killing nearly ten vampires of which are his own including his own child and thousands of humans without hiding his tracks well. He wrote in blood on every concrete wall in the streets of every country he ever stepped foot on including Persia ‘if we burn you burn with us’.

A hunt had to be put in place for him, you were the one who brought him in, bruised and hungry. “I’m sorry uncle but you gave us no choice, who do you think you are? The prophet? What. a. Joke.” a baseball bat wrapped in silver wire swinging left and right in your hand, taking calculated steps towards him.

He was dragging himself on the wet muddy ground, clothes torn, hair matted with blood, reciting verses upon verses in prayer. A sight for sore eyes. not even bearing you a look, the poor man was trying to save himself. little did he know that in front of him was you. “have mercy on me, niece! the lord will save us all through my body”

you look around “i don’t see him saving you right now”

“b-but he is with us! i can see h-“ not taking your chances you swing the bat right at the side of his head, silver wires piercing his skull, hard enough to hurt but not enough to kill his immortal corpse. “Now you’ll get to meet the lord and have some tea together. tell him i said hello.”

𓃭

Ellie’s sleepless nights persisted after that dream she had, rehearsing, eating and writing for their new album had one being in mind…she thought it was very childish, but she couldn’t shake off the presence of it, of her, the vampire.

something she never believed in and never will—that’s what she keeps telling herself. in her young years she and her sister alongside their dad used to watch horror movies of which involved vampires and other monsters. Sarah would cling to their dad whilst Ellie would snicker at her older sister.

“you’re such a pussy”

“language Ellie” Joel would retort without a glance making her sister stick her tongue out from her place cuddled up against Joel. “tch it’s not even that scary..these types of things don’t even exist and if they did they’ll get killed in seconds in the sun” she shrugs.

Ellie continued with conveying her distaste about the paranormal, even when people started accusing them of selling their soul to the devil over their written lyrics and sudden spring into the metal and nu metal scene. interviewers found it funny and had to bring it up every. single. time. she was extremely fed up, she'd nod and and shrug cause why was it surprising that a so called satanist didn't believe in all of that??.

Dina on the other side leaned into it, often times than not taking weird pictures with a drawing of 'punk jesus' that she made, facing extreme backlash on her socials while Jesse posted verses about kindness—their PR team never catches a break that's for certain.

taglist🗞️: @winkybun

© 2024 acidblum, All Rights Reserved.

#☆-acidblum#❝ † Яitual † ❞#writings done by yours truly🙂↕️#rockstar!ellie#vampire!abby#ellie williams tlou#ellie tlou#ellie williams x reader#ellie williams#ellie the last of us#tlou ellie#the last of us 2#tlou part 2#tlou au#tlou2#tlou#tlou fanfiction#the last of us smut#ellie williams fluff#ellie williams smut#ellie williams x female reader#ellie smut#abby the last of us#abby x reader#abby tlou#dina tlou#abby anderson#abby anderson x reader#the last of us part 2#abby anderson fic

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

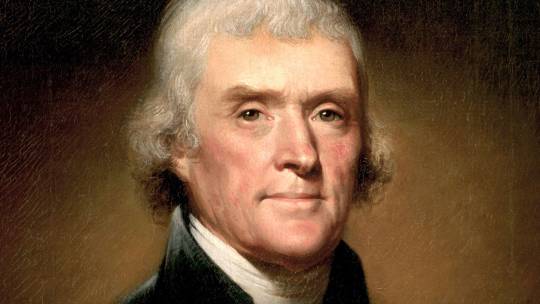

Saint-Just Hyping up Robespierre's Speech

Saint-Just, ordinarily rather reserved at the Jacobin Club, made an exception on January 1, 1793. Despite presiding over the session, he didn't share personal views or push his own agenda. Instead, he invited his colleagues to fund the printing and nationwide distribution of Robespierre's second speech on Louis XVI's trial (delivered on December 28, 1792)

His address was probably delivered in a a rather matter-of-fact and perfunctory tone. That being said, in my head, he's going full movie villain on the jacobins, urging them to open their purses or face the "dire consequences from the Archangel of Terror! Mwahahaha!”

(Translation under the cut)

Translation:

Citizens, you are well aware that, to dispel the errors with which Roland has enveloped the entire Republic, the Society has resolved to print and distribute Robespierre's speech. We have regarded it as an eternal lesson for the French people (1), as a sure way to unmask the Brissotin faction and to open the eyes of the French to the virtues of the minority seated on the Mountain that have been too long unknown. I remind you that a subscription office is open at the secretariat. It is enough for me to indicate this to stimulate your patriotic zeal, and, by emulating the patriots who have each contributed fifty ecus (2) to print Robespierre's excellent speech, you will have well earned the gratitude of the nation.

Notes

(1) The gushing is adorable

(2) In today's terms, fifty ecus translates to approximately 1900 euros. This was no small amount, particularly in light of the country's economic climate at the time.

Source:

Saint-Just, Louis Antoine Léon de. Œuvres. Paris: Gallimard, 2014

160 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Battle of Wattignies

The Battle of Wattignies was a significant battle in the War of the First Coalition, part of the wider French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802). It was fought on 15-16 October 1793 between a ragtag army of the First French Republic and a professional army of the Coalition. A French victory, the battle hindered the Coalition's encroachment onto French soil.

The battle was the capstone in a trilogy of French victories during the Flanders Campaign of 1792-1795, in which the French defeated the Coalition armies piecemeal; they defeated the British on 6-8 September at the Battle of Hondschoote and then beat the Dutch at the Battle of Menin on 13 September. Wattignies, fought against a mostly Austrian force, solidified the victories gained in the previous battles, weakening Coalition presence in Flanders and ensuring the survival of the French Revolution (1789-1799) for another year.

Background

The First Coalition was an alliance of Europe's great powers, united against the French Revolution. Unnerved by the trial and execution of Louis XVI and by the revolutionaries' promise to spread their revolution into the corners of Europe, the rulers of Europe's Ancien Régimes had assembled a multinational army to kill the infant French Republic in its cradle. Commanded by the Austrian nobleman Prince Josias of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, this army numbered over 100,000 men at its peak, comprised of soldiers from Austria, Prussia, Great Britain, Hanover, Hessen-Cassel, and the Dutch Republic. Sweeping the French out of Belgium in March 1793, this massive army laid siege to the French fortifications near the French-Belgian border, taking Condé-sur-l'Escaut and Valenciennes in July. With the French Army of the North still in disarray after a second defeat at the Battle of Raismes, it seemed to most observers that the Coalition was within arm's reach of victory.

Yet in August 1793, the mighty allied host split in two. After Valenciennes fell to the Coalition, the British contingents received orders from the government of Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger, instructing them to capture the port city of Dunkirk with all haste. Over protests from Coburg himself, Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany, commander of the British army, dutifully peeled his 35,000 men off from the main army and marched westwards to Dunkirk. Coburg, determined to finish capturing the French border fortifications, turned his 45,000 Austrians in the opposite direction, laying siege to Le Quesnoy, while detachments of Dutch soldiers maintained a thin line of communication between the British and Austrian armies. Many military historians consider this move to be a massive blunder that might have cost the Coalition victory.

Meanwhile, France was busy reorganizing itself. While the Coalition was preoccupied with the border fortifications, the Committee of Public Safety, France's de facto executive government, prioritized the defense of the Republic. Implementing the Reign of Terror to uncover counter-revolutionary enemies and foreign spies, the Committee purged the armies of officers suspected of disloyalty. Scores of generals and officers were carted off to Paris where they were arrested, tried, and in some cases, executed. Meanwhile, the Committee applied a policy of mass conscription, the levée en masse, which allowed France to field 14 armies and 800,000 soldiers by year's end. By September, these policies had the effect of swelling France's armies with undisciplined, untrained conscripts commanded by officers reluctant to act against the orders of the representatives-on-mission, lest they find themselves without heads. The effectiveness of these reforms was yet to be seen.

Continue reading...

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m super into film history and was curious the sort of films/scenes the French Revolution has inspired. Here’s some of the most unhinged………

Carry on don’t lose your head (1967) -During the French Revolution English nobles, Sir Rodney and Lord Darcy aid French aristocracy against Robespierre. Disguised as “Black Fingernail” , Sir Rodney battles Camembert (ooh nice cheese that) and Bidet (HA!) , French secret police leaders

Marat/Sade (1967) -In an insane asylum, Marquis de Sade directs Jean-Paul Marat’s last days through a theatre play. The actors are the patients. (Sade was a real person who wrote about BDSM a lot there’s more than one movie about him 😭)

Mr Peabody and Sherman (2014) - self explanatory-

Castlevania: Nocturne (2023-) - During the French Revolution, vampire hunter prodigy Richter Belmont fights to uphold his family’s legacy and prevent the rise of a ruthless, power hungry vampire

Every Scarlet Pimpernel film - Britt’s with a saviour complex what’s new

The multiple Adam and Eve see the future movies

La Révolution (2020) - In a reimagined history of the French Revolution, the guillotine’s future inventor uncovers a disease that drives the aristocracy to murder commoners (this actually seems to be a well liked series surprisingly)

Danton (1983) - had to add this movie, dick riding Danton this much is wild.

Reign of Terror (1949) - Robespierre, a powerful figure in the French Revolution, is desperately looking for his black book, a death list of those marked for the guillotine ( Death Note French Revolution AU ig)

Assassins Creed: Unity (2014) - Paris, 1789. You play as Arno Victor-Dorian, an assassin during the French Revolution. As the nation tears itself apart. Arno will expose the true powers behind the revolution

Start the revolution without me (1970) - Two mismatched sets of identical twins, one aristocrat, one peasant, mistakenly exchange identities on the eve of the French Revolution

A tale of two cities (multiple movies inspired by the Charles Dickens book) - Alcoholic lawyer, Sydney Carlton travels to Paris during the reign of terror to rescues French aristocrat, Charles Darnay, husband of the woman he loves (imagine being that down bad)

Danton (1931) - (what do ppl see in him that I don’t-) At the height of the French Revolution, the fanatic Robespierre brings the popular but more moderate leader, Danton , to trial and demands his execution (me when I lie)

The King without a crown (1937) - Explored the possibility that Louis XVII, son of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, escaped death during the French Revolution and was raised by *native Americans* (historical rpf has never been worse!)

Blackadder (1787) - Blackadder seeks to prove he’s just as capable of rescuing people from France as the Scarlet Pimpernel (this series is so fucking funny)

All the Doctor Who episodes that relate to the French Revolution!

An episode of the Friday the 13th series that has a painting act as a portal back to the “time of Marquis de Sade” (I needa research this man he’s mentioned more than Robespierre)

#frev shitposting#frev#french revolution#maximillian robespierre#maximilien robespierre#robespierre#georges danton

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is consistently entertaining to see how people, 200+ years later, will still blame Marie Antoinette for Louis XVI's actions. Same song and dance as her trial, just people who take it as a serious historical assessment of the situation.

You see, it's not that Louis XVI did those things of his own free will.... it's not that Louis XVI believed those were the best actions to take... Marie Antoinette advised it, therefore, she forced him to do it, because she was the one who held total control over his mind and body, apparently, and anything she said, he did.

(Never mind the things we know she disagreed with, such as Louis' plan for the flight to Montmedy. Marie Antoinette originally wanted the family to go in smaller, separate carriages for speed and safety--it was Louis who vetoed this.)

"I shall go down in history as the man who opened a door!" indeed.

#She said it best herself#“There is a vast difference between advising an action and executing it.”#Nevermind the fact that again--we know Louis went against her in plenty of cases#Louis leaning on her in 1789 as an intimate companion because he trusted her#is different than this notion that Louis was this helpless wee baby who did whatever she said

75 notes

·

View notes

Note

React to the bicentenary movie pls (in that movie u have some sexual tension with Saint-Just, you guys looked like you were going to fuck at any take )

I watched this film while keeping in mind how a difficult exercise it was to retranscribe six years of events in six short hours, when so much has happened. Overall, the Paris I knew at the time and the few exterior scenes that take place there (the women's bread queues, the infamous misery that rubbed shoulders with the Palais-Royal district, the long and sometimes disappointing sessions of the États Généraux) are quite faithfully depicted.

I was filled with a sweet nostalgia for the first dozen minutes. They gave a fairly accurate account of our disappointments, hopes, illusions and projects on the early times of the Revolution, even if the idea of being a “main character” makes me very ill at ease. But there was already a certain... strange aftertaste. Firstly, presenting Marat as some kind of bloodthirsty madman against the Girondins' moderation, presented as wise and reasonable, felt very concerning to me. So did smearing my name calling me a dictator, but I have grown a weary habit of such unfounded accusations.

There are so many things that didn't sit right with me, I've probably forgotten some.

- The Comité de Salut Public is presented as a ridiculous bunch of cowards terrified of me (I can assure you that in real life, they are not afraid to stand up to anyone and certainly not to me, nor to voice their opposition), where Couthon, Saint-Just and I are unofficially the only ones making decisions. Let me remind you that there are twelve of us, and everyone has a say, otherwise what would even be the point to meet up so regularely all together.

- The three days leading up to my death were reduced to the point that the conspiracy against me was erased from the scenario. Where was Tallien? Where was Fouché? Why were the heinous acts committed by the representatives on mission deliberately elided when it was such an important detail?

- The fête de l'Être Suprême is showed as a grotesque masquerade, a festivity disguised in my honor. Saint-Just was not even present, as the film claims; he was alongside our soldiers of the Armée du Nord.

And Saint-Just is undoubtedly the most unjustly mistreated character. His speech at the trial of Louis XVI which was so important has been completely emptied of its substance, his contributions to the public debate and his sincere devotion to the Republic have been swept aside to turn him into some kind of cruel little servant at my beck and call. The slander aimed at my own person has no effect on me anymore, but seeing him insulted in such a lowly manner has made my blood boil with anger.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint Just's speech of November 13 analyzed in a few words by the famous lawyer Jacques Vergès

Jacques Vergès ( 1925-2013)

In a YouTube video, the famous lawyer Jacques Vergès is interviewed on an Algerian TV show. Vergès is well-known in Algeria because he was the lawyer for many members of the FLN (National Liberation Front) and, above all, fervently supported the cause of the Algerian revolutionaries. He not only defended them but also married one of the most famous Algerian revolutionaries, Djamila Bouhired. At the time, defending FLN members during the Algerian War was a huge risk. Lawyers could be assassinated by extremists, like Pierre Popie, who was killed by the OAS (Secret Army Organization), or Maître Ould Aoudia, who was allegedly assassinated by the French secret services, as claimed by Raymond Muelle (this is also mentioned in the video, among other things).

Where it becomes especially interesting for those of us passionate about the French Revolution (or experts, considering some Tumblr users ^^) is when, at one point in the video, Jacques Vergès is shown two images: one of Saint-Just and another of Louis XVI (specifically at 1:28:12). Vergès explains that Saint-Just’s speech to the Convention on November 13, 1792, is, in his view, an "indictment of rupture" (this holds significant meaning for Vergès, who excelled in defenses of rupture, having achieved the remarkable feat of never having a client executed, particularly in the highly rigged trials of colonial justice during the Algerian Revolution). This is rare, as prosecutors (or at least those leading the accusation at the time) typically invoked the law. Vergès then elaborates (I’ll quote him directly from here on): "In the king's trial, some argue that it was impossible to try Louis XVI because the monarch had immunity tied to his functions, while others argue that the moment Louis XVI betrayed that immunity, it no longer applied."

Vergès concludes by referencing Saint-Just’s speech: "One day, people will be astonished that in the 18th century, we were less advanced than in Caesar's time—there, the tyrant was slain in the Senate itself, with no other formality than twenty-three dagger blows, and no other law than Rome's freedom."

The video continues a bit further on the topic of Saint-Just. Vergès finishes by saying that Saint-Just serves as a fantastic example for youth, ending with the revolutionary’s quote: "I despise this dust that makes me up and that speaks to you; they may persecute it and kill this dust! But I defy anyone to take from me this independent life I have created for myself in the ages and in the heavens."

What truly intrigued me was the legal perspective of Vergès, a specialist in defenses of rupture, on Saint-Just’s speech—particularly the concept of the "indictment of rupture."

Here is the link to the video (but it is in French and there are no subtitles) as a reminder the part that interests us, that is to say the evocation of Saint-Just, is at 1:28:12

Here is the link to the video (but it's in French and there are no subtitles). Just as a reminder, the part that interests us—the mention of Saint-Just—is at 1:28:12: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pZsK9975YoA&ab_channel=allkhadra.

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

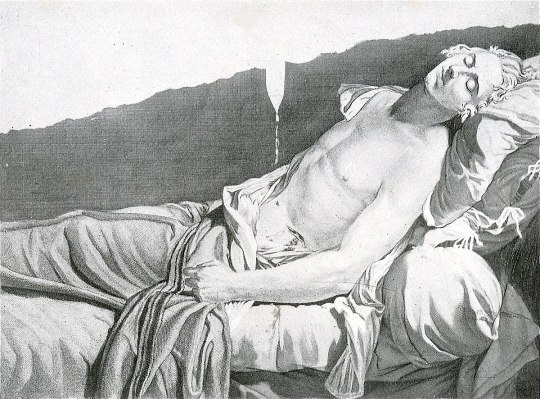

I understand the story of marat and his assassination event

But who is lepeletier?

Because I saw a drawing for him by louis David and I learned about his death which happen to be the same as Marat so yeah .. I wanna know about him.

According to the biography Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, 1760-1793 (1913), its subject of study was born on 29 May 1760, in his family home on rue Culture-Sainte-Catherine, a building which today is the Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris. His family belonged to the distinguished part of the robe nobility. At the death of his father in 1769, Lepeletier was both Count of Saint-Fargeau, Marquis of Montjeu, Baron of Peneuze, Grand Bailiff of Gien as well as the owner of 400,000 livres de rente. For five years he worked as avocat du roi at Châtelet, before becoming councilor in Parliament in 1783, general counsel in 1784 and finally taking over the prestigious position of président à mortier at the Parlement of Paris from his father in 1785. On May 16 1789, Lepeletier was elected to represent the nobility at the Estates General. On June 25 the same year he was one of the 47 nobles to join the newly declared National Assembly, two days before the king called on the rest of the first two estates to do so as well. A month later, during the night of August 4 1789, he was in the forefront of those who proposed the suppression of feudalism, even if, for his part, this meant losing 80 000 livres de rente. Four days later he wrote a letter to the priest of Saint-Fargeau, renouncing his rights to both mills, furnaces, dovecote, exclusive hunting and fishing, insence and holy water, butchery and haulage (the last four things the Assembly hadn’t ruled on yet). When the Assembly on June 19 1790 abolished titles, orders, and other privileges of the hereditary nobility, Lepeletier made the motion that all citizens could only bear their real family name — ”The tree of aristocracy still has a branch that you forgot to cut..., I want to talk about these usurper names, this right that the nobles have arrogated to themselves exclusively to call themselves by the name of the place where they were lords. I propose that every individual must bear his last name and consequently I sign my motion: Michel Lepeletier” — and the same year he also, in the name of the Criminal Jurisprudence Committee, presented a report on the supression of the penal code and argued for the abolition of the death penalty. After the closing of the National Assembly in 1791, Lepeletier settled in Auxerre to take on the functions of president of the directory of Yonne, a position to which he had been nominated the previous year. He did however soon thereafter return to Paris, as he, following the overthrow of the monarchy, was one of few former nobles elected to the National Convention, where he was also one of even fewer former nobles to sit together with the Mountain. In December 1792 he started working on a public education plan. On January 17, Lepeletier voted for death in the ongoing trial of Louis XVI (saying only ”I vote for death” without giving any further motivation) Three days later, the former king was sentenced to said penalty. That night, Lepeletier went over to Palais-Égalité (former Palais-Royal) where he dined everyday. The next day, his friend and fellow deputy Nicolas Maure could report the following to the Convention:

Citizens, it is with the deepest affection and resentment of my heart that I announce to you the assassination of a representative of the people, of my dear colleague and friend Lepelletier, deputy of Yonne; committed by an infamous royalist, yesterday, at five o'clock, at the restaurateur Fevrier, in the Jardin de l'Égalité. This good citizen was accustomed to dining there (and often, after our work, we enjoyed a gentle and friendly conversation there) by a very unfortunate fate, I did not find myself there; for perhaps I could have saved his life, or shared his fate. Barely had he started his dinner when six individuals, coming out of a neighboring room, presented themselves to him. One of them, said to be Pâris, a former bodyguard, said to the others: There's that rascal Lepeletier. He answered him, with his usual gentleness: I am Lepeletier, but I am not a rascal. Paris replied: Scoundrel, did you not vote for the death of the king? Lepelletier replied: That is true, because my confidence commanded me to do so.Instantly, the assassin pulled a saber, called a lighter, from under his coat and plunged it furiously into his left side, his lower abdomen; it created a wound four inches deep and four fingers wide. The assassin escaped with the help of his accomplices. Lepeletier still had the gentleness to forgive him, to pray that no further action would be taken; his strength allowed him to make his declaration to the public officer, and to sign it. He was placed in the hands of the surgeons who took him to his brother, at Place Vendôme. I went there immediately, led by my tender friendship, and my reverence for the virtues which he practiced without ostentation: I found him on his death bed, unconscious. When he showed me his wound, he uttered only these two words: I'm cold. He died this morning, at half past one, saying that he was happy to shed his blood for the homeland; that he hoped that the sacrifice of his life would consolidate Liberty; that he died satisfied with having fulfilled his oaths.

This was the first time a Convention deputy had gotten murdered, and it naturally caused strong reactions. Already the same session when Maure had announced Lepeletier’s death, the Convention ordered the following:

There are grounds for indictment against Pâris, former king's guard, accused of the assassination of the person of Michel Lepelletier, one of the representatives of the French people, committed yesterday.

[The Convention] instructs the Provisional Executive Council to prosecute and punish the culprit and his accomplices by the most prompt measures, and to without delay hand over to its committee of decrees the copies of the minutes from the justice of the peace and the other acts containing information relating to this attack.

The Decrees and Legislation Committees will present, in tomorrow's session, the drafting of the indictment.

An address will be written to the French people, which will be sent to the 84 departments and the armies, by extraordinary couriers, to inform them of the crime against the Nation which has just been committed against the person of Michel Lepelletier, of the measures that the National Convention has taken for the punishment for this attack, to invite the citizens to peace and tranquility, and the constituted authorities to the most exact surveillance.

The entire National Convention will attend the funeral of Michel Lepelletier, assassinated for having voted for the death of the tyrant.

The honors of the French Pantheon are awarded to Michel Lepelletier, and his body will be placed there.

The president is responsible for writing, on behalf of the National Convention, to the department of Yonne, and to the family of Lepelletier.

The next day, January 22, further instructions were given regarding Lepeletier’s funeral:

On Thursday January 24, Year 2 of the Republic, at eight o'clock in the morning, will be celebrated, at the expense of the Nation, the funeral of Michel Lepeletier, deputy of the department of Yonne to the National Convention.

The National Convention will attend the funeral of Michel Lepeletier in its entirety. The executive council, the administrative and judicial bodies will attend it as well.

The executive council and the department of Paris will consult with the Committee of Public Instruction regarding the details of the funeral ceremony.

The last words spoken by Michel Lepeletier will be engraved on his tomb, they are as follows: “I am happy to shed my blood for the homeland; I hope that it will serve to consolidate Liberty and Equality; and to make their enemies recognized.”

In number 27 (January 27 1793) of Gazette Nationale ou Le Moniteur Universel, the following long description was given over Lepeletier’s funeral, held three days earlier:

The funeral of Lepeletier Saint-Fargeau was celebrated on Thursday 24 with all the splendor that the severity of the weather and the season allowed, but with such a crowd that it could have been the most beautiful day of the year. At ten o'clock in the morning his deathbed was placed on the pedestal where the equestrian statue of Louis XVI previously stood, on Place Vendôme, today Place des Piques. One went up to the pedestal by two staircases, on the banisters of which were antique candelabras. The body was lying on the bed with the bloody sheets and the sword with which he had been struck. He was naked to the waist, and his large and deep wound could be seen exposed. These were the mournful and most endearing part of this great spectacle. All that was missing was the author of the crime, chained, and beginning his torture by witnessing the sight of the triumph of Saint-Fargeau. As soon as the National Convention and all the bodies that were to form courage were assembled in the square, mournful music was played. It was, like almost all those which has embellished our revolutionary festivals, the composition of citizen Gossec. The Convention was ranged around the pedestal. The citizen in charge of the ceremonies presented the President of the Convention with a wreath of oak and flowers; then the president, preceded by the ushers of the Convention and the national music, went around the monument, and went up to the pedestal to place the civic crown on Lepeletier's head: during this time, a federate gave a speech; the president dismounted, the procession set out in the following order: A detachment of cavalry preceded by trumpets with fourdincs. Sappers. Cannoneers without cannons. Detachment of veiled drummers. Declaration of the rights of man carried by citizens. Volunteers of the six legions, and 24 flags. Drum detachment. A banner on which was written the decree of the Convention which ordered the transport of Lepeletier's body to the Pantheon. Students of the homeland. Police commissioners. The conciliation office. Justices of the peace. Section presidents and commissioners. The commercial court. The provisional criminal court. The department’s fix courts. The electorate. The provisional criminal court. The department's criminal courts fix. The municipality of Paris. The districts of Saint-Denis and the village of L’Égalité. The Department. Drum detachment. The seal of the 84, worn by Federates. The provisional executive council. National Convention Guard Detachment. The court of cassation. Figure of Liberty carried by citizens. The bloody clothes worn at the end of a national pike, deputies marching in two columns. In the middle of the deputies was a banner where Lepeletier's last words were written: "I am happy to shed my blood for my homeland, I hope that it will serve to consolidate Liberty and Equality, and to make their enemies known.”

The body carried by citizens, as it was exhibited on the Place des Piques. Around the body, gunners, sabers in hand, accompanied by an equal number of Veterans. Music from the National Guard, who performed funeral tunes during the march. Family of the dead. Group of mothers with children. Detachment of the Convention Guard. Veiled drums. Volunteers of the six legions and 24 flags. Veiled drums. Volunteers of the six legions and 24 flags. Veiled drums. Volunteers of the six legions and 24 flags. Veiled drums. Armed federations. Popular societies. Cavalry and trumpets with fourdines. On each side, citizens, armed with pikes, formed a barrier and supported the columns. These citizens held their pikes horizontally, at hip height, from hand to hand. The procession left in this order from the Place des Piques, and passed through the streets St-Honoré, du Roule, the Pont-Neuf, the streets Thionville (former Dauphine), Fossés Saint-Germain, Liberté (former Fossés M. le Prince), Place Saint-Michel and Rue d'Enfer, Saint-Thomas, Saint-Jacques and Place du Panthéon. It stopped front of the meeting room of the Friends of Liberty and Equality; opposite the Oratory, on the Pont-Neuf, opposite the Samaritaine; in front of the meeting room of the Friends of the Rights of Man; at the intersection of Rue de la Liberté; Place Saint-Michel and the Pantheon. Arriving at the Pantheon, the body was placed on the platform prepared for it. The National Convention lined up around it; the band, placed in the rostrum, performed a superb religious choir; Lepeletier's brother then gave a speech, in which he announced that his brother had left a work, almost completed, on national education, which will soon be made public; he ended with these words: I vote, like my brother, for the death of tyrants. The representatives of the people, brought closer to the body, promised each other union, and swore on the salvation of the homeland. A big chorus to Liberty ended the ceremony.

According to Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, 1760-1793 (1913), civic festivals in honor of Lepeletier were celebrated in all sections of Paris, as well as the towns of Arras, Toulouse, Chaumont, Valenciennes, Dijon, Abbeville and Huningue. Lepeletier’s body did however only get to rest in the Panthéon for a little more than two years, as on February 15 1795, the Convention ordered it exhumed, at the same time as that of Marat. It was instead buried in the park surrounding Château de Ménilmontant, the properly of which the ancestor Lepeletier de Souzy had purchased in the 17th century and that still remained in the family.

One day after the funeral, January 25, Lepeletier’s only child, the ten and a half year old Susanne, who had already lost her mother ten years before the murder of her father, was brought before the Convention by her step-mother and two paternal uncles Amédée and Félix. It was Félix who had held a speech during the funeral and he would continue to work for his seven years older brother’s memory afterwards too, offering a bust of him to the Convention on February 21 1793, (on the proposal of David, it was placed next to the one of Brutus), reading his posthumous work on public education to the Jacobins on July 19 1793, and even writing a whole biography over his life in 1794 (Vie de Michel Lepeletier, représentant du peuple français, assassiné à Paris le 20 janvier 1793 : faite et présentée a la Société des Jacobins).

The president announces that the widow of Michel Lepelletier, his two brothers and his daughter, request to be admitted to the bar, to testify to the Convention their recognition of the honors that they have decreed in memory of their relative. It is decreed that they will be admitted immediately.

One of Michel Lepeletier’s brothers: Citizens, allow me to introduce my niece, the daughter of Michel Lepelletier; she comes to offer you and the French people her recognition of the eternity of glory to which you have dedicated her father... He takes the young citoyenne Lepelletier in his arms, and makes her look at the president of the Convention... My niece, this is now your father... Then, addressing the members of the Convention, and the citizens present at the session: People, here is your child... Lepelletier pronounces these last words in an altered voice: silence reigns throughout the room, with exception for a couple of sobs.

The President: Citizens, the martyr of Liberty has received the just tribute of tears owed to him by the National Convention, and the just honor that his cold skin has received invites us to imitate his example and to avenge his death. But the name of Lepelletier, immortal from now on, will be dear to the French Nation. The National Convention, which needs to be consoled, finds relief to its pain in expressing to his family the just regrets of its members and the recognition of the great Nation of which it is the organ. The Nation will undoubtedly ratify the adoption of Michel Lepelletier's daughter that is currently being carried out by the National Convention.

Barère: The emotion that the sight of Michel Lepeletier's only daughter has just communicated to your souls must not be infertile for the homeland. Susanne Lepelletier lost her father; she must find now find one in the French people. Its representatives must consecrate this moment of all-too-just felicity to a law that can bring happiness to several citizens and hope to several families. The errors of nature, the illusions of paternity, the stability of morals, have long demanded this beautiful institution of the Romans. What more touching time could present itself at the National Convention to pass into French legislation the principle of adoption, than that when the last crimes of expiring tyranny deprived the homeland of one of its ardent defenders and Susanne Lepelletier of a dear father! Let the National Convention therefore give today the first example of adoption by decreeing it for the only offspring of Lepelletier; let it instruct the Legislation Committee to immediately present the bill on this interesting subject. I ask that the homeland adopt through your organ Susanne Lepelletier, daughter of Michel Lepelletier, who died for his country; that it decrees that adoption will be part of French legislation, and instructs its Legislation Committee to immediately present the draft decree on adoption.

This proposal is unanimously approved.

Susanne being adopted by the state would however lead to a fierce debate when, in 1797, this ”daughter of the nation” wished to marry a foreigner. For this affair, see the article Adopted Daughter of the French People: Suzanne Lepeletier and Her Father, the National Assembly (1999)

Right after Barère’s intervention, David took to the rostrum:

David: Still filled with the pain that we felt, while attending the funeral procession with which we honored the inanimate remains of our colleagues, I ask that a marble monument be made, which transmits to posterity the figure of Lepelletier , as you clearly saw, when it was brought to the Pantheon. I ask that this work be put into competition.

Saint-André: I ask that this figure be placed on the pedestal which is in the middle of Place Vendôme... (A few murmurs arise)

Jullien: I ask that the Convention adopt in advance, in the name of the homeland, the children of the defenders of Liberty, who, for similar reasons, could be immolated in the vengeance of the royalists.

All these proposals are referred to the Legislation and Public Instruction Committees.

On Maure's proposal, the Assembly orders the printing of the speeches delivered yesterday at the Panthéon, by one of Michel Lepelletier's brothers, Barère and Vergniaux.

If it would appear David never got to make a marble monument of Lepeletier, on March 28 1793, he could nevertheless present the following painting of his to the Convention, which isn’t just a little similar to his La Mort de Marat.

(This image is an engraving of the actual painting, which has gone missing)

After Marat on July 13 1793 (the very same day the plan for public education Lepeletier had been working on was presented to the Convention by Robespierre) became the second assassinated Convention deputy, we find several engravings etc, depicting the two ”martyrs of liberty” side by side.

In the following months, even more people would be join the two, such as Joseph Chalier, a lyonnais politician executed on July 17 1793 and Joseph Bara, a fourteen year old republican drummer boy killed in the Vendée by the pro-Monarchist forces.

Lepeletier’s murderer, 27 year old Philippe Nicolas Marie de Pâris, a man who the minister of justice described as "former king's guard, height five pieds, five pouces, barbe bleue, and black hair; swarthy complexion, fine teeth, dressed in a gray cloak, green lapels and a round hat” on January 21, went into hiding right after his deed. In spite of his description being published in the papers and a considerable sum of money being promised to whoever caught him, Pâris managed to flee Paris and settled for a country house of an acquaintance near Bourget. He there ran into a cousin of one of the owners. When Pâris asked for food and a bed, he was refused and instead disappeared into the night again. In the evening of January 28 he arrived in Forges-les-Eaux and stopped at an inn, where he came under suspicion once he started cutting his bread with a dagger after which he locked himself into his room. The following morning he woke up with a start as five municipal gendarmes came bursting into his room and told him to come with them. Pâris responded that he would, but in the next second he had picked up his hidden pistol, placed it into his mouth, and pulled the trigger. Searching the dead body, the gendarmes found Pâris’ baptism record (dated November 12 1765) and dismissal from the king's guard (dated June 1 1792), on the latter of which had been written the following:

My certificate of honor. Do not trouble anyone. No one was my accomplice in the fortunate death of the scoundrel de Saint-Fargeau. Had I not run into him, I would have carried out a more beautiful action: I would have purged France of the patricide, regicide and parricide d’Orléans. The French are cowards to whom I say: Peuple dont les forfaits jettent partout l'effroi, Avec calme et plaisir j'abandonne la vie. Ce n'est que par la mort qu'on peut fuir l'infamie Qu'imprime sur nos fronts le sang de notre roi. Signed by Paris the older, guard of the king, assassinated by the French.

Learning about what had happened, the Convention tasked Tallien and Legrand with going to Forges-les-Eaux and making sure the dead man really was Pânis. Having come to the conclusion that this was indeed the case, the deputies briefly discussed whether the body ought to be brought back to Paris, but it was decided it would be better if it was just buried "with ignominy.” It was therefore instead taken into the nearby forest in a wheelbarrow and thrown into a six feet deep hole.

Finally, here are some other revolutionaries simping for honoring Lepeletier’s memory just because I can:

…a tragic event took place the day before the execution [of the king]. Pelletier, one of the most patriotic deputies, and who had voted for death, was assassinated. A king's guard made a wound three fingers wide with a saber: he died this morning. You must judge the effect that such a crime has had on the friends of liberty. Pelletier had an income of six hundred thousand livres; he had been président à mortier in the Parliament of Paris; he was barely thirty years old; to many talents, he added the most estimable of virtues. He died happy, he took to his grave the idea, consoling for a patriot, that his death would serve the public good. Here then is one of these beings whom the infamous cabal who, in the Convention, wanted to save Louis and bring back slavery, designated to the departments as a Maratist, a factious, a disorganizer... But the reign of these political rascals is finished. You will see the measures that the Assembly took both to avenge the national majesty and to pay homage to a generous martyr of liberty. Philippe Lebas in a letter to his father, January 21 1793

Ah! if it is true that man does not die entirely and that the noblest part of himself survives beyond the grave and is still interested in the things of life, come then, dear and sacred shadow, sometimes to hover above the Senate of the nation that you adorned with your virtues; come and contemplate your work, come and see your united brothers contributing to the happiness of the homeland, to the happiness of humanity. Marat in number 105 (January 23 1793) of Journal de la République Française

O Lepeletier! Your death will serve the Republic: I envy your death. You ask for the honors of the Pantheon for him, but he has already collected the prize of martyrdom of Liberty. The way to honor his memory is to swear that we will not leave each other without having given a constitution to the Republic. Danton at the Convention, January 21 1793

O Le Peletier, you were worthy to die for your homeland under the blows of its assassins! Dear and sacred shadow, receive our wishes and our oaths! Generous citizen, incorruptible friend of the truth, we swear by your virtues, we swear by your fatal and glorious death to defend against you the holy cause of which you were the apostle; we swear eternal war against the crime of which you were the eternal enemy, against the tyranny and treason of which you were the victim. We envy your death and we will know how to imitate your life. They will remain forever engraved in our hearts, these last words where you showed us your entire soul; ”May my death,” you said, “be useful to the homeland, may it will serve to make known the true and false friends of liberty, and I die content.” Robespierre at the Jacobins, January 23

Wednesday 23 [sic] — We went to Madame Boyer’s to see the procession. I saw the poor Saint-Fargeau. We all burst into tears when the body passed by, we threw a wreath on it. After the ceremony, we returned to my house. Ricord and Forestier had arrived. I was unable to stop my tears for some time. F(réron), La P(oype), Po, R(obert) and others came to dinner. The dinner was quite fun and cheerful. Afterwards they went to the Jacobins, Maman and I stayed by the fire and, our imaginations struck by what we had seen, we talked about it for a while. She wanted to leave, I felt that I could not be alone and bear the horrible thoughts that were going to besiege me. I ran to D(anton’s). He was moved to see me still pale and defeated. We drank tea, I supped there. Lucile Desmoulins in her diary, January 24 1793

…Pelletier's funeral took place this Thursday as I informed you in my last letter (this letter has gone missing). The procession was immense; it seemed that the population of Paris had doubled, to honor the memory of this virtuous citizen. The mourning of the soul was painted on all the faces: it was especially noticed that the people were extremely affected, which proves that they keenly felt the price of the friend they had lost. Arriving at the Pantheon, Lepelletier's body was placed on the platform prepared for it; his brother delivered a speech which was applauded with tears; Barère succeeded him. Then the members of the Convention, crowding around the body of their colleague, promised union among themselves, and took an oath to save the country. God grant that we have not sworn in vain, that we finally know the full extent of our duties, and that we only occupy ourselves with fulfilling them! In yesterday's session, Pelletier's daughter, aged eight [sic], was presented to the National Convention, which immediately adopted her as a child of the homeland. Georges Couthon in a letter written January 26 1793

How could I be so base as to abandon myself to criminal connections, I who, in the world, have never had more than one close friend since the age of six? (he gestures towards David's painting). Here he is! Michel Lepeletier, oh you from whom I have never parted, you whose virtue was my model, you who like me was the target of parliamentary hatred, happy martyr! I envy your glory. I, like you, will rush for my country in the face of liberticidal daggers; but did I have to be assassinated by the dagger of a republican! Hérault de Sechelles at the Convention, December 29 1793

For a collection of Lepeletier’s works, see Oeuvres de Michel Lepeletier Saint-Fargeau, député aux assemblées constituante et conventionnelle, assassiné le 20 janvier 1793, par Paris, garde du roi (1826)

#hérault and lepeletier being bffs since age six was new information for me#also i think Augustin just found a rival in ”most loyal little bro in the revolution”#frev#michel lepeletier#lepeletier de saint-fargeau#french revolution#ask#long post

65 notes

·

View notes

Note

Most ridiculous thing Carnot has ever done?

Sorry for the late, dear Anon.

This took me a while to reply, since, during his life, Carnot had put himself in rather problematic situations, that led him to act in ways that can be considered embarrassing (1) by various people with different views. So it was hard for me to choose just one thing: a specific thing that he did, which might be seen as foolish and careless by someone, might not be viewed in the same way by another person.

I'm pretty sure that what I'm about to say has a chance to the considered ridiculous by many - if not all - here on Frevblr. I'm referring to the fact that he accepted the cross of Saint-Louis, becoming de facto a member - a knight to be more precise - of the homonymous order, just a few months before the trial of the king. I don't know for sure when exactly he received it, but it definitely happened in 1792, according to L'Histoire de l'ordre royal et militaire de Saint-Louis (p. 493-494).

The order of Saint-Louis was an ancient cavalry order founded in 1693 by Louis XIV, the "Sun King". Until the latter's death it was intended as a prestigious and profitable (2) reward for officers who had distinguished themselves through their feats, but in later years, it started to be treated as a decoration which officers eventually achieved. It's also important to point out that non-nobles could be admitted in the order and it was easier to join for engineering officers, like Carnot. Requirements were further lowered in a series of decrees by the Legislative Assembly and sanctioned by Louis XVI (3) and the order was eventually suppressed on 15 October 1792.

Personally, I find questionable the decision to receive such a reward, after the flight of Varennes, or worse after the 10 of August (again I don't know exactly when he was granted that). On one hand, I can understand the desire for prestige and the conspicuous pension he would have received, allowing him to retire in peace, as well as the fact that he grew up in a world, in which being a knight of Saint-Louis was seen as honorable and worthy of praise. On the other one, we are talking about something which was intrinsically part of an old oppressive system, that Carnot himself was contributing to reform; not to mention that the highest authority of that system and head of the order was found guilty of treason against his people at the time Carnot accepted the cross.

Notes

(1) I'm referring to things that revealed themselves to be embarrassing for him only, so nothing that caused harm to other people. Framing his responsibilities in the arrestation of the Babuovistes as ridiculous would be an euphemism if what I read from bits here and there is true.

(2) Members of the order of Saint-Louis were granted a special pension which added itself to that of the military rank at the time of retirement.

(3) For the decrees see A. Mazas, T. Anne, L'Histoire de l'ordre royal et militaire de Saint-Louis, Tome 2 (1860) (p. 502-504).

#lazare carnot#frev#french revolution#order of saint-louis#if you are wondering no it wasn't this thing that triggered me in my previous post. It was another thing that he and Prieur did#to which there's a plausible explanation but it was personally disappointing to read about that nonetheless :(

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Geneviève d’Eon & Marie-Jeanne Bertin: Clothing and Gender in 18th Century France

"After being fully dressed by famous designer Rose Bertin for the first time, they ran to their room and cried for hours." ~ Kaz Rowe, The Chevalier d'Eon: the Trans 18th Century Spy

Kaz Rowe throws this story out there in their video on d'Eon as a part of their justification in using they/them pronouns for d'Eon who used she/her pronouns. Rowe never really explains the context for this story. It sounds dramatic on the surface, d'Eon spent hours crying over being forced into women's clothes. But did this really happen?

This story comes from d'Eon's own autobiographical writings that she never finished. Segments of her drafts were translated and published by Roland A. Champagne, Nina Ekstein, and Gary Kates in The Maiden of Tonnerre. The title comes from d'Eon who styled herself la pucelle de Tonnerre after Joan of Arc who was known as la pucelle d'Orléans.

Some things to consider before we start:

D'Eon's autobiographical writings operate under the pretence that she was afab and raised as a boy for inherence reasons. We have to remember that these writings are heavily fictionalised, a necessity in upholding the lie that allowed d'Eon to live as a woman. However that doesn't mean that there is no historical value in these writings. Instead of simply taking these stories as fact we must consider: Why is d'Eon presenting this story in this way? How does this story serve the narrative d'Eon is constructing for herself?

D'Eon in this story claims she had never worn women's clothing before. This is contradicted by d'Eon's own claim of infiltrating the court of Empress Elizabeth of Russia as a woman. While its hard to pinpoint the exact moment d'Eon first wore women's clothes I personally suspect it was much earlier than this.

D'Eon also includes a scene where she is bathed by Bertin's assistants. This scene is almost certainly fictional as if it happened in reality this would reveal that d'Eon had a penis, a fact she wanted to keep secret. This scene is almost certainly included to add to the 'evidence' that d'Eon was afab.

Considering these points we must consider that this story did not take place literally as d'Eon depicts it. Instead of taking this story as an accurate recollection of events I consider it a fictionalised story (based on true events). The goal in my analysis is to ask what is d'Eon trying to communicate though this story.

Some background information to add context:

D'Eon had prior to this incident signed a transaction with Louis XVI in which she was legally acknowledged as a woman and ordered by Louis XVI to wear woman's clothes. D'Eon agreed to "declaring publicly my sex, to my condition being established beyond a doubt, to resume and wear female attire until death," but then adds "unless, taking into consideration my being so long accustomed to appear in uniform, his Majesty will consent, on sufferance only, to my resuming male attire should it become impossible for me to endure the embarrassment of adopting the other". (see D'Eon de Beaumont, his life and times by Alfred Rieu, p174-182 for an English translation of the transaction)

We also must consider that d'Eon did not dispute the fact that she was a woman when signing the transaction, nor does she dispute this in her autobiographical writings. D'Eon was very much arguing that she, as a woman, should be allowed to continue to wear men's clothing (specifically her dragoon uniform) as that is what she was used to wearing and comfortable wearing.

Also mentioned in the following excerpt is the English trial over d'Eon's sex in which it was found that d'Eon was a woman. I'm not going to get too into the topic here as it's a whole other can of worms. However I think it's important to understand that while d'Eon had issues with aspects of the trial she would use the ruling to support her claim that she was afab.

The Maiden of Tonnerre: Chapter VII

Selections from the great interview between Mademoiselle Bertin and Mademoiselle d'Eon in Paris on October 21, 1777 Mademoiselle Bertin. I have come vary early in the morning to spare you trouble and embarrassment. But what else can I do? You must either go through this or through the gates of a convent. Mademoiselle d'Eon. It is easy to do otherwise. Just leave me as I am. I have lived for forty-eight years this way. I cannot live all that much longer. I am impatiently awaiting the great change that will transform us all making all of us eternally equal. Mademoiselle Bertin. The Court in its patience will never have the endurance to wait that long. Remember that it was a deliberate error on the part of your father, your mother, and yourself that resulted in Mademoiselle d'Eon's wearing men's clothing and a military uniform. But since that time things have changed considerably, and today by order of King and the law, the bad boy must become a good girl.

It's interesting that here d'Eon has Bertin distinguish between "men's clothing" and "military uniform". As women were not allowed in the French military at this time all French military uniforms were as such men's clothing. But d'Eon did not simply want to wear men's clothing she wanted to wear her military uniform.

Mademoiselle d'Eon. If I was a boy by mistake, one could inadvertently allow me to continue to be one. While you are correct about the substance of the matter, I am not wrong about the form. Mademoiselle Bertin. That is not possible now. Your trial created too much of a stir. Mademoiselle d'Eon. I am a reliable bugler in my squadron. I am not frightened by noise. The Court's behaviour, by its very decency, has wound up being indecent. I would have thought that the King would have been willing to allow me to wear the uniform of a former dragoon captain, Knight of Saint Louis, and plenipotentiary minister, since he was kind enough to allow me to wear the cross of the royal and military order of Saint Louis on my dress. Do you see how everything at court is so arbitrary? There one could say every day: Contraria contrariis opponuntur [A contrary opposes other contraries].

Again we see the focus is that d'Eon wanted to wear her dragoon uniform. She likens this directly to her cross of Saint Louis which Louis XVI did permit her to wear on her women's clothes. As the cross of Saint Louis was only awarded to men it is arguably also menswear. D'Eon is pointing out the arbitrary nature of this distinction. Why is she permitted to wear an idem of menswear, the cross of Saint Louis, but not another, her dragoon uniform. To d'Eon these both represent her achievements rather than manhood, she is arguing that she, a woman, should be allowed to wear them.

Mademoiselle Bertin. I concede that every day we see in the streets of Paris a tall young woman in the uniform of a dragoon publicly giving lessons on the use if arms. But remember that this girl was a mere dragoon and that she had no other way to earn a living. To do so, she had written permission to dress as a dragoon form the lieutenant general of the Paris police. But the Court would never grant such permission for a young woman from a good family who had been in France and in foreign courts as Mademoiselle d'Eon has been. Mademoiselle d'Eon. In a well-regulated country, the law must not allow preferential treatment to anyone. Mademoiselle Bertin. You can go to Versailles to argue with the Chancellor of France, your former schoolmate. But with Mademoiselle Bertin, it can serve no purpose to argue. Do not take this matter so far as to have a falling out with the King's ministers or the royal Treasury. Remember, Mademoiselle, that in France a maiden who obeys the law and the King must wear her dress and petticoat, whether to remain in this world or to spend her time in the convent. Mademoiselle d'Eon. Your advice is wise and prudent. I would rather follow you into the royal Treasury than into a convent. Mademoiselle Bertin. My honorable captain, don't think that you are dishonored by having been found to be a woman. The discomfiture is temporary, and the glory will be with you forever. But let us not wast uselessly the precious time needed to begin and end your outfitting before the return of Major Varville. Mademoiselle d'Eon. I see that Mademoiselle Bertin is correct about all that she says and does and that a lady-in-waiting to the Queen is thus wiser in her comportment and in her begetting than all the children of the Enlightenment and all the captains of the army. Without delaying further and having followed the instructions of Mademoiselle Bertin, the Dragoon was, in a short period of time, divested of his serpent's skin and transformed into an angel of light. Her head became as lustrous as the sun. Her whole outlook on things changed as much as did her face. No trace of the dragoon remained in her. Mademoiselle Bertin thought she was consoling me by saying: "The Queen doesn't despise bravery in a well-born maiden. But out of duty she prefers to find in her decency, honor, and virtue. If Louis XV armed you as a Knight of French soldiers, Louis XVI arms you as a chevalière of French women. And the Queen crowns your wisdom by commanding me to bring to you this new armor, which must accompany your coiffure and your demeanor so that you may become the leading general of all the honorable women of France. The time has come for us to be edified and not scandalized by Mademoiselle d'Eon's conduct. Why don't you offer up your uniform as a sacrifice at Notre Dame de Paris or in your holy anger throw it out the window in order to stand witness before the people of Israel, the Parisians, the Scribes, and the Pharisees that you are now following the letter of the law that Moses gave us in his commandments." While Mademoiselle Bertin had me get into the bath to be washed, soaped and scrubbed down by her companions, I told her: "Proceed as quickly as possible; do not waste time with the preparations so that I too may keep part of my own dignity as it is joined with yours and that of your seamstresses. Virtuous Bertin, honest messenger form the chamber of the Queen, I fully realize that the hour is at hand for me to follow the directive of the law and the King. As a victim, I am offered up in sacrifice since you do me harm in order to do me good. All women are going to point at me, and all the maidens are going to thumb their noses at me when they see me dressed in style and done up like a doll or at the very least like a Vestal Virgin who is led to the marriage altar."

We see in this excerpt Bertin acts as an authority ushering d'Eon into womanhood, the transformation is painful but ultimately positive for d'Eon; "you do me harm in order to do me good". But there is this real fear of being mocked by other women. At least part of d'Eon's trepidation to don women's clothes comes form the fear of humiliation. We see this fear also reflected in the transaction when she begs King Louis to "consent, on sufferance only, to my resuming male attire should it become impossible for me to endure the embarrassment of adopting the other".

Mademoiselle Bertin. Put aside your concerns about what other will say. Must what the mad say prevent us from being wise? Mademoiselle d'Eon. Alas, at court everything is beautiful. To please the court, does a former captain have to become a pretty boy [demoiseau]? Mademoiselle Bertin. Yes, absolutely, when the so-called "boy" is discovered to be in fact a girl by the systems of justice both in England and in France. Mademoiselle d'Eon. Speaking of justice, is Mademoiselle Bertin, the Queen's servant, also the enforcer of justice? Mademoiselle Bertin was stung. "Don't be angry," I told her, "I simply wanted you to acknowledge, for you are just in all matters, that I cannot fit into the dress you brought me." Mademoiselle Bertin remained disconcerted for a moment. But she soon regained her composure and said to me: "If you are a patient girl, the dress that I made for you in the name of Justice will soon be taken out to fit you. And I predict for you that the certainty of happiness will come form the alleged abyss of your unhappiness." Then, looking pleased with herself, she said to me: "I am glad about having stripped you of your armor and your dragoon skin in order to arm you from head to toe with your dress and finery. In you I have found the power to possess the benefit of simple tonsure without a papal dispensation. Give thanks to God. You can assuredly double your chances of attaining eternal life, for which all of us search amidst this life's sorrows, troubles and suffering. Tomorrow you will suffer less, and the following day you will not suffer at all. In a little while, you will enjoy the relaxation and the joy that are the natural prerogatives of a Catholic girl who loyally follows the breviary of Rome and Paris, which was annotated, revised, and made available to the Daughters of Holy Mary and the Queen's women. You are not yet canonized, but soon you will be beatified when your upcoming marriage is canonically approved. Better this for you than a cannon shot."

D'Eon at this time was considering joining a convent. Bertin is referring to d'Eon's marriage to Christ.

Mademoiselle d'Eon. You can even say that regarding a hail of cannon shots. ... But when I reflect on my past and present states, I will never have the courage to go out in public dressed as you have me. You have illuminated and brightened me up so much that I dare not look at myself in the mirror that you brought me. Mademoiselle Bertin. A room is not lit up in order to hide it or to keep it in the dark, but rather it is placed beneath a chandelier so that those who enter can see the light and be edified by your conversion. Mademoiselle d'Eon. I know that there is nothing hidden that should not be revealed or anything secret that cannot be known. Therefore, I will not seek my own willpower but that of the King who sent you here to Mademoiselle d'Eon to change what is bad into something good. Since he obliges me to choose the best way, it will not be taken away from me. What is worth choosing is worth maintaining. When you came to me, I thought you were bringing me death. Now I go to you in order to be alive, because I am no longer chasing after the false vainglory of the dragoons, but after the solid glory of maidens of pease. I am no longer looking for my own glory. There is another who is seeking it for me and is judging it. This order is the most Christian King following the opinion of his Council and his apostolic Sanhedrin, who grants me glory so that I myself might experience that God's will is perfect, that will of the law is just, the King's will is good, and that of the Queen pleasant, decent, and proper, because the Son of Man came to save what was lost. After this conversation, I quickly left the room and hurried to my bedroom, where I wept bitterly. Mademoiselle Bertin closely followed me and uselessly proposed both a drink and smelling salts in order to console me. I stopped crying only when my tears naturally dried up. Mademoiselle Bertin, as a crafty member of the Court, took advantage of my weekness by saying: "You are certainly not unaware of the joy experienced by the public in Paris when they heard sung the verses about the Heroine from Tonnerre, which were recently printed and are being sung throughout France." That was the only thing that calmed me in my distress, for when a heart is not entirely dedicated to God it is partly attached to this world. Only vanity can console such an individual because this world prefers human glory to the divine.

And so that it. Thats the moment that d'Eon "cried for hours" after being dressed by Mademoiselle Bertin. So what is d'Eon trying to communicate to the reader in this excerpt?