#like i get it if it was historical fiction but when authors include false narratives in biographies with zero factual basis then yikes

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

obviously, i love when tv shows resort to adapting defamatory rumors about the borgias, in fact it makes stuff spicier for good television! but i have that pet peeve and it is the false narrative with zero factual basis that i keep encountering while reading biographies about the house of borgia that the scholars really need to fuck off with them, and it's the whole irritating narrative that juan is the pope's favorite son, and cesare is consumed by jealousy towards him. which is total bullshit when cesare in fact received so much affection and appreciation from the pope as much as juan received (if not more than juan) cesare was the one who has always been consistently by their father's side and enjoyed immense popularity in rome, even among the artists who hailed him as the most handsome man in italy, and machiavelli was all over him. basically cesare was the renaissance's main prince. so there's nothing that indicates that cesare is jealous of juan over literally anything, and it's just the biographers being overly dramatic about him by giving him the "from zero to hero" trope (read maria bellonci's 'the life and times of lucrezia borgia' because she dives deep into this topic)

and no, cesare didn't hate juan. it's quite the opposite! his letters to his younger brother are full of tenderness, guidance, and fraternal love. it's another borgia famous rumor that needs to die down in biographies.

let's take sarah bradford (the author of 'lucrezia borgia: life, love, and death in renaissance Italy' and cesare borgia: his life and times) for example, and how she deliberately cut the part where cesare signs his letter to juan with "dal vostro fratello che vi ama com se stesso." translated as "from your brother who loves you as himself" because of her unnecessary haterism towards juan since she likes hyping cesare at his expense.

she also manipulated a document about the ambassador who visited cesare. here's a snippet from her book:

the actual translation from the document (praising both brothers) :

at this point, i'm convinced that if sarah bradford (and authors like her) didn't burst blood vessels for one minute by projecting her one-sided beef towards juan onto cesare with her unfair, incorrect statements of him she might start getting chills and have a stroke

that's it for now! i'm planning to make a masterpost about stuff like that because there are a lot of infamous rumors that some biographers tend to resort to, which is truly exhausting lol

#like i get it if it was historical fiction but when authors include false narratives in biographies with zero factual basis then yikes#anyway read emma lucas's “lucrezia borgia” for a goodass biography about the borgias#make sure you check gustavo sacerdote's “cesare borgia” as well !!#me being offended on cesare's behalf bc he's always paintef as a loser???#and juan is always getting clocked for nothing i gotta stand beside him sometimes#house of borgia#the borgias#biography#biografia#borgia#cessre borgia#juan borgia#the borgia family#books#reading#historical drama#historical fiction#historical figures#history#historical

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Preserving the Flow: A Water Conservation Crusade

DEFINITIONS

STORY: A narrative about people and events, usually including an interesting plot, is a story. A story can be fictional or true, and it can be written, read aloud, or made up on the spot. Journalists write stories for newspapers, and gossip spreads stories that may or may not be true.

TALES: A description of interesting��or exciting things that happened to someone, often one which is not completely true about every��detail.

SCIENCE FICTION: Science fiction is a genre of speculative fiction, which typically deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts such as advanced science and technology, space exploration, time travel, parallel universes, and extraterrestrial life.

I thought what I was living would not happen until a decade later. My name is Adrian Celi, and I am a fifty-year-old man in 2056 brushing his teeth when, after tasting delicious ramen, suddenly, the water gap stopped dropping water.

AVOIDING NIAGARA FALLS' EXPLOSION

I thought what I was living would not happen until a decade later. My name is Adrian Celi, and I am a fifty-year-old man in 2056 brushing his teeth when, after tasting delicious ramen, suddenly, the water gap stopped dropping water.

"I just paid like twenty dollars for the service last week, this makes not no sense." was my first thought after looking at the gap. Then, I remember that someone told me that he watched a video showing water was scarce around the world. Definitely, these were our last weeks with water on our planet. Absolutely, I had around zero drops of water.

"Nowadays, we have the technology for time travel; it is not madness to try to change something and save the world, right? We can not give up." I said insecurely.

"Woof," my dog barked.

I understood it as "Go on."

Subsequently, I decided to infiltrate myself into a time-travel corporation, and I selected the time I wanted to fall, and I did not think too much.

"I expect I selected the correct place and time," I thought while walking around the biggest water contamination in history, "The Niagara Falls explosion."

Importantly, the Niagara Falls explosion was a catastrophic event in 1930 where an atomic bomb was thrown into Niagara Falls, causing millions of liters to get contaminated. I advised the authorities of the city to be prepared for the following event.

They did not believe me, but I made them doubt because they checked the radars. They saw the missile, and the authorities went ahead and broke it down. I avoided this heavy historical event.

Finally, I could not return home without leaving a message to the humanity of 2030. Furthermore, I saw that there were news reporters in the streets. Therefore, I decided to get close and said, "People of this amazing world, calm down but take care with the amount of water you waste at home, stop contaminating it, you do not know when the water of our planet will end. If you want a better world, you can start with the change."

After this message, I returned to 2056. I ran to my bathroom to check out if everything was good, and when I opened the water gap, I saw the water, a special phrase came to my mind, "I did it". Because of this, I went to celebrate by eating spaghetti.

REFERENCES

References

(Luckhurst, n.d.) Luckhurst. (n.d.). History of science fiction. Google Academic. https://books.google.com.ec/books?id=F3JU3SJ5fDIC&q=history+of+science+fiction&pg=PP6&redir_esc=y#v=snippet&q=history%20of%20science%20fiction&f=false

(STORY, n.d.) STORY. (n.d.). Vocabulary.com. https://www.vocabulary.com/dictionary/story

(Tale, n.d.) Tale. (n.d.). Longman. https://www.ldoceonline.com/dictionary/tale

I created this image on the Canva IA site. I wrote the following prompt: "Create an image of an explosion in Niagara Falls".

0 notes

Note

Hi. You made a post a couple of days ago about how queer historical fiction doesnt need to be defined only by homophobia. Can you expand on that a bit maybe? Because it seems interesting and important, but I'm a little confused as to whether that is responsible to the past and showing how things have changed over time. Anyway this probably isn't very clear, but I hope its not insulting. Have a good day :)

Hiya. I assume you're referring to this post, yes? I think the main parameters of my argument were set out pretty clearly there, but sure, I'm happy to expand on it. Because I'm a little curious as to why you think that writing a queer narrative (especially a queer fictional narrative) that doesn't make much reference to or even incorporate explicit homophobia is (implicitly) not being "responsible to the past." I've certainly made several posts on this topic before, but as ever, my thoughts and research materials change over time. So, okay.

(Note: I am a professional historian with a PhD, a book contract for an academic monograph on medieval/early modern queer history, and soon-to-be-several peer-reviewed publications on medieval queer history. In other words, I'm not just talking out of my ass here.)

As I noted in that post, first of all, the growing emphasis on "accuracy" in historical fiction and historically based media is... a mixed bag. Not least because it only seems to be applied in the Game of Thrones fashion, where the only "accurate" history is that which is misogynistic, bloody, filthy, rampantly intolerant of competing beliefs, and has no room for women, people of color, sexual minorities, or anyone else who has become subject to hot-button social discourse today. (I wrote a critical post awhile ago about the Netflix show Cursed, ripping into it for even trying to pretend that a show based on the Arthurian legends was "historically accurate" and for doing so in the most simplistic and reductive way possible.) This says far more about our own ideas of the past, rather than what it was actually like, but oh boy will you get pushback if you try to question that basic premise. As other people have noted, you can mix up the archaeological/social/linguistic/cultural/material stuff all you like, but the instant you challenge the ingrained social ideas about The Bad Medieval Era, cue the screaming.

I've been a longtime ASOIAF fan, but I do genuinely deplore the effect that it (and the show, which was by far the worst offender) has had on popular culture and widespread perceptions of medieval history. When it comes to queer history specifically, we actually do not know that much, either positive or negative, about how ordinary medieval people regarded these individuals, proto-communities, and practices. Where we do have evidence that isn't just clerical moralists fulminating against sodomy (and trying to extrapolate a society-wide attitude toward homosexuality from those sources is exactly like reading extreme right-wing anti-gay preachers today and basing your conclusions about queer life in 2021 only on those), it is genuinely mixed and contradictory. See this discussion post I likewise wrote a while ago. Queerness, queer behavior, queer-behaving individuals have always existed in history, and labeling them "queer" is only an analytical conceit that represents their strangeness to us here in the 21st century, when these categories of exclusion and difference have been stringently constructed and applied, in a way that is very far from what supposedly "always" existed in the past.

Basically, we need to get rid of the idea that there was only one empirical and factual past, and that historians are "rewriting" or "changing" or "misrepresenting" it when they produce narratives that challenge hegemonic perspectives. This is why producing good historical analysis is a skill that takes genuine training (and why it's so undervalued in a late-capitalist society that would prefer you did anything but reflect on the past). As I also said in the post to which you refer, "homophobia" as a structural conceit can't exist prior to its invention as an analytical term, if we're treating queerness as some kind of modern aberration that can't be reliably talked about until "homosexual" gained currency in the late 19th century. If there's no pre-19th century "homosexuality," then ipso facto, there can be no pre-19th-century "homophobia" either. Which one is it? Spoiler alert: there are still both things, because people are people, but just as the behavior itself is complicated in the premodern past, so too is the reaction to it, and it is certainly not automatic rejection at all times.

Hence when it comes to fiction, queer authors have no responsibility (and in my case, certainly no desire) to uncritically replicate (demonstrably false!) narratives insisting that we were always miserable, oppressed, ostracised, murdered, or simply forgotten about in the premodern world. Queer characters, especially historical queer characters, do not have to constantly function as a political mouthpiece for us to claim that things are so much better today (true in some cases, not at all in the others) and that modernity "automatically" evolved to a more "enlightened" stance (definitely not true). As we have seen with the recent resurgence of fascism, authoritarianism, nationalism, and xenophobia around the world, along with the desperate battle by the right wing to re-litigate abortion, gay rights, etc., social attitudes do not form in a vacuum and do not just automatically become more progressive. They move backward, forward, and side to side, depending on the needs of the societies that produce them, and periods of instability, violence, sickness, and poverty lead to more regressive and hardline attitudes, as people act out of fear and insularity. It is a bad human habit that we have not been able to break over thousands of years, but "[social] things in the past were Bad but now have become Good" just... isn't true.

After all, nobody feels the need to constantly add subtextual disclaimers or "don't worry, I personally don't support this attitude/action" implied authorial notes in modern romances, despite the cornucopia of social problems we have today, and despite the complicated attitude of the modern world toward LGBTQ people. If an author's only reason for including "period typical homophobia" (and as we've discussed, there's no such thing before the 19th century) is that they think it should be there, that is an attitude that needs to be challenged and examined more closely. We are not obliged to only produce works that represent a downtrodden past, even if the end message is triumphal. It's the same way we got so tired of rape scenes being used to make a female character "stronger." Just because those things existed (and do exist!), doesn't mean you have to submit every single character to those humiliations in some twisted name of accuracy.

Yes, as I have always said, prejudices have existed throughout history, sometimes violently so. But that is not the whole story, and writing things that center only on the imagined or perceived oppression is not, at this point, accurate OR helpful. Once again, I note that this is specifically talking about fiction. If real-life queer people are writing about their own experiences, which are oftentimes complex, that's not a question of "representation," it's a question of factual memoir and personal history. You can't attack someone for being "problematic" when they are writing about their own lived experience, which is something a younger generation of queer people doesn't really seem to get. They also often don't realise how drastically things have changed even in my own lifetime, per the tags on my reblog about Brokeback Mountain, and especially in media/TV.

However, if you are writing fiction about queer people, especially pre-20th century queer people, and you feel like you have to make them miserable just to be "responsible to the past," I would kindly suggest that is not actually true at all, and feeds into a dangerous narrative that suggests everything "back then" was bad and now it's fine. There are more stories to tell than just suffering, queer characters do not have to exist solely as a corollary for (inaccurate) political/social commentary on the premodern past, and they can and should be depicted as living their lives relatively how they wanted to, despite the expected difficulties and roadblocks. That is just as accurate, if sometimes not more so, than "they suffered, the end," and it's something that we all need to be more willing to embrace.

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Contendings of History and Seth

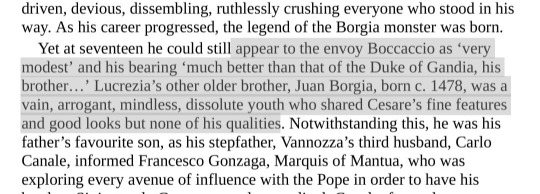

Seth as a serpent-slayer (MET) It's safe to say that the myth of Osiris is one of the only non-Greek myths to enjoy a comparable degree of recognition in modern popculture. There are few direct adaptations, sure, but the core narrative is well known, and as a result works themed after ancient Egypt use Seth as a villain almost without fail if only the premise allows the use of fantastical elements. However, in this article I will instead examine the other side of Seth, and especially his role as a protagonist of myths in his own right, including the historical circumstances of this development. While I mostly want to introduce you to a little known but fascinating world of heroic(?) portrayals of Seth, naturally I will also cover Seth's later loss of relevance and complete vilification to explain why it survived as the dominant tradition.

Early history of Seth

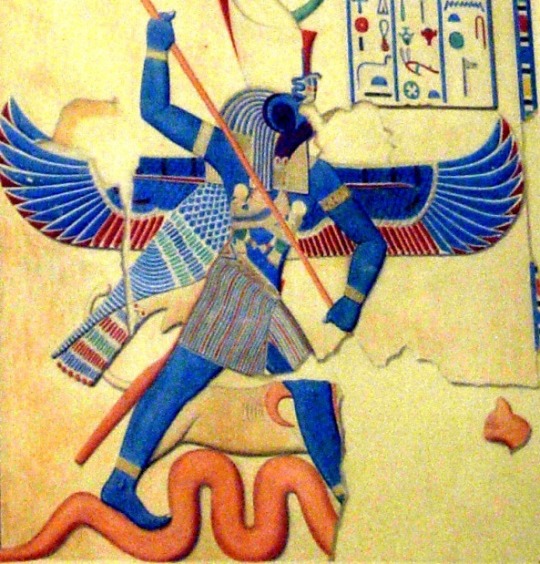

Seth protecting Ra from Apep (wikimedia commons) From the dawn of recorded history Seth's status in Egyptian religion was ambivalent, and it continues to be a topic of heated debate among researchers what degree of popularity he enjoyed in particular very early on. Some aspects of Seth character, like his evident interest in both men and women and whether it reflects broader Egyptian cultural norms (or if it’s merely yet another way in which Seth was an outsider among gods and men, as the author of the first monograph dealing with Seth proposed in the 1960s) are likewise a hotly debated topic. Seth was associated with many animals, such as the hippopotamus and the crocodile, but his main symbol is the sha or “Seth animal” which is regarded as either a mystery or a fictional creation, and in Egyptian texts inhabits zones inhospitable to humans. Seth was called “the god of confusion” by Herman Te Velde (the first writer to dedicate a monograph to him) and while this opinion has been since called into question, it is undeniable that it’s hard to form a coherent image of him. In addition to various versions of the well known myth mentioned above there are other instances of combat between Seth and Horus (most likely initially a distinct myth combined with the narrative about Osiris’ death and resurrection at a later date) and of Seth as a menace to the established order. Some of the Pyramid Texts present even the human followers of Seth as enemies to be conquered (which is held by some researchers a mythical memory of strife between local kings before the unification of Egypt). . However, there are also texts where Seth is a rightful member of the Ennead; where he and Horus act in harmony as protectors of the ruler; where he assists pharaohs in their resurrection in the afterlife; and even to Seth as one of the gods responsible for returning Osiris to life. A recurring motif in texts dealing with the afterlife in particular is a description of Seth offering a ladder to the dead who can reach some destination themselves. Mentuhotep II of the XI dynasty seemingly had Seth and Hathor depicted behind his throne in art; Hatshepsut described Seth positively as well. Personal names invoking Seth are known, too; and as established by Willam Berg in his studies of a different ambivalent deity, “children are not called after spooks.” Seth's ambiguous character made him ideal to represent The Other in Egyptian culture – the foreigners, especially these arriving from the Levant, their culture, and generally “un-Egyptian” traits. In that capacity, he functioned as an “ambassador” or “minister of foreign affairs,” to put it in modern terms. Or perhaps a foreigner in his own country, so to speak. As a result, he came to be associated with a group of deities which, while part of the official pantheon, had their origin outside Egypt.

The Ramessides and foreign gods

Generally speaking, there were two primary sources for foreign deities incorporated into Egyptian religion: Levantine trade centers like Gebal (Byblos in Lebanon) or Ugarit (Ras Shamra in Syria); and Egypt's vassal/enemy/ally/very occasional ruler Nubia (roughly corresponding to present day Sudan). Libyan influence was smaller, and to my knowledge there is no evidence of any major impact of Egypt's other trading partners (Punt, located near Horn of Africa, and Minoan Crete; the latter absorbed many Egyptian influences instead, though) or enemies (like the Hittites) on religion. The peculiar history of Seth is related to the the first of these areas. Early researchers saw the “Syrian” deities as worshiped at best by slaves or mercenaries – they didn't fit neatly into the image of Egypt presented by some royal inscriptions: an unmovable, unchanging and homogeneous country, a vision as appealing to absolute rulers in the bronze age as it was to many 19th and 20th century researchers. However, the truth was much more complex, and in fact some of the best preserved accounts of foreign cults in Egypt indicate that the process was in no small part related to the pharaohs themselves. For example Ramses II in particular was an enthusiast of Anat, as evidenced by statues he left behind:

Ramses II and Anat (wikimedia commons) He also named his daughter Bint-Anat (“daughter of Anat”) and his favorite pets and possessions bore Anat-derived names too. Not only only Ramses II himself, but the entire XIXth dynasty – the “Ramessides” (a term also applied to the XXth dynasty) - was particularly keen on these imported deities. Curiously, one of its founders was named Seti - “man of Seth,” and Seth was seemingly the tutelary deity of his family. The well known case of Ramses II's red hair might be connected to this – this uncommon trait was associated with Seth. As a result of the Ramessides' rise to power Seth became one of the state gods in Egypt, alongside heavyweights like Amun, Ptah or Ra. However, it's also safe to say that he was popular in everyday cult among commoners, as evidenced by finds from camps for workers partaking in various construction projects.

Part of Egypt of the Ramessides at its maximal extent (in green; wikimedia commons) During the discussed period, Egypt was as the peak of its power, both military and cultural; the “other” recognized Egypt's power. Weaker states in the proximity of Egypt paid tribute, while the more distant fellow “superpowers”of the era (the Hittites and the Mitanni, rivals of Egypt in Syria and the Levant, and the more distant Kassite Babylon) bargained with Egypt for dynastic marriages, luxury goods or craftsmen. While some foreign rulers didn't necessarily get that the pharaohs might not want to play by their rules and expressed frustration with that in their letters sometimes (see a particularly funny example below), overall the relations were positive, and resulted in a lot of interchange between cultures.

(source) The incorporation of foreign deities into Egyptian pantheon was a phenomenon distinct both from the well known practice of interpretatio graeca and from the monumental Mesopotamian god lists, and foreign gods were adopted rather selectively. Some researchers propose that the incorporated deities were often chosen because their sphere of influence wasn't covered by any native god. For example, Astarte (more accurately Ashtart or Athtart, considering the Ugaritic orthography; however the Greek spelling is used in literature to refer to the Egyptian version and I'll stick to that) was associated with horses and chariot warfare. As the animal wasn't known in Egypt in the formative period of the state, it wasn't among the symbols of any local deity; at the same time chariots were a prominent component of the Egyptian military at the height of its power, and as such required a deity to be put in charge of it. Six deities of broadly “Syrian” origin are usually listed among Egyptian gods in modern scholarly literature: Anat, Astarte, Resheph, Houron, Baal (the Ugaritic weather controlling one) and Qadesh. Of these, four were pretty similar to their original versions. Qadesh is a complex case as it's uncertain if such a deity existed outside Egypt – it's possible she developed as a combination of a divine title (“the holy one”) and the general Egyptian perception of foreign religion. Some scholars in the past asserted she is simply Athirat/Asherah but this interpretation relied on the false premise of Athirat forming a trinity with Anat and Ashtart and the three of them being the only prominent goddesses in cities like Ugarit. There are also curiosities like Chaitau, a god with Egyptian name (“he who appears burning”) but attested only in sources from Levantine cities (though ones written in hieroglyphics) and in magical formulas of similar origin. Baal is the most puzzling case: simply put, it's clear Baal was introduced to Egypt. It's clear Baal was depicted in Egyptian art. It's even clear that Egyptians knew that Anat and Astarte were deities from Baal's circle back at home, and that Baal was tied to a narrative about combat with the sea. And yet, it's not easy to say where the Egyptian reception of Baal ends and where Seth starts. Baal's name was even written with the Seth animal symbol as determinative. When exactly did this identification first occur is unknown: while it would be sensible to assume the Hyksos, a Canaanite group which settled in Egypt and briefly ruled the Nile delta, are responsible, there is some evidence which might indicate this already happened before.

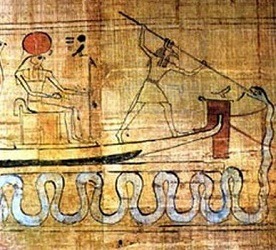

Baal and Seth

Baal was a natural match for Seth: Seth represented the foreigners, Baal was the most popular god of the foreign group most keen on settling in Egypt; Baal has a somewhat unruly character in myths; both rule over storms and have a pronounced warrior character. Additionally, both of them were depicted as enemies of monstrous serpents. Baal was identified with Seth in Egypt, but in turn Seth became more Baal-like too. So-called “Stela of year 400” depicts an entity labeled as Seth more similar in appearance to Baal due to the human face and Levantine, rather than Egyptian, garb:

(source) It is well known that the main myth of Baal, in Ugarit the first part of the “Baal cycle,”describes his combat with the sea, personified by the god Yam, seemingly described both as humanoid and serpentine. In Egypt, this narrative was associated with the composite Seth-Baal, and a fragmentary version is recorded in the so-called Astarte papyrus. Curiously, it was actually discovered long before the Baal cycle itself – however, it only became a subject of in depth studies in the wake of the discovery of Ugarit. There are also many similarities to the Hurrian myth “Song of the Sea,” known only from fragments, and to the Song of Hedammu from Hittite archives. While in the Ugaritic version Baal fought the personified Sea against the wishes of the head god El, in the Egyptian version the confrontation happens because the Ennead fears Yam, who threatens to flood the earth and demands tribute, much like the Hurrian Sea. Before Seth properly enters the scene, we learn about how Ptah and Renenutet, a harvest goddess, appeal to his associate Astarte (as already noted before viewed as Ptah's daughter in Egypt), hoping she'll act as a tribute bearer. Astarte is described as a fearsome warrior; however, she is not meant to fight Yam herself, but merely temporarily placate him. She seemingly strips down and brings offerings – this is, once again, closer to the Hurrian than Ugaritic version, where Shaushka, an “Ishtar type” goddess like Astarte, seduces the sea monster Hedammu in a similar way. It is not clear if Yam is interested, though - in fact he appears to question why Astarte isn’t dressed (possibly mocking what must’ve been a humiliating situation for a warrior deity, I’d assume). Eventually, Seth arrives and presumably fights Yam, likely with Astarte's help - the rest of the papyrus is too poorly preserved to decipher, but as indicated by the foreign equivalents Seth and Astarte win. This is confirmed by the Hearst Medical Papyrus, imploring Seth to expel illness from the treated person just like he vanquished the personified Sea. The Ugaritic version of the myth doesn’t include a tribute scene among surviving fragments, though it’s worth pointing out that the Ugaritic Ashtart/Astarte cheers on Baal during his battle against Yam and berates him for not acting quick enough, which is easy to interpret as hostility caused by a similar episode. Many researches assume that it existed among the lost fragments of the Baal Cycle tablets, though this is for now purely speculative. A variant of the myth of Seth and Horus - The Contendings of Horus and Seth - presents a further curious case of Seth-Baal syncretism, this time incorporated into well established Egyptian myth rather than an imported foreign one. Seth and Horus compete for the right to rule after Osiris' death. Ra thinks Seth is the better option to nominate as a successor because Seth killed Apophis on his behalf, but a few other of the elder gods disagree and try to delay the process by insisting to ask various deities to provide their expert opinions. These generally favor Horus much to Ra's annoyance, but he can't go against them so he insults Horus (calling him "feeble and weak-limbed" and criticizing his hygiene) but doesn't stop his rise to power. The semi-humorous portrayal of Ra is rather unusual; in addition to showing annoyance with other gods, at one point he vanishes, and only agrees to return because Hathor lured him out. It seems Horus' mother Isis insults Seth in response to Ra's comments. Seth, offended, refuses to partake in the divine assembly unless Isis leaves; Ra orders that and the gods gather again without her. However, Isis disguises herself and asks Seth who should inherit first, a child or a brother who can provide for himself (and is a foreigner), to which Seth replies that the former; this was a trick, obviously, and Isis holds it as proof that Seth forfeited his right to rule, which Ra accepts. After multiple chaotic tribulations (including the [in]famous lettuce episode as well as Horus decapitating his mother because he decides she doesn't do enough) Horus is re-declared king but Ra, implored by Ptah (otherwise absent from the myth) gives Seth two wives (eg. Anat and Astarte; this solution was suggested already earlier by the gods providing the opinion; some authors question if they are meant to be Seth’s wives or merely allies, much like the relationship between Baal, Anat and Ashtart in Ugarit is considered debatable) and the storm clouds as his new domain. He is to strike fear into hearts of men, but will also get to be treated as if he were Ra's own son. Considering the emphasis on storm and the mention of Anat and Astarte, it's pretty clear to me that Egyptians essentially invented their own Baal backstory meant to integrate the foreign tradition with their own by recasting Baal and Seth as the same entity. The text is however unusual because of its humorous tone – the gods insult each other, act ineptly and all around hardly provide an inspiring example. Perhaps the focus on Seth made this possible. As a final note before I'll move on to times much less prosperous for Seth it's worth to mention that not only Baal but also other foreign gods were at times equated with Seth. The Libyan god Ash was conflated with him in the western oases, while treaties with the Hittites assign the name of Seth to various members of their pantheon, including the Baal-like Tarhunna (equivalent of Hurrian Teshub) but also the sun goddess of Arinna.

Demonization of Seth

While in the late bronze age Seth greatly benefited from his role as a god of foreigners, in later periods this has proven to be his undoing. Egypt couldn't maintain its power forever, and eventually fell to the Assyrians, who showed little respect for local culture and looted Thebes. While the Assyrian domination was only temporary, it severely damaged the country, and a spiritual scapegoat was needed to reconcile the carnage with the idea that Egypt was a land chosen and protected by the gods. The change seemingly occurred under the rule of Psamtik – in a new version of the myth of Seth and Horus, Seth not only lost decisively, but also was punished afterwards, and religious texts spoke of a “rebellion”of Seth. Seth was never associated with Ashur, the head god of the Assyrians, before, but in Egyptian imagination he was blamed for bringing the invaders under “his” command to ravage and subjugate the country. A mythical text has Isis implore Ra to punish Seth for robbing temples, much like the Assyrian armies did. Even later accounts tell various tales about Seth being punished, either gruesomely (a few texts recount massacred of towns belonging to Seth) or humorously (for example in one text Thoth makes him impotent with a spell) and exiled from among gods. There's evidence that the worship of Seth, previously commonplace, came to be abhorred and depictions of Seth were destroyed or altered. A famous example is a Seth statue converted to look like Knhnum or Amun instead:

Seth no more (wikimedia commons) A late relief from Edfu, from the Ptolemaic times, seems to indicate that even Seth's role as a guardian of the solar barge was lost: Seth, depicted as a hippopotamus, was defeated by Horus from the solar barge of Re. However, while Apep is usually depicted as huge and menacing, hippo Seth is tiny and pathetic.

Seth as a tiny hippo representing the forces of chaos (wikimedia commons) Curiously, despite the official policies, which continued under Ptolemaic rule, it seems that until the 2nd century CE, Seth continued to be popular in the Dahkleh oasis, possibly even serving as the main deity there. Sadly due to lack of research I am unable to provide any more detailed information about that.

Closing remarks

Even further demonization of Seth is evident in the fact that the Greeks and Romans referred to Seth as Typhon, leaving no room for ambiguity of interpretation. As the Greek accounts of the late version of Seth were all that was known for centuries due to ability to read hieroglyphic writing vanishing with the advent of new religions, it remains dominant in media today. Perhaps it would be beneficial to leave some room for the serpent-slaying hero Seth hanging out with foreign deities in modern works, though? Surely his peculiar outsider status is even more appealing to modern readers than it was to the public of the Ramesside period.

Bibliography

N. Ayali-Darshan, The Other Version of the Story of the Storm-god’s Combat with the Sea in the Light of Egyptian, Ugaritic, and Hurro-Hittite Texts

G. Beckman, Foreigners in the Ancient Near East

M. Dijkstra, Ishtar seduces the Sea-serpent. A New Join in the Epic of Hedammu (KUB 36, 56+95) and its meaning for the battle between Baal and Yam in Ugaritic Tradition

T. J. Lewis, ʿAthtartu’s Incantations and the Use of Divine Names as Weapons

D. Schorsch and M. T. Wypyski, Seth, "Figure of Mystery"

D. T. Sugimoto (ed.), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite - especially the chapters ‘Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts by M. S. Smith and Astarte in New Kingdom Egypt: Reconsideration of Her Role and Function by K. Tazawa

H. Te Velde, Seth, God of Confusion: A Study of His Role in Egyptian Mythology and Religion

P. J. Turner, Seth - a misrepresented god in the Ancient Egyptian pantheon? (PhD thesis)

C. Zivie-Coche, Foreign Deities in Egypt

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

WHAT IS THE LOONAVERSE? PART 2 – THE NARRATIVE DEVICES

LOONA is special among K-pop for its immersive storyline. These girls are not just k-pop idols performing a song, they also perform a story and that story is what we call the Loonaverse.

So, what is the Loonaverse? In a few words: The world and story that LOONA inhabits.

Yeah. Duh. But what is it?

Well… it’s complicated.

The Loonaverse is a fictitious story that borrows elements from real science and fantasy to build its world but also uses allegories, metaphors, allusions and other literary devices to tell its story. Our job as spectators (and specifically us theorizers) is to look beyond those devices to understand the message they are trying to send. In this post I’ll attempt to explain the numerous literary devices used to narrate the story of the Loonaverse.

So, these 2 things are LAW:

Each girl has two conflicts: an external one and an internal one.

The LOONAVERSE story is one of fantasy and mystery.

INTERNAL CONFLICT VS EXTRNAL CONFLICT

Or as I like to call it: UNIT vs SOLO

I’ve explained how the girls are trapped in a time loop and how escaping it was their overarching goal. This is the external conflict of the Loonaverse. The progression of this storyline is seen mainly in the Sub-Unit MVs and LOONA MVs but also in some teasers and other videos like Cinema Theory. The conflict is external because: 1) It comes from the outside. 2) The characters not have power against it, at least not at the beginning. 3) The conflict has effect over multiple people.

Also…

Every character has an internal conflict. A personal story. Each girl perceives the world differently and that changes the way they act and interact with each other. It is internal because: 1) It comes from within the person. 2) They themselves may be the cause for the conflict. 3) The conflict has effect on only one person: themselves. This Internal conflict is presented to us in the Solo MVs. Every solo MV is a window to the character’s mind. While the solo MVs are tangentially related to the main external conflict, they mostly focus on the internal conflict of the character.

External and Internal conflicts often mix and interlace each other to create a wider story. We will see how the external conflict fuels the internal conflicts of the girls and how their internal conflicts will shape the way they act towards solving the external conflict.

FANTASY AND MYSTERY

What is fantasy? The genre of fantasy is described as a story based in a world completely separate from our own. It usually features elements or magical/supernatural forces that do not exist on our own world. It is not tied to reality of science.

Wait a minute. You just spent an entire post explaining the science of the Loonaverse. You can’t call it fantasy now. Well yes, yes I can. Since most of the scientific elements I explained are theoretical, unproved in our world but in the world of LOONA they are a reality, a scientific reality. A reality that differs from our own, and thus a fantasy to us. But regardless of that the reason I call the Loonaverse a fantasy is because of the themes it explores.

Fantasy is a broad genre, it is one of the oldest literary genres, being found in old myths. Some of the themes often found in fantasy stories include: tradition vs. change, the individual vs. society, man vs. nature, coming of age, betrayal, epic journeys, etc. All of these themes are very present in the Loonaverse. But I’ll delve into each one as we encounter them.

What is Mystery? The mystery genre is a type of fiction in which a person (usually a detective) solves a crime. The purpose is to solve a puzzle and to create a feeling of resolution with the audience. Some elements of a mystery include: the Crime that needs solving, the use of suspense, use of figures of speech, the detective having inference gaps, the suspects motives are examined in the story, the characters usually get in danger while investigating, plus these:

Red herring. something that misleads or distracts from a relevant or important question and leads the audience to a false answer.

Suspense. Intense feeling that an audience goes through while waiting for the outcome of certain events.

Foreshadowing. A literary device that hints at information that will become relevant later on.

I just though you should know these definitions.

In the Loonaverse, the “crime” is the time loop itself, and the mystery is finding a way to break it. Or so we think. In reality, the “How do we break the loop?” question is solved rather easily. But can we really call this a mystery if the main question is already answered? Yes! It may no be a mystery story for the characters themselves but because BlockBerry uses various mystery genre tropes while telling the story, it is a mystery TO THE AUDIENCE.

That’s right! WE are the detectives!

In a classical mystery, the detective examines all clues, motives, and possible alibis, for each suspect, or in our case, each character. The same way we analyze every MV, every interaction, every possible clue to where and when everything is happening.

The Loonaverse differs from a classic ‘Who done it?’ by establishing that no suspect is actually guilty. The crime IS the loop, but no girl is responsible for it (or so we think). Our job as detectives is not to figure out who is doing this but to explain how and establish an timeline of events that shed a light to what really happened. In that sense, our job resembles more closely a real crime investigation than a mystery novel.

LITERARY DEVICES

There are many literary devices an author can use to tell its story. Too many to cover them all in here, so I’ll focus on the most recurrent ones in the Loonaverse:

Allusion. Referring to a subject matter such as a place, event, or literary work by way of a passing reference.

Archetype. Reference to a concept, a person or an object that has served as a prototype of its kind and is the original idea that has come to be used over and over again.

Faulty Parallelism. the practice placing together similarly structure related phrases, words or clauses but where one fails to follow this parallel structure.

Juxtaposition. The author places a person, concept, place, idea or theme parallel to another

Metaphor. A meaning or identity ascribed to one subject by way of another. One subject is implied to be another so as to draw a comparison between their similarities and shared traits.

Motif. Any element, subject, idea or concept that is constantly present through the entire body of literature.

Symbol. Using an object or action that means something more than its literal meaning, they contain several layers of meaning, often concealed at first sight.

Genre. Classification of a literary work by its form, content, and style.

Some other literary devices worthy of your private investigation are: Negative Capability, Point of View, Doppelgänger, Flashback, Caesura, Stream of Consciousness, Periodic Structure, THEME, Analogy.

About Genre:

Genres are important because they give a story structure. They help an author tell the story in a way that makes it simple for the audience to understand what kind of story is being told. The classic genres of literature are Poetry, Drama and Prose. Some scholars include Fiction and Non-fiction.

In film there are a variety of accepted genres: Comedy, Tragedy, Horror, Action, Fantasy, Drama, Historical, etc. Plus a bunch of subgenres like Contemporary Fantasy, Spy Film, Slapstick Comedy, Psychological Thriller, etc. What defines a genre is the use of similar techniques and tropes like color, editing, themes, character archetypes, etc.

I point this out because the Loonaverse uses many genres to tell its story. Sure, the main story is a fantasy/mystery but every MV or Teaser has its own genre (especially the solo MVs). So, when I point out later that Kiss Later is a romantic comedy or that One & Only is a gothic melodrama, this is what I mean.

TLDR:

The Loonaverse is the world and story that LOONA inhabits. It borrows form real life science and fantasy elements to better tell its story. Each girl has an external conflict (escaping the loop) and an internal conflict (portrayed in the solo MVs). Both conflicts interlace to tell the story. The Loonaverse is a story of Fantasy because it takes place in a different world from ours and it is a Mystery because it is told using various mystery tropes. The story uses multiple literary and visual devices to tell it’s story and fuel the mystery.

REMEMBER: This is all my interpretation. My way of comprehending and analyzing the story. You don’t have to agree with everything. I encourage you to form your own theories. Remember: every theory is correct.

After all that you may be wondering what the story even is. And we’ll finally be getting to that. While I have my own interpretation of the timeline, themes and who did what. I think it’s more fun to slowly explore every brick instead of just summarizing it in one (incredibly long) post. I’ll do that much, much, much later. The journey will be just as interesting as the destination. I hope you’re in for the ride.

Let’s get to the real deal: The MVs. I’m going in chronological order so let’s start with girl No. 1!

Next: The bright pink bunny of LOONA: HeeJin’s ViViD.

#yeah i know its been months#life's tough kids give me a break#loona#loonaverse#loona theory#loonatism#heejin#hyunjin#haseul#yeojin#vivi#kim lip#jinsoul#choerry#yves#chuu#go won#olivia hye

86 notes

·

View notes

Note

(TW: sexual assault. Take care of yourself.) I won't be offended if you ignore this, or make your own post. I hope I don't offend YOU. But I'd like to hear your thoughts? RPF is abhorrent to me. I won't read it, even if it's an innocuous, 2 line appearance of Crosby so the fictional world is more real. It's putting words and actions into the mouths of REAL people. And to me the line is paper thin between that and the r*pe fantasy letter that Natalie Portman received as her 1st ever fan letter.

Firstly, I understand why RPF might make you uncomfortable and I’m not offended by your question at all. Keep in mind, these are my thoughts/opinions and I absolutely don’t expect everyone to share them, and that’s fine. So let's tackle a few things individually. 1. I think comparing RPF to that rape fantasy letter Natalie Portman received is a dangerous false equivalency. In one scenario, an adult man writes a terrible fantasy about a minor and then ensures to the best of his ability that the minor in question receive and read said fantasy without the ability to consent to its content. In the other scenario, (provided people are being responsible and respectful) you usually have an adult writing a fantasy for other like-minded adults. They do not want the person the fantasy is about to read or engage with it, and they use the available tagging and warning systems to ensure that people can consent, to the best of their ability, to consuming the story’s content. I know one of my friends who writes RPFs puts in all caps at the top of every fic she posts online something to the effect of “IF YOU FOUND THIS BY GOOGLING YOUR NAME TURN AROUND AND LEAVE.”

TL;DR I do not believe perverse power-seeking behavior that disallows consent can be equated to a genre of writing that, as a whole, usually ensures readers can consent to consume the content produced.

2. On the discomfort with “putting words and actions into the mouths of REAL people” thing. I think it’s important to remember that, historically, literarily speaking, some form of RPF has always existed. The Epic of Gilgamesh all the way back in the second millennium BC was a fictionalized version of (to our knowledge) a real Mesopotamian king. Nearly all of Shakespeare’s histories were fictionalized versions of real people and their exploits, and the Brontë sisters more or less role-played people who fought in and lived through the Napoleonic wars (the Duke of Wellington, for example) who were still living while they created these stories. As children, humans, in general, are prone to making fictional accounts of real people all the time. I’d wager that, at its base construction, we all do a bit of RPF writing, even if it’s solely in the privacy of our own heads, when we make assumptions about the humans around us and the parts of their lives or personalities that we do not actively see.

TL;DR I don’t believe anything is inherently wrong with RPF––in fact, I think it’s quite natural.

3. Now, I can understand discomfort over RPFs because they may feel like a divergence from more traditional fic about fictional characters. But I think it’s important to remember that the very concept of a celebrity involves a performative body. The public personas of celebrities are constructs, and those very constructs perhaps encourage fictional interpretations. I’ve never written RPF, but I believe it was @earlgreytea68 who said (and I’m paraphrasing, here) that RPF allows a degree of freedom that most fic does not because writers have a larger (or perhaps more empty) canvas with which to work. In a book or a TV show, a character often has a back story and explicit personality quirks, and the reader or viewer follows them home and sees who they are at night, alone, away from other people or when interacting with people they love. Obviously, we are not afforded this behind-the-scenes information about most celebrities, so an RPF writer essentially gets to make up their own character––their own ideas about who this person is behind closed doors/when the cameras are off––and superimpose those ideas onto a well-loved figure. Tl:DR Folks who write RPF are engaging in creative, fictional, writing, and I think, for the most part, they are well aware of the fact that their stories do not represent reality and perhaps prefer writing them because of the additional freedom of the genre.

4. All that being said, I do think it’s very important that RPF writers (and fic writers in general) are responsible and respectful in the way that they share their writing online. If someone writes an RPF and sends it to the real person in question, that is inappropriate behavior. If someone finds an RPF online and then takes it to the real person included in the narrative (despite the author’s clear intent to never share it with that person) that is inappropriate behavior. If a person posts fic online and does not properly tag it so readers can consent to their reading experience, that is inappropriate behavior. I feel these situations might be termed “abhorrent,” considering context, but I certainly do not think the very act of writing or reading RPF is abhorrent. TL;DR As long as writers share their RPFs responsibly, I support them and have no quarrel with them.

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

How afrofuturism gives Black people the confidence to survive doubt and anti-Blackness

by Anthony Q. Briggs and Warren Clarke

Afrofuturism, like the kind seen in Marvel’s Black Panther, allows Black people to imagine themselves into the future. Marvel Studios

In 2018, Black people globally got a signal of hope when director Ryan Coogler and Marvel Studios released the critically acclaimed movie, Black Panther. While few knew of the Black Panther as a superhero despite the comic being released in the 1960s, millions now know of him because of the film’s overwhelming success.

Its success can be due, in part, because of what it tells us about Black people’s futures. Many Black people — seeking belonging and better outcomes for their lives — have turned to afrofuturism as the source of optimism. According to afrofuturist expert and author Ytasha Womack, afrofuturism refers to “an intersection of imagination, technology, the future and liberation … Afrofuturists redefine culture and notions of Blackness for today and the future by combining elements of science fiction, historical fiction, speculative fiction, fantasy, afrocentricity and magic realism with non-western beliefs.”

Black Panther had Black people chanting “Wakanda Forever,” while many imagined that they too could put on the Black Panther suit to gain a sense of belonging. Black people, including Canadians, believed that Wakanda, the utopian city where the Black Panther resides, is a real place. For Black Canadians, Wakanda offers a place that exists outside the harsh reality of an anti-Black white settler narrative that is anti-Black.

Black legal scholar Lolita Buckner Inniss says anti-Black racism is deeply enmeshed in the Canadian social fabric. Anti-Black racism cuts deep enough so that many, if not all, Black Canadians feel there is no hope for a better future.

Leaving family but not tradition

Nnedi Okorafor’s Binti must deal with racism and isolation as she traverses a universe that does not value her people’s knowledge. (Tor Books)

Afrofuturism in cinema is but one source. Writer Nnedi Okorafor’s 2015 science fiction novella, Binti, features a Black woman protagonist named Binti Ekeopara Zuzu Dambu Kaipka. Binti is an intelligent woman leader of the Himba tribe whose genius gets her into to the prestigious Oomza University, which floats about the galaxy. Binti is the first member of the Himba ethnic people to attend the school. Her decision to attend is met with ridicule, laughter and threats to her life due to the fear and insecurities of her people.

Her people have never been allowed to imagine futures beyond their traditional way of life and identification with the land. Binti states:

We Himba don’t travel. We stay put. Our ancestral land is life; move away from it and you diminish. We even cover our bodies with it. Otjize is red land. Here in the launch port, most were Khoush and a few other non-Himba. Here, I was an outsider; I was outside.

She echoes the social challenges that Black people face when embarking upon new ways of living after leaving traditional family and cultural contexts. Often, their families and cultures pressure them to remain entrenched within the known confines of family, culture and community, rather than explore the new and unknown.

One of us, Anthony, was the first member of his immediate family to attend post-secondary education and graduate school. He wanted to apply to graduate school but had to fight internalized feelings of low self-worth that insisted he did not belong in academia. Indeed, a lack of self-confidence influenced the choice to avoid applying to programs that required a high grade-point average with a full scholarship because he did not believe he would be accepted.

Blazing a trail to a Black future

In her village, Binti had been one of the few who used knowledge to create peace in her tribe, so she had to overcome pressure to remain in the village in order to embrace new learning. On a spaceship, travelling from her village to the Oomza University, Binti as the only Himba at the university encounters another obstacle: the false assumption that people from her land are evil, dirty and primitive.

In one moment, one of the Khoush (a different lighter-skinned tribe) students touches Binti’s braids out of curiosity and without consent. Her hair is mixed with sweet smelling red clay and perfume called Otijze, which is connected to her cultural heritage. One of the Khoush students responds that it has a horrible smell, suggesting a passive discriminatory logic of sanitation.

One can observe strong echoes of the attitudes of privileged whites towards high-priority Black neighbourhoods whose inhabitants are stereotyped as criminal, irrational, impoverished and unintelligent. The book suggests that there is no such thing as neutral space and that structural inequities and racial inequalities make space and place difficult to navigate, especially in elitist environments.

But Binti is gripped by the challenge of the new. Her journey of self-discovery begins when she decides to leave village life, defying her ancestors’ dedication to their land and cultural identity. Binti explains that tribal knowledge was handed down orally as her father had taught her 300 years of oral lessons “about astrolabes including how they worked, the art of them, the true negotiation of them, the lineage … circuits, wire, metals, oils, heat, electricity, math current and sand bar.” Her mother had also transmitted mathematical insights and gifts, but never in formal educational settings. Family unity and protection were paramount.

Binti symbolizes the trailblazer who encounters politics, racism, stereotypes, ignorance, systemic inequalities, gender inequities, classism and so on. Additionally, she faces the strong pull of past traditions since she is the first member of her family and tribe to attend a formal educational institute.

youtube

Afrofuturism offers a way for Black people to envision their futures, as Missy Elliot’s futuristic music videos exemplify.

Some Black individuals living such stories will inevitably encounter feelings of isolation, lack of belonging and self-doubt. Their internal battles will pit self-trust and the drive towards the new against the safety and security of the past. They will have to develop a secure sense of self and an understanding that it does not matter how far they travel among the galaxies because everyone has unique gifts they can contribute to the universe.

Against the pull of anxieties and insecurities, Anthony graduated with a master’s degree and a PhD; he currently has a post-doctoral fellowship — yet is in another galaxy of his own among the stars.

Afro-Caribbean Black people living in white settler, colonized nations such as Canada face discrimination and negative stereotypes. Afrofuturism can enable Black communities to reimagine new possibilities, especially when the future trajectory for Black Canadians is at times uncertain.

About The Authors:

Anthony Q. Briggs, Research Fellow, Department of Sociology, Anthropology, Social Work and Criminal Justice, Oakland University and Warren Clarke, PhD student, Department of Sociology, Carleton University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

When the Forced Marriage Trope is Given Depth

The forced marriage plot is a venerated tradition in romance novels. So much so that today’s romance writers are twisting plots around like pretzels to try to make this trope plausible—and palatable—for the modern age. Usually, this involves business arrangments and marriages of convenience. The old school romance novels of my adolescence were more about king’s edicts and unbreakable betrothals to the last man on earth the heroine ever wants to marry—but with a sly wink toward lust to undercut her early hate.

The appeal of the forced marriage plot is the belligerent sexual tension for a start. Then it’s the softening. The something there that wasn’t there before. The hero becomes less of an ass. The heroine admits her initial impression was harsh. It’s classic Pride & Prejudiceor Beauty & the Beast. Gold standard stuff. From a practical point of the view, the forced marriage plot is a way for historical romance writers to have their Pride & Prejudice or Beauty & the Beast plot, give a nod toward social norms, and still include sex scenes.

But the forced marriage trope has a crucial difference—in both Pride & Prejudice and Beauty & the Beast examples, the narrative question is, “Will the heroine consent to marry the hero?” Her choice is centered. Elizabeth throwing Darcy’s proposal back in his face is one of the best examples of agency in all of romance (my personal favorite comes from North & South). We want to see the heroine stand up for herself because then it’s crystal clear that, by the end, she’s marrying for love. In the case of the forced marriage trope, the choice has been made for her, so her agency is compromised.

What does that do to the appeal of the trope? It messes it right up, that’s what it does.

For fans of messy romance—romance with stakes and grit and depth—this is can be a very interesting thing. If the author treads carefully. Treading carefully means hitting a few major beats:

Acknowledging the messed up nature of the situation. The hero especially needs to understand how getting a wife against her will is, you know, bad. Even if he starts out conceited or oblivious, it’s crucial that he learns to value consent above all else.

Giving the heroine a free and clear means of escape. Readers seem to swoon over the whole, ‘You’re too good for me! But I’m a selfish bastard so I’ll never let you go’ angle. In this trope, the alpha possessiveness vibe is more uncomfortable than usual. Tone it way down. Even Disney gets it right: When the Beast asks Belle if she can be happy with him in the 2017 version, she responds, “Can anyone be happy if they aren’t free?” The only answer is no and the Beast promptly lets her go.

Making the character change crystal clear. The reason the heroine decides to stay with the hero is make-or-break for this trope. Quivering thighs aren’t enough. Genuine, authentic change in the hero’s actions and the heroine’s understanding is a must. This cannot be lip service. It has to feel authentic and earned.

Why are these three beats so crucial? Because the very last thing we need is forced marriage itself romanticized as an institution. Forced marriage is and has been a source of pervasive evil in the lives of women. Google ‘forced marriage’ without the ‘romance’ at the end and you get a lifeline number to stop human trafficking. This trope emerged from a dark and dangerous place, as a lot of storytelling tropes do. No number of happy fictional endings will change that.

Most premises for this trope I’ve seen skirt the trope’s heart of darkness, ignoring the uncomfortable implications in favor of a few thrills. Which begs the question—does the popularity of the trope mean its readers are regressing or resisting progress? Are readers thinking that choice is too hard and wouldn’t it be nicer if someone chose a husband for them and it all worked out in the happily-ever-after? Maybe. Romance is escapism, after all. This trope and the soulmates trope are like the benevolent dictator theories of romance novels. Easy and unrealistic are what some readers are looking for when they pick up a romance novel.

As a champion for romance with stakes and grit and depth, that’s so not me. I want a happy ending, I do. But I also what to use the forced marriage trope to, like, explore my anxieties about the long line of forced marriages from which I’m likely descended. That’s why I need the heroine to continuously stand up for herself and the hero to completely understand her situation by the end. Those three beats I laid out above allow that arc to happen. They’re a formula for catharsis and that’s damn good drama. But the right to choose one’s life partner is a cornerstone of feminism for a damn good reason. For me, the story isn’t satisfying unless it actively tackles that issue.

One of the best examples of the forced marriage trope given depth comes from a movie almost no one saw called Child 44. Tom Hardy and Noomi Rapace star as Leo and Raisa Demidov a married couple in 1950s Russia. Leo is a WWII hero turned Captain in the Ministry of State Security. The plot focuses on Leo searching for a serial killer who targets young boys. His investigation is complicated because he’s going against the will of the government. Leo’s colleagues actively want to silence any evidence that their society—a paradise—could produce a murderer. But, as the reviews on Rotten Tomatoes will tell you, the thriller aspect is a bit of a letdown. The real meaty storyline is the evolving relationship between Leo and Raisa.

The first scene to introduce Leo and Raisa as a couple is a phenomenal piece of character work. Leo is telling the story of how he fell in love and married Raisa at a dinner party. The story is a common one: love at first sight. Leo saw Raisa, waxed poetic, and asked for her name. When he tracks her down again, she admits that she gave him a false one. The two tell the story in tandem, but the audience is clued into the fact that Raisa is telling her parts dutifully. It’s Leo who finds this story romantic as he confesses his devotion to his wife. The women of the group are touched. Raisa is cool and contained. She remains cool and contained when the couple has sex in their apartment. It’s a classic framing of marital discord. Leo is kissing her neck, clearly overcome by passion. And Raisa is turned away from him, frowning into middle-distance. In a few short scenes, the audience comes to understand that Raisa does not share her husband’s blind obedience to the Soviet Union. We wonder if she might be a spy or a traitor in some way. When Leo comes home after a hard day where a subordinate murdered a mother and father in front of their two young children, he seeks comfort from Raisa. She accepts that she should do this for him, but she does not actively comfort him.

The turn comes when Leo is handed a folder and told to investigate his own wife for treason. He knows that no matter what he finds over the course of his investigation there will be no mercy. The implication alone is damning. Leo follows Raisa, seeing her lose a fellow school teacher to soldiers. She seems too close to her principal, but nothing implicates her except that he loses her in the crowd. Leo talks to his adopted father, who cautions him that it’s better to give up his wife than to go down with her. Raisa shows up for dinner then and announces where she’d gone—to the doctor. She’s pregnant. Leo tears apart their apartment but finds nothing damning. Neither do his colleagues. The scene where Leo confronts Raisa about the investigation is heartbreaking. You can see on her face that she expects to be given up. You can see on his face how much this is tearing him up inside. In the end, he submits her innocence knowing that he is dooming them both. Sure enough, they are dragged from their beds. The character work here is that Raisa lets her husband hold her, she screams for him in terror. She clings to him when she thinks they will be killed.

But they are spared somewhat. They are able to leave Moscow with their lives and sent to a village in the middle of nowhere. Gone are the luxuries that her husband’s career afforded them. In exchange for her life, he has to give up everything. Raisa is cooler than ever. It’s fascinating. She tells him that it was all a test of loyalty—he should have denounced because “that’s what wives are for.” His show of love hardens rather than softens her toward him. But she does not betray him, even when his most evil coworker offers for her to return to Moscow as his mistress. She tries to leave him, but Leo stops her and brings her back home. He forbids her from leaving again.

It’s then that we learn that Raisa resents him for how much he loves her because, as we find out, she never had a say in it. That charming story he likes to tell? She remembers it very differently. She “cried for one week” when he proposed and then accepted out fear for what would happen to her if she declined a man of his stature. She was forced into this marriage, and now she’s bound to him even tighter because of his sacrifice. Hearing this breaks Leo’s heart into a million pieces. Honestly, the angst of this scene is everything I want in this trope. Her confession rocks Leo’s world. He has tears in his eyes because he’s realizing how much of a monster he has been in the eyes of the woman he loves but has never known. We also find out that Raisa lied about being pregnant to save her own life. She’s a survivor. She’s a complex thinker and feeler. It’s heartwrenching, deep stuff, people. Sign me the fuck up twice.

That’s the first of the major beats. Acknowledging the messed up nature of the situation.

Then the murder investigation starts in earnest. Leo has to go to Moscow and he’s afraid if he leaves Raisa he won’t be able to protect her. She doesn’t want to go anywhere with him. He tells her that if she comes to Moscow with him, she can stay there. He won’t make her return, and she never has to see him again.

There’s beat number two. Giving the heroine a free and clear means of escape.

But in Moscow, things change for Raisa. She is drawn into the investigation and sees how honorable it is. She comes to realize that the man she assumed to be the honest Russian sticking up for his countrywomen against the brutal government was an ideologue all along. The monsters of her world are becoming much less black and white. By the time we get to the moment when Raisa chooses to come back with Leo, we understand why she’s making that choice.

And then boy are we ever rewarded. We get to see Raisa stand up for her husband, soothe and comfort him. We see her protect him from would-be murdererstwice and Leo turn around and do the same thing for her. She is an equal partner in his investigation and his life. The events of the movie bring them together in a way that their sham marriage never could—and it’s a messy, complicated, harrowing thing to watch. In the end, this is a true romance because the couple gets a happy ending. So happy. I won’t spoil the last bit, but there is definitely a romance novel-worthy moment when Leo turns those puppy dog eyes on Raisa to ask her if she thinks he is a monster. And of course she no longer thinks that. Her understanding of him has changed. And his actions have changed—no longer does he presume her love and ignore her true feelings. No longer does he go along with the state mindlessly and play up the war hero bit. He’s a better man and she loves him for it. That’s a transformational love story.

Final beat nailed. Making the character change crystal clear.

Again, not going to say Child 44 is a perfect movie. But the love story? Is a perfect example of a thoughtful use of the forced marriage trope. More romance novels could stand to use it as a template.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

WELL it was an easy read and I finished the book already. I gotta do a classic Dani Vents About a Story post that will include significant spoilers, so be careful if you are reading/want to read The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargraves. I’m about to bitch about it a lot, but overall it was an interesting book that I’d still (mostly) recommend if you have an interest in historical fiction surrounding the Norwegian witch trials.

Most of it was really good, although a few theme threads and character arcs completely fell apart in the final act. I knew it was going to be dark-- again, 17th century witch trial shit-- but the actual “murder my favorite characters” bit thankfully didn’t begin until pretty late in the story, which lets the focus remain more on the lives of the women vs their horrific deaths. The author does a (mostly) great job at creating interesting characters you fall in love with, and succeeded immensely at bringing the landscape and village of Vardo to life.

BUT

IN THE LAST LITERAL FOUR PAGES, THE NARRATIVE TOOK ALL THE MEANING THAT THE PROTAGANISTS HAD CREATED OUT OF THEIR HARDSHIPS AND THREW IT OVER A CLIFF (LITERALLY! & EACH USE OF THIS WORD HERE HAS BEEN THE PROPER USE. although i guess a fictional event cannot be truly ‘literal’ BUT WHATEVER I AM NOT GETTING LOST IN THE WEEDS WITH PEDANTICS). I am so fucking mad, and it serves as a reminder to why I typically don’t read/watch many period pieces these days, unless it is a period setting in a fantasy/sci fi world. So many people think that in order to bE rEaLiStIc when writing about periods in history, you simply MUST be as grimdark as possible, especially with conclusions, but I find that perspective boring and uncreative as hell. Bitch it’s already fiction! it’s already lies! you are god in the universe you write, have some courage and don’t concede to established tropes that center on garish suffering to define the experiences of historically (& contemporaneously) marginalized people! At least in a medieval-set fantasy story, you get the vibes of the historical setting, but also your friends can swoop by on a dragon and rescue the innocent pants-wearing fisherwoman who is about to be burned alive by the racist woman-hating church.

Now don’t get me wrong, I love a story with a messy & unhappy ending. I even love an occasional grimdark story! But as I get older, I see & feel more the evils which inspired these historical events and how they still burden our world today, and I do not enjoy spending my free time reading/watching movies that are centered on suffering for suffering’s sake-- if I want a story about senseless violence & the underdogs who never win, I will just turn on the fucking news. SO, for me, the dark stories I do enjoy cannot just be traumaporn in a difference shell, the darkness has. to. make. sense. You can’t spend 300 pages on a woman overcoming her grief of losing her brother/father/fiancé/half her village & learning how to be a #StrongIndependantWoman, then have her just kill herself on the last page. It just isn’t narratively good, it just isn’t! And to be clear, the author could have gone WAYYYYYYYY darker in many places throughout the book & did not even come close to going full grimdark. I think overall she greatly succeeded at balancing hope & hopelessness. It was done so well in fact that I was lulled into a false sense of security that maybe just maybe there might be a way out for our ladies, a conclusion that didn’t end with the kind of complete misery that historic fiction tends to skew towards. But there is this overwhelming sense in the final few pages that, probably due to the aforementioned loyalty to perceived “historical accuracy”, she hadn’t included enough suffering (even though there is PLENTY of tragedy to go around by that point) & she didn’t know how to finish the story. So when in doubt, kill 👏 those 👏 gays 👏 (although we don’t know the fate of the other woman, who has entire chapters given from her perspective, but Meren just says bye & we never hear about Ursa again 😤)

Which brings us to, yeah, it did have gay shit like I thought, and up until the garbage of the last four pages, it was a very touching romance. But it too concluded in a way that is only satisfying if you squint, and adds to the inconsistencies that I mentioned above. I’ve never in my life said this before, and it makes me ill to even type this, but, *sob* it probably would have been a better story if the two women had remained platonic friends and no touch-a the booba. I know a lot of people think I’m One of Those cringe queers who will read/watch absolute garbage just if there is a queer person (which tbf I definitely also do sometimes, & it’s actually very valid of me, thank u very much), but if that were true I would have finished that awful Warming Trend book that I blogged about like 2 years go, or read any of the hundreds of stupid “subtext” trash that folks like to recommend, or ship Supercorp (no offense to anyone who ships them, I get it, Katie McGrath is hot, but come on, there is a perfectly good lesbian already on the show), or watched Glee. No, I do actually have some standards-- Are they super high, as a love-starved reader/viewer who uses romantic fiction as a primary means of escapism/coping with my shitty life? No, lmao. But as a writer, and as a queermo, nothing grinds my gears more than a badly executed lgbtq+ storyline.

Anyway, I just finished the book an hour ago so my crankiness & disappointment is raw and thus I am all over the place with this rant. I hope I’m not coming off as being too hard on the author, because despite it’s flaws, I am very glad to have serendipitously found The Mercies, and I look forward to checking out KMH’s other works. It’s been a long time since I’ve dug into a book and read it in just a few sittings like I did this, repeating “just one more chapter” for hours until it’s suddenly 3 am, and despite the fuckery to my sleep schedule it contributes to, the feeling is good-- it brings me back to simpler times when I actually was able to experience an ease from the constant uneasiness I always carry in my chest. Idk, moral of the story is that reading is fun, & when I get stuck in my Bad Turns & don’t read for months, it becomes easy to forget how much solace can come from a mid-quality but seductive (not in a horny way. but sometimes also in a horny way, lol) novel. Like, most of my reading these days is miserable 20th century theory or other academic/non-fiction writing related to our depressing capitalist hellscape & impending climate disaster, and The Mercies helped me remember that my roots lie in fiction. It also has me inspired to revisit a couple of historical fictions projects I have laying around, aND MAKE A WOMAN-EMPOWERMENT, ANTI-RACIST, QUEER AS HELL PERIOD FICTION PEICE THAT DOES NOT END IN COMPLETE GARBAGE! And in the meantime, I shall be revisiting the works of Sarah Waters, the only bad bitch I know of who writes queer historical fiction without relinquishing her characters solely to the suffering they experience ✌

If anyone has read this far and has any books/authors to recommend (wlw focused preferably, historical fiction or any genre as long as the story itself doesn’t rely on the tropes I touched on, recently published also preferably bc I have a long list of older books/authors but i don’t keep up with new releases like I should, & a lot of the ones I know are white & cis so PLEASE send reccs for more diverse stories/authors if you have them)

0 notes

Text

Media Criticism: An Introduction.

As I think is clear if you search the “long post” tag on my blog, and if you see my regular smaller posts complaining about parts of fandom, I tend to approach media far more from a position of writing meta and critique rather than writing fanfiction or fanart. This is fairly common, I think, in the part of fandom outside of what we might call Capital-F Fandom. Reviews, meta, technical analysis and examining work in terms of a particular social, psychological or political framework all come under what we might call Criticism, (here used not to simply mean being critical, but how we think about and understand media), but all of these have very different aims and methodology. Just as it is worth understanding the goal, standards and methods of a type of fiction or a historical account, it is worth understanding what different types of criticism are trying to do, how they try to do it, and how it fits into the overall conversation about media. Criticism does not have to be critical, as odd as that sounds, and I think that the way we tend to blur the lines between types of criticism often blurs our discussions both of media and of our communities.