#laurie sheck

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

And water lies plainly // Laurie Sheck

Then I came to an edge of very calm But couldn’t stay there. It was the washed greenblue mapmakers use to indicate Inlets and coves, softbroken contours where the land leaves off And water lies plainly, as if lamped by its own justice. I hardly know how to say how it was Though it spoke to me most kindly, Unlike a hard afterwards or the motions of forestalling. Now in evening light the far-off ridge carries marks of burning. The hills turn thundercolored, and my thoughts move toward them, rough skins Without their bodies. What is the part of us that feels it isn’t named, that doesn’t know How to respond to any name? That scarcely or not at all can lift its head Into the blue and so unfold there?

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

* * * *

from “Untitled" by Laurie Sheck:

Distance is the soul of the beautiful, she had read, and she imagines an unknown planet revolving in deep space, blue waves in tender exile from the land. Remorseless. Without witness. If she could go there she would possess nothing. How beautiful the earth might seem again from that distance. How possible love.

[Leopold Gursky]

Margaret Bourke-White, The Strip-Steppers, 1936

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

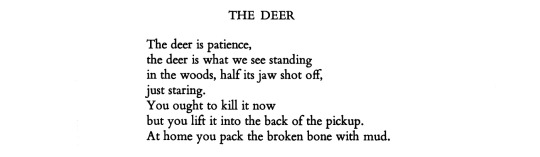

The deer, BY LAURIE SHECK

The deer is patience, the deer is what we see standing in the woods, half its jaw shot off, just staring. You ought to kill it now but you lift it into the back of the pickup. At home you pack the broken bone with mud.

Healing she moves toward you. Shy, she rubs her head against your leg. What I love in myself and others

is in the dream I have of this deer though she was real: she came out of the woods bleeding, she knew how to die but healed. The deer that walked one day back into the woods

is standing by a pond now, alert, in a wash of sunlight. How quietly she stands there as if there were no way to not belong in the worlds, as if it were this easy.

1 note

·

View note

Text

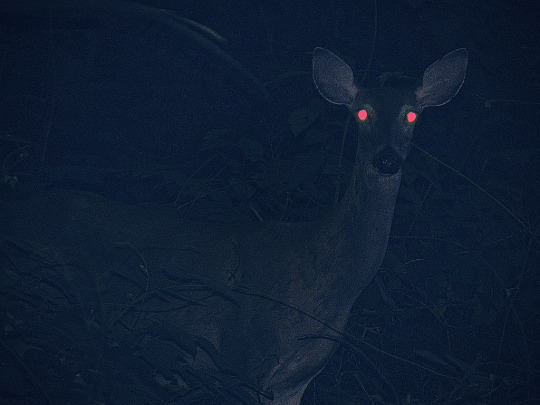

A WOUNDED DEER LEAPS HIGHEST

deer / headlight mirror, @/suitman // 13.01 lost and found, supernatural // a yiddish deer in the headlights, fabrice florin // deer in the headlights: low light awareness, teammisfits // deer survives arrow to the face, joshua rhett miller // 13.02 the rising son, supernatural // i found a baby deer alone in a field/garden/backyard – do they need help?, bcspca // 14.08 byzantium, supernatural // the deer, laurie sheck // why are new york hunters finding so many dead dear near water sources?, wgna-fm // a wounded deer leaps highest, emily dickinson

part two

#this is supposed to be one post but i have too many fucking images :sobs:#jack kline#supernatural#spn#spn edit#spn web weaving#spn parallels#deer motif#tw dead animal#tw animal injury#me and my silly dead animals in animal motif posts#my eorks

415 notes

·

View notes

Text

laurie sheck, the deer

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Where do you end and I begin?"

- Laurie Sheck, A monster's notes

#laurie sheck#prose#their mouths consumed mine#you and i have begun to blur#the cover was so cute i wanted to read her book but it is a giant tohu-bohu...

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

by Laurie Sheck

from Io At Night (Knopf, 1989)

as tweeted out by David Baker

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

As when red sky

The morning’s raw and wet.

There’s something delicate and fierce that comes damagingly out of the mind

When the body’s ill. I feel the invisible boundaries of my life strike into me

From regions I can’t see, as when red sky assails itself

After intervals of blue, whiteshine, dullish grey. I sense crimson strokes at the edges of things.

And have burnt inside myself so many words in a bonfire

Unseeable but real as dirt. The worst fault a thing can have is unreality.

Here is a window, here is a chair. The air swirls with severity and

Hazard. The chair is white-painted pine, peeling in places, and carved with a five-petalled flower.

Laurie Sheck

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

How possible love.

Distance is the soul of the beautiful, she had read, and she imagines an unknown planet revolving in deep space, blue waves in tender exile from the land. Remorseless. Without witness. If she could go there she would possess nothing. How beautiful the earth might seem again from that distance. How possible love.

~ Laurie Sheck, from “Nocture: Blue Waves” in The Penguin Anthology of Twentieth-century American Poetry (Penguin Books, 2011)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

I suppose you are weary now of remembering, that being mortal you want to convince yourself you belong to this earth, and are anchored to the earth by love.

You lie by the river. The sky is still. If you could you would watch the roots of the grasses, the roots of the wildflowers hunger through the soil, how they would cleave, as if forever, to what they cannot finally hold. The river's skin is cold and smooth. When the birds fly up, a sudden panic of black wings, you turn from the strange dream of their going.

I think of your wandering. White skin, white hooves, how you passed without touching what formerly you'd stopped to touch. The children picking flowers by the river seemed far away as stars. Allowed no rest, you moved within the stark cage of exile while you longed more than anything for hands. Did the earth grow beautiful then-

the lambs sleeping on the hillsides, the olive trees swaying where they stood? The world uttered its unstoppable fullness. And for the first time you saw it. You who watched it with longing from a distance unbridgeable as death.

To Io, Afterwards by Laurie Sheck

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“What Is the Difference,” Laurie Sheck

Stein asked what is the difference. She did not ask what is the sameness. Did not ask what like is. Or proximity. Resemblance. Did not ask what child of what patriarch what height what depth didn’t use a question mark but still wondered at the difference what mutinies it carries over what vast Arctic what far shore.

What is the difference between blind and bond. Between desk and red. Between capsize and sail. Between commodity and question. A lively thing, a fractured thing. To smile at the difference.

(Such gray clouds passing over. Thick, wet sky.)

What is the difference between mutiny and dust. Between noose and edge. Between brittle and obey.

Between shunned and stun. What is the difference.

As now, Mary Shelley’s monster flees to the north, his sack of books his lone companions.

10 notes

·

View notes

Quote

One of the beautiful things about writing is that it offers an inner life that’s disciplined and at the same time wild. Not in any way servile or submissive. It exists outside of institutional and other forms of authority even when being affected by them. On what almost feels like a cellular level, it’s anathema to labeling and enforced divisions.

THE RUMPUS MINI-INTERVIEW PROJECT #72: Laurie Sheck

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Laurie Sheck

#laurie sheck#this is really gorgeous as is the whole book#i'm not sure of some of her ends but.#there is no perfection in this vale of tears#poetry

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Laurie Sheck, “To lo, Afterwards”

“I keep remembering — I keep remembering. My heart has no pity on me.”

Henri Barbusse, The Inferno

“My memory spills over / my days”

Etel Adnan, The Spring Flowers Own

“It is not finally interesting to remember. The damage is not interesting.”

Louise Glück, Averno; “Blue Rotunda”

Emily Dickinson, “There is a pain — so utter”

“I asked the poet Tony Hoagland what he thought about fear. He said fear was the ghost of an experience: we fear the reoccurance of a pain we once felt, and in this way fear is like a hangover. The memory of our pain is a pain unto itself, and thus feeds our fear like a foyer with mirrors on both sides. And then he quotes Auden: “And ghosts must do again / What gives them pain.”

Mary Ruefle, Madness, Rack, and Honey

“For pain, forgetting is an island of flowers. Sweet smell of emptiness.”

Edmond Jabès, “Pre-Dialogue, II”

Anne Carson, “The Glass Essay”

“I wish I could remember. I wish memory were a more steady, more physical artifact. It’s just a breeze, or a scent barely detected and fading.”

Haven Kimmel, The Solace of Leaving Early

“My lack of memory is a denial of history. I lose myself and don’t remember how or when it happened.”

Dacia Maraini, “No Memory” (tr. Corrado Federici)

“I’d rather think that I’d temporarily died than that I kept on living and can’t remember a thing. I wasn’t a ghost, after all. I breathed, I ate, I walked.”

Wisława Szymborska, View with a Grain of Sand

“...she ought to be able to remember this, what it’s like, what’s coming. But who can remember pain, once it’s over? All that remains of it is a shadow, not in the mind even, in the flesh. Pain marks you, but too deep to see.”

Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale

“Listen. I am here to remember. I need to... remember. I have this grief and I don’t know why.”

Sarah Kane, Complete Plays; “Crave”

We forget all too soon the things we thought we could never forget. We forget the loves and the betrayals alike, forget what we whispered and what we screamed, forget who we were.

Joan Didion, Slouching Towards Bethlehem

“I’ve forgotten things, I’ve forgotten that I’ve forgotten them.”

Margaret Atwood, Cat’s Eye

“We forget and call it healing [...] we forgive everything but ourselves.”

Evan Knoll, “Blood Makes the Blade Holy”

“I’m tired of forgetting / everything. I want my details: why shouldn’t I have them?”

Alice Notley, Culture of One: Poems

John Ashbery, Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror”

“Sometimes I pray to remember, other times I pray to forget. It makes no difference.”

Barbara Kingsolver, The Poisonwood Bible

“If burnt, she said, I’ll turn to ash, and you wondered if she meant, Who will touch me as though they never did? She said, When I remember, my being shatters—”

Tarfia Faizullah, Seam

“It comes from that other life. You carry it with you, / you get used to it. You forget about it and it goes on talking and / singing and weeping all by itself.”

Frank X. Gaspar, Night of a Thousand Blossoms

“What I can’t remember is what I can’t feel —”

Virginia Woolf, Selected Diaries

“I recall with all my lives my reasons for forgetting.”

Alejandra Pizarnik, Extracting the Stone of Madness (tr. Yvette Siegert)

“It was a sort of doom I carried round — a sort of forced emotional amnesia.”

Martha Gelllhorn, Selected Letters

“But I must not think of the past. I must go on, destroying my memory. If only I felt some real energy in the present (something more than stoicism, good soldierliness), some hope for the future.”

Susan Sontag, As Consciousness is Harnessed to Flesh

Anna Akhmatova, Complete Poems; “The Sentence”

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Here the horn-scarred hunter and the tall stag

Have exchanged places. Each is dancing

Inside the other

standing deer, jane hirshfield // 14.17 game night, supernatural // deer shedding velvet looks painful but it's all part of antler life, rachael funnell // 14.19 jack in the box, supernatural // 14.20 moriah, supernatural // the deer, laurie sheck // 7.09 how to win friends and influence monsters, supernatural // "deer fabric," aase berg // strange deer deaths reported in pennsylvania, daniel e. schmidt // 15.01 back and to the future // meat-eating deer, outdoor life // 15.11 the gamblers, supernatural // two deer fighting, ming jun tan // 15.19 inherit the earth, supernatural // 'a birthday masque,' ted hughes

part one

#still annoyed i had to split this into two posts but anyways#jack kline#supernatural#spn#spn edit#spn web weaving#spn parallels#tw dead animal#tw slight gore#my eorks

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Isn't seeing a wounding and a caressing both?"

- Laurie Sheck, A monster's notes

36 notes

·

View notes