#late stalinist cinema

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

four late stalinist films, four red tinted cuts between scenes; a cinema industry drenched in blood

(1) Boris Barnet, {1950} Щедрое лето (Bountiful Summer) (2) Vladimir Petrov, {1951} Спортивная честь (Sporting Honour) (3) Nikolay Lebedev, {1952} Навстречу жизни (The Encounter of a Lifetime) (4) Vsevolod Pudovkin, {1953} Возвращение Василия Бортникова (The Return of Vasili Bortnikov)

#film#boris barnet#vladimir petrov#nikolay lebedev#vsevolod pudovkin#Щедрое лето#Спортивная честь#Навстречу жизни#Возвращение Василия Бортникова#bountiful summer#sporting honour#the encounter of a lifetime#the return of vasili bortnikov#1950#1951#1952#1953#red#late stalinist cinema#stalinist cinema#soviet cinema#soviet union#cccp#colour#1950s#feature length#male filmmakers

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 1968 Prague Spring: Separating Fact from Fiction

Much of the below is translated or adapted from an article written by the Russian historian and political scientist Nikolay Platoshkin. The article can be found here. You can find an identical blog post with hyperlinks to sources here.

Victors write history, and the historical narratives concerning the events of the Cold War are no different. The “Prague Spring” of 1968 is often shrouded in myths that serve the political interests of the hegemonic capitalist countries. The prevailing narrative typically presents the events as follows: economic and political reforms in Czechoslovakia, sparked by the election of the intrepid Alexander Dubček as First Secretary of the Communist Party in January 1968, were brutally suppressed by the invasion of Warsaw Pact troops on August 20-21. Naturally, the sympathies of the “free world,” particularly the United States, are portrayed as being aligned with the brave Czechoslovak reformers. However, the reality is more complex.

Genuine political and economic reforms in Czechoslovakia began long before the “Prague Spring,” influenced by developments in the Soviet Union during the early 1960s. As the Soviet Union under Khrushchev embarked on a period of de-Stalinization, it sparked a wave of reformist thinking across its satellite states. Under the leadership of Antonín Novotný, who had been President of Czechoslovakia and General Secretary of the Communist Party since 1953, the country initiated the rehabilitation of victims arrested during the Stalinist period. (The future leader of Czechoslovakia in the 1970s and 1980s, Gustáv Husák, was one of these, arrested in 1950 and released in 1963, a committed communist throughout.) Censorship was eased significantly, and Czechoslovak cinema, particularly the “New Wave” movement, gained recognition across Europe, with directors like Miloš Forman emerging internationally, as seen with his film Black Peter. A pivotal moment in this period was the adoption of a new economic policy in 1965, directly inspired by the Soviet Union’s Kosygin reforms. This policy aimed to decentralize economic planning, granting enterprises greater autonomy within a framework of business accounting.

The Soviet Union acted as the primary catalyst for reforms in Czechoslovakia, particularly after the new Soviet leadership under Leonid Brezhnev came to power in October 1964, which further accelerated reforms in Moscow and Prague. However, by late 1967, internal conflict within the Czechoslovak Communist Party intensified. Students from the Strahov dormitories in Prague launched a sizable protest over power outages, prompting Novotný to cease reforms and ban liberal journals and films. The widespread unpopularity of these moves led members of the party’s Central Committee to oust Novotný. This coalition of strange bedfellows included noted liberal reformers like Husák, Čestmír Císař, and Jozef Lenárt joining forces with conservatives like Vasil Biľak, Drahomír Kolder, and Jiří Hendrych. When Novotný sought a lifeline from Brezhnev in December 1967, Brezhnev refused, partly because he viewed Novotný as an ally of his Soviet rival, Alexei Kosygin.

During heated debates within the Czechoslovak Communist Party’s Central Committee, which began in October 1967, Novotný suggested Alexander Dubček as a compromise candidate for First Secretary, a proposal that Brezhnev accepted. Dubček, who had lived in the USSR from 1925 to 1938 (where he was a classmate of Brezhnev) and was seen as a reliable ally, was considered a weak political figure, making him acceptable to both liberal and conservative factions within the party. He was also of Slovak descent, which would appease Slovak nationalists who opposed the unitary state. On January 5, 1968, Dubček was narrowly elected First Secretary by just one vote. Brezhnev’s unexpected visit to Prague in December 1967 was interpreted by the U.S. as a reluctant intervention in the party’s internal struggles, given the lack of a clear alternative to Novotný. Far from the enterprising reformer portrayed in Western media, Dubček was initially meant to hold the party line, something that he promised to do, part of a pattern of deception and careerism.

In February 1968, the U.S. State Department agreed with the U.S. Embassy in Prague’s recommendation to refrain from showing goodwill toward Dubček’s regime, viewing it as an unstable coalition of right and left forces. The U.S. chose not to act despite holding significant leverage at the time, stemming from the U.S. Army’s seizure of Czechoslovakia’s gold reserves during the liberation of western Czechoslovakia in 1945. The gold had been taken by the Germans after their 1939 occupation. Despite repeated requests from the Czechoslovak government, the U.S. avoided returning the gold, citing various pretexts. In 1961, the U.S. agreed to return the gold in exchange for settling claims of American citizens affected by post-1948 nationalization in Czechoslovakia. Both sides initially agreed on a sum of around $10 million, but the U.S. later quadrupled the demand due to Washington’s displeasure over Czechoslovakia’s arms supplies to Vietnam. Additionally, the U.S. delayed granting Czechoslovakia most-favored-nation trade status, linking it to the unresolved gold issue. At the onset of the “Prague Spring,” U.S. policy was frosty toward Dubček.

On March 22, 1968, Antonín Novotný resigned as President, and General Ludvík Svoboda, a former commander of Czechoslovak forces on the Soviet-German front, succeeded him. The day before, Czechoslovak Ambassador to Washington, Karel Duda, told U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for European Affairs, Walter J. Stoessel, that the new leadership would likely seek better relations with the U.S. He dismissed the possibility of foreign interference in Czechoslovakia’s internal affairs, which the Americans interpreted as a reference to Moscow, but warned that internal conflict could escalate if it led to violence. This affirmed the view that Dubček’s regime was meant to stabilize Czechoslovakia, at least for the time being, not usher in a wave of reforms that would destabilize the country.

On February 25, Major General Jan Šejna, a Novotný supporter who led the Defense Ministry’s party organization, defected to the U.S. with his young mistress. Czechoslovakia demanded his extradition, accusing him of corruption and plotting a military coup for Novotný, but the U.S. refused. Despite being deemed a criminal by the Dubček government and once considered a hardliner, Šejna became a key CIA informant on Czechoslovakia and received political asylum. Given the choice between sheltering an individual it once considered a “Stalinist” for a military advantage or diplomatic measures meant to thaw relations with a Cold War adversary, the U.S. government eagerly pursued the former option.

The U.S. Ambassador to Czechoslovakia, Jacob Beam, held a low opinion of the new Dubček regime, viewing any push for liberalization as secondary to ousting Novotný, after which the government would likely seek stability. Nonetheless, Beam believed that the unfolding events in Czechoslovakia aligned with U.S. interests. On April 26, he recommended to Under Secretary of State for European Affairs, Charles E. Bohlen, a more flexible stance on the issue of Czechoslovakia’s gold reserves as a diplomatic gesture toward the new Prague leadership. Beam suggested returning “Nazi gold” to Czechoslovakia in exchange for an initial payment to compensate individuals whose wealth was expropriated during communist nationalization, with additional payments to follow. He also proposed using most-favored-nation trade status as a potential incentive, which would mean low tariffs or high import quotas for Czechoslovakia. Beam believed these steps could enhance U.S. influence within the communist world. However, Beam’s modest proposal was not supported. The State Department agreed only to express approval of Czechoslovakia’s liberalization. Due to Czechoslovakia’s role as the third-largest arms supplier to North Vietnam, direct financial or economic aid from the U.S. was deemed impossible.

During this period, a significant debate unfolded in Washington between “hawks” and “doves” in the U.S. leadership. President Lyndon B. Johnson, who had decided not to seek re-election in October 1968, and Secretary of State Dean Rusk prioritized détente with the USSR. They believed this thaw in relations could help end the Vietnam War with Soviet assistance. Johnson even planned a potential visit to Moscow in October 1968, becoming the first U.S. President to do so. Johnson was concerned that excessive liberalization in Czechoslovakia might jeopardize the improving U.S.-Soviet relations.

In contrast, the “hawk” faction, led by Deputy Secretary of State for Political Affairs Walt Rostow, saw an opportunity to weaken the USSR globally by attempting to pull Czechoslovakia out of the Warsaw Pact. Rostow believed this could distract the Soviets from Vietnam and possibly allow the U.S. to end the war on more favorable terms. Rostow is remembered as one of the biggest cheerleaders for the Vietnam War, claiming that strategic bombing of North Vietnam alone would be sufficient to win the war. This was based on Rostow’s belief that there was no genuine support for communism in South Vietnam and that ending the war was as simple as destroying North Vietnam’s infrastructure.

On May 10, 1968, Rostow sent Rusk a memorandum titled “Soviet Threats to Czechoslovakia,” interpreting Warsaw Pact maneuvers in Poland as a sign of Soviet hesitation and urging Johnson to summon the Soviet Ambassador to demand an explanation. Rostow also proposed creating a special high-level NATO group to monitor the situation in Czechoslovakia and prepare a response plan. However, both Rusk and Johnson rejected Rostow’s alarmist stance.

The U.S. Embassy in West Germany shared a cautious view for different reasons. Unlike the 1956 Hungarian crisis, the Embassy noted in a telegram on May 10 that moving American troops closer to or across the Czech border to counter a Soviet attack was conceivable due to the shared border between Czechoslovakia and West Germany. However, the West German government, including the Social Democrats, strongly opposed any U.S. military action from West German territory. The West German Deputy Foreign Minister even urged the U.S. Ambassador to moderate anti-Czechoslovak propaganda from Radio Free Europe in Munich and RIAS in West Berlin, leading the U.S. Ambassador to West Germany, George McGhee, to consider joint actions with West Germany against Czechoslovakia unrealistic.

On May 11, Secretary of State Dean Rusk initiated a continuous exchange of opinions between NATO countries concerning the situation in Czechoslovakia. However, in a telegram to the U.S. mission to NATO, he recommended holding off on actions that might be perceived as NATO showing “unusual concern” about Czechoslovakia.

Despite this, the U.S. remained unwilling to address the pressing bilateral issues with Czechoslovakia. On May 28, Jiří Hájek, the new Czechoslovak Foreign Minister and a reformer, expressed frustration to the U.S. ambassador that bilateral relations had not improved since 1962 and had even regressed in some respects. Hájek reiterated demands for the return of Czechoslovakia’s gold reserves, pointing out that the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia had occurred with the West’s, including the U.S.’s, acquiescence. Ambassador Beam was unable to provide a concrete response but reported to the State Department that Prague was likely using the gold issue to bolster its authority within the communist bloc and to curb any growing pro-American sentiments within the country.

On June 13, the CIA provided a memorandum titled “Czechoslovakia: Dubcek’s Pause” to the top U.S. leadership. The memo assessed that the crisis in Czechoslovakia, both internal and external, had lost its immediacy, leading to a “pause.” The Soviet Union had been reassured by Dubček’s firm commitment to keeping the reform process under Communist Party control. In return, the Czechs were granted some autonomy in domestic matters by the USSR. The CIA noted that the Soviets were keen to avoid military intervention in Czechoslovakia, due to concerns that the country might leave the Warsaw Pact, given that Czechoslovakia had the largest army per capita within the Pact, totaling 230,000 soldiers.

Despite Moscow’s objections to the anti-Soviet rhetoric in the Czechoslovak media, the CIA reported that this rhetoric had “reached astonishing proportions” in recent weeks. The media blamed the USSR not only for the Stalinist repression of the early 1950s but also for the current economic difficulties in Czechoslovakia. However, it was precisely cheap raw materials from the USSR that were able to provide Czechoslovakia with high rates of economic growth and an improvement in the standard of living of the population. For all its embrace of market reforms, the Czechoslovak economy did not grow out of its moribund status, as goods produced in the country simply were not competitive enough. Inflation soon followed, leading to cuts to social services, which only led to greater public dissent.

The CIA concluded that due to the compromise between Prague and Moscow, “Moscow decided not to use force, at least for the time being.” Interestingly, the CIA noted that Dubček himself might benefit from this situation, as his perceived indecisiveness in implementing reforms could be attributed to Soviet pressure. U.S. intelligence, citing Czech sources, also reported growing disagreements within the Soviet leadership over Czechoslovakia. Leonid Brezhnev, who had placed Dubček in power, was under pressure as Dubček’s policies were increasingly seen as anti-Soviet. This situation could potentially be exploited by Brezhnev’s opponents within the Soviet leadership, including Kosygin.

U.S. intelligence, correctly assessing the situation, believed that Dubček was merely stalling by agreeing to Brezhnev’s terms and promising to maintain socialism in Czechoslovakia. They anticipated that at the upcoming Communist Party congress in September 1968, reformist views would be formally adopted as the party’s official program, revealing to the Soviets that they had been misled. The CIA also assessed that Dubček lacked firm convictions of his own and was influenced by the reformers Oldřich Černík and Zdeněk Mlynář, who were expected to play a crucial role after the congress. The CIA concluded that there was a significant likelihood of renewed tension between Prague and Moscow. Although Soviet leaders, or at least most of them, preferred to avoid sharp and costly military action, they might resort to threatening Czech borders if Dubček’s control appeared to be collapsing or if Czech policies became “counterrevolutionary” from Moscow’s perspective.

By this time, the CIA was heavily influenced by its primary “expert” on Czechoslovakia, General Šejna, who was pursuing his own agenda to discredit Dubček. On July 24, the CIA reported that the crisis in Czechoslovakia had subsided, according to Šejna, who believed that the Czechoslovaks would likely capitulate to Soviet demands and reverse the reforms. Šejna also suggested that such a rollback would not provoke significant public protests, as neither workers nor Slovaks were actively engaged in the liberalization process. The CIA noted that the “Prague Spring” was largely driven by intellectuals and parts of the party apparatus without improving the material conditions of the general population. Furthermore, anti-Soviet sentiment in the Czech press did not resonate with Slovakia. The CIA’s internal notes reflected concerns that Šejna might be underestimating the national factor, noting that military and police forces, being “conservative and pro-Soviet,” could quickly suppress any potential demonstrations against the rollback of reforms.

The CIA memo highlighted that the Soviets were facing substantial pressure from conservative forces within Czechoslovakia, as well as from the leaders of Poland and East Germany, who demanded more stringent control over the situation in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. Šejna believed that while the Soviets favored using political influence, they were prepared to use military force if necessary, which would likely involve a rapid advance of Soviet troops into Czechoslovakia. The CIA accurately assessed that Moscow was becoming aware that Dubček and the “liberals” were not fulfilling their promises to keep Czechoslovakia within the Soviet sphere of influence, specifically the Warsaw Pact.

By July 1968, the State Department was already considering raising the Czechoslovak issue at the United Nations, potentially as a protest against the slow withdrawal of Soviet troops following the end of the Warsaw Pact “Šumava” maneuvers on June 30. However, the U.S. was reluctant to take direct action at the U.N., preferring instead that the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, or potentially Romania and Yugoslavia, initiate the discussion.

On July 14-15, the leaders of the Soviet Union, East Germany, Hungary, Poland, and Bulgaria met in Warsaw to discuss the events taking place in Czechoslovakia. On the heels of the publication of liberal manifesto “The Two Thousand Words,” the Warsaw Pact leaders feared that anti-communist forces were exploiting the liberalization to promote disorder. Although they stated their common desire not to interfere in Czechoslovak affairs, they shared anxieties that reactionary forces were preparing for counterrevolution:

The reactionary forces were given the opportunity, in public, to publish their political platform under the title “Two Thousand Words,” which contains an open call for a struggle against the communist party and against the constitutional system, as well as a call for strikes and chaos. This appeal is a serious threat to the party, the National Front, and the socialist state. It is an attempt to foment anarchy. The declaration is, in its essence, the organizational-political platform of counterrevolution.

On July 20, 1968, Rostow issued another memorandum to the Secretary of State, pressing for active measures to deter the USSR from acting against Czechoslovakia. Rostow acknowledged that Czechoslovakia was within the Soviet sphere of influence and that its departure from Moscow’s control would severely undermine Soviet positions globally, including in Vietnam and the Middle East. The memorandum proposed establishing a special NATO group to develop a unified response plan for potential crises involving the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, suggesting that this move would reinvigorate the alliance itself. Rostow, also serving as special assistant to the president, requested from the US military leadership, via the Supreme Allied Commander Europe of NATO, information on NATO forces available for a possible intervention in Czechoslovakia. On July 23, the response indicated that a potential intervention could involve one US brigade, two French divisions, and two German divisions. The Joint Chiefs of Staff limited the U.S. contribution to one brigade due to the lengthy mobilization time required for a larger force.

Thus, the US was seriously contemplating a NATO intervention in Czechoslovakia a month before the Warsaw Pact troops entered the country. On July 22, the Soviet Ambassador to the US, Anatoly Dobrynin, was summoned to the State Department, where Secretary of State Rusk lodged a de facto protest against Soviet media claims of NATO, Pentagon, and CIA subversive activities against Czechoslovakia. By July 24, President Johnson convened a meeting with the entire US political and military leadership, including the Secretary of State, Secretary of Defense, and Director of the CIA. At this meeting, Rostow revised his earlier position, expressing doubts that the Soviets would take military action against Czechoslovakia. Rusk also declared that the “Czech crisis” had passed.

From July 25 to August 1, the top leadership of the USSR and the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic convened in Čierna nad Tisou in southeastern Slovakia—a historic meeting, as it marked the only occasion when the entire Soviet leadership traveled abroad simultaneously. During these discussions, a compromise appeared to be reached. Dubček, in the presence of the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, agreed to halt anti-Soviet rhetoric in the Czechoslovak media, bolster the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ leadership, and remove several anti-Soviet figures from key government positions, including the head of Czechoslovak television, Jiří Pelikán. In return, Brezhnev promised to end the Soviet media’s critiques of Czechoslovak policies.

In the meantime, a group of conservative communist politicians, including Vasil Biľak and Drahomír Kolder who had supported Dubček’s rise to power, authored a “letter of invitation” to Brezhnev and the Soviet government to intervene in Czechoslovakia. They saw the writing on the wall: the Dubček government was neither trustworthy nor competent, and if the situation was allowed to continue, Czechoslovakia was likely to degenerate into chaos, with ordinary people suffering the most. The capitalist West would not help the people but only exploit the situation according to their political interests. The only viable choice was to ask the Soviet Union to restore order and remove the Dubček government. Brezhnev would later cite this letter as a major justification for the later Warsaw Pact invasion.

The US Embassy in Prague, in a dispatch dated August 4, reported that while the meeting in Čierna might have temporarily eased tensions, Dubček would likely struggle to honor his commitments without undermining his domestic support. The embassy suggested that the State Department publicly commend the Čierna meeting’s results for resolving the immediate political crisis in Czechoslovakia. However, despite the agreement, anti-Soviet articles continued to appear in Czechoslovak newspapers post-Čierna, and Dubček did not fully meet his promises. Instead of the bold reformist hero, Dubček should be seen as an opportunist who told others what they wanted to hear at the time so long as it helped him stay in power. Instead of confrontation, he nominally chose compromise at Čierna.

On August 10, during a meeting with President Johnson and Republican presidential candidate Nixon, CIA Director Helms remarked that while the immediate severity of the Czechoslovak crisis had diminished, it was not fully resolved. He noted that the Czechoslovaks were increasingly seeking to reduce their participation in the Warsaw Pact. The Soviets wanted to avoid this at all costs, but had no honest leader to deal with.

On August 13, Brezhnev had an extensive telephone conversation with Dubček, which likely prompted the decision to introduce Warsaw Pact troops into the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. During this call, Brezhnev implored Dubček to fulfill the commitments made at Čierna or at least specify when these would be met. In typical fashion, Dubček avoided providing a clear answer and revealed his intention to resign from his top party position at the upcoming Communist Party Congress in September. Moscow feared that the Czechoslovak party leadership might disintegrate imminently, prompting the decision to deploy troops to support Dubček and mitigate pressure from the liberals. Had Moscow simply wished to remove Dubček, it could have waited for the September Congress.

On August 19, Rostow conveyed to Dobrynin over dinner that the United States viewed the Soviet decisions at Čierna as “wise.” The Americans aimed to avoid exacerbating the situation in Czechoslovakia and were hopeful that the situation would stabilize following Čierna. On August 20, Dobrynin met with President Johnson. The President, in good spirits, discussed various topics, including Kosygin’s health and his own lack of a haircut, before addressing the main issue. Dobrynin informed Johnson of the Soviet leadership’s decision to deploy troops into Czechoslovakia, citing a threat to European peace and stating that the intervention was at the Czechoslovak government’s request. The message emphasized that the action was not intended to undermine American interests and assured the continuation of détente in Soviet-American relations. Johnson thanked Dobrynin and promised a response after consulting with Secretary of State Rusk. The conversation concluded amicably, with no condemnation of the Soviet action from the American side. Dobrynin was surprised by Johnson’s lack of immediate reaction, noting that the President seemed to underappreciate the gravity of the situation.

On August 20, Soviet forces were ordered to commence Operation Danube, marking the beginning of the troop deployment into Czechoslovakia. By approximately 11 p.m., Warsaw Pact troops from the USSR, Poland, Hungary, and Bulgaria began crossing the Czechoslovak border. Soviet airborne units landed at Prague’s Ruzyne Airport at 2:00 a.m. on August 21. The general directive for Soviet units in the event of encountering NATO forces was to halt and refrain from engaging.

Slovaks widely welcomed Soviet troops, joyfully hoping for a return of social guarantees and urban development, saying that “the Slovaks are not with Prague.” This sentiment reflected a deep-seated dissatisfaction with the central government’s policies, which many Slovaks saw as favoring Prague and the Czechs. The arrival of Soviet forces was seen by some as a chance to regain the social stability and economic progress that had been characteristic of earlier communist rule. Many Slovaks believed that aligning with the Soviet Union could secure better living standards, greater investment in infrastructure, and a reassertion of traditional socialist values that they felt were being eroded by the reformist agenda.

On August 20, President Johnson convened an emergency meeting of the National Security Council (NSC) in Washington. Both Secretary of State Rusk and Defense Secretary Clark Clifford expressed significant surprise at the Soviet decision to deploy troops. CIA Director Helms correctly identified the motivation behind the Soviet actions: Dubček’s failure to meet the commitments made in Čierna. Helms noted, “They (i.e., the USSR) wanted the Czechs to quiet the press. The Czechs did not do that.” Johnson labeled the troop deployment as aggression and inquired about possible responses from the United States. Rusk suggested that the U.S. could support Czechoslovakia at the United Nations if the Czechoslovaks raised the issue of the Soviet invasion there. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Earle Wheeler, stated that the United States lacked the strength for any forceful retaliation: “We do not have the forces to do it.” Vice President Hubert Humphrey concluded the discussion by emphasizing the need for restraint, noting, “All you can do is snort and talk.”

By August 26 most high-ranking Czechoslovak officials, including Dubček, signed the “Moscow Protocols” that required they pledge themselves to Marxism-Leninism, proletarian internationalism, and renew the struggle against bourgeois ideology. Notably, the Soviets did not simply install pro-Moscow conservatives as their puppets, unlike the U.S. and CIA, who regularly overthrew governments around the world during the Cold War to install dictators loyal to Washington. Instead, the new government included reformers like Gustáv Husák and Jozef Lenárt who favored not suppression but “normalization,” the peaceful return to the pre-Dubček period. Although Czechoslovakia was not permitted to go down the road to chaos or counterrevolution, many of the same individuals who held power before the Soviet intervention remained in power afterwards, unlike in cases of U.S. military interventions.

It is also worth stressing the degree to which the Soviet leadership went to negotiate with Czechoslovak leaders, first with Brezhnev’s personal intervention in late 1967, the Čierna meetings in late July 1968, and the negotiations over the subsequent Moscow Protocols. Clearly, the Soviet Union was willing to go to great diplomatic lengths to keep the country inside the Warsaw Pact. Compare this to the 2000s, when Czech protests over U.S. missiles and radar stations due to NATO membership prompted only shrugs from Washington. Moreover, the U.S. used a large number of Czech troops to shore up its illegal war in Iraq, something the Soviet Union never did during its bloody occupation of Afghanistan.

As we have seen, the U.S. government viewed the Dubček regime with caution, not optimism, considering it a loose coalition of various political forces and a transitional phenomenon. The “Prague Spring” lacked support from both the working class and the Slovak region of Czechoslovakia. Instead of using diplomacy, the United States contemplated the possibility of military intervention in Czechoslovakia by several NATO divisions. The USSR’s approach to Czechoslovakia was deemed prudent by the United States, and the compromise reached in Čierna was regarded as a “wise decision.” The CIA (correctly) assessed the introduction of Warsaw Pact troops on August 20-21, 1968, as a response to Dubček’s failure to keep his word and implement the Čierna agreements.

#socialism#communism#marxism#politics#prague spring#czechoslovakia#czech#slovakia#slovak#Čierna#Dubček#Husák#NATO#Soviet Union#Warsaw Pact#Soviet

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maybe in the end we should reconcile ourselves to the fact that the film essay is not a territory and that it is, like fiction and documentary, one of the polarities between which films operate. An energy more than a genre. And it might well be cinema’s last irreducible. You find it, arguably, at the origins of cinema with A Corner in Wheat (1909), but a few years later [D. W.] Griffith laments the fact that cinema has turned away from filming “the rustle of the wind in the branches of the trees.” Twenty years and ten days that shook the world pass, and you see it triumphant in [Dziga] Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929); but a few trials later you feel the Stalinist boot heavier by the day on its neck in Enthusiasm (1931) and Three Songs of Lenin (1934). You think it is done and over with when the oppressiveness of commercial cinema rules, but it reappears under the guise of [Jean-Marie] Straub and [Danièle] Huillet’s Too Early, Too Late (1981), [Chris] Marker’s Sans Soleil (1983), or [Jean-Luc] Godard’s Puissance de la parole (1988). As soon as you wonder if it is after all just an über-Western mode, it becomes Asian with [Nagisa] Oshima’s The Man Who Left His Will on Film (1977), [Kidlak] Tahimik’s The Perfumed Nightmare (1977), or [Apichatpong] Weerasethakul’s Mysterious Object at Noon (2000). And when you want to keep it there it bounces back to the Middle East or South America … This is, of course, a fairy tale hurriedly told. One fact remains though: however dire the circumstance, the essayistic energy remains alive in the margins, an Id that haunts cinema. It is never more alive than when the times are more repressive and the dominant aesthetics occupy more squarely the middle of the road. Jean-Pierre Gorin, "Proposal for a Tussle."

1 note

·

View note

Text

Second Waltz – Dmitri Shostakovich (from Suite No. 2 for Jazz Orchestra) for piano solo

Second Waltz – Dmitri Shostakovich (from Suite No. 2 for Jazz Orchestra) for piano solo (sheet music)

https://dai.ly/x8i2lnj

Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich (25 September 1906 – 9 August 1975), was a Soviet composer. His production covers all genres: opera, musical comedy, miniature symphony for piano, concert music, cantata, string quartet and music for the cinema. A prolific author, he wrote a total of 147 opus numbers, many of them corresponding to works that today are among the most performed and recorded pages of the repertoire. However, despite being considered, along with Prokofiev, the most representative composer of the former Soviet Union, his career was not easy: prizes and decorations -among which were the State and Lenin Prizes and the distinction of Artist of the Pueblo-, alternated with continuous persecutions and condemnations by the same regime that laureated him, under the accusation of making excessively modern and anti-popular music. All this left its mark on the style of his latest compositions, characterized by a bitter and gloomy tone, as well as a rawness that contrasts with the jovial and carefree spirit of the first ones.

Born into a family in which culture had an important place, Shostakovich received his first musical lessons from his mother, a professional pianist, at what can be considered a relatively late age, nine years old. Given his great progress, in 1919 he entered the Leningrad Conservatory, where he had Aleksandr Glazunov as his main teacher. Fatherless since 1922, Shostakovich continued his studies while, to support his family, he played in various movie theaters as an accompanying pianist. The 1926 premiere of his surprising Symphony no. 1, written on the occasion of his graduation from the conservatory, immediately drew the attention of the musical world to him. Immediately subsequent works, such as the opera The Nose or the ballet The Golden Age, only confirmed the talent of a young composer especially gifted for satire. Shostakovich's upward career suffered an unexpected setback with the 1934 premiere of his second opera, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk: enthusiastically received by the public, both in Leningrad and in its subsequent staging in Moscow, it was withdrawn from the bill after the appearance of a Criticism in the official newspaper Pravda, entitled Chaos instead of music, in which the composer was accused of having written a 'howling concert', alien to the assumptions of socialist music, which should be clearly and easily accessible. Thus began a long and contradictory relationship with the Stalinist regime: while in the West he was considered the official Soviet composer, in his own country Shostakovich had to suffer interference from his cultural authorities, despite which, and despite his apparent acceptance of the precepts of socialist realism, he always managed to maintain his creative independence. The premieres of the classical Symphony no. 5 and, above all, the patriotic Symphony no. 7 «Leningrad», a symbol of the struggle of the Russian people against the Nazi invader, rehabilitated a composer who in 1948 once again saw the execution of his works prohibited under the stigma of formalism. After Stalin's death in 1953, Shostakovich's music became more personal, resulting in a long series of scores presided over by the idea of death. This is the case of the last three symphonies and his string quartets, a genre that the composer turned into the ideal medium in which to express his worries and fears in a private way, without the need to resort to masks or disguises. His music, especially that of these later years, has considerably influenced that of his younger compatriots, such as Alfred Schnittke or Edison Denisov, among others. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

NO SHIT SHERLOCK!

What fucking took you so long!

The story: ALSO- spoiler warning

Midway through a screening of Joker this weekend at a Chicago theater, I leaned over to a friend seated next to me and whispered: “Is this the same movie that everyone has been talking about?”

I asked because what I was witnessing on-screen bore little resemblance to the ode to angry, young, white, “incel” men that I had heard so much about in media coverage of Joker leading up to its release. Instead, we got a fairly straightforward condemnation of American austerity: how it leaves the vulnerable to suffer without the resources they need, and the horrific consequences for the rest of society that can result.

This message is so blunt that even I, a Marxist and philistine, found its message a bit too clobbering. How mainstream commentators have missed it and drawn the exact opposite conclusion is baffling.

Arthur Fleck, the protagonist and eventual Joker, is a poor, young, white, mentally ill man who works as a clown and seems to enjoy it. In the film’s opening scene, he is beaten up by a rowdy group of teenagers, some of whom appear to be teens of color..

Watching this opening, I thought, here it is: in the very first scene, teenagers running wild on the streets of New York City, a classic rightwing trope in American cinema depicting a society (and its racialized underclass, in particular) that is out of control. We’ll soon be told it needs to be reined in by some old-fashioned law and order and cracking of skulls.

Yet in the locker room of the clown agency, when a coworker calls the teens “animals” and “savages”, Arthur explicitly rejects dehumanizing the teens. “They’re just kids,” he responds. Bruises visible on his body – a body for which Joaquin Phoenix lost 52 pounds ahead of filming, with a disturbingly protruding spine and ribs, that is physically ravaged by the austerity-racked society Arthur lives in, wasting away in front of our eyes – he defends his assailants and rejects his coworker’s racist epithets.

Since critics depicted this as a film for the far right, whose overtly racist views are well-known, I expected the depictions of characters of color to be bigoted. But interestingly, almost all of the violence he eventually metes out as he sinks deeper and deeper into a full breakdown – save for the movie’s final scene, at which point Joker’s nihilistic brutality has fully blossomed, now wanton and indiscriminate – is against white men, many of them wealthy.

A passing interaction with a neighbor, a single black mother who lives on his floor, leads to a disturbing and delusional romantic obsession with her . This culminates in a tense scene in which – on the verge of a full breakdown and after we realize the previous scenes of the two of them on a date and sitting at the hospital bedside of Arthur’s mother were completely imagined by him – he walks into her open apartment.

The viewer expects an act of violence against her, perhaps even a horrific scene of sexual assault, by the lonely man who wants the beautiful woman but can’t have her. In other words, the ultimate incel revenge fantasy. Instead, startled, she asks him to leave. He does.

Likewise, in a scene whose political message was so blunt that it could have appeared in a mid-century Stalinist propaganda film, his social worker and counselor – another black woman – with whom he has a tense but clearly significant relationship, is forced to tell him that due to recent budget cuts, their office will be shutting down. Arthur asks her where he’s going to get his medication; she has no answer for him.

“They don’t give a shit about people like you, Arthur,” she tells him, referring to those who cut the budget. “And they don’t give a shit about people like me either.”

The black, female public-sector worker is telling the white, male public-service user that their interests are intertwined against the wealthy billionaire class and their political lackeys who are slashing public services. Across racial and gender boundaries, the two have a common class enemy.

You can’t get much less subtle, or much more diametrically opposed to the right’s worldview, than this.

It is those budget cuts that drive Arthur deeper into madness. Similar attempted cuts likely drove sanitation workers to strike, resulting in the piled-up garbage constantly visible on Gotham’s streets. These are clear allusions to New York City’s 1975 fiscal crisis and the austerity it produced, which soon spread to the rest of the country.

Elites’ condescending responses to the widespread suffering make things worse. Billionaire Thomas Wayne condemns Arthur’s murder of his three employees (representing young, arrogant, rich Wall Street types) on the subway by calling the average person seething in the streets “clowns”. Don’t they know that he wants to help them, the ultra-rich mayoral candidate asks. He is irritated he even has to explain this. His comments merely stoke the already burning fires of resentment, with Wayne’s obliviousness at their misery rubbing salt in the wounds of average Gotham residents and driving them to the streets to protest Wayne and elites like him in clown masks.

And, of course, when Arthur sneaks into a high-class theatre and confronts Wayne about what Arthur has been led to believe by his ailing mother – that Wayne, her former employer, is Arthur’s father – the genteel billionaire, dressed in a full tuxedo, literally punches Arthur in the face. Again, political subtlety is not this film’s stock and trade. How could reviewers miss this?

What Arthur – and scores of others like him in Gotham and our own society – needs is a fully-funded Medicare for All or NHS-style health system that includes robust mental health services that provide him with the counseling services and medication that can save him (and others around him) from his unceasingly “negative thoughts” and violent impulses.

He needs public programs that can provide a warm, encouraging environment for his creative impulses, allowing him to perform standup comedy or perform as a clown without becoming a laughingstock on national television or getting canned by an uncaring boss. He needs wages for his care work for his infirm mother or a robust elder care system that can respectfully take her under its care. He needs high-quality housing he can afford.

Arthur has more than his share of problems, but a few of them would have been solved, or at least adequately and humanely managed, in a society whose budgets were oriented more towards people like him than Wayne. But he does not live in that society, and neither do we. Instead of public services and dignity, he gets that most American of consolation prizes: a gun, and the sense of respect that, while ultimately hollow, has long eluded him.

Joker’s ending is bleak and one whose general thrust we knew going into the film: in addition to the three Wall Street types, an old mother, a coworker, a talkshow host and a billionaire couple have been murdered in cold blood; rioters in clown masks are running wild in the streets, cheering Joker on the hood of a cop car. In the final scene, Arthur is again speaking to a social worker, but now in handcuffs in an asylum. But it’s too late to reach him, because he’s no longer Arthur – he’s the Joker, and the Joker has no qualms about killing her, too.

Rosa Luxemburg once famously framed the choice for our future as that of socialism or barbarism. Joker is a portrait of a society that has chosen barbarism. No one wants to see violence erupt in such a situation, but we shouldn’t be surprised when it does.

In the real world, we aren’t yet at that breaking point. And unlike Gotham, we have alternate paths on offer – represented best by the Vermont senator Bernie Sanders, whose presidential campaign speaks to that roiling anger but channels it into humane and egalitarian directions. If we don’t take it, and that anger continues to find a home in reactionary outlets, the barbarities we see in Joker might start looking horrifyingly familiar.

322 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monday, 17th September 2018 – Day 1, Kiev

Finding myself in Kiev for a 2-workshop and meeting session with the rest of the 12-strong team I am part of, the London contingent (two of us) were on the ground and in our hotel about 3 hours ahead of everyone else, so with the dispensation of our lovely manager, we didn’t have anything to do until the others showed up. With that in mind, and arriving on a gloriously sunny afternoon, I persuaded my colleague that we really, really needed to go out and do some sightseeing. It was too good an opportunity to waste. Based in the Park Inn hotel, right next to the Olympic stadium which is now home to Dynamo Kiev, we were well situated to walk to the main attractions of the city centre.

Armed with the Lonely Planet guidebook to Ukraine, and a free Kiev map from reception, I now knew where we should aim for, and so cameras in hand, we walked up towards Taras Shevchenko Park initially, along Velyka Vasylkivska Street and over to Lva Tolstoho Street, admiring the variety of architectural styles which ranged from Stalinist flats to turn of the 19th/20th Century blocks with fabulous decorative features, some of them more “foreign” looking than others.

We also encountered the first of many, many terraces which seem to be attached to every restaurant no matter how basic or how grand. Later some of us would come to think these might not be such a good idea, for a variety of reasons, not least the prevalence of both cigarette smokers, and for that matter, shisha pipe users, mostly young women, who seemed not to care how far and wide the awful perfumed fumes spread from the damn things!

We also found the first of many, many murals, usually beautifully done, and covering the entire end walls of numerous buildings around the city. These apparently sprang up everywhere after the 2014 revolution and the plan is to have at least 200 of these instances of street art. There’s even a map of all of them.

This was also roughly the time we realised that crossing the road can be something of an adventure in Kiev. The traffic is heavy, and despite the crossing lights counting down how long you have to cross, and making it very clear that you are allowed to cross, car drivers still try and come round the corners and carry on regardless. You have to adopt a very determined demeanour and trust you’ll survive! Fortunately for the viability of the local population the really big road junctions have underpasses, complete with doors which I assume are especially necessary in the winter to stop the tunnels filling up with snow. The result is a number of underground spaces, full of ad hoc shops, selling all sorts of stuff you never wanted, or in fact never knew existed.

We survived the crossing to the park, and found quite a few things to amuse us. Temperatures were in the high 20s, so pretty much anyone with nothing better to do was perched on the benches in the cool shade of the trees. And the thing is, the benches themselves came in all manner of shapes that can only be described as playful, with no one bench the same as its neighbour. There were fountains, and flowerbeds full of marigolds, and statues of course, including this rather splendid – if rather gloomy – one of Mr. Shevchenko, the multi-talented national poet himself (which probably beats Austrian nymphs on plinths into a cocked hat).

It’s a very busy place, with all sorts going on, and with cafes and coffee shops and pretty much the entire student body of the university across the road sitting talking, dancing, playing music and generally living life outside. Even late in the evening it remained busy (as we discovered later in the week). We continued up Volodymyrska Street, passing the rather fabulous Taras Shevchenko Ukrainian National Opera House on the way.

The Golden Gates of Kyiv (Золоті ворота) were the main gates of the 11th century fortifications of Kyiv, the capital of Kievan Rus’, and were built between 1017 and 1024 (6545 in the Byzantine calendar) at the same time as The Cathedral of Saint Sophia, which was where I was keen to get us, was built. The whole thing was demolished in the middle ages, and was completely rebuilt by the Soviets in 1982, presumably entirely from their imaginations, because there are no images of the original gates available. The whole rebuilding was extremely controversial, and I did wonder why people were visiting it apart from out of curiosity. Hopefully, they don’t think they’re seeing an historical structure.

It was shortly after this that things started to get weird. Across the square from the gates we found this.

It’s part of the same initiative as the murals. It’s all part of the “ArtUnitedUs” iniative, which is the biggest urban street art project in the world. The hedgehog is a monument to a cartoon, “Hedgehog in Fog”, which was produced in 1975, and it’s the work of the Kyiv Landscape Initiative. The claim is that in 2003 a survey of 140 cinema critics and animators declared it the best cartoon in the history of animation. How true this is, I have no idea, but it seems reasonable. And it certainly wasn’t the only odd art work we encountered. There was a cat made out of white plastic forks (by Constantin Skretutsky)…

And also, in the grounds of Saint Sophia’s cathedral, a squishy piece of work (by Beata Korn) that has a sign asking visitors not to cuddle it. You can see why because it’s oddly irresistible. This is part of the art-project “3D.Public Art” and if you can read Ukrainian, then you’ll know a lot more about it than I do!

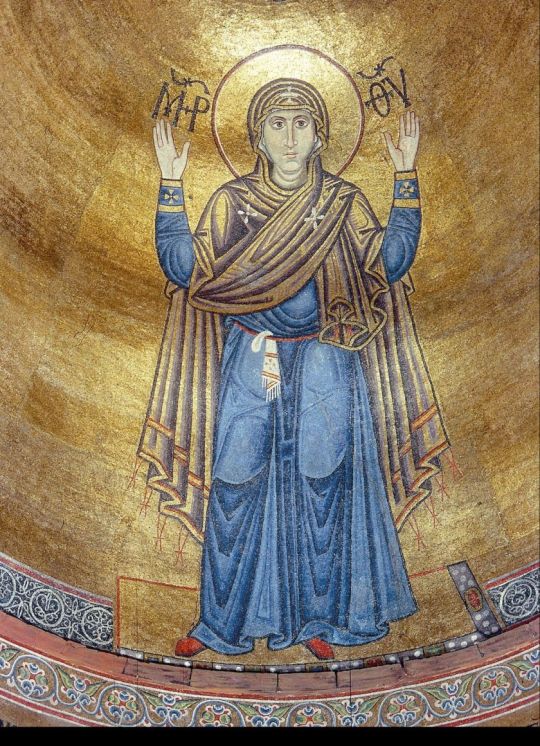

We had enough time to investigate the cathedral, but not the rest of the “territory”, so handing over a very small sum of money, we went in. I wasn’t allowed to take photos, which was a shame, but understandable. To give you a taste, I’ve found this on the Wikipedia page for the cathedral.

The building work started somewhere around 1011, and it was founded by the Grand Prince of Kievan Rus’, Vladimir the Great, and building has 5 naves, 5 apses, and 13 cupolas, which is not normal for Byzantine churches. it has two levels of balconies on three sides and it’s full of the most stunning 11th century mosaics and frescoes. I can only imagine what it must have looked like when the mosaics were new, with gold everywhere, and paintings on pretty much every surface. The Kievan rulers were buried here, and the grave of Yaroslav I the Wise is still there.

It has suffered substantial damage more than once, and the hands of Andrei Bogolyubsky of Vladimir-Suzdal in 1169, then the Mongolian Tatars in 1240. By the time that Poland and Ukraine were trying to unite the Catholic and orthodox churches it had pretty much fallen into ruin. Repair work was finally undertaken in 1633 by the Italian architect Octaviano Mancini in what is known as Ukrainian Baroque, at least on the outside, while still preserving the interior art.

Its fate was in the balance again in the 1920s, when the Soviet government wanted to destroy the building (a fate that did befall St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery on the other side of the massive square from Saint Sophia’s). It ended up being re-classified as an architectural and historical museum, a function that it still fulfills now. In a side area there is currently a display of some of the art that was saved from Saint Michael’s prior to its demolition. There was also an interesting work made out of thousands of Ukrainian pysanky eggs, highly decorated Easter eggs. The work, a depiction of the Virgin Mary in the cathedral, is by Oksana Mas, and is made out of something in the region of 15,000 eggs, all different. It’s really impressive, and it takes the eye a moment or two to realise that it is actually made of individually painted eggs.

Back outside we admired the bell tower, which, like those we saw in Finland, stands separate from the main body of the church. It’s beautiful, and apparently affords some fine views over Kiev. We didn’t think we had time, though. I took a few photographs, and bought a guidebook before we left to head back to the hotel to meet up with our colleagues.

The park was still buzzing, and the roads were as lethal as ever. I did spot another of the rather fine murals as we were walking along, and if/when we get back (there’s a suggestion of a repeat visit in Spring) I want to see how many of the 200 works I can find.

We were back at the hotel by 18:00, after a couple of hours of nosing around, and I know my impression of the city was pretty positive already, though I was slightly startled by the presence of a bagpiper outside the Metro station opposite the hotel. It wasn’t that he was playing an instrument most people assume to be Scottish, because I know enough to know that it’s a very common instrument worldwide (after all, it’s really just a bag with hollow pipes), it’s just that I’ve tended to regard the playing of bagpipes as an act of war! The Ukrainian version is called a volynka, and originates in the Carpathians.

It remained to be seen what else we might find, as we were due to be taken on a short tour by our Ukrainian colleagues at 18:30. Sadly, the Danes had fallen victim to a taxi driver who had misunderstood his instructions, and they were now on a misguided tour of the city as he tried to find his way through the rush hour gridlock back to the Park Inn from the Holiday Inn. By the time they finally made it in the door, it was dark outside, and the place we were headed for was close to closing. At least the two of us had seen something of the city.

Travel 2018 – Day 1, Kiev Monday, 17th September 2018 - Day 1, Kiev Finding myself in Kiev for a 2-workshop and meeting session with the rest of the 12-strong team I am part of, the London contingent (two of us) were on the ground and in our hotel about 3 hours ahead of everyone else, so with the dispensation of our lovely manager, we didn't have anything to do until the others showed up.

#2018#Arts#Cathedral of Saint Michael#Cathedral of Saint Sophia#Cathedrals#Churches#Europe#History#Kiev#Museums#Sightseeing#Taras Schevchenko#Taras Schevchenko Park#Travel#Ukraine

1 note

·

View note

Text

1930s Mexico and Sergei Eisenstein’s Unfinished Mexican Film

In 1930, Russian avant-garde film director Sergei Eisenstein traveled to Mexico to start a film project known as ¡Que viva México! — but production was eventually abandoned and the film was never finished.

Upon Charlie Chaplin’s recommendation, Sergei Eisenstein connected with writer Upton Sinclair, who helped fund the project. Eisenstein shot dozens of hours of footage for what was planned to be a multi-chapter film about the history of Mexico. Funds from the Mexican Film Trust — a production company established by Sinclair, his wife, and other investors — were soon exhausted, and Eisenstein’s chances of finishing the film himself further diminished as his re-entry visa to the United States expired and he was unable to secure an extension to his permission to remain away from the Soviet Union. Much of the footage was brought back to the U.S. by the producers, and Eisenstein’s film remained incomplete.

***

Sergei Eisenstein compared Mexico and his 'Mexican picture' to a serape, the indigenous multi-coloured woven blanket:

So striped and violently contrasting are the cultures in Mexico running next to each other and at the same time being centuries away. No plot, no whole story could run through this serape without being false, artificial. And we took the contrasting independent adjacence of its violent colors as the motif for constructing our film: six episodes ... held together by the unity of the weave — a rhythmic and musical construction and an unrolling of the Mexican spirit.

Eisenstein’s Mexican film does not exist; we have only its yarn to be weft, many miles of film that Eisenstein could not access. He couldn’t take it with him back to the USSR since he had signed his rights away to Upton Sinclair’s wife, who had presented him with a contract that he — eager to leave Hollywood for Mexico — signed in Pasadena on November 24, 1930:

WHEREAS, Eisenstein wishes to go to Mexico and direct the making of a picture tentatively entitled Mexican picture, and whereas Mrs. Sinclair wishes to finance the production of and own said picture […] In consideration of the above agreement by Eisenstein, and in full faith that he will carry out his promise to direct the making of the best picture in Mexico of which he as an artist is capable, Mary Craig Sinclair agrees that she will put up the sum of not less than Twenty-five Thousand dollars ($25,000) […]

Mexico in the Early 1930s

The multi-ethnic Mexico of 1930–32 was archaic and innovative, welded in the buzz of post-revolutionary society and culture where artists such as Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros lived and worked. Later they were joined by sculptor Isamu Noguchi, photographers Paul Strand and Henri Cartier-Bresson, and several European surrealists. It was in Mexico City where André Breton and Diego Rivera met with Soviet exile Trotsky to write a manifesto on revolutionary art. However, in 1940 Trotsky was attacked and murdered in Coyoacán, only a few houses away from Rivera and Kahlo’s home. The fact that his assassination was supported by Stalinist artist Siqueiros marked the end of the era of innocence even before Mexico entered the war.

It was Siqueiros who a decade earlier had collaborated with Eisenstein in Taxco where the painter 'extended Eisenstein's montage principles to mural painting'. Mexico has an exceptionally strong tradition of muralism, used in the 20th century to communicate through images with people who could not read. This is not only parallel to Russian visual culture, which relied on icons, posters, and cheap woodcuts or prints, but also film as a medium of propaganda.

While Eisenstein was disappointed by Hollywood, he fell in love with Mexico. It was a country that at the time showed parallels to the USSR, which he had left in 1929. The Soviet film director arrived in the creative post-Revolutionary era, when not only Mexico’s indigenous roots had been revealed but a new, hybrid culture was emerging. This hybridity found its expression in Mexico as meeting place of cultures and diasporic communities, as polyglot as Eisenstein, who spoke several languages fluently. American progressive artists, who revered Diego Rivera, came to Mexico to join the Mexican Muralist Movement.

The American adventure seems to have cost Eisenstein his reputation at home and his health. Ordered to return to the USSR by Stalin, he spent time in 1933 in the Kislovodsk spa in the Northern Caucasus to recover from the depression following the film being aborted.

Versions and Reconstructions of Eisenstein’s Footage by Other Filmmakers

On his journey to Mexico, Eisenstein was accompanied by two people: his cinematographer Edward Tissé and his assistant Grigory Alexandrov. During my last visit to Russia, I asked a film professor from St. Petersburg why Eisenstein’s Mexican film was never finished, and received the answer that it was not only the Americans who were at fault, but also Eisenstein’s companion, Grigory Alexandrov, who might have informed the USSR that Sergei was not going home.

If this is true, it was indeed unfortunate that Alexandrov accompanied Eisenstein — not only because he seems to have accelerated his journey home, leading to the film never being finished, but also due to a competition that arose between the two in Hollywood. When Eisenstein in 1930 received the opportunity to make a film in Mexico with the help of Upton Sinclair, Alexandrov was not ready to leave since 'Hollywood producers had found Grigory Alexandrov a person whom they thought capable of producing the kind of pictures they wanted' — unlike Eisenstein, who was subjected to anti-Semitic attitudes, having been attacked in one letter 'as a 'Jewish Bolshevik' who the 'successful Jews of Paramount' had imported to make 'propaganda films''.

Alexandrov profited from the journey to America, having studied Hollywood sound stages. While Eisenstein back in the USSR could not make a film for nearly a decade, Alexandrov became one of the most proficient imitators of the Hollywood film musical, directing a string of successful comedies, advancing to Stalin’s favourite in this popular genre.

It was Alexandrov who, in the late 1970s, long after Eisenstein’s death, edited the best known version of the Mexico material, titled ¡Que viva México!. This is the version on which most of the critical literature about the Mexican material is based, such as the harsh critique of the film as producing 'gendered constructs' and 'fetish-objects' by scholars of Mexican cinema, Laura Podalsky and Joanne Hershfield. The criticism is accurate, at least when it comes to Alexandrov’s version of the Mexican material, with its 1970s Soviet soundtrack, exoticizing the material and turning it into a B musical.

There were other attempts at partial releases, versions, and (re)constructions, such as Sol Lesser’s 1934 shorts (Death Day, Thunder Over Mexico, and Eisenstein in Mexico, produced in the USA at the behest of the Sinclairs). Three other major versions of the material were prepared: Marie Seton edited the version Time in the Sun (1939, Anita Brenner, credited as Breener, was involved, as well) based on communications with the director, a four-hour version by film historian Jay Leyda incorporated all of the documentary footage shot on the side, and Oleg Kovalov created Mexican Fantasy in 1998.

What is there to be said about these many versions of Mexican material? They form an interesting corpus in themselves. This re-editing of the footage by multiple artists has added meaning and fresh context to the original work. We can look at this from the theoretical perspective of Prague structuralism which was shaped in the 1930s. It separates 'artefact' (the object itself) and 'aesthetic object' (the object that has been assigned value by the viewer). The idea is that only the aesthetic reception by someone besides the artist turns the object into a work of art. Re-editing or re-creating a film can be considered part of this act of aesthetic reception.

Films are not finished works of art. Even in films which are edited according to the will of director and/or producer, the editing is one of the components in film which stays changeable. In the early days of film, exhibitors freely recut foreign films — famously, Eisenstein learnt the craft of this type of montage from Esfir Shub. Politically motivated re-edits or excisions, in post-1945 USSR sometimes called 'reconstructions', all testify to film being not unchangeable and eternal, but rather a truly protean creature by definition, censored according to the current governing ideology or revived every time a new generation is ready to 'read' and edit it again. If that is the case, then Eisenstein’s Mexican cinema project is an ever-changing cinematic serape, one that enriches and perpetuates meaning via its unfinished — and yet continuing — condition.

0 notes

Photo

With its history and design, you’re never more than a few blocks from greenspace in Berlin. The city contains forested areas and lakes large enough to hide the city, and is fully encompassed by a parkway, but its best parks all lie within its inner ring. No two locals have the same favorite park, as they run the gamut from hip Mauerpark, to charming Volkspark Friedrichshain. Park am Gleisdreickpark and Tempelhofer Feld attract picnickers and athletes alike, while Preussenpark is home to gourmands every weekend. From their ruins to their memorials, each of these parks makes the city’s history plain to see.

Mauerpark

Once covered by the Berlin Wall, Mauerpark (“Wall Park”) now hosts the city’s most popular flea market every Sunday. Located at the end of the Berlin Wall memorial strip, the market attracts some of the city’s most popular street food stands, while the park’s long grassy strip is home to a wide variety of buskers and picnicking locals. The park’s most unusual attraction is an amphitheater built into the side of a hill, famous for its karaoke sessions (starting at 3), with crowds of hundreds singing along (mostly in key).

Ten minutes down the street is the Kulturbrauerei (“Culture Brewery”), which hosts a quieter street food market every Sunday. An example of industrial architecture at its best, the courtyard of this massive former brewery is more upscale and attracts neighboring families. The compound includes an art cinema, galleries, theaters, restaurants, clubs, and museum devoted to everyday life in East Germany. In December, it hosts one of the city’s most popular Christmas markets.

Preussenpark

Every weekend, Preussenpark (“Prussian Park”) becomes the city’s most beloved food destination, known as Thaiwiese (“Thai Lawn”) or Thaipark. If you visit, you’ll find a park with dozens of women sitting on stools beneath umbrellas, preparing and selling food and drinks at low prices, as locals nap and chat between courses. This impromptu market takes place between the flea market above the Fehrbelliner Platz subway station, and the playground next to the Konstanzer Strasse subway station.

Treptower Park

Running along the Spree River, Treptower Park is popular with families out for a stroll, and the home port for many of the city’s tour boats. If you follow the river upstream, you’ll soon come to the Island of Youth, a small island connected by a beautiful bridge that arches across the river, with towers on either side. The island has an outdoor cafe and bar that hosts an open-air cinema in the summer. Further on lies a forest that hides the Spreepark, an abandoned amusement park. Even if you can’t catch one of the occasional tours of Spreepark, you can still peek through the fence of glimpses of its rides, dinosaur statues, and a Ferris wheel visible from far beyond the park.

The park’s main attraction is the largest of the city’s three Soviet war memorials. Built in the late 40s on the grounds of a mass grave for Soviet soldiers, the memorial grounds are a masterpiece of Stalinist architecture. After passing through large gates, kneeling statues, and red granite portals, visitors come to an area lined by trees and stone sarcophagi with carvings of quotes from Stalin, and reliefs of military scenes. The focus of the memorial is a 40-foot statue of a Soviet soldier holding a rescued German child on one hand, and a sword in the other. The soldier stands atop a crushed swastika, and the statue atop a hill overlooking the park and the city itself. While normally quiet, this park is the center of Victory Day celebrations held on May 9th by the local Russian community.

Volkspark Friedrichshain

The city’s third-largest park, the Friedrichshain People’s Park was a showcase for East Berlin. A stream with waterfalls popular with children leads to a lake next to a Peace Bell from Hiroshima. The park is home to other memorials, the largest of which commemorate volunteers who fought against fascism in Poland and Spain. Beneath the park’s two hills lie WWII flak towers and air-raid shelters. Too sturdy to be fully demolished after the war, they were instead covered by debris from nearby ruins. On hot days, families bring their children to the Märchenbrunnen, “Fairytale Fountains” that depict animals and characters from various legends.

Tempelhofer Feld

Built on former Knights Templar parade grounds, Tempelhof Airport was Europe’s second-oldest airport. After closing in 2008, it was resurrected as one of the city’s most popular parks. Tours are available of the terminal and hangers, which resemble an eagle with outstretched wings from the air, and which formed one of the world’s largest buildings upon their completion in the 1930s. Tempelhof was the center of the Berlin Airlift, as commemorated by an American DC-3 “Raisin Bomber.” The tarmac and runways provide ample room for any sports involving wheels, while grassy areas host many barbecues and picnics. One runway is devoted to wind sports, such as kiteboarding, while there is a community garden area and often a circus in summer, near a beer garden and a public pool. The airport also contains the world’s only field for “Boffer,” a sport involving foam weapons based on a post-apocalyptic cult film from the 80s.

Viktoriapark

Located on the edge of the Bergmannkiez neighborhood, which survived WWII largely intact, Viktoriapark is built around a steep hill. This elevation is crowned by a monument commemorating the Wars of (German) Liberation from Napoleon, which provides one of the city’s best views. From the memorial, an artificial waterfall runs to the base of the hill. The park is also home to the city’s last remaining vineyard, although Berlin’s homegrown wine is the subject of many jokes, and bottles of wine are not sold by the park’s hobbyist vintners.

Park am Gleisdreieck

Starting next to Potsdamer Platz, Gleisdreieck Park covers the grounds of what was once one of the city’s main rail yards, which served a railroad station that ended up on the other side of the Berlin Wall. The space feels cool and futuristic, with trains passing by overhead and emerging from a tunnel running to the main train station. Abandoned sections of track run between copses, playgrounds, volleyball courts, and gardens maintained by Balkan refugees who came to Berlin in the 90s. Dozens of disused railroad bridges cross a street that bisects the park, giving an idea of former rail yard’s size. Built on the grounds of a former train maintenance area, the German Museum of Technology, near the park’s center, is worth a visit. If you have a bike, we recommend following the park to its southern tip, then taking a new bike path along the active tracks past Südkreuz station to the Schöneberger Südgelände. This nature park encompasses another abandoned rail yard, but has kept its tracks intact. Südgelände also features tunnels, steam engines, and a roundhouse turned into an art venue.

What’s your favorite Berlin park?

If you’ve been to Berlin already which was your favorite? If you’re planning a Berlin, a Park for Every Personality appeared first on Jayway Travel.

0 notes

Text

A Kim Jong-Il Production The Extraordinary True Story Of A Kidnapped Filmmaker, His Star Actress, And A Young Dictator’s Rise To Power by Paul Fischer

A Kim Jong-Il Production The Extraordinary True Story Of A Kidnapped Filmmaker, His Star Actress, And A Young Dictator’s Rise To Power by Paul Fischer tells the story of the North Korean regime’s abduction of a South Korean director and his actress wife in the late 1970s. Director Shin Sang-Ok and his wife Chio Eun-Hee were abducted on the orders of Kim Jon-Il himself, the rising power and future dictator of the totalitarian Stalinist state that is North Korea.

Shin and Chio were already established and successful names in the South Korean movie industry. Chio had stared in a number of her husband’s films by 1978 when she was kidnaped after being lured by North Korean agents to Hong Kong. Shin was abducted when he went to Hong Kong in search of Chio.

While Shin and Chio’s careers were on the rise, north of the Demilitarized Zone that cuts Korea in two, Kim Jong-Il, son of North Korea’s founding tyrant Kim Il-Sung, was looking to advance his own career in the field of absolute control. Jong-Il was a huge film buff, being the dictator’s son allowed him access to all of the banned foreign movies ordinary North Koreans would be shot for watching, and apparently he wanted to make a few films in a foreign style. For that Jong-Il wanted Shin and Chio.

This story may sound strange or even absurd on the surface, but Fischer does an excellent job of relating the thoughts and emotions that Chio and Shin went through as they were cut off from their children, starved, imprisoned, monitored every waking and sleeping moment, stuffed with juche dogma, forced to sing the praises of their kidnappers, made to work for the regime, and all the while knowing that the outside world either thought they are dead or willing defectors. Choi’s longing for her children, who she did not even have a chance to say goodbye to is particularly heart wrenching.

Fischer also does well to set the stage for his characters, so to speak. He provides important background and biographical information on not only Chio and Shin, but on Jong-Il and North Korea too. A state as insane and absurd as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea is certainly in need of an introduction. Fischer aptly describes North Korea has one giant stage production put on by Kim Il-Sung and Kim Jong-Il both figuratively and literally.

As is basically a prerequisite when I discuss a book about North Korea there are some pretty dark and disturbing sections. Shin’s imprisonment in a North Korean jail and the description of life for an average North Korean come to mind.

The text was easy to understand and follow. You do not need to know anything about the history of cinema in either North or South Korea, or anything about movie making as a matter of fact. This book can also serve as a first foray into the subject of North Korea, as Fischer gives ample background information on the Stalinist state.

A Kim Jong-Il Production is a well written look at a disturbing, fascinating, and often times unbelievable part of history.

#a kim jong il production#paul fischer#a kim jong il production the extraordinary true story of a kidnapped filmmaker his star actress and a young dictator's rise to power#shin sang-ok#chio eun-hee#kim jong il#kim il sung#north korea#south korea#movies#filmmaking#abduction#propaganda#communism#korean history

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scott Walker, 1943-2019

At the time of sitting down to write this piece, it has been 90 minutes since I read the news of Scott Walker’s death. His label, 4AD, posted a beautifully written, poignant statement on Twitter which was 4 minutes old by the time I read it. I am genuinely heartbroken.

Scott Walker meant a lot to me, but it is at times such as these that I try to reconcile my emotions with knowing that they are projected towards an idea of a person, somebody who I would never meet, or see on stage, and rarely had any idea of the kind of person they were. So why do I feel so upset? Music is a universal force at the very essence of the human experience; it connects people, it helps us to understand certain situations through vicarious means, it soundtracks moments in our lives and it is perhaps the most immediate and therefore the most evocative of popular art forms. Music is feeling, and music allows us to feel. And Scott Walker’s voice and music made me feel more than most other artists.

Born Noel Scott Engel in America, his career spanned the mid-1960s pop pin-up mania of The Walker Brothers, to a run of four (and a half) astonishing solo albums in the later years of that decade which saw diminishing returns in terms of sales. He then quit writing his own material in the 1970s as self-doubt and alcoholism took hold before he returned to work with The Walker Brothers in 1975 for three more albums. From the 1980s onwards, Scott released an increasingly astonishing body of work at frustratingly large intervals but with each album from 1984’s Climate of Hunter through to 2014’s collaboration with Sunn O))), Soused, there was a move away from pop song structures to avant-garde experimentalism. He also wrote the score for the films Pola X, The Childhood of a Leader and Vox Lux, sang on a Bat for Lashes track, produced Pulp’s We Love Life album and composed a 24-minute commissioned piece of experimental neo-classical music for CandoCo, an inclusive (disabled and non-disabled) dance company with the music performed by the London Sinfonietta. No doubt the news this evening will skip over most of this and just go for the ‘disappeared from public view’ angle in his biography as it’s easier that way.

Scott’s output, as a solo artist and as a member of The Walker Brothers, spans not just decades but ideals. In the late 1950s, he was championed by Eddie Fisher (Carrie’s dad) and appeared on his TV show a few times and recorded a number of fairly forgettable tracks. The first Walker Brothers single (the agonisingly titled ‘Pretty Girls Everywhere’) can be dismissed in many ways as pop fluff; fodder for the masses with another bunch of pretty boys singing a superfluous song for a teenybopper audience who would soon move on to the next manufactured act as instructed to by the record labels. John Walker sang on this first track; it is not essential listening. And then they released ‘Love Her’ with Scott’s beautiful baritone front and centre, and the template was set for the melancholic tone which would permeate through Scott’s output for the next fifty (FIFTY!) years.

The lyrical themes of The Walker Brothers centred largely on love, mostly on the pains of unrequited or lost love, but as Scott moved into his solo career there was a schism which saw him embrace more challenging and ‘arty’ areas. One song was dedicated to the Neo-Stalinist Regime, another centred on the narrative in Ingmar Bergman’s masterpiece of existentialist cinema The Seventh Seal, while controversial Italian neo-realist film director Pier Paolo Pasolini, Clara Petacci (Mussolini’s mistress) and Jesse Presley (Elvis’s stillborn twin brother) were all topics of focus in his songs. It is really hard to distil his body of work into 1000 words or so, you just need to dip into his back catalogue yourself and see for yourself. And don’t believe the naysayers who say his early '70s covers work holds nothing of value as there are some gems hidden amongst the undeniably dire work whose purpose was solely to claw some money back for his record label.

In the brilliant documentary 30th Century Man, the man himself states in rare interview footage that he didn’t ‘disappear into the wilderness’ as many people saw it, he just didn’t have anything to say. This is a theme which comes up when you watch what little footage there is of him in existence talking about his career, that he didn’t feel the need to write unless there was a compulsion to do so. I suspect the steady stream of royalty cheques from The Walker Brothers probably helped this a little. There was a feeling that his output was becoming more and more personal to him, and increasingly satisfying as a result. In 2018 he stated in The Guardian that his album with Sunn O))) was “pretty perfect” and it is hard to disagree with him on this.