#late cenozoic

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Our nucleic acid recovery techinques found a great deal of homo sapiens DNA incorporated into the fossils, particularly the ones containing high levels of resin, leading to the theory that these dinosaurs preyed on the once-dominant primates.

Late Cenozoic [Explained]

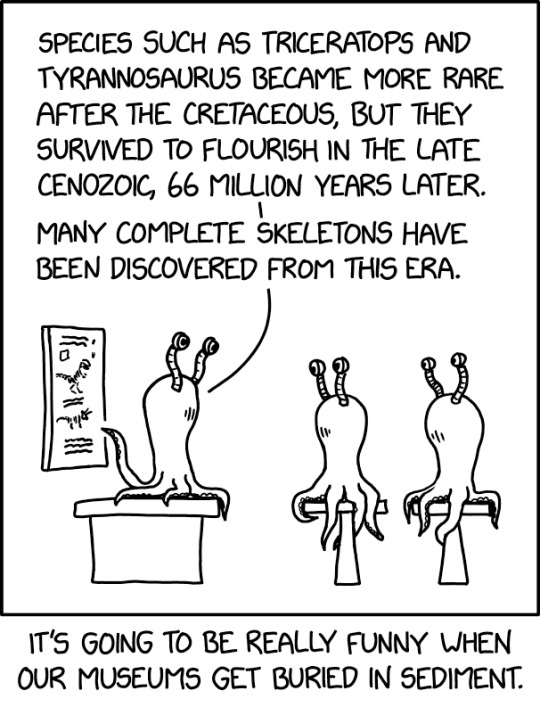

Transcript Under the Cut

[Three squid-like aliens in a classroom; one alien stands in front of a board covered with minute text and a drawing of a T-Rex skeleton. Two aliens sit on stools watching the teacher alien. The teacher alien on the left is on a raised platform and points at the board with one tentacle.] Left alien: Species such as triceratops and tyrannosaurus became more rare after the Cretaceous, but they survived to flourish in the late Cenozoic, 66 million years later. Left alien: Many complete skeletons have been discovered from this era.

[Caption below the panel:] It's going to be really funny when our museums get buried in sediment.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

friends :)

#paleontology#mesozoic#late cretaceous#pleistocene#gryposaurus#akainacephalus#ankylosaurus#hagryphus giganteus#hagryphus#deinosuchus#bison#ice age bison#giant bison#mammoth#mamuthus#columbian mammoth#fossils#dinosaurs#dinosaur#dinosaur fossils#natural history#earth history#earth science#natural science#mesozoic fossils#cretaceous period#cretaceous fossils#cenozoic

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

The giant entelodont Daeodon shoshonensis was the “Top Hog” (or more accurately the “Top Land-Hippo”) of the Late Oligocene-Early Miocene of North America 29-15 million years ago

Beachside Bonanza: As the sun sets down over the shores of the Western interior Seaway, a flock of Nyctosaurus sp. prey upon a creche of Protostega hatchlings as they make a mad dash for the waves. Fortunately the baby turtles still have numbers on their side, as the pterosaurs will depart once they see more and more Protostega hatchlings sliding down the sandy slopes of the beach from the nest where they came from.

#paleoart#paleontography#paleontology#cretaceous period#miocene#daeodon#nyctosaurus#protostega#cenozoic life#cenozoic#mesozoic#late cretaceous#early miocene

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

The white dinosaur and her babies are called Nanuqsaurus, which means “polar bear lizard” because they were the top predator of late Cretaceous Artic. The dinosaur in the mother’s mouth is called Ornithomimus, meaning “bird mimic.”

#artists on tumblr#digital aritst#dinosaurs#dinosaur art#paleoart#paleontology#cenozoic#cretaceous period#late cretaceous#nanuqsaurus#prehistoric planet#ibispaintx art#ibispaintx#mother#mother’s day#flowers#tulips

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Free Speculative Evolution Prompt Saturday: K-PG Lightning Round!

66 million years ago, a mass extinction event wiped out 75% of life on earth, wiping out the dinosaurs, and leading to the age of mammals. And 66 million years later a sapient species of hairless primates discovers dinosaur bones and imagines what would happen if they never went extinct.

For those who don't want to follow this trope but still like the idea of alerting the cenozoic through the end K-PG this is your post.

Part One: Changing Difficulties

One of the easiest ways of changing the Cenozoic through the end Cretaceous is by lowering or increasing the percentage of life being wiped out from the end Cretaceous. For example, if the percentage was lowered by 60 or less you could have other mammals like multituberculates and Dryolestida, you could even include some non avian dinosaurs survive to the Cenozoic. now for the opposite side of the scale you could go full on Sephiroth and go 80 to END PERMIAN levels of extinction, wiping off the birds, most of the placental mammals, and all gymnosperm plants! leaving a world much weirder then where we were.

Part 2: Location Location Location

We all know about the butterfly effect right? one small or insignificant change would change everything, from a butterfly fluttering it's wings, to the exact location of a asteroid hitting earth. while it will wipe out 75% of life on earth, but the brunt of the death would depend on where the asteroid would hit, and no I'm not just talking about the amount of animals that would die near the impact but the rest of ecosystems of the hemisphere. for example, if the asteroid hit somewhere off the coast of Chile or northern Argentina more southern hemisphere animals would die then the northern hemisphere animals.

Part 3: The Cause

let's say you wanted to be creative and don't want a asteroid wiping out the dinosaurs, you might wanna have the earth go through a ice age in the K-PG, or maybe have the deccan traps be more destructive to earth, or maybe some alien space bats to cherry pick the animals you don't like and kill them. Be creative.

#speculative biology#speculative zoology#speculative evolution#spec bio#alternate timeline#alternate universe#dinosaurs#cretaceous#late cretaceous#cenozoic#K-PG

1 note

·

View note

Text

Spectember/Spectober 2024 #07: Mole Dino

Today's spec creature is a combination of a couple of submissions – James P. Quick asked for "a post-K/Pg relict dinosaur from pre-glaciation Antarctica", and an anonymous asked for "a subterranean (like, say, Talpa or Spalax) burrowing dinosaur":

At the time of the K/Pg mass extinction some of the small ornithopods that inhabited Late Cretaceous Antarctica had been developing increasingly complex burrowing behavior and a more generalist omnivorous diet than most other ornithischians – and, along with their ability to endure the long dark cold polar winters, this was juuust about enough for them to survive while the rest of their non-avian cohorts vanished.

They were very briefly a fairly successful disaster taxon in the devastated polar forests, but they were quickly displaced by other diversifying survivors and never really got another ecological foothold to regain anything close to the non-avian dinosaurs' former glory.

Instead the little ornithopods specialized even further for burrowing, spending more and more of their lives underground to avoid the increasing competition and predation from mammals and birds.

Now, well into the Cenozoic at the dawning of the Miocene, Cthonireliqua quicki is the very last representative of the non-avian dinosaurs. Small and stocky and mole-like, just 15cm long (~8"), it has muscular forelimbs with large shovel-like claws, a keratinous shield on its head, and a thick bristly tail where large fat reserves are stored.

Its eyes are almost completely absent, only vestigial remnants present under the skin of its face, and it navigates its extensive burrows using sensitive whisker-like filaments and its keen senses of hearing and smell. Still omnivorous like its ancestors, it feeds on whatever it comes across while tunneling – mainly worms, insects, smaller vertebrates, roots, and tubers.

Unfortunately for Cthonireliqua, and the rest of its Antarctic ecosystem, time is running out. Over the last few million years Antarctica's climate has been steadily cooling and drying, the continent has become fully isolated, and the Antarctic Circumpolar Current has formed. Glaciation is well underway in the continental interior, and the once-lush forests are shrinking away and being replaced with tundra.

Soon all evidence of these dinosaurs' existence will be buried under the ice.

#spectember#spectober#spectember 2024#speculative evolution#ornithopod#ornithischian#dinosaur#art#science illustration

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fossil Novembirb 5: It's Getting Hot In Here

Sandcoleus by @drawingwithdinosaurs

Global warming is nothing new for the planet, and even in the Cenozoic we've had our share of rapid warming events - the most notable one being the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM). This event, taking place 56 million years ago, was the result of rapid carbon release from the North Atlantic Igneous Province - aka, a volcano exploded, released a bunch of greenhouse gases, and suddenly global temperatures jumped somewhere between 4 and 10 degrees Celsius (depending on location) in a very short period of time - sound familiar?

Given the obvious parallels to the current day, this event has been studied extensively, though only in a few spheres. We know that plants changed dramatically, with broad leafed plants spreading around the world and turning it into a global tropical forest, even at the polls - leading to interesting adaptations towards the strange light cycles at high latitudes. The world was wetter, and greener, and the change lead to the evolution of new herbivory methods in insects. Mammals got smaller, spread everywhere, and diversified. A mass extinction occurred in the oceans, with microorganisms seeing a larger drop in diversity than during the end-Cretaceous extinction. More calcified algae flourished in the more acidic waters.

But what happened to birds?

Anachronornis by @otussketching

Turns out, we're not quite sure. Bird fossils before the event are rare, and after are so diverged and varied that it's difficult to know what happened because of the event, and what happened before and just didn't fossilize. Luckily, scientists (... me) are on the case! And there were a few ecosystems that straddle the time around the event, such as the one for this post: the Willwood Formation.

This ecosystem in Wyoming takes place over the late Paleocene through the early Eocene, covering the entire PETM period. And while it showcases many different aspects of this transition, we're of course here for the birds! Not only was there Gastornis, because it was a ubiquitous presence in the Northern Hemisphere following the PETM, there were also many other weird early kinds of birds, all across the avian family tree.

Paracathartes by @drawingwithdinosaurs

Sandcoleus is one of the more notable tree birds from this ecosystem, being a relative of living mousebirds but in North America (rather than Africa, where they are found today). In fact, lots of different tree birds were present, indicating that the current dominance of Passeriformes - so called "perching birds" - was not always the case. In fact, Paracathartes was also present - our first Palaeognath, an early Lithornithid! - and it also may have been able to perch in the trees, and certainly seems to have been a decent flier.

There were also Geranoidids like Palaeophasianus and Paragrus, which were once thought of as pheasant-like and crane-like respectively, but may now actually be Palaeognaths - and some of the earliest known flightless ones to boot! That said, said, other than being long legged flightless birds, we know little about their ecologies - they may have been herbivorous, and as tropical forest dwellers, could have had similar lifestyles to the living cassowary.

Primoptynx by @otussketching

And, of course, there was also Anachronornis, the half-screamer-half-duck thing, showcasing how waterfowl were experimenting with a variety of different niches during this ecological explosion. And the large variety of new small mammals didn't go unnoticed either - while other early owls are known from Europe, Primoptynx was both the oldest and the biggest, probably thanks to all the new small mammals to eat! There were also possible ground raptors, similar to Bathornis, though they have not been named.

While there are many questions left to answer, it is clear that the PETM had a major effect like it did on everything else on the planet during that time - and the tropical ecologies that they evolved in during the early Eocene would have many implications, especially for where different clades live today!

Sources:

Houde, P., M. Dickson, D. Camarena. 2023. Basal Anseriformes from the Early Paleogene of North America and Europe. Diversity 15 (2): 233.

Mayr, 2022. Paleogene Fossil Birds, 2nd Edition. Springer Cham.

Mayr, 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance (TOPA Topics in Paleobiology). Wiley Blackwell.

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fossil Novembirb: Day 8 - Raptors Are Back

Once the Cenozoic had begun, the only remaining dinosaurs were modern birds. That means raptors (or dromaeosaurs) would never again stalk the Earth, right? Wrong! Raptor dinosaurs get their name from modern raptors: eagles, hawks, owls and the like; and they are in fact some of the closest relatives of birds. So during the Paleogene period when predatory birds started to radiate, they weren't reinventing being a raptor. They continued being raptors.

Palaeoglaux: An early owl from Germany's Messel Lake, about 40 million years ago. Unlike modern owls, it had strange ribbon-like feathers on its body, likely used in display.

Horusornis: A strange relative of hawks and eagles that lived in France 35 million years ago. Like modern harrier-hawks, it had flexible feet to dig out prey from tree cavities.

Antarctoboenus: An early relative of falcons found from Antarctica, about 35 million years ago. It may have prowled near the edges of giant penguin colonies.

Danielsraptor: Another early falcon from the 50 million year old London Clay formation. It had a large jagged beak and long legs, which helped it catch prey on the ground.

Dynamopterus: A relative of Seriemas and terror birds from Messel lake, about 40 million years ago. It likely caught small vertebrates from the forest floor.

Paleopsilopterus: One of the earliest known terror birds, it lived in Brazil about 50 million years ago. It was already flightless and similar to later small terror birds.

Bathornis: A distant relative of terror birds that was remarkably successful. This flightless predator and its relatives lived in North America from the Late Eocene to the Oligocene.

Messelastur: A falcon-like bird of prey that was closely related to parrots and passerines instead of raptors. It lived in Messel Lake about 40 million years ago.

Masillaraptor: A tiny true falcon also known from Messel Lake. It had a relatively long beak from a falcon, and it may have fed mostly on large insects.

Tynskya: Another small raptor related to parrots and passerines, this falcon-like predator lived around 50 million years ago. Its remains have been found in North America and Europe.

#Fossil Novembirb#Novembirb#Dinovember#birblr#palaeoblr#Birds#Dinosaurs#Cenozoic Birds#Palaeoglaux#Horusornis#Antarctoboenus#Danielsraptor#Dynamopterus#Paleopsilopterus#Bathornis#Messelastur#Masillaraptor#Tynskya

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

TMMN Alien Society - Analysis

This is only based on little lore we know and is just my analysis and theory

Based on the landscapes, the suken buildings, the vulcano in the background, the tropical plants etc, we can assume this was pre-modern humans Japan, Hunter-gatherers arrived in Japan in Paleolithic times, 30,000 BC but the Japanese archpelago dates back as far as 100,000 years.

Jōmon Culture ( REAL LIFE / EARTH EVENTS) Middle Jōmon (ca. 2500–1500 B.C.) This period marked the high point of the Jomon culture in terms of increased population and production of handicrafts.

Look who has lots of ceramic’s

handcrafts

The warming climate peaked in temperature during this era, causing a movement of communities into the mountain regions.

Late Jōmon (ca. 1500–1000 B.C.) As the climate began to cool, the population migrated out of the mountains and settled closer to the coast, especially along Honshū’s eastern shores. Greater reliance on seafood inspired innovations in fishing technology, such as the development of the toggle harpoon and deep-sea fishing techniques. This process brought communities into closer contact, as indicated by greater similarity among artifacts. Circular ceremonial sites comprised of assembled stones, in some cases numbering in the thousands, and larger numbers of figurines show a continued increase in the importance and enactment of rituals.

Final Jōmon (ca. 1000–300 B.C.) As the climate cooled and food became less abundant, the population declined dramatically. Because people were assembled in smaller groups, regional differences became more pronounced. As part of the transition to the Yayoi culture, it is believed that domesticated rice, grown in dry beds or swamps, was introduced into Japan at this time.

This all seems to tie perfectly with the alien race in Tokyo Mew Mew New.

Fauna: This goofy bird reminds me of a bird of terror

Phorusrhacids, colloquially known as terror birds, are an extinct family of large carnivorous flightless birds that were among the largest apex predators in South America during the Cenozoic era; their conventionally accepted temporal range covers from 53 to 0.1 million years ago. They ranged in height from 1 to 3 m.

Aliens domesticating terror birds? BASED. But aren’t them specific to America? Yeah but this is an anime with aliens and magical girls and genetic modified humans XD so maybe terror birds could have existed in Japan in this timeline...or some regular herbivore bird simply evolved into a big BIRB. Well back to the main topic, the enviroment and climate change, like real life records show, this “region” climate began to warm so much it started raising the sea level.

But why some refuse to leave?

if we think of real life experience: wars and dramatic climate changes can lead people to find a new way to survive elsewhere or on the other side to stay and try to overcome the difficulties, ti is always been like that.

they're afraid of the unknown, what waits them out there may be worst than their fate on earth sentimental behavior,elders etc

My theory is that, they’ve sent a couple of aliens into the new world in order to build a decent new home for everyone, once their new home was established they would come back and take the rest with them.

But sadly the disaster occured too soon, before the previous team could have contact with the “aliens on earth”- Probably the human species could have develop from the previous “aliens” that survived and lost their “alien” characterisitcs or simply evolved the normal way real humans did

Source for Jomon culture

65 notes

·

View notes

Photo

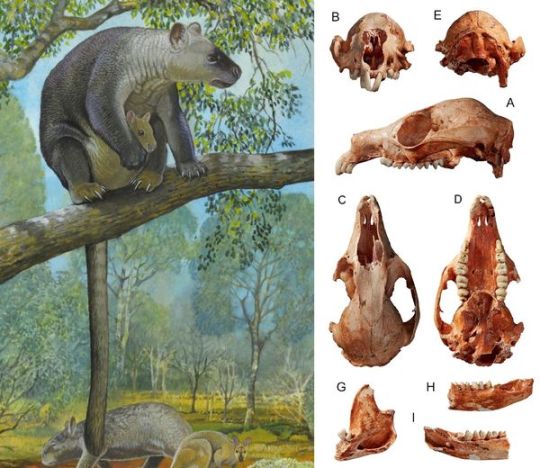

A review of the late Cenozoic genus Bohra (Diprotodontia: Macropodidae) and the evolution of tree-kangaroos

GAVIN J. PRIDEAUX, NATALIE M. WARBURTON

Abstract

Tree-kangaroos of the genus Dendrolagus occupy forest habitats of New Guinea and extreme northeastern Australia, but their evolutionary history is poorly known.

Descriptions in the 2000s of near-complete Pleistocene skeletons belonging to larger-bodied species in the now-extinct genus Bohra broadened our understanding of morphological variation in the group and have since helped us to identify unassigned fossils in museum collections, as well as to reassign species previously placed in other genera.

Here we describe these fossils and analyse tree-kangaroo systematics via comparative osteology. Including B. planei sp. nov., B. bandharr comb. nov. and B. bila comb. nov., we recognise the existence of at least seven late Cenozoic species of Bohra, with a maximum of three in any one assemblage.

All tree-kangaroos (Dendrolagina subtribe nov.) exhibit skeletal adaptations reflective of greater joint flexibility and manoeuvrability, particularly in the hindlimb, compared with other macropodids. The Pliocene species of Bohra retained the stepped calcaneocuboid articulation characteristic of ground-dwelling macropodids, but this became smoothed to allow greater hindfoot rotation in the later species of Bohra and in Dendrolagus.

Tree-kangaroo diversification may have been tied to the expansion of forest habitats in the early Pliocene. Following the onset of late Pliocene aridity, some tree-kangaroo species took advantage of the consequent spread of more open habitats, becoming among the largest late Cenozoic tree-dwellers on the continent. Arboreal Old World primates and late Quaternary lemurs may be the closest ecological analogues to the species of Bohra.

Read the paper here:

https://mapress.com/zt/article/view/zootaxa.5299.1.1

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Multituberculate Earth: Dryolestoidea/Meridiolestida

(As with all animal pages so far, this only goes so far into the Miocene… for now)

Xenotamandua allocaellusfrom the Paleocene of Bolivia.By pale.relics.

The thesis of this project is a world where multituberculates rose to dominance instead of placental and marsupial mammals. In doing so, I uplifted some other groups as a butterfly effect, but no group stands so starkly as dryolestoids, a completely unrelated lineage of mammals sharing equal power in this timeline. This is because dryolestoids, alongside multituberculates, likely suppressed therian expansion until their decline, so it makes so logical sense that whatever didn’t cause the downfall of multtuberculates also allowed dryolestoids to keep on thriving.

Plus, they’re fun as well.

Dryolestoids are in many respects similar to therian mammals and likely close relatives, differing primarily in some cranial aspects like a well developed premaxilla, double canine roots, slower tooth eruption patterns (indicative of longer lifespans compared to therian mammals) and the presence of “eupantothere” molars, a sort of intermediate between the triconodont teeth of mammals like eutriconodonts and the tribosphenic teeth of therians. Unlike multituberculates they don’t have a palinal stroke, instead mostly chewing “normally”, so they lack many of their pecularities. Like with multituberculates phylogenetic bracketing suggests they probably had a cloaca, internal testicles and bifurcated penis like modern monotremes and marsupials.

Dryolestoids first appear in the fossil reccord in the Mid to Late Jurassic, roughly at the same time as early therians from which they split likely shortly before. They were common in the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous of Europe, but disappear from the nothern continents around the Mid-Cretaceous, likely due to ecological turnovers caused by the spread of flowering plants. This was no problem, however, as some had made it to Africa and then South America, where they not only survived but actually became the dominant mammals alongside gondwanatheres. Most of these Late Cretaceous forms belong to the group Meridiolestida, but a few basal forms continued to survive until the KT event.

Cretaceous forms were rather diverse, including insectivores (some of which possibly sengi-like) and large herbivores and omnivores. The KT event seems to have obliterated a large portion of their diversity, but the Paleocene saw some diversity in South America and Antarctica, culminating in the giant herbivore Peligrotherium tropicalis, the largest south american mammal of its time and likely functionally similar to the black rhino. Afterwards their fossil reccord is much scarcer, with an Eocene Antarctic tooth and the Miocene mole-Like Necrolestes, ending their long reign in a strange little note.

Suffice to say, in this timeline they do not decline, and keep on diversifying across South America, Antarctica and Australia, even as the landmasses break apart. Though a few new faces like ptilodontoideans have shown up in their turf, for the most part their reign continued uninterrupted even across major events like the PETM and Grand Coupure, ranging from small insectivores to some of the largest mammals of this timeline.

Leonardidae

Sorilestes andinafrom the Paleocene of Bolivia.By pale.relics.

By far the most diverse lineage, leonardids first occur in the Cretaceous in the eponymous genus Leonardus and the closely related Cronopio, the latter in particular occasionally well known for its long canines, resembling Scrat from the Ice Age movies. They are ancestral to the Cenozoic mole-like Necrolestidae, so Leonardidae is treated here as paraphyletic in relation to that clade. The clade Brandoniidae is a controversial assemblage which may or may not be valid as it is known only from teeth that might belong to leonardids or mesungulatids; henceforth, putative members are treated as part of this group.

Fo gaxie, an animal used to play with the controversy of Brandoniidae. From the Paleocene of Bolivia, by pale.relics, you know the drill.

Leonardids occupied small omnivorous and insectivorous niches in the Cretaceous and ultimately that’s how they ended in our timeline (if as highly unusual mole mimics), but in this timeline they are a very diverse bunch, if tending toards carnivorous niches. They include also a variety of forms convergent with our didelphids (fittingly the clade Pseudodidelphidae), sengi-like runners (the aforementioned ‘brandoniids’), anteater-like forms and a few large carnivores. Their diversity increased in particular during the Miocene, as their larger mesungulatid cousins declined.

Sacadelphys, a pseudodidelphid. From the Paleocene of Bolivia, by pale.relics

Two particular clades went on to have a global success beyond the southern continents: Necrolestidae and Allochiropteridae:

The former started off as burrowing mole analogues as in our timeline. However, here they took to the seas in the Late Eocene genus Camahueto, spreading across the world’s oceans in the Oligocene. Propelled by four flippers like mammalian pliosaurs, they typically range at about porpoise size (though a few forms grew to up to 6 meters and as small as desman size in freshwater habitats), and occupy a variety of niches taken in our timeline by large fish, cetaceans and seals, from hunters of squids, shrimps and the remaining fish to durophagists plucking molluscs from the sea bed to macropredators hunting other marine mammals.

The latter took to the skies in wings rather similar to those of true bats from our timeline, their similarity earning them their name (“different hand wings”). The first forms evolved in Antarctica as semi-terrestrial foragers like our mystacine bats, but quickly flew far and wide across all major continents, some forms becoming flying-fox like frugivores and others hawking insectivores. They largely remain small sized compared to other contemporary flying mammals, rarely exceeding two meter wingspans.

The allochiropterid Chimil kaslem, from the Oligocene of Antarctica. Here depicted with speculative structural colours like those of mandrill faces, exhibitting for a potential mate. By hodarinundu

With generally dog-like faces, leonardids offer at least a hint of the familiar in this strange world.

Mesungulatidae

Allqu uyam, a relatively conservative mesungulatid. From the Paleocene of Bolivia, by pale.relics

Mesungulatids already started off big in the Cretaceous as formerly shown, and so it is no surprise that in this timeline they quickly diversified as megafaunal species. Some forms resemble their Cretaceous ancestors, occupying raccoon or skunk-like niches while leonardids and notoptilodontoideans crowd them at all sides.

But it didn’t take long for change to came in drastic aways. One lineage related to Peligrotherium (hence Peligrotheriidae) grew rapidly, already reaching the 3 ton threshold by the Paleocene, and only increasing in size across the Eocene and Oligocene with some forms rivalling our indricotheres and elephants as largest land mammals of all time. Some of these gigantic herbivores developed long necks, allowing them to literally tower above the gondwanathere competition, though peligrotheriids tend to be more mixed feeders compared to those hard-plant specialists. Unlike them, they have a more lateral and orthal chewing style functionally similar to that of rhinos, which also allows them to extract nutrients from plants differently. Others developed powerful canine tusks, used both for sexual selection as well as to dig out tubers and roots. Giant herds of peligrotheriids cross South America, Antarctica and Australia, true heirs to the sauropods of the Mesozoic.

Baroauchenia canifacis, here portrayed as a Falkor cosplayer but potentially hairless since its supposed to be a fossil species and all.From the Paleocene of Bolivia, by pale.relics

By contrast, some mesungulatids went in the complete opposite direction and became the mammalian apex predators of the southern continents. Some of these animals, vaguely cat or fossa-like, used their clawed forelimbs to wrestle with their prey until a fatal bite was strategically placed. Others, more akin to dogs and hyenas, developed crushing and terrifying jaws, running after their prey. Such animals might represent several different lineages, that took to a more carnivorous lifestyle as gondwanatheres and peligrotheriids expanded, turning competition into food. Developing carnassial-like teeth to cut meat, they quickly turned to hypercarnivory with few omnivorous forms, which has served them well for now but might become a liability when biomes become more unstable in the future.

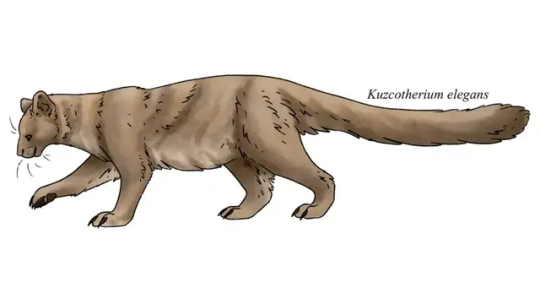

Kuzcotherium elegans, a carnivorous form related to Allqu uyam.From the Paleocene of Bolivia, by pale.relics

Be them carnivores or omnivores, mesungulatids are some of the most impressive mammals currently alive, but as Antarctica cools and South America and Australia dry they might have to give up their throne soon enough. And indeed, across the Miocene, mesungulatids, both herbivorous and carnivorous, have started to decline…

#multituberculate earth#dryolestida#dryolestidae#dryolestoidea#meridiolestida#spec evo#speculative biology#speculative zoology#speculative evolution

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

I didn't know you had other prehistoric dragons! Without the pictures, what's the list of them?

I may add more in later drafts but so far:

Late Jurassic Dracomoph (Protodraconis)

Early Cretaceous Dracosuchians (Dracosuchus, Pyrosuchus)

Early Cretaceous Dracovermians (Dracovermis, Tiamat)

Late Cretaceous testudrakoids (Clypeus, Testudisuchus),

Late Cretaceous dracotheroid (Ursadraco)

Late Cretaceous Draconiforms (Longwang, Eondraco and Sinodraco).

Then things get muddy in the Cenozoic, half due to a knowledge gap on my end, and half because dragon skeletons got lighter as they specialized for flight, and magical flight also makes them a host to thaumophagic bacteria which break down the body super fast after death, meaning it is difficult to get a clear fossil record on these animals :)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time to show off my timeline again, since there’s been a lot of additions since last time I posted it. Let’s take a closer look, starting at the end!

I really need to do some Cenozoic art of my own, but this gorgeous Synthetoceras and the macaws at least give me something to put here. The scale of my timeline is one million years=three centimetres. At that scale, the Holocene is a barely visible pen strike at the bottom of the Quaternary.

The Late Cretaceous is quite full, yet I couldn’t resist adding the gorgeous Nanuqsaurus. (All art not by me came from Studio 252mya (except the little cards from my Beasts of the Mesozoic))

Late Jurassic and early Cretaceous are both developing some big art clusters too.

Space is limited above my bookcases, but the late Triassic and early Jurassic now have some art to fill it up anyway.

The Permian and Carboniferous, along with a wider shot of that wall.

Not much going on in the corridor and entrance to my bedroom yet. I have a vague idea for a piece involving Tiktaalik but I still have to hammer it out.

The early Paleozoic is really starting to fill out now. The huge void I had here inspired me to a bunch of art I probably never would have considered otherwise, which is one of the joys of this project.

Finally, the Ediacaran! It continues to the Cryogenian at the window from here, but I don't have any art there yet.

#timeline#geologic timescale#palaeoblr#paleoart#my art#yes i know my house is a mess you haven't seen the half of it

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crystal Palace Field Trip Part 3: Walking With Victorian Beasts

[Previously: the Jurassic and Cretaceous]

The final section of the Crystal Palace Dinosaur trail brings us to the Cenozoic, and a selection of ancient mammals.

Image from 2009 by Loz Pycock (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Originally represented by three statues, there are two surviving originals of the Eocene-aged palaeotheres depicting Plagiolophus minor (the smaller sitting one) and Palaeotherium medium (the larger standing one).

The sitting palaeothere unfortunately lost its head sometime in the late 20th century, and the image above shows it with a modern fiberglass replacement. Then around 2014/2015 the new head was knocked off again, and has not yet been reattached – partly due to a recent discovery that it wasn't actually accurate to the sculpture's original design. Instead there are plans to eventually restore it with a much more faithful head.

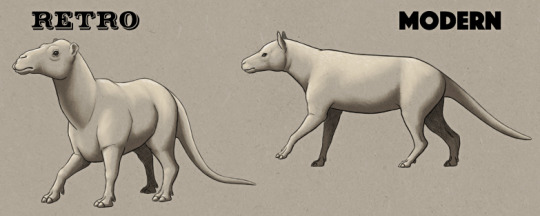

These early odd-toed ungulates were already known from near-complete skeletons in the 1850s, and are depicted here as tapir-like animals with short trunks based on the scientific opinion of the time. We now think their heads would have looked more horse-like, without trunks, but otherwise they're not too far off modern reconstructions.

There was also something exciting nearby:

The recently-recreated Palaeotherium magnum!

This sculpture went missing sometime after the 1950s, and its existence was almost completely forgotten until archive images of it were discovered a few years ago. Funds were raised to create a replica as accurate to the original as possible, and in summer 2023 (just a month before the date of my visit) this larger palaeothere species finally rejoined its companions in the park.

Compared to the other palaeotheres this one is weird, though. Much chonkier, wrinkly, and with big eyes and an almost cartoonish tubular trunk. It seems to have taken a lot of anatomical inspiration from animals like rhinos and elephants, since in the mid-1800s odd-toed ungulates were grouped together with "pachyderms".

———

Next is Anoplotherium, an Eocene even-toed ungulate distantly related to modern camels.

(Apparently the sculpture closest to the water is a replica of a now-lost original, recreated from photo references in the same manner as the new Palaeotherium magnum. I can't find a definite reference for when this one was done, though – I'd guess probably during the last round of major renovations in the early 2000s, at the same time as the now-destroyed Jurassic pterosaur replicas?)

Anoplotherium commune is a rather obscure species today, but it was one of the first early Cenozoic fossil mammals to be recognized by science in the early 1800s. Depicted here as small camel-like animals, the three statues are positioned near the water's edge to reflect the Victorian idea that they were semi-aquatic based on their muscular tails.

Today we instead think these animals were fully terrestrial, using their tails to balance themselves while rearing up to reach higher vegetation. Their heads would also have looked a bit less camel-like, but otherwise the Crystal Palace trio are still really good representations.

———

Next is a sculpture that's very easy to miss in the current overgrown state.

Who's that peeking over the bushes?

Going all the way around to the far side of the lake reveals a distant glimpse of the Pliocene-to-Holocene giant ground sloth Megatherium.

A better view of the Megatherium | "Tree Hugger" by Colin Smith (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Fossils of Megatherium americanum had been known since the late 1700s, but the 1854 Crystal Palace statue was still one of the first life reconstructions of this animal. Its anatomy is actually very close to our modern understanding, depicted with correctly inward-turned feet and sitting upright to feed on a tree with its tail acting as a "tripod".

However, we now know it didn't have a trunk-like nose, but instead probably had prehensile lips more like those of a modern black rhino.

Something weird also appears to have happened to the Crystal Palace Megatherium's hands. Early illustrations of the sculpture all consistently show it with the typical long claws of a sloth, but today it's missing its right hand and its left has only a strangely stumpy paw – suggesting that at some point in the intervening 170 years there was an unrecorded crude repair.

———

And finally we end the trail with three Megaloceros, the Pleistocene-to-Holocene "Irish Elk" that's actually neither exclusively Irish nor an elk.

A closer look at the second stag and the doe.

There was originally a fourth giant deer sculpture in this herd, a second resting doe, but it was destroyed sometime during the mid-20th century. The stags also initially had real fossil antlers attached to their heads, but these were removed and replaced with less accurate versions at some point by the mid-20th century.

One of the stags' antlers suffered some damage in 2020, ending up drooping, and since then one antler has either fallen off or been removed.

In the 1850s Megaloceros giganteus was thought to be closely related to deer in the genus Cervus, and so the Crystal Palace reconstructions seem to be based on modern wapiti – specifically in their winter coats, fitting for ice age animals – since both the stags and the doe sport distinctive thick neck manes.

The stags from the other side.

We now know Megaloceros was actually much more closely related to modern fallow deer, and so probably resembled them more than wapiti. Cave art also shows that it had a hump on its shoulders, and even gives us an idea of what its coloration was.

———

…But wait!

There's actually one more thing.

A small statue sitting on the far side of the deer herd, missing its ears, and seemingly representing a Megaloceros fawn.

Except it's actually something very different and very special.

Ceci n'est pas un cerf.

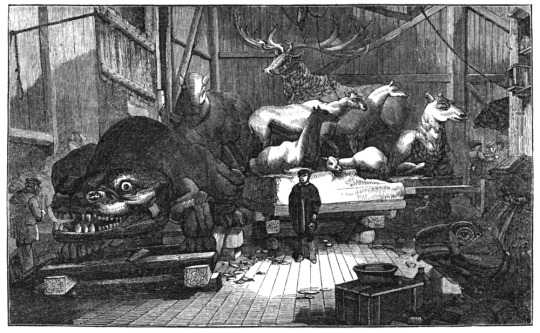

Some recent investigation work revealed some surprising information about the Crystal Palace mammal statues – much like the nearly-forgotten large Palaeotherium, there was originally an entire group of four small Eocene-aged llama-like Xiphodon gracilis that had disappeared from living memory.

There was also no historic record of a fawn with the giant deer, but instead a suspiciously similar-looking sitting sculpture is illustrated among what we now known are the four missing Xiphodon in early records.

An 1853 illustration of the sculpture workshop. The four Xiphodon are shown in the center, directly in front of a Megaloceros stag and doe. (public domain)

Somewhere in the late 19th or early 20th century three of the Xiphodon must have been completely lost, and the remaining individual was misidentified as a fawn and placed with the giant deer herd.

———

Rediscovering a whole extra species among the Crystal Palace statues is exciting, but it also demonstrates just how much of these sculptures' history has gone completely undocumented.

The mammal statues especially seem to have suffered the most out of the "Dinosaur Court", being often overlooked, neglected, disrespected (at one point the Megatherium was inside a goat pen in a petting zoo!), and subjected to cruder repairs. A total of five original statues are now known to be missing from this Cenozoic section – the original large Palaeotherium, the three other Xiphodon, and the second Megaloceros doe – compared to the two pterosaurs lost from the Mesozoic island.

Hopefully the excellent recreation of the lost Palaeotherium magnum is the start of a long overdue new lease of life and conservation attention for all of the Crystal Palace sculptures. It was disappointing seeing them all in such an overgrown state, and with signs of ongoing disrepair in places such as the plant growing out of the big ichthyosaur's back.

But there has been some resurgence of interest and public attention in the Crystal Palace sculptures over the last few years, so with any luck these historic pieces of early paleoart will survive on to their 200th anniversary and beyond, to keep on reminding us of where things began and how far our understanding of prehistoric life has since come.

#field trip!#crystal palace dinosaurs#retrosaurs#i love them your honor#crystal palace park#crystal palace#palaeotherium#anoplotherium#xiphodon#ceci n'est pas un cerf#megaloceros#ungulate#megatherium#ground sloth#mammal#paleontology#vintage paleoart#art#proper art post tomorrow#this took longer than expected#also apologies for my potato-quality camera#i'm an illustrator not a photographer

334 notes

·

View notes

Text

fursona spec. zoo

domain: eukarya kingdom: animalia phylum: chordata class: therapsida order: ophisvillosa ("hairy serpent") family: theregaledae genus: theregale species: theregale montanus ("royal beast from the mountains") common name: montane forest dragon, or simply a "dragon"

a branch of therapsids that diverged from cynodontia in the late permian. they share many similarities with mammals, both convergent and homologus. they are the only known group of animals to have evolved sapience, other than humans.

their numbers began declining in the early cenozoic due to competition with mammals and eventual over-hunting by humans. it is likely only a few hundred of any given species remain. due to their extreme rarity, dragons have been bestowed great significance in human folk-lore, and are highly sought after for trophy hunting.

t. montanus (referred to as "dragon(s)" going forward) is a semiarboreal generalist feeder. their historic range includes much of the rocky mountains. they can be anywhere from 4 feet to 7 feet tall when standing on their hind limbs & necks in a neutral posture. bipedal and digitigrade, though they will often switch to a quadrupedal gait for brief but fast sprints.

dragons are furred, with the structure being practically identical to mammalian hair. their fur is the softest of any known animal, and is even rumored to induce minor euphoria if touched.

individuals can range anywhere from a vibrant brown to a dull grey, and are typically striped or "ticked". pups have a characteristic spot & rosetted pattern. in rare cases these spots will carry over into adulthood as a form of neoteny.

dragons are omnivorous, typically scavengers but will opportunistically hunt prey. due to their very high internal body temperatures, dragons are able to freely feed on carrion without contracting illness, though this temperature requires many excess calories to maintain. their favorite foods include fish, fruits, nuts, and small mammals.

their primary senses are vision, smell, and hearing. rather than the complex nasal cavities of mammals, dragons have convergently evolved a tongue very similar to that of squamates, which flicks outside the mouth almost constantly. the tongue is used both for smelling (of which the fork can differentiate the direction of any given smell), and for sensory purposes, as dragons lack facial whiskers.

dragons possess keratinized display structures that are flamboyant in color. this includes their horns, claws, ears, and scutes (boney plates, embedded in the skin, that run along the dragon's limbs). as the bright coloring only develops during sexual maturity, these are likely to advertise to potential mates.

dragons communicate through clicks, whistles, and squeaks, though they are capable of learning human language. body language is communicated primarily through their ears and tail-flagging. they will wag their tail if excited, flick it if annoyed, etc.

dragons possess "mammary" glands, 2 pairs in total, with some distinctions from true mammary glands in their internal anatomy, along with the highly flexible lips required to drink from said glands. dragons will raise their young, litters of 1-3 individuals, until they are able to fend for themselves in about a decade and a half. newborn pups are only a few inches long and covered in downy fluff.

rapid fire:

long neck that can extend and retract

bird-like feet with reversed first toe, adept at climbing trees opposable thumb for Grabbin uses the shadow of their tail to attract fish

im autistic btw ok bye <3

18 notes

·

View notes