#late Louis XIV fashion

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

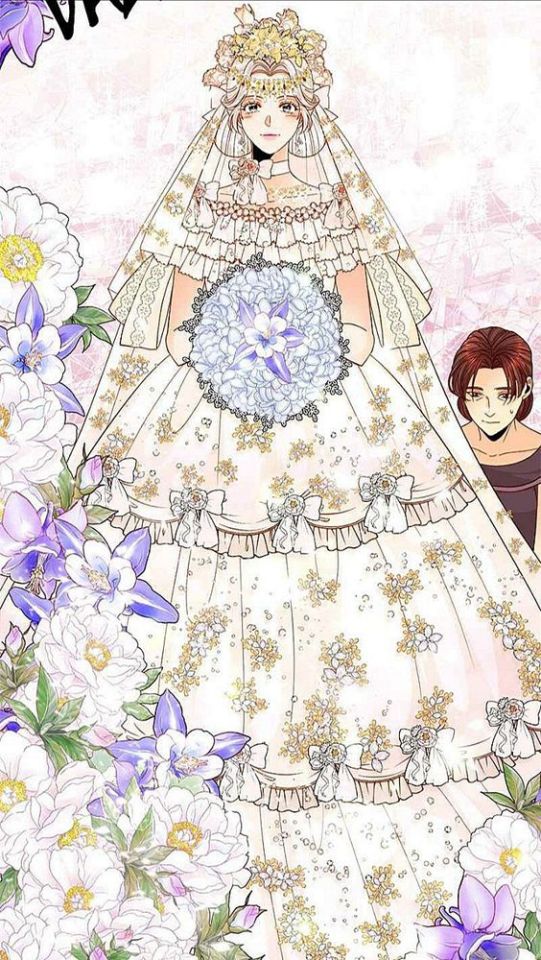

so one thing Rashta is mostly known for outside of being the source of the Trashta meme is her Christmas tree wedding dress and everyone at her wedding making fun of it for being tacky

I'm not gonna lie while it is kind of pretty there is no way that thing did not require some tax payer money.

What gets me is that Remarried empress takes heavy inspiration from European fashion and aesthetics, and if you ever saw a portrait of Queen Elizabeth I, Marie Antionette, or Louis XIV.. you'd know that European nobles in those era wore very excessive clothes and jewelry. it would make more sense if it were commoners who saw the dress making fun of it, but with nobles making fun of her for wearing something flashy on her wedding it just feels like another mandatory hate on Rashta at least once per chapter.

this gets more confusing in the novel version and while to be fair we only get one shot of it, her wedding dress doesn't look as glammed up, if anything Sovieshu is about as decorated as his bride.

(It does look wonky with all random white lines but still not as flashy as a Christmas tree.)

and its not like this is just a "It's a fantasy story, the culture isn't going to be one to one with real history." thing either because Navier's wedding dress is described as having THOUSANDS of gemstones weaved into it.

It may not be as in your face flashy like Rashta's but if there are thousands of those gems in that dress not only would it be likely worth millions but it would also be heavy af. in general it would make sense for both dresses to be this flashy considering they are for royal weddings in a period akin to either the late 18th century or early 19th century but it frankly makes no sense that NOBLES of all people would be mocking Rashta for wearing something tacky when they aren't exactly known for modest dressing.

Tax payer money at it's finest right there.

#the remarried empress#rashta#empress navier#webtoon#maybe it's meant to be commentary on the hypocrisy of the rich but I doubt it

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

1880s: Dominique is very Masculine, and very Eccentric

In today's standards, Dominique is a fairly feminine woman. Yes she's wearing a prince inspired outfit, but it's feminized with the tight pants, long stockings, heels, and long hair, but what if I told you that was all considered masculine in the olden days?

The Time Period

Givn the story takes place when the alternate Eiffel Tower (can't remember the name) was being built, we can assume vnc takes place in the late 19th century, otherwise known as the Victorian era, ranging from 1820 to 1914.

The fashion looked somewhat like this, you can see some similarities to the outfits worn by the main cast.

Dominique's outfit doesn't really resemble much of the fashion at the time, you can make som mild comparisons to Victorian royal menswear, but I'd say her fashion is more similar to 17th century royal menswear, specifically,

King Louis XIV

The long hair, the tight white bottoms, the heels, the loose sleeves, the train of fabric behind him, It is said that King Louis was a big womanizer, who does this all sound like? It's almost as if Dominique is trying to be Louis- oh wait.

Also fun fact, King Louis XIV was born in Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

Masculinity & Eccentricity

For us in the present, King Louis XIV looks pretty feminine, and that was probably a shared sentiment in the 19th century, he looked outdated, but that same outfit on a woman like Dominique would cause some controversy if not for her status.

In the 19th and early 20th century, a woman wearing pants was not too accepted, women usually wore dresses, and pants were kept as a sports/work attire. A woman would not just go on about her day wearing a pair of pants, she'd be seen as strange, and maybe even get into trouble. Dominique wearing pants, and very tight pants reminicscent of older eras, is definetly a bold choice.

Her hair is long and straight, which is not how you'd usually describe a victorian woman's hair. It wasn't even that much of a gender thing, but more of a formality thing. Women at the time would have their long hair in an updo. Actually, according to Whizzpast, long loose hair was a thing only models and actresses wore to depict romantisiscm and intimacy.

Dominique's long hair makes a lot of since, she has a bold, eccentric personality, she's not one to conform, she's the current family outcast, but she is also a very romantic person, and is constantly seen in romantic/intimate scenes, so her loose hair really depicts that.

All in all, Dominique's appearance states a bold, romantic blast to the past with a pinch of her desceased brother.

If you want to look into queer subtext, you can assume that''s one of the reasons Noe drinks her blood.

#damn this is the longest analysis/essay I've done in a while#vnc really makes me think#vnc#vanitas no carte#dominique#dominique de sade#french fashion#fashion history#anime#manga#the case study of vanitas

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

so uh. i casually used the phrase “deus ex machina” about the movie my cousins i’m babysitting are watching, and of course one of my cousins asked what that meant. so i explained it and for an example i mentioned tartuffe, which in retrospect is not the best example to explain the concept of a deus ex machina to an eight year old with, but by then it was too late and she was asking why it was ok for the king to act like a god, so then i started explaining louis xiv’s whole sun king deal to her. i showed her a picture of him, and she asked why he was dressed like that, which led to a discussion of eighteenth century french fashion, which led to her learning women were not allowed to wear pants in public into the twentieth century, which. led to me explaining the basics of modern intersectional feminism to her. hope i didn’t fuck up

#i mean i know her family they’re pretty liberal so i should be ok on that front#but also i probably shouldn’t have brought up tartuffe with an eight year old in the first place#ryddles

98 notes

·

View notes

Photo

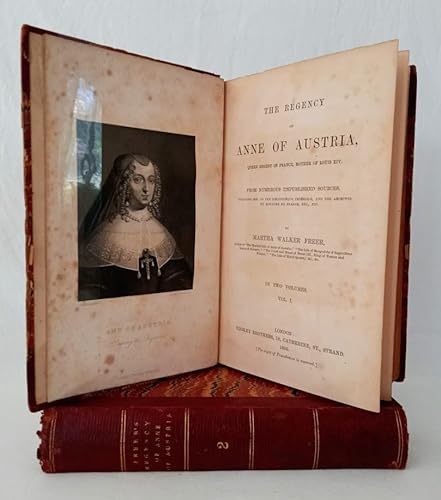

The Regency of Anne of Austria, Queen Regent of France, Mother of Louis XIV

Martha Walker Freer’s “The Regency of Anne of Austria, Queen Regent of France, Mother of Louis XIV” is a classic text that delves into the life of Anne of Austria during her reign and regency by using numerous previously unpublished sources. Aimed at scholars and enthusiasts of 17th-century French history, this book provides an exceptional understanding of Anne of Austria’s contributions to French history.

The Regency of Anne of Austria, Queen Regent of France, Mother of Louis XIV by Martha Walker Freer (1822-1888) is a beautifully written classic work that not only characterizes Anne of Austria but also places her in the broader context of French History. Consisting of two volumes, this classic text aims to illuminate the intricacies of Anne’s regency which is typically overshadowed by the reign of her son, King Louis XIV, also known as the Sun King. Freer creates a diligent spread of the numerous sources that give life to Anne’s rule.

The chapters cover various aspects of Anne’s regency, such as her relationship with others in court, her policies and the policies of others, and the many adversities that she faced in this period of her life. This work provides a detailed analysis of Anne’s contribution as a French queen. Freer’s use of previously unpublished sources helps this text stand out from others in the same time and genre as the unique reference sources provide readers with a fresh and nuanced look at Anne of Austria’s life. This, in return, allows this book to address multiple events and introduce many individuals while presenting new insights and analyses of Anne’s life during her regency.

With her regency constantly shadowed by different French rulers, Anne of Austria’s regency is seldom referenced or discussed. French history can become complicated, especially when concerning the monarchs and their enemies and allies, as all must coexist within the French court. With the numerous sources describing Anne’s reign as regent, readers are allowed to learn more about the intricacies of French court life and the many decisions and factors that went into ruling this country. From adopting the policies of her former enemies in court to building her own supporting council of advisors and allies, and even contesting the will of her late spouse, this book constructs a three-dimensional view beyond a simple biography to complicate Anne of Austria.

Freer’s writing style keeps readers engaged and wanting more as the narrative tone helps readers follow along with the story. The use of exclamatory dialogue allows the mentioned figures to seem more human and provides a place to gather quotes from several historical French figures. The book also includes the lyrics of popular contemporary French songs. This emphasizes Freer's argument by allowing readers to become more immersed in life in 17th-century France. Freer does a wonderful job of introducing new historical figures and policies by utilizing footnotes. The book's footnotes provide complementary information, such as brief explanations of the relationships between historical figures, directions for further readings, and a brief history of architectural structures. These informative additions completely transform the reading experience as the reader is supplied with further context to ensure that they understand the nuances of the time, and make connections between the various events.

While this is a great read for those with an academic background or research purposes, this book may be too detailed and specialized for everyday readers. Given the tumultuous nature of French history, previous knowledge of 17th-century French history and politics is recommended to follow along. Having written multiple books on French history in similar fashions, Freer's work is one that underwent much research to encompass the complexities of the time. It would be a wonderful primary source used in scholarly writing.

Born in Leicestershire, United Kingdom in 1822, Martha Walker Freer was an English woman who wrote of the various topics that created French history, especially the women who contributed significantly to French nation-building. Even after she wed Rev. John Robinson, Freer continued to write her many works under her maiden name. Overall, this is a highly recommended book for those interested in learning about an overlooked French queen from a spectrum of perspectives.

Continue reading...

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

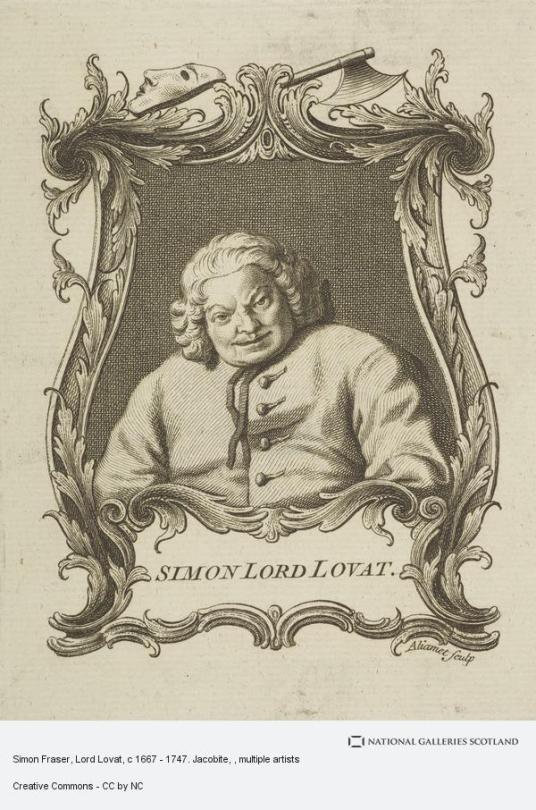

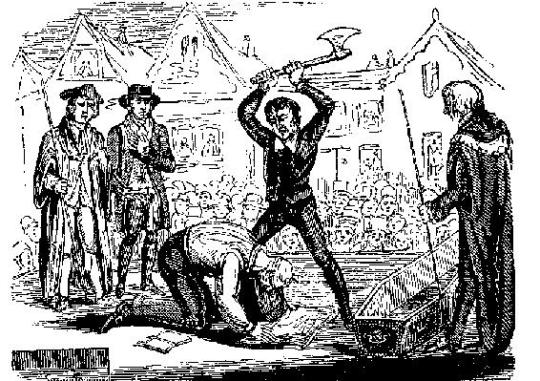

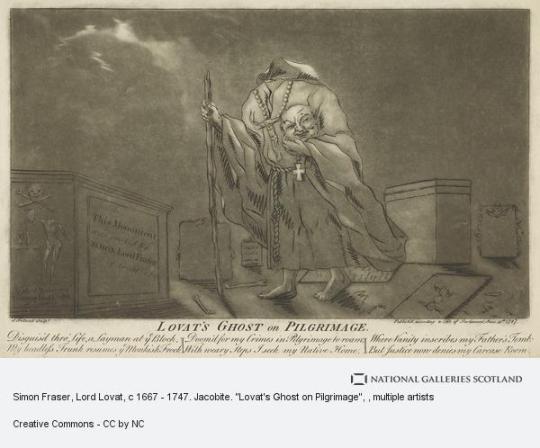

On 9th April 1747 Simon Fraser, Lord Lovat, the leading Scottish Jacobite rebel was beheaded on Tower Green.

A longer post than normal from me as in my opinion Simon Fraser was one of the most interesting characters in Jacobite history. A man of contrary, he was known to be very kind to the lesser clansmen taking a paternal interest in their affairs. A quote regarding him says that….“Generally he had a bag of farthings for when he walked abroad the contents of which he distributed among any beggars whom he met. He would stop a man on the road; inquire how many children he had; offer him sound advice; and promise to redress his grievances if he had any”

In his own estimate, he took care his clansmen were ‘always well-clothed and well-armed, after the Highland fashion, and not to suffer them to wear low-country clothes’ Lovat was also a brute of a man forcing a young woman into marriage and raping her in an attempt to legitimise the union. Lovat has become more well know lately thanks to Outlander, where in their world he is grandfather to the main protagonist Jamie Fraser and played brilliantly by the fine Scottish actor Clive Russell. Back in the real world he has been in the news in the recent past, I shall cover that at the end of this post.

Born in 1667 into the ancient clan who fought with distinction in the Wars of Independence – Sir Simon Fraser was one of the co-victors of the Battle of Roslin and his sons were close friends of Robert the Bruce, Alexander marrying Bruce’s sister Mary – Simon was the second son of Thomas Fraser of Beaufort who was closely related to Lord Hugh Fraser of Lovat, chief of clan Fraser.

Simon became his father’s heir when his elder brother was killed fighting alongside Bonnie Dundee against the forces of King William III at the Battle of Killiecrankie in 1689. He was still nowhere near being clan chief, however, and took himself off to Aberdeen University from which he graduated in 1695. Lord Hugh Fraser, the 9th Lord Lovat, was a weak man who unexpectedly signed over the clan leadership to Simon’s father in 1696.

Lord John Murray, Earl of Tullibardine and the most powerful man in Scotland, disputed the succession and fell out spectacularly with Simon in Edinburgh. The young Fraser hothead duly went north to Castle Dounie to try and persuade Hugh’s widow Amelia to give him the hand of her daughter, also Amelia, in a dynastic marriage that would seal his succession. Tullibardine was having none of it and moved his niece to the Murray stronghold, Blair Castle, where he planned to marry her off to Alexander Fraser, heir to the Lordship of Saltoun.

Simon retaliated by kidnapping Alexander and frightening him away, and to make matters worse in October, 1697, he went back to Castle Dounie and forced the widow Amelia into a sham wedding, raping her to consummate the “marriage”.

Tullibardine ensured Simon and his father were declared outlaws and when old Thomas died in 1699, Simon was unable to legally claim his title as 11th Lord Lovat which later passed to one Alexander Mackenzie who had legally married the younger Amelia.

Simon Fraser somehow managed to persuade King William that he was no threat, despite having his own personal army, and he was pardoned in 1700, only to be declared an outlaw again the following year over the forced marriage and rape.

Simon went off to the court of the Stuarts in France where he devised the plans that were eventually used in the 1715 and 1745 uprisings. Long before the former, however, Simon was double dealing, giving Queen Anne information about the plans of James, the Old Pretender. He was found out and King Louis XIV clapped him in jail for three years.

Even after he was released he was prevented from travelling to Scotland and thus missed the Act of Union which he opposed.

Still desperate to get his Lovat title and the chieftainship of his clan back, Simon sided with the forces of the new King, George I, during the ’15, and was given back his title as a reward, with Alexander Mackenzie imprisoned for being a Jacobite. The two men would fight in the courts for the next 15 years as to who was entitled to the income of the estate. Simon eventually won and spent his time building up the Fraser estates and wealth, even taking command of one of the Independent Companies of Highland soldiers established by the Hanoverian regime – the Fraser Highlanders.

As I said early Fraser was a man of contrary and to me was very like “Bobbing John” The Earl of Mar another Jacobite who a tendency to shift back and forth from faction to faction, no sooner had Fraser built up this “Hanoverian” army that he started openly campaigning for the restoration of the Stuarts. The Government responded by cancelling his military role.

When Bonnie Prince Charles landed in Scotland he was still playing games.

He allowed his sons to fight for the Stuarts, but stayed at home himself “loudly lamenting the wilful disobedience of children,” as Sarah Fraser has put it. Lovat did meet Charles, however, and expressed his anger at the lack of “siller” which he knew would be necessary for a successful campaign. They met again after Culloden, at which Clan Fraser fought bravely and suffered many casualties, and Lovat advised the prince to get away and re-form his forces. Charles fled through the heather, as we know, and made it to France while anyone associated with the Bonnie Prince was hunted down. The Duke of Cumberland’s troops were not taking any more games from Fraser and burned Castle Dounie.

Lovat managed to make it to Loch Morar but was captured there while hiding in a hollow tree. Although approaching his 80th birthday, The Fox was taken south to London.

He pled not guilty but his trial was a formality and he must have know his fate would be the same as previous nobles, the Earls of Kilmarnock, Balmerino and Derwentwater who were executed for treason the previous year.

At his trial, ever the Fox he insisted strongly upon his affection for the reigning family. Such were the characteristics of Simon Fraser, but of course he was found guilty the sentence, hanging, drawing and quartering was commuted later to a mere beheading by the King.

In a way, Lovat had the last laugh. Newspapers and pamphlets of the time recorded that as he was led out to the scaffold on Thursday, April 9, 1947, a wooden stand that had been erected near the Tower to seat crowds eager to see the execution collapsed sending hundreds plunging down. At least nine people died and dozens were injured, which amused Lovat – the phrase ‘laughing your head off’ is said to date from that event.

According to a woodcut print made on that fateful day, Lovat “with some composure laid his head on the block which the executioner took off with a single blow.”

As I mentioned at the top Lovat has been in the news quite recently. Simon had requested burial at the family mausoleum at Wardlaw near Inverness and the government initially agreed but changed its mind thinking his body could become a rallying point for further trouble. He was therefore buried in the floor of the chapel within the Tower of London, St. Peter ad Vincula. The chapel was refurbished in the 19th century and the floor was relaid. One of the coffins uncovered during the works had the nameplate of ‘Lord Lovat’. The names of those found are now recorded on a plaque on the wall of the chapel.

Fraser folklore, and written in several books says that his body was spirited away from London, the stories even go so far as to name the boat ‘The Pledger’ that sailed north to The Beauly Firth, where he was taken to the family mausoleum, there is even a plaque in the crypt that reads “In this coffin are laid the remains of Simon Lord Fraser of Lovat who, after twenty years in His own Land and abroad with the greatest distinction and renown, at the risk of his own life, restored and preserved his race, clan and household from the tyranny of the Athol and the treacherous plotting of the Mackenzies of Tarbat. To preserve an ancient house is not the greatest credit. Nor is there any honour for the enemy who despoiled it. Although that enemy was strong in his plotting and unrelenting warfare, yet Simon who was also skillful and cunning defeated him in war.“

In 2018 the headless skeleton inside the coffin was exhumed to be examined by experts from the University of Dundee in January this year they announced that the bones in the coffin did not belong to Simon Fraser, but to a young woman. So it looks like his body did end up rotting in The Tower’s Chapel, although the Frasers will still tell you otherwise.

Scottish actor Clive Russell played The Old Fox in the television adaptation off Outlander.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

1888 Chromolithograph Maintenon Conti Bourbon Fashion Fontange Dress

This is a rare original 1888 color chromolithograph which portrays, right down to the beauty marks, a selection of aristocratic figures from the court of King Louis XIV of France, all are dressed to the nines in the fashions of the late 17th century. The women are wearing their hair á la fontange, with wired headdresses perched above their well-maintained curls, a popular trend which promoted a tall, feminine look.

A unique feature of this illustration, which may be difficult to see in the digital image, is the use of silver ink, which not only shimmers when it catches the light but also accentuates some of the finer details that might otherwise be missed.

Top - Madame de Maintenon - Dowager princess of Conti - Duchess of Bourbon - Elizabeth-Charlotte of Bourbon - Countess of Egmont, Princess of Aremberg - Duchess of Chartres.

Bottom - Upper class woman dressed for winter weather - Mesdemoiselles Loison - Abbot in a cassock and small collar - Upper class women wearing a decorative shawl - Upper class man in summer attire.

#king louis xiv#vintage fashion plates#17th century#french fashions#fashion history#vintage fashion#ilovethis#historical fashion#fashion illustration#silver ink

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Silhouettes of the 18th Century.

A Silhouette is the recognizable shape of fashion as it changes. Fashion in the 18th century reflected affluent society's view on style, personal taste, social position, and world outlook. France was established as a fashion leader in the 17th century, and Paris became a world center for popular modes of dress throughout the 18th century.

The iconic silhouette of the eighteenth century is that of the conically corseted court dress, a simpler line of dress launched the era. The mantua, which dominated the beginning of the eighteenth century to the point that dressmakers were called mantua makers, was introduced in the late seventeenth century as a casual dress alternative to the heavily structured court dress required by Louis XIV. Before the mantua the dresses beforehand took more of a robe format however once the mantua became more formal, the bodice took more of an important role over the dress, the display of the stomacher, an inverted triangle of richly embroidered fabric. The placement of the stomacher allowed for an increasingly full skirts of which created a narrow-waisted silhouette for the mantua, which became increasingly extreme over the course of the eighteenth century. The triangle of the bodice was created by conically shaped stays that pressured the waistline to a small circumference while driving the bosom upward to bob about as a barely contained base for the spherical head. The rectangle at the base of this structure was created by panniers which were constructed with hoops, at first to support a bell-shaped skirt, but later drawn in with tapes at front and back into a flattened ovoid form.

By the 1770s, the silhouette of the skirts shifted away from the squared-off panniers. In the 1770s the polonaise gown was also developed, the waist remained small and pointed into a very full skirt. The fullness of this gown was created through the voluminous drapery fabric, most often via rings sewn on the underside of the skirt that were drawn up with cording to create puffs at the back and side of the dress. The puffs of fabric rested on full petticoats to create the still expansive base of the silhouette; its real shift was one of weight, giving as it did an overall lighter impression of the body within.

In the 1780’s the chemise became popular, this was a lightweight gown made from fine fabric gathered in at the natural waist by a sash. However, this gown still emphasised the waist. Furthermore, by the end of the eighteenth century, a different silhouette was beginning to emerge, intended in imitation of classic Greek and Roman dresses. The dresses took a turn from hard geometric carapace into a soft, thin chemise of cotton or linen that grazed the natural female form and almost fully revealed the breasts.

Rococo emerged in France in the 1720s and remained the predominant design style until it fell out of fashion in the 1770s. Excessively flamboyant and characterised by a curved asymmetric ornamentation and a use of natural motifs, Rococo was a style without rules. A smart and refined court culture called Rococo flourished in France after Louis XV came to the throne in 1715. Along with Rococo the leader in woman's fashion became more of a solidified statutes as international trendsetter. The essential spirit of Rococo era women’s clothing is expressed in its elegance, refinement, and decoration.

This is a typical Rococo period women's dress, "robe à la française". The ensemble shown here consists of a gown, the petticoat much like what we would call a skirt today, and a stomacher made in a triangular panel shape. The gown opens in the front, and has large pleats folded up at the back. All this would be worn after formed with a corset and pannier, which acted as underclothes. Until clothing accepted drastic changes with the 1789 French Revolution, rich outfits, such as is shown here, were worn.

The fan-shaped trims on the gown on the left.

Rococo S-Shaped.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tracing Chinoiserie: From 18th-Century France to CHUCUI PALACE’s Modern Craftsmanship

French Chinoiserie is a distinctive European decorative style that rose to prominence in the 17th and 18th centuries, born from the West’s romanticized imagination of Eastern culture. Highly favored by the French court from the reign of Louis XIV to Louis XVI, it indirectly inspired and influenced the emergence of Rococo art. During this period, large volumes of Chinese porcelain, lacquerware, silk, and other crafts entered the European market, sparking the imagination of artisans and artists. French craftsmen did not merely imitate Chinese art, but reinterpreted it through a Western aesthetic lens, integrating it into local artistic design. By the mid-18th century, Chinoiserie had reached its zenith across Europe, with royal and aristocratic patrons pushing the style to its peak — exemplified by the interiors of Petit Trianon in Versailles, a hallmark of this aesthetic.

As the 19th century unfolded, Chinoiserie continued to be reinterpreted across cultural domains. With globalization and deeper cross-cultural exchange, French Chinoiserie regained attention in the realms of luxury, fashion, and contemporary art, becoming a major source of design inspiration today.

Lingering Garden Wallpaper Mural on Sisal by York Wall Covering

An illustrative example is Lingering Garden Wallpaper Mural on Sisal by York Wall Covering, the oldest wallpaper company in the United States. Using soft tones typical of Chinoiserie, the work evokes a serene and mysterious Eastern garden landscape. Set against a white sisal (dragon beard grass) wallpaper base, the design features green, blue, and pink elements, with deliberate emphasis on blank space. The composition aims for natural flow and organic form. Unlike traditional gongbi-style paintings, the color treatment presents subtle Chinoiserie-style layering and Western-style shadowing, enhancing its decorative appeal while still retaining the linear precision and textural depth found in fine brushwork.

CHUCUI PALACE “Kirin in Clouds” Brooch

A leading example of Chinoiserie-style jewelry is the Kirin in Clouds brooch by CHUCUI PALACE. This work innovatively combines Chinese gongbi painting techniques, traditional Chinese carving, and Western-style gemstone setting. The composition is flowing, vibrant, and complex — masterfully weaving together multiple elements through interlacing, wrapping, and embellishment, establishing a refined balance of focus, spatial relationships, and layered dynamics. It adapts the traditional Chinoiserie totem of the kirin (mythical creature) to a contemporary context while honoring its symbolic reverence in Chinese culture.

The design abstracts and refines traditional cloud patterns into elegant, fluid curves that intertwine with the kirin, enhancing its sense of divinity and nobility. The cloud motifs interact with flowers and the kirin through shifting spatial layers, material contrasts, and intricate lines and surfaces — creating a rich, dimensional texture.

Color is applied through traditional Chinese gongbi heavy-paint techniques, using unified and nuanced gradients for a soft, delicate wash, while selective contrasting tones generate visual tension. The resulting kirin is ethereal and elegant — resonating with the maximalist, decorative nature of traditional imagery, while also aligning with a thoughtful modern reinterpretation.

Gien “France Chinoiserie Faience, 3 Garniture Items”

Another example comes from Gien, a famed French faience (tin-glazed earthenware) manufacturer active from the late 19th to early 20th centuries. The France Chinoiserie Faience, 3 Garniture Items set consists of two lidded decorative jars and a large lidded bowl with base. The pieces feature a rare light turquoise background with multicolored enamel decorations and blue-white glaze accents. This color palette, influenced by Chinese celadon and famille rose porcelain, was uncommon in European ceramics of the 18th and 19th centuries.

The central lidded bowl is flanked by Buddhist lion handles and topped with a knob shaped like a Taoist deity or monk. The base features heart- and scroll-shaped openwork carvings, a technique popular in 18th–19th century European ceramics and furniture, echoing Chinoiserie’s ornate style. The side jars feature birds perched on branches, blooming chrysanthemums and plum blossoms, all set against a blank background to highlight the main motifs. Buddhist lion handles with attached rings further express European aristocracy’s fascination with the exoticism of Eastern culture.

French Chinoiserie is not merely a romanticized recreation of Eastern culture from the 17th–18th centuries — it has continued evolving from the 19th century to the present, becoming a timeless aesthetic that spans decorative arts, architecture, fashion, and jewelry design. Its distinctiveness lies in reinterpretation rather than replication, using cross-cultural design language to imbue Eastern imagery with renewed life across eras.

York Wall Covering’s Lingering Garden reimagines Chinoiserie through the lens of contemporary spatial aesthetics; Gien’s faience set reflects European nobility’s admiration for Chinese ceramic craft; and CHUCUI PALACE’s fine jewelry extends and elevates Chinoiserie’s core spirit within luxury design. In today’s globalized world, Chinoiserie is no longer a one-way cultural transplant — it is a deeply integrated aesthetic expression. It maps the history of East-West artistic exchange while serving as a vibrant source of creative inspiration across time and cultures.

0 notes

Text

The Timeless Appeal of Antique Cufflinks

Cufflinks date back to the late 17th century during the reign of King Louis XIV. Originally, men used ribbons or buttons to fasten their cuffs, but over time, these accessories evolved into stylish pieces crafted from precious metals and adorned with intricate details.

The Rise of Cufflinks in the 19th and 20th Century

The 19th century saw these elegant fasteners become a fashion statement, particularly under the influence of Edward VII, the Prince of Wales. His preference for Fabergé designs featuring colorful gemstones set a trend among high society. By the early 20th century, Art Deco and Art Nouveau styles further elevated them into miniature works of art.

Materials and Craftsmanship

These collectibles are crafted from a variety of materials, including:

Gold & Silver – Popular choices for luxury designs.

Platinum – A symbol of prestige and durability.

Enamel – Used to add vibrant colors and patterns.

Mother-of-Pearl & Gemstones – Often featured in elegant designs, reflecting different artistic movements.

Styles and Designs Through the Eras

These accessories often mirror the design trends of their respective periods:

Victorian Era – Romantic motifs, floral engravings, and sentimental inscriptions.

Art Deco – Geometric patterns, bold colors, and symmetry.

Art Nouveau – Nature-inspired designs with flowing lines.

Collecting and Investing

Beyond their aesthetic appeal,antique cufflinks are valuable collectibles. Many pieces from renowned brands like Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, and Tiffany & Co. are sought after by collectors worldwide. Their craftsmanship, rarity, and historical significance make them great investments.

Where to Buy?

For collectors and enthusiasts, online platforms like Bidsquare offer a curated selection of authentic antique and historical designs. These live auctions present an opportunity to acquire unique pieces with rich histories.

Conclusion

These timeless accessories are more than just fashion statements; they represent history, craftsmanship, and personal style. Whether you’re a collector, a history enthusiast, or someone looking to add a touch of elegance to your wardrobe, investing in antique cufflinks is always a refined choice.

0 notes

Text

A History of Ballet

Ballet is a formalized and highly stylized dance in which a dance technique called the “danse d’ecole” combines with artistic components such as music, costumes, and a musical stage. It has fluid and precise movements, classic positions, and techniques that evoke emotions and tell a story.

This dance form has its roots in the Italian Renaissance, when it emerged as a court entertainment. Indeed, the terms “ball” and “ballet” come from the Italian word “ballare,” meaning “to dance.” After King Henry II of France married Catherine de Medici, an Italian noblewoman, ballet spread to France.

During ballet’s early days, dancers wore brocaded costumes, headdresses, masks, ornaments, and pantaloons that were aesthetically appealing but restrictive and difficult to move in for dancers. Dancing shoes were also essentially formal dress shoes. The dances involved elements such as costume, decor, dance, music, poetry, and song, helping popularize “ballet de cour,” a type of ballet performance.

During the 17th century, King Louis XIV of France helped transform ballet. A passionate ballet dancer himself, he supported the establishment of the Academie Royale de Danse in Paris, the Western world’s first dance institution. This transformed ballet from a hobby into an activity requiring professional training. King Louis XIV’s personal trainer Pierre Beauchamp aided in codifying ballet’s five basic foot positions still used by dancers today.

Court ballet dances grew in size, grandeur, and opulence, prompting organizers to host events on elevated platforms for increased audience viewing. In 1681, dances shifted from courts to stages. The Le Triomphe de l’Amour, a French Opera, included ballet in stage performances, introducing an opera-ballet tradition in France.

In the 18th century, Jean Georges Noverre, a French ballet master and dancer, rejected the opera-ballet idea, claiming that ballet could stand independently as an art form. He said that characters should reveal relationships between them through dramatic and expressive movements. This introduced “ballet d’action,” a dramatic storytelling ballet style that was the predecessor of 19th-century narrative ballets.

The 19th century saw ballet become a romantic dance that incorporated theatrical illusions and became fashionable. En pointe dancing, that is, dancing on one’s toe tips, became the standard for ballerinas. Also, a calf-length, full tulle skirt, called the romantic tutu, came into being during this period.

Ballet spread to other European regions, including Denmark and Russia in the late 19th century. Russian composers and choreographers helped elevate ballet to new heights. Marius Petipa, a French-Russian pedagogue and ballet dancer, was a famous ballet choreographer who developed ballet masterpieces that attract audiences to this day.

His work focused on displaying classical techniques, including high extensions, pointe work, and movement precision. “Swan Lake,” “The Nutcracker,” and “The Sleeping Beauty” are some of Petipa’s timeless works.

The classical tutu, shorter and more rigid than the romantic tutu, came about during this period. This new clothing aimed to reveal the ballerina’s legs and show audiences just how complicated some of the footwork and movements were.

Ballet became a mainstream dance in the 20th century. Serge Diaghilev, a Russian theater producer, helped form the “Ballet Russes,” a group comprising some of Russia’s most experienced and talented choreographers, composers, dancers, designers, and singers. The group toured Europe and America, performing various ballet dances.

In the 1930s, ballet started growing in popularity in America following some of Diaghilev’s dancers leaving his company to settle and work in the US. These dancers helped set up the New York City Ballet and the San Francisco Ballet School, institutions famous for firmly establishing ballet in America.

George Balanchine, a Russian emigrant and New York City Ballet co-founder, expanded classical ballet into a genre called neo-classical ballet, a type of ballet that uses movement to express music and illustrate human emotion and struggles. Contemporary ballet has many different sides. It mixes classic styles, traditional stories, and modern dance concepts to create what we know as ballet today.

0 notes

Text

Kroashent Character Spotlight: Anjela du Berry

For August/September, I'm taking on a little side project, cleaning up and finishing some of the placeholder characters on the Kroashent WorldAnvil. Oftentimes, inspiration strikes suddenly, leaving me with a lot of unfinished concepts that don't quite fit cleanly into the mix. I'll be returning to answering Q+As soon (questions are always open and welcome) and writing the next chapters of the book. In the meantime, working on a lot of commission work, so this is something of a side project when the tablet is charging.

------------

Val's Notes: Anjela du Berry, the self-proclaimed "leader" of the Dragons of Dreger, began as a guest character, an informal "trade" between my world of Alvez and the world of Nova, the setting of the artist Ivanks. Adapting Angela Goldenstar from her original world to Alvez proved to be a fun challenge, and of the "Dragons of Dreger" Anjela du Berry is probably my favourite to draw and write.

Anjela is the quintessential noble. Well spoken and well educated, but a little snobbish, eccentric and kind of a brat. She's brave and loyal, but used to the finer things in life and getting her way. She is from a powerful family, the niece of the King of Gallia, Phillipe le Fortune, and the second cousin of Enora de Chinon.

I wanted to make sure that she, and all "Alvez-ized" characters are not just palette-swaps, but their own characters entirely. I tried to maintain Angela's teal and blue palatte, but added her navy blue coat for more prominence, and give her the air of an ancien regime fencer and bon vivant. Like her cousin, Anjela sort of threw a wrench in my inspirations, speeding along my shift from a High/Late Middle Ages High Fantasy (1341-1365 CE) towards a more eclectic and anachronistic Clockpunk setting, drawing from wider range of inspirations to give Alvez its own unique feel, drawing aesthetics from the Musketeers of Louis XIV, the Napoleonic Wars, the Belle Epoque and 19th Century Breton fashion. Anjela specifically was meant to evoke the first of these, with a distinctly "musketeer" vibe.

I am very happy with the direction the aesthetics of Alvez have taken, and sometimes inspiration can strike from unlikely places. Also, if you like in depth well-crafted worlds and fleshed out characters, be sure to check out Ivanks' "World of Nova" series: https://www.deviantart.com/ivanksmw

0 notes

Text

The Story of Christian Louboutin’s Red Sole

DATE: 07/15/2022

What if I told you that the story of Christian Louboutin’s red sole started with…nail polish? With simple beginnings in 1991, Louboutin was about to launch a trademark look for the fashion industry, and it came from simple inspiration—and a little luck. Here’s the story behind Louboutin’s red sole, plus a few more reasons to love his heels as much as I do!

What inspired the red heel?

Tell the truth: when you catch a flash of Christian Louboutin’s trademark red sole while, say, out for a walk, what images pop into your head? Luxury? Royalty? Riches? Well it makes sense, since red heels have quite the royal history, dating back to French monarchy and in particular, King Louis XIV.

As the story goes, Louis’ younger brother Philippe d’Orléans – who for some reason was raised as a girl – was out walking the streets of Paris when his heels became stained with a red color. Attracted as he was to the look, he went home and is said to have painted all his heels red, only for his older brother to adopt the style himself.

Soon, the red heel would gain a permanent place in history thanks to Louis’ own narcissism, which saw him pass an edict that meant only nobility could wear heels, and only allowed those in his favor to wear red heels at that—apparently, the higher the heel, the more favored the wearer.

In fact, according to Philip Mansel – a historian with knowledge on the subject – the color red “demonstrate[d] that the nobles did not dirty their shoes”, and impressed upon the lower classes the idea that noble-persons “were always ready to crush the enemies of the State at their feet.”

Not that it lasted—soon the style fell out of fashion with the French Revolution and Marie Antoinette’s beheading, where she has been recorded as wearing a pair 2-inch heels to the guillotine.

While red heels had become unpopular for some time afterward – so much so that the phrase “red-heeled” was for a while considered derogatory in the UK – we know now that this ‘royal’ and dramatic history has nothing to do with how Christian Louboutin came to build his brand identity around the eye-popping red sole we know today!

Red Soles and Nail Polish

In 1993, after being in business for two years, it is said that Christian Louboutin released his latest collection of shoes a few weeks late. The idea had been to create a shoe inspired by close acquaintance (and party buddy) Andy Warhol’s painting, Flowers—and yet when the prototype arrived from Italy, there was something missing.

Certainly, the pink-stacked heel and large cloth blossom looked like the design Louboutin had drawn, and yet according to the designer, “the drawing was still stronger and I could not understand why.”

Enter, the red sole of fate! Looking around for inspiration, the blank, black sole of the shoe staring at him in the face, Louboutin noticed an assistant in his office painting her fingernails red. Without asking – so we can assume – Louboutin grabbed the bottle of red varnish, polished the sole of one of the shoes and thought: “This is the drawing!”

So were Louboutin’s red soles born!

When, in the years since, Christian has been asked about the importance of the red sole, he has been quoted as saying, “The shiny red color of the soles has no function other than to identify to the public that they are mine. I selected the color because it is engaging, flirtatious, memorable, and the color of passion.”

Louboutin is certainly known to be passionate about his red soles, which he registered in 1997 with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office—a move that would later come in handy in a court case against Yves St. Laurent when the design house delivered a collection featuring their own version of Louboutin’s red soles.

Thanks to the existing popularity of the heel, and because of the drama which ensued when YSL was accused of copying Louboutin’s signature, today Louboutin’s red soles are as iconic to his brand as Chanel’s interlocking C’s—and only come in one shade: Pantone 18-1663 TPX.

0 notes

Text

the disclaimer that I am not a historian or linguist or anything of the sort don't entirely believe the shit i say until you check yourself k thanks

California -- around the time California was 'discovered' the novel Las Sergas de Esplandián by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo was popular. Some Spanish explorers thought the Baja California peninsula resembled the Island of California described in the book and the name just spread from there. They didn't figure out the name came from the book until the 1860s tho, which is neat.

An excerpt from the book (translated into english, it's just from the etymology of California wiki);

"Know, then, that, on the right hand of the Indies, there is an island called California, very close to the side of the Terrestrial Paradise, and it was peopled by black women, without any man among them, for they lived in the fashion of Amazons. They were of strong and hardy bodies, of ardent courage and great force. Their island was the strongest in all the world, with its steep cliffs and rocky shores. Their arms were all of gold, and so was the harness of the wild beasts which they tamed and rode. For, in the whole island, there was no metal but gold."

–Las Sergas de Esplandián, (novela de caballería)

Colorado -- if I remember right it comes from a Spanish words that means 'ruddy', it is called that because of the red dirt found in some places in the state. It didn't actually get the name until 1861 though, so they also could have just picked something.

Delaware -- it was named after Thomas West, Lord De La Warr, I genuinely don't know what he did to get a place named after him.

Florida -- Juan Ponce de Leon and his crew showed up in Florida around Easter and it has something to do with that, but it just means 'full of flowers' and good observation skills Juan.

Georgia -- after George II, he authorized it that's about it.

Idaho -- the fun one, Mr. George M. Willing told Congress it was an indigenous word meaning "gem of the mountains". It Does Not. He invented the word Idaho, got a state named that and by the time they figured out he was lying it was too late.

Indiana -- even after it became a state most of its land was held by indigenous peoples, who obviously had their land taken as time went on, but Congress went "yeah land of the Indians, Indiana cool".

Louisiana -- named after Louis XIV (14), I don't think he did anything to have it named after him besides be the king of France 👍 Maryland & Maine -- they're actually named after the same person! Charles I wife Queen Henrietta Maria of France. Maryland came from the name of the charter "Terra Maria", anglicized to Land of Mary, and then eventually Maryland. Maine was named after Maine the province of France where Henrietta Maria's private estate was.

Montana -- Mountain in Spanish. Thanks for coming to my ted talk.

Nevada -- it means snowy, I like to imagine some Spanish guy looked at the Sierra Nevada mountains went "yeah it's snowy up there" and they called it a day.

New Hampshire -- Some of these really are self explanatory, the guy who founded it was from Hampshire.

New Jersey -- Duke of York was given the recently conquered New Netherlands went 'wow this is great, I want to share with my friends :)' broke off what's now New Jersey gave them to his friends one of said Friends just happened to be in charge of Actual Jersey. New Jersey.

New Mexico -- everything i've read said it's not actually named after Mexico the state OR Mexico the country so idk where they got New Mexico from but it certainly was not the first.

New York -- English conquer New Netherlands, Charles II names it after his brother James the duke of York and give it to him.

North Carolina & South Carolina -- Carolina was named after either Charles I or Charles II, you get to pick. I still think we need to establish a third Carolina called "Carolina slightly to the left" in honor of the current king Chuck.

Pennsylvania -- William Penn founded it, and that's the entire story there.

Rhode Island -- when exploring the America's it was 'assume island until proven otherwise' and the Dutch explorer Adrian Block saw the red clay on the shore and named it "Roodt Eylandt" (red island) and Roodt somehow became Rhode.

Vermont -- Samuel De Champlain founder of Quebec City and governor of New France meandered into vaguely Vermont and went "that's a green mountain" (vert mont) and it stuck

Virginia & West Virginia -- Elizabeth the first, girl boss of all time, never got married and they picked that thing about her to name a place after cause men smh

Washington -- After George Washington, supposedly it was going to be named Lincoln originally and then they went "nah because the capital is going to be called Columbia" and then the capital was not called Columbia and now we all have to say "Washington state" to specify.

I love US state names so much, the categories consist of:

some king/queen (Virginias, Carolinas, Georgia, Maryland, Louisiana, Maine)

new + place that already exists (New Jersey, New Hampshire, New Mexico)

idk some dude (Delaware, New York, Pennsylvania, Washington)

1-2 word description of the place (Rhode Island, Florida, Vermont, Nevada, Colorado, Montana, Indiana)

A French/English/Spanish Guy Really Fucking Up The Pronunciation Of An Indigenous Word (more then can be named)

Snatched Directly from the 1510 romance novel Las Sergas de Esplandián by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo (California)

just fucking making some shit up and getting away with it ig (Idaho)

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historically Accurate POTC Designs, Maybe??

Tried drawing some historically accurate Pirates of the Caribbean designs, with my best effort(s?) to keep the spirit of the original costumes!

Research rabbit holes below:

I set the clothes in the late 1720's, 1728-1731. At this time, coats were very full—almost skirt-like—with big cuffs, and the waistcoats sometimes had long sleeves!

For Will, I decided to give him just a waistcoat since most of his costumes in the movie don't have an overcoat, and it makes more sense for a blacksmith, I think! I also decided not to give him a wig since I don't think he would be wealthy enough or be able to work with one.

For (Captain) Jack, I really just wanted to give him shoes with red heels. They were popular in the 17th century, but carried over to the early 18th! Wearing them meant you were in favor with King Louis XIV (who ruled at the time) and were rich enough to wear the color red. Since Jack is obviously none of those things I thought it’d be funny—he probably stole them. The T on his hand was supposed to be the equivalent to the P brand Jack has in the movies. Branding was a thing, just not for pirates! A T burned on the hand was for “thief.” Usually brands were like a warning, and if the offender committed another crime then they would be hanged—pirates, however, didn’t get a second chance.

For Elizabeth, her dress was hard to research. Technically the popular gown at the time was a Robe Volante, but I don’t like the way it looks so I found a different one haha :D What I could find from a few paintings was what apparently is called a “round gown” and was often worn with some sort of belt or ribbon thing at the middle. Not sure what that part is called, maybe a girdle? Technically, a mantua would be closer to the purple-red gown Barbossa gives Elizabeth, since it has fabric bunched up in the back, but I thought a different style could work too.

Elizabeth’s pirate outfit is just based off of what I could find for general 18th-century sailor’s clothes, which were difficult to find for the 1720s in particular, but didn’t seem to change much throughout the decade. However fashionable, boots (sadly) weren’t actually worn by pirates, and most sailors would go barefoot or just wear the current fashionable shoe at the time! She would also probably be wearing a knit hat, but I thought the tricorne was too iconic to take away.

And, lastly, for Norrington! He’s wearing a Ramillies wig (named after the battle of Ramillies in 1706) which was the style for people in the military, or really for anyone who couldn’t wear a full periwig (the really big curly wigs.) And for his clothes, since British Navy Uniforms weren’t introduced until 1748, I just put him in blue and gold.

And that’s it! I’m only a very amateur fashion history enthusiast and could be wrong about a lot, so if anyone knows anything about 1720-30s fashion or anything like that feel free to let me know about any mistakes or other interesting historical facts!

#potc#potc fanart#character design#18th century#pirates#historical fashion#pirates of the caribbean#james norrington#elizabeth swann#jack sparrow#will turner#18th century fashion#1720s#pirate#these literally took forever :)#I forgot how leg proportions work#my art#fashion history art

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shoelaces

[Detail of the Meagre Company, oil on canvas, c. 1633-1637, by Frans Hals, via Wikimedia.]

While shoelaces had been fairly common in the 17th century by the beginning of the 18th century they had been surpassed in popularity by buckles.

[Detail of Declaration of Independence, oil on canvas, c. 1819, by John Trumbull, via Wikimedia.]

The most common style of men's shoe in the 18th century was black leather buckled shoes, typically with a small heel (see above). Even fashionable men often wore these simple black buckled shoes, though they may accessorise them with ornate buckles rather than plain ones. Even on men's high heels we see buckles replacing ribbons at the turn of the century.

[Left: Detail of Charles II of England, oil on canvas, c. 1670-1675, by Simon Pietersz Verelst, via Wikimedia.

Right: Detail of Louis XIV of France, oil on canvas, c. 1700-1701, by Hyacinthe Rigaud, via Wikimedia.]

During the first few decades of the 18th century shoe ties remained popular alongside buckles in women's footwear. However extant examples of buckled shoes outnumber those of laced shoes, though this may in part be due to shoes being converted to accommodate the fashionable buckle.

[Left: Shoes with ribbon ties, leather & brocaded silk, c. 1730s, via V&A (accession number: T.197&A-1927).

Middle: Buckled shoes, painted kid leather & silk, c. 1760s, via V&A, (accession number: 270&A-1891).

Right: Shoes with eyelets, leather & silk, c. 1700–1720, via The Met (accession number: 2009.300.1480a, b).]

In their description for the shoes on the right the Met writes:

Most aficionados of historic fashion are well acquainted with 18th century ladies' shoes in the classic buckled latchet style, as they survive in fairly good number. The predecessor of these - latchet ties shoes - are however fairly scarce in good unaltered condition. In order to extend their life as fashionable footwear, latchet tie shoes were frequently modified to accommodate a buckle.

By the 1780s shoe strings in menswear was so unpopular in mainstream Parisian fashion they were seen of being indicative of sodomy. In his article Commissioner Foucault, Inspector Noël, and the “Pederasts” of Paris, 1780-3 Jeffrey Merrick explains how Foucault and Noël used men's clothes to identify them as suspected sodomites. These men wore “some combination of frock coat, large tie, round hat, small chignon, and bows on the shoes.” Merrick speculates that these men were using fashion to signal to each other. Understandably when questioned by police men would deny such a purpose.

In England men who wore shoe strings were seen as effeminate. In their issue of 6-9th of December 1788 the St. James's Chronicle or the British Evening Post describes the "Jessamy or Petit-Maitre" (both terms for effeminate men) as follows:

The Jessamy or Petit-Maitre are so nearly allyed that the Rules that serve for one will do for the other-These He-She Beings should always take particular Care in the Decoration of their sweet Persons-Their Clothes should be cut to the very extreme of the Mode, their Hair dressed particularly nice, even if they sit two Hours under the Hairdresser's Hands, and while under the Operation, are to take out their Pocket Glass and give the Hair Dresser Instructions form Time to Time-When they walk the Streets of London, they are to make short Steps, as was formerly the Fashions of the fine Ladies, wear Shoe-Strings-paint their Faces, and be alarmed at every little Noise they hear in the Streets. In short it will be necessary to keep up their Reputation that they assume a Behaviour more feminine than masculine-and by all Means to imitate the Behaviour and Looks of the Females in the Days of their Great Grandmothers. Such Conduct will stamp their Characters in the Eyes of their Brethren.

[Sir John Coxe Hippisley, oil on canvas, c. 1779–80, by William Pars, via Art & the Country House.]

However by the late 1780s shoe strings were already starting to have a resurgence, in part due to their cost. With shoe strings being cheaper than buckles many men started to adopt them in spite of the associations with effeminacy. On the 21st September 1786 The Times reported:

The shoe-strings are now the fashion wit all the barbers boys, hair-dressers, and waiters, in London. The charity schools have also adopted them, as they are much cheaper than buckles. A man of sense, and a real man of fashion, has never yet dishonoured his instep with such a piece of mean folly.

And on the 12th of July 1787 The Times suggests that when a "tolerably well-dressed man wears them, the general conclusion is, that his buckles are in pawn." However in spite of the comparative cheapness of shoe strings the association with effeminacy persisted.

One intriguing instance of the cultural perception of shoe strings comes from a 1789 adaptation of the Tempest that opened on Drury Lane on Tuesday the 13th of October. The play included an epilogue written by General John Burgoyne. The epilogue fear-mongers the growth of effeminacy in England writing that "we may lack men, though over-run with males." Burgoyne depicts the middle class John Bull as an effeminate "He-Miss" Milliner:

Yet John sometimes his shape and sex degrades, And stoops to rob his sisters of their trades. Six feet in height, with sinews of an ox, Shoulders to carry coals, and fists to box,- Behold-O shame!-a thing of whip and hem- A He-Miss Millener-"Your orders, Me'm?- "Rouge, lipsalve, chicken gloves, perfumery, "Hair cushions, gauzes, bustles?-HE! he! he!"-

Burgoyne then shifts to men "of higher bearing";

Still Falstaff's men, all radish and cheese-paring!- Oh! could he sketch some figures that one sees- Tied up with strings at shoes and strings at knees! So thick the neck-cloth, and the neck so thin! He'd swear they bore a poultice for the chin:- And lest the cold the adjacent ears should harm, See half a foot of cape to keep 'em warm; While the stiff edge, for better purpose made, Rubs off the whiskers it was form'd to shade. With eyes of fire that vie with snuffs in sockets, And hands distress'd for want of waistcoat pockets: The crutch of levity directs their gait; And wanghee bends beneath their wangling weight.

On the 14th The World praises the epilogue as a "pleasant satyr upon modern modes" noting in particular;

the perversion of his good parts into effeminate pursuits-the Man-Milliner-the strings at shoes, and strings at knees-the stiff stand-up cape, "chasing the whisker it was meant to hide"-the waistcoat pockets-were all perfection, in what is the Epilogue's best praise, knowledge of effect, and strong accomplishment of it.

In contrast to Burgoyne's depiction of him as a "He-Miss Millener" John Bull, a personification of England (much like Uncle Sam is to the US), was typically depicted as a plainly dressed middle class Englishman. Some satires such as James Gillray's Politeness would compare the masculine English John Bull to the effeminate French archetype. Bull is depicted sitting with his legs open, wearing blue, red and buff with short un-powdered hair and wearing boots. The Frenchman is sitting with his legs closed, wearing pink and green (colours that were considered effeminate) with white powdered hair tied back with a ribbon and wig bag. However he is wearing bucked shoes.

[Politeness, hand-coloured etching, c. 1779, copy after James Gillray, via The Met.]

Another example of a typical depiction of John Bull can be seen in The Honest Pickpocket published by William Holland which comments on the clock tax enacted by the Pitt government. The cartoon depicts Prime Minister William Pitt taking a watch out of John Bulls pocket. Pitt is saying "Don't be alarmed, Johnny, I only want to see whether it is Gold or Silver - you know there is a great deal of difference between Half a Crown and Ten Shillings."

In this anti-Pitt satire, Bull is depicted again in blue, red and buff with un-powdered hair, however this time he is wearing buckled shoes. Pitt in contrast is depicted in green with powdered hair tied back with a ribbon and wig bag. His shoes are fastened with strings.

[The Honest Pickpocket, hand-coloured etching, c. 1797, published by William Holland, via The British Museum.]

However in An Enquiry Concerning the Clock Tax Pitt is depicted in blue and red with buckled shoes. The satire is playing on a pun, the clock tax was a tax of the time keeping devices but in the 18th century stockings sometimes had decorative embroidery known as clocks. In the print a delegate "from the worthy and respectable Society of Hosiers" asks Pitt "to know whether your Honor means to extend the Tax to Clocks upon Stockings." In contrast to Pitt the hosier wears not only stockings with clocks, but also shoes with strings as well as breeches with strings at the knees. Pitt is holding a quill labeled "Tax Pen", he is halfway through writing a list of taxes which includes "Shoe Strings", "Knee Strings" and "Hair Strings".

[An Enquiry Concerning the Clock Tax, hand-coloured etching, c. 1797, after George Moutard Woodward, published by S. W. Fores, via The British Museum.]

While this satire was clearly playing on the pun, it's not too far off what some were proposing. With the popularity of shoe strings increasing during the 80s the buckle makers were starting to get concerned for their livelihood and hoped a shoe string tax would combat the price difference. On the 22nd of November 1788 The Times reported:

The buckle makers it is said intend to petition for a tax on shoe strings by an eighteen penny stamp on each pair. This, although somewhat extraordinary, yet is in agitation, and might be easily effected.

With most of the buckle manufacturing coming out of Birmingham it was reportedly a risky move to wear shoe strings there. On the 28th August 1789 the Oracle reported:

At Birmingham, the man who dares appear with ribband-ties in his shoes, is certain not to pass current. He is instantly seized, his shoes taken off and cut to pieces; and no shoe maker can dare to sell him a new pair, unless he buys a pair of buckles first!

Much of the public was on the side of the buckle makers and against the shoe strings. On the 12th August 1789 the Oracle bemoans that "thousands of His Majesty's loyal subjects are now starving, from the introduction of the effeminate fashion of shoe-strings." On the 6th of November the Oracle reported that on "being asked by a Nobleman, why he had such an objection to Shoe Strings-His Royal Highness replied in these emphatic words-"

In the first place, I dislike them, for they look effeminate, are neither genteel or becoming; but give a certain air of meanness to the foot, which should be avoided. In the next place, I do not wear them, for it shall never be said of me, that any whim of mine has been instrumental in bringing the hard labouring Mechanic to Ruin!

A letter signed "Cheapside" published on the 5th January 1789 in The World was a bit more extreme suggesting that men who wore shoe strings "ought, in plain English, and with a good sufficient English cord, to be hanged". While Cheapside was concerned that the buckle makers were being "tied up from getting their bread" the true dislike of shoe strings and the men who wore them seem to be more due the their "intimations" that were "most disgraceful to manhood."

#to my amerev followers yes its the same General John Burgoyne he became a playwright after the war#fashion history#queer history

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Some 1690s (from top to bottom) -

ca. 1690 Beatrice Violante of Bavaria, Grand Princess of Tuscany by Bartolomeo Mancini (Museo Civico Pinacoteca Crociani - Montepulciano, Sienna, Toscana, Italy). From tumblr.com/roehenstart 1280X1492 @72 685kj.

ca. 1693 Comtesse de Balleroy by Nicolas de Largilliere (Aguttes - 6Dec22 auction Lot 48). From their Web site 2224X2798 @144 6Mp.

#1690s fashion#late Baroque fashion#late Louis XIV fashion#Beatrice Violante of Bavaria#Bartolomeo Mancini#curly hair#hair jewelry#cap#off shoulder V décolletage#lace modesty piece#notched over-sleeves#lace cuffs#Comtesse de Balleroy#Nicolas de Largilliere#wavy hair#cleft coiffure#V décolletage#over-dress#jeweled girdle#V waistline#jeweled clasps

167 notes

·

View notes