#kuramochi fusako

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

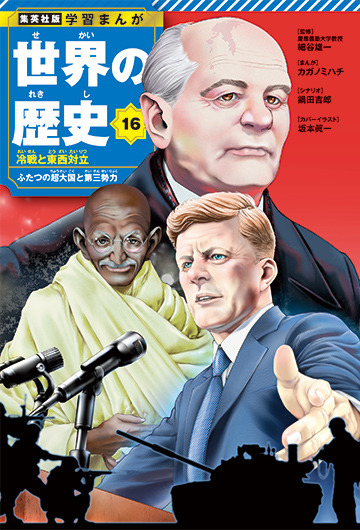

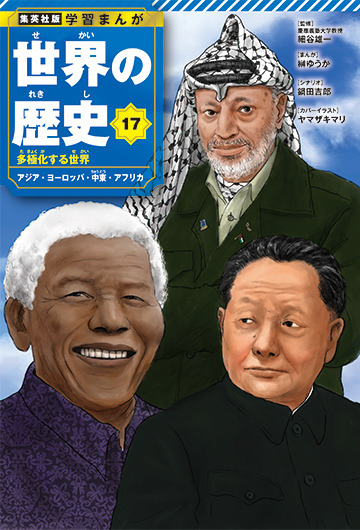

For Shueisha's 100th Anniversary, the cover art for all 18 volumes of the educational Manga World History were redesigned by popular manga artist:

Volume 1: "Kingdom" by Yasuhisa Hara

Volume 2: Hiroyuki Asada "Letter Bee"

Volume 3: Kohei Horikoshi "My Hero Academia"

Volume 4: "Gokusen" by Kozue Morimoto

Volume 5: Yuuki Tabata "Black Clover"

Volume 6: Fusako Kuramochi "Natural Cockoo"

Volumes 7 and 18: Posuka Demizu "The Promised Neverland"

Volume 8: Io Sakisaka "Ao Haru Ride"

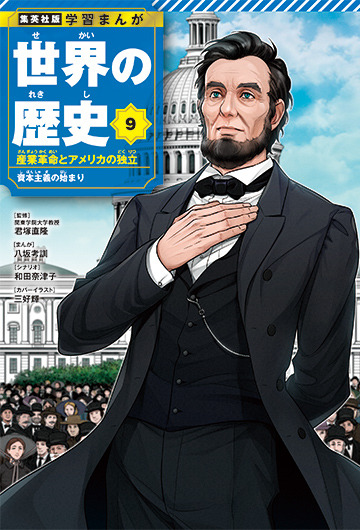

Volume 9: Teru Miyoshi "Moriarty the Patriot"

Volume 10: Hirohiko Araki "JoJo's Bizarre Adventure"

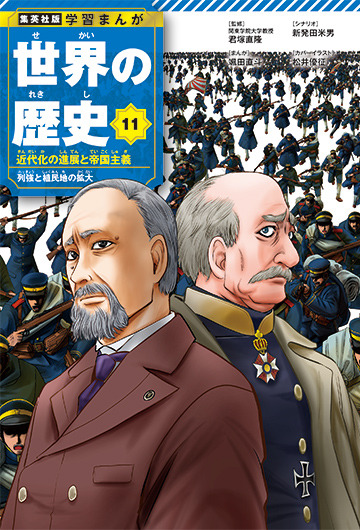

Volume 11: Yusei Matsui "Assassination Classroom"

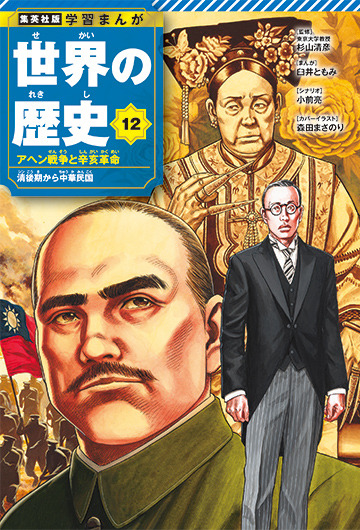

Volume 12: Masanori Morita "ROOKIES"

Volume 13: Noda Satoru "Golden Kamuy"

Volumes 14 and 16: Shinichi Sakamoto "Innocent"

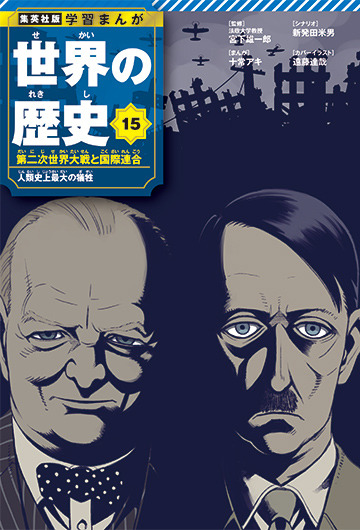

Volume 15: Tatsuya Endo "SPY×FAMILY"

Volume 17: Mari Yamazaki "Thermae Romae"

The pictures of all covers are here

#hara yasuhisa#asada hiroyuki#horikoshi#morimoto kozue#tabata yuki#kuramochi fusako#demizu#posuka demizu#io sakisaka#teru mmiyoshi#araki#araki hirohiko#matsui#yusei matsui#morita masanori#noda satoru#shinichi saka#shinichi sakamoto#tatsuya#tatsuya endo#mari yamazaki#history covers

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

#kuramochi fusako#obake tango#shoujo#caps#crying bc of these lines narration atmosphere everything#first read of the year

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

ルックバック (Look Back), Tatsuki Fujimoto カツカレーの日 (Katsu Curry no Hi), Keiko Nishi 天使なんかじゃない (Tenshi Nanka Janai), Ai Yazawa 天然コケッコー (Tennen Kokekko), Fusako Kuramochi ときめきまんが道 (Tokimeki Manga Michi), Koi Ikeno スラムダンク (Slam Dunk), Takehiko Inoue

#photosets#my scans#colors#Color Schemes#tatsuki fujimoto#keiko nishi#ai yazawa#fusako kuramochi#koi ikeno#slam dunk

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

100 m no Snap (1979) by Fusako Kuramochi

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

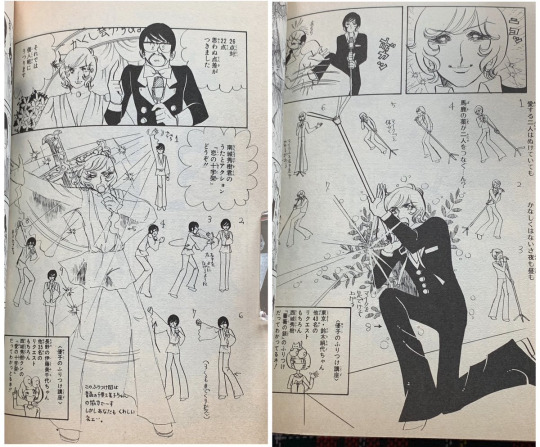

From 🎶 Itsumo Pocket ni Chopin (いつもポケットにショパン), Vol. 1, 1980 by Fusako Kuramochi (くらもちふさこ)

#vintage shoujo#vintage shojo#manga#vintage manga#retro shoujo#shoujo manga#Fusako Kuramochi#くらもちふさこ#Itsumo Pocket ni Chopin#clowns <3

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shoujo Manga's Golden Decade (Part 3)

Shoujo manga, comics for girls, played a pivotal role in shaping Japanese girls’ culture, and its dynamic evolution mirrors the prevailing trends and aspirations of the era. For many, this genre peaked in the 1970s. But why?

Part 1

Part 2

Follow the Trend

Before we move on to the third movement of the '70s, let's take a quick look at an essential characteristic of shoujo manga: its sensitivity to trends.

The early '70s were a confusing time for the industry. There was extreme freedom in certain corners, with Yukari Ichijo, Machiko Satonaka, and other prominent artists drawing very adult-like drama in shoujo magazines for very young girls. In contrast, there was also a lot of moralism. The fact manga wasn't taken very seriously meant magazines could get away with a lot since adults considered them terrible influences anyway. But, at the same time, since manga wasn't a respected medium, they were also prone to hysteria. Nothing illustrates this scenario better than the controversies surrounding "Harenchi Gakuen," the first full-length series by Go Nagai, who went on to become one of the most celebrated manga artists of the '70s.

Shameless! The nudity and erotic jokes in Go Nagai''s "Harenchi Gakuen" were a hit with kids and teens, scandalized parents and teachers, and made the shoujo industry chase after their own erotic hits.

Nagai, already a respected yet fledgling name in the industry, was recruited by Shueisha to be part of Shonen Jump's inaugural team in the late '60s. Jump, as any manga fan knows, is by far the biggest success story in manga's editorial history. However, back then, it was just a newcomer in a field dominated by Kodansha's Weekly Shonen Magazine and Shogakukan's Shonen Sunday. Go Nagai's series, whose translated name meant "Shameless High School," is Jump's initial smash hit and one of the titles behind its extraordinary ascent.

But "Harenchi Gakuen," a gag manga with erotic jokes, scandalized adults across the nation. The Japanese Parents and Teachers Association successfully led a Shonen Jump boycott, getting the magazine banned in several shops across the country and triggering a media circus. At the time, agitated journalists often accosted Go Nagai at airports and public events, aggressively pointing their mics at him, a consequence of manga-kas celebrity-like notoriety during that era.

Meanwhile, the reaction around "Harenchi Gakuen" did not intimidate other manga magazines. In fact, all of them were pursuing their own "harenchi"-like phenomenon and publishing stories with erotic dirty jokes. And yes, that included the manga magazines for little girls. In Ribon, male manga-ka Hikaru Yuzuki was responsible for the "dirty" manga series. At Weekly Margaret, Yuzuki also had a considerable hit with the high school comedy "Elite Kyousoukyoku," which, while not precisely "ecchi," had a tone reminiscent of Nagai's work. At Nakayoshi, the artist in charge of this type of content was none other than a pre-"Candy Candy" Yumiko Igarashi.

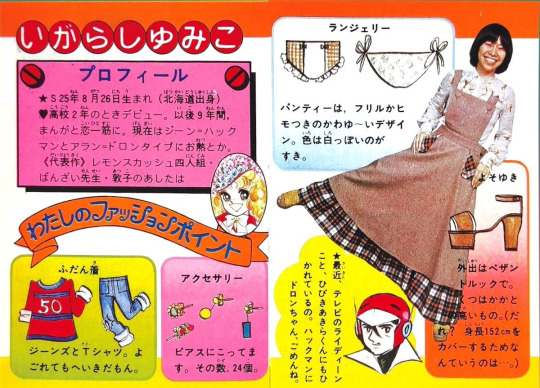

Before finding success with the smash hit "Candy Candy" manga, Yumiko Igarashi was the Nakayoshi artist in charge of recreating the "harenchi" phenomenon in the pages of the magazine. Above, in a good display of how public manga artists were in the '70s, Yumiko describes her panties as part of a Nakayoshi feature.

The "harenchi" phenomenon hinted at a shoujo field that wasn't yet wholly solidified and, therefore, was taking cues straight from the shonen segment, which would later become uncommon. But it also illustrates how the genre projects readers' dreams and preferences.

An example of this is one of Ribon's most popular series during the '70s, Yukko Yamamoto's "Miki to Apple Pie." Serialized between 1973 and 1976, this gag high school manga was full of absurd humor and nudity in the "Harenchi" vein. The twist is that it also had everything girls dreamed of.

The "apple pie" in the title was a reference to the lead character's favorite dessert during the time the American apple pie had just arrived in Japan and was considered the trendiest sweet. Miki Miyazawa, a popular and beautiful girl who served as the proxy for readers and was loosely modeled after talento Aki Aizawa, also loved astrology and the horoscope, and the romantic lead was a transfer student named Hideki Nanjo, who was a carbon copy of Hideki Saijo, the biggest popstar heartthrob of the '70s. Basically, "Miki to Apple Pie"'s central premise was "What if the popstars girls go crazy for was your silly gorgeous classmate?".

In fact, a testament to Saijo's popularity was how many shoujo manga romantic partners of the era used him as a model. Besides "Miki to Apple Pie," inserts of him were present in Satonaka Machiko's "Spotlight," Shigeko Maehara's "Kimi Iro no Hibi," Mayumi Yoshida's "Lemon Hakusho," among others.

With nudity, slapstick humor, and numerous references to trends and pop culture, "Miki to Apple Pie" became a sensation in the pages of '70s Ribon. The romantic lead, Hideki Nanjo, modeled after heartthrob Hideki Saiji, frequently performed impromptu renditions of popular hits from stars like Agnes Chan, Finger Five, Momoe Yamaguchi, Junko Sakurada, and, of course, Hideki Saiji himself. Full of shockingly offensive and scatological jokes, very little was considered off-limits, making "Miki to Apple Pie" a quintessential example of the distinctive '70s shoujo manga published during the peak of the "Harenchi" boom. It also serves as a perfect time capsule of its era, satirizing and commenting on everything popular at the time—from iconic products like the Panasonic Quintrix television and memorable TV commercials to celebrities, the toilet paper shortage during the Oil Shock, the Discover Japan campaign, and the widespread teenage girls' fascination with horoscopes. This manga elevated shoujo manga's trend obsession to unprecedented heights and mixed it with absurdity.

Saijo is a relic of the past, but shoujo echoing the trends of its time is a timeless characteristic of the genre. That's why most shoujo artists are women who are close in age to their readers: this sensibility to girls' desires is a vital component of the market. From the way the characters look to how they dress to even the shape of their eyebrows, everything is supposed to reflect its time. Therefore, to successfully create shoujo, one has to understand how girls perceive themselves and also how they want to be perceived. How they dress and look, but also how and what they dream of looking and wearing. What they aspire to and, above all, what they find attractive in the opposite sex.

It was precisely that sensitivity and this unique sense of what girls want and dream of that led to the creation of what is now the number 1 shoujo manga trope: the high school romance starring an unassuming, ordinary heroine. Leading the way was another group of artists that, while not as internationally celebrated as the Year 24 Group, are definitely equally as crucial to shoujo history.

The Otometique Fervor

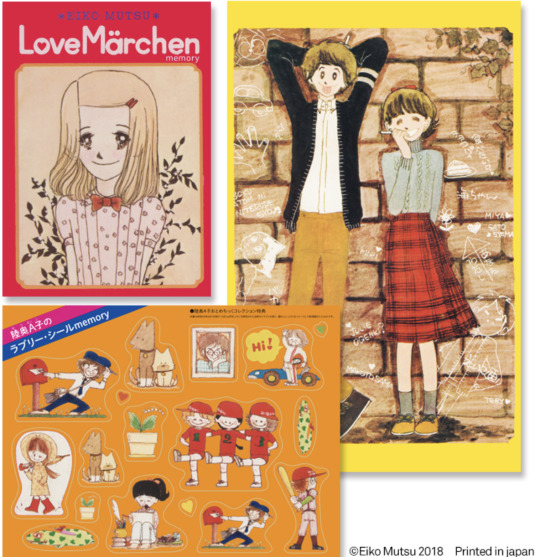

An "otometique" girl by Mutsu A-ko and some of the artist's popular furoku.

Yoshiko Nishitani, another of Shueisha's top shoujo artists of that era, is often credited as being the first to create a series around ordinary high school love. She did that in 1965's "Marie Lou," published in Weekly Margaret. "Marie Lou" was set in an American high school and had a very fashionable white girl as its lead. On her next manga, "Lemon to Sakuranbo" (Lemon and Cherries), she'd once again achieve immense success by bringing the teen romance closer to reality, using an ordinary Japanese high school as a backdrop.

While Nishitani pioneered this narrative style, the rise of more realistic, everyday stories gained momentum about a decade later. One catalyst for this was the "Otometique boom," a phenomenon that unfolded in the pages of Shueisha's Ribon magazine in the latter half of the '70s.

The term "Otometique" combines "otome," meaning "maiden" or a pure young girl, with the "-tique" (tikku in Japanese) suffix. A-ko Mutsu was the artist who spearheaded this movement.

A-ko made her debut in Ribon in 1971 at the age of 18. Her popularity skyrocketed four years later when her first short stories, led by "Tasogaredoki ni mitsuketa no" (What I Found at Twilight), were compiled into a tankobon that became a best-seller. This success elevated her status in Ribon, and soon her "otometique" style became the talk of the town.

Mutsu A-ko's art.

In contrast to the dramatic narratives of the "Satonaka-domain" faction, "otometique" stories adopted a more straightforward structure devoid of major plot twists and intense drama. Instead, they focused on modest love stories where the exhilarating moments were ordinary occurrences, like spotting a cute boy on the street or touching a crush's hand for the first time. While some stories included sad or supernatural elements, readers were captivated by the uncomplicated, heartwarming moments.

Ako's heroines were ordinary, unassuming schoolgirls, often characterized by shyness and insecurity. Different from extraordinary characters like Lady Oscar from "BeruBara" or the iconic Madame Butterfly tennis star in "Ace wo Nerae," Ako's protagonists were life-sized.

"Otometique" manga often incorporated romantic comedy tropes, such as chance encounters with cute guys on the way to school or the transformation into beauty after removing glasses. The happy endings typically featured a boy reciprocating the girl's love by accepting her as perfect and beautiful just as she was.

In otometique manga, girls were often in cute plaid and gingham check dresses and skirts, while boys were impeccably dressed in Ivy style, as seen in Mutsu Ako's art above.

While the stories may have seemed mundane, their distinctiveness lay in the meticulous attention to detail. As significant as the exploration of falling in love and discovering inner strength were all the visual details in "otometique" art. Girls had braids or long wavy hair and wore adorable clothes with plaids and gingham-check, as well as cute accessories. At a time when most Japanese girls still had Japanese-style rooms, "otometique" heroines had gorgeous Western-style rooms. They hung out in cozy cafes, made handmade goods, and ate tasty-looking sweets. Houses had French windows and balconies. Boys were tall, lean, with fluffy hair, and were always dressed impeccably in Ivy-style clothes. The "otometique" artists created an atmosphere that perfectly matched girls' aspirations at the time.

Girls often dreamed with having Western-style bedrooms like the ones in Otometique manga.

While Mutsu A-ko was the trailblazer, she was soon joined at the top by two other iconic artists, Yumiko Tabuchi, and Hideko Tachikake. Each of them had their quirks. Tabuchi, for example, often had college girls as her heroines, mirroring herself as a student at the elite, trendy Waseda University. While Tabuchi and A-ko preferred short stories, Tachikake had a penchant for longer series with a bit more drama. But they all had a similar aesthetic and relied on the charm of ordinary love.

The "otometique" phenomenon reflected the trends of the time and foreshadowed the emerging consumer culture that would swallow the country in the next decade. The sophisticated visuals attracted people of all ages, from elementary school-aged girls to highly educated women and men. Both the top public and private universities in Japan, Tokyo University and Waseda, respectively, had famous "otometique" clubs full of students who loved the genre and the style. The mangas were so trendy that they were often referred to as "Ivy mangas," in reference to the iconic Ivy style that was the catalyst of Japan's youth fashion, which was going through a second revival around that time.

While projecting an atmosphere that girls dreamed of, "otometique" also showcases '70s youth and girls' culture. Melancholic, simple love stories among young people were also the theme of the big folk hits of the time. Ivy or country fashion and long hair for men were the top fashion trends. Western-inspired ideals- in decoration, fashion, and musical taste- were pervasive. And creating subcultures and hobbies around consumption was the path society was taking. Simple life-sized stories as a narrative preference echoed the reality of Japan, which was stabilizing itself after decades of turbulence. These stories brought what the country was craving: comfort.

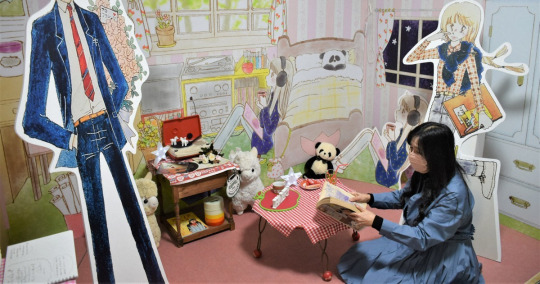

Above, a Mutsu A-ko's bedroom that lived in girls' imagination. Below, the room is recreated in a 2021 exhibition of Ako's art.

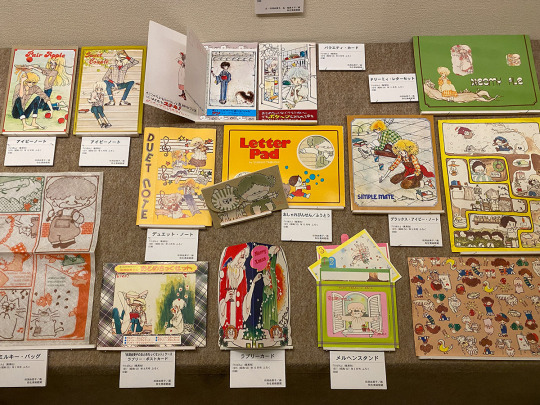

Meanwhile, the rise of consumer culture among young girls led to a "fancy goods" boom, with stores selling cute stationery, stickers, and small items popping up everywhere around the country. Illustrators and companies, eager to capitalize, spared no time in creating appealing mascots and drawings to adorn these goods, and it was in that period that Sanrio created Hello Kitty.

Ribon and Nakayoshi, which were "furoku" magazines, also benefitted. Furoku are extra gifts that come with the purchase of the magazines. And the "otometique" boom meant Ribon could include "fancy goods" -- like notebooks, stickers, letter sets, and small paper goods readers could assemble -- with the illustration of these highly sought-after artists. Most girls around Japan could only dream of Western-style rooms, a closet full of cute Ivy fashion, trips to trendy cafes, and homes with French windows. But they could recreate a bit of this sophisticated atmosphere by having letter sets, notebooks, stickers, and small accessories with A-ko Mutsu, Hideko Tachikake, and Yumiko Tabuchi's art. These popular furokus and the "otometique" stories were critical for Ribon magazine to surpass 1 million copies in circulation.

Girls admired A-ko, Tabuchi, and Tachikake not only as artists creating heartfelt stories with attractive atmospheres but as personalities. The trio, who were in their late teens and early 20s, closely resonated with their fans due to their proximity in age and shared interests. The readers were moved when Ribon featured an article in which A-ko Mutsu had the opportunity to meet and interview her favorite singer, the rock star Kenji Sawada, a prominent teen idol of that era. The positive response was so overwhelming that, a few issues later, Hideko Tachikake, an avid folk music enthusiast, also had the chance to interview her idol, Kosetsu Minami, the lead singer of Kaguyahime.

An otometique girl by Yumiko Tabuchi (left) and a collection of furoku illustrated by her as seen on a 2021 exhibition on her art.

The popularity of "otometique" peaked in 1977. By 1981, the boom had almost faded, and A-ko, Tabuchi, and Tachikake published their last works on Ribon in 1985. Tabuchi and Tachikake married and semi-retired, while A-ko successfully transitioned to manga for adult women.

Despite the end of the style, "otometique" permeated every corner of Japanese society. Its furoku and atmosphere were one of the bases for the almighty "kawaii" culture which now rules the country. The life-sized heroines and focus on mundane love stories and everyday emotions went on to become one of the main characteristics of the shoujo manga industry.

The Iwadate Domain

For years, the influence of "otometique" has been downplayed, one of the reasons why the movement is almost undiscussed in the West. However, in the last few years, best-selling books reminiscing the style were published, and exhibitions of A-ko Mutsu and Yumiko Tabuchi's works were big hits across Japan. A-ko, who moved back from Tokyo to her hometown in Fukuoka and never stopped creating manga, was recognized by the local prefecture as an honorary citizen and gained a permanent museum in the area, signaling her importance to the industry.

But while the "otometique" phenomenon happened on the pages of Ribon magazine, Mutsu, Tabuchi, and Tachikake weren't the only three attracting a massive audience to this type of real-life love story.

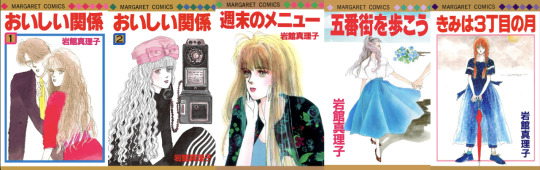

Mariko Iwadate's work was extremely popular from the late '70s to the mid-2000s. Above, a collection of her work from her Margaret era.

Going back to the research of sociologist Shinji Miyadai, three domains divided '70s shoujo. There was the "Moto Hagio domain," which included the Year 24 artists. The Hagio domain was more highbrow and intellectually challenging, and many considered it an equivalent to literature, attracting the intellectual elite that sniffed at manga in general. It is by far the most discussed and debated '70s shoujo movement, as well as the most famous in the West, but it was the least commercially successful at the time. Then there was the "Machiko Satonaka domain," with emotionally driven stories full of drama, plot twists, and larger-than-life heroines. Most of the '70s best-selling shoujo series fall under this category, which includes the work of Yukari Ichijo and Ryoko Ikeda and sports manga like "Ace wo Nerae," among others.

Finally, there's the domain in which the "otometique" stories were created. And Miyadai doesn't name it after any of the Ribon artists, calling it the "Mariko Iwadate domain" instead.

In the Satonaka domain, the heroine served as a proxy for the reader in a fantastical world, while in the Iwadate domain, the heroine represented the reader in the real world. But, after all, who is the influential Iwadate?

Mariko Iwadate, who made her debut in 1973 at the age of 16, rose to prominence by embracing the "otometique" style during its peak in the late '70s. Similar to Ribon artists, Iwadate, who mostly worked for Weekly Margaret, captivated readers with her elegant and stylish art, featuring cute clothes, accessories, and intricate details.

Miyadai's choice to name the category after Iwadate rather than the genre pioneer A-ko Mutsu may be attributed to Iwadate's sustained success. After leaving Ribon in 1985, A-ko remained prolific and had a dedicated audience, but she couldn't replicate her peak. Iwadate's popularity, on the other hand, continued unabated even after she transitioned to adult women's manga. Iwadate's work, recognized for its emotional depth, became a significant inspiration for trailblazers like best-selling novelist Banana Yoshimoto and avant-garde manga artist Kyoko Okazaki. In 1993, when Miyadai wrote his book, Iwadate's fame and respect probably made her a more recognizable figure for readers to associate with the category.

Iwadate's soft girly art and story-telling made her extremely popular and influential.

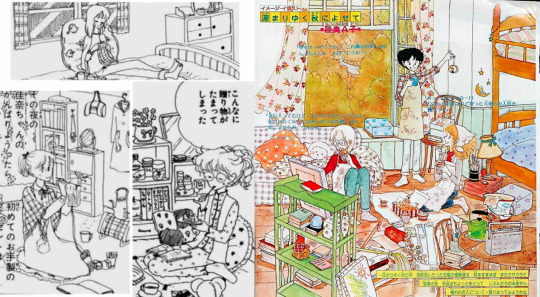

Mariko Iwadate's narrative, especially her post-80s work, has a more psychological and mature element to it when compared to Ribon's artists. She, as an artist, bridged the gap between "otometique" and another highly influential "Iwadate domain" artist, Fusako Kuramochi.

Fusako Kuramochi, debuting while still a teen in the early '70s at Bessatsu Margaret (Betsuma), initially emulated her favorite artists, Moto Hagio and Keiko Takemiya, before finding her style—a realistic portrayal of romance with a substantial psychological element. Her success contributed to shaping Betsuma, alongside Ribon, as arguably the most influential and commercially thriving shoujo title -- the go-to magazine for high school rom-com.

Like the otometique artists, Fusako Kuramochi first gained prominence with short stories and one-shots. In 1979, she wrote her first series, "Oshiaberi Kaidan," in which each chapter depicted the life of a young girl from junior high to her graduation day. In 1980, she published "Itsumo poketto ni Chopin," a classical music manga that also dealt with growing up as a teenager in the city. From then on, she'd publish about two hit series every year in Betsuma before graduating successfully to adult women's manga in 1994.

Kuramochi's success was due to her great skill in portraying girls going through crushes, heartbreaks, and jealousy. The psychological elements struck a chord with readers and helped her create male romantic leads that were extremely popular.

Another component of Kuramochi's work was her sophistication, a result of her upbringing. Her father was the chairman of one of Japan's biggest printing companies, and she was raised in Shibuya, in the center of Tokyo, while attending an exclusive all-female institution. The fact she spent her youth in the middle of Tokyo's hustle and bustle meant she knew the capital well, and her works were full of references to trendy cafes, restaurants, nightspots, and neighborhoods. Her Betsuma work was published right before and during Japan's ostentatious Bubble years, so many chasing an exciting city life referred to her work.

While her stories reflected the reality and aspirations of the Bubble years, Kuramochi's true gift lay in providing readers with a realistic depiction of growing up and falling in love, making her work immensely popular. In general, consumerism -- displayed through clothes, accessories, and decor -- isn't as crucial to her success as the three Ribon "otometique" artists.

While Fusako Kuramochi is part of the "Iwadate domain," you can argue that Kuramochi evolved into her own category, which was vital for the development of real-life love stories in shoujo in the '80s and '90s and the rise of other highly-influential artists like Ryo Ikuemi.

But going back to the three '70s movements, "otometique"/"Iwadate domain" was definitely the most influential one in steering shoujo manga in its current direction. On the other hand, all of these domains co-existed together and fed from each other. In 1977, during the "otometique" boom, Yukari Ichijo remained untouched as one of Ribon's most popular artists with her emotionally charged dramas. It was the success of Ichijo and other "Satonaka domain" artists that allowed the "Hagio domain" to debut and take risks. In turn, it was the "Hagio domain" that showed there were rewards for young risk-taking shoujo artists.

Yumiko Oshima, known for her girly art and sensitive story-telling, is the inspiration behind the otometique boom.

When asked which artist inspired them the most, both A-ko Mutsu and Mariko Iwadate gave the same answer: Yumiko Oshima. Oshima, known for her quirky love stories and girly art, is an artist who trained alongside Hagio and Takemiya at the Oizumi salon and rose as part of the "Year 24 group," publishing risk-taking manga in Shogakukan and Hakusensha's magazine after a brief stint in Weekly Margaret. In other words, despite the striking differences, the origin of the "Iwadate domain" is the "Hagio domain."

While the influence of the idealized real-life romance is the one we can better observe today, contemporary shoujo would not exist if not for all these three styles meshing together and creating something new. And from that, things kept evolving and changing and gaining new forms. Because, once again, manga, and especially shoujo manga, is about reflecting the girly ideals of its time.

#ribon#margaret#go nagai#miki to apple pie#yumiko tabuchi#otometique#otometique manga#mutsu a-ko#mutsu ako#hideko tabuchi#70s japan#fusako kuramochi#betsuma#shoujo manga#vintage shoujo#vintage manga#harenchi gakuen#yumiko igarashi#nakayoshi#yumiko oshima

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Keita Maruyama x Ai Yazawa

Finally! After being announced in April 2024, Keita Maruyama’s manga is set to be released at the end of March 2025. After many years, Ai Yazawa is returning as a mangaka for a chapter in this special anthology. Her last work as a mangaka was back in 2013 with Junko’s Room. Since July of last year, chapters have been published monthly on Otonamuse magazine’s website. However, Ai Yazawa’s chapter is exclusive to the book, which will be released at the end of the month alongside works by Chika Umino, Fusako Kuramochi, and Naito Yamada.

In case anyone’s interested, the chapters by Haruko Kumota, Erika Sakurazawa, Satoru Hiura, Akiko Higashimura, and Naoko Matsuda have been published online, and you can check them out at this link.

source

Ai Yazawa returning to work as a mangaka doesn’t mean that NANA is coming back, but I believe this is great news for fans who are eager to see her illustrations again. 🍓

Preview:

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

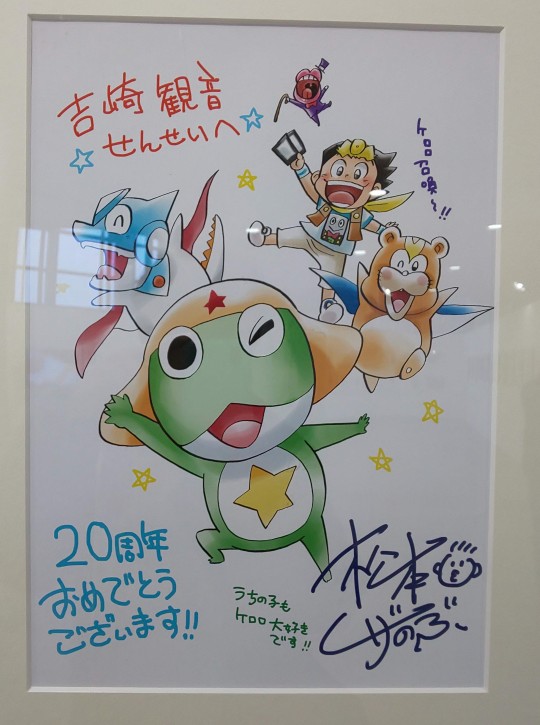

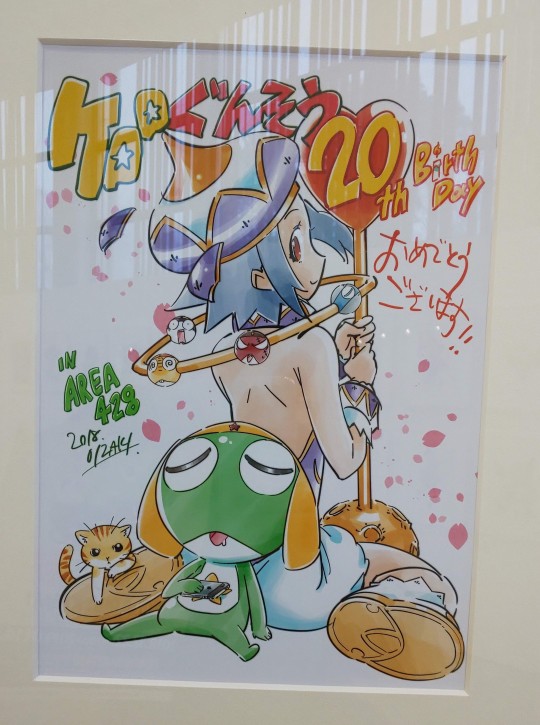

Keroro Illustrations By :

Yumeuta / Aôki Hayato

Shigenobu Matsumoto / FROGMAN

Fly / Fusako Kuramochi

Fumitoshi Oizaki / Koike Satoshi

Hajime Katoki / Katsu Aki

Kazuhiko Shimamoto / Yutaka Hara

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Kuramochi Fusako's Celluloid no Door. First published in Bessatsu Margaret's 1984 February issue, and later compiled in the second volume of her A-Girl (1985).

#Fusako Kuramochi#くらもちふさこ#A-Girl#えーガール#セルロイドのドア#Celluloid Door#shoujo manga#80s manga#80s shoujo#Kuramochi Fusako

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

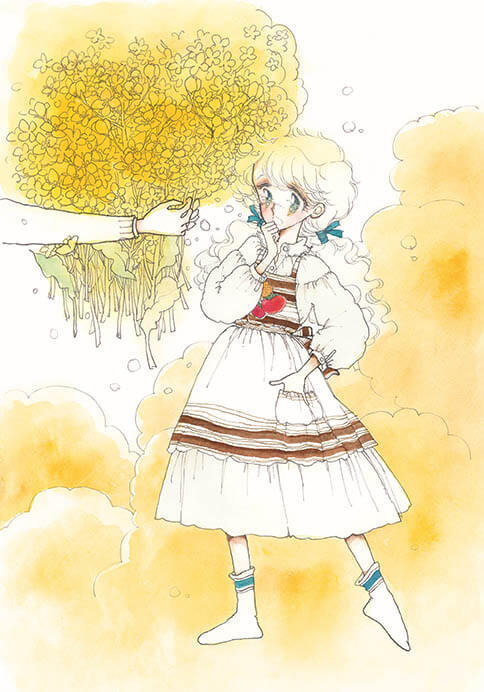

Fusako Kuramochi 50th Anniversary Art works book

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Oshaberi Kaidan by Kuromochi Fusako

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Encore ga Sankai by Kuramochi Fusako

#encore three times? does that make sense?#i was gonna write the title in english but im bad at translation#encore ga sankai#encore ga san kai#kuramochi fusako#fusako kuramochi#retro shoujo#ribbonimg

100 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tsuki no Pulse (月のパルス) by Kuramochi Fusako

#tsuki no pulse#fusako kuramochi#kuramochi fusako#josei#scanned by me#me: INTENSE OCS FEELINGS#love her art style#filli's

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

天然コケッコー (Tennen Kokekko), Fusako Kuramochi

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tokyo Casanova (1983) by Fusako Kuramochi

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Where the Sea Meets the Sky (海の天辺) by Fusako Kuramochi (くらもちふさこ) Betsuma Magazine, aug. 1989 Issue

#vintage manga#vintage magazines#vintage shoujo#Betsuma#Betsuma Magazine#animanga#海の天辺#Where the Sea Meets the Sky#Fusako Kuramochi#くらもちふさこ#mermaid

13 notes

·

View notes