#ketubbah

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ketubbah—Sanandaj, Rojhelat (Iranian Kurdistan) ca. 1920

This GORGEOUS ketubbah is from Sanandaj!

According to the museum: "A most unusual painted Ketubah both in the form of the decoration and the aesthetic form of the text. The brilliant colors and decorative forms are typical of the area of Iranian Kurdistan, particularly the city of Sanandaj."

#jewish#judaism#jewish history#jewish art#religious objects#ketubbah#kurdish jewish#swana jews#mizrahi jews

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ketubbah with depiction of the banks of the Bosphorus, Istanbul, 1853. Handwritten on paper; ink, gouache, and gold powder

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Marriage Contract by Ben Shahn, 1961, Ink, watercolor, paint, and graphite on paper

Most decorated Jewish marriage contracts use ornamental motifs as framing devices for their written Aramaic text. Ben Shahn's Ketubbah is a marked departure from this model. In the superb execution of this document, the artist has integrated floral and foliate decorations within his lyrical Hebrew calligraphy, the predominant design element.

While Shahn's artistic personality emerged through the religious themes in his illustrations for the 1931 Haggadah for Passover, he would not return to such subjects for many years. The artist spent most of the 1930s and 1940s as a social realist painter. Along with so many other painters and sculptors during those difficult years, Shahn felt that art could help right the inequities of society. His terse visual commentaries on such topical subjects as the Sacco and Vanzetti case, Nazism, poverty, and labor problems brought him great recognition as both a humanitarian and an artist. It was after World War II that he turned inward through what has been called his transition from social to personal realism. During this period he incorporated allegory and religious and philosophical symbolism in his work, often based on his own cultural heritage.

Shahn's updating of the traditional ketubbah results from his changing stylistic and subjective concerns. He became fascinated with letters, both Hebrew and English, which became essential elements in his work. This calligraphic preoccupation led to his 1954 illustrations for The Alphabet of Creation, a book which related a parable of the origin of the Hebrew alphabet. His own combination of these twenty-two letters become a personal stamp and appears on most of his prints and drawings after 1960, including this Ketubbah.

Like the butterfly stamp of James Whistler and the Japonist monogram of Toulouse-Lautrec, this symbol shows Shahn's stylistic inspiration as coming from outside mainstream Western culture. The expressive style of Shahn's Hebrew characters changes with the meaning of each theme he depicts. For this Ketubbah, which is presented at the joyous celebration of marriage, he develops a commanding but elegant Hebrew appropriate to the legal nature of the document and the solemnity of the moment-a calligraphy markedly different from the flame-like evanescences in his tribute to the Feast of Lights, Hanukkah. As had been the custom of Hebrew scribes throughout the ages, Shahn adds eccentric elements to certain letters. Most notable here is the oft-repeated, stylized Star of David.

Shahn's meandering floral and foliate forms refer to Psalm 128:3, a common visual allusion in Jewish marriage contracts: "Thy wife is a fruitful vine in the midst of thy house, thy children are as young olive trees set around thy table." (Kleeblatt, Norman L., and Vivian B. Mann. TREASURES OF THE JEWISH MUSEUM. New York: Universe Books, 1986, pp. 192-193.)

#the jewish museum ny#ben shahn#kettubot#marriage contracts#jewish art#judaica#hebrew calligraphy#calligraphy

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ketubbah with birds from Ernakulam, Cochin, India, 1909

Groom: Menahem, son of Rabbi Elijah. Bride: Rebekah, daughter of Rabbi Elijah.

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jewish marriage contract (ketubbah), Yazd, Iran, 1837

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

Earliest known American Ketubbah (Jewish wedding contract), and sole known illustrated 18th century American Ketubbah, dated 2 Sivan, 5511 (May 15, 1751). Celebrating the wedding of Shalva bas Solomon (Sloe Meyers) and Hayim ben Moshe haLevi (Hayman Levy). They were members of New York’s only synagogue, Kehilah She’arit Israel (Congregation Remnant of Israel), which is the oldest Jewish congregation in North America (established 1654).

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adept Anglophone pines to learn Yiddish as a second language

When alive colorful turns of phrases uttered courtesy my father or mother whose ability to describe a situation perfectly verbalized and couched by a dialect of High German including some Hebrew and other words now embolden me - a sexagenarian poet to embark upon quest shunning aim buzzfeeding insatiable avocation to acquire fluency communicating the tongue spoken by Ashkenazi Jews - which Semitic peoples populated a thick trunk line of mine, and crisis of identity and existentialism rents psyche, cuz I don't feel linkedin to any warp and weft nationality akin to feeling alienated analogous life likened to being left adrift within the outer limits of the twilight zone where dark shadows slither slinky like across field of view teasing me to mimic sounds of silence after I hear the echo of thirteenth century Jews in Germany housed in ghetto where over time countless refugees forced to leave their country fleeing to neighboring kingdom of Poland, where they could practice religious worship rites more freely unwitting being hounded and persecuted run clear out of adopted country after absorbing German and Slavic raw bits, a critical ingredient of powder milk biscuits ordaining, fortifying, and bolstering shy people with the courage to stand up to moratorium against sacred rites of passage viz Jewish leaders rabbis, rebbes, or hakhamim stemming from "rabbi" from the Hebrew word rav, which means "teacher" who facilitates bar mitzvah and bat mitzvah when a boy or girl respectively reaches the age of thirteen regarded as ready to observe religious precepts and eligible to take part in public show as able, eager, and willing, partaking and fraternizing with congregation, which ceremony includes traditional rituals, speeches, and a celebration foretaste fêting newly minted male hinting of his marriage between 18 and 20 years of age, a sacred union between Jewish man and a Jewish woman documented by a contract enshrining ten obligations toward his wife (or her descendants) and four rights in respect of her which enumeration of moral imperatives now follows suit accessed courtesy Jewish virtual library - A project of Aice, a learning revelation to yours truly - me, whose lineage linkedin with the credo, heritage, precepts and tenets constituting one of the world's oldest religions, dating back over 3,500 years. The obligations are (a) to provide her with sustenance or maintenance; (b) to supply her clothing and lodging; (c) to cohabit with her; (d) to provide the *ketubbah (i.e., the sum fixed for the wife by law); (e) to procure medical attention and care during her illness; (f) to ransom her if she be taken captive; (g) to provide suitable burial upon her death; (h) to provide for her support after his death and ensure her right to live in his house as long as she remains a widow; (i) to provide for the support of the daughters of the marriage from his estate after his death, until they become betrothed (see *Marriage) or reach the age of maturity; and (j) to provide that the sons of the marriage shall inherit their mother's ketubbah, in addition to their rightful portion of the estate of their father shared with his sons by other wives. The husband's rights are those entitling him: (a) to the benefit of his wife's handiwork; (b) to her chance gains or finds; (c) to the usufruct of her property; and (d) to inherit her estate.

0 notes

Text

Ketubbah. Isfahan, 1881

#Jewish#posted#ketubah#ketubba#ketubbah#hebrew calligraphy#Jewish calligraphy#Jewish illumination#Iran#Persia#Persian Jews#MENA

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ketubbah - Unknown Florentine Artist, 1699

Ink on shell gold parchment (24 3/4 x 18 3/4 in.; 629 x 476 mm)

This is the earliest extant decorated ketubbah--a Jewish pre-marriage wedding contract-- from Florence. It celebrates the wedding of Joshua ben Moses Prato and Seda bat Joshua Balanes in Florence on Wednesday, 3 Adar II 5459 (March 4, 1699).

The seventeenth century witnessed the rise of ketubbah decoration in cities throughout Italy, and the present document is the earliest known example of a decorated marriage contract from Florence. Nearly the entire surface of the parchment is embellished with shell gold and a pale green wash, and concentric circles inscribed with biblical verses and blessings enframe the text.

It was customary in ketubbot from other Italian cities such as Venice and Padua to include a depiction of Jerusalem above the text. This is a direct allusion to the biblical verse which mandates that one should “keep Jerusalem in memory even at [one’s] happiest hour” (Ps. 137:6). In this ketubbah, the same result is achieved by the insertion of the word “Jerusalem,” boldly written in monumental Ashkenazic calligraphy, under the elegantly scalloped upper border. [x]

#Religion#Judaism#17th Century#Italy#Marriage#Manuscript#Ketubbah#Ink#Parchment#Art#Art History#History

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This ketubbah was a first for me: the first ketubbah that I've hand-delivered in Minneapolis! And another first: in specifying the place, this couple chose to include a land acknowledgement: "here, on the occupied traditional land of the Dakota and Anishinaabe people, now known as Minneapolis." Pretty sure this is the first time anyone has ever written Anishinaabe on a ketubbah, too, but I'd be happy to be proven wrong! 😂 Do you know whose land you live on? Check out native-land.ca to find out!

#jewish art#jewish#calligraphy#hebrew#hebrew calligraphy#native american#native land#dakota#anishinaabe#minnesota#our home ON native land#ketubbah#ketubah#judaica#lettering#my work#my art

546 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Magnificent Decorated Ketubbah , Livorno, Tuscany, 1698.

“This early and exceedingly rare marriage contract from the port city of Livorno is ornamented with a sumptuous array of decorative elements. Above the text, a panoramic view of the walled city of Jerusalem is surrounded by six small medallions illustrating verses from Psalm 128 traditionally sung at Italian weddings. Bordering the text are twenty-four elaborate vignettes. Twelve of these feature emblems, each of which signifies one of the twelve tribes of Israel; each of these emblems is, in turn, coupled with a corresponding zodiac sign. These begin directly above the first word of the text with Aries / Issachar and proceed counter-clockwise. The remaining twelve scenes depict the four Aristotelian elements (Water, Earth, Wind and Fire), as well as the four seasons of the year and the four senses (Taste, Sight, Smell and Hearing). Dr. Shalom Sabar has shown how this multifaceted imagery, incorporating the earliest pairing in Jewish art of the emblems of the twelve tribes with the signs of the zodiac, demonstrates a highly sophisticated view of the world as well as an in-depth knowledge of Jewish sources.”

#Italy#Italian Jews#European Jewry#I heard you folks like brightly colored ketubbahs#ketubbah#jewish wedding#Tuscany#Judaism

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ketubbah—Salonika (Thessaloniki), Greece ca. 1856

According to the museum: "Ketubot from Salonica are not common. Those that are found are generally very colorful, as is the present example, and are decorated with floral patterns. They are written with two separate areas for the text, a space that is shaped like the two Tablets of the Law."

#jewish#judaism#jewish history#jewish art#religious objects#ketubbah#ketubah#sephardic#salonika#saloniki jews#thessaloniki

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

For Black History Month, we invited writer Antwaun Sargent to explore works of art in the Jewish Museum Collection that celebrate the intersection of the black and Jewish experience. Nigerian artist ruby onyinyechi amanze’s ketubbah (marriage contract) newly commissioned for Scenes from the Collection, imagines a racially-ambiguous couple surrounded by symbols of constellations that integrate the ethos of the ketubbah and black identity.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ketubbah from Casale Monferrato, 1772

Celebrating the marriage of Meir ben Johanan Solomon (known as Jonah Zalman) and Zipporah bat Simeon Hayyim Levi Morello on Friday, 1 Adar II 5532 (March 6, 1772).

This exquisitely decorated marriage contract records the wedding of members of two of the most important families in the Piedmontese town of Casale Monferrato. The groom, Emilio Meir Vitta Zalman (1756-1820), was the scion of a prominent family of landowners and bankers. He was a lay member of Napoleon’s Sanhedrin, and his son, Giuseppe Raffaele Vitta, was made a baron in 1855 for his contribution to the nation in assisting soldiers wounded in the Crimean War.

The document is lavishly decorated with a richly colored floral border within which cupids frolic. The family emblems of the groom and bride adorn the ketubbah and appear in ovals at the top right and left of the document. The tapered shape of the parchment’s lower portion is a characteristic feature of ketubbot from Casale Monferrato and gives the document the appearance of a shield. The small but active Italian Jewish community of Casale Monferrato is well known for its synagogue, an architectural jewel of baroque magnificence, as well as for the production of beautiful ceremonial objects. Surprisingly, however, fewer than a dozen decorated ketubbot from seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Casale Monferrato survive, and the present marriage contract is a rare, splendid example of the manner in which the Jews of Piedmont would celebrate their joyous occasions.

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

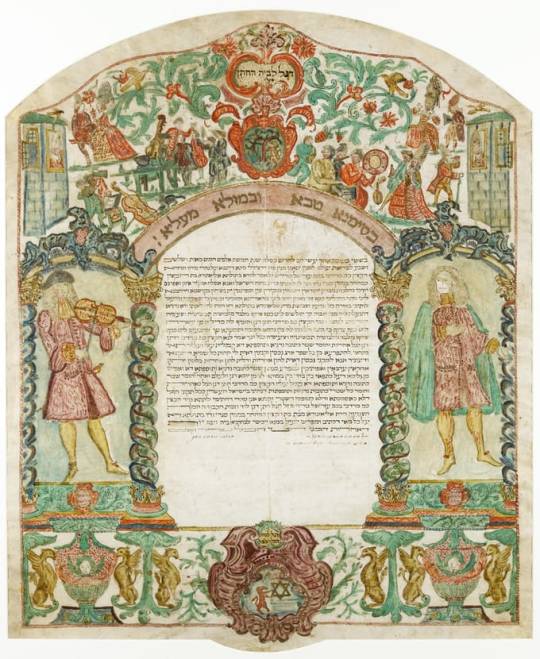

From the Jewish Museum, originally from Vercelli (Italy), Date:1776

Berger, Maurice et al. MASTERWORKS OF THE JEWISH MUSEUM. New York: The Jewish Museum, 2004, pp. 120-121, writes, “In Italy, ketubbot were commissioned by all Jews, including Sephardi, Ashkenazi, Levantine (from the eastern Mediterranean), and Italian- descendants of the old Roman community. Written on parchment, they usually featured lavish decoration, inspired by both Jewish and Christian art. For instance, the use of an archway to frame the text, as seen in this fine example from Vercelli, can be traced to the title pages of Hebrew printed books- northern Italy was a main center of Hebrew printing-but may also be linked to local architecture or sculpture. Figurative representation was also common in Italian ketubbot, although for centuries, most Jews had shied away from it because of their stern interpretation of the biblical prohibition against graven images. The inclusion of human figures, some allegorical and others portraying biblical or genre scenes, reflects a high degree of acculturation.

Other popular motifs in decorated Italian ketubbot include the signs of the zodiac and, as seen here, the emblems of the two families. The adoption of unofficial coats of arms was widespread among wealthy Italian Jews, in imitation of the practices of the local nobility Most ketubbot include a single shield, containing the insignia for both families, or just that of the groom, whose family usually commissioned the contract because he was obligated to furnish the bride-Eleonora- with a ketubboh. This example, however, features two separate emblems, possibly because the bride belonged to a family of prominent scholars, including Benjamin Segrè of Vercelli, who might have been her father. The coat of arms for the Segre family-a rampant lion facing right with a Star of David-is featured at the center of the lower border. No less distinguished was the Treves family, to which the groom-Mordecai, son of Azriel Treves- belonged. Their emblem-a rampant lion to the right of an apple tree-appears above the text at center, a prominent location, for the groom's family likely commissioned the document. Issued in Vercelli, this ketubbah differs from other extant examples from the same Piedmontese city, characterized by an arcuated shape at bottom and a floral border. Although some Italian contracts depict the bride and groom, very few represent the wedding party-shown here in lavish costumes and hairdos-or the attendant musicians. Flirtatious interactions between various couples add a picaresque note, including a distinguished man with a cane peering through his spyglass at a lady at a window, at the upper right. A later example from Pesaro, dated 1853, at the Israel Museum ('79/339), also features a gathering of musicians and elegantly dressed couples, but the figures there were cut out from printed sources, painted, and pasted onto the parchment, instead of finely rendered, as seen here. The extravagance of examples such as this one might have prompted Italian rabbis to repeatedly enact laws limiting the amount of money that could be spent on the decoration of a marriage contract. The secular nature of this ketubboh's decorative program, with figures of a musician and a young man elegantly dressed (perhaps a rendering of the groom?) in the niches often reserved for depictions of Moses and Aaron, indicates that it might have been the work of a Christian artist. Many other Italian examples, however, display a close relationship between text and image, with depictions of biblical scenes featuring heroes whose names were borne by the groom, the bride, or their fathers, with extensive use of Hebrew texts, attesting that they were decorated either by Jewish artists or by Christian makers under the strong guidance of their Jewish patrons.”

105 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jewish marriage contract. Vidin, Bulgaria. Mid-19th - Early 20th century.

“Although the Jewish community in Vidin has existed since the 6th century, very few decorated marriage contracts are extant from this town; the few that remain all date to the 19th century and both hand-decorated and printed borders were used. As is customary with ketubbot from this region, the text is set within a colorful double archway and divided into three sections: the ketubbah, the tena’im, and below, a list of the dowry. The decoration found on ketubbot from Bulgaria is primarily floral with the addition of putti and lions enlivening the document.”

Sotheby’s

#bulgaria#vidin#northeastern bulgaria#judaism#jewish marriage contracts#mid-19th century#early 20th century#sothebys

58 notes

·

View notes