#jules guérin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Jules Guérin, {2022} A Shaman's Tale

#film#gif#jules guérin#a shaman's tale#2022#animation#short film#colour#ai art#male filmmakers#2020s#france

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jules Guérin

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pauline Moulettes, Richard Deiss, Jules Raynal & George Paul by © Nicolas Guérin

1 note

·

View note

Text

non-exhaustive list of sources that are imo especially interesting/thought-provoking, just really solid, or otherwise a personal favorite:

MISC

“Leaders and Martyrs: Codreanu, Mosley and José Antonio,” Stephen M. Cullen (1986)

“Bureaucratic Politics in Radical Military Regimes,” Gregory J. Kasza (1987)

A History of Fascism, 1914–1945, Stanley Payne (1996)

The Fascist Revolution: Toward a General Theory of Fascism, George L. Mosse (1999)

Fascism Outside Europe: The European Impulse against Domestic Conditions in the Diffusion of Global Fascism, ed. Stein U. Larsen (2001)

Ancient Religions, Modern Politics: The Islamic Case in Comparative Perspective, Michael Cook (2014)

MARXISM

“Crisis and the Way Out: The Rise of Fascism in Italy and Germany,” Mihály Vajda (1972)

“Austro-Marxist Interpretation of Fascism,” Gerhard Botz (1976)

“Fascism: some common misconceptions,” Noel Ignatin (1978)

“Gramsci’s Interpretation of Fascism,” Walter L. Adamson (1980)

ARGENTINA

“The Ideological Origins of Right and Left Nationalism in Argentina, 1930–43,” Alberto Spektorowski (1994)

“The Making of an Argentine Fascist. Leopoldo Lugones: From Revolutionary Left to Radical Nationalism,” Alberto Spektorowski (1996)

“Argentine Nacionalismo before Perón: The Case of the Alianza de la Juventud Nacionalista, 1937–c. 1943,” Marcus Klein (2001)

BRAZIL

“Tenentismo in the Brazilian Revolution of 1930,” John D. Wirth (1964)

“Ação Integralista Brasileira: Fascism in Brazil, 1932–1938,” Stanley E. Hilton (1972)

“Integralism and the Brazilian Catholic Church,” Margaret Todaro Williams (1974)

“Ideology and Diplomacy: Italian Fascism and Brazil (1935–1938),” Ricardo Silva Seitenfus (1984)

“The corporatist thought in Miguel Reale: readings of Italian fascism in Brazilian integralismo,” João Fábio Bertonha (2013)

CHILE

“Corporatism and Functionalism in Modern Chilean Politics,” Paul W. Drake (1978)

“Nationalist Movements and Fascist Ideology in Chile,” Jean Grugel (1985)

“A Case of Non-European Fascism: Chilean National Socialism in the 1930s,” Mario Sznajder (1993)

CHINA

Revolutionary Nativism: Fascism and Culture in China, 1925–1937, Maggie Clinton (2017)

CROATIA

“An Authoritarian Parliament: The Croatian State Sabor of 1942,” Yeshayahu Jelinek (1980)

“The End of “Historical-Ideological Bedazzlement”: Cold War Politics and Émigré Croatian Separatist Violence, 1950–1980,” Mate Nikola Tokić (2012)

EGYPT

“An Interpretation of Nasserism,” Willard Range (1959)

Egypt’s Young Rebels: “Young Egypt,” 1933–1952, James P. Jankowski (1975)

“The Use of the Pharaonic Past in Modern Egyptian Nationalism,” Michael Wood (1998)

FRANCE

“Mores, “The First National Socialist”,” Robert F. Byrnes (1950)

“The Political Transition of Jacques Doriot,” Gilbert D. Allardyce (1966)

“National Socialism and Antisemitism: The Case of Maurice Barrès,” Zeev Sternhell (1973)

“Georges Valois and the Faisceau: The Making and Breaking of a Fascist,” Jules Levey (1973)

“The Condottieri of the Collaboration: Mouvement Social Révolutionnaire,” Bertram M. Gordon (1975)

“Myth and Violence: The Fascism of Julius Evola and Alain de Benoist,” Thomas Sheehan (1981)

GERMANY

“A German Racial Revolution?” Milan L. Hauner (1984)

“Abortion and Eugenics in Nazi Germany,” Henry P. David, Jochen Fleischhacker, and Charlotte Höhn (1988)

“Nietzschean Socialism — Left and Right, 1890–1933,” Steven E. Aschheim (1988)

The Brown Plague: Travels in Late Weimar and Early Nazi Germany, Daniel Guérin, tr. Robert Schwartzwald (1994)

“Hitler and the Uniqueness of Nazism,” Ian Kershaw (2004)

HAITI

“Ideology and Political Protest in Haiti, 1930–1946,” David Nicholls (1974)

“Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s State Against Nation: A Critique of the Totalitarian Paradigm,” Robert Fatton, Jr. (2013)

IRAN

“Iran’s Islamic Revolution in Comparative Perspective,” Said Amir Arjomand (1986)

IRAQ

“Arab-Kurdish Rivalries in Iraq,” Lettie M. Wenner (1963)

“From Paper State to Caliphate: The Ideology of the Islamic State,” Cole Bunzel (2015)

“Iraqi Archives and the Failure of Saddam’s Worldview in 2003,” Samuel Helfont (2023)

ISRAEL

“The Emergence of the Israeli Radical Right,” Ehud Sprinzak (1989)

“Max Nordau, Liberalism and the New Jew,” George L. Mosse (1992)

The Stern Gang: Ideology, Politics and Terror, 1940–1949, Joseph Heller (1995)

““Hebrew” Culture: The Shared Foundations of Ratosh’s Ideology and Poetry,” Elliott Rabin (1999)

“Israel’s fascist sideshow takes center stage,” Natasha Roth-Rowland (2019)

“‘Frightening proportions’: On Meir Kahane’s assimilation doctrine,” Erik Magnusson (2021)

ITALY

“The Fascist Conception of Law,” H. Arthur Steiner (1936)

“The Goals of Italian Fascism,” Edward R. Tannenbaum (1969)

“Fascist Modernization in Italy: Traditional or Revolutionary?” Roland Sarti (1970)

“Fascism as Political Religion,” Emilio Gentile (1990)

“I redentori della vittoria: On Fiume’s Place in the Genealogy of Fascism,” Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht (1996)

JAPAN

“A New Look at the Problem of “Japanese Fascism”,” George M. Wilson (1968)

“Marxism and National Socialism in Taishō Japan: The Thought of Takabatake Motoyuki,” Germaine A. Hoston (1984)

“Fascism from Below? A Comparative Perspective on the Japanese Right, 1931–1936,” Gregory J. Kasza (1984)

“Japan’s Wartime Labor Policy: A Search for Method,” Ernest J. Notar (1985)

“Fascism from Above? Japan’s Kakushin Right in Comparative Perspective,” Gregory J. Kasza (2001)

PARAGUAY

“Political Aspects of the Paraguayan Revolution, 1936–1940,” Harris Gaylord Warren (1950)

“Toward a Weberian Characterization of the Stroessner Regime in Paraguay (1954–1989),” Marcial Antonio Riquelme (1994)

ROMANIA

“The Men of the Archangel,” Eugen Weber (1966)

“Breaking the Teeth of Time: Mythical Time and the “Terror of History” in the Rhetoric of the Legionary Movement in Interwar Romania,” Raul Carstocea (2015)

RUSSIA

“Was There a Russian Fascism? The Union of Russian People,” Hans Rogger (1964)

“The All-Russian Fascist Party,” Erwin Oberländer (1966)

“The Zhirinovsky Threat,” Jacob W. Kipp (1994)

Russian Fascism: Traditions, Tendencies, Movements, Stephen Shenfield (2000)

“Why fascists took over the Reichstag but have not captured the Kremlin: a comparison of Weimar Germany and post-Soviet Russia,” Steffen Kailitz and Andreas Umland (2017)

SLOVAKIA

“Storm-troopers in Slovakia: the Rodobrana and the Hlinka Guard,” Yeshayahu Jelinek (1971)

SPAIN

“The Forgotten Falangist: Ernesto Gimenez Cabellero,” Douglas W. Foard (1975)

Fascism in Spain, 1923–1977, Stanley Payne (1999)

“Spanish Fascism as a Political Religion (1931–1941),” Zira Box and Ismael Saz (2011)

SYRIA

The Ba‘th and the Creation of Modern Syria, David Roberts (1987)

TURKEY

“Kemalist Authoritarianism and fascist Trends in Turkey during the Interwar Period,” Fikret Adanïr (2001)

“The Other From Within: Pan-Turkist Mythmaking and the Expulsion of the Turkish Left,” Gregory A. Burris (2007)

“The Racist Critics of Atatürk and Kemalism, from the 1930s to the 1960s,” İlker Aytürk (2011)

UNITED KINGDOM

“Northern Ireland and British fascism in the inter-war years,” James Loughlin (1995)

“‘What’s the Big Idea?’: Oswald Mosley, the British Union of Fascists and Generic Fascism,” Gary Love (2007)

“Why Fascism? Sir Oswald Mosley and the Conception of the British Union of Fascists,” Matthew Worley (2011)

UNITED STATES

“Ezra Pound and American Fascism,” Victor C. Ferkiss (1955)

“Populist Influences on American Fascism,” Victor C. Ferkiss (1957)

“Vigilante Fascism: The Black Legion as an American Hybrid,” Peter H. Amann (1983)

“Silver Shirts in the Northwest: Politics, Personalities, and Prophecies in the 1930s,” Eckard V. Toy, Jr. (1989)

“Women in the 1920s’ Ku Klux Klan Movement,” Kathleen M. Blee (1991)

“‘Leaderless Resistance’,” Jeffrey Kaplan (1997)

“The post-war paths of occult national socialism: from Rockwell and Madole to Manson,” Jeffrey Kaplan (2001)

“The Upward Path: Palingenesis, Political Religion and the National Alliance,” Martin Durham (2004)

“The F Word: Is Donald Trump a fascist?” Dylan Matthews (2021)

“Castizo Futurism and the Contradictions of Multiracial White Nationalism,” Ben Lorber and Natalie Li (2022)

#this is not The Masterpost this has just emerged along the way#and there's definitely plenty that could go here that aren't bc i just got tired of listing them#i need somewhere and preferably multiple places to put sources so i feel like ive accomplished something when i finish reading them lol

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

ok but like steampunk shit was my first hyperfixation ever and let me tell you i am foaming at the mouth as i type this. like i still have an egregious quantity of books about the whole steampunk aesthetic, and also for other people obsessed with steampunk and classic litterature, may i suggest the manga 'city hall' by guillaume lapeyre and rémi guérin, since i believe it's been translated in english (spoilers : the main character is jules verne) like it had such a chokehold over me and i can't wait to read more of steampunk copia hdhdjdjjdjekedk

I desperately wanted to create a steampunk costume not too long ago (but i lack sewing skills). I even bought a nerf gun to try and make it “steampunky” (but again I don’t have that skill set XD).

Thank you for the manga rec! I’m going to check that out. I’ve been digging through Pinterest and such to add to my “Capitano Copia” mood board 😅. And thank you for your message and being excited about this story! I’m really excited about it too 💙💙

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

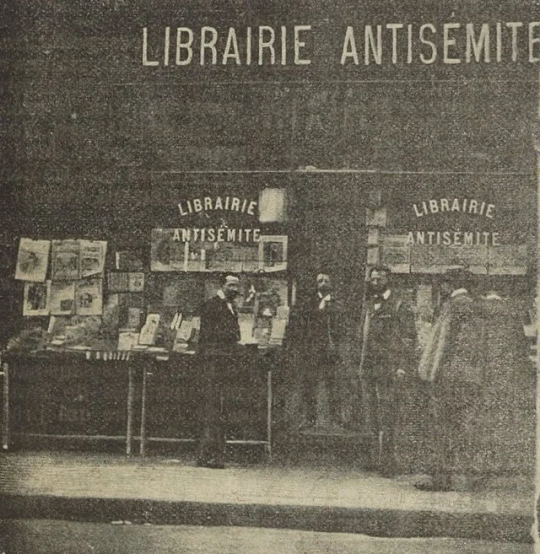

"Librería antisemita" de Charles-Henri Devos en el número 45 de la calle V

Charles Devos (1864-1931) trabajó con el infame activista antisemita Édouard Drumont en la década de 1890, administrando el periódico de Drumont La Libre Parole , gestionando la contabilidad y las suscripciones. Pronto se convirtió en administrador de este periódico, además de gestionar la Librairie antisemita aquí representada.

Su influencia en el movimiento antisemita francés creció cada vez más, hasta que se convirtió en presidente de la Liga Nacional Antijudía en 1903.

Tanto el pro-Dreyfus Jacques Prolo como el anti-Dreyfus Jules Guérin acusaron a Devos de malversar dinero de La Lbire Parole ; El historiador Bertrand Joly describió a Devos como un "administrador dudoso" y lo situó entre los "delincuentes" del nacionalismo francés anti-Dreyfus.

El final del caso Dreyfus no frenó la carrera de Devos: abandonó La Mibre Parole y, en 1917, fundó su agencia de publicidad.

En 1919 fue elegido miembro del Ayuntamiento de Garches, convirtiéndose en alcalde en 1925. Recibió la Legión de Honor en 1929 por sus 36 años de carrera en la prensa y la política. Fue apoyado por la conservadora Federación Republicana .

Tras su muerte en 1931, se le dio su nombre a una plaza de la ciudad; además, el Marqués de Morès hizo poner su nombre a una calle y a un camino. Estos tres nombres de carreteras se cambiaron en 2022, ya que ambos hombres eran conocidos e infames activistas antisemitas, y se cambiaron en honor a Simone Veil, Marie Curie y Lucie Aubrac.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frankreichs Dritte Republik: Frankreichs Dritte Republik Der Tag an dem das Fort Chabrol fiel

Die JF schreibt: »Im Herzen Frankreichs verschanzen sich Antisemiten um Jules Guérin im Widerstand gegen die Dritte Republik. Paris ist im Ausnahmezustand. Vor 125 Jahren fällt sein Fort Chabrol nach 38tägiger Belagerung. Dieser Beitrag Frankreichs Dritte Republik Der Tag an dem das Fort Chabrol fiel wurde veröffentlich auf JUNGE FREIHEIT. http://dlvr.it/TDW80V «

0 notes

Photo

435) Grand Occident de France, GOF, Great West of France, Wielki Zachód Francji - Francuska Liga Antysemicka (LAF), przemianowana na Grand Occident de France (GOF) przez antymasonizm w 1899 r., francuska liga antysemicka założona w 1897 r. i kierowana przez dziennikarza i działacza antydreyfusowskiego Julesa Guérina. Francuska Liga Antysemicka (LAF) przedstawia się jako kontynuacja Ligue nationale anti-sémitique de France (Narodowej Ligi Antysemickiej Francji), której przewodniczy polemista Édouard Drumont i działała w latach 1889-1892. Ta pierwsza liga, charakteryzująca się słabą liczebnością, prawie zaprzestała wszelkiej działalności po 1890 roku, Drumont szybko stracił zainteresowanie na rzecz pisania swoich książek, a następnie własnej gazety La Libre Parole, założonej w 1892 roku. Członek tej pierwszej ligi, współpracownik La Libre Parole i kluczowa postać w grupie antysemickich bojowników skupionych wokół markiza de Morès, Jules Guérin postanowił po śmierci markiza, nastąpiło w czerwcu 1896 r. Pierwsze oznaki działalności tej nowej ligi antysemickiej bez entuzjazmu donoszono w La Libre Parole w styczniu i lutym 1897 roku. Chociaż Drumont został mianowany honorowym prezesem ligi, był ostrożny wobec tej inicjatywy, która groziła postawieniem poważnego konkurenta ambitnemu Guérinowi, który panuje nad tą bojową organizacją jako samozwańczy „delegat generalny”. Siedziba ligi została po raz pierwszy zainstalowana przy rue Alphonse-Poitevin 7 (przemianowanej kilka miesięcy później na rue Lentonnet). Liczba członków LAF była często przeceniana, w szczególności na podstawie fałszywych danych przedstawionych przez Guérina, który twierdzi, że od lipca 1897 r. było 11 000 członków, a następnie 40 000 w marcu 1899 r. W rzeczywistości w kwietniu 1897 r. było ich tylko 384, a historyk Bertrand Joly szacuje, że LAF nigdy nie liczyła więcej niż 2700 członków, w tym 1500 w Paryżu. Szacunki te dotyczą tylko paroksyzmu antysemickiej agitacji wokół sprawy Dreyfusa w latach 1898-1899: od 1900 r. policja liczyła mniej niż tysiąc członków, w tym jedną trzecią w Paryżu i na jego przedmieściach. Poza stolicą, gdzie Guérin usiłuje zmobilizować więcej niż pięćdziesiąt osób naraz, sekcje prowincjonalne zawsze liczyły mniej niż dwadzieścia osób, najczęściej o dość małej liczebności i bardzo krótkotrwałej aktywności. Oprócz aspektu ilościowego należy również podkreślić problem jakościowy tych liczb, ponieważ kilku członków ligi jest policyjnymi informatorami. Sam Guérin, bardziej motywowany pokusą zysku niż antysemicką „sprawą”, jest mocno podejrzany o potajemną współpracę z władzami w zamian za pieniądze. Po utrzymywaniu pewnych powiązań z różnymi organizacjami, w szczególności ze Union nationale (Związkiem Narodowym) Ojca Garniera, LAF zwrócił się w 1898 roku do kręgów rojalistycznych, które miały obfity fundusz łapówkowy, zarządzany wówczas przez Eugène de Lur-Saluces i Fernanda de Ramela. W lipcu 1898 roku Guérin spotkał w Marienbadzie, pretendenta rojalistów Philippe d'Orléans. Pod koniec tego wywiadu uzgodniono, że rojaliści zapłacą za pośrednictwem André Buffeta i Ludovica Robineta de Plas początkową sumę 300 000 franków dla LAF. Guérin korzysta również z hojności innych osobowości monarchistycznych. Ogółem otrzymał więc w latach 1898-1904 prawie 1,2 miliona franków. Oszołomieni Guerinem, który bezwstydnie wyolbrzymiał wpływ swojej ligi, rojaliści na próżno starali się ponownie połączyć z masami poprzez antysemityzm. Dopiero w 1904 lub 1905 roku, rok lub dwa lata po zniknięciu ligi, rozczarowany pretendent przestał finansować Guérina. Chociaż ten ostatni w dużej mierze skierował te dotacje na swoją korzyść, część pieniędzy rojalistów umożliwiła lidze posiadanie organu prasowego, tygodnika L'Antijuif, założonego w sierpniu 1898 r., oraz bardzo wygodne osiedlenie się w nowej siedzibie. Po raz pierwszy przeniesiona pod numer 56 rue de Rochechouart w lipcu 1898 r., siedziba ligi została ostatecznie zainstalowana 6 czerwca 1899 r. pod numerem 51 rue de Chabrol, w budynku przejętym w marcu poprzedniego roku i przekształconym w prawdziwą fortecę. Na działalność LAF składają się spotkania, konferencje i hałaśliwe demonstracje uliczne. Jej członkowie potrafią być wtedy agresywni, jak podczas demonstracji 25 października 1898 r. na Place de la Concorde, gdzie zbrutalizowali komisarza policji Maurice'a Leprousta. Małe grupy satelickie, takie jak Cercle antisémitique d'études sociales (Antysemickie Koło Studiów Społecznych) kierowane przez Daniela Kimona i l'Association française pour l'organisation du travail national (Francuskie Stowarzyszenie Organizacji Pracy Narodowej), krążą wokół ligi i również organizują kilka spotkań. U szczytu antydreyfusowskiej agitacji, na przełomie 1898 i 1899 roku, Guérin brał udział w tajnych zebraniach, których kulminacją była 23 lutego 1899 roku niezdarna próba zamachu stanu kierowana przez Paula Déroulède, przywódcę Ligi Patriotów. Podczas tego wydarzenia ludzie z LAF mieli zaledwie około trzydziestki i pozostawali stosunkowo bierni. W kolejnych dniach przeszukiwano jednak pomieszczenia ligi i domy niektórych jej członków. W odpowiedzi na te poszukiwania LAF wywiesiła plakat, w którym po raz pierwszy nadała sobie tytuł „Wielki Zachód Francji, obrządek antyżydowski”. Odwracając w ten sposób nazwę Wielkiego Wschodu Francji, głównego francuskiego masońskiego stowarzyszenia, potępia przynależność władców do masonerii, którą przedstawia jako organizację „która stała się narzędziem kosmopolitycznego żydostwa, które otwarcie spiskuje przeciwko bezpieczeństwu kraju". Ta nowa nazwa ma również na celu pokazanie paraleli między ligą, oskarżaną o łamanie prawa o stowarzyszeniach, a tolerowanymi przez władze lożami masońskimi. Parodiując trójpunktową literę „F ∴ Wielkiego Wschodu”, Guérin żąda dla swoich ligowców tytułu „Bracia ÷”, który uważa za skromniejszy, „natura dała ludziom tylko dwie pięści do obrony”. Ten ostatni będzie się zresztą bawił tłumacząc te dwa punkty „dwoma pięściami w twarz”. Zmiana nazwy ligi została oficjalnie ogłoszona przez Guérina 3 marca 18993 r. W sierpniu, kiedy zmasowana represja wymierzona była w rojalistycznych, nacjonalistycznych i antysemickich przywódców ruchu antydreyfusowskiego w celu postawienia przed Sądem Najwyższym procesu o spisek, Guérin stawiał opór aresztowaniu, barykadując się wraz z kilkoma wspólnikami w kwaterze głównej GOF przez półtora miesiąca. Wydarzenie to, które było wówczas szeroko relacjonowane w mediach, jest często określane jako „Fort Chabrol”. Ostatecznie aresztowany 20 września Jules Guérin został skazany w styczniu 1900 r. na 10 lat więzienia, zamienionych na wygnanie 14 lipca 1901 r. Pod jego nieobecność zastąpił go jego brat Louis Guérin na czele GOF. Nadal honorowy przewodniczący ligi, Drumont, zachęcony przez niektórych bliskich współpracowników (Méry, Devos i Boisandré), wykorzystał sytuację i założył 3 lipca 1901 r. wybory parlamentarne w następnym roku. Inna konkurencyjna partia, Parti national antijuif (Narodowa Partia Antyżydowska), powstała dwa miesiące wcześniej, ale jej lider, Dubuc, bardzo szybko poróżnił się z Drumontem i stanął po stronie Guerina. Po burzliwym spotkaniu w Bernay 1 grudnia 1901 r. Drumont i jego współpracownicy z hukiem zrezygnowali z GOF. Pozbawiona lidera, osłabiona wewnętrznymi niezgodami i dotknięta rewelacjami publikowanymi przez byłych członków i sojuszników, liga upada. Zniknęła definitywnie w 1903 r., roku naznaczonym opuszczeniem lokalu przy rue de Chabrol, którego meble zostały sprzedane w lipcu 919 r., oraz zaprzestaniem wydawania La Tribune française, dziennika, który zastąpił L'Antijuif w 1902 r., a ostatni numer ukazał się we wrześniu 2517 r. Później skrajnie prawicowi aktywiści ponownie używali nazwy Grand Occident de France. Współpracownik La Libre Parole de Drumonta, a następnie Henry'ego Costona, Lucien Pemjean kierował w ten sposób między 1934 a 1939 miesięcznikiem zatytułowanym Le Grand Occident, organem propagandy i akcji przeciwko judeomasonerii, który wydawał były członek GOF i współpracownik de Guérin , Albert Monniot. Numer z 15 kwietnia 1939 r. zatytułowany “Pétain au pouvoir!“ („Pétain u władzy!").

0 notes

Photo

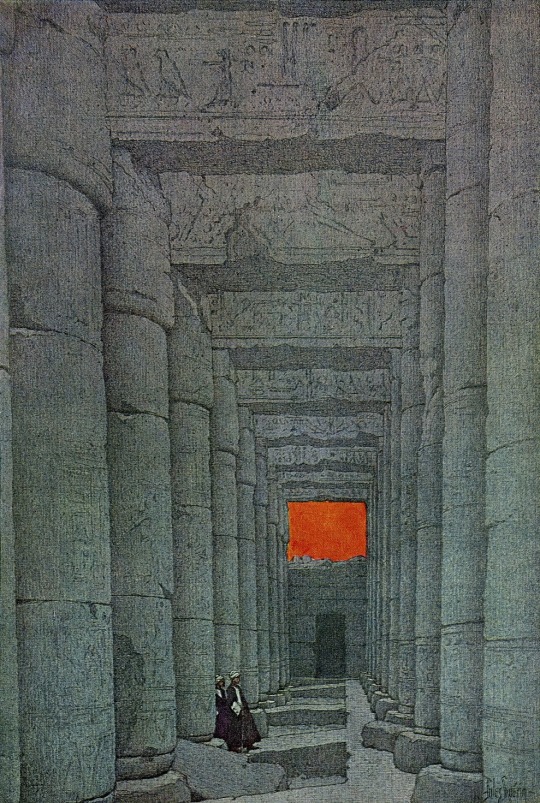

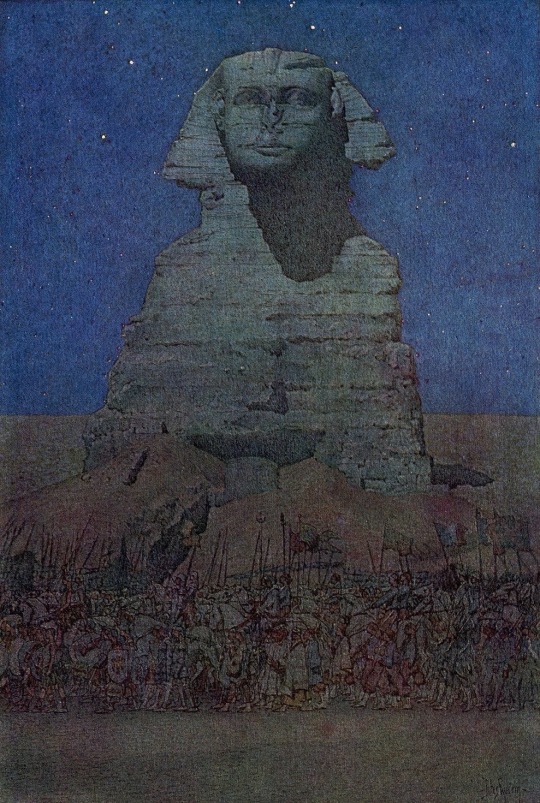

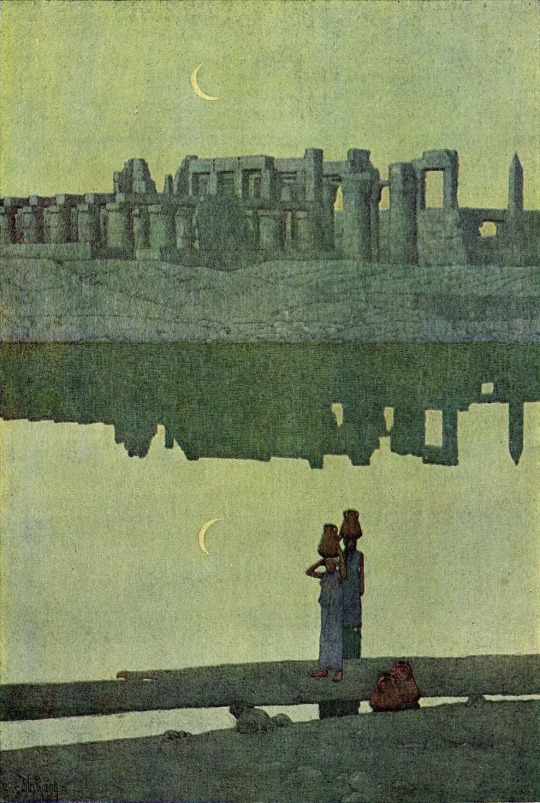

Jules Guerin(American, 1866-1946)

1 unknown 2 Egypt sakkara 3 Egypt temple karnak 4 The temple of Hathor, Dendera 5 Abydos 6 Egypt ramesseum 7 Dead Sea / Moab 8 The Washington Monument lithograph 9 Egypt Lake Karnak Source: 1 2 3 4 5

449 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A shaman's tale

A shaman’s tale

Καμιά φορά, η ανάγκη για μυστήριο είναι μεγαλύτερη από την ανάγκη για απαντήσεις—Ken Kesey— Το μυστικιστικό ταξίδι ενός ισχυρού σαμάνου — μια ιστορ��α βασισμένη σε έναν περουβιανό μύθο για τις θεραπευτικές ιδιότητες του ψυχτορόπου ποτού Αγιαχουάσκα. Προσπαθώντας να ανακαλύψει τρόπους θεραπείας της ανθρώπινης ψυχής, ο σαμάνος διαλογίζεται καθισμένος κάτω από ένα δέντρο, ώσπου από το στήθος του…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Merchandise Mart, Chicago (No. 4)

Jules Guerin's frieze of 17 murals is the primary feature of the lobby and graphically illustrate commerce throughout the world, including the countries of origin for items sold in the building. The murals depict the industries and products, the primary mode of transportation and the architecture of 14 countries. Drawing on years as a stage set designer, Guerin executed the murals in red with gold leaf using techniques producing distinct image layers in successive planes. In a panel representing Italy, Venetian glassware appears in the foreground with fishing boats moored on the Grand Canal and the facade of the Palazzo Ducale rises above the towers of the Piazza San Marco.

"To immortalize outstanding American merchants", Joseph Kennedy in 1953 commissioned eight bronze busts, four times life size, which would come to be known as the Merchandise Mart Hall of Fame:

retail magnates Frank Winfield Woolworth, Marshall Field and Aaron Montgomery Ward

Julius Rosenwald and Robert Elkington Wood of Sears, Roebuck and Company fame

advertiser John Wanamaker, merchandiser Edward Albert Filene, and A&P grocery chain founder George Huntington Hartford.

All of the busts rest on white pedestals lining the Chicago River and face north toward the gold front door of the building.

Dominating the skyline in the south end of the Near North Side, the Mart lies just south of the gallery district on the southern terminus of Franklin Street. Eateries and nightclubs abound on Hubbard Street one block to the north. The Kinzie Chophouse, popular with politicians and celebrities, stands on the northwest corner of Wells and Kinzie, across from the Merchandise Mart. The Chicago Varnish Company Building, listed on the National Register of Historic Places and now housing Harry Caray's restaurant, is located east on Kinzie Street. Across the street to the east is 325 N. Wells Street, home to The Chicago School of Professional Psychology and DIRTT Environmental Solutions.

The Mart is not rectangular in shape, having been constructed after the bascule bridges over the Chicago River were completed. The control house for the double decked Wells Street Bridge stands between the lower level and the southeast corner of the building. The Franklin Street Bridge stands at the southwest corner of the building, at the junction of Orleans Street and Franklin Street. The building slants at the same angle as Franklin Street, from southeast to northwest along Orleans Street.

Source: Wikipedia

#Merchandise Mart#Chicago#Graham Anderson Probst and White#Art Deco#Alfred P. Shaw#USA#façade#exterior#interior#frieze#lamp#Bern#Zytglogge#Jules Guérin#Merchandise Mart Hall of Fame#bust#public art#indoors#outdoors#tourist attraction#landmark#original photography#summer 2019#Illinois#downtown#Midwestern USA#Great Lakes Region#Windy City#I love Art Dec so sue me

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jules Guérin

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Au MuCEM, une très belle expo : “ Salammbô. Fureur ! Passion ! Éléphants ! “

-tenture de l’histoire de Scipion :”La Bataille de Zama", carton de François Bonnemer, d'après Jules Romain et Francesco Penni.

- Baron Pierre-Narcisse Guérin : “Enée racontant à Didon les malheurs de Troie” (je trouve l’enfant très “malaisant”, comme disent les jeunes !)

- Andrea Sacchi : “Didon abandonnée par Enée”

puis les mêmes à l’envers !

#marseille#expo#mucem#salammbô#salammbô. Fureur! Passion! Eléphants !#tenture#renaissance#éléphant#carthage#scipion#zama#françois bonnemer#jules romain#tapisserie#francesco penni#pierre-narcisse guérin#énée#didon#troie#andrea sacchi#peinture#tableau

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#la mort de priam#pierre-narcisse guérin#jules lefebvre#alexandre cabanel#léon bazille perrault#xix#painting#neoclassicism#academic#greek mythology

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A new exhibit has sprung up outside of Colgate’s Special Collections and University Archives reading room! Ever wonder who exactly was responsible for the travel books written during the early part of the twentieth century?

Wait, what’s that? You have never wondered that in your entire life!?

Well now is the time to start! These painters and writers lived fascinating lives so full of incident and exploit that finding the time to publish a travelogue was the least of their accomplishments. They were journalists, soldiers, explorers, nurses, professors, poets, painters, founders of national parks, and parents of famous children. One was even an accountant!

Curious now? Come down to the second floor of Case Library and learn more about this truly interesting group of world travelers!

#colgate university#Colgate Special Collections and University Archives#exhibit#travelogues#wilfrid ball#robert george talbot kelly#nico jungman#mortimer menpes#george wharton edwards#katharine lee bates#isabel anderson#g.e. mitton#william pember reeves#sir francis younghusband#major edward mary joseph molyneux#robert hichens#jules guérin#enos a mills

8 notes

·

View notes