#Jules Raynal

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

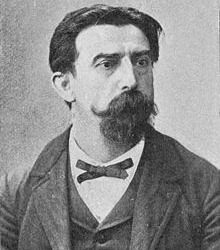

Jules Raynal

580 notes

·

View notes

Text

>>> Collection Jules Raynal smokes

#2

[ > Models_Smokes* ] [ Source : adraynaline ]

#jules raynal#smokingmodels#smokingmodelsnb#touchoneself#touchoneselfnb#shirtlesssmokers#shirtlesssmokersnb#shirtlessnotattoo#shirtlessnotattooblack#cigarette#smokingguys#smokingguysnb

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

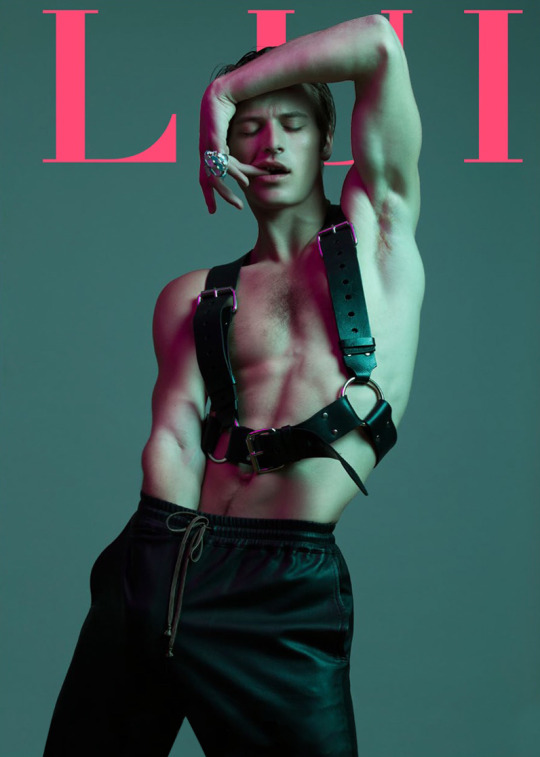

Jules Raynal by Frédéric Monceau for Lui Magazine.

#Photography#Modelling#Fashion#Ambiance#Colour#Frédéric Monceau#Frederic Monceau#Jules Raynal#Leather

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

#jules raynal#mens style#menswear#wool#wool sweater#men in jumpers#jumper#wool jumper#wool crewneck sweater#crewneck#mens wool sweater#mens sweater#male model#male body#male beauty#male fashion

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pauline Moulettes, Richard Deiss, Jules Raynal & George Paul by © Nicolas Guérin

1 note

·

View note

Text

Paradoxes in the Revolutions of 1792 and the Revolt of 1870

Warning: There are some text elements in the treatment of Algerian deportees in New Caledonia that are shocking. So refrain from reading if you are not ready.

Do you share my impression of certain aspects of the different revolutions or uprisings in France? I mean, the French Revolution, at its most left-leaning during the government of Year II, was very conservative regarding property rights. Regarding property rights, the entire political class was very timid, even the far left like the Enragés and the Hébertists, who were more focused on economic issues like taxation. However, some, like Momoro, apparently began to consider land redistribution, such as sharing large farms, but without a clear plan (and far from any notion of collectivization of agriculture). There was a concession made by the Convention on property rights with the Ventôse Laws, perhaps? And it is true that on certain economic issues, there were conservative elements, even though during the journée of September 5, 1793, the sans-culottes managed to extract the maximum.

Even Gracchus Babeuf, who seems to advocate for collective exploitation, primarily talks about agriculture. I'm not saying there weren't progressive aspects. There were, like the introduction of universal suffrage, for example, and many other aspects, such as the fact that deputies like Louis Michel le Peletier defended the project to implement free, mixed, secular, and compulsory education, supported by several deputies, including Robespierre (it's sad that this was only adopted years later by a man who, opportunistically, in my opinion, lacked the integrity of Le Peletier, who seems to have been opposed to most of the revolutionaries of 1793-1794 and who unjustly reaped all the credit for this project—I’m talking about Jules Ferry, sorry to the fans of this character). But it must be acknowledged that there were also conservative aspects.

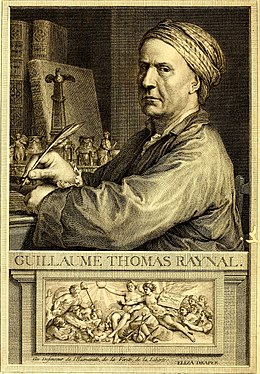

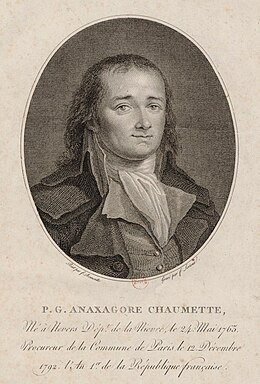

Paradoxically, the Convention proved to be extremely progressive compared to so many others regarding the colonies. The abbé Raynal, so conservative on property rights, apparently called Toussaint Louverture the "Black Spartacus." Sonthonax, considered a Brissotin and advocate of gradual abolition of slavery, did not hesitate to oppose the colonists and slaveholders (just like the Convention) by granting full citizenship to the revolting slaves of 1791 barely a year later. There was the dissolution of the colonial assembly, and important and well-known revolutionaries enthusiastically supported the revolts of the colonized, even their independence, like Deputy Marat or the prosecutor of the Commune, Chaumette, among many others. Black deputies were elected, such as Jean-Baptiste Belley. Some Black people managed to attain high ranks. The overly hostile colonists could be expelled, and there was the dismissal of Governor Philippe Blanchelande, who had distinguished himself by his fierce repression of the slave revolt. During his execution in 1793, Rosalie Julien, one of the important women of the revolution, wrote, "He made the blood of Blacks and patriots flow in streams." It is important to note that she equated the attack on Blacks with that on people considered patriots, a more common position at that time than one might think. I know we must be careful about anachronisms, but I feel that aside from a distrust of foreigners (though this did not prevent people like Fleuriot Lescot or Claude François Lazowski, who came from a Polish family, from holding important positions), the French political class was less racist in 1794 than in 1870 or during the mid-20th century, especially concerning the colonies and overseas territories. There was a regrettable step backward (honestly, can you imagine the Convention of Year II, or the Jacobin or Cordelier Clubs tolerating even the idea of a horrible human zoo as we saw in 1906? I can't). Of course, there were people who supported slavery at that time, like Cloots (a very questionable and paradoxical figure of the revolution, considered close to the Hébertists, yet a very wealthy and conservative man regarding property rights, who had pro-slavery thoughts and was a fervent supporter of colonization because his family and he profited from it, even though he supposedly wanted the Revolution to extend beyond borders according to his own words; according to historian Antoine Resche, he called himself the orator of the human race—very complicated as a revolutionary).

For those who think of the left envisioned by Karl Marx, we're still far from it. Here's an excerpt from The Holy Family: "The revolutionary movement that began in 1789 with the social circle, which, in the midst of its course, had as its main representatives Leclerc and Roux and eventually succumbed temporarily with Babeuf's conspiracy, had sown the seeds of the communist idea, which Babeuf's friend, Buonarroti, reintroduced in France after the revolution of 1830. This idea, developed consistently, is the idea of the new state of the world." Moreover, I have encountered communists who heavily criticize the revolutionaries, except for some ultra-revolutionary members (a few have even added Marat to the list of characters they appreciate, though they know he was not an ultra-revolutionary) by explaining that, in their view, the second revolution from 1792 until the fall of the last Montagnards like Charles Gilbert Romme remained bourgeois, though less so than the one of 1789.

Abbé Raynal

Jean Baptiste Belley

Léger-Félicité Sonthonax

Pierre-Gaspard Chaumette

Jacques Roux

Jean Paul Marat

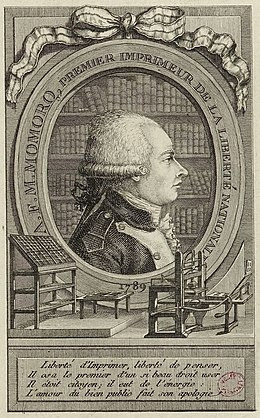

Antoine-François Momoro

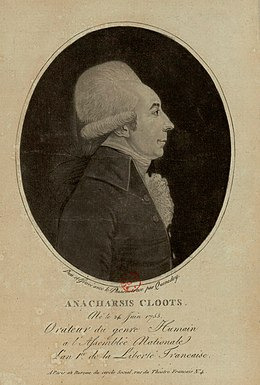

Anacharsis Cloots

Toussaint Louverture

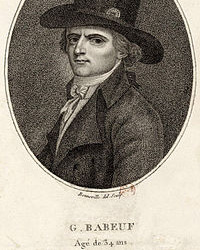

Gracchus Babeuf

Jean-Baptiste Edmond Fleuriot-Lescot

Rosalie Jullien

On the other hand, we have the Paris Commune uprising of 1870, which ended in horrific repression (some estimate that 10,000 people died within a week in the city of Paris).

The origins of this Paris Commune are quite complex to explain, involving the fall of Napoleon III's dictatorship, Bazaine's lamentable behavior, the fact that the new regime forming a republic was composed of monarchists while Paris was predominantly republican, the new regime's abolition of wages, which was one of the only sources of income for workers, and so on.

These Paris communards represented various leftist movements, including the Blanquists, named after Auguste Blanqui (a small anecdote: the composer of "The Internationale" was a communard named Eugène Pottier), anarchists, Proudhonians, as well as centralists like Delescluze (some might even call them Jacobins, though I am not well-informed about that), and even collectivists. The Paris Commune marked a significant shift to the left (albeit briefly). I will mention four measures passed by this government: the abolition of night work (at least for bakers), the separation of Church and State, free, secular, and compulsory education, and the elimination of distinctions between legitimate and illegitimate children.

The repression was atrocious, with death sentences raining down (one of the key figures in the repression, alongside Thiers, was Jules Ferry), and deportations to New Caledonia as well.

It is here that the communards (or at least a significant number of them) were less progressive on certain issues than the main actors of the Convention of Year II. Except for individuals like Louise Michel or Charles Malato, the son of deported communards who followed them to Nouméa, most of the communards did not support the Kanaks at all. There was a lingering racist attitude towards these colonized people, who were also fighting against the injustices imposed on them by the French government. Some even participated in the repression against the Kanaks following the Great Kanak Revolt of 1878, whose main leaders were Atai, chief of Komalé, and Cavio, chief of Nékpi, among others.

I have the impression that the communards behaved similarly toward the deported Algerians. Indeed, in 1869, a significant new insurrection broke out in Algeria, spreading from Kabylie, the Aurès, and towards Algiers, and other territories (the war against France began in 1830, with the defeat of Emir Abdelkader in 1847, the division of three departments in 1848, and the continued Algerian resistance against the establishment of the French colony, notably led by Lalla Fatma N’Soumer and Cherif Boubaghla, though Fatma N'Soumer was captured by the French army in 1857 and died in captivity in 1863 at the age of 33, and Cherif Boubaghla died in combat in 1854; other uprisings lasted until 1870, and one of the most significant was that named Mokrani revolt ).

The insurrection was defeated after fierce fighting, with death sentences raining down, the expulsion of tribes, the sequestration of property, and deportations as well, with around 60 deportees dying from the conditions of deportation. Louise Michel described their arrival in these terms: "We saw them arrive in their great white burnouses, the Arabs deported for having also risen up against oppression. These Orientals, imprisoned far from their tents and flocks, were simple and just, and could not understand the way they had been treated."

They had even fewer privileges than the deported communards. According to some sources, they were chained with red-hot irons, subjected to more intense forced labor, and had to eat soup from the shoes of the jailers. They were forcibly separated from their wives, leading some to marry Kanaks, while others married communard women. It is true that some communards, like Louise Michel and Jean Allemane, campaigned for their amnesty. There were escapes by Algerians, some of whom were recaptured. One of the most famous was Azziz El Haddad, who died in the home of his friend the communard and former deportee Eugène Mourot on August 22, 1895, in Paris. Mourot was also opposed to the colonization of Algeria. A collection by the communards against colonization ensured that his body was repatriated to Algeria.

However, while some deported communards supported them, it should not be forgotten that other communards were driven by colonialist mindsets. It is also interesting to learn more about the Commune of Algiers, proclaimed by Alexandre Lambert, among others. Some European insurgents supported a fraternal republic, but one that excluded Algerian insurgents. Alexandre Lambert, who was killed during the Bloody Week, published a newspaper called Le Colon. The title is quite telling.

Auguste Blanqui

Charles Malato

Jean Allemane

Louise Michel

Eugène Mourot

Bou-Mezrag El-Mokrani, brother of Mohamed El-Mokrani

Cheikh El Haddad father of Aziz el Haddad and Cheikh M'hand

Chérif Boubaghla and Lalla Fatma N'Soumer (Henri Félix Emmanuel Philippoteaux, 1866) alleged portraits

Émir Abdelkader

Ataï

And so, this is the paradox of these two French "revolutionary groups" from 1792-1794, and the group of the Communards from 1870. The first group, still very timid on certain social rights such as property rights (even within the extreme left), was nevertheless much more committed to advocating for more rights among men of different colors, with some even going further by supporting the ideas of revolts by the colonized. Moreover, the colonizers were much less listened to after a certain point in time.

In contrast, during the Paris Commune, while there were more progressive ideas and people who were less conservative about property rights (after all, there was representation from collectivists), they were much less engaged in supporting the colonized and at times even approved of colonial repressions.

Sources: Jean Marc Schiappa Alain Decaux Antoine Resche Mehdi Lallaoui - Kabyles du Pacifique

P.S.: I'm not trying to hand out praise or criticism regarding property rights. I'm merely attempting to make an observation. In fact, I might even be wrong on certain points, so I invite you to correct me. And I don't intend to bash the Paris Communards, many of whom suffered or gave their lives for an ideal Republic, and whose horrific repression we don't often discuss. But it's important to acknowledge everything, including their mistakes. Perhaps one day I should address the question of the French left as a whole, from 1789 to 1962, concerning colonization.

#frev#french revolution#france#commune#Paris Commune#1700s#1800s#algeria#new caledonia#colonization#Kanaks#marat#louise michel#Blanqui#babeuf#sonthonax#toussaint louverture#third republic

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jules Raynal by Daniel Jaems

778 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jules Raynal by Kalle Gustafsson for The Rake

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jules Raynal by Pablo Arroyo (2017)

366 notes

·

View notes

Text

The New York Style Magazine 12 November 2014 - Jules Raynal photographed by Jonathan Grassi

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

>>> Collection Jules Raynal smokes

#1

[ > Models_Smokes* ] [ Source : adraynaline ]

#Jules Raynal#smokingmodels#smokingmodelsnb#shirtlesssmokers#shirtlesssmokersnb#shirtlessnotattoo#shirtlessnotattooblack#cigarette#smokingguys#smokingguysnb

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jules Raynal by Frédéric Monceau for Lui Magazine.

#Photography#Modelling#Grooming#Ambiance#Colour#Frédéric Monceau#Frederic Monceau#Jules Raynal#Lui#Lui Magazine

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

26 notes

·

View notes