#joshua mcfadden

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Digestive system back to normal today! I can eat food that isn’t BRATs for the first time in like 4 days :D

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

early bday gift from my mom yaaaaaaaayyeeeee

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

i was tagged by @bugboychampion a while ago <3

Last song: virginia - las eras

Favorite color: red!

Currently watching: started watching hacks w/ my wife lol

Last movie: finally got around to watching bodies bodies bodies

Sweet/Savory/Spicy: savory 100%

Current obsessions: following museum job postings tbh, taking in the changing leaves before they’re gone 🍂

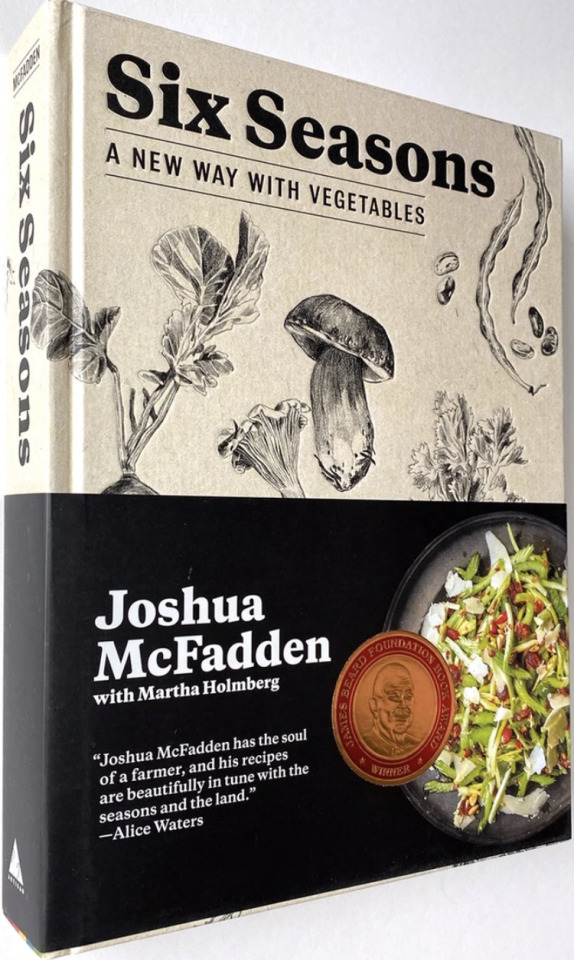

Last thing googled: six seasons by joshua mcfadden (it’s a cookbook)

i tag the girl reading this 🖤 & @rubbertplant

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seasonal Cookbook Recommendations

Farmhouse Rules by Nancy Fuller

Nancy Fuller believes in bringing family together around the table, sharing stories and table manners. Her philosophy is to feed others with delicious, simple meals from the heart. Her straight-shooter approach to cooking will take the hassle out of dinner preparation. Every recipe helps readers to make healthy, authentic cooking their daily standard and shows readers how satisfying freshly cooked comfort food can be.

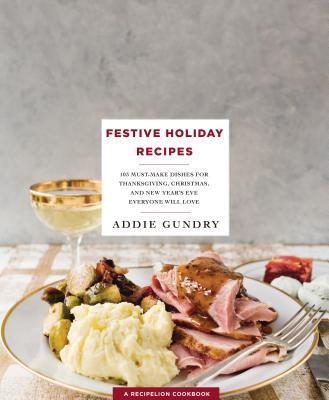

Festive Holiday Recipes by Addie Gundry

In this cookbook, Food Network star Addie Gundry offers easy, delightful holiday recipes for everyone looking for that last minute recipe for entertaining. From appetizers for holiday and New Year's Eve entertaining, like Caramelized Onion Tartlets, to recipes for The Best Roast Turkey and all your favorite sides and pies, this book is a home cook's trusty sous chef for easy and elegant entertaining throughout the holiday season.

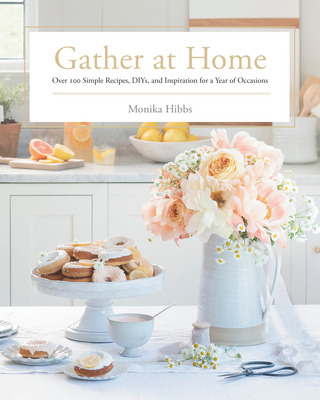

Gather at Home by Monika Hibbs

In this cookbook, Monika Hibbs shares her favourite relaxed and easy ways to make your everyday moments and seasonal celebrations special. Use Monika's collection of over 100 simple recipes, crafts, and do-it-yourself projects, conveniently divided by season, to turn your Friday family games night, Mother's Day brunch, holiday dinner, or outdoor evening barbecue into something memorable.

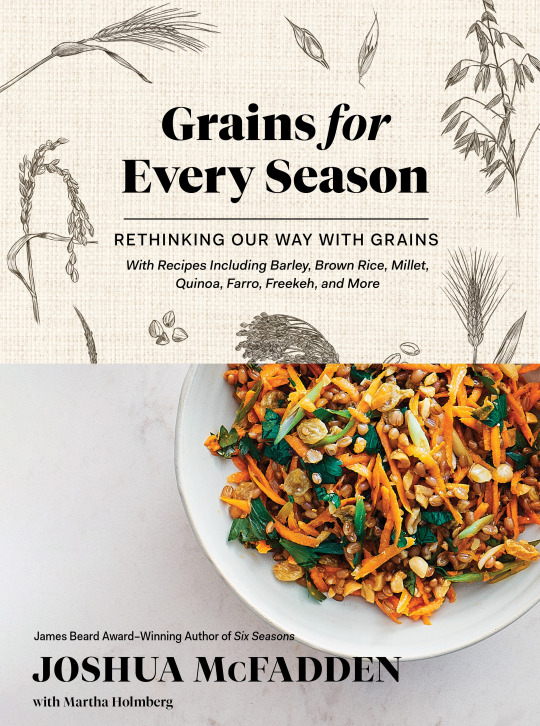

Grains for Every Season by Joshua McFadden

Joshua McFadden is back as he applies his maximalist approach to flavor and texture to cooking with grains. This cookbook’s 200 recipes are organized into chapters by grain type, unlocking information on where each one comes from, how to prepare it, and why the author can’t live without it. This volume will change the way we cook with barley, brown rice, buckwheat, corn, millet, oats, quinoa, rye, wheat, and wild rice.

#cookbooks#seasonal cooking#nonfiction#reading recommendations#reading recs#book recommendations#book recs#library books#tbr#tbr pile#to read#booklr#book tumblr#book blog#library blog#readers advisory

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Death of School 10! How Declining Enrollment Is Threatening The Future of American Public Education.

— By Alec MacGillis | August 26, 2024

The building that housed Rochester’s now shuttered School 10. Such closures “rend the community,” a professor of education said.Photographs by Joshua Rashaad McFadden for The New Yorker

In The Nineteen-Nineties, when Liberia descended into civil war, the Kpor family fled to Ivory Coast. A few years later, in 1999, they were approved for resettlement in the United States, and ended up in Rochester, New York. Janice Kpor, who was eleven at the time, jokingly wonders whether her elders were under the impression that they were moving to New York City. What she remembers most about their arrival is the trees: it was May, yet many were only just starting to bud. “It was, like, ‘Where are we?’ ” she said. “It was completely different.”

But the Kpors adapted and flourished. Janice lived with her father in an affordable-housing complex close to other family members, and she attended the city’s public schools before enrolling in St. John Fisher University, just outside the city, where she got a bachelor’s degree in sociology and African American studies. She found work as a social-service case manager and eventually started running a group home for disabled adults.

She also became highly involved in the schooling of her three children, whom she was raising with her partner, the father of the younger two, a truck driver from Ghana. Education had always been highly valued in her family: one of her grandmothers had been a principal in Liberia, and her mother, who remained there, is a teacher. Last fall, when school started, Kpor was the president of the parent-teacher organization at School 10, the Dr. Walter Cooper Academy, where her youngest child, Thomasena, was in kindergarten. Her middle child had also attended the school.

Kpor took pleasure in dropping by the school, a handsome two-story structure that was built in 1916 and underwent a full renovation and expansion several years ago. The school was in the Nineteenth Ward, in southwest Rochester, a predominantly Black, working- and middle-class neighborhood of century-old homes. The principal, Eva Thomas, oversaw a staff that prided itself on maintaining a warm environment for two hundred and ninety-nine students, from kindergarten through sixth grade, more than ninety per cent of whom were Black or Latino. Student art work filled the hallways, and parent participation was encouraged. School 10 dated only to 2009—the building had housed different programs before that—but it had strong ties to the neighborhood, owing partly to its namesake, a pioneering Black research scientist who, at the age of ninety-five, still made frequent visits to speak to students. “When parents chose to go to this particular school, it was because of the community that they have within our school, the culture that they have,” Kpor told me.

Because she was also engaged in citywide advocacy, through a group called the Parent Leadership Advisory Council, Kpor knew that the Rochester City School District faced major challenges. Enrollment had declined from nearly thirty-four thousand in 2003 to less than twenty-three thousand last year, the result of flight to the suburbs, falling birth rates, and the expansion of local charter schools, whose student population had grown from less than two thousand to nearly eight thousand during that time. Between 2020 and 2022, the district’s enrollment had dropped by more than ten per cent.

The situation in Rochester was a particularly acute example of a nationwide trend. Since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, public-school enrollment has declined by about a million students, and researchers attribute the drop to families switching to private schools—aided by an expansion of voucher programs in many red and purple states—and to homeschooling, which has seen especially strong growth. In addition, as of last year, an estimated fifty thousand students are unaccounted for—many of them are simply not in school.

During the pandemic, Rochester kept its schools closed to in-person instruction longer than any other district in New York besides Buffalo, and throughout the country some of the largest enrollment declines have come in districts that embraced remote learning. Some parents pulled their children out of public schools because they worried about the inadequacy of virtual learning; others did so, after the eventual return to school, because classroom behavior had deteriorated following the hiatus. In these places, a stark reality now looms: schools have far more space than they need, with higher costs for heating and cooling, building upkeep, and staffing than their enrollment justifies. During the pandemic, the federal government gave a hundred and ninety billion dollars to school districts, but that money is about to run dry. Even some relatively prosperous communities face large drops in enrollment: in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where enrollment has fallen by more than a thousand students since the fall of 2019, the city is planning to lay off some ninety teachers; Santa Clara, which is part of Silicon Valley, has seen a decrease of fourteen per cent in a decade.

On September 12, 2023, less than a week after the school year started, Rochester’s school board held what appeared to be a routine subcommittee meeting. The room was mostly empty as the district’s superintendent, Carmine Peluso, presented what the district called a “reconfiguration plan.”

A decade earlier, twenty-six hundred kindergarten students had enrolled in Rochester’s schools—roughly three-quarters of the children born in the city five years before. But in recent years, Peluso said, that proportion had sunk to about half.

Within ten years, Peluso said, “if we continue on this trend and we don’t address this, we’re going to be at a district of under fourteen thousand students.” The fourth-largest city in New York, with a relatively stable population of about two hundred and ten thousand, was projecting that its school system would soon enroll only about a third of the city’s current school-age population.

Peluso then recommended that the Rochester school district close eleven of its forty-five schools at the end of the school year. Kpor, who was watching the meeting online, was taken aback. Five buildings would be shuttered altogether; the other six would be put to use by other schools in the district.

School 10 was among the second group. The school would cease to exist, and its building, with its new gymnasium-auditorium and its light-filled two-story atrium, would be turned over to a public Montessori school for pre-K through sixth grade, which had been sharing space with another school.

Kpor was stunned. The building was newly renovated. She had heard at a recent PTA meeting that its students’ over-all performance was improving. And now it was being shut down? “I was in disbelief,” she said. “It was a stab in the back.”

School Closures Are a Fact of Life in a country as dynamic as the United States. Cities boom, then bust or stagnate, leaving public infrastructure that is incommensurate with present needs. The brick elementary school where I attended kindergarten and first grade, in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, was closed in the early eighties, as the city’s population declined, and then was razed to make way for a shopping plaza.

Still, there is a pathos to a closed school that doesn’t apply to a shuttered courthouse or post office. The abandonment of a building once full of young voices is an indelible sign of the action having moved elsewhere. There is a tangible cost, too. Researchers have found that students whose schools have been closed often experience declines in attendance and achievement, and that they tend to be less likely to graduate from college or find employment. Closures tend to fall disproportionately on majority-Black schools, even beyond what would be expected on the basis of enrollment and performance data. In some cities, efforts to close underpopulated schools have become major political issues. In 2013, Chicago, facing a billion-dollar budget deficit and falling enrollment, closed forty-nine schools, the largest mass closure in the country’s history. After months of marches and protests, twelve thousand students and eleven hundred staff members were displaced.

Now, as a result of the nationwide decline in enrollment, many cities will have to engage in disruption at a previously unseen scale. “School closures are difficult events that rend the community, the fabric of the community,” Thomas Dee, a professor of education at Stanford, said. He has been collecting data on declining enrollment in partnership with the Associated Press. “The concern I have is that it’s going to be yet another layer of the educational harm of the pandemic.”

Janice Kpor knew that her family was, in a sense, part of the problem. Her oldest child, Virginia, had flourished in the early grades, so her school put her on an accelerated track, but it declined to move her up a grade, as Kpor had desired. Wanting her daughter to be sufficiently challenged, Kpor opted for the area’s Urban-Suburban program, in which students can apply to transfer to one of the many smaller school districts that surround Rochester; if a district is interested in a student, it offers the family a slot. The program began in 1965, and there are now about a thousand children enrolled. Virginia began attending school in Brockport, where she had access to more extracurricular activities.

Supporters call Urban-Suburban a step toward integration in a region where city schools are eighty-five per cent Black and Latino and suburban districts are heavily white. But critics see it as a way for suburban districts to draw some of the most engaged families out of the city’s schools; the selectiveness of the suburban districts helps explain why close to a quarter of the students remaining in the city system qualify for special-education services. (The local charter schools are also selective.) One suburban district, Rush-Henrietta, assured residents that it would weed out participants who brought “city issues” with them, as Justin Murphy, a reporter for the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, wrote in his book, “Your Children Are Very Greatly in Danger,” a history of segregation in the city’s schools.

Kpor understood these concerns even as she watched Virginia thrive in the suburbs, then go on to attend the Rochester Institute of Technology. As Kpor saw it, each child’s situation was unique, and she tried to make decisions accordingly. “It’s where they’re at,” she said. “It’s not all or nothing for me.”

She enrolled her middle child, Steven, in School 10 for kindergarten and immediately liked the school, but stability was elusive. First, the school moved to temporary quarters for the renovation. Then came disagreements with a teacher who thought that her son’s behavioral issues stemmed from A.D.H.D. Then the pandemic arrived, and her son spent the final months of second grade and most of third on Zoom. For fourth grade, she decided to try Urban-Suburban again. He was accepted by Brockport, which sent a bus to pick him up every morning.

Other parents shared similar accounts with me of the aftermath of the pandemic closures. Ruthy Brown said that, after the reopening, her children’s school was rowdier than before, with more frequent fights and disturbances in the classroom; a charter school with uniforms suddenly seemed appealing. Isabel Rosa, too, moved her son to a charter school, because his classmates were “going bonkers” when they finally returned to in-person instruction. (She changed her mind after he was bullied by a charter-school security guard.) Carmen Torres, who works at a local advocacy organization, the Children’s Agenda, watched one of her client families get so frustrated by virtual instruction that they switched to homeschooling. “Enough is enough,” Torres recalled the mother saying. “My kids need to learn how to read.”

But, when it came time to enroll Thomasena, Kpor resolved to stick with the district, and she was so hopeful about her daughter’s future at School 10 that she took the prospect of its closure with great umbrage. She and other parents struggled to understand the decision. One of the reasons School 10 was chosen to close was that it was in receivership—a designation for public schools rated in the bottom five per cent in the state, among Peluso’s criteria for closure—but Kpor knew that the receivership was due not only to low test scores but also to the school’s high rate of absenteeism, which was, she believed, because the school roster was outdated, filled with students who were no longer there. According to a board member, the state had also placed School 10 on a list of dangerous schools, partly owing to an incident in which a student had been found with a pocketknife.

Making matters worse, for Kpor, was that the building was going to be turned over to another program, School 53, the Montessori school. It would be one thing for School 10 to be shut down because the district needed to cut costs. But the building had just been renovated at great expense, an investment intended for School 10, and now those students and teachers were being evicted to make room for others. “It was more of an insult,” Kpor said, “because now you have this place and all these kids and a whole bunch of new kids in the same building, so what is the logic of, quote-unquote, closing the school?”

The awkwardness of this was not lost on the parents of School 53. The school had a slightly higher proportion of white families and a lower one of economically disadvantaged students than School 10, and it was expected to draw additional white families once it moved to its new building. “The perception is that you’ve got the kids at this protected, special school—you can see the difference between what they get and what we get,” Robert Rodgers, a parent at School 53, told me. “If I was a parent at School 10, I would be livid.”

After Peluso announced the plan, the district held two public forums, followed by sessions at the targeted schools. The School 10 auditorium was packed for its session, and Kpor lined up at the microphone to speak. She asked Peluso if Thomasena and her classmates would get priority for placement in School 53, so that they could stay in the building. “I do not want her to go to any other school,” she said. “Every time we think we’re doing something right for our kids, someone comes in and dictates to us that our choices are not valid.” Kpor was encouraged to hear Peluso say that School 10 kids would get priority.

Janice Kpor, whose youngest child had just started at School 10 when the city announced its closure.

On October 19th, five weeks after the announcement, the school board met to vote on the closures. During the public-comment period, a teacher from School 2 pleaded with the board to let its students enroll at the school that would be replacing it. A teacher from School 106 asked that the vote be delayed until after board members visited every school, including hers, which was engaged in a yearlong special project geared toward the coming total solar eclipse, so that they could get a more visceral sense of the school’s value. The principal of School 29, Joseph Baldino, asked that the school’s many students with autism-spectrum disorder be kept together, along with their teachers, during the reassignment. “They’re unique, they’re beautiful, and they don’t do real well with change,” he said. Chrissy Miller, a parent at the school, said of her son, ���He loves his staff . . . he loves his teachers, and he wants everybody to stay together as one.”

In the end, the closures passed, five to two.

In September, 2020, as many public schools in Democratic-leaning states started the new academic year with remote learning, I asked Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers, whether she worried about the long-term effects on public education. What if too many families left the system in favor of homeschooling or private schools—many of which had reopened—and didn’t come back? She wasn’t concerned about such hypotheticals. “At the end of the day, kids need to be together in community,” she said.

The news from a growing number of districts suggests that the institution of public schooling has indeed suffered a lasting blow, even in cities that are better funded than Rochester. In Seattle, parents anticipate the closure of twenty elementary schools. The state of Ohio has witnessed a major expansion of private-school vouchers; in Columbus, a task force is recommending the closure of nine schools.

In Rochester, the continuing effects of the pandemic weighed heavily on some. Camille Simmons, who joined the school board in 2021, told me, “A lot of children felt the result of those decisions.” She went on, “There were a lot of entities at play, there were so many conversations going on. I think we should have brought children back much sooner.”

Adam Urbanski, the longtime president of the Rochester teachers’ union, said that the union had believed schools should not reopen until the district could guarantee high air quality, and it had not been able to. “When I reflect back on it, I know that I erred on the side of safety, and I do not regret the position that we took,” he said.

But Rebecca Hetherington, the owner of a small embroidery company and the former head of the Parent Leadership Advisory Council, the group Kpor was part of, feared that the district would soon lack the critical mass to remain viable. “I am concerned there is a tipping point and we’re past it,” she said. Rachel Barnhart, a former TV news reporter who attended city schools and now serves in the county legislature, agreed. “It’s like you’re watching institutions decline in real time,” she told me. “Anchors of the community are disappearing.” School districts have long aspired to imbue their communities with certain shared values and learning standards, but such commonality now seemed inconceivable.

By the spring of 2024, parents at the eleven targeted schools were too busy trying to figure out where their children would be going in the fall to worry about the long term. A mother at School 39, Rachel Dixon, who lived so close to the school that she could carry her kindergartner there, was on the wait list for School 52 but had been assigned to School 50. She wasn’t even sure where that was. Chrissy Miller was upset that School 29’s students with autism were being more broadly dispersed than promised; she worried that her son’s assigned school wasn’t equipped for students with special needs. Many of her fellow School 29 parents were now considering homeschooling or moving, she said, and added, “We don’t have trust in the district at all.” It was easy to envision how the closures could compound the problem, leading to even fewer students and even more closures.

Thomasena had been assigned to School 45, which was close to her family’s home but less convenient for Kpor than School 10, which was closer to her work. Kpor wondered how many other families were in similar situations, with assignments that didn’t take into account the specific context of their lives. “All of this plays into why kids are not going to school,” she said. “You’re placing kids in locations that don’t meet the families’ needs.”

She had taken Peluso’s word that students from School 10 would be given priority at the Montessori school taking its place, and she was disappointed to learn that Thomasena was thirtieth on the wait list there. It was also unclear to her which branch of the central office was handling placement appeals. “It’s all a jumble, and no one really knows how things work,” she said.

On March 26th, as families were dealing with the overhaul, Peluso announced that he was leaving the district to become the superintendent of the Churchville-Chili district, in the suburbs. The district was far smaller than Rochester, with some thirty-eight hundred students, more than seventy per cent of them white, but the job paid nearly as much. “It’s one of the hardest decisions I’ve had,” Peluso said at a news conference. “There’s a lot of commitment I’ve had to this district.” Rodgers, the School 53 parent, told me, “This hurts. It’s another situation where the suburbs are taking something from the city.”

Parents and district staff tried to make sense of Peluso’s departure. Some people speculated that he had grown tired of the treatment he was receiving from certain board members. Other people wondered if he simply wanted a less challenging district. Peluso told me, “It was the best decision for me and my family.”

In Late June, I returned to Rochester for the final days of the school year. I stayed at School 31 Lofts, a hotel in a former schoolhouse that was built in 1919. (The Web site advertises “WhimsyHistorySerenity.”) An empty hallway was still marked with a “Fallout Shelter” sign. I stayed in a room that, judging from its size and location, might have been a faculty lounge.

One afternoon, I met with Demario Strickland, a deputy superintendent who’d been named interim superintendent while the school board searched for a permanent replacement for Peluso. Strickland, a genial thirty-nine-year-old Buffalo native who moved to Rochester last year, was the seventh superintendent of the district since 2016. He told me that he was not surprised the closures had prompted such protests. “School closures are traumatic in itself,” he said.

But he defended the district against several of the criticisms I had heard from parents. School 10 had been improving, he said, but still fell short on some metrics. “Even though they met demonstrable progress, we still had to look at proficiency, and we still had to look at receivership,” he said. And, he added, School 53 had limited slots available, so the district had made no promises to parents of School 10 about having priority.

Still, he said, the district could perhaps have been more empathetic in its approach. “This process has taught me that, in a sense, people don’t care about the money,” he said. “When you make these decisions, you really have to think about the heart. That’s something we could have done a little more. It makes sense—we’re wasting money, throwing money away, we have all these vacancies, that makes sense to us. But our families don’t care about that. Our families want their school to stay open—they don’t want to do away with it.”

At the end of the academic year, Rochester closed eleven of its forty-five schools, including School 39.

I asked him whether he worried that the district’s enrollment decline might continue until the system could no longer sustain itself, as Hetherington and Barnhart feared. “I try not to get scared about the future,” he said.

On the second-to-last day of the school year, I went to School 10 to join Kpor at the end-of-year ceremony for Thomasena’s kindergarten class. She and her fourteen classmates sang songs, demonstrated spelling on the whiteboard, and rose one by one to say what they had liked best about kindergarten. “Education and learning,” Thomasena, a tall girl with her front teeth just coming in, said. “When it’s the weekend,” one boy said, to the laughter of parents.

It was not hard to see why Kpor and other parents were sorry to leave the school, with its gleaming new tile work and hardwood-composite hallway floorboards. A few weeks earlier, the latest assessment results had shown improvement for School 10, putting it close to citywide averages. “All of us are going to be going to different places, but I hope one day that I get to see you again,” the class’s teacher, Karen Lewis, said.

Kpor was still waiting to find out if she had moved up on the list for School 53. I asked if she might have Thomasena apply for Urban-Suburban, like her siblings, and she said she was hoping it would work out in the district. “I still have faith,” she said. Outside, I met a parent who was worried about how her daughter would fare at her new school after having been at School 10 with the same special-needs classmates and teacher for the past three years. “The school has been amazing,” she said.

The Next Day, I attended a school-wide Rites of Achievement ceremony in the gym. Parents cheered as students received awards for Dr. Walter Cooper Character Traits—Responsibility, Integrity, Compassion, Leadership, Perseverance, and Courage. (Thomasena won for Courage.) Thomas, the principal, called up the school’s entire staff, name by name. The shrieks from the assembled children for their favorite teachers and aides indicated the hold that even a school officially deemed subpar can have on its students and families: this had been their home, a hundred and eighty days a year, for as long as seven years.

Walter Cooper himself was there, watching from a thronelike chair with gilt edges. Eventually, he addressed the children for the last time, recounting his upbringing with a father who had received no formal schooling, a mother who preached the value of education, and six siblings, all but one of whom had gone to college. “The rule was we had to have a library card at seven. We didn’t have a lot in this community, but we had books,” he said. “There are always things in the street for you, but there is much more in books. . . . The guiding thesis is: books will set you free.”

The children sang a final song: “I am a Cooper kid, a Dr. Walter Cooper kid, I am, I am / I stand up for what’s right, even when the world is wrong.” Sylvia Cooksey, a retired administrator who is also a pastor, gave the final speech. “No matter where you go, where you end up, you are taking part of this school with you,” she said. “You are taking Dr. Walter Cooper with you. We’re going to hear all over Rochester, ‘That child is from School 10.’ ”

After the assembly, I asked Cooper what he made of the closure. “It’s tragic,” he said. “It points to the fundamental instability in the future of the schools. Children need stability, and they aren’t getting it in terms of the educational process.”

Wanda Zawadzki, a physical-education teacher who had worked at the school for eight years and received some of the loudest shrieks from the kids, stood looking forlorn. She recalled the time a class had persuaded the city to tear down an abandoned house across the street, and the time a boy had brought her smartphone to her after she dropped it outside. “My other school, that phone would have been gone,” she said. “It’s the integrity here.” Like many teachers at the targeted schools, she was still waiting for her transfer assignment. “This was supposed to be my last home,” she said.

And then it was dismissal time. It was school tradition to have the staff come out at the end of every school year and wave at the departing buses as they did two ceremonial loops around the block. Speakers blared music from the back of a pickup, and the teachers danced and waved. “We love you,” Principal Thomas called out.

It was quieter over at School 29, the school with many special-needs kids. The children were gone, and one teacher, Latoya Crockton-Brown, walked alone to her car. She had spent nineteen years at the school, which will be closing completely. “We’re not doing well at all,” she said, of herself and her colleagues. “This was a family school. It’s very disheartening. Even the children cried today.”

She was wearing a T-shirt that read “Forever School 29 / 1965 to Now.” The school had done a lot in recent days to aid the transition—bringing in a snow-cone truck and a cotton-candy machine, hosting a school dance. “One girl said she feels like she’s never going to make friends like she had here,” Crockton-Brown said. “But we have to move on. We have no other choice.” ♦

— This Article is a Collaboration Between The New Yorker and ProPublica. ProPublica is a Nonprofit Newsroom that Investigates Abuses of Power. Published in the Print Edition of the September 2, 2024, Issue, with the Headline “The Last Day.”

#Article#American Chronicles#The New Yorker#ProPublica#“The Last Day”#The Death of School#Declining Enrollment#American Public Education#A Gravely Threath#Alec MacGillis#Alec MacGillis | Reporter | ProPublica | Author ✍️ | “Fulfillment: America in the Shadow of Amazon”

0 notes

Text

What is my concept? what is it?

"A Grey Area" - The theme of identity and self is central to the project. Each person is unique, and no human is either black or white. But we all fall into the grey area and have our own identity.

I came to the realization that I had lost my connection with my theme and ideas, and I couldn't quite put my finger on what was wrong. Although everything made sense in my head, I found it difficult to express and communicate my ideas to others. It was only after taking a step back that I realized I had been avoiding projects that revolved around me because I was afraid of being in front of the camera. But if I wanted to convey the concept of the grey area, it had to be through me and only me, as I knew myself better than anyone else.

And this is where that journey got a little better.

The moment I walked into the darkroom, I was immediately drawn to the bulletin board hanging outside. It showcased a collection of stunning and distinct portraits that left a lasting impression on me. I couldn't help but wonder about the artist behind those captivating images and how they managed to create such impactful and evocative pieces. Their work seemed to express a deep sense of understanding and vulnerability, as if they were confronting the judgment and expectations of society head-on.

Artists Inspiration

Antonia Gruber's TTC Series

"This series is intended to be viewed as a photographic examination of human physical and psychological fragility. The works highlight the disparity between self-portraiture and self-perception. The deformed black-and-white portraits are digital photos that have undergone analog manipulation."

This series truly got to me. Because through each image you could feel the fragility of a human. And I can say this was my inspiration. Somewhere I knew before starting my FMP.

I had a vision to create a project that explored the themes of identity and community. I was eager to try out new things and explore different techniques, and I became overwhelmed with the possibilities. I found myself wanting to pursue multiple projects that didn't have any clear connection to each other, and I struggled to find a cohesive direction.

Eventually, I realized that I needed to incorporate myself into the project and confront my fear of being in front of the camera. I scaled back my ideas and focused on three projects that made sense to me, but I still struggled to articulate my vision to others. It wasn't until I took a step back and put myself in the picture that everything fell into place.

Artists Inspiration

Gillian Wearing: Her photographs explore how the public and private identities of ordinary people are self-made and documented. She uses portraits and self-portraits to explore identity. But instead of documenting her own look , she takes on other people’s looks. By dressing up and posing as other people and create a changed identity. Or even getting strangers to express things they usually would not say out loud

Gauri Gill: is an Indian photographer known for her documentary-style work that often focuses on marginalized communities and individuals. Gill blurs the boundaries between traditional documentary photography and staged or performative photography. The surreal and dreamlike quality of the photographs invites the viewer to question their own assumptions about identity and representation, highlighting the ways in which cultural identity can be both constructed and performed.

Joshua Rashaad McFadden: is a photographer known for exploring issues of identity, race, and family, often drawing on his personal experiences growing up as a Black man in America. Through his art, he strives to encourage the audience to acknowledge the humanity of individuals who have been labeled as invisible, and to bring to light stories that deserve to be heard, recognized, and empathized with.

Chloe Sheppard: is a photographer who creates intimate self-portraits that explore themes of mental health, body image, and self-acceptance. Sheppard's work is characterised by its raw emotional power and its use of colour and composition to create images that are both beautiful and unsettling to the common eye.

My Flow & THE CHANGE

By putting myself at the center of my project, everything finally clicked into place. I had to confront my fears and step out of my comfort zone to create something meaningful. The concept of "Only I Know Myself, I Don't Know Anyone Else Better Than I Know Myself" became clear to me.

The project consists of three parts. In part one, I will photograph a crowd or group of people. In part two, I will zoom in on one person in the group while intentionally blurring out everyone else to create a contrast that highlights the individual. Finally, in part three, everyone disappears and it's just me, emphasizing that my identity is unique and personal.

To convey the understanding of a person's identity, I will use black and white and color, as well as different focal lengths to represent the stages of getting to know someone. Initially, everyone is seen in black and white, but as we get closer to a person, we begin to see their colors. This project is an exploration of identity and self-discovery through the lens of photography.

0 notes

Photo

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

The pie creator sez:

The pie has a soft, delicate texture reminiscent of a pumpkin pie (though the slices won't hold their shape as well as pumpkin pie), but it's distinctly carrot and deliberately not too sweet. The pecan crust adds a touch of richness. A plain slice is also very good for breakfast.

0 notes

Photo

Six Seasons | Joshua McFadden

Go-To Recipes

Crunchy

Torn Croutons

Dried Breadcrumbs

Brined and Roasted Almonds

Toasted Nuts and Seeds

Frico

Creamy: Butters/Whipped Cheese

Alla Diavola Butter

Cacio e Pepe Butter

Green Garlic Butter

Mushroom Butter

Pickled Vegetable Butter

Watercress Butter

Brown Butter

Pistachio Butter

Whipped Ricotta

Whipped Feta

Sauces, Dips, and Dressings

Caper-Raisin Vinaigrette

Pancetta Vinaigrette

Pine Nut Vinaigrette

Citrus Vinaigrette

Lemon Cream

Green Herb Mayonnaise

Artichoke Mayonnaise

Pickled Vegetable Mayonnaise

Spicy Fish-Sauce Sauce

Classic Salsa Verde

Pickle Salsa Verde

Radish and Mint Salsa Verde

Spiced Green Sauce

Tonnato

Breads, Pastries, and Grains

Whole-Grain Carta di Musica

Slightly Tangy Flatbreads

Pecan Dough

Very Flaky Pastry Dough

Farro

Freekeh

Couscous

Batter for Fried Vegetables

Other

Soft-Cooked Eggs

Smashing /Toasting Garlic

Making Scallions Mild and Crisp

Basic Vegetable Pickle Brine

Hot/Cold Brine

Spring

Raw Artichoke Salad w Herbs, Almonds, and Parmigiano

Artichoke and Farro Salad w Salami and Herbs

Grilled Artichokes w Artichoke Parmigiano Dip

Raw Asparagus Salad w Breadcrumbs, Walnuts, and Mint

Asparagus, Nettle, and Green Garlic Frittata

Asparagus, Garlic Chives, and Pea Shoots, w or w/o an Egg

Grilled Asparagus w Fava Beans and Walnuts

Vignole

English Pea Toast

English Pea and Pickled Carrot Salsa Verde

English Peas w Prosciutto and New Potatoes

Pasta Carbonara w English Peas

Couscous w English Peas, Apricots, and Lamb Meatballs

Smashed Fava Beans, Pecorino, and Mint on Toast

Fava, Farro, Pecorino, and Salami Salad

Fava and Pistachio Pesto on Pasta

Fava Beans, Cilantro, New Potatoes, and Baked Eggs

“Herbed” Butter w Warm Bread

Little Gems w Lemon Cream, Spring Onion, Radish, and Mint

Butter Lettuce w New Potatoes, Eggs, and Pancetta Vinaigrette

Bitter Greens Salad w Melted Cheese

Sautéed Greens with Olives (Misticanza)

Agrodolce Ramps on Grilled Bread

Leeks w Anchovy and Soft-Boiled Eggs

Charred Scallion Salsa Verde

Onions Three Ways, w ‘Nduja on Grilled Bread

Radishes w Tonnato, Sunflower Seeds, and Lemon

Grilled Radishes w Dates, Apples, and Radish Tops

Roasted Radishes w Brown Butter, Chile, and Honey

Sugar Snap Peas w Pickled Cherries and Peanuts

Sugar Snap Peas w Mustard Seeds and Tarragon

Sugar Snap Pea and New Potato Salad w Crumbled Egg and Sardines

Pasta all Gricia w Slivered Sugar Snap Peas

Crispy Sugar Snap Peas w Tonnato and Lemon

Early Summer

Beet Slaw w Pistachios and Raisins

Roasted Beets, Avocado, and Sunflower Seeds

Carrots, Dates, and Olives w Crème Fraîche and Frico

Grilled Carrots, Steak, and Red Onion w Spicy Fish-Sauce Sauce

Pan-Roasted Carrots w Carrot-Top Salsa Verde, Avocado, Seared Squid

Lamb Ragu w Carrots and Green Garlic

Celery Salad w Dates, Almonds, and Parmigiano

Celery Puntarelle-Style

Celery, Sausage, Provolone, Olives, and Pickled Peppers

Celery, Apple, and Peanut Salad

Cream of Celery Soup

Celery Gratin

Braised Celery and Radicchio Salad w Perfect Roast Chicken

Chilled Seafood Salad w Fennel, Radish, Basil, and Crème Fraîche

Roasted Fennel w Apples, Taleggio Cheese, and Almonds

Fennel Two Ways w Mussels and Couscous

Smashed New Potatoes w Lemon and Lots of Olive Oil

Potato and Roasted Cauliflower Salad w Olives, Feta, and Arugula

Pan-Roasted New Potatoes with Butters

Turnip Salad w Yogurt, Herbs, and Poppy Seeds

Sautéed Turnips w Prunes and Radicchio

Midsummer

Smashed Broccoli and Potatoes w Parmigiano and Lemon

Pan-Steamed Broccoli w Sesame Seeds, Parmigiano, and Lemon

Rigatoni w Broccoli and Sausage

“Chinese” Beef and Broccoli

Charred Broccoli w Tonnato, Pecorino, Lemon, and Chiles

Broccoli Rabe, Mozzarella, Anchovy, and Spicy Tomato

Raw “Couscous” Cauliflower w Almonds, Dried Cherries and Sumac

Roasted Cauliflower, Plums, Sesame Seeds, and Yogurt

Cauliflower Ragu

Cauliflower Steak w Provolone and Pickled Peppers

Baked Cauliflower w Salt Cod, Currants, and Pine Nuts

Fried Cauliflower w Spicy Fish-Sauce Sauce

Cucumbers, Celery, Apricots, and Pistachios

Cucumbers, Yogurt, Rose, Walnuts, and Herbs

Lemon Cucumbers w Onion, Papalo, and Lots of Herbs

Cucumbers, Scallions, Mint, and Dried Chiles

String Beans, Pickled Beans, Tomatoes, Cucumbers, Olives on Tonnato

Roasted String Beans and Scallions w Pine Nut Vinaigrette

Green Bean, Tuna, and Mushroom “Casserole”

Grilled Wax/Green Beans w Tomatoes, Basil, Spicy Fish-Sauce Sauce

Squash Ribbons w Tomatoes, Peanuts, Basil, Mint, Spicy Fish-Sauce

Grilled or Roasted Summer Squash w Caper-Raisin Vinaigrette

Squash and “Tuna Melt” Casserole

Fried Stuffed Zucchini Flowers, Zucchini Jojos, and Zucchini Pickles

Late Summer

Raw Corn w Walnuts, Mint, and Chiles

Corn and Tomato Salad w Torn Croutons

Sautéed Corn w Scallions

Sautéed Corn w Cream and Melting Cheese

Sautéed Corn w Pancetta, Black Pepper, Arugula, Hot Sauce

Grilled Corn w Alla Diavola Butter and Pecorino

Corn, Tomatoes, and Clams on Grilled Bread, Knife-and-Fork-Style

Corn Fritters w Pickled Chiles

Carta di Musica w Roasted Eggplant Spread, Herbs, and Ricotta Salad

Roasted Eggplant Spread

Grilled Eggplant w Tomatoes, Torn Croutons, and Lots of Herbs

Rigatoni and Eggplant all Norma

Braised Eggplant and Lamb w Yogurt and Spiced Green Sauce

Preserved Eggplant

Roasted Pepper Panzanella

Peperonata

Red Pepper, Potato, and Prosciutto Frittata Topped w Ricotta

Cheese-Stuffed and Pan-Fried Sweet Peppers

Sweet and Hot Peppers, ‘Nduja, and Melted Cheese

Perfect Shell Beans

Beans on Toast

Beans and Pasta

Risotto w Shell Beans, Sausage, and Bitter Greens

Crunchy Mixed-Bean Salad w Celery and Tarragon

Tomato-Rubbed Grilled Bread Topped w Tomato Salad

Farro w Tomatoes, Raw Corn, Mint, Basil, and Scallions

Tomato, Melon, and Hot Chile Salad w Burrata

Israeli-Spiced Tomatoes, Yogurt Sauce, and Chickpeas

Spaghetti w Small Tomatoes, Garlic, Basil, and Chiles

Tomato Soup w Arugula, Torn Croutons, and Pecorino

Grilled Green Tomatoes w Avocado, Feta, and Watermelon

Tomato Conserva

Fall

Roasted Beet, Citrus, and Olive Salad w Horseradish

Roasted and Smashed Beets w Spiced Green Sauce

Roasted Beets and Carrots w Couscous, Sunflower Seeds, Citrus, Feta

Raw Brussels Sprouts w Lemon, anchovy, Walnuts, and Pecorino

Brussels Sprouts w Pickled Carrots, Walnuts, Cilantro, Citrus Vinaigrette

Gratin of Brussels Sprouts, Gruyère. and Prosciutto

Roasted Brussels Sprouts w Pancetta Vinaigrette

Farro and Roasted Carrot Salad w Apricots, Pistachios, Whipped Feta

Grated Carrot Salad w Grilled Scallions, Walnuts, and Burrata

Burnt Carrots w Honey, Black Pepper, Butter, and Almonds

Carrot Pie in a Pecan Crust

Rainbow Chard w Garlic and Jalapeños

Spaghetti w Swiss Chard, Pine Nuts, Raisins, and Chiles

Swiss Chard, Leek, Herb, and Ricotta Crostata

Shaved Collard Greens w Cashews and Pickled Peppers

Collards w Freekeh, Hazelnuts, and Grapes

Swewed Collards w Beans and a Parmigiano Rind

The Kale Salad That Started It All

Wilted Kale Alone or Pickled on Cheese Toast

Kale Sauce w Any Noodle

Cocannon w Watercress Butter

Kale and Mushroom Lasagna

Double-Mushroom Toast w Bottarga

Roasted Mushrooms, Gremolata-Style

Mushrooms, Sausage, and Rigatoni

Sautéed Mushrooms and Mussels in Cream on Sliced Steak

Crispy Mushrooms w Green Herb Mayonnaise

Winter

Steamed Cabbage w Lemon, Butter, and Thyme

Roasted Cabbage, w Walnuts, Parmigiano, and Saba

Battered and Fried Cabbage w Crispy Seeds and Lemon

Comforting Cabbage, Onion, and Farro Soup

Cabbage and Mushroom Hand Pies

Celery Root w Brown Butter, Oranges, Dates, and Almonds

Mashed Celery Root with Garlic and Thyme

Celery Root, Cracked Wheat, Every-Fall-Vegetable-You-Can-Find Chowder

Fried Celery Root Steaks w Citrus and Horseradish

Kohlrabi w Citrus, Arugula, Poppy Seeds, and Crème Fraîche

Kohlrabi Brandade

Onions and Pancetta Tart

Onion Bread Soup w Sausage

Braised Beef w Lots and Lots of Onions

Parsnips w Citrus and Olives

Parsnip Soup w Pine Nut, Currant, and Celery Leaf Relish

Parsnip, Date, and Hazelnut Loaf Cake w Meyer Lemon Glaze

Fried Potato and Cheese Pancake

Crushed and Fried Potatoes w Crispy Herbs and Garlic

Mashed Rutabaga w Watercress and Watercress Butter

Rutabaga w Maple Syrup, Black Pepper, and Rosemary

Smashed Rutabaga w Apples and Ham

Half-Steamed Turnips w Alla Diavola Butter

Roasted Turnips w Caper-Raisin Vinaigrette and Breadcrumbs

Turnip, Leek, and Potato Soup

Freekah, Mushrooms, Turnips, Almonds

Raw Winter Squash w Brown Butter, Pecans, and Currants

Winter Squash and Leek Risotto

Fontina-Stuffed Arancini

Delicata Squash “Donuts” w Pumpkin Seeds and Honey

Roasted Squash w Yogurt, Walnuts, and Spiced Green Sauce

Pumpkin Bolognese

#six seasons#joshua mcfadden#vegetable cooking#vegetables#vegetarian#vegetarian cookbook#vegetable cookbook#vegetarian cooking

0 notes

Text

how scared are you right now pickles

I try to stay off Twitter these days because I’m trying to live a more positive and productive life and getting drunk five nights a week and yelling at strangers on the internet is not an integral part of that plan. Also, my family members have started following me and “liking” my tweets about farts and cussing, which makes the prospect of doing tweets about farts and cussing -- otherwise a large part of my brand -- rather less enticing.

As a result, I spend more time on Facebook, yelling at the friends and relatives of people I care about, because I give very few fucks at this particular juncture and if your ex-husband thinks bitches need to “settle down” about that Google dude who Google-emailed his Google-colleagues about how women are naturally bad at computers, I have no qualms whatsoever about giving him a piece or two of my mind. I love going on Facebook to yell at Uncle Breitballs.

But this afternoon I logged on to find my friend Dan asking a question that, to be honest, I was not planning on entertaining. I was just gonna pop in to tell some middle-aged white women with MAGA avatars to fuck off and go about my day. Instead, Dan asked: “How scared are you, right now, of yourself or someone you love dying because of a nuclear war?”

Wait. Does Dan mean like, the residual low-level fear of knowing a man with the moral and emotional strength of cheap toilet paper has the nuclear codes? Or like, did a thing happen?

A thing happened. North Korea says they’re gonna attack Guam, and Donald Trump is going to blow up the entire goddamned planet to teach North Korea a lesson. I mean, or it’s just a couple of wildly insecure men who don’t give a fuck about turning the mental health and physical safety of tens of millions of people into collateral damage in their dim dude pissing contest.

I decided to make pickles, because either I’m going to eat the pickles, or the people who ransack my decimated home in the aftermath of a nuclear strike will eat the pickles. They will have Joshua McFadden’s Six Seasons cookbook to thank for them.

HOW SCARED ARE YOU RIGHT NOW PICKLES

BRINE:

Half a cup of rice vinegar

a tablespoon of white wine vinegar (I used sherry vinegar, who cares)

1.5 cups of hot water (I used hot tap water, I guess you could kettle it)

5 tablespoons of sugar (I might accidentally have put in six)

1 tablespoon of kosher salt

VEGETABLES:

Some green beans or carrots or radishes or whatever else you ripped from the limp grip of a neighbor dying of radiation poisoning.

also some garlic cloves, smashed

DIRECTIONS:

Put all that shit together and stir it until the seasonings dissolve. Put your veggies in a jar with the smashed garlic cloves and pour over the brine. Refrigerate and eat until your extremities wither.

246 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Dungeon Meshi renaissance is making me want to share the resources that taught me how to cook.

Don’t forget, you can check out cookbooks from the library!

Smitten Kitchen: The rare recipe blog where the blog part is genuinely good & engaging, but more important: this is a home cook who writes for home cooks. If Deb recommends you do something with an extra step, it’s because it’s worth it. Her recipes are reliable & have descriptive instructions that walk you through processes. Her three cookbooks are mostly recipes not already on the site, & there are treasures in each of them.

Six Seasons: A New Way With Vegetables by Joshua McFadden: This is a great guide to seasonal produce & vegetable-forward cooking, and in addition to introducing me to new-to-me vegetables (and how to select them) it quietly taught me a number of things like ‘how to make a tasty and interesting puréed soup of any root veggie’ and ‘how to make grain salads’ and ‘how to make condiments’.

Grains for Every Season: Rethinking Our Way With Grains by Joshua McFadden: in addition to infodumping in grains, this codifies some of the formulas I picked up unconsciously just by cooking a lot from the previous book. I get a lot of mileage out of the grain bowl mix-and-match formulas (he’s not lying, you can do a citrus vinaigrette and a ranch dressing dupe made with yogurt, onion powder, and garlic powder IN THE SAME DISH and it’s great.)

SALT, FAT, ACID, HEAT by Samin Nosrat: An education in cooking theory & specific techniques. I came to it late but I think it would be a good intro book for people who like to front-load on theory. It taught me how to roast a whole chicken and now I can just, like, do that.

I Dream Of Dinner (so you don’t have to) by Ali Slagle: Ok, look, an important part of learning to cook & cooking regularly is getting kinda burned out and just wanting someone else to tell you what to make. These dinners work well as written and are also great tweakable bases you can use as a starting place.

If you have books or other resources that taught you to cook or that you find indispensable, add ‘em on a reblog.

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

saw my gf last night and we made pearl barley risotto style with shell beans, sausage, dandelion greens + arugula and a salad also with dandelion greens, arugula, shiso leaves, kohlrabi, + pod beans with a blueberry vinagrette

#the risotto is our take on joshua mcfadden's take on a marcella hazan recipe#every time we get together it takes us three hours to cook dinner at a MINIMUM it rules

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Raw Asparagus Salad with Breadcrumbs, Walnuts, and Mint

#Raw Asparagus Salad with Breadcrumbs Walnuts and Mint#asparagus#asparagus salad#joshua mcfadden#six seasons cookbook#Six Seasons: A New Way with Vegetables cookbook#Six Seasons: A New Way with Vegetables

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Photo

What are you reading (or cooking from) this weekend?

32 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

NICOLE ATKINS - “Domino”, off her new album 'Italian Ice' out now via Single Lock Records.

Director - Taylor McFadden

Director of Photography - Joshua Shoemaker

#nicole atkins#music video#new music#2020#single lock records#taylor mcfadden#joshua shoemaker#indie pop

23 notes

·

View notes