#jolicure

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Le photographe qui m’a le plus intéressée est Thaddeus Holownia. Dans la majorité de ses tirages, il explore les traces que l'humanité laisse sur le paysage. J’ai beaucoup aimé ce photographe en raison de son sujet, qu’il photographie en noir et blanc et parfois aussi en couleur. De plus, j’aime bien aussi le fait qu’il utilise un appareil plus ancien malgré les multiples choix plus moderne qui existe. J'adore plus particulièrement cette série de photos pour les couleurs et la lumière douce capturées par Thaddeus.

Pour ce tirage ci-dessus, Thaddeus examine le visage changeant de la lumière au-dessus de l'horizon et celles du paysage et en particulier de la surface de l'étang artificiel situé sous sa maison au Nouveau-Brunswick.

Sources : https://holownia.com/photographs/jolicure-pond/

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

a wet december day in Jolicure, NB

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Anchorage Press

In 1977 when Holownia went to New Brunswick to teach in the arts department in Mount Allison University, he brought his concepts with him. Being the resourceful artist, he had actually started getting chances and sods of printing devices that were being retired from regional printshops.

He thought that an active press had the possibility of being a centre of cultural activity not just in the school however in the neighborhood. By fall of 1987, the Anchorage Press was moved out from the library and into the addition at Jolicure.

ended up being a personal press with the transfer to Jolicure in 1987. For many years, the Anchorage Press has actually produced books, exhibit brochures and ephemera for the university, along with casting the names in lead of the Mount Allison graduates and printing them on the university’s diplomas. The university and the neighborhood has actually in some way benefited on Holownia’s Anchorage Press, not to discuss his kindness of mentor in the university.

is a working lab of letterpress devices committed to the research study of great typography and ingenious collaboration of image and text. lies in Jolicure, New Brunswick and has actually served a mentor studio for the trainees of Mount Allison University under the lead of Thaddeus Holownia for over a years.

In about 1983, he had the ability to develop a short-term print-shop that bent in the basement of the university’s library. In an effort to motivate interest in printing and print history in the neighborhood, he assisted arrange the 1987 Anchorage Symposium on Printing and Publishing in Atlantic Canada in concurrence with the University’s Centre for Canadian Studies. This occasion was very little to what Holownia gotten out of the arts neighborhood that he anticipated.

established out of Holownia’s understanding as an interactions and great arts trainee in Windsor, Ontario and his experiences as a young artist in Toronto throughout the late 1960′s and early 1970′s. His participation with an artist-run gallery called A Space provided method to his satisfying imaginative individuals from numerous fields consisting of individuals from Coach House Press.

0 notes

Text

The Elephant in the Room

The Nature of Nature: The Photographs of Thaddeus Holownia, 1976-2016. At the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, February 4 to May 28, 2017. Curated by David Diviney and Sarah Fillmore.

By John Haney

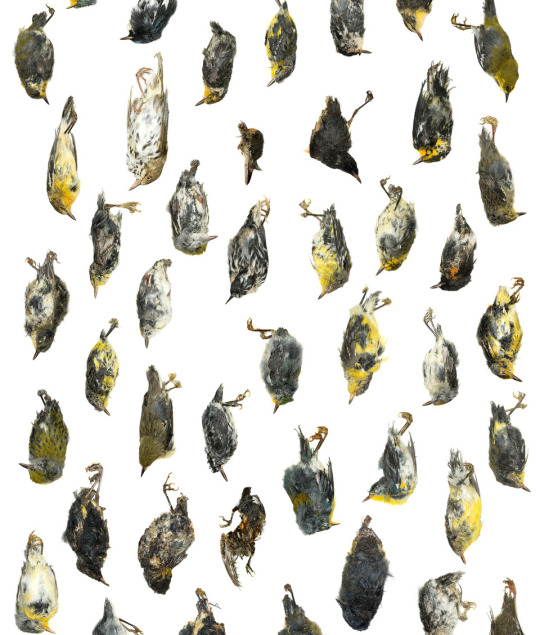

Installation view, The Nature of Nature: The Photographs of Thaddeus Holownia, 1976-2016. At the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia. Rear wall: Icarus, Falling of Birds (2016). Chromogenic print, 487.7 x 76.2 cm.

Not long after Canadian photographer Thaddeus Holownia left Toronto in the mid-70’s, decamping to Sackville, New Brunswick, he became besotted with a bird biologist working at Mount Allison University’s biology department. Her name was Gay Hansen, and Holownia had heard somewhere that she practiced taxidermy, preparing specimens which she would then use in her classroom instruction. Thus he was able to hatch a plan to meet her. When, finally, he found a struck bird on the side of the road, he gathered it up, and knocking on her office door, presented Hansen with the dead blue jay. Four decades later, the couple has fledged four children, and have operated a veritable ark for uncountable legions of dogs, cats, horses, ponies, and birds. Possibly also a weasel. There are, perhaps, more conventional creation myths, but few so prophetic or prescient for Holownia’s concurrent life in art. An incisive gathering of that life’s work has just finished its run at Halifax’s Art Gallery of Nova Scotia with the exhibition The Nature of Nature: The Photographs of Thaddeus Holownia, 1976-2016, curated by David Diviney and Sarah Fillmore.

Aside from being a busy artist, Holownia has taught photography at Mount Allison since 1977, and has been active as a letterpress printer, collaborator, and publisher with his imprint Anchorage Press. For me as for many others, Holownia has been an important teacher and mentor. Flying to Halifax in the dead of winter for the opening of his retrospective was a chance to see both old work that I was intimately familiar with, and work that was unknown to me. It was a joyful and haunting reunion and introduction.

Holownia has long stated that, in the most general sense, his photographic project is an examination of human intervention in the landscape. His massive catalogue of images attests to this; for forty years, the unrelenting scrutiny of his view cameras has fettered out the saw-toothed interface between the natural world and “us”. Four projects well-represented in the exhibition portray this relationship clearly: Rockland Bridge is a 20-year chronicle of a once-proud covered bridge being slowly ground to bits by the Memramcook River. Eventually, all trace of it gone. Holownia’s early magnum opus Dykelands is the close observation of an apparently natural landscape and the spidery, ephemeral human presence there. In fact, this natural landscape was manufactured by the Acadians, one spadeful of red earth at a time, “reclaiming” the once massive Tantramar Marsh from the sea. Three centuries of noisy colonial history have focused attention away from the fact that the dyking of the Tantramar was essentially a slow, massive, agrarian-made ecological disaster. Anatomy of a Pipeline follows the installation of the Sable Gas Pipeline from where it makes landfall in Nova Scotia, traversing New Brunswick, and eventually snaking into Maine. Even the series Jolicure Pond, in which Holownia photographed his own backyard (and the eponymous pond) is a meditation on the metamorphic power of light delivered up by a machine-dug pond.

There is however, something deeper, something more subtle and menacing at play in Holownia’s work — an almost unidentifiable dynamic between the human and the non-human — than is done justice by the term “intervention.” Yes, there are plenty of examples in the gallery of our incursions into the natural world, but what about the natural world’s incursions into us? The relationship is not one-sided. We are making a terrible mess of this planet, but the truth of the matter is that planet Earth will continue without us, and in fact it will thrive, again, without us. So the slow dance that plays out across the frames of these photographs depicts our planet as a formidable and tolerant sparring partner; eventually, it is us that we will tire (or toxify) into oblivion.

Boxing serves as a useful metaphor for understanding Holownia’s work. The physical dichotomy of push-pull and hold-fight is echoed by the seeming contradiction of mirror-window. With his 1978 exhibition and book of the same name, the American curator, writer, and photographer John Szarkowski famously divided photography into the discrete categories of Mirrors and Windows. Seeking an aesthetic, procedural, and conceptual device with which to evaluate American photography of the 1960’s and ‘70’s, he proposed that a photograph is either a window into the external, wider world, or a mirror reflecting the inner world of the artist — it is either a realist or a romantic document. He suggests not that these are absolutes, but that these are two poles between which there is a spectrum. As his essay sharpens towards its conclusion, Szarkowski becomes more and more ambivalent about his dichotomy, convincing himself that perhaps good photographs most often live in the grey zones of that spectrum.

Blind, Near Stewiacke, NS, 2009. Pigment print, 30.4 x 86.1 cm.

Holownia’s work is a superimposition, a double exposure of a window and a mirror. One of the more recent works in the exhibition, Blind, Near Stewiacke, NS, 2009, shows the tattered remnants of a deer blind surrounded by the tattered remnants of a clear-cut forest. The image is pure disarray, save a still-square aperture cut into the wall of the blind: Holownia’s window and mirror. A final human vestige, the blind is made of wood like the surrounding trees. While the wood of the razed forest will now commence to growing, the wood of the blind will commence to decomposing; our artifact will become the nutrients used to build a new world without us. As the audience, we are left to ponder the consequences of the double meaning of the work’s title.

Anatomy Lesson: Moose (2006). 100 toned, silver gelatin prints, 36 x 28 cm each.

The same troublesome superimposition can be found in the behemoth installation Anatomy Lesson: Moose (2006), which consists of 100 black-and-white photographs of individual bones of a moose skeleton, arrayed five high by twenty wide, in thin black frames hung flush together. The bones are photographed positioned on black cloth, centred in the frame, and with consistent sobriety, as museum pieces might be. The remains are coldly catalogued, and yet some combination of the lighting of the objects, the subtleties of tone (one imagines that the bleached bones on the black backdrop would look nearly identical as colour photographs), and the play of scale creates both ambiguity and uncanniness. Are these ancient tools? weapons? One bone is so big (must be a part of the leg) that it playfully spans two frames, adding a jilting continuity (or would it be discontinuity?) that animates what might otherwise be a lifeless grid. It is an iconoclast in a field of icons.

Anatomy Lesson’s 100 images are framed behind non-reflective glass. Looming amorphous reflections however, cannot be entirely eliminated. The black mass on the wall evokes Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial in the way it mirrors its spectators. While Lin’s wall is polished, and one’s clear reflection is superimposed on the names of the dead, Holownia’s wall is murky, and the shadow-form reflections of its human audience are punctuated and perforated by the bones of another animal. The ramifications of this disconcerting superimposition are humility, reflection on mortality, and likely chagrin — the moose’s scapula appears to have been ripped through by a poacher’s bullet. This inter-species substitution, in addition to being an apposite through-line of Holownia’s retrospective, may well be the real lesson of the work’s title.

Detail: Anatomy Lesson: Moose (2006). 100 Toned silver gelatin prints, 36 x 28 cm each.

Icarus, Falling of Birds (2016) is the retrospective’s newest — and, for Holownia, his most un-subtle — work to date, providing a dramatic and condemning full stop to the exhibition. On the foggy night of September 13th, 2013, the Canaport Liquefied Natural Gas plant in Saint John, New Brunswick, belched a massive gas flare that, like a small sun, lit up the night. The timing of this flare broke strict laws about when such flares are permitted to take place. Thousands of migrating songbirds flew towards, and into, this flare and they got incinerated for their effort. 7,500 birds were picked up dead from the ground, but more likely a total of 10,000 birds were killed, their little bodies running the gamut from the black-and-crispy to those that look peacefully asleep. Holownia and his frequent collaborator writer/poet Harry Thurston painstakingly de-tagged and photographed 400 of these birds which have been, ironically, frozen, at the New Brunswick Museum. Two hundred birds, representing all 26 species that were among the dead, occupy a massive, vertical photo-montage that descends the height of a two-story wall. Most of the exhibition’s 151 works are painstakingly framed to museum standards. Icarus, Falling of Birds gets no such treatment. The 200 bird corpses that were photographically documented occupy a ribbon of image that is completely unadorned and unpreserved. This composite photograph, a sad and angry testament, uses the gallery’s architecture as its frame, and scroll-like, unfurls downward as did the birds. Ironically, when one approaches these falling birds, one is forced to look up, creating a powerful and disconcerting dissonance.

Detail: Icarus, Falling of Birds (2016). Chromogenic print, 487.7 x 76.2 cm.

The complicating wrinkle that Holownia’s work presents is the fact that we are both of and apart from the natural world. The threshold between that ‘and’ is tragedy, comedy, absurdity, irony, or a combination of them all. One of my favourite works in the show is one you might walk by if you’re not looking closely. Hwy 102, Exit 11, NS, 1995 was made at Mastodon Ridge, in Stewiacke, Nova Scotia. In it, workers, an SUV, a pickup truck, and a small bulldozer are scattered across a muddy field and are being bellowed at by a life-sized replica mastodon. This dubious field happens to fall where the 45th parallel crosses, handily, the Trans-Canada Highway. What we are privy to is the installation of a model mastodon for the purposes of serving as a tourist trap. The ancient bones of the original pachyderm were found fifteen kilometres away in a gypsum quarry. “Mastodon Ridge,” the road-side attraction, now boasts a gift shop, a gas station, a KFC, a Taco Bell, a Tim Horton’s, and, inexplicably, cannons. Families can play in the sandbox, the playground, or the mini-putt. The elements of the image are pure Holownian grist, which is to say the residue that is formed at the intersection of two axes — the human/natural and reverent/irreverent. The mastodon has been immortalized mid-gape-mouthed bawl — bawling at a predator? a rival? It seems more likely that it is, clairvoyantly, ushering forth a primal scream towards its future as a circus elephant.

Crow Scare, ME, 2015. Pigment print. 27.0 x 71.1 cm.

Crow Scare, ME, 2015 is a condemnation. I think so, anyway, though it’s difficult to say. It resides between the bucolic and the horrific, the beautiful and the monstrous. In subject and in mood, the image is haunted by Alex Colville’s spirit. The photograph’s wide frame is sectioned up into field, grass, trees, sky. The image’s subtle grey bands are jarringly punctured by the outlandish black of a dead crow, one foot delicately tied to a delicate stick, cantilevering out of the field — a morbid sundial. But in this eerily ambient light, it casts no shadow, as if time were obliterated. The angles of the crow’s body, tail, wings, and beak are both at perfect odds and in perfect harmony with that of the stick, and are set off by the plumb line of the string. Whether this bird was purpose-killed or was found we don’t know, but we hope that the ideal sculptural presentation of its corpse is an accident, for as much as it’s intended to repel other crows, it seduces this viewer, unsettlingly. And so with this crow, as with the blue jay, Holownia has found his dead bird and redirected it with precision.

Retrospective exhibitions can be bulky, lamentatory affairs — a collection of greatest hits, or the bookend of an artist’s career. The Nature of Nature is neither. Holownia has produced a catalogue of work that is expansive and diverse enough that the curators were able to isolate one clear and emphatic stream within it; the exhibit has a propulsive thesis that both cautions and reassures. The Nature of Nature catches an artist mid-stride. Though it wraps up with the emphatic thud of Icarus, the lingering buzz in the gallery is one borne of both hope and despair, like the positive and negative terminals a battery needs to produce a current. One has the sense that the always indefatigable Holownia is just ramping up to something. And so I am led back to the title: The Nature of Nature. Thinking hard about where we fit into this notion, I am struck by the idea that if indeed we are part of nature — aberrations or not — then like nature, we will simply keep going.

John Haney is a photographer/visual artist and sometimes writer who lives in Hamilton in a house populated by animals, including a dog and two boys under five. An upcoming adventure will be a residency at Thunder & Lightning Gallery and Art Projects in where else? Sackville, New Brunswick. As a founding member of the band/art collective SHIT PYRE, he is continuing to explore ritual, improvisation, theatrics, and pyrotechnics.

#criticalsuperbeast#hamont#artcriticism#johnhaney#thaddeusholownia#photography#canadianart#artgalleryofnovascotia#landcape#newbrunswick#sackville#nature#wildlife#retrospective

0 notes

Text

Identity

208 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mediate

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lift

315 notes

·

View notes

Text

Solar

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vicinity

43 notes

·

View notes