#johnhaney

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Vanquish

by John Haney

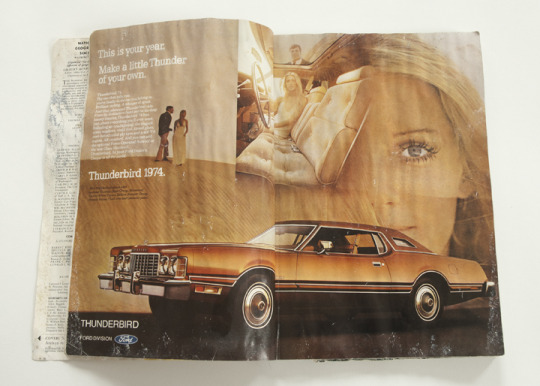

National Geographic; December 1973. Photo Courtesy of the artist.

In a cabin in Northern Ontario, I discovered a sole National Geographic magazine. It was the December, 1973 issue. The cover story is about the “Lost Empire of the Incas.” Six pages in is an ad for the 1974 Ford Thunderbird, showing an immense copper-coloured coupe, and an attractive woman. Flip the page and there’s an eight-page insert sponsored by Exxon Oil. It tells us that “Every day the average man, woman and child in the U.S. uses nearly four gallons of oil, 300 cubic feet of natural gas, 15 pounds of coal . . . eight times as much as the world average.” It then spells out countless ways that American oil companies are scrounging for new oil and gas fields, and new techniques to increase production. Listed also, are ways that Americans can hope to cut down their dependency on cheap oil. All of this of course, to alleviate American panic a month and a half after the Saudi Oil Embargo, the use of the so-called “Oil Weapon.”

Get to the end of the cover article about the Incans’ demise. It’s not too much fun to read so much about sacrifice and slaughter, and the Spanish Conquistadors’ insatiable appetite for Incan gold. “Do you eat gold?” the Incans asked them. The final two-page spread has two photographs: one is of two ceremonial Incan gloves made of pure beaten gold. The other photograph is of a field of bleached skulls and bones, under a full moon in a twilight sky: the remains of an ancient Incan cemetery, which apparently, still gets picked over for gold remnants.

Pizarro promised Atahuallpa, the Incan ruler, that he would be released, in exchange for booty: a 17’ x 22’ room, filled as high as the king could reach, once with gold, and twice with silver. The treasures were collected then melted down in nine forges over the course of several months, reducing the artifacts to lumps of metal, which were shipped to Spain. As thanks, Pizarro had Atahuallpa garroted instead of released. As for the treasure, the writer notes, “Not a relic remains of that fabulous roomful . . . It’s anyone’s guess whether it eventually became a bag of barnacled ingots calcified into a Caribbean reef, a bar in a Swiss bank, or the protective sheath of a space probe.”

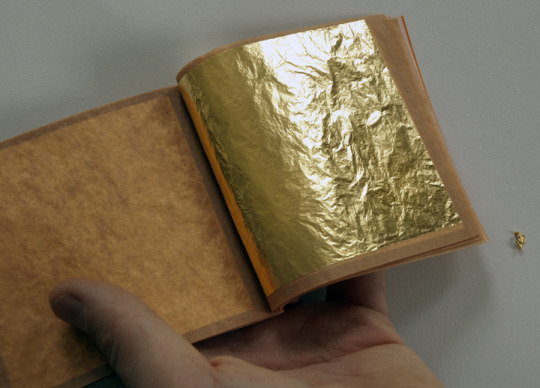

Booty. Photo Courtesy of the artist.

The above is an excerpt from a process piece by Hamilton-based artist John Haney, who is currently working on a sculptural work which uses a 1973 Cadillac Eldorado coupe as its foundation. For that car, he procured a vanity license plate that reads THNATOS, which refers to Thanatos, both the boatman-like Greek god of non-violent death, and the psychoanalytic term that describes the tendency towards self-destruction, or "death-drive". The vehicle's entire painted surface will be gilded with 24 karat gold leaf, and will reference pan-cultural, pan-theistic mythologies. Broadly speaking, this work reflects global events and popular culture of 1973, using that year as a device to speak of our history of folly, going back thousands of years, and pointing forward to our present and likewise our future.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

For the woman who taught me to crack an egg at 25, who always thought my Mohawk was cool, and makes the best cake in the world. I've spent the last few years under her careful instruction learning how to bake this and hearing her life stories. These have been some of the most important times of my life. She turns 90 this summer, so I thought this would be most fitting present for a life fully lived. And thanks to the always rad @johnhaney for turning my sketches into reality. #tattoo #chocolatecake #traditionaltattoo #vatoscript #tastybiz (at UpRise Tattoos)

0 notes

Quote

Favorite tweets: Music requested for company picnic. @jamesdempsey is the only obvious choice, of course! https://t.co/wtOQDEaJ0p— John Haney (@johnhaney) August 30, 2017

http://twitter.com/johnhaney

0 notes

Photo

PRIVATE COMMUTE

Erin Brubacher and John Haney

May 1st-June 2

Opening Reception May 4, 7-10 pm

Featured Exhibition in the Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival

http://scotiabankcontactphoto.com/featured-exhibitions/771

For over ten years Erin Brubacher and John Haney have observed one another’s practices, each regarding the other’s creative pursuits with curiosity, occasional skepticism and continuous admiration. Through the joining of their practices in Private Commute, they cross the borders of process and artifact that have defined their work up tothis point.

Haney’s photography is formal and documentary in nature, most often concerning itself with notions of place. Brubacher has developed an invitational practice through photography and performance; creating situations through which to interact with participants/audience is key to her processes, which determine the results viewed or experienced by secondary audiences.

For this project, Brubacher and Haney give 20 people, encountered on their daily commutes in Toronto and Hamilton, the same two photographic diptychs, and ask that the recipients display them in their homes. A month later, the artists return to document these diptychs in situ, in the contexts in which their new owners have displayed them, through a series of large-format photographs.

The diptychs become windows on the private spaces of the people encountered in the artists’ day-to-day public journeys — and the resulting installation, on display at Communication Gallery, plays with our conventional notions of exhibition and curation, bringing people’s private installations into this public gallery space.

www.erinbrubacher.ca

www.johnhaney.ca

0 notes

Text

True Blue: “A Sublime Vernacular: The Landscape Paintings of Levine Flexhaug”

January 28th to March 12th, 2017, Rodman Hall Art Centre, St. Catharines, Ontario. Curated by Nancy Tousley and Peter White.

By John Haney

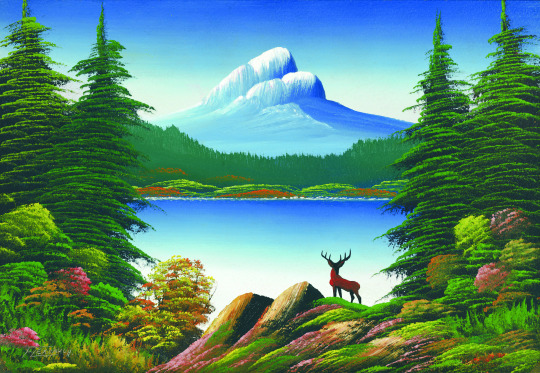

Levine Flexhaug, Mountain Lake with Deer. Image courtesy of Rodman Hall Art Centre.

The term outsider art has always rubbed me the wrong way. It refers to art made by people who do not have training in art-making or in art history. An “outsider” artist does not exist within the established boundaries of the art world. Depending on one’s perspective, the term is either pejorative or liberating. While I don’t entirely disagree with its usage, the term casts a wide net, acting as a sort of containment device for undesirables — artists whom American writer and illustrator Sarah Boxer lumps together as “visionary, schizophrenic, primitive, psychotic, obsessive, compulsive, untutored, vernacular, self-taught, naive, brut, rough, raw,” as if all non-outsider artists were normal. However, by my rudimentary arithmetic, the corollary of outsider is insider, implying a rarified world made both by and for those who occupy the centre and may freely designate labels. The phrase, for me, elicits a Groucho Marx-like distaste: the sort of distaste that one might harbour for any club that might have one as a member.

And then there is the eccentric example of the artist Levine Flexhaug (who could be described by the majority of Boxer’s designations), the subject of an exhibition now on display at Rodman Hall in St. Catharines. Flexhaug was a self-taught painter (though he showed “an aptitude for art” in grade school) born near the dubiously-named town of Climax, Saskatchewan, during the final year of the First World War. An “itinerant painter,” he travelled around the Canadian west during the Dust Bowl era of the Great Depression in a massive station wagon, schlepping his painting gear. Flexhaug painted — over, and over, and over again — seemingly endless variations on one theme, indeed image: an idealized vision of a Canadian Rocky Mountain scene. This was a world populated solely by animals, save the occasional canoeist. A quaint log cabin graces many of the paintings but there is no Goldilocks, rather a family of bears who seem more like the cabin’s residents than its marauders.

Full disclosure: on January 11th, I was called into Rodman Hall to spend the next two and a half weeks working as a gallery technician, labouring with a team to install an exhibition consisting of no less than 465 of Flexhaug’s paintings. We immersed ourselves in days spent unpacking the hundreds of paintings from their crates for the usual condition-reporting: making note of the condition of the works both to ensure that they have travelled safely, and to establish a baseline status should any damage occur during the run of the exhibition. But this was condition reporting like no other: the paintings were framed all higgledy-piggledy, from the minimal to the absurd, contemporary to kitsch. Many paintings had holes bored straight through them, stigmata where nails secured them above fireplaces, dining room tables, perhaps even legion dartboards. The murals that came from taverns and pubs were mystified with nicotine sfumato. Peter White, co-curator of the exhibition, remarked that the big ones even smelled of burnt tobacco. One frame was stained with blood.

Another crate: 50 more paintings. Another crate: 80 more paintings! On and on it went. I developed a five-stage response to Levine Flexhaug’s works. The first day I sneered at them; their hokeyness made my skin crawl. The second day I liked them, but I was suspicious. The third day I loved them, though I dared not say it out loud. The fourth day I declared (out loud) that I loved them, but in truth I was numb. The fifth day, objectivity began returning to me slowly, though when I closed my eyes, seared on my retina were (are) his innumerable repeating motifs: mountains, trees, lake, stags, moose, bears, birds, cabin, canoe, moon (always full, never fractioned). Then these animals began to show up everywhere: one moose on a QEW Ontario Tourism sign; another moose (its plastic head) covering the trailer hitch-ball on an old Lincoln Continental lumbering along Burlington Street; a silhouetted bear on a beer can. I’d been Flexhauged! Suddenly the totems of his de-peopled world became grafted on to my surroundings — the Golden Horseshoe, this most desecrated of Canadian landscapes.

Flexhaug’s work was a salve not so much for a desecrated landscape, but for desecrated souls. He whipped these paintings off, selling them at modest prices primarily to Prairie folk who were depressed by the Depression, and perhaps also by their own landscape’s relative topographic inadequacies. Flexhaug’s paintings are examples of undeniably democratic art, the kind you see piled against a wall at the Sally Ann. Indeed, many works still have thrift store price tags on their sides or backs: $2.99, $10.00, one auction-buster weighing in at $50. His was a simple, if heroic world; his Rückenfigur was not a brooding German existentialist, but a deer. Or a moose. In the depths of the mid-century Prairies, these little blocks of saturated colour must have been escape portals that ran at odds with the brown and the white and the horizontal. One is tempted to snatch one off the wall (would it be missed?) and sneak it into the AGO’s concurrent blockbuster show Mystical Landscapes. Would it be conspicuous, or would it hide in plain sight?

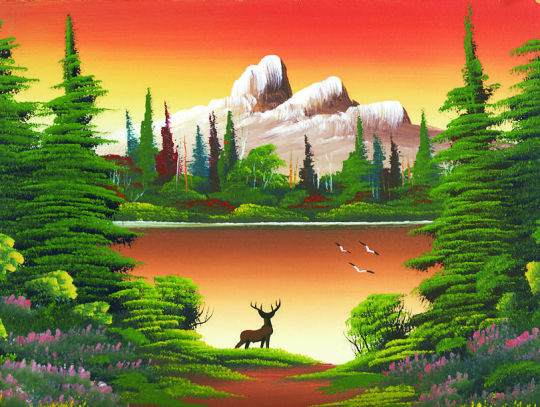

Levine Flexhaug, Mountain Lake with Deer and Three Birds. Image courtesy of Rodman Hall Art Centre.

Flexhaug has been dead for over forty years, and yet his seemingly endless typology of chimerical Canadian mountain landscapes has done its work on me. There is a quotation which I cannot find, that I learned of from my wife, who was paraphrasing her mother, who was paraphrasing possibly a New Yorker article from sometime within the last two decades: that if a man draws a line, it’s probably not that interesting. If he’s drawing the same line fifty years later, you’d better take notice. Flexhaug found a formula and cleaved to it, making paintings that abstain from the weight of history; they are flat fantasies that begin to make demands of you. They are like those people who are quiet and smiley, and thus make people like me blather confessionally in order to fill an awkward, if amicable silence. Flexhaug’s paintings changed little over the decades, save the date he inscribed on them; one has to look at these dates and wonder if the images provide any evidence of historical attestation: do those painted in 1939 show a preoccupation with the first shots fired in a new war? Do the peach-and-chartreuse skies of a 1945 painting express the existential burden of Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Flexhaug was a commercial artist. He was an entrepreneur. Was he a scrappy hustler or a quiet, reflective soul? Did he find solace in painting these innumerable boards, or was it tedious work? Was he sincere, or did he wield his brush with a smirk? Faced by walls crowded with paintings, one contemplates these binaries. The pictorial subject becomes immaterial; the paintings deliquesce into a watery staccato barely contained by the key of “True Blue” paint applied to two of Rodman’s smaller walls. The curator’s function in this exhibition becomes less to order a selection of work than to take on the role of an installation artist, painting the walls with paintings. The works’ demands are not so much art-critical as they are anthropological.

After being trapped in the same room with Levine Flexhaug for nearly three weeks, I began to take the same refuge in his never-cloudy vistas as their first delighted owners might have. These are paintings whose jobs were, in essence, to bring relief, to give people a sense of escape or reassurance during trying or just plain regular times. Is a painting’s role — or art’s role — to be a window or a mirror? Does one’s gaze penetrate these simple, silly vistas into an imagined space, or does the eye stop on the surface of the paint? When I describe this work to friends, their common question is: were these paintings based on an actual view? I don’t know, and I don’t particularly care. As it turned out, the duration of time it took to hang this show was coincident with the dark, foggy, un-seasonably warm, drab doldrums of January. Evening commutes back to Hamilton brought the ever-worsening news of the Trump inauguration and new world order. Oh, how I longed to be back in that warmly-lit gallery with its hundreds upon hundreds of perfect, untroubled landscapes. Better yet, I could disappear from the city entirely and find the open door of one of those red cabins and, like many others who feel the same way these days, take up a new life as an outsider.

John Haney is an artist who lives in Hamilton.

#criticalsuperbeast#artcriticism#hamont#levineflexhaug#johnhaney#rodmanhall#stcatharines#painting#landscapes#artbrut#outsiderart

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Critical Superbeast 2016 - 2018

Critical Superbeast was an online critical writing forum based in Hamilton, Ontario, from 2016-2018. Through (mostly) weekly posts, various writers covered the works of artists from the local scene and beyond, including exhibition reviews, thoughts on visual culture topics, studio visit musings and more. It was founded by a group of arts workers and artists in Hamilton.

We felt the need for more critical dialogue in this city, which is increasingly enlivened by working artists. An editorial board was struck not to vet content but rather to coordinate the logistics of a rotating group of writers and editors, handle our call for submissions and organize the content for the blog posts. Facebook posts reached anywhere from 150 to 1000 readers. We’re proud of what was accomplished: the attention brought to the art scene and the hard work of artists (who often toil away without much public feedback), plus the encouraging occasion for writers to conceptualize and deliver a piece to be published.

The group has now wound down due to various other commitments on the part of the organizers. Rest assured that the commitments are all still heavily related to art creation and/or criticism. But we are all proud of what was accomplished with Critical Superbeast:

Forty-four essays written, covering the works of emerging and established Hamilton artists, plus a few living further afield.

Writers were all volunteers, and most of them played an administrative role at some point as well. The list includes: Jen Anisef, Gabriel Baribeau, Melissa Bennett, Aimee Burnett, Tara Bursey, Greg Davies, Anthony Easton, Tor Lukasik-Foss, Jeremy Freiburger, John Haney, Daniel Hutchinson, Amanda Jernigan, Emma Lansdowne, Ingrid Mayrhofer, Sally McKay, Sylvia Nickerson, Caitlin Sutherland, Karen Thiessen, Svava Juliusson, Alana Traficante, and Stephanie Vegh, (Apologies for any omissions).

Artists covered in the writings include: Jennifer Angus, Heather Benning, Katinka Bock, Danny Custodio, Robert Davidson, Erika DeFreitas, Levine Flexhaug, Andrea Flockhart, V. Jane Gordon, Laine Groeneweg, John Haney, Joseph Hartman, Catherine Heard, Thaddeus Holownia, Michele Karch-Ackerman, Sean Kenney, Suzy Lake, Elad Lassry, Steven Laurie, Trisha Leigh Lavoie, Claudia Manley and Liss Platt, Nancy Anne McPhee, Martin Messier, Sylvia Nickerson, Hélio Oiticica, Vicky Sabourin, Giancarlo Scaglia, Judith Scott, WhiteFeather, Benita Whyte, and Marlene Yuen; plus more in various group exhibitions such as Art Spin’s first venture in Hamilton.

Rest in peace, ‘Beast.

[image credit: Andrew McPhail, Sorry, performance and text piece with rubber gloves, 2009-ongoing. Installation view at Artspace Peterborough, 2011. Courtesy of the artist.]

#jenanisef#gabrielbaribeau#melissabennett#aimeeburnett#tarabursey#gregdavies#anthonyeaston#TorLukasikFoss#jeremyfreiburger#johnhaney#danielhutchinson#amandajernigan#EmmaLansdowne#IngridMayrhofer#sallymckay#sylvianickerson#caitlinsutherland#karentheissen#SvavaJuliusson#AlanaTraficante#stephanievegh#hamilton#art#criticism

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Elephant in the Room

The Nature of Nature: The Photographs of Thaddeus Holownia, 1976-2016. At the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, February 4 to May 28, 2017. Curated by David Diviney and Sarah Fillmore.

By John Haney

Installation view, The Nature of Nature: The Photographs of Thaddeus Holownia, 1976-2016. At the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia. Rear wall: Icarus, Falling of Birds (2016). Chromogenic print, 487.7 x 76.2 cm.

Not long after Canadian photographer Thaddeus Holownia left Toronto in the mid-70’s, decamping to Sackville, New Brunswick, he became besotted with a bird biologist working at Mount Allison University’s biology department. Her name was Gay Hansen, and Holownia had heard somewhere that she practiced taxidermy, preparing specimens which she would then use in her classroom instruction. Thus he was able to hatch a plan to meet her. When, finally, he found a struck bird on the side of the road, he gathered it up, and knocking on her office door, presented Hansen with the dead blue jay. Four decades later, the couple has fledged four children, and have operated a veritable ark for uncountable legions of dogs, cats, horses, ponies, and birds. Possibly also a weasel. There are, perhaps, more conventional creation myths, but few so prophetic or prescient for Holownia’s concurrent life in art. An incisive gathering of that life’s work has just finished its run at Halifax’s Art Gallery of Nova Scotia with the exhibition The Nature of Nature: The Photographs of Thaddeus Holownia, 1976-2016, curated by David Diviney and Sarah Fillmore.

Aside from being a busy artist, Holownia has taught photography at Mount Allison since 1977, and has been active as a letterpress printer, collaborator, and publisher with his imprint Anchorage Press. For me as for many others, Holownia has been an important teacher and mentor. Flying to Halifax in the dead of winter for the opening of his retrospective was a chance to see both old work that I was intimately familiar with, and work that was unknown to me. It was a joyful and haunting reunion and introduction.

Holownia has long stated that, in the most general sense, his photographic project is an examination of human intervention in the landscape. His massive catalogue of images attests to this; for forty years, the unrelenting scrutiny of his view cameras has fettered out the saw-toothed interface between the natural world and “us”. Four projects well-represented in the exhibition portray this relationship clearly: Rockland Bridge is a 20-year chronicle of a once-proud covered bridge being slowly ground to bits by the Memramcook River. Eventually, all trace of it gone. Holownia’s early magnum opus Dykelands is the close observation of an apparently natural landscape and the spidery, ephemeral human presence there. In fact, this natural landscape was manufactured by the Acadians, one spadeful of red earth at a time, “reclaiming” the once massive Tantramar Marsh from the sea. Three centuries of noisy colonial history have focused attention away from the fact that the dyking of the Tantramar was essentially a slow, massive, agrarian-made ecological disaster. Anatomy of a Pipeline follows the installation of the Sable Gas Pipeline from where it makes landfall in Nova Scotia, traversing New Brunswick, and eventually snaking into Maine. Even the series Jolicure Pond, in which Holownia photographed his own backyard (and the eponymous pond) is a meditation on the metamorphic power of light delivered up by a machine-dug pond.

There is however, something deeper, something more subtle and menacing at play in Holownia’s work — an almost unidentifiable dynamic between the human and the non-human — than is done justice by the term “intervention.” Yes, there are plenty of examples in the gallery of our incursions into the natural world, but what about the natural world’s incursions into us? The relationship is not one-sided. We are making a terrible mess of this planet, but the truth of the matter is that planet Earth will continue without us, and in fact it will thrive, again, without us. So the slow dance that plays out across the frames of these photographs depicts our planet as a formidable and tolerant sparring partner; eventually, it is us that we will tire (or toxify) into oblivion.

Boxing serves as a useful metaphor for understanding Holownia’s work. The physical dichotomy of push-pull and hold-fight is echoed by the seeming contradiction of mirror-window. With his 1978 exhibition and book of the same name, the American curator, writer, and photographer John Szarkowski famously divided photography into the discrete categories of Mirrors and Windows. Seeking an aesthetic, procedural, and conceptual device with which to evaluate American photography of the 1960’s and ‘70’s, he proposed that a photograph is either a window into the external, wider world, or a mirror reflecting the inner world of the artist — it is either a realist or a romantic document. He suggests not that these are absolutes, but that these are two poles between which there is a spectrum. As his essay sharpens towards its conclusion, Szarkowski becomes more and more ambivalent about his dichotomy, convincing himself that perhaps good photographs most often live in the grey zones of that spectrum.

Blind, Near Stewiacke, NS, 2009. Pigment print, 30.4 x 86.1 cm.

Holownia’s work is a superimposition, a double exposure of a window and a mirror. One of the more recent works in the exhibition, Blind, Near Stewiacke, NS, 2009, shows the tattered remnants of a deer blind surrounded by the tattered remnants of a clear-cut forest. The image is pure disarray, save a still-square aperture cut into the wall of the blind: Holownia’s window and mirror. A final human vestige, the blind is made of wood like the surrounding trees. While the wood of the razed forest will now commence to growing, the wood of the blind will commence to decomposing; our artifact will become the nutrients used to build a new world without us. As the audience, we are left to ponder the consequences of the double meaning of the work’s title.

Anatomy Lesson: Moose (2006). 100 toned, silver gelatin prints, 36 x 28 cm each.

The same troublesome superimposition can be found in the behemoth installation Anatomy Lesson: Moose (2006), which consists of 100 black-and-white photographs of individual bones of a moose skeleton, arrayed five high by twenty wide, in thin black frames hung flush together. The bones are photographed positioned on black cloth, centred in the frame, and with consistent sobriety, as museum pieces might be. The remains are coldly catalogued, and yet some combination of the lighting of the objects, the subtleties of tone (one imagines that the bleached bones on the black backdrop would look nearly identical as colour photographs), and the play of scale creates both ambiguity and uncanniness. Are these ancient tools? weapons? One bone is so big (must be a part of the leg) that it playfully spans two frames, adding a jilting continuity (or would it be discontinuity?) that animates what might otherwise be a lifeless grid. It is an iconoclast in a field of icons.

Anatomy Lesson’s 100 images are framed behind non-reflective glass. Looming amorphous reflections however, cannot be entirely eliminated. The black mass on the wall evokes Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial in the way it mirrors its spectators. While Lin’s wall is polished, and one’s clear reflection is superimposed on the names of the dead, Holownia’s wall is murky, and the shadow-form reflections of its human audience are punctuated and perforated by the bones of another animal. The ramifications of this disconcerting superimposition are humility, reflection on mortality, and likely chagrin — the moose’s scapula appears to have been ripped through by a poacher’s bullet. This inter-species substitution, in addition to being an apposite through-line of Holownia’s retrospective, may well be the real lesson of the work’s title.

Detail: Anatomy Lesson: Moose (2006). 100 Toned silver gelatin prints, 36 x 28 cm each.

Icarus, Falling of Birds (2016) is the retrospective’s newest — and, for Holownia, his most un-subtle — work to date, providing a dramatic and condemning full stop to the exhibition. On the foggy night of September 13th, 2013, the Canaport Liquefied Natural Gas plant in Saint John, New Brunswick, belched a massive gas flare that, like a small sun, lit up the night. The timing of this flare broke strict laws about when such flares are permitted to take place. Thousands of migrating songbirds flew towards, and into, this flare and they got incinerated for their effort. 7,500 birds were picked up dead from the ground, but more likely a total of 10,000 birds were killed, their little bodies running the gamut from the black-and-crispy to those that look peacefully asleep. Holownia and his frequent collaborator writer/poet Harry Thurston painstakingly de-tagged and photographed 400 of these birds which have been, ironically, frozen, at the New Brunswick Museum. Two hundred birds, representing all 26 species that were among the dead, occupy a massive, vertical photo-montage that descends the height of a two-story wall. Most of the exhibition’s 151 works are painstakingly framed to museum standards. Icarus, Falling of Birds gets no such treatment. The 200 bird corpses that were photographically documented occupy a ribbon of image that is completely unadorned and unpreserved. This composite photograph, a sad and angry testament, uses the gallery’s architecture as its frame, and scroll-like, unfurls downward as did the birds. Ironically, when one approaches these falling birds, one is forced to look up, creating a powerful and disconcerting dissonance.

Detail: Icarus, Falling of Birds (2016). Chromogenic print, 487.7 x 76.2 cm.

The complicating wrinkle that Holownia’s work presents is the fact that we are both of and apart from the natural world. The threshold between that ‘and’ is tragedy, comedy, absurdity, irony, or a combination of them all. One of my favourite works in the show is one you might walk by if you’re not looking closely. Hwy 102, Exit 11, NS, 1995 was made at Mastodon Ridge, in Stewiacke, Nova Scotia. In it, workers, an SUV, a pickup truck, and a small bulldozer are scattered across a muddy field and are being bellowed at by a life-sized replica mastodon. This dubious field happens to fall where the 45th parallel crosses, handily, the Trans-Canada Highway. What we are privy to is the installation of a model mastodon for the purposes of serving as a tourist trap. The ancient bones of the original pachyderm were found fifteen kilometres away in a gypsum quarry. “Mastodon Ridge,” the road-side attraction, now boasts a gift shop, a gas station, a KFC, a Taco Bell, a Tim Horton’s, and, inexplicably, cannons. Families can play in the sandbox, the playground, or the mini-putt. The elements of the image are pure Holownian grist, which is to say the residue that is formed at the intersection of two axes — the human/natural and reverent/irreverent. The mastodon has been immortalized mid-gape-mouthed bawl — bawling at a predator? a rival? It seems more likely that it is, clairvoyantly, ushering forth a primal scream towards its future as a circus elephant.

Crow Scare, ME, 2015. Pigment print. 27.0 x 71.1 cm.

Crow Scare, ME, 2015 is a condemnation. I think so, anyway, though it’s difficult to say. It resides between the bucolic and the horrific, the beautiful and the monstrous. In subject and in mood, the image is haunted by Alex Colville’s spirit. The photograph’s wide frame is sectioned up into field, grass, trees, sky. The image’s subtle grey bands are jarringly punctured by the outlandish black of a dead crow, one foot delicately tied to a delicate stick, cantilevering out of the field — a morbid sundial. But in this eerily ambient light, it casts no shadow, as if time were obliterated. The angles of the crow’s body, tail, wings, and beak are both at perfect odds and in perfect harmony with that of the stick, and are set off by the plumb line of the string. Whether this bird was purpose-killed or was found we don’t know, but we hope that the ideal sculptural presentation of its corpse is an accident, for as much as it’s intended to repel other crows, it seduces this viewer, unsettlingly. And so with this crow, as with the blue jay, Holownia has found his dead bird and redirected it with precision.

Retrospective exhibitions can be bulky, lamentatory affairs — a collection of greatest hits, or the bookend of an artist’s career. The Nature of Nature is neither. Holownia has produced a catalogue of work that is expansive and diverse enough that the curators were able to isolate one clear and emphatic stream within it; the exhibit has a propulsive thesis that both cautions and reassures. The Nature of Nature catches an artist mid-stride. Though it wraps up with the emphatic thud of Icarus, the lingering buzz in the gallery is one borne of both hope and despair, like the positive and negative terminals a battery needs to produce a current. One has the sense that the always indefatigable Holownia is just ramping up to something. And so I am led back to the title: The Nature of Nature. Thinking hard about where we fit into this notion, I am struck by the idea that if indeed we are part of nature — aberrations or not — then like nature, we will simply keep going.

John Haney is a photographer/visual artist and sometimes writer who lives in Hamilton in a house populated by animals, including a dog and two boys under five. An upcoming adventure will be a residency at Thunder & Lightning Gallery and Art Projects in where else? Sackville, New Brunswick. As a founding member of the band/art collective SHIT PYRE, he is continuing to explore ritual, improvisation, theatrics, and pyrotechnics.

#criticalsuperbeast#hamont#artcriticism#johnhaney#thaddeusholownia#photography#canadianart#artgalleryofnovascotia#landcape#newbrunswick#sackville#nature#wildlife#retrospective

0 notes