#joan druett

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The assistant surgeon

In addition to the actual surgeon on board a ship, there was also an assistant surgeon. This was usually a young man fresh from the Surgeons' School in Edingburgh, so please do not confuse him with a loblolly boy, who was simply an assistant from the crew. In Napoleonic times, in addition to a surgeon, it was compulsory to have three assistants on a ship of the line first rate, two on the other larger rates and one on a frigate. The Surgeon and his assistant were not required to wear a uniform until 1805.

Pay also varied according to length of service. A surgeon who had served for twenty years received 18 s. per day. A surgeon who had served for six years received 11 s. per day. Assistants had to serve three years on a ship, Navy hospital or dockyard before they were classed as full surgeons. As a result, each year of service had a different salary. The salary of the first and thus lowest grade was 4 S. per day. The other two grades received 5 S. per day. If they were not employed, surgeons and assistants received only half their salary, as was also the case for officers.

Being a Surgeon was not easy because both he and his assistant had to bring their own instruments, their medicines and other equipment were provided by the government, although there were many who made up their own medicines and passed the bills to the Admiralty.

One of the duties of an assistant was to keep a record of all cases presented to him, which was important in case of discrepancies, so that the Admiralty could compare these records with those of the surgeon and, if necessary, with the official logbooks of the captain and his lieutenants. He had to regularly check on the sick in the sickbay and show new cases to the surgeon.

He dressed the men's wounds every morning and had control of the lighter general cases. An assistant surgeon sometimes accompanied the logging and water parties, especially in places where the men were likely to stay ashore for a long time, just in case something happened. On these expeditions, it was his job to look after the men's health, keep them from drinking foul water and eating sour fruit in the heat of the day, and more.

Naval Surgeon: Life and Death at Sea in the Age of Sail, by J. Worth Estes, 1998

Rough Medicine: Surgeons at Sea in the Age of Sail, by Joan Druett · 2001

#naval history#assistant surgeon#persons of the navy#life below deck#1800s#a small overview#age of sail#surgeons at sea

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

Medicine Aboard A Whaler

I answered an ask about this some years back that was...a few paragraphs long and was before I learned that some people have the stamina and desire to read 3k+ word whaling essays from me. So if ye count yourself among them, here you go!

---

On August 21st, 1870 aboard the whaleship Sunbeam, two-time whaler Silliman Ives found himself ill with a condition “very akin to mumps, with the exception of the swelling”. It prevented him from opening his mouth, and he dreamed of the days when such an action was possible.

“I never really appreciated the luxury of a good gape before. When a fellow cannot open his mouth to any greater extent than the width of a lead pencil, gaping is not a success to say the least. And then anything in the way of a sneeze is entirely out of the question, unless you are prepared to part company with the top of your head at very short notice. A ship is a hard place to be unwell in. So long as one is in good health you can get along nicely. But if you are sick the only place where you can find sympathy is in the dictionary. And then too the remedies at hand are limited in number and obsolete in use. Your medicine chest is filled with medicines in use a hundred years ago, but which modern pharmacy has dispensed with to a very great extent. Calomel and castor oil and such like delectable doses. There is no question about it. A whale ship ought to have a surgeon, and the law should oblige such vessels to carry them. When I get into Congress I shall introduce a ���Bill” to that effect.”

As Mr. Ives noted, American whaleships went without doctors aboard even when the work was rife with injury and illness, and often quite far from access to any kind of care ashore. On British whalers it was required by law for a surgeon to be signed on for the voyage—Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was one on a voyage bound for the Arctic and apparently fell in the water so many times that the crew called him the 'Great Northern Diver'. However on American whalers—which dominated the industry—a doctor was seen by the agents as an unnecessary expense. There was the captain, the carpenter, and folks who could mend sails. Together, that makes one whole doctor! Right?

Read on, to see how they fared.

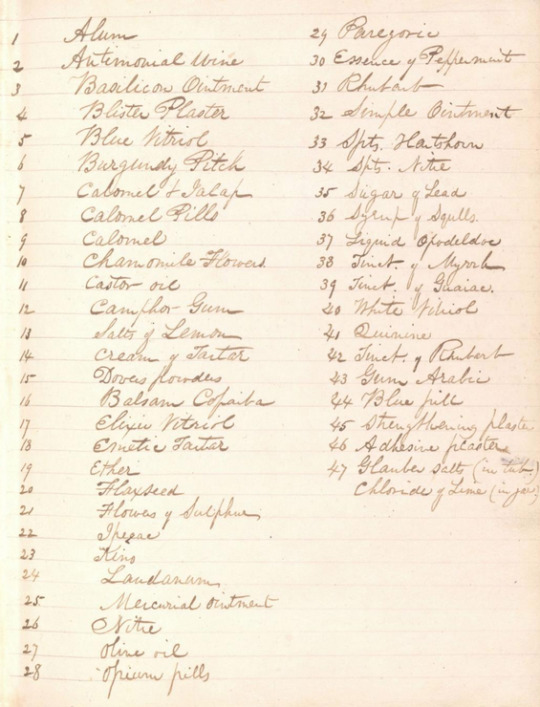

1845 whaleship medicine chest from the collection of the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

Joan Druett, in her book Rough Medicine highlighted some really fascinating things that came as a result of this, ranging from men who had scars that healed in a herringbone pattern because they were mended like canvas, to this wild tale about an amputation performed between a captain and mate at gunpoint:

“Another stirring tale told is of a Captain Coffin, who was hurt so badly in a whaling accident that it was obvious his leg would have to go. Being the master, the medic, and the patient all at once, he knew the situation was complicated, but he was more than equal to the task. He sent for his pistol and a knife, saying to his mate, “Now, sir, you gotta lop off this here leg, and if you flinch—well, sir, you get shot in the head.” Then he sat as steady as a rock while the mate went at it with the knife, holding the pistol unwaveringly until the operation was completed. No sooner was the stump wrapped up and the leg cast overboard than both men fainted.”

It was the captain's responsibility to provide medical treatment. Often without training himself, he was simply given a medicine chest full of numbered tinctures for various treatments. Those tinctures were a mix of chemical and herbal compounds, some which are still used holistically today and some that you.....absolutely want nowhere near your body. Epsom salts as a laxative, laudanum for painkiller, St John's wort for bruises and burns, mercury for syphilis, rosemary as an antiseptic, lead acetate as an anti-inflammatory, arrowroot for dysentery, henbane for insomnia, and on it goes from the innocuous to the dangerous.

John B King was a rare doctor aboard a whaleship, sailing on the Aurora out of Nantucket in 1837. He wasn’t hired as a doctor though; for reasons unknown he initially obscured his identity and joined simply as a foremasthand until his skills were revealed and he became the ship’s doctor. On that voyage he kept a book of the medicines he used.

John King’s medicine list, from the collections of the Nantucket Historical Association.

In addition to dosing medicine, the captain would also be responsible for setting broken bones, stitching wounds, and amputations. Benjamin Boodry, who had been whaling since the age of 13 and by 1856 was captain of the Fanny described instances in which he had to tend to his crew.

“At 2 o clock a cask of watter rooled away in the Bluber room and one John Haggerty tryed to stop it and got his leg broke just above the Nee there was another chance to show my surgical skill set it splinted it and bandaged it.” “McKee fel from the Main Topsail yard on deck bled him in both arms he came to some broke his arm and leg and badly bruised”.

Fortunately for McKee, his accident happened off the coast of Faial. The captain sent for a doctor ashore to examine him. He was advised to leave McKee in the Azores where he could receive more proper rest and treatment. But if land was a long way off, people had to make do the best they could.

Some captains had a better bedside manner than others. Where Silliman Ives felt terribly neglected in his illness, William Abbe of the Atkins Adams, 1859, had quite a different experience. He turned to the captain for help with a painful swelling on his hand that eventually grew so bad he was unable to use it.

“The captain was extremely tender in his treatment of my hand, pouring on laudanum to relieve the pain, lancing with caution and as tenderly as could he and using every means in his power to make me comfortable—washing my hand thrice a day with warm water and cutting away dead skin, pressing out matter in a manner that gained my affection + respect. Mrs. Wilson sent me preserved meats, pickled oysters, cake, buttered bread and seconded her husband in all his care. I felt a great deal of respect for both these kind people + shall repay it when I can […] The Cap treated us all with a care + skill that surprised me — I supposed that we should be left to take care of ourselves—the case in many ships, but we were not only cared for but allowed to stay below until we thought fit to return to duty.”

Mrs. Wilson--the captain’s wife--stepping up to help was not so unusual. Often whaling wives also found themselves taking on the role of doctor. All throughout July 1846, Mary Brewster was busy tending to the ailments of the crew aboard the Tiger.

“The last part of the day I have spent in making doses for the sick, in dressing some hands and feet, 5 sick and I am sent to for all the medicin. I am willing to do what can be done for any one particularly if sick for in whaling season a whaleship is a hard place for comfort for well ones and much more sick men.”

She reported that all her patients recovered, with the exception of a young man with a liver complaint beyond her immediate treatment.

Other times, other members of the crew served as de facto doctors as well. One such man was veteran whaler John Martin aboard the Lucy Ann 1842. In addition to being a skilled watercolorist, he also had a knack for bloodletting and tooth pulling. Often he made note of his ministrations in his journal:

“Blistered Frank on the side for his pleurisy & the steward on the neck for the sore throat” “Cupped the steward on the back of his neck with wine glasses and lanced with razor for want of proper instruments, which gave him almost instant relief” “Pulled a large jaw tooth for one of the crew. I lanced the gum with a penknife & set him spouting thick blood, & at the second wrench of the iron turned it up.” [Very cheeky language he’s using here, the same sort of talk one uses when hunting whales] “The loose whale struck Mr. Dean on the lower jaw & broke it, & knocked out 2 of his lower teeth, & he was taken on board [...] Sat up with Mr. Dean last night [...] Bled Mr. Dean [...] Drew 3 teeth from Mr. Deans broken jaw.” “Bled Antone. Since the death of Manuel, Antone has been on the sick list with swelled testicles and pain in his back. Poor fellow, he is very much frightened & thinks he is going to follow Manuel. He occupies the same bunk. When I bled him, he was so frightened that the perspiration stood on him in large drops, & groaned like a person dying.” “Blistered and glystered [clystered, i.e. gave an enema] Antone.”

One of John Martin’s watercolors from his journal. NBWM.

Blistering, bleeding, and emetics were among the most common treatments for all that ailed a man aboard. John King included his recipe for creating a blistering plaster and its uses:

“Blisters are serviceable in affections of the chest attended with much pain and difficulty of breathing. Bleeding or purging is proper previous to the application. Severe and long-continued headaches are relieved by a blister to the back of the neck. In all cases before applying a blister, the part should be washed with warm vinegar and wiped dry. The plaster should be spread as thick as a wafer on soft leather. When laid aside it soon becomes mouldy in the dampness of a ship, but if rubbed over with a knife the same one will draw two or three times. When very old it loses its strength. From eight to twelve hours is the time usually required for drawing a blister. Then remove it and dress with basilicon or simple ointment”

—

Other ailments were met with more specific treatments. It was not uncommon to see logbooks noting several men laid low on account of ‘the venereal’. William Chappell, a cooper and boatsteerer aboard the Saratoga in the early 1850s commented on the frequency the mate found himself off duty following liberty ashore.

“Our mate is off duty again with that disgracefull disease and as near as I can find out it threatens destruction to a small but very usefull member of the body I am sorry for him but he is old enough to know better than to play with every body that looks pretty and bewitching”

“Flaxseed tea is very serviceable in clap”, wrote John King in his journal, as well as white vitriol “sometimes used as an injection in protracted cases of clap.” For syphilis, the common treatments were more severe. King writes,

“No 25. Mercurial Ointment This is frequently used in venereal cases for bringing the system under the influence of mercury. The bulk of a small nutmeg is rubbed on the inside of the thighs morning and evening until the gums are slightly sore. It is a good application to chancres when mixed with twice the quantity of lard, and renewed twice a day.”

Mercury compounds could also be injected into the urethra. There were doctors who spoke out about the use of mercury in treating syphilis contemporary to when use was at its height. One 1853 advertisement in the New Bedford newspaper the Whaleman’s Shipping List reads,

“Important to the Afflicted CONFIDENTIAL TREATMENT in Medicine and Surgery may be had of Dr. TOMPKINS at his office in rear of the Apothecary’s Shop, No 58 Middle, corner of North Second St Dr. TOMPKINS gives particular attention to the treatment and cure of private diseases. All those who have been taking medicines of their own prescribing, or from certain inexperienced or self-styled physicians, for a long time without benefit, are respectfully invited to call on Dr Tompkins, who is a regularly educated Physician of twenty years experience, and is competent to treat diseases of all kinds, and in every stage and form. Dr. T. warns the public against the abuse of mercurials; he is convinced by long experience, that most of the chronic affections, generally supposed to be the relics of diseases, are merely the effects of a long continued course of mercury. Recent affections cured in a very short time, without a grain of mercury”

Even with such objections, mercury compounds still were the standard and did more to sicken their patients than cure them. While whalers were often listed as being off duty due to venereal disease, there was less comment about whether or not they were given anything to attempt to alleviate it compared to other conditions.

“Our mate limping about again—had another furious attact of the venereal He is a used up man I fear,” Mr. Chappell wrote. Ultimately the mate was in a poor enough condition that he left the voyage at the next provision stop they made.

—

Scurvy was another common affliction. Given that whaleships spent extended time at sea and were loathe to waste too much time with anchoring somewhere, fresh food ran low quite often. When whaling in the Atlantic and South Pacific whalers usually fared okay, as there were a fair number of provision stops in locations that had fresh fruits and vegetables readily available for trade. It was on said provision stops that whalers could also, as said by Samuel Wood of the Bowditch, 1849, take a walk to 'knock the scurvey from their bones’. In seasons that took place up north however, in the North Pacific, Sea of Okhotsk (Kamchatka Sea), Bering Strait, and eventually up into the Arctic, scurvy was extremely prevalent. The fresh food depleted, the ice was always a threat, and unlike other regions there weren't many accessible places to resupply with large amounts of foods that could ward off scurvy. It's in reading journals during these periods that I find the most complaints of scurvy. And sometimes, the more successful the voyage was, the sicker the men would get because they'd spend more time up there rather than giving up and returning south. The US Consul in Hawaii complained of this in the 1840s, saying:

"Whaleships were much more successful in taking oil on the North West during the last summer and fall than for three or four seasons previous and most of the vessels remained on the fishing grounds much longer than usual, the consequence of which was that many of the crews were severely afflicted with scurvy, some died after reaching port and before they could be landed, while others were carried to the hospital on litters, being too feeble to walk."

There were endless attempts to ward it off. John Martin wrote of men "In the evening, dancing cotillions and jumping the rope to keep off the scurvey". It didn't seem to do much. Within two weeks:

"One man on the sick list, supposed to be caused by his being so long at sea. All hands are complaining of soreness throughout their bodies. If we do not get on shore soon, we may expect to have half the crew down with the scurvey at least. We have no vegetables on board, and are going into King Georges Sound, New Holland [southwest tip of Australia], a place where we can scarcely get anything to recruit with."

His captain allowed the crew unlimited vinegar and free access to the potato pen. The vinegar, a mistaken remedy due to its acidity, wouldn't have helped much. Potatoes are an excellent source of vitamin C, more so when they're raw, but they were rather intolerable to eat in such a way.

William Chappell spoke of a similar struggle with potatoes, and the grim humor the lads maintained to choke them down:

“Three of our men are off duty with the scurvy which makes its appearance in the knees and feet All hands are called aft every morning to get 2 or 3 potatoes apies which they are required to eat raw in the preasance of the officers for fear they may throw them overboard as many require presing invitation to partake of the dainties They have however a considerable sport over them Call them Kodiak Peaches”\

Aside from the crunch of Kodiak Peaches, Dr. King had his own remedy for scurvy as well:

“13. Salts of Lemon This is good in scurvy when fresh fruit and vegetables can not be obtained. A teaspoonful dissolved in half a pint of water will form an acid nearly the strength of lime juice. It may be mixed with water and taken freely, sweetened or not. [it makes a good substitute for lemonade, in fever, to allay thirst in fever] Water made slightly acidic with it is a good substitute for lemonade to allay thirst in fever."

The Sailor’s Hospital in Lahaina, Maui, constructed in the early 1830s.

For all the varying attempts to hold off sickness, it took root among crews nearly every voyage. J.E. Haviland of the Baltic, in the early 1850s spent the last few dozen pages of his journal in a state of declining health and low spirits.

“My side and breast pain me nearly all times I have not been on deck since I came below. The Captain and Mr Stivers are both very kind and come down to see me as often as once a day and sometimes two or 3 times. I am taking medicine but it does not seem to do much good but I think I am better than I was at first. Dear mother how I do wish I could see you once more. I get so homesick and I know I am peevish and cross. Some days I cannot get out of my bunk at all. I blame the captain (wrongfully I know) thinking he does not give me the right medicine but it is a very bad place to be sick at sea.”

He suspected it was due to the harsh conditions of whaling up North, but also held a fear within him that it might be something more serious that couldn’t be remedied simply by warmer climes.

“Dear mother, I shall be obliged to leave the ship when we arive at the Sanwich Islands for I do not think I could live doing another season in the cold Norwest. My cough seems to increase and the pain in my side gets no better I am getting weaker each day and am getting very thin in flesh. I have said nothing as yet to the old man about my leaving at the island as I do not know as he will be willing that I should; but I intend going to a doctor and in all probability will tell the old man I am not fit to go North in the ship […] I would like very much to be in the states now for I am afraid this will turn out to be the Consumption that I have. I think if I could have good medical advice I might get rid of it before it got seated upon my lungs. I am afraid it will be a long before I shall see my native land again.”

Ultimately Haviland is discharged from the ship because of his sickness and is left at the Sailor’s Hospital in Lahaina. His stay seems to do him well. His last entry reads:

“I have been here now going on two months and am entirely free from my cough and think I feel as well as ever again. It is intensely hot and I am heartily sick of the place and sincerely wish I could get away but I do not expect any chance before next fall.”

Unfortunately from here he completely drops off the record, so it’s unknown if he ever made it back home. Like so many of these men, he slips through the cracks of documented history. It’s only through their journals, preserved by chance, that their voices and challenges and feelings are known. Often a whaling voyage marked at least one death due to disease or injury. But many also recovered, sometimes rather miraculously given the circumstances and extent of their ailments. In the face of the conditions of a whaler and the limitations of care both in terms of resources and medical understandings at the time, I’m always surprised that there wasn’t more death. People did what they could, with the knowledge they had.

But as so many people expressed while laid up in their bunks: it’s a hard time to be sick at sea.

#some of these things are repurposed from other asks#im still so surprised more people didn't die...#awhalin#haviland makes me sooo sad...and I didn't even include the bits that made me saddest...

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

François Raynal was a very pious man, having experienced a revelation his first night at sea, on December 23, 1844, at the age of just fourteen years and five months. As the land on the horizon disappeared, and “the limitless sea surrounded me; the celestial vault was for the first time displayed before my eyes in all its vastness; I was plunged everywhere into the Infinite.”

Joan Druett, Island of the Lost: Shipwrecked at the Edge of the World

#ALSO. I am still on my age of sail bullshit#consider once more the universal cannibalism of the sea#hold up I gotta find the matching moby dick quote to this one#reading log

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

apparently there's a book called Island of the Lost

it was published in 2007 by someone named Joan Druett.

And Joan, girlypop, if you're seeing this, first of all there's no way in hell you named a book that at peak popularity of a show named Lost that took place on an Island and did not know what you were doing.

Second of all, no one cares about your book and I'm still naming my comic that 💅💅💅

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve jammed together a couple of those get to know you things:

last five google searches / Records / books / WIP.

Google search enjoy my terrible spelling / grammar/ typing for the lols exactly as I wrote them

Are glaciers freshwater

How many kits foxhave

Cal cornflakkes keloggs

epl games—-

Sheffield blades squad

That wasn’t as bad as I thought!

I recall this being favourite books?

Choo Woo - Lloyd James look this book was devastating. I read it once and I can’t ever read it again. I can’t even be sure I can recommend it.

Krakatoa - the day the world exploded Simon Winchester

After the quake - Haruki Murakami

English Passengers- Matthew Kneale

Island of the lost - Joan Druett

Last full albums, I’ve been working though the history of music. Man do I not give a shit about The Beatles. Anyway left the album with my favourite song.

This is my Frank Lampard AU song

WIP titles and description

The ocean on top of the ocean (the world ends. It’s not all bad. This has a hopeful happy ending, the middle bits I don’t want to trick you in to reading but they all happen off screen)

The Parade. (Ghosts haunt John Stones. They aren’t real. Well they are real. They aren’t ghosts. He doesn’t deserve it. (He does sort of deserve it.).)

Flyboys (I have yet to decide on a proper name. Harry Kane used to be an accountant, and a pilot and a (redacted).

Spain 3 (also still settling on a name) Frank Lampard / John Terry (if John was that way inclined. The shadows of hard men hang over Frank.)

Getting there. The third part, so Jordan / John. (What turns me on is you being turned on, also condoms are terrible and you should meet this guy…)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mystery/Thriller Monday

Benjamin January is a piano player, a doctor, and a free Black man in New Orleans in 1833. He has previously lived for years in Paris, and so, coming back to New Orleans in the 1830s is most definitely not the same. And then (since this is Mystery/Thriller Monday) he’s suspected of murder. A pretty good scapegoat for a police force that isn’t super thrilled to have to probe this case. So, Benjamin is on the case himself, trying to figure out who murdered Angelique Crozat.

It was such a great start to a series (yep, it’s a series with a lot of books in it, which I love). Benjamin was not a straightforward character, but, had lots of layers (which I assume we’ll get even more of in the next books). And, learning about New Orleans through the story was tons of fun too. It’s a dense book, but, a good dense book for sure, not a bad dense book.

You may like this book If you Liked: Darktown by Thomas Mullen, The Long-Legged Fly by James Sallis, or A Watery Grave by Joan Druett

A Free Man of Color by Barbara Hambly

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

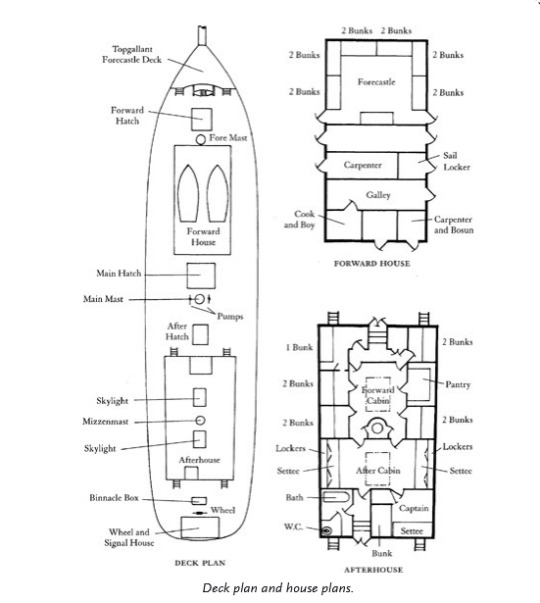

You had me at In The Heart Of The Sea 🥰 (Well, actually it was at 'sad boat people') If I could add a few from 4 seasons of survival cannibalism research:

Sad Balloon Club

N-4 Down: The Hunt for the Arctic Airship Italia by Mark Piesing

Non-polar sad boats

Surviving the Essex: The Afterlife of America's Most Storied Shipwreck by David O. Dowling

Miscellaneous sad boat books that are well worth your time

Ghosts of Cape Sabine: The Harrowing True Story of the Greely Expedition by Leonard F Guttridge

Island of the Lost: Shipwrecked at the Edge of the World by Joan Druett

(And remember that we have a full bibliography available for every episode, so lots of sad boat books linked on the pod!)

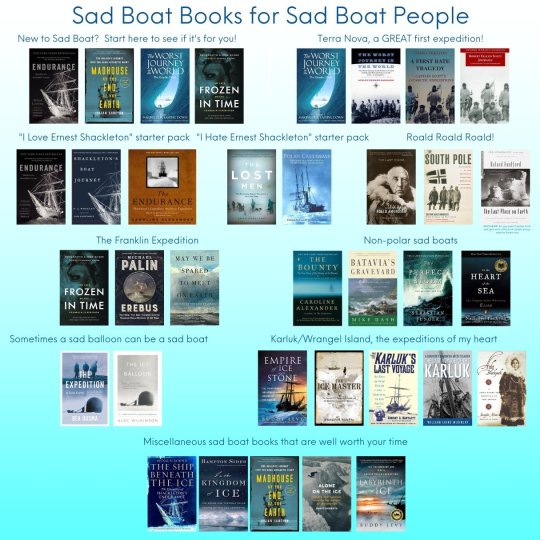

I guess it's time to start moving some content from twt over here! For those who don't know me, I'm a public librarian with a special interest in polar and nautical history, and I love nothing more than connecting readers with good books. I've managed to convert some friends to my way of thinking, and one of them coined the phrase "sad boat books" to describe the types of books that I'm always reading and recommending. Here is my first list of sad boat books-- I can personally vouch for all of them!

New to sad boat? Start here to see if it’s for you!

Endurance by Alfred Lansing

Madhouse at the End of the Earth by Julian Sancton

The Worst Journey in the World- The Graphic Novel Volume 1: Making Our Easting Down adapted by Sarah Airriess from the book by Apsley Cherry-Garrard

Frozen in Time: The Fate of the Franklin Expedition by Owen Beattie and John Geiger

Terra Nova, A GREAT first expedition!

The Worst Journey in the World- The Graphic Novel Volume 1: Making Our Easting Down adapted by Sarah Airriess from the book by Apsley Cherry-Garrard

The Worst Journey in the World by Apsley Cherry-Garrard

A First Rate Tragedy by Diana Preston

Robert Falcon Scott Journals- Captain Scott’s Last Expedition by Robert Falcon Scott

“I Love Ernest Shackleton” starter pack

Endurance by Alfred Lansing

Shackleton’s Boat Journey by Frank Worsley

The Endurance by Caroline Alexander

“I Hate Ernest Shackleton” starter pack

The Lost Men by Kelly Tyler-Lewis

Polar Castaways by Richard McElrea and David Harrowfield

Roald Roald Roald!

The Last Viking: The Life of Roald Amundsen by Stephen Bown

The South Pole by Roald Amundsen

The Last Place on Earth by Roland Huntford*

*DISCLAIMER: this guy hates Captain Scott and gets most of the Scott details wrong, read for Roald only!

The Franklin Expedition

Frozen in Time: The Fate of the Franklin Expedition by Owen Beattie and John Geiger

Erebus by Michael Palin

May We Be Spared to Meet on Earth: Letters of the Lost Franklin Expedition edited by Russell A. Potter, Regina Koellner, Peter Carney, and Mary Williamson

Non-polar sad boats

The Bounty by Caroline Alexander

Batavia’s Graveyard by Mike Dash

The Perfect Storm by Sebastian Junger

In The Heart of the Sea by Nathaniel Philbrick

Sometimes a sad balloon can be a sad boat

The Expedition by Bea Uusma

The Ice Balloon by Alec Wilkinson

Karluk/Wrangel Island, the expeditions of my heart

Empire of Ice and Stone: The Disastrous and Heroic Voyage of the Karluk by Buddy Levy

The Ice Master by Jennifer Niven

The Karluk’s Last Voyage by Robert A. Bartlett

The Last Voyage of the Karluk: A Survivor’s Memoir of Arctic Disaster by William Laird McKinlay

Ada Blackjack: A True Story of Survival in the Arctic by Jennifer Niven

Miscellaneous sad boat books that are well worth your time

The Ship Beneath the Ice: The Discovery of Shackleton’s Endurance by Mensun Bound

In The Kingdom of Ice: The Grand and Terrible Polar Voyage of the USS Jeannette by Hampton Sides

Madhouse at the End of the Earth by Julian Sancton

Alone on the Ice: The Greatest Survival Story in the History of Exploration by David Roberts

Labyrinth of Ice: The Triumphant and Tragic Greely Polar Expedition by Buddy Levy

If you read and enjoy any of these, please let me know!

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Whaler 'Harpooner', c. 1831 (Science Museum)

Should an 1830s medical man long for the experience of strange seas and wondrous lands, he might find himself a position as a surgeon on a whaling ship, as described by Joan Druett in Rough Medicine: Surgeons at Sea in the Age of Sail:

Dr. James Brown found his ship in London. Accordingly, he was on board when the Japan was "towed by the Nelson, Tug Steamboat to Gravesend," on December 15, 1834. In May 1837, Dr. Fysh of the Coronet had the same experience, except that his ship was towed by the Tam O'Shanter. "All the men or nearly all drunk," he noted, adding, "That's nothing! It will be long before Jack [slang for a sailor] gets another chance of being so again! So go it my Boys make the best of your time."

Liverpool whaler c. 1834, Francis Hustwick (Ferens Art Gallery)

On October 14, 1837, on the far side of the Atlantic, another of our whaling surgeons boarded his ship—but probably not in a spirit of high adventure and lively anticipation. His feelings, by contrast, were much harder to gauge, since he had signed on to the voyage under very strange circumstances for a gentleman of his attainments.

This fellow's name was John B. King, and he hailed from the island of Nantucket. While London whalers finished their fitting out at Gravesend, Nantucket whaleships completed their preparations for voyage at Edgartown, Martha's Vineyard, where Dr. King arrived on that date. [...] In 1832, at the age of twenty-four, King had graduated from the New York College of Physicians and Surgeons with the very substantial degree of Doctor of Medicine and Surgery. He was immediately awarded a certificate that allowed him to practice in New York [...] These elaborate qualifications failed to settle him down. He moved to Nantucket—and then he signed onto the whaler.

It was a most eccentric decision. For a start, there was no legal reason for Dr. King to be on board the Aurora. While an English whaling master was required by law to ship a surgeon, American whaleship captains were not.

— Joan Druett, Rough Medicine: Surgeons at Sea in the Age of Sail

'South Sea Whale Fishery': 1834 print by William John Huggins (New Bedford Whaling Museum)

#1830s#Eighteen-Thirties Thursday#whaling#whalers#age of sail#age of steam#whaleship surgeons#history of medicine#medicine at sea#rough medicine#joan druett#naval art#the sea

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

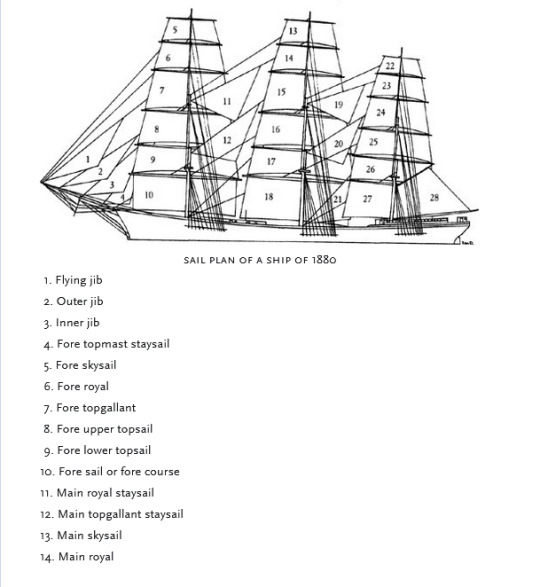

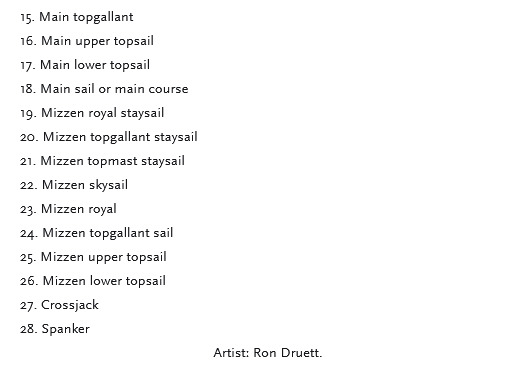

Sail plan and deckplan of a full rigged ship of 1880, by Ron Druett in: Hen Frigates, by Joan Druett

333 notes

·

View notes

Text

There's so much depth and nuance and social complexity brought to the examination of American whaling history that I've seen from women and nonbinary scholars, in a way that tends to be absent or more surface in the books written by cis men. Nancy Shoemaker, Margaret Creighton, Joan Druett. From the brief window Marina Wells gave on their research in their part of this symposium, I can't wait for them to write a book now too...

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

1. City of Fortune : How Venice Ruled the Seas - Roger Crowley

2. Empires of the Sea : The Siege of Malta , the Battle of Lepanto , & the Contest for the Center of the World - Roger Crowley

3. Empires of the Sea : The Final Battle for the Mediterranean , 1521 - 1580 - Roger Crowley

4. Empires of the Sea : Maritime Power Networks in World History - Rolf Strootman / Roy van Wijk / Floris van den Eijnde

5. The Sea in History : The Modern World - Christian Buchet

6. The Great Sea : A Human History of the Mediterranean - David Abulafia

7. The Boundless Sea : A Human History of the Oceans - David Abulafia

8. A World History of the Seas : From Harbour to Horizon - Michael North

9. The Sea & Civilization : A Maritime History of the World - Lincoln Paine

10. The Sea in World History : Exploration , Travel , & Trade - Stephen K. Stein

11. Pirate Queens - Leigh Lewis

12. Pirate Women - Laura Sook Duncombe

13. Daring Pirate Women - Anne Wallace Sharp

14. Seafaring Women : Adventures of Pirate Queens , Female Stowaways , & Sailors’ Wives - David Cordingly

15. She Captains : Heroines & Hellions of the Sea - Joan Druett

A Clipper at Sunset, 1877 by Edward Moran

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Island of the Lost by Joan Druett

Island of the Lost by Joan Druett

Title: Island of the LostAuthor: Joan DruettRating Out of 5: 2 (Managed to read it… just)My Bookshelves: Biographies, History, OceansPace: SlowFormat: eBook, NovelYear: 2007 This was an incredibly well researched book. It was even well written, a little dry, but not overbearingly so. It stated the facts and gave you a bit of a personality insight into each of the key players without taking too…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

||October BPC: Just One Word|| 30. Recap. Okay, we’re re-relocating the Recap pictures, since I am Supremely Lazy and if I take the pics in my (much better lit than my parents’ house) room, I don’t have to haul things anywhere! So here’s what I read this month, and also I plotted my NaNovel! Solid October, I think.

#just one more page#just one word book photo challenge#still life with woodpecker#tom robbins#captive prince#cs pacat#exo#fonda lee#the absolutely true diary of a part time indian#sherman alexie#the hundred thousand kingdoms#the broken kingdoms#the kingdom of gods#nk jemisin#hen frigates#joan druett#pagans#james j o'donnell#hidden figures#margot lee shetterly#tell the wolves i'm home#carol rifka

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is a surgeon but a miserable pile of unqualified whaling captains

#just four chads chillin' as john doe writhes in agony#from rough medicine: surgeons at sea during the age of sail by joan druett#literacy fun

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

- The Woman Who Would Be King by Kara Cooney (an excellent biography of the female pharaoh Hatshepsut)

- Cræft by Alex Langlands (a really fascinating dive into the meaning of historical craftsmanship in an increasingly mechanized and over complicated world)

- How to be a Tudor by Ruth Goodman (what it says on the tin)

- Breaking the Maya Code by Michael Coe (I’ve only watched the documentary version but holy shit it’s my favorite thing)

- Pirate Hunters by Robert Kurson (two New York divers try to find a pirate ship)

- Island of the Lost by Joan Druett (an absolutely batshit story of shipwrecked sailors in the nineteenth century and the ridiculous ingenuity of one of them)

- The Radium Girls by Kate Moore (this one’s a little intense but is very worth a read; hugely eye opening about just how long companies have been intentionally fucking ppl over)

- The Plantagenets by Dan Jones (very long but an EXCELLENT overview of an often overlooked and misunderstood dynasty)

Ok tumblr friends. I’m trying to spend less time on the internet these days, and I LOVE reading non-fiction books, but trying to find recommendations for new books is a nightmare. Any time I try to look up good new non-fiction books the results are all like “would you like to read an autobiography of Paul Newman or New Reasons We’re All Doomed” and that just. Doesn’t Work for Me. So I’m asking for recs here. I’m open to books about literally any field or topic. Only caveats are that hard sciences have to be on a level I can understand as a humanities person, and medical stuff can’t be too gory (ie I loved Siddhartha Mukherjee’s The Gene and The Song of the Cell, but can’t stomach The Mother of all Maladies). And nothing TOO miserable, but I have a fairly high tolerance for historical stuff. I’m particularly fond of micro-history and books that delve into multiple overlapping topics.

As a sampling, here are some books I’ve read and particularly enjoyed in the last two years:

Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder by Caroline Fraser

The Cooking Gene by Michael Twitty

The Gene: An Intimate History by Siddhartha Mukherjee

Song of the Cell by Siddhartha Mukherjee

On Savage Shores: How Indigenous Americans Discovered Europe by Caroline Pennock

Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs by Camilla Townsend

The Five: The Untold Lives of the Victims of Jack the Ripper by Hallie Rubenhold

The Last Days of the Incas by Kim McQuarrie

The Dream and the Nightmare: The Story of the Syrians who Boarded the Titanic by Leila Salloum Elias

Life on a Young Planet: The First Three Billion Yeats by Andrew Knoll

Salt: A World History by Mark Kurlansky

The Food of a Younger Land by Mark Kurlansky

Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking by Anya von Bremzen

Jesus and John Wayne by Kristine Kobes du Mez

Kingdom of Characters: The Language Revolution that made China Modern by JIng Tsu

The Last Island: Discovery, Defiance, and the Most Elusive Tribe on Earth by Adam Goodheart

Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake

National Dish: Around the World in Search of Food, History, and the Meaning of Home by Anya von Bremzen

The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World by David W. Anthony

The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny, and Murder by David Grann

Fire away!

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Grace O’Malley - Terror of the seas

Gráinne Ní Mháille, more often called Grace O’Malley (circa 1530–1603), also nicknamed as Gráinne Mhaol (“the bald Grace”) because she kept her hair short, was an Irish pirate.

Grace’s father was a powerful chieftain who owned a large fleet for both trading and raiding. In 1546, she was married to Donal-an-Cogahaidh (Donal of the Battles), heir apparent of the O’Flahertys of Ballinahinch, thus linking their two powerful families. Grace gave birth to a daughter and two sons, but her husband died in battle. She avenged him, leading the O’Flahertys in a raid during which she showed great courage and captured her enemies’ island bastion.

Irish law, however, forbade her to take the clan’s leadership and her husband’s cousin succeeded him. Grace took the O’Flaherty men that were still loyal to her and returned to her father’s territory. She then began her career as a pirate and quickly established a reputation as a skilled admiral, using her knowledge of the coves and reefs of western Ireland. She raided merchant fleets in the seas between Scotland, England and the Continent. Grace was so successful that she even managed to recruit men from enemy clans.

Grace then strengthened her territory by marrying , another important chieftain: Richard-an-Iarainn,”Richard-In-Iron”, Burke. It was said that she stipulated that the marriage was for a year only and that each party would then be able to withdraw if needed. She reportedly waited until she had control of his lands, took over his castle and shouted from the battlements “I dismiss you!”. The two nonetheless remained married, at least in name only.

Grace and Richard had a son together, named Tibbott-ne-Long (”Toby of the ships”) because a was born at sea. The day after Grace had given birth, her ship was reportedly attacked by Turkish corsairs. Her men were overwhelmed and called for her. She got out of bed and said “May you be seven times worse in one year, seeing you can’t manage for even one day without me”. She then grabbed two blunderbusses and fired them at the Turkish, saying “Take this from an infidel hand!” She then managed to capture the enemy ship.

In 1577, she was captured by the Great Earl of Desmond, but was released 18 months later, with the condition that she would help to curb her husband who was involved in a rebellion. She, however, took advantage of the situation to join forces with him.

Richard died in 1583. Grace pursued her activities, but was captured again in 1586 and freed when her son-in-law exchanged himself for her. Her son Owen was later murdered by Richard Bingham, the British governor of Connacht. Grace rose against him, calling on Scottish mercenaries. She led deadly ambushes, appearing and disappearing as she came.

In 1592, Bingham raided her territory at Clare Island and captured her fleet. She escaped to Ulster where she took refuge with the local clans. Grace decided to petition queen Elizabeth I. In July 1593, she sent a letter asking that her two surviving sons might hold their lands by the right of English law. She also pleaded the queen to “grant her some reasonable maintenance for the little time she has to live”. She promised in return to “invade with sword and fire all your Highness enemies”. The queen sent her 18 “Articles of Interrogatory” that Grace filled.

She was then summoned to Greenwich Palace. The queen reportedly offered her a fancy handkerchief. Grace used it to whip her nose and then threw it into the fire. A courtier called her on her behavior, saying that in England no one threw handkerchiefs into the fire but she answered: “ What? You save a dirty piece of cloth? The queen may do this, but not I”.

Elizabeth granted her the pension and asked that her son Tibbott-ne-Long, who was held by Bingham, should be set free. In 1595, Bingham was recalled in disgrace. So Grace, who was at that time more than 60, went back to pirating. She ultimately remembered her commitment to the queen and put her son Tibbott-ne-Long in charge of her fleet, asking him to fight for Elizabeth. She died the same year as the queen, in 1603.

Bibliography:

Druett Joan, She-captains, heroines and hellions of the sea

Sjoholm Barbara, The pirate queen: in search of Grace O’Malley and other legendary women of the sea

Sook Ducombe Laura, Pirate women, the princesses, prostitutes and privateers who ruled the seven seas

#grace o'malley#history#women in history#warrior women#pirate women#badass women#ireland#irish history#Elizabeth I#16th century#war#military history

1K notes

·

View notes