#jean hyppolite

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

TODAY IN PHILOSOPHY OF HISTORY

Hyppolite’s Reading of Hegel’s Philosophy of History

Wednesday 08 January 2025 is the 118th anniversary of the birth of Jean Hyppolite (08 January 1907 - 26 October 1968), who was born in Jonzac, Poitou-Charentes, on this date in 1907.

Hyppolite was an influential French Hegelian whose works brought Hegel back into discussion in Francophone philosophy. He wrote a long book on Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit and a short book on Hegel’s philosophy of history. Hyppolite’s non-Hegelian temperament gives his readings of Hegel a Gallic flavor that helped to naturalize Hegel within twentieth century French philosophy.

Quora: https://philosophyofhistory.quora.com/

Discord: https://discord.gg/r3dudQvGxD

Links: https://jnnielsen.carrd.co/

Newsletter: http://eepurl.com/dMh0_-/

Text post: https://geopolicraticus.substack.com/p/hyppolites-reading-of-hegels-philosophy

Video: https://youtu.be/ItufVrlo_lc

Podcast: https://open.spotify.com/episode/3pO0ATUnBFGTZt33VYLBIY

Episode: S02EP03

0 notes

Text

#book review#Genesis and Structure of Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit#Jean Hyppolite#Samuel Cherniak#John Heckman#1974

0 notes

Text

Hector Hyppolite (Haitian, Saint-Marc 1894–1948 Port-au-Prince) Ogou Feray, also known as Ogoun Ferraille, ca. 1945

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled, 1981

#jean michel basquiat#Hector Hyppolite#hatian artist#hatian painter#surrealism#surrealist#lettrism#lettrist#black artists#black painters#aesthetic#modern art#art history#tumblr art#beauty#tumblrpic#tumblrpictures#tumblraesthetic#aesthetictumblr

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Buud Yam, Gaston Kaboré (1997)

#Gaston Kaboré#Serge Yanogo#Amssatou Maïga#Colette Kaboré#Mariama Ly#Hyppolite Ouangrawa#Boureima Ouedraogo#Rasmané Ouédraogo#Joseph Yanogo#Jean Noël Ferragut#Michel Portal#Marie Jeanne Kanyala#Didier Ranz#1997

1 note

·

View note

Text

thoughts i've had while reading the Foucault biography by David Macey:

(1) Foucault was a bourgeois and his entry into the elite higher educational institutions involved a number of processes that were designed very specifically to select for the children of bourgeois, in a way that reminds me a lot of the recent post by gothhabiba (click). one example which particular concerns philosophy is that entering the highly competiitve ENS would require knowledge of philosophy (Kant etc.), which was only taught to highschool students at the fee-charging lycees. further, philosophy was taught at lycees by ENS graduates, who may also be on the comittee that selects ENS applicants. this—along with a few direct interventions of actual nepotism—is how Foucault got there in the first place, because some (FAMOUS) men (like Jean Hyppolite!) met him as a child and decided he was 'very intelligent'. the same story repeats when Foucault gets his first few academic posts, with recognizable names balancing the scales for him. this does not seem to be something special but rather how all applications were judged and posts filled. there is a more subtle example for which analysis would be possible, but the book doesn't offer enough information, which is in the explicit discussion about how the topics for the oral agregation (necessary for graduation) should be selected. Macey concludes the section by saying that "[t]he 1951 agrégation [when Foucault graduated] had been a ‘Malthusian’ process of elimination: fourteen candidates were successful, and five of them were normaliens [ENS students]."

(2) throughout his youth into his late 20s (ie. the part i've read so far), Foucault seems to only ever—with the exception of patients and prisoners he met at the clinic when he worked there—interact with other members of the French elite. even in the communist party he attends a special ENS chapter and so forth. this may simply be because only famous men leave information to posterity, so we know less about Foucault's non-elite associations, or even that Macey just has nothing to say about those relationships, but it is quite striking. the same is not true of Deleuze per François Dosse's dual biography of Deleuze & Guattari (i mean anyway we talk about him in the same breath as Guattari who was not part of this system at all).

(3) he loved serialist music and had a live-in romantic relationship with a serialist composer named Jean Barraqué who was taught by Oliver Messaien. isn't that cool? they would go drinking between classes, just like we did when we studied serialism... haah...

(4) the biography skips around in time quite a bit; when Foucault first meets someone who will become important to his life we get a sort of summary of their whole relationship in rapid diegesis which will reoccur in a slower, although still diegetic, pace later in the book. this reminds me a lot of the way the Norse Sagas are written; in his excellent introduction to the Saga of Hrolf Kraki, Jesse Byock remarks that the author makes clear that he is compiling fragmentary sources by "telling the audience when one sub-tale ends and another begins: ‘Here ends the tale of Frodi and now begins the story of Hroar and Helgi, the sons of Halfdan.’" the biography of course also does this by explicitly mentioning, either in the text or in a footnote, which sources (books, interviews, letters, personal correspondences) the story is compiled from. when i thought about the Sagas i had thought of it as producing a very strange literary effect, almost like a Brechtian distancing effect, freely dispensing of suspense to remind the reader of the structural components of the narrative, and i have written some stories which try to perform this idea. however, now i realize that we still do this quite often, only in that peculiar form of literature called the biography, where it appears quite natural and doesn't surprise the reader. i think one explanation for the strangeness in the Sagas is that the Sagas are primarily in mimesis, and the sudden episodes of diegesis during which the story and the plot become momentarily disimbricated are surprising to a modern reader.

(5) Foucault suffers a bitter quarrel with another gay man named Jean-Paul Aron he was previously friends with which they would never rapproach. the reason for this quarrel is, according to Macey, because "one of Aron’s young lovers fled and took refuge with Foucault." Macey discusses this entirely in terms of "sexual jealousy" and "envy"—i suppose Macey is heterosexual because oh my god. doesn't that sound like such a familliar story to us... the guy had to run away from his partner and go and live with someone else over it... and it caused scene drama for the rest of their lives... what was going on there?

(6) in discussing the homophobia of the official French Communist Party to which Foucault belonged until 1953 (which was explicitly homophobic) the principal example which Macey chooses is a case where they expelled a highschool teacher for propositioning a pupil. for Macey this seems to only have the dimension of homosexuality, and neither the power dynamics of teacher and pupil nor the fact that the pupil was presumably a child are mentioned at all. this biography was written in 1993. it made me think immediately of a number of other instances of an adult man having or attempting a sexual interaction with an underaged boy, being penalized or imprisoned in some way, and the response of, essentially, the legitimate gay movement was to call it homophobic. i don't remember his name, but there was one composer, i think an American, in the 40s or 50s, who was imprisoned for sleeping with a 17 year old boy, and people came to his defense and considered the prosecution homophobic; similarly this highly sympathetic article (click) on the GLBT Encyclopedia Project about NAMBLA (who's periodical Delany used to read and recommend, something which he gets and still responds to emails about today), which opens with mention of "a successful effort on the part of gay activists to thwart a move by then-Boston District Attorney Garret Byrne to ferret out patrons of teenage male prostitutes via an anonymous telephone tip line", paints a picture where NAMBLA were relatively mainstream until the mid-80s. while i suspect this article of being at least a little apologetic it does also talk about gay organizing around changing age of consent laws & a line on how unequal enforcement of the age of consent was a tool to enforce homophobia, listing some impressive names who engaged in this kind of activism like Kate Millet and Gayle Rubin. and we also have, very infamously, Foucault's own advocacy on precisely the same thing, around the time of the petition, signed by Foucault and virtually every other French radical intellectual, to abolish the age of consent.

what do you think? from here doesn't it all look like a catastrophic blunder, something we're ashamed to remember and frightened to talk about? even when we're coming from an anti-carcereal, reparative, critical kind of perspective, something about the kind of narratives, defenses and advocacy from back then on such issues leaves us feeling alienated. i tend to think of it like this: that there was a historical situation where 1. all forms of homosexuality were illegal, 2. homosexuality was primarily understood in society, by both the right and left, as a kind of pedophilia, and 3. the concept of the age of consent was being redefined, socially and legally, at that time. this third point is specifically what Foucault was discussing in that interview, but i was interested to see the same point come up in a Defunctland video (click)(!), because—get this—one of the songs performed by Disney's in-house rock band Halyx was called 'Jailbait', and he asks the writer about it. on relistening to the song she immediately laughs in embarassment and says "please! what was i thinking back then!" and she has to basically do her own kind of historical-juridicial-philological analysis to attempt an explanation (timestamp), saying that they had "just done this thing saying that if you're over 18..." and so forth. her song by that title was performed by a female singer, and watching the performance i got the feeling that the intention was sort of twofold; in the first case, to exploit the imaginary erotic power of forbidden love ("i want you, baby / but you're jailbait"), and, in the context of a live performance, make the teenage boys in the audience feel wanted. i am not sure if the same effect is intended in Motorhead's song by that title ("i don't even dare to ask your age"). by the 90s you didn't get songs like this anymore; Boogie Down Productions' '13 and Good' is both condemnatory and paranoid and explicitly names it "statutory rape."

this isn't really a good thread of argument; i am not comparing like evidence. and i'd like to investigate contrary examples from that period—the documentary on NAMBLA Chickenhawk for example shows lesbian groups attacking NAMBLA members at demonstrations, and Andrea Dworkin was famously critical of NAMBLA—but i am anyway kind of interpreting Macey's framing as a 'pagan survival' of an older approach to these issues when they arose in a very different polemical context.

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

“La filosofía no debe ser un sistema cerrado de reglas y teorías, sino un proceso de interrogación constante y desestabilización de conceptos establecidos”

Jacques Derrida

Fue un filósofo francés de origen argelino nacido en El-Biar Argelia Francesa en julio de 1930. Conocido popularmente por desarrollar un análisis semiótico conocido como deconstrucción. Señalado por algunos como el máximo exponente de la corriente denominada filosofía de la diferencia.

Primeros años

Jacques nació en el seno de una familia judío- sefardí de clase media acomodada originaria de Toledo. Sufrió la represión del gobierno de Vichy siendo expulsado en 1942 de su instituto por motivos racistas. Este trauma que recordaría toda su vida le ayudaría a construir su personalidad.

Soñó con ser futbolista profesional, participó en diversas competencias y es en esa época de juventud, que leyó con pasión a novelistas clásicos y filósofos y escritores como Albert Camus, Rousseau, Nietzsche y André Guide.

En 1953 ingresó a la Escuela Normal Superior francesa en donde descubrió las obras de Kierkegaard, Martín Heidegger y Louis Althusser, este último sería su tutor y amigo de toda la vida.

En 1957 se casa con la psicoanalista y traductora Marguerite Aucouturier con quien procreó 2 hijos. De vuelta en Argelia para cursar su servicio militar conoce a Pierre Bourdieu mientras imparte clases de inglés y de francés, regresando a Francia en 1959.

En 1965 obtiene el cargo de Director de Estudios del departamento de filosofía de la École Normale Supérieure en donde establece amistad con Georges Canguilhem y Michel Foucault.

Encuentro sobre las ciencias francesas

En 1964 participa en el Encuentro sobre las ciencias francesas en Baltimore junto con Jacques Lacan, Roland Barthes, Jean Hyppolite y Lucien Goldman lo cual resultará decisivo para su reconocimiento internacional, y es ahí en donde conoce al director del departamento de literatura comparada de la Universidad de Yale y miembro de la Yale School of Deconstruction, Paul Man.

Obras

En 1967 publica al mismo tiempo tres obras capitales de su pensamiento, la primera, titulada “De la Gramatología”, realiza un análisis sistemático del origen del lenguaje en las obras de Saussure, Rousseau y Levi-Strauss. En su segunda obra titulada “La escritura y la diferencia”, ofrece una recopilación de artículos de Foucault, Levinas, Husserl, Heidegger, Hegel, Bataille, y el poeta y dramaturgo Artaud.

Deconstrucción

Jacques Derrida es reconocido entre otras cosas por haber desarrollado la “Deconstrucción”, el cual hace referencia a un acto bastante complejo en donde se analizan paradigmas conceptuales en los que se ha asentado la sociedad occidental desde los inicios de la filosofía griega hasta nuestros tiempos y cuya interpretación y aplicaciones pueden ser muy distintas, y que marcaron la producción filosófica de buena parte del siglo XIX y XX.

Gramatología

Otro concepto publicado en uno de sus libros de Derrida denominado “De la Gramatología”, desarrolla todas las consecuencias que sus análisis de la fenomenología trascendental tienen para la noción de “escritura” en contraposición a la primacía del “Habla”, haciendo del fonocentrismo, la base del logocentrismo. En donde para Derrida el concepto de escritura es un concepto cercano a la semiótica o ciencia de los signos, abarcando todo lo inabarcable al juego de referencias significantes que constituye para el el lenguaje.

Deconstrucción y psicoanálisis

Jacques Derrida siempre argumentó que “la deconstrucción del logocentrismo no es un psicoanálisis de la filosofía,” y trató de evitar la comparación del inconsciente psicoanalítico, desarrollando para ello la noción de “archivo”, que no implica la inscripción inconsciente de lo reprimido u olvidado, sino mas bien un acto consciente de “archivar”, en donde el “archivo”, es el suplemento de una memoria que ya no es la vulgar concepción de la memoria espontánea, sino mas bien una memoria “protética” del soporte técnico.

La discusion de Derrida con el psicoanálisis no concierne únicamente a la deconstrucción de los textos de Freud sino también a los de Jacques Lacan, y especialmente a su famoso “seminario de la carta robada” basado en la interpretación Lacaniana de un texto de Edgar Allan Poe.

Al deconstruir la obra de eruditos anteriores, Derrida trata de demostrar que el lenguaje está cambiando de una forma constante.

Fue precursor de una gran reflexión critica sobre la institución de la filosofía y sus formas de enseñanza de esta materia de tal forma que lo llevó a crear el Colegio Internacional de Filosofía que presidió hasta 1985.

Como activista político apoyó a los intelectuales checos en contra del “apartheid” sudafricano, o por su preocupación por el pueblo palestino.

Muerte

Derrida falleció en París en octubre de 2004 a causa de un cáncer de páncreas a la edad de 74 años.

Fuentes: Wikipedia, psicologiaymente.com, philosphica.info, biografiasyvidas.com, buscabiografias.com

#jacques derrida#filosofía#filósofos#deconstruccion#frases de reflexion#notasfilosoficas#frases de escritores#frases de filósofos#francia

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Homage to the Hommage à Jean Hyppolite’ - Philosophy, Politics and Critique Vol 1 No 3 theme section

‘Homage to the Hommage à Jean Hyppolite’ – Philosophy, Politics and Critique Vol 1 No 3 theme section Introduction and three essays – all require subscription, unfortunately: Joe Hughes, Introduction Christopher O’Neill, Error, Truth and Anxiety against Death: Reading Georges Canguilhem’s ‘On Science and Counter-Science’ Lachlan Wells, François Dagognet on Jean Hyppolite and the ‘Epistemology…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Quote

Resulta evidente que decir 'aquí' o 'ahora', lo cual parece ser lo más determinado, es en realidad hablar de cualquier momento de tiempo o de cualquier punto del espacio. Lo más preciso es también lo más vago. Pero de una manera general, el ser que es lo inmediato, la verdad esencial de la certeza sensible, es él mismo todo ser y no es ninguno; es, por tanto, negación y no solamente posición, como se afirmaba al principio. La certeza sensible ilustra así el primer teorema de la lógica hegeliana, que consiste en que al poner lo inmediato, el ser se descubre como idéntico a la nada. La posición del ser se niega a sí misma

Jean Hyppolite “Génesis y Estructura de la Fenomenología del Espíritu”

#Génesis y Estructura de la Fenomenología del Espíritu#jean hyppolite#hegel#La fenomenología del espíritu#la ciencia de la lógica#ontología#ser#nada

1 note

·

View note

Text

otto gennaio

Gianni Dova, Torso e nudo, (1960)

Ieri sera, uscendo per una passeggiata, ho visto nella crepa di un muro una lucciola. Non ne vedevo, in questa campagna, da almeno quarant’anni: e perciò credetti dapprima si trattasse di uno schisto del gesso con cui erano state murate le pietre o di una scaglia di specchio; e che la luce della luna, ricamandosi tra le fronde, ne traesse quei riflessi…

View On WordPress

#Baltasar Gracián#Charles Tomlinson#Ernesto Ragazzoni#Fritz Saxl#Giacinto Scelsi#Gianni Dova#Giulio Alfredo Maccacaro#Giuseppe Brancale#Jean Hyppolite#Juan Marsé#Lawrence Alma-Tadema#Leonardo Sciascia#Massimiliano Maria Kolbe#Robert Littell#Stephen Hawking#Wilkie Collins

0 notes

Text

“The true task of philosophy is thus to develop the determinations which common understanding grasps only as abstractions, in their fixity and their isolation, and to discover in them what gives them life: absolute opposition, that is contradiction.”

-Jean Hyppolite, Genesis and Structure of Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

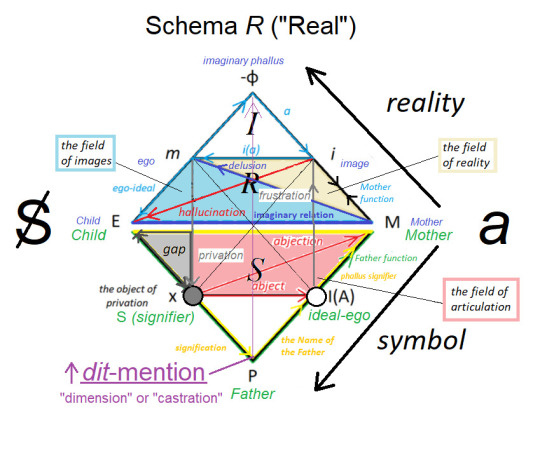

On the Interpretation of an Annotated Version of Lacan's Schema R

The Lozenge of the Mathème for Fantasy (1):

The Vel in the Lozenge

The diamond-shaped lozenge character/symbol found in Lacan's mathème for fantasy is clearly not the same thing as schema R or a semiosic square. This is partially because the lozenge's characteristic ability is to elide participating in either a symbolization or a semiosic square, because these are structures that intrinsically incorporate an arrangement of four given terms into two distinct contraries. The lozenge, on the other hand, while it does possess for itself two contraries, just like a semiosic square has, it also only (apparently) supports two terms, not four. So, while the ultimate agenda is to integrate the Oedipal+preOedipal+Real (S+I+R) quadrangle (schema R) into what Lacan refers to as the vel in his eleventh seminar, they are not genuinely the same structure. The annotations would have the vel moving from E to M on schema R by way of the object of privation x, the symbolic father P, and the ideal-ego I(A). This is not what is going on with a lozenge at all. So, there is either a dialectical progression required to reach the point where a lozenge-structure can modify the schema R so that a direct vel movement is possible whenever signification may occur, or these speculations and suspicions turn out to be incorrect, and the lozenge-structure should be kept separate from any quadrangular semiosic schemas for the rest of human history.

In any case, here is the (my) annotated version:

The Lozenge of the Mathème for Fantasy (2):

The Hegelian Lure, and the “Master-Servant Dialectic” in the Oedipal Square/Schema R

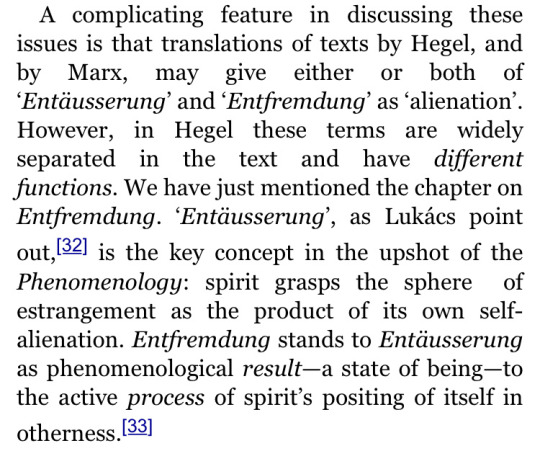

In an article titled “Hegel’s Master-Slave Dialectic and a Myth of Marxology”, written by Chris Arthur, and published in the New Left Review for their November-December 1983 issue (this is an article that I read online a few years ago that profoundly influenced me), there was a discussion on the appropriation of Hegel's philosophy by both Karl Marx himself versus the French Marxists of the 20th century, the latter citing Alexandre Kojève as their primary influence: figures such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Jean Hyppolite, and Hérbert Marcuse.

At stake was the definition and use of the French word aliénation in French Marxist philosophy, since it could be translated for two different words in German, words which were used by the philosophers Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Karl Marx. These two words were, namely, Entäußerung (“en-toy-sare-oong”, alienation) and Entfremdung (“ent-frem-doong”; estrangement, or alienation), respectively.

Hegel's Entäusserung was used more in reference to a spiritual (pertaining to Spirit) or essential (pertaining to essence) connotation of the meaning of the word "alienation", whereas the word Entfremdung connoted through "estrangement”, for Marx more specifically, something maybe closer to the English word "separation", i.e., the proletariat's alienation from the product of his/her/their labor, indicating that the worker has the product of his labor taken away from him once he is finished making it. This is because it is intended, by the capitalist who owns the business, to be sold to someone else (obviously). Marx's point in developing this idea of alienation wasn't exactly that the finished product ought to belong to the worker instead (as I once foolishly misunderstood to a large degree), but rather that the financial math involved in capitalist business operations ends up cheating the worker of a full compensation for what he/she/they did to produce wealth for their employer that day. Alienation, in Marxian economics, thereby implemented a more spiritual or abstract register of Hegel's philosophy in this manner, which it always only ever was; mostly, this was in the context of Marx's polemic against a sort of poetic injustice at the societal level, and not a serious call for any violent destruction of the established order.

But wait… Is Marx ever really talking about political economy itself when he writes about the workers who are forced to participate in it, (that is, if they want food to eat and a place to sleep)? Was his writing just an example of literary self-stylization through polemic? Or is labor itself not truly productive, but rather something fundamentally cognitive and philosophical by means of the historical mechanisms internal to thought itself? And why is it important that French intellectuals of the 20th century were claiming that these connections now established between Marx and Hegel ought to be attributed to the teachings of Alexandre Kojève, instead of getting de-bunked altogether?

This tendency in French Marxism, broadly speaking, and according to Chris Arthur, is significant because Alexandre Kojève is practically the father of French existentialism, French psychoanalysis, French political philosophy, and 20th century French Marxism; the study of any philosophy of history or Heidegger's ontology in France, as well, could never do without his influence either. As a result, even French president Emmanuel Macron can be presumed to have a familiarity with the prestige of the French Hegelian tradition. Alexandre Kojève was a profound influence on Jacques Lacan as well, serving as Lacan's "master-signifier". He really is the most influential thinker, teacher, and politician of all time, even though he is not by any means the most essential one.

However, this confusion about so-called "alienation" persisted in Western European philosophy for quite a long time as a result of his teaching. But… what if Kojève had anticipated, prior to the consequences of this confusion about "alienation", what he was doing with the eventual historical effects of his teaching? His calculated dissemination of Hegel’s and Marx’s philosophical wisdom is rather Christ-like for that reason. (But I'll discuss this way further down in the post.)

Back to main topic: The vel in Jacques Lacan's diamond-shaped lozenge is located at the bottom-half of the lozenge. This part of it, a V-shaped movement from left to right, is also referred to by Lacan as "the Hegelian lure". Why?

So, the Hegelian lure is… what?

“Spirit grasps the sphere of estrangement as the product of its own self-alienation.” This is the essential thrust of fantasy in general, even though it is an activity that remains largely unconscious. And that very fact is because of its interactions with what is non-conscious.

This interplay which constitutes the thrust of fantasy is between:

[1] the formations of the unconscious,

[2] unconscious mechanisms (e.g. natural metaphor), and

[3] non-conscious, or undiscovered, scientific/factual knowledge.

This thrust of fantasy, then, is a conglomerate formation facing towards Hegel's idea of Absolute Knowing. There is a gap between the present-day, or present-moment, and the final end of knowledge itself, which marks the location of a present-moment's abstract finish-line. This situation bears stark similarities to Kant's antinomies of Pure Reason, but as Hegel famously criticizes, Kant's idea of the concept is too flimsy, because a concept is something which ought to be grasped properly if it is to be the attainment of the thing itself. In this vein, what I personally like to think of as the noumenal justice of imaginational (visual) logic relies too heavily on the metaphysical escapability of the Kantian thing-in-itself. This innate slipperiness, which generally characterizes Kant's understanding of objects, avoids Hegel's notion of Absolute Knowing for the most part, deferring instead to its respectively absent uncaused cause, rather than making itself graspable by way of self-knowing.

The relationship to knowledge on the part of the Lacanian (or psychoanalytic) subject is one which must necessarily pass through the dialectics of need, demand, and desire in order to be capable of "producing" a signifying chain. This is distinctly marked by the appearance of a', which shows up on the Schema L. (You can find a pretty good explanation of that here, although I would like to take a closer look at it and emphasize the emergence of this a' as the very condition to which desire itself is subjected.)

In any case, this conception of "desire itself" as something subjected to the a' is analogous to a thematic element of the mathème for fantasy found in Chris Arthur's exposition of the philosophical relationship between Marx and Hegel. So, what does Marx say, potentially pertaining to fantasy, and alluding to Hegel, according to Chris Arthur?

(“Bildungsroman”, according to Oxford Languages/Google Search Engine, is “a novel dealing with one person's formative years or spiritual education.”)

“Abstract mental labor” as the “labor of spirit” is the final objective of fantasy in general, and this is what Lacan's mathème expresses. On the annotated version of Schema R, however, there is a part of the vel (if this schema is indeed mimicking the lozenge) which is a gap in both figurative and literal space, there to denote how the dialectic of desire must play out before a linear process of signification may ever occur in the first place. To get to this abstract mental labor, then, reality must become an object, one which is both ordered and organized by the trapezoid-symbolizations which are the projective surfaces of psychoses: poiesis/delusion, genesis/hallucination, and sinthome/elision. This is what the convoluted-looking annotation basically signifies.

The Lozenge of the Mathème for Fantasy (3):

The Gap between the Split-Subject and the Object of Privation

The split-subject is produced by a variable stimulus Δ interacting with the variables S and S’, illustrated above on Graph I of the graph of desire, which is also known as the “button-tie” or “quilting-point” (point de capiton). This interaction between the variables is called metonymic sliding (glissement), or slippage. Two vertices of the pre-Oedipal triangle (i and m) may then interact with this metonymic slippage in tandem with its already-produced product, the split-subject, $. To re-iterate the basics, the Other, A, is a destination at which the subject never arrives, however (it is a place that exists, but not a space where one may be). Rather, the approach is one of anticipation for what Lacan repeatedly called “the treasure trove of signifiers”, the Other, which I mistook (for a long time) for a lexicon. Looking at the schema for poiesis will show, however, that there is also the sonic resonance of the imaginary phallus, -φ, which vibrates all around the image of the object i(a), objet petit a.

Poiesis here is the failure of frustration to relate to castration in a way that germinates the very possibility of fantasy. The subject’s approach to a relationship with demand is knocked off course by a metonymic slippage which flees from the Other in the form of the Voice, and this consequent alienation causes the subject to “fall under” the phallic function of the mother's beyond (Jouissance → Castration) and land at the locus of the signified of the Other. It does not reach the upper level of the complete graph of desire because it was not launched up by desire, d, with enough thrust. This is Hegel and Marx’s Entfremdung, which was described above. The estrangement of spirit finds its home in self-alienation, and picks up the Signifier as the substitution for its lost relationship to desire. This is a properly-constituted instance of cognition, which in addition to the signified also picks up more of -φ’s sonic resonances on the way down to I(A), and arms itself with the ego (m, “le moi”). The ideal-ego, I(A), is a space where one may arrive at occasionally, but the resonances of the imaginary phallus which are functionally reflected (reflection here functions as a metaphor for re-semiotization, since the vectors $→A and s(A)→I(A) are not moving in the same direction) in i(a) continuously interfere with the apperception of any final tension. This is to say that the graph of desire is best understood as a structure that is constantly pulsing with the colorful, multiplicitous vibrations of plucked strings.

Poiesis corresponds to the elementary cell, Graph II of the graph of desire, as a projective surface of psychosis, the one which fosters the (psychotic) structure of delusion. It is something that you peel off of it, like a sticker, or an article of clothing, a cloak for a desire-device whose existence would have otherwise gone undetected. But what it also uncovered for us above was the falling-under of the subject to a place below the phallic function at the signified of the Other s(A), which is a place both added to and subtracted from by the sonic resonances of the imaginary phallus in an Icarus-like enactment of Entfremdung.

What emerges for the subject from this falling-under, in conjunction with both poietic uncovering and Entfremdung, is the object of privation, which I denote as x. This kind of object is of a symbolic lack. But this observation of the poietic uncovering of a desire-device (Graph II of the graph of desire) as the foundation for the approach to phenomenological method is both schematically and architectonically deceptive. However, The relationship between the subject and the object of privation is certainly an exceptional one, and poiesis may approach this object from the greatest distance possible, as a trapezoidal-symbolization, and as a projective surface without a symbolic object. The aforementioned deception of this approach lies in how the other two trapezoidal-symbolizations have identical capacities to uncover similar dimensional objects for the subject (i.e., objects of frustration and castration), therefore, they are neither objectively nor metaphysically outranked by the primal cloak of poiesis.

Beginning with poiesis makes the exposition of the gap between $ and x less difficult to explain, though. This is because for the cloak, or projective surface, of sinthome, the object of privation moves right into the place of the signified of the Other once the dialectic of demand has recapitulated, whereat the subject may readily collect it (x) upon the occurrence of its Entfremdung after having fallen under the phallic function; the subject then may bring it (x) back to where it formerly just was, to the space of the ideal-ego.

This process of re-linking the signified of the Other to the ideal-ego without interference from the resonances of the imaginary phallus by means of the object of privation is called the abject. Counter-resonances from the symbolic father at P on the Oedipal square vibrate in tandem with the momentum of the ego (m), causing elisions of the resonances of the imaginary phallus by de-longitudinalizing its sound waves, sending them off in a transverse direction. If sound waves are always physically longitudinal, and this fact is in tandem with the imaginary phallus because these waves may only follow the law, then the sound waves which resonate from P are longitudinal as well, because they may only stop the law from being followed. The relationship between P and m is an odd one that can therefore only be uncovered by putting on the cloak of sinthome. The unconscious mechanism at work in this cloak of sinthome placed over Graph II is reification. The subject may get sucked over to the left side of the graph by the resonances of P in tandem with m, and identify directly with x in such a way that the ideal-ego and the subject take on a relationship to one another similar to that of the abject. This close-knit triangulation leaves the Other in a state of being held at the greatest possible distance, however; this is to the extent that the real father must have some rugged object for its substitute within the treasure-trove of signifiers (A). In this way, as a distracting ploy to the subject, it is also the key to the lock, which allows for the object of privation to invade the subject’s rightful place.

The final cloak, then, is the cloak of genesis, whereby the subject substitutes itself for the object of privation directly in order to displace itself, and pre-configures the left side of Graph II as wholly imaginary. Thereby, the subject may be returned to the Father most purely at I(A), and the signified may also be returned rightfully to the treasure-trove of the Other at A, both of these functions occurring mutually without disturbing one another. This is also the foundation for the projective surface of hallucination, however, a sort of antagonistic undoing of the phenomenology that the cloaks, up until now, gave a semblance of.

In conclusion, the gap (béance) between the split-subject and the object of privation is a three-sided relationship between two terms: E-x, E’-x, and $-x. This is illustrated by the button-tie, Graph I, and results in the formation of a lozenge-structure. You can also find it on the symbolic (lower) triangle of the annotated schema R, adjacent to E. Thus, the lozenge is derived from a semiosic square, that of schema R, after all, rather than the synchrony and diachrony at odds with one another which merely form a semblance of the real through their empty resonance. (Whether or not this is ontological or metaphysical is decidedly beyond the scope of the topic.)

Alexandre Kojève and Jacques Lacan's Christ-Like Riddle for Human History

So: back to the speculation about Alexandre Kojève, and his Christ-like plan for the fate of our species’ philosophical institutions: did he intentionally plant seeds which might give the answer to the Lacanian problematic of the “Hegelian lure”, and furthermore in advance of the completion of the psychoanalytic sphere (in 20th century France)? The labor which is grasped as the “essence of man” that Marx alluded to, and which Kojève emphasized in his lecture, is clearly a philosophical labor, and not a materially productive labor. This kind of labor is ultimately far more time-consuming, and the relation of the mathème for fantasy to schema R is one of philosophical (maybe Kantian?) transcendence. The mathème itself represents what our human species may finally aspire to, if it finds the capacity, the excellence, and the strength to do so. And this process is fundamentally historical, by a (Kantian) form of necessity.

The Christ-like riddle for human history mentioned earlier, then, is about the ambiguity and the eternal struggle happening between [a.] the master-signifier, S1 and [b.] the Name(s) of the Father, S(A), both of which serve a master's discourse, and function to prohibit the mother as a fundamental consequence of language-acquisition (schema L). What is so Christ-like about it is that this dual antagonism appears to have been left behind by the two men, Kojève and Lacan, very intentionally. Even though Chris Arthur seemingly criticizes the French intellectuals in his article, those who make false claims because they are too broad about the link between Marx and Hegel according to Kojève, Arthur doesn't seem completely indignant about it if he is also undoubtedly aware of Lacanian psychoanalysis. He expertly enacts the cyclical process of the rotations of the four discourses in a way that doesn't escape one's attention. He is a very cerebral and witty guy, in this regard.

— (5/10/2022)

#lacanian psychoanalysis#drawings#philosophy#philosphy of history#politics#french hegelianism#Emmanuel Macron#French philosophy#Karl Marx#Hegel#Jacques Lacan#alexandre kojeve

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Georges Bataille

DISCUSSION SUR LE PÉCHÉ

Présentation de Michel Surya

Texte intégral de la conférence prononcée le 5 mars 1944 par Georges Bataille, et de la célèbre « discussion » qui a suivi. Étaient notamment présents, à l’invitation de Marcel Moré : Arthur Adamov, Maurice Blanchot, Pierre Burgelin, Simone de Beauvoir, Albert Camus, Jean Daniélou, Dominique Dubarle, Maurice de Gandillac, Jean Hyppolite, Pierre Klossowski, Michel Leiris, Jacques Madaule, Gabriel Marcel, Louis Massignon, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Jean Paulhan, Pierre Prévost, Jean-Paul Sartre...

(via Bataille Georges | MOTS LIÉS)

#georges bataille#michel surya#pierre klossowski#maurice blanchot#michel leiris#discussion sur le péché#1944

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Crisis and Critique

What is critical theory, and whence the notion of critique as a practical stance towards the world? Using these questions as a point of departure, this course takes critical theory as its field of inquiry. Part of the course will be devoted to investigating what critique is, starting with the etymological and conceptual affinity it shares with crisis: since the Enlightenment, so one line of argument goes, all grounds for knowledge are subject to criticism, which is understood to generate a sense of escalating historical crisis culminating in a radical renewal of the intellectual and social order. We will explore the efficacy of modern critical thought, and the concept of critique’s efficacy, by examining a series of attempts to narrate and amplify states of crisis – and correspondingly transform key concepts such as self, will, time, and world – in order to provoke a transformation of society. The other part of the course will be oriented towards understanding current critical movements as part of the Enlightenment legacy of critique, and therefore as studies in the practical implications of critical readings. Key positions in critical discourse will be discussed with reference to the socio-political conditions of their formation and in the context of their provenance in the history of philosophy, literature, and cultural theory. Required readings will include works by Kant, Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche, Freud, Husserl, Benjamin and others, with suggested readings and references drawn from a variety of source materials ranging from literary and philosophical texts to visual images, film, and architecture. You are invited to work on your individual interests with respect to the readings.

Week 1

Critique, krinein, crisis (Koselleck, Adorno)

Required Reading

Reinhart Koselleck, “Crisis,” Journal of the History of Ideas 67.2 (2006), 357-400.

—, Chapters 7 and 8, Critique and Crisis: Enlightenment and the Pathogenesis of Modern Society. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1988 [German original, 1959].

Adorno and Horkheimer, "The Concept of Enlightenment," in Dialectic of Enlightenment, trans. John Cumming (New York: Continuum, 1989), pp. 3-42.

Recommended Reading

Michel Foucault, “What is Enlightenment?” in The Foucault Reader. New York: Pantheon Books, 1984: 32-50.

—, The Politics of Truth. New York: Semiotext(e), 1997.

Friedrich Hölderlin, “Nature and Art or Saturn and Jupiter,” in Hyperion and Selected Poems. Ed. by Eric Santner. Translated by Michael Hamburger. New York: Continuum, 1990: 150-151.

Week 2

Judgment and Imagination (Kant)

Required Reading

Immanuel Kant, “Preface [A and B],” in Critique of Pure Reason. Translated and edited by Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998: 99-124.

—, “Preface” and “Introduction,” in Critique of Practical Reason, in Practical Philosophy, trans. Mary Gregor (Cambridge UP, 1996), pp. 139-149.

—, §§1-5, 59-60 of Critique of the Power of Judgment, trans. Paul Guyer and Eric Matthews (Cambridge UP, 2000), pp. 89-96, 225-230.

—, “Idea for a Universal History with a Cosmopolitan Purpose,” in Kant: Political Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991 (2nd ed.): 41-53, 273.

—, “An Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment? [1784],” in Practical Philosophy. Translated by Mary J. Gregor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999: 11-22.

Recommended Reading

Immanuel Kant, "Analytic of the Sublime," in Critique of Judgment. Translated by James Creed Meredith; revised, edited, and introduced by Nicholas Walker. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007: 75-164.

Theodor Adorno, Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (2001 [1959])

Henry Allison, Kant’s Transcendental Idealism (2004)

Hannah Arendt, Lectures on Kant’s Political Philosophy (1992)

Geoffrey Bennington, “Kant’s Open Secret”, Theory, Culture and Society 28.7-8(2011): 26-40.

J.M. Bernstein, The Fate of Art: Aesthetic Alienation from Kant to Derrida and Adorno (1992)

Graham Bird, The Revolutionary Kant (2006)

Andrew Bowie, Aesthetics and Subjectivity: from Kant to Nietzsche (1990, 2003)

Howard Caygill, The Kant Dictionary (2000)

Ernst Cassirer, Kant's Life and Thought (1981)

Gilles Deleuze, Kant's Critical Philosophy (1984)

Will Dudley and Kristina Engelhard (eds.) Immanuel Kant: Key Concepts (2010)

Paul Guyer, Kant’s Critique of the Power of Judgment: Critical Essays (2003)

Martin Heidegger, Phenomenological Interpretation of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (1997)

Laura Hengehold, The BODY Problematic: Political Imagination in Kant and Foucault (2007)

Otfried Höffe, Immanuel Kant (1994)

Jean-François Lyotard, L’Enthousiasme: La critique kantienne de l’histoire. Paris: L’Éditions Galilée, 1986.

Rudolf Makkreel, Imagination and Interpretation in Kant: The Hermaneutic Import of the Critique of Judgment (1990)

Jean-Luc Nancy, A Finite Thinking (2003)

Andrea Rehberg and Rachel Jones (eds.), The Matter of Critique: Readings in Kant’s Philosophy (2000)

Philip Rothfield (ed.), Kant after Derrida (2003)

Rei Terada, Looking Away: Phenomenality and Dissatisfaction, Kant to Adorno (2009)

Yirmiahu Yovel, Kant and the Philosophy of History (1989)

Week 3

Recognition and the Other (Hegel)

Required Reading

G.W.F. Hegel, “The Truth of Self-Certainty” and “Lordship and Bondage,” in The Phenomenology of Spirit. Translated by Terry Pinkard. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2018: 102-116.

—, “The Art-Religion,” in The Phenomenology of Spirit. Translated by Terry Pinkard. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2018: 403-430.

Recommended Reading

G.W.F. Hegel, Introduction [§§1, 2, 3, 5, 6 and 8], in Aesthetics: Lectures on Fine Art. Translated by T.M. Knox. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975: 1-14; 22-55; 69-90.

Stuart Barnett (ed.), Hegel after Derrida (2001)

Frederick Beiser (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Hegel (1993)

Susan Buck-Morss, Hegel, Haiti, and Universal History (2009)

Rebecca Comay, Mourning Sickness: Hegel and the French Revolution (2011)

Rebecca Comay and John McCumber (eds.), Endings: Questions of Memory in Hegel and Heidegger (1999)

Eva Geulen, The End of Art: Readings in a Rumor after Hegel. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2006.

Werner Hamacher, “(The End of Art with the Mask),” in Stuart Barnett (ed.), Hegel after Derrida. London and New York: Routledge, 1998: 105-130.

Werner Hamacher, “The Reader’s Supper: A Piece of Hegel,” trans. Timothy Bahti, diacritics 11.2 (1981): 52-67.

H.S. Harris, Hegel: Phenomenology and System (1995)

Stephen Houlgate, An Introduction to Hegel: Freedom, Truth and History (2005)

Stephen Houlgate, Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit (2013)

Fredric Jameson, The Hegel Variations (2010)

Alexandre Kojève, Introduction to the Reading of Hegel. Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1980.

Terry Pinkard, Hegel: A Biography (2001)

Week 4

Revolution … (Marx)

Required Reading

Karl Marx, “I: Feuerbach,” The German Ideology, in Collected Works vol. 5. London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1976: 27-93.

Karl Marx, "Theses on Feuerbach," available online (http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/theses/theses.htm)

Week 5

... and Repetition (Marx)

Required Reading

Karl Marx, “Preface” to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy [1859], in Collected Works vol. 29. London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1976: 261-165.

—, “Postface to the Second Edition” and “Chapter 1: The Commodity,” in Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Trans. by B. Fowkes. London: Penguin, 1990: 95-103 and 125-177.

Recommended Reading

Louis Althusser, For Marx (1969)

Hannah Arendt, “Karl Marx and the Tradition of Western Political Thought”, Social Research 69.2 (2002): 273-319.

Étienne Balibar, The Philosophy of Marx (1995, 2007)

Ernst Bloch, On Karl Marx (1971)

Andrew Chitty and Martin McIvor (eds.), Karl Marx and Contemporary Philosophy (2009)

Simon Choat, Marx Through Post-Structuralism: Lyotard, Derrida, Foucault, Deleuze (2010)

Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International. New York and London: Routledge, 1994.

Werner Hamacher, “Lingua Amissa: The Messianism of Commodity-Language and Derrida’s Specters of Marx” (1999)

Jean Hyppolite, Studies on Marx and Hegel (1969)

Sarah Kofman, Camera Obscura: Of Ideology (1998)

Peter Singer, Marx: A Very Short Introduction (1980)

Michael Sprinker (ed.), Ghostly Demarcations: A Symposium on Jacques Derrida’s Specters of Marx (1999, 2008)

Moishe Postone, History and Heteronomy: Critical Essays (2009)

Moishe Postone, Time, Labor, and Social Domination: A Reinterpretation of Marx’s Critical Theory (1993)

Jacques Rancière, “The Concept of ‘Critique’ and the ‘Critique of Political Economy’ (from the 1844 Manuscript to Capital)”, Economy and Society 5.3 (1976): 352-376.

Tom Rockmore, Marx After Marxism: The Philosophy of Karl Marx (2002)

Gareth Stedman-Jones, Karl Marx: Greatness and Illusion (2016)

Week 6

Tutorial Week

Week 7

Will to Becoming Otherwise (Nietzsche)

Required Reading

Friedrich Nietzsche, "Preface" and "First Treatise," in On the Genealogy of Morality. Trans. by Maudemarie Clark and Alan J. Swensen. Indianopolis/Cambridge: Hackett, 1998: 1-33.

Week 8

Ascetic Ideal and Eternal Return (Nietzsche)

Required Reading

Friedrich Nietzsche, "Second Treatise" and "Third Treatise," in On the Genealogy of Morality. Trans. by Maudemarie Clark and Alan J. Swensen. Indianopolis/Cambridge: Hackett, 1998: 35-118.

Recommended Reading

Friedrich Nietzsche, §§341-342 of The Gay Science

Friedrich Nietzsche, “On Vision and Riddle” and “The Convalescent,” in Thus Spake Zarathustra III

Friedrich Nietzsche, “On Truth and Lying in a Non-Moral Sense,” in: The Birth of Tragedy and other writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Friedrich Nietzsche, “On the Uses and Abuses of History for Life,” in: Untimely Meditations. Trans. by R.J. Hollingdale. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

Gilles Deleuze, Nietzsche and Philosophy. New York: Columbia University Press, 2006.

Jacques Derrida, Spurs: Nietzsche’s Styles. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1979.

Michel Foucault, "Nietzsche, Genealogy, History," in Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews. Ed. by D. F. Bouchard. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977: 139-164.

R. Kevin Hill, Nietzsche’s Critiques: The Kantian Foundations of his Thought (2003)

Luce Irigaray, Marine Lover of Friedrich Nietzsche. Trans. by Gillian C. Gill. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991.

Jean-Francois Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Trans. by Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984.

Gianni Vattimo, The End of Modernity: Nihilism and Hermeneutics in Postmodern Culture. Trans. by Jon R. Snyder. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988.

Alenka Zupančič, The Shortest Shadow: Nietzsche’s Philosophy of the Two (2003)

Week 9

Repetition Compulsion (Freud)

Required Reading

Sigmund Freud, “Beyond the Pleasure Principle” [excerpts], in Peter Gay (ed.), The Freud Reader. London: Vintage, 1995: 594-625.

Recommended Reading

Theodor Adorno, “Revisionist Psychoanalysis,” Philosophy and Social Criticism 40.3 (2014): 326-338.

Louis Althusser, Writings on Psychoanalysis: Freud and Lacan (1996)

Lauren Berlant, Desire/Love (2012)

Leo Bersani, The Freudian Body: Psychoanalysis and Art (1986)

Rebecca Comay, “Resistance and Repetition: Freud and Hegel,” Research in Phenomenology 45 (2015): 237-266.

Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression (1995)

Jacques Derrida, The Post Card: From Socrates to Freud and Beyond (1987)

Mladen Dolar, “Freud and the Political,” Unbound 4.15 (2008): 15-29.

Sarah Kofman, Freud and Fiction (1991)

Jacques Lacan, “The Agency of the Letter in the Unconscious; or Reason after Freud”, in Écrits: A Selection. Trans. by A. Sheridan. New York: Norton, 1977: 146-175.

Catherine Malabou, “Plasticity and Elasticity in Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle.” Diacritics 37.4 (2007): 78-85.

Jean-Luc Nancy, "System of (Kantian) Pleasure (With a Freudian Postscript)," in Kant after Derrida. Ed. by Phil Rothfield. Manchester: Clinamen Press, 2003: 127-141.

Angus Nicholls and Martin Liebscher (eds.), Thinking the Unconscious: Nineteenth-Century German Thought (2010)

Charles Sheperdson, Vital Signs: Nature, Culture, Psychoanalysis (2000)

Samuel Weber, The Legend of Freud. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000.

Alenka Zupančič, Ethics of the Real: Kant and Lacan. London: Verso, 2012 [reprint].

Week 10

Crisis of European Humankind (Husserl)

Required Reading

Edmund Husserl, §§1-7 and §§10-21, The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology. Trans. by David Carr. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1970: 2-18; 60-84.

Recommended Reading

Edmund Husserl, “Philosophy and the Crisis of European Humanity [Vienna Lecture],” in The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology. Trans. by David Carr. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1970: 269-299.

Jacques Derrida, The Other Heading: Reflections on Today’s Europe. Trans. by Pascale Anne Brault and Michael B. Naas. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992: 4-83.

Paul de Man, “Criticism and Crisis,” in Blindness and Insight: Essays in the Rhetoric of Contemporary Criticism. New York: Oxford University Press, 1971: 3-19.

James Dodd, Crisis and Reflection: An Essay on Husserl’s Crisis of the European Sciences (2004)

Burt C. Hopkins, The Philosophy of Husserl (2011)

David Hyder and Hans-Jörg Rheinberger, Science and the Life-World: Essays on Husserl’s Crisis of European Sciences (2010)

Leonard Lawlor, Derrida and Husserl: The Basic Problem of Phenomenology (2002)

Dermot Moran, The Husserl Dictionary (2012)

Paul Valéry, "Notes on the Greatness and Decline of Europe” and “The European,” in History and Politics. Trans. Denise Folliot and Jackson Matthews. New York: Bollingen, 1962: 228; 311-12.

David Woodruff Smith, Husserl (2007)

Barry Smith and David Woodruff Smith (eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Husserl (1995)

Week 11

Crisis-Proof Experience (Benjamin)

Required Reading

Walter Benjamin, “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire,” in Selected Writings vol. 4. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2003: 313-355.

Recommended Reading

Walter Benjamin, "Experience and Poverty"

—, "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproducibility”

—, “Theses on the Concept of History”

—, “Epistemo-Critical Prologue,” in The Origin of German Tragic Drama. Trans. by John Osborne. London and New York: Verso, 2003: 27-56.

—, “Convolute J,” The Arcades Project

—, The Writer of Modern Life: Essays on Charles Baudelaire (2006)

Benjamin and Theodor Adorno, “Exchange with Theodor W. Adorno on ‘The Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire,” in Benjamin, Selected Writings vol. 4 (1999).

Charles Baudelaire, The Flowers of Evil; The Painter of Modern Life

Ian Balfour, “Reversal, Quotation (Benjamin’s History)”, Modern Language Notes 106.3 (1991): 622-647.

Eduardo Cadava, Words of Light: Theses on the Photography of History (1997)

Tom Gunning, “The Exterior as Intérieur: Benjamin’s Optical Detective,” boundary 2 30.1 (2003).

Werner Hamacher, “Now: Benjamin on Historical Time” (2001; 2005)

General Background

Julian Wolfreys (ed.), Modern European Criticism and Theory: A Critical Guide (2006) Simon Critchley, Continental Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction (2001) Terry Pinkard, German Philosophy 1760-1860: The Legacy of Idealism (2002)

Andrew Bowie, Introduction to German Philosophy: From Kant to Habermas (2003)

Kai Hammermeister, The German Aesthetic Tradition (2002) Gary Gutting, French Philosophy in the Twentieth Century (2001)

Eric Matthews, Twentieth-Century French Philosophy (1996)

Jonathan Simons (ed.), From Kant to Lévi-Strauss: The Background to Contemporary Critical Theory (2002)

Learning Outcomes

- You will have a grasp of the broad trends in the development of critical theory.

- You will have a good understanding of how different modern philosophical traditions from German Idealism to Phenomenology inform the different strains of critical theory.

- You will be able to expound and analyse the ways in which a range of different writers and tendencies in the history of modern thought conceive of the specificity of critique.

- You will have a sound grasp of the primary and secondary literatures in critical theory, both on general issues and specific thinkers or schools.

- You will be able to use the ideas and texts explored in the module to inform your readings in critical theoretical texts.

Assessment Criteria

- Students should show a clear command of how their chosen thinker(s) and texts relate to the broader trajectories of critical theory.

- Students should show a detailed critical knowledge of at least two of the module’s key thinkers or theoretical tendencies.

- Students should show a knowledge and capacity to use a good range of secondary literature on both general issues in the field and on the specific thinkers and texts they address.

- Students should be able to read the relevant texts from both critical and genealogical perspectives.

- Students should demonstrate their capacity to develop a distinctive and coherent interpretative and analytical perspective on their chosen subject.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Telegram from Jean Paul Sartre, and letters from Jean Hyppolite and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, to Georg Lukács, 1964-1967.

#Marxism#Lukács#Sartre#Merleau-Ponty#Hyppolite#philosophy#existentialism#humanism#phenomenology#socialism#communism

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Penser à la lettre près : entretien avec Michèle Cohen-Halimi, par Pierre Parlant

Envisager la pensée politique de Nietzsche peut engendrer une certaine perplexité tant elle s’avère complexe et non exempte d’apparentes contradictions. Si bien qu’on se demande si ce projet a un quelconque sens. Dans une lettre à son ami Rohde en octobre 1868, le philosophe ne se déclarait-il pas lui-même étranger à la définition d’« animal politique », ajoutant dans la foulée avoir « contre ce genre de choses une nature de porc-épic » ? D’où cette conviction, devenue lieu commun, d’un apolitisme radical chez un penseur dont on sait combien les institutions politiques, celle de l’État en premier lieu, firent l’objet de sa part d’une critique sans appel.

En reposant la question de la politique à partir de l’examen de la pensée du jeune Nietzsche, c’est-à-dire aussi bien du philologue qu’il n’aura jamais cessé d’être, la philosophe Michèle Cohen-Halimi déplace de façon salutaire les données du problème et leur redonne une profondeur et une richesse remarquables. Si la politique a bel et bien une importance pour le Nietzsche attentif à l’histoire des Grecs tragiques, c’est, montre-t-elle ici, en vertu du nouage qu’il sut voir entre la conflictualité féconde impliquant l’État, la religion, la culture, et une « nouvelle pensée du temps ». Un nouage que devait envelopper un mouvement dialectique d’une allure inédite.

Pareille perspective permet d’ores et déjà d’échapper à l’alternative sclérosante qui, d’un côté, tient l’État pour une donnée nécessaire, et, de l’autre, croit devoir militer pour sa destruction. Mais elle invite de surcroît à penser cette affaire politique de façon dynamique, libérée du diktat de l’actuel, de la croyance au révolu comme aux chimères de l’espérance, histoire de restituer au présent toute sa charge immémoriale.

Que la pensée du jeune Nietzsche puisse nous affranchir d’une conception chrétienne du temps, qu’elle fasse droit à la turbulence comme à l’anachronisme en substituant à la fiction de l’horizon temporel la narration alerte des sauts événementiels, tels sont quelques-uns des enjeux de ce superbe essai de Michèle Cohen-Halimi. Car ici, écrit-elle, « il s’agit de ne pas figer la diachronie mais de dé-linéariser la ligne du temps : nuage atomique, pluie de points temporels, brume, le temps agit. La discursivité de cette pensée est stochastique, interminable, elle change d’organon et de module, traduit, trahit ce qui a déjà été dit : actio in distans ». Où l’on voit que par-delà la question politique c’est le rapport de la pensée avec la vitalité de son propre mouvement qui est alors mis en lumière.

Comprendre la pensée politique du jeune Nietzsche suppose, ainsi que vous l’établissez dès le début de votre livre, d’envisager avec lui une conception nouvelle de la temporalité, affranchie de toute représentation linéaire. S’ensuivent non seulement un rapport inédit au présent comme au passé, mais une appréhension du temps, pensé comme proprement agissant, au sens de ce que Nietzsche appelle actio in distans. Comment peut-on se figurer cette action effective du temps ?

Sans doute deux choses me tenaient-elles à cœur dans l’écriture de ce livre : premièrement, en finir avec les lectures d’un jeune Nietzsche « météorique » qui, surgi de nulle part, tel un « Rimbaud de la philosophie » (je reprends ici une expression utilisée par Clastres à propos de La Boétie), écrit subitement La Naissance de la tragédie (1872) et donne congé à celui qui l’a fait être philosophe, à savoir Schopenhauer ; deuxièmement, déployer dans toutes ses séquences le devenir philosophe de Nietzsche et découvrir comment, depuis un texte de jeunesse décisif, intitulé Fatum et histoire (1862), travaille le projet de délinéariser le temps chrétien.

Délinéariser le temps chrétien signifie à la fois défaire la centration du temps sur le présent ainsi que sur le primat de la conscience, et cesser de reléguer le passé du côté du révolu et l’avenir du côté de l’espérance. Le passé n’est pas trépassé et l’avenir s’élabore dans le rapport (de mémoire/d’oubli) que le présent entretient et renouvelle avec le passé. Il ne s’agit plus de tourner le dos au passé, mais de lui faire face en sachant que, dans la mémoire du temps (laquelle excède les souvenirs de la conscience), c’est-à-dire dans l’inconscient du temps, se joue la puissance de devenir du présent, c’est-à-dire son avenir.

Nietzsche trace de nouvelle manière la « ligne du temps », Zeitlinie comme il l’appelle. Cette ligne hachurée, raturée, est remplie de points-forces qui interagissent à distance — selon le principe de l’actio in distans : ils se repoussent, quand la distance qui les sépare se réduit et s’attirent, quand la distance qui les sépare s’accroît. Nietzsche traduit et transfère dans une atomistique temporelle la thèse du physicien dalmate du XVIIIe siècle Boscovich, qui interprétait la matière comme constituée par les rapports d’attraction et de répulsion de foyers d’énergie discrets, sans étendue, et séparés les uns des autres par des intervalles irréductibles. Il en résulte une interaction mouvante d’atomes temporels énergétiques, plus ou moins éloignés les uns des autres, déployant un champ de forces, tramant un enchevêtrement de retours anachroniques et d’éloignements provisoires. Ce que François Hartog nomme « le régime chrétien d’historicité » est donc défait. C’en est fini de l’horizontalité de la ligne du temps qui signifie la continuité et par conséquent la mesure, mais aussi la correspondance de la succession objective et de la succession causale et par conséquent la narrativité selon l’avant et l’après. La ligne du temps est verticale, elle fond sur nous comme une cataracte énergétique, elle est agitée par le flux et le reflux, elle nous approche du plus lointain et nous éloigne du plus proche, elle progresse par sauts (en arrière, en avant), elle est faite d’anachronismes et de retours intempestifs : la re-naissance des temps passés est devenue pensable. Quand les révolutionnaires de 1830 tiraient sur les horloges, ils ne voulaient pas abolir le temps, ils voulaient un autre temps. C’est donc par l’accès qu’il nous donne à un autre temps fait du retour anachronique de temps inconscients que s’inaugure chez Nietzsche la pensée la plus profonde du changement.

Ayant commencé très jeune par enseigner la philologie à l’université de Bâle, Nietzsche devint un philosophe — « sans enthousiasme », dites-vous — tellement déterminé par cette expérience première qu’elle ne cessa jamais, comme vous le rappelez, de produire ses effets sur son aventure intellectuelle. Quelles ressources et quelles perspectives cette discipline lui offrait-elle ?

La philologie Nietzsche l’a définie comme l’art de bien lire. Une de ses plus belles définitions se trouve dans l’Avant-propos d’Aurore (§ 5) : « La philologie est cet art vénérable qui exige avant tout de son admirateur une chose : se tenir à l’écart, prendre son temps, devenir silencieux, devenir lent, — comme un art, une connaissance d’orfèvre appliquée au mot… » La philologie classique à laquelle Nietzsche est attaché est la discipline-phare de l’Université allemande du XIXe siècle, elle se définit par l’étude des textes de l’Antiquité grecque et latine. Les philologues déchiffrent et traduisent donc des textes dont les langues ne sont plus parlées. Ils sont de manière fondamentale des éditeurs de textes anciens : ils font venir à la lumière des énoncés menacés d’oubli, ils font remonter dans la mémoire et sur la surface de la page des contenus de pensée menacés d’illisibilité et qu’il faut non seulement déchiffrer et traduire mais libérer des falsifications, des distorsions de sens, des erreurs de copistes, des oublis de mots ou de lettres, oublis qui suffisent à perdre la cohérence d’un énoncé. La philologie introduit Nietzsche à l’analyse des conditions de lisibilité des textes et du monde. Elle l’initie au « matérialisme sémantique ». La question de savoir comment on passe d’un mot à un énoncé qui vise une signification est devenue la question philosophique éminente. Nietzsche philosophe-philologue est, à mes yeux, un immense philosophe parce qu’il prend au sérieux la littéralisation de la pensée : Ainsi parlait Zarathoustra est écrit à la voyelle près. J’admire les philosophes qui tiennent que la pensée est à la lettre près. Jean-Pierre Faye est de ceux-là, c’est toute la profondeur de son nietzschéisme à laquelle je rends aussi hommage dans la « Chambre noire 3 » du livre, intitulée « Le philologue et la dépêche d’Ems ».

Suivant l’interprétation qu’en fit Deleuze, on tient souvent Nietzsche pour un adversaire résolu de la dialectique. Or vous montrez que sa connaissance d’Héraclite, sa lecture de Schopenhauer, la fréquentation de Burckhardt et la découverte des travaux du physicien Boscovich l’ont conduit à repenser le temps dans des termes qui impliquent un mouvement dialectique aussi original que décisif sur le plan politique. De quoi s’agit-il ?

Il me semble que la lecture deleuzienne anti-dialectique de Nietzsche doit être réinscrite dans son contexte historique. Dans sa leçon inaugurale prononcée au Collège de France en décembre 1970 et publiée sous le titre L’ordre du discours, Foucault a parfaitement ressaisi ce contexte : « […] toute notre époque, que ce soit par la logique ou par l’épistémologie, que ce soit par Marx ou par Nietzsche, essaie d’échapper à Hegel… » (p. 74) Le parricide qu’accomplit la génération philosophique de Deleuze et de Foucault, mais aussi de Lyotard, pour donner congé aux aînés hégéliens, notamment Kojève, Bataille, mais aussi Jean Wahl, Jean Hyppolite, ne peut pas se transmettre aux générations philosophiques suivantes comme un legs ininterrogé. En outre, les charges anti-dialectiques de Deleuze concernent Hegel. Or, l’histoire de la dialectique est d’une richesse inouïe, on ne saurait la réduire à la dialectique spéculative de Hegel. Le travail d’analyse que j’ai conduit dans Stridence spéculative (Payot, 2014) sur la non-réception française de la Dialectique négative d’Adorno en France dans les années 1980, m’a libérée de cet anti-hégélianisme caractéristique des philosophes français des années 60 et 70 (à l’exception de Derrida). Et ce pas d’écart m’a sans doute permis de revenir à l’histoire profuse de la dialectique qui commence avec Héraclite, dont Nietzsche se veut le continuateur.

De quoi s’agit-il ? S’il est vrai que la dialectique nous confronte à la question de l’ « être autre » et qu’elle est généralement définie comme la mise en contradiction de l’un et du multiple, de l’identité et de la différence, alors la singularité grecque d’Héraclite est double, aux yeux de Nietzsche : Héraclite pense la contradiction non pas de l’un et du multiple, mais de l’un et du deux ; cette contradiction se donne comme ce qui est à vivre, et non pas comme ce qui est à surmonter. Il est donc le penseur éminent du duel qui travaille irréductiblement toute union et toute identité ; il est le penseur de la contradiction sans réconciliation, sans « relève » dit Hegel. Le jeu incessant du deux dans l’un, de la « duplicité » des identités, détermine une dynamique que Nietzsche transfère dans le temps. Boscovich devient l’opérateur d’une re-naissance, d’un retour anachronique, de la dialectique héraclitéenne qui s’entend comme dialectique temporelle. Il est ainsi possible d’énoncer le temps comme des rapports dialectiques de forces et d’énergies, qui peuvent être refoulées ou remobilisées par le présent, mais qui jamais ne cessent d’agir, fût-ce de façon latente.

Si la lecture de Schopenhauer permet à Nietzsche d’envisager la nature et la gravité du « malaise civilisationnel » européen, celle de Burckhardt lui fournit de quoi poser un diagnostic. Selon ce dernier en effet, importe à cet endroit l’examen des rapports qu’entretiennent les « trois grands facteurs d’histoire » que sont l’État, la religion et la Kultur. Dans quelle mesure cette conception a-t-elle pu orienter la pensée politique du jeune Nietzsche ?

Si toute la pensée de Nietzsche s’inaugure dans le projet d’une délinéarisation du temps chrétien et se contracte pour ainsi dire dans la prise de conscience d’un « malaise civilisationnel », lié à la sécularisation inachevée du christianisme, alors il est certain que la rencontre, à Bâle, du jeune philologue avec l’historien Burckhardt est décisive. Burckhardt affirme sa rupture à la fois avec l’histoire positiviste, successive, vectorisée par la chronologie des faits, et avec l’histoire idéaliste ou avec la philosophie de l’histoire (surtout hégélienne), qui perd l’histoire dans la projection d’une fin (progrès, développement de la liberté, etc.). Avec Burckhardt, l’histoire se conçoit comme « doctrine des turbulences » (Sturmlehre) : elle s’écrit à partir du rapport de forces agissantes, latentes ou actuelles, qui produisent des changements lents et souterrains éclatant au grand jour sous forme de crises, toujours inattendues pour la conscience. Ce rapport des forces agissantes, latentes et actuelles, s’organisent autour de trois « facteurs » d’histoire, l’État, la religion et la Kultur. L’État et la religion sont, pour Burckhardt, des facteurs stables tandis que la Kultur est un facteur d’histoire plus mobile et plus plastique à partir duquel peut se concevoir le changement des deux autres. Pour Burckhardt, quand le rapport entre ces trois facteurs d’histoire reste dialectique et que la tension oppositive qui les lie ne cède pas à la captation, à la subsomption d’un facteur par l’autre, la vie sociale qu’ils déterminent ensemble est toujours florissante. Nietzsche comprend ainsi que la politique au sens large peut se penser de nouvelle manière, à partir du rapport dialectique de ces trois facteurs, et surtout par le décentrement de la fonction de l’État, et plus encore par le rôle fondamental que retrouve la Kultur, loin de l’apolitisme et du fameux « désintéressement » qu’on lui associe généralement pour la neutraliser.

L’originalité et la puissance de votre livre tient à la richesse et à la subtilité de vos analyses qui présentent le « jeune Nietzsche politique » comme très tôt requis par le désir de soustraire la pensée à l’aliénation du temps chrétien. Mais frappe presque autant le mode singulier d’exposition que vous mettez en œuvre. Parties et chapitres se distribuent en effet en ménageant ponctuellement une place à ce que vous nommez des « chambres noires », jusqu’à cette conclusion qui reprend, de façon suggestive, un « schéma » d’inspiration « boscovichéenne ». À quoi répond le choix de cette construction et comment sa forme s’est-elle imposée ?

L’écriture de ce livre dont la gestation a été très longue — il relève sans aucun doute de ce que Nietzsche nomme les « grossesses d’éléphant » — m’a confrontée à une expérience de vertige. J’ai eu plusieurs fois le sentiment que j’allais lâcher prise. Je ne parvenais pas à tenir ensemble tous les éléments, tous les événements qui avaient contribué au devenir philosophe de Nietzsche. En effet, ce devenir philosophe était advenu par de multiples effets d’après-coup qui m’imposaient des mouvements d’aller et retour, des va-et-vient entre le premier coup d’un événement, d’une lecture ou d’une rencontre, et son après-coup de réappropriation et parfois de réinvention. Une espèce de tota simul, de « tout en même temps », devait être analytiquement déployé sans que soit écrasée la détente incessante du latent et de l’actuel, l’articulation permanente du coup et de l’après-coup. Voilà pourquoi la structure générale du livre est boscovichéenne : les chapitres les plus éloignés s’attirent et se répondent, les chapitres les plus proches se repoussent en se faisant mutuellement avancer. J’ai donc voulu que l’écriture s’accorde avec une temporalité discontinue, faite d’éléments hétérogènes, d’effraction d’événements, mais aussi d’anachronismes. D’où les chambres noires, qui sont des procédés optiques donnant l’illusion d’un espace à trois dimensions et où mes questions quittent la planéité de la page pour se situer dans une perception plus directe : l’horreur de la guerre de 1870 en tant « précurseur sombre » de certaines séquences du XXe siècle (chambre noire 1), le rapport du dialecticien Adorno à Nietzsche (chambre noire 2), la dépêche d’Ems lue par Nietzsche et Jean-Pierre Faye (chambre noire 3).

Source : Diacritik

https://diacritik.com/2021/04/07/penser-a-la-lettre-pres-entretien-avec-michele-cohen-halimi/

6 notes

·

View notes