#jarrolds books

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Christopher Nicole as Peter Grange - The Golden Goddess - Jarrolds - 1973

#witches#goddesses#occult#vintage#the golden goddess#jarrolds#jarrolds books#christopher nicole#peter grange#goddess#1973#girls with boots

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

BECOMING JANE (2007)

BECOMING JANE (2007)

Becoming Jane is a biographical fiction film directed by Julian Jarrold. The film stars Anne Hathaway as Jane Austen, as well as James McAvoy and Maggie Smith. Actor Ian Richardson appeared in the film before he died the same year the film was released.

The film depicts the early life of author Jane Austen and her love for Thomas Langlois Lefroy. The film is based on the book Becoming Jane Austen by Sarah Williams and Kevin Hood (2003). The writer pieced together some of the known facts about Jane Austen from her books and letters. The film was shot in Ireland, even though Austen lived in Hampshire, England.

youtube

#becomingjane#becomingjane2007#janeausten#becomingjaneausten#annehathaway#JamesMcAvoy

#becoming jane#becomingjane#becoming jane 2007#jane austen#janeausten#become jane austen#anne hathway#james mcavoy#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Anne Hathaway dans "Jane (Becoming Jane)" biopic de Julian Jarrold sur la vie de la romancière Jane Austen (1775-1817), décembre 2022.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Got to go to one of my favourite bookshops today! Jarrolds always has a such good curated collection of popular and unique books!

[ID: bookshelves in a bookstore showing YA novels].

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Marry me,” she whispered.

Relief, joy, and desire rocketed through David’s body as he gazed down at the woman who would be his wife.

“I thought you would never ask,” he breathed.

- Advent with an Archduke by Emily EK Murdoch

#romance wednesday#book quote#advent with an archduke#emily ek murdoch#louisa jarrold#david nelson#historical romance#regency romance#quote#quotes#booklr#bookblr#merry christmas belles and rakehells

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

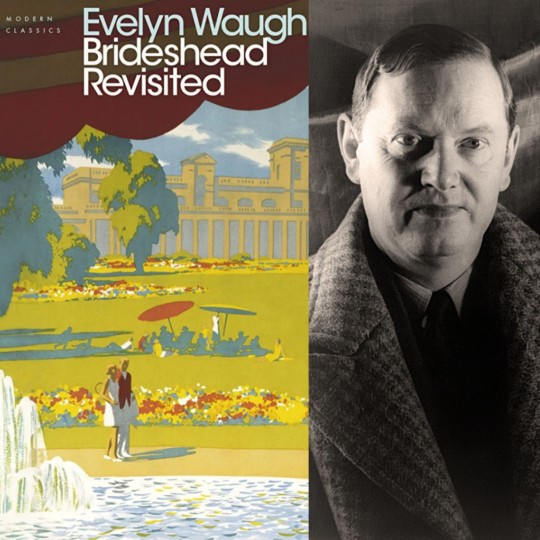

If you 💜 Brideshead, check My Archive for more - I am blogging about the whole film.

I am starting a rewatch of the 2008 movie adaptation of Brideshead Revisited, a 1945 novel by Evelyn Waugh. This is my most loved Matthew Goode film, based on one of my favourite novels, so it is very close to my heart.

I’ll be using the Director’s Cut bluray.

The collage above shows Charles Ryder's journey from young innocence to loss, love found and disillusion.

📷 My edit from Brideshead Revisited (2008)

The cast of Brideshead Revisited (2008) is magnificent and includes, in addition to Matthew Goode (Charles Ryder), Hayley Awell (Julia Flyte), Ben Wishaw (Sebastian Flyte), Emma Thompson (Lady Marchmain) and Michael Gambon (Lord Marchmain). Emma Thompson took the young actors, who really got on well together, under her wings.

📷 My edit from Brideshead Revisited 📀 bonus features

Brideshead Revisited: The Sacred & Profane Memories of Captain Charles Ryder is a 1945 novel by Evelyn Waugh. It follows, from the 1920s to the early 1940s, the life and romances of Charles Ryder, his encounter with the aristocratic Flytes and their beautiful stately home Brideshead and his journey of discovery. It explores themes around nostalgia for the past and English nobility, happiness, love and loss and Catholic faith and guilt.

The novel (and film) start and end with older bittersweet Charles as an officer during the war billetted at Brideshead and reminiscing about the past.

📷 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brideshead_Revisited

Brideshead Revisited was turned into a stupendous 11-part mini-series in 1981 by Granada TV with Jeremey Irons and Anthony Andrews. It is an excellent adaptation which received critical acclaim. A high bar for the cast and crew of the 2008 movie who must have felt the weight of history on their shoulders.

Trailer:

https://youtu.be/_ZtPGYLEzpw

📷 My edit from Brideshead Revisited and IMDB

Brideshead Revisited was directed by Julian Jarrold and cinematography is by Jess Hall (both pictured with Matthew Goode). The screenplay is by Jeremy Brock and Andrew Davies. I think the film is a cinematographic gem and feast for the eyes. It’s a shame it got a lukewarm reception. I think the comparisons with an 11-part miniseries, which had the time to unfold the story, are unfair. The film had to condense quite a lot of the book and made some adaptive choices which may be seen as a departure from the novel but it remains, in my view, true to the spirit of the book and is a very good adaptation in its own right.

📷 My edit from Brideshead Revisited 📀 bonus features

The main locations for Brideshead Revisited are Oxford, Venice and Castle Howard, a stately home in Yorkshire. The miniseries used Castle Howard for Brideshead so the director Julian Jarrold hesitated about reusing it, wanting to forge his own path. But he decided to go for it in the end as it fits the descriptions in the book and the baroque architecture “instinctively evokes Catholicism”.

It is a stunning place and one understands why Charles Ryder fell under its spell.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Castle_Howard

📷 My edit from Brideshead Revisited 📀 bonus features

The original score for Brideshead Revisited was written by Adrian Johnston and is one of my many favourite things about the film. It is beautiful and mirrors wonderfully all the emotions of hope, loss, heartbreak and nostalgia from the story.

Here are a few samples:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yjq62bxvWE8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Chp7LszUYp8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U2YXscQND64

#matthew goode#brideshead revisited#charles ryder#hayley atwell#emma thompson#michael gambon#evelyn waugh#jeremy irons#anthony andrews#julian jarrold#castle howard#jess hall#adrian johnston#ben whishaw

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝕲𝖚𝖎𝖉𝖊 𝖋𝖔𝖗 𝕯𝖆𝖗𝖐 𝕬𝖈𝖆𝖉𝖊𝖒𝖎𝖆 - 𝖒𝖔𝖛𝖎𝖊𝖘+ 𝖒𝖞 𝖗𝖆𝖙𝖎𝖓𝖌

Movies with a Dark Academia aesthetic are often set in prestigious universities and they could involve a murder or simply one’s pursuit of self.

I will also write my opinions on those movies with a star rating:

✩ - Failure / Offensive / Toxic

★ - Enraging / Wholly Deficient / Shameful

★★ - Disappointing / Mediocre and Uninteresting / Soulless

★★★ - Good / Interesting Concept or Execution / Eye-Opening

★★★★ - Great / Exciting, Affecting, Memorable Achievement / Enlightening

★★★★★ - Favorite / Masterpiece / Divine Encounter

Now let’s get into it!

1. Dead Poets Society - by dir. Peter Weir (1989) ★★★★★

2. Kill Your Darlings - by dir. John Krokidas (2013) ★★★★

3. Maurice - by dir. James Ivory (1987)

4. Mary Shelley - by dir. Haifaa al-Mansour (2017)

5. Tolkien - by dir. Dome Karukoski (2019)

6. Sherlock Holmes - by dir. Guy Ritchie (2009)

7. The Imitation Game - by dir. Morten Tyldum (2014)

8. The Riot Club - by dir. Lone Scherfig (2014)

9. The Dreamers - by dir. Bernardo Bertolucci (2003)

10. Dorian Grey - by dir. Oliver Parker (2009)

11. Rope - by dir. Fred Hitchcock (1948)

12. A Separate Peace - by dir. Larry Peerce (1972)

13. Picnic at a Hanging Rock - by dir. Peter Weir (1975)

14. Suspiria - by dir. Dario Argento (1977)

15. School Ties - by dir. Robert Mandel (1992)

16. A Little Princess - by dir. Alfonso Cuaron (1995)

17. Lost and Delirious - by dir. Lea Pool (2001)

18. Mona Lisa Smile - by dir. Mike Newell (2003)

19. The History Boys - by dir. Nicholas Hytner (2006)

20. Freedom Writers - by dir. Richard Lagravenese (2007)

21. The Great Debaters - by dir. Denzel Washington (2007)

22. Black Swan - by dir. Darren Aronofsky (2010) ★★★★

23. Whiplash - by dir. Damien Chazelle (2014)

24. Raw - by dir. Julia Ducournau (2016)

25. Handsome Devil - by dir. John Butler (2016)

26. Novitiate - by dir. Margaret Bettes (2017)

27. Brideshead Revisited - by dir. Julian Jarrold (2008)

28. Northanger Abbey - by dir. Jon Jones (2007)

29. The Theory of Everything - by dir. James Marsh (2014) ★★★★★

30. Carol - by dir. Todd Haynes (2015)

31. The Goldfinch - by dir. John Crowley (2019) ★★★★

32. An Education - by dir. Lone Scherfig (2009)

33. Hugo - by dir. Martin Scorsese (2011)

34. The Jane Austen Book Club - by dir. Robin Swicord (2007)

35. The Danish Girl - by dir. Tom Hooper (2015) ★★★★★

36. Grimson Peak - by dir. Guillermo del Toro (2016)

(PICTURES ARE FROM PINTEREST. ALL CREDITS TO THEIR AUTHORS. IF YOU OWN ANY OF THESE PICTURES AND WANT THEM REMOVED JUST LET ME KNOW)

-michala <3

#darkacademia#dark academia#dark academic aesthetic#dark academic#dark academia tips#darkacademic#dark academia movies#dark academia films#filmography#the danish girl#the goldfinch#the theory of everything#black swan#the history boys#dead poets society#sherlock holmes#kill your darlings#maurice#dorian grey#the jane austen book club#mary shelley#tolkien#freedom writters#movie recommendation#classic film

933 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pride Month – Trans Literature

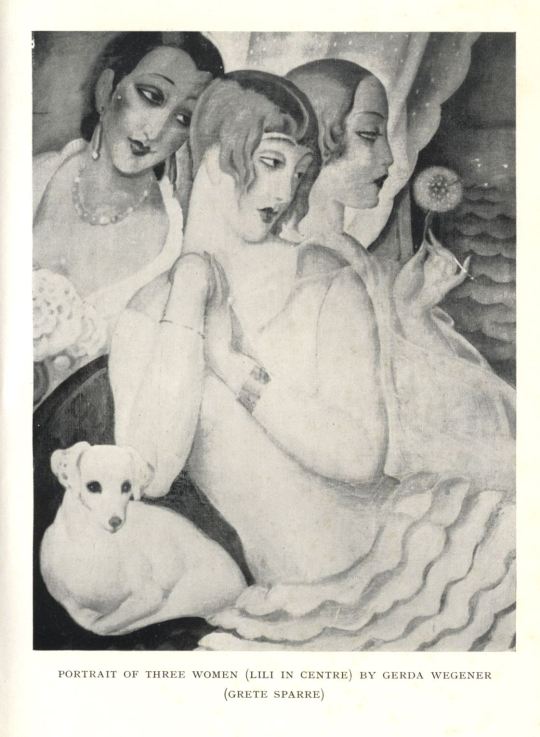

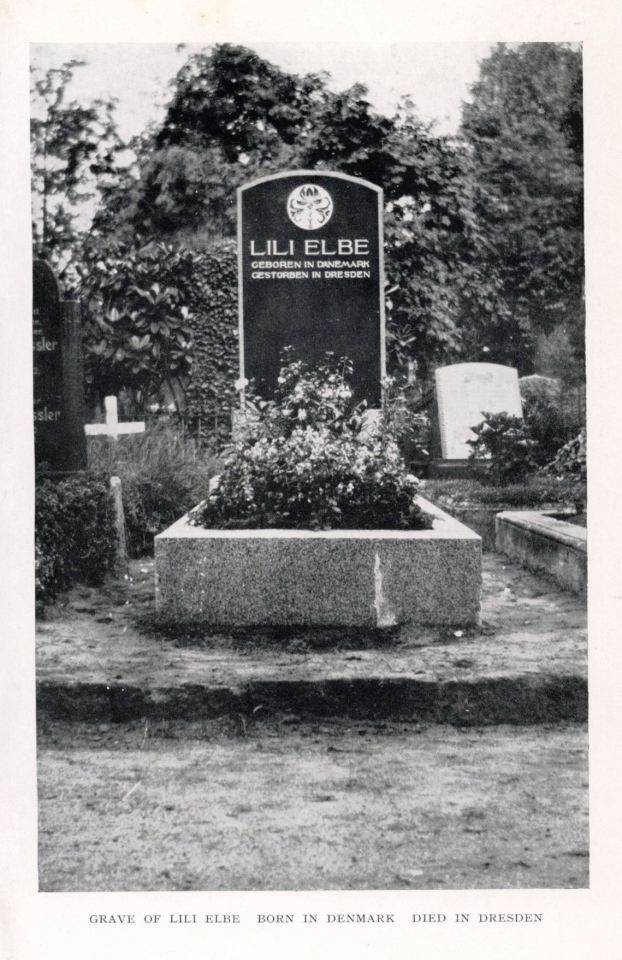

UWM Special Collections holds numerous publications in its UWM LGBT Collection documenting the history of the trans experience. Our earliest publication is this 1933 biography of Danish artist Einar Wegener/Lili Elbe, Man into Woman, An Authentic Record of a Change of Sex, compiled and edited by Niels Hoyer (pseudonym for the German writer and translator Ernst Harthern). Elbe was a transgender woman and one of the first documented individuals to receive gender reassignment surgery.

Purportedly on Elbe’s own wishes, Hoyer wrote the account “partly from his own knowledge, partly from material dictated by Lili herself, partly from Lili’s diaries, and partly from letters written by Lili and other persons concerned.” The original Danish edition was published in 1931 under the title Fra mand til kvinde, published by Hage & Clausen. A year later it was published in German by C. Reissner in Dresden under the title Ein Mensch wechselt sein Geschlecht, eine Lebensbeichte; aus hinterlassenen Papieren. Our copy is a fifth printing of the first English-language edition translated by the English socialist and translator Henry James Stenning, and published in 1933 by Jarrolds Publishing. The book includes 25 photographic illustrations and an introduction by the noted Australian/British sexologist Norman Haire.

Elbe was married to Gerda Gottlieb Wegener, a very well-noted artist in her day, and many of her paintings used Elbe as a model. The book not only includes images of Einar, Lili, Gerda, and their friends, but also images of several paintings by Gerda Wegener. Lili Elbe died in 1931 at age 48 not after a second surgery as depicted in the highly fictionalized 2015 biopic The Danish Girl, but after a fourth to implant a uterus, which was rejected by her immune system. The film by Tom Hooper is based on the 2000 novel of the same name by American writer David Ebershoff, which in turn drew much of its source information from Man into Woman.

NOTE: This post is derived directly from our earlier 2016 post highlighting the Oscar nominations for the film.

#Pride Month#LGBTQ+ Pride#LGBTQ+ history#Trans Pride#Lili Elbe#Einar Wegener#Man into Woman#Gerda Wegener#Niels Hoyer#Ernst Harthern#Henry James Stenning#Norman Haire#The Danish Girl#Tom Hooper#David Ebershoff#transgender#transsexuals#gender reassignment#UWM LGBT Collection#trans literature#lgbtq+#queer

722 notes

·

View notes

Text

Little Women (2019)

A first for the blog: a guest post! The following is a review of Greta Gerwig’s Little Women (2019) by Carly Henderson.

---

When creating a film version of a classic novel, one often wants to justify its existence by approaching the story with a new lens that appeals to its contemporary audience and differentiates it from previous film adaptations. The temptation with this approach, however, is to take a sub-theme and make it the overarching theme, or to misinterpret a theme altogether. The resulting film, then, is either off the mark or entirely antithetical to the source material. This is often what happens in modern adaptations of classic stories (Ang Lee’s Sense and Sensibility, Joe Wright’s Pride and Prejudice and Anna Karenina, Julian Jarrold’s Brideshead Revisited, and Netflix’s Anne with an E, to name a few), and is also the case for Greta Gerwig’s Little Women.

My opinion will be unpopular, as Gerwig’s adaption of Little Women has been widely received with praise for its creativity, innovation, liveliness, direction, and attention to the novel and its fresh resonance with a modern audience. And it’s true: it’s lovely to watch, overall well-acted, has an excellent score, and, I would argue, is the most bold and creative take on the classic story by Louisa May Alcott yet. Many commenters at the film’s release said that every generation deserves its own Little Women, and this version of Little Women is one that only a modern feminism could create and deserve (the film opens and closes with a salary negotiation between Jo and her publisher, the first scene ending with her acceptance of an unjust wage from her publisher, and the last ending with her fair negotiation, making her an equal player with the man). Even so, what makes it distinctive also makes it a denial of itself. Its modern lens overlooks and destroys the heart of the story, and its bold, artistic rendering ends up being a beautiful but empty shell, lovely to behold, but easily cracked and hollowed of its substance. And this is what we get with Gerwig’s Little Women: it’s a coming of age story that focuses on women’s empowerment, equal wages, opportunity, and creative genius at the expense of the growth and maturity of its characters. Alcott’s Little Women is certainly empowerment and creativity, but it is much more than this—it is at its core a story about growth, virtue, and a certain open receptivity before life that allows one to truly be creative and fruitful.

Though I may have criticism of the film overall, the acting in it is a masterclass: Saiorse Ronan is a force to be reckoned with; Florence Pugh makes the ever controversial Amy loveable (perhaps even more lovable than Jo, which is quite the feat), and Timothee Chalamet is a good Laurie, perhaps truer to the novel’s Laurie than Christian Bale’s portrayal in the 1994 adaptation (though his Laurie for me remains superior to all other Lauries). The film is not linear. It starts in “present” adult life, as Jo is in New York and Amy in France, and shifts back to childhood in flashbacks. This has a dizzying effect and can be difficult to follow, even for those familiar with the story. The advantage of this is twofold: on the one hand, the film seeks to take the adult versions of these characters seriously, where other film adaptations tend to give more time to their childhood; on the other hand, it bends the audience to favor a Laurie/Amy pairing from the beginning. This is a victory for sure, overcoming the long-held resentment about Amy, as many continue to think that Laurie should have ended up with Jo. And there is no doubt that Gerwig is technically excellent: the cinematography is beautiful, the music is beautiful, the costuming is beautiful.

But the film gets a great deal wrong about the novel, which should matter if one thinks that a film adaptation should try and capture the animating force of its original material, even if it is impossible to illustrate every aspect. I will limit myself to three points.

First, the film gets Beth all wrong. In the novel, Beth is the heart of the story. She is warm, sweet, and gentle, the one who has a special bond with Jo and the only one who can temper and correct her. Gerwig’s Beth is an odd recluse—apparently also a concert pianist—who is abnormally childlike and random, and without the warmth that is one of the defining traits of Beth’s character. She is often called “sweet one” by her sisters, but little is done in the film to communicate her sweetness. She whines and complains when no one will join her to visit the Hummels; she speaks like a 4 year old before the horses. And, above all, the warmth between her and Jo is not felt. Jo needs Beth to be herself to temper her fire and refine it to something more true, strong, and gentle. It feels as if Gerwig must reconstruct Beth because Beth’s quiet, gentle, and demure personality is not consistent with the idea of femininity as creative self-determination that Gerwig favors. Beth can’t be herself in this film because for Gerwig Jo needs no character arc: she has nothing to learn other than to be more forceful and direct. In fact, Jo seems to be the best of womanhood, forging her creative path and destiny with no need of anyone—not her father, not Prof. Bhaer, and not even Beth, which is in striking contrast to the book.

Aunt March’s character is similarly sacrificed to Gerwig’s particular ideal of femininity. Interestingly enough, Aunt March in this film becomes the aspirational model. In contrast to the book, in Gerwig’s film, Aunt March is the sister of Mr. March. This means she is not only unmarried and rich; she also has never been married, which for Gerwig means she has freedom and means. Let’s side step the question of how an unmarried sister inherits and keeps the family wealth, and note that the real problem here is that Gerwig’s Aunt March represents the only path to freedom for the March girls: money. Are we really prepared to declare that freedom simply is access to capital? That none of the girls’ artistic endeavors mean anything unless they indeed capitalize on them? Here it seems to me particularly clear that Gerwig unknowingly submits Alcott’s work to the architecture of late-stage capitalism.

Additionally, Streep’s Aunt March is a one-dimensional character, surprisingly enough for Streep. In the novel (and in the 2017 BBC adaptation by Helen Thomas), Aunt March is a tragic figure: a widow whose only child died in her youth, and one who says stupid things, but then later realizes it and has the humility to apologize. She therefore is a character of depth—that is, in the novel, she too grows and matures, whereas Streep’s Aunt March has no arc. Streep’s Aunt March is the woman to be: nothing to learn and dependent on no one.

These first two misinterpretations are ultimately the consequence of Gerwig’s misunderstanding of the novel, or perhaps better, her imposing her own (capitalist?) framework on Alcott’s work. In Gerwig’s Little Women, feminine agency is pure self-determination, self-construction, choice, and ambition (which is agency simply in a liberal, capitalist society). This is why Jo and Amy stand out in this film, and Meg and Beth only awkwardly fit in until they ultimately fade away (figuratively and literally, respectively). Indeed, the film’s overarching framework of women as creative, ambitious, self-directing and -constructing, cannot explain the beauty, dignity, meaning, and fruitfulness of both Meg and Beth’s lives apart from choice, precisely because their lives are very hidden, normal, and for all intents and purposes, without fiery ambition. Indeed, choice is the only way to understand Meg’s character in this framework (and which Emma Watson attested to in various interviews): Meg has chosen to be a wife, and this choice gives her life’s path purpose, meaning, and reconciles it with Gerwig’s feminism. Being a wife and mother in and of itself is not what gives her life dignity and purpose—rather it is her choice to do so that does. This problem also stands out in dramatic effect in Amy’s monologue (penned for this film) of marriage as an economic institution that depersonalizes women, as well as Jo’s similar understanding of marriage. Granted, marriage is an economic institution and this aspect of it was particularly felt in this time—but it is not solely an economic institution. It is a good in and of itself, formative for the person, and, above all, the form of love itself. In promoting the almighty reign of choice, the reality of love is undermined, and, ultimately, the true dynamism and variety of femininity is undermined.

But if domestic life is worthy of art and importance, as the characters reflect on at the end of the film, it isn’t because it is something merely chosen by women. We can make poor choices after all. It is rather because there is something inherently important and meaningful about domestic life itself. But if Gerwig were to admit this, it would undermine her framework of feminine agency, freedom, and choice, equality, and thereby, the whole theme of her film. We see this in the meta ending, which, despite the popular interpretation of the novel, is not ambiguous: in Gerwig’s retelling, Jo does not marry Bhaer. Why? Because she is told that she loves him; Gerwig’s Jo would never let anyone tell her how she feels and then stake her life on that (it is interesting to note that, in the book, Jo comes to realize, on her own, that she loves Bhaer, and her family gives her the space to discover this).

And while we are on the subject, I will add one final thing that the film gets wrong: Professor Bhaer. Sure, Louisa May Alcott may have written this character with tongue in cheek to stick it to her publisher for marrying Jo off at the end of the story—i.e., instead of a young, handsome man, Jo falls for an older immigrant, who is bear-like, awkward, yet sweetly endearing—but he is still a good and important character for Jo’s arc as both a woman and a writer. In casting (the strikingly beautiful, might I say) Louis Garrell as Professor Bhaer, Gerwig plays into the cliché ending that Alcott intentionally avoided. Gerwig’s point is clear, but made without the nuance and depth that Alcott gave both the character and the ending.

Whatever the case of Alcott’s original intention, the fact is, Jo becomes a true artist when she allows herself to be affected by others: i.e., when she allows Beth’s nature to temper hers, allows herself to be guided by the wisdom of her father, and allows herself to be moved by the wisdom and love of Professor Bhaer. This isn’t to say that she isn’t creative or independent; it is to say that creativity is always the fruit of relationship. Creativity does not come out of nothing; much like virtue and fruit, it is pruned out of us, sometimes painfully, by another and by life itself. This is what Gerwig’s tale misses, and this is ultimately why it is a deeply dissatisfying adaption.

#little woman 2019#little women#greta gerwig#little women movie#saorsie ronan#timothée chamalet#florence pugh#emma watson

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just Finishe Ogre Enchanted

And I have A Lot of things to say (spoilers ahead):

The introduction of lady knights thrills me to my core

There is an incredible amount of Ella Enchanted fanfic material to be found in this novel, not the least of which is an AU in which Ella is the princess and Char is the son of a knight. And that's only a slight AU!

Evie is bi, my friends, and there is nothing in the book to say otherwise. Imagine--Eleanor brings her young daughter to visit her friend in Jenn. They keep in contact, Eleanor falls in love with Evie. She manages to break Lucinda's curse and divorces Sir Peter to live happily ever after with Evie (and Wormy??)

They name their coins after their kings! I never understood that before and always assumed that KJ stood for "Kyrria something." It stands for King Jarrold and KI in this book stands for King Imbert! I'm a genius.

Sir Peter managed to be Gifted by Lucinda BOTH times he married. He got off extremely light the first time but paid for it later I'm cackling.

Evie couldn't be zEENed by the other ogres, but Ella could manage to zEEn ogres with like hardly any effort. Is Ella better at zEEning than actual ogres? I suppose she is just Fairy Tale Special because that's the Way it Works.

I am disappointed by the lack of satisfying characterization. I don't really feel like I know the main character. Which is potentially fitting for a children's book (which this is) but reads flat to me.

Much More Violence than Ella Enchanted. The main character murders one of her (temporary) own kind by skewering it through the back of the neck with a rapier. Ogres begin feasting on a hypnotized giant while she is fully conscious. She is described as missing chunks and bleeding heavily.

Wtf is with the dragon pee? I was not expecting to read about a young girl off to scoop up some pricey purple dragon piss but that's what we were given and...to be honest, okay. But did she have to say pee so much? Did there need to be so much internal monolguing about where to find dragon pee? It's fine I'm whining.

I would like to know what, exactly, Evie's 'tingles' were supposed to be. Is this girl horngy every time she sees a flesh person??? I understand she's fifteen but that's a lot of horny. I choose to believe she just wanted to eat them very badly and confused it for love lmao.

Someone hug Evie!!!!

I liked seeing a different side of Kyrria. Ella showed us what it was like to be an attractive, wealthy girl in the city. Evie taught us how many drops of piss in your tea clears up indigestion and how to be graceful even when you smell like four pigs and manure.

Now give us the sequel that's about Ella's children..............please

#oodmoodfood#gail carson levine#ogre enchanted#ella enchanted#why does this literary world mean so much to me?#blease give us ella and char's many queer children#......blease#not to say i was disappointed but i kind of expected better? maybe i should try being the intended audience next time i read a book lmao

1 note

·

View note

Text

Winifred Duke - Dirge For A Dead Witch - Jarrolds - 1949

#witches#dirges#occult#vintage#dirge for a dead witch#jarrolds#jarrolds books#winifred duke#anne chalmers#dead witch#1949#novel

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Image taken from page 29 of 'Leaves from the Log of a Gentleman Gipsy in wayside camp and caravan, etc'

Image taken from: Title: "Leaves from the Log of a Gentleman Gipsy in wayside camp and caravan, etc" Author: Stables, Gordon Shelfmark: "British Library HMNTS 10350.ee.31." Page: 29 Place of Publishing: London Date of Publishing: 1891 Publisher: Jarrold & Sons Issuance: monographic Identifier: 003471551 Explore: Find this item in the British Library catalogue, 'Explore'. Open the page in the British Library's itemViewer (page image 29) Download the PDF for this book Image found on book scan 29 (NB not a pagenumber)Download the OCR-derived text for this volume: (plain text) or (json) Click here to see all the illustrations in this book and click here to browse other illustrations published in books in the same year. Order a higher quality version from here. from BLPromptBot https://ift.tt/2DaVjjZ

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Anne Hathaway dans "Jane (Becoming Jane)" biopic de Julian Jarrold sur la vie de la romancière Jane Austen (1775-1817), décembre 2022.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

FOR SALE at PHOOKA BOOKS

Scottish Ghost Stories | Elliott O'Donnell | 1975 | PB

An excellent selection of Scottish ghost stories are found in this gorgeous vintage edition from Jarrold Colour Editions. Illustrated by Tim Hunt throughout, eighteen chilling tales are brought vividly to life.

Perfect for fans of folklore, horror and the supernatural!

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louisa sighed but giggled at the sight of his face. “Oh, David, you never attend to me! Sometimes I do not know why you bothered to come and see me, if you have no wish to listen!”

Because, David had wished to say, you are beautiful. You are clever. You make my heart do a horrible pitter patter that makes it hard to swallow and though I hate the sensation, Louisa, I wish to feel it every day.

Every day for the rest of my life.

- Advent with an Archduke by Emily EK Murdoch

#romance wednesday#book quote#advent with an archduke#emily ek murdoch#louisa jarrold#david nelson#historical romance#regency romance#quote#quotes#booklr#bookblr#merry christmas belles and rakehells

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ramsey Campbell's Far Away and Never to be reprinted by DMR Books (book news).

Ramsey Campbell’s Far Away and Never to be reprinted by DMR Books (book news).

Dave Ritzlin of DMR Books has acquired non-exclusive reprint rights to the dark swords and sorcery collection FAR AWAY AND NEVER by Ramsey Campbell. The agent was John Jarrold. This edition will also include and extra story – A Madness From the Vaults. The book is due for publication in the autumn of 2021. Ramsey Campbell is the doyen of horror novelists. He is the only living horror writer to…

View On WordPress

0 notes